Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

A quote from Physical Geology [1]:The objective is to raise for consideration the possibility that a sustained concentration of water vapor in our atmosphere is controlled by mechanisms other than the CO2 green house gas. The further objective is to stimulate research into other possible mechanisms for sustained increased atmospheric water vapor.

This viewpoint, as well as why water vapor gets downplayed, is also well represented by the MIT Climate Portal:… climate feedbacks are critically important in amplifying weak climate forcings into full-blown climate changes. When Milankovitch published his theory in 1924, it was widely ignored, partly because it was evident to climate scientists that the forcing produced by the orbital variations was not strong enough to drive the significant climate changes of the glacial cycles. Those scientists did not recognize the power of positive feedbacks. It wasn’t until 1973, 15 years after Milankovitch’s death, that sufficiently high-resolution data were available to show that the Pleistocene glaciations were indeed driven by the orbital cycles, and it became evident that the orbital cycles were just the forcing that initiated a range of feedback mechanisms that made the climate change.

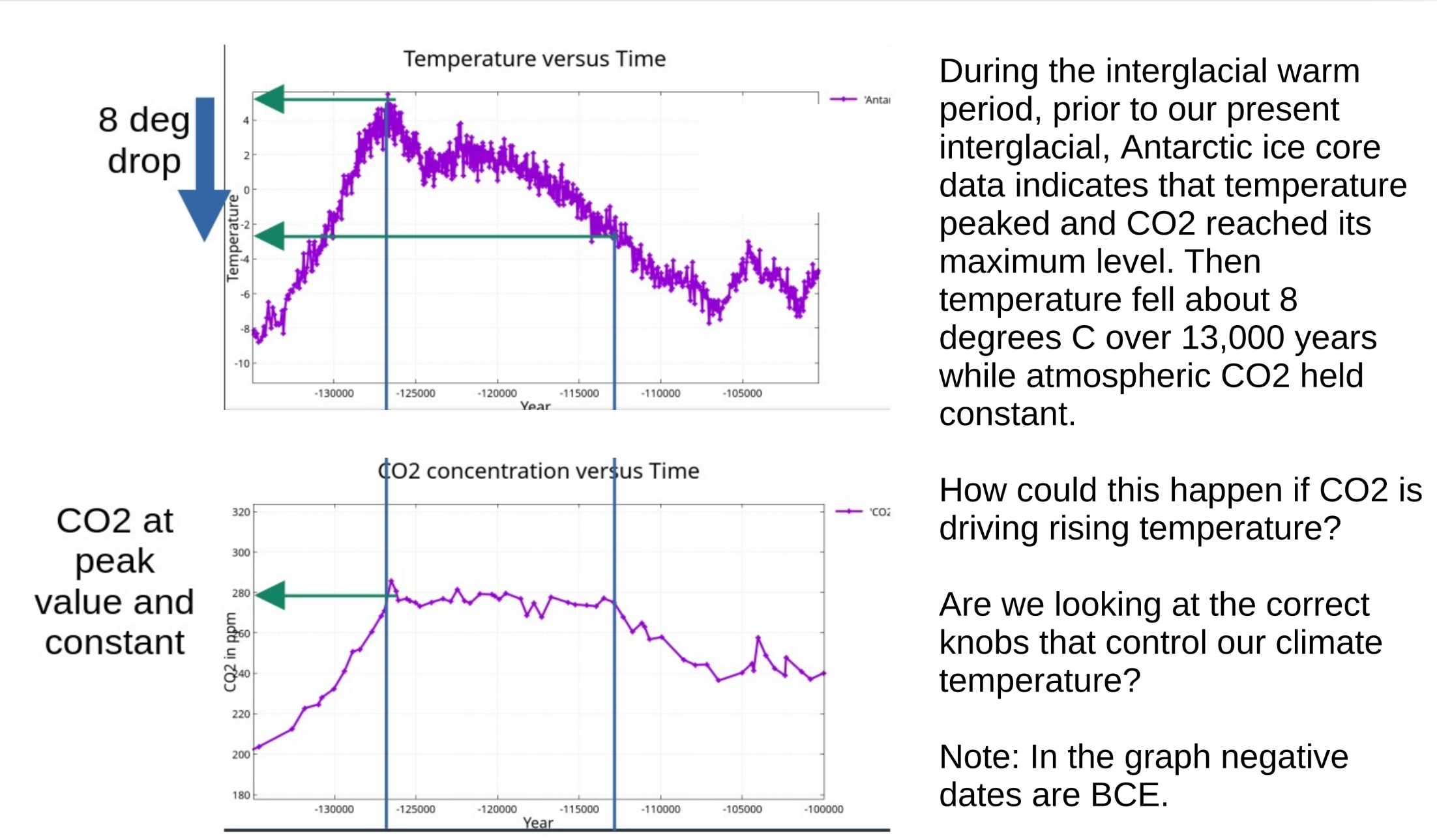

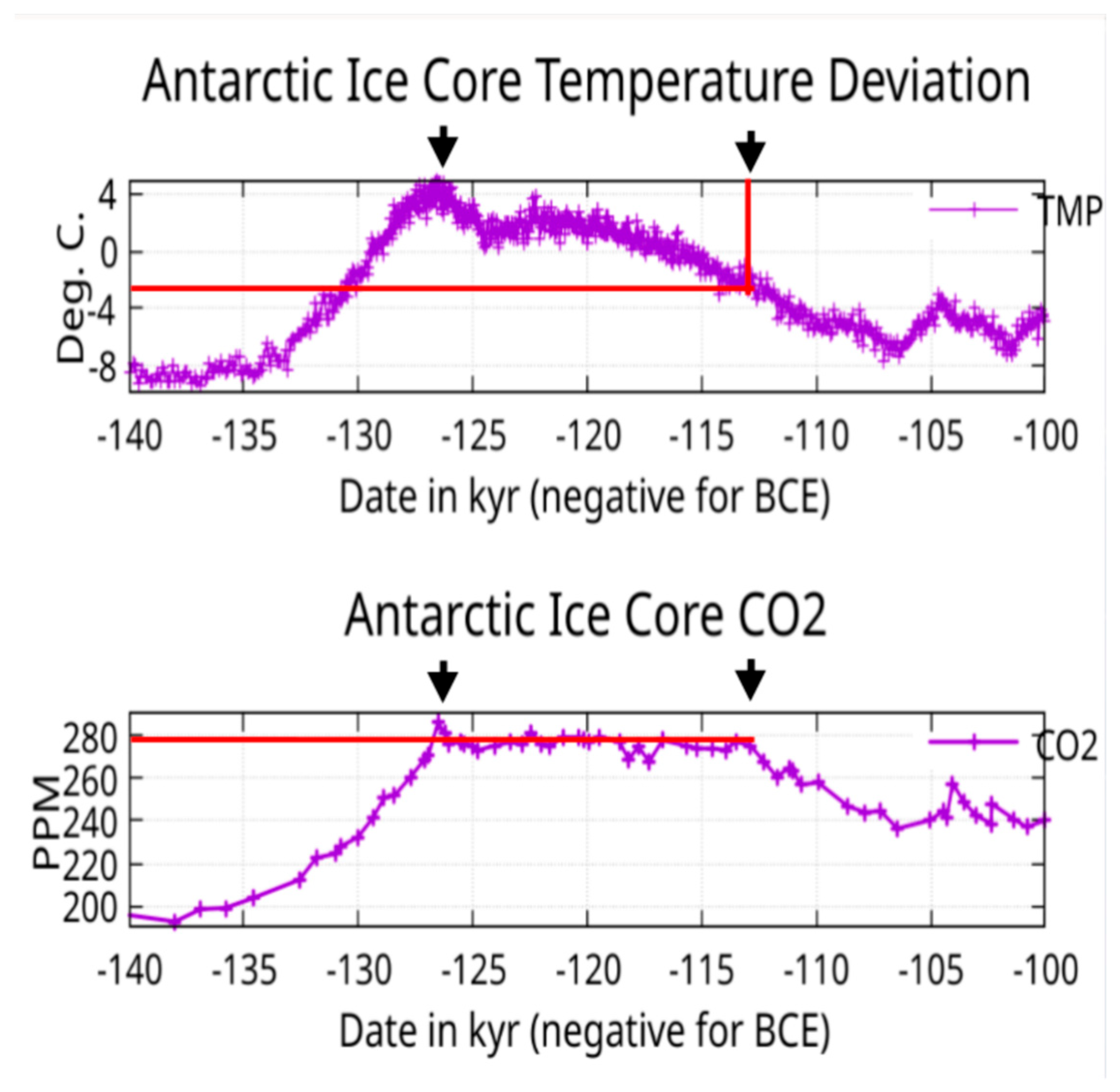

If we look at Antarctic Ice Core data over the last 800,000 years in particular, we find this warming process reversed and the climate falls into deep cooling of the atmosphere – top of Figure 1, showing this for the prior interglacial warm period. A plot of this same data over 800,000 years, with apparent smoothing, is found at https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/our-data/publication/ice-cores-and-climate-change/ Figure 3, but the reader must zoom in on the specific time interval to compare (this external figure caption references Parrenin, F. et al., https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1226368 ).https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/why-do-we-blame-climate-change-carbon-dioxide-when-water-vapor-much-more-common-greenhouse

