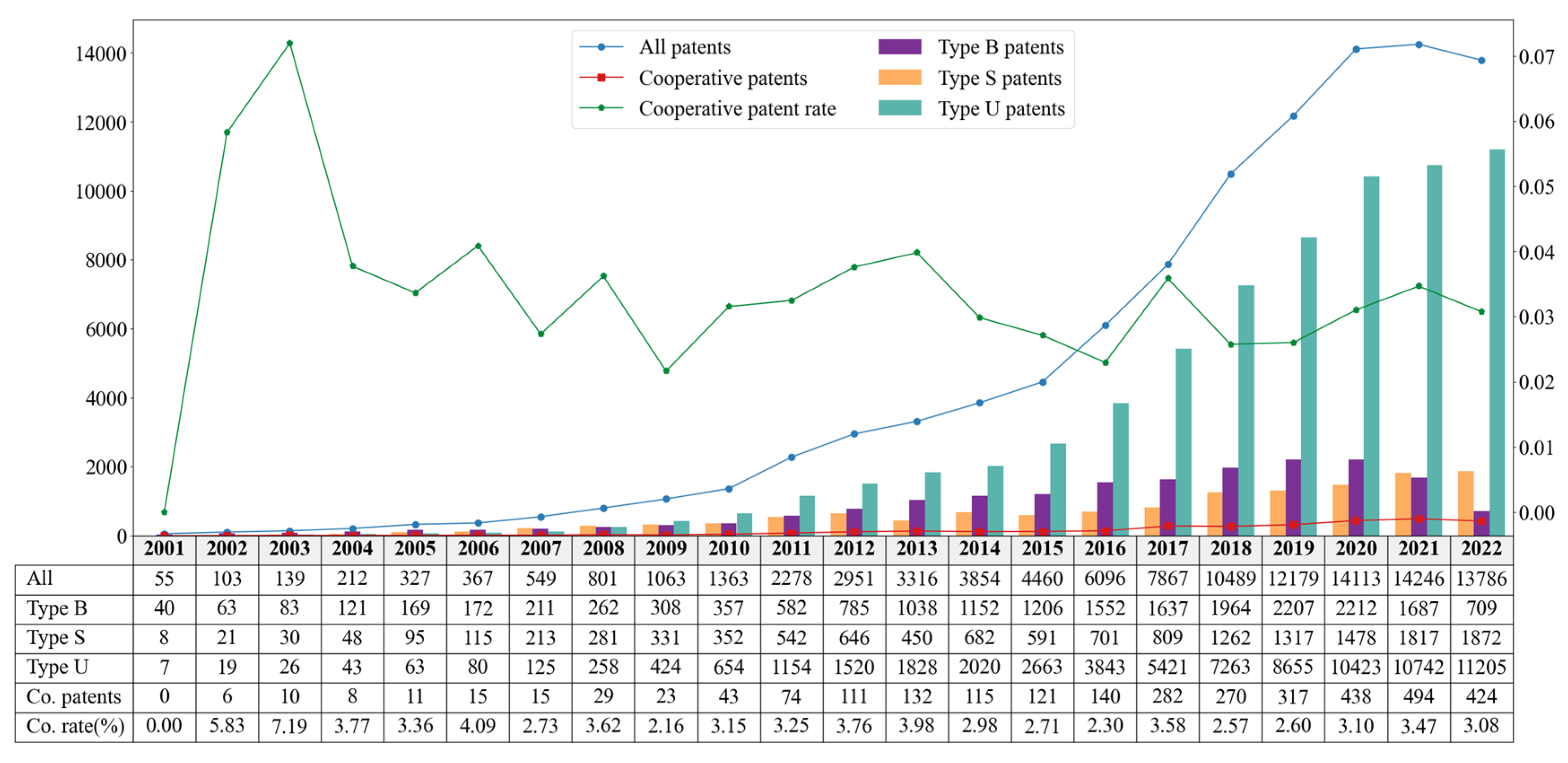

4.2.1. Overall Cooperation Network

Based on the Gephi analysis of 21,347 applicants from 2001 to 2022,

Figure 5 illustrates the patent cooperation network, where each node represents an applicant. Node size reflects degree centrality and relative importance, while edges indicate collaborative patent relationships, with edge thickness proportional to cooperation frequency. Different colors denote distinct cooperation communities; for clarity, the six largest communities are presented.

As shown in

Table 2, the cooperation network of China’s NEV industry exhibits typical features of a complex system. The network density is extremely low (0.0000087), suggesting that actual collaborations are far fewer than the potential maximum, and overall cooperation remains sparse. The network consists of 19,885 connected subgraphs, of which the largest contains only 300 nodes (1.41% of all nodes) but accounts for 25.92% of all connections and 20.21% of cooperative ties. This indicates that more than 93% of applicants exist in isolated small groups, with innovation activity highly fragmented. Most SMEs and research institutes remain outside the core network.

Despite the overall sparsity, the average clustering coefficient is high (0.711) and the average path length is relatively short (3.738), indicating a “small-world” structure [

40]. Locally, dense clusters of tightly connected innovation groups exist, while a few central hub nodes serve as bridges enabling short global paths and efficient knowledge transfer across communities. This structure allows for deep knowledge sharing within clusters and rapid diffusion across clusters through hub nodes, balancing modular stability with global efficiency.

