1. Introduction

Indonesia stands as one of the world’s foremost palm oil producers, with plantations widely distributed across Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua [

1]. Despite this abundance of natural resources, Papua remains among the least developed regions, particularly in terms of energy infrastructure and electricity access. In the southern Papuan regency of Boven Digoel, isolation is acute, and many areas lack a reliable power supply. For example, in Jair District, most residents rely solely on diesel generators to access electricity between 5 PM and 10 PM [

2]. High transportation costs and limited access to fuel exacerbate the already critical energy deficit in the region. While many studies on palm oil biomass-to-energy have focused on Sumatra and Kalimantan, limited research addresses Papua, which remains one of the least electrified and most energy-insecure regions in Indonesia. This research gap highlights the urgency of exploring locally available biomass resources for frontier-region electrification.

Conversely, the expansion of palm oil plantations, particularly under PT Korindo Group’s operations in Jair, has led to the generation of substantial palm oil mill waste, including empty fruit bunches (EFB), fibers, shells, and palm oil mill effluent (POME). Solid waste from crude palm oil (CPO) production can account for up to 40–50% of the total fresh fruit bunches (FFB) processed [

3]. These by-products carry considerable calorific value; palm shell waste reaches 3,719 kcal/kg, while fiber registers at 3,186 kcal/kg, making them ideal feedstock for biomass-based energy production [

4]. Globally, palm oil biomass has been widely discussed as a renewable energy feedstock; however, its application in remote island and frontier contexts is underexplored. Papua thus provides a unique case to examine the dual challenge of energy access and sustainable waste management within a marginalized region.

Utilizing palm oil waste as a renewable energy source in remote areas such as Boven Digoel presents a promising strategy for local resource mobilization and sustainable energy generation. Various waste streams, including POME, EFB, fiber, and shells, can be converted into biogas, bio-oil, and bio-briquettes, offering a renewable energy solution that aligns with Indonesia’s national energy goals [

1,

3]. Such an approach not only addresses local energy needs but also mitigates environmental pollution caused by unprocessed palm waste [

2].

POME can be anaerobically digested into biogas, as demonstrated by the Pasir Mandoge biogas power plant, which processes 1,584 m³ of POME to yield 47,520 m³ of biogas and generate 2 MW of power [

5]. Utilizing POME for biogas production significantly reduces environmental contamination, particularly in aquatic ecosystems, by preventing direct effluent discharge. Solid residues such as fiber and shell can be combusted to generate electricity. For instance, Perkebunan Nusantara VI uses six tons of solid waste per hour to produce 776 kWh, sufficient to meet the factory's energy demand. Dried EFB, with an enhanced calorific value of 4,353 kcal/kg [

6], becomes a suitable alternative fuel for biomass power plants. Pyrolysis of EFB and shells yields bio-oil and bio-briquettes, which can replace diesel fuel and meet national standards for energy content and moisture levels [

7]. Briquettes made from palm shells exhibit a calorific value exceeding 5,000 kcal/kg. Despite its promise, the deployment of palm waste for renewable energy still faces challenges, such as the need for upfront investment in appropriate technology and infrastructure, along with skilled labor. Furthermore, emissions resulting from biomass combustion must be carefully managed to ensure compliance with environmental standards [

5,

8].

In addition to supporting national policies such as Presidential Regulation No. 5/2006 and Presidential Instruction No. 1/2006, the adoption of a palm waste-to-energy system strengthens energy sovereignty and national security, particularly in border and remote areas [

9,

10]. This approach contributes to climate change mitigation by promoting the use of renewable energy and reducing dependence on fossil fuels [

11,

12]. This study explores the potential utilization of palm oil waste generated by PT Korindo Group in Jair District as a renewable energy source [

13,

14]. This study not only contributes to Indonesia’s renewable energy roadmap but also advances sustainability science by linking biomass utilization with energy justice, climate mitigation, and rural livelihood improvement. In doing so, it directly aligns with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 7 and SDG 13). By analyzing the types and volumes of available biomass, potential energy conversion pathways, and existing infrastructure readiness, this study aims to support the development of sustainable energy systems in remote areas and enhance Indonesia’s energy and territorial resilience [

15,

16].

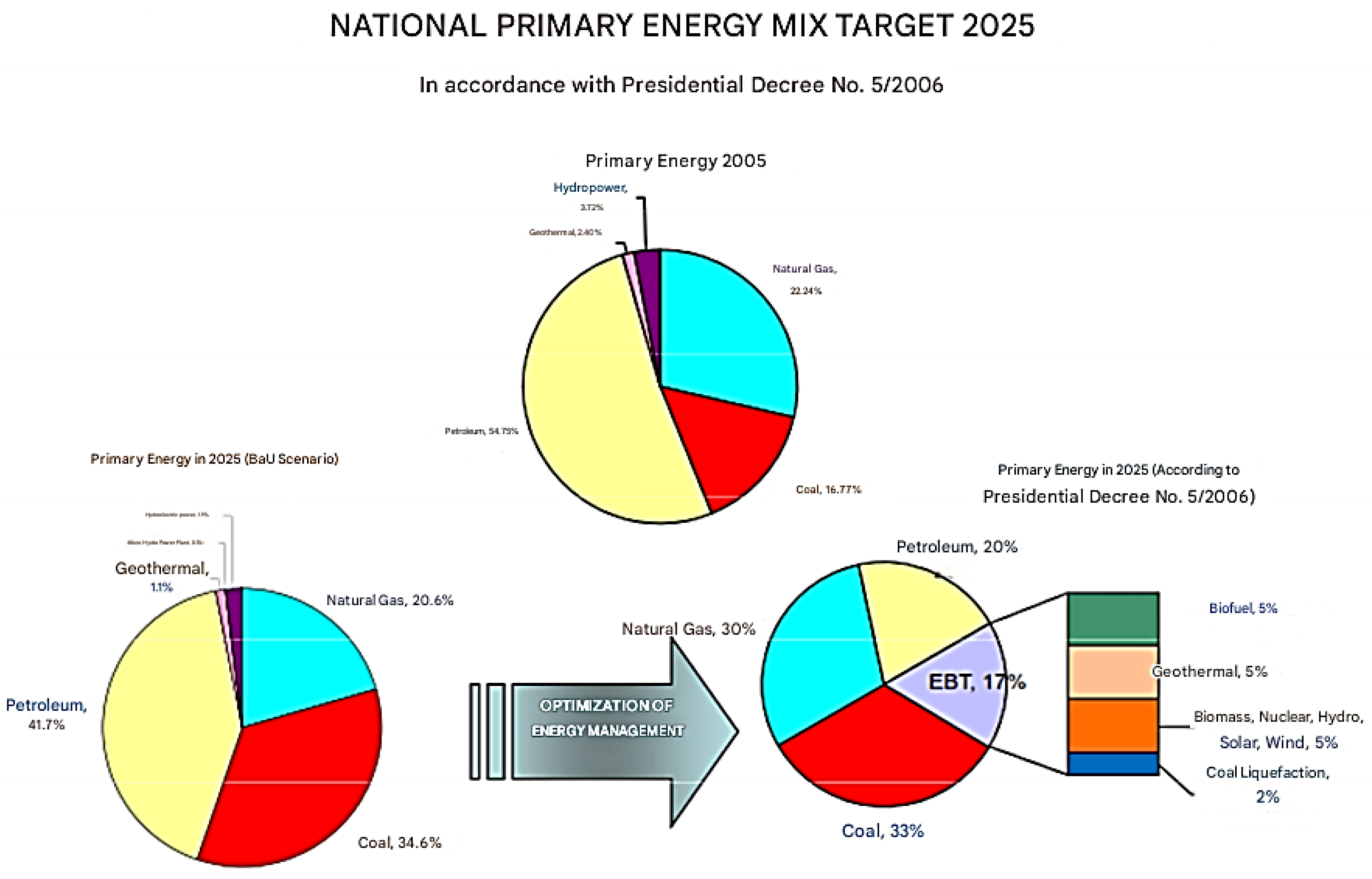

This focus on renewable biomass energy aligns with Indonesia’s national energy roadmap. Based on Presidential Regulation No. 5/2006, the country aims to reduce its dependency on petroleum from 54.7% in 2005 to 20% by 2025 and significantly increase the share of new and renewable energy (EBT) to 17%, as illustrated in