External Forcings

Logical Issues

This statement is found to be logically false based on the data shown in Figure 1.All cases of high atmospheric CO2 concentration are associated with rising climate temperature.

So now we have to evaluate the data in Figure 1 above to decide if perhaps some transient event was involved. Exactly what does “transient” mean when CO2 concentration remained constant for 13,000 years while temperature was falling? Even on the scale of a climate change event, 13,000 years is a long time. The Younger Dryas was a major climate event but it happened over a time interval of less than 2000 years. The entire Holocene (our current interglacial) is only 11,700 years old.All cases of high atmospheric CO2 concentration are associated with rising climate temperature except in special cases where transient events may cause temperature to fall when atmospheric CO2 concentration is high.

Ice Sheet Growth and Ocean Current

The reference to Maslin [4] indicates:Plankton indicators of north Atlantic surface temperatures and deep Atlantic circulation patterns appear to corroborate this event, suggesting that the north Atlantic climate experienced a sudden cool phase resulting from a weakening of the Gulf Stream (lasting perhaps several centuries) at about 121,000 or 122,000 y.a. (Maslin 1996). After this the climate never returned to its previous warmth, although the pollen records seem to suggest that conditions more similar to those of today, lasting for perhaps 5,000 years up until around 115,000 y.a.

And:Based on the absence of IRD and other evidence of melting icebergs [5,7] during the peak Eemian, the observed freshening of the surface waters and the corresponding reduction of deep-water formation cannot be ascribed to a mystical ice surge event, ….

