Introduction

Although sleep has often been considered a benevolent time of restoration and well-being, it may significantly impact biologic functions [

1]. In particular, quality of sleep has been associated with cardiac events [

2] and irregular sleep has been associated with subclinical atherosclerosis [

3]. Emotional stress represents a trigger for acute coronary syndromes [

4], possibly inducing coronary artery spasm [

5], activation of the coagulative system with stress-induced thrombogenesis [

6], as well as activation of the neuroendocrine system [

7]. Sleep complaints have been associated with risk of incident acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and many individuals who have suffered from AMI report sleep disturbances prior to their acute cardiac event [

8,

9,

10].

Dreams occurring both during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM (NREM) sleep may cause sudden variations in sympathetic/parasympathetic balance activity, despite hemodynamic and respiratory stability [

1], and may be a source of intense distress. Changes in autonomic activity during dreaming can have negative effects in patients with cardiovascular disease, as shown in several case reports of patients with no underlying cardiac disease, where emotional stress produced by nightmares or ‘deadly dreams’ led to AMI by spontaneous coronary artery dissection or vasospasm [

11]. However, there are no studies on the organization and structure of dreams before and after myocardial infarction that might convey insight into acute coronary syndromes, pathophysiology and mechanisms, as well as on mind-body relationships.

Therefore, we endeavored to retrospectively study dream patterns before and after AMI in the STEP-IN AMI (Short TErm Psychotherapy IN Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial [

12,

13,

14,

15]. We also describe how this pattern may change during psychotherapy.

Materials and Methods

The STEP IN AMI trial, approved by the hospital San Filippo Neri ethics committee in 2004 (clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrial.gov: NCT00769366), was a randomized study planned to evaluate the efficacy of a Short Term ontopsychological Psychotherapy (STP) in patients (pts) with AMI, treated with a percutaneous trans-catheter coronary angioplasty (PTCA).

101 patients (pts), ≤70 years old, admitted to San Filippo Neri hospital in Rome for AMI, were randomized to receive or not to receive STP in addition to standard contemporary treatment for AMI. AMI was treated in the acute phase with primary or urgent PTCA of the culprit lesion, within 12 h of the onset of an ST elevation-associated AMI (STEMI, primary PTCA), or within 48 h in pts with a non-STEMI (urgent PTCA). Detailed description of the protocol, methodology and one and five-year results have been previously published [

13,

14,

15].

Only pts randomized to STP are included in the present study.

Administration of psycho-active drugs was not part of the protocol; but, in pts already being treated, psychiatric drugs were not discontinued after enrollment. In particular, only one patient had been in psychiatric follow-up since his twenties.

Psychotherapy was performed by a single skilled and licensed psychotherapist (AR), with the help of clinical staff, psychologists and nurses. An STP, derived from the ontopsychological method and specifically adapted by the psychotherapist herself to the context of the research in the field of cardiac psychology, was utilized.

Ontopsychological method is a complex and original synthesis derived from psychoanalysis, analytical psychology and humanistic–existential psychology, as elaborated by Abraham Maslow [

16]. With this approach, the human being is considered a complex system consisting of a unity of psyche and body, where anything happening in the body may influence the psyche and vice versa, as demonstrated by several studies in the field of psycho-neuro-endocrine-immunology [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

We report here a very concise synthesis of the STP performed in this group of pts, extracted from other publications [

12,

14].

“Psychotherapy was delivered initially in individual and then group sessions over a 6-month period after the incident AMI. Individual meetings focused on personal history, as emotionally lived by the patient, and on understanding basic expressions of the unconscious dimension, through the interpretation of body and oneiric language. The number of individual meetings was tailored to the specific needs and problems of each patient, ranging from 3 to 11 meetings over a 3-month period……. Over the duration of this brief course of treatment, the psychotherapist helps the patient to gain insights and elaborate on conflicts that need to be resolved, as well as on dysfunctional behaviors and interpersonal relationships. After the initial interviews, ….the psychotherapist helps the patient to gain insights into his/her body sensations….The psychotherapist guides the patient to acquire full contact with his/her body, starting from the visceral zone, with the help of abdominal breathing and relaxation techniques. In the final phase of the individual meetings and whenever possible, the psychotherapist guides the patient into deeper insights through dream analysis. ……As the psychotherapist helps the patients to contact the central positive nucleus of their unconscious (the “In Se”), their nightmares cease and/or the patients resume remembering dreams related to their real-life problems. This reflects inner changes orchestrated by the patient.

The psychotherapeutic work done during the individual sessions is reiterated during group sessions.... The aim of all these processes was to stabilize the pathology and promote global well-being within each patient.”

