Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Retrieval

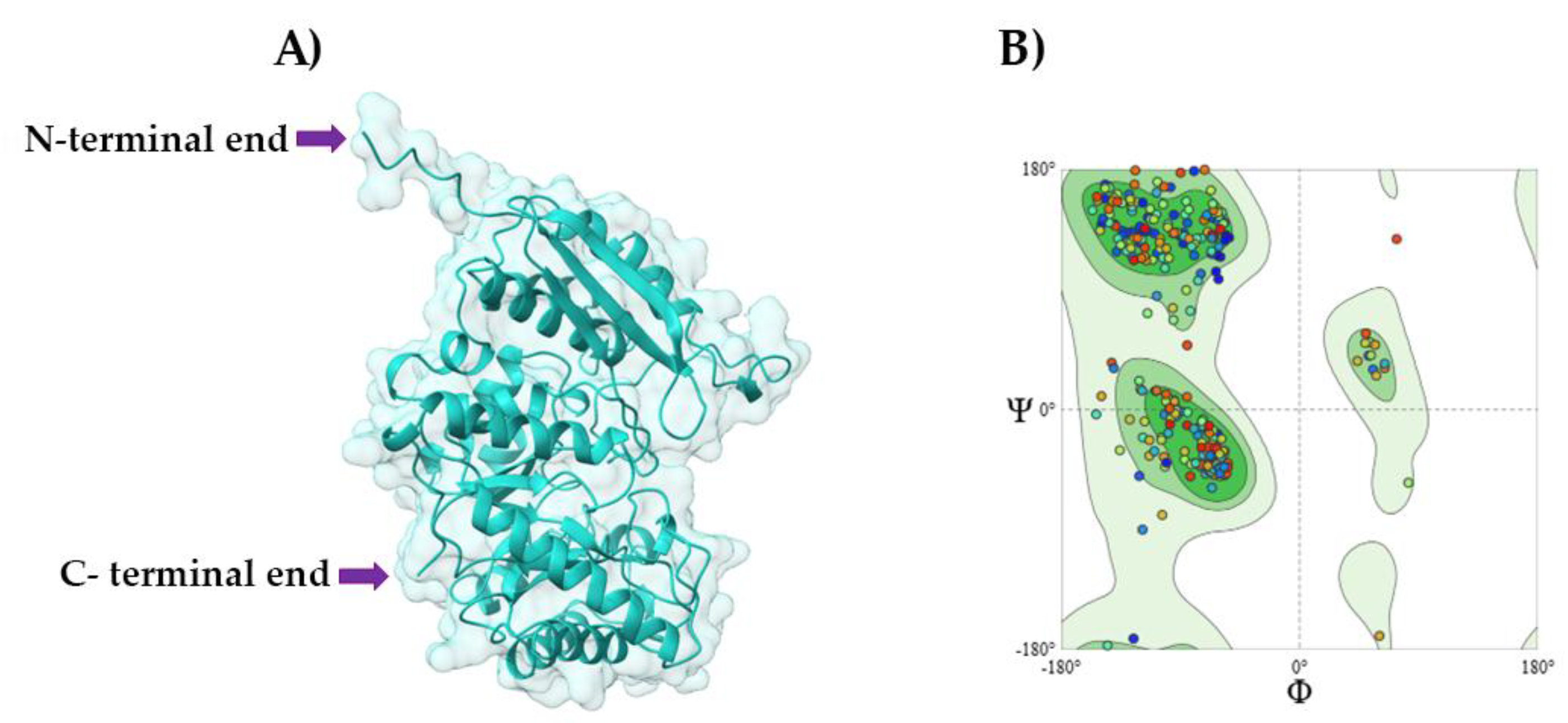

2.3. Tridimensional (3D) Modeling

2.4. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

2.5. AmEno15 Recombinant Expression

2.6. Microplate Binding Assays to Erythrocyte Membrane Proteins, Plasminogen, and Fibronectin

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

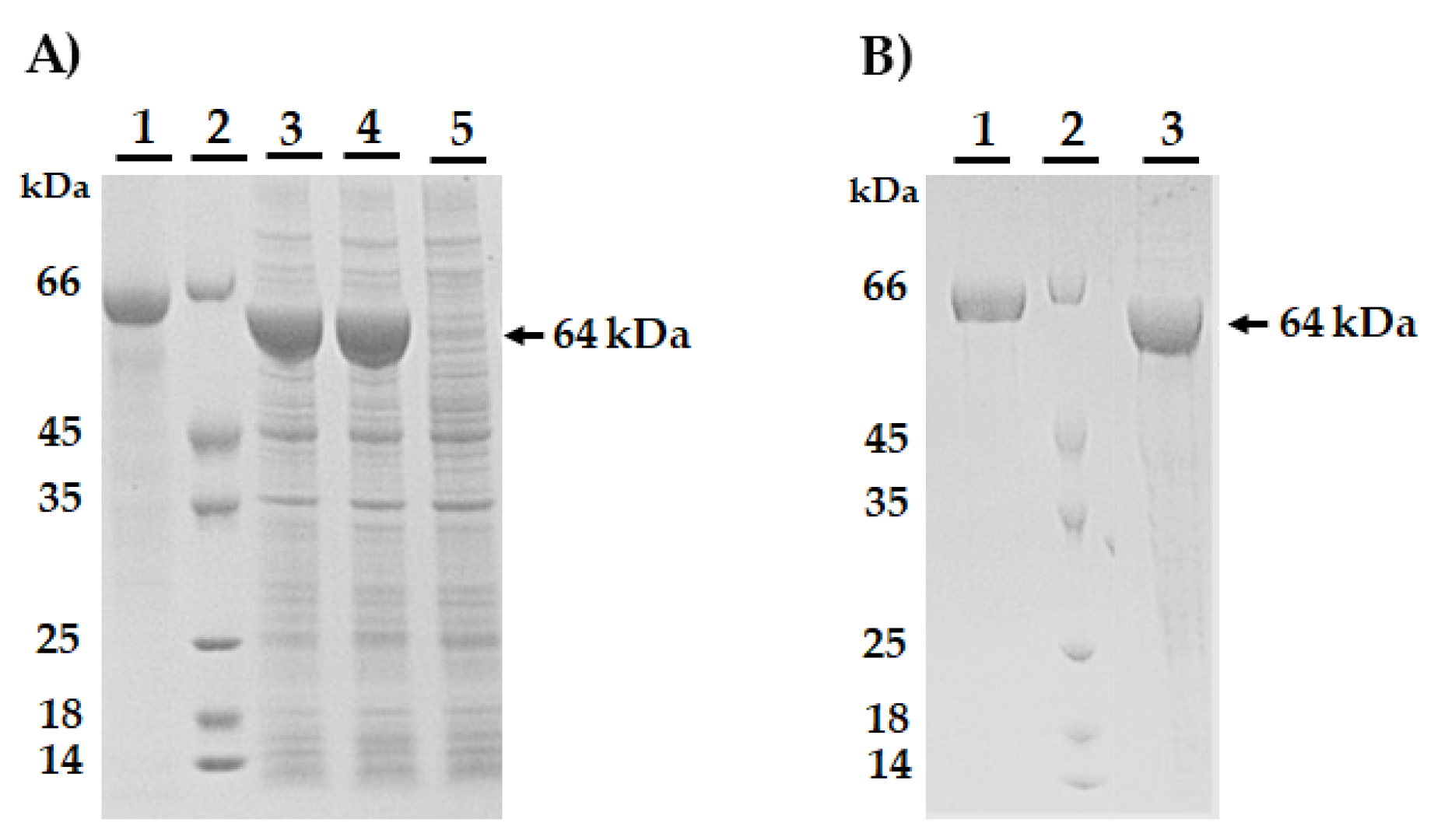

3.2. AmEno15 Recombinant Expression

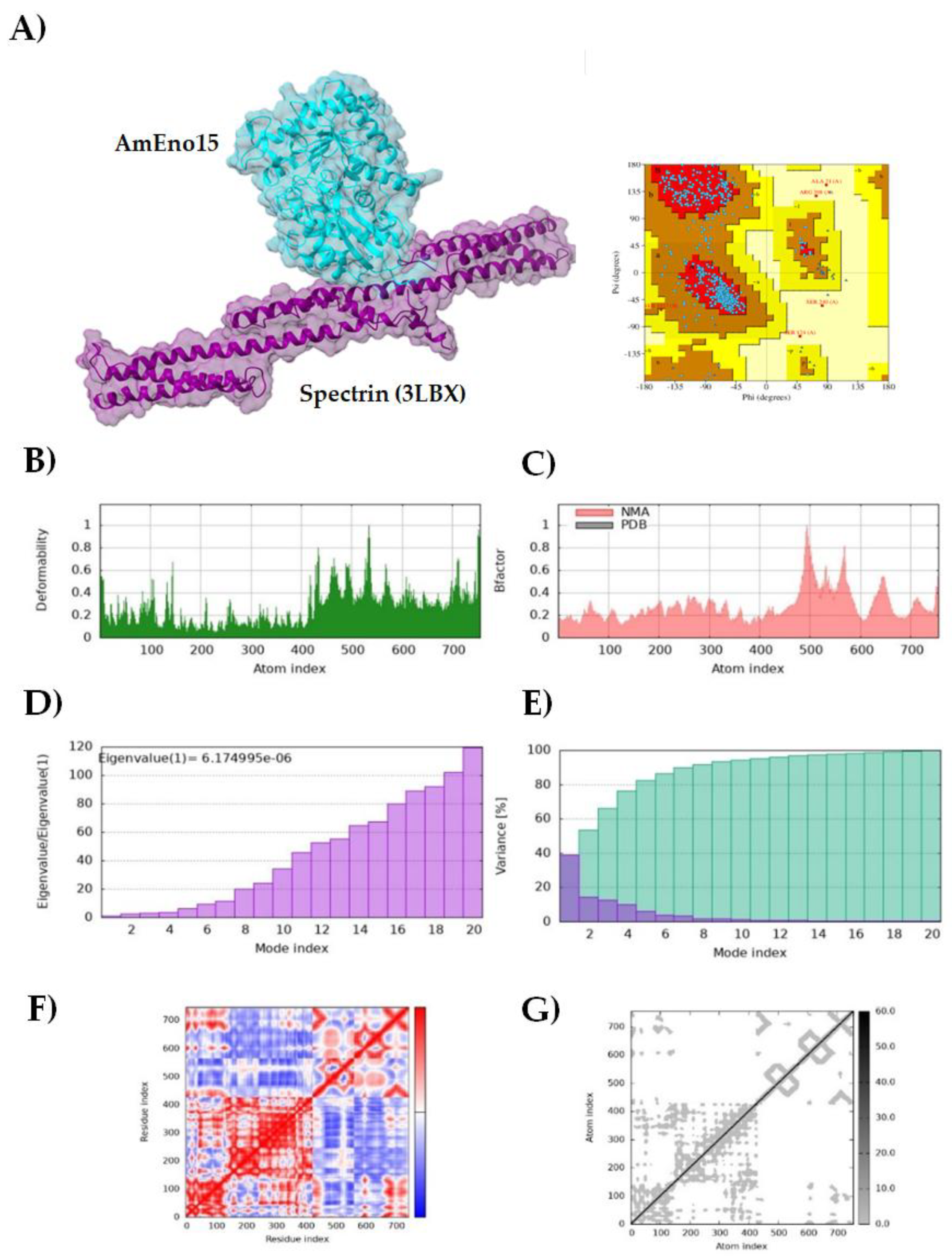

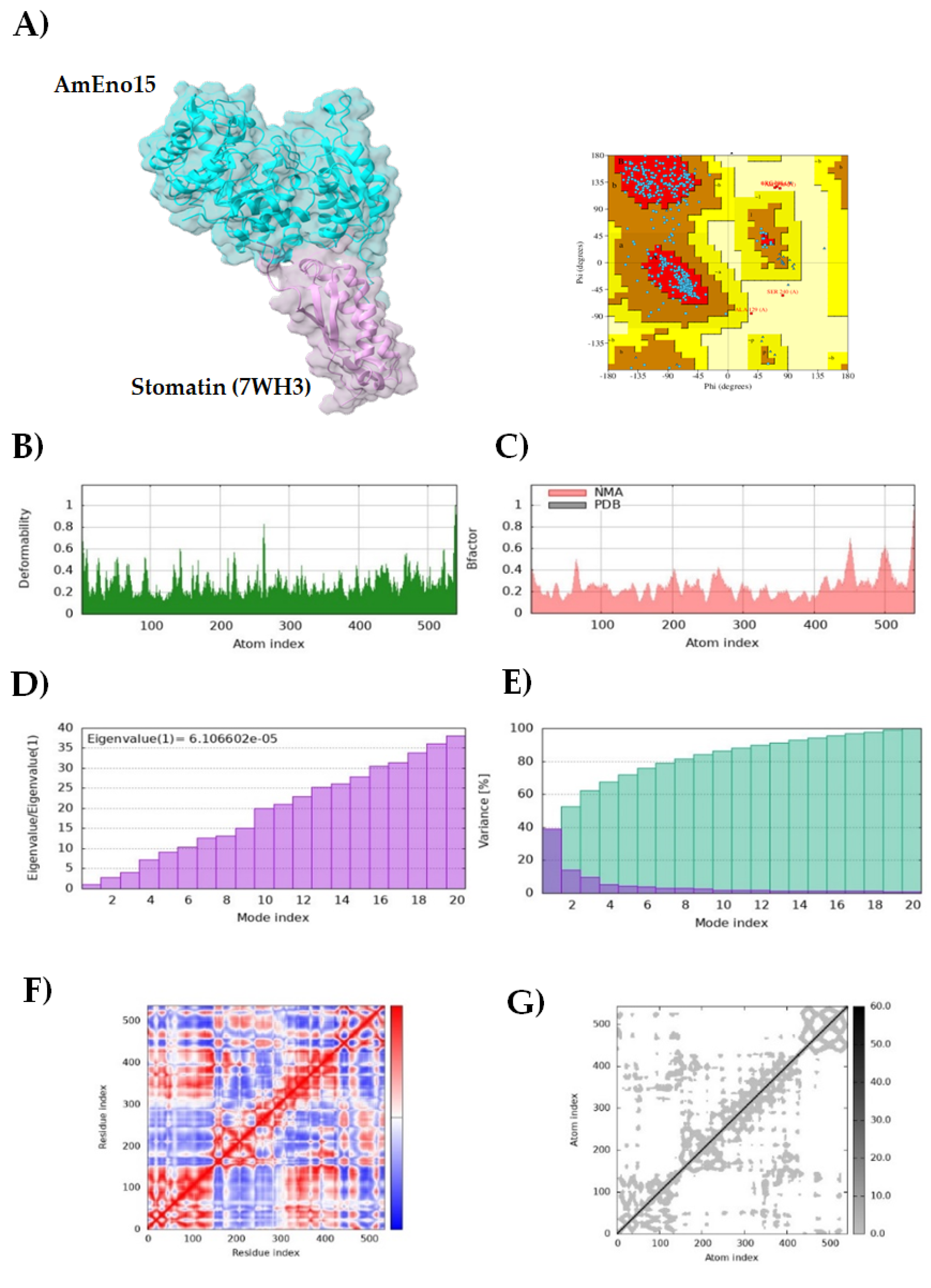

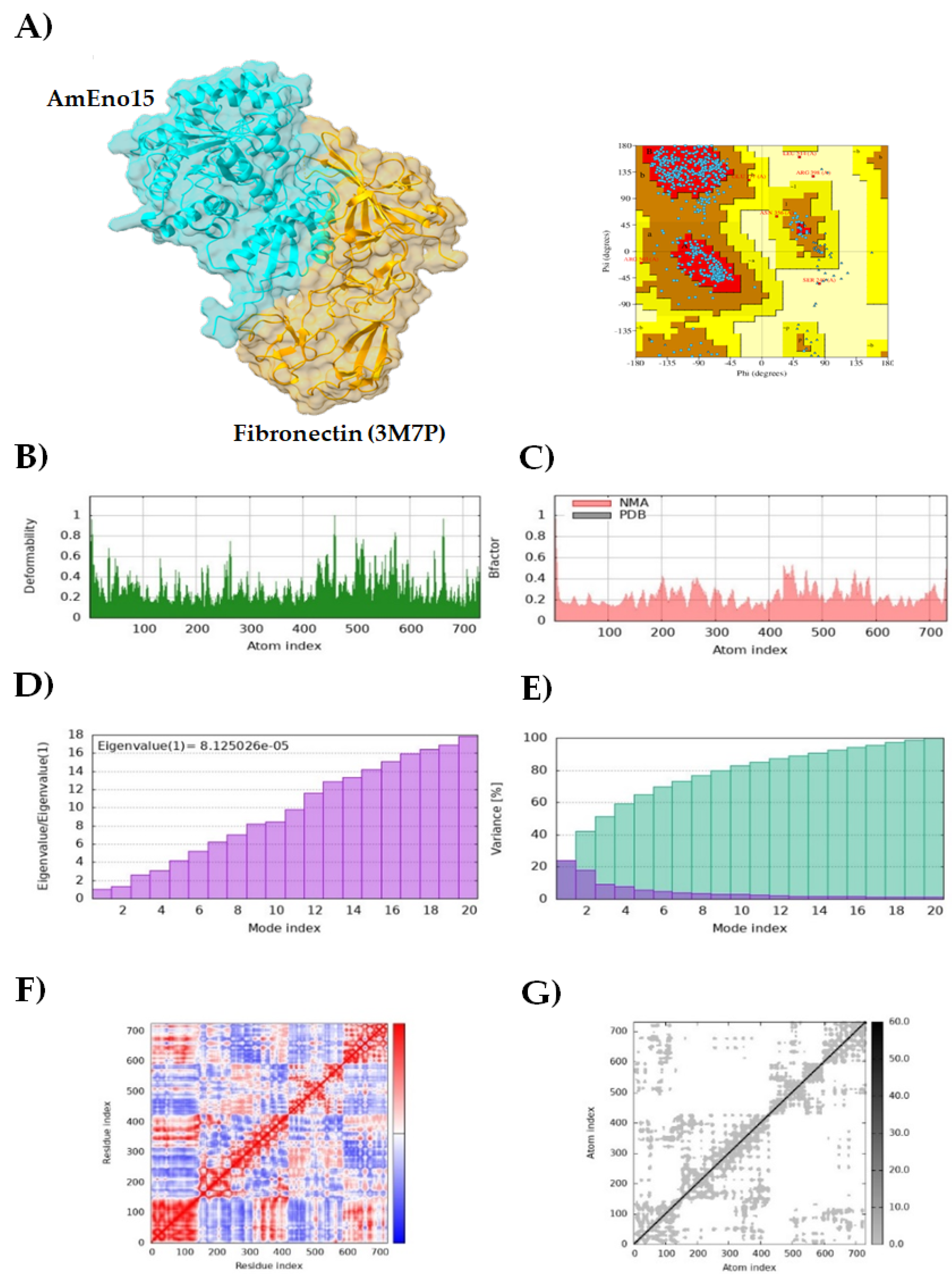

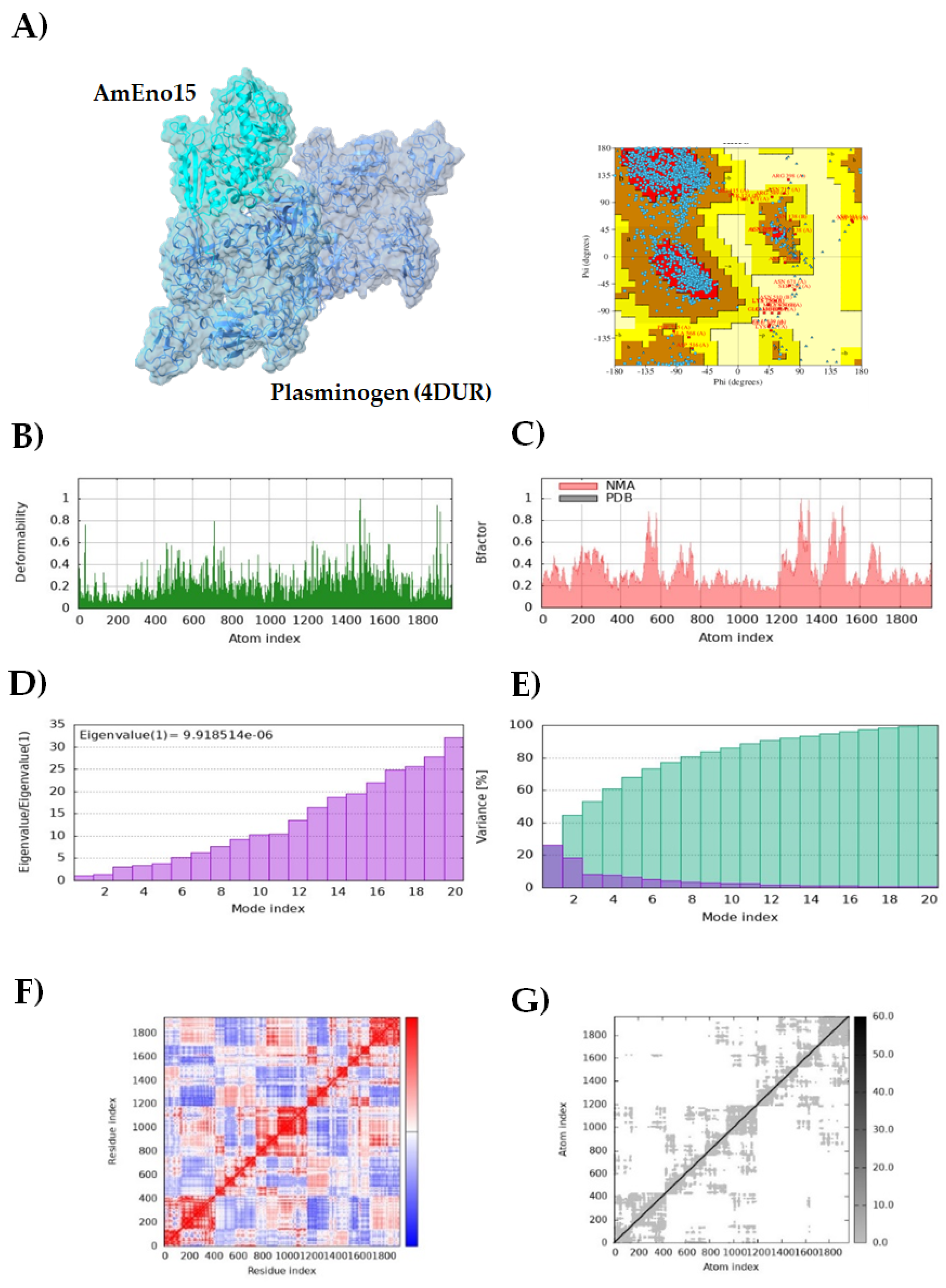

3.2. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

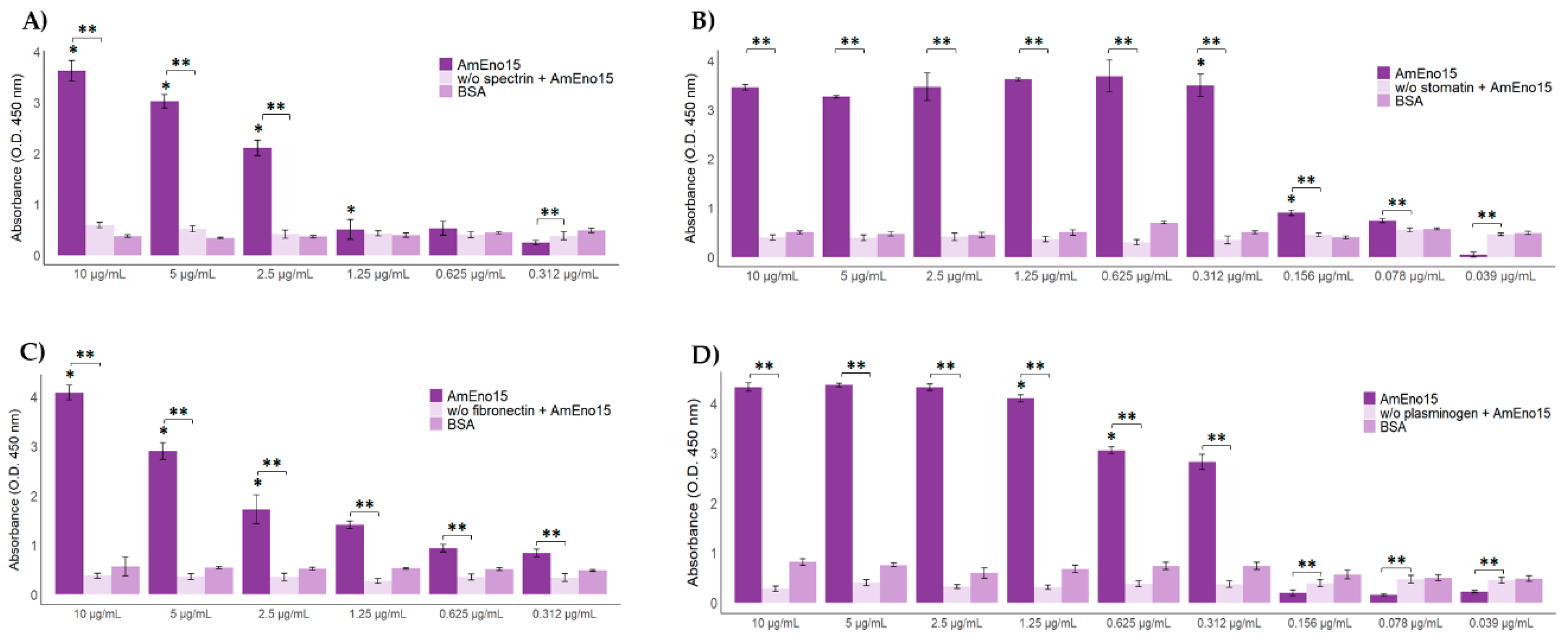

3.3. Microplate Binding Assays to Stomatin, Spectrin, Plasminogen, and Fibronectin

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgements

References

- Kuttler, K.L. Anaplasma Infections in Wild and Domestic Ruminants: A Review. J. Wildl. Dis. 1984, 20, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocan, K.M.; de la Fuente, J.; Blouin, E.F.; Coetzee, J.F.; Ewing, S. a. The Natural History of Anaplasma Marginale. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 167, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, P.; Geale, D.W. A Review of Bovine Anaplasmosis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocan, K.M.; de la Fuente, J.; Blouin, E.F.; Garcia-Garcia, J.C. Anaplasma Marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae): Recent Advances in Defining Host–Pathogen Adaptations of a Tick-Borne Rickettsia. Parasitology 2004, 129, S285–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbet, A.F.; Blentlinger, R.; Yi, J.; Lundgren, A.M.; Blouin, E.F.; Kocan, K.M. Comparison of Surface Proteins of Anaplasma Marginale Grown in Tick Cell Culture, Tick Salivary Glands, and Cattle. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Acedo, C.S.; Quílez, J.; Del Cacho, E. A Retrospective Study of Climatic Suitability for the Tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus)Microplus in the Americas. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005, 14, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangussu, A.S.R.; Mariúba, L.A.M.; Lalwani, P.; Pereira, K.D.E.S.; Astolphi-Filho, S.; Orlandi, P.P.; Epiphanio, S.; Viana, K.F.; Ribeiro, M.F.B.; Silva, H.M.; et al. A Hybrid Protein Containing MSP1a Repeats and Omp7, Omp8 and Omp9 Epitopes Protect Immunized BALB/c Mice against Anaplasmosis. Vet. Res. 2018, 49, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, K.; Norimine, J.; Hope, J.C.; Brown, W.C. Breadth of the CD4+ T Cell Response to Anaplasma Marginale VirB9-1, VirB9-2 