“The Gulf Stream is part of a larger circulation system called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)” as stated at https://skepticalscience.com/print.php?n=975 . This ocean current has a role in maintaining a mild climate in Northern Europe. If this current were interrupted then the North Atlantic could become colder and induce increased snow and ice in the north, on Greenland in particular.We therefore conclude that the E e m i a n / M I S 5e was, at least in the subtropics, and we infer globally, climatically relatively stable, the exception being a brief cold event lasting no longer than 400 years, which may have had a profound short-term effect, but no long-term influence on the climate of the Northern Hemisphere.

And:We suggest that low- δ13C water and slow current speed on Gardar Drift during the early part of the [Last Interglacial] LIG was related to increased melt water fluxes to the Nordic Seas during peak boreal summer insolation, which decreased the flux and/or density of overflow to the North Atlantic. The resumption of the typical interglacial pattern of strong, well-ventilated Iceland Scotland Overflow Water was delayed until ∼ 124 ka. These changes may have affected Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.

Since typical interglacial patterns resumed at approximately ~124 ka (~122 BCE), this seems an unlikely mechanism for extended cooling through 110,000 BCE though it might account for earlier cooling. Yet during the earliest part of the last interglacial Greenland’s ice sheet was retreating.Although future greenhouse gas forcing will be different than the insolation forcing of the LIG, our findings indicate that circulation on the Gardar Drift was weaker during the earliest part of the LIG when climate was warmer than present and the Greenland ice sheet was retreating ….

Clouds

At any given time, about two-thirds of Earth's surface is covered by clouds. Overall, they make the planet much cooler than it would be without them.

