1. Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is major complication of diabetes mellitus (DM). Patients with DFU are at risk of foot infection (DFI), which if not timeously and effectively treated may lead to major amputation and/or death [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that the number of individuals living with diabetes will reach 853 million by 2050, with the number in South Africa reaching 3.9 million [

7,

8,

9]. Diabetic foot disease remains is the leading cause of non-traumatic amputations and associated mortality in various countries, including South Africa [

4,

5,

6,

9,

10]. The likelihood of developing DFU is higher in patients with longstanding or poorly controlled DM, older age, low socio-economic status, lack of family support, occupations predisposing to foot in trauma, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, high body mass index (BMI), peripheral neuropathy and peripheral artery disease [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Diabetic foot ulcer is preventable but barriers that remain include limited knowledge of appropriate foot care among healthcare practitioners and patients [

16,

17]. Effective prevention and treatment of DFU require a multidisciplinary approach, which must include active participation of patients and their families [

3,

18]. Often, individuals with DM do not perceive the urgency of foot-related symptoms due to neuropathy or a lack of awareness about the risks, leading to a delay in presentation to healthcare facilities for treatment. Delayed presentation of DFU with or without DFI increases the likelihood of amputation and mortality [

1,

3,

19].

Although the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF, 2023) advocates for a structured patient education and early detection strategies to reduce the burden of diabetic foot disease, gaps in the knowledge and foot care practices among patients with DM persist, especially in low- and middle-income countries [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, despite knowing the importance of foot care some of the patients do not apply it, emphasizing the need for ongoing education and integration of foot care into routine management [

29,

30,

31]. Aljaouni et al. (2024) found that only 35% of patients in Saudi Arabia had good knowledge of foot care, and only 27% practiced it adequately [

32]. Similarly, Pourkazemi et al. (2020) reported that 84.8% of patients with DM had poor knowledge on appropriate foot care and only 8.8% demonstrated good practice [

21].

Improving access to healthcare services and embedding foot care practices and education into routine management of DM are critical strategies for reducing the incidence of DFU [

33,

34]. Essential practices include regular foot inspection, proper foot hygiene, appropriate footwear, maintaining good glycemic control, and continuous support by families and healthcare providers [

34,

35,

36]. This study evaluated levels of knowledge of foot care and prevention of DFU in patients with DM.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at 14 hospitals and health district services. The study took place from September 2023 to July 2024. Participants were patients with DM aged 18 years or older presenting to outpatients’ clinic at public healthcare facilities. Patients with cognitive impairments were excluded. The calculated sample size was 196 participants.

The study used a questionnaire adapted from previously validated tools to assess diabetic foot care knowledge and practices [

21,

22,

23,

30,

31]. The questionnaire included three sections. The first section had six questions addressing socio-demographic information (6 questions). Clinical characteristics were covered by 10 questions in the second section. The last section of the questionnaires had 19 questions assessing levels of knowledge of foot care and prevention of DFU.

The questionnaire was administered to 15 nurses before the study to assess the clarity of the questions. Based on their feedback, minor corrections were made, and the final version of the questionnaire was developed. This pretesting step helped ensure the questionnaire’s validity and reliability. The questionnaire was administered to participants through face-to-face interviews conducted by healthcare professionals during routine follow-up visits. The interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred language. Participants either had to agree or disagree with the statement posed. Appropriate responses of either agree or disagree were labelled Yes for an appropriate response and No for an inappropriate answer.

