Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

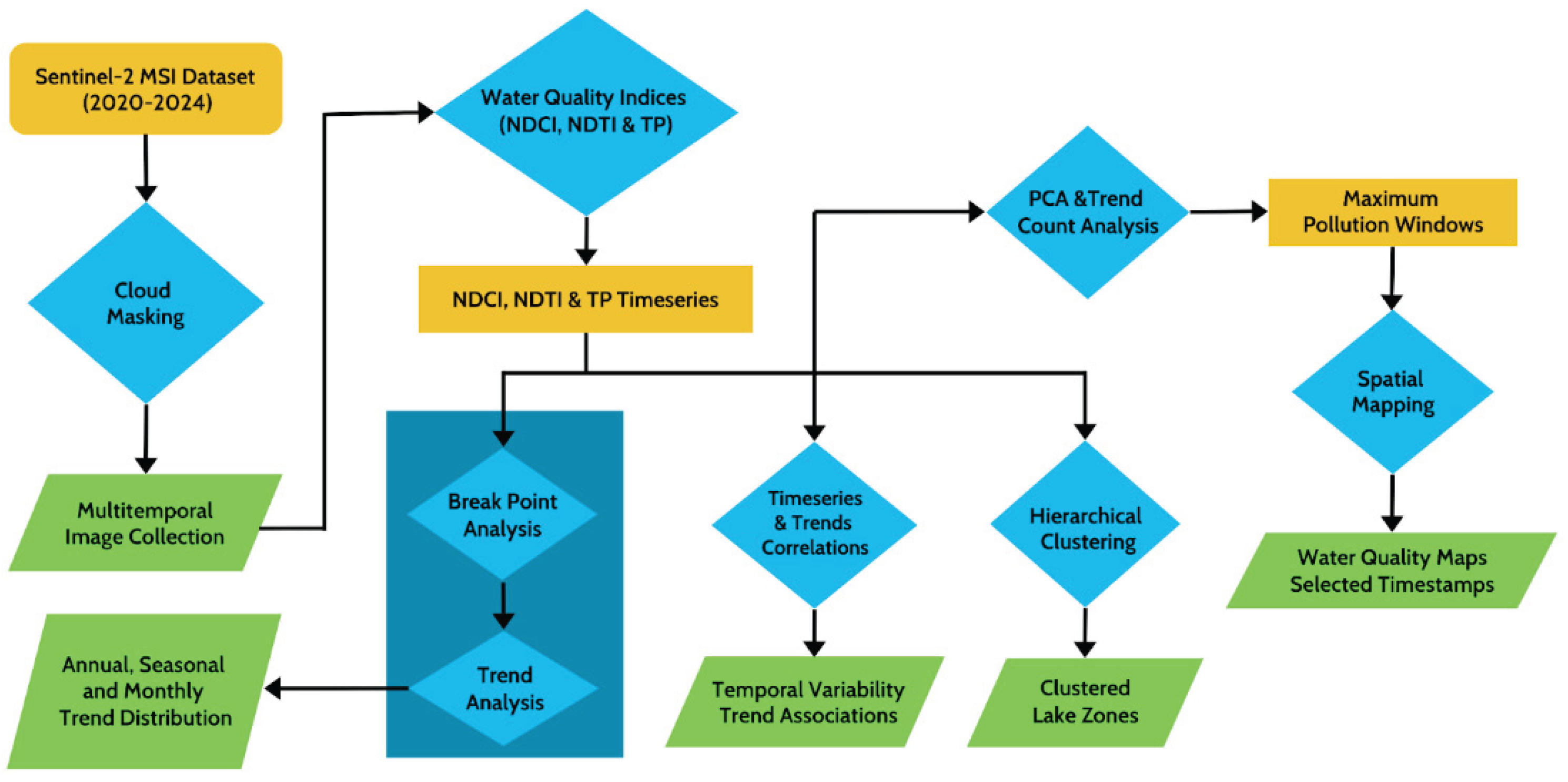

2. Materials and Methods

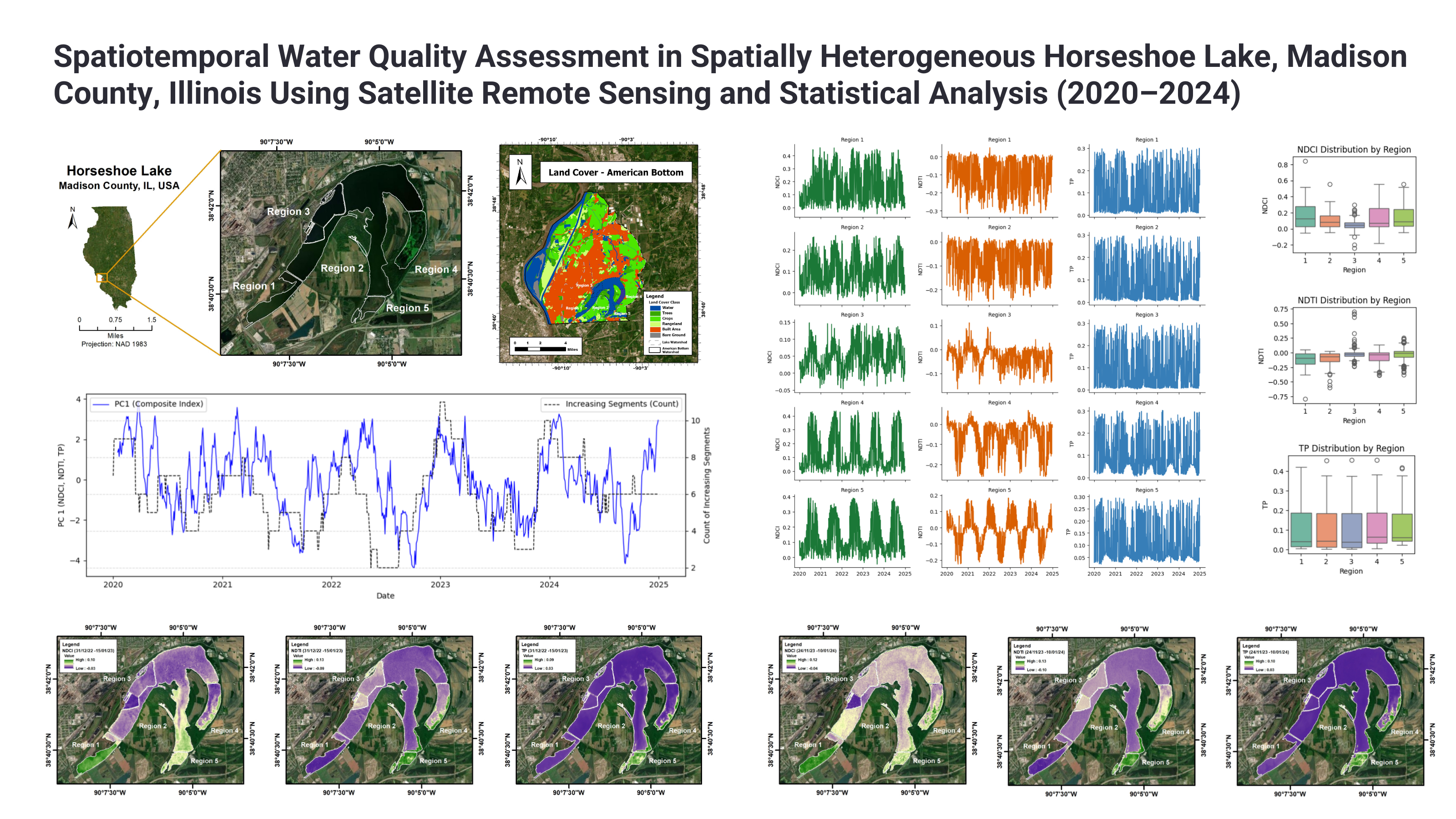

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Tools Used

2.2.1. Data Used

2.2.2. ArcGIS Pro

2.2.3. Google Earth Engine (GEE)

2.2.4. Programming Interface

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Water Quality Indices

- NDCI (Equation 1) estimates chlorophyll-a concentration and detects algal blooms by combining Sentinel-2 Band 5 (red-edge, B5) and Band 4 (red, B4). Areas with high values indicate elevated phytoplankton activity [72].NDCI = (B5 – B4)/(B5 + B4)

- NDTI (Equation 2) measures turbidity and suspended sediment levels using Sentinel-2 Band 4 (red, B4) and Band 3 (green, B3). Higher NDTI values typically correspond to poor water clarity due to sediment load [73].NDTI = (B4 – B3)/(B4 + B3)

