1. Introduction

Venomous snakebites constitute a major global public health concern, with consequences ranging from immediate local effects to severe systemic complications [

1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), snakebite envenomation is a global health priority, especially in areas with the highest incidence rates, primarily among rural populations in tropical and subtropical regions [

2,

3]. Recent estimates suggest that snakebite affects approximately 1.8 million persons each year, leading to approximately 94,000 fatalities every year [

4,

5]. This massive burden is further compounded by the complex interplay among ecological, socioeconomic, and human factors that affect the frequency of such events [

5,

6].

Beyond the immediate danger posed by venom, secondary infections post-envenomation, such as cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis, represent significant complications that can exacerbate patient morbidity [

7,

8]. Although some snake venoms have antibacterial qualities, venomous snakes' oral microbiota can increase the risk of serious infections after tissue damage [

9]. Studies reveal that bacterial infections after snakebite frequently require surgery and can cause permanent impairments for those who suffer from them [

10,

11]. These insights underline the urgency of addressing snakebite as a public health issue with multifaceted implications.

While snake venoms generally possess some antibacterial properties [

12], the actual risks associated with the oral flora of snakes have gained attention in recent years. There is evidence that bacteriological profiles of snakebite wounds frequently contain both contaminants and possibly snake salivary microbiome-derived pathogens [

9].

Morganella morganii, for example, is among the most frequent isolates from infected wounds, with the implication being that comprehensive microbiological evaluations are required in snakebite wound management [

9].

There is a paradigm shift from culture-based to culture-independent approaches in the development of approaches to investigate the oral microbiota of venomous snakes. Traditional microbiological culture-based methods formed the basis of early research but were constrained by special growth requirements that can suppress the growth of certain microbiota [

13]. The whole range of microbial life in snake mouths can now be explored using methods like next-generation sequencing (NGS) without the constraints of culturing because of paradigm shifts introduced by molecular biology innovations [

9,

12]. These sophisticated approaches provide a better understanding of the interconnection between snake venoms, oral bacteria, and possible post-envenomation complications.

The shift to culture-independent methodologies represents a broader trend in microbiological research aimed at unraveling complex microbial communities and their pathophysiological roles [

14]. Through high-throughput sequencing techniques, researchers are now able to decode not only the composition of oral microbiota but also how these communities interact with snake venoms during envenomation events [

12]. Furthermore, insights gained from this research may guide clinical practices for managing snakebite-related infections and lead to improved outcomes for victims.

The WHO's strategic campaign to mitigate morbidity and mortality from snakebites describes the rendrance of snakebite envenomation as a global health issue [

14]. The overall strategy included within the WHO framework focuses on educational improvements among healthcare providers and community members. Increased education and training can result in quicker and more efficient reactions to snakebite, which will reduce the risks of infection and venom in the future [

11,

14].

In addition, the psychological effects of snakebite accidents cannot be downplayed; studies show victims developing long-term mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression [

4,

15]. The psychological impact is usually aggravated by physical disabilities stemming from complications such as amputations or any other grave injuries [

15]. Snakebite cases must thus be treated multimodally in consideration of psychological as well as physiological complications.

Following the development of culture-independent to culture-dependent methods for characterizing the oral microbiota of venomous snakes, this review aims to demonstrate the transformative power of next-generation sequencing technologies in expanding our knowledge of these intricate microbial communities. Culture-based methods, although old in creating early microbiological knowledge, have been hindered by their inability to capture all microbial diversity due to the high cultivation requirements and dominance of fast growers. The advent of molecular techniques, particularly 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics, has revolutionized our capacity for characterizing oral microbiota in its entirety, with culture-independent methods being capable of detecting much greater numbers of bacterial taxa than their culture-dependent counterparts.

2. Snakebite Complications and the Role of Oral Microbiota

Since there is a high rate of secondary infections due to bacteria entering the wound, the complications that arise from snakebite envenomation are a point of worry in treating the affected individuals. One of the most frequent outcomes following snakebite is secondary infection, particularly those caused by the genus

Bothrops, with the proteolytic effect of venom creating an environment conducive to bacterial development [

16]. Such infections, with a wide variety of pathogenic bacteria taking advantage of the tissue damage induced by the venom, can result in serious morbidity [

9,

17].

Snake venom also causes severe tissue damage on a pathophysiological level, and thus, the clinical presentation of envenoming becomes even more challenging. Most toxins that are brought by the venom induce necrosis, inflammation, and an interference in normal tissue integrity that allows for colonization and infection by bacteria [

18]. Interestingly, conditions like localized edema and increased vascular permeability contribute to the proliferation of bacterial pathogens that are usually inoculated by the snake's mouth [

19]. Once tissue damage brought about by venom and snake oral flora are compounded together, it can cause severe localized infection like necrotizing fasciitis and cellulitis that necessitates immediate medical attention [

19].

Numerous microbial species are implicated in secondary infections of snakebite wounds, according to epidemiological data on infections caused by snake oral flora. Research has indicated that infected bite wounds frequently harbor oral bacteria, including members of the

Enterobacter and

Proteus genera,

Morganella morganii, and

Aeromonas hydrophila [

20,

21]. Research demonstrating that these organisms can be isolated not only from the wound site but also directly from the snake's oral cavity highlights the significance of these bacteria and suggests a direct link between the microbial flora of the snake and infections that humans face after being envenomated [

22]. These results highlight the vital need for efficient wound care procedures that take into account both the venom's immediate effects and the risk of infection from bacterial colonization.

