1. Introduction

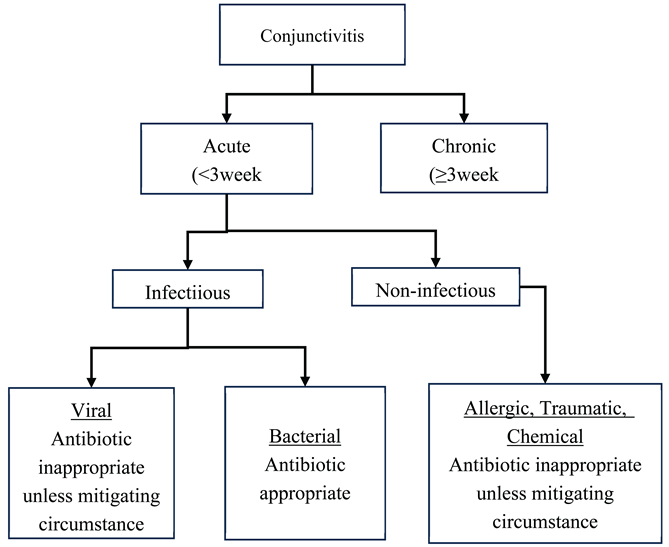

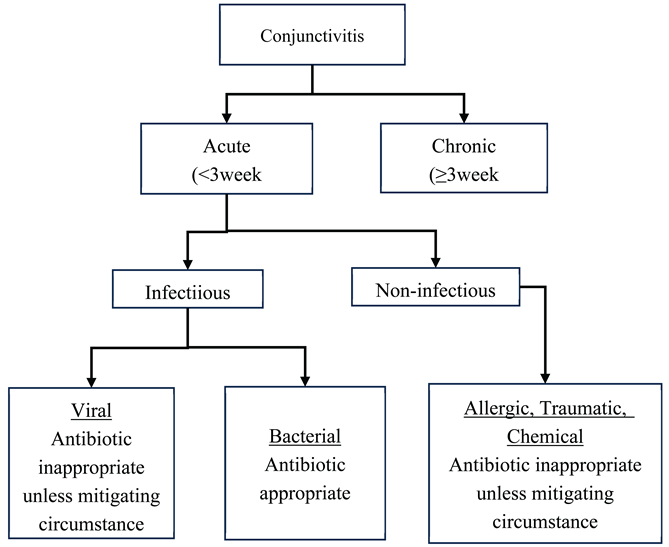

Conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the conjunctival tissue of the eye. Patients present with eyes that can be red, swollen and painful. Frequently there is also a mucoid discharge [

1,

2,

3]. The condition may be categorized as acute, chronic or recurrent based on the onset and nature of presentation [

3,

4,

5]. Acute conjunctivitis (AC) is commonly defined as conjunctivitis with symptoms of less than 3 weeks duration [

6,

7,

8]. It can further be categorized as non-infectious or infectious. Acute non-infectious conjunctivitis may be caused by trauma, chemical irritation or, most commonly, by allergies. Acute infectious conjunctivitis (AIC), has two main subcategories relating to the type of pathogen involved: bacterial AIC or viral AIC [

5,

6,

7,

9]. Due to the lack of specific diagnostic tests to differentiate bacterial from viral conjunctivitis, broad-spectrum antibiotics are frequently used to treat any infectious acute conjunctivitis [

7,

9]. However, bacterial and viral AIC can be distinguished by taking a thorough patient history and meticulous eye examination, and inappropriate antibiotic treatment could be avoided [

3,

7,

10]. A schematic of acute conjunctivitis categories and a diagnostic aid detailing signs and symptoms of allergic, bacterial and viral conjunctivitis are provided in

Supplementary Material.

Patients with AIC in Ghana may seek care in the community through pharmacies, through primary eye care facilities, or through referral hospitals. While primary eye care facilities are staffed solely by optometrists and ophthalmic nurses, referral hospitals also have ophthalmologists. The current first-line treatment of bacterial AIC in Ghana is with antibiotic eye drops and/or ointment [

11]. Treatment for viral AIC focuses on symptom relief unless there are mitigating circumstances that indicate antibiotic use, such as suspicion of secondary bacterial infection [

11]. Allergic (non-infectious) acute conjunctivitis is treated with mast cell stabilizers and antibiotics are not used unless there are similar mitigating circumstances as in viral AIC above. The antibiotics that are approved by the Ghana Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) for the treatment of bacterial AIC are Chloramphenicol 0.5% or Tetracycline 1% ointment, and Ciprofloxacin eye drops 0.3%.

Patients who return with unresolved symptoms of bacterial AIC usually move from chloramphenicol treatment through to treatment with ciprofloxacin (or alternative antibiotics) until the condition resolves.