Figure 1 [

9,

17]. Within this target, bioenergy, including biomass, biogas, and biofuels, is projected to contribute up to 5% of the primary energy mix [

18,

19]. Conversely, under the business-as-usual (BaU) scenario, fossil fuels are expected to still dominate more than 96% of the supply by 2025 [

20]. These policy directions underscore the strategic importance of utilizing locally available biomass resources, especially in energy-poor and remote provinces such as Papua [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological approach used to estimate the theoretical energy potential of palm oil biomass waste from PT Korindo Group in Jair District, Boven Digoel, Papua. The research design combines quantitative estimation techniques with a case study framework, allowing an in-depth assessment of locally available resources in a frontier-region context. The integration of technical analysis with policy and sustainability framing ensures that the results remain both scientifically rigorous and practically relevant for renewable energy planning in remote areas.

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in Jair District, a remote frontier region in Boven Digoel Regency, Papua. The area suffers from chronic energy poverty, with limited infrastructure and heavy dependence on expensive diesel fuel. PT Korindo Group operates palm plantations and processing facilities spanning 10,865 hectares, making it a suitable case for exploring localized biomass-to-energy applications. This context provides a realistic platform to assess the feasibility of integrating palm waste into decentralized renewable energy systems. This case study approach was selected to capture both the technical feasibility and the socio-economic implications of biomass energy development in marginalized regions, which remain underrepresented in existing literature.

2.2. Methodology Overview

The study followed a systematic process consisting of five main stages:

-

Collection and Quantification of Biomass Waste

Primary data on waste generation were collected from PT Korindo’s processing operations, complemented by secondary parameters such as calorific values and methane yields sourced from peer-reviewed studies.

-

Classification of Waste Types

Waste streams were categorized into solid (EFB, fiber, shell, wet decanter solids) and liquid (POME) to align with appropriate conversion pathways.

Energy Potential Estimation

Where:

E = theoretical energy (kcal/year),

Q = waste mass (kg/year),

CV = calorific value (kcal/kg).

- 4.

-

Energy Unit Standardization

Results were expressed in kcal, GJ, and kWh for international comparability using standardized conversion factors.

- 5.

-

Comparative and Policy-Relevant Analysis

The estimated potential was compared against rural electrification demand benchmarks and national renewable energy targets to assess alignment with sustainability and policy objectives.

2.3. Biomass Waste Estimation

The volume of biomass waste was estimated using industry-standard mass-based conversion factors applied to the annual processed volume of fresh fruit bunches (FFB), totalling 1,569,160 tons/year.

Table 1 presents the proportion of each waste type generated from processing fresh fruit bunches (FFB). For every 100 tons of FFB, for example, 23 tons of EFB and 13.5 tons of fiber are produced. These conversion factors provide the foundation for estimating waste quantities and their corresponding energy potential.

Table 2 shows the annual estimated tonnage of each biomass waste stream based on the conversion ratios in

Table 1 and the total FFB processed by PT Korindo. Notably, POME is the largest contributor due to its high liquid content in the extraction process, followed by EFB and fiber.

2.4. Energy Potential Estimation

The theoretical energy potential was calculated using the formula (1) in

Section 2.2:

Table 3 provides the calorific content of each biomass waste stream. The calorific value determines how much energy can be derived from burning or processing the material. Dried EFB has the highest calorific value among solid wastes, making it the most energy-rich component for direct combustion. Biogas from POME is presented in kWh/m³ due to its gaseous form and electricity generation application.

2.5. Assumptions and Limitations

To streamline the analysis, the following assumptions were applied:

Annual FFB processing volume remains constant during the study period.

Losses due to moisture content, combustion inefficiencies, and emissions are excluded from calculations.

The study assesses theoretical energy potential only, without incorporating detailed life-cycle environmental impact assessments or cost-benefit analysis.

Primary data were limited to PT Korindo operations; however, they provide a representative benchmark for large-scale palm oil plantations in Papua.

