Introduction

Neurodegenerative disease has been, arguably, the field of greatest biomedical therapeutic failure. From Alzheimer’s disease to diffuse Lewy body disease to frontotemporal dementia to ALS, as well as numerous others, neurodegenerative diseases have been terminal illnesses without any treatment that leads to sustained improvement, let alone a cure. Although there may be many different reasons that such therapy has yet to be developed, one likely contributor is the lack of a unifying theory, one that elucidates the pathophysiology, accurately predicts an effective treatment approach, and clarifies the various apparent paradoxes and otherwise unexplained research and clinical results. Therefore, the rationale for proposing a unifying theory of neurodegenerative disease is in the hope of fostering improved outcomes through guidelines that have already led to initial success in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

A unifying theory should offer insight into the fundamental nature of neurodegenerative diseases, and identify the most appropriate frame of reference from which to assess them. It should also reconcile the many different theories that have been proposed in the past, such as the amyloid cascade hypothesis [

1], the misfolded or aggregated protein hypothesis [

2], the tau hypothesis [

3], the prion hypothesis [

4], the reactive oxygen/nitrogen species hypothesis [

5], the infectious disease hypothesis [

6], the type III diabetes hypothesis [

7], and others. In the absence of an accurate theory, hundreds of clinical trials have been conducted blindly, i.e., without knowledge of the most critical therapeutic targets for each patient, and have seen virtually uniform failure [

8].

1) The remarkable diversity of risk factors for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, including the strong age association.

2) The mechanism(s) by which the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (ApoE4) increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease, diffuse Lewy body disease, Parkinson’s-associated dementia, and limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) [

9]; and the mechanism by which the R251G mutation mitigates this risk [

10].

3) The physiological and pathophysiological roles of amyloid-β peptides, phosphorylated tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, and other molecular species associated with the neurodegenerative process, as well as why these species function as prions.

4) The association of poorly soluble protein aggregates with neurodegenerative diseases.

5) Why some people collect relatively large amounts of amyloid-β peptides in their brains without displaying symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease [

11].

6) The increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease in women and the African-American population.

7) The lack of successful therapeutic development for neurodegenerative diseases to date.

8) The distribution of neurodegeneration in each neurodegenerative disease, and in particular, the association of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease with regions of neuroplasticity, in Parkinson’s disease with regions of motor modulation, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with regions of power amplification, and in age-related macular degeneration with regions of visual detail and color discrimination.

A great deal of the research and attempted therapeutic development has focused on the pathology associated with neurodegenerative diseases. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, this includes amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, chronic inflammation with microglial, astrocytic, and mast cell [

12] activation, and loss of synapses and neurons. While numerous attempts have been made to remove these pathological hallmarks (in particular, the amyloid-β peptides), such attempts have not led to cognitive improvement or even stabilization, although in some cases a modest deceleration in the rate of cognitive decline has been achieved [

13].

However, the demonstrations that the amyloid-β peptides associated with the plaques [

14], and the phospho-tau associated with the neurofibrillary tangles [

15], both display antimicrobial properties, argues for a shift of focus from pathology to physiology. What is the nature of the organismal response that includes the Alzheimer/Fischer pathology, and what microorganisms or other insults initiate this response? Is the inciting agent or agents similar for each person affected, or do they vary widely? Can the process be predicted, prevented, and successfully treated?

Here we propose a new theory of Alzheimer’s disease that is readily extrapolated to other neurodegenerative diseases, and which evinces a clear-cut path to effective treatment and prevention, one that has already shown success in proof-of-concept trials [

16,

17] as well as numerous anecdotal reports [

18,

19,

20]. In summary, this theory includes the following conceptual features:

1) An origin in antagonistic pleiotropy, which creates Achilles heels for the major neural subnetworks due to repeated evolutionary selection for performance over durability.

2) Neurodegenerative diseases represent network insufficiencies, in which the network supply is exceeded chronically or recurrently by the demand. The mediators of these network insufficiencies are prionic insult responses (PIRs), which may be triggered by chronic mild (i.e., low multiplicity of infection (MOI)) infections, toxicants, toxins, other causes of innate immune system activation, or of energetic support reduction, such as occurs with sleep apnea, insulin resistance, or vascular compromise.

3) Of the numerous parameters affecting supply and demand for these neural networks, the major groups of supplies are three: energetics, trophic support, and neurotransmitters; and the major groups of demands are three: inflammation (predominantly chronic innate system immune stimulation (ISIS) due to chronic infectious agents or dysbiosis), toxicity, and stress. Thus there are many potential contributors to such network insufficiencies, such as sleep apnea, air pollution, insulin resistance, and biotoxin exposure, among many others; and each individual may have a different set of contributors, which are in most cases multiple.

4) The age dependence of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases is caused by the dichotomy between the pathophysiological process—which, in Alzheimer’s, is predominantly a mild chronic innate encephalitis—and the cause of the symptoms—which, for all neurodegenerative diseases, is reduction of a neural subnetwork (via loss of function, and ultimately structure) below the functional complexity required for normal tasks. Thus it is the time-dependent sum of the effects of the pathophysiology (reduction in network synaptic function), rather than the ongoing pathophysiology itself, that is directly associated with symptoms.

5) Just as there is a state switch from sleep to wakefulness, with coordinated manifestations throughout the body (affecting neurotransmission, hormone levels, voluntary muscles, heart rate, detoxification, and many other parameters), so there is a systemic switch from a state of connection to one of protection, and this coordinates many different signaling pathways and physiological parameters, from amyloid precursor protein cleavage and signaling to amyloid-β oligomerization to tau phosphorylation to microglial activation to thrombotic propensity to innate immune system activation to blood-brain-barrier permeability to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition to tryptophan metabolism to reelin levels to apolipoprotein E signaling to hippo signaling to synaptoblastic:synaptoclastic ratio, as well as other signaling pathways relevant to synaptic connectivity vs. immune-based protection.

6) The central role of prions in neurodegenerative diseases is as mediators of a protective response to many different insults such as chronic low-level infections or toxin/toxicant exposure (

Table 1), and reflects the fact that they are not only proteinaceous infectious agents [

4], as demonstrated by Prusiner and his colleagues, but also proteinaceous anti-infectious agents (a “praion” effect of prions;

Table 1) [

14] and metal-binding agents [

21] (the combination of which makes them candidate anti-biofilm agents), as well as physiological response amplifiers of signals (a “prason” effect; i.e., switches) and mediators of the proteinaceous inheritance of traits (a “printon” effect). Here it is proposed that prions also play a crucial physiological role as pre-inflammatory immune mediators (a “priion” effect of prions), such that, at low pathogen burdens, prions allow for sequestration and destruction of pathogens with minimal inflammatory impact on neural function [

22]. This mechanism of prions creates what is essentially an internal barrier function, analogous to the barrier function of structures such as epidermis and cerumen, which provide an anti-microbial effect that in many cases avoids the engagement of the innate immune system with its attendant inflammation and functional compromise. Thus prions such as amyloid-β and α-synuclein may populate and protect the nervous system for years with minimal impact on neural network function, which represents a clear advantage for the organism; however, with continued pathogen exposure or increased burden, inflammatory pathways become activated, leading to or enhancing neurodegeneration and dysfunction. Furthermore, this pre-inflammatory set point—i.e., the point at which the non-inflammatory effect is superseded by a pro-inflammatory effect, advancing pathophysiology and ultimately leading to symptoms—is balanced: for amyloid-β there is an anti-inflammatory effect of sAPPα (and a pro-inflammatory effect of ApoE4), and for PrP

Sc there is an anti-inflammatory effect of PrP

C, as examples.

Because of the central role of prions and their multiple physiological effects in the response to the numerous insults that initiate and contribute to neurodegenerative diseases, this new theory has been dubbed the prion-priion (“pree’-on-pree-eye’-on”) theory (Pr2 theory).

The Physiological Roles of Prions

Prions are the black holes of the neurodegeneration field—lethal, ubiquitous, and paradigm-challenging. Although these were originally described as disease-causing agents, Jarosz and colleagues have described multiple salutary effects such as response to stress and non-Mendelian inheritance of protective traits [

24], while discovering dozens of new prions in yeast. These protective traits could be passed from generation to generation via protein in a non-Mendelian fashion, and thus prions are also mediators of protein-inherited traits.

While some of these newly discovered prions form amyloid (as do amyloid-β, p-tau, and α-synuclein), others are DNA-interacting proteins (as is TDP-43). These proteins have the ability to spread protective properties from cell to cell and organism to organism. Just as bacteria may spread adaptive traits genetically via plasmids, prions may represent a mechanism for both horizontal and vertical, non-genetic transfer of adaptive traits. It is of more than passing interest that both neuroplasticity and prions are drivers of organismal evolution and adaptation, since it has been demonstrated that prions play a role in learning and memory, specifically in persistence of memory [

25].

These findings expand the repertoire of prions far beyond causing disease, and in keeping with the Pr2 theory, shift focus from pathology to physiology. The prions associated with neurodegeneration function as anti-infectious agents, and the distribution of microbes against which each prion exhibits efficacy should help to reveal the upstream contributors to neurodegeneration for each individual. For example, as Soscia et al. reported, amyloid-β peptides exert antimicrobial effects against

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Listeria monocytogenes, and the virus

Herpes simplex, among others [

14]. Therefore, in those with evidence of amyloid-β deposition, these organisms should be sought and, if revealed, treated. Furthermore, these prions also possess metal-binding properties, and the combination of metal binding and antimicrobial effects make prions strong candidates to function as anti-biofilm agents.