and VirB10 and MHC Class II DR and DQ Restriction Elements. Immunogenetics 2012, 64, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Martin, A. Bacterial Virulence in the Moonlight: Multitasking Bacterial Moonlighting Proteins Are Virulence Determinants in Infectious Disease. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3476–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esgleas, M.; Li, Y.; Hancock, M.A.; Harel, J.; Dubreuil, J.D.; Gottschalk, M. Isolation and Characterization of α-Enolase, a Novel Fibronectin-Binding Protein from Streptococcus Suis. Microbiology 2008, 154, 2668–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Castañeda, R.E.; Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Coronado-Villanueva, E.; Catalán-Ochoa, D.I.; Amaro-Estrada, I. Molecular Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of Anaplasma Marginale Moonlighting Proteins as Possible Antigenic Targets. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Singh, R.; Sur, S.; Bansal, S.; Chaudhry, U.; Tandon, V. Moonlighting Proteins: Beacon of Hope in Era of Drug Resistance in Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 49, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantán-González, E.; Quiroz-Castañeda, R.E.; Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Amaro-Estrada, I.; Martínez-Ocampo, F.; Rodríguez-Camarillo, S. Mexican Strains of Anaplasma Marginale: A First Comparative Genomics and Phylogeographic Analysis. Pathog. (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, C.J. What Is Protein Moonlighting and Why Is It Important? Moonlighting Proteins Nov. Virulence Factors Bact. Infect. 2016, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yuan, Z.-G.; Xu, M.-J.; Zhou, D.-H.; Zhang, X.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Wang, X.-W.; Yan, C.; Lin, R.-Q.; Zhu, X.-Q. Ascaris Suum Enolase Is a Potential Vaccine Candidate against Ascariasis. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3478–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Pan, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Shao, Z.; Ge, J.; Zheng, F.; et al. Streptococcus Suis Enolase Functions as a Protective Antigen Displayed on the Bacterial Cell Surface. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce-Fonseca, M.; González-Vázquez, M.C.; Rodríguez-Morales, O.; Graullera-Rivera, V.; Aranda-Fraustro, A.; Reyes, P.A.; Carabarin-Lima, A.; Rosales-Encina, J.L. Recombinant Enolase of Trypanosoma Cruzi as a Novel Vaccine Candidate against Chagas Disease in a Mouse Model of Acute Infection. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 8964085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gu, Y.; Tang, J.; Lu, F.