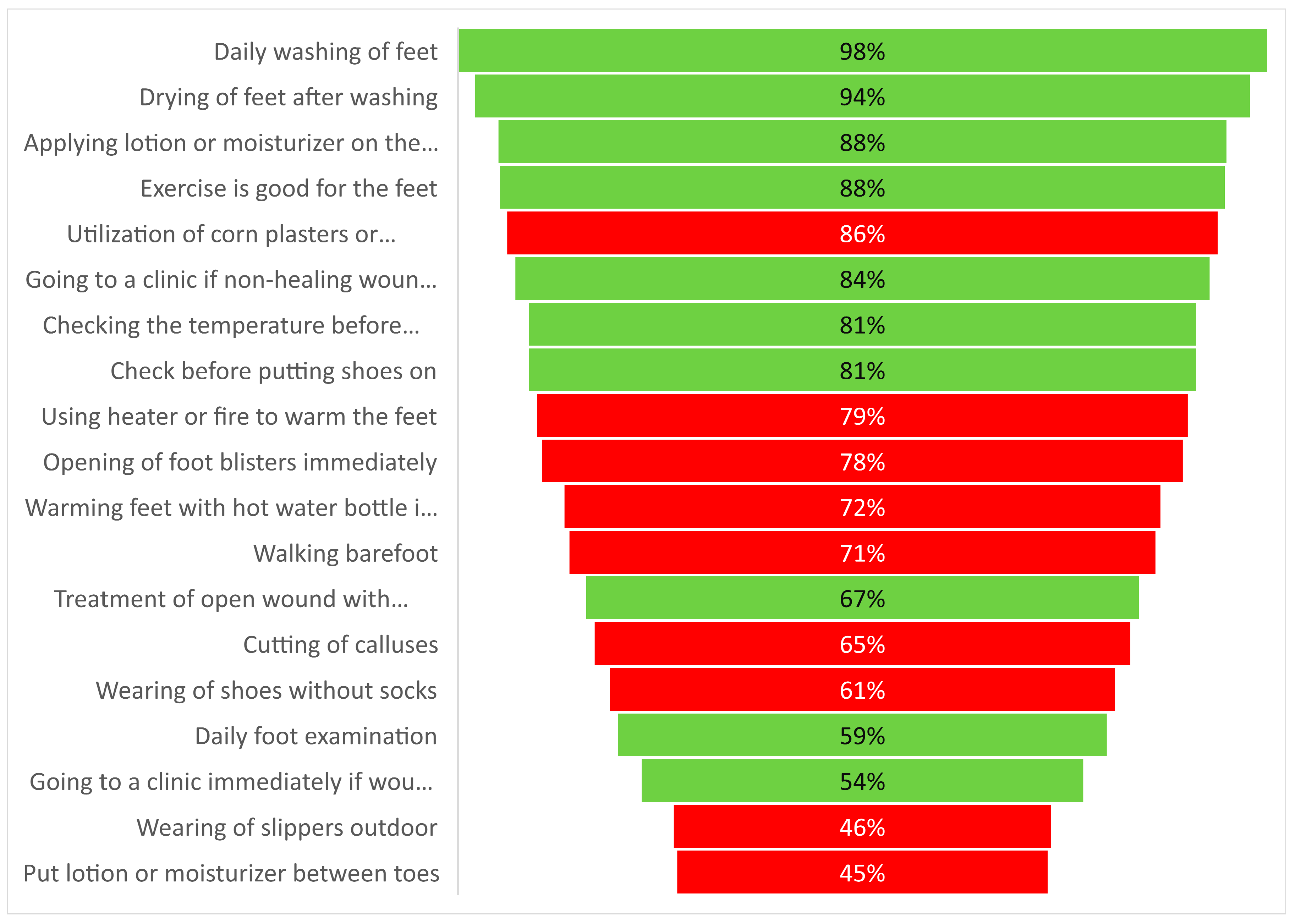

A response was deemed evidence of appropriate knowledge if a participant agreed i.e. marked Yes to daily examination of feet, daily washing of feet, checking of temperature of the water before washing the feet, drying of feet after washing, application of moisturizer or lotion to feet, checking shoes before wearing them, immediate visit to a clinic upon noticing a wound on the foot, cleaning a wound with an antiseptic solution or salt water and presenting to a clinic if there is non-healing wound. Participants with good knowledge of foot care were expected to disagree i.e. marked no to application of moisturizer or lotion in-between toes, using hot water bottle to warm feet, using heater or fire to warm the feet, wearing of shoes without socks, walking barefoot, wearing slippers outdoor, opening foot blisters, cutting calluses self and using corn plasters or removers. The level of knowledge for each question was derived from the percentage of participants who provided appropriate response for each of the 19 questions. Finally, a composite score was calculated.

Data were entered on MS Excel and analysed using STATA version 15. The chi-square test was used to determine if the sex, age, marital status and level of formal education of participants influenced their knowledge of foot care. We also analysed relationships between the type of DM, duration, current pharmacological treatment, prior education on foot care and presenting foot problem, and appropriate knowledge of foot care. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval to conduct the study was received from the local ethics committee (M19/05/62 -19/09/2019) and the study followed the guidelines contained in the 2024 revised Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. All participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the research and signed informed consent before completing the questionnaires (See Appendix A).

