1. Introduction

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gut-brain disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered stool frequency or form [

1,

2]. Clinical manifestation of IBS can be classified into four-subtypes, including constipation-predominant (IBS-C), diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), mixed (IBS-M), and unclassified (IBS-U) subtypes [

3,

4,

5]. Globally, 9.2% of adults meet the diagnostic criteria of IBS and a higher prevalence is reported in women (12.0%) than men (8.6%) [

5,

6]. Beyond gastrointestinal symptoms, IBS is often followed by substantial systemic sequelae such as fatigue, fibromyalgia and chronic pain, and lower-urinary-tract symptoms over the lifetime, which can significantly reduce health-related quality of life [

7,

8,

9,

10].

In addition to these physical impacts, IBS has been suggested to be implicated in poor mental health, and in particular depression. Indeed, Emerging evidence points to the potential role of bidirectional gut-brain axis in the development of depression among those with IBS. Proposed mechanisms include gut microbiota dysbiosis, hyper-activations in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, serotonergic signaling abnormalities, and reduced vagal (parasympathetic) tone [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Consistent with this proposed basis for the comorbidity of IBS and depression, empirical work has documented a higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, such as depressive or anxiety symptoms and disorders, among individuals with IBS, compared to the general population [

10,

16,

17,

18]. For example, a meta-analysis of 73 studies documented that the prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among those with IBS were 23.3% and 28.8%, respectively, two-to-three-fold greater than those conditions among general population [

16].

While the IBS-depression associations among Western populations such as North American, European, and Oceanian are well documented [

16,

17], evidence among Korean population has been limited to small or convenience samples that relied on screening tools for depression measure. For instance, a single-center study of Korean adults (124 IBS outpatients and 91 healthy controls) presented that 31% of the cases and 16.5% of the non-cases were classified as depression, measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [

19]. Another study based on the Korea Nurses’ Health Study cohort demonstrated that 13.5% of nurses with IBS (n=178) were screened positive for depression, measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [

20]. While these previous studies showed a higher prevalence of depression among those with IBS compared to healthy controls, their findings were based on relatively small-sized samples and self-reported screening tools for depression rather than diagnostic measures, limiting representativeness and robustness of the findings and thereby necessitating further investigation.

To more rigorously replicate findings regarding the comorbidity of IBS and depression outside of Western contexts, we sought to investigate the association between IBS and depression among a nationally representative sample of Korean adults. We hypothesized that individuals with IBS would be more likely to be diagnosed with depression than their counterparts without IBS. We used a health-screening subset of the 2021 National Health Insurance (NHIS) database, which includes diagnostic information of relevant disorders and health-screening exam records among 3.9 million Korean populations, enabling to understand such relationship in a nationwide setting among the population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Sample

Data from the 2021 Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database were utilized. In South Korea, healthcare utilization is primarily covered by the NHIS, in which all Korean citizens are registered and enrolled. This provides an universal coverage for healthcare utilization for 97% of the entire population, together with an extra medical aid support for 3% of the economically vulnerable subpopulation [

21,

22,

23]. In 2021, a total of 51,412,000 Koreans (99.3% of the entire population) were enrolled in the national health insurance program. The NHIS database includes information pertaining to demographic and qualifications (e.g., age, gender, residential area, income, and insurance enrollment type), healthcare utilization obtained through the providers’ claiming process (e.g., diagnostic, therapeutic, and prescription information covered by the national insurance) [

21,

22,

23].