2.3.2. Break Point and Trend Analysis

2.3.3. Time Series & Trends Correlations

2.3.4. Hierarchical Clustering for Regional Grouping

2.3.5. PCA & Trend Count Analysis for Maximum Pollution Windows

2.3.6. Spatial Mapping for High-Pollution Windows

3. Results

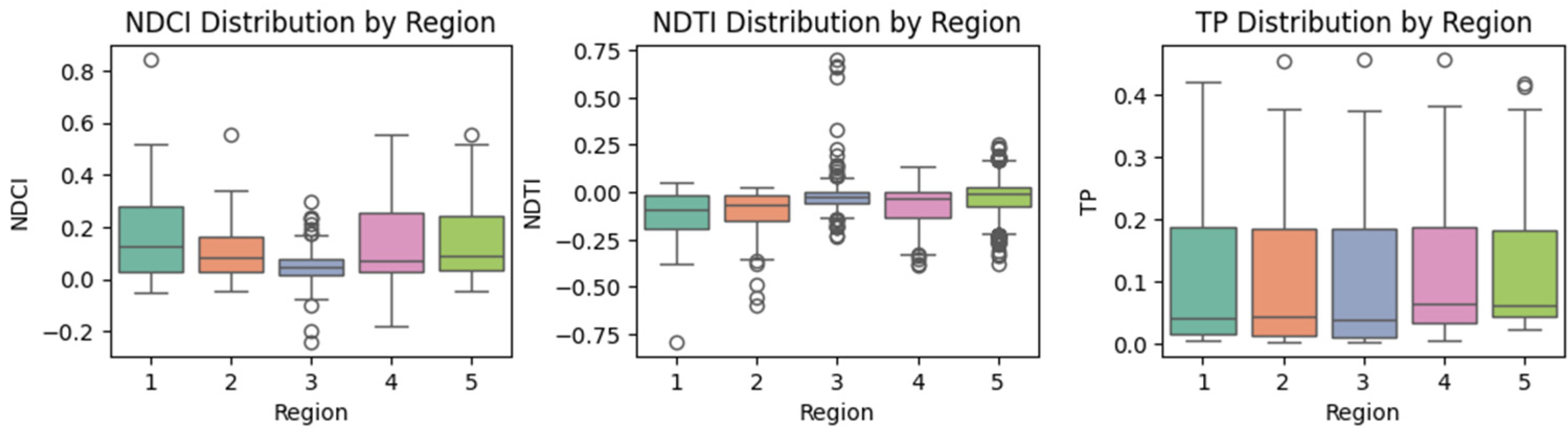

3.1. Time Series Extraction of Water Quality Indicators

3.2. Trends in Water Quality Parameters

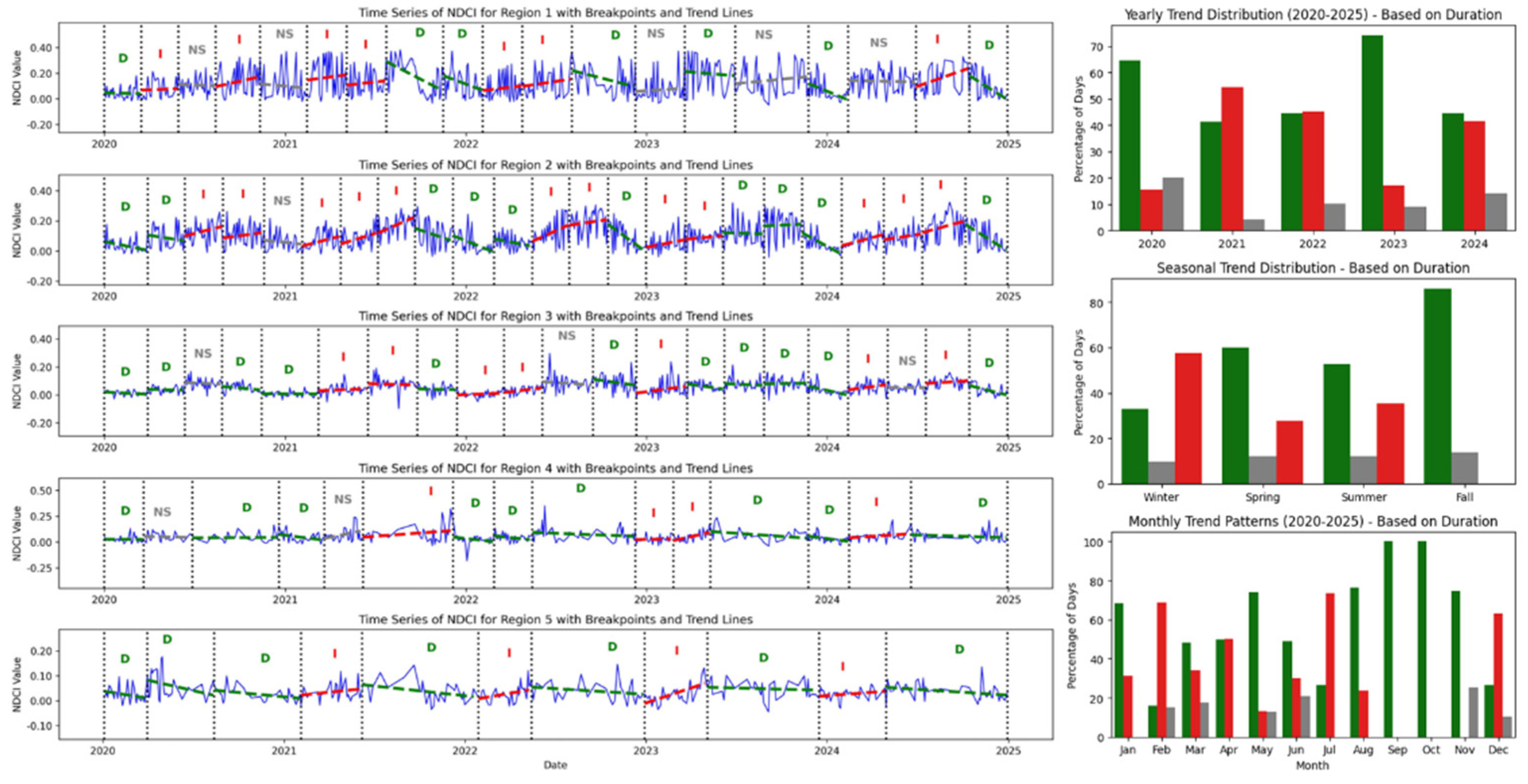

- Trends in NDCI: The left part of Figure 5 shows NDCI trend segments across five lake regions. Region 1 experienced a fairly balanced sequence of increasing and decreasing trends, with a few non-significant periods. It shows recurring fluctuations, especially between 2021 and 2023. Region 2 started with short-term declines, followed by frequent alternating increases and decreases. Region 3 showed higher variability, with short trend segments and more frequent declines during 2021–2023. Region 4 had longer periods of consistent decline, especially from mid-2020 to late 2022, with limited signs of recovery. In contrast, Region 5 experienced some of the longest periods of both increase and decrease. It showed extended rises in NDCI during 2022 and early 2024, followed by a decline through the end of the study period. The right set of subplots summarizes trend distributions across annual, seasonal, and monthly scales for NDCI. Annually, decreasing trends dominated in 2020 and 2023, while 2021 and 2022 showed more frequent increases. Seasonally, fall had the strongest NDCI declines, with 86% of periods showing decreasing trends. Spring and summer displayed a mix of increases and decreases. Winter recorded the highest share of increasing trends at 58%. Monthly patterns followed these trends, with February and July showing peaks in increases, while September and October were entirely marked by declines.