3. Results

Two hundred and forty-five (245) patients with DM participated in the study. The majority, (69%: 168/245) were female, and two participants did not declare their sex. The mean age of the participants was 53.7 years (SD 17.7). 41.2% (101/245) were married and 45.3% (111/245) were single. Overall, 61% (149/245) had primary education. Hundred and thirteen (46%:113/245) of the participants were at tertiary level healthcare facilities. Most, 77.6% (190/245) participants had Type 2 DM, and 52.7% (129/245) were diagnosed within the last 10 years. Ninety-two (37.6%:92/245) participants were on combination treatment of oral medications and insulin. Majority of participants, 87.3% (214/245) were non-smokers. The foot problems participants had included paresthesia in 38.8% (95/245), nail pathologies in 14.7% (37/245), callosities in 14.7% (36/245) and prior amputation in 3.3% (8/245). (

Table 1).

The mean score (SD) of good knowledge of foot care among all participants was 73.5% (±9.21). The most commonly agreed-upon practices included drying feet after washing (93.9%:230/245), using lotion or moisturizer on feet (88.2%:216/245), washing feet daily (98%:240/245), checking temperature of water before washing the feet (81%: 198/245) and routinely checking shoes before wearing them (80.8%:198/245) but only 59.2% (145/245) agreed to daily foot examination. For the care of cuts or open wounds, (34%:84/245) agreed to using salt water, and (32.7%: 80/245) an antiseptic. When a wound is not healing did not heal, (84.1%:206/245) of participants agreed to seeking professional care at clinics. Worrying, only 45.7%, 53.5% and 71% will avoid wearing slippers outdoor, would go to clinic immediately on noticing a wound and avoid walking barefoot, respectively (

Figure 1).