The one-year and five-year follow-up results of the study, previously published in 2013 and 2019 respectively [

14,

15], have demonstrated a significant statistical improvement in the pts treated with STP compared to the control group, related to: depression, quality of life, new hospital admissions, new medical comorbidities and angina recurrence. An improvement was also noted in major cardiovascular events (MACE), although results were not statistically significant.

Dream analysis was a fundamental component of STP, but a systematic dream collection had not been planned before the study. Luckily details of dialogue in individual sessions was systematically reported on written reports soon after each session by the psychotherapist. Group meetings were not recorded and much precious material, in particular dream material was lost and is not part of this analysis.

As the dream material reported by the psychotherapist resulted globally of great interest, it was decided later on to extract it from the notes, to classify and translate it into English from the original Italian.

Dreams were classified into different lifetime periods:

1. Childhood and adolescence

2. Adulthood

3. Dreams in the year before AMI

4. New dreams emerged during the psychotherapeutic training. In this section the dreams have been adjudicated to every single session, from the first one to the tenth session, that was the last one in which one pt referred a new dream.

Childhood is defined as the period from infancy to the age 11, adolescence from 11 to 20, and adulthood from 20 to the beginning of the year before AMI. All pts were asked about their dreams during individual sessions.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Continuous variables were compared with the Mann-Whitney U-test, whereas frequencies were compared with Yates’s corrected Chi2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Repeated measures within group were assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test or by the Friedman test. A P value<0.05 (2-tailed) was considered significant, 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported when possible.

Results

Among the 54 pts initially randomized to the STP group, five refused to continue the study, resulting in 49 pts in the treatment group. In 2 of 49 pts the notes on dream history were not available, leaving 47 pts available for analysis. Pts were 31 to 70 years old (mean age 55±8); the group included 3 women and 44 men. Four pts completed only the individual sessions but discontinued the STP before group meetings.

Supplemental Table S1 shows the complete dream material collected, as told spontaneously from the 47 pts, and subdivided into different lifetime periods.

