Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

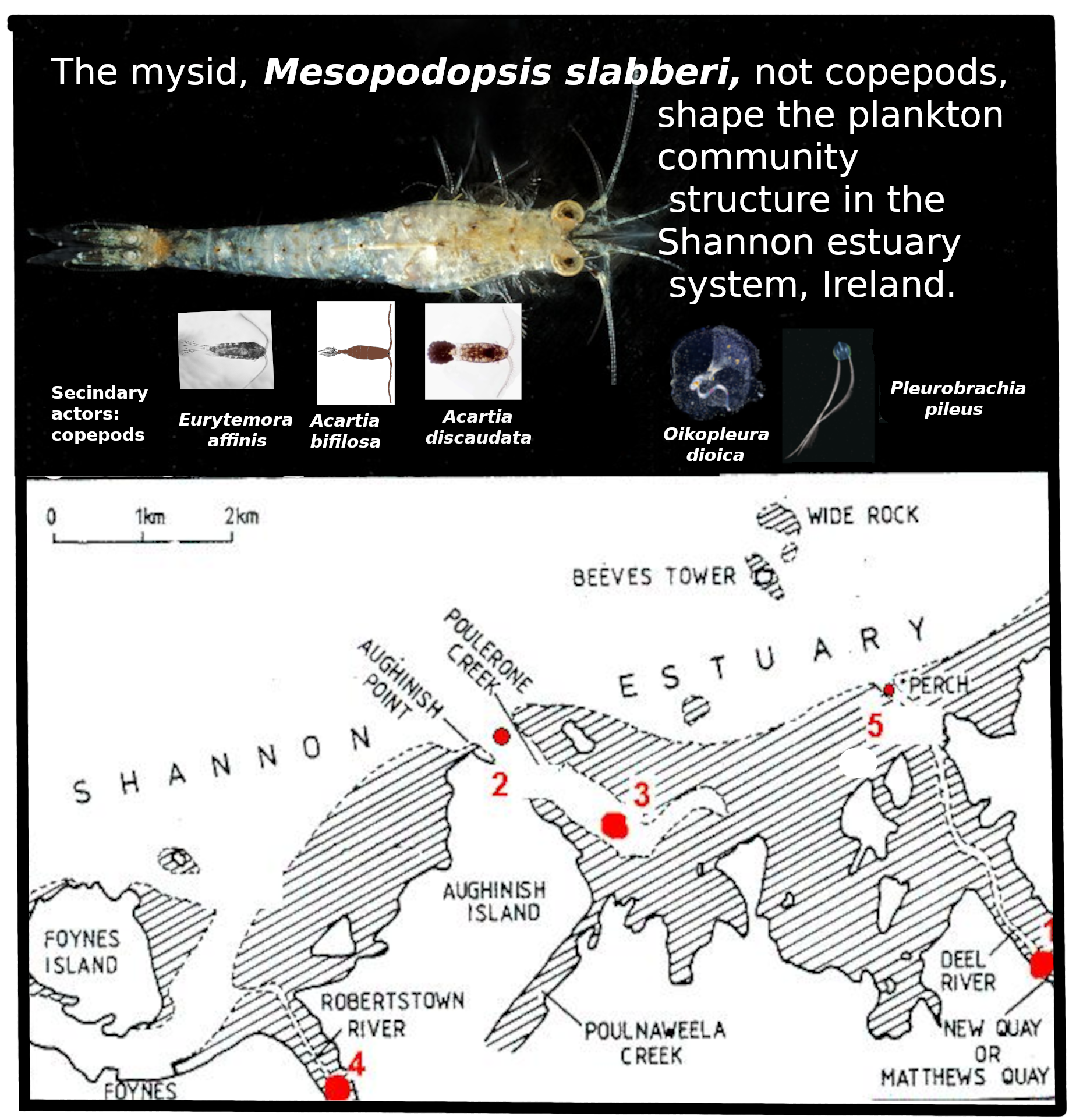

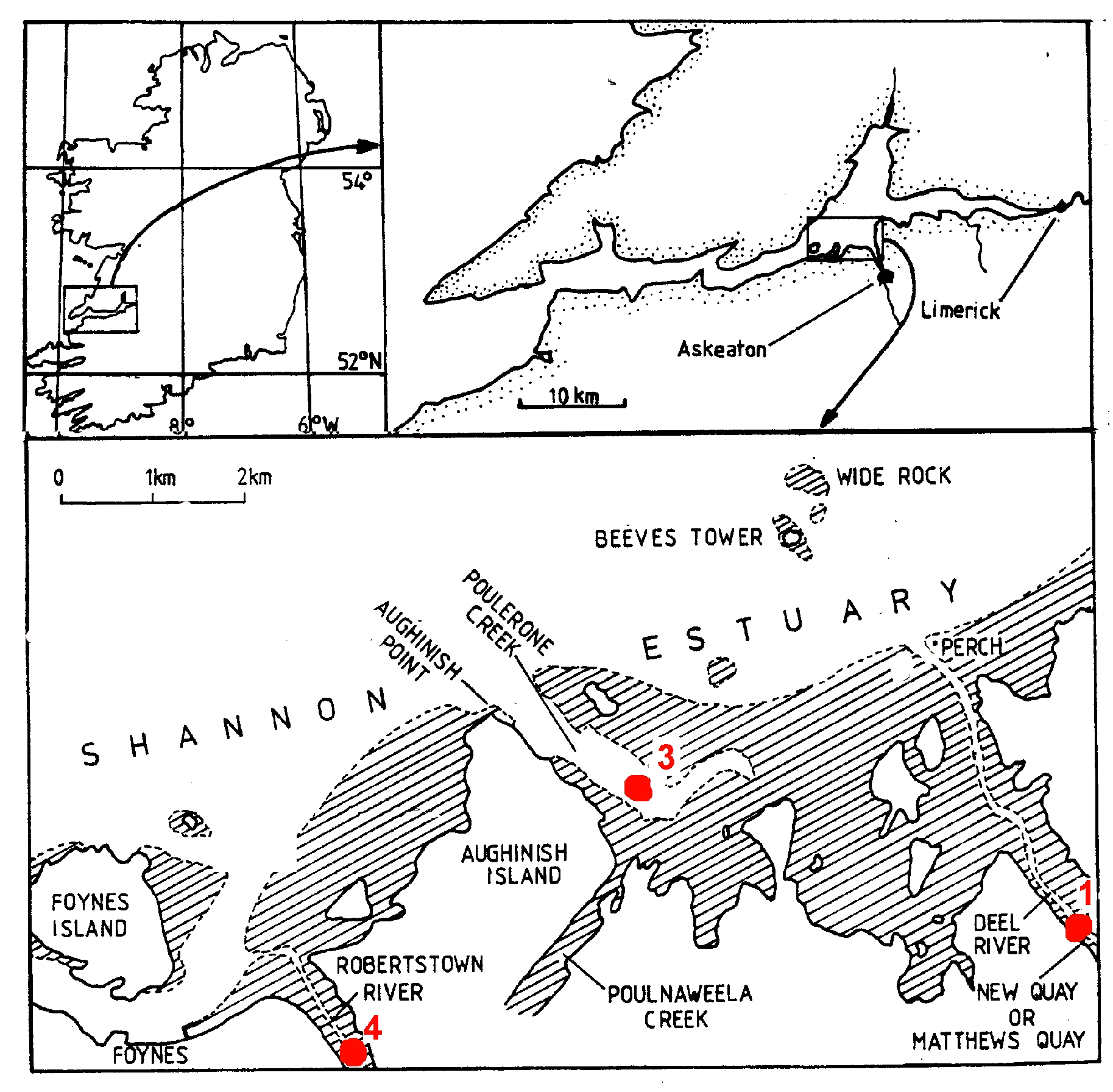

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

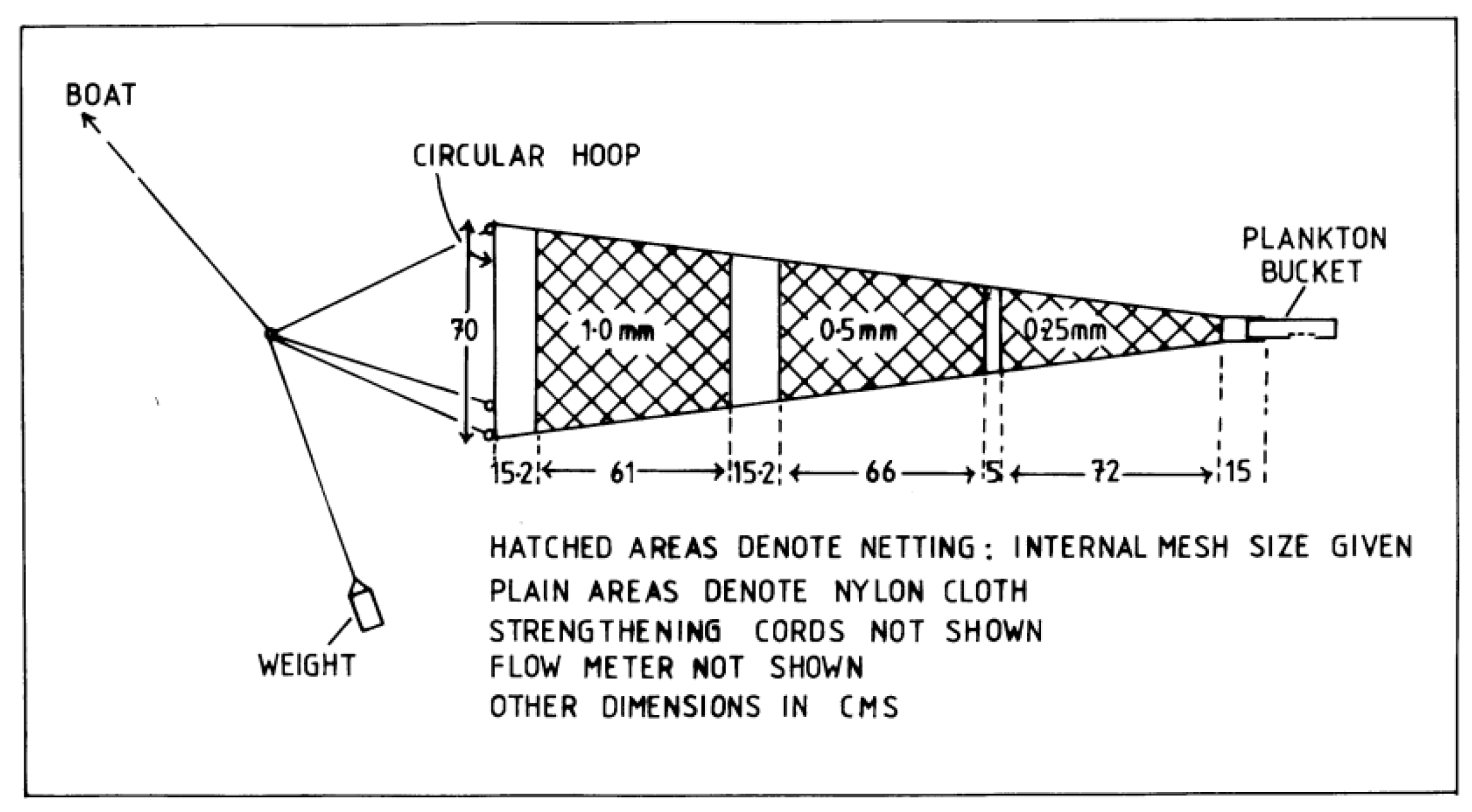

3.1. Sampling, Identification and Estimation of Abundance

3.2. Statistical Analyses

3.2.3. Diversity

3.2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.3. Choice of Environmental Variables

