1. Introduction

The majority of studies on the plant communities transformation have indicated progressive rates of species diversity reduction [

1,

2,

3]. "Toxic" increase of species richness in certain regions has been documented, led by the invasion of alien species and loss of native species [

4,

5]. Changes in species composition are typically the result of structural and functional disturbances of forest communities due to natural and/or anthropogenic causes [

6,

7]. The data increasingly indicate cascading effects of climate change on forest communities [

8]. Natural forest disturbances such as wildfires, windfalls and pest outbreaks, are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change or land-use change [

9].

The functional properties of species assemblages in communities relate to additional aspect of biodiversity [

9]. They provide a better understanding of the ecological consequences of disturbances or successional dynamics of communities [

10]. Functional properties are defined as a set of biological and ecological properties of species that determine the nature of plant growth and development, as well as its responses to environmental conditions [

11]. The grouping of species and structural elements of communities by functional traits is a long-standing idea recently applied to various ecological tasks [

12,

13].

Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) is one of the main forest forming species in the European part of Russia, both in terms of its distribution and economic importance. In the hemiboreal zone (mixed forests), stands dominated by spruce are considered as communities formed under the centuries-old human activity (logging, land plowing, fires and silviculture in the modern era of forestry).

Repetitive vegetation monitoring in permanent relevés is a widely used method for assessing changes in plant communities [

6,

14,

15,

16]. The importance of long-term research in old-growth forests is consistently emphasized in scientific reviews [

17,

18,

19]. Most of these studies place great importance on the issues of successional dynamics in mature communities. However, finding such forest areas, even within specially protected territories, can be complicated.

The forest cover of the Moscow region due to the prohibition of large-scale industrial logging and the protective status of forests stands out against the background of neighboring territories with a greater representation of intact forests of natural origin. This fact is a unique opportunity to study the peculiarities of autogenous successional dynamics of zonal forests. Therefore the history and dynamics of rare old-growth spruce forests of the 19th and 20th centuries are of great interest to understand the possibility of their preservation.

In this study we suggest a hypothesis of the critical state of old-growth spruce forests in the center of East European Plain, the decline of which is escalating each year due to global climate change. The aim is to identify current trends in the successional dynamics of mature spruce forests in the coniferous-broadleaved vegetation zone by repeating relevés after 40 years within the Smolensk-Moscow Upland. The results obtained using the Moscow region as an example make it possible to identify dynamic trends of spruce forests and to forecast their further development in the territory of the East European Plain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research area is located in the central part of the East European Plain (54°12'-56°55' N, 35°10'-40°15' E), and covers an area of about 4.7 million ha (

Figure 1). The average annual air temperature is 2.7°-3.8°C and precipitation is 560-640 mm [

20]. The terrain of the area is generally gentle hilly, with elevations ranging from 90 to 320, averaging 174 m a.s.l., and an average slope of 2.06° (0-30.9°). According to the geobotanical zoning delimitation, the study area is located in the boreal-nemoral forest zone, in the southeast passing into nemoral forest and further into the forest-steppe zone, where agricultural lands occupy most of the territory [

21].

The test relevés are located within the Smolensk-Moscow Upland (

Figure 1). Here the proportion of spruce forests is maximum and equal to 38%. The territory is located on upland with underlying rocks of moraine, moraine-water-glacial and lake-water-glacial loamy, sandy loam and sandy sediments. Soils are sod-podzolic. Mesophitic communities of automorphic terrain positions in the watershed were studied.

2.2. Data Acquisition

The research was conducted in the territory of strict scientific forest reserves with official conservation status. Primary 70 vegetation relevés were carried out in the 1980s (I data set) (

Figure 1). At that times it was intact closed old-growth forests with spruce dominance (

Picea abies) and admixture of lime (

Tilia cordata), oak (

Quercus robur), maple (

Acer platanoides) and other species, with predominant stand age of 80-100 years. The studied communities belonged predominantly to the Querco-Fagetea class, although many vegetation types were on the border between the Querco-Fagetea and the Vaccinio-Piceetea [

22]. All relevés were resurveyed at the same sites in 2024-2025 (II data set).

In order to confirm the natural origin of these forest areas, we analyzed historical maps of the XIX century [

23,

24,

25] and aerial photographs of the 1960-80s.

Geographic coordinates for II d.s. relevés were determined by georeferencing old forest maps from 1980-s using the actual forestry GIS data. The current state of the forest stands (when planning the relevés for repeated surveys) was monitored using high resolution satellite imagery, including Google Earth data. The relevés were carried out within plant communities, homogeneous in terms of general floristic composition, composition of dominants of each layer, community structure and habitat conditions, on an area of 400 square meters using standard data entry forms [

26], according to standards of "European vegetation survey" [

27] and the European Vegetation Archive database. The composition and structure of the canopy, including projected crown cover, average height of adult trees, and understory, were assessed. The complete species composition of the shrub, herb-dwarf shrub and moss layers was determined, and the percent projective cover (PC) was estimated. Elevation data for relevés were obtained from topographic maps and GPS data. Plant names of vascular species are given according to [

28], mosses according to [

29].

2.3. Data Analysis

Changes in all vegetation layers were analyzed by comparing data obtained after 40 years. The following abbreviations were used for different layers: A – tree layer, B – understorey of trees (B1) and shrubs (B2) (1-10 m high), C – herb-dwarf shrubs layer (below 1 m), D – moss layer.

Species dynamics were assessed by calculating the mean PC value, including null values. The significance of changes in community species composition and abundance were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test, which is appropriate when the sample size is small and does not follow a normal distribution. Linear relationship of PC of main forest-forming species was evaluated by Spearman's criterion. Correlation of PCs of species of all tiers in communities in different years of research was performed using gamma correlation. Statistica 12 software was used. The sample size (n) for all species was 70, including the sites where species were absent.

The consequences of structural disturbances in communities were manifested in the change of functional groups of plants united by similarity of response to changes in ecological and cenotic environmental conditions. Such indicators as the composition of ecological and cenotic groups (ECG) and species activity (A) used for generalized relevés of plant communities, their classification and successional status. The assignment of species to ECGs was performed according to the modified method [

31], including diagnostic species for the compared community groups in the Brown-Blanquet approach [

32]. The following groups were distinguished: Br (boreal, including boreal shrubs, boreal small herbs and species of boreal green mosses), Nm (nemoral broadleaved herbs, including species of mosses of nemoral communities), NW (nitrophilic-wet), Md (meadow), Eg (edge-herb), Ad (adventive). Meadow and edge groups are rare and are usually considered together as meadow-edge groups.

The functional significance of species was assessed in terms of the composition of all community layers using the species activity index (A) [

33]:

where

F is the relative occurrence of the species at all sites in the set of relevés,

D is the average value of species abundance (%) for the sites where the species was recorded. Sites where the species was present were considered. Prospects for spruce regeneration were assessed by the dynamics of abundance of tree and shrub species present at different stages of the study.

Classification of relevés was carried out using the ecological-phytocoenotic approach [

34]. Community types were distinguished based on the representation of ecological-phytocenotic groups (ECGs) of species of subordinate layers and the dominant tree species.

To interpret the ecological content of the species composition of communities in different time periods (I and II d.s.), we used indirect ordination methods - non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS ordination) in the R software. The differentiation of the community groups was studied based on the composition and abundance of species of the main layers in different combinations. Indirect ordination method allowed us to visualize the differences between communities in terms of environmental gradients. In the ordination and interpretation of the axes, for each relevés its point values in Ellenberg scales were evaluated. The indicator values for light (L), soil mineral nitrogen richness (N), soil reaction (R), and soil moisture (M) using the full list of species and weighted by species cover were calculated in the Juice 7 software [

35,

36]. Correlation of ordination axes with ecological characteristics of relevés was displayed by means of length and direction of vectors of ecological factors, as well as the degree of their correlation with the axes. In this way, the values of factors for each point were obtained when assessing the distribution of forest communities in the ecological space in different years of research.

3. Results

Review of historical cartographic materials indicated that 69% of the studied forest reserves had been forested for at least 300 years, on 28% of relevés the forest emerged about 250 years ago, and only 3% of relevés forests were less than 200 years old. Remote sensing data from the 1960s and 1980s confirmed the absence of significant disturbance after 1945.