In-depth analyses of infections caused by snakebite show that a wide variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative species can be found in the wound microbiota. For example, studies of the oral microbiota of snakes have revealed the presence of several pathogenic bacteria, such as

Clostridium and

Staphylococcus aureus, as well as several other bacteria that are known to contribute to infections, including coagulase-negative staphylococci and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

22,

23]. Because dietary choices can affect the microbial composition, additional classifications have revealed that the specific bacterial load in the oral cavity varies between snake species and their environments [

24].

It is still difficult to monitor and control infection after snakebite attacks, particularly in the tropics, where resources could be scarce. Although advice differs with prevailing local vegetation, empirical antibiotic treatment is usually a component of present-day therapy in trying to cover a broad spectrum of likely infecting organisms [

25,

26]. Recent research made particular emphasis on the inefficacy of preemptive antibiotics against different local bacterial strains and their corresponding patterns of resistance [

27]. This suggests the necessity of localized treatment guidelines and protocols, specifically those structured around regional snake populations' microbiome.

These results are definite proof that enhancing the clinical outcomes relies on understanding the constitution and function of the oral microbiota of snakes in envenomation cases. Understanding the nature of bacteria present can guide the use of the right antibiotics in improving the management of secondary infections [

18,

28]. In a bid to improve prevention and treatment practices and to ensure that patients are provided with timely and effective care so that venom toxicity as well as resultant infection is reduced, future studies targeting the establishment of the entire microbial profiles related to snakebite wounds shall be crucial.

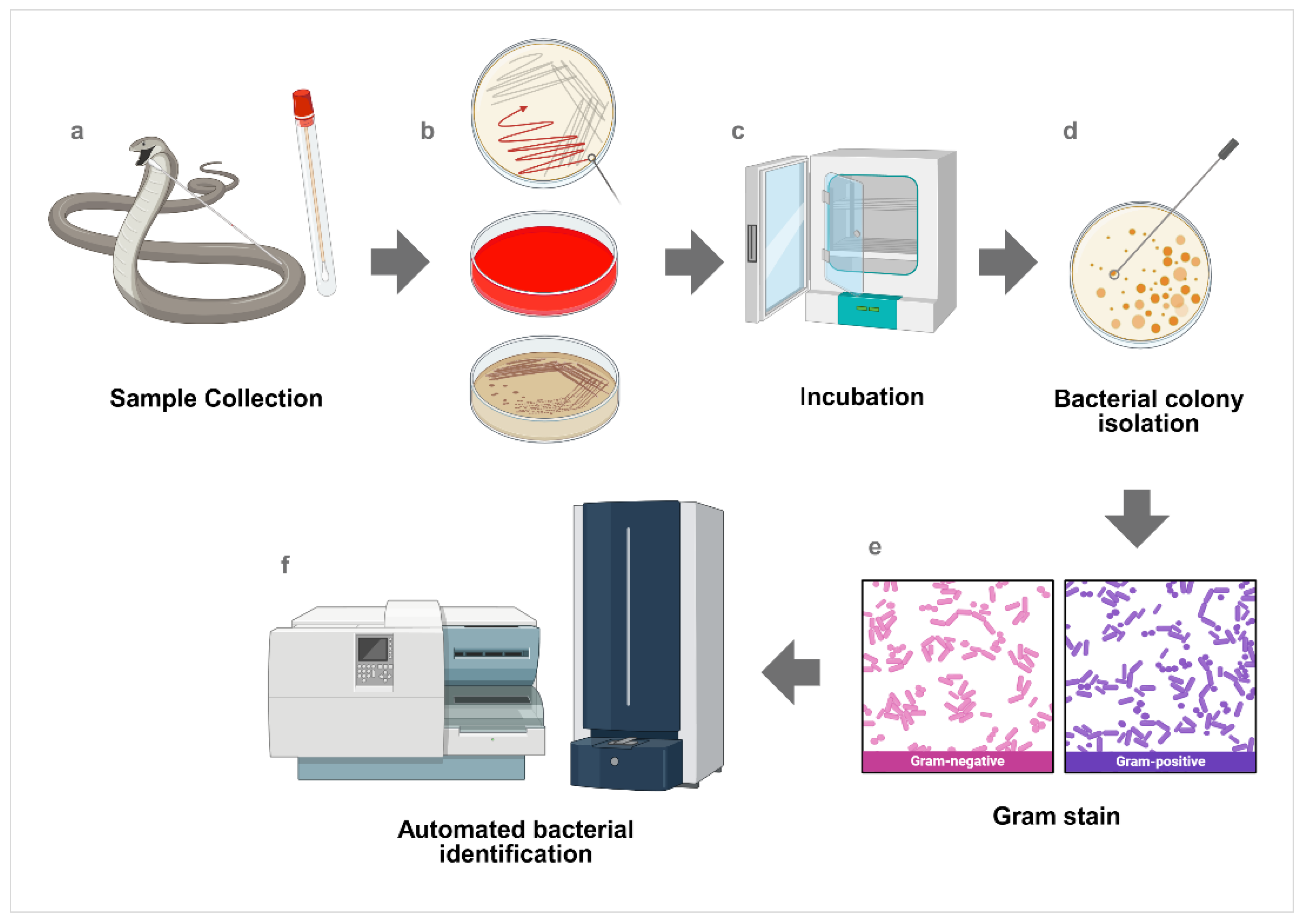

3. Early Studies Using Culture-Dependent Methods

Initial research with culture-dependent methods has yielded immense information on microbial populations of snakebite infection. However, these methods have significant weaknesses with serious limitations that are critical to bias the accuracy and completeness of estimates of microbial diversity. One of the most significant limitations of traditional culture methods is perhaps a low resolution of microbial diversity (

Figure 1). Typically, culture-based techniques isolate only a minuscule percentage, usually cited at 1-10%, of the total microbial variety that exists within an ecosystem, and in challenging ones like infected tissue following a snakebite, where several various bacterial groups coexist but few are identifiable using culturing [

29].