3.4. Calculations of Trophic Impact

3.4.1. General Consderations

3.4.2. Predatory Clearance Rate by Pleurobrachia pileus

3.4.3. Clearance Rate by Eurytemora affinis

3.4.4. Clearance Rate by Acartia spp.

3.4.5. Clearance Rates by Mysids

3.4.6. Clearance Rates by Oikopleura dioica

4. Results

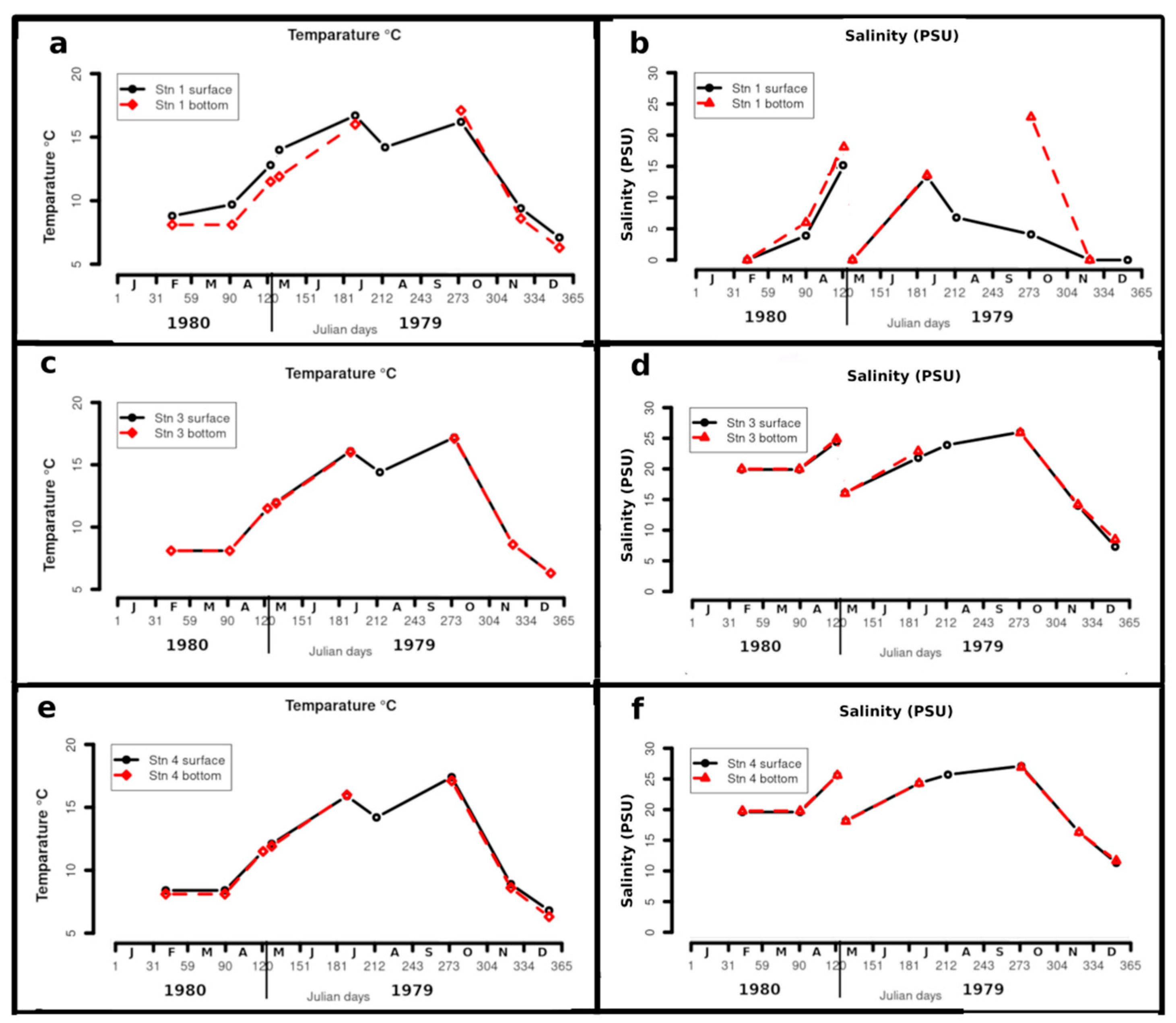

4.1. Temperature and Salinity

4.2. Etritus Volume Fraction

4.3. Total Netplankton

4.4. Plankton Diversity

4.5. Principal Component Analysis and Seasonal Distribution

| Abbreviation | Variable | Transform | Abbreviation | Variable | Transform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abif | Acartia bifilosa | Log(n+1) | Acla | Acartia clausi | Log(n+1) |

| Adis | Acartia discaudata | Log(n+1) | Amph | Amphipods | Log(n+1) |

| Ang | Anguilla anguilla – elvers | Log(n+1) | Aur | Aurelia aurita | Log(n+1) |

