Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

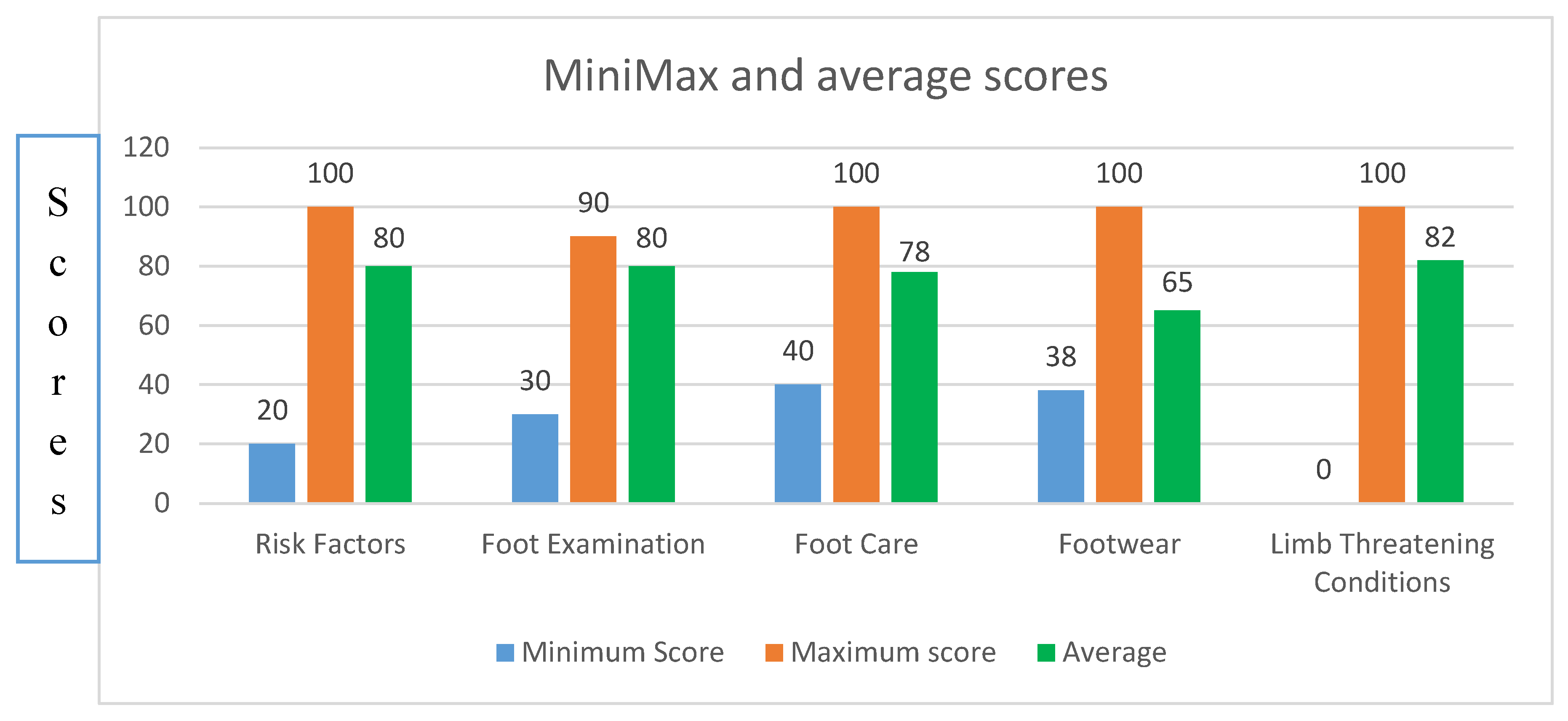

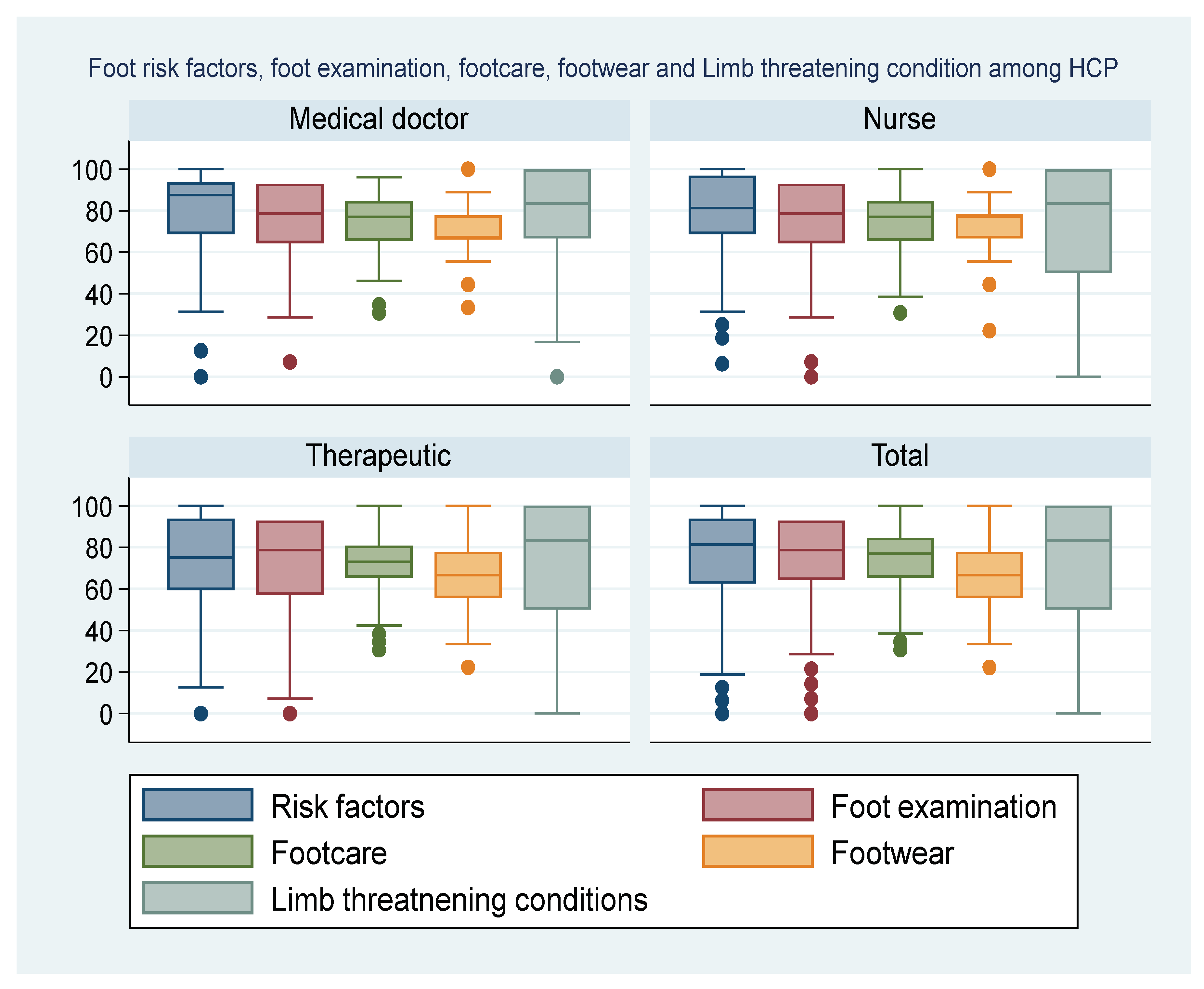

Background/Objective: Prevention of foot ulceration is critical to reduce the rate of amputation in individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM). We investigated knowledge of risk factors and prevention of diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) among healthcare practitioners (HCPs). Methods: This was a prospective cross-sectional observational study using a self-administered questionnaire. Participants were HCPs involved in management of patients with DM. The questionnaire investigated professional background, prior education, knowledge of risk factors DFU, foot care and appropriate footwear. Participants were asked to indicate if they agreed or disagree with a statement. Scores were based on percentage response by each category of HCPs. Knowledge level was classified as very poor if less than 50% of participants from a category of HCPs answered appropriately, reasonable for 50%-59%, average at 60%-69%, above average from 70%-79% and excellent when ≥80%. The chi-square test to compare the knowledge levels across the categories of HCPs. Results: 449 HCPs participated and 48.1% (216/449) were therapeutic health practitioners (THPs), 37.4% (168/449) nurses and 14.5% (65/449) medical doctors. 36% (162/449) of participants had prior education on DFU. Overall knowledge level among participants of risk factors of DFU was 80%, appropriate technique of foot examination 80%, identification of limb-threatening conditions 82%, proper foot care 77% and selection of appropriate footwear 65%. Differences in knowledge levels across HPCs was statistically significant (P <0.05). Conclusion: Majority of HCPs had no prior education on prevention of DFU. The level of knowledge regarding foot care, risk factors and prevention of DFU among HCPs was mostly insufficient.