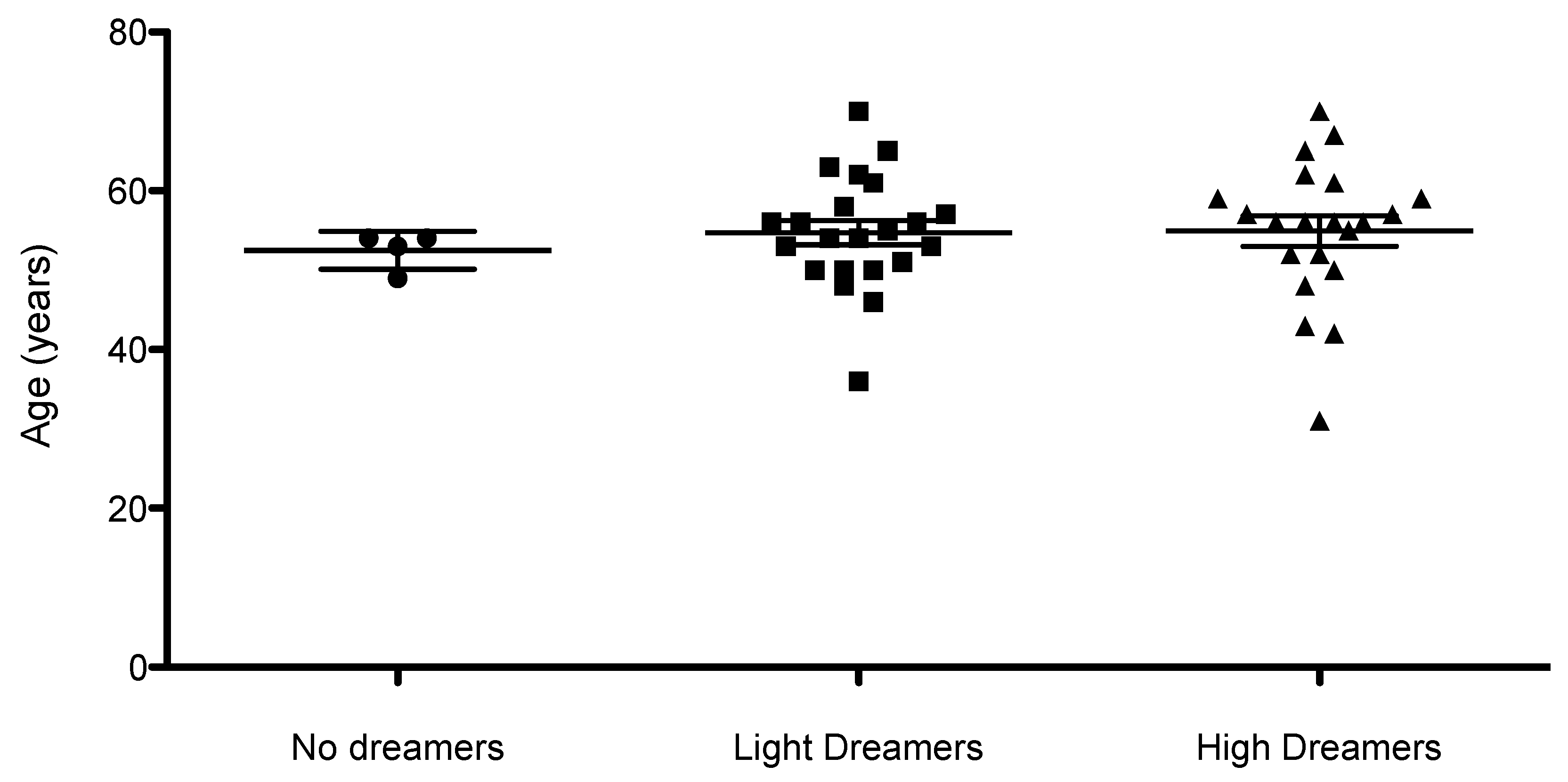

We idfentified 3 classes of pts with respect the ability to remember dreams:

A) 4 /47 pts (8%), age 53±2, could not report any dreams, during their entire lives as well as during psychotherapy (« no dreamers »).

B) 22 /47 pts (47%), age 55±7, could not remember dreams from childhood to the AMI time, but began to remember dreams during psychotherapy (« light dreamers »).

C) 21 /47 pts (45%), age 55±9 reported dream material related to their life before AMI, as well as dreams during individual psychotherapy (« high dreamers »).

Some pts had “dreaming images” during the body relaxation exercises (that induced a state similar to a light sleep) utilized during the psychotherapy sessions. These spontaneous images might be considered of the same origin of nocturnal dream images, and for this reason they have been considered available for the analysis and reported in Table 1 [

22].

