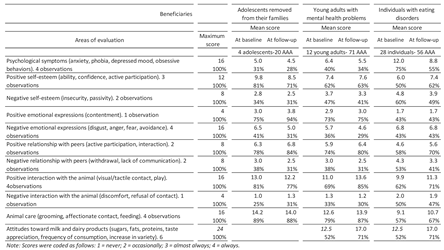

4.1. Beneficiaries’ Reactions and Human–Animal Dynamics

Although cattle are considered “domestic animals,” having been domesticated for over 10,000 years [

15,

16], many participants reported never having approached or touched a cow. Even the project coordinator noted that she herself had never regarded cattle as “domestic” in the everyday sense of the term. Beneficiaries within each group showed diverse attitudes and responses toward the cows.

Some participants expressed fear or discomfort. For example, one adolescent and one adult woman appeared visibly tense in the presence of the animal. Other participants responded with immediate curiosity and engagement. Several took numerous photographs of the cows, often posing with them, suggesting enthusiasm and a positive attitude toward interaction.

Ambivalent reactions were also observed, particularly among participants with family backgrounds in livestock farming or butchery. For these individuals, cattle appeared to carry complex and emotionally charged associations, resulting in mixed feelings.

Participants’ emotional states directly influenced the animal’s behavior. In one case, a visibly frightened participant entered the stall for a grooming activity. Their tension was evident, with abrupt reactions to minor animal movements, and the cow correspondingly displayed alert and restrained behavior. Immediately afterwards, another participant entered with a calm and confident approach. During grooming, the cow showed clear signs of relaxation—lowering its head, half-closing its eyes, and loosening its muscles.

This contrast highlighted the significant role of nonverbal communication and emotional state in shaping animal behavior during human-animal interactions.

Our results indicate that participants’ emotional states directly influenced the cattle’s behavior, confirming that animals are able to perceive and respond to human emotions [

32]. This finding aligns with previous studies highlighting the central role of the human–animal bond in AAIs [

33] and the importance of the relational and welfare context for effective interventions [

34]. Such reciprocal effects may also be explained by neurophysiological mechanisms, such as oxytocin release, which fosters calmness, trust, and social bonding during human–animal interactions [

35].

Approaching, touching, and even leading a cow—with its imposing size and strength—is far from self-evident, particularly for individuals experiencing significant levels of insecurity or fear. Yet, over the course of the intervention, surprising transformations were observed. One particularly significant case involved a boy who, at the beginning of the project, openly declared his fear of dogs and animals in general. Despite this, he consistently engaged in all proposed activities and ultimately completed the program by confidently leading the cow with a rope, without hesitation. Similarly, a girl who was initially reluctant to make physical contact with the cows gradually found her own respectful way of interacting and eventually was also able to guide the cow calmly.

The scientific literature supports the idea that working with large animals can positively affect self-esteem [

24,

36]. Taking a small dog by the leash is one thing, but leading a cow, with its weight and presence, is an entirely different experience—more demanding, yet profoundly rewarding.

Overall, the data suggest a positive evolution in the emotional and relational dimensions of the adolescents, with a general reduction in problematic aspects. Interaction with the cow emerged as a central catalyst of the observed changes, consistent with evidence in the literature on the beneficial effects of AAIs in educational and rehabilitative contexts.

The project appears effective in promoting emotional well-being, strengthening self-esteem, and fostering social and affective interaction for adults with mental health issues. The cow once again emerges as a central catalyst of positive change and inclusion. The longer duration of the intervention for the family-home group may have contributed positively to some outcomes, suggesting a potential relationship between session intensity and effectiveness.

Moreover, the data confirm the effectiveness of the cow-assisted therapy program in the field of eating disorders, not only in emotional and relational dimensions, but also in relation to specific nutritional and behavioral objectives. The synergy between animal-assisted activity and clinical observation appears particularly promising in this context.

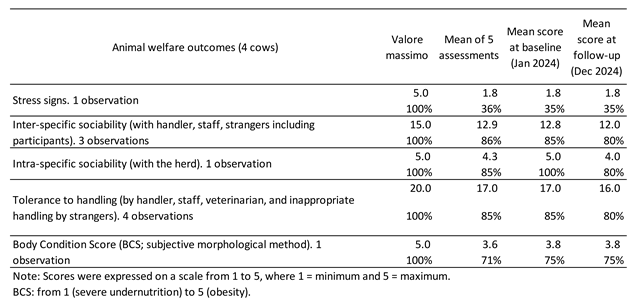

Overall, the findings confirm that animal welfare was safeguarded and continuously monitored, with generally high values and no evidence of deterioration.