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Prior Training and Provisioning of Health Education to Patients

4. Discussion

4.1. Healthcare Practitioners’ Knowledge of Risk Factors

4.2. Knowledge of Proper Foot Examination Among Healthcare Professions

4.3. Knowledge Levels on Foot Care Among Professional Groups

4.4. Knowledge of Appropriate Selection and Use of Footwear

4.5. Knowledge of Limb-Threatening Conditions Among Healthcare Professionals

4.6. The Strength of the Study

4.7. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFI | Diabetic foot infection |

| DFU | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| HCPs | Healthcare practitioners |

References

- Chaudhary, N.; Huda, F.; Roshan, R.; Basu, S.; Rajput, D.; Kumar Singh, SK. Lower Limb Amputation Rates in Patients With Diabetes and an Infected Foot Ulcer: A Prospective Observational Study. Wound Management & Prevention 2021, 67, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoala, T.C.; Sididzha, V.; Molefe, E.D.; Luvhengo, T.E. Life expectancy of patients with diabetic foot sepsis post-lower extremity amputation at a regional hospital in a South African setting. A retrospective cohort study. Surgeon 2024, 22, e109–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Core, M.D.; Ahn, J.; Lewis, R.B.; Raspovic, K.M. DPM.; Lalli, T.A.J.; Wukich, D.K. The evaluation and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic foot infections. Foot and ankle orthopaedics sage publications inc.2018. [CrossRef]