The second fundamental deficiency of culture-based approaches lies in their inbuilt prejudice in favor of aerobic and fast-growing strains. Culture media and conditions employed are generally optimized for specific populations of bacteria that are unrepresentative of the real diversity present in nature. Most of the pathogenic bacteria that cause snakebite are anaerobes or slow growers, hence easily overlooked under standard culture conditions [

30]. This selectivity will lead to significant underrepresentation of such important pathogens as

Morganella morganii,

Providencia sp., and

Aeromonas hydrophila, which most frequently have been isolated from infected wounds and are causative agents of severe post-envenomation complications [

29].

Detection of such genera as

Morganella and

Aeromonas holds significance because it can have the potential to directly inform empirical antibiotic therapy regimens so that healthcare workers may specifically target offending pathogens. Further, awareness of the existing bacterial community may also influence surgical decision-making and management of complications such as necrotizing fasciitis [

31].

Regarding antivenom production, insights from microbial research stress the need for rigorous microbiological investigation. Since antivenoms are designed to counteract the toxic action of snake venoms, they must also be designed to compensate for the possibility of secondary bacterial infection that might complicate the clinical condition of patients. Bacterial population resistance genes could influence treatment efficacy and necessitate multi-target strategies in antivenom formulation [

32,

33]. By bridging the cultural gap between cultured and uncultured populations, researchers gain the capability to provide a stronger perspective on the pathophysiological world in which patients live, leading to better healthcare strategies and formulations.

4. Transition to Molecular and Culture-Independent Techniques

The transition from conventional culture-dependent techniques to culture-independent (molecular techniques) is a big leap in the study of microbial diversity, particularly in infectious complications due to snakebites. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing of 16S rRNA gene fragments have been crucial in the discovery of molecular methods through which scientists can detect and identify bacteria that were previously unable to be cultivated in the laboratory setting. Sanger sequencing facilitated the amplification and sequencing of specific fragments of the 16S rRNA gene, which explained the structure of microbial communities in a variety of environments, like infected snakebite wounds [

34,

35]. The method has provided the specific taxa present in these samples and established a foundation for the understanding of bacterial infection dynamics.

However, both PCR and Sanger sequencing are constrained in that they do not sequence the entire 16S rRNA gene economically and relatively lack resolution for differentiating between closely related bacteria. Later, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies supplied remedies with the capacity to sequence numerous samples in parallel at high throughput. NGS has transformed microbial ecology through the ability to sequence longer amplicons and deeper coverage of microbial diversity, hence solving issues encountered with traditional sequencing methods [

36].

Specifically noted is the use of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing of the targeted hypervariable regions, such as V3–V4 (

Figure 2). These are significant when it comes to taxonomic classification and are most widely used in microbiome studies. By applying a two-step PCR method and leveraging high-throughput sequencing technologies, researchers can amplify and sequence such regions to obtain fine-grained insights into microbial diversity among varying samples, e.g., snakebite wounds [

34,

37]. Sequencing data can be interpreted using alternative frameworks, namely amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or operational taxonomic units (OTUs). ASVs, or unique sequences at single-nucleotide resolution, have better resolution for classification than OTUs, which cluster sequences by similarity and can lead to oversimplification or loss of some taxonomic information [

38,

39].

It has advantages in having increased higher taxonomic resolution, in which discrimination among closely related bacterial species that might be clumped together in classical culture-based studies can be made. For example, functional amplification and sequencing of the whole 16S rRNA gene can facilitate differentiation at the species level, providing more insight into the complexities in microbial infections ensuing from snakebites [

40,

41]. In addition, examination of the whole gene might provide leeway for debating functional niches of specific microbial taxa, and these can inform treatment protocols and clinical care strategies.

With such high taxonomic resolution, the capacity to detect rare and previously uncultivated species, and the comprehensive scale of NGS, microbial ecology in the context of snakebite disease is radically expanded. With such knowledge being of vital importance for clinical application, where familiarity with pathogenic organisms affected can guide antibiotic therapy and intervention strategies following envenoming, such a discovery has broad implications. Furthermore, microbiome analysis can support safer and more efficient antivenom treatment through the identification of how the bacterial infection could interact with venom components and impact patient results [

42,

43].

5. Current Advances: Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Metagenomics

Recent studies involving next-generation sequencing techniques have identified bacterial communities of venomous snakes' oral cavities and the venoms more accurately. It has been particularly characterized by shotgun metagenomics and full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing as powerful techniques that more clearly focus on the complex processes of such ecosystems.

The advances in the long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), have enabled researchers to conduct full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing. This would allow researchers to sequence the entire gene, achieving better resolution in microbial taxonomic identification. For example, in Lin et al.'s work in 2023, the authors used high-throughput sequencing to explore the oral microbiota of certain species of venomous snakes by sequencing and amplifying the full-length 16S rRNA gene, including hypervariable regions V1-V9. Rich microbial diversity was observed, which was responsible for the ecological roles of these bacteria within the snakes' environments [

28].

