1. Background

The word accreta comes from the Latin language, where accrescere means to adhere, to attach, this pathology being described for the first time in the specialized literature, in 1930 [

1,

2].

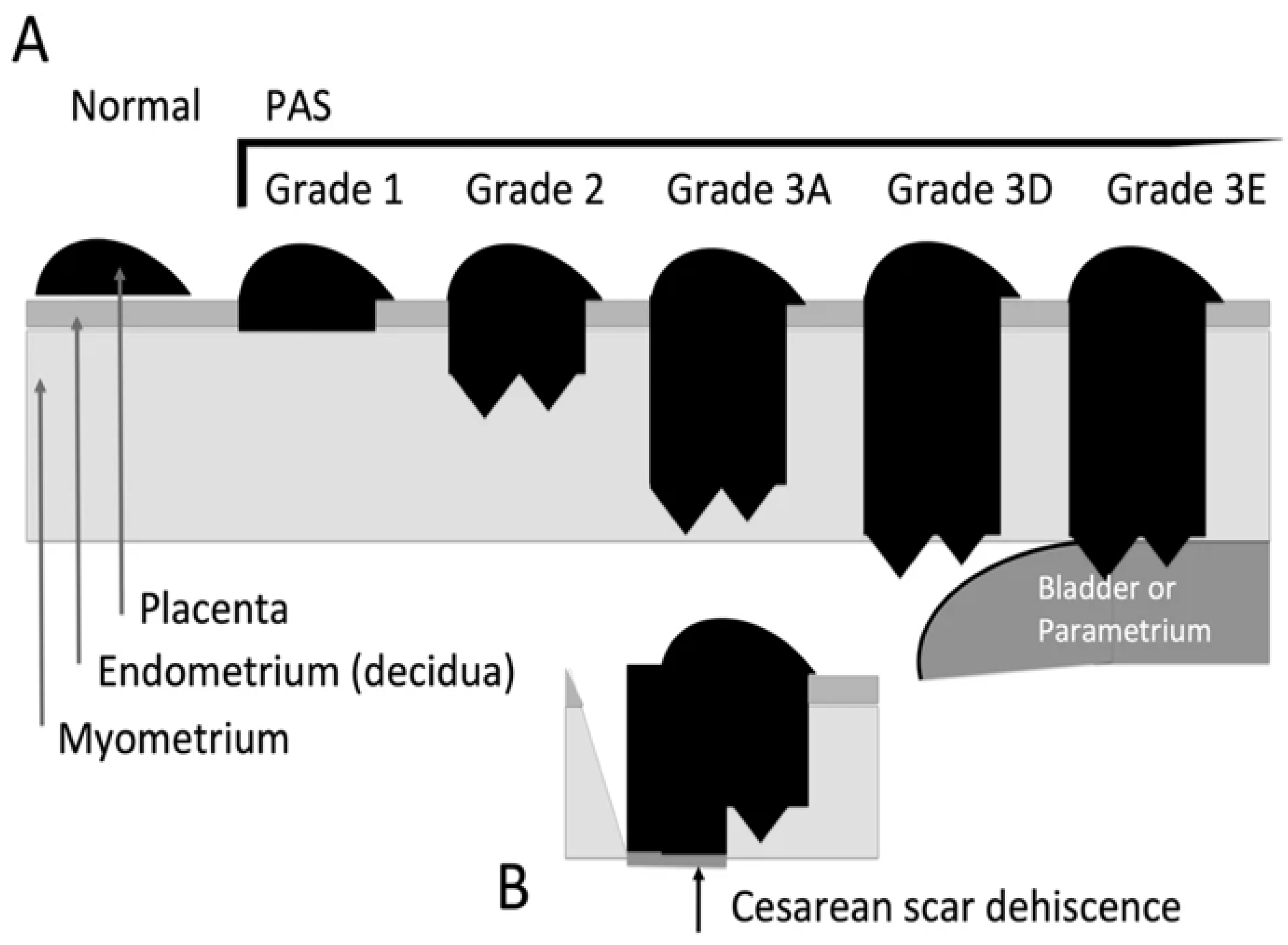

Depending on the thickness of the trophoblastic invasion, the placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is divided into placenta accreta, placenta increta and placenta percreta. The most severe, but also the least common form of placental invasion is placenta percreta with a ratio of 80:15:5 [

3,

4].