- Hatem, M.A.; Kamal, D.M.; Yusuf, K.A. Diabetic foot limb-threatening infections: Case Series and management review. International Journal of Surgery Open 48 (2022). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364048837. [CrossRef]

- Pitocco D, Spanu T, Di Leo M, Vitiello R, Rizzi ., Tartaglione L, Fiori B, Caputo S, Tinelli G, Zaccardi F, et al. Diabetic Foot Infections: A Comprehensive Overview. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 26–37. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, J.; Jing, Y.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine, 2017, 49, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan K, Al Derwish M, Ouizi S, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ibrahim HM, et al. Diabetic Foot Complications and Their Risk Factors from a Large Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124446. [CrossRef]

- Grundlingh, N.; Zewotir, T.T.; Roberts, D.J.; Manda, S. Assessment of prevalence and risk factors of diabetes and pre-diabetes in South Africa. J Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. (2022) 41:7. [CrossRef]

- van Netten JJ, Sacco ICN, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, et al. Treatment of modifiable risk factors for foot ulceration in persons with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020, 36, e3271. [CrossRef]

- Korpowska, K.; Majchrzycka, M.; Adamski, Z. The assessment of prophylactic and therapeutic methods for nail infections in patients with diabetes. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postȩpy Dermatologii i Alergologii, 39, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, Sacco ICN, van Netten JJ: Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot.Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020, 36 Suppl 1, e3269. PMID: 32176451. [CrossRef]

- Iraj, B.; Khorvash, F.; Ebneshahidi, A.; Askari, G. Prevention of diabetic foot ulcer. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.Z.M.; Ng, N.S.L.; Thomas, C. Prevention and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J R Soc Med. 2017, 110, 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.; Da Ros, R.; Marfella, R. Update on prevention of diabetic foot ulcer. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis, 2021, 6, e123–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Driscoll, A.; Rasmussen, B. Preventative and early intervention diabetes-related foot care practices in primary care. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, Embil JM, Joseph WS, Karchmer AW. et at. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006, 117 (7 Suppl), 212S–238S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuorlaakso, M.; Kiiski, J.; Salonen, T.; Karppelin, M.; Helminen, M.; Kaartinen, I. Major amputation profoundly increases mortality in patients with diabetic foot infection. Front Surg. 2021, 8, 655902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, AJ.; Armstrong, DG.; Albert, SF.; Frykberg, RG.; Hellman, R.; Kirkman MS, et.al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: a report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31, dc08–dc9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, J.; Sibbald, RG.; Taha, NY.; Lebovic, G. ; Martin.; Bhoj.; Kirton.; Ostrow, B.;Guyana Diabetes and Foot Care Project Team. The Guyana Diabetes and Foot Care Project: improved diabetic foot evaluation reduces amputation rates by two-thirds in a lower middle-income country. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Netten, JJ.; Lazzarini, PA.; Armstrong, DG.; Bus, SA.; Fitridge, R.; Harding, K.; Kinnear, E.; Malone, M.; Menz, HB.; Perrin, BM.; Postema, K.; Prentice, J. Schott KH.; .; Wraight, R. Diabetic Foot Australia guideline on footwear for people with diabetes. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, L.; Driscoll, A.; Wynter, K.; Rasmussen, B. Barriers and enablers to delivering preventative and early intervention footcare to people with diabetes: a scoping review of healthcare professionals’ perceptions. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2019, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby Jacob, A.; Durai, S.; Naik, D. Awareness and practices of footwear among patients with diabetes and a high-risk foot. The Diabetic Foot Journal 2020, 23, 46–56.

- de Guzman, M.; Ebison Jr, A.; Narvacan-Montano, C. Footwear appropriateness, preferences and foot ulcer risk among adult diabetics at Makati Medical Center Outpatient Department. J ASEAN Federation Endocr Soc. 2016, 31, 37–7. [CrossRef]

- Buldt, AK.; Menz, HB. Incorrectly fitted footwear, foot pain and foot disorders: a systematic search and narrative review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundram, ER.; Sidek, MY.; Yew, TS. Types and grades of footwear and factors associated with poor footwear choice among diabetic patients in USM hospital. Int J Public Health Clin Sci. 2018, 5, 135–44. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, A.; Naemi, R.; Chockalingam, N. The effectiveness of footwear as an intervention to prevent or to reduce biomechanical risk factors associated with diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review. J Diabetes Complicat. 2013, 1, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgetto, JV.; Gamba, MA.; Kusahara, DM. Evaluation of the use of therapeutic footwear in people with diabetes mellitus – a scoping review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019, 18, 613–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guell, C.; Unwin, N. Barriers to diabetic foot care in a developing country with a high incidence of diabetes related amputations: an exploratory qualitative interview study. BMC Health Services Research 2015, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Driscoll, A.; Wynter, K.; Rasmussen, B. Barriers and enablers to delivering preventative and early intervention footcare to people with diabetes: a scoping review of healthcare professionals’ perceptions. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2019, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, A.; Prajapati, B.; Dharamsi, A.; Sompura, K. (2024). A Comprehensive Approach for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Management. Current Drug.2024. Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri-Tehrani, MR.; Aalaa, M.; Mohseni, SH.; Larijani, B.; Anabestani, Z. Multidisciplinary Approach in Diabetic Foot Care in Iran (New Concept). Iranian Journal of Public Health, 2012, 41, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Somayaji, R.; Elliott, JA.; Persaud, R.; Lim, M.; Goodman, L.; Sibbald, RG. The impact of team based interprofessional comprehensive assessments on the diagnosis and management of diabetic foot ulcers: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, M.; Paola, LP. ; Martínez JLL. Meeting-report-go-beyond-multidisciplinary-approach-management-diabetic-foot-ulcers. Wounds International 2018 | Vol 9 Issue 3 | ©Wounds International 2018 | www.woundsinternational.