3.1. Changes in Structural and Functional Properties in Spruce Forests

Changes in the general patterns of spruce communities structure over the 40-year period consisted in the disruption of stand layer structure of the stand, changes in the species composition of forest-forming species of the tree and shrub layer (Appendix B

Figure 1a,b,c,d,e,f). Redistribution of the abundance of plants forming the main structural layers of spruce communities is evident (

Figure 2). It is noticeable that the cover of the tree layer (A) decreased by 2.5 times, and this indicator increased twofold or more for plants both in the understory (B1) and shrub (B2) layers. Less significant changes are observed in the cover value of lower layers plants (C and D). All differences in layers A, B1, B2 , D and C were significant (p<0.05) (

Table 1).

The typological composition of spruce forests has also changed (

Figure 3a). The disintegration of the tree layer in spruce forests caused a change in the ratio of community types. 5 types of community were identified in I d.s.; the number types increased to 8 types in II d.s. The main difference is the increase in typological diversity, including the appearance of two new types of communities – with disintegrated trees layers (7 and 8) instead of mainly nemoral spruce forests (2). In the first case, the main layer of the stand of the boreal type of spruce stands (1) was replaced by active regeneration of spruce (7), while in the second case, the main layer of the nemoral type of spruce stands (2) was replaced by hazel (

Corylus avellana) under a canopy of lime (

Tilia cordata) and maple (

Acer platanoides). The majority of relevés in the repeated records fall into the last class (8) (

Figure 3).

The more detailed composition of tree layer and diagnostic species of herb-dwarf shrubs and moss layers for the identified forest types are given below (

Table 2).

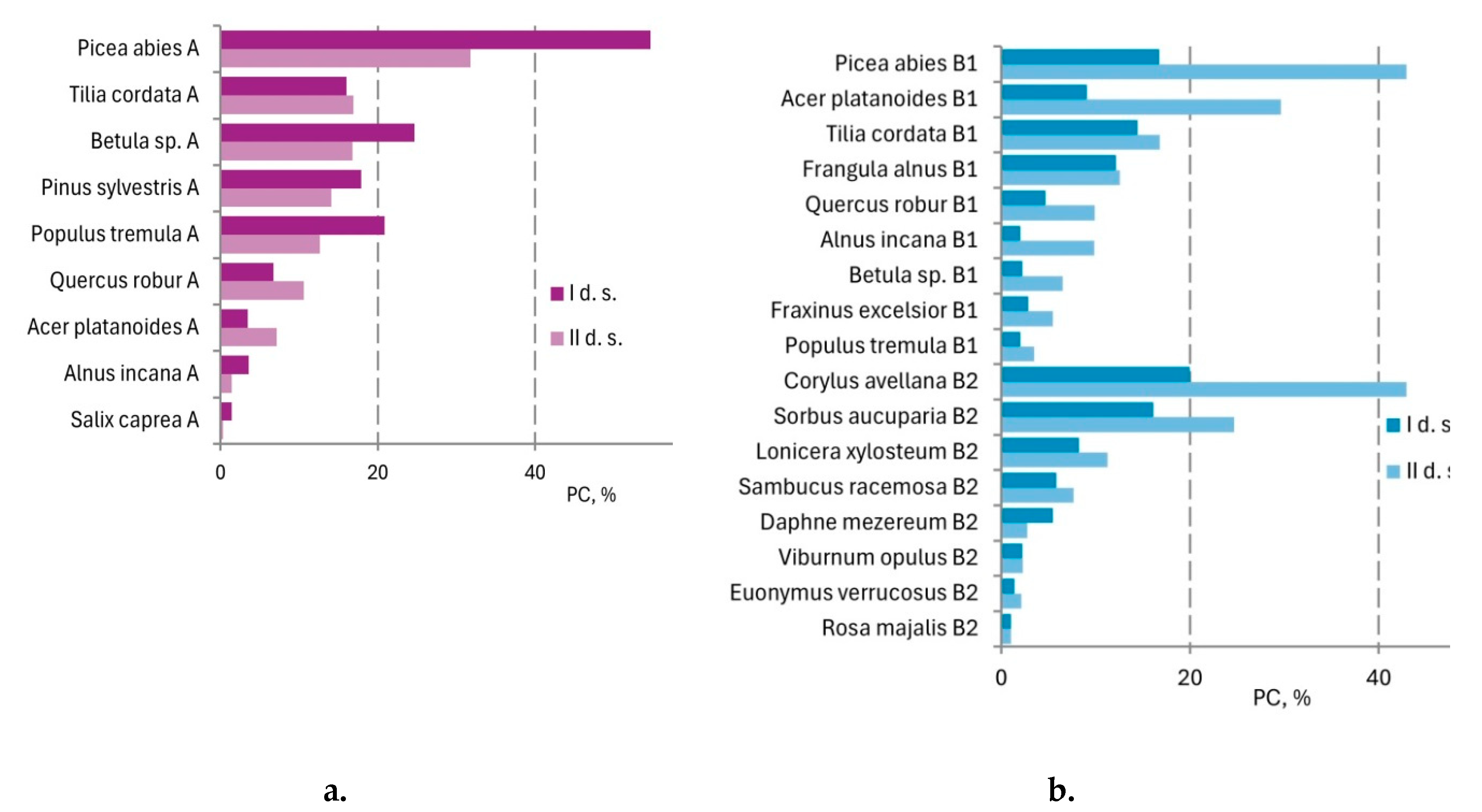

3.2. Changes in Common Patterns of Tree and Shrub Layers

Let us consider in more detail the main changes in the tree and shrub layers that determine the redistribution of habitat-forming conditions (light, moisture and nutrients) for plants of lower levels. When comparing the composition and structure of vegetation of the upper layers of communities after 40 years, drastic changes are noticeable. The main changes are the decrease in the tree layer cover, dominated by

Picea abies, and the increase in the shrub layer cover, dominated by

Corylus avellana and

Sorbus aucuparia (

Figure 2). At the same time, the decrease in the total cover of the tree layer was not only due to the loss of

Picea abies, but also due to the loss of trees of such species as

Betula sp.,

Populus tremula,

Pinus sylvestris. In contrast, the participation of

Quercus robur has slightly increased.

More detailed data on the dynamics of PC for all tree species of the upper layer (except for species with less than 0.1% cover) are presented in

Table 3. In addition to a 2.5-fold decrease in spruce cover, there is a significant decrease in PC by about 5-fold in

Betula sp. and disappearance of

Alnus incana. The loss of these species is a natural process associated with overmatures age (100 years and more).

In contrast to the tree layer, the cover of almost all understorey species tends to increase (

Table 4). As follows from the table, the understorey of trees in mature spruce forests in I d.s. was insignificantly and irregularly represented. Therefore, in most cases the differences are not reliable. In I d.s.

Picea abies understorey was in the first place (with 4.0% coverage),

Tilia cordata and

Acer platanoides were represented in smaller quantities (2.97 and 1.17% respectively), and the participation of other species was almost imperceptible. In II d.s.,

Picea abies understorey had more than a 3-fold increase in PC (differences significant), indicating potentially successful regeneration of this species in place of decayed stands. The participation of

Acer platanoides (significant differences) and

Quercus robur increased to an even greater extent, which may allow the formation of spruce-broadleaved stands in the future. Active regeneration of

Picea abies understorey indicates demutational process as a form of secondary succession.

The shrub layer, as follows from

Table 5, was insignificantly represented in old-growth spruce forests. The predominant species (in descending order) were

Corylus avellana,

Sambucus racemosa, Sorbus aucuparia and

Frangula alnus; the participation of other species was almost imperceptible. The most important result of structural changes in the shrub layer is the fact of the strongest development of

Corylus avellana, the coverage of which increased fivefold (from 5.7 to 26.36%) and in some communities reached 80-90%. In fact, in many cases hazel shrub communities with woody undergrowth were formed in place of old-growth spruce forests. There is a tendency to increase participation of ash (

Sorbus aucuparia) and (slightly) elderberry (

Sambucus racemosa). Other species under the overgrown hazel (

Corylus avellana) canopy have decreased their participation. Active development of the understorey of shrub species (mainly

Corylus avellana and

Sorbus aucuparia) characterizes another type of secondary succession.

