Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

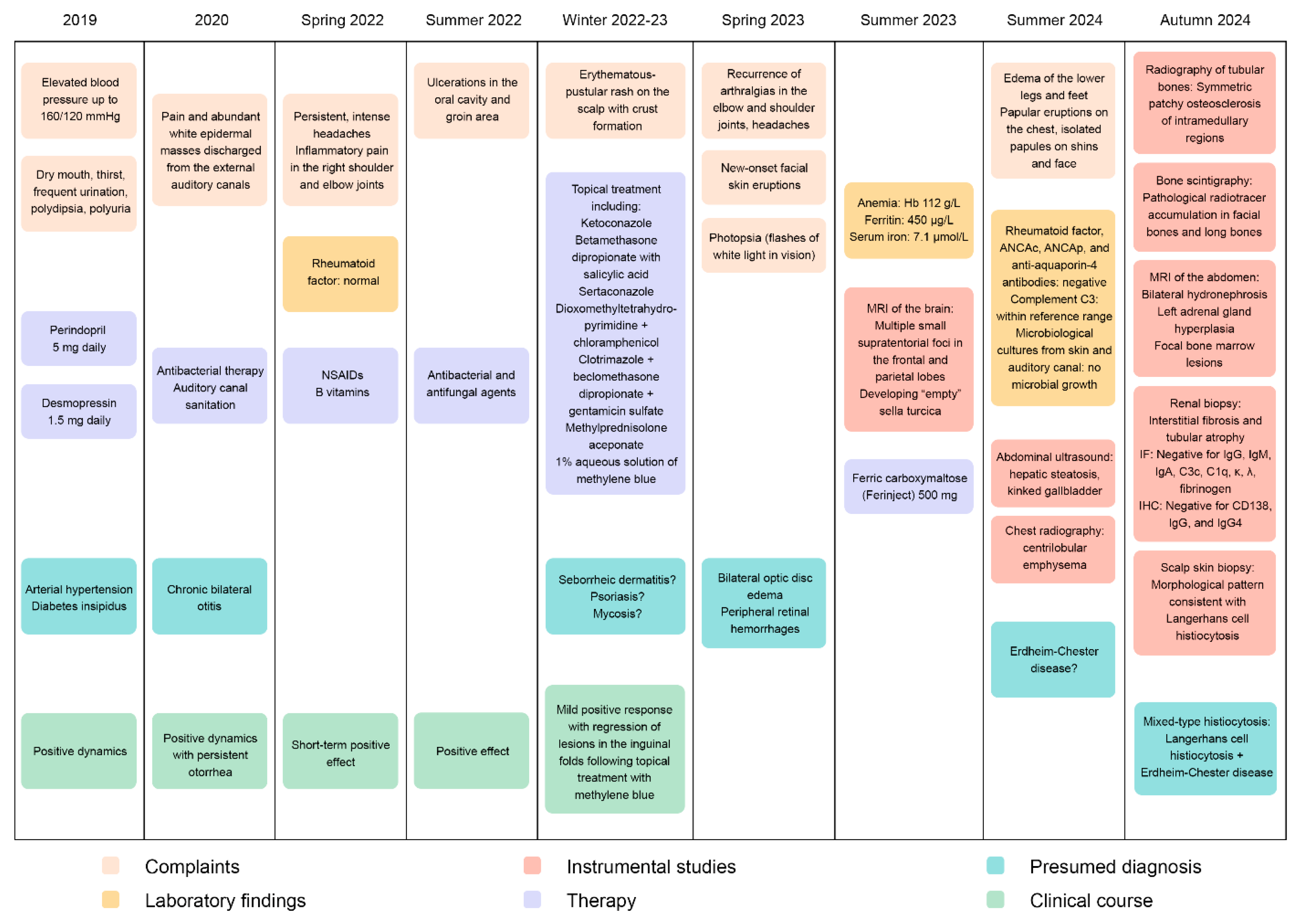

Case Report

Materials and methods

Genomic DNA Extraction and Quality Control

Library Preparation, Exome Сapture and Sequencing

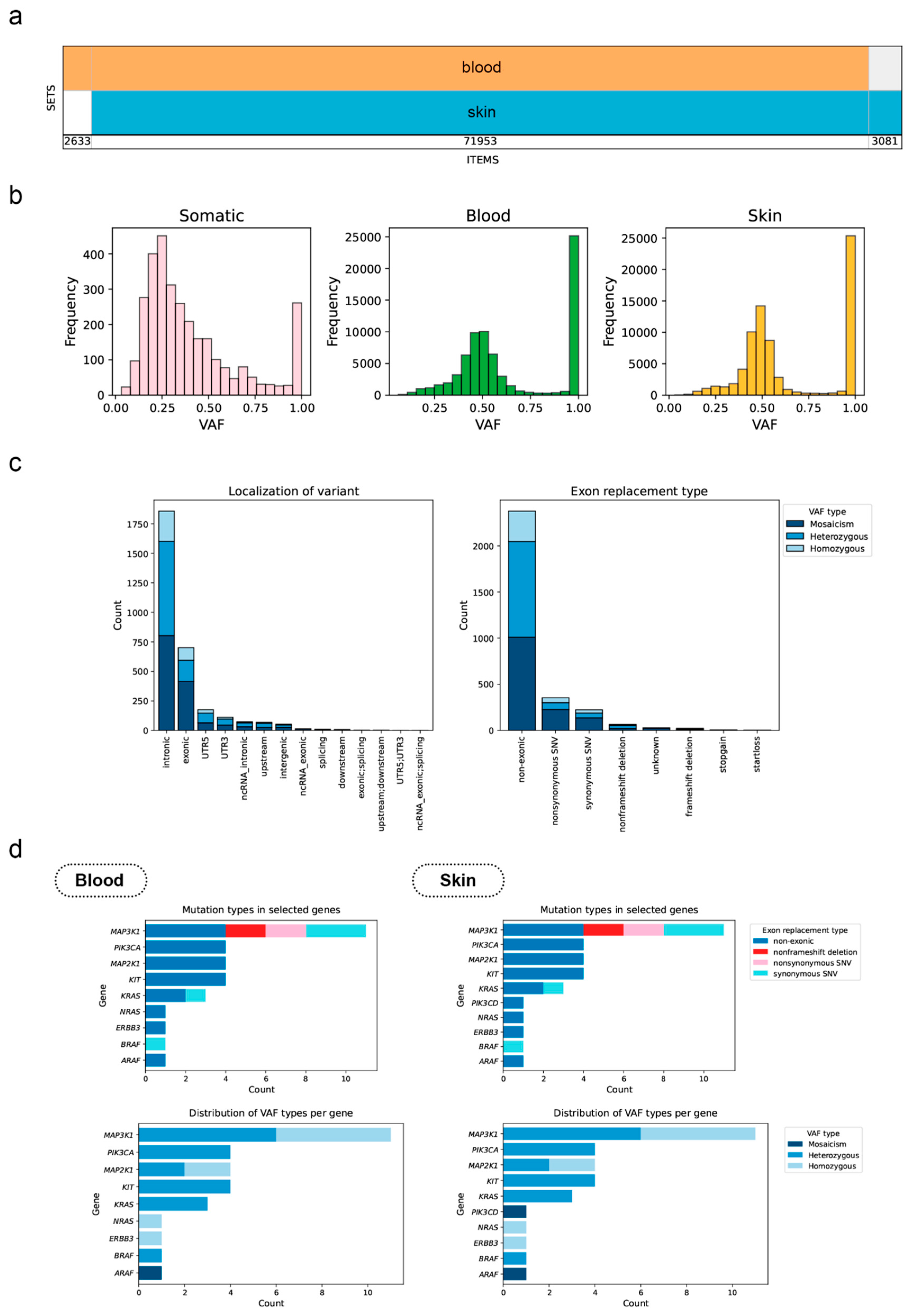

Bioinformatic Processing and Variant Analysis

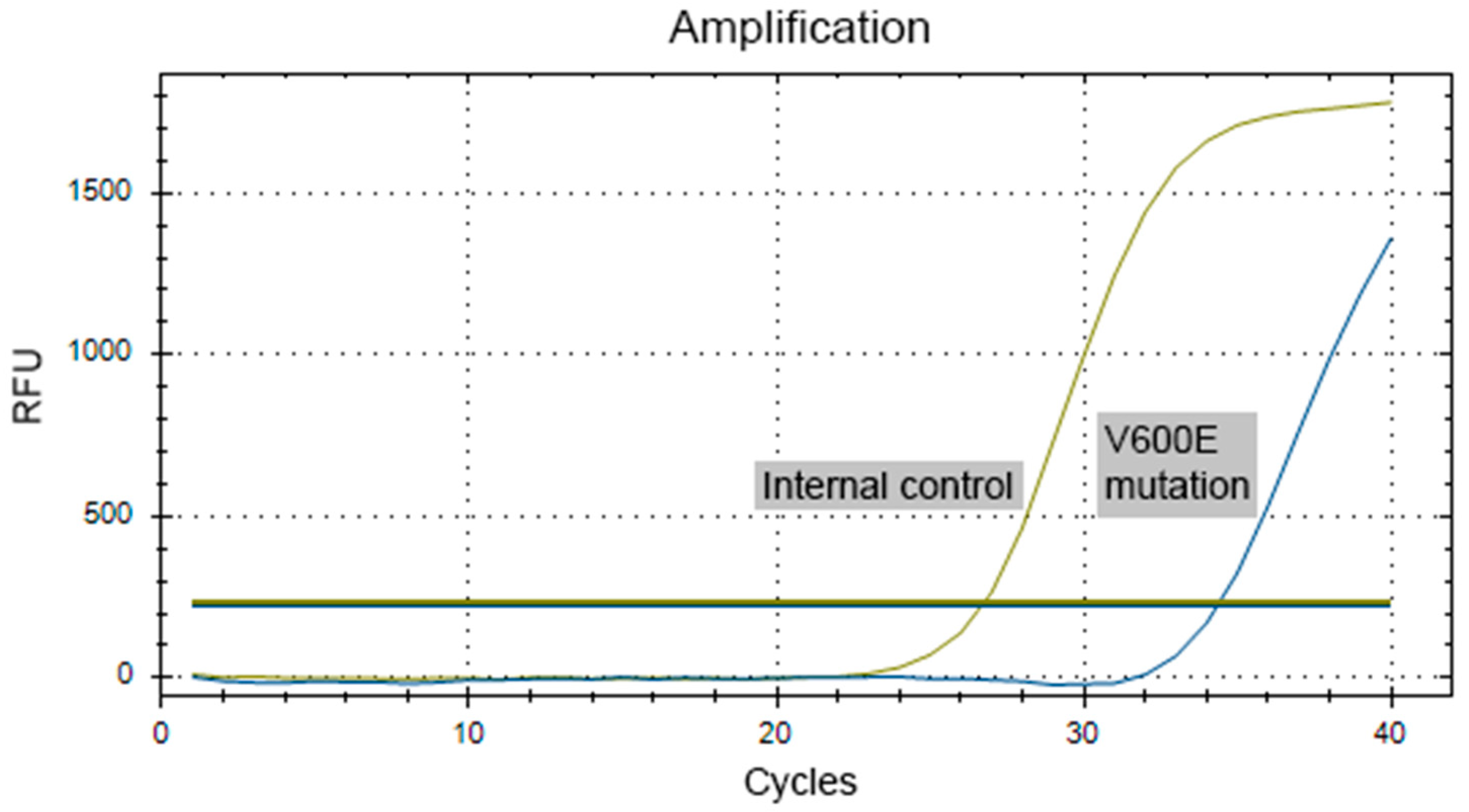

Validation of BRAF V600E Mutation

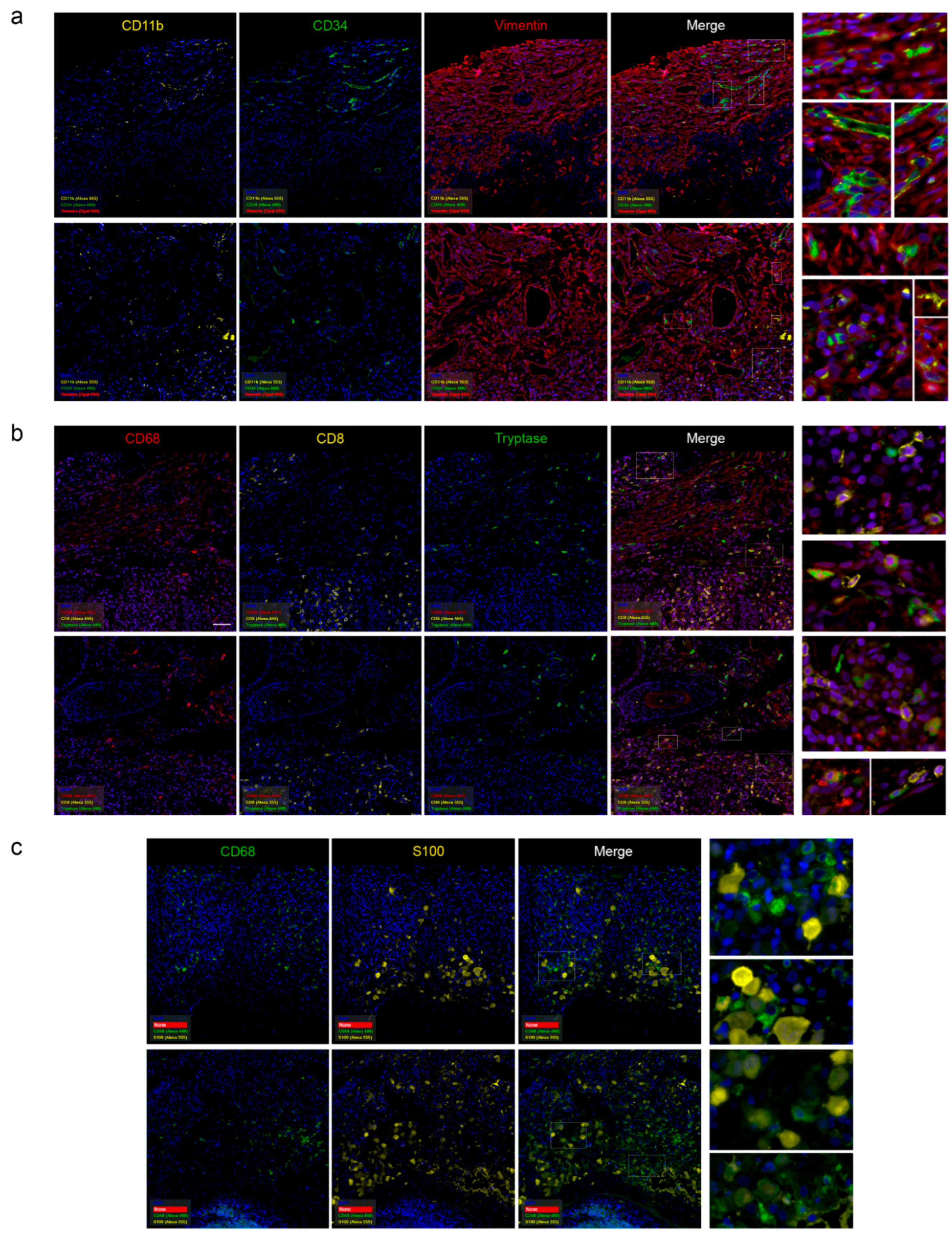

Histopathological Examination

Results

Genetic Analysis Results

Pathomorphological Analysis of the Trephine Biopsy

Discussion

Conclusion

Ethics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Gulati, N.; Allen, C.E. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Version 2021. Hematol Oncol. 2021, 39 Suppl 1, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.O. Pathologic characteristics of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. Blood Res. 2024, 59, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, J.F.; Cohen-Aubart, F.; Collin, M.; et al. Histiocytosis. Lancet. 