Beyond their antimicrobial effects, prions serve as physiological response amplifiers of signals: classic homeostatic signaling occurs when single-target outcomes are the goal, such as a serum pH of 7.4, and amplification is not required; in contrast, prionic loop signaling occurs when switching is required in a bistable system such as blood clotting or neurite extension/retraction. APP signaling represents an example, in which two different outcomes—the α and β pathways—are mutually inhibitory [

23].

Here it is proposed that prions also play a crucial role in brain protection by functioning as pre-inflammatory immune mediators (“priion” effect of prions), internal barriers analogous to the antimicrobial barrier substance cerumen, and that this function explains the decades-long presymptomatic stage that may occur in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Thus many cognitively normal adults are amyloid positive by PET or CSF [

26], and while many of these avoid symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease throughout their lifetimes, there is nonetheless an increase in risk for cognitive decline in those who are amyloid positive [

27]. These findings are compatible with the Pr2 theory, in which prions may isolate and destroy pathogens without creating a pro-inflammatory, cognition-compromising state until such time as an inflammatory, degenerative state supervenes.

The conversion of the pre-inflammatory protective state afforded by prions to a pro-inflammatory neurodegenerative, symptomatic state depends on factors that include pro-inflammatory gene products such as ApoE4, continued exposure to inflammagens, a failure to contain pathogens with the prions, the concentration of anti-inflammatory balancers such as sAPPα and PrPC, microglial activation, mast cell activation, astrocytic activation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling, among others.

An Origin in Antagonistic Pleiotropy

Antagonistic pleiotropy, a concept first developed in 1957 by Williams [

28] following earlier suggestions by Medawar, argues that genes related to early-life fitness are selected at the cost of later-life decline. This concept is now the most well-accepted theory of the evolution of aging, and it dictates that performance be selected over durability. Major evolutionary needs include defense/aggression/predation (i.e., lethal force), and learning/adaptation/plasticity (i.e., optimization of behavior for a given set of circumstances); in other words, optimal movement and adaptability for survival and procreation, with neuroplasticity playing a role as organismal evolution in real time.

This has important consequences for highly evolved human neural subnetworks, implying that, since we have evolved to outthink and outmaneuver our competition, we shall be susceptible to neurodegeneration. Indeed, the vulnerabilities of each network are revealed by the drivers of the associated neurodegenerative process. This is perhaps most obvious for Parkinson’s disease, in which mitochondrial function, and specifically complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase), is compromised by the many different agents that increase risk for Parkinson’s disease [

29,

30]. This implies that the motor modulatory neural network that is insufficiently supported in Parkinson’s disease is rate-limited by mitochondrial complex I. However, it is clear that other functional members of this network may also play a role in support and disease-associated dysfunction, such as ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, dopamine synthesis and neurotransmission, and lysosomal function, among others.

In the case of ALS, the Achilles heel of a system that provides several orders of magnitude of nearly instantaneous power amplification, from thought to maximal action, appears to be the removal of the excitotoxic neurotransmitter glutamate from the associated synaptic clefts [

31]. Compromise of this function by transporter mutations, toxins, reactive oxygen species, or by other mechanisms; or repeated excessive demand on this system, is associated with increased risk for ALS.

In the case of age-associated macular degeneration (AMD), the Achilles heel of a system that is highly demanding energetically, and allows humans to distinguish approximately one million different colors and shades, involves the energetic support of the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) and photoreceptor cells, as well as the complement that is activated when the physiological RPE phagocytosis of the photoreceptor outer segments (POS) begins to fail to keep up with demand.

In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, perhaps in keeping with its high incidence, there are multiple paths that lead to the associated neuroplasticity network insufficiency: insulin resistance, sleep apnea, chronic infections such as Herpes family viruses, and air pollution, among many others, with the list of risk factors suggesting that the Achilles heel for this neuroplasticity network involves inflammation and energetic support.

Network Insufficiencies

The model proposes that each neural subnetwork possesses its own activity-dependent demand for energetic, trophic, and transmitter support, a demand that is augmented by inflammation, some toxins and toxicants, and stress. Chronic or repeated failure to provide the supply required for each network’s demand leads to degeneration, which may be programmatic (analogous to programmed cell death) or non-programmatic. Thus, for Alzheimer’s disease, the probability of developing AD is proportional to the integration, over time, of the sum of the many factors contributing to synaptoclastic signaling (such as various chronic infections), divided by the sum of the many factors contributing to synaptoblastic signaling (such as nutrients and trophic support). This probability, in turn, may be approximated by considering the six major groups of drivers noted above:

The constants associated with each of the inflammatory mechanisms, toxins, stressors, energetics, trophic species, and neurotransmitters should be calculable from patient data and artificial intelligence (AI), enhancing both prognostics and therapeutic outcomes. However, the various constants (ki through kn) will only be applicable to a given genome; nonetheless, it may be feasible to estimate these by grouping data into four different genetic backgrounds, and calculating approximate constants within each of the four groups: (1) ApoE4-negative, FAD-mutation-negative; (2) ApoE4 heterozygotes; (3) ApoE4 homozygotes; (4) familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations (APP, PS1, or PS2 mutations associated with familial Alzheimer’s disease).

The theory proposes that each of the major neurodegenerative diseases represents a network insufficiency driven by various combinations of the six groups of contributors shown in the equation above, and which degenerative disease results is dependent on three variables: (1) insult(s) (such as insulin resistance, specific infections, etc.); (2) insult entry point(s) (olfactory system, blood-borne, epidermal, etc.); and (3) prionic response(s) (amyloid-β, p-tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, etc.). Thus an insufficiency due to metabolic syndrome, and HSV-1 entering via the trigeminal nerve, in the setting of enhanced inflammation due to ApoE4, with amyloid-β prionic response, would create Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, whereas an insufficiency due to mitochondrial complex I inhibition caused by systemic exposure to paraquat in the setting of compromised systemic detoxification due to a null mutation in glutathione-S-transferase M1, with an α-synuclein prionic response, would create Parkinson’s pathophysiology.

Energetic reduction is a very common contributor to Alzheimer’s disease, and likely to other neurodegenerative diseases as well, such as Parkinson’s (and related extrapyramidal diseases such as progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration) [

32], Lewy body disease, and age-related macular degeneration. This reduction may stem from vascular compromise, oxygen reduction (e.g., due to sleep apnea), mitochondrial damage (e.g., from accumulated mitochondrial DNA mutations, reduced mitophagy, toxin exposure, or other causes), or metabolic dysfunction with insulin resistance and reduced ability to generate ketones.

Neuroinflammation has been well documented in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, and microbiome studies of the brain have revealed oral flora as well as rhinosinal [

33], somewhat surprisingly both in brains without neurodegeneration and in those with neurodegeneration. The causes of neuroinflammation range from chronic infections such as

Herpes simplex or

Porphyromonas gingivalis to dysbiosis (e.g., alterations in the oral microbiome) to gastrointestinal hyperpermeability to metabolic syndrome to biotoxins, as well as other causes.

Toxin or toxicant exposures may be inorganics (such as air pollution [

34]), organics (such as anesthetic agents), or biotoxins (such as trichothecenes) [

35,

36].

Reduction in trophic support may involve reduced neurotrophins such as BDNF or NGF, reduced trophic hormones (or hormone ratios) such as estradiol or testosterone or thyroid [

37], or reduced nutrients such as vitamin D or vitamin B12. Work from Cattaneo and his colleagues has shown that simply reducing the NGF levels in transgenic mice by about 40%, using a germline genomic insertion encoding a fragment of anti-NGF antibody, was sufficient to create Alzheimer/Fischer type pathology [

38].

Reduced neurotransmitter support in Alzheimer’s disease involves multiple neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, glutamate, serotonin, somatostatin, norepinephrine, and GABA.

Increased stress, with increased cortisol levels, is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s [

39]. Furthermore, antagonism at the corticotropin releasing hormone receptor has been shown to reduce Alzheimer pathology and symptoms in a pre-clinical model [

40].