Clouds help to keep Earth cool by reflecting sunlight back out to space before it can reach the ground. But not all clouds are equal.

Shiny, white clouds reflect away more sunlight—especially when they are closer to the equator, in the parts of Earth that receive the most sun. Gray, broken clouds reflect less sunlight, as do clouds closer to the poles where less light falls.

It would be disingenuous to ignore the Nobel prize laureate John Clauser’s statements here. He is quoted as saying:Research published last year showed that Earth has been absorbing more sunlight than the greenhouse effect alone can explain. Clouds were involved, but it wasn't clear exactly how.

See: https://climaterealists.ca/clouds-not-co2-key-to-understanding-climate-nobel-winner/When clouds are added to climate models, it’s clear that there is no ‘climate emergency,’ Dr. John Clauser argues.

Volcanic Eruptions

Meteor or Comet Impacts

Model calculations indicate that it does not require a K-T-sized event, which produced the buried 180 km diameter Chicxulub impact structure in the Yucatan, Mexico, to result in atmospheric blow-out. Relatively small impact events, resulting in impact structures in the 20 km size-range can produce atmospheric blow-out. At present, however, the K-T is the only biostratigraphic boundary with a clear signal of the involvement of a large-scale impact event. The involvement of impact in other boundary events in the terrestrial stratigraphic record has been suggested but little evidence has been offered.

All major boundary events that might be similar to the K-T boundary are much older than the event associated with the K-T boundary.Impacts may also induce chemical changes in the atmosphere. These are related to the vaporization of the impacting body and a portion of the target. Considering only the contribution from the impacting body, recent calculations indicate that even relatively small impacting bodies, < 0.5 km in diameter that produce impact craters on the scale of 10 km in diameter, would inject 5 times more sulphur into the stratosphere than its present content. Larger impact events occurring on the time-scale of a million years will inject enough sulphur to produce a drop in temperature of several degrees and a major climatic shift.

Solar Activity

Radiocarbon dating works on organic materials up to about 60,000 years of age.

Water Vapor and CO2

- As greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane increase, Earth's temperature rises in response. This increases evaporation from both water and land areas. Because warmer air holds more moisture, its concentration of water vapor increases Steamy Relationships: How Atmospheric Water Vapor Amplifies Earth's Greenhouse

- If the temperature rises, the amount of water vapor rises with it. But since water vapor is itself a greenhouse gas, rising water vapor causes yet higher temperatures. We refer to this process as a positive feedback, and it is thought to be the most important positive feedback in the climate system Why do we blame climate change on carbon dioxide, when water vapor is a much more common greenhouse gas? | MIT Climate Portal

Water vapor begets warming begets more water vapor.Theory, observations, and modeling results all show that as global temperatures warm, the mean atmospheric moisture content increases …. Coupled with a slower rate of increase of precipitation (~1%–3% K−1 for precipitation as compared with the Clausius–Clapeyron rate of 7% K−1 for lower tropospheric water vapor; ... this leads to the conclusion that the convective mass flux of moisture from the boundary layer to the free troposphere must decrease … while the atmospheric moisture residence time must increase [12].