| Cal | Calanus helgolandicus and C. sp. | Log(n+1) | Cham | Centropages hamatus | Log(n+1) |

| Cmae | Carcinus maenas larvae | Log(n+1) | Cran | Crangon crangon | Log(n+1) |

| Cycl | Freshwater cyclopoid copepods | Log(n+1) | Detr | Detritus volume | LoLog(volume) |

| Eaff | Eurytemora affinis | Log(n+1) | Evel | Eurytemora velox | Log(n+1) |

| Gna | Gnathiid isopods | Log(n+1) | Gob | Gobiid larvae | Log(n+1) |

| Harp | Harpactacoid copepods | Log(n+1) | Hulv | Hydrobia ulvae adults | Log(n+1) |

| Iche | Idotea chelipes | Log(n+1) | Lam | Lamellibranch larvae | Log(n+1) |

| Litt | Littorina littorea egg capsules (2-3 eggs) | Log(n+1) | Micr | Biovolume of nano-microplankton 10-200µm (from Jenkinson, 1990)) | Log(volume) |

| Msla | Mesopodopsis slabberi | Log(n+1) | Netp | Total netplankton doncentration | Log(n+1) |

| Nint | Neomysis integer | Log(n+1) | Odio | Oikopleura dioica | Log(n+1) |

| Pfle | Platychthys flesus | Log(n+1) | Ple | Pleurobrachia pileu | Log(n+1) |

| Poly | sPolychaete larvae | Log(n+1) | S | Salinity (mean of surface and bottom) | No transform |

| Scop | Small copepods, Paracalanus parvus and Pseudocalanus elongatus | Log(n+1) | Secc | Secchi disc depth (m) - Water clarity | No transform |

| Spr | Spring equinox component (Autumn component is the negative of this) | No transform | ros | Sygnathus rostratus | Log(n+1) |

| Sum | Summer solstice component (Winter component is the negative of this) | No transform | T | Water temperature (mean of surface and bottom) | No transform |

4.6. Dominant and Noteworthy Zooplankton

4.6.1. Coelenterates

4.6.2. Ctenophores

4.6.3. Polychaetes ( 6h)

4.6.4. Major Copepods (Sex Ratios Are Expressed as M:F. Cited Ratios Expressed as F:M Have Been Converted)

4.6.5. Other Copepods

4.6.6. Cirripedes

4.6.7. Mysids

4.6.8. Isopods

4.6.9. Amphipods

4.6.10. Decapods

4.6.11. Molluscs

4.6.12. Tunicates

4.6.13. Fishes

4.7. Clearance Rates and Ingestion Rates

4.7.1. Predatory Clearance Rates by Pleurobrachia pileus

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Jul | 0.00 | 0.30 | 3.02 |

| Aug | 0.00 | 0.05 | 3.54 |

| Oct | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| Nov | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Dec | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Feb | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Apr | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| May | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| MEAN | 0.00 | 0.078 | 0.75 |

4.7.2. Eurytemora affinis (syn.: Eurytemora hirundoides)

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May | 0 | 0.03 | 0.84 |

| Jul | P | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Aug | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oct | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Nov | 0 | 0.29 | 2.9 |

| Dec | 0 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Feb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.18 |

| May | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.07 |

| MEAN | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.45 |

4.7.3. Clearance Rates by Acartia spp.

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

| Jul | 0 | 1 | 5.5 |

| Aug | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 0.17 | 0 |

| Nov | 0 | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| Dec | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.02 |

| MEAN | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.67 |

4.7.4. Clearance Rates by All Copepods

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May | 0 | 0.03 | 0.92 |

| Jul | P | 1.03 | 5.57 |

| Aug | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Oct | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Nov | 0 | 0.91 | 3.28 |

| Dec | 0 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Feb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.18 |

| May | 0.37 | 0.79 | 0.09 |

| MEAN | 0.08 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

4.7.5. Clearance Rates by Mysids

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May total | 0.00 | 0.95 | 15.13 |

| Adults | 0.00 | 0.95 | 14.42 |

| Juveniles | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.71 |

| Jul total | P | 111.84 | 148.25 |

| Adults | P | 7.63 | 66.34 |

| Juveniles | P | 104.22 | 81.90 |

| Aug total | 19.82 | 10.48 | 0.07 |

| Adults | 0.98 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 18.84 | 10.34 | 0.07 |

| Oct total | 491.29 | 140.87 | 26.36 |

| Adults | 404.57 | 0.74 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 86.72 | 140.12 | 26.36 |

| Nov | 0.00 | 50.93 | 169.38 |

| Adults | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 0.00 | 50.93 | 169.38 |

| Dec | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1.07 |

| Adults | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1.07 |

| Feb | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.59 |

| Adults | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.59 |

| Apr | 26.26 | 2.56 | 6.34 |

| Adults | 8.36 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Juveniles | 17.90 | 2.35 | 6.34 |