2021, 398, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbritter, F.; Farlik, M.; Schwentner, R.; et al. Epigenomics and Single-Cell Sequencing Define a Developmental Hierarchy in Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1406–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; van Halteren, A.G.S.; Lei, X.; et al. Bone marrow-derived myeloid progenitors as driver mutation carriers in high- and low-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2020, 136, 2188–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abagnale, G.; Schwentner, R.; Ben Soussia-Weiss, P.; et al. BRAFV600E induces key features of LCH in iPSCs with cell type-specific phenotypes and drug responses. Blood. 2025, 145, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Allen, C.E. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2020, 135, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.E.; Merad, M.; McClain, K.L. Langerhans-Cell Histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.C.; Chen, J.; Liu, T.; et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adolescent patients: a single-centre retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham-Gregory, E.C.; Chakraborty, R.; Scheurer, M.E.; et al. A genome-wide association study of LCH identifies a variant in SMAD6 associated with susceptibility. Blood. 2017, 130, 2229–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.; Sevinc, A.; Ince, D.; Yuzuguldu, R.; Olgun, N. BRAF V600E Mutation: A Significant Biomarker for Prediction of Disease Relapse in Pediatric Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2019, 22, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Han, L.; Yue, M.; et al. Frequency detection of BRAF V600E mutation in a cohort of pediatric langerhans cell histiocytosis patients by next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.A.; Geoerger, B.; Dunkel, I.J.; et al. Dabrafenib, alone or in combination with trametinib, in BRAF V600-mutated pediatric Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 3806–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berres, M.L.; Lim, K.P.; Peters, T.; et al. BRAF-V600E expression in precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med, 2014; 211, 669–683correction in J Exp Med. 2015 Feb 9;212, 281. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.2013097701202015c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Hampton, O.A.; Shen, X.; et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent somatic mutations in MAP2K1 and BRAF support a central role for ERK activation in LCH pathogenesis. Blood. 2014, 124, 3007–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayed, K.; Medeiros, L.J.; Patel, K.P.; et al. BRAF and MAP2K1 mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a study of 50 cases. Hum Pathol. 2016, 52, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novosad, O.; Skrypets, T.; Pastushenko, Y.; et al. MAPK/ERK signal pathway alterations in patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Změny v signální dráze MAPK/ERK u pacientů s histiocytózou Langerhansových buněk. Klin Onkol. 2018, 31, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipova, D.S.; Raykina, E.V.; Kozlova, Y.A.; et al. Clinicogenomic associations in patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a cohort study. Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Immunopathology. 2023, 22, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, G.; Tazi, A.; Go, R.S.; Rech, K.L.; Picarsic, J.L.; Vassallo, R.; Young, J.R.; Cox, C.W.; Van Laar, J.; Hermiston, M.L.; et al. International expert consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2022 Apr 28;139, 2601-2621. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McKinney, R.A.; Wang, G. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Other Histiocytic Lesions. Head Neck Pathol. 2025, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE, et al; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016, 127, 2672–2681. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Belova, V.; Pavlova, A.; Afasizhev, R.; et al. System analysis of the sequencing quality of human whole exome samples on BGI NGS platform. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Joint Genome Institute. Available online: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/software-tools/bbtools/bb-tools-user-guide/bbduk-guide/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows—Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar]