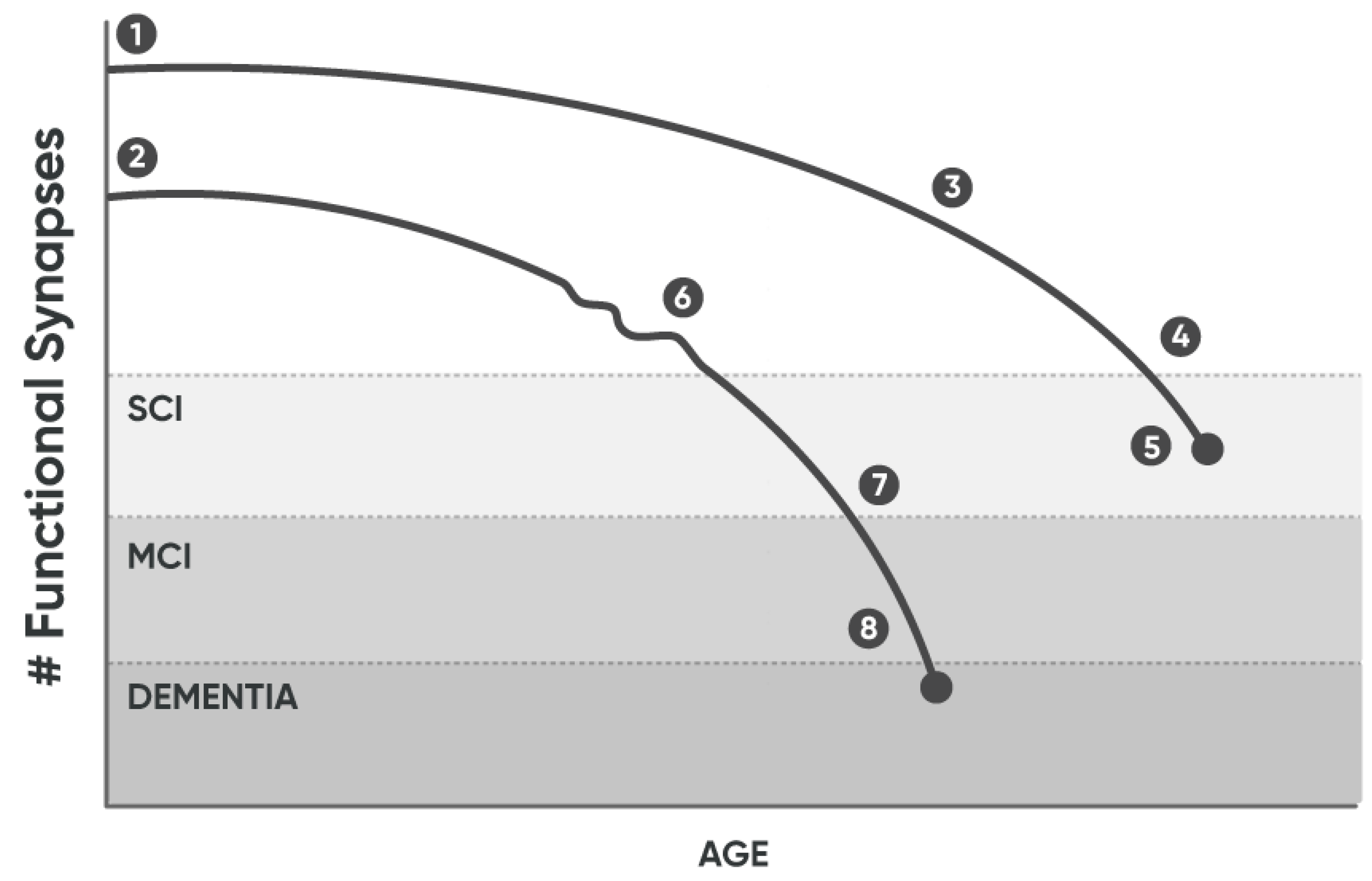

These six major determinants of the synaptoclastic:synaptoblastic ratio determine the rapidity of functional, and ultimately structural, synapse loss, and thus the time to cognitive compromise (

Figure 1).

1) As noted in the figure, the curve associated with patient 1 (1) begins with a greater number of functional synapses than for (2), in keeping with observations that those with higher educational levels are at reduced risk for Alzheimer’s [

41].

2) In contrast, the curve associated with patient 2 (2) begins with fewer functional synapses.

3) The downward slope of remaining functional synapses over time is proportional to the synaptoclastic:synaptoblastic ratio at any given time. Anatomic synapse loss and neuronal loss lag behind functional synapse loss, and thus reversal of cognitive decline is more readily accomplished earlier in the course.

4) With enough synapse loss over time, symptoms appear, and initially the patient develops subjective cognitive decline (SCI), thus remaining functional, capable of independent living, and capable of scoring in the normal range on cognitive assessments.

5) This depicts the age at death, indicating that patient 1 died without enough functional synapse loss to develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia.

6) In contrast, the timeline for patient 2 indicates that the initial number of functional synapses is fewer than for patient 1, and (6) depicts the finding that cognitive loss, as reflected by the functional synapse number, is not smooth, but rather displays increases and decreases as the variables in the equations above change, e.g., due to sleep apnea treatment or improved sleep or reduced stress or treatment of chronic infections, etc.

7) With enough functional synapse loss, the patient develops MCI. Spontaneous return to SCI (or possibly normal cognition) has been documented in some patients (5-10%). However, about 5-10% each year progress to dementia. The acceleration in the curve reflects the combination of the increasing insufficiency of support and the underlying prionic amplification (e.g., Aβ begets more Aβ by inhibiting APP cleavage by α-secretase, among other mechanisms).

8) The repeated observation that spontaneous reversals of MCI may occur [

42], but only very rarely (if at all) spontaneous reversals of dementia [

43], suggests that a prionic point of no spontaneous return occurs near the MCI-dementia transition point, i.e., that prionic amplification dominates the progression from that point forward.

9) With continued functional synapse loss, MCI progresses to dementia.

The network insufficiency that leads to synaptic loss and Alzheimer’s symptoms manifests in multiple different ways, but clinical presentations fall broadly into two groups: amnestic and non-amnestic. These distinct presentations are associated with different mechanistic drivers, neuroanatomical regions, genetic predispositions, and other parameters, summarized in

Table 2.

Connection Mode vs. Protection Mode

The physicist and Nobelist Richard Feynman said, “Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so that each piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.” This insight is applicable to the many published observations in Alzheimer’s disease (

Table 3): at the molecular level, amyloid precursor protein (APP) signaling comprises two distinct and mutually inhibitory pathways (i.e., a switch). In the presence of trophic support such as the APP ligand netrin-1 [

23,

44], APP is cleaved at a single site, the α site, yielding two synaptoblastic and anti-apoptotic peptides, sAPPα and αCTF [

45]. However, with loss of trophic support, APP is cleaved at three alternative sites, yielding four synaptoclastic and pro-apoptotic peptides, sAPPβ, Aβ, J

casp, and C

31 [

46,

47,

48]. These observations indicate that APP is a dependence receptor, i.e., a receptor capable of activating apoptosis when induced by the withdrawal of its trophic ligand [

49]. Furthermore, these two alternative APP processing pathways are mutually inhibitory: sAPPα inhibits cleavage of APP at the β-site [

50], in part by inhibiting BACE proteolytic activity [

50], whereas the Aβ peptide inhibits α-site cleavage, thus inhibiting the production of sAPPα and αCTF [

23]. These antagonistic processing pathways allow APP to function as a molecular switch, one that is potentially sensitive to many different inputs [

51], and provide a mechanism by which the Aβ peptide fulfills the criteria for a prion.

At the cellular level, switching between neurite outgrowth and dendritic spine collapse—i.e., synaptoblastic vs. synaptoclastic effects—is mediated in part by APP. At the tissue level, the protection mode is characterized by enhanced tendency to thrombosis, which is lacking in the connection mode. At the organ level, the connection mode features synaptic plasticity that results readily in learning and memory; whereas the protection mode features synaptic loss, neurite retraction, and brain atrophy that are associated with poor cognitive function.

The sum of these effects at the organismal level is to mediate a state switch from connection to protection (

Table 3): from synaptoblastic, non-inflammatory, oxidatively metabolic, low-thrombotic tendency, parasympathetic-dominant to synaptoclastic, pro-inflammatory (initially pre-inflammatory due to priions), glycolytically metabolic, pro-thrombotic, sympathetic-dominant. The common genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (ApoE4), triggers this switch more readily by altering cellular programming toward the protection mode, due at least in part to its transcriptionally repressive effects at multiple gene promoters that include anti-inflammatory genes [

52]. The systemic communication of this organismal response is presumably mediated by the nervous and immune systems, and may involve trained immunity. Over years, this state switch may lead to a reduction in functional synapses to the point of symptoms, ultimately leading to dementia.

Translational Implications of the Theory: Pathophysiology

The Pr2 theory explains the observed characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease, many of which are not explained by other theories:

•Why the origin of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions is in antagonistic pleiotropy.

•Why there are many disparate risk factors.

•Why age is the greatest risk factor.

•Why ApoE4 is such an important genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, Lewy body dementia, LATE, and Parkinson’s-associated dementia.

•Why many different infectious agents have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease, such as HSV-1, HHV-6, P. gingivalis, and Cytomegalovirus.

•How these various risk factors contribute to the neurodegenerative process.

•The physiological and pathophysiological roles of prions such as Aβ, α-synuclein, p-tau, and PrPSc.

•Why prions are key mediators, present in all of the major neurodegenerative diseases, yet in most patients with neurodegenerative diseases there is no evidence that these infectious agents were transmitted horizontally as an infection, and removing them (at least in the case of Aβ) has not led to sustained improvement in Alzheimer’s disease (and is sometimes associated with worsening of symptoms) [

55].

•Why aggregated proteins are present in all of the major neurodegenerative diseases.

•Why Aβ-containing plaques may be present for years with minimal symptomatology [

11,

56], yet over time, those with amyloid are more likely to develop cognitive decline [

27].

•Why many die with normal cognition yet display Alzheimer’s pathology [

26].

•Why Aβ exhibits multiple salutary properties—such as metal binding, effects as a sequestrant, patching of vascular damage [

57], and anti-microbial effects—in addition to its association with neurodegeneration.

•Why monotherapeutics have been so unsuccessful in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

•Why personalized, precision medicine protocols have led to the greatest improvements to date.

•Why systems biological models may be crucial for improved understanding and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

•Why previous models, such as misfolded proteins, type III diabetes, and reactive oxygen species damage, have failed to lead to successful treatments.