Structural reorganization of the tree and subcanopy layer systems was reflected in functional indices in communities over the study period. The species activity index (

A) of

Picea abies in the main layer was reduced by almost half, while

Betula sp.,

Pinus sylvestris and

Populus tremula decreased to a lesser extent. At the same time, the activity index of

Tilia cordata and

Acer platanoides has increased (

Figure 4a). Significant changes were observed in the understorey layer of trees -

Picea abies undergrowth increased more than 2 times,

Acer platanoides - 3 times. In the shrub layer, the activity index of

Corylus avellana increased more than 2 times, to a lesser extent

Sorbus aucuparia and

Lonicera xylosteum (

Table 4b).

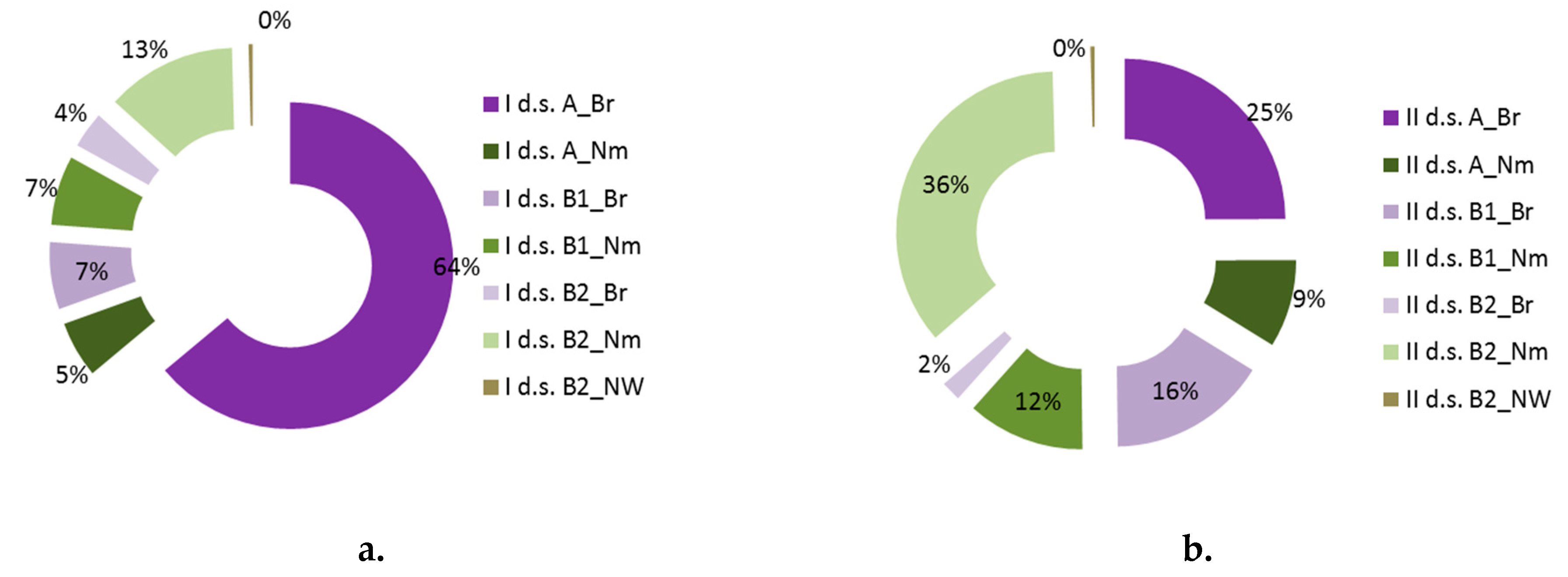

The affiliation of species to certain ECGs makes it possible to assess changes in the ratio of the total number of species of communities by main groups - boreal and nemoral. Thus, the share of boreal species coverage in the main tree layer (A) decreased by 2.5 times, and the coverage of the nemoral spectrum increased by 1.5 times. The coverage of species of the boreal spectrum in the undergrowth layer (B1) increased by more than 2 times, the coverage of the nemoral spectrum also changed slightly. In the shrub layer (B2) - significant reductions in boreal species and an even greater increase (in 3 times) in the nemoral species (

Figure 5a, b). All mentioned changes are significant at р<0.05.

The assessment of phytocenotic links, calculated based on gamma-correlation of abundance of the main forest forming species in communities for two time periods, demonstrated different degrees of interdependence (Table A1).

The highest positive relationship is for Tilia cordata and Pinus sylvestris (r=0.85, r=0.81), negative correlation - for Picea abies (r=-0,44) between the study period I d.s. and II d.s. in the tree layer.

PC of Picea abies in the main layer in II d.s. has a negative correlation with I d.s. values, indicating a reliable change in the distribution of the main forest-forming species at the observation points, while the PC of associated species remained positively correlated over the study period. This indicates that PC of Corylus avellana and especially Acer platanoides in II d.s. were determined by the values for the previous measurement period. On the contrary, the results of comparison of Picea abies in main layer cover between the indicators of I d.s. and II d.s. showed their relative independence, and the strong disturbance of the spruce mother layer confirms again cardinal transformations in the structure of communities.

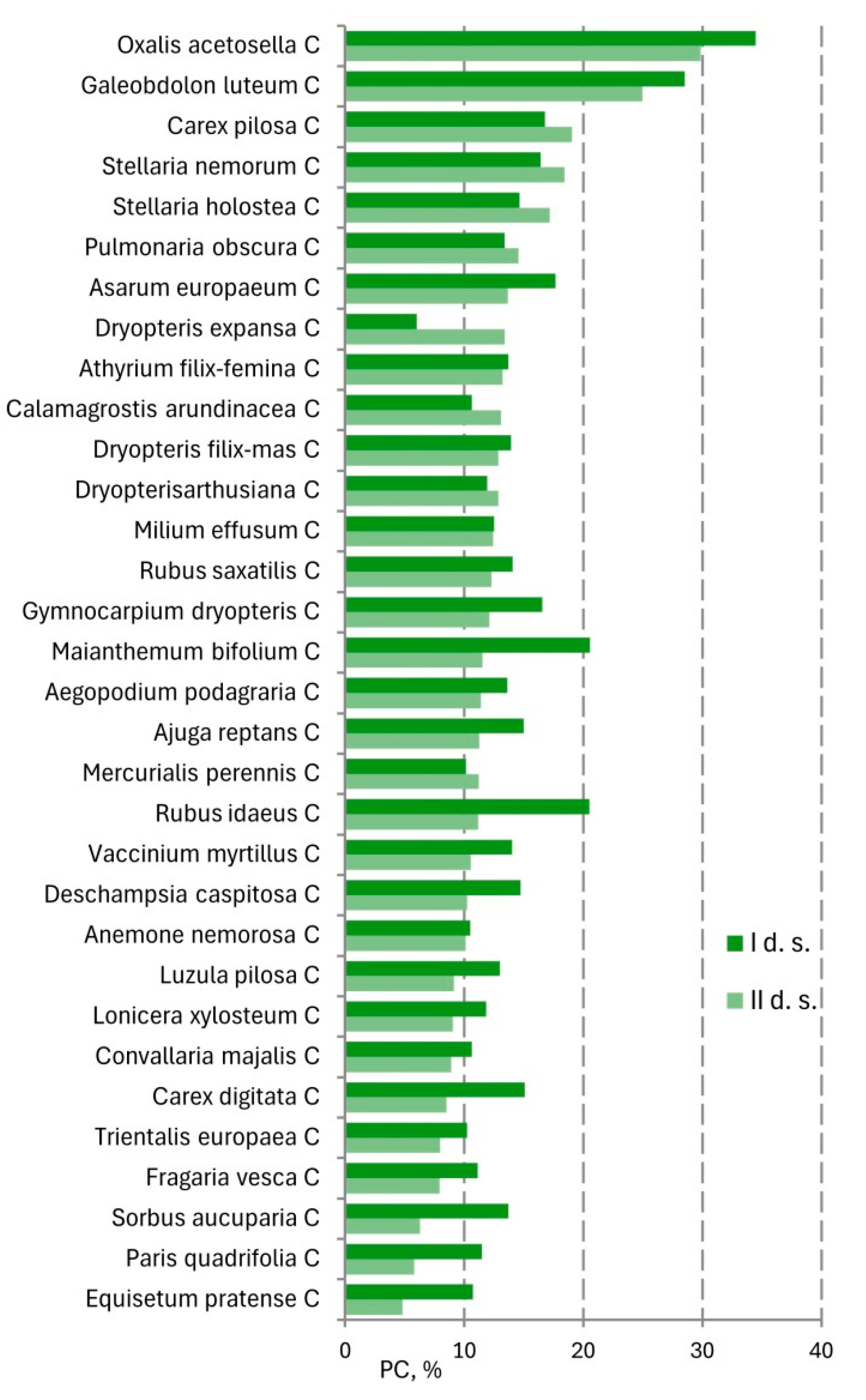

3.3. Changes in Common Patterns in Field and Ground Layers

Assessment of the transformation of the species composition of the ground layer vegetation according to the species activity index (

A) did not reveal any drastic changes. The changes were mostly related to the redistribution of species abundance while maintaining the general composition of species (

Figure 6).