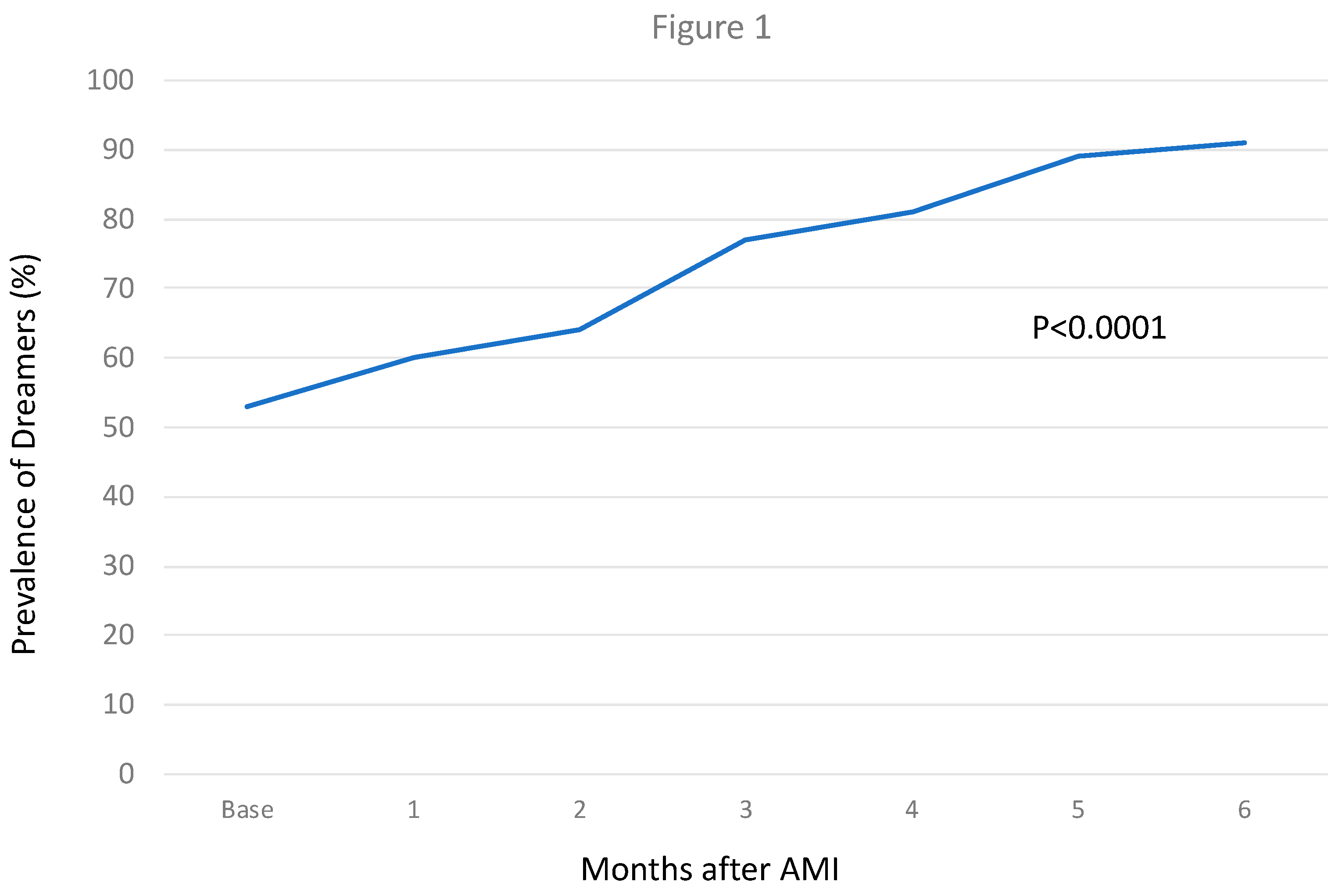

The number of patients able to remember dreams increased from 21/47 (45% with 95% Confidence Interval 31-59%) at baseline to 43/47 (91% with 95% Confidence Interval 82-98%) with psychotherapy (P=0.000003), corresponding to a Risk difference for 46% (95% CI 30-63%).

See

supplemental Table S1, and

Figure 1 for the temporal trend of patients’ ability to remember dreams from their past and during psychotherapy. There was a progressive increase in patients’ ability to remember dreams during psychotherapy, with a peak at the fifth meeting (

Figure 1).

Figure 2 is a scatter plot of patients’ age, that shows no differences in patients’ age related to their ability to remember dreams.

Supplemental Table S2 presents a summary of the main symbols that have been extracted from the dreams. Dream symbols included people, animals, non-animated objects, places, landscapes, environment, situations, actions, and states of mind. A column is dedicated to recurrent dreams. This classification has been reported and modified from Meneghetti A. [

22] and Giuliani M. [

23]

Recurring dreams in the years before AMI were common (16/47 pts, 34%). No pts had recurring dreams after the third session (

P<0.001). Recurrent dreams were characterized by the pts as states of anguish, despair, an inability to complete an action, or grief over one’s mother’s early death (see

supplemental Table S3, I A, B, C, D, E, F).

There was little dream content in the reports of the 3 pts who referred no-recurring dreams in childhood and adolescence (

Table S3, II).

Symbols frequently reported in the different periods of life prior to AMI reveal psychological difficulty and conflict (

Table S3, III).

In the year before AMI (

Table S3, III, CC) 12 of the 25 symbols listed referred to people known to the pts, and who had died of a cardiac disease; 9 of 25 symbols referred to an accident, danger, nightmares and distressing dreams. Globally, 21 of 25 symbols were associated with danger for the individual life (84%). We define these symbols as “negative”, because refer to situations that highlight a threat for the pts’ bio-psychic unity.

For symbols reported during the psychotherapeutic phase, we have considered the 47 pts as a whole, who did an evolution from the first to the last individual session. For this reason, from a psychotherapeutic perspective, we analyzed dreams divided in two phases: a first phase, putting together the symbols reported during the first three sessions, and a second phase, putting together the symbols referred from the forth to the last session.

In the first psychotherapeutic phase (

Supplemental Table S4, A), the “negative” symbols (in cursive) were 26 of the 81 symbols listed (32%). In the second psychotherapeutic phase (

Table S4, B), the “negative” symbols reported in cursive were 14 of 164 (9%). Thus, the incidence of negative symbols was sharply reduced after AMI and during psychotherapy (from 84% to 32% during the first psychotherapeutic phase; P<0.001). They reduced more to 9% in the second psychotherapeutic phase, with a very high statistical difference compared to the year before AMI (

P<0.0001).

Symbols revealing an internal rebirth (in bold in

Table S4) of the pts were 32 of 164. They were defined as an “internal rebirth” because referring to vital situations (young people, children, sunny landscapes, etc.).

The remaining 118 symbols were material classified as useful for clinical analysis (

Table S4).

Discussion

Our study shows that pts with AMI frequently do not remember or report distressing dreams before AMI. STP after AMI significantly increased patients’ ability to remember dreams and sharply reduced the incidence of negative/distressing dreams.