Table 1 and

Figure 5 highlight the highly unequal power distribution. The State Grid Corporation of China (SGCC) ranks highest across degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centralities, underscoring its role as the dominant hub, primary bridge, and collaborator with other authoritative institutions. SGCC thus forms the only “super-hub” in the network. Combined with the analysis of

Table 2, it can be concluded that the patent collaboration network exhibits characteristics of a scale-free network [

41]. Other leading communities are centered on Zhejiang Geely Holding Group (private enterprise), Sinopec Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station (SOE), Huaneng Clean Energy Research Institute (SOE), Gree Altairnano New Energy Inc (private enterprise), and Shanghai Jiao Tong University (university). Notably, four of the six hubs are SOEs, reflecting the decisive role of state-owned capital and policy support in shaping China’s NEV innovation ecosystem. With the exception of SJTU, the hubs are all enterprises, confirming that firms, particularly SOEs, are the core drivers and organizers of industry–university–research collaboration. An interesting finding is that Sinopec Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station has the highest closeness centrality, making it the most efficient information hub despite its weaker resource control compared to SGCC. This likely reflects its unique position at the market interface, linking upstream component R&D, midstream complete vehicle manufacturing, and downstream services.

Comparison of

Table 1 and

Table 3 reveals a mismatch between innovation productivity and network influence. Firms such as Chery, CATL, and JAC lead in patent output (over 1,000 grants each) but do not occupy central positions in the cooperation network. Conversely, SGCC, with only 658 granted patents (ranked 13th), holds unmatched influence as a network hub. This dichotomy suggests two distinct innovation models:

Technology-independent-breakthrough-driven innovation model: Firms such as Chery, China’s largest vehicle exporter, and CATL, the world’s leading power battery manufacturer, demonstrate substantial internal R&D capabilities, as reflected in their high patent output. However, their relatively limited engagement in external collaborations results in lower network centrality, highlighting an innovation trajectory that prioritizes technological breakthroughs over cooperative integration within the broader innovation ecosystem.

Resource-integration-led innovation model: SGCC, despite moderate patent output, leverages its resource integration and infrastructural monopoly to dominate cooperation and innovation direction, demonstrating power derived from network position rather than volume of output.

In conclusion, China’s NEV patent cooperation network is structurally fragmented yet locally clustered, with a “small-world” topology shaped by a few dominant hubs. State-owned capital, particularly SGCC, plays a decisive role, creating an oligopolistic structure of “only super power and multi-great power.” The observed mismatch between patent output and network influence highlights that technological capacity does not automatically confer network power. Future industrial policy should therefore not only support technological breakthroughs but also address cooperation barriers, improve network connectivity, and enable broader participation of diverse innovation actors to enhance resilience and vitality of the overall innovation ecosystem.

Table 1.

Key nodes in the cooperation network.

Table 1.

Key nodes in the cooperation network.

| Centrality |

2001-2022 |

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

| Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

| Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

| Tsinghua University |

|

Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

| Gree Electric Appliances,Inc.of Zhuhai |

| BYD Company Limited |

| Boe Technology Group Co., Ltd. |

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

| Tsinghua University |

| Northern Altair Nanotechnologies Co., Ltd. |

| GREE ALTAIRNANO NEW ENERGY INC. |

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

| China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

| XJ Group Corporation |

| Xj Power Co., Ltd. |

Table 2.

Structural characteristics of the cooperation network.

Table 2.

Structural characteristics of the cooperation network.

| Structural characteristic |

2001-2022 |

| Network density |

0.0000087 |

| Number of network nodes |

21347 |

| Number of network connections |

1983 |

| Connecting times |

6314 |

| Average clustering coefficient |

0.711 |

| Average path length |

3.738 |

| Number of connected subgraphs |

19885 |

| Number of nodes of the maximal connected subgraphs |

300(1.41%) |

| Number of connections of maximal connected subgraphs |

514(25.92%) |

| Connecting times of maximal connected subgraphs |

1276 |

Table 3.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents.

Table 3.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents.

| Applicant |

Num. |

| Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

2101 |

| Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Ltd. |

1865 |

| Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

1302 |

| Eve Power Co., Ltd. |

1166 |

| FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

1153 |

| Hefei Gotion HIGH-TECH POWER ENERGY Co., Ltd. |

1109 |

| BYD Company Limited |

956 |

| Aodong New Energy Co., Ltd. |

949 |

| Guangzhou AUTOMOBILE Group Co., Ltd. |

866 |

| Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

847 |

| Honeycomb Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

790 |

| PAN ASIA Technical AUTOMOTIVE Center Co., Ltd. |

729 |

| State Grid Corporation of China |

658 |

| Ford Global Technologies, LLC |

629 |

| OptimumNano Energy Co.,Ltd |

563 |

| Xiamen Hithium Energy Storage Technology Co., Ltd. |

547 |

| Chongqing Changan Automobile Company Limited |

517 |

| Huating (Hefei) Hybrid Technology Co., Ltd. |

483 |

| SINOTRUK Jinan Power Co., Ltd. |

473 |

| Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

463 |

4.2.2. Temporal Evolution of the Patent Collaboration Network

During 2001–2008, the structural characteristics in

Table 5 clearly reflect the nascent period of the industry: small scale, sparse collaboration, and simple structures. The network contained only 936 nodes, with the highest density across the three periods (0.0001577), but the absolute value remained extremely low, indicating merely sporadic cooperation. As many as 870 connected subgraphs existed, while the largest subgraph contained only six nodes (0.64%), highlighting the highly fragmented nature of innovation activities and the absence of a large-scale cooperative ecosystem.