| May | 82.50 | 12.84 | 0.31 |

| Adults | 80.41 | 11.23 | 0.18 |

| Juveniles | 2.09 | 1.60 | 0.13 |

| MEAN | 77.48 | 36.73 | 40.83 |

| Adults | 61.79 | 2.32 | 8.99 |

| Juveniles | 15.69 | 34.41 | 31.84 |

| P - Present but not quantified. | |||

4.7.6. Clearance Rates by Oikopleura dioica

| Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Cruise | |||

| May | 0 | 0 | 0.12 |

| Jul | P | 4.3 | 22 |

| Aug | 0.11 | 0.55 | 1.1 |

| Oct | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 0 | 0.21 | 0.80 |

| MEAN | 0.01 | 0.56 | 2.7 |

4.7.7. Total Filter-Feedingclearance Rates by the Netplankton

4.8. Diversity

5. Discussion

5.1. Our Three-Mesh Net Was Important to Capture the Larger Amesoplankton

5.2. Trophic Structuring by the Mesoozooplankton

5.3.1. General Considerations

5.3.2. The Major Copepods, Eurytemora and Acartia

5.3.3. Cladocerans

5.3.4. Mesopodopsis slabberi

5.3.5. Oikopleura Dioica

5.3.6. Pleurobrachia Pileus

5.3.7. The Absence of Cladocerans

5.3.8. Hydrobia Ulvae

5.4. Diversity

5.5. Mesopodopsis Controls the Mesoplankton Food Web

6. Conclusions

-

The mesoplankton in the Shannon estuary system near Aughinish Island, and two tributary estuaries, the Robertstown and the Deel, was investigated in 1979-80 in nine cruises over a year.This archive on the mesoplankton is now available for comparison across spatial and temporal scales.

- The year-round mesoplankton distribution in the Robertstown estuary (station 4) was similar to that at the station sampled in the Shannon estuary (station 3), but that in the Deel estuary (station 1) was quite distinct, corresponding to very different annual vaiaions in salinity and microoplankton.

- The PCA, incorporating our two innovations of leaving controlling and controlled variables undefined, and the incorporation of the celestial variables of Spring-Autumn (Spr)and Summer-Winter (Sum), gave distributions of variables and stations in the first three dimensions, D1, D2 and D3, of hyperspace compatible with human intuition. On the D1-D3 plane, the Deel evolved over the year separately from the Shannon and the Robertstown , while in the D1-D3 plane Spr and Sum distributed approximately at right angles to each other, roughly circularly in this plane, along with the seasons of the year.

- The copepod fauna overall was dominated by Eurytemora affinis, Acartia bifilosa and A. discaudata, as well as the somewhat less abundant A. clausi. This fauna is typical of many temperate estuaries, except for the notable absence of two components, cladocerans and the copepod, Acartia tonsa. A. tonsa an invasive copepod, had already widely colonized European estuaries at the time of this survey. Subsequent colonization of the Shannon estuary system is therefore to be expected.

- Trophic impact ‘clearance rate) by the major groups of mesoplankton are estimated as follows. In the Deel (Station 1), the Shannon (Station 3) and the Robertstown (Station 4), respectively: Mesopodopsis slabberi (herbivorous and detritivorous part), 77.48, 36.73, 40.83 L.m-3.d-1 (mean 51.68); all copepods (herbivorous and detritivorous part), 0.072, 0.30, 0,91 L.m-3.d-1 (mean 0.43); Oikopleura dioica (herbivorous on pico/nanoplankton), 0.014, 0.56, 2.7 L.m-3.d-1(mean 1.09). Thus gives a year-round mean herbivorous/detritvorous mean of 53,20 L.m-3.d-1, of which Mesopodopsis, copepods and Oikopleura v contributed 97.14%, 0.81% and 2.04%, respectively. Additionally, Peurobrachia contributed a year-round mean carnivorous trophic impact in the Deel, Shnnon and Robertstown estuaries of 0.00, 0.08 and 0.75 L.m-3.d-1,(mean 0.28 L.m-3.d-1), while Mesopodopsis and copepods added an unknown amount of extra carnivorous impact. Combined carnivorous impact by Mesopodopsis and Pleurobrachia may have been keeping the larval and adult copepod populations low.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Lotze, H.K. , Lenihan, H. , Bourque, B., Bradbury, R., Cooke, R., Kay, M., Kidwell, S., Kirby, M., Peterson, C., Jackson, J. Depletion, Degradation, and Recovery Potential of Estuaries and Coastal Seas Science. 2006, 312, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, D. , Wilson, J.G., Harris, C., Tomlinson, D. The application of two simple indices to Irish estuary pollution studies. In: Estuarine Management and Quality Assessment, Wilson J., Halcrow W. (Eds), Plenum Press, London, 1985, pp. 147–161.

- Wilson, J. , Brennan, B. Spatial and temporal variation in sediments and their nutrient concentrations in the unpolluted Shannon estuary, Ireland. Archiv für Hydrobiologie.. 1993, 75, 451–486. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. , Brennan, B., Brennan, M. Horizontal and vertical gradients in sediment nutrients on mudflats in the Shannon estuary, Ireland. Netherlands Journal of Aquatic Ecology. 1993, 27, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. , Brennan, M. Nutrient interchange between the sediment and the overlying water on the intertidal mudflats of the Shannon estuary Archiv für Hydrobiologie. 1993, 75, 423–450. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, T.K. , Frankiewicz, P. , Cullen, P., Blaszkowski, M., Oâ'Connor, W., Doherty, D. Long-term effects of hydropower installations and associated river regulation on River Shannon eel populations: mitigation and management Hydrobiologia. 2008, 609, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. and Conservation through Education (2025) All gates closed. The life and death of the Atlantic salmon. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PcgFo0odp2w Consulted 2 Jan, 2025.

- Byrne, P. Seasonal Composition of Meroplankton in the Dunkellin Estuary, Galway Bay. Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 1995, 95B, 35–48. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20504491.