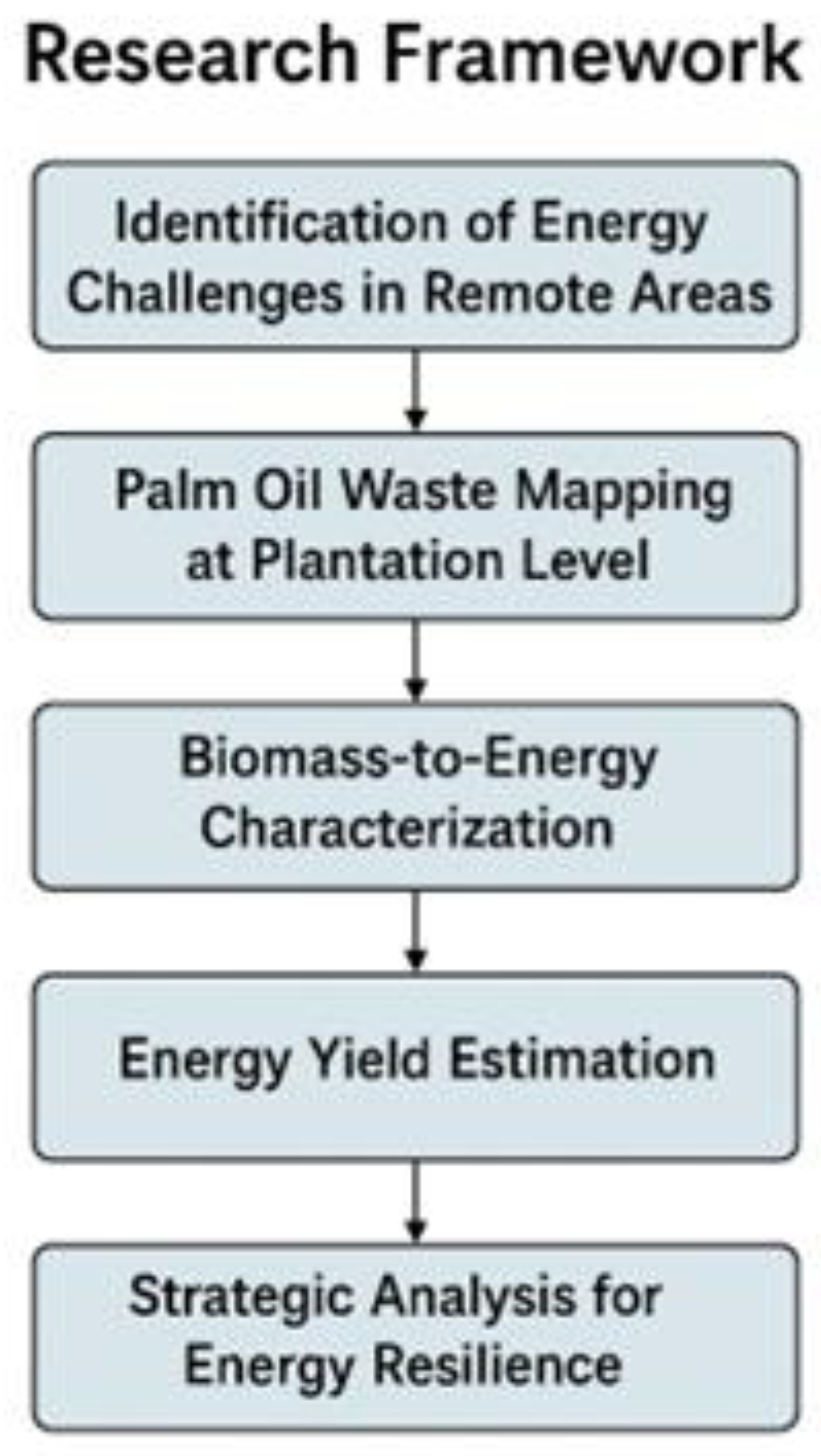

2.6. Research Framework

This study employs a multidisciplinary framework that integrates technical analysis with national energy and sustainability goals. The framework consists of five key stages:

Identification of Local Energy Challenges

Assessing energy poverty and diesel dependency in Jair District.

Palm Biomass Mapping

Quantifying waste generation based on plantation-level data.

Characterization of Conversion Pathways

Reviewing physical and chemical properties to identify feasible energy routes (biogas, briquettes, combustion).

Calculation of Energy Yields

Estimating theoretical outputs from each waste type.

Strategic Alignment

Interpreting findings in the context of national renewable energy policy and SDGs, with consideration of socio-economic co-benefits.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

3. Results

This section presents the estimated renewable energy potential from palm oil biomass waste generated by PT Korindo Group in Jair District, Boven Digoel, Papua. The results combine primary production data with calorific values and conversion benchmarks from literature to derive theoretical outputs. Beyond technical estimation, the results are interpreted in terms of rural electrification potential, alignment with national renewable energy targets, and contributions to sustainability objectives.

3.1. Energy Potential from Solid Biomass Waste

The energy potential of solid palm oil waste—including dried empty fruit bunches (EFB), fiber, and shell—was estimated based on annual waste volume and respective calorific values. The results are summarized in the table below:

Table 4 illustrates that dried EFB accounts for the highest energy yield, contributing over 1.57 trillion kcal/year due to both its high volume and calorific content. Fiber and shell also provide substantial energy potential, making them viable candidates for combustion-based or briquette-based energy systems. Collectively, solid biomass from PT Korindo’s operations could generate over 10.7 million GJ/year, equivalent to more than 2.56 trillion kcal/year. This translates into nearly 2.98 billion kWh/year, providing the dominant source of renewable energy potential in the study area. From a sustainability perspective, the conversion of solid biomass into energy could replace large portions of diesel consumption, reduce open burning, and support rural households through decentralized energy systems.

3.2. Biogas Potential from Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME)

In addition to solid biomass, POME presents a significant source for biogas generation through anaerobic digestion. The estimation of its energy potential follows conservative assumptions derived from operational benchmarks such as the Pasir Mandoge biogas plant, with key assumptions:

Methane yield: 28 m³ CH₄ per ton of POME

Methane calorific value: 9.97 kWh/m³

Electricity conversion efficiency: 35%

Table 5 shows that POME alone can yield approximately 42.9 GWh/year of electricity, sufficient to meet the basic energy needs of thousands of rural households. The relatively lower yield compared to solid biomass is due to conversion losses inherent in biogas-to-electricity systems; however, although it smaller in magnitude than solid biomass, POME plays a critical role in improving wastewater management, mitigating methane emissions, and providing decentralized electricity for off-grid villages. This dual role strengthens its relevance not only as an energy source but also as an environmental safeguard in remote plantation operations.

3.3. Total Theoretical Renewable Energy Potential

By combining energy derived from solid biomass and POME biogas, the total theoretical renewable energy potential from PT Korindo’s operations is presented below.

The combined renewable energy potential exceeds 3.02 billion kWh/year, illustrating the immense opportunity for fossil fuel substitution and decentralized energy generation in Papua. Notably, over 98% of the potential originates from solid biomass, reaffirming the strategic importance of combustion and thermal processing technologies. This energy potential is sufficient to meet the basic annual electricity needs of over 3.3 million households (assuming 900 kWh per household per year). Such results demonstrate the transformative potential of palm oil biomass to enhance rural energy equity, particularly in frontier regions such as Papua where conventional grid expansion is economically unfeasible.

Table 6.

Combined Renewable Energy Potential from All Biomass Waste.

Table 6.

Combined Renewable Energy Potential from All Biomass Waste.