- Picard Toolkit. version 2.22.4; Broad Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Li, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2987–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Chang, P.-C.; Alexander, D.; et al. A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Kang, H.M. Unified Representation of Genetic Variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2202–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, K. InterVar: Clinical Interpretation of Genetic Variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP Guidelines. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Francioli, L.C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B.B.; Alföldi, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020, 581, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbitoff, Y.A.; Khmelkova, D.N.; Pomerantseva, E.A.; Slepchenkov, A.V.; Zubashenko, N.A.; Mironova, I.V.; et al. Expanding the Russian allele frequency reference via cross-laboratory data integration: insights from 7452 exome samples. Natl Sci Rev. 2024, 11, nwae326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Database of Population Frequencies of Genetic Variants of the Population of the Russian Federation. [Internet]. FMBA of Russia.; 2024. Available online: https://gdbpop.nir.cspfmba.ru/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Cibulskis, K.; Lawrence, M.S.; Carter, S.L.; Sivachenko, A.; Jaffe, D.; Sougnez, C.; et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwalow, I.; Samoilova, V.; Boecker, W.; Tiemann, M. Multiple immunolabeling with antibodies from the same host species in combination with tyramide signal amplification. Acta Histochem. 2018, 120, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouenne, F.; Chevret, S.; Bugnet, E.; et al. Genetic landscape of adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis with lung involvement. Eur Respir J. 2020, 55, 1901190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, N.; Bai, R. Variant frequencies of KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A in a Chinese inherited arrhythmia cohort and other disease cohorts undergoing genetic testing. Ann Hum Genet. 2020, 84, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervier B, Haroche J, Arnaud L, Charlotte F, Donadieu J, Néel A, Lifermann F, Villabona C, Graffin B, et al; French Histiocytoses Study Group. Association of both Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease linked to the BRAFV600E mutation. Blood. 2014, 124, 1119–1126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Rao, J.; Li, C. Isolated Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the hypothalamic-pituitary region: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Savina VYu Solovyeva, S.E.; Dolzhansky, O.V.; Metelin, A.V. Clinical and morphological analysis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a child of early age. Pirogov Russian Journal of Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Pires, Y.; Jokerst, C. E.; Panse, P. M.; Kipp, B. R.; Tazelaar, H. D. Combined Erdheim-Chester Disease and Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in the Lung: A Report of 2 Patients With Overlap Syndrome. AJSP: Reviews and Reports 2020, 25, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapenko, V.G.; Baykov, V.V.; Zinchenko, A.V.; Potikhonova, N.A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: literature review. Onkogematologiya = Oncohematology 2022, 17, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.W.; Tsou, J.H.; Hung, L.Y.; Wu, H.B.; Chang, K.C. Combined Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis of skin are both monoclonal: a rare case with human androgen-receptor gene analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010, 63, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misery, L.; Rougier, N.; Crestani, B.; et al. Presence of circulating abnormal CD34+ progenitors in adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999, 117, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, P. K. , Gangenahalli G. (). Hematopoietic Stem Cell Molecular Targets and Factors Essential for Hematopoiesis. J. Stem Cel Res Ther 2018, 8, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, B.; Maduro, A.H.; Bridge, K.S.; Grey, W. Markers for human haematopoietic stem cells: The disconnect between an identification marker and its function. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 1009160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Killingsworth, M.C.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. CD68/macrosialin: not just a histochemical marker. Lab Invest. 2017, 97, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Steinfort, D.P.; Smallwood, D.; et al. CD11b immunophenotyping identifies inflammatory profiles in the mouse and human lungs. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.C.; Khan, S.Q.; Kaneda, M.M.; et al. Integrin CD11b activation drives anti-tumor innate immunity. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, J.F.; Fraitag, S.; Leborgne, M.; de Prost, Y.; Brousse, N. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis cells are activated Langerhans' cells. J Pathol. 1994, 174, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, J.H.; Tamminga, R.Y.; Kamps, W.A.; Timens, W. Expression of cellular adhesion molecules in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and normal Langerhans cells. Am J Pathol. 1995, 147, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrera Silva, E.A.; Nowak, W.; Tessone, L.; et al. CD207+CD1a+ cells circulate in pediatric patients with active Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2017, 130, 1898–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Updesh Singh Sachdeva, M.; Naseem, S.; et al. Bone marrow infiltration in Langerhan's cell histiocytosis - An unusual but important determinant for staging and treatment. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2015, 9, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Grandchamp, B.; Hetet, G.; Kannengiesser, C.; et al. A novel type of congenital hypochromic anemia associated with a nonsense mutation in the STEAP3/TSAP6 gene. Blood. 2011, 118, 6660–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yi, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Human STEAP3 mutations with no phenotypic red cell changes. Blood. 2016, 127, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ning, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Knockdown of ANXA10 induces ferroptosis by inhibiting autophagy-mediated TFRC degradation in colorectal cancer Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 588. https://10.1038/s41419-023-06114-2. Correction in Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Tian, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Bihl, J.; Shi, H. Inhibition of Ferroptosis Alleviates Early Brain Injury After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage In Vitro and In Vivo via Reduction of Lipid Peroxidation. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2021 Mar;41, 263-278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Lenahan, C.; Zhang, J.H.; Shao, A.; Zhang, J. Programmed Cell Deaths and Potential Crosstalk With Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction After Hemorrhagic Stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montalbetti, N.; Simonin, A.; Kovacs, G.; Hediger, M.A. Mammalian iron transporters: families SLC11 and SLC40. Mol Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, R.; Janecke, A.R.; Schranz, M.; et al. Ferroportin disease: a systematic meta-analysis of clinical and molecular findings. J Hepatol. 2010, 53, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Affected Organ/System | Clinical and Radiologic Features |