There is a growing threat of antimicrobial resistance globally [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In Ghana, antibiotic resistance has been reported by different studies in health and environmental sciences [

16,

17,

18,

19]. It is therefore imperative to ensure that antibiotic prescribing is optimal as outlined in Global and National Action Plans on Antimicrobial use and Resistance to avert the burden of antimicrobial resistance on the health system [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Operational research, carried out through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT) and based on 2021 data, found the following antibiotic prescribing practices at the Bishop Ackon Memorial Christian Eye Centre (hereafter referred to as BAMCEC) [

24]:

29% of patients receiving antibiotics had been prescribed antibiotics inappropriately if the standard treatment guidelines were being followed

56% of patients receiving antibiotics were prescribed antibiotics from the WATCH category of the WHO AWaRe scheme and the remainder prescribed antibiotics from the ACCESS.

The AWaRe classification contains three groups of antibiotics (ACCESS, WATCH and RESERVE). The ACCESS category includes antibiotics for empirical treatment of common infections, which should be available in all health care settings. The WATCH category antibiotics have a higher potential for resistance and their use should be limited. The RESERVE category are “last resort” antibiotics and their use should be reserved for special situations with multidrug-resistant bacterial infections where alternative treatments have failed[

22,

25].

Following the research, the investigators produced information products, including evidence briefs, outlining why and how the research was conducted, the findings, and the implications for policy and practice. These provided the platform for a number of meetings with stakeholders convened between November 2022 and August 2023. The researchers proposed seven recommendations to address concerns identified during the study. Of these, four recommendations have been implemented:

To meet and brief the management of BAMCEC on the outcomes and implications of study.

To meet and brief the Head of Ghana Eye Care Secretariat on outcome and implications of study.

To meet and brief BAMCEC prescribers on outcome and implications of study.

To establish a Local Antibiotic Stewardship Team (LAST)

Three (3) recommendations are yet to be implemented (as of July 2025):

To monitor the use of antibiotics in the Eye Clinic by LAST

To conduct Continuing Professional Development (CPD) training related to antibiotic prescribing through the Drugs and Therapeutic Committee at BAMCEC

Replication of the study in other eye care facilities with the oversight of the Ghana Eye Care Secretariat

We considered the package of measures implemented above as an intervention.

We hypothesised that the operational research results dissemination and sensitisation will have improved the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing.

This study aimed to assess whether the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing improved, and the use of WATCH category antibiotics decreased, following the operational research and the associated research dissemination and sensitisation activities. We compared antibiotic prescribing patterns for acute conjunctivitis in two time periods, 1st January to 31st December 2021 (the period covered by the operational research) and 1st January to 31st December 2024 (following research results dissemination and training) in a specialist eye hospital in Cape Coast, Ghana.

The previous operational research only looked at patients who were being prescribed antibiotics and whether that was done appropriately. We, in addition, looked at patients with acute conjunctivitis who did NOT receive antibiotics and whether the withholding of antibiotics was appropriate. An attempt was made to collect baseline data on patients not receiving antibiotics in 2021 to be compared with data from 2024. However, not all treatment cards belonging to these patients could be obtained.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study was a cross-sectional, before and after, study using routinely available secondary data from electronic medical record system and supplemented with data from patient treatment cards.

2.2. Settings

2.2.1. General Setting

The study was conducted in Cape Coast, Ghana. Ghana is a West African country which shares borders with Burkina Faso to the north, Togo to the east, Cote d’Ivoire to the west and the Gulf of Guinea in the south. The population of the country was reported to be 30.8 million in the 2021 population and housing census [

26]. There are sixteen administrative regions in Ghana and Cape Coast is the capital of the central region.

2.2.2. Specific Setting

BAMCEC is a specialist hospital that offers eye care services to a wide range of patients in and around Cape Coast.

Most clients of the facility receive services with their National Health Insurance while others do so with private health insurance, or pay cash to receive care. There are also patients from neighbouring Cote d’Ivoire who attend clinic at BAC regularly. The Centre has tertiary level eye care diagnostic equipment and a fully functional operating theatre.

The Centre has a staff strength of 54, consisting of one part-time ophthalmologist, four full time optometrists, five full time ophthalmic nurses, seven opticians, one pharmacist and other general nurses, health assistants, orderlies and general administrative staff. Three eye care cadres consisting of ophthalmologists, optometrists and ophthalmic nurses make up the team of prescribers.

2.3. Operational Definitions

Acute Conjunctivitis: All cases diagnosed as acute conjunctivitis as recorded in the EMR (Medlink software) used at the facility

Appropriate use of antibiotic medication: Antibiotics used only where there is an indication or suspicion of bacterial infection.

The diagnostic aid provided in Supplementary Material served as reference for the classification of the various types of conjunctivitis as agreed upon by the research team at the study centre. For this study, we will use the following criteria for ascertaining appropriateness.

Appropriateness: a) antibiotics prescribed for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. b) not prescribing antibiotics in the absence of acute bacterial conjunctivitis

Inappropriateness: a) not prescribing antibiotics when there is acute bacterial conjunctivitis. b) prescribing antibiotics when there is no indication of bacterial conjunctivitis except where there are extenuating circumstances.

