Background and Introduction

A placenta is defined as previa when the placental edge does not cover the internal orifice but is located within 2 cm of it. The incidence of placenta previa is approximately 5/1000 births [

1]. If placenta previa is diagnosed during the early stages of pregnancy, it usually resolves by the 28th week due to the enlargement of the uterus. According to the RCOG (

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) classification, placenta previa (PP) is classified echographically according to its clinical significance: if the placenta completely covers the internal uterine orifice (IUO ), it is considered major PP (formerly complete and partial central PP); if the placental edge lies on the IUO but does not cover the IUO, it is referred to as minor PP (formerly marginal and lateral PP) [

2]. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU-2D) is the gold standard for diagnosing PP. If PP is suspected on abdominal ultrasound performed at 20-22 weeks, it must then be confirmed with a TVU [

3,

4]. Placenta previa is a risk factor for placental accreta, which is pathological adhesion to the uterus due to a defect in the basal decidua with invasion of the myometrium by chorionic villi. In the absence of risk factors, the incidence of accreta in cases of placenta previa is approximately 1 case per 22,000 births [

5]. The risk of accreta also increases if risk factors are present: previous cesarean delivery, maternal age over 35 years, previous uterine surgery, and multiparity [

6,

7]. In cases of suspected asymptomatic major PP or in cases of doubtful accreta, a further transabdominal ultrasound (ETA) and ETV should be performed at 32 weeks of gestation to clarify the diagnosis with any further tests, adequate counseling should be provided, and an adequate team should be available to plan the delivery in an appropriate facility [

8].

For patients with placenta previa or low insertion, risks include abnormal fetal presentation, premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, vasa previa, and velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord (in which the placental end of the cord consists of divergent umbilical blood vessels surrounded only by fetal membranes). In women who have had a previous cesarean delivery, placenta previa increases the risk of placenta accreta; the risk increases significantly with the number of previous cesarean deliveries (from approximately 6-10% for one cesarean delivery to > 60% for > 4) [

9,

10]. Patients with central placenta previa undergo elective cesarean delivery. The afterbirth can cause significant bleeding even in the absence of accreta. Compressive uterine sutures are conservative surgical procedures used as a second-line treatment to control severe post-partum emorragies and avoid hysterectomy [

11,

12]. The compressive hemostatic suture in these cases is according to Cho suture [

13]. This suture involves the use of a straight needle and 0-gauge monofilament to compress the anterior and posterior walls of the uterus with simple stitches that pierce the uterus through its entire thickness. It is a ligature that can be repeated during the same procedure. The Cho suture consists of four multiple square sutures, which appear as a square when viewed from the uterine wall.