| Waste Stream |

Estimated Energy (kWh/year) |

| Shell |

372,140,000 |

| Fiber |

781,460,000 |

| Dried EFB |

1,827,370,000 |

| POME (biogas) |

42,923,220 |

| Total |

3,023,893,220 |

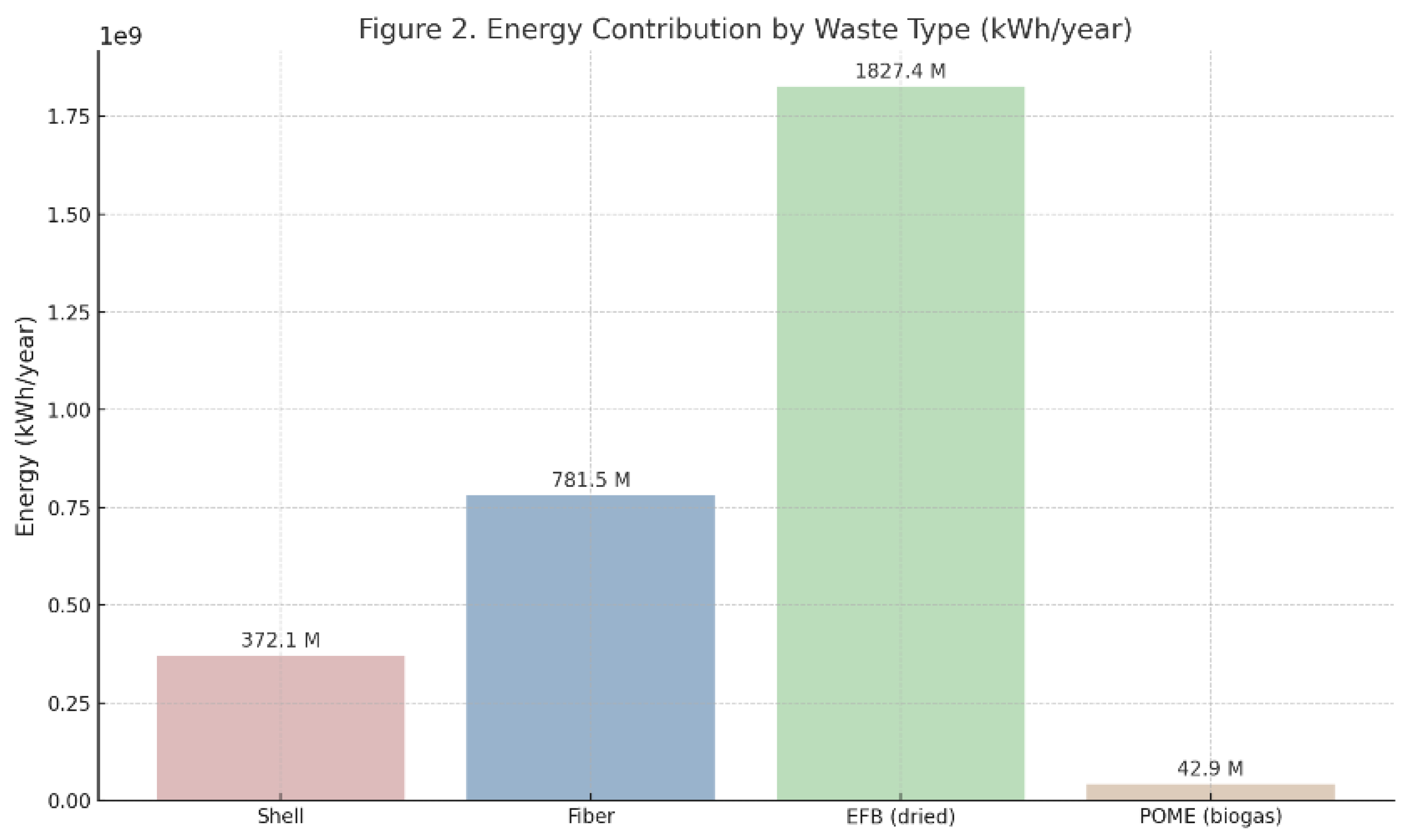

3.4. Visual Comparison by Waste Type

To facilitate interpretation of relative contributions, a visual representation of energy yield by waste type is provided in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 visually emphasizes the dominant role of dried EFB, which contributes more than 1.8 billion kWh/year, followed by fiber (781 million kWh/year) and shell (372 million kWh/year). Although POME’s net energy contribution is relatively modest (42.9 million kWh/year), its value lies in the diversification of energy sources and potential for grid-independent electricity generation.

Figure 2 also illustrates the proportional contributions of each waste type, with EFB clearly dominating the energy yield. Fiber and shell serve as important secondary contributors, while POME provides a valuable supplement for decentralized electricity. The visual comparison highlights the centrality of solid biomass in energy recovery strategies while underscoring the complementary environmental role of POME.

3.5. Policy-Relevant Interpretation

The magnitude of potential energy derived from palm oil biomass waste demonstrates clear alignment with Indonesia’s National Energy Policy (KEN) and General National Energy Plan (RUEN), which target 23% renewable energy by 2025. Moreover, the ability to convert waste into energy in a frontier province directly advances SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The results confirm that resource mobilization at the local level can serve as a strategic complement to national energy transition goals, while simultaneously reducing emissions and improving environmental quality.

4. Discussion

The empirical findings of this study highlight the considerable potential of palm oil biomass waste, namely dried empty fruit bunches (EFB), fiber, shell, and Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) as renewable energy resources in remote, energy-deficient regions such as Jair District, Boven Digoel, Papua. The total theoretical energy available from PT Korindo Group's biomass waste exceeds 3.02 billion kWh/year, sufficient to power more than 3.3 million rural households.

4.1. Addressing Energy Insecurity in Remote Border Areas

The chronic under-electrification in Papua’s frontier districts stems from geographic isolation, inadequate infrastructure, and overreliance on costly diesel fuel. Leveraging locally available biomass waste offers a decentralized and cost-effective energy alternative. In regions such as Jair District, where conventional grid expansion is economically prohibitive, biomass conversion can fulfill basic household electricity demand while promoting energy self-sufficiency.

This study estimates that the energy generated from biomass waste could meet the annual electricity needs of more than 3.3 million households, assuming an average consumption of 900 kWh/year. Sodri and Septriana (2022) demonstrated that biogas generation from POME is both economically viable and environmentally beneficial in rural settings [

22]. Thus, palm biomass offers a transformative opportunity to reshape local energy systems.

4.2. Environmental and Economic Co-benefits

Beyond improving energy access, biomass utilization yields multiple environmental and economic benefits. By diverting EFB and POME from open disposal or unmanaged decomposition:

Methane emissions from untreated POME can be significantly reduced.

Air quality is improved through the reduction of open burning practices.

Land use efficiency is increased by converting residues into energy rather than letting them accumulate as waste.

In thermophilic conditions, anaerobic digestion of POME has been shown to yield higher methane output than mesophilic systems, offering increased energy efficiency [

23,

26]. Irvan et al. (2025) found that methane generation from thermophilic anaerobic reactors could reach over 6–16 L/day per reactor, with substantial reductions in COD and volatile solids [

24].

Economically, local processing of biomass fuels reduces diesel transport costs and supports rural employment in collection, drying, briquetting, and system maintenance. This aligns with sustainable development principles and supports compliance with sustainability certifications (ISPO, RSPO), further enhancing market competitiveness.

4.3. Briquetting of EFB as a Clean Fuel Innovation

A key innovation highlighted in this study is the potential of dried EFB to be processed into environmentally friendly briquettes. This form of solid biofuel presents a viable, clean-burning alternative to raw biomass or kerosene in rural households.

Laboratory tests demonstrate that:

EFB briquettes can reach calorific values exceeding 5,000 kcal/kg.

Emissions such as smoke, carbon monoxide, and particulates remain within safe limits for indoor combustion.

Ash production is minimal, reducing the operational burden on end users.

Recent studies also highlight that pretreating EFB via delignification before co-digestion with POME can enhance biogas yield by improving biodegradability [

25]. These attributes position EFB briquettes as a low-emission, sustainable energy source suitable for domestic cooking and heating applications. Furthermore, they offer an alternative to firewood, helping to mitigate deforestation and household air pollution in rural settings. The briquetting of EFB not only adds economic value to plantation waste but also supports clean cooking transitions, a target under Indonesia’s SDG 7 roadmap. In practice, community-scale briquetting units could be deployed near palm oil mills, facilitating local value addition and promoting energy independence.

4.4. Technological and Infrastructure Challenges

Despite the promising potential, several technological and infrastructural constraints must be addressed:

Drying and densification equipment for EFB briquettes requires capital investment and maintenance capacity.

Biogas systems for POME must be appropriately sized and managed to ensure biological stability and consistent output.

Energy storage and distribution systems are needed to match variable demand in off-grid communities.

Materials such as activated carbon or conductive particles are being tested to enhance sludge stabilization and methane production in anaerobic systems [

26]. Projects like the Pasir Mandoge Biogas Plant illustrate effective utilisation of POME-based electricity systems, serving as a model for potential adoption in Papua when adequate technical and institutional frameworks are established. Addressing existing challenges requires comprehensive approaches, including technological advancements, robust institutional backing, targeted training, and financing solutions that accommodate the specific needs of remote regions.

4.5. Policy and Governance Alignment

The use of palm oil biomass as a renewable energy source aligns with multiple national policies and development priorities:

The National Energy Policy (KEN) and RUEN emphasize increased biomass utilization to reach renewable energy targets of 23% by 2025 and 31% by 2050.

Presidential Regulation No. 112/2022 prioritizes renewable energy development in remote and frontier areas through decentralized approaches.