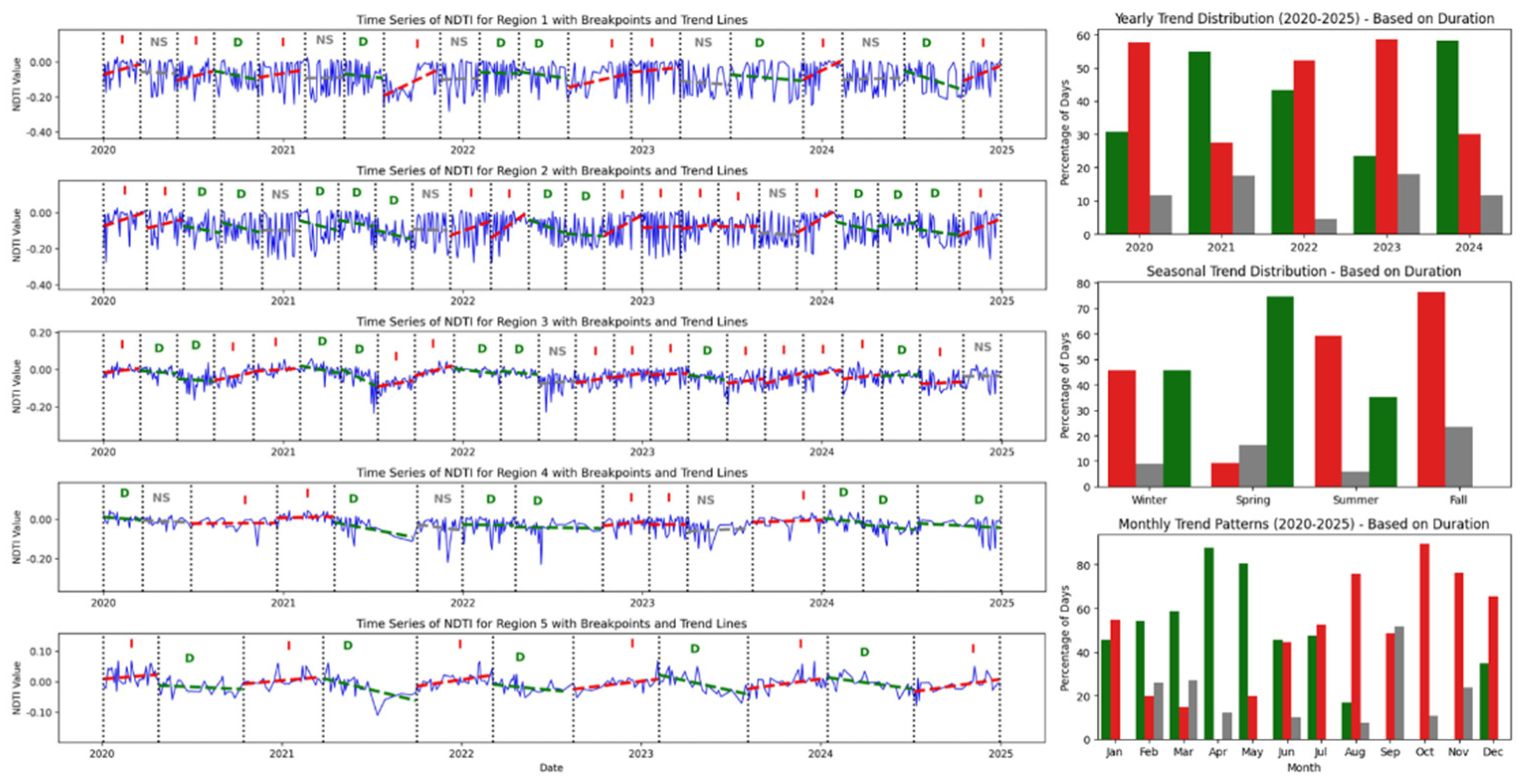

- Trends in NDTI: The left side of Figure 6 shows NDTI trends from 2020 to 2024 across the five lake regions. Region 1 had a mix of trends, with several short periods of increase and a few longer decreasing segments, showing alternating turbidity behavior. Region 2 showed mostly increasing trends early on, but more decreasing periods appeared between 2021 and 2023. A few increases returned in 2024. Region 3 was the most dynamic, with many short segments and a balance of increases and decreases. However, there was a cluster of persistent increases from late 2022 through 2024. Region 4 was dominated by long periods of decreasing turbidity from 2021 to 2023, followed by several shorter increases, suggesting recovery followed by new disturbances. Region 5 had the most consistent increases, especially in 2020, late 2022, and throughout 2024. The right panel of Figure 6 shows NDTI trends by year, season, and month. In 2020 and 2023, increasing trends were most common, reaching up to 59%. In 2021 and 2024, decreasing trends were more frequent, reaching 55% to 58%. Spring had the highest share of decreasing trends at 74%. Fall showed the most increasing trends at 77%. Summer had a mix of both. Winter showed nearly equal shares of increases and decreases. At the monthly level, April and May had the strongest decreases, with up to 88%. August, October, and November showed the highest increases.

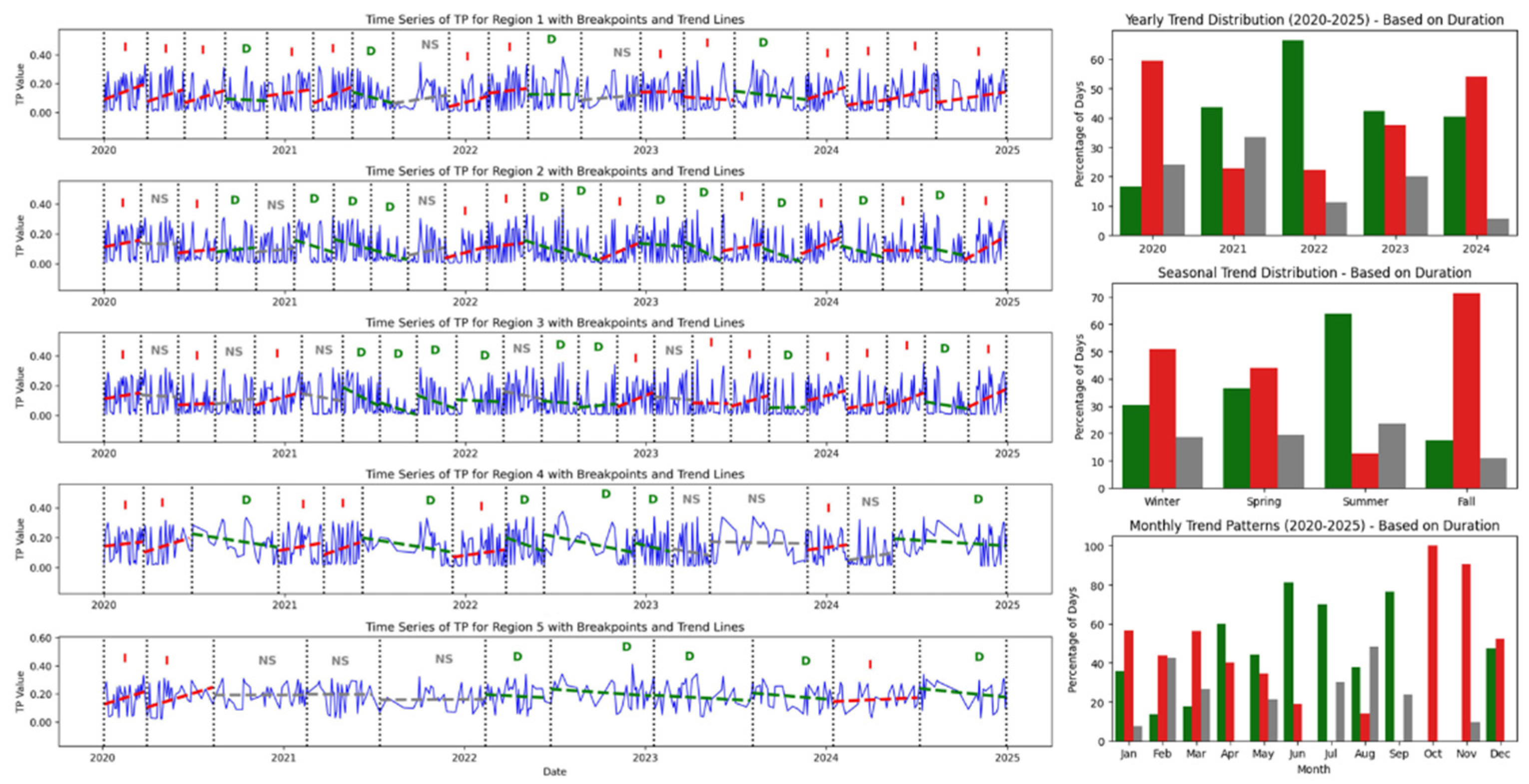

- Trends in TP: The left panel of Figure 7 shows TP trends in Horseshoe Lake from 2020 to 2024. Region 1 had mostly increasing trends throughout the period, with short declines in late 2020 and mid-2021. Region 2 showed a mix of patterns, with early increases, mid-period declines, and more increases in 2024. Region 3 started with mostly increasing and non-significant trends, but showed consistent declines in mid to late 2022 and again in 2024. Region 4 had an early increasing phase, followed by a long declining trend from mid-2021 to late 2023, then returned to short increases and stable periods. Region 5 showed the most prolonged and consistent increases, especially from early 2020 and again in late 2023 to the end of 2024, with only a few brief declining periods. The right of Figure 7 panel summarizes annual, seasonal, and monthly TP trends. In 2020, increasing trends were highest at 59%. In 2021 and 2022, decreasing trends were more common, peaking at 66% in 2022. Increases returned in 2023 and 2024. Summer had the highest share of decreasing trends at 64%. Fall showed the most increasing trends at 72%. Spring and winter had more balanced patterns. Monthly trends followed this pattern. June and September had the strongest decreases. October and November showed the highest increases, close to 100%. February and August had more non-significant trends.