Because the terms accreta, increta and percreta, used in the past do not give a correct picture of the level of implantation from the histopathological point of view, the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) proposed another division of PAS into 3 degrees of severity, 3

RD degree being in turn divided into another 3 subcategories (A - deep invasion >75% of the uterine wall; 3D - disruption of the uterine serosa; 3E - extrauterine invasion) [

5].

Figure 1.

FIGO classification of placenta accreta types - Grade 1 - Non-invasiveness; Grade 2 - Superficial invasiveness Grade 3 - Deep invasiveness [

5]

Figure 1.

FIGO classification of placenta accreta types - Grade 1 - Non-invasiveness; Grade 2 - Superficial invasiveness Grade 3 - Deep invasiveness [

5]

The main risk factors for this type of abnormal placental invasion are placenta praevia in personal pathological history and previous cesarean delivery. The patients who associate placenta praevia, have a risk of developing an adhesion defect of around 3.3-4%, while in patients who associate placenta praevia and a previous caesarean section, the risk reaches 50-67% [

6].

An increased risk of developing a placenta accreta spectrum pathology was also observed in smoking patients, those who had a short interval between the two cesarean births or those in whom, assisted reproduction techniques were used [

7,

8].

Given the fact that in recent years, the completion of birth by cesarean section has experienced a worrying increase, this fact has also attracted an increase in the incidence of the pathology of the placenta accretta spectrum [

9].

The symptomatology of this kind of pathology, whether we are talking about the placenta accreta spectrum or whether we are talking about positional defects of the placenta, such as praevia type, primarily includes vaginal bleeding. This occurs with a frequency of approximately 5% in the second trimester of pregnancy and up to 50% in the third trimester [

10].

In exceptional situations of severe aberrant implantation of the percretta type, urinary symptoms may appear, such as macroscopic hematuria or dysuria, if the placental invasion was done anteriorly, or rectorrhagia or melena symptoms in the case of patients in whom the placental invasion was done posteriorly, involving the small intestine or the large intestine [

11].

In case of vaginal bleeding, the differential diagnosis of PAS or placenta praevia must be made with one of the following situations: abruptio placentae, vasa praevia, uterine rupture, cervical pathology and traumatic injuries of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, premature labor or traumatic lesions of the vaginal wall.

The clinical diagnosis of placenta praevia cannot be established with certainty without a pathological examination. The presence of PAS can be clinically suspected if the patient presents to the Emergency Unit, complaining of spontaneous vaginal bleeding which occured after 24 weeks of amenorrhea, unaccompanied by painful uterine contractions and when examining the patient, the basal uterine tone is normal [

10].

Morphological screening of the second trimester performed between 20 and 22 weeks can establish the location, grade, placental echogenicity, as well as normal or pathological insertion of the umbilical cord [

12].

The diagnosis of this type of pathology can be made either with ultrasound or by MRI. According to specialized literature, the diagnosis can be made with the help of obstetrical ultrasound, some studies even conferring a higher or equal sensitivity to the ultrasound diagnosis compared to the MRI exam. The sensitivity and specificity in the case of the ultrasound examination can go up to 92 and 86%, respectively, compared to the MRI examination in which it can reach 93% and 91%, respectively [

13,

14]. The final diagnosis in terms of adhesiveness is made by histo-pathological examination which can establish with microscopic accuracy the degree of penetrability and trophoblastic invasion [

14,

15].

Placenta percreta complications, involving the mother, which can be mentioned include necessity hysterectomy, appreciable bleeding, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or multiple organ failure, that can ultimately lead to maternal death [

16].

Fetal complications include preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and intrauterine fetal death.

A case where placenta accreta spectrum is suspected will be admitted to a tertiary center with the permanent presence of a gynecologist, an anesthetist and a surgeon.