This policy framework supports the use of residual biomass as a local energy source, especially when integrated into rural electrification strategies targeting off-grid regions like Boven Digoel. However, implementation remains constrained by limited institutional coordination, inadequate local capacity, and fragmented funding mechanisms.

4.6. Climate Mitigation and SDG Contributions

By substituting diesel fuel and reducing methane emissions from POME, palm biomass utilization contributes to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Moreover, the community-level benefits in terms of job creation, local empowerment, and rural value addition support SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). The findings thus confirm that biomass energy in Papua offers a multi-dimensional sustainability pathway, linking environmental stewardship with socio-economic inclusion.

4.7. Critical Reflections and Future Research Directions

This study focused on theoretical energy potential and preliminary economic feasibility, based on a single company’s operations (PT Korindo). While representative, broader regional studies and pilot-scale implementations are needed to validate these findings. Life cycle assessment (LCA) should be conducted to quantify net greenhouse gas reductions. Future research should also examine social acceptance, governance models, and financing frameworks to ensure scalability. Integrating community perspectives will be crucial to design energy solutions that are both technically viable and socially sustainable.

4.8. Preliminary Economic Assessment of Biomass Utilization

To address the electricity shortage in Boven Digoel, the local government and ESDM propose a 2 MW biomass power plant utilizing palm oil waste from PT Korindo Group in Jair District. This section analyzes its economic feasibility through technical output estimation, operational cost, revenue forecast, and financial viability indicators.

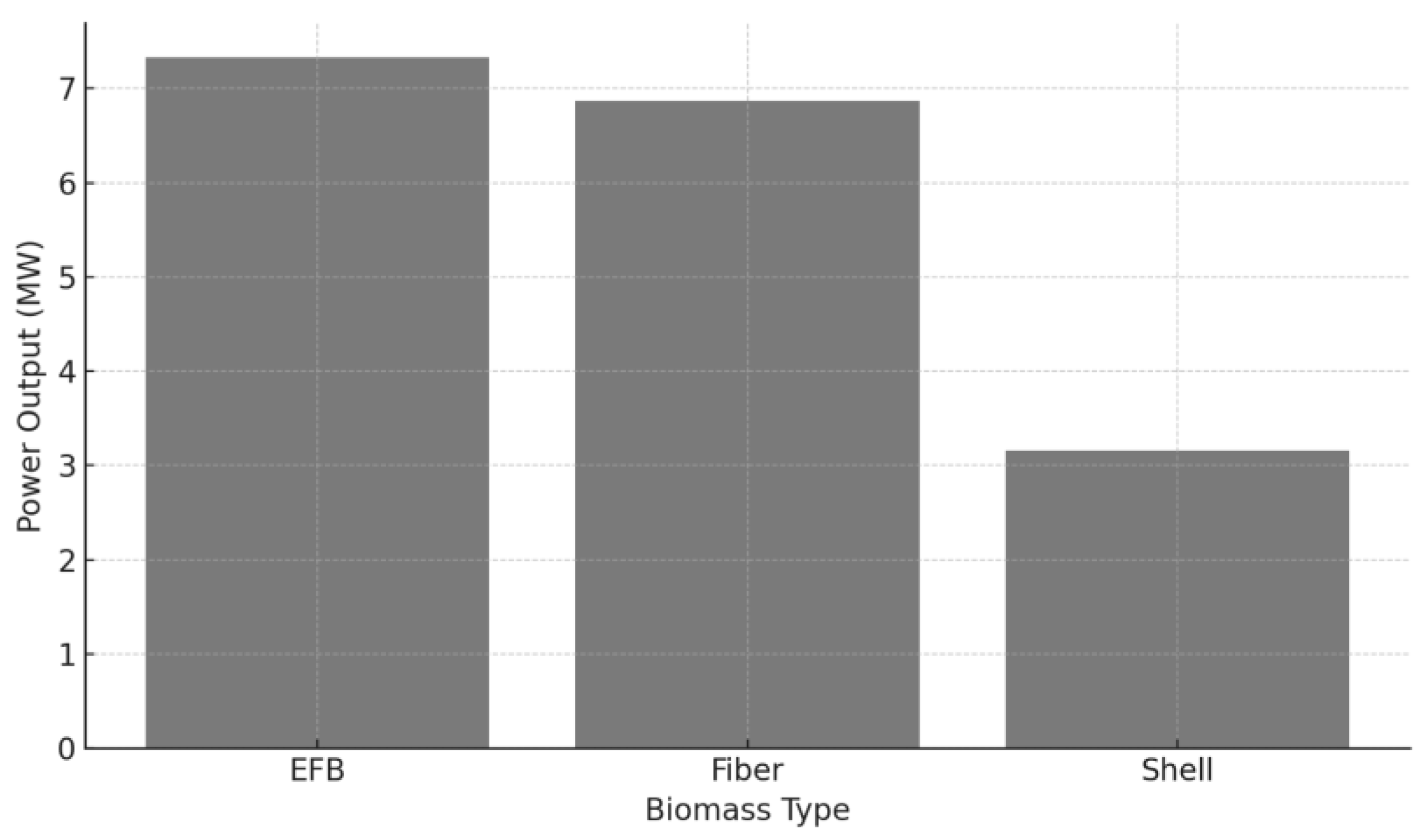

4.8.1. Estimated Power Output from Biomass Waste

The amount of energy generated depends on the calorific value and volume of dry biomass available. The following table shows the estimated hourly fuel availability, steam production, and corresponding electricity output.

Table 7.

Estimated Steam and Electricity Output from Biomass Types.

Table 7.

Estimated Steam and Electricity Output from Biomass Types.

| Waste Type |

HHV (kJ/kg) |

Fuel Available (kg/hr) |

Steam Generated (kg/hr) |

Estimated Power Output (MW) |

| EFB |

18,719.46 |

7,310 |

42,524.72 |

7.33 |

| Fiber |

20,315.45 |

6,310 |

39,835.86 |

6.87 |

| Shell |

23,569.26 |

2,500 |

18,301.61 |

3.16 |

These values show that palm oil waste has considerable power generation potential, with EFB producing the highest steam volume due to greater fuel mass.

Figure 3.

Power Output Comparison by Biomass Type.

Figure 3.

Power Output Comparison by Biomass Type.

4.8.2. Operational Cost Estimation

The total operational cost includes fuel, supporting materials, and labor. The following table summarizes daily and annual costs.

Table 8.

Summary of Daily and Annual Operating Costs.

Table 8.

Summary of Daily and Annual Operating Costs.

| Item |

Daily Cost (IDR) |

Notes |

| Biomass Fuel (50,126 kg × Rp100) |

5,012,600 |

Main fuel source |

| Diesel Fuel (200 L × Rp4,500) |

900,000 |

For start-up |

| Lubricants & Maintenance (5%) |

506,273 |

Combined estimation |

| Total Daily Cost |

6,418,873 |

|

| Annual Cost (365 days) |

2,341,058,900 |

Excludes labor |

| Labor Cost (Annual) |

1,344,000,000 |

|

| Total Operational Cost/Year |

3,686,888,499 |

|

Operational costs are primarily driven by fuel and labor. Efficient use of biomass can minimize diesel usage and reduce total expenditure.

4.8.3. Revenue Estimation

The revenue is calculated from energy sales and fixed customer charges. The following table outlines the income structure.

Table 9.

Annual Revenue and Profit Projection.

Table 9.