2.4. Study Population

The study population consisted of:

All cases of acute conjunctivitis from 1st January to 31st December 2021 at BAMCEC who were not prescribed antibiotics, and

All cases of acute conjunctivitis which were reported at BAMCEC from January 01 to December 31, 2024.

In order to assess the impact of the operational research, knowledge dissemination and training on prescribing practices between the two time-periods, we calculated a sample size using OpenEpi Version 3.01 (Open-Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health) Software package. We hypothesised that the percentage of prescribing being deemed appropriate would rise from 71% to 85% (14% increase) as a result of the intervention. With 95% confidence and 80% power, a total sample size of 292 would be required (146 in each time-period). The previous study described 201 patients with acute conjunctivitis in the one-year period (2021). Since the current study also described patients in an entire year (2024), we expected a similar number of acute conjunctivitis cases. We anticipated 402 cases (201 in each time - period) which allowed us to make the comparison.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

All cases diagnosed as acute conjunctivitis as recorded in the Electronic Medical Record System (EMR) system (Medlink software) used at the facility and whose treatment cards are available.

2.6. Data Variables and Sources of Data

Variables included demographic data, details of diagnosis and treatment, antibiotics prescribed, cadre of prescriber. These were obtained from the EMR system complemented by information from patient treatment cards.

2.7. Data Collection and Entry

For the two time-periods, a list of patients in whom the diagnosis was recorded as “Acute Conjunctivitis” was extracted from the electronic medical records (Medlink software) as an MS Excel spreadsheet. This spreadsheet included the patient’s folder number (which is a unique identifier for a patient), their age, sex and place of residence.

The patient’s folder number from the list was used to retrieve the patients’ treatment cards. By reviewing the treatment cards, a team of three (two optometrist and one ophthalmic nurse) cross checked the presenting complaints and symptoms in each folder to ascertain the type of conjunctivitis. The team also extracted other relevant information (whether antibiotics were prescribed, names of antibiotics prescribed, appropriateness of antibiotic prescription or non-prescription) from the patient treatment cards and entered this onto a data collection form created on the Epicollect5 mobile application. In a situation where further information was missing from the patient treatment card, the case was excluded.

2.8. Data Analysis

The data entered into the Epicollect5 application was downloaded as an MS Excel spreadsheet. This spreadsheet was merged with the MS Excel spreadsheet containing the list of patients from the Medlink software using the VLOOKUP function of MS Excel (Microsoft Corporation) with the Patient’s folder number as a unique identifier to link the two sheets. This final dataset was imported into STATA version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

Sociodemographic characteristics (age categories, sex, region of residence), types of diagnosis, patterns of antibiotic prescriptions, and the appropriateness of use or non-use of antibiotics were summarised as numbers and proportions.

Chi-square test and the z-test were used to evaluate differences in proportions. The level of significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

There was a total of 3968 conjunctivitis cases recorded from 1

st January to 31

st December 2024. Of these, 220 (5.5%) had Acute Conjunctivitis as recorded in the EMR of BAMCEC. There were 119 (54.1%) females and males were 101(45.9%). A majority of the patients were adults aged eighteen years or more followed by children under five. Also, almost all of the patients were from the Central region. Of those diagnosed with AC, 67.3% were prescribed antibiotics; a significantly higher proportion, compared with that of 2021’s 55.2% (p=0.011). Details of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who visited BAMCEC with acute conjunctivitis in 2024 are provided in

Table 1.

3.2. Proportions of Patients Prescribed Antibiotics

There was a significant difference in antibiotic prescription based on age groups between 2021 and 2024 (p<0.001). Among those prescribed antibiotics in 2021, majority (65%) were children under 5 years of age, whereas majority (56%) of patients prescribed antibiotics in 2024, were aged 18 years or above. There was slight decrease in the proportion of males among patients who received antibiotics in 2024 (43%) compared to 2021 (49%), but this was not statistically significant. The proportion of patients who were prescribed antibiotics by optometrists/ophthalmologists was significantly higher in 2024 (71%) compared to 2021 (53%) (p=0.002) as shown in

Table 2.