- Alsaigh, SH.; Alzaghran, RH.; Alahmari, DA.; Hameed, LN.; Alfurayh, KM.; Alaq, KB. Knowledge, awareness, and practice related to diabetic foot ulcer among healthcare workers and diabetic patients and their relatives in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2022, 14, 1–11 107759/cureus32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureen, R.; Warsi, M.; Nazir, A.; Mukhtar, M. (2023). Knowledge and practice related to diabetic foot ulcers among healthcare providers in a public hospital of pakistan. Biological and Clinical Sciences Research Journal (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ranuve, MS.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Healthcare workers’ perceptions on diabetic foot ulcers (dfu) and foot care in Fiji: a qualitative study. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Ertuǧrul, MB. : The role of rehabilitation in the management of diabetic foot wounds. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021, 67, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, Y.; Ertugrul, BM.; Lipsky, BA.; Bayrakatar, K. Does physical therapy and rehabilitation improve outcomes for diabetic foot ulcers? World J Exp Med 2015, 5, 130–139. Available online: http://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315X/full/v5/i2/130.htm. [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, RW.; Bouwman, EF. Diabetic foot care within the context of rehabilitation: keeping people with diabetic neuropathy on their feet. A narrative review. A narrative review. Physical Therapy Reviews 2017, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, PR.; Bus, SA. Off-loading the diabetic foot for ulcer prevention and healing. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2010, 52, 375–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Du, C.; Fan, X.; Cui, L.; Chen, H.; eDeng, F.; Tong, Q.; He, M.; Yang, M.; Tan, X.; Li, L.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Armstrong, D.G.; Deng, W. Custom-Moulded Offloading Footwear Effectively Prevents Recurrence and Amputation, and Lowers Mortality Rates in High-Risk Diabetic Foot Patients: A Multicenter, Prospective Observational Study. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 2022, 15, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bus, SA.; Armstrong, DG.; Gooday, C.; Jarl, G.; Caravaggi, CF.; Viswanathan, V.; Lazzarini, PA. IWGDF Guideline on offloading foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. 2019, ID: 199047365. www.iwgdfguidelines.org.

- Wu, S.; Jensen, JL.; Weber, AK.; Robinson, D.; Armstrong, DG. Use of Pressure Offloading Devices in Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2118–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dee, T.M. .; Fiah, F.M.A.; Pandie, F.R. Foot exercise and related outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing and Health Services (IJNHS) Volume 5, Issue 5, October 20th, 2022.

- Liao, F.; An, R.; Pu, F.; Burns, S.; Shen, S.; Jan, YK. Effect of exercise on risk factors of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019, 98, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Mendes, R.; Silva, AB.; Sousa, N. Physical activity and exercise on diabetic foot related outcomes: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018, 139, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otterman, NM. van Schie CHM.; van der Schaaf, M.; van Bon AC.; Busch-Westbroek TE.; Nollet, F. An exercise programme for patients with diabetic complications: A study on feasibility and preliminary effectiveness. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakiudin, A.; Irianto, G.; Badrujamaludin, A.; Rumahorbo, H.; Susilawati, S. Foot Exercise to Overcome Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A literature Review. International Journal of Nursing Information 2022, 1, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, R.; Spicer, M.T.; Ledermann, T.; Arjmandi, B.H. (2022). Effects of Nutrition Intervention on Blood Glucose, Body Composition, and Phase Angle in Obese and Overweight Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Basiri, R.; Spicer, M.T.; Muñoz, J.; Arjmandi, B.H. (2020). Nutritional Intervention Improves the Dietary Intake of Essential Micronutrients in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Current Developments in Nutrition.2020. [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.H.; Park, S.; Woo, J.T.; Choue, R. A comparative study of diet in good and poor glycemic control groups in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Korean Diabetes, J. 2010, 34, 303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amman, A.S.; Khalid, R.; Malik, U.; Zeb, M.; Abbas, H.M.; Khattak, S.B. Predictors of lower limb amputations in patients with diabetic foot ulcers presenting to a tertiary care hospital of Pakistan. JPMA 2021, 71, 2163. [Google Scholar]

- Suryawanshi, D. , Mahey, D.T., Bakale, D.S., Alva, D. (2023). A clinical study of Diabetic foot patients who underwent amputations in tertiary care center- An observational study. International Journal of Surgery and Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Mustamu, A.C.; Samaran, E.; Bistara, D.N. Impact of Poor Glycemic Control and Vascular Complications on Diabetic Foot Ulcer Recurrence", Journal of Angiotherapy, 2024, 8, 9854.