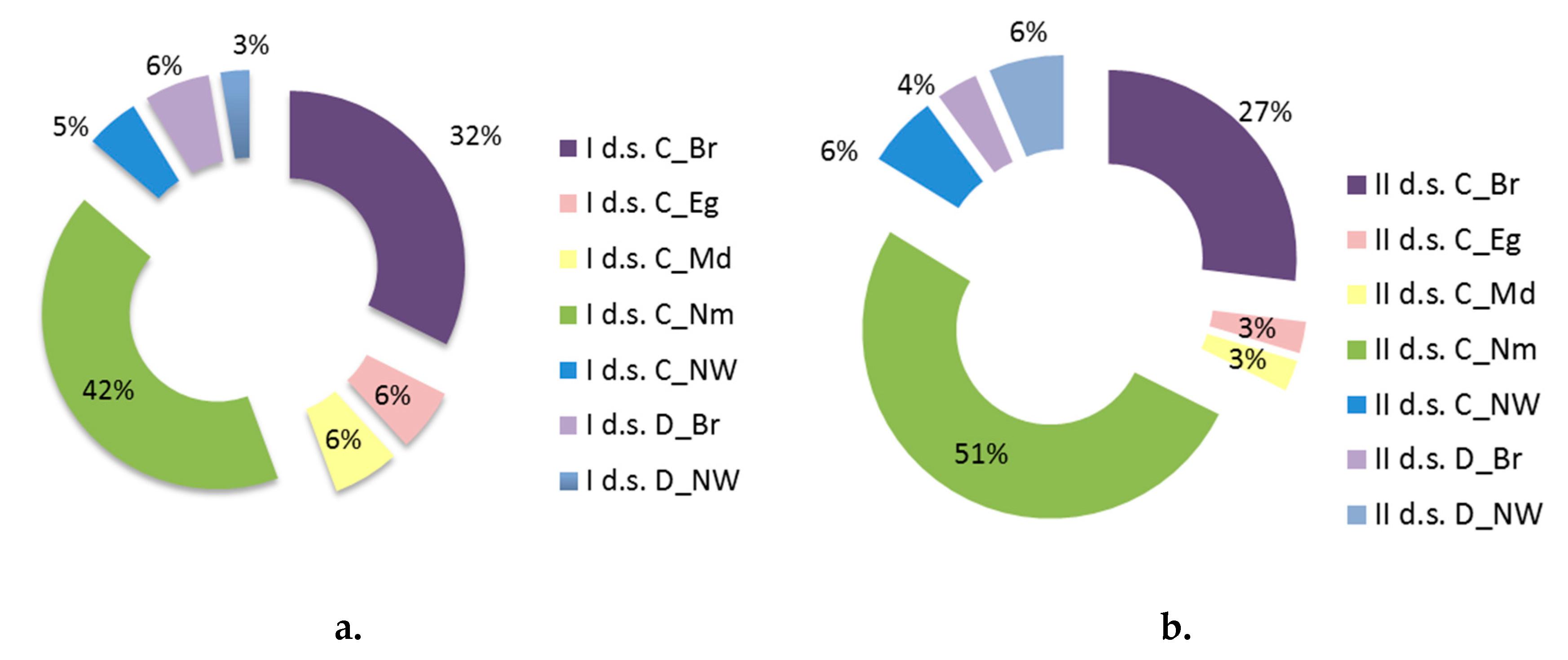

A restructuring was also observed in the ecological-phytocoenotic structure of ground layer species (

Figure 7). There was the slight significant (р<0.05) decrease in the proportion of boreal vascular species and the slight increase in the nemoral spectrum, as well as a decrease in edge-herb (Eg) and meadow (Md) species in the herbaceous cover. Significant differences were observed in boreal (Br) spectrum and in edge-herb (Eg) of the moss layer.

3.4. Relationship with Environmental Factors

To reveal the specific features of spruce community organization, their relationship with external environmental factors, in particular, terrain conditions, was assessed. Based on the absolute elevation data of the relevés, a gamma correlation between the indicators of forest forming species closeness and absolute height, slope and curvature of the slopes were calculated. It was found that for both study periods height was similarly related to stand indices - a significant positive correlation with absolute height was observed for Corylus avellana (r =0.49 in I d.s., r =0.35 in II d.s.) and Acer platanoides in undergrowth (r =0.31 in I d.s., r =0.35 in II d.s.), negative - for Pinus sylvestris (r =-0.33 in in I d.s., r =-0.29 II d.s.) and Picea abies in undergrowth (r =-0.32 in I d.s., r = -0.36 in II d.s.). No significant relationship was found between species abundance and slope and curvature.