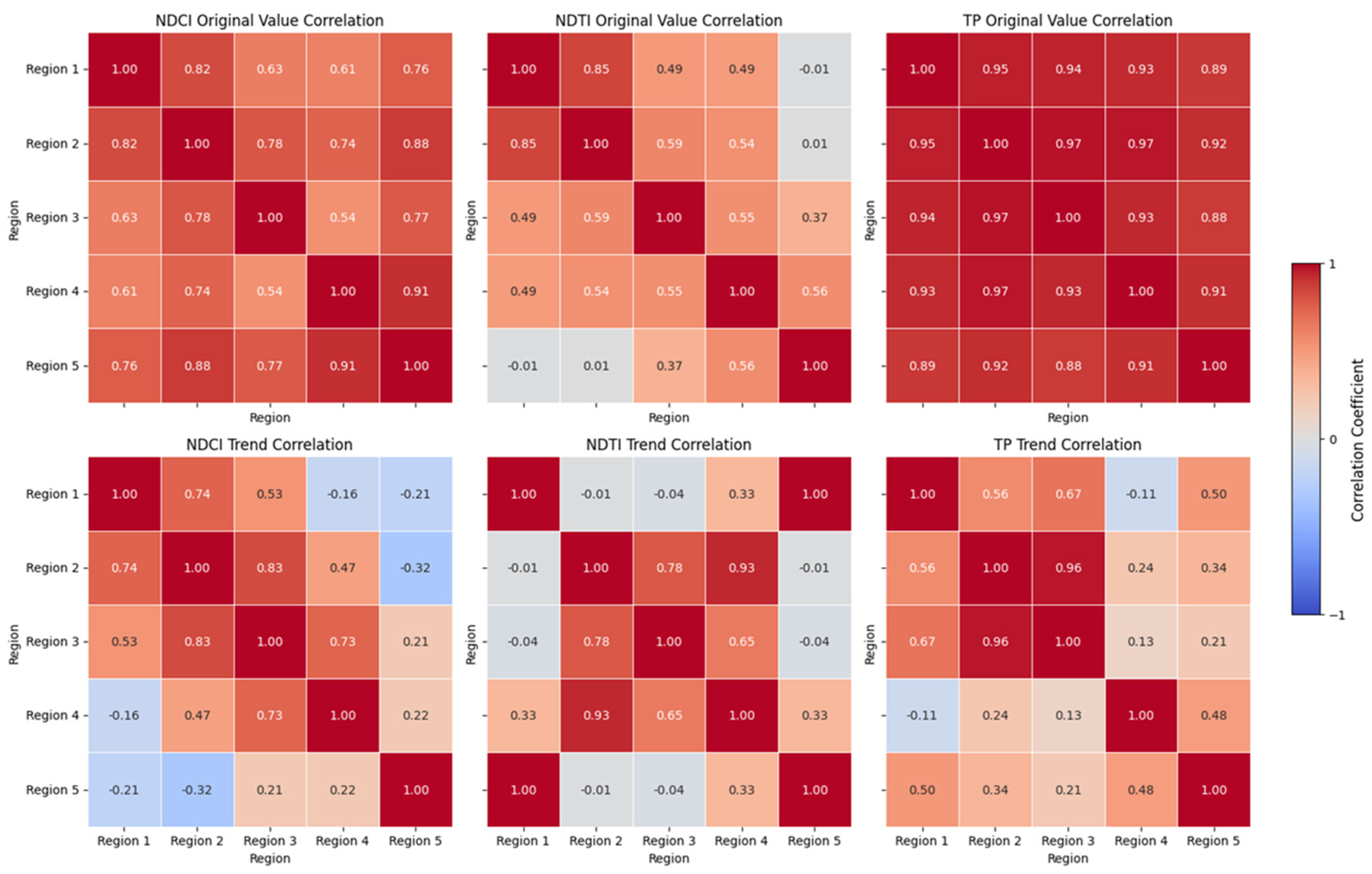

3.3. Time Series & Trends Correlations

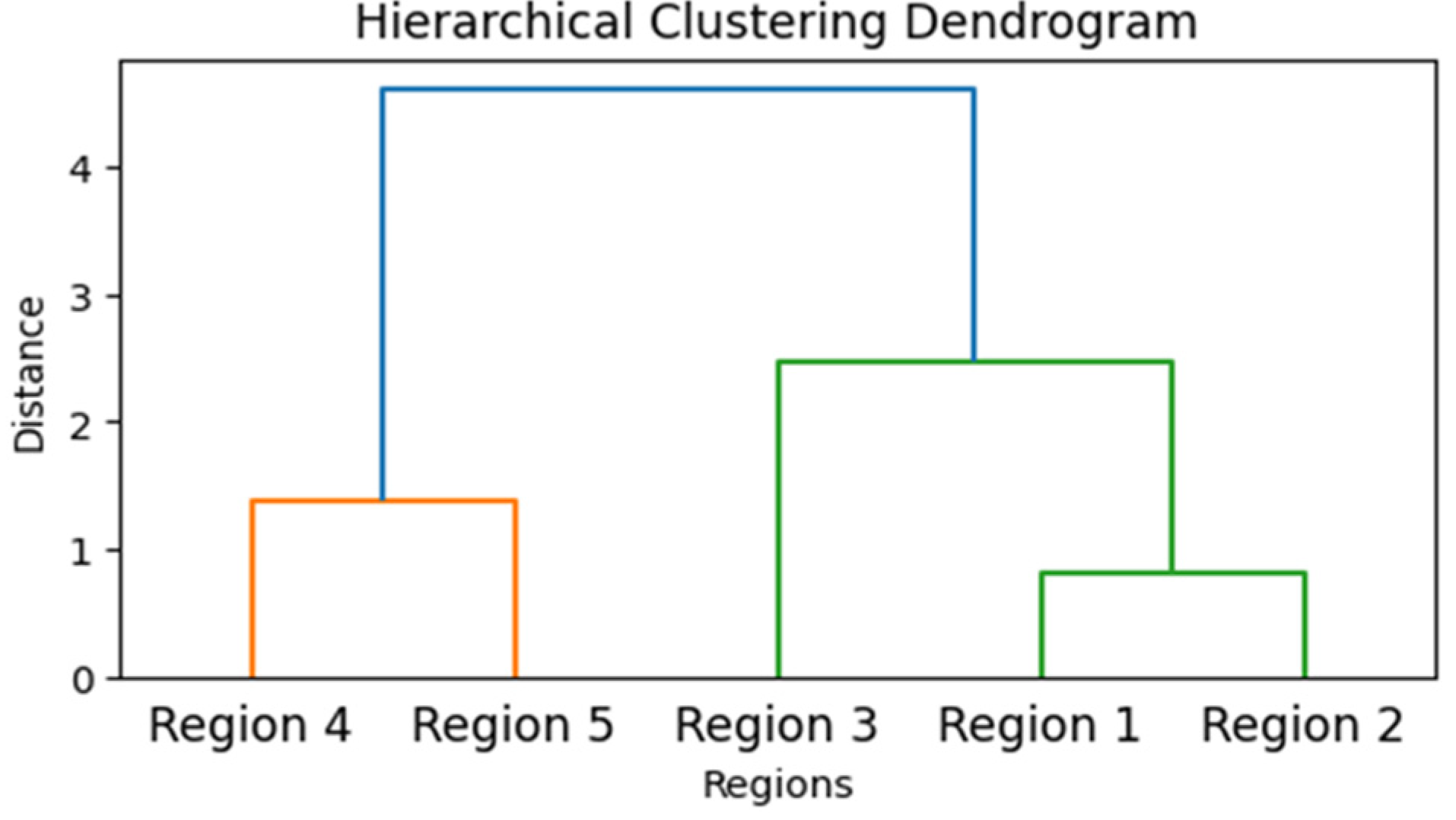

3.4. Hierarchical Clustering for Regional Grouping

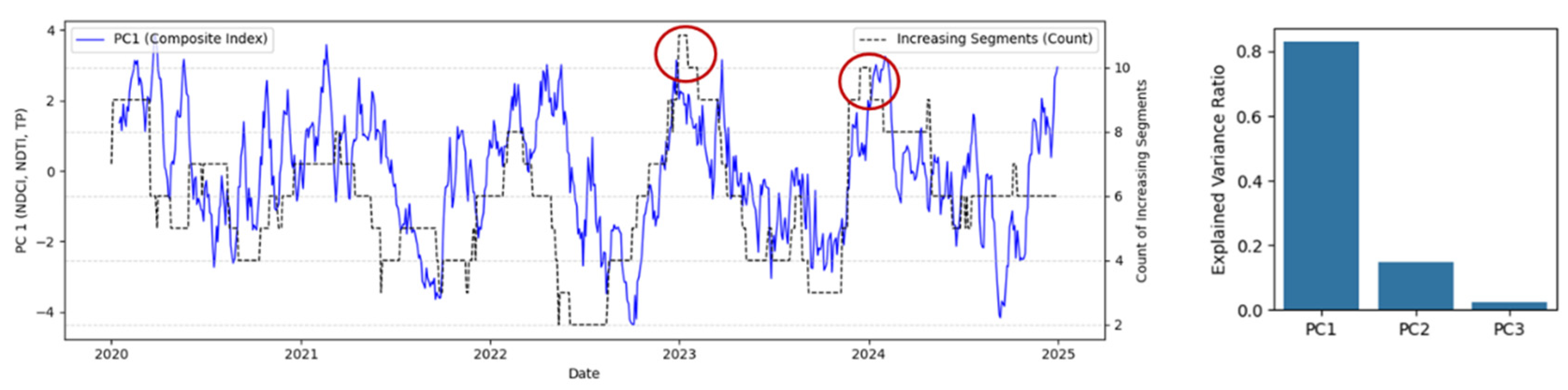

3.5. PCA & Trend Count Analysis for Maximum Pollution Windows in HSL Lake

- 31 Dec 2022 – 15 Jan 2023: During this period, PC1 values stayed above 4.0, with a peak of 4.7. This shows strong pollution across chlorophyll, turbidity, and phosphorus. The number of increasing segments reached 11, the highest in the full time series. This suggests a fast and steady rise in pollution indicators.