In the situation of a surgical intervention in a patient suspected of having placenta percreta with bladder or ureteral invasion, the presence of an urologist is also necessary.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends, in an effort to increase patient safety, that the surgical intervention to be performed by a team of experienced obstetricians but also to include surgeons from other specialties such as Urology or General Surgery [

17,

18].

If the presence of a placenta accreta spectrum pathology is suspected, it is preferable that the delivery to be performed between 34 and 36 weeks of pregnancy, with completion of the delivery by elective caesarean section, followed by hysterectomy if necessary [

19].

Before the surgical intervention, it is necessary to ensure that the Intensive Care Unit is capable to handle this type of case, 3-4 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma should be stored and prepared for immediate transfusion but also some fast-acting hemostatic drugs, such as recombinant factor VII - NoVo Seven [

19].

Some authors consider that the conservative treatment of placental adhesion pathology might be useful, although this option can be burdened by major complications such as appreciable hemorrhage, endometritis and recurrence of placenta accreta spectrum pathology [

20].

2. Materials and Methods

The present study aimed to analyze the incidence of placenta praevia and placenta accreta spectrum in the County Emergency Clinical Hospital "Saint Andrew the Apostle" Constanta within the Obstetrics-Gynecology II department.

The study was retrospective, covering a 5-year period between 01.01.2018 and 31.12.2022. Data were collected from the department's observation sheets and operative protocols. Between 01.01.2018 and 31.12.2022, 13,841 patients were admitted to the Obstetrics and Gynecology department.

Table 1.

Distribution of patients by type of admission.

Table 1.

Distribution of patients by type of admission.

| |

Births |

Caesarean |

Gravida |

Gynaecology |

Total Admissions |

| 2018 |

1214 |

585 |

728 |

782 |

2724 |

| 2019 |

1135 |

526 |

692 |

879 |

2706 |

| 2020 |

1503 |

576 |

601 |

684 |

2788 |

| 2021 |

1477 |

654 |

593 |

652 |

2722 |

| 2022 |

1379 |

641 |

724 |

798 |

2901 |

| |

6708 |

2982 |

3338 |

3795 |

13841 |

Among the 6708 patients hospitalized for childbirth assistance, 25 presented the diagnosis of placenta praevia complicated with bleeding. The total incidence was 0.82%.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients with placenta praevia

Table 2.

Distribution of patients with placenta praevia

| |

Births |

Caesarean |

Placenta Praevia |

| 2018 |

1214 |

585 |

5 (0.85%) |

| 2019 |

1135 |

526 |

4 (0.76%) |

| 2020 |

1503 |

576 |

6 (1.04%) |

| 2021 |

1477 |

654 |

5 (0.76%) |

| 2022 |

1379 |

641 |

5 (0.78%) |

| |

6708 |

2982 |

25 (0.82%) |

Among the 6708 patients hospitalized for childbirth assistance, 17 presented the diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum. The total incidence was 0.57%.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients with placenta acreta spectrum.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients with placenta acreta spectrum.

| |

Births |

Caesarean |

Placenta Acreta |

| 2018 |

1214 |

585 |

4 (0.68%) |

| 2019 |

1135 |

526 |

3 (0.57%) |

| 2020 |

1503 |

576 |

3 (0.52%) |

| 2021 |

1477 |

654 |

4 (0.61%) |

| 2022 |

1379 |

641 |

3 (0.46%) |

| |

6708 |

2982 |

17 (0.57%) |

3. Discussion

The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound examinations can reach up to 92% and 86%, respectively, compared to MRI examinations, which can reach up to 93% and 91%, respectively in the detection of cases with abnormal placental penetration [

13]. In our study the sensitivity of ultrasound examination was 96% and the specificity 92% compared with MRI examination with an sensitivity of 96% and the specificity of 88%. The final diagnosis in terms of adhesiveness is made by histopathological examination, which can establish the degree of penetrability and trophoblastic invasion with microscopic accuracy [

20]. In our study - 17 cases of anatomopathological examination revealed placenta acreta-increta-percreta pathology. When placenta accreta spectrum pathology is suspected, the patient will be admitted to a tertiary center with the permanent presence of a gynecologist, an anesthesiologist, and a surgeon. If bladder or ureteral invasion is suspected, the presence of an urologist is also necessary [

19]. All of the percreta cases of our study that involved the urinary bladder were confirmed by cystoscopy, and the presence of the urologist in the multidisciplinary team was necessary. The total hysterectomy and the suture of the bladder was enough to solve all the cases.