Table 4 shows that centrality was dominated by Toyota Motor Corporation and leading domestic universities (Tsinghua University, South China University of Technology, and the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, CAS). This indicates that the early-period patent collaboration network followed a typical pattern of

foreign technological leadership and academic research dominance. In contrast,

Table 6 reveals that domestic firms such as Chery and BYD had already started building patent portfolios (ranking first and second in granted patents), yet their activities were largely confined to independent R&D, lacking the ability to organize or lead collaborative networks—an

“island-type” innovation model. Policy initiatives at the time, such as the “863 Program” EV projects, primarily stimulated basic research and early technology exploration, but failed to generate large-scale collaborative innovation. Overall, the patent collaboration network during this period can be characterized as a

fragmented embryonic phase driven by foreign leadership and academic exploration.

From 2009–2017, the network entered a period of explosive growth and structural reshaping. The number of nodes increased nearly ninefold (to 8,423), with connections and collaboration frequency surging (737 and 1,828, respectively). However, network density sharply declined to 0.0000208, reflecting the influx of numerous new participants without proportionate deepening of cooperation, resulting in a

“large but sparse” structure. As illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Table 4, a fundamental structural shift occurred. The SGCC rapidly emerged as the dominant hub, ranking first in degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality, thereby replacing foreign firms and becoming the sole

super-hub of the network. Around SGCC, the largest collaboration community expanded significantly, with the largest connected subgraph containing 86 nodes (1.02%). Simultaneously, Zhejiang Geely, Sinopec’s Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station, and Shanghai Jiao Tong University rose as secondary hubs. Meanwhile, foreign enterprises such as Toyota and Hyundai witnessed a relative decline in influence. This transformation reflected the acceleration of industrialization, particularly driven by large-scale demonstration projects such as the “Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles” initiative, where state-owned giants leveraged policy advantages and infrastructure deployment (e.g., charging stations) to reshape the collaborative ecosystem, forming an emerging

“one superpower and multiple strong players” structure.

Table 6 further confirms this trend: domestic automakers and battery suppliers such as JAC Motors, Chery, and CATL experienced an explosive increase in patent output, becoming the backbone of innovation. This period thus represents the formation period of an industrialization-driven, state-owned-enterprise-led

core–periphery patent collaboration network.

Table 4.

Key nodes of collaboration network across three periods.

Table 4.

Key nodes of collaboration network across three periods.

| Centrality |

2001-2008 |

2009-2017 |

2018-2022 |

|

Toyota Motor Corporation |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

| South China University of Technology |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

| Tsinghua University |

Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

China Huaneng Group Clean Energy Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

| Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

Xj Power Co., Ltd. |

Tsinghua University |

|

Toyota Motor Corporation |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

| South China University of Technology |

Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

Gree Electric Appliances,Inc.of Zhuhai |

| Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

GEM Co., Ltd. |

BYD Company Limited |

| Shanghai Xinmingyuan Automotive Parts Co., Ltd. |

Baotou Yunsheng STRONG MAGNET Material Co., Ltd. |

State Grid Fujian Electric Power Co., Ltd. |

|

Toyota Motor Corporation |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

| Tsinghua University |

State Grid Hebei Electric Power Co., Ltd. |

Tsinghua University |

| South China University of Technology |

Beijing Institute of Technology |

Guangzhou AUTOMOBILE Group Co., Ltd. |

| Foxconn Technology Group Co.,Ltd |

State Grid Shandong Electric Power Company |

South China University of Technology |

|

Toyota Motor Corporation |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

| The University of Tokyo |

XJ Group Corporation |

State Grid Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

| KYB Corporation |

Xj Power Co., Ltd. |

China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

| Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie GmbH |

XJ Electric Co., Ltd. |

Tsinghua University |

Table 5.

Structural characteristics of collaboration network across three periods.

Table 5.

Structural characteristics of collaboration network across three periods.

| Structural characteristic |

2001-2008 |

2009-2017 |

2018-2022 |

| Network density |

0.0001577 |

0.0000208 |

0.0000102 |

| Number of network nodes |

936 |

8423 |

16011 |

| Number of network connections |

69 |

737 |

1309 |

| Connecting times |

104 |

1828 |

4382 |

| Average clustering coefficient |

0.496 |

0.701 |

0.761 |

| Average path length |

1.272 |

2.469 |

2.569 |

| Number of connected subgraphs |

870 |

7867 |

15041 |

| Number of nodes of the maximal connected subgraph |

6(0.64%) |

86(1.02%) |

188(1.17%) |

| Number of connections of the maximal connected subgraph |

6(8.7%) |

171(23.2%) |

310(23.68%) |

| Connecting times of the maximal connected subgraph |

6 |

393 |

708 |

Table 6.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents across three periods.

Table 6.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents across three periods.