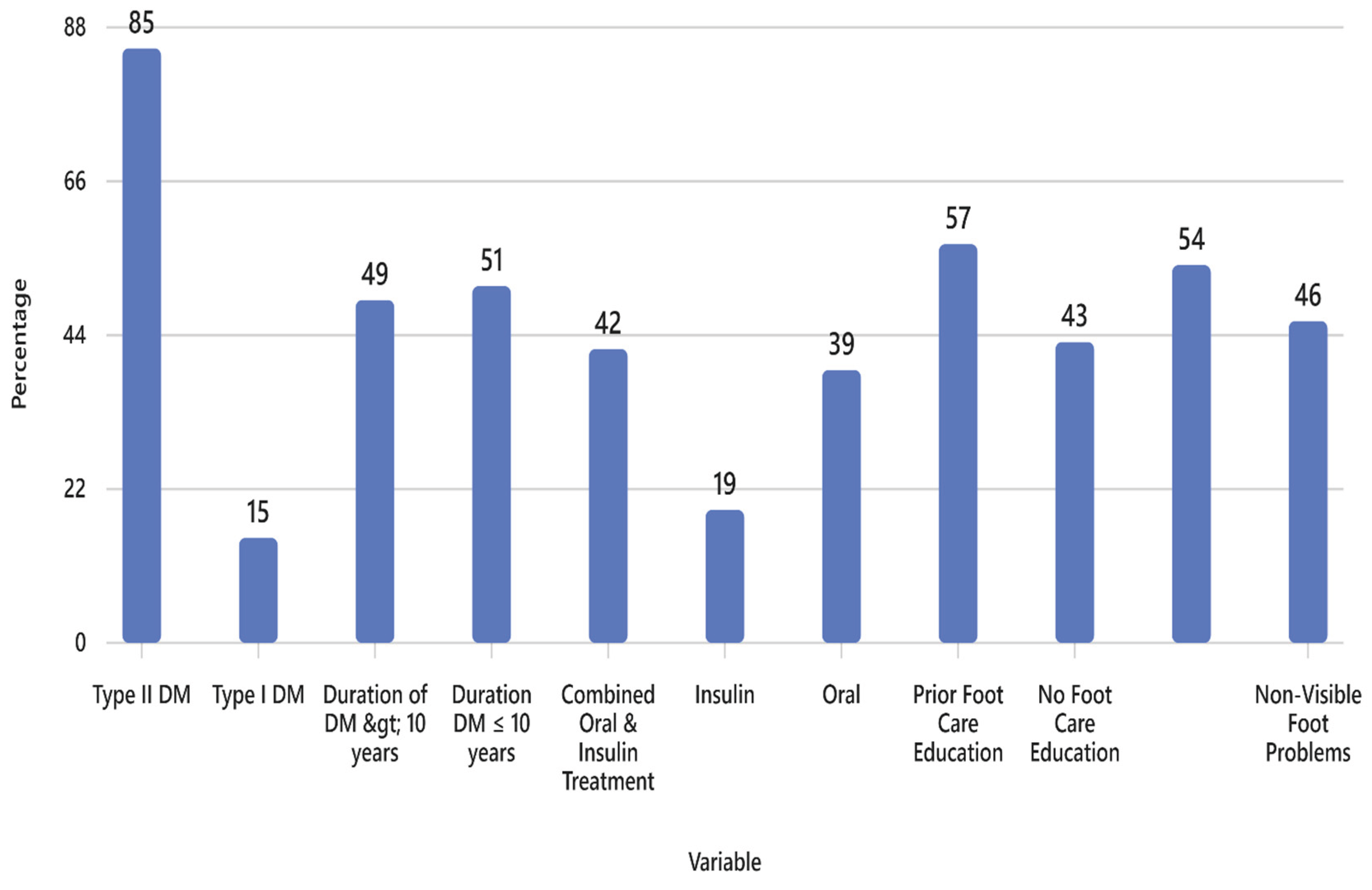

Table 2 showed the statistical associations between various factors and participants’ knowledge of diabetic foot care.

Figure 2 illustrates the proportional distribution of knowledge across these factors. No statistically significant association was found between sex, marital status, education level, or healthcare facility type and knowledge of diabetic foot care (p > 0.05). However, several variables demonstrated significant associations. Age was significantly associated with knowledge (p = 0.0033), with older participants (mean age 57 years) showing good knowledge compared to younger participants (mean age 50.4 years). Type of diabetes was also significant (p = 0.007), with 85% of participants with Type 2 diabetes demonstrating good knowledge, compared to 15% of those with Type 1. Prior foot care education was strongly associated with good knowledge (p < 0.0001), with 57% of educated participants showing good knowledge versus 43% of those without prior education.

Participants on combination oral therapy and insulin reported the highest levels of good knowledge (42%), followed by those on oral therapy alone (39%) and insulin alone (19%), and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.002). Duration of diabetes was significantly associated with foot care knowledge (p = 0.047). Participants with a diabetes duration of 10 years or more, including (32% with 10–20 years, 19% with 21–30 years, and 5% with over 30 year), demonstrated higher knowledge levels (56%) compared to those with less than 10 years of disease duration (44%). Lastly, the presence of visible foot problems was significantly associated with good knowledge (p = 0.030). Participants with visible conditions, such as callosities (15%), nail pathologies (20%), and multiple visible issues (16%), demonstrated higher knowledge levels (54%) compared to those with non-visible problems like paraesthesia (36%) and circulation issues (10%) (

Table 2).

Toenail Cutting Practices: Participant Preferences

The most preferred method for cutting nails was “Straight Across and Not Too Short,” preferred by 33.1% (81/245) of participants. Additionally, 29% (71/245) of participants rely on family members for assistance in cutting their toenails. About 18.4% (45/245) cut their toenails very short and at the corners. Approximately 11.8% (29/245) preferred their toenails to be cut by healthcare professionals and 7.8% (19/245) did not specify the methods they used to cut their toenails.

4. Discussion

Our study assessed the knowledge and practices related to DFU prevention among patients with DM attending public healthcare facilities. Our findings revealed that while participants demonstrated moderate adherence to recommended foot care practices, such as daily foot washing, moisturizing, and checking water temperature, only 59% reported performing daily foot inspections, a critical component of DFU prevention. Although a majority (84.1%) would seek professional care for non-healing wound on a foot, 67% agreed to trying home remedies such as salt water or antiseptics for initial wound care. Importantly, several factors were significantly associated with higher levels of knowledge of foot care, among them older age, longer duration of DM, use of combined oral and insulin therapy, prior education on foot care, and the presence of current foot problems. In contrast, sex, marital status, education level, and level of healthcare facility were not significantly association with knowledge levels. These results underscore the need for targeted educational interventions and routine foot care reinforcement, particularly for younger patients and those newly diagnosed with DM.