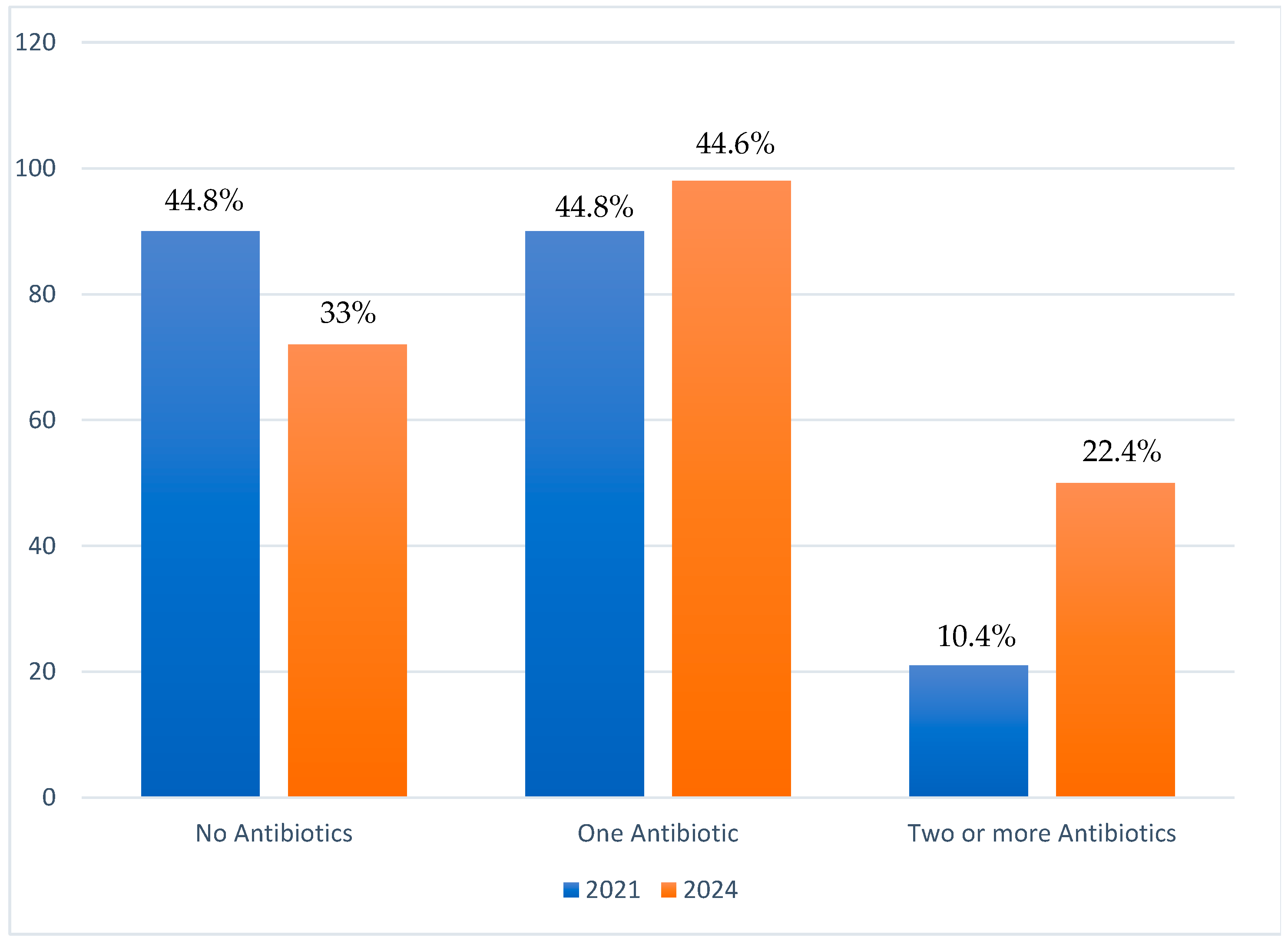

Of all 220 AC cases, 33% had no antibiotics prescribed, 44.6% had one antibiotic prescribed, and 22.4% had two or more antibiotics prescribed. This contrasts with findings in 2021 where 44.8% of the 201 cases received no antibiotics whiles 44.8% received one antibiotic with a further 10.4% receiving more than one antibiotics as shown in

Figure 1.

3.3. Appropriateness of Prescribing or not Prescribing Antibiotics for Treatment of AC in a Ghanaian Eye Hospital

Of all AC cases prescribed antibiotics the prescription was assessed as ‘appropriate’ in 87.1% in 2024, which is a 16% increase compared to the 71% reported in 2021 (p=0.001). In cases where antibiotics were NOT prescribed, the non-prescription was assessed as ‘appropriate’ in 98.6% of cases in 2024. Overall, the composite proportion of appropriateness for antibiotic treatment was 90.9% as shown in

Table 3. Data for 2021 was incomplete for cases where antibiotics were not prescribed. However, of the 28 that could be obtained out of the 90, all were assessed to be appropriate.

The appropriateness of antibiotic prescription was further investigated by sex, age-group and prescribing cadres (ophthalmic nurses or optometrist) for any associations. There was statistically significant differences in appropriateness as it relates to age-categories in 2024 (p=0.008), but in 2021, no such significant differences were observed. In children under five years, 97.6% received appropriate antibiotic prescriptions, while proportions of older children (5-17 years) and adults with appropriate antibiotic prescriptions were 70.8% and 86.8% respectively. No statistically significant differences were found related to sex or prescribing cadre. Of optometrists prescriptions 88.6% were appropriate compared to 83.7% of those of ophthalmic nurses as seen in

Table 4.