| 2001-2008 |

2009-2017 |

2018-2022 |

|

| Applicant |

Num. |

Applicant |

Num. |

Applicant |

Num. |

|

| Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

222 |

Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

1096 |

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Ltd. |

1178 |

|

| BYD Company Limited |

101 |

Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

1034 |

Eve Power Co., Ltd. |

1165 |

|

| Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

95 |

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Ltd. |

687 |

FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

851 |

|

| Zhejiang Wanfeng Auto Wheel Co., Ltd. |

77 |

OptimumNano Energy Co.,Ltd |

554 |

Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

845 |

|

| The Yokohama Rubber Co., Ltd. |

66 |

PAN ASIA Technical AUTOMOTIVE Center Co., Ltd. |

399 |

Aodong New Energy Co., Ltd. |

839 |

|

| Tsinghua University |

63 |

Hefei Gotion HIGH-TECH POWER ENERGY Co., Ltd. |

330 |

Honeycomb Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

785 |

|

| Shanghai Sinofuelcell Co., Ltd. |

58 |

BYD Company Limited |

321 |

Hefei Gotion HIGH-TECH POWER ENERGY Co., Ltd. |

778 |

|

| Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

56 |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

305 |

Guangzhou AUTOMOBILE Group Co., Ltd. |

582 |

|

| Key Safety Systems, Inc. |

51 |

FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

302 |

Xiamen Hithium Energy Storage Technology Co., Ltd. |

547 |

|

| Shenzhen BAK BATTERY Co., Ltd. |

50 |

Guangzhou AUTOMOBILE Group Co., Ltd. |

284 |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

540 |

|

| PAN ASIA Technical AUTOMOTIVE Center Co., Ltd. |

45 |

Ford Global Technologies, LLC |

277 |

BYD Company Limited |

534 |

|

| Suzhou Positec Power Tools (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. |

42 |

SINOTRUK Jinan Power Co., Ltd. |

260 |

Evergrande New Energy Technology (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. |

459 |

|

| Wuhan University of Technology |

42 |

State Grid Corporation of China |

249 |

Hesai Technology Co., Ltd. |

419 |

|

| Autoliv Development AB |

39 |

Chongqing Changan Automobile Company Limited |

232 |

State Grid Corporation of China |

409 |

|

| Hitachi, Ltd. |

39 |

Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

227 |

Suteng Innovation Technology Co., Ltd. |

368 |

|

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University |

37 |

GM Global Technology Operations LLC |

199 |

Envision Dynamics Technology(Jiangsu) Co., Ltd. |

327 |

|

| South China University of Technology |

37 |

Huating (Hefei) Hybrid Technology Co., Ltd. |

170 |

Ford Global Technologies, LLC |

319 |

|

| GM Global Technology Operations, LLC |

36 |

Zhejiang Geely AUTOMOBILE Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

169 |

Huating (Hefei) Hybrid Technology Co., Ltd. |

313 |

|

| Harbin Institute of Technology |

34 |

Harbin Institute of Technology |

165 |

Envision Ruitai Dynamics Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. |

303 |

|

| Ford Global Technologies, LLC |

33 |

Ningde Amperex Technology Limited |

163 |

Jiangsu Zenergy Battery Technologies Co., Ltd. |

300 |

|

During 2018–2022, the network continued to expand (16,011 nodes) with further deepening of collaborations (4,382 connections), but density dropped to the lowest level (0.0000102), reinforcing the

“large but sparse” pattern with a vast number of peripheral participants (15,041 subgraphs). Nevertheless,

Figure 6 and

Table 4 reveal that the network core underwent accelerated integration and consolidation. SGCC further strengthened its dominance, expanding its community by absorbing top academic institutions such as Tsinghua University and South China University of Technology (the largest connected subgraph grew to 188 nodes, 1.17%). This indicates a shift in industry–academia–research cooperation from loose affiliations to tighter integration, with state-owned enterprises serving as key platforms for resource integration and technology transfer. Meanwhile, the ecosystem also became more diversified: Geely retained its importance, while new actors such as China Huaneng Group and Gree Altairnano emerged as community hubs. Notably,

Table 6 shows that specialized battery manufacturers, CATL and Eve Energy, monopolized the top two positions in granted patents, far surpassing automakers. This reflects a power shift within the industry chain toward upstream components (particularly batteries), with private enterprises holding core technologies becoming increasingly significant in innovation output.

However, a striking contrast emerges: despite CATL’s dominant patent output, it does not rank among the top centrality nodes (

Table 4). This once again illustrates that

“high patent output does not equate to high network influence.” The collaborative ecosystem remains dominated by resource-integrating SOEs such as SGCC, while technology-driven private firms emphasize internal R&D and patent generation. These two models,

resource-integration-led innovation and

technology- independent-breakthrough-driven innovation, coexist, jointly driving the dual engines of industry-wide innovation.

In summary, over the past two decades, China’s NEV patent collaboration network has followed a clear evolutionary trajectory. Network centrality has shifted from foreign firms and academic institutions to SOEs, and subsequently to a coexistence of SOEs and private firms. Structurally, the network has evolved from complete fragmentation, to the emergence of an SOE-centered “one superpower and multiple strong players” core–periphery structure, and finally to partial community integration within the core layer. Innovation models have also diverged: SOEs dominate through resource integration and ecosystem orchestration, while private enterprises excel through technological breakthroughs and high patent output. Together, these dual forces form the driving engines of China’s NEV patent innovation landscape.