- 24 Nov 2023 – 10 Jan 2024: In this window, PC1 values stayed high (between 3.5 and 4.1). The increasing trend count remained between 9 and 10. This shows a longer-lasting pollution event with steady upward changes in water quality indicators.

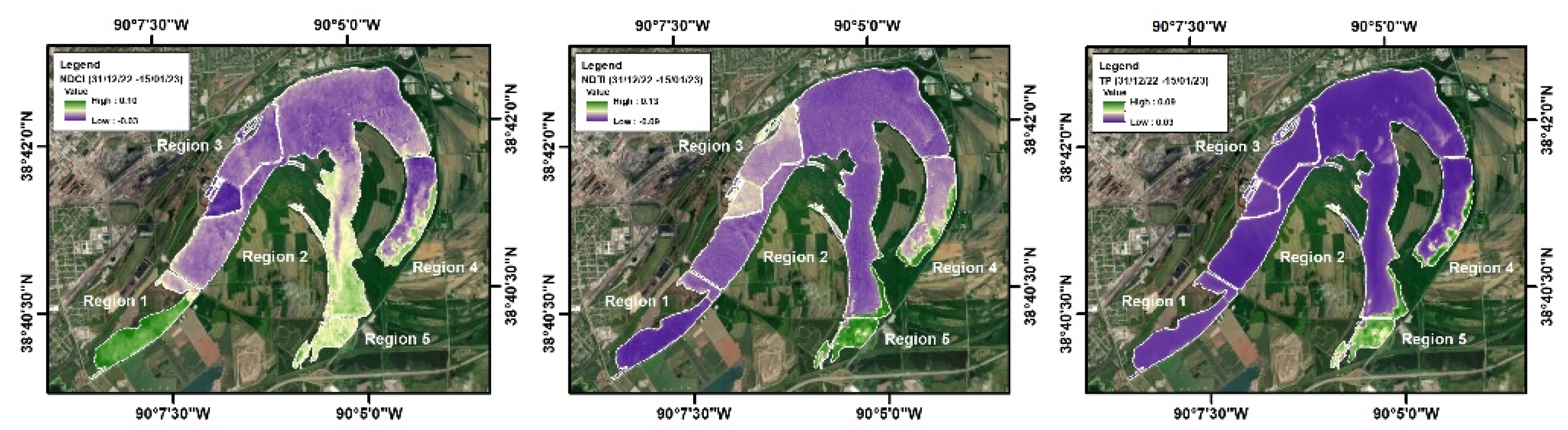

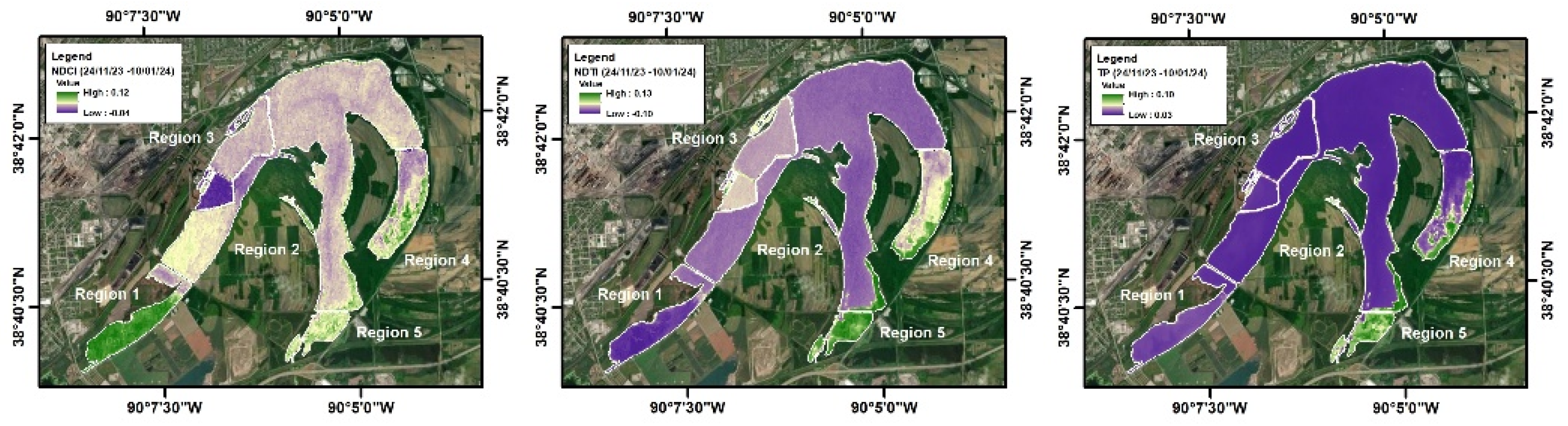

3.6. Regional Water Quality Patterns During Pollution Peaks

- 31 Dec 2022 – 15 Jan 2023: The NDCI map shows high chlorophyll levels in Region 1 and Region 5 (green areas), indicating strong algal activity. Region 2 has moderate values, mostly in its southern part. Region 3 records the lowest NDCI (purple), suggesting clearer water. Region 4 shows a mix of low and moderate values. These patterns suggest that biological stress was highest in the southern and southeastern zones, aligning with the PC1 pollution peak. The NDTI map highlights elevated turbidity in Region 5, likely from sediment or surface runoff. Region 4 has small patches of moderate turbidity. Regions 1, 2, and 3 mostly show low values (purple), reflecting clearer conditions. This suggests turbidity stress was concentrated in Region 5. TP values were also highest in Region 5 and parts of Region 4. These areas likely received nutrients from nearby agriculture or disturbed sediments. In contrast, Regions 1, 2, and 3 show low phosphorus levels. Together, these findings show that nutrient and turbidity-related pollution was localized in the southeastern part of the lake.

- 24 Nov 2023 – 10 Jan 2024: During this period, high NDCI values appear in Region 1 and parts of Region 5, indicating strong algal growth. Region 3 has the lowest chlorophyll levels, while Regions 2 and 4 show moderate values with a few high-value patches. The spatial spread points to increased biological stress in the southern and southeastern lake zones. Turbidity was again highest in Region 5, shown by green areas on the NDTI map. Region 4 has moderate turbidity, while the rest of the lake (Regions 1, 2, and 3) shows lower values. This indicates that physical disturbance was concentrated in Region 5. The TP map shows a similar pattern. Regions 4 and 5 had the highest phosphorus levels, suggesting nutrient inputs from runoff or sediments. The other regions remained low in TP. The overlap of high NDCI, NDTI, and TP confirms a strong, localized pollution hotspot in the southern zones during this window.