•Why prevention is likely to be much easier, more efficient, and more effective than reversal.

•Why some patients with Alzheimer’s have been able to achieve sustained improvement for over a decade [

58].

•Why higher education levels are associated with lower risk for cognitive decline.

•Why some vaccines lower risk (e.g., Influenza A, Herpes zoster, and BCG), whereas others like COVID may be associated with decline.

The pathological elements of Alzheimer’s disease all fit well within the schema of the Pr2 theory: upstream insults (such as insulin resistance, pathogens, or toxins) impact the equations above, switching signaling from synaptoblastic to synaptoclastic, from connection to protection mode. The response to these insults is analogous to the recognition of PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular pattens) by the innate immune system, but here represents insult-associated signaling patterns, and the response includes activation of pre-immune mediators, with production of anti-microbial peptides amyloid-β, p-tau, and α-synuclein [

59], all of which accrete in Alzheimer’s disease. These are then stored in long-lived, relatively non-toxic and non-inflammatory accumulations—much as one would keep troops in a fort after a battle—thus offering a memory-like component to the pre-inflammatory innate immune response, one rapidly available if insults are repeated. These different anti-microbial peptides are likely to display different profiles of target pathogens and cellular localizations (e.g., extracellular vs. intracellular vs. intraorganellar).

Furthermore, the protective nature of the synaptoclastic response against insults such as pathogens fits very well with the remarkably long—decades long—period of high functionality during ongoing pathophysiology. The presence of pre-inflammatory immune mediators (“priion” effect of prions) such as amyloid-β and α-synuclein allows sequestration and destruction of small numbers of pathogens without generating a function-compromising inflammatory response. The presence of anti-inflammatory balance such as sAPPα and PrPC helps to prolong the time until inflammatory pathways involving microglial activation, astrocytosis, and cytokine signaling are activated.

Another implication of the theory proposed here regards the many disparate risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, from early oophorectomy [

60] to sleep apnea to metabolic syndrome to hypertension to

Herpes simplex to ApoE4 to smoking to air pollution to age to multiple others [

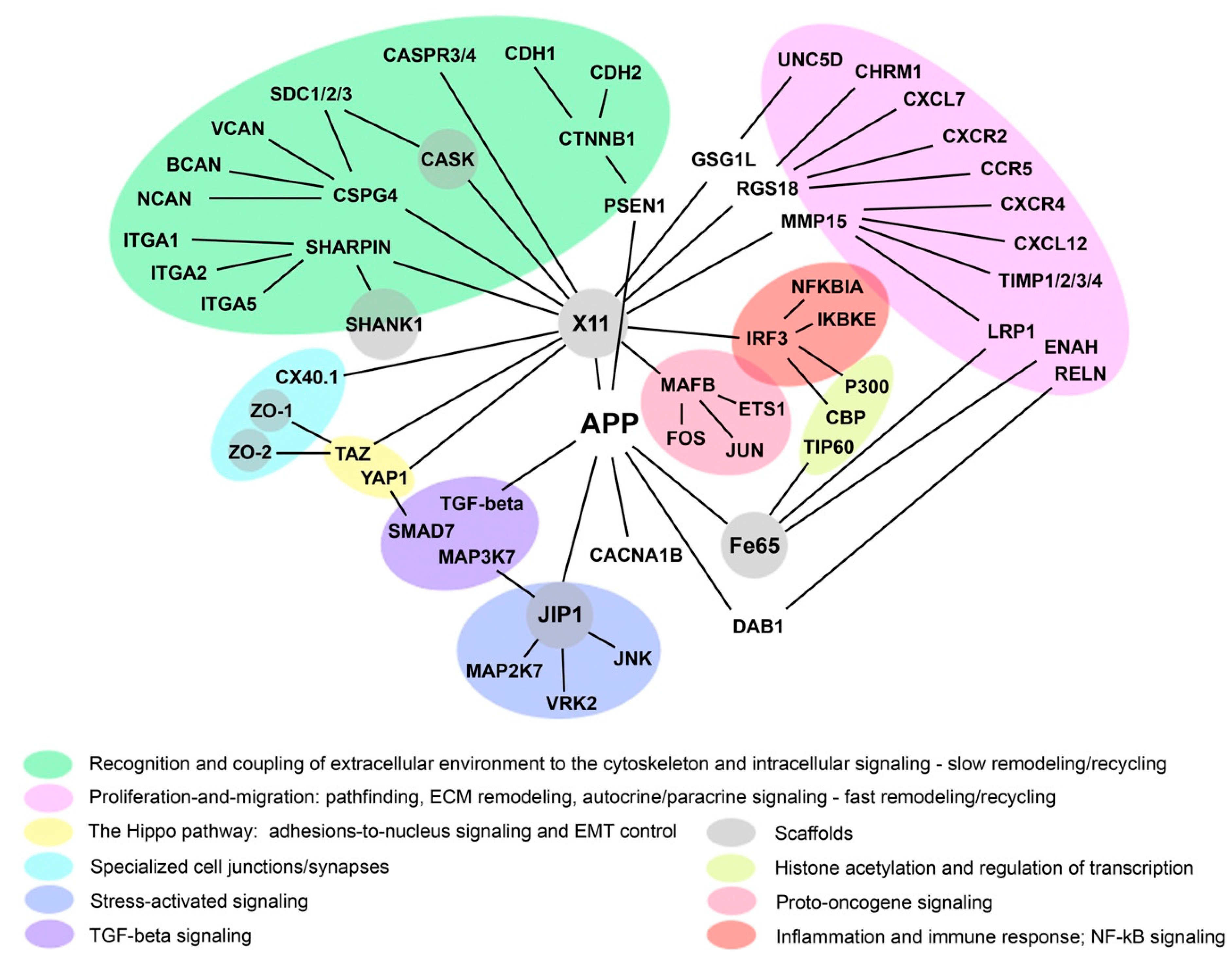

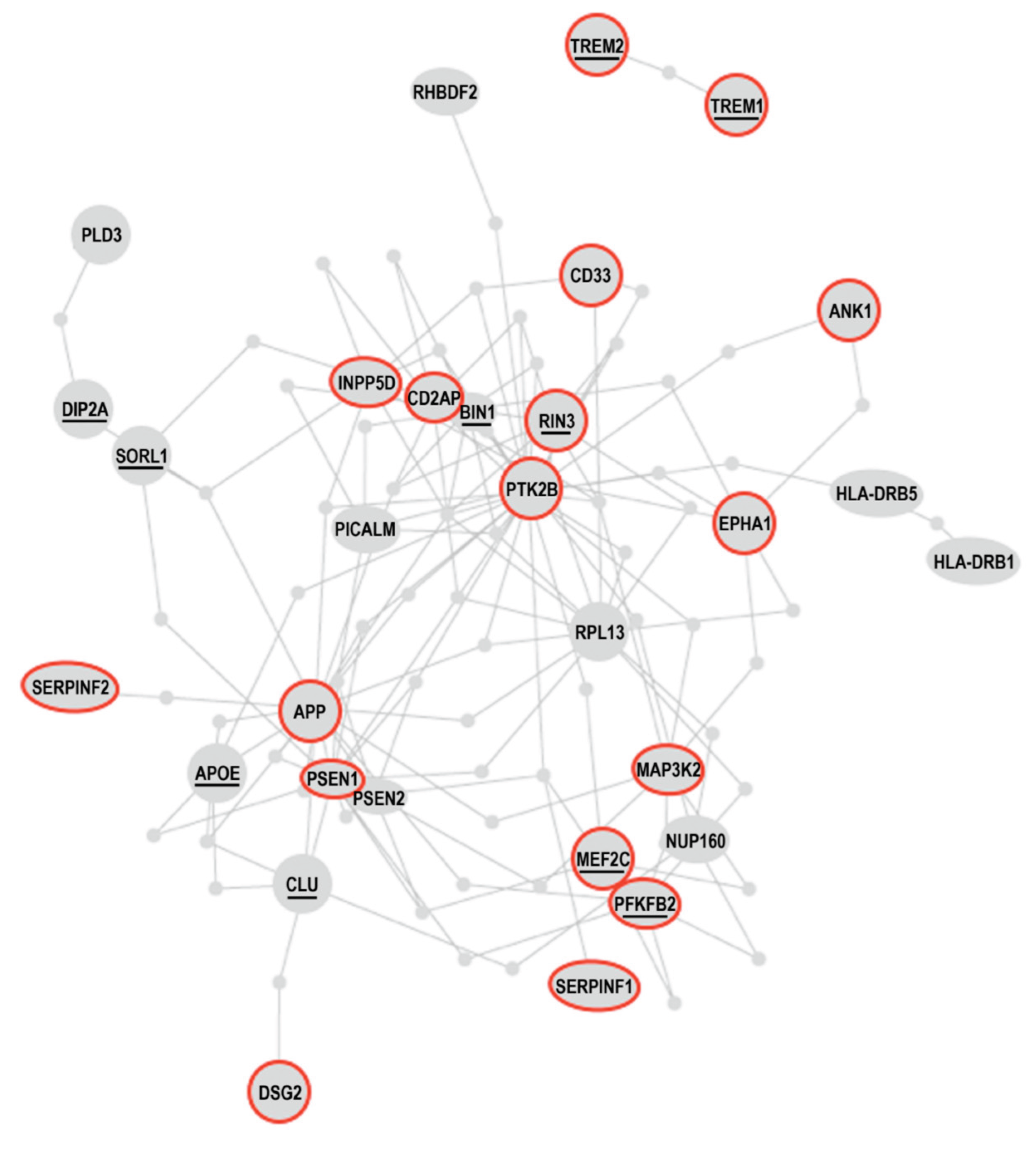

61]. Previous theories have not explained these seemingly unrelated factors, but all of these fit squarely in the equations above, and all impact the synaptoclastic:synaptoblastic ratio, either via effects on inflammation, toxic burden, energetics, stress, neurotransmitters, or trophic activity. Furthermore, genes associated with Alzheimer’s risk also impact this signaling ratio, either directly via the APP interactome or indirectly via processes such as trophic signaling or inflammatory response or neurite extension (Figures 2, 3). While the theory does not offer new insight into the gender discrimination in Alzheimer’s disease, it is compatible with the notion that women, by virtue of their more rapid decline in trophic sex steroids during menopause than men suffer during andropause, are at increased risk.

