Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

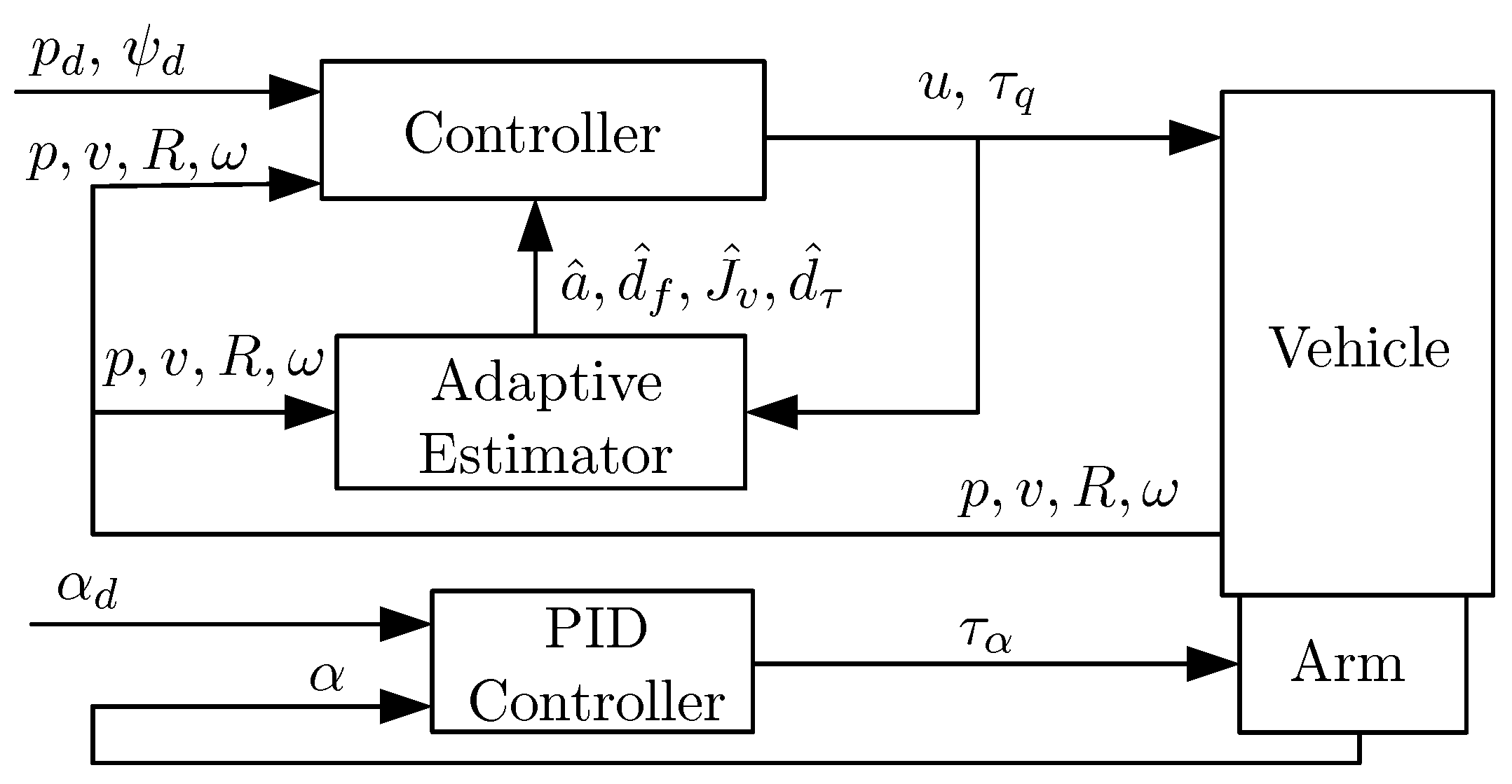

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

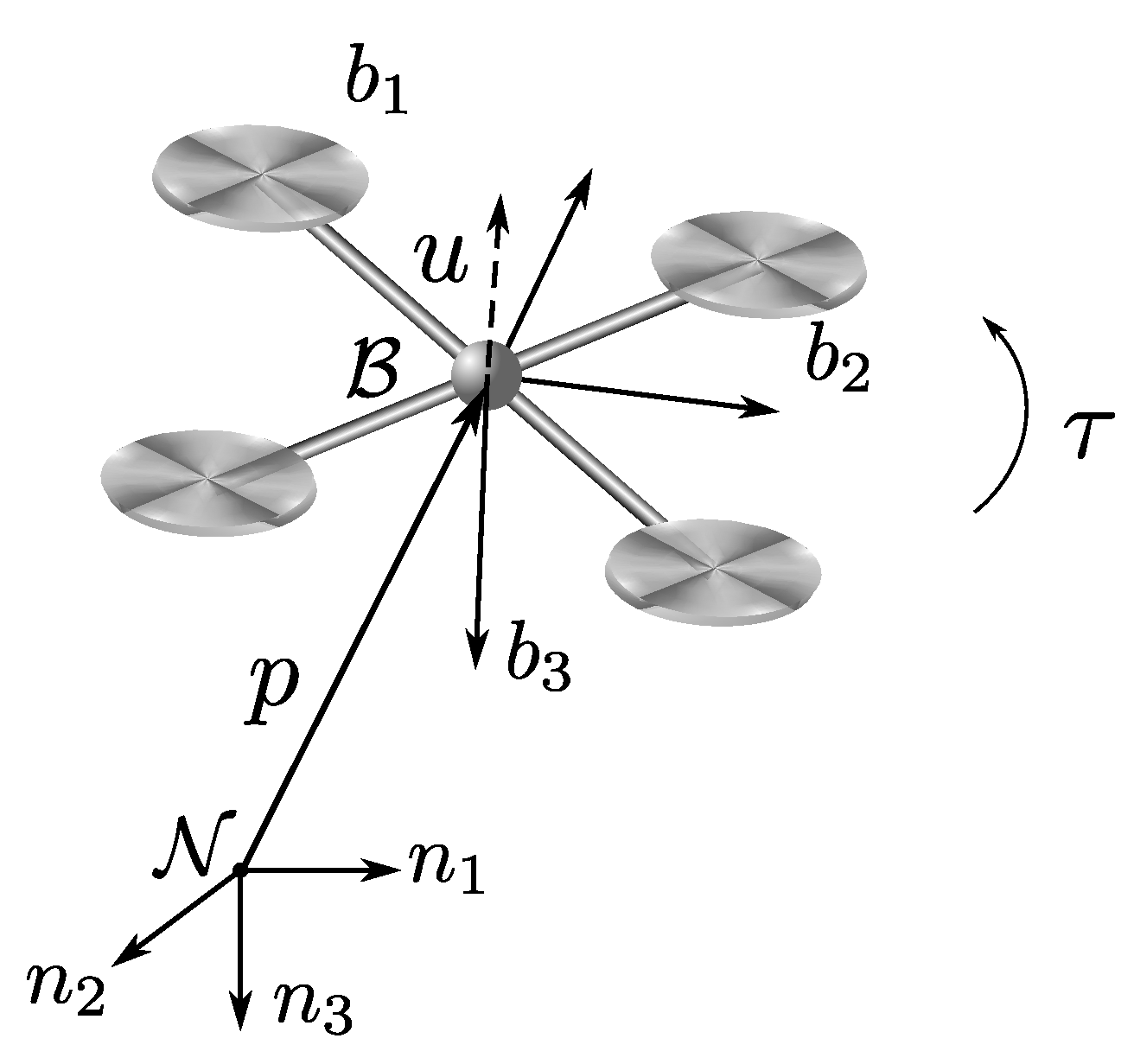