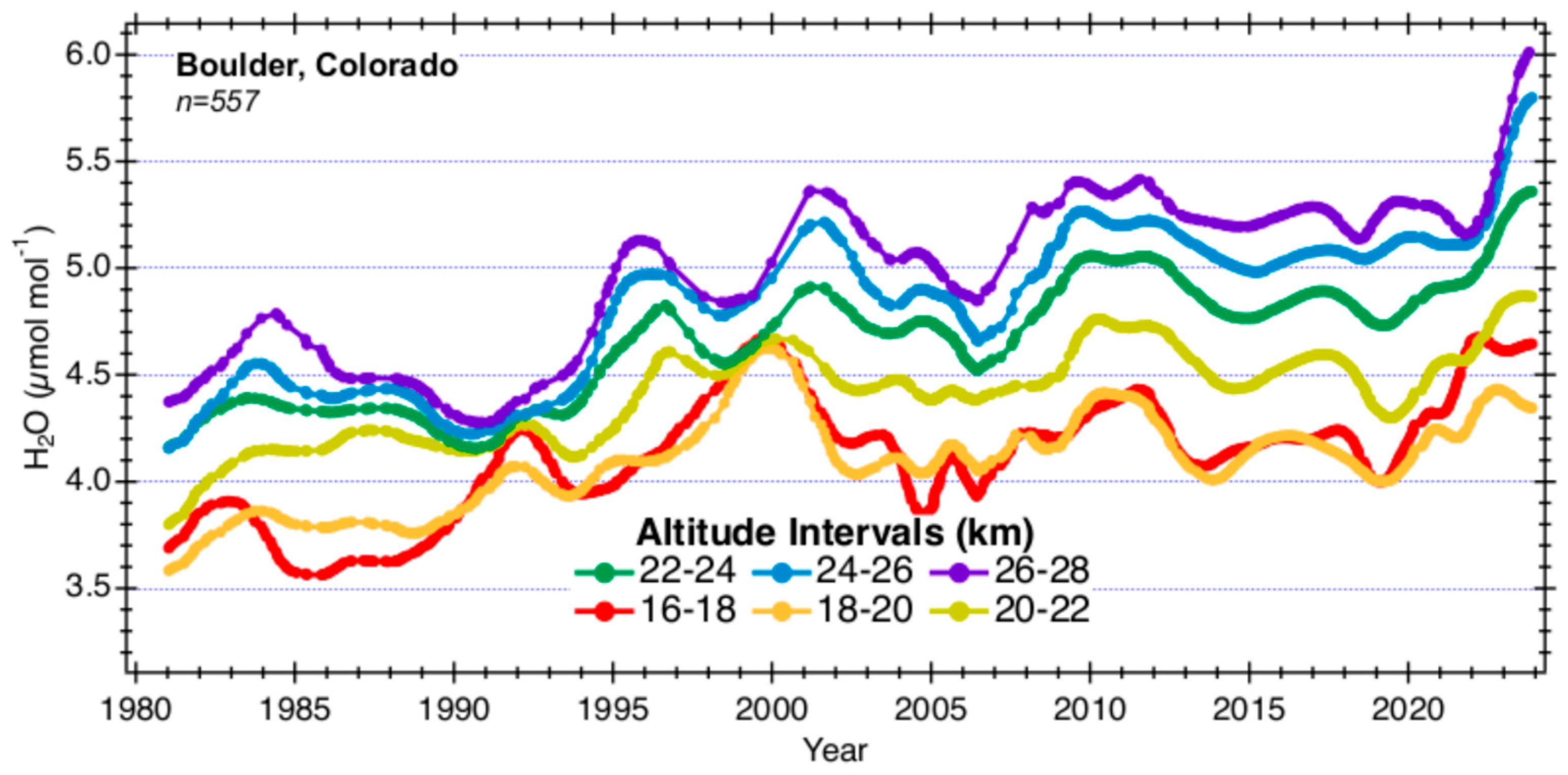

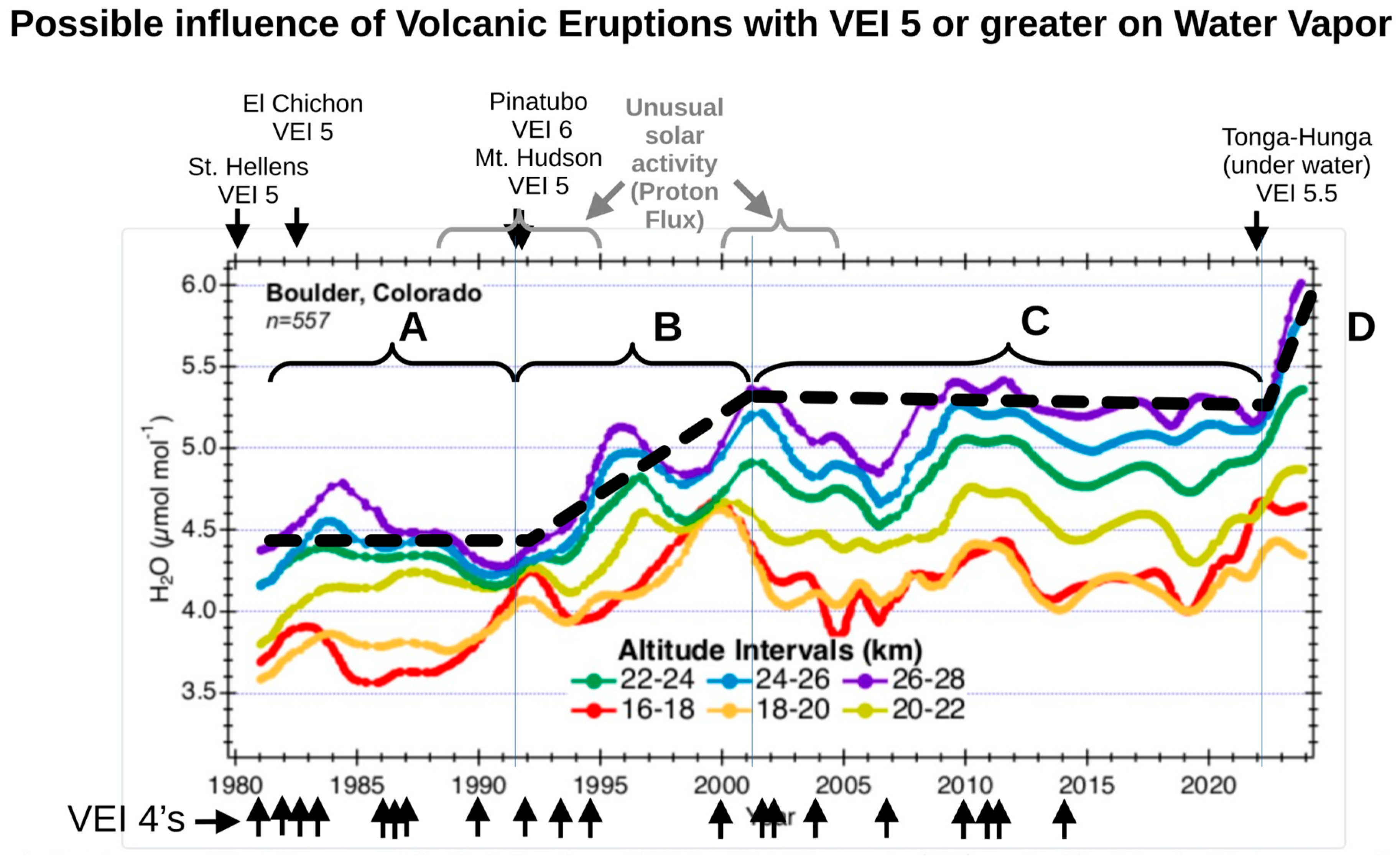

Volcanic Eruptions and Water Vapor

Most relevant to our study is water vapor’s effects on the Earth’s energy budget, influencing both the incoming solar radiation and outgoing heat (IR). Variations in the amounts of water vapor in the atmosphere are natural and normal, but changes in its vertical distribution, especially in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere, may be indicative of changes in the Earth’s climate.

Other work [15] particularly supports a cooling of the southern hemisphere in 2022 and 2023. However a two year period is short on the scale of climate events. If increased atmospheric water vapor is sustained then it may warm the earth for many years ( https://www.space.com/tonga-eruption-water-vapor-warm-earth and https://news.ucar.edu/132867/volcanic-eruption-dramatically-increased-water-vapor-stratosphere ).“… a cooling of up to −4 K was observed in the mid-stratosphere, persisting for over a year since February, with over 60% attributed to WV radiative cooling. Conversely, in the lower stratosphere, ~50% of the observed 1–2 K warming was attributed to the radiative heating of large particles that formed in upper layers and settled down gravitationally.”