Case Presentation

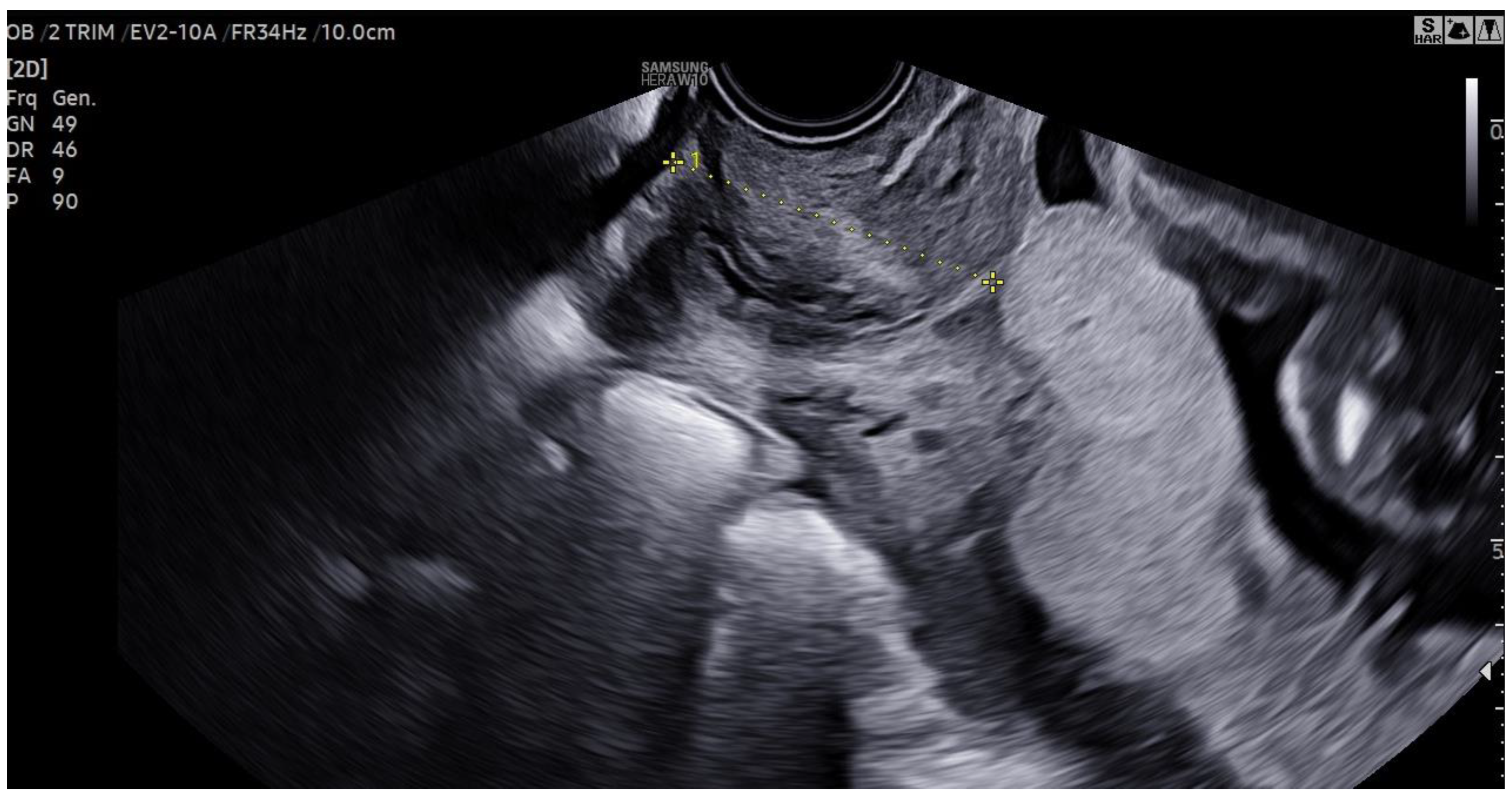

A 46-year-old woman underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF). Pregnancy progressed normally, with physiological development and appropriate fetal growth. In the third trimester, an ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of a central placenta previa.

A cesarean section was planned. In preparation, units of packed red blood cells, plasma, and coagulation factors were arranged, and the transfusion center and blood bank were notified due to the risk of potential massive hemorrhage. The surgery was performed electively at 38 weeks of gestation, considering the additional risk factor of advanced maternal age. The newborn was in excellent condition at birth, with an Apgar score of 9/10 and an umbilical cord pH of 7.3.