Interpretation of dreams has been a challenge for philosophers, psychologists and scientists in every age. Yet, despite continuous progress in psychotherapy, it is still not clear if dream analysis may have a role in the identification of psychosomatic patterns, particularly in medical conditions.

Sigmund Freud, the psychoanalysis founder, in his innovative treatise “Dream Interpretation,” published in 1899 [

24,

25], cites two Aristotle works - De Divinatione Per Somnium, and De Somniis [

26,

27], and Ippocrate’s work - Corpus Ippocraticum [

28] -, that explore possible relationships between dreams and illness. Freud emphasized that an internal bodily stimulus may contribute to dream plot formation [

24,

25]. He presented a case report from Artigues of a 43 year-old woman with nightmares over many years before her death from cardiac disease. In Freud’s observations distressing dreams are frequent in patients with heart and lung disease. He cites Tissiè, who affirms that diseased organs confer a characteristic pattern to dream content.

Following Carl Gustav Jung, Analytic Psychology founder, dreams are an integral and fundamental expression of the individual unconscious [

29], that communicates by means of symbols. The aim of this communication is represented by integration and self realization.

Ontopsychology is a recent development in psychodynamic theory. Its perspective on dream analysis is based on the hypothesis that the unconscious is guided by a natural criterion, through which it is possible to distinguish what is useful and functional for the dreamer’s identity. It has been denominated

ontic In Itself [

22,

30,

31]. The

ontic In Itself characterizes our specific identity, acting through the vital boost that drives human life, the psychic project throughout one’s life, trying to bring a person to self-realization, in the biological, affective, social and spiritual dimensions. Following this view, the first step of self-realization is represented by body and psychic health. For this reason, dream symbols are mainly focused basically to reveal to the subject’ ego the presence of an incipient initial disease.

If confirmed, in this perspective dreams might be considered the very first signal for a medical diagnosis and prevention.

This premise is fundamental, because the STP in this group of pts was conducted following an ontopsychological method, which considers dream analysis fundamental to psychotherapy.

It must be noted that the present paper is not a psychodynamic analysis of dream material collected during the STP of AMI pts, but highlights some unexplored characteristics of this pts population, that emerged during psychotherapy.

The first observation that emerges is the high percentage of pts not remembering dreams before AMI (55%). Sleep medicine has shown a close association between rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and dreaming [

32], concluding that every person dream during sleep. The reason why one does not remember dreams remains an open question. One cause of not remembering dreams may be the use of psychotropic drugs [

33], but in this cohort, only one was taking psychiatric drugs, and no-one was given a hypnotic treatment; moreover, the one pt taking psychiatric drugs since adolescence did not remember past dreams, but did remember dreams during psychotherapy.

In other studies it has been hypothesized that age issues are essential for dreaming recall, related to brain sleep maturation, from fetal development to early childhood, going through adulthood and elderly [

34]. However, in our study, there was no difference in age associated with the ability to recall dreams, possibly due to the narrow age range of our pts (most patients were between 50-70 years, with no pts over 70).

From a psychological point of view not remembering dreams may be an expression of a censure and psychic repression caused by a strict education in infancy.

For these reasons we can hypothesize that “not remembering dreams” may have here a clinical significance, and from a psychodynamic point of view it seems a lack of awareness of the individual related to her/his interior personal life, like a progressive psychic repression started very early in life. This observation is coherent with the remark of a high incidence of “alexithimia” in cardiac pts [

35]. Alexithymia literally means ‘no words for emotions and is referred to a condition in mental health settings when people have difficulties in identifying and verbalizing their emotional states. This mechanism reinforces the view that these pts don’t have a complete consciousness of their states of mind and have acquired the habit to continuously convert their emotions in a psychosomatic reaction, in coherence with what affirmed by psychosomatic medicine [

36,

37,

38].

Another frequent dream pattern in this cohort are the recurrent dreams in the life period before AMI. 16/47 pts (34%) reported recurrent dreams before AMI, referred as nightmares, or a state of anguish, despair, the perception of an inability to complete an action, or the grief of own mother’s early death.

Although nightmares may be caused by psychiatric drugs [

39], only one pt was taking them, and he did not report nightmares.

From a psychodynamic perspective recurrent dreams may represent an effort by the unconscious to signal a problem to the person’s ego, a problem or conflict that might compromise the harmonic body and psychic evolution of the individual. In fact the recurrent dreams reported extensively in

Table S3 highlight a difficulty, an inability to overcome an obstacle or to reach a goal, an anguish, a danger, or the need to pass an exam. In only few is there an escape or an attempt of sublimation from life difficulties (

Table S3, A3, A6, and B7).

If we evaluate the main symbols that emerged in infancy and childhood (

Table S3, IA, III AA) they reinforce the interpretations of a difficulty in personal growth and evolution emerging very soon in life.