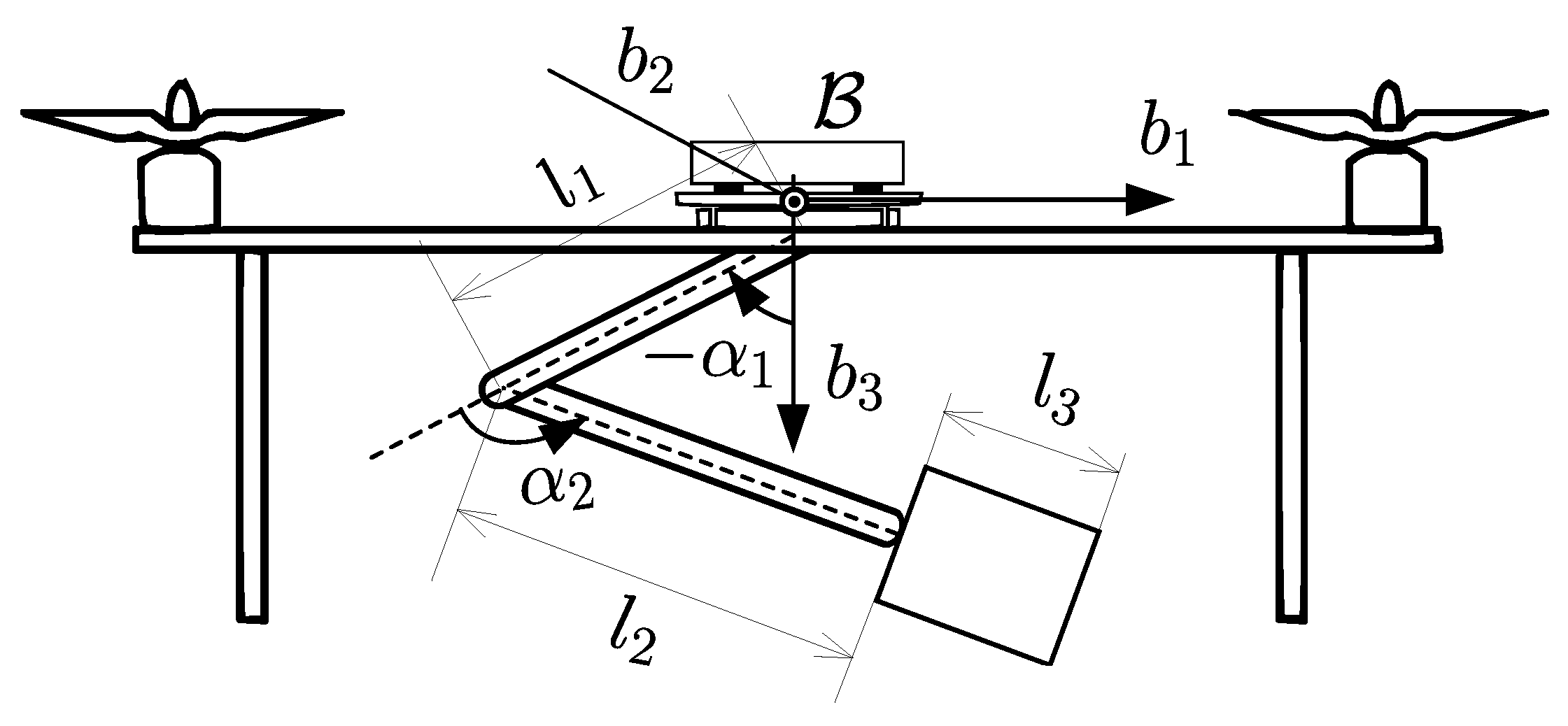

2. Modelling

3. Control Design

3.1. Position Tracking Control

3.2. Position and Yaw Tracking Control

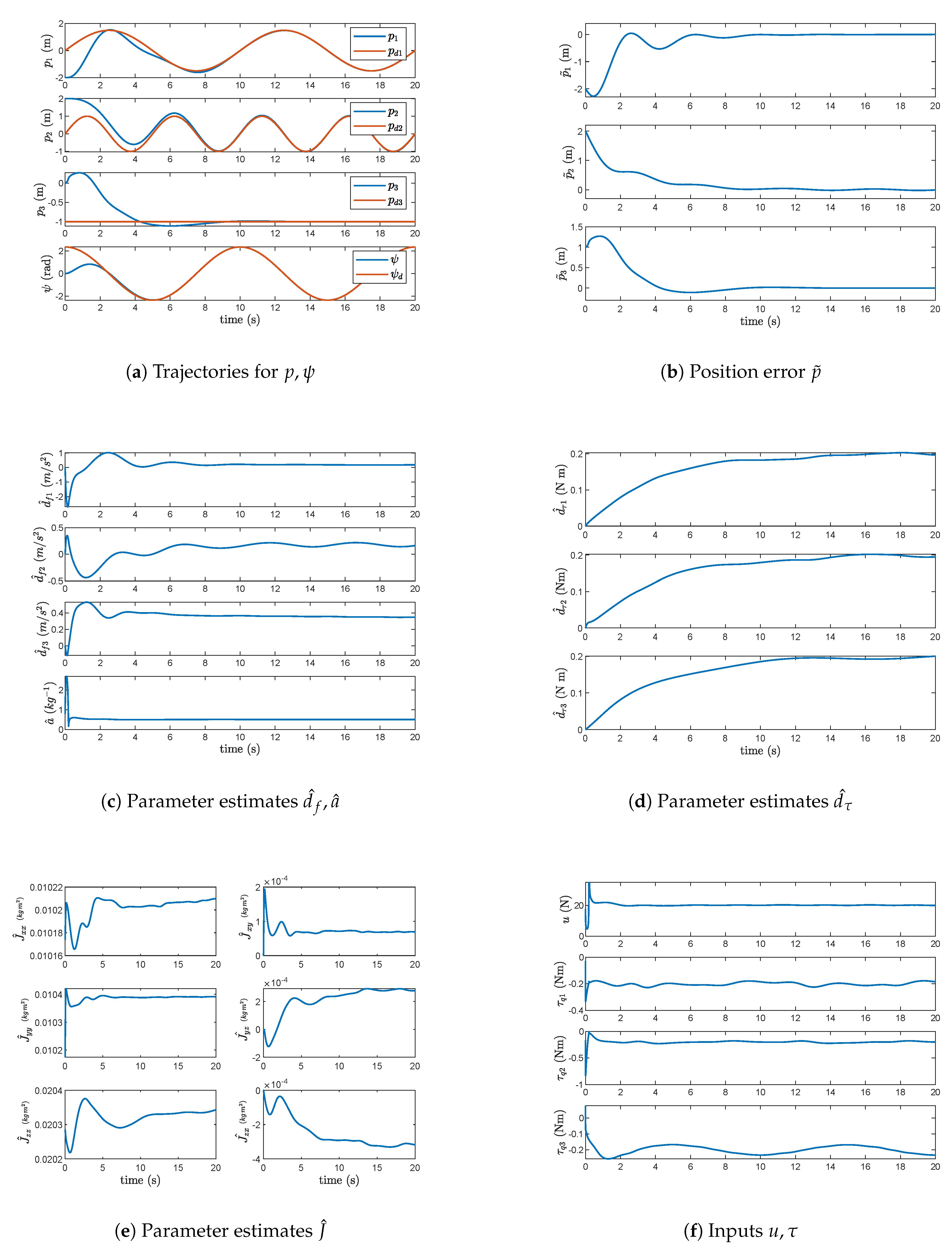

4. Simulation Results

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| m | 1.6 | , | 0.03 |

| 0.05 | , , | 0.0 |

| Parameter | Link 1 | Link 2 | Link 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Type | Revolute | Revolute | Fixed |

| Mass () | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Length () | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Inertia () |