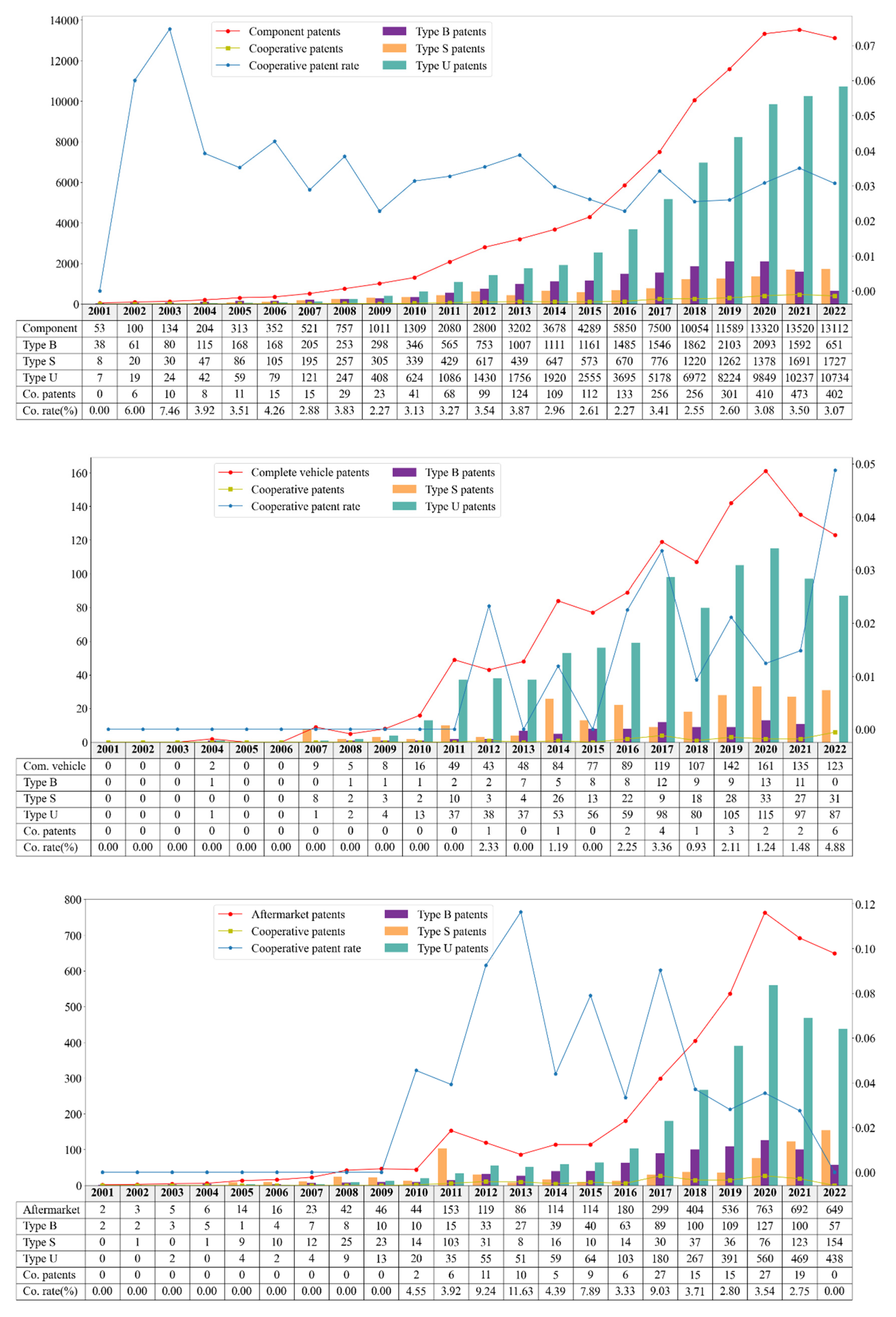

4.2.3. Patent Collaboration Networks Across Industrial Segments

As shown in

Figure 7, the State Grid Corporation of China consistently occupies the central role within all three segments of the NEV industry, underscoring its status as a key innovation orchestrator in the industrial chain. In contrast, patent collaboration in the complete vehicle segment is extremely limited. Within the aftermarket, distinct collaboration communities have emerged, led by Guangdong Brunp Recycling Technology Co., Ltd., Nanchang Cenat New Energy Co., Ltd., and Jingmen GEM Co., Ltd., while Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co., Ltd. has also established a notable collaboration community.

The component segment constitutes the largest (20,484 nodes) and most active (1,900 connections) network, yet its density is extremely low (0.0000091), reflecting a “large but fragmented” structure. The presence of 19,076 disconnected subgraphs indicates that most innovators operate in isolation or in small clusters. Nevertheless, the largest connected subgraph concentrates 25.11% of all ties, and the relatively high clustering coefficient (0.708) suggests the existence of a tightly-knit core circle. State Grid dominates degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality, making it the undisputed “innovation organizer” and “resource allocator” of the component segment. Its dominance is rooted in extensive patenting in charging infrastructure, smart grids, and battery swapping technologies. Tsinghua University plays a bridging role through its high betweenness centrality, while Sinopec’s Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station exhibits the highest closeness centrality, reinforcing its position as a unique information hub.

Table 9 further reveals that leading patent producers, such as Chery AUTOMOBILE, CATL, Jianghuai Automobile, Gotion High-Tech, and EVE Energy, are primarily battery and NEV manufacturers. This contrasts sharply with the cooperation-centered network dominated by State Grid, indicating a structural separation between “technological output” and “ecosystem power.” The component segment thus exhibits a dual structure: (i) a state-capital-driven, wide-ranging collaboration ecosystem centered on State Grid, and (ii) market-driven, R&D-intensive innovation dominated by battery and NEV firms. Together, they define the innovation dynamics of the upstream industry chain.

Table 7.

Key nodes of collaboration networks across three segments.

Table 7.