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, G.; Cao, J.; Gao, Q. Production of Plasmodium Vivax Enolase in Escherichia Coli and Its Protective Properties. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 2855–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayón-Núñez, D.A.; Fragoso, G.; Espitia, C.; García-Varela, M.; Soberón, X.; Rosas, G.; Laclette, J.P.; Bobes, R.J. Identification and Characterization of Taenia Solium Enolase as a Plasminogen-Binding Protein. Acta Trop. 2018, 182, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz-Castañeda, R.E.; Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Amaro-Estrada, I. An Alternative Vaccine Target for Bovine Anaplasmosis Based on Enolase, a Moonlighting Protein. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1225873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xin, J.; Zou, X.; Sun, W. α-Enolase, an Adhesion-Related Factor of Mycoplasma Bovis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Xing, H.; Wen, X.; Liu, B.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xie, X.; Song, D.; Shao, G.; Xiong, Q.; et al. Identification of the Multiple Roles of Enolase as an Plasminogen Receptor and Adhesin in Mycoplasma Hyopneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 174, 105934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, S.A.; Sokoli, A.; Felder, K.M.; Wittenbrink, M.M.; Schwarzenbach, S.; Guhl, B.; Hoelzle, K.; Hoelzle, L.E. The Surface-Localised α-Enolase of Mycoplasma Suis Is an Adhesion Protein. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 156, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Seo, K.; Yang, M.; Cui, C.; Yang, M.; Xiang, S.; Yan, Z.; Wu, S.; Han, J.; Yu, X.; et al. Mycoplasma Suis Alpha-Enolase Subunit Vaccine Induces an Immune Response in Experimental Animals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satala, D.; Satala, G.; Karkowska-Kuleta, J.; Bukowski, M.; Kluza, A.; Rapala-Kozik, M.; Kozik, A. Structural Insights into the Interactions of Candidal Enolase with Human Vitronectin, Fibronectin and Plasminogen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, C.R.W.; Postol, E.; Nomizo, R.; Reis, L.F.L.; Brentani, R.R. Identification of Enolase as a Laminin-Binding Protein on the Surface of Staphylococcus Aureus. Microbes Infect. 2004, 6, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kelly, E.; Cwiklinski, K.; De Marco Verissimo, C.; Calvani, N.E.D.; López Corrales, J.; Jewhurst, H.; Flaus, A.; Lalor, R.; Serrat, J.; Dalton, J.P.; et al. Moonlighting on the Fasciola Hepatica Tegument: Enolase, a Glycolytic Enzyme, Interacts with the Extracellular Matrix and Fibrinolytic System of the Host. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzillo, M.; Vastano, V.; Capri, U.; Muscariello, L.; Sacco, M.; Marasco, R. Identification and Characterization of Enolase as a Collagen-Binding Protein in Lactobacillus Plantarum. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015, 55, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, S.; Rajeevan, N.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.O.; Heisig, J.; Pan, J.; Eppler-Epstein, R.; Deponte, K.; Fish, D.; Fikrig, E. Gut Microbiota of the Tick Vector Ixodes Scapularis Modulate Colonization of the Lyme Disease Spirochete. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, C.; Lynn, G.E.; Pedra, J.H.F.; Pal, U.; Narasimhan, S.; Fikrig, E. Interactions between Borrelia Burgdorferi and Ticks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakov, D.; Hall, D.R.; Xia, B.; Porter, K.A.; Padhorny, D.; Yueh, C.; Beglov, D.; Vajda, S. The ClusPro Web Server for Protein–Protein Docking. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting Modern Challenges in Visualization and Analysis. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Blanco, J.R.; Aliaga, J.I.; Quintana-Ortí, E.S.; Chacón, P. IMODS: Internal Coordinates Normal Mode Analysis Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft, Inc. Available online: www.statsoft.com.