It has been recently demonstrated that complete sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is essential when it comes to the discrimination of closely related taxa, which may not be distinguishable when one considers only the V3-V4 regions typical of shorter-read strategies. The use of this technology allows for higher-scale ecological and phylogenetic assessments, hence expanding our understanding of the microbiome assemblies associated with various species of snakes.

Current research describes the dominant microbial phyla of the oral and fecal microbiota of snakes, such as Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Fusobacteria [

44,

45]. The fecal microbiota of the Red Back Pine Root Snake (

Oligodon formosanus) and Chinese Slug-Eating Snake (

Pareas chinensis) have been specifically characterized, with research describing these dominant phyla and reporting significant differences in the composition of the microbiome between these two species, suggesting ecological and evolutionary adaptation [

44]. Further investigation shows how ecological conditions may influence microbiome variation between species [

45].

Shotgun metagenomics has been revolutionary, allowing not only for deep taxonomic profiling but also for functional characterization of microbial communities through the detection of genes implicated in specific metabolic pathways. The technique allows researchers to build a picture of the functional diversity of microbial populations, something that has been central to host-microbiota interaction studies. For instance, the important metabolic potential of oral microbes that would impact the overall health of the snake host has been described [

46].

In addition, the application of shotgun metagenomics in studies concerning reptilian oral microbiomes has provided additional knowledge regarding pathogenic potential and resilience of the communities. Current studies have identified specific pathogens within such microbiotic communities, showing complexities linked to their ecological niches [

6]. The studies are fundamental since they not only document the microbial diversity but also establish connections to potential health effects due to microbiome dysbiosis in snakes.

Moreover, recent advances have emphasized the application of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing, allowing for more accurate determination of phylogenetic relationships among bacterial populations. Investigation through high-throughput sequencing has revealed the phylogenetic diversity of Taiwanese venomous snake species' oral microbiota, allowing for subtle determination of the effect of evolutionary pressures on microbial populations. They emphasized the need for more advanced approaches to determine the complete taxonomic breadth of the oral microbiome [

28].

These advanced methods hold colossal implications, particularly in light of emerging zoonotic pathogens. Through the discovery of the microbial interactions within the snake's oral cavity, researchers can develop an understanding of the potential reservoirs of pathogenic microbes, with the possibility of impacting not just snake health but also broader ecological processes. Snake oral cavity bacteria can serve as a reservoir for the spread of antibiotic resistance, demonstrating the public health significance of snake microbiome studies [

47]

Furthermore, the exploration of dietary correlates with metagenomic research has identified how specific feeding habits determine oral microbiota structure in snakes [

48]. This resolves fundamental questions concerning diet interaction with microbial ecology, where specific dietary specialization can enhance microbial taxa development that facilitates adaptability to their environments.

6. Microbiota-Host-Venom Interactions and Ecological Considerations

The complex interactions between the microbiota, host species, and venom in reptiles, and most notably in venomous snakes, provide a captivating window to study ecological interactions, evolutionary stress, and health impacts. The newer studies employing newer sequencing methods like full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics have elucidated the effects of captivity, diet, and environmental parameters on microbial populations.

The composition of the gut microbiota is responsive to a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including captivity conditions, diet, and habitat quality. It has been found by research that captivity has a great impact on the gut microbiota of most species, leading to lower diversity and richness compared to the equivalent in the wild (

Figure 3). For instance, research concluded that the intestinal bacterial community of the red-crowned crane was very dissimilar under captive and semi-free-range circumstances due to diet and habitat divergence [

49]. This shows captivity is not only crucial for microbial diversity but also for host health and ecological adaptability.

Similarly, extreme variations in microbial diversity and function have been reported in captive alpine musk deer versus their free animals, demonstrating the extent to which captivity conditions and dietary supplies may fundamentally alter the gut microbiome [

50].

The host genus's role on gut microbiota has also been highlighted, demonstrating that there are unique microbial signatures to different primate species, as a result of diet and being captive [

51]. The presence of venom in snakes may exert selective pressure upon co-occurring microbial communities. The action of venom on bacterial communities is particularly intriguing because venom components not only act upon prey but also upon the viability and even structure of microbes that colonize the snake's oral cavity.

Environmental stresses like venom profile and diet might have significant effects on microbial resistance profiles of snakes [

52,

53]. The dynamic interaction between venom and microbiota can lead to the creation of new resistant strains—either through natural selection or horizontal gene transfer—potentially enabling these bacteria to grow in extreme conditions. Furthermore, the identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in snake-associated microbiota has been highlighted as a priority area of research. Major studies have shed light on the idea that the recognition of microbial resistance mechanisms could reveal new bioactive compounds that will offer insights into the design of novel antibiotics or therapeutic agents [

54]. As venom is toxic to or suppresses the majority of bacterial species, survivors may possess unique resistance characteristics or beneficial interactions with the host.

The information learned by shotgun metagenomics not only aids researchers in profiling microbial communities but also in finding functional genes that confer antimicrobial resistance or other bioactivities. These technologies enable one to interrogate microbial functions at higher resolution, capturing valuable genetic information on potential antimicrobial compounds that can be harnessed for use in human health [

55].

For example, gut microbiome research in venomous snakes can identify new biosynthetic gene clusters that are responsible for the synthesis of new antimicrobial compounds. Such information can be very beneficial in pharmaceutical leads, especially with growing antibiotic resistance [

56]. Venomous snake venoms and microbiota evolved together to form a biological niche rich with unexploited potential for bioprospecting [

57].