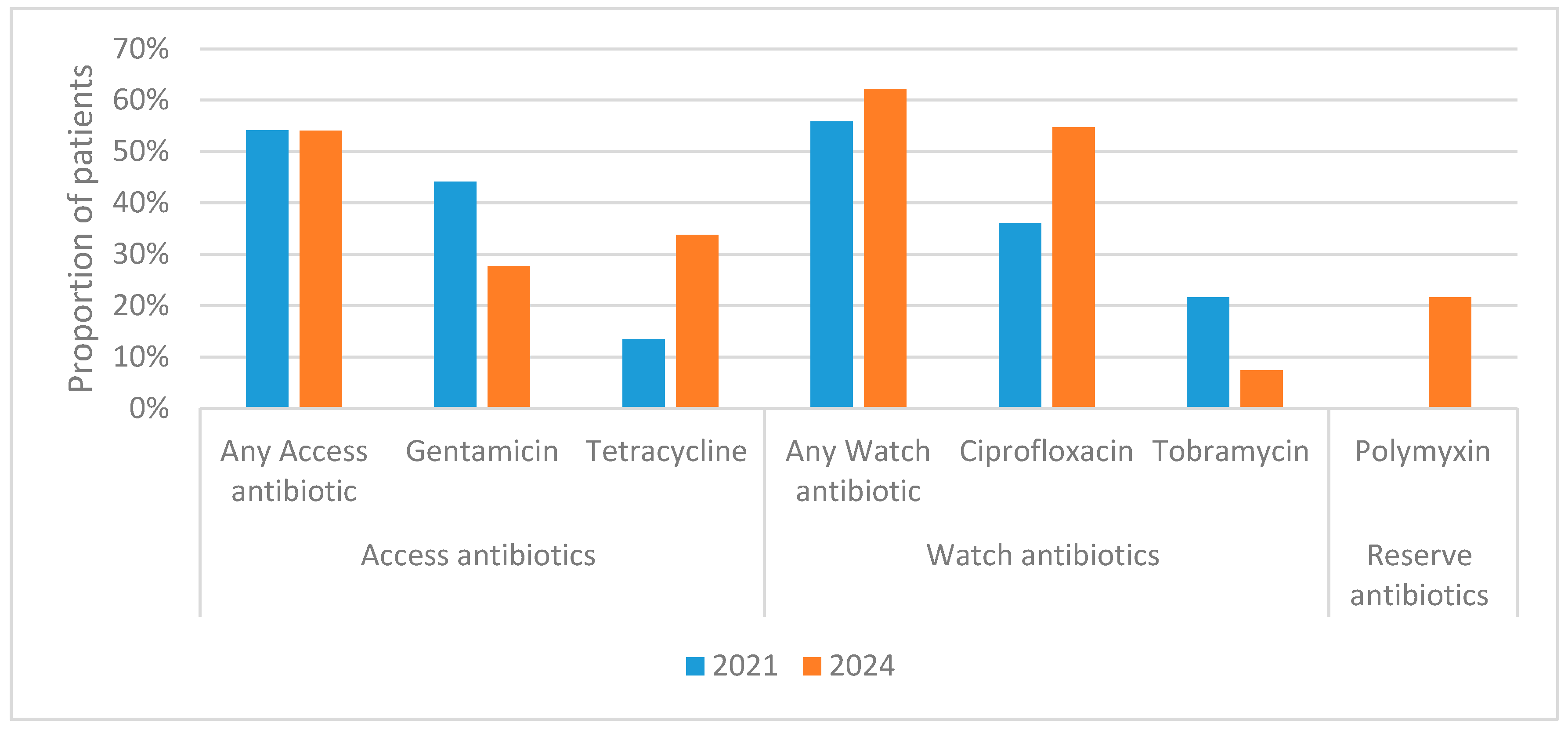

3.4. Types and Proportions of Antibiotics Prescribed Per the WHO AWaRe Classification

The WHO AWaRe Scheme was used to identify the proportions of prescribed antibiotics in the three categories (ACCESS, WATCH and RESERVE). Of the total 215 antibiotics prescribed in 2024, 42.3% were in the ACCESS category, 42.8% were in the WATCH category, whiles, 14.9% belonged to the RESERVE category, as represented in

Table 5. There was statistically significant difference between 2021 and 2024 with respect to the RESERVE category (p<0.001) but not in ACCESS and WATCH categories.

Distribution and proportions of 2Peason’s Chi-square test

ACCESS, WATCH and RESERVE antibiotics prescribed for AC in 2021 and 2024 is represented in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

This research study has demonstrated that operational research combined with effective communication of the findings and their implications can bring about improvements in antibiotic prescribing in eye-care.

There were very similar numbers of acute conjunctivitis cases in 2021 and 2024 (201 and 220 respectively). These met the projection used in calculating a sample size that would allow comparison of data from 2021 and 2024.