|---|---|

| Bones | Lytic bone lesions observed in 30–50% of cases on positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). |

| Skin | Erythematous, papular eruptions; less commonly, involvement of oral, genital, or perianal mucosa. |

| Endocrine system | Pituitary insufficiency. |

| Nervous system | Focal or extensive lesions of the pituitary stalk, hypothalamus, or pineal gland. Less commonly, infiltration of the brainstem or cerebellum with development of ataxia and dysarthria. |

| Lungs | Cystic or nodular formations presenting with obstructive, restrictive, or mixed changes, pneumothorax. |

| Liver, spleen | Early-stage: parenchymal infiltration (hepatomegaly, tumor-like nodules, mild cholestasis). Late-stage: sclerosing cholangitis-like damage (severe cholestasis) rapidly progressing to terminal liver failure and death. |

| Bone marrow | Involvement with changes in complete blood count. |

| Lymph nodes | Lymphadenopathy. |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, colonic polyps. |

| Cardiovascular system | Arterial stenosis, more common in mixed forms. |

| Parameter, units | 05/ 2024 |

06/ 2024 |

07/ 2024 |

08/ 2024 |

09/ 2024 |

10/ 2024 |

12/ 2024 |

01/ 2025 |

Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 112 | 108 | 114 | 123 | 141 | 126 | 131 | 130-150 | |

| MCV, fL | 83 | 89.1 | 85.9 | 80-99 | |||||

| MCH, pg | 28.3 | 28.9 | 27-31 | ||||||

| Leukocytes, × 109/L | 7.53 | 5.9 | 7.97 | 6.69 | 4-9 | ||||

| Platelets, × 109/L | 350 | 327 | 331 | 224 | 160-370 | ||||

| ESR, mm/h | 40 | 40 | 19 | 0-15 | |||||

| Ferritin, µg/L | 450 | 303.5 | 385 | 20-306 | |||||

| Serum Iron, µmol/L | 7.1 | 8.6 | 8.1 - 28.3 | ||||||

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 136.5 | 123.9 | 142.6 | 148.6 | 200 | 184.3 | 155.5 | 62-115 | |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 58 | 65 | 55 | 52 | 36 | 41 | 49 | ||

| Urea, mmol/L | 5.46 | 7.43 | 8.3 | 9.12 | 6.5 | 2.8-7.2 | |||

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 58.91 | 148.21 | 77.72 | 90.2 | 51.1 | 49.2 | 69.1 | 19.06 | 0-5 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L | 6.6 | 6.2 | 11.2 | 7.6 | 2-21 | ||||

| Direct bilirubin, µmol/L | 1.9 | 0-5 | |||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 97.4 | 106 | 30-120 | ||||||

| Urine specific gravity | 1007 | 1004 | 1012 | 1008-1025 | |||||

| Urine pH | 5.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 5.0-7.0 | |||||

| Urine sediment | No | No | No | ||||||

| Urine protein | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0-0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).