The study found that overall 73.5% of the participants demonstrated appropriate knowledge of diabetic foot care, which was higher than in findings from studies conducted in Ethiopia (27%) [

32], Ghana (49%) [

22], Iran (49.6%) [

21], Pakistan (51.9%) [

24] and Saudi Arabia 20.2%-56.9% [

37,

38]. Knowledge of foot care among participants in the current study was however lower and almost similar on the avoidance of wearing slippers outdoor (45.7%) and applying of moisturizer or lotion between toes (44.9%), importance of daily foot examination (59.2%) and not wearing shoes without socks (61.2%). The above variations may be attributed to differences in study populations, healthcare systems, and educational outreach. additionally, our study’s inclusion of participants across all levels of care may have contributed to a more comprehensive representation of the population of patients with DM. Our findings underscore the importance of context-specific, targeted educational interventions involving patients and caregivers in foot care education to improve adherence and clinical outcomes [

39].

Understanding the factors that influence patients’ knowledge of diabetic foot care is essential for designing effective educational strategies. In our study, age emerged as a statistically significant determinant, with older participants exhibiting higher levels of awareness, which may be attributed to longer disease duration and greater engagement with self-care practices overtime. Our findings are support previous findings that that older individuals tend to possess more comprehensive knowledge and demonstrate good foot care behavior due to prolonged exposure to diabetes-related complications [

23,

26,

37]. However, other studies reported lower knowledge scores among older adults compared to younger counterparts, highlighting inconsistencies in the literature [

21,

24,

28,

38]. These discrepancies underscore the need for age-sensitive educational interventions. Based on our findings, we recommend implementing age-specific strategies, providing advanced, complication-focused education for older patients, while equipping younger individuals with foundational knowledge to establish effective self-care routines early in their disease progression.

The type of DM can significantly influence patients’ exposure to education and engagement in self-care practices, particularly foot care. In our study, a statistically significant association was observed between type of DM and knowledge of diabetic foot care. Participants diagnosed with Type II DM demonstrated substantially higher levels of good knowledge (85%) compared to those with Type I (15%). These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [

38] and Ghana [

22], which reported good knowledge levels of 52.5% and 63% among Type II DM patients, respectively. However, in the Ghanaian study, only 49% of participants effectively translated this knowledge into practice, highlighting a gap between awareness and behavioral adherence.

Unlike these studies, which focused exclusively on Type II DM populations, our study included both Type I and Type II patients, with 77% diagnosed with Type II. This broader inclusion may explain the higher overall knowledge levels observed and underscores the need for tailored educational interventions. The comparatively lower knowledge among Type I DM patients, who are often younger and may have had less exposure to chronic disease education, may contribute to disparities in foot care awareness and self-care practices. These findings support the development of diabetes type-specific education strategies, ensuring that patients with Type I DM receive targeted support to build foundational knowledge and preventive behaviors early in their disease course.

The current study found a statistically significant association between the DM duration and patients’ knowledge and practices related to diabetic foot care, with longer DM duration linked to improved outcomes. This improvement appears to be influenced by several key factors such as: patients with long-standing diabetes are more likely to have experienced foot-related complications, which often prompt preventive behaviors; repeated exposure to educational interventions enhancing knowledge retention and application; and sustained engagement with healthcare professionals reinforcing best practices. These cumulative experiences contribute meaningfully to improved awareness and adherence to foot care practices. Our findings are consistent with previous research which reported greater foot care knowledge among patients with longer disease duration [

26,

27,

32,

41]. Notably, Facanha et al. found that 71% of individuals with over 10 years of diabetes demonstrated enhanced foot care knowledge reinforcing the role of disease duration in shaping patient behavior [

41]. However, despite these encouraging trends, overall knowledge levels remain suboptimal in many populations [

24,

37], highlighting the need for targeted, accessible, and culturally sensitive educational strategies, particularly for newly diagnosed individuals. We advocate for early and continuous education as a cornerstone of effective diabetes care.

The complexity of diabetes treatment regimens can influence patients’ understanding and engagement with self-care practices, including foot care

. Our study demonstrated a significant association between treatment type and diabetic foot care knowledge, with patients on combined oral and insulin therapies exhibiting greater understanding. This may be attributed to the complexity of managing dual therapies, which often involves more comprehensive care plans, frequent education, and regular interaction with healthcare providers. Additionally, many participants were older adults with long-standing Type II diabetes and existing foot complications, which likely contributed to their heightened awareness. Despite this encouraging level of knowledge, it does not necessarily translate into improved self-care practices. Previous studies have reported mixed findings [

25,

42]. A study conducted in Kuwait [

42] found that patients on OHAs alone had lower odds of practicing good foot care, while those on diet plus OHAs showed better adherence. Interestingly, the same study reported that patients on combined OHAs and insulin were at greater risk of developing diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), suggesting that treatment complexity may reflect disease severity rather than improved self-care. Similarly, Mekonen and Demssie observed that patients on both injections and pills were more likely to demonstrate poor foot self-care compared to those on injections alone [

25]. Although we sought to identify studies that directly aligned with our findings, no such research was found. This highlights the novelty and relevance of our contribution. By exploring the relationship between treatment complexity and patient knowledge, our findings add to the existing literature and underscore the need for tailored educational interventions and more research in this area. Healthcare providers should consider treatment regimen as a potential indicator of educational needs and priorities, patient-centered education to improve both knowledge and self-care practices.