In the 2024 study, 50% of acute conjunctivitis was assessed as infectious and 50% non-infectious. Of the acute infectious conjunctivitis cases, 80% were assessed as bacterial AIC and 20% as viral AIC. This distinction was not made explicit in the 2021 study by Hope et al. [

24] but the proportion of AC cases being prescribed antibiotics significantly increased from 55.2% in 2021 to 67.3% in 2024 (p = 0.011). The higher proportion of antibiotic prescriptions recorded compared with percentage of AIC is attributable to treatment of suspected secondary infection and prophylactic treatment in non-infectious acute conjunctivitis. There was also a statistically significant increase in the appropriateness of antibiotic prescription (p=0.001) (87.1% in 2024 compared to 71.2% in 2021). Moreover, the appropriateness of withholding antibiotics (i.e. non-prescription of antibiotics) was assessed as appropriate in 98.6% of AC cases. Analysis of the 2021 data on appropriateness of non-prescription while limited in terms of the data available nevertheless indicated that non-prescription of antibiotics was also highly appropriate and that this had been maintained alongside the improvements in prescribing appropriateness.

Recent findings reveal a shift in the distribution of antibiotic prescribing patterns among healthcare cadres. In 2024, optometrists accounted for 71% of prescriptions for acute conjunctivitis, while ophthalmic nurses were responsible for the remaining 29% (p = 0.024). This marks a notable change from 2021, when ophthalmic nurses prescribed 46.8% of antibiotics and optometrists or ophthalmologists (predominantly optometrists) accounted for 53.2% [

24]

Despite the shift in roles, no significant differences were observed in 2024 between the two cadres in terms of the appropriateness of prescriptions: 88.6% for optometrists and 83.7% for ophthalmic nurses. In comparison, the 2021 proportions were lower (74.6% for optometrists and 67.3% for ophthalmic nurses); indicating improvement in both groups, with ophthalmic nurses showing the most notable progress.

These trends suggest encouraging improvements in prescribing practices across both cadres. However, the observed shift in prescribing roles warrants further investigation to better understand the factors driving this change.

In 2021, there were no statistically significant differences in the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing across age groups for acute conjunctivitis (AC) cases. However, by 2024, a significant difference was observed. Specifically, 97.6% of children under five years received appropriate antibiotic prescriptions, compared to 70.8% of children aged 5–17 years and 86.8% of adults. This finding highlights the need for future training of prescribers to focus on improving antibiotic prescribing practices in specific age groups. Enhancing appropriateness in older children and adults is expected to contribute to improved overall antibiotic stewardship.

The research findings also give some cause for concern and indications for remedial action. While the proportion of AC cases receiving one antibiotic remained comparable (44.8% in 2021 and 44.6% in 2024), the proportion of AC cases prescribed two or more antibiotics has increased from 10.4% in 2021 to 22.7% in 2024. More concerning was the emergence of Polymyxin B, a RESERVE category antibiotic, in 14.9% of prescriptions for acute conjunctivitis (AC) in 2024. This marks a significant change, as no RESERVE antibiotics were prescribed for AC during the 2021 study period (p<0.001). The use of Polymyxin B is particularly alarming given that RESERVE antibiotics are intended for use only as a last resort in specific, hard-to-treat infections. It is speculated that, this inappropriate use may have been driven by stock-outs of ACCESS and WATCH category alternatives, underscoring the need for robust supply chain management and stricter antibiotic stewardship protocols. The proportions of ACCESS antibiotics (gentamycin and tetracycline) being prescribed remained similar across the two study periods (46% in 2021, 42.3% in 2024). The proportions of WATCH category antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and tobramycin) decreased from 54% in 2021 to 42.8% in 2024. In 2024, the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for AC was ciprofloxacin (36.7% of antibiotic prescriptions), followed by tetracycline (23.3%), gentamycin (19.1%), tobramycin (5.1%) and Polymyxin B (14.9%).

The research and dissemination activities may likely be responsible for the improvements in antibiotic prescribing described above. However, incomplete implementation of all the recommendations of the initial investigators may be partly responsible for some of worrying trends observed. Two of the recommendations not implemented as of yet were:

To monitor the use of antibiotics in the Eye Clinic by Local Antibiotic Stewardship Team (LAST); and

To conduct Continuing Professional Development (CPD) training related to antibiotic prescribing through the Drugs and Therapeutic Committee (DTC) at BAMCEC.

Two major concerns identified by the research are the rising number of AC cases being prescribed two or more antibiotics, and the inappropriate use of RESERVE category antibiotics. These issues might have been mitigated if staff had received training through the DTC. Furthermore, even if such prescribing had occurred, it could have been detected earlier if LAST had been empowered to monitor antibiotic use in the Eye Clinic.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study is that all acute conjunctivitis cases attending BAMCEC in the two year-long study periods were included. There was therefore no selection bias at the health facility level. Reporting adhered to the Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

27]. This research will contribute to the One health approach in policy making efforts focused on optimizing the use of antimicrobials as provided in objective 4 of the Global and National Action Plan from the perspective of eye care [

22,

23].