Annual Revenue and Profit Projection.

| Component |

Value (IDR) |

| Energy Sales (4.8 MWh @ Rp1,312) |

Rp6,297,600,000 |

| Fixed Charges (2,000 HH @ Rp40,000 x 12 mo) |

Rp960,000,000 |

| Total Revenue/Year |

Rp7,257,600,000 |

| Operational Cost |

Rp3,686,888,499 |

| Net Annual Profit |

Rp3,570,711,501 |

The project demonstrates strong profitability, with production cost at Rp768/kWh, well below the selling price of Rp1,312/kWh.

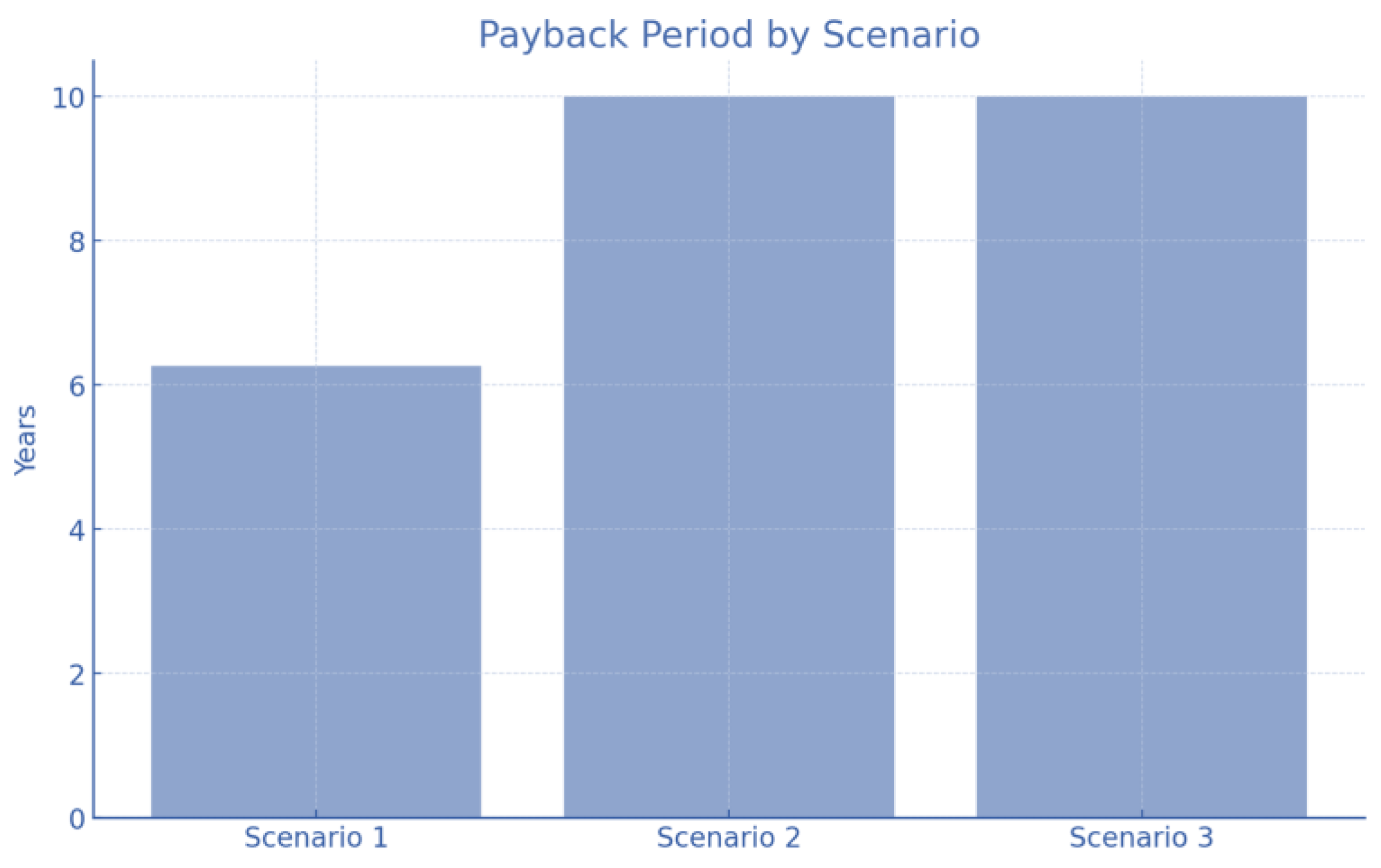

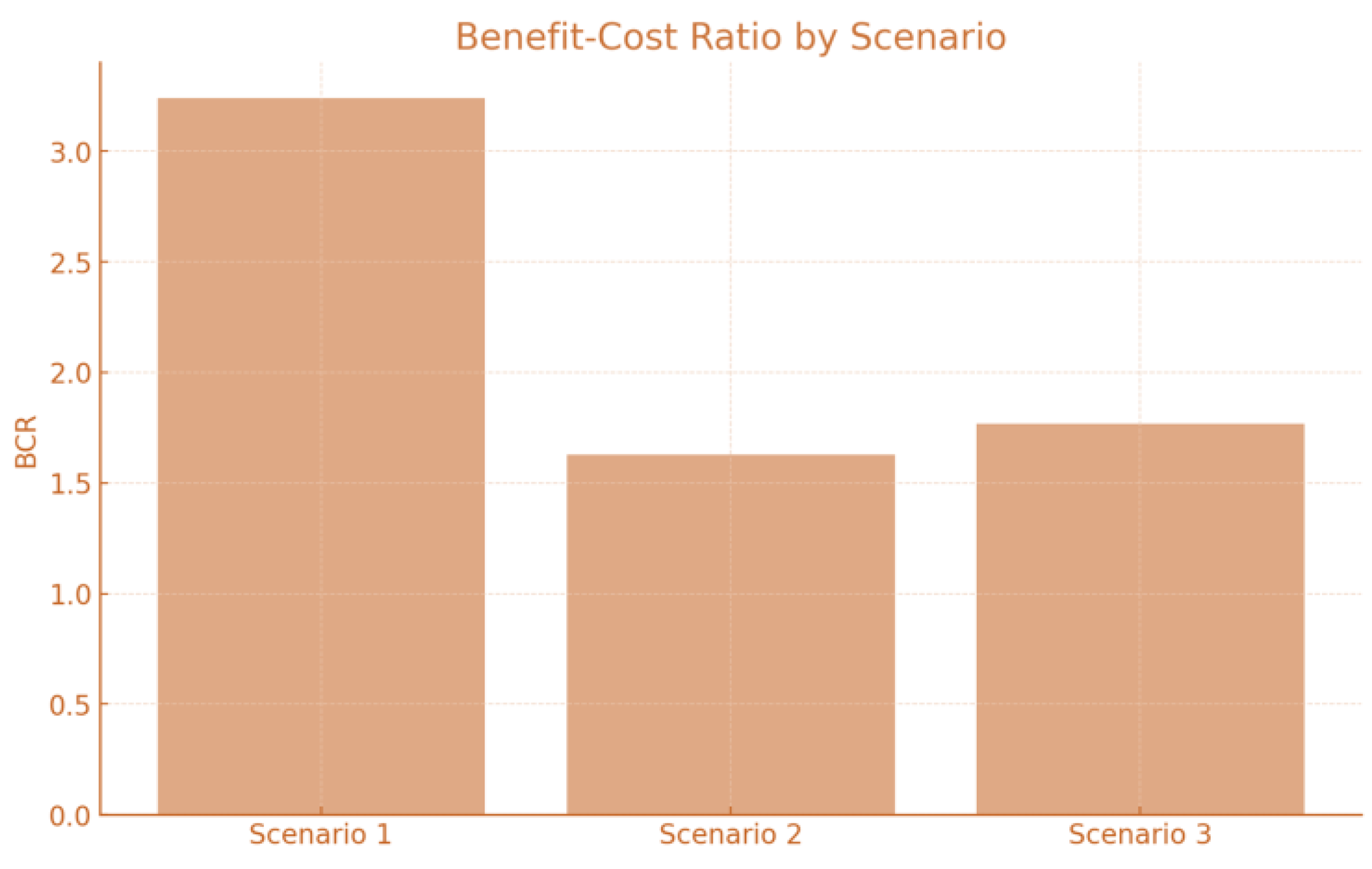

4.8.4. Investment Scenario Explanation

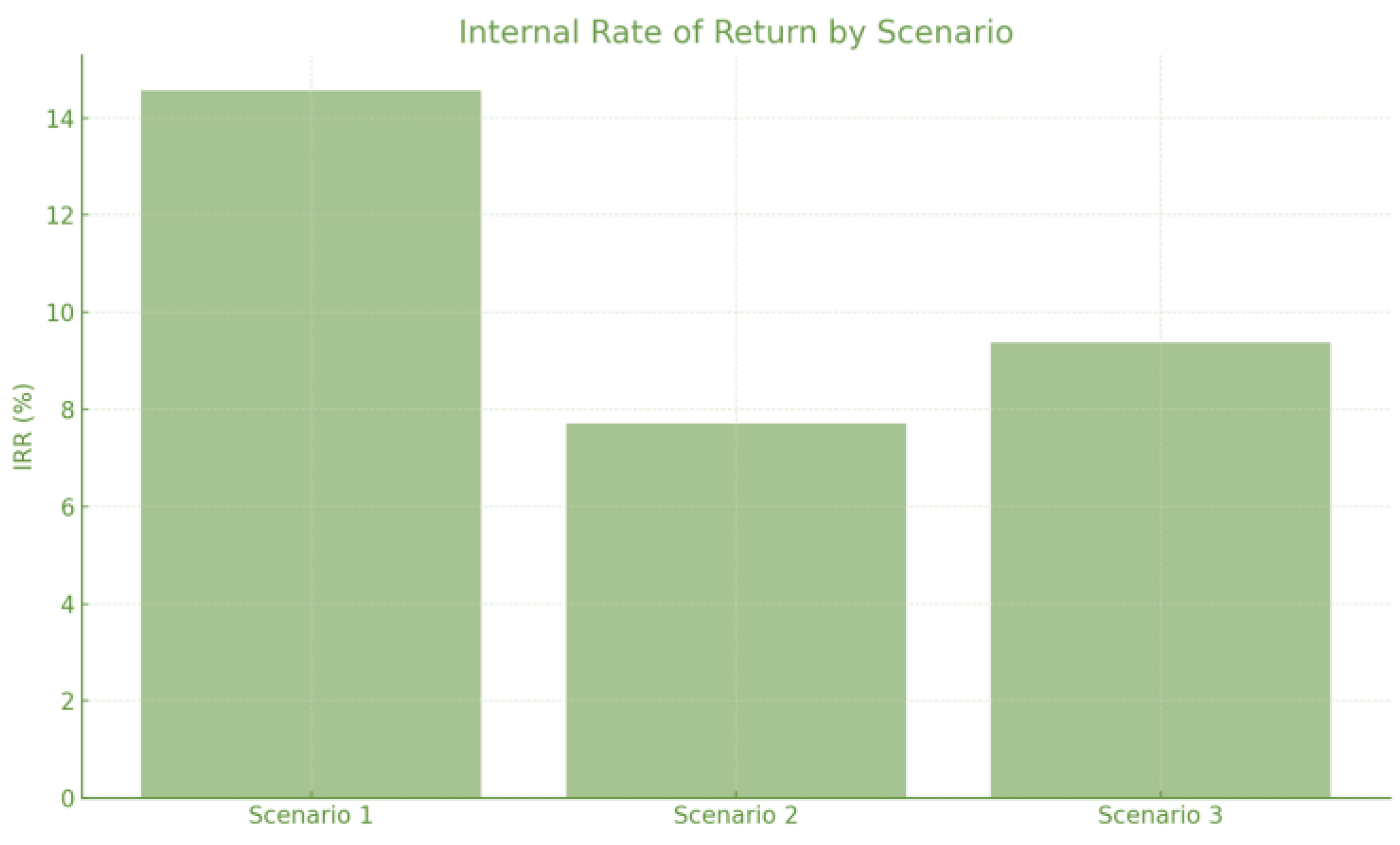

To evaluate investment attractiveness, three financing schemes are compared:

Scenario 1 – 100% Equity: Fully financed by private or institutional equity, leading to maximum profit retention and faster return.

Scenario 2 – 70% Bank Loan: Reduces upfront capital requirement but includes annual loan repayments.

Scenario 3 – 30% Bank Loan: A balanced model combining reduced debt exposure with moderate leverage.

4.8.5. Financial Performance Comparison

The table below compares key financial metrics under the three investment scenarios.

Table 4.

4. Financial Indicators for Three Investment Scenarios.

Table 4.

4. Financial Indicators for Three Investment Scenarios.

| Indicator |

Scenario 1 (100% Equity) |

Scenario 2 (70% Loan) |

Scenario 3 (30% Loan) |

| Payback Period (Years) |

6.26 |

10 |

10 |

| Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) |

3.24 |

1.63 |

1.77 |

| Internal Rate of Return |

14.57% |

7.71% |

9.37% |

Scenario 1 shows the most favorable results, with IRR significantly higher than MARR (8%) and a BCR of 3.24.

Figure 4.

2. Payback Period Comparison by Scenario.

Figure 4.

2. Payback Period Comparison by Scenario.