7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

The research on oral microbiota across different species, particularly in tropical and subtropical ecosystems, indicates substantial knowledge gaps, including for venomous snakes and the ecological environments they inhabit. Although there have been improvements in methods used in microbiome studies, including shotgun metagenomics and full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing, sampling and analysis of tropical species and areas continue to be underrepresented, contributing to a biased view of global microbiome diversity. The research that has been conducted focuses on reporting a substantial bias towards temperate ecosystems, with comparatively few studies aiming to target the microbial assemblages of tropical animals, such as reptiles like snakes [

58,

59,

60]. The gap in extensive genomic profiling across tropical ecosystems continues, as research has also pointed out that many tropical freshwater environments continue to be inadequately described [

58].

The underrepresentation of tropical species is a prominent gap in microbiome research since these environments support high levels of biodiversity and specialized ecological processes. For instance, tropical environments such as caves or montane forests are often undersampled, potentially leading to significant microbiomes with important insights on microbial ecology and evolution at the global level to be overlooked [

59,

60]. This demographic and ecological sampling bias has consequences both for our understanding of tropical ecosystems themselves, as well as for the interpretation of microbial interactions and their impacts on host organisms within these regions.

Additionally, methodological discrepancies represent another obstacle to expanding our knowledge on reptilian microbiomes, particularly regarding standardization. It is critical that sampling, sequencing, and processing procedures are consistent because differences can result in significantly disparate findings. For instance, variation in DNA extraction procedures or library preparation steps can notably affect the observed microbial assemblages, making replication studies or comparison of results across studies challenging [

61,

62]. Protocol standardization helps generate reproducible information and promotes comparative research, leading to more expansive ecological conclusions.

There is an urgent need for integrated research connecting microbiota and venomomics to clinical outcomes. The potential relationship between the snake's oral microbiome and venom composition is extremely understudied. The oral microbiota, according to some researchers, could have implications for the efficacy, potency, and composition of snake venoms because the microbial community would metabolically interact with venom molecules or influence the ecological roles of venoms in prey immobilization or defense [

63,

64]. Clarification of these relationships would illuminate new avenues of research investigating ecological processes and implications for envenomation and therapeutic strategies in humans who are bitten by snakes.

It is argued that specific pathways are needed to bring together these areas of research, with a focus on a multidisciplinary melding of microbiology, zoology, and medicine. This is especially applicable within the tropics, where the range of venomous species tends to outstrip current medical understanding of their impact on human health [

63]. In addition, as environmental shifts like climate change may have an impact on microbial interactions and species ranges, an understanding of these processes will be essential in forecasting ecological changes of the future and their implications for human health [

65].

The promise of integrating venomomics and microbiota studies can be part of creating a comprehensive model of snake biology within their ecological niches. Investigation of the potential roles of the microbiome in enhancing or diminishing venom effectiveness can provide insight into how these creatures thrive and survive in their habitats [

64]. Public health significance, particularly in snakebite-endemic regions where the condition remains largely untreated because of a lack of knowledge and means of effective antivenom strategies, should likewise be prioritized by scientists.

With these gaps in existing research, future studies must emphasize the characterization of tropical species and incorporate methodological standardizations to allow for multifaceted studies of the microbiomes of these ecosystems. The concerted effort to study ecological interactions using an integrated approach will elucidate the functions of microbiota in reptile biology and inform broader ecological and conservation objectives in tropical biodiverse environments.

8. Conclusions

The most important advancement in microbial ecology is the transition from culture-dependent to culture-independent methods. The conventional culture-dependent methods, though among the leaders during the initial periods of microbiological studies, are beset with deficiencies that make them grossly inadequate. The conventional methods can cultivate merely 1% of recoverable microbial diversity in the habitat from samples, thus resulting in the "great plate count anomaly."

Molecular techniques, 16S rRNA gene sequencing in particular, revolutionized microbial ecology with the potential of culture-independent examination of complex microbial communities. The 16S rRNA gene is a great molecular marker since it occurs in all prokaryotes, is evolutionarily conserved, yet contains hypervariable regions for species discrimination. The revolution was also fueled by the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies that provided unprecedented analysis depth and throughput. NGS platforms enabled researchers to sequence millions of bacterial 16S rRNA genes in parallel and reveal the true diversity and complexity of microbial communities.

The most recent quantum leap has been shotgun metagenomics, which sequences all the genomic material in an untargeted sample. This not only provides a comprehensive taxonomic profile but also characterizes the functional genetic potential of microbial communities, such as antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors, and metabolic pathways. Application of molecular ecology techniques to characterize snake oral microbiota is now a fundamental component of modern snakebite treatment. Secondary bacterial infection is one of the most serious complications of envenoming following snakebite.

The therapeutic significance of oral microbiota profiling by deep oral microbiota profiling directly addresses therapeutic selection and patient outcome. Establishment of region-specific antibiotic regimens based on molecular profiling data is one of the greatest advancements in the treatment of snakebite. It has been found through studies that Gram-negative bacteria in the oral fauna of snakes have evolved reduced susceptibility to first- and second-generation cephalosporins.

The shift from classical microbiology to molecular ecology has transformed our understanding of snakebite envenomation's microbial communities. Culture-independent techniques have revealed the true complexity and diversity of oral snake microbiota, permitting evidence-based therapy for secondary infection.