Key nodes of collaboration networks across three segments.

| Centrality |

Component |

Complete vehicle |

Aftermarket |

|

|

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

|

|

| Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd. |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

|

|

| Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company |

XJ Electric Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| Tsinghua University |

Hangzhou West Lake New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

Xj Power Co., Ltd. |

|

|

|

Sinopec Sales Co., Ltd. Guangdong Zhuhai Dongfang Gas Station |

State Grid Corporation of China |

Guangdong Brunp Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| BYD Company Limited |

Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd. |

Hunan Brunp Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| Gree Electric Appliances, Inc. of Zhuhai |

Hangzhou West Lake New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

Nanchang Cenat New ENERGY Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| Guangdong Power Grid Corporation |

Liuzhou Liugong Forklifts Co., Ltd. |

Jingmen GEM Co., Ltd. |

|

|

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

|

|

| Tsinghua University |

Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd. |

China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| Northern Altair Nanotechnologies Co., Ltd. |

State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company |

China Networks Shanghai Electric Power Company |

|

|

| GREE ALTAIRNANO NEW ENERGY INC. |

Hangzhou West Lake New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

|

|

|

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

State Grid Corporation of China |

|

|

| China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company |

XJ Electric Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| Tsinghua University |

Sichuan Electric Power Vocational and Technical College |

Xj Power Co., Ltd. |

|

|

| State Grid Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. |

Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd. |

XJ Group Corporation |

|

|

Table 8.

Structural characteristics of collaboration networks across three segments.

Table 8.

Structural characteristics of collaboration networks across three segments.

| Structural characteristic |

Component |

Complete vehicle |

Aftermarket |

| Network density |

0.0000091 |

0.0001996 |

0.0000851 |

| Number of network nodes |

20484 |

470 |

1987 |

| Number of network connections |

1900 |

22 |

168 |

| Connecting times |

5871 |

38 |

358 |

| Average clustering coefficient |

0.708 |

0.926 |

0.82 |

| Average path length |

3.764 |

1.083 |

2.056 |

| Number of connected subgraphs |

19076 |

451 |

1873 |

| Number of nodes of the maximal connected subgraph |

290(1.42%) |

4(0.85%) |

37(1.86%) |

| Number of connections of the maximal connected subgraph |

477(25.11%) |

4(18.18%) |

68(40.48%) |

| Connecting times of the maximal connected subgraph |

1110 |

4 |

141 |

Table 9.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents across three segments.

Table 9.

Top 20 applicants by granted patents across three segments.

| Component |

Complete vehicle |

Aftermarket |

| Applicant |

Num. |

Applicant |

Num. |

Applicant |

Num. |

| Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

1965 |

Anhui Heli Co., Ltd. |

267 |

Aodong New Energy Co., Ltd. |

552 |

| Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Ltd. |

1855 |

Hangcha Group Co., Ltd. |

71 |

Chery AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

210 |

| Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

1254 |

Beidou Aerospace Automotive (Beijing) Co., Ltd. |

26 |

Anhui Xinnangang Automotive Interiors Co., Ltd. |

120 |

| Eve Power Co., Ltd. |

1163 |

Banyitong Science & Technology Developing Co., Ltd. |

23 |

State Grid Corporation of China |

109 |

| Hefei Gotion HIGH-TECH POWER ENERGY Co., Ltd. |

1092 |

Anhui Airuite New Energy Special Purpose Vehicle Co., Ltd. |

21 |

Beijing Taisheng Tiancheng Technology Co., Ltd. |

93 |

| FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

1088 |

China DRAGON Development HOLDINGS Limited |

20 |

Shanghai Dianba New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

76 |

| BYD Company Limited |

943 |

Luoyang Dahe New Energy Vehicle Co., Ltd. |

20 |

Hunan Brunp Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. |

66 |

| Guangzhou AUTOMOBILE Group Co., Ltd. |

841 |

Anhui Yufeng Equipment Co., Ltd. |

18 |

Huawei Technologies Co.,Ltd. |

64 |

| Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

803 |

FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

16 |

Bozhon PRECISION Industry Technology Co., Ltd. |

62 |

| Honeycomb Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

790 |

Henan Senyuan Heavy Industry Co., Ltd. |

14 |

Hunan Jinkai Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. |

60 |

| PAN ASIA Technical AUTOMOTIVE Center Co., Ltd. |

716 |

Zhengzhou BAK New ENERGY AUTOMOBILE Co., Ltd. |

13 |

FAW Group Co., Ltd. |

60 |

| Ford Global Technologies, LLC |

629 |

Zhejiang Haoli Electric Vehicle Manufacturing Co., Ltd. |

13 |

Guangdong Brunp Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. |

58 |

| State Grid Corporation of China |

556 |

Anhui Jiangtian Sanitation Equipment Co., Ltd. |

13 |

Shenzhen FINE Automation Co., Ltd. |

52 |

| OptimumNano Energy Co.,Ltd |

555 |

Nanjing Jiayuan SPECIAL Electric Vehicles Manufacture Co., Ltd. |

12 |

Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

50 |

| Xiamen Hithium Energy Storage Technology Co., Ltd. |

547 |

Hangzhou West Lake New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. |

11 |

Zhejiang Jizhi New Energy Vehicle Technology Co., Ltd. |

49 |

| Chongqing Changan Automobile Company Limited |

502 |

Kion Baoli (Jiangsu)Forklift Co., Ltd. |

11 |

NIO Technology (Anhui) Co., Ltd. |

48 |

| Huating (Hefei) Hybrid Technology Co., Ltd. |

483 |

Chongqing Bingding Electromechanical Co., Ltd. |

11 |

Ningbo Shintai Machines Co., Ltd. |

48 |

| Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

463 |

Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group Corp.,Ltd. |

10 |

Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Company Limited |

47 |

| SINOTRUK Jinan Power Co., Ltd. |

461 |

Anhui Jianghuai Heavy Construction Machinery Co., Ltd. |

10 |

Chengdu Monolithic Power Systems Co., Ltd. |

45 |

| Evergrande New Energy Technology (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. |

459 |

Shanxi TianJishan Electric Vehicle and Vessel Co., Ltd. |

10 |

Chengdu Iyasaka Technology Development Co., Ltd. |

41 |

The complete vehicle segment presents the weakest network structure, with only 470 nodes and 22 connections. Despite a slightly higher density (0.0001996), its maximal connected subgraph is extremely small (4 nodes, 0.85%), and collaboration is nearly absent. Yet, its clustering coefficient reaches 0.926, indicating that the very few collaborations occur in tightly closed circles, such as intra-group subsidiaries or limited university–industry partnerships. State Grid and Guangxi Liugong appear among central actors primarily due to cross-industry activities in specialized vehicles (e.g., forklifts, sanitation vehicles) rather than mainstream passenger or commercial vehicles. The lack of a unifying collaboration hub is striking.