Figure 4.

3. Benefit-Cost Ratio by Scenario.

Figure 4.

3. Benefit-Cost Ratio by Scenario.

Figure 4.

4. Internal Rate of Return by Scenario.

Figure 4.

4. Internal Rate of Return by Scenario.

4.8.6. Interpretation and Conclusion

The financial metrics confirm that the proposed biomass power plant is economically viable under all three financing scenarios. Scenario 1 offers the most favorable outcomes, combining profitability with reduced investment risk. Importantly, beyond profitability, the project provides wider sustainability benefits:

Supporting energy equity in Papua by expanding electricity access to underserved households.

Reducing dependence on imported diesel and stabilizing rural energy costs.

Creating employment in biomass collection, processing, and plant operations.

Aligning with Indonesia’s renewable energy transition goals under RUEN and contributing directly to SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

This preliminary economic assessment demonstrates that biomass-to-energy systems can be financially self-sustaining while delivering environmental and social co-benefits. Scaling up such models in frontier regions could strengthen Indonesia’s energy sovereignty and accelerate the achievement of national and global sustainability targets.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that palm oil biomass waste, particularly empty fruit bunches (EFB), mesocarp fiber, shells, and palm oil mill effluent (POME) represents a significant renewable energy source for remote and under-electrified regions such as Papua. With a combined theoretical potential exceeding 3.02 billion kWh/year, these residues can substitute diesel-based electricity and provide sufficient supply for more than 3.3 million households.