4. Discussion

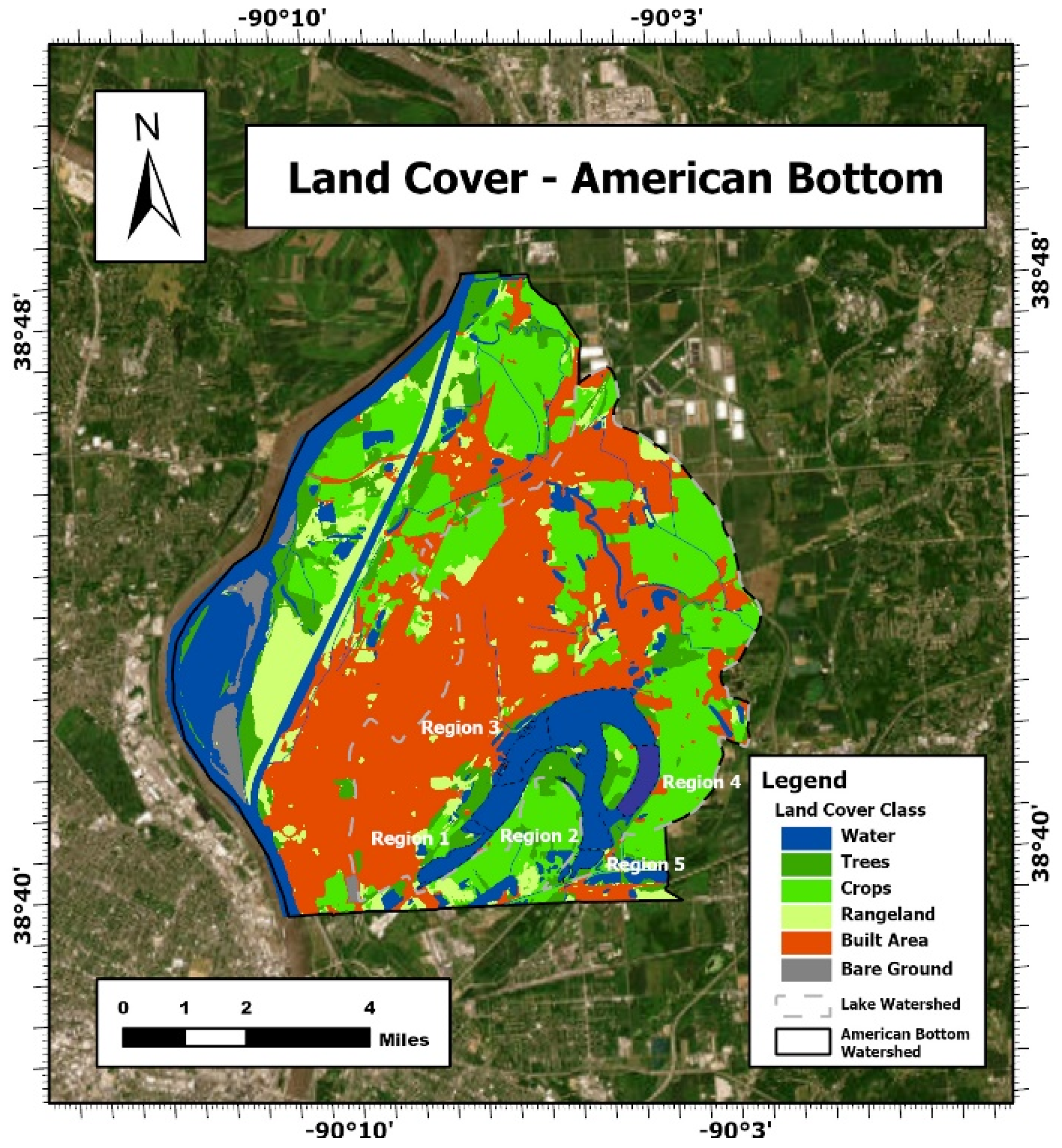

- Regional Drivers of Pollution and Spatial Heterogeneity: Horseshoe Lake is situated within the American Bottom watershed, a floodplain of the Mississippi River where land use is dominated by urban development and agriculture. The land cover distribution (Figure 13) provides critical context for interpreting spatial patterns in water quality. The consistently high chlorophyll levels in the north are best understood as a consequence of stormwater culverts draining Granite City into Region 1. This aligns with the elevated NDCI values and recurring increases in high chlorophyll concentration we observed, showing how concentrated urban inflows shape ecological conditions in that part of the lake. On the eastern margin, croplands surround Region 5 and deliver multiple agricultural discharges. This landscape setting helps explain why Region 5 emerged as the most persistent hotspot of turbidity and phosphorus enrichment. The combination of nutrient-rich inflows, shallow bathymetry, and sediment resuspension reinforces a chronic stress regime that was evident across multiple indicators and time windows. The western side of the lake has a different trajectory. Historically, industrial effluent from Granite City Steel (later Granite City Works) contributed a distinct loading source [57,58]. With operations now idled and discharges halted, this industrial signature has largely disappeared. As a result, Horseshoe Lake has become more strongly dependent on stormwater, agricultural runoff, and seasonal snowmelt as its external drivers of change. Inflows from Elm Slough, Long Lake, and the Cahokia Drainage Canal further reinforce the connectivity between watershed processes and lake dynamics, producing spatial synchrony among several central and eastern regions. Together, these patterns underscore the importance of considering both landscape context and hydrological connectivity in explaining water quality variation. The land cover map highlights how urban, agricultural, and historical industrial zones each leave distinct ecological fingerprints on different parts of the lake. This reinforces the need for region-specific management rather than a uniform intervention strategy.

- Temporal Disruption and Seasonality in Trends: Breakpoint detection revealed that water quality does not follow simple linear trajectories but is punctuated by abrupt changes. These shifts are often triggered by episodic storm events, flood diversions, or seasonal nutrient pulses. Seasonal trend summaries confirmed that fall and winter are periods of elevated risk, with frequent increases in turbidity and phosphorus even when algal activity is less visible. Such “latent stress” periods underscore the limitations of summer-centric monitoring campaigns and highlight the importance of year-round satellite-based assessments.

- Inter-Zonal Synchronization and Spatial Clustering: Correlation analysis and hierarchical clustering demonstrated that not all regions respond uniformly to external pressures. Regions 1 and 2 exhibited similar water quality behavior, reflecting shared exposure to urban runoff. Regions 4 and 5 consistently clustered together, reflecting common nutrient and turbidity stress from agricultural inflows and shallow bathymetry. Region 3 stood apart as a transitional zone, influenced by mixed inputs but buffered relative to the more polluted zones. These findings emphasize that lake-wide interventions may overlook critical spatial heterogeneity, and that tailored management strategies are required at the sub-regional scale.

- Implications for Monitoring and Adaptive Management: The integrated framework of this study, combining satellite remote sensing, statistical segmentation, clustering, and dimensionality reduction, provides a scalable model for monitoring complex inland lakes. The land cover map (Figure 13) strengthens this framework by spatially linking regional water quality dynamics with surrounding land-use drivers and inflow points. Importantly, the decline of industrial inputs from Granite City Works signals a new era in Horseshoe Lake’s hydrology, one where stormwater, agricultural runoff, and snowmelt dominate external loading. This transition reinforces the need for adaptive management strategies that prioritize watershed-scale interventions, control of nutrient-rich runoff, and enhanced resilience under climate-driven increases in extreme precipitation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NDCI | Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index |

| NDTI | Normalized Difference Turbidity Index |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| K-PCA | Kernel Principal Component Analysis |

| SOM | Self-Organizing Map |

| MAR | Multivariate Autoregressive Model |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| S2_SR_HARMONIZED | Sentinel-2 Surface Reflectance Harmonized dataset |

| QA60 | Sentinel-2 Cloud Mask Bitmask |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared |

| Dynp | Dynamic Programming algorithm (ruptures library) |

| mgd | Million Gallons per Day |

References

- Smith, S.V., Renwick, W.H., Bartley, J.D., & Buddemeier, R.W. (2002). Distribution and significance of small, artificial water bodies across the United States landscape. Science of the Total Environment, 299(1–3), 21–36. [CrossRef]

- Karpatne, A., Khandelwal, A., Chen, X., Mithal, V., Faghmous, J., & Kumar, V. (2016). Global monitoring of inland water dynamics: State-of-the-art, challenges, and opportunities. Computational sustainability, 121-147. [CrossRef]

- Goodell, E. B. (1904). A review of the laws forbidding pollution of inland waters in the United States.

- Marstrand, P. K. (2019). Pollution of Inland Waters. In Environmental Pollution Control (pp. 89-104). Routledgel (pp. 89-104). Routledge.

- Dodds, W. K., Bouska, W. W., Eitzmann, J. L., Pilger, T. J., Pitts, K. L., Riley, A. J., & Schloesser, J. T. (2009). Eutrophication of U.S. freshwaters: analysis of potential economic damages. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(1), 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Behmel, S., Damour, M., Ludwig, R., & Rodriguez, M. J. (2016). Water quality monitoring strategies, A review and future perspectives. Science of the Total Environment, 571, 1312-1329. [CrossRef]

- Sandhwar, V. K., Saxena, S., Saxena, D., Tiwari, A., & Parikh, S. M. (2025). Future trends and emerging technologies in water quality management. Computational Automation for Water Security, 229-249.

- Cao, Q., Yu, G., & Qiao, Z. (2023). Application and recent progress of inland water monitoring using remote sensing techniques. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 195(1), 125. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., Zhang, Y., Pan, D., Yang, S. X., & Gharabaghi, B. (2024). Review of recent advances in remote sensing and machine learning methods for lake water quality management. Remote Sensing, 16(22), 4196. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Ling, H., Wu, D., Su, X., & Cao, Z. (2021). Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 observations for harmful algae blooms in a small eutrophic lake. Remote Sensing, 13(21), 4479. [CrossRef]

- Meng, H., Zhang, J., & Zheng, Z. (2022). Retrieving inland reservoir water quality parameters using landsat 8-9 OLI and sentinel-2 MSI sensors with empirical multivariate regression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7725. [CrossRef]

- Declaro, A., & Kanae, S. (2024). Enhancing surface water monitoring through multi-satellite data-fusion of Landsat-8/9, Sentinel-2, and Sentinel-1 SAR. Remote Sensing, 16(17), 3329. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., & Moore, R. (2017). Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote sensing of Environment, 202, 18-27. [CrossRef]

- AppEEARS. (2024). Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). NASA LP DAAC. https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov/.