Prior education on diabetic foot care was strongly and significantly associated with improved knowledge among participants, reinforcing the pivotal role of educational interventions in diabetes management. This association may be partially explained by demographic characteristics in our sample, including older age, longer diabetes duration, and a high prevalence of Type II DM—factors commonly linked to more intensive care, ongoing education, and regular engagement with healthcare providers. Notably, although 55.5% of participants reported not receiving foot care education from healthcare professionals, those who had received such education exhibited significantly higher knowledge levels. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which collectively highlight the positive impact of structured foot care education on patient knowledge and self-care behaviors [

22,

23,

24,

26,

27,

37]. Based on our results, we advocate for the integration of foot care education into routine diabetes care as a strategic approach to reducing foot-related complications and enhancing clinical outcomes. This recommendation is further supported by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF), which emphasizes the importance of educating at-risk individuals to promote effective foot self-care and prevent ulceration [

20].

Diabetic foot complications represent a significant challenge in diabetes management, contributing substantially to patient morbidity and the overall burden on healthcare systems [

6]. These complications, such as ulcers, infections, and amputations, are associated with prolonged hospitalizations, increased medical costs, and a marked decline in patients’ quality of life. A key finding in our study was the significant association between the presence of visible foot problems and higher levels of diabetic foot care knowledge. Participants presenting with conditions such as amputations, callosities, nail pathologies, ulcers, or multiple visible issues demonstrated greater awareness compared to those with non-visible complications, including circulation problems and paraesthesia. This difference may be attributed to more frequent interactions with healthcare providers, longer disease duration, and increased exposure to foot care education as part of complication management. These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran [

21], Ghana [

22], Nigeria [

23], the United Arab Emirates [

27], Pakistan [

24], Saudi Arabia [

32,

37], and Ethiopia [

38], which similarly reported that individuals with diabetic foot complications tend to exhibit improved knowledge and self-care practices. However, this trend also highlights a critical gap in preventive care: individuals without visible foot problems may not receive adequate education or support until complications arise. This reactive approach delays early intervention and increases the risk of severe outcomes. As healthcare professionals, we have a responsibility to ensure that all individuals with diabetes—regardless of symptom presentation—receive comprehensive and proactive foot care education. Emphasizing early education, routine screening, and culturally appropriate interventions is essential to promote effective self-management and prevent the development of diabetic foot complications.

This study has several notable strengths, including its comprehensive scope, with a large and diverse sample drawn from multiple public healthcare facilities, which enhances the generalizability of the findings within the Gauteng region. The use of a structured and previously validated questionnaire ensures methodological rigor and comparability with existing literature. Robust statistical analyses further strengthen the study by identifying significant associations between diabetic foot care knowledge and various demographic and clinical factors. Additionally, the study addresses a critical public health issue in a resource-limited setting and offers actionable recommendations for integrating foot care education into routine diabetes management. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences between knowledge and practices, while the use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias. Relying on self-reported data could lead to recall or social desirability bias, and although the study involves multiple facilities, its findings may not be generalizable to private healthcare settings or other provinces. Furthermore, the lack of longitudinal follow-up restricts the ability to determine whether increased knowledge results in sustained behavioral change or improved clinical outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that while moderate adherence to diabetic foot care practices exists among patients in Gauteng Province, critical gaps remain, particularly in daily foot inspections and early preventive education. Factors such as age, type and duration of diabetes, treatment complexity, prior education, and the presence of foot complications significantly influence knowledge levels. However, demographic variables such as sex, marital status, and education level showed no significant impact. To address these gaps, it is essential to integrate structured foot care education into routine diabetes management, targeting younger and newly diagnosed patients, and tailoring interventions based on diabetes type and treatment regimen. Additionally, community engagement should be promoted by involving caregivers and community health workers in outreach efforts, thereby extending the reach of foot care awareness beyond clinical settings and fostering a more inclusive, preventive approach to diabetic foot care.