The integration of a systematic assessment of animal welfare within an AAI project represents a fundamental quality element, both ethically and operationally, and strengthens the sustainability of the intervention. In particular, attention to interspecific relationships and tolerance to handling provides a guarantee of safety for both operators and beneficiaries, as well as serving as a key indicator of the quality of the human–animal relationship established.

Our findings are consistent with previous evidence on the beneficial effects of AAIs in educational and rehabilitative contexts. Improvements observed in adolescents in terms of emotional and relational dimensions, along with a reduction in problematic aspects, mirror results from meta-analyses and experimental studies demonstrating that AAIs foster self-esteem, social skills, and emotional well-being in young people [

37,

38]. Similarly, the positive changes and enhanced inclusion observed among young adults with mental health problems align with systematic reviews highlighting the potential of AAIs to promote psychosocial functioning in clinical populations [

39]. The effectiveness of the cow-assisted program for individuals with eating disorders is also consistent with prior work suggesting that AAIs can support motivational, relational, and even nutritional goals in psychiatric contexts [

40]. Importantly, our data also confirmed that animal welfare was safeguarded throughout the intervention, reinforcing literature that identifies continuous monitoring of therapy animals’ well-being as an ethical and operational cornerstone of sustainable AAI practice [

34,

41].

Our findings highlight that the safety and effectiveness of cow-assisted activities largely depended on the quality of the relationship between the cows and their handlers. The animals consistently turned to the handler for reassurance in situations of uncertainty, underscoring the central role of trust in the human–animal dyad. Similar observations have been reported in other AAIs, where the handler is recognized as a key mediator of safety and animal welfare. In particular, studies on dog- and horse-assisted interventions emphasize that the handler not only prevents accidents but also provides emotional stability to both the animal and the participants [

34,

41,

42,

43]. These parallels suggest that, regardless of species, the handler’s expertise and bond with the animal represent a critical factor for minimizing risks and ensuring a positive therapeutic environment.

4.2. Economic Sustainability of AAIs Conducted with Cows

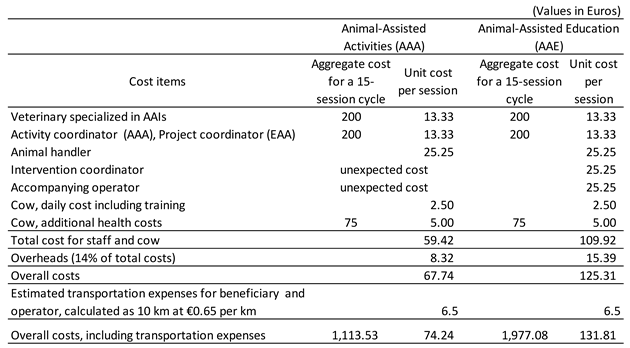

The cost analysis highlights that the largest share of costs does not derive from animal care (approximately €7.50/session, including feeding, training, and healthcare), but rather from professional and human resources (veterinary expert, coordinator, handler, and staff). At the same time, the relatively low direct costs for the animal confirm the centrality of human-animal interaction as a professionalized and structured activity, rather than a simple extension of animal husbandry.

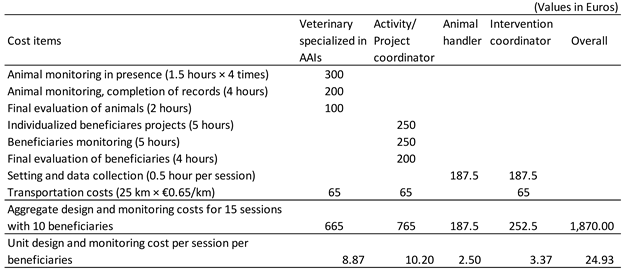

A cross-model comparison of the three animal-assisted intervention formats—AAA, AAE, and AAT—highlights substantial differences in cost structures, largely reflecting the varying degrees of professional involvement, personalization, and therapeutic intensity.

The comparative analysis demonstrates that while AAA can be implemented at relatively lower cost (this reflects the lighter structure of AAA, which emphasizes recreational and relational benefits rather than formal therapeutic goals), AAE represents a more resource-intensive model. This is justified by its stronger educational focus, the need for structured pedagogical planning, and the involvement of a larger multidisciplinary team.