- Melton, F. S., Huntington, J., Grimm, R., Herring, J., Hall, M., Rollison, D., ... & Anderson, R. G. (2022). OpenET: Filling a critical data gap in water management for the western United States. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 58(6), 971-994. [CrossRef]

- Brezonik, P., Menken, K. D., & Bauer, M. (2005). Landsat-based remote sensing of lake water quality characteristics, including chlorophyll and colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM). Lake and Reservoir Management, 21(4), 373-382. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., & Anderson, Y. (2016). Estimating chlorophyll-a concentration in a freshwater lake using Landsat 8 Imagery. J. Environ. Earth Sci, 6(4), 134-142.

- Boucher, J. M., Weathers, K. C., Norouzi, H., Prakash, S., & Saberi, S. J. (2016). Assessing the effectiveness of Landsat 8 chlorophyll-a retrieval algorithms for regional freshwater management. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2016, pp. B43A-0555).

- Xu, M., Liu, H., Beck, R., Lekki, J., Yang, B., Shu, S., ... & Benko, T. (2019). A spectral space partition guided ensemble method for retrieving chlorophyll-a concentration in inland waters from Sentinel-2A satellite imagery. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 45(3), 454-465. [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N., Smith, B., Schalles, J., Binding, C., Cao, Z., Ma, R., ... & Stumpf, R. (2020). Seamless retrievals of chlorophyll-a from Sentinel-2 (MSI) and Sentinel-3 (OLCI) in inland and coastal waters: A machine-learning approach. Remote Sensing of Environment, 240, 111604. [CrossRef]

- Salls, W. B., Schaeffer, B. A., Pahlevan, N., Coffer, M. M., Seegers, B. N., Werdell, P. J., ... & Keith, D. J. (2024). Expanding the Application of Sentinel-2 Chlorophyll Monitoring across United States Lakes. Remote Sensing, 16(11), 1977. [CrossRef]

- Mallin, M. A., Johnson, V. L., & Ensign, S. H. (2009). Comparative impacts of stormwater runoff on water quality of an urban, a suburban, and a rural stream. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 159, 475-491. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Y., & Lusk, M. G. (2018). Nutrients in urban stormwater runoff: Current state of the science and potential mitigation options. Current Pollution Reports, 4, 112-127. [CrossRef]

- Toming, K., Kutser, T., Laas, A., Sepp, M., Paavel, B., & Nõges, T. (2016). First experiences in mapping lake water quality parameters with Sentinel-2 MSI imagery. Remote Sensing, 8(8), 640. [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M., Ferdous, J., & An, K. G. (2021). Empirical estimation of nutrient, organic matter and algal chlorophyll in a drinking water reservoir using landsat 5 tm data. Remote Sensing, 13(12), 2256. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S., & Dutta Roy, A. (2025). Satellite-Based Monitoring of Water Quality in Mukutmanipur Dam: A Google Earth Engine Approach. In Remotely Sensed Rivers in the Age of Anthropocene (pp. 637-657). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Gholizadeh, M. H., Melesse, A. M., & Reddi, L. (2016). A comprehensive review on water quality parameters estimation using remote sensing techniques. Sensors, 16(8), 1298. [CrossRef]

- Cardall, A., Tanner, K. B., & Williams, G. P. (2021). Google Earth Engine tools for long-term spatiotemporal monitoring of chlorophyll-a concentrations. Open Water Journal, 7(1), 4.

- Taheri Dehkordi, A., Valadan Zoej, M. J., Ghasemi, H., Jafari, M., & Mehran, A. (2022). Monitoring long-term spatiotemporal changes in iran surface waters using landsat imagery. Remote Sensing, 14(18), 4491. [CrossRef]

- Navabian, M., Vazifedoust, M., & Varaki, M. E. (2023). A multi-sensor framework in google earth engine for spatio-temporal trend analysis of water quality parameters in Anzali lagoon.

- Meals, D. W., Spooner, J., Dressing, S. A., & Harcum, J. B. (2011). Statistical analysis for monotonic trends. Tech notes, 6, 1-23.

- Kundzewicz, Z., & Robson, A. (2000). Detecting trend and other changes in hydrological data. World Meteorological Organization.

- Anderson, N. J. (2014). Landscape disturbance and lake response: temporal and spatial perspectives. Freshwater Reviews, 7(2), 77-120. [CrossRef]

- Osgood, R. A. (2017). Inadequacy of best management practices for restoring eutrophic lakes in the United States: guidance for policy and practice. Inland Waters, 7(4), 401-407. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, L., Chen, Y., & Yang, L. (2022). Spatiotemporal heterogeneities and driving factors of water quality and trophic state of a typical urban shallow lake (Taihu, China). Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(35), 53831-53843. [CrossRef]

- Su, S., Ma, K., Zhou, T., Yao, Y., & Xin, H. (2025). Advancing methodologies for assessing the impact of land use changes on water quality: a comprehensive review and recommendations. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 47(4), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Ngamile, S., Madonsela, S., & Kganyago, M. (2025). Trends in remote sensing of water quality parameters in inland water bodies: a systematic review. Frontiers in environmental science, 13, 1549301. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y., Jia, L., Menenti, M., Zheng, C., Jiang, M., Lu, J., ... & Bennour, A. (2024). A novel remote sensing method to estimate pixel-wise lake water depth using dynamic water-land boundary and lakebed topography. International Journal of Digital Earth, 17(1), 2440443. [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. F., & Voth, M. L. (2012). Application of MODIS imagery for intra-annual water clarity assessment of Minnesota lakes. Remote Sensing, 4(7), 2181-2198. [CrossRef]

- Torbick, N., Hession, S., Hagen, S., Wiangwang, N., Becker, B., & Qi, J. (2013). Mapping inland lake water quality across the Lower Peninsula of Michigan using Landsat TM imagery. International journal of remote sensing, 34(21), 7607-7624. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Huang, Q., Chang, J., Liu, S., & Wang, Y. (2016). Period analysis of hydrologic series through moving-window correlation analysis method. Journal of Hydrology, 538, 278-292. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, T., Schmidt, S. I., Kutzner, R. D., Bernert, H., Stelzer, K., Friese, K., & Rinke, K. (2024). Exploring Spatial Aggregations and Temporal Windows for Water Quality Match-Up Analysis Using Sentinel-2 MSI and Sentinel-3 OLCI Data. Remote Sensing, 16(15), 2798. [CrossRef]

- Read, E. K., Patil, V. P., Oliver, S. K., Hetherington, A. L., Brentrup, J. A., Zwart, J. A., ... & Weathers, K. C. (2015). The importance of lake-specific characteristics for water quality across the continental United States. Ecological Applications, 25(4), 943-955. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Jingtao, Jinling Cao, Qigong Xu, Beidou Xi, Jing Su, Rutai Gao, Shouliang Huo, and Hongliang Liu. "Spatial heterogeneity of lake eutrophication caused by physiogeographic conditions: An analysis of 143 lakes in China." Journal of Environmental Sciences 30 (2015): 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, S. (1984). The modifiable areal unit problem. Concepts and techniques in modern geography.

- Chakraborty, J., Maantay, J. A., & Brender, J. D. (2011). Disproportionate proximity to environmental health hazards: methods, models, and measurement. American journal of public health, 101(S1), S27-S36. [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. W. (2004). The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP). In WorldMinds: geographical perspectives on 100 problems: commemorating the 100th anniversary of the association of American geographers 1904–2004 (pp. 571-575). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Longley, P. A., Goodchild, M. F., Maguire, D. J., & Rhind, D. W. (2015). Geographic information science and systems. John Wiley & Sons.