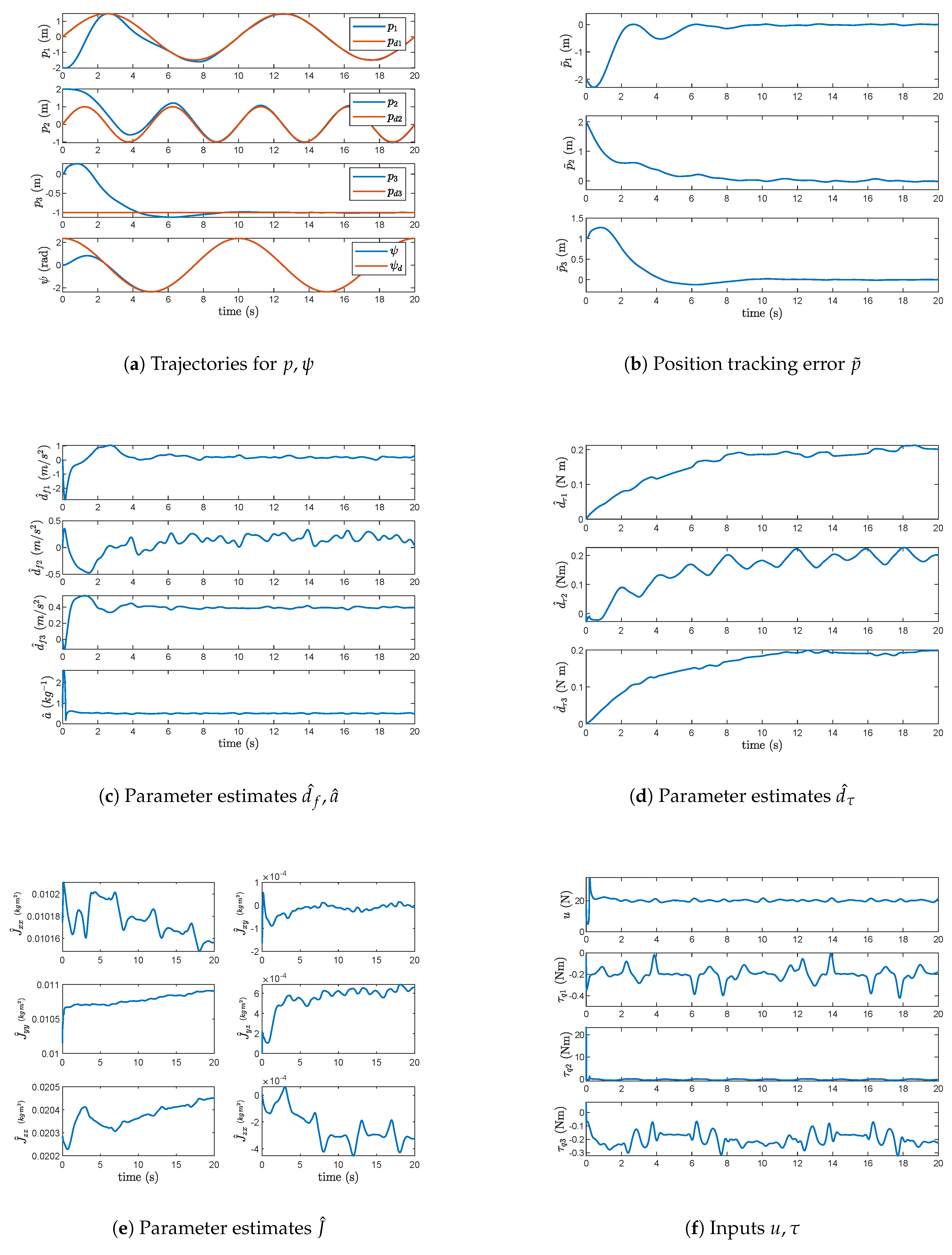

4.1. Figure-8 Reference Trajectory

5. Conclusion

References

- Albers, A.; Trautmann, S.; Howard, T.; Frietsch, M.; Sauter, C. Semi-autonomous flying robot for physical interaction with environment. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics, June 2010, pp. 441–446. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Lee, D. Hybrid force/motion control and internal dynamics of quadrotors for tool operation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nov 2013; pp. 3458–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Ha, C.; Lee, D. Mechanics, control and internal dynamics of quadrotor tool operation. Automatica 2015, 61, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, A.Y.; Stramigioli, S.; Carloni, R. Variable impedance control for aerial interaction. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Sep. 2014; pp. 3435–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, C.; Alexis, K.; Tzes, A. Efficient force exertion for aerial robotic manipulation: Exploiting the thrust-vectoring authority of a tri-tiltrotor UAV. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), May 2014; pp. 4500–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.; Shim, H.; Kim, H.J. Robust Control of an Equipment-Added Multirotor Using Disturbance Observer. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2018, 26, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Cano, A.E.; Martin, J.; Heredia, G.; Ollero, A.; Cano, R. Control of an aerial robot with multi-link arm for assembly tasks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, May 2013; pp. 4916–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, C.; Orsag, M.; Pekala, M.; Oh, P. Dynamic stability of a mobile manipulating unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, May 2013; pp. 4922–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Olivares-Mendez, M.A.; Voos, H. Modeling and Control of Aerial Manipulation Vehicle with Visual sensor. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2013, 46, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Alma, M.; Olivares-Mendez, M.A.; Voos, H. Adaptive control of Aerial Manipulation Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Nov 2014, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE 2014); pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Fanni, M.; Ramadan, A.; Abo-Ismail, A. Modeling and control of a new quadrotor manipulation system. In Proceedings of the 2012 First International Conference on Innovative Engineering Systems, Dec 2012; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadikhoshkho, Z.; Ghorbani, S.; Janabi-Sharifi, F.; Zareinia, K. Nonlinear control of aerial manipulation systems. Aerospace Science and Technology 2020, 104, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippiello, V.; Ruggiero, F. Exploiting redundancy in Cartesian impedance control of UAVs equipped with a robotic arm. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Oct 2012; pp. 3768–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippiello, V.; Ruggiero, F. Cartesian Impedance Control of a UAV with a Robotic Arm. In Proceedings of the 10th International IFAC Symposium on Robot Control; 2012; pp. 704–709. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.J. Aerial manipulation using a quadrotor with a two DOF robotic arm. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nov 2013; pp. 4990–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, D. Dynamics and control of quadrotor with robotic manipulator. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), May 2014; pp. 5544–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, C.; Orsag, M.; Oh, P. Towards valve turning using a dual-arm aerial manipulator. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Sep. 2014; pp. 3411–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Back, J.; Choy, I. Nonlinear disturbance observer based robust attitude tracking controller for quadrotor UAVs. International Journal of Control, Automation and Systems 2014, 12, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallah, S.; Siegwart, R. Backstepping and Sliding-mode Techniques Applied to an Indoor Micro Quadrotor. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation. IEEE; 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraban, G.; Sheckells, M.; Kim, S.; Kobilarov, M. Adaptive Parameter Estimation for Aerial Manipulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the American Control Conference, 2020, pp. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Munoz, J.; Marchand, N.; Guerrero-Castellanos, J.F.; Tellez-Guzman, J.J.; Escareno, J.; Rakotondrabe, M. Rotorcraft with a 3DOF Rigid Manipulator: Quaternion-based Modeling and Real-time Control Tolerant to Multi-body Couplings. International Journal of Automation and Computing 2018, 15, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrlík, M.; Báča, T.; Heřt, D.; Vrba, M.; Krajník, T.; Saska, M. A robust UAV system for operations in a constrained environment. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Ren, B. Wind turbine crack inspection using a quadrotor with image motion blur avoided. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 8, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, A.; Lynch, A.; Zhao, Q. Disturbance Observer-based Nonlinear Control of a Quadrotor UAV. Adv. Control Appl. 2019, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, A.; Rafique, M.A.; Xue, Z.; Lynch, A.F.; Zhao, Q. Disturbance Observer-Based Integral Backstepping Control for UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS); 2020; pp. 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.A. Adaptive Nonlinear Control for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Visual Servoing and Aerial Manipulation. Ph.d. thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bangura, M. Aerodynamics and Control of Quadrotors. PhD thesis, College of Engineering and Computer Science, The Australian National University, 2017.

- Bouabdallah, S. Design and control of quadrotors with application to autonomous flying. PhD thesis, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Luasanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2007.

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems, 3 ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Lynch, A. Nonlinear Motion Control of a Multirotor Slung Load System: Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC); 2024; pp. 2851–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawati, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, E.; Lynch, A.F. Nonlinear Control of a Multi-Drone Slung Load System. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC); 2025; pp. 1989–1996. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4 | 0.5 | ||