- Untari EK, Andayani TM, Yasin NM, Asdie RH. (2024). Factors affecting self-care behaviours of ulcer prevention and glycemic control among diabetes mellitus patients at type A hospital in Yogyakarta. Pharmacy Education, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sutkowska, E.E.; Sokolowski, M.; Zdrojowy, K.; Dragan, S. Active screening for diabetic foot - assessment of health care professionals’ compliance to it. Clinical diabetology. Clinical Diabetology 2016, 5, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.A.; Tsubane, M. The role of the podiatrist in managing the diabetic foot ulcer: podiatry. Wound Healing Southern Africa, Corpus ID: 70625912. 2008; 1, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Korpowska, K.; Majchrzycka, M.; Adamski, Z. The assessment of prophylactic and therapeutic methods for nail infections in patients with diabetes. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postȩpy Dermatologii i Alergologii. 39, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Nenoff P, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, Tietz HJ. [Fungal nail infections--an update: Part 1--Prevalence, epidemiology, predisposing conditions, and differential diagnosis]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2012; 63, 30–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Peng, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Hu, J. Gait Parameters and Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients With Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanasundaram, S.; Ramalingam, P.; Das, B.N.; Viswanathan, V. Gait changes in persons with diabetes: Early risk marker for diabetic foot ulcer. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020, 26, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere-Bigorra M, Brognara L, Julián-Rochina I, MazzottiA , Cauli, O. Relationship between deep and superficial sensitivity assessments and gait analysis in diabetic foot patients. International Wound Journal 2023, 20, 3023–3034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, N.D.; Orlando, G.; Brown, S.J. Sensory-Motor Mechanisms Increasing Falls Risk in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Medicina, 57. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tavares NM, Silva JM, Silva MD, Silva LD, Souza JN, Ithamar, L.; Raposo, M.C.F.; Melo RS. Balance, Gait, Functionality and Fall Occurrence in Adults and Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Associated Peripheral Neuropathy. Clinics and Practice, 2024; 14, 2044–2055. [CrossRef]

- Mafusi LG, Egenasi CK, Steinberg WJ, Benedict, M.O.; Habib, T.; JHarmse, M.; Van Rooyen, C. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on diabetic foot care among nurses in Kimberley. South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract. 2024, 66, a5935.

- Mothiba, M.M.; Skaal, M.M.; Moshabela, M.M. Knowledge and Practices of Nurses Regarding Diabetic Foot Care in a Public Hospital in South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 2015, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt M, Suhonen R, Pauli Puukka, Viitanen P, Voutilainen P, Leino-Kilpi, H. Nurses’ Knowledge of Foot Care in the Context of Home Care: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Survey Study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2015, 24, 2916–2925. [CrossRef]

- Wui NB, Azhar AA bin, Azman MH bin, Sukri MS bin, Singh ASAH, Abdul Wahid AM bin. Knowledge and attitude of nurses towards diabetic foot care in a secondary health care centre in Malaysia. MedJ Malaysia. 2020, 75, 391–395.

- Aalaa, M.; Malazy, O.T.; Sanjari, M.; Peimani, M.; Mohajeri-Tehrani, M. Nurses’ role in diabetic foot prevention and care; a review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2012, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, K.W. , Choirunnisak, D.R., Fiddaroini, F.N., & Puspita, E. (2024). Analysis of nursing care in diabetes mellitus patients through diabetic foot exercise intervention for blood circulation improvement in Teratai Room, Ihc Rsu Wonolangan Probolinggo. Literasi Kesehatan Husada: Jurnal Informasi Ilmu Kesehatan. [CrossRef]

- Arosi, I.; Hiner, G.; Rajbhandari, M. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Callus in the Diabetic Foot. Current diabetes reviews 2016, 12, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatoprak, A.P.; Aydin, L.; Yüksel, B.; Demirhan, Y.; Baydemir, C.; Selek, A.; Cantürk, Z.; Çetinarslan, B. Evaluation of the foot health with baropodometric analysis of acromegaly patients followed after pituitary surgery. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Haseeb, A.; Rehman, A.; Hussham Arshad, M.; Aslam, A.; Godil, S.; Qamar, M. A Husain, S.N.; Polani, M.H.; Ayaz, A.; Ghazanfar, .; Ghazali, ZM.; Khoja, KA.; Malik, M.; Ahmsad, H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among nurses in Pakistan towards diabetic foot. Cureus 2018, 10, e3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgwood, B.; Houghton JSM.; Nduwayo, S.; Pepper, C.; Payne, T.; Bown MJ.; Davies RSM.; Sayers RD. A systematic review investigating the identification, causes, and outcomes of delays in the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia and diabetic foot ulceration. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 669–681.e2. [CrossRef]