Another implication is that, as shown in the equations above, although there are many potential contributors, some patients will have dominant contributors via inflammation, and thus develop an inflammatory type of Alzheimer’s; others will have dominant contributors via toxins, and thus develop a toxic type of Alzheimer’s; still others will have a dominant contribution from a reduction in trophic support, and thus develop an atrophic type of Alzheimer’s; and others will have their dominant contribution from a reduction in energetic support, and thus develop an energetic (often vascular) type of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another implication of the theory is that the standard transgenic mouse models [

62] in use lack a critical feature, and thus it is not surprising that therapeutic success in these models has not predicted clinical success. The mice represent genetic models, and they lack the many upstream contributors (insulin resistance, chronic pathogens, toxin exposure, vascular disease, nocturnal hypoxemia, etc., as described above) that play central roles in Alzheimer’s disease in human patients. However, the theory predicts that mouse models employing the numerous features typical in sporadic AD should be more accurate in their guidance for therapeutic success.

Similarly, there is a critical distinction between the concept that an increase in amyloid-β can cause Alzheimer’s disease—which the rare APP mutations in familial Alzheimer’s disease support—and the concept of amyloid-β as the cause of Alzheimer’s in sporadic cases, as opposed to being a mediator of the pathophysiology in these much more common cases.

The immune system plays a critical role in the proposed model, just as it does for COVID-19: an optimal adaptive immune system would limit pathogen survival and avoid chronic innate system activation, thus limiting chronic inflammation. Poor adaptive system function, as well as ApoE4, increase chronic inflammation [

63]and thus move the signaling toward synaptoclastic.

The theory also explains why some vaccines lower risk—such as influenza [

64],

Herpes zoster [

65,

66], and BCG [

67]—whereas others such as COVID may be associated with increased risk for decline [

68]. Vaccines result in a lower pathogen burden over time, but also may trigger inflammation. The theory predicts that the effect on cognitive risk depends on which effect is dominant: if the dominant effect is to reduce pathogen burden (especially for pathogens that commonly trigger cognitive decline), then protection will occur, whereas if the dominant effect is to trigger inflammation associated with innate immune system activation (especially chronic inflammation), then increased risk for decline will occur. The pro-inflammatory effect of ApoE4 skews this outcome toward the latter scenario.

The theory offers a physiological explanation for the observation that prions are present in all of the major neurodegenerative diseases. Instead of horizontal transmission of prions, as has occurred, for example, in cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease due to cadaver-derived human growth hormone or depth electrodes [

69], prions such as Aβ, p-tau, and α-synuclein are host-generated and mediate at least three physiological functions: (1) they exert an antimicrobial effect (and, with their metal binding, likely an anti-biofilm effect); (2) they function as physiological response amplifiers of signals in systems in which amplification is required and multiple goals are necessary (e.g., blood clotting or neurite outgrowth vs. retraction), in which positive feedback, as opposed to homeostatic feedback, is required. In other words, in this setting, prions function as biological switches; (3) they function as pre-inflammatory immune mediators (“priion” function of prions), thus prolonging cerebral function, potentially for decades, despite the presence of minor insults such as small numbers of microbes or low levels of toxins.

Furthermore, although neurodegenerative diseases have been associated with “aggregated proteins” or “misfolded proteins,” evidence is accumulating that, rather than misfolded and aggregated proteins, these accumulations may be physiologically relevant multi-protein and RNA complexes, assembly machines [

70] that play a role in both viral capsid assembly and cellular processes such as the innate immune system response.

Another implication of the theory is the exponential increase in Alzheimer’s disease with advancing age, since aging affects multiple variables in the equation above: inflammation, toxic burden, energetics, and trophic activity, as well as the time-dependent integration of the ratio of synaptoclastic to synaptoblastic signaling based on these parameters. As p-tau studies are demonstrating, the underlying pathophysiological process is ongoing for years before enough functional synapses from the network are lost to produce symptoms [

71].

The Pr2 theory is compatible with the observation that some patients with Alzheimer’s disease may not only improve cognition, but sustain improvement for years, sometimes over a decade [

58]. Addressing the identified drivers of cognitive decline may lead to synaptoblastic signaling rather than synaptoclastic signaling, and return functional synaptic transmission, especially for those patients who begin treatment early, prior to major neuronal cell loss.

Ramifications of an optimal theory would also place the conceptual framework in its proper position with respect to other diseases, such as cancer. Unlike in cancer—in which the original insult need not continue, since its impact is usually etched into the somatic genome (or epigenome), and even amplified in a Darwinian fashion, making the removal of the original insult (such as cigarette smoke) an ineffective treatment—in Alzheimer’s disease, the insults are typically ongoing. This offers the opportunity to intervene in an insult-dependent fashion, which is an advantage over cancer treatment, but also highlights the importance of identifying and addressing ongoing insults as part of an optimal therapy for Alzheimer’s at all stages: dementia, MCI (mild cognitive impairment), SCI (subjective cognitive impairment), and presymptomatic.

The theory also suggests that progressively more predictive risk models may be derived by combining age, genome, and the variables that contribute to the ratio described above: inflammatory status, toxic burden (including effects on biochemistry, such as reduction in glutathione), energetic status (which would include several variables, such as mitochondrial function, oxygen saturation, blood flow, and ketone concentration), trophic status (which would include neurotrophic factors, hormones, and specific nutrients), stress (including HPA axis status), and neurotransmitter status (especially acetylcholine, glutamate, GABA, and dopamine). This should ultimately lead to improved actuarial tables for Alzheimer’s, thus making dementia insurance (as an active rather than passive insurance) feasible and readily affordable for most.

Translational Implications of the Theory: Therapeutics

The Pr2 theory offers clear predictions about what is required for prevention and effective treatment of each neurodegenerative disease. The rationale for Alzheimer’s disease treatment has been presented previously [

72], and the main tenets are summarized here:

1) The contributors to reduced supply and/or increased demand for the affected network should be identified. The earlier these are identified and addressed, the more rapid and complete the return of function is. Therefore, methods of early detection, such as plasma p-tau 217 in Alzheimer’s, and mass spectrometric profiling of sebum in Parkinson’s [

73]), represent key advances in the reduction of neurodegenerative disease morbidity and mortality (

Table 4).

2) The supply should be restored and demand reduced until supply once again exceeds demand, preventing further degeneration and allowing repair to occur. Only after the contributors have been identified and addressed, and the supply/demand ratio normalized, should the prions such as Aβ or α-synuclein be removed, and then only slowly, to avoid traumatic damage to vessels and other prion-associated structures.

3) The lost elements of the affected network—synapses, neurites, neurons, and other structures—should be restored, and the pathophysiological responses such as microglial and astroglial activation should be mitigated.

4) The support for the affected network should be continued and repeatedly optimized, so that sustained improvement occurs.

The Pr2 theory proposes that each of the major neurodegenerative diseases is the result of a network insufficiency, and that three different major supplies—energetics, trophic support, and neurotransmitters—are crucial to network functions, with three different major groups that augment demand—inflammation, toxicity (which commonly reduces supply, as well), and stress. However, within these groups, there are more common and less common contributors. For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, examples of the common contributors to this net insufficiency include insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, sleep apnea, air pollution exposure,

Herpes family infections, and gastrointestinal inflammation, among others. In contrast, Parkinson’s disease is often associated with organic toxicants such as trichloroethylene or paraquat, and has also been associated with a gut microbiome that includes

Desulfovibrio species [

75]. For ALS, exposures such as lead, some pesticides, solvents, and glutamatergic agents such as beta-methylamino-L-alanine are likely contributors [

76]. And for age-related macular degeneration, cigarette smoking is a common contributor, along with high-fat diets, hypertension, and high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light or blue light [

77].

Therefore, the common contributors are quite distinct for these major neurodegenerative diseases, yet all contribute, by various mechanisms, to net insufficiencies in the support of these finely tuned and highly demanding neural subnetworks, all of which feature only modest reserves due to their evolutionary pressure. Thus the subnetwork involved and prionic response—i.e., the diagnosis—dictates the priorities of the evaluation and treatment, even though all six of the major groups of drivers listed above may contribute to the insufficiency.

For compromise of the subnetwork subserving neuroplasticity (at all levels, from molecular to cellular to synaptic to systemic), and leading to diseases including Alzheimer’s (including PCA, PPA (lv), and those cases of corticobasal syndrome associated with AD), diffuse Lewy body disease, LATE, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration, as noted above, the rationale for evaluation and treatment based on this theory has been published [

72]. As noted in

Table 1 above, contributors to non-amnestic presentations of AD tend to be different from those of more classical, amnestic AD, and thus evaluation and treatment should take that into effect, with focus on toxin exposures and chronic, tick-borne infections in addition to the typical metabolic and inflammatory contributors. For DLBD, the focus should include pesticides, heavy metals, and air pollutants.