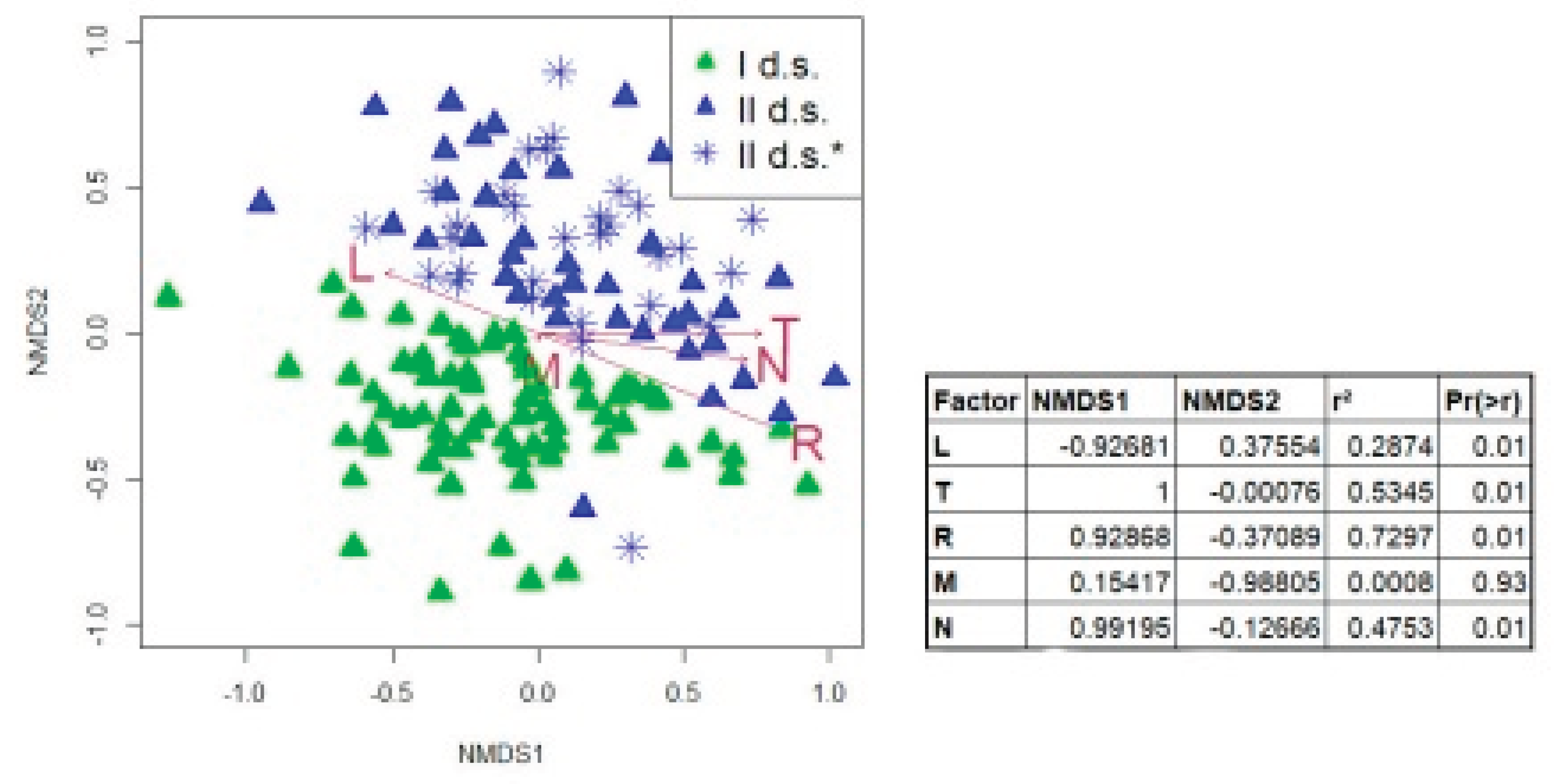

Changes in ecological conditions of habitats were assessed by linking communities of different periods of relevés to biotopic factors expressed through the composition of species in spruce communities using Ellenberg ecological values. The assessment was performed by interpreting the distribution of relevés in ordination axis space based on non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS ordination). Study of the complete species composition of spruce forests recorded at different time periods revealed changed habitat conditions. Changes in light (L), temperature (T), soil reaction (R) and soil nitrogen (N) factors were associated with the first axis of variation (NMDS1). With the second axis (NMDS2) - changes in moisture content (M) and to a lesser extent soil reaction (R). The magnitude of correlation of vectors of environmental factors with ordination axes and values of correlation coefficient square (r

2) are high enough, which indicates a significant change in the values of environmental factors for the studied time interval. In general, the gradient of displacement of the set of points in II d.s. indicated a tendency of maximum increase in the values of temperature and decrease in soil reaction, contributing to the formation of a nemoral spectrum of species. Soil illumination and moisture content were relatively “weak” factors (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

There are many cases of transformations of community composition and structure in the course of community dynamics in the literature, in which typical mosaic-cyclic processes have been described [

37,

38,

39]. Strong winds tend to act as the main disturbance type in European temperate forests. This leads to small-scale episodic disturbances [

40,

41], where disturbed areas are usually reforested by highly competitive, shade-tolerant climax tree species. Оutbreaks of the bark beetle

Ips typographus often occurre after large windthrow events in Western Europe [

42]. Mass spruce dieback in the forests of Central Russia was preceded by unfavorable climatic conditions (droughts) during the vegetation period [

43,

44], which weakened trees and reduced their ability to resist pests and diseases [

45,

46]. Observations of spontaneous dynamics of spruce forest communities in the Central Forest Reserve confirmed a similar tendency of dieback within 1-2 years as a result of recurrent meteorological anomalies, further weakening of trees and insect pest outbreaks [

47].

Our study recorded drastic changes in spruce communities within the center of East European Plain that occurred over a period of 40 years and confirmed our assumptions. The restructuring in mature communities of natural origin is associated with the peculiarities of formation of cenopopulations of tree species. The tree layer in mature communities is characterized by a gradual decrease in PC from the upper to the lower layers and mutual oppression of trees of younger generations. Phytocenotic significance of interaction as differentiation factor and high competition for environmental factors (light, moisture, soil nutrients) was investigated in other studies [

48,

49,

50]. In trees of older generations, the significance of phytocenotic factors is inferior to environmental factors, in particular, hurricane winds or sharp fluctuations in the water table. Therefore, the impact of extreme factors turns out to be the most dangerous for the largest trees of older generations [

51]. In our case, such dramatic changes reflect the fact of complete or partial mortality of the mother spruce stand, including as a result of mass outbreaks of bark beetle in 1999-2003 and 2010-2013.

Two directions of secondary succession were recorded after the collapse of the mother spruce stand: 1) with restoration of

Picea abies undergrowth and 2) with active development of shrubs (

Corylus avellana and

Sorbus aucuparia) and broad-leaved undergrowth. Analysis of sensitivity of forest-forming species to environmental conditions was used in study of successional direction. In our study we observed a significant relationship of

Picea abies,

Acer platanoides, and

Corylus avellana undergrowth with morphometric indicators of terrain. This is consistent with other data – boreal spruce forests are typical for flat terrain. While nemoral (complex) spruce forests with participation of broad-leaved tree species are typical for convex moraine watershed plateaus [

52].

It has been established that the mean annual temperature has increased over 40 years by 2

o C [

53]. For spruce forests at their southern limit of distribution, such warming corresponds to a shift in the vegetation period isotherms by about 150 km to the south [

54]. This leads to a transformation of the formational composition of forests

. Indeed, in our study typological diversity of the studied communities increased after 40 years not only due to the loss of the tree layer and the formation of new “non-forest” community types, but also due to the transition of a part of mixed spruce-broadleaf communities to broadleaf communities, and of pine-spruce communities of the boreal type to the nemoral type. Analysis of the complete species composition of spruce forests and the ratio of species of different ECGs confirmed the general nemoralization of the composition - while the species composition as a whole remained the same, the abundance of boreal-type species in all structural layers decreased, while the abundance of nemoral species increased. The gradient of the shift of the set of modern relevés in the ecological space indicated a tendency of increasing values of temperature and decreasing soil acidity, which contributed to the formation of a nemoral spectrum of species. The increase in the proportion of nemoral species in the forests of the Moscow region has been noted already since the 1990s in other studies [

55].

In this case, it is difficult to separate the interrelated effects of natural succession and climate warming, as soil enrichment and increased availability of nutrients favoring the development of the nemoral plant spectrum occur in both cases. There is evidence that complex patterns of change in species biodiversity are also observed when combining factors of abandonment of traditional management in Czech plant communities and in association with increased litter accumulation [

56,

57]. Both processes support stronger competitors and likely contribute to the co-evolution of vegetation [

58]. In addition, climate warming may extend the growing season, contribute to biomass increases and alter successional processes [

59,

60]. The results of the study of oak stands in Poland revealed different effects of an increase in air temperature by 1°C on the two oak species (slowing down the growth of

Quercus robur, but improving the growth of

Q. petraea) [

61]. This indicates different responses of species to changing environmental conditions.

It should also be considered that the mechanisms of intra- and interspecific competition are important driving forces in the feedback loop of the structure and functioning of the stand [

62,

63]. Analysis of interspecific relationships in the composition of tree species in the upper and subordinate layers (undergrowth and shrubs) demonstrated significant relationships that predetermine the likely course of development of spruce communities. Thus, on the one hand, a significant positive relationship was observed between different generations of tree (

Acer platanoides,

Quercus robur and

Pinus sylvestris) and shrub (

Corylus avellana) species at different study times, on the other hand, a negative correlation was noted between the abundance of

Picea abies in the upper layer in I d.s. and II d.s. At the same time, the active development of young trees of

Acer platanoides in the undercanopy space of the main layer is currently negatively associated with the formation of

Picea abies of undergrowth, but positively with

Populus tremula in the upper layer. Ecological features of the species, primarily the illumination factor, explain this picture. At whole the dynamics of correlation links indicate changes in the structure and interactions between species of the ecosystem between two study periods. Strengthening of positive links may indicate closer cooperation or joint response of species to environmental conditions in the process of successional dynamics. Whereas the emergence of negative links indicates competition or division of resources.

Considering the life cycles of vegetation (10-20 years for the shrub layer with understorey and 40 years for the tree layer [

64], we can assume that if the protected status is maintained, over the next 40-60 years the composition of spruce forests will approach coniferous-broadleaved forests, and the latter will transition to broadleaved forests. This rate of transition of successional stages is close to the pattern of forest succession in a number of spruce and mixed (with undergrowth of

Quercus robur, Tilia cordata and

Picea abies) communities in the south of the Moscow region [

65]. An assessment of coniferous forest dynamics in the Moscow region based on historical Landsat images in the period from 1990 to 2020 showed that the area of spruce forests of natural and artificial origin decreased from 19.6 to 7% [

66]. Thus, the total area and composition of spruce forests in the region will decrease in the future due to direct loss of spruce in mature stands of both artificial and natural origin, and subsequent transition to mixed forests.