Funding

“This review received no external funding”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| rRNA |

ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid |

| ASVs |

Amplicon Sequence Variants |

| OTUs |

Operational Taxonomic Units |

| PacBio |

Pacific Biosciences |

References

- Mark Valencia B, Zavaleta A. La medicina complementaria en el tratamiento de las enfermedades tropicales desatendidas: accidentes ofídicos. Rev Peru Med Integr [Internet]. 2017 Jul 18;2(1):58–67. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Koudou GB, Bagot M, Drabo F, Bougma WR, Pulford C, et al. Health and economic burden estimates of snakebite management upon health facilities in three regions of southern Burkina Faso. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2021 Jun;15(6):e0009464. [CrossRef]

- Kaulgud RS, Hasan T, Astagimath M, Vanti GL, Veeresh S, Kurjogi MM, et al. Nucleotidase as a Clinical Prognostic Marker in snakebites: A prospective study. Indian J Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2025 Feb;29(2):125–9. [CrossRef]

- Williams SS, Wijesinghe CA, Jayamanne SF, Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Lalloo DG, et al. Delayed psychological morbidity associated with snakebite envenoming. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2011 Aug;5(8):e1255. [CrossRef]

- Martín G, Erinjery JJ, Ediriweera D, de Silva HJ, Lalloo DG, Iwamura T, et al. A mechanistic model of snakebite as a zoonosis: Envenoming incidence is driven by snake ecology, socioeconomics and its impacts on snakes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2022 May;16(5):e0009867. [CrossRef]

- Martin G, Erinjery J, Ediriweera D, de Silva HJ, Lalloo DG, Iwamura T, et al. Redefining snakebite envenoming as a zoonosis: disease incidence is driven by snake ecology, socioeconomics and anthropogenic impacts [Internet]. bioRxiv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Essafti M, Fajri M, Rahmani C, Abdelaziz S, Mouaffak Y, Younous S. Snakebite envenomation in children: An ongoing burden in Morocco. Ann Med Surg (Lond) [Internet]. 2022 May;77(103574):103574. [CrossRef]

- Huang LW, Wang JD, Huang JA, Hu SY, Wang LM, Tsan YT. Wound infections secondary to snakebite in central Taiwan. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2012;18(3):272–6. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Aldana DK, Bonilla-Aldana JL, Ulloque-Badaracco JR, Al-Kassab-Córdova A, Hernandez-Bustamante EA, Alarcon-Braga EA, et al. Snakebite-associated infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2024 May 1;110(5):874–86. [CrossRef]

- Muhammed A, Dalhat MM, Joseph BO, Ahmed A, Nguku P, Poggensee G, et al. Predictors of depression among patients receiving treatment for snakebite in General Hospital, Kaltungo, Gombe State, Nigeria: August 2015. Int J Ment Health Syst [Internet]. 2017 Apr 13;11(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Kinda R, Sidibe S, Zongo D, Millogo T, Delamou A, Kouanda S. Factors associated with complications of snakebite envenomation in health facilities in the Cascades region of Burkina Faso, 2016 to 2021 [Internet]. Preprints. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wagener M, Naidoo M, Aldous C. Wound infection secondary to snakebite. S Afr Med J [Internet]. 2017 Mar 29;107(4):315–9. [CrossRef]

- Maduwage K, Isbister GK. Current treatment for venom-induced consumption coagulopathy resulting from snakebite. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2014 Oct;8(10):e3220. [CrossRef]

- Chippaux JP, Massougbodji A, Habib AG. The WHO strategy for prevention and control of snakebite envenoming: a sub-Saharan Africa plan. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2019 Dec 2;25:e20190083. [CrossRef]

- Aglanu LM, Amuasi JH, Schut BA, Steinhorst J, Beyuo A, Dari CD, et al. What the snake leaves in its wake: Functional limitations and disabilities among snakebite victims in Ghanaian communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2022 May;16(5):e0010322. [CrossRef]

- Soares Coriolano Coutinho JV, Fraga Guimarães T, Borges Valente B, Gomes Martins de Moura Tomich L. Epidemiology of secondary infection after snakebites in center-west Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2023 Mar;17(3):e0011167. [CrossRef]

- Javier RM, Safitri LS, Rialdi AF, Handika E, Limanto EJ, Prakoso B, et al. Effect of snakebite on osteomyelitis and Cardiac shock in Pediatric and Adult Patients. Journal of Social Research [Internet]. 2023 Mar 7;2(4):1079–85. [CrossRef]

- Résière D, Olive C, Kallel H, Cabié A, Névière R, Mégarbane B, et al. Oral Microbiota of the snake Bothrops lanceolatus in Martinique. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Sep 27;15(10):2122. [CrossRef]

- Smith LK, Vardanega J, Smith S, White J, Little M, Hanson J. The incidence of infection complicating snakebites in tropical Australia: Implications for clinical management and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Trop Med [Internet]. 2023 Oct 12;2023:5812766. [CrossRef]

- Paul A, Joseph JJ, Saijan S, Sebastian S, Tom AA, Iqbal T. Unveiling the potential threat of bacterial oral flora of snake in snake bite envenomation: A case report. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md) [Internet]. 2021 May;29(3):e184–5. [CrossRef]