- Markanday, A. Diagnosing Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis: Narrative Review and a Suggested 2-Step Score-Based Diagnostic Pathway for Clinicians, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 1, Issue 2, Summer 2014, ofu060. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Medical doctors | 65(14.5%) |

| Nurses | 168(37.4%) |

| Therapeutic health practitioners | 216(48.1%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 120(26.7%) |

| Female | 320(71.3%) |

| Not specified | 9(2%) |

| Service unit | |

| Polyclinic | 70(15.6%) |

| Rehabilitation unit | 150(33.4%) |

| Therapeutic unit | 56(12.5%) |

| Medical-related unit | 90(20%) |

| Surgical-related unit | 32(7.1%) |

| Not specified | 51(11.4%) |

| Variable | Total | Medical doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health Practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior training in diabetic foot care | |||||

| No Yes Not specified |

284(63.3%) 157(35%) 8(1.8%) |

37(57%) 26(40%) 2(0.4%) |

96(59%) 68(41%) 8(4.8%) |

151(71%) 63(29%) 2(0.9%) |

0.032 |

| Training platform and nature | |||||

| Undergraduate | 78(17.3%) | 30(46.2%) | 24(114.3%) | 24(11.1%) | |

| Short course | 36(5.8%) | 5(7.7%) | 18(10.7%) | 13(6%) | |

| Workshops, in-service training, seminars, symposium or CPD activities | 17(3.8%) | 0(0%) | 4(2.4%) | 11(5.1%) | |

| On-site training or self-training | 19(4.2%) | 0(0%) | 9(5.4%) | 10(4.6%) | |

| Education of patients on foot care | |||||

| No Yes |

153 (35%) 284 (65%) |

13(20%) 52(80%) |

54(34%) 107(66%) |

86 (41%) 125 (59%) |

0.008 |

| Risk Factors Variables | Total | Medical doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor glycaemic control No Yes |

82(18%) 367 (82%) |

3(5%) 62(95%) |

31(18%) 137(82%) |

48(22%) 168(78%) |

0.002 |

| Pain, burning, tingling, or tenderness of foot No Yes |

69(15%) 380(85%) |

10(15%) 55(85%) |

21(13%) 147(87%) |

38(18%) 178(82%) |

0.390 |

| Peripheral vascular desease No Yes |

85(19%) 364(81%) |

5(8%) 60(92%) |

35(21%) 133(79%) |

45(21%) 171(79%) |

0.044 |

| Presence of callus No Yes |

201(45%) 248(55%) |

24(37%) 41(63%) |

67(40%) 101(60%) |

110(51%) 106(49%) |

0.038 |

| Dry or cracked skin No Yes |

154(34%) 295(66%) |

16(25%) 49(75%) |

47(28%) 121(72%) |

91(42%) 125(58%) |

0.003 |

| Previous DFU on same foot or opposite extremity No Yes |

95(21%) 354(79%) |

8(12%) 57(88%) |

40(24%) 128(76%) |

47(22%) 169(78%) |

0.149 |

| Evidence of infection like redness, tenderness, and temperature increase No Yes |

67(15%) 382(85%) |

4(6%) 61(94%) |

23(14%) 145(86%) |

40(19%) 176(81%) |

0.037 |

| Walking barefoot, bad shoes, foreign object inside shoes No Yes |

99(22%) 350(78%) |

9(14%) 56(86%) |

31(18%) 137(82%) |

59(27%) 157(73%) |

0.026 |

| Mallet or claw toes, hallux valgus, previous amputation, Charcot deformity or low foot No Yes |

189(42) 260(58) |

18(28) 47(72) |

71(42) 97(58) |

100(46) 116(54) |

0.029 |

| Neuropathic foot No Yes |

44(10) 405(90) |

2(3) 63(97) |

21(13) 147(87) |

21(10) 195(90) |

0.077 |

| Foot examination | Total | Medical doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic health practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking No Yes |

75(17%) 374(83%) |

4(6%) 61(94%) |

32(19%) 136(81%) |

39(18%) 177(82%) |

0.033 |

| Age of 65 and over No Yes |

133(30%) 315(70%) |

14(22%) 51(78%) |

53(32%) 114(68%) |

66(31%) 150(69%) |

0.289 |

| Obesity No Yes |

93(21%) 356(79%) |

13(20%) 52(80%) |

33(20%) 135(80%) |

47(22%) 169(78%) |

0.869 |

| Patients not trained/educated in diabetic foot No Yes |

7(22%) 352(78%) |

9(14%) 56(86%) |

42(25%) 126(75%) |

46(21%) 170(79%) |

0.177 |

| Oedematous, atrophic or dry skin, fissures and calluses No Yes |

36(8%) 413(92%) |

1(2%) 64(98%) |

16(10%) 152(90%) |

19(9%) 197(91%) |

0.093 |

| Pale, red or cyanotic skin No Yes |

40(9%) 409(91%) |

3(5%) 62(95%) |

19(11%) 149(89%) |

18(8%) 198(92%) |

0.273 |

| Foot that is warm or cold to touch No Yes |

58(13%) 391(87%) |

5(8%) 60(92%) |

25(15%) 143(85%) |

29(13%) 187(87%) |

0.341 |

| Pain, tingling or burning, tenderness, sensory loss No Yes |

44(10%) 405(90%) |

2(3%) 63(97%) |

21(13%) 147(87%) |

21(10%) 195(90%) |

0.077 |

| Muscle atrophy due to damage in muscles No Yes |

118(26%) 331(74%) |

15(23%) 50(77%) |

39(23%) 129(77%) |

64(30%) 152(70%) |

0.300 |

| Palpation of posterior tibial and dorsal pedis pulse No Yes |

84(19%) 365(81%) |

7(11%) 58(89%) |

30(18%) 138(82%) |

47(22%) 169(78%) |

0.129 |

| Feel for temperature increase, redness or edema No Yes |

47(10%) 402(90%) |

4(6%) 61(94%) |

14(8%) 154(92%) |

29(13%) 187(87%) |

0.145 |

| Checking for foot deformities like hammer or claw toes and hallux valgus No Yes |