Symbols seem emerge here like knots of a net delineating the common ground of a collective unconscious, in a very similar and repetitive psychodynamic mechanism.

In the year before AMI the scenery set is still worse than before. Particularly 12 of the 25 symbols listed referred to people known to the pts who had died of a cardiac disease; 9 of 25 symbols referred to an accident, danger, nightmares and distressing dreams (

Table S3, III, CC). Globally, 21 symbols of 25 (84%) highlight danger for the individual’s life. We have defined these symbols as “negative”, because they referred to situations that highlight a threat for the pts’ bio-psychic unity: they seem to warn of a danger of cardiac death.

The relationship between cardiac death warning symbols and incident AMI may confirm the ontopsychological hypothesis that dream symbols may be related to the biological status of the dreamer, warning months in advance of an impending cardiac event.

During psychotherapy dream patterns change, and there is a statistically significant difference for all the three patterns described.

The number of pts able to remember dreams increased from 25/47 (53%) at baseline to 43/47 (91%) with a statistical significant difference, as if psychotherapy had acted as a stimulus for inner insight. This may be considered also as a sign of trust and open-mindedness toward the psychotherapist.

For an analytic evaluation of dreams, psychotherapy was divided in two phases: the first, collecting the symbols reported in the first three sessions, and a second, collecting the symbols reported from the fourth to the tenth session. This distinction was necessary to allow time for pts to develop inner change.

After the third session recurring dreams stopped completely, with a high statistical difference compared to recurrent dreams in the years before infarction. Moreover, during psychotherapy there was a change in reported symbols. In particular the incidence of “negative” symbols sharply was reduced after AMI and during psychotherapy, from 84% to 32% during the first psychotherapeutic phase, and to 9% in the second phase, with a statistically significant difference compared to the year before AMI.

During psychotherapy there were some “positive” symbols of natural landscapes, or young people, or wild animals. They seem to reflect an internal rebirth in some patients. Other symbols reported during psychotherapy show a wider scenario, connected to pts’ real life, useful for clinical analysis.

The cessation of recurrent distressing dreams and the reduction of the incidence of “negative” symbols during psychotherapy strengthens the hypothesis that psychotherapy acted as a positive stimulus for personal change. This psychological “positive” change might also be supported by results previously published in the STEP IN AMI trial [

14,

15], that showed statistically significant psychological and clinical improvement in the PTS group compared to the control group.

Limitations

Dreams reported during group meetings were not recorded, thus possibly missing interesting material and dreams reported by pts. However, this did not influence our data on the dreams occurring before AMI.

Due to the low number of female pts, it was not possible to perform a qualitative and quantitative analysis of dream pattern between the sexes.

Related to dream recall in different pts age groups, the narrow age range does not permit evaluation between age and the ability to recall dreams.

The classification reported is extracted from hundreds of individual psychotherapy sessions conducted in the STEP IN AMI trial, which utilized ontopsychological methodology. Consequently, symbol analysis reflects the methodology used.

Dream analysis is a complex task, that can be performed only in the psychotherapeutic setting, and after a comprehensive knowledge of the pts’ history. Despite this limitation, we have extracted specific symbols to better analyze similarities of dream patterns in this cohort of pts.

This is the first research that attempts to analyze dream patterns in AMI pts. Moreover, thanks to Ontopsychology that has introduced symbols’ interpretation based on a biological meaning, it introduces a great novelty in psychotherapy research, and may favor a deep integration between medicine and psychotherapy. However, it must be underscored that our results cannot be directly extrapolated to different psychoterapeutic strategies.

The stress axis, cortisol secretion or other biological pathways might be important in this group of pts, also to explain the production of specific dream content [

4,

6,

7]. Unfortunately the STEP IN AMI trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a Short Term Psychotherapy in a selected population of AMI pts, and endocrine biological samples, in particular cortisol samples, were not scheduled in the trial protocol. They might be added in future research.

A study is needed to evaluate dreams in a larger cohort of AMI pts, in order to compare our results with a healthy subject control group. For this reason, a new research protocol is ongoing: the PSYCHONIC (PSYChosomatic medicine in ONcologIc and Cardiac disease) trial [

40].