Water Vapor from Jet Airplanes

Recent estimates of jet fuel use correspond to one day’s worth of global aviation industry demand of 336 million gal/day or 122 billion gallons per year, https://www.opis.com/blog/2025-likely-to-bring-lower-jet-fuel-prices-higher-demand/ . This would correspond to 1.231*122 = 150 billion gallons of water or 568 Tg of water. Tonga-Hunga is estimated to have ejected 150 Tg of water vapor into the upper atmosphere. So these aircraft are injecting about 3.8 times as much water into the atmosphere as Tonga-Hunga. This happens over a year rather than over a couple of weeks. However aircraft travel year round so this is a sustained injection of water vapor. Does this sustained injection of water vapor lead to higher sustained atmospheric water vapor or does it all condense out of the atmosphere? Estimates indicate that only a few percent of anthropogenic radiative forcing is due to aviation [17] suggesting that the water vapor is assumed to condense out of the atmosphere.The trillions of cubic feet of frozen water vapor created by jet aircraft every year (mostly in the northern hemisphere) is in the form of expanding gaseous clouds of microcrystals which continue to rise from the lower stratosphere, collecting and building up in the mesosphere.

Climate Models and Glacial Inception

This indicates that the 30 year averaging period often used to define “climate” data was forced rather than scientifically defined. So there may be a problem with the standard definition of a “climate” value for a given measured variable.The general recommendation is to use 30-year periods of reference. The 30-year period of reference was set as a standard mainly because only 30 years of data were available for summarization when the recommendation was first made.

Another example [22]:Fifth, CCSM4 has a cold bias in northern Canada and northern Siberia41 that predisposes the model toward forming permanent snow cover in a cooler climate. However, these are mostly cold-season biases36; in spring-summer, the terrestrial cold bias is smaller, while the Canadian Archipelago even has a weak warm bias42. Nevertheless, the model produces too much snow cover in its 20th century transient simulation over Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, and much of northern Canada (including Baffin), which are glacial inception regions in the model42.

This allows for the to artificial acceleration of the external forcings, in this case orbital parameters and GHGs concentration, which, considering that the atmosphere and ocean are also the most computationally expensive parts of an Earth system model results in an effective speed-up of the model.

Until climate models can match the prior interglacial into glacial inception and rise out of that glacial into the current interglacial, models are still in the development phase and should be used with considerable caution to predict future climate attributes.The glacial inception simulations presented here are a first step towards simulating the full last glacial cycle with CLIMBER-X.

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Earle S. Physical Geology. 2nd ed. Victoria BC, editor. British Columbia: B C campus; 2019.

- Jouzel, J., et al. 2007. EPICA Dome C Ice Core 800KYr Deuterium Data and Temperature Estimates. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series # 2007-091. NOAA/NCDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA.

- Bereiter, B.; Eggleston, S.; Schmitt, J.; Nehrbass-Ahles, C.; Stocker, T.F.; Fischer, H.; Kipfstuhl, S.; Chappellaz, J, Antarctic Ice Cores Revised 800KYr CO2 Data, Contribution date: 2015-02-04, World Data Center for Paleoclimatology, Boulder and NOAA Paleoclimatology Program.

- Maslin, M., M. Sarnthein, J. J. Knaack, Subtropical Eastern Atlantic Climate During the Eemian, (1996), Naturwissenschaften, Spring-Verlag.

- Hodell, David A., Emily Kay Minth, Jason H. Curtis, I. Nicholas McCave, Ian R. Hall, James E.T. Channell, Chuang Xuan, Surface and deep-water hydrography on Gardar Drift (Iceland Basin) during the last interglacial period, (2009), Earth and Planetary Science Letters,. [CrossRef]

- Jakob, Christian, edited by Gaby Clark, reviewed by Andrew Zinin, Global warming is changing cloud pattrens. That means more global warming, The Conversation, Phys.org, https://phys.org/news/2025-06-global-cloud-patterns.html.

- S.D. Burgess, J.A. Vazquez, C.F. Waythomas, K.L. Wallace, U–Pb zircon eruption age of the Old Crow tephra and review of extant age constraints, Quaternary Geochronology, Volume 66, 2021, 101168, ISSN 1871-1014, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1871101421000194). [CrossRef]

- Dee, Michael, Andrea Scifo , Tarun Rohra, Jente Joosten, Margot Kuitems , Wesley Vos, Sturt Manning and Thorsten Westphal, Radiocarbon evidence over the apparent grand solar minimum around 400 BCE, Radiocarbon (2025), 67, pp. 265–274, Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- van Wijngaarden, W. A. and W. Happer, Dependence of Earth’s Thermal Radiation on Five Most Abundant Greenhouse Gases, arXiv:2006.03098v1 [physics.ao-ph] 4 Jun 2020.