- Tang, W., & Lu, Z. (2022). Application of self-organizing map (SOM)-based approach to explore the relationship between land use and water quality in Deqing County, Taihu Lake Basin. Land Use Policy, 119, 106205. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q., Hu, H., Ma, L., Sheng, L., Yang, S., Zhang, X., ... & Chen, L. (2019). Characterizing the spatial variations of the relationship between land use and surface water quality using self-organizing map approach. Ecological Indicators, 102, 633-643. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Pan, C., Chang, Y., & Luo, M. (2021). An integrated autoregressive model for predicting water quality dynamics and its application in Yongding River. Ecological Indicators, 133, 108354. [CrossRef]

- Jumber, M. B., Damtie, M. T., & Tegegne, D. (2024). Integration of multivariate adaptive regression splines and weighted arithmetic water quality index methods for drinking water quality analysis. Water Conservation Science and Engineering, 9(1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S., Ibrahim, H., Hussein, H., Elsherbiny, O., Elmetwalli, A. H., Moghanm, F. S., ... & Gad, M. (2021). Assessment of water quality in Lake Qaroun using ground-based remote sensing data and artificial neural networks. Water, 13(21), 3094. [CrossRef]

- Ding, F., Zhang, W., Cao, S., Hao, S., Chen, L., Xie, X., ... & Jiang, M. (2023). Optimization of water quality index models using machine learning approaches. Water research, 243, 120337. [CrossRef]

- Deboeck, G., & Kohonen, T. (Eds.). (2013). Visual explorations in finance: with self-organizing maps. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Perelman, L., Arad, J., Housh, M., & Ostfeld, A. (2012). Event detection in water distribution systems from multivariate water quality time series. Environmental science & technology, 46(15), 8212-8219. [CrossRef]

- Hill, Thomas E., Ralph L. Evans, and J. Scott Bell. "Water quality assessment of Horseshoe Lake." ISWS Contract Report CR 249 (1981).

- Brugam, Richard, Indu Bala, Jennifer Martin, Brian Vermillion, and William Retzlaff. "The sedimentary record of environmental contamination in Horseshoe Lake, Madison County, Illinois." Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 96 (2003): 205-217.

- Google Developers. (n.d.). Harmonized Sentinel-2 MSI: MultiSpectral Instrument, Level-2A | Earth Engine Data Catalog. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/COPERNICUS_S2_SR_HARMONIZED.

- ArcGIS Pro. (2023). Version 3.1. Redlands. CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

- Kwong, Ivan HY, Frankie KK Wong, and Tung Fung. "Automatic mapping and monitoring of marine water quality parameters in Hong Kong using Sentinel-2 image time-series and Google Earth Engine cloud computing." Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (2022): 871470. [CrossRef]

- Handbook, Sentinel User, and Exploitation Tools. "Sentinel-2 user handbook." ESA Standard Document Date 1 (2015): 1-64.

- Traganos, Dimosthenis, Bharat Aggarwal, Dimitris Poursanidis, Konstantinos Topouzelis, Nektarios Chrysoulakis, and Peter Reinartz. "Towards global-scale seagrass mapping and monitoring using Sentinel-2 on Google Earth Engine: The case study of the Aegean and Ionian Seas." Remote Sensing 10, no. 8 (2018): 122. [CrossRef]

- Bisong, Ekaba. "Google colaboratory. Building machine learning and deep learning models on google cloud platform." Apress, Berkeley, CA (2019): 59-64. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, Wes. "Data structures for statistical computing in Python." scipy 445, no. 1 (2010): 51-56.

- Harris, Charles R., K. Jarrod Millman, Stéfan J. Van Der Walt, Ralf Gommers, Pauli Virtanen, David Cournapeau, Eric Wieser et al. "Array programming with NumPy." nature 585, no. 7825 (2020): 357-362. [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Pauli, Ralf Gommers, Travis E. Oliphant, Matt Haberland, Tyler Reddy, David Cournapeau, Evgeni Burovski et al. "SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python." Nature methods 17, no. 3 (2020): 261-272.

- Pedregosa, Fabian, Gaël Varoquaux, Alexandre Gramfort, Vincent Michel, Bertrand Thirion, Olivier Grisel, Mathieu Blondel et al. "Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python." the Journal of machine Learning research 12 (2011): 2825-2830.

- Hunter, John D. "Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment." Computing in science & engineering 9, no. 03 (2007): 90-95. [CrossRef]

- Waskom, Michael L. "Seaborn: statistical data visualization." Journal of open source software 6, no. 60 (2021): 3021. [CrossRef]

- Akbarnejad Nesheli, Sara, Lindi J. Quackenbush, and Lewis McCaffrey. "Estimating Chlorophyll-a and phycocyanin concentrations in inland temperate lakes across new York state using sentinel-2 images: application of Google Earth engine for efficient satellite image processing." Remote Sensing 16, no. 18 (2024): 3504.

- Mishra, S., & Mishra, D. R. (2012). Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sensing of Environment, 117, 394-406. [CrossRef]

- Kolli, Meena Kumari, and Pennan Chinnasamy. "Estimating turbidity concentrations in highly dynamic rivers using Sentinel-2 imagery in Google Earth Engine: Case study of the Godavari River, India." Environmental Science and Pollution Research 31, no. 23 (2024): 33837-33847. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J., Guo, R., Zhang, Y., Xu, L., Zhong, S., Dong, Y., & Li, X. (2021). Analysis of automatic monitoring data of total phosphorus in drinking water source in east Taihu Lake based on improved extreme learning machine algorithm. Chinese Journal of Environmental Engineering, 15(6), 2165–2173.

- Qin, Haoming, Chong Fang, Ge Liu, Kaishan Song, Zhuoshi Li, Sijia Li, Hui Tao, and Zhaojiang Yan. "Temperature Is a Key Factor Affecting Total Phosphorus and Total Nitrogen Concentrations in Northeastern Lakes Based on Sentinel-2 Images and Machine Learning Methods." Remote Sensing 17, no. 2 (2025): 267. [CrossRef]

- Rigaill, G. (2015). A pruned dynamic programming algorithm to recover the best segmentations with $1 $ to $ K_ {max} $ change-points. Journal de la société française de statistique, 156(4), 180-205.

- Truong, C., Oudre, L., & Vayatis, N. (2018). ruptures: change point detection in Python. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.00826.

- Yue, S., & Wang, C. (2004). The Mann-Kendall test modified by effective sample size to detect trend in serially correlated hydrological series. Water resources management, 18(3), 201-218. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., & Mahmud, I. (2019). pyMannKendall: a python package for non parametric Mann Kendall family of trend tests. Journal of open source software, 4(39), 1556. [CrossRef]

- Shenbagalakshmi, G., Shenbagarajan, A., Thavasi, S., Nayagam, M. G., & Venkatesh, R. (2023). Determination of water quality indicator using deep hierarchical cluster analysis. Urban Climate, 49, 101468. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yong-Hui, Feng Zhou, Huai-Cheng Guo, Hu Sheng, Hui Liu, Xu Dao, and Cheng-Jie He. "Analysis of spatial and temporal water pollution patterns in Lake Dianchi using multivariate statistical methods." Environmental monitoring and assessment 170, no. 1 (2010): 407-416. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. A., Al-Musawi, A. H., & Al-Ameri, S. B. (2021). Correlation of Water Quality with Microplastic Exposure Prevalence in Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). E3S Web of Conferences, 324, 03008.

- Feng, H., Yan, J., & Xia, J. (2020). Application of time series and multivariate statistical models for water quality assessment and pollution source apportionment in an Urban River, New Jersey, USA. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27, 30887–30902.

- Jaiswal, A., Kumar, A., Kumari, S., & Singh, R. K. (2022). Trend Analysis on Water Quality Index Using the Least Squares Regression Models. Environment and Ecology Research, 10(5), 561-571.

- Friedman, J. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction. (No Title).

- Ward Jr, J. H. (1963). Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American statistical association, 58(301), 236-244on, 58(301), 236-244.

- Rousseeuw, P. J. (1987). Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of computational and applied mathematics, 20, 53-65. [CrossRef]

- Davies, D. L., & Bouldin, D. W. (1979). A cluster separation measure. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, (2), 224-227.

- Schölkopf, B., Smola, A., & Müller, K. R. (1998). Nonlinear component analysis as a kernel eigenvalue problem. Neural computation, 10(5), 1299-1319. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yubo, Tao Yu, Bingliang Hu, Zhoufeng Zhang, Yuyang Liu, Xiao Liu, Hong Liu, Jiacheng Liu, Xueji Wang, and Shuyao Song. "Retrieval of water quality parameters based on near-surface remote sensing and machine learning algorithm." Remote Sensing 14, no. 21 (2022): 5305. [CrossRef]

| Band Name |

Band Number |

Band Description |

Central Wavelength (nm) |

Spatial Resolution (m) |

| B1 | Band 1 | Coastal aerosol | 443 | 60 |

| B2 | Band 2 | Blue | 490 | 10 |

| B3 | Band 3 | Green | 560 | 10 |

| B4 | Band 4 | Red | 665 | 10 |

| B5 | Band 5 | Red edge 1 | 705 | 20 |

| B6 | Band 6 | Red edge 2 | 740 | 20 |

| B7 | Band 7 | Red edge 3 | 783 | 20 |

| B8 | Band 8 | NIR (Near-Infrared) | 842 | 10 |

| B8A | Band 8A | Narrow NIR | 865 | 20 |

| B9 | Band 9 | Water vapor | 945 | 60 |

| B11 | Band 11 | SWIR 1 (Short-Wave Infrared) | 1610 | 20 |

| B12 | Band 12 | SWIR 2 | 2190 | 20 |

| QA60 | - | Cloud mask bitmask | - | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).