The total incidence of placenta praevia in the study group was 0.82%. These data are in line with the worldwide specialized literature. For example, a 10-year retrospective study at the Cleveland Maternity Hospital shows an incidence of placenta praevia of 0.8% [

21]. Similarly, a study conducted in Canada showed an incidence of 0.73% of placenta praevia [

22]. Although these studies show a small percentage variation from one another, it is necessary to also consider that some meta-analyses indicate a much lower incidence of placenta praevia, around 0.15% in the total number of births [

23].

In our study, it is imperative to note that 2982 patients underwent cesarean section, constituting 44.5% of the total births. Of the 25 cases of placenta praevia, 18 cases were identified in patients with a history of uterine scarring, accounting for 72%. Among the 25 placenta praevia cases, 17 were diagnosed as placenta accreta, representing 68%. Within the 17 accreta cases, 3 involved invasion-type increta, and another 3 involved invasion-type percreta, amounting to 17.6%. In all of this cases of placenta increta (17,6%) and percreta (17,6%), the total hysterectomy was done. The distribution by gestational and parity grades does not yield significant data, with multiparous cases comprising 49% of cases. However, it is crucial to consider additional etiological factors such as smoking, age, and alcohol consumption. In relation to the etiopathogenic mechanism associated with the development of placenta praevia pathology, a set of factors can be identified as having presented suggestive evidence and are considered major predisposing factors in the emergence of this anomaly. These factors include the history of cesarean section deliveries, advanced maternal age, smoking, abortions, and male fetuses. Additionally, it is acknowledged that pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia are not contributing factors [

24].

In women over the age of 35, there has been a noticeable increase in the incidence of placenta praevia, a condition that can lead to severe complications during delivery, including life-threatening hemorrhage. This increase may be attributed to various factors such as changes in the uterine structure, like the presence of fibroids, endometrial alterations, chronic endometritis, and other related conditions. Age-related structural changes in the uterine lining may disrupt normal placental implantation. Additionally, older women often have a history of multiple pregnancies, miscarriages, or uterine surgeries, all of which can elevate the risk of placenta praevia.

Our study found that 94.1% of the abnormal placental adhesion group had previous cesarean sections, significantly higher than the 44.5% general incidence and the 72% cesarean incidence in the placenta praevia group. Uterine scarring from prior surgeries appears to influence placental positioning, as the scarring near the cervix may lead to the implantation of the placenta in lower segments, increasing the risk of placenta praevia. With each additional cesarean delivery, the likelihood of placenta praevia grows due to accumulating scar tissue, particularly in women with multiple prior cesareans [

25].

A potentially helpful intervention in managing these cases is uterine artery embolization (UAE), which has been found to reduce hemorrhage risk and limit the need for blood transfusions. UAE is a valuable alternative to traditional cesarean hysterectomy, particularly when uterine preservation is desired. Studies have shown that UAE, as part of a standardized protocol, can lower blood loss significantly, thereby supporting better maternal outcomes [

26].

Another observation is the association between male fetuses and placenta praevia, although the reasons are not fully understood. Hypotheses include the influence of male fetal hormonal environments on placental attachment and possible growth patterns of male fetuses that could contribute to abnormal placental positioning [

27]. Furthermore, lifestyle factors like smoking—present in 70.5% of our cases compared to a general Romanian smoking rate of about 55%—can impact placental positioning. Exposure to nicotine and carbon monoxide may lead to chronic placental hypoxia, increasing the risk of placenta praevia [

28,

29,

30].