From a technical perspective, dried EFB emerges as the largest contributor, while POME offers complementary value through decentralized biogas generation and improved wastewater management. Importantly, the preliminary economic assessment of a 2 MW biomass power plant indicates strong financial viability, with a production cost of Rp768/kWh, well below the selling price of Rp1,312/kWh, a payback period of 6.3 years, and an internal rate of return (IRR) of 14.6%, significantly higher than the minimum attractive rate of return. These results confirm that biomass-to-energy systems in Papua are not only technically feasible but also financially sustainable.

The novelty of this research lies in presenting one of the first techno-economic and policy-oriented case studies of palm biomass energy in Papua, bridging the gap between national energy transition targets (KEN, RUEN) and local realities of rural energy poverty. By linking technical, financial, and policy dimensions, the study provides actionable insights for developing decentralized energy systems in frontier regions.

Future initiatives should extend toward pilot-scale implementation, life cycle assessments (LCA), and the design of community-based financing and governance models to ensure scalability, social acceptance, and long-term sustainability. If properly integrated, palm biomass can serve as both a clean energy solution and a catalyst for inclusive rural development, advancing multiple Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), SDG 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, R.J.; data curation, I.N.; writing-original draft preparation, I.N.; writing - review and editing, I.N.; visualization, I.N.; supervision, R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who provided valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrianto, A. (2011). Environmental and Social Impacts from Palm based Biofuel Development in Indonesia. https://iasc2011.fes.org.in/papers/docs/323/submission/original/323.pdf.

- H. Firdaus, L. W. Hardono and V. Endramanto, "Future Green Energy Circular Economy for Reaching Energy Transition in Indonesia: Case Study Biomass & Biogas Power Plant Using Palm Oil Plant in PT PLN Riau & Riau Islands," 2024 International Conference on Technology and Policy in Energy and Electric Power (ICTPEP), Bali, Indonesia, 2024, pp. 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Hambali, E., & Rivai, M. (2017). The potential of palm oil waste biomass in Indonesia in 2020 and 2030. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 65(1), 012050. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J. E. (2015). Electricity generation from palm oil biomass residues incineration : feasibility study with feedstock from governmental plantation sites in Sumatra Utara, Indonesia [Master Thesis, Technische Universität Wien]. reposiTUm. [CrossRef]

- Parmansyah, W., Rimbawati, R., Pratama, C., & Evalina, N. (2024). Analysis of The Utilization of Palm Oil Liquid Waste (POME) as A Biogas Power Plant at Palm Oil Mill Bandar Pasir Mandoge. Proceeding of International Conference on Science and Technology UISU., 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R., Djufri, U., & Wijaya, H. (2022). Pemanfaatan Biomassa Padat Kelapa Sawit Sebagai Energi Baru Terbarukan DI PLTU Pabrik Kelapa Sawit PT. Perkebunan Nusantara VI Unit Usaha Bunut. Journal of Electrical Power Control and Automation, 5(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Yanti, R. N. (2023). Pemanfaatan Limbah Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Sebagai Sumber Energi Terbarukan. Dinamika Lingkungan Indonesia, 10(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Prabasari, I. G., & Pusparani, N. K. A. M. (2022). Model Persebaran Emisi pada Pembangkit Listrik Tenaga Uap Berbahan Bakar Serat dan Cangkang Kelapa Sawit Menggunakan Perangkat Pemodelan Aermod. Jurnal Daur Lingkungan, 5(2), 75. [CrossRef]

- Republic of Indonesia. (2006). Presidential Regulation No. 5 of 2006 on National Energy Policy. Jakarta: State Secretariat. https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/42118/perpres-no-5-tahun-2006.

- Wibawa, A. (2018). Challenges and policy for biomass energy in Indonesia. International Journal of Biomass and Energy, 15(2), 212–225. https://ijbel.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IJBEL15_212.pdf.

- Yana, S., Nizar, M., & Mulyati, D. (2022). Biomass waste as a renewable energy in developing bio-based economies in Indonesia: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 163, 112445. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., & Setiawan, A. D. (2013). Biomass energy policies and strategies: Harvesting potential in India and Indonesia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 23, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace International. (2020). Investigation indicates FSC-certified company intentionally used fire to clear Indonesian forests for palm oil. Amsterdam: Greenpeace International. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/45621/investigation-indicates-fsc-certified-company-intentionally-used-fire-to-clear-indonesian-forests-for-palm-oil/.

- Environmental Investigation Agency. (2020). The Korindo Group's industrial operations in Papua: Environmental and social impacts. London: EIA. https://korindonews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/EN-One-Step-Ahead-06-FA-lowres.pdf.

- Saputra, A. (2022). Mini review of Indonesia's potential bioenergy and regulations. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 997(1), 012004. [CrossRef]

- Kharina, A., Malins, C., & Searle, S. (2016). Biofuels policy in Indonesia: Overview and status report. Washington, DC: International Council on Clean Transportation. https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Indonesia%20Biofuels%20Policy_ICCT_08082016.pdf.

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. (2019). Indonesia Energy Outlook 2019. Jakarta: Center for Data and Information Technology. https://www.esdm.go.id/assets/media/content/content-indonesia-energy-outlook-2019-english-version.pdf.

- Arinaldo, D., Adiatma, J. C., & Simamora, P. (2018). Indonesia’s energy transition outlook: Tracking progress of renewable energy development in Indonesia. Jakarta: Institute for Essential Services Reform.

- IRENA. (2022). Renewable Energy Statistics 2022. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency. https://www.spr.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IRENA_RE_Capacity_Statistics_2022.pdf.

- Handayani, K., Krozer, Y., & Filatova, T. (2017). Trade-offs between electrification and climate change mitigation: An analysis of the Indonesian energy system. Applied Energy, 208, 1020–1037. [CrossRef]

- Dermawan, A., Petkova, E., Sinaga, A. C., Muhajir, M., & Indriatmoko, Y. (2011). Preventing the risks of corruption in REDD+ in Indonesia. Jakarta: Center for International Forestry Research. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/archive/documents/indonesia/forest-crime/2011/Summary_Report_REDD_and_Corruption.pdf.

- Anwar, D., Simanjuntak, E. E., Sitepu, I., Kinda, M. M., Nainggolan, E. A., & Wibowo, Y. G. (2024). Thermophilic digestion of palm oil mill effluent: Enhancing biogas production and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Jurnal Presipitasi: Media Komunikasi dan Pengembangan Teknik Lingkungan, 21(3), 734–746. [CrossRef]

- Sodri, A., & Septriana, F. E. (2022). Biogas power generation from palm oil mill effluent (POME): Techno-economic and environmental impact evaluation. Energies, 15(19), 7265. [CrossRef]

- Irvan, I., & Trisakti, B. (2025). Methane emission from digestion of palm oil mill effluent (POME) in a thermophilic anaerobic reactor. International Journal of Science and Engineering, 3(1), 32–35. [CrossRef]

- Firstonda Katon, M. A., & Saputro, F. R. (2024). Delignification methods for empty fruit bunch co-substrate in POME anaerobic digestion. Journal of Oil Palm Research. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Kartika, R. W. A., Desman, N. S., & Prijambada, I. D. (2022). Peruraian anaerobik termofilik palm oil mill effluent dengan variasi konsentrasi substrat. Jurnal Rekayasa Proses, 16(1), 25-29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).