- Chuang PC, Lin WH, Chen YC, Chien CC, Chiu IM, Tsai TS. Oral bacteria and their antibiotic susceptibilities in Taiwanese venomous snakes. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2022 Apr 30;10(5):951. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani R, Sharif MR, Moniri R, Sharif A, Kashani HH. The identification of bacterial flora in oral cavity of snakes. Comp Clin Path [Internet]. 2016 Mar;25(2):279–83. [CrossRef]

- Brenes-Chacon H, Gutiérrez JM, Avila-Aguero ML. Use of antibiotics following snakebite in the era of antimicrobial stewardship. Toxins (Basel) [Internet]. 2024 Jan 11;16(1). [CrossRef]

- Mao YC, Chuang HN, Shih CH, Hsieh HH, Jiang YH, Chiang LC, et al. An investigation of conventional microbial culture for the Naja atra bite wound, and the comparison between culture-based 16S Sanger sequencing and 16S metagenomics of the snake oropharyngeal bacterial microbiota. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2021 Apr;15(4):e0009331. [CrossRef]

- Lin JH, Sung WC, Mu HW, Hung DZ. Local cytotoxic effects in cobra envenoming: A pilot study. Toxins (Basel) [Internet]. 2022 Feb 7;14(2):122. [CrossRef]

- Sachett JAG, da Silva IM, Alves EC, Oliveira SS, Sampaio VS, do Vale FF, et al. Poor efficacy of preemptive amoxicillin clavulanate for preventing secondary infection from Bothrops snakebites in the Brazilian Amazon: A randomized controlled clinical trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2017 Jul;11(7):e0005745. [CrossRef]

- Artavia-León A, Romero-Guerrero A, Sancho-Blanco C, Rojas N, Umaña-Castro R. Diversity of aerobic bacteria isolated from oral and cloacal cavities from free-living snakes species in Costa Rica Rainforest. Int Sch Res Notices [Internet]. 2017 Aug 20;2017:8934285. [CrossRef]

- Lin WH, Tsai TS. Comparisons of the oral Microbiota from seven species of wild venomous snakes in Taiwan using the high-throughput amplicon sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene. Biology (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 Sep 4;12(9). [CrossRef]

- Jackson CR, Randolph KC, Osborn SL, Tyler HL. Culture dependent and independent analysis of bacterial communities associated with commercial salad leaf vegetables. BMC Microbiol [Internet]. 2013 Dec 1;13:274. [CrossRef]

- McNab E, Benedetto D, Hsiang T. The creeping bentgrass microbiome: Traditional culturing and sequencing results compared with metagenomic techniques. Int Turfgrass Soc Res J [Internet]. 2022 Jun;14(1):911–5. [CrossRef]

- Ngo CT, Aujoulat F, Veas F, Jumas-Bilak E, Manguin S. Bacterial diversity associated with wild caught Anopheles mosquitoes from Dak Nong Province, Vietnam using culture and DNA fingerprint. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015 Mar 6;10(3):e0118634. [CrossRef]

- Demirci T, Oraç A, Aktaş K, Dertli E, Akyol I, Akın N. Comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent techniques in the detection of lactic acid bacteria biodiversity and dynamics throughout the ripening process: The case of Turkish artisanal Tulum cheese produced in the Anamur region. J Dairy Res [Internet]. 2021 Nov;88(4):445–51. [CrossRef]

- Yashiro E, Spear RN, McManus PS. Culture-dependent and culture-independent assessment of bacteria in the apple phyllosphere: Apple phyllosphere bacteria. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2011 May;110(5):1284–96. [CrossRef]

- Shin J, Lee S, Go MJ, Lee SY, Kim SC, Lee CH, et al. Analysis of the mouse gut microbiome using full-length 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2016 Jul 14;6:29681. [CrossRef]

- Graf J, Ledala N, Caimano MJ, Jackson E, Gratalo D, Fasulo D, et al. High-resolution differentiation of Enteric bacteria in premature infant fecal microbiomes using a novel rRNA amplicon. MBio [Internet]. 2021 Feb 16;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong BY, Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2019 Nov 6;10(1):5029. [CrossRef]

- Callahan BJ, Wong J, Heiner C, Oh S, Theriot CM, Gulati AS, et al. High-throughput amplicon sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene with single-nucleotide resolution. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. 2019 Oct 10;47(18):e103. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2007 Aug 15;73(16):5261–7. [CrossRef]

- Bao Z, Zhang B, Yao J, Li MD. MultiTax-human: an extensive and high-resolution human-related full-length 16S rRNA reference database and taxonomy. Microbiol Spectr [Internet]. 2025 Feb 4;13(2):e0131224. [CrossRef]

- Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2005 Mar;71(3):1501–6. [CrossRef]

- Komiya S, Matsuo Y, Nakagawa S, Morimoto Y, Kryukov K, Okada H, et al. MinION, a portable long-read sequencer, enables rapid vaginal microbiota analysis in a clinical setting. BMC Med Genomics [Internet]. 2022 Mar 25;15(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Cuscó A, Catozzi C, Viñes J, Sanchez A, Francino O. Microbiota profiling with long amplicons using Nanopore sequencing: full-length 16S rRNA gene and the 16S-ITS-23S of the rrn operon. F1000Res [Internet]. 2019 Aug 1;7:1755. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard AB, Tunsjø HS, Meisal R, Charnock C. A preliminary study on the potential of Nanopore MinION and Illumina MiSeq 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize building-dust microbiomes. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020 Feb 21;10(1):3209. [CrossRef]