Author Contributions

T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, T.EL, Conceptualization; T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, T.EL, Methodology; T.M, T.P.M, T.EL, Validation; S.B.K, Formal Analysis; T.M, T.P.M, SBK; Investigation; T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, T.EL, Resources; T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, Data Curation; T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, Writing—Original Draft Preparation; T.M, T.P.M, S.B.K, T.EL, Writing—Review and Editing; T.M, T.P.M, T.E.L, Supervision; TEL, Project Administration; T.M, T.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee (M19/05/62 -19/09/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request following receipt of authorization from our local ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

Were sincerely appreciate cooperation of participants and staff across all facilities that participated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| DFI |

Diabetic foot infection. |

| DFU |

Diabetic foot ulcer |

| DM |

Diabetes mellitus. |

| IDF |

International Diabetes Federation. |

| IWGDF |

International Working Group on Diabetic Foot. |

References

- Zhang, P.; Lu, J.; Jing, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2016, 49, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, K.; Fang, M.; Boulton, A.J.; Selvin, E.; Hicks, C.W. Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2022, 46, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatem, M.A.; Kamal, D.M.; Yusuf, K.A. Diabetic foot limb threatening infections: Case series and management review. Int. J. Surg. Open 2022, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorlaakso, M.; Kiiski, J.; Salonen, T.; Karppelin, M.; Helminen, M.; Kaartinen, I. Major Amputation Profoundly Increases Mortality in Patients With Diabetic Foot Infection. Front. Surg. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.; Huda, F.; Roshan, R.; Basu, S.; Rajput, D.; Singh, S.K. ; Mbbs; Ms Lower Limb Amputation Rates in Patients With Diabetes and an Infected Foot Ulcer: A Prospective Observational Study. Wound Manag. Prev. 2021, 67, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, A.; Saboo, A.; Malabu, U.H.; Falhammar, H. Lower extremity amputations and long-term outcomes in diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas (11th ed.). 2025. Retrieved from https://diabetesatlas.org.