5. Conclusions

The presence of mature forests of natural origin in the Smolensk-Moscow Upland is a unique opportunity to study the peculiarities of autogenous successional dynamics of zonal forests. In this study we considered disturbances in the structural and functional organization of old-growth spruce forests over the last four decades, caused by the dieback of upper canopy trees. The initiation of this type of disturbance was a general increase in temperatures and especially extreme droughts provoking weakening of spruce stands and invasions of insect pests. Restoration of mixed and broad-leaved communities through active development of Corylus avellana and Acer platanoides undergrowth in higher elevation positions with better drainage was more common. The development of young generation of Picea abies in canopy windows with subsequent restoration of boreal-type spruce forests was observed in flat terrain forms. In general, there was an undoubted trend of nemoralization of plant species composition, confirmed by quantitative assessment of the shift of biotopic characteristics towards an increase in average temperature, decrease in soil acidity and increase in soil fertility.

In the next 40-60 years, in the absence of additional forestry measures (silviculture and thinning) in the Moscow region, as well as in the center of East European Plain, Picea abies is expected to be present as a companion species in mixed stands with a complete loss of “pure” spruce forests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization T.Ch.; methodology T.Ch., and A.M.; validation T.Ch., N.B. and I.K.; formal analysis T.Ch., I.K., and N.B.; conducted the fieldwork T.Ch., A.N., A.M., A.T., N.P. and N.B.; resources T.Ch., and I.K.; data curation T.Ch., N.B. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation T.Ch.; visuali-zation T.Ch., and I.K.; supervision T.Ch.; project administration T.Ch. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The core of this research was conducted as part of RSF project (№ 24-17-00120) (field research, analytical work, statistical data analysis). The research was conducted as part of the State Assignment of the IG RAS (FMWS-2024-0007) (synthesis of materials from previous and modern research).

Data Availability Statement

Research data can be obtained from corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECG |

Ecological and cenotic group |

| Br |

Boreal |

| PC |

Projective cover |

| Nm |

Nemoral |

| NW |

Nitrophilic-wet |

| Md |

Meadow |

| Eg |

Edge-herb |

| Ad |

Adventive |

| NMDS |

Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| L |

Light |

| N |

Nitrogen richness |

| R |

Soil reaction |

| M |

Soil moisture |

| d.s. |

data set |

References

- Jandt, U.; Bruelheide, H.; Jansen, F.; Bonn, A.; Grescho, V.; Klenke, R.A.; Sabatini, F.M.; Bernhardt-Römermann, M.; Blüml, V.; Dengler, J.; et al. More Losses than Gains during One Century of Plant Biodiversity Change in Germany. Nature 2022, 611, 512–518. [CrossRef]

- Bolam, F. Over Half of Threatened Species Require Targeted Recovery Actions to Avert Human-induced Extinction. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2023, 22, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ameca, E.I.; Otero-Jimenez, B.; Montaño, S.K.; Shea, A.; Kelly, T.; Andrianoely, D.; Wright, P.C. Human-Induced Deforestation Increases Extinction Risk Faster than Climate Pressures: Evidence from Long-Term Monitoring of the Globally Endangered Milne-Edward’s Sifaka. Biological Conservation 2022, 274, 109716.

- Dimitrova, A.; Csilléry, K.; Klisz, M.; Lévesque, M.; Heinrichs, S.; Cailleret, M.; Andivia, E.; Madsen, P.; Böhenius, H.; Cvjetkovic, B.; et al. Risks, Benefits, and Knowledge Gaps of Non-Native Tree Species in Europe. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 908464. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C.; Antill, E.C.; Kreft, H. All Is Not Loss: Plant Biodiversity in the Anthropocene. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e30535. [CrossRef]

- Klinkovská, K.; Sperandii, M.G.; Knollová, I.; Danihelka, J.; Hájek, M.; Hájková, P.; Hroudová, Z.; Jiroušek, M.; Lepš, J.; Navrátilová, J.; et al. Half a Century of Temperate Non-Forest Vegetation Changes: No Net Loss in Species Richness, but Considerable Shifts in Taxonomic and Functional Composition. Glob Chang Biol 2025, 31, e70030. [CrossRef]

- Pakeman, R.J.; Lepš, J.; Kleyer, M.; Lavorel, S.; Garnier, E.; the VISTA consortium Relative Climatic, Edaphic and Management Controls of Plant Functional Trait Signatures. J Vegetation Science 2009, 20, 148–159. [CrossRef]

- Martinez del Castillo, E.; Zang, C.; Buras, A.; Hacket-Pain, A.; Esper, J.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Hartl, C.; Weigel, R.; Klesse, S.; Resco de Dios, V.; et al. Climate-Change-Driven Growth Decline of European Beech Forests. Communications Biology 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Viljur, M.-L.; Abella, S.; Adámek, M.; Alencar, J.; Barber, N.; Beudert, B.; Burkle, L.; Cagnolo, L.; Campos, B.; Chao, A.; et al. The Effect of Natural Disturbances on Forest Biodiversity: An Ecological Synthesis. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 2022, 97, 1930–1947. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J. Functional Redundancy in Ecology and Conservation. Oikos 2002, 98.

-

Functional Plant Ecology; 2nd Edition; edited by Francisco Pugnaire and Fernando Valladares.; Taylor & Francis Group, 2007;

- Nock, C.; Vogt, R.; Beisner, B. Functional Traits. In; 2016 ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- Vasilevich, V. Functional diversity in plant communities. Botanical Journal 2016, 101, 776–795. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.P.; Olff, H.; Willems, J.H.; Zobel, M. Why Do We Need Permanent Plots in the Study of Long-Term Vegetation Dynamics? Journal of Vegetation Science 1996, 7, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Chytry, M.; Tichý, L.; Hennekens, S.; Schaminée, J. Assessing Vegetation Change Using Vegetation-Plot Databases: A Risky Business. Applied Vegetation Science 2014, 17. [CrossRef]

- Kapfer, J.; Hédl, R.; Jurasinski, G.; Kopecký, M.; Schei, F.H.; Grytnes, J.-A. Resurveying Historical Vegetation Data - Opportunities and Challenges. Appl Veg Sci 2016, 20, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Kneeshaw, D.; Gauthier, S. Old Growth in the Boreal Forest: A Dynamic Perspective at the Stand and Landscape Level | Request PDF. Environmental Reviews 2003, 11, 99–114. [CrossRef]

- Mosseler, A.; Thompson, I.; Pendrel, B. Overview of Old-Growth Forests in Canada from a Science Perspective. Environmental Reviews 2011, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.; Condit, R.; Crawley, M.; Pacala, S.; Tilman, D. Long-Term Studies of Vegetation Dynamics. Science 2001, 293, 650–655. [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, L.; Kalinina, A. Territorial Distribution of Precipitation in the Moscow Region in the Presence and Absence of the Large Anthropogenic Formation. Ecology of Urban Areas 2018.

- Hytteborn, H.; Maslov, A.A.; Nazimova, D.I.; Rysin, L.P. Boreal Forests of Eurasia. In Coniferous forests; etc.: Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2005; pp. 23–99.

- Maslov, A. Monitoring biodiversity and natural dynamics processes in protected forest areas: program and results of work over 25 years. In Structure and functions of forests in European Russia; Scientific Publications Association KMK: Moscow, 2009; pp. 172–190 ISBN 978-5-87317-585-7.

- Plans of the Russian Empire Land Survey 1777.

- Three-Verst Military Topographic Map of the Russian Empire 1850.

- Topographic military maps of Red Army (RKKA) 1936.

- Mirkin, B. Theoretical basis of modern phytocenology; Nauka.; USSR Academy of Sciences, Bashkir branch, Institute of Biology: Moscow, 1985;

- Rodwell, J.S.; Mucina, L.; Pignatti, S.; Schaminée, J.H.J.; Chytry, M. European Vegetation Survey; the Context of the Case Studies. Folia geobotanica et phytotaxonomica 1997, 32, 113–115.

- Moore, D.M. Flora Europaea Check-List and Chromosome Index; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge., 1982;

- Ignatov, M.; Ignatova, E. Moss Flora of the Middle Eropean Russia; KMK: Moscow, 2003; Vol. 1; ISBN 5-87317-149-1.