Conclusions

On the basis of these results, we hypothesize that: 1) the high percentage of pts not remembering dreams before AMI may be expression of a censure and psychic repression; 2) the high percentage of symbols of people who died of cardiac disease and symbols of an accident, danger, nightmares and distressing dreams in the year before AMI might indicate that dreams are connected to the biological status of the dreamer, warning the dreamer of his cardiac condition, coherent with the ontopsychological theory; 3) the progressive increase of the ability of the pts to remember dreams, the cessation of recurrent distressing dreams and the reduction of the incidence of “negative” symbols during psychotherapy, strengthens the fact that psychotherapy acted as a positive stimulus for inner personal change; 4) if these data are confirmed in other research, dream analysis might become a fundamental tool to integrate in psychological intervention and rehabilitation of AMI pts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and C.P.; Methodology, A.R., C.P. and V.P.; Software, A.R.; Validation, V.P., R.A. and F.P.; Formal Analysis, V.P.; Investigation, A.R.; Resources, A.R.; Data Curation, A.R.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.R., D.I., L.D.M. and G.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, R.A. and V.P.; Visualization, G.S.; Supervision, R.A.; Project Administration, A.R.; Funding Acquisition, A.R.”.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss Scientific and Humanistic Research Foundation Antonio Meneghetti, Award 2014 for the research in Medicine, assigned to “Roncella A, et al., One-year results of the randomized, controlled, short-term psychotherapy in acute myocardial infarction (STEP-IN-AMI) trial, Int J Cardio (2013)

Acknowledgments

To the Swiss Scientific and Humanistic Research Foundation Antonio Meneghetti for Antonio Meneghetti Award 2014 for the research in Medicine, assigned to “Roncella A, et al., One-year results of the randomized, controlled, short-term psychotherapy in acute myocardial infarction (STEP-IN-AMI) trial, Int J Cardio (2013)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aserinsky, E., Kleitmann, N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility and concomitant phenomena during sleep. Science 1953, 118, 273-274. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Michele, L. Sleep and Dreams in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. In Psychotherapy for Ischemic Heart Disease. An Evidence-Based Clinical Approach, 1st ed.; Roncella, A., Pristipino, C.,Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 73-82.

- Full, K.M., Huang, T., Shah, N.A., Allison, M.A., Michos, E.D., Duprez, D.A., Redline, S., Lutsey, P.L. Sleep Irregularity and Subclinical Markers of Cardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc 2023, 21, 12 (4):e027361.

- Pristipino, C. Complex Psychoneural Processes in Ischemic Heart Disease: Evidences for a Systems Medicine Framework. In Psychotherapy for Ischemic Heart Disease. An Evidence-Based Clinical Approach, 1st ed.; Roncella, A., Pristipino, C.,Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3-27.

- Hung, M.J., Cheng, C.W., Yang, N.I., Hung, M.Y., Cherng, W.J. Coronary vasospasm-induced acute coronary syndrome complicated by life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias in patients without hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease.Int J Cardiol 2007, 117(1), 37-44.

- Thrall, G., Lane, D., Carroll, D., Lip, G.Y. A systematic review of the effects of acute psychological stress and physical activity on haemorheology, coagulation, fibrinolysis and platelet reactivity: Implications for the pathogenesis of acute coronary syndromes. Thromb Res 2007, 120(6), 819-47.

- Halaris, A. Inflammation-Associated Co-morbidity Between Depression and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2017, 31, 45-70. [PubMed]

- Meisinger, C., Heier, M., Lowel, H., Döring, A. Sleep duration and sleep complaints and risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged men and women from the general population: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. Sleep 2007, 30, 1121–1127.

- Chien, K.L., Chen, P.C., Hsu, H.C., Su, T.C., Sung, F.C., Chen, M.F., Lee, Y.T. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death: report from a community-based cohort. Sleep 2010, 33, 177–184.

- Clark, A., Lange, T., Hallqvist, J., Jennum, P., Hulvej, Rod, N. Sleep Impairment and Prognosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Prospective Cohort Study. SLEEP 2014, 37 (5), 851-8.

- Parman, M.S., Luque-Coqui, A.F. Killer dreams. Can J Cardiol 1998, 14(11):1389-91.

- Roncella, A. Short-Term Psychotherapy in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. In Psychotherapy for Ischemic Heart Disease. An Evidence-Based Clinical Approach, 1st ed.; Roncella, A., Pristipino, C.,Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 187-201.

- Roncella, A., Giornetti, A., Cianfrocca, C., Pasceri, V., Pelliccia, F., Denollet, J., Pedersen, S.S, Speciale, G., Richichi, G., Pristipino, C. Rationale and trial design of a randomized, controlled study on short-term psychotherapy after acute myocardial infarction: the STEP-IN-AMI trial (Short Term Psychotherapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction). J of Cardiovasc Med 2009, 10, 947-452.

- Roncella, A., Pristipino, C., Cianfrocca, C., Scorza, S., Pasceri, V., Pelliccia, F., Denollet, J., Pedersen, S.S, Speciale, G. One-year results of randomized, controlled, short-term psychotherapy in acute myocardial infarction (STEP-IN-AMI) trial. Int J Cardiol 2013, 10;170(2), 132-9.