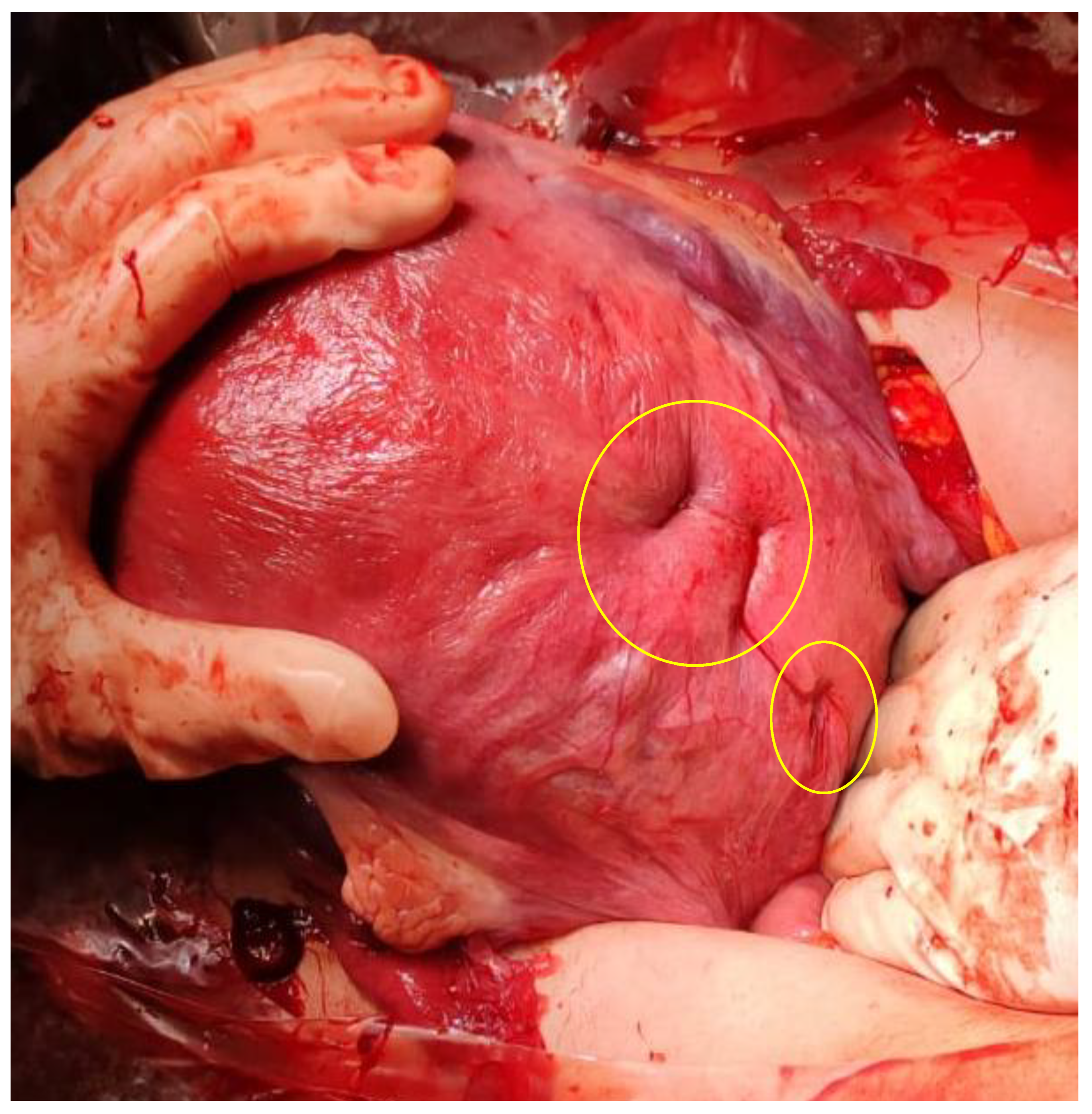

Manual delivery of the placenta proved challenging, particularly in the central isthmic region covering the internal cervical os. The uterus was exteriorized, and careful removal of the placenta followed by curettage of the implantation site was performed. Although the uterus appeared well-contracted, bleeding persisted from the placental bed. A marker was placed in the cervical canal to prevent closure during suture.

Because the bleeding vessels were located along the midline of the placental bed, standard Cho sutures were deemed unsuitable, as they would require bringing the anterior and posterior uterine walls together—risking closure of the cervical canal. Instead, modified Cho compression sutures were applied exclusively to the posterior isthmic wall. One suture was placed at the cervical level, and the second just above it. A resorbable monofilament thread was used.