Although uterine fibroids are not traditionally considered a risk factor, our study found that 30% of placenta praevia cases were associated with fibroids, which were only observed in women over 30. Occasionally, pregnant women with placenta praevia report moderate abdominal pain unrelated to contractions, potentially due to vascular compression, including on formations like Buhler's arc [

31]. Moreover, learning about placenta praevia during the second-trimester morphology scan can cause considerable stress, similar to the distress experienced by trauma patients [

32].

In our study, all placenta praevia cases were successfully managed by cesarean section without rupture of placental blood vessels. Maternal anemia was mild to moderate overall, although fetal anemia, while rare, can become a serious complication in complex cases [

33].

There were only 5 cases of depressive syndromes of medium intensity during pregnancy in our group. Although, the diagnosis often causes great fears to young pregnant women, the type of personality and the degree of resistance to stress of each patient matters a lot. It seems that patients with a type of melancholic behavior are more prone to develop depressive syndromes during pregnancy or in conditions of high stress [

34].

4. Conclusions

Smoking, uterine scars and uterine fibroids remain the most important etiological factors involved in placenta praevia with pathological adhesion.

Among the placenta praevia cases, most were suspected of the accreta type based on imaging studies, initially detected using a ultrasonography scan that then confirmed using (IRM + ultrasonography) .

The accuracy of MRI imaging has been relatively good, with only a few cases requiring a multidisciplinary team for management of percreta placentas affecting both the bladder and rectum, where other investigations as cystoscopy and recto-colonoscopy were required.

The multidisciplinary medical team (gynecologist, urologist, surgeon and anesthesiologist), represents a gold standard in managing the placenta praevia with the pathological adhesion cases.

Cesarean section followed by hysterectomy represented the surgical therapy in cases of placenta increta or percreta, with additional bladder suture in placenta percreta with bladder invasion.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author, Lucian Șerbănescu.

Acknowledgments

No Acknowledgements.

Contribution

All authors had equal contributions. The authors declare no conflict of interest.This research received no external funding.

References

- Benirshke, K.; Burton, R.N.; Baergen, R. Pathology of the Human Placenta; 6th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 204.

- Volochovič, J.; Ramašauskaitė, D.; Šimkevičiūtė, R. Antenatal Diagnostic Aspects of Placenta Percreta and Its Influence on the Perinatal Outcome: A Clinical Case and Literature Review. Acta Med. Litu. 2017, 23, 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Usta, I.M.; Hobeika, E.M.; Musa, A.A.; Gabriel, G.E.; Nassar, A.H. Placenta Previa-Accreta: Risk Factors and Complications. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 1045–1049. [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.; Cheung, Y.K.; Zuccollo, J., et al. Evaluation of Sonographic Diagnostic Criteria for Placenta Accreta. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2008, 36, 551. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.L.; Baergen, R.; Ernst, L.M., et al. Classification and Reporting Guidelines for the Pathology Diagnosis of Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS) Disorders: Recommendations from an Expert Panel. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 2382–2396. [CrossRef]

- Piñas Carrillo, A.; Chandraharan, E. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Management with Special Reference to the Triple P Procedure. Women’s Health (Lond.) 2019, 15, 1745506519878081. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.E.; Sellers, S.; Spark, P., et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Placenta Accreta/Increta/Percreta in the UK: A National Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52893. [CrossRef]

- Thurn, L.; Lindqvist, P.G.; Jakobsson, M., et al. Abnormally Invasive Placenta—Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Antenatal Suspicion: Results from a Large Population-Based Pregnancy Cohort Study in the Nordic Countries. BJOG 2016, 123, 1348–1355. [CrossRef]

- Riteau, A.S.; Tassin, M.; Chambon, G., et al. Accuracy of Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Placenta Accreta. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94866. [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Placenta Praevia, Placenta Praevia Accreta, and Vasa Praevia: Diagnosis and Management, Green-Top Guidelines No. 27a and 27b; RCOG Press: London, UK, 2018.

- Shepherd, A.M.; Mahdy, H. Placenta Accreta. In: StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563288/ (accessed on 26 Feb 2022).

- McShane, P.M.; Heyl, P.S.; Epstein, M.F. Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity Resulting from Placenta Previa. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985, 65, 176–182.