- Ó Céidigh, P. The marine Decapoda of Counties Galway and Clare. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section B. 1961, 62, 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Fives, J.M. Investigations of the plankton of the west coast of Ireland. II. Planktonic Copepoda raken off County Galway and adjacent areas in plankton surveys during the years 1958 to 1963. Proceeedings of the Royal Irish Academy, B. 1968, 67, 233–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fives, J.M. Investigations of the Plankton of the West Coast of Ireland: IV. Larval and Post-Larval Stages of Fishes Taken from the Plankton of the West Coast in Surveys during the Years 1958-1966 Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section B: Biological, Geological, and Chemical Science. 1970, 70, 15–93. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20494950.

- Fives, J.M. Investigations of the Plankton of the West Coast of Ireland: V. Chaetognatha Recorded from the Inshore Plankton off Co. Galway Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section B: Biological, Geological, and Chemical Science. 1971, 71, 119–138. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20518893.

- O'Brien, F.I. The relationship between temperatur, salinity and Chaetognatha of the Galway Bay area of the west coast of Ireland. Proceedings of the Ryal Iish Academy, B. 1977, 77, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R.J. , Céidigh, P. Ó., Wilkinson, A. Investigations of the Plankton of the West Coast of Ireland: VI. Pelagic Cnidaria of the Galway Bay Area 1956-72, with a Revision of Previous Records for These Species in Irish Inshore Waters Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section B: Biological, Geological, and Chemical Science. 1973, 73, 383–403. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20518927.

- Hensey, M. (1980) Zooplankton and oceanographic conditions in the Shannon Estuary, Ireland. M.Sc. Dissertation, University College Galway, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland.

- Mackas, D.L. , Beaugrand, G. Comparisons of zooplankton time series J Mar Syst. 2010, 79, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, R. , Wyatt, T. , O'Brien, D. Determoinistic signals in fish catches, wine harvests and sea-level, and further experiments Int J Climatol. 1993, 13, 665–687. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu, S. The Road to a New Bauxite – Mine and Refinery Optimisation. In: TRAVAUX 48, Proceedings of the 37 th Internati Conal ICSOBA Conference andXXV Conference «Aluminium of Siberia», Krasnoyarsk, Russia, September 2019, (Eds), , 2019, pp. 137–139. https://icsoba.org/proceedings/37th-conference-and-exibition-icsoba-2019/?doc=17.

- O'Sullivan, G. The intertidal fauna of Aughinish Island, Shannon, Co. Limerick Irish Naturalists' Journal. 1983, 21, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan, G. Seasonal changes in the intertidal fish and crustacean populations of Aughinish Island and the Shannon Estuary. Irish Fishery Investigations, Series B 1984, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, I.R. The microplankton biomass and diversity of the upper Shannon estuary (Ireland) and two tributary estuaries. British Phycological Journal 1985, 20, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, I.R. Estuarine plankton of Co Limerick. I. A recurrent bloom summer bloom of the dinoflagellate Glenodinium foliaceum Stein confined to the Deel estuary, with data on microplankton biomass Irish Naturalists' Journal. 1990, 23, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- The Shannon Airport Group (2024) Traffic Figures. https://www.snnairportgroup.ie/2025/shannon-airport-passenger-numbers-climb-7-to-over-104m-in-first-half-of-2025/. Consulted 08 August 2025.

- Rusal (2024) Aughinish Alumina. https://rusal.ru/en/about/geography/aughinish-alumina/.,.

- Wonham, M. , Carlton, J. Trends in marine biological invasions at local and regional scales: the Northeast Pacific Ocean as a model system Biological Invasions. 2005, 7, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Oceanography (1979) Data Report No. 4, 1977-1978, Department of Oceanography, University College Galway, Ireland. ,.

- Department of Oceanography (1981) Data Report No. 5, 1979-1980, Department of Oceanography, University College Galway, Ireland.

- McMahon, T., Raine, R., Fast, T., Kies, L., Patching, J. Plankton biomass, light attenuation and md mixing in the Shannon estuary, Ireland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1992, 72, 709–720. [CrossRef]

- Grandremy, N. Grandremy, N., Bourriau, P., Daché, E., Danielou, M.-M., Doray, M., Dupuy, C., Forest, B., Jalabert, L., Huret, M., Le Mestre, S., Nowaczyk, A., Petitgas, P., Pineau, P., Rouxel, J., Tardivel, M., Romagnan, J.-B. Metazoan zooplankton in the Bay of Biscay: a 16-year record of individual sizes and abundances obtained using the ZooScan and ZooCAM imaging systems. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2024, 16, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.E., Counts, R.C., Clutter, R.I. Changes in Filtering Efficiency of Plankton Nets Due to Clogging Under Tow. {ICES} Journal of Marine Science. 1968, 32, 232–248. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. , Weaver, W., The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, USA, 1963.

- Abdullah Al, M., Gao, Y., Xu, G., Wang, Z., Xu, H., Warren, A. Variations in the community structure of biofilm-dwelling protozoa at different depths in coastal waters of the Yellow Sea, northern China. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 2019, 99, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M., Ashok Prabu, V., Rahman, M.M., Jenkinson, I.R. Community structure of microzooplanktonin a tropical estuary (Uppanar) and amangrove (Pichavaram) from the south-east coast of India. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India. 2022, 64, 13–28. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2024) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.,.

- Oksanen, J. , Simpson, G. L., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., Wagner, H., Barbour, M., Bedward, M., Bolker, B., Borcard, D., Carvalho, G., Chirico, M., De Caceres, M., Durand, S., Evangelista, H. B. A., FitzJohn, R., Friendly, M., Furneaux, B., Hannigan, G., Hill, M. O., Lahti, L., McGlinn, D., Ouellette, M.-H., Ribeiro Cunha, E., Smith, T., Stier, A., Ter Braak, C. J. and Weedon, J. (2022) vegan: Community Ecology. Package. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313502495_Vegan_Community_Ecology_Package.,.