The suture technique involved passing the needle through the uterine cavity from anterior to posterior, exiting the posterior wall, and reinserting it 2–3 cm laterally from posterior to anterior. The needle was then passed again from anterior to posterior, exiting the posterior wall approximately 2–3 cm below the previous exit site. Finally, the stitch was completed by reinserting 2–3 cm laterally into the posterior wall. The two ends of the thread were tied using a flat surgical knot to enhance compression. Both sutures were placed medially along the posterior wall at the level of the cervical isthmus.

Discussion and Conclusions

In the clinical case described, several risk factors could significantly impact maternal and fetal outcomes. These include advanced maternal age, the presence of placenta previa, and its central location—factors that collectively contribute to a high-risk obstetric scenario.

Since mass screening for abnormal placentation is not feasible, it is crucial to focus on in-depth evaluation of at-risk populations—those with placenta previa, prior uterine surgery or curettage, or advanced maternal age. Familiarity with the available diagnostic tools is essential. Improved maternal-fetal outcomes are achievable through accurate prenatal diagnosis and a coordinated multidisciplinary approach during delivery.

Transvaginal ultrasound remains the most reliable diagnostic method for identifying placenta previa in all its forms. Surgical management should be entrusted to an experienced team, particularly because the risk of placenta accreta exists even in patients without a history of cesarean delivery, the primary known risk factor.

Compressive sutures are highly effective in managing uterine bleeding and promoting contractility. In this case, a modified Cho suture was used to achieve hemostasis along the median plane of the posterior uterine wall. This demonstrates that, in expert hands, compression sutures can be adapted to the specific challenges of the clinical situation while preserving their effectiveness.

Funding

We have no funding to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to concerns regarding participant anonymity. Requests for access to the data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. The study was exempt from evaluation by our local Ethical Comitee.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Cresswell JA, Ronsmans C, Calvert C, Filippi V. Prevalence of placenta praevia by world region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2013, 18, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, Belfort MA, Burton GJ, Collins SL, Dornan S, Jurkovic D, Kayem G, Kingdom J, Silver R, Sentilhes L; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management: Green-top Guideline No. 27a. BJOG 2019, 126, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 120, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain V, Bos H, Bujold E. Guideline No. 402: Diagnosis and Management of Placenta Previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020, 42, 906–917.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carusi, DA. The Placenta Accreta Spectrum: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018, 61, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion. Placenta accreta. Number 266, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002, 77, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu H, Wang L, Gao J, Chen Z, Chen X, Tang P, Zhong Y. Risk factors of severe postpartum hemorrhage in pregnant women with placenta previa or low-lying placenta: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024, 24, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Beekhuizen HJ, Stefanovic V, Schwickert A, Henrich W, Fox KA, MHallem Gziri M, Sentilhes L, Gronbeck L, Chantraine F, Morel O, Bertholdt C, Braun T, Rijken MJ, Duvekot JJ; International Society of Placenta Accreta Spectrum (IS-PAS) group. A multicenter observational survey of management strategies in 442 pregnancies with suspected placenta accreta spectrum. A multicenter observational survey of management strategies in 442 pregnancies with suspected placenta accreta spectrum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021, 100 (Suppl. S1), 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahar A, Abusham A, Eskandar M, Sobande A, Alsunaidi M. Risk factors and pregnancy outcome in different types of placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009, 31, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usta IM, Hobeika EM, Musa AA, Gabriel GE, Nassar AH. Placenta previa-accreta: risk factors and complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005, 193, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price N, B-Lynch C. Technical description of the B-Lynch brace suture for treatment of massive postpartum hemorrhage and review of published cases. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2005, 50, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baskett, TF. Uterine compression sutures for postpartum hemorrhage: efficacy, morbidity, and subsequent pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 110, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN. Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 96, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller J, Shamshirsaz A, Abuhamad A. Advances in Imaging for Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2025, 145, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).