A limitation was that changes in medical record systems and practice prevented all patient records being retrieved from 2021 AC cases who had not been prescribed antibiotics. This was discussed further in the results section. A further limitation may be changes in the population attending services at BAMCEC.

Table 1 describes the demographics of the 2021 and 2024 populations. In the 2021 study 38.3% of acute conjunctivitis cases were aged under-five, 21.4% aged 5 – 17 years, and 39.8% aged 18 and above. In 2024, it can be seen that 20.9% of acute conjunctivitis cases were aged under-five, 20% aged 5 – 17 years, and 59.1% aged 18 and over. It can also be seen that in the 2021 study 81.1% of the AC cases were from Central, 15.9% from Western, 2.5% from Western North and 0.5% from Greater Accra. This compares with 96.4% of AC cases being from the Central Region, 2.7% from Western region and 0.9% from Ashanti region in the 2024 study.

5. Conclusions

This research has demonstrated the power of regular operational research to improve antibiotic prescribing in eye health in Ghana. It allows progress to be monitored and the early detection of worrying practices. It is imperative that the recommendations of the initial researchers are fully implemented, and the study replicated in other facilities to protect the future efficacy of available antibiotics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Henry Kissinger Ansong, Divya Nair, Andrew Ramsay and Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope; Data curation, Henry Kissinger Ansong, Joana Abokoma Koomson and Jane Frances Acquah; Formal analysis, Divya Nair; Investigation, Henry Kissinger Ansong; Methodology, Henry Kissinger Ansong, Divya Nair, Andrew Ramsay and Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope; Project administration, James Buckman; Resources, Henry Kissinger Ansong, Divya Nair and Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope; Software, Divya Nair; Supervision, Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope; Validation, Henry Kissinger Ansong, Divya Nair and Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope; Visualization, Henry Kissinger Ansong; Writing – original draft, Henry Kissinger Ansong and Andrew Ramsay; Writing – review & editing, Obed Kwabena Offe Amponsah, Andrew Ramsay and Paa Kwesi Fynn Hope. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This SORT IT program was funded by TDR (Grant Number TDR.HQTDR 2422924-4.1-72863). The APC was also funded by TDR. TDR is able to conduct its work thanks to the commitment and support from a variety of funders. A full list of TDR donors is available at:

https://tdr.who.int/about-us/our-donors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital Ethical Review Committee (CCTHERC/EC/2025/126, July 2025) and the Ethics advisory group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France (EAG 23/24, August 2024). Permission to use the data was obtained from BAMCEC, Cape Coast, Ghana.

Informed Consent Statement

As we used secondary anonymized data, the issue of informed consent did not apply.

Data availability statement

Requests to access these data should be sent to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

This publication was developed through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by TDR, the UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank and WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, hosted at the World Health Organization (WHO).This specific SORT IT programme that led to this publication included a collaboration between TDR, The World Health Organization Ghana Country Office, and following Ghanian and International Institutions (listed in alphabetic order). International Institutions: The Centre for Operational Research of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris and India offices; The Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Pondicherry; The National TB Control Programme of Kyrgyzstan; The Tuberculosis Research and Prevention Center NGO, Armenia. University of St Andrews Medical School, Scotland, UK. Ghana institutions; 37 Military Hospital, Ghana; Bishop Ackon Memorial Christian Eye Centre, Ghana; Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Animal and Water Research Institutes, Ghana; Environmental Protection Authority, Ghana; Ho Teaching Hospital, Ghana; Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana University Hospital;, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana; Department of Pharmacy Practice, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ghana We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all participating institutions and partners.

Declaration on use of artificial intelligence

We have used Chat GPT for text revisions and grammatical corrections in the drafting of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Disclaimer

There should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their affiliated institutions. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted.

Appendix 1. Classification of conjunctivitis. Adapted from Standard Treatment Guidelines 7th edition [11]

Appendix 2

Symptom Criteria for acute conjunctivitis. Adapted from 7

th Edition of the Ghana Standard Treatment Guidelines 2017 (STG) [

11]

| Symptoms |

Allergic conjunctivitis |

Bacterial conjunctivitis |

Viral conjunctivitis |

| Appearance of discharge |

White stringy mucoid |

Mucopurulent |

Watery |

| Presence of erythema |

Mild to moderate |

Moderate to severe |

Mild to moderate |

| Pruritus |

Moderate to severe |

None to mild |

Mild to moderate |

| Bilateral eye involvement |

Common |

Unilateral initially |

Rare |

| Presence of lymphadenopathy |

None |

Rare |

Common |

| Upper respiratory coinfection |

None |

Rare |

Common |

References

- Shekhawat, N.S.; Shtein, R.M.; Blachley, T.S.; Stein, J.D. Antibiotic Prescription Fills for Acute Conjunctivitis among Enrollees in a Large United States Managed Care Network. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 1099–1107.