- Pristipino, C., Roncella, A., Pasceri, V., Speciale, G. Short-TErm Psychotherapy IN Acute Myocardial Infarction (STEP-IN-AMI) Trial: Final Results. Amer J of Med 2019, 132, 639−646. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a psychology of being; Van Nostrand Company Inc.: New York, USA, 1962.

- Blalock, J.E. Amolecular basis for bidirectional communications between the immune and neuroendocrine systems. Physiol Rev 1989, 69, 1–32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmandari, E., Tsigos, C., Chrousus, G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol 2005, 67, 259–84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, P.H. The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response. Brain Behav Immun 2003, 17, 350–64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besedovsky, H.O., Del Rey, A. Cytokines as mediators of central and periferal immune–neuroendocrine interactions. In: Psychoneuroimmunology, 3rd ed.; Ader, R., Felten, D., Cohen, N., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001.

- Levine, G.N. The Mind-Heart-Body Connection. Circulation AHA 2019, 22 , 140(17), 1363-1365. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghetti, A. L’Immagine e l’Inconscio, 3rd ed.; Psicologica Editrice: Rome, Italy, 2003.

- Giuliani, M., Palumbo, G The convergent validity of the ontopsychological procedure of dream content analysis. Int J of Dream Res 2024, 17 (2), 208-214.

- Freud, S. Die Traumdeutung, 1st ed.; Franz Deuticke: Leipzig und Wien, Germany, 1900.

- Freud, S. Dream Interpretation, 4th ed.; Hogart Press: London, Great Britain, 1953.

- Aristoteles. Parva Naturalia: De Insomniis. De Divinatione Per Somnum: Vol 14/III; Akademie Verlag, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung: Berlin Germany, 1994.

- Aristoteles. De Anima: De Sensu, De Memoria, De Somno Similique Argumento (1830); Kissinger Publishing: Whitefish, USA, 2010.

- Corpus Hippocraticum VOL VII, Traduccion Revision y Notas de Ana Gomez Rabal. MRA: Barcelona, Spain, 1997.

- Jung, C.G., von Franz, M.L., Henderson, J.L., Jacobi, J., Jaffè, A. Man and his Symbols; Aldus Books Limited: London, Great Britain, 1967.

- Cangelosi, A., Mencarelli, C., Volpicelli, C., Giovannelli, L., Buonanno, E., Bernabei, P. Dreams: in the depths of our reality. New Ontopsychology, Ontopsicologia Editrice: Rome, Italy, 2006, 2, 30-61.

- Meneghetti, A. L’In Sé dell’Uomo, 4th ed.; Ontopsicologia Editrice: Rome, Italy, 2002.

- Eiser, A.S. Physiology and psychology of dreams. Semin Neurol 2005, 25(1), 97-105. 33).

- Berry, R.C., Wagner, M.H. Psychiatry and Sleep, chapter 41. In SLEEP MEDICINE PEARLS, 3rd ed.; Berry, R.,C., Wagner, M.H., Eds.; ELSEVIER SAUNDERS: Philadelphia, USA, 2015.

- Mangiaruga, A., Scarpelli, S., Bartolacci, C., De Gennaro, L. Spotlight on dream recall: the ages of dreams. Nat Sci Sleep 2018, 9, 10:1-12.

- Montisci, A., Sancassiani, F., Marchetti, M.F., Biddau, M., Carta, M.G., Meloni, L. Alexithymia for cardiologists: a clinical approach to the patient. J Cardiovasc Med 2023, 24, 392–395. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, F. PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE. Its principles and applications. W.W. NORTON and COMPANY.INC.: New York, USA, 1959.

- Meneghetti, A. La psicosomatica nell’ottica ontopsicologica. Ontopsicologia Editrice: Rome, Italy, 1974-2008.

- Meneghetti A. Handbook of Ontopsychology. Ontopsicologia Editrice: Rome, Italy, 1995-2008.

- Berry, R.C., Wagner, M.H. Effects of Sleep Disorders and Medications on Sleep Architecture”, chapter 8,. In SLEEP MEDICINE PEARLS, 3rd ed.; Berry, R.,C., Wagner, M.H., Eds.; ELSEVIER SAUNDERS: Philadelphia, USA, 2015.

- Roncella, A., Pristipino, C., Di Carlo, O., et al. PSYChosomatic Medicine in ONcologIc and Cardiac Disease (PSYCHONIC) Study—A Retrospective and Prospective Observational Research Protocol. J Clin Med. 2021, 10(24), 5786.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).