- Jolliffe, I.T., Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2016, 374, 20150202. [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. and Mundt, F. (2020) factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra.,.

- Longobardi, L. , Dubroca, L., Margiotta, F., Sarno, D., Zingone, A. Photoperiod-driven rhythms reveal multi-decadal stability of phytoplankton communities in a highly fluctuating coastal environment Sci Rep. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Häfker, N.S. Häfker, N.S., Andreatta, G., Manzotti, A., Falciatore, A., Raible, F., Tessmar-Raible, K. Rhythms and Clocks in Marine Organisms. Annual Review of Marine Science. 2023, 15, 509–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Båmstedt, U. Trophodynamics of Pleurobrachia pileus (Ctenophora, Cydippida) and ctenophore summer occurrence off the Norwegian north-west coast. Sarsia. 1998, 83, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A. , The Open Sea: The World of Plankton. Collins, London, 1956.

- Purcell, J. , Sturdevant, M., Galt, C. A review of appendicularians as prey of invertebrate and fish predators. In: Response of Marine Ecosystems to Global Change: Ecological Ipact of Appendicularians, Gorsky G., Youngbluth M., Deibel D. (Eds), Editions Scientifiques, Paris, 2005, pp. 259–435.

- Yip, S.Y. A preliminary study on the planktonic ctenophora of the west coast of Ireland with special reference to Pleurobrachia pileus from Galway Bay. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Acedemy, Section B 1981, 81, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Zooplankton of the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary. Mar Pollut Bull. 1984, 15, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.E. Global phylogeography of a cryptic copepod species complex and reproductive isolation between genetically proximate "populations". Evolution 2000, 54, 2014–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackx, M. Tackx, M., Pauw, N. d., Mieghem, R. v., Azémar, F., Hannouti, A., Damme, S., Fiers, F., Daro, N., Meire, P. Zooplankton in the Schelde estuary, Belgium and The Netherlands. Spatial and temporal patterns. J Plankton Res. 2004, 26, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, V. , Sautour, B., Galois, R., Chardy, P. The paradox high zooplankton biomass - low vegetal particulate organic matter in high turbidity zones: What way for energy transfer? J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2006, 333, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulet, S.A. Comparison between five co-existing species of marine copepods feeding on naturally occurring particulate matter. Limnol Oceanogr, 1978; 23, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M. Mullin, M., Sloan, P., Eppley, R. Relationship between carbon content, cell volume, and area in phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 1966, 11, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, J. Aspects de l’étude écologique du plancton de l’estuaire de la Gironde. Oceanis 1981, 6, 353–577. [Google Scholar]

- Heinle, D. , Flemer, D. Carbon requirements of a population of the estuarine copepod, Eurytemora affinis Mar Biol. 1975, 31, 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, S. , Heinle, D. , Huff, R. Grazing by adult estuarine copepods of the Chesapeake Bay Mar Biol. 1977, 42, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, N.R. Feeding of the copepod Acartia tonsa on the diatom Nitzschia closterium and brown alga (Fucus vesiculosus) detritus. Mar Biol. 1977, 42, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiørboe, T., Møhlenberg, F., Hamburger, K. Bioenergetics of the planktonic copepod Acartia tonsa: relation between feeding, egg production, and composition of specific dynamic action. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1985, 26, 85–97. [CrossRef]

- Webb, P., Perissinotto, R., Wooldridge, T. Feeding of Mesopodopsis slabberi (Crustacea, Mysidaceae) on naturally occurring phytoplankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1987, 38, 115–123. [CrossRef]

- David, V. (2006) Dynamique spatio-temporelle du zooplancton dans l’estuaire de la Gironde et implications.au sein du réseau trophique planctonique. Doctoral Thesis, Université de Bordeaux I, Boreaux, France.

- King, K. R. The population biology of the larvacean Oikopleura dioica in enclosed water columns. In: Marine Mesocosms, Grice O. D., Reeve M. R. (Eds), Springer, New York, USA, 1982, pp. 341–352.

- Alldredge, A. The impact of appendicularian grazing on natural food concentrations in situ. Limnol Oceanogr. 1981, 26, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuňa, J. , Kiefer, M. Functional response of the appendicularian Oikopleura dioica L\imnology and Oceanography. 2000, 45, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vaupel-Klein, J. , Weber, R. Distribution of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda: Calanoida) in relation to salinity: field and laboratory observations. Neth J Sea Res. 1975, 9, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devreker, D., Souissi, S., Molinero, J.C., Nkubito, F. Trade-offs of the copepod Eurytemora affinis in mega-tidal estuaries. Insights from high frequency sampling in the Seine Estuary. J Plankton Res. 2008, 30, 1329–1342. [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsen, W. , MacKenzie, K., Sagerup, K., Remen, M., Bloch-Hansen, K., Dagbjartarson Imsland, A.K. Caligus elongatus and other sea lice of the genus Caligus as parasites of farmed salmonids: A review Aquaculture. 2020, 522, 735160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, W. , Tattersall, O., The British Mysidacea. The Ray Society, London, 1951.

- Naylor, E. , British Marine Isopods. Linnean Society and Academic Press, London, 1972.

- Graham, A. , British Prosobranch and other Operculate Gastropod Molluscs. Academic Press, London, 1971.