- Hong, S.; Le, Y.; Lio, K.U., et al. Performance Comparison of Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Their Diagnostic Accuracy of Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Insights Imaging 2022, 13(1),50. [CrossRef]

- Bartels, H.C.; Postle, J.D.; Downey, P.; Brennan, D.J. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Review of Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Biomarkers. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 1507674. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011; 144(5),646-74. [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.M.; Fox, K.A.; Barton, J.R., et al. Center of Excellence for Placenta Accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212(5),561-8. [CrossRef]

- South Australian Perinatal Practice Guidelines Workgroup. Antepartum Hemorrhage or Bleeding in the Second Half of Pregnancy; South Australian Perinatal Guidelines, 2013.

- Yoong, W.; Karvolos, S.; Damodaram, M., et al. Observer Accuracy and Reproducibility of Visual Estimation of Blood Loss in Obstetrics: How Accurate and Consistent Are Health-Care Professionals? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 281, 207.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Placenta Accreta Spectrum, Obstetric Care Consensus, Number 7; 2018. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/obstetric-care-consensus/articles/2018/12/placenta-accreta-spectrum (accessed on 11 Sep 2022).

- Bartels, H.C.; Postle, J.D.; Downey, P.; Brennan, D.J. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Review of Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Biomarkers. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018:1507674. [CrossRef]

- Reycraft, J.L., et al. Incidence of Placenta Previa during a Ten-Year Period at Cleveland Maternity Hospital (1931–1940). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1942, 44, 509–512. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Abdullah, A.; Mamdoh, E.; Adekunle, S.; Mohamed, A. Risk Factors and Pregnancy Outcome in Different Types of Placenta Previa. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2009, 31, 126–131.

- Kollmann, M.; Gaulhofer, J.; Lang, U.; Klaritsch, P. Placenta Praevia: Incidence, Risk Factors and Outcome. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29(9):,1395–1398. [CrossRef]

- Jenabi, E.; Salimi, Z.; Bashirian, S.; Khazaei, S.; Ayubi, E. The Risk Factors Associated with Placenta Previa: An Umbrella Review. Placenta 2022, 117, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Abousifein, M.; Shishkina, A.; Leyland, N. Addressing Diagnosis, Management, and Complication Challenges in Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorder: A Descriptive Study. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3155. [CrossRef]

- Louwen, F.; Zacharowski, K.; Raimann, F.J. Management and Outcome of Women with Placenta Accreta Spectrum and Treatment with Uterine Artery Embolization. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 1062. [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.W.; Demissie, K.; Liu, S., et al. Placenta Praevia and Male Sex at Birth: Results from a Population-Based Study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2000, 14, 300–304. [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.H.; Hsieh, C.C.; Hsu, J.J., et al. Risk Factors for Placenta Previa in an Asian Population. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2007, 97, 26–30. [CrossRef]

- Hobeiri, F.; Jenabi, E. Smoking and Placenta Previa: A Meta-Analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 2985–2990.

- Tsuji, M.; Shibata, E.; Askew, D.J., et al. Associations between Metal Concentrations in Whole Blood and Placenta Previa and Placenta Accreta: The Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS). Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 40. [CrossRef]

- Baz, R.O.; Scheau, C.; Baz, R.A.; Niscoveanu, C. Buhler’s Arc: An Unexpected Finding in a Case of Chronic Abdominal Pain. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2020, 29, 304. [CrossRef]

- Anghele, M.; Marina, V.; Moscu, C.A., et al. Emotional Distress in Patients Following Polytrauma. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1161–1170. [CrossRef]

- Franciuc, I.; Surdu, M.; Fratiman, L. Anemia of Prematurity Management in the Tertiary Neonatology Centre of Clinical Emergency County Hospital Constanta. ARS Medica Tomitana, 2022, 1(28), 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Moscu CA, Marina V, Anghele M, Anghele AD, Dragomir L. Did Personality Type Influence Burn Out Syndrome Manifestations During Covid-19 Pandemic? Int J Gen Med. 2022,15, 5487-5498.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).