From these evaluations, the various contributors to the degenerative process are identified and then addressed therapeutically. Infections such as

HSV-1 are readily treated. Metabolic dysfunction may be corrected with a plant-rich, mildly ketogenic diet and lifestyle optimization (including both aerobic exercise and strength training), or treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists, among other approaches. Oral dysbiosis and gut dysbiosis are readily detected and treated (and it is noteworthy that studies of the brain microbiome have repeatedly revealed oral microbiome members [

33]). Sleep apnea, a common contributor to cognitive decline, is also readily detected and addressed. Toxins and toxicants from the three major groups—inorganics, organics, and biotoxins—are also detectable, typically in blood and urine samples, and detoxification methods are in widespread use.

Adapting this approach to the major neurodegenerative diseases affecting motor modulation—Parkinson’s, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration—shifts focus to prioritize organic toxicants such as trichloroethylene, dieldrin, and paraquat, while retaining the overall evaluation and treatment targeting the six groups of contributors listed above. Furthermore, in addition to the production of anti-microbial α-synuclein in patients with Parkinson’s (as well as diffuse Lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy), the surprising identification of a Parkinson’s-specific profile in sebum years before the appearance of motor symptoms supports the notion of a response to pathogens, since sebum possesses antibacterial and antifungal properties [

78].). Furthermore, the recent association of bacteria of the genus

Desulfovibrio with Parkinson’s disease [

75], along with the discovery of the gut microbiome’s potential role in Parkinson’s [

79], emphasizes the need for the evaluation of the gut microbiome in patients with possible Parkinson’s disease or risk for Parkinson’s disease. Optimal treatment would then require inclusion of detoxification, mitochondrial support and/or enhancement and/or transfusion [

80], and optimization of the gut microbiome, along with addressing common parameters such as systemic inflammation and insulin resistance [

81].

Modification to treat ALS requires the recognition that the system that has evolved to mediate massive amplification, from thought to maximal strength and movement almost instantaneously, possesses a vulnerability in glutamate excitotoxicity, for example in the clearance of the excitotoxic neurotransmitters glutamate and aspartate [

82] or in the presence of an exogenous excitotoxin such as β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) [

83]. Many potential contributors to this excitotoxic excess have been identified, such as Lyme disease [

84], cyanobacteria [

85], heavy metals (lead, mercury) [

86], copper deficiency [

87], retroviruses [

88], and professional athleticism [

89], among many others. A review of patients with definitively diagnosed ALS who nevertheless achieved sustained improvement in at least one objective measure (as compared to typical progressive ALS patients) revealed associations with numerous medications and supplements such as azathioprine, glutathione, curcumin, vitamin D, and luteolin, among others [

90]. Thus optimal treatment should identify the cause(s) of the reduced glutamate/aspartate clearance, as well as addressing the other parameters of trophic support, energetics, etc. listed above.

Modification to treat age-related macular degeneration increases the priority of evaluation to metabolic demand and the complement system: demand related to the requirement for the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) to keep up with the exigency to phagocytose the photoreceptor outer segments (which increases with longer daily light exposure, especially blue light, and is compromised by living at high altitude, cigarette smoking, sleep apnea, and other factors), and complement to respond to the spillover (thus the common CFH mutations lead to enhanced inflammation and increase AMD risk, analogous to the ApoE ε4 allele in Alzheimer’s risk).

The Failure of Simple Models of Alzheimer’s Disease

Previous theories of Alzheimer’s disease have not led to effective treatment. However, the theory described here has received support both from anecdotal studies in over 100 patients [

18,

19,

20,

91], and from multiple clinical trials, in which over 70% of the patients showed improvement (not simply a slowing of decline), including some patients increasing their MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) scores (by external raters) from 19/30 to 30/30 [

16].

These patients were evaluated for the many potential contributors to synaptoclastic and synaptoblastic signaling, from infectious agents to other inflammagens to insulin resistance to sleep apnea to nutrient and hormonal deficiencies, as well as the other contributors listed above. These were then targeted with a personalized, precision medicine protocol, using a computer-based algorithm derived from the theory described here. It is noteworthy that some of the earlier reported patients have now been on this protocol for over 10 years, with sustained improvement, suggesting that the root cause contributors to the cognitive decline are indeed being impacted [

58].

The model presented here also offers explanations for many of the otherwise unexplained results reported. For example, the model predicts that the removal of the anti-microbial amyloid-β with an antibody may do little if the upstream drivers of synaptoclastic signals are not identified and removed, and in fact may lead to decline if there is ongoing exposure to pathogens (which has been observed in several patients). However, these same antibodies may potentially be highly effective were they to be combined with the rest of the protocol, and administered after any identified pathogens had been treated and insults addressed. A similar argument can be made for removing another endogenous anti-microbial, p-tau.

In contrast, novel pharmaceuticals that target the various contributors to the equations above may prove useful as part of an overall protocol, especially if tested in those individuals shown to have the respective contributors, such as specific toxins associated with air pollution or specific insulin signaling or specific trophic factor reduction. This offers new avenues for therapeutic development, based on personalized, precision-medicine models.

Another implication of the theory is that a monotherapy—any monotherapy—is unlikely to be as effective for patients with Alzheimer’s or other neurodegenerative diseases as a targeted, comprehensive protocol. This provides some insight into why so many clinical trials of pharmaceutical agents have failed despite supportive pre-clinical data. However, these same agents may prove effective when used as part of a targeted, combination therapy.

Furthermore, the network that is being targeted therapeutically is highly unlikely to function as a linear system, and therefore, the idea that any combination therapy must include only agents that show a statistically significant effect when used alone (along with the related notion that one can simply add up the effects of different agents to determine the effect of a combination) is invalid. In other words, optimal combinations may indeed turn out to include agents that show no significant effect when used as monotherapies. This suggests that determining the contributions from each of the components of a combination therapy may achieve more success by subtracting a single agent from a combination instead of testing single agents alone, or by using AI (artificial intelligence)-based methods to evaluate many varied combinations.

Pr2 theory also suggests that Alzheimer’s disease should be readily preventable in a cost-effective, globally-scalable way, using a sieve approach: in a given population, adoption of a basic set of practices that increases synaptoblastic signals and reduces synaptoclastic signals—such as insulin-sensitizing diet and identifying and treating sleep apnea, among others—should reduce population risk; those at high risk would take a second step of evaluation for the many parameters that affect the synaptoclastic ratio and address those specifically; the small minority that would go on to display symptoms would have these addressed early on with deeper studies on what failed in prevention, and be treated with a more extensive, targeted protocol; and those rare individuals failing even that would become in-patients briefly so that more extensive evaluation and optimal treatment could be undertaken. This approach would allow the direction of the majority of resources to those in greatest need, and render the overall program cost-effective. Given the results of proof-of-concept clinical trials, in which more than 70% of patients with MCI and early dementia demonstrated cognitive improvement [

16,

17], early evaluation and treatment have the potential to reduce the societal burden of dementia markedly.

As noted above, previous, mono-etiological models of Alzheimer’s disease have failed in the translation to effective therapy. However, there are features of the various theories that are compatible with observations, and those features all fit within the context of the theory presented here. For example, the infectious theory of Alzheimer’s fits well with the finding that many patients with Alzheimer’s do indeed have pathogens within their brains (and associated inflammation), such as

Herpes simplex [

92]. However, this does not explain the many who have these same pathogens but do not develop Alzheimer’s disease, nor does it explain the many other risk factors, nor does it explain the many who develop Alzheimer’s disease in the absence of those pathogens. Thus the case for infections as contributory to Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology is strong, and fits well within the current theory, but there is no evidence that these are either necessary or sufficient.

Similarly, the notion that Alzheimer’s disease is “type 3 diabetes” [

93] is only partially correct—just as for infections, insulin resistance is neither necessary nor sufficient for Alzheimer’s disease, although it is a common contributor, and fits well within the model proposed here.

Both amyloid-β peptide and tau have been shown to possess prionic properties, i.e., to replicate in a process that does not require them to carry a nucleic acid. This is an important feature of the plasticity of the network itself: biological systems with a single goal outcome and no requirement for amplification—such as serum pH—feature negative (homeostatic) feedback; in contrast, biological systems that feature alternating goal outcomes and require amplification as part of the switching—such as blood clotting—feature positive feedback, i.e., prionic loop feedback. The synaptoblastic-synaptoclastic signaling switching mediated by APP (part of the overall connection vs. protection mode switch), based on the many contributory factors listed above, features prionic loop feedback: amyloid-β peptide inhibits the α-secretase cleavage of APP [

23], and conversely, sAPPα is a potent inhibitor of the β-secretase, BACE1 [

50]. Thus this signaling tends toward one of two stable states—synaptoblastic signaling or synaptoclastic signaling—and there is a threshold for switching states. In other words, APP signaling acts essentially as a bistable threshold switch, leading to either synaptoblastic or synaptoclastic signaling/outcomes. Prionic signaling is thus a property of the system, and a mediator of the pathophysiology, but there is no evidence that horizontal spread is a common cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

Similarly, none of the mono-etiological, non-network theories—those noted above or the amyloid cascade hypothesis [

94] or the tau hypothesis [

95] or the oxidative/nitrosative stress theory [

96] or the myelin theory [

97] or others—offers adequate explanation for the remarkably diverse set of risk factors for Alzheimer’s, nor does it offer a clear program for prevention, nor is it supported by evidence of translation to clinical efficacy.