126(28%) 323(72%) |

12(18%) 53(82%) |

43(26%) 125(74%) |

71(33%) 145(67%) |

0.051 |

| Assessment of toenails for thickening, ingrown, and length of the nails No Yes |

147(33%) 301(67%) |

18(28%) 47(72%) |

40(24%) 128(76%) |

89(41%) 126(59%) |

0.001 |

| Shoe suitability assessment No Yes |

83(18%) 366(82%) |

9(14%) 56(86%) |

25(15%) 143(85%) |

49(23%) 167(77%) |

0.086 |

| Foot joints ranges of motion No Yes |

121(27%) 327(73%) |

14(22%) 51(78%) |

47(28%) 120(72%) |

60(28%) 156(72%) |

0.560 |

| Gait assessment No Yes |

154(34%) 295(66%) |

12(18%) 53(82%) |

68(40%) 100(60%) |

74(34%) 142(66%) |

0.006 |

| Proprioceptive assessment No Yes |

153(34%) 295(66%) |

6(9%) 59(91) |

87(52%) 81(48%) |

60(28%) 155(72%) |

0.000 |

| Foot care | Total | Medical Doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health Practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily check of foot by patient or a relative for callus or cracks No Yes |

38(8%) 411(92%) |

4(6%) 61(94%) |

12(7%) 156(93%) |

22(10%) 194(90%) |

0.511 |

| Feet should be washed daily with warm water No Yes |

108(24%) 341(76%) |

22(34%) 43(64%) |

29(17%) 139(83%) |

57(26%) 159(74%) |

0.016 |

| Temperature for washing feet should be checked before hand No Yes |

64(14%) 385(86%) |

6(9%) 59(91%) |

14(8%) 154(92%) |

44(20%) 172(80%) |

0.002 |

| Feet, especially spaces between toes, should be dried after each wash No Yes |

44(10%) 405(90%) |

4(6%) 61(94%) |

13(8%) 155(92%) |

27(13%) 189(87%) |

0.189 |

| Moisturising cream must be applied to feet No Yes |

83(18%) 366(82%) |

18(28%) 47(72%) |

22(13%) 146(87%) |

43(20%) 173(80%) |

0.028 |

| Moisturising cream must be applied to toes No Yes |

247(55%) 202(45%) |

31(48%) 24(52%) |

100(60%) 68(40%) |

116(54%) 100(46%) |

0.230 |

| Toes must be kept dry to prevent fungal infections No Yes |

65(14%) 384(86%) |

10(15%) 55(85%) |

19(11%) 149(89%) |

36(17%) 100(83%) |

0.326 |

| Cutting tools and chemicals should not be used to remove calluses or hardened skin areas No Yes |

171(38%) 278(62) |

21(32%) 44(68) |

59(35%) 109(65%) |

91(42%) 125(58%) |

0.218 |

| Callus stiffness should be thinned with a pumice stone No Yes |

190(42%) 259(58%) |

26(40%) 39(60%) |

77(46%) 91(54%) |

87(40%) 129(60%) |

0.506 |

| Exercise in the form of twisting and stretching toes several times a day should be done No Yes |

263(59%) 186(41%) |

30(46%) 35(54%) |

115(68%) 53(32%) |

118(55%) 98(45%) |

0.002 |

| Prevention of foot corn and callus formation No Yes. |

126(28%) 323(72%) |

13(20%) 52(80%) |

37(22%) 131(78%) |

76(35%) 140(65%) |

0.005 |

| There is no inconvenience to use callus band and plaster No Yes |

143(32%) 305(68%) |

22(34%) 43(66%) |

70(42%) 97(58%) |

51(24%) 165(76%) |

0.001 |

| Only socks should be worn to warm the feet No Yes |

227(51%) 222(49%) |

34(52%) 31(48%) |

61(36%) 106(64%) |

132(61%) 84(39%) |

0.000 |

| Direct heat sources like radiators, hot-water bottle and electrical appliances should be used to warm feet No Yes |

88(20%) 361(80%) |

11(17%) 54(83%) |

41(24%) 127(76%) |

36(17%) 180(83%) |

0.140 |

| Socks should not be torn, wrinkled or oversized, and should be checked for wetness and colour change, and changed everyday No Yes |

112(25%) 337(75%) |

23(35%) 42(65%) |

29(17%) 139(83%) |

60(28%) 156(72%) |

0.007 |

| Tight rubber socks should be avoided No Yes |

164(37%) 285(63%) |

26(40%) 39(60%) |

48(29%) 120(71%) |

90(42%) 126(58%) |

0.025 |

| Walking bare feet is prohibited No Yes |

167(37%) 282(63%) |

19(29%) 46(71%) |

35(21%) 133(79%) |

113(52%) 103(48%) |

0.000 |

| Pressure on feet should be removed by not standing for long periods No Yes |

143(32%) 306(68%) |

23(35%) 42(65%) |

35(21%) 133(79%) |

85(39%) 131(61%) |

0.000 |

| Legs should not be crossed when sitting on a chair No Yes |

220(49%) 229(51%) |

41(63%) 24(37%) |

60(36%) 108(64%) |

119(55%) 97(45%) |

0.000 |

| If there is clawing of toes, massage should not be done to prevent joint stiffness No Yes |