- Cong X, Liu X, Zhou D, Xu Y, Liu J, Tong F. Characterization and comparison of the fecal bacterial microbiota in Red Back Pine Root Snake (Oligodon formosanus) and Chinese Slug-Eating Snake (Pareas chinensis). Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2025 Apr 16;16:1575405. [CrossRef]

- Smith SN, Colston TJ, Siler CD. Venomous snakes reveal ecological and phylogenetic factors influencing variation in gut and oral microbiomes. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2021 Mar 26;12:657754. [CrossRef]

- Bell SE, Nash AK, Zanghi BM, Otto CM, Perry EB. An assessment of the stability of the canine oral Microbiota after probiotic administration in healthy dogs over time. Front Vet Sci [Internet]. 2020 Sep 11;7:616. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Yang L, Zhang Y, Yang M, Li J, Fan Y, et al. Fecal and oral microbiome analysis of snakes from China reveals a novel natural emerging disease reservoir. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2023;14:1339188. [CrossRef]

- Du Y, Chen JQ, Liu Q, Fu JC, Lin CX, Lin LH, et al. Dietary correlates of oral and gut Microbiota in the water monitor lizard, Varanus salvator (Laurenti, 1768). Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2021;12:771527. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Wang H, Gao Z, Wang H, Zou H. Comparison of the intestinal bacterial communities between captive and semi-free-range red-crowned cranes (Grus japonensis) before reintroduction in Zhalong National Nature Reserve, China. Animals (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 Dec 19;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Song P, Liu D, Zhang J, Qin W, Wang H, et al. Marked variations in gut microbial diversity, functions, and disease risk between wild and captive alpine musk deer. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2023 Sep;107(17):5517–29. [CrossRef]

- Lan LY, You YY, Hong QX, Liu QX, Xu CZ, Chen W, et al. The gut microbiota of gibbons across host genus and captive site in China. Am J Primatol [Internet]. 2022 Mar;84(3):e23360. [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Song P, Wang H, Zhang J, Liu D, Cai Z, et al. Comparative analysis of gut microbial composition and potential functions in captive forest and alpine musk deer. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2022 Feb;106(3):1325–39. [CrossRef]

- Alberdi A, Martin Bideguren G, Aizpurua O. Diversity and compositional changes in the gut microbiota of wild and captive vertebrates: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021 Nov 22;11(1):22660. [CrossRef]

- Reese AT, Chadaideh KS, Diggins CE, Schell LD, Beckel M, Callahan P, et al. Effects of domestication on the gut microbiota parallel those of human industrialization. Elife [Internet]. 2021 Mar 23;10. [CrossRef]

- Houtz JL, Sanders JG, Denice A, Moeller AH. Predictable and host-species specific humanization of the gut microbiota in captive primates. Mol Ecol [Internet]. 2021 Aug;30(15):3677–87. [CrossRef]

- Bornbusch SL, Greene LK, Rahobilalaina S, Calkins S, Rothman RS, Clarke TA, et al. Gut microbiota of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) vary across natural and captive populations and correlate with environmental microbiota. Anim Microbiome [Internet]. 2022 Apr 28;4(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Yu J, Huan Z, Xu M, Song T, Yang R, et al. Comparing the gut microbiota of Sichuan golden monkeys across multiple captive and wild settings: roles of anthropogenic activities and host factors. BMC Genomics [Internet]. 2024 Feb 6;25(1):148. [CrossRef]

- Fadum JM, Borton MA, Daly RA, Wrighton KC, Hall EK. Dominant nitrogen metabolisms of a warm, seasonally anoxic freshwater ecosystem revealed using genome resolved metatranscriptomics. mSystems [Internet]. 2024 Feb 20;9(2):e0105923. [CrossRef]

- Paula CCP de, Sirová D, Sarmento H, Fernandes CC, Kishi LT, Bichuette ME, et al. FIRST REPORT OF HALOBACTERIA DOMINANCE IN A TROPICAL CAVE MICROBIOME [Internet]. bioRxiv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mota R, Vásquez-Aguilar AA, Hernández-Rodríguez D, Suárez-Domínguez EA, Krömer T. Close neighbors, not intruders: investigating the role of tank bromeliads in shaping faunal microbiomes. PeerJ [Internet]. 2025 May 9;13:e19376. [CrossRef]

- Safika S, Indrawati A, Afiff U, Hastuti YT, Zureni Z, Jati AP. First Study on profiling of gut microbiome in wild and captive Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii). Vet World [Internet]. 2023 Apr;16(4):717–27. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pato A, Sinha T, Gacesa R, Andreu-Sánchez S, Gois MFB, Gelderloos-Arends J, et al. Choice of DNA extraction method affects stool microbiome recovery and subsequent phenotypic association analyses. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2024 Feb 16;14(1):3911. [CrossRef]

- Deikumah JP, Biney RP, Awoonor-Williams JK, Gyakobo MK. Compendium of medically important snakes, venom activity and clinical presentations in Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2023 Jul;17(7):e0011050. [CrossRef]

- Kanika NH, Liaqat N, Chen H, Ke J, Lu G, Wang J, et al. Fish gut microbiome and its application in aquaculture and biological conservation. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2024;15:1521048. [CrossRef]

- Ostria-Hernández ML, Hernández-Zulueta J, Vargas-Ponce O, Díaz-Pérez L, Araya R, Rodríguez-Troncoso AP, et al. Core microbiome of corals Pocillopora damicornis and Pocillopora verrucosa in the northeastern tropical Pacific. Mar Ecol [Internet]. 2022 Dec;43(6). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).