- Leibowitz, H.M.; Pratt, M. V; Flagstad, I.J.; Berrospi, A.R.; Kundsin, R. Human Conjunctivitis: II. Treatment. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1976, 94, 1752–1756. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M. B., & Croasdale, C. R. (1997). The Red Eye: A Clinical Guide to a Rapid and Accurate Diagnosis. 1997, 1997.

- Varu, D.M.; Rhee, M.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Amescua, G.; Farid, M.; Garcia-Ferrer, F.J.; Lin, A.; Musch, D.C.; Mah, F.S.; Dunn, S.P. Conjunctivitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, P94--P169.

- Azari, A.A.; Arabi, A. Conjunctivitis: A Systematic Review. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2020, 15, 372–395. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.P.; Jeng, B.H.; McDonald, M.; Raizman, M.B. Acute Conjunctivitis: Truth and Misconceptions. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 1953–1961.

- Cronau, H.; Kankanala, R.R.; Mauger, T. Diagnosis and Management of Red Eye in Primary Care. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 81, 137–144.

- Ryder EC, Benson S. Conjunctivitis. In: StatPearls . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2020. 2020, 7431717.

- Azari, A.A.; Barney, N.P. Conjunctivitis: A Systematic Review of Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 2013, 310, 1721–1730. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Differential Diagnosis of Red Eye. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010, 36, 213–215.

- Ministry of Health Ghana National Drugs Programme: Standard Treatment Guidelines, Seventh Edition; 2017; ISBN 9789988257873.

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial Resistance : A Global Multifaceted Phenomenon. 2015, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Organization World Health Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS). Antibiotic Use Data for 2022; 2025;

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Atlanta: CDC; 2013. Available from: Http://Www.Cdc.Gov/Drugresistance/Pdf/Ar-Threats-2013-508.Pdf [ Google Scholar ]. 2013, 4768623.

- Kapi , A . ( 2014 ). The Evolving Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance : Options for Action . Indian Journal of Medical. 2014, 139, 2014.

- Asamoah, B.; Labi, A.-K.; Gupte, H.A.; Davtyan, H.; Peprah, G.M.; Adu-Gyan, F.; Nair, D.; Muradyan, K.; Jessani, N.S.; Sekyere-Nyantakyi, P. High Resistance to Antibiotics Recommended in Standard Treatment Guidelines in Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Study of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns in Patients with Urinary Tract Infections between 2017--2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16556.

- Donkor, E.S.; Odoom, A.; Osman, A.; Darkwah, S.; Kotey, F.C.N. A Systematic Review on Antimicrobial Resistance in Ghana from a One Health Perspective. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Walana, W.; Vicar, E.K.; Kuugbee, E.D.; Sakida, F.; Baba, I. Antimicrobial Resistance of Clinical Bacterial Isolates According to the WHO ’ s AWaRe and the ECDC-MDR Classifications : The Pattern in Ghana ’ s Bono East Region Introduction. 2023, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Zolfo, M.; Williams, A.; Ashubwe-jalemba, J.; Tweya, H.; Adeapena, W.; Labi, A.; Adomako, L.A.B.; Addico, G.N.D.; Banu, R.A.; et al. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Drinking Water from the Greater Accra Region , Ghana : A Cross-Sectional Study , December 2021 – March 2022. 2022.

- Spellberg, B.; Hansen, G.R.; Kar, A.; Cordova, C.D.; Price, L.B.; Johnson, J.R. Antibiotic Resistance in Humans and Animals. NAM Perspect. 2016.

- Frieri, M.; Kumar, K.; Boutin, A. Antibiotic Resistance. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 369–378.

- World Health Organization. Report of the 6 Meeting: WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Survaillance of Antimicrobial Resistance with AGISAR 5-Year Strategic Framework of the Global Action Plan on Antimicribial Resistance; 2021;

- Ministry of Health Ghana National Action Plan for Antimicrobial Use and Resistance Republic of Ghana; 2017; ISBN 9789988266554.

- Hope, P.K.F.; Lynen, L.; Mensah, B.; Appiah, F.; Kamau, E.M.; Ashubwe-Jalemba, J.; Peprah Boaitey, K.; Adomako, L.A.B.; Alaverdyan, S.; Appiah-Thompson, B.L.; et al. Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Conjunctivitis: A Cross-Sectional Study at a Specialist Eye Hospital in Ghana, 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Zanichelli, V.; Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Moja, L.; Getahun, H.; Pessoa-Silva, C.; Sati, H.; van Weezenbeek, C.; Balkhy, H.; Simão, M.; et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Antibiotic Book and Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 290–296.

- Ghana Statistical Service Press Release.

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE Guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).