133(30%) 316(70%) |

12(18%) 53(82%) |

66(39%) 102(61%) |

55(25%) 161(75%) |

0.001 |

| Toenails should be controlled in terms of thickening, ingrowth, and length, they should be cut flat and, in the corners No Yes |

117(26%) 332(74%) |

24(37%) 41(63%) |

34(20%) 134(80%) |

59(27%) 157(73%) |

0.029 |

| The thickened nails should be cut with a special scissors after being softened in warm water No Yes |

132(29%) 317(71%) |

19(29%) 46(71%) |

44(26%) 124(74%) |

69(32%) 147(68%) |

0.470 |

| Toe web spaces need to be kept moist No Yes |

137(31%) 312(69%) |

13(20%) 52(80%) |

61(36%) 107(64%) |

63(29%) 153(71%) |

0.044 |

| Any changes to feet and toes of colour, temperature, or shape and signs of infection should be reported to the doctor immediately No Yes |

65(14%) 384(86%) |

12(18%) 53(82%) |

19(11%) 149(89%) |

34(16%) 182(84%) |

0.290 |

| Foot exercises should be done daily to help the circulation No Yes |

87(19%) 362(81%) |

21(32%) 44(68%) |

29(17%) 139(83%) |

37(17%) 179(83%) |

0.017 |

| In case of any foot lesion, shoes must be replaced to reduce the load on feet No Yes |

154(34%) 295(65%) |

14(22%) 51(78%) |

76(45%) 92(55%) |

64(30%) 152(70%) |

0.000 |

| Smoking is strictly forbidden since it reduces the amount of blood going to feet No Yes |

101(22%) 348(78%) |

14(22%) 51(78%) |

35(21%) 133(79%) |

52(24%) 164(76%) |

0.737 |

| Footwear variables | Total | Medical doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoes should fit and grasp feet No Yes |

215(48%) 234(52%) |

33(51%) 32(49%) |

82(49%) 86(51%) |

100(46%) 116(54%) |

0.782 |

| High-heeled shoes should be preferred No Yes |

38(8%) 411(92%) |

5(8%) 60(92%) |

20(12%) 148(88%) |

13(6%) 203(94%) |

0.117 |

| New shoes should be worn and allow feet to get used to them No Yes |

194(43%) 255(57%) |

29(45%) 36(55%) |

79(47%) 89(53%) |

86(40%) 130(60%) |

0.357 |

| Shoes should be painted frequently No Yes |

62(14%) 387(86%) |

8(12%) 57(88%) |

23(14%) 145(86%) |

31(14%) 185(86%) |

0.915 |

| If there is a deformity in the foot, a doctor should be consulted for proper treatment or orthopaedic shoes No Yes |

89(20%) 360(80%) |

14(22%) 51(78%) |

27(16%) 141(84%) |

48(22%) 168(78%) |

0.303 |

| A shoe should not lose its exterior protection feature No Yes |

142(32%) 307(68%) |

21(32%) 44(68%) |

55(33%) 113(67%) |

66(31%) 150(69%) |

0.894 |

| Shoes should be worn without socks and, if shoe insoles are worn out, they should be replaced No Yes |

365(81%) 84(19%) |

55(85%) 10(15%) |

127(76%) 41(24%) |

183(85%) 22(15%) |

0.057 |

| Soft-skinned and comfortable shoes should be preferred No Yes |

71(16%) 378(86%) |

11(17%) 54(83%) |

27(16%) 141(86%) |

33(15%) 183(85%) |

0.944 |

| Shoes should be checked for foreign bodies such as nail, gravel, etc. before each wear No Yes |

59(13%) 389(87%) |

5(8%) 60(92%) |

25(15%) 142(85%) |

29(13%) 187(87%) |

0.334 |

| Variables for Limb threatening conditions | Total | Medical doctor | Nurses | Therapeutic Health practitioners | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic limb ischemia No Yes |

93(21%) 357(79%) |

9(14%) 56(86%) |

37(22%) 131(78%) |

47(22%) 169(78%) |

0.335 |

| Osteomyelitis No Yes |

166(37%) 283(63%) |

8(12%) 57(88%) |

58(35%) 110(65%) |

100(46%) 116(54%) |

<0.0001 |

| Extensive soft tissue loss No Yes |

107(24%) 342(76%) |

7(11%) 58(89%) |

41(24%) 127(76%) |

59(27%) 157(73%) |

0.023 |

| Rapid progression of infection No Yes |

156(35%) 293(65%) |

23(35%) 42(65%) |

58(35%) 110(65%) |

75(35%) 141(65%) |

0.992 |

| Extensive bony destruction of the foot No Yes |

128(29%) 321(71%) |

15(23%) 50(77%) |

49(29%) 119(71%) |

64(30%) 152(70%) |

0.574 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).