Clinical Outcomes of the Pr2 Theory

The theory is supported by patient outcome data in patients with MCI and dementia, in two proof-of-concept trials [

16,

17], with an ongoing randomized controlled trial [

98]. Some illustrative examples include the following:

Patient 1

A 75-year-old woman presented with paraphasic errors, depression, and difficulty with spelling, shopping, cooking, and working at the computer. Her symptoms progressed, and she developed memory loss. Evaluation revealed her to be heterozygous for the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (ApoE 3/4). An amyloid PET scan (florbetapir) was positive. MRI revealed a hippocampal volume at the 14th percentile for her age. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was 1.1 mg/L, fasting insulin 5.6 mIU/L, hemoglobin A1c 5.5%, homocysteine 8.4 micromolar, vitamin B12 471 pg/mL, free triiodothyronine (free T3) 2.57 pg/mL, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.21 mIU/L, albumin 3.7 g/dL, globulin 2.7 g/dL, total cholesterol 130 mg/dL, triglycerides 29 mg/dL, serum zinc 49 mcg/dL, complement factor 4a (C4a) 7990 ng/mL, transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) 4460 pg/mL, and matrix metalloprotease-9 497 ng/mL.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) associated with AD was diagnosed, and she began a trial of an anti-amyloid antibody (solanezumab), but was not told whether she was in the treatment group or the control group. With each administration, her cognition became worse for 3–5 days, then returned gradually toward her previous MCI status. After she had become worse after each of the first several treatments, she discontinued her participation in the study.

With a personalized treatment protocol [

58], her MoCA score increased from 24 to 30 over 17 months. Hippocampal volume increased from the 14

th percentile to the 28

th percentile for her age. Her symptoms resolved, and she has sustained improvement for seven years, with one secondary decline that was associated with sleep apnea, new exposure to toxins, and a chronic sinusitis, all of which were addressed with improvement in cognition.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old woman presented with visual complaints of nine years duration, ultimately diagnosed as being due to posterior cortical atrophy (PCA). She lost the ability to read, use the computer, and drive. She became dependent on her spouse. Evaluation revealed severe atrophy of the parietal lobes (<1st percentile), with lesser atrophy of the occipital lobes (10th percentile) and hippocampi (6th percentile). Plasma p-tau 181 was elevated at 1.72 pg/mL (normal range 0-0.97 pg/mL). She was treated with donepezil, without improvement.

She was then found to have a Bartonella infection, mild sleep apnea (apnea/hypopnea index of 9.9), and urinary mycotoxin analysis was positive for ochratoxin, aflatoxin, trichothecenes, gliotoxin, and zearalenone. Antibodies to Borrelia and Bartonella were positive (IgM). Urinary mercury was increased at 10 mg/g of creatinine (normal < 1.3), and lead was also increased at 6.2 mg/g creatinine (normal < 1.2).

With treatment of her infection, reduction of urinary mycotoxins and heavy metals, treatment of sleep apnea, and improved metabolic status, her symptoms improved. She regained her ability to read and use the computer. Her MRI revealed marked improvements in volumetrics: her parietal lobe volume increased from <1st percentile to the 22nd percentile, her occipital lobe volume increased from the 10th to 25th percentile, and her hippocampal volume increased from the 6th to 32nd percentile. Her p-tau 181 improved modestly, from 1.72 pg/mL to 1.52 pg/mL.

Patient 3

A 69-year-old professional man presented with 11 years of slowly progressive memory loss, which had accelerated over the last one to two years. Quantitative neuropsychological testing revealed reductions in verbal learning, auditory delayed memory, attention, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility. He lost the ability to add columns of numbers rapidly in his head, something he had been able to do for most of his life. He was found to be ApoE 3/4. A fluorodeoxyglucose PET was read as showing a pattern typical for early Alzheimer’s, with reduced glucose utilization in the parietotemporal cortices bilaterally and left > right temporal lobes.

He was advised that, given his status as an AD patient and his progression, as well as his poor performance on the cognitive tests, he should begin to “get your affairs in order”. His business was in the process of being shut down due to his inability to continue work. However, with treatment, his symptoms resolved, his cognitive testing improved (CVLT-II improved from the 54th to the 96th percentile, auditory delayed memory improved from the 13th to the 79th percentile, and reverse digit span improved from the 24th to the 74th percentile), his calculation ability returned, and he was able to return to normal working ability. He has sustained his improvement for 11 years.

Implications of the Pr2 Theory

The Pr2 theory has a number of implications for the evaluation, treatment, prevention, and understanding of neurodegenerative diseases:

•Removing prions such as amyloid-β or α-synuclein may potentially lead to worsening of symptoms and the degenerative process if these are targeted therapeutically prior to addressing the upstream inducers of the prions, such as various pathogens. If prions are to be removed, the best timing would be after the inducers have been treated, and the best predicted rate of removal would be over months or years rather than weeks.

•Since neurodegenerative diseases represent complex network insufficiencies rather than simple diseases, adjusting multiple factors rather than complete suppression of one may lead to the best outcomes—multiple modest changes instead of one massive change.

•The Pr2 theory suggests multiple new and recent therapeutic targets, such as various infectious agents (e.g., Herpes virus family members, fungal species, and bacterial species such as P. gingivalis), toxins (inorganic toxicants, organic toxicants, and biotoxins), gastrointestinal hyperpermeability, sleep apnea, oral and CNS dysbiosis, innate immune system mechanisms (which may be treated with specialized pro-resolving mediators, mast cell inhibition, and other anti-inflammatory therapeutics), support for the adaptive immune system, energetic support (e.g., ketones, creatine, and EWOT (exercise with oxygen therapy)), glycotoxicity (e.g., GLP-1 agonists or ketogenic diets), neurotrophins (such as BDNF and NGF), and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-related stress mediators.

• The prion paradox—the fact that prions are by definition proteinaceous infectious agents, and have been identified in all of the major neurodegenerative diseases (Aβ, p-tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, and PrPSc), yet there is only evidence for horizontal transfer of prions (“prion infection”) in a tiny fraction of cases—is explained by the Pr2 theory: prions play key physiological roles as proteinaceous anti-infectious agents (praions), as physiological response amplifiers of signals (prasons, i.e., mediators of bistable switching systems), as mediators of protein-inherited traits (printons), and as pre-inflammatory immune mediators (priions). Thus in most patients with neurodegenerative diseases, prions are generated endogenously in response to various insults such as chronic infections or toxin exposure, and their replicative nature offers an advantage as responders to multiplying pathogens. Furthermore, the stability of at least some prions, such as PrPSc, may allow horizontal transfer of herd protection against pathogens.

•The Pr2 theory predicts that most patients who develop neurodegenerative diseases will have more than one contributor, and that all of the contributors will compromise the implicated neural subnetwork’s energetic support, trophic support, or neurotransmitter(s), and/or increase the demand via inflammation, toxicity, or stress, either directly or indirectly. Therefore, identifying and addressing these contributors is important for optimal outcomes. The therapeutic method of simply removing the associated “misfolded” proteins is unlikely to offer optimal efficacy. Furthermore, the constants associated with each of the many potential contributors should be calculable from patient data and AI, leading to more exacting prognostics and improved outcomes.

•Which neurodegenerative disease develops in any given individual is specified by the inducing insults, their routes of entry, and the prionic response.

•Reducing the overall burden of neurodegenerative disease should be enhanced by early detection methods (such as sensitive measurements of p-tau 217 in plasma) and wearables (such as continuous glucose monitors, continuous ketone monitors, and sleep trackers), which reveal suboptimal parameters such as glucose spikes and troughs, loss of metabolic flexibility, reduction in deep sleep, suboptimal nocturnal oxygenation, and many other parameters critical for optimal neural protection. In the long run, it should be possible to develop a real-time analysis of cerebral supply/demand status, allowing earlier detection and ensuring prevention for virtually all.

Summary

1. A unifying theory of neurodegenerative disease, the Pr2 theory, is proposed, describing the origin, pathophysiology, optimal evaluation and treatment of patients, explanation of observations not explained by previous theories, and implications for further research and translation.

2. The theory proposes that the origin of all of the major neurodegenerative diseases is in antagonistic pleiotropy, which, through repeated evolutionary selection for performance over durability, has led to highly functional and finely tuned neural subnetworks subserving key survival features such as lethal force and behavioral modification, at the expense of durability and reserve.

3. The theory is focused on the physiology associated with the causes of neurodegeneration rather than the pathology that has been the focus of the lion’s share of the research and attempted treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

4. The Pr2 theory proposes that neurodegenerative diseases represent neural subnetwork insufficiencies due to chronic or repeated reductions in supply (energetics, trophic support, and/or neurotransmitters) and/or increases in demand (due to inflammation, toxins, or stress). The symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases then arise ultimately from a reduction in net synaptic function beyond that required for daily function, a cumulative loss that may take many years to occur.

5. The Pr2 theory resolves the prion paradox, arguing that the prions in most cases of neurodegenerative disease are generated endogenously, typically as anti-infectious agents (“praion” effect of prions).