- Gibson, R. , Hextall, B., Rogers, A., Photographic Guide to the Sea and Shore Life of Britain and North-west Europe. Oxford University Press, New York, 2001.

- Little, C. , Nix, W. The burrowing and floating behaviour of the gastropod Hydrobia ulvae Estuarine Coastal and Marine. Science. 1976, 4, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutter, R. , Anraku, M. Avoidance of samplers. In: Zooplankton Sampling, (Eds), UNESCO, Paris, 1968, pp. 57–76.

- Skjoldal, H.R. Aarflot, J.M., Knutsen, T., Wiebe, P.H. Comparison of WP-2 and MOCNESS plankton samplers for measuring zooplankton biomass in the Barents Sea ecosystem. J Plankton Res. 2024, 46, 654–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, P.H. , Harris, R, Gislason, A., Margonski, P., Skjoldal, H.R., Benfield, M., Hay, S., O’Brien, T., Valdés, L. The ICES Working Group on Zooplankton Ecology: Accomplishments of the first 25 years. Prog Oceanogr. 2015, 141, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, L.F. , Canon, J.M., Tiselius, P. Bioenergetics and growth in the ctenophore Pleurobrachia pileus. Hydrobiologia. 2010, 645, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitsch, A. , Köpcke, B., Bernát, N. Long-term investigation of the distribution of Eurytemora affinis (Calanoida; Copepoda) in the Elbe Estuary. Limnologica 2000, 30, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, J.-B. , Winkler, G. Coexistence, distribution patterns and habitat utilization of the sibling species complex Eurytemora affinis in the St Lawrence estuarine transition zone. J Plankton Res. 2014, 26, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troedson, C. , Frischer, M.E., Nejstgaard, J.C., Thompson, E.M. Molecular quantification of differential ingestion and particle trapping rates by the appendicularian Oikopleura dioica as a function of prey size and shape. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007, 52, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A. , Beardall, J. Evolution of Phytoplankton in Relation to Their Physiological Traits. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2022, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanpour-Gargari, A. , Wellershaus, S. Very low salinity stretches in estuaries – the main habitat of Eurytemora affinis, a plankton copepod. Meeresforschung. 1997, 31, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, J. , Courties, C., Poli, J. Dynamique du copépode Eurytemora hirundoidesdans l’estuaire de la Gironde : effet de la température Oceanologica Acta, Spec Vol.. 1983:57-61.

- Collins, N. , Williams, R. Zooplankton of the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary. The distribution of four copepods in relation to salinity. Mar Biol. 1981, 64, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C. The plankton in the upper reaches of the Bristol Channel. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingsom. 1939, 23, 397–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, M. Assimilation of particulate organic carbon by estuarine and coastal copepods. Mar Biol. 1978, 49, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinle, D.R. Population dynamics of exploited cultures of calanoid copepods. Helgoländer Wissenshaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen 1970, 20, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, S.K. Growth characteristics of the copepods Eurytemora affinis and Eurytemora herdmanni in laboratory culture. Helgoländer Wissenschalftliche Meeresuntersuchungen 1970, 20, 373–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, S. , Brownlee, D., Heinle, D., Kling, H., Colwell, R. Ciliates as a food source for marine plankton copepods. Microb Ecol. 1977, 4, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinle, D. , Harris, R. , Ustach, J., Flemer, D. Detritus as food for estuarine copepods Mar Biol. 1977, 40, 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, J. , Castel, J. Cycle biologique en laboratoire d’un copépode planctonique de l’estuaire de la Gironde: Eurytemora hirundoides (Nordquist, 1888) Vie et Milieu. 1983, 33, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford-Greve, J. M. Copepoda: Calanoida: Acartiidae: Acartia, Paracartia, Pteriacartia. In: ICES Identification Leaflets for Plankton No. 181, Lindley J. (Eds), International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999, pp. 1–19.

- Marques, S.C. , Azeiteiro, U. M., Marques, J.C., Neto, J.M., Pardal, M.A. Zooplankton and ichthyoplankton communities in a temperate estuary: spatial and temporal patterns J. Plankton Res. 2006, 28, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remerie, T. , Bourgois, T. , Peelaers, D., Vierstraete, A., Vanfleteren, J., Vanreusel, A. Phylogeographic patterns of the mysid Mesopodopsis slabberi (Crustacea, Mysida) in Western Europe: evidence for high molecular diversity and cryptic speciation. Mar Biol. 2006, 149, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fèvre-Lehoëroff, G. Distribution et variations saisonnières du plancton en ‘rivière de Morlaix. Comptes-rendus hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris 1972, 275, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Gieskes, W. Ecology of the cladocera of the North Atlantic and the North Sea, 1960–1967. Neth J Sea Res. 1971, 5, 342–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helenius, L.K. , Leskinen, E. , Lehtonen, H., Nurminen, L. Spatial patterns of littoral zooplankton assemblages along a salinity gradient in a brackish sea: A functional diversity perspective Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2017, 198, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, S. , Queiroga, H. Use of artificial collectors shows semilunar rhythm of planktonic dispersal in juvenile Hydrobia ulvae (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia) Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 2004, 84, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fèvre-Lehoërff, G. Variabilité de l'indice de diversité spécifique de copépodes dans l'estuaire à marée (Baie de Morlaix) : sa signification écologique. Annales de l'Institut Océanographique, Monaco, Nouvelle Série. 1974, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara, S. , Uyé, S. , Onbé, T. Calanoid copepod eggs in sea-bottom muds. II. Seasonal cycles of abundance in the populations of several species of copepods and their eggs in the Inland Sea of Japan Mar Biol. 1975, 31, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).