- de Lange C. A. , J. D. Ferguson , W. Happer , and W. A. van Wijngaarden, Nitrous Oxide and Climate, arXiv:2211.15780v1 [physics.ao-ph] 28 Nov 2022.

- van Wijngaarden W. A. and W. Happer, The Role of Greenhouse Gases in Energy Transfer in the Earth’s Atmosphere, arXiv:2303.00808v1 [physics.ao-ph] 1 March 2023.

- Findell, Krsten L., Patrick W. Keys, Ruud J. van der Ent, Benjamin R. Lintner, Alexis Berg, and John P. Krasting, Rising Temperatures Increase Importance of Oceanic Evaporation as a Source for Continental Precipitation, (2019), American Meteorological Society. [CrossRef]

- Ashera, Elizabeth , Michael Todta, , Karen Rosenlof , Troy Thornberry, Ru- Shan Gao , Ghassan Tahac, , Paul Walter , Sergio Alvarez, James Flynn , Sean M. Davis, Stephanie Evan , Jerome Brioude , Jean- Marc Metzger , Dale F. Hurst, Emrys Hall, and Kensy Xiong, Edited by Mark Thiemens, Unexpectedly rapid aerosol formation in the Hunga Tonga plume, 2023, PNAS research article | Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xi, Jun Wang, Meng Zhou , Zhendong Lu, Lyatt Jaegle , Luke D. Oman & Ghassan Taha, Impact of water vapor on stratospheric temperature after the 2022 Hunga Tonga eruption: direct radiative cooling versus indirect warming by facilitating large particle formation, (2025), npj | climate and atmospheric science. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Ashok Kumar, Tushar Mittal, Kristen E. Fauria, Ralf Bennartz & Jasper F. Kok, The January 2022 Hunga eruption cooled the southern hemisphere in 2022 and 2023, (2025), communications earth & environment, A Nature Portfolio journal. [CrossRef]

- Galkin, V.D., Nikanorova, I.N. Solar activity and atmospheric water vapor. Geomagn. Aeron. 55, 1175–1179 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.,D.W. Fahey, A. Skowron, M.R. Allen, U. Burkhardt, Q. Chen, S.J. Doherty, S. Freeman, P.M. Forster, J. Fuglestvedt, A. Gettelman, R.R. De Le´on, L.L. Lim, M. T. Lund, R.J. Millar B. Owen, J.E. Penner, G. Pitari, M.J. Prather, R. Sausen, L. J. Wilcox, The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018, (2021), Atmospheric Environment. [CrossRef]

- S. Barrett, M. Prather, J. Penner, H. Selkirk, S. Balasubramanian, A. Dopelheuer, G. Fleming, M. Gupta, R. Halthore, J. Hileman, M. Jacobson, S. Kuhn, S. Lukachko, R. Miake-Lye, A. Petzold, C. Roof, M. Schaefer, U. Schumann, I. Waitz, R. Wayson, Guidance on the Use of AEDT Gridded Aircraft Emissions in Atmospheric Models, Massachusetts Institute for Technology, Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment (2010), https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=aae3bd04f264b1d0d584c5480e3b31d70fb92c39.

- Leron Wells, (2023) personal communication at Walker Water LLC.

- WMO Guidelines on Calculation of Climate Normals, 1017 edition, World Meteorological Organization, Chairperson, Publications Board, World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 7 bis, avenue de la Paix, P.O. Box 2300, CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland, Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03, Email: publications@wmo.int, ISBN 978-92-63-11203-3.

- Vavrus, Stephen J., Feng He, John E. Kutzbach, William F. Ruddiman & Polychronis C. Tzedakis, Glacial Inception in Marine Isotope Stage 19: An Orbital Analog for a Natural Holocene Climate, (2018), Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Willeit, Matteo, Reinhard Calov, Stefanie Talento, Ralf Greve, Jorjo Bernales, Volker Klemann, Meike Bagge, and Andrey Ganopolski, Glacial inception through rapid ice area increase driven by albedo and vegetation feedbacks, (2024), Climate of the Past, Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).