- Maslov, A. Biodiversity of the Native Forest Types in Strict Scientific Forest Reserves of the Moscow Region. Russian journal of forest science 2022, 631–342. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, V.; Khanina, L.; Bobrovsky, M. Validation of the ecological-coenotical groups of vascular plant species for European Russian forests on the basis of ecological indicator values, vegetation releves and statistical analysis. Bulletin of Moscow Society of Naturalists 2006, 111, 36–47.

- Mucina, L.; Grabherr, G.; Wallnöfer, S. Die Pflanzengesellschaften Österrreichs. Teil III; Wälder und Gebüsche: Jena, 1993;

- Malyshev, L. Floristic Zoning Based on Quantitative Characteristics. Botanical Journal 1973, 1581–1588.

- Chernenkova, T.V.; Kotlov, I.P.; Belyaeva, N.G.; Suslova, E.G.; Morozova, O.V. Assessment and mapping of the cenotic diversity of the Moscow region’s forest. Russian Journal of Forest Science (Lesovedenie) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tichý, L. JUICE, Software for Vegetation Classification. Journal of Vegetation Science 2002, 13, 451–453. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team 2020.

- Remmert, H. The Mosaic-Cycle Concept of Ecosystems — An Overview. In The Mosaic-Cycle Concept of Ecosystems; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp. 1–21 ISBN 978-3-642-75650-4.

- Král, K.; Vrška, T.; Hort, L.; Adam, D.; Šamonil, P. Developmental Phases in a Temperate Natural Spruce-Fir-Beech Forest: Determination by a Supervised Classification Method. Eur J Forest Res 2010, 129, 339–351. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, D.; Pretzsch, H. Reactions to Gap Emergence: Norway Spruce Increases Growth While European Beech Features Horizontal Space Occupation–Evidence by Repeated 3D TLS Measurements. Silva Fennica 2017, 51.

- Neal, J.; Hawker, L. FABDEM V1-2 2023.

- Šamonil, P.; Schaetzl, R.J.; Valtera, M.; Goliáš, V.; Baldrian, P.; Vašíčková, I.; Adam, D.; Janík, D.; Hort, L. Crossdating of Disturbances by Tree Uprooting: Can Treethrow Microtopography Persist for 6000 Years? Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 307, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Schelhaas, M.; Nabuurs, G.; Schuck, A. Natural Disturbances in the European Forests in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Global Change Biology 2003, 9, 1620–1633. [CrossRef]

- Maslov, A. BARK BEETLE AND DRYING OUT OF SPRUCE FORESTS; FBU VNIILM: Moscow, 2010; ISBN 978-5-94219-170-2.

- Korotkov, S.A. Change in the Composition of Tree Stands and the Stability of Protective Forests in the Central Part of the Russian Plain; Moscow, 2023;

- Malakhova, E.; Lyamtsev, N. Extent and Structure of Moscow Region Spruce Forest Dieback in 2010-2012. Izvestia Sankt-Peterburgskoj lesotehniceskoj akademii 2014, 193–201.

- Maslov, A.; Komarova, I.; Kotov, A. The Dynamics of Reproduction of Bark Beetles in Central Russia in 2010-2013. And the Forecast for 2014. Forestry information 2014, 38–46.

- Pugachevsky, A. Spruce coenopopulations. Structure, dynamics, regulatory factors; Nauka i Tekhika.; Minsk, 1992; ISBN 5-343-00783-X.

- Purves, D.W.; Lichstein, J.W.; Pacala, S.W. Crown Plasticity and Competition for Canopy Space: A New Spatially Implicit Model Parameterized for 250 North American Tree Species. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e870. [CrossRef]

- Karpov, V. Experimental Phytocenology of Taiga; Nauka.; Leningrad Department: Leningrad, 1969;

- Alekseev, V. Light Regime of the Forest; Nauka.; Leningrad, 1975;

- Dyrenkov, S. Structure and dynamics of taiga spruce forests; Nauka: Leningrad, 1984;

- Rysin, L.; Savelyeva, L. Cadastres of forest types and forest biogeocenoses; Scientific publications partnership KMK: Moscow, 2007; ISBN 978-5-87317-397-6.

-

Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Its Consequences in the Russian Federation; Наукoемкие технoлoгии.; Saint Petersburg, 2022;

- Kobyakov, K.; Titova, S.; Shmatkov, N.; Korotkov, V.; Kazakov, P. Assessment of Possibilities for Increasing Greenhouse Gas Absorption by Forests in the Central European Russia. Sustainable forest management 2019, 4–20.

- Maslov, A.A. Dynamics of Ecological Species Groups and Forest Types during Natural Successions in Central Russia Preserved Forests. Bulletin of Moscow Society of Naturalists. Biological series 1998, 103, 34–43.

- Enyedi, Z.M.; Ruprecht, E.; Deák, M. Long-term Effects of the Abandonment of Grazing on Steppe-like Grasslands. Applied Vegetation Science 2008, 11, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Ruprecht, E.; Enyedi, M.Z.; Eckstein, R.L.; Donath, T.W. Restorative Removal of Plant Litter and Vegetation 40 Years after Abandonment Enhances Re-Emergence of Steppe Grassland Vegetation. Biological Conservation 2010, 143, 449–456. [CrossRef]

- Klinkovská, Sperandii et Al. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?lookup=0&q=Klinkovsk%C3%A1,+Sperandii+et+al.+2024&hl=en&as_sdt=0,9&as_vis=1 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Chételat, J.; Kalbermatten, M.; Lannas, K.S.M.; Spiegelberger, T.; Wettstein, J.-B.; Gillet, F.; Peringer, A.; Buttler, A. A Contextual Analysis of Land-Use and Vegetation Changes in Two Wooded Pastures in the Swiss Jura Mountains. E&S 2013, 18, art39. [CrossRef]

- Peringer, A.; Siehoff, S.; Chételat, J.; Spiegelberger, T.; Buttler, A.; Gillet, F. Past and Future Landscape Dynamics in Pasture-Woodlands of the Swiss Jura Mountains under Climate Change. Ecology and Society 2013, 18.

- Konatowska, M.; Młynarczyk, A.; Rutkowski, P.; Kujawa, K. Impact of Site Conditions on Quercus Robur and Quercus Petraea Growth and Distribution under Global Climate Change. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 4094.

- Pretzsch, H. Forest Dynamics, Growth and Yield: From Measurement to Model; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; ISBN 978-3-540-88306-7.

- Hari, P. Theoretical Aspects of Eco-Physiological Research. In Crop physiology of forest trees.; Helsinki, 1985; pp. 21–30.

- Rabotnov, T. Phytocenology: Textbook for universities in the field of “Biology” and specialty “Botany”; Moscow State University Publishing House: Moscow, 1992; ISBN 5-211-02401-X.

- Korotkov, V. Basic Concepts and Methods of Restoration of Natural Forests in Eastern Europe. Russian Journal of Ecosystem Ecology 2017, 2, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Chernenkova, T.V.; Kotlov, I.P.; Belyaeva, N.G.; Suslova, E.G. Spatiotemporal Modeling of Coniferous Forests Dynamics along the Southern Edge of Their Range in the Central Russian Plain. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Study area and layout of protected forest areas, according to: [

30].

Figure 1.

Study area and layout of protected forest areas, according to: [

30].

Figure 2.

Change in PC of species over the observed period, percent. A – tree layer, B1 – understorey, B2 – shrubs layer, C – herb-dwarf shrubs layer, D – moss layer.

Figure 2.

Change in PC of species over the observed period, percent. A – tree layer, B1 – understorey, B2 – shrubs layer, C – herb-dwarf shrubs layer, D – moss layer.

Figure 3.

Transformation of the typological composition of spruce forests (a) and successional tracks of communities’ tracks (b) during the study period. Forest types: 1 – Spruce forests of boreal type, 2 – Spruce forests of nemoral type, 3 – Spruce-pine forests of boreal type, 4 – Spruce-pine forests of nemoral type, 5 – Oak-lime forests, 6 – Birch-aspen forests, 7 – Disintegrated spruce forests of boreal type, 8 – Disintegrated spruce forests of nemoral type.

Figure 3.