Monitoring and evaluation represent a substantial share of the total costs of AAT, mainly due to the involvement of highly specialized professionals. This highlights the importance of professional expertise in ensuring the quality and safety of the interventions, but also raises the issue of economic sustainability if the service is to be replicated or scaled up. Overall, the analysis confirms that the financial sustainability of AAT is strongly dependent on qualified professional involvement, while direct animal-related expenses remain modest. The structure demonstrates how AAT programs prioritize safety, personalization, and ethical standards, justifying the relatively higher costs compared to other forms of animal-assisted interventions. The therapeutic model represents the most resource-intensive approach. The higher costs are driven by individualized project planning, continuous user monitoring, and systematic animal welfare assessments. Professional expertise accounts for the majority of expenditures, particularly the project manager and veterinary expert, reflecting the clinical rigor and ethical standards required for TAA. Animal-related expenses remain secondary but are nonetheless explicitly integrated, underscoring the dual attention to user outcomes and animal well-being.

While AAA is the most cost-efficient due to its lighter structure, AAE introduces educational complexity and logistical costs, and AAT is the most professionally demanding, requiring intensive monitoring and individualized care. The comparative analysis demonstrates a clear trade-off: as the intervention shifts from recreational (AAA) to educational (AAE) and finally to therapeutic (AAT), the financial investment increases in parallel with the level of professionalization, personalization, and expected clinical outcomes.

In all three models, animal-related costs remained modest, confirming that the financial sustainability of cow-assisted interventions is primarily determined by human resources and professional expertise rather than direct animal upkeep.

Once the costs of the individual AAI activities were identified, the economic sustainability for the cooperative was defined by the willingness to pay, either by private individuals or by public health services, a price covering the costs of the activity plus a 10% margin to account for business risk. This would imply that a user should be willing to pay €74.51 for one hour of AAA, €144.99 for one hour of AAE, and €172.41 for one hour of AAT. These prices refer to activities conducted with a single user, although such interventions are often carried out with groups.

Based on its resources and acquired expertise, the cooperative is capable of offering cow-assisted activities across all three types of AAIs. Assuming the availability of four cattle providing one session per day for 150 days per year, the annual supply amounts to 600 hours. If these hours are evenly distributed across the three types of activities, total revenues would reach €78,384 against costs of €71,258. These flows would generate an operating profit of around €7,000, in addition to the profit from the cooperative’s other activities.

When assessing the sustainability of the €150,000 investment made under project 16.9 solely in terms of the economic flows achievable by the cooperative over the next five years, the results indicate unsustainability. Indeed, the estimated Net Present Value (NPV), calculated over a 7-year horizon (with the first two years devoted to the investment) and assuming a 2% cost of capital, yields a negative result of approximately –€115,000. The investment would have been sustainable for the cooperative only with a contribution of €26,000, equal to 18% of the total investment.

It is therefore relevant to assess the sustainability of the investment from the perspective of the Umbria Region, which funded the project. Assuming that the experimentation and results attract the attention of national authorities in charge of drafting and revising AAI guidelines, the investment becomes fully sustainable if, in addition to the cooperative, at least four other farms could adopt the results and implement the activities in the same way. Under this scenario, the NPV would reach about €16,000, and the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) would be 11%. Hence, the results of the project—and in particular the cow-assisted intervention model developed—if made replicable through regulation, would allow the public expenditure on this project to be considered both effective and efficient.

Our findings indicate that the largest share of costs in cow-assisted interventions is linked to professional and human resources rather than to the direct expenses of animal care. This pattern is consistent with the wider literature on AAIs, which repeatedly highlights that the financial sustainability of such programs is primarily determined by the level of professional involvement, clinical supervision, and systematic monitoring, while direct animal-related costs remain modest [

44,

45]. A cross-model comparison also supports previous evidence: AAA is generally more cost-efficient due to its lighter structure and recreational focus, whereas AAE requires greater pedagogical planning and resources, and AAT represents the most resource-intensive model, demanding continuous monitoring, individualized planning, and specialized staff [

39,

46]. These differences in cost structure mirror the increasing degree of professionalization, personalization, and therapeutic rigor, which justify the higher costs of AAT compared to AAA and AAE [

47]. Overall, the results of our cost analysis align with the literature in showing that while animal welfare and direct animal management are important and integrated into all activities, it is the human component—expertise, supervision, and professional care—that drives both quality and economic sustainability in AAIs.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that highlight the benefits of animal-assisted interventions in promoting emotional well-being, self-esteem, and social functioning [

39,

44,

45,

46,

47]. However, the present study represents an innovative contribution by focusing on cow-assisted interventions, a scarcely explored field within the AAI literature, and by systematically integrating both human and animal welfare assessments as key indicators of intervention quality and sustainability. Furthermore, this is the first time that the economic sustainability of cow-assisted AAIs has been addressed.