| 0.5 | 7 | ||

| 1 | 3 | ||

| 0.001 | 5 | ||

| 1 |

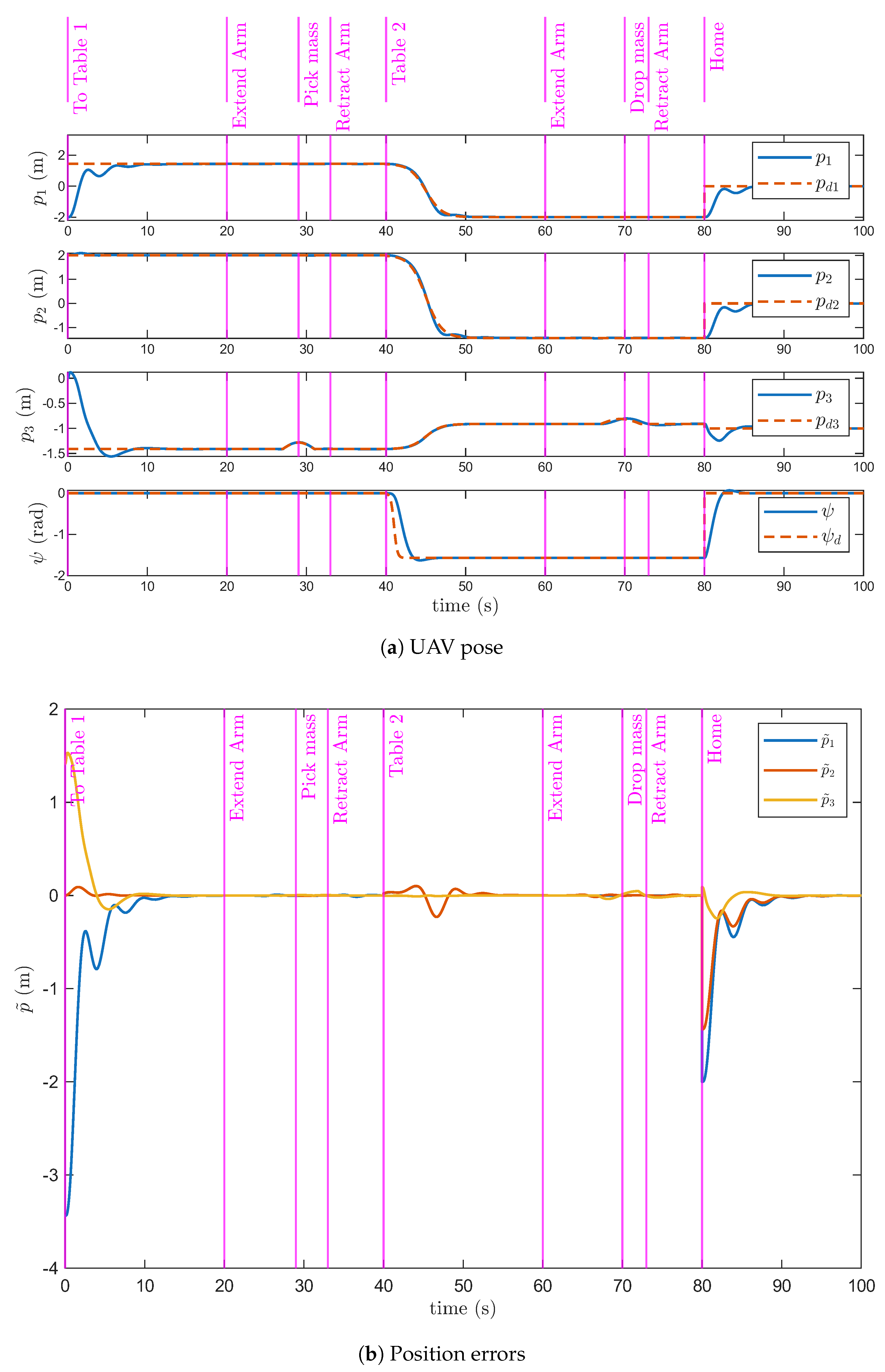

| Time t | Desired Position | Desired Yaw | Arm configuration | Cube Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Home | Table 1 | ||

| 20 | Extending | Table 1 | ||

| 27 | Extended | Table 1 | ||

| 29 | Extended | UAM | ||

| 32 | Retracting | UAM | ||

| 40 | Home | UAM | ||

| 60 | Extending | UAM | ||

| 67 | Extending | UAM | ||

| 70 | Extended | Table 2 | ||

| 73 | Retracting | Table 2 | ||

| 80 | 0 | Home | Table 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).