- Posit Team.

- Noh, S.M.; Ujczo, J.; Alperin, D.C. Identification of Anaplasma Marginale Adhesins for Bovine Erythrocytes Using Phage Display. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.D.; Alleman, A.R.; Barbet, A.F.; Palmer, G.H.; Noh, S.M.; Johnson, C.M. In Vivo Endothelial Cell Infection by Anaplasma Marginale. Vet. Pathol. 2007, 44, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.; Garcia-Garcia, J.C.; Blouin, E.F.; Kocan, K.M. Differential Adhesion of Major Surface Proteins 1a and 1b of the Ehrlichial Cattle Pathogen Anaplasma Marginale to Bovine Erythrocytes and Tick Cells. Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, S.; Coumou, J.; Schuijt, T.J.; Boder, E.; Hovius, J.W.; Fikrig, E. A Tick Gut Protein with Fibronectin III Domains Aids Borrelia Burgdorferi Congregation to the Gut during Transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004278–e1004278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolberg, J.; Aase, A.; Bergmann, S.; Herstad, T.K.; Rødal, G.; Frank, R.; Rohde, M.; Hammerschmidt, S. Streptococcus Pneumoniae Enolase Is Important for Plasminogen Binding despite Low Abundance of Enolase Protein on the Bacterial Cell Surface. Microbiology 2006, 152, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchesi, V.T.; Steers, E. Selective Solubilization of a Protein Component of the Red Cell Membrane. Science (80-. ). 1968, 159, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Vascular Morphogenesis: An Integrin and Fibronectin Highway. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R158–R161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dyachenko, V.; Munderloh, U.G.; Straubinger, R.K. Transmission of Anaplasma Phagocytophilum from Endothelial Cells to Peripheral Granulocytes in Vitro under Shear Flow Conditions. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 204, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, E.; Cwiklinski, K.; Verissimo, C.D.M.; Calvani, N.E.D.; Corrales, J.L.; Jewhurst, H.; Flaus, A.; Lalor, R.; Serrat, J.; Dalton, J.P.; et al. Moonlighting on the Fasciola Hepatica Tegument: Enolase, a Glycolytic Enzyme, Interacts with the Extracellular Matrix and Fibrinolytic System of the Host. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).