Table 9 confirms this insularity: Anhui Heli, a forklift manufacturer, ranks first with only 267 patents, far below the thousand-level counts seen in the component segment. The overall profile is fragmented and small-scale, reflecting fierce competition, dispersed resources, and a strong preference for closed, independent R&D strategies. The complete vehicle segment exemplifies an “innovation island” model, where firms erect high technological barriers and exhibit minimal willingness to collaborate, partly due to high integration complexity, confidentiality requirements, and market pressures.

The aftermarket segment is moderate in scale (1,987 nodes) but more active in collaboration (168 connections) compared to the complete vehicle segment. Its largest connected subgraph accounts for 40.48% of ties, with a high clustering coefficient (0.82), indicating the emergence of specialized innovation communities with dense internal linkages. The power structure here has shifted significantly: while State Grid remains important, battery recycling and materials regeneration firms, such as Guangdong Brunp, GEM, and Cenat, have risen to prominence in closeness centrality rankings. Geely also appears across multiple rankings due to its diversified deployment. These findings highlight that innovation in the aftermarket segment is now centered on “battery recycling, second-life applications, and materials recovery,” with specialized circular-economy firms replacing traditional giants as key collaboration hubs.

Table 9 corroborates this trend: Aodong New Energy, focusing on battery-swapping, tops the list, alongside Brunp and GEM. This suggests that with the growing stock of NEVs, end-of-life battery management has become a technology-intensive and innovation-driven new frontier, attracting substantial patent activity. The aftermarket thus exemplifies a cluster-oriented innovation model driven by emerging market demand and led by specialized firms.

Overall, innovation activities in China’s NEV industry chain are marked by pronounced “segmentation across segments”: a dual structure of cooperation and independent R&D in components, a closed and inward-looking pattern in complete vehicles, and a rapidly growing, cluster-based ecosystem in the aftermarket. Bridging these segments—particularly fostering openness among complete vehicle firms and integrating them into the broader innovation ecosystem—remains a critical challenge for future industrial policy. Although State Grid plays a central role in both the component and aftermarket segments, its influence has yet to penetrate the complete vehicle core, underscoring the complexities of achieving full-chain collaboration.