6. The priionic role of prions allows sequestration and destruction of small numbers of pathogens (the praionic effect) without a pro-inflammatory, function-disruptive effect on neural architecture. Thus pathogens may be contained for decades with minimal functional neural compromise. During this period, there is an anti-inflammatory balancing effect of the degeneration-unassociated forms such as PrP

C and sAPPα (and potentially β-synuclein) [

99]. However, when inflammatory responses, whether due to genetics (such as ApoE4) or increased pathogen burden, failure of containment, or other factors, supervene, the priionic effect is replaced as the dominant effect by inflammatory responses such as microglial activation, mast cell activation, astroglial activation, and inflammatory cytokine signaling, leading to neurodegeneration.

7. In Alzheimer’s disease, the prasonic role of prions as mediators of anti-homeostatic, bistable switching mechanisms, is observable as a mode switch (analogous to switching from sleep to wakefulness), from connection to protection, affecting pathways throughout the body, from thrombosis to synaptogenesis to antimicrobial peptide and protein synthesis to metabolism to blood-brain barrier integrity, as well as numerous others. This protective mode need not progress to degeneration, and indeed there is ample evidence from yeast prions that switching back to a non-prion mode is common [

100,

101].

8. The Pr2 theory implies that optimal treatment will require identifying and addressing the various contributors to neurodegeneration in a personalized, precision medicine approach.

9. Initial translation of the Pr2 theory to a precision medicine approach to cognitive decline has led to superior outcomes compared to other therapeutic approaches [

16,

17], and at least in some cases, sustained improvement for over a decade has been achieved [

58].

Figure 2.

APP interactome, indicating the multiple links to signaling and migration pathways. From reference [

102].

Figure 2.

APP interactome, indicating the multiple links to signaling and migration pathways. From reference [

102].

Figure 3.

Genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and genes differentially methylated in Alzheimer’s disease patients form a “susceptibility network” for Alzheimer’s. Most of these comprise a tight interaction cluster that includes APP, and function in cell-extracellular matrix interactions, cell process movement, trophic signaling, inflammatory response, stress pathways, and related pathways. From reference [

103], adapted by [

102]. .

Figure 3.

Genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and genes differentially methylated in Alzheimer’s disease patients form a “susceptibility network” for Alzheimer’s. Most of these comprise a tight interaction cluster that includes APP, and function in cell-extracellular matrix interactions, cell process movement, trophic signaling, inflammatory response, stress pathways, and related pathways. From reference [

103], adapted by [

102]. .

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr. Rammohan Rao and Dr. Alexei Kurakin for critical reading of the manuscript, and to Molly Susag for administrative assistance. Some of the work providing background for this manuscript was supported by the Four Winds Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, or the Alzheimer’s Association.

References

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney P, Park H, Baumann M, Dunlop J, Frydman J, Kopito R, McCampbell A, Leblanc G, Venkateswaran A, Nurmi A, Hodgson R Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: implications and strategies. Transl Neurodegener 2017, 6, 6.

- Arnsten AFT, Datta D, Del Tredici K, Braak H Hypothesis: Tau pathology is an initiating factor in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2021, 17, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Prusiner SB Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982, 216, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt S, Puli L, Patil CR Role of reactive oxygen species in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov Today 2021, 26, 794–803. [CrossRef]

- Seaks CE, Wilcock DM Infectious hypothesis of Alzheimer disease. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008596.

- Kciuk M, Kruczkowska W, Gałęziewska J, Wanke K, Kałuzińska-Kołat Ż, Aleksandrowicz M, Kontek R Alzheimer’s Disease as Type 3 Diabetes: Understanding the Link and Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 11955. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M Why do trials for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2017, 26, 735–739. [CrossRef]

- Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR, Boyle PA, Arfanakis K, Rademakers R, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, Brayne C, Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Chui HC, Fardo DW, Flanagan ME, Halliday G, Hokkanen SRK, Hunter S, Jicha GA, Katsumata Y, Kawas CH, Keene CD, Kovacs GG, Kukull WA, Levey AI, Makkinejad N, Montine TJ, Murayama S, Murray ME, Nag S, Rissman RA, Seeley WW, Sperling RA, White III CL, Yu L, Schneider JA Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain 2019, 142, 1503–1527.

- Le Guen Y, Belloy ME, Grenier-Boley B, de Rojas I, Castillo-Morales A, Jansen I, Nicolas A, Bellenguez C, Dalmasso C, Küçükali F, Eger SJ, Rasmussen KL, Thomassen JQ, Deleuze JF, He Z, Napolioni V, Amouyel P, Jessen F, Kehoe PG, van Duijn C, Tsolaki M, Sánchez-Juan P, Sleegers K, Ingelsson M, Rossi G, Hiltunen M, Sims R, van der Flier WM, Ramirez A, Andreassen OA, Frikke-Schmidt R, Williams J, Ruiz A, Lambert JC, Greicius MD, Arosio B, Benussi L, Boland A, Borroni B, Caffarra P, Daian D, Daniele A, Debette S, Dufouil C, Düzel E, Galimberti D, Giedraitis V, Grimmer T, Graff C, Grünblatt E, Hanon O, Hausner L, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Holstege H, Hort J, Jürgen D, Kuulasmaa T, van der Lugt A, Masullo C, Mecocci P, Mehrabian S, de Mendonça A, Moebus S, Nacmias B, Nicolas G, Olaso R, Papenberg G, Parnetti L, Pasquier F, Peters O, Pijnenburg YAL, Popp J, Rainero I, Ramakers I, Riedel-Heller S, Scarmeas N, Scheltens P, Scherbaum N, Schneider A, Seripa D, Soininen H, Solfrizzi V, Spalletta G, Squassina A, van Swieten J, Tegos TJ, Tremolizzo L, Verhey F, Vyhnalek M, Wiltfang J, Boada M, García-González P, Puerta R, Real LM, Álvarez V, Bullido MJ, Clarimon J, García-Alberca JM, Mir P, Moreno F, Pastor P, Piñol-Ripoll G, Molina-Porcel L, Pérez-Tur J, Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Royo JL, Sánchez-Valle R, Dichgans M, Rujescu D () Association of Rare APOE Missense Variants V236E and R251G With Risk of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 652–663.

- Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Ziolko SK, James JA, Snitz BE, Houck PR, Bi W, Cohen AD, Lopresti BJ, DeKosky ST, Halligan EM, Klunk WE (2008) Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol, 1517.

- Jones MK, Nair A, Gupta M (2019) Mast Cells in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front Cell Neurosci.

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M, Kanekiyo M, Li D, Reyderman L, Cohen S, Froelich L, Katayama S, Sabbagh M, Vellas B, Watson D, Dhadda S, Irizarry M, Kramer LD, Iwatsubo T (2023) Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med.

- Soscia SJ, Kirby JE, Washicosky KJ, Tucker SM, Ingelsson M, Hyman B, Burton MA, Goldstein LE, Duong S, Tanzi RE, Moir RD (2010) The Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid beta-protein is an antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One.

- Eimer W, Vijaya Kumar DK, Tanzi RE (2019) Cure Alzheimer’s Fund.

- Toups K, Hathaway A, Gordon D, Chung H, Raji C, Boyd A, Hill BD, Hausman-Cohen S, Attarha M, Chwa WJ, Jarrett M, Bredesen DE (2022) Precision Medicine Approach to Alzheimer’s Disease: Successful Pilot Project. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Sandison H, Callan NGL, Rao RV, Phipps J, Bradley R (2023) Observed Improvement in Cognition During a Personalized Lifestyle Intervention in People with Cognitive Decline. J Alzheimers Dis.

- Bredesen DE (2014) Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY).

- Bredesen DE, Amos EC, Canick J, Ackerley M, Raji C, Fiala M, Ahdidan J (2016) Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Albany NY).

- Bredesen DE, Sharlin K, Jenkins K, Okuno M, Youngberg W, al. e (2018) Reversal of Cognitive Decline: 100 Patients. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism.

- Choi CJ, Kanthasamy A, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG (2006) Interaction of metals with prion protein: possible role of divalent cations in the pathogenesis of prion diseases. Neurotoxicology.

- Ezpeleta J, Boudet-Devaud F, Pietri M, Baudry A, Baudouin V, Alleaume-Butaux A, Dagoneau N, Kellermann O, Launay J-M, Schneider B (2017) Protective role of cellular prion protein against TNFα-mediated inflammation through TACE α-secretase. Scientific Reports.

- Spilman PR, Corset V, Gorostiza O, Poksay KS, Galvan V, Zhang J, Rao R, Peters-Libeu C, Vincelette J, McGeehan A, Dvorak-Ewell M, Beyer J, Campagna J, Bankiewicz K, Mehlen P, John V, Bredesen DE (2016) Netrin-1 Interrupts Amyloid-beta Amplification, Increases sAbetaPPalpha in vitro and in vivo, and Improves Cognition in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis.

- Chakrabortee S, Byers JS, Jones S, Garcia DM, Bhullar B, Chang A, She R, Lee L, Fremin B, Lindquist S, Jarosz DF (2016) Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Drive Emergence and Inheritance of Biological Traits. Cell.

- Fioriti L, Myers C, Huang YY, Li X, Stephan JS, Trifilieff P, Colnaghi L, Kosmidis S, Drisaldi B, Pavlopoulos E, Kandel ER (2015) The Persistence of Hippocampal-Based Memory Requires Protein Synthesis Mediated by the Prion-like Protein CPEB3. Neuron.