- Garg, R.K. The alarming rise of lifestyle diseases and their impact on public health: a comprehensive overview and strategies for overcoming the epidemic. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2025, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Ran, X. Global mortality of diabetic foot ulcer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2022, 25, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.Z.; Smith, M.T.; Bruce, J.L.; Kong, V.Y.; Clarke, D.L. Evolving Indications for Lower Limb Amputations in South Africa Offer Opportunities for Health System Improvement. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K.L.; Abusamaan, M.S.; Voss, B.F.; Thurber, E.G.; Al-Hajri, N.; Gopakumar, S.; Le, J.T.; Gill, S.; Blanck, J.; Prichett, L.; et al. Glycemic control and diabetic foot ulcer outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2020, 34, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; Al Derwish, M.; Ouizi, S.; Youssef, A.M.; Subhani, S.N.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Alamri, B.N.; Santanelli, d.P.D.F. Diabetic Foot Complications and Their Risk Factors from a Large Retrospective Cohort Study. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Zhang, W. Risk Factors Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes and Recent Advances in the Treatment and Prevention. Int. J. Med Sci. 2014, 11, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, P.; Ding, H. Analysis of risk factors for foot ulcers in diabetes patients with neurovascular complications. BMC Public Heal. 2025, 25, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachin, I.D.; Manasa, M.R.; Subhashree, P. Study of socio-demographic, behavioural and clinical risk factors of diabetic foot in a tertiary care centre. Int. Surg. J. 2021, 8, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Netten, J.J.; Sacco, I.C.; Lavery, L.A.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Raspovic, A.; Bus, S.A. Treatment of modifiable risk factors for foot ulceration in persons with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, L.; Driscoll, A.; Wynter, K.; Rasmussen, B. Barriers and enablers to delivering preventative and early intervention footcare to people with diabetes: a scoping review of healthcare professionals' perceptions. Aust. J. Prim. Heal. 2019, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somayaji, R.; Elliott, J.A.; Persaud, R.; Lim, M.; Goodman, L.; Sibbald, R.G. The impact of team-based interprofessional comprehensive assessments on the diagnosis and management of diabetic foot ulcers: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.J.; van Vuuren, S.; Rapper, S.L.-D. Analysing patient factors and treatment impact on diabetic foot ulcers in South Africa. South Afr. J. Sci. 2024, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, S.A.; Sacco, I.C.N.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Raspovic, A.; Paton, J.; Rasmussen, A.; Lavery, L.A.; van Netten, J.J. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2023, 40, e3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourkazemi, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Khojamli, M.; Balo, H.; Hemmati, H.; Jafaryparvar, Z.; Motamed, B. Diabetic foot care: knowledge and practice. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuglo, L.S. Knowledge and practice of diabetic foot care among patients in selected hospitals in the Volta Region, Ghana. Int. Wound J. 2021, 19, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotosho, T.O.A.; Sanyang, Y.; Senghore, T. Diabetic foot self-care knowledge and practice among patients with diabetes attending diabetic clinic in the Gambia. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuhro, B.A. Diabetic foot care: knowledge and practices regarding foot care among diabetic patients in tertiary care hospital Nawabshah, Pakistan – a cross-sectional study. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 06, 11857–11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, E.G.; Demssie, T.G. Preventive foot self-care practices among diabetic patients in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwanga, F.S.; Njelekela, M.; Mwakalebela, M.; Mushi, D.; Mlay, G.; Mboya, T. Diabetic foot: prevalence, knowledge, and foot self-care practices among diabetic patients in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – a cross-sectional study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2015, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlOwais, M.M.; Shido, O. Knowledge and practice of foot care in patients with diabetes mellitus attending primary care center at Security Forces Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5954–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, F.; Berhanu, D.; Alemu, G.; Tadesse, H.; Abebe, M.; Tesfaye, S. Knowledge and attitude on diabetic foot ulcer care and associated factors among diabetic mellitus patients on chronic care follow-up of southwestern Ethiopian hospitals: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 72, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirpha, N.; Tatiparthi, R.; Mulugeta, T. Diabetic Foot Self-Care Practices Among Adult Diabetic Patients: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 4779–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikeukwu, R.; Omole, O. Awareness and practices of foot self-care in patients with diabetes at Dr Yusuf Dadoo district hospital, Johannesburg. J. Endocrinol. Metab. Diabetes South Afr. 2013, 18, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goie, T.T.; Naidoo, M. Awareness of diabetic foot disease amongst patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending the chronic outpatients department at a regional hospital in Durban, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Heal. Care Fam. Med. 2016, 8, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaouni, M.E.; Alharbi, A.M.; Al-Nozha, O.M. Knowledge and Practice regarding foot care among patients with type II diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research 2024, 12, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Driscoll, A.; Rasmussen, B. Preventative and early intervention diabetes-related foot care practices in primary care. Aust. J. Prim. Heal. 2020, 26, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Chambers, A.R. Diabetic foot care. In StatPearls [Internet]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553110/; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, G.S.G.; Landeiro, M.J.L.; Maciel, T.; de Sousa, M.R.M.G.C. Clinical practice guidelines of foot care practice for patients with type 2 diabetes: A scoping review using self-care model. Contemp. Nurse 2024, 60, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Driscoll, A.; Rasmussen, B. Prioritisation of diabetes-related footcare amongst primary care healthcare professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4653–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.O.; Sulaiman, A.A. Foot care knowledge, attitude and practices of diabetic patients. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 3816–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letta, S.; Goshu, A.T.; Sertsu, A.; Nigussie, K.; Negash, A.; Yadeta, T.A.; Bulti, F.A.; Geda, B.; Dessie, Y. Diabetes knowledge and foot care practices among type 2 diabetes patients attending the chronic ambulatory care unit of a public health hospital in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, N.; Chung, J.; Evans-Hudnall, G.; Martin, L.A.; Gilani, R.; Poythress, E.L.; Skelton-Dudley, F.; Huggins, J.S.; Trautner, B.W.; Mills, J.L. Engaging patients and caregivers to establish priorities for the management of diabetic foot ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 1388–1395.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartuida, C. The relathionship between duration of diabetes and diabetes self management behaviors. J. Keperawatan Cikini 2021, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facanha, L.O.S.; Lopes, L.S.; Rocha, I.M.; Hasbun, M.R.; Facanha, C. 1899-LB: Diabetic Foot Care—Clinical Profile and Self-Reported Knowledge among Patients with Diabetes Attending a Public Care Centre in the Northeast of Brazil. Diabetes 2025, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, F.M.; AlBassam, K.S.; Alsairafi, Z.K.; Naser, A.Y. Knowledge and practice of foot self-care among patients with diabetes attending primary healthcare centres in Kuwait: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).