4.2.4. Patent Collaboration Networks of Domestic and Foreign Applicants

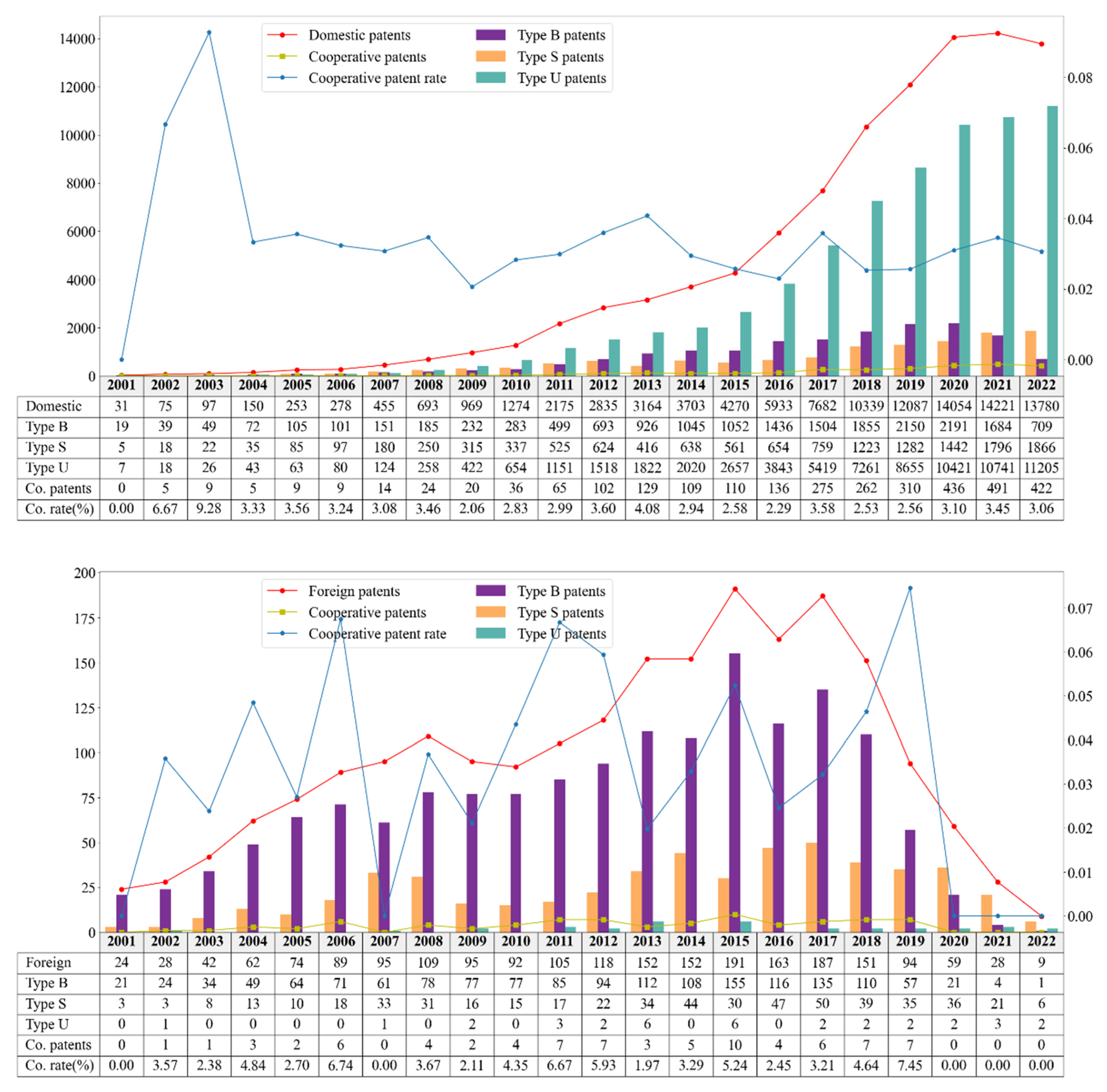

Figure 8 illustrates the patent collaboration communities of domestic and foreign applicants in China’s NEV industry. Compared with the domestic collaboration communities, the communities formed by foreign applicants are significantly smaller in scale, and their central nodes are primarily automobile manufacturers. The two largest foreign applicant communities are led by entities from South Korea and Japan, with the Japanese cluster also integrating German applicants. In contrast, the domestic collaboration communities largely mirror the structure observed in

Figure 1.

Table 10 presents the key nodes of domestic and foreign collaboration networks.

Table 11 summarizes their structural characteristics. The domestic network is vast, with 20,716 nodes, yet extremely sparse (density = 0.0000088), exhibiting a typical core–periphery structure. The presence of 19,342 disconnected subgraphs indicates that over 93% of innovation actors remain isolated or at the periphery. However, the largest connected subgraph aggregates 27.17% of all connections, coupled with a high clustering coefficient (0.726), demonstrating the existence of a tightly integrated core power circle. Consistent with overall network analysis, SGCC dominates degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centralities, confirming its role as the absolute hub and gatekeeper of innovation resources. This core circle is composed of state-owned enterprises (e.g., State Grid, Sinopec), large private firms (e.g., Geely, Gree), and elite universities (e.g., Tsinghua University), forming a relatively closed cooperation system strongly shaped by state capital and policy influence. Sinopec Zhuhai Gas Station again emerges as a unique information hub with the highest closeness centrality.

Patent output data in

Table 12 highlight the domestic network’s vitality. Leading firms such as Chery, CATL, and JAC each hold more than 1,000 granted patents, far surpassing any single foreign applicant. This indicates that, in terms of patent output volume, Chinese firms, supported by industrial policies and market-driven incentives, hold an overwhelming advantage. In summary, the domestic network can be characterized as a policy- and state-capital-driven mega-ecosystem: a powerful yet relatively closed core orchestrates resource flows, surrounded by a vast periphery of marginalized small and medium actors. Overall, patent quantity has experienced explosive growth.

In contrast, the foreign collaboration network is much smaller (629 nodes) but considerably denser (density = 0.0003949), suggesting relatively frequent collaboration among foreign entities operating in China. Nonetheless, its largest connected subgraph includes only 15 nodes, implying that collaboration is confined to small, elite circles with limited integration into the broader domestic innovation ecosystem. As shown in

Table 10, network power is highly concentrated in traditional automotive giants such as Hyundai, Toyota, Kia, and Audi. Importantly, the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) ranks high in betweenness and eigenvector centralities, reflecting South Korea’s model of close industry–university–research collaboration. The foreign network’s structure follows a “firm + core supplier (e.g., ThyssenKrupp) + leading university” configuration—a tightly knit, technology- and supply-chain-based exclusive club.

Patent output comparisons in

Table 12 further reinforce this contrast. The top foreign applicant, Ford (629 granted patents), holds fewer patents than China’s 13th-ranked applicant, underscoring the scale gap. This may be related to the more selective patenting strategies of multinational corporations in the Chinese market. In sum, the foreign network constitutes a small, cohesive, high-barrier “elite club” that operates largely in parallel to, rather than integrated with, the domestic innovation ecosystem—an ecological separation that reflects limited embeddedness.

Notably, cross-ecosystem collaboration remains minimal. As shown by

Table 2 and

Table 11, there are only 24 collaboration links and 29 collaboration events between domestic and foreign applicants—an extremely low level given the vast sizes of the two networks (20,716 vs. 629 nodes). This provides quantitative evidence of the community segregation observed in

Figure 8.

This finding indicates that, despite active foreign patent deployment in China, their innovation activities remain largely detached from the domestically dominated ecosystem. The result is a form of parallel development, with limited effective, deep, and strategic technological exchange. Such weak connectivity highlights potential “decoupling” risks in the NEV industry’s global innovation chain. For China, this suggests that while domestic firms have achieved numerical dominance in patents, future progress requires greater openness, higher-level international collaboration mechanisms, and the integration of global innovators into the core ecosystem. Strengthening such cross-boundary innovation loops will be essential to enhancing the global competitiveness and resilience of China’s NEV industry.