Transformation of the typological composition of spruce forests (a) and successional tracks of communities’ tracks (b) during the study period. Forest types: 1 – Spruce forests of boreal type, 2 – Spruce forests of nemoral type, 3 – Spruce-pine forests of boreal type, 4 – Spruce-pine forests of nemoral type, 5 – Oak-lime forests, 6 – Birch-aspen forests, 7 – Disintegrated spruce forests of boreal type, 8 – Disintegrated spruce forests of nemoral type.

Figure 4.

Change in the activity species index of tree (a) and subcanopy layers (b) over the study period. .

Figure 4.

Change in the activity species index of tree (a) and subcanopy layers (b) over the study period. .

Figure 5.

Changes in the ecological-phytocoenotic structure of tree (a) and subcanopy layers (b) over the study period – I d.s. (a), II d.s. (b). .

Figure 5.

Changes in the ecological-phytocoenotic structure of tree (a) and subcanopy layers (b) over the study period – I d.s. (a), II d.s. (b). .

Figure 6.

Change in the activity index (A) of the most important ground layer species over the study period.

Figure 6.

Change in the activity index (A) of the most important ground layer species over the study period.

Figure 7.

Changes in the ecological-phytocoenotic structure of ground layer species over the study period – I d.s, (a), II d.s. (b). .

Figure 7.

Changes in the ecological-phytocoenotic structure of ground layer species over the study period – I d.s, (a), II d.s. (b). .

Figure 8.

NMDS ordination and correlation of relevés distribution with ordination axes and squares of correlation coefficients. Factor designation: L - light, T - temperature, R - soil reaction, M - soil moisture, N - soil nitrogen.

Figure 8.

NMDS ordination and correlation of relevés distribution with ordination axes and squares of correlation coefficients. Factor designation: L - light, T - temperature, R - soil reaction, M - soil moisture, N - soil nitrogen.

Table 1.

Change in projective cover of main layer in spruce forests over the study period, percent.

Table 1.

Change in projective cover of main layer in spruce forests over the study period, percent.

| Layers |

I d.s. |

II d.s. |

p |

| M, % |

S.D. |

M, % |

S.D. |

| A |

71.4 |

9.2 |

29.1 |

22.4 |

0.000 |

| B1 |

11.0 |

13.7 |

20.8 |

16.8 |

0.000 |

| B2 |

12.2 |

16.6 |

37.2 |

24.2 |

0.000 |

| C |

76.7 |

17.6 |

62.9 |

18.2 |

0.012 |

| D |

16.6 |

25.1 |

14.0 |

21.7 |

0,000 |

Table 2.

Classification of relevés and composition of diagnostic species.

Table 2.

Classification of relevés and composition of diagnostic species.

| №№ |

Community types |

| 1 |

Spruce with birch, aspen forests dwarf shrubs–small herb–green moss and small herb (Vaccinium myrtillus, V. vitis idaea, Oxalis acetosella, Dryopteris carthusiana, Calamagrostis arundinacea, Luzula pilosa, Carex digitata, Orthilia secunda, Pleurozium schreberi, Hylocomium splendens, Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus) |

| 2 |

Spruce with birch, aspen, oak and linden forests small herb–broad herb and broad herb (Stellaria_holostea, Aegopodium podagraria, Carex pilosa, Anemonoides nemorosa, Oxalis acetosella, Veronica chamaedrys, Carex pilosa, Ajuga reptans, Lamiastrum galeobdolon, Atrichum undulatum) |

| 3 |

Spruce-pine with birch forests dwarf shrubs–small herb–green moss and small herb (Vaccinium myrtillus, Vaccinium vitis-idaea, Oxalis acetosella, Dryopteris carthusiana, Calamagrostis arundinacea, Convallaria majalis, Pleurozium schreberi, Hylocomium splendens) |

| 4 |

Spruce-pine with birch forests small herb–broad herb and broad herb (Corylus avellana, Oxalis acetosella, Carex pilosa, Lamiastrum galeobdolon, Athyrium filix-femina, Dryopteris carthusiana). |

| 5 |

Oak-linden forests broad herbs (Aegopodium podagraria, Carex pilosa, Anemonoides ranunculoides, Galeobdolon luteum, Mercurialis perennis, Lamiastrum galeobdolon, Dryopteris filix-mas, Pulmonaria obscura, Asarum europaeum, Ranunculus cassubicus, Stellaria nemorum, Aconitum septentrionale) |

| 6 |

Birch-aspen forests with broad herb (Aegopodium podagraria, Ranunculus_cassubicus, Carex pilosa, Glechoma_hirsuta, Equisetum_pratense, Lamiastrum galeobdolon, Pulmonaria obscura, Stellaria nemorum, Calamagrostis arundinacea) |

| 7 |

Disintegrated spruce forests with spruce undergrowth and dwarf shrubs–small herb–green moss and small herb (Equisetum sylvaticum, E. pratense, Lysimachia vulgaris, Circaea alpina, Dryopteris expansa, Filipendula ulmaria, Trientalis europaea, Luzula pilosa, Orthilia secunda, Climacium dendroides) |

| 8 |

Disintegrated spruce forests with hazel and small herb–broad herb and broad herb (Corylus avellana, Stellaria nemorum, Carex sylvatica, Athyrium filix-femina, Rubus idaeus, Dryopteris carthusiana) |

Table 3.

Change in projective cover of tree layer species (A) over the study period, percent.

Table 3.

Change in projective cover of tree layer species (A) over the study period, percent.

| Species |

I d.s. |

II d.s. |

F II/I

|

p |

| M |

S.D. |

M |

S.D. |

| Acer platanoides |

0.17 |

0.66 |

0.73 |

3.2 |

0.56 |

0.000* |

|

Betula species |

8.70 |

19.8 |

4.03 |

7.9 |

-4.67 |

0.006* |

| Picea abies |

42.76 |

11.6 |

16.16 |

16.8 |

-26.60 |

0.000* |

| Pinus sylvestris |

4.56 |

11.0 |

2.84 |

6.9 |

-1.71 |

0.415 |

| Populus tremula |

6.23 |

1.5 |

1.60 |

7.6 |

-4.63 |

0.001* |

| Quercus robur |

0.64 |

0.17 |

2.29 |

7.3 |

1.64 |

0.753 |

| Tilia cordata |

3.67 |

0.66 |

4.11 |

11.4 |

0.44 |

0.780 |

Table 4.

Change in projective cover of understorey species (B1) over the study period, percent.

Table 4.

Change in projective cover of understorey species (B1) over the study period, percent.

| Species |

I d.s. |

II d.s. |

F II/I

|

p |

| M |

S.D. |

M |

S.D. |

| Acer platanoides |

1.17 |

4.15 |

4.03 |

7.4 |

2.86 |

0.010* |

|

Betula sp. |

0.07 |

0.31 |

0.43 |

1.6 |

0.36 |

0.532 |

| Picea abies |

4.00 |

6.5 |

13.7 |

14.8 |

9.7 |

0.000* |

| Populus tremula |

0.1 |

0.23 |

0.1 |

0.46 |

0 |

0.879 |

| Quercus robur |

0.31 |

1.9 |

1.6 |

4.0 |

1.29 |

0.000* |

| Tilia cordata |

2.97 |

9.9 |

3.0 |

7.8 |

0.03 |

0.553 |

Table 5.

Change in percent of shrub species (B2) over the study period, percent.

Table 5.

Change in percent of shrub species (B2) over the study period, percent.

| Species |

I d.s. |

II d.s. |

F II/I

|

p |

| M |

S.D. |

M |

S.D. |

| Corylus avellana |

5.70 |

11.7 |

26.36 |

23.7 |

20.66 |

0.000 * |

| Daphne mezereum |

0.43 |

0.91 |

0.11 |

0.62 |

-0.32 |

0.000 * |

| Euonymus verrucosa |

0.03 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.29 |

0.03 |

0.475 |

| Frangula alnus |

2.10 |

5.5 |

1.40 |

2.6 |

-0.70 |

0.218 |

| Lonicera xylosteum |

0.97 |

3.2 |

1.82 |

2.9 |

0.85 |

0.000 * |

| Sambucus racemosa |

0.49 |

1.3 |

0.83 |

2.6 |

0.35 |

0.572 |

| Sorbus aucuparia |

3.70 |

7.3 |

8.68 |

12.5 |

4.98 |

0.000 * |

| Viburnum opulus |

0.07 |

0.26 |

0.08 |

0.31 |

0.00 |

0.788 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).