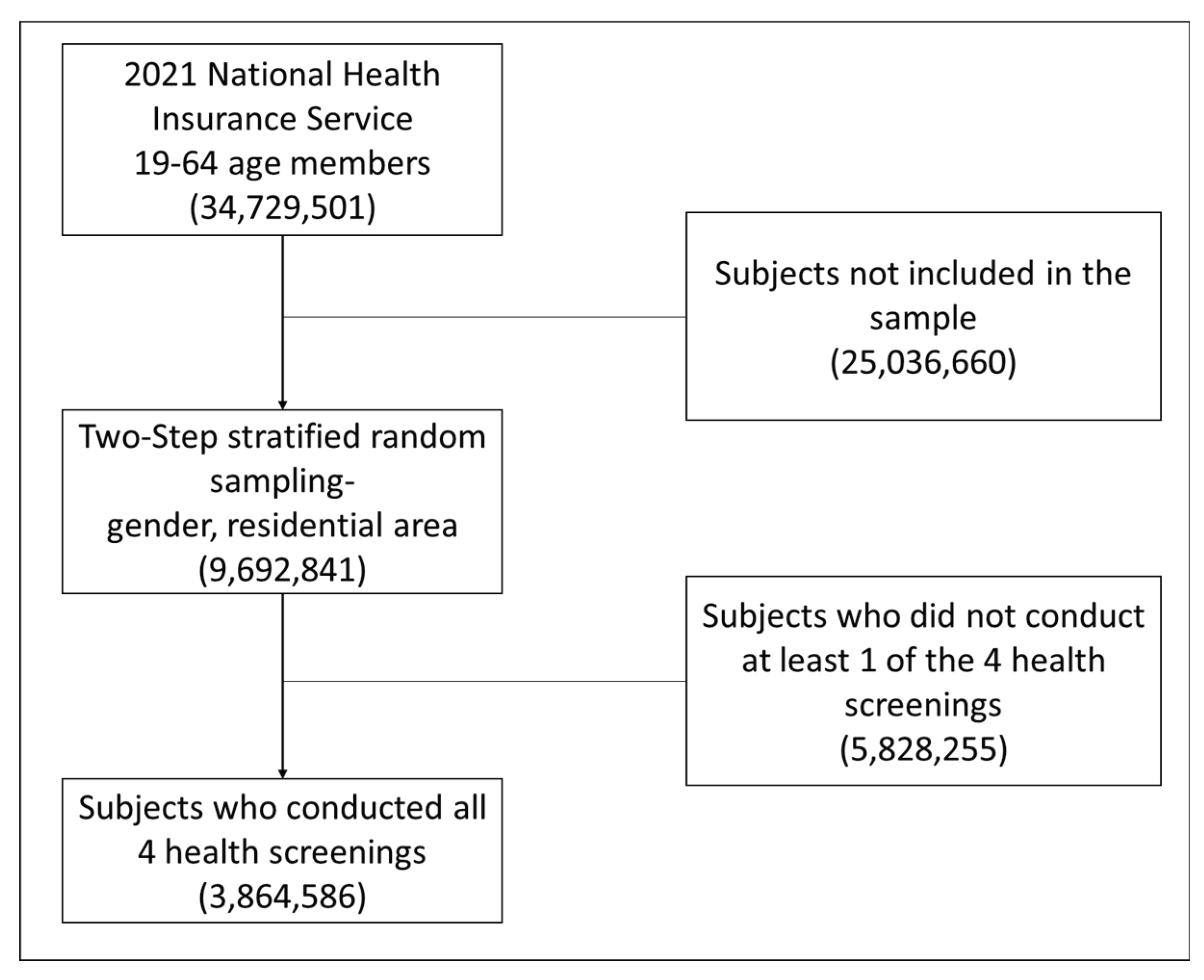

Of healthcare utilization data obtained between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2021, from the NHIS database, those pertaining to individuals between 19 and 64 years were included, identifying 34,729,501 individuals. A sex-and-region stratified two-stage sampling approach was then used, yielding a sample of 9,692,841 individuals. The NHIS provides a coverage for a biennial health screening service, in which information on health-related behaviors, anthropometry information and laboratory results is obtained [

21,

22,

23]. This screening information was used to narrow the sample to individuals for whom information on smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and body-mass index was provided. After excluding those with incomplete information on any of those variables, our final analytic sample included 3,864,586 participants (

Figure 1).

This study used publicly available and de-identified anonymized dataset, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongshin University (IRB number: 1040708-202212-SB-045).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depression

Depression, the outcome of interest in this study, was defined by the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes F32.X (depressive episode, including single episode of major or other depressive disorders) or F33.X (recurrent depressive disorder). Depression cases were identified by the presence of any of these diagnostic codes at least once during January 1, 2021, until December 31, 2021 [

24,

25].

2.2.2. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Our primary exposure of interest, IBS was defined by the ICD-10 code K58.X (irritable bowel syndrome and its subtypes). Exposure status was classified as “exposed” when individuals were diagnosed as IBS at least once between January 1, 2021, until December 31, 2021 [

26,

27,

28].

2.2.3. Covariates

A range of sociodemographic, behavioral, and medical conditions were included as covariates. Sociodemographic information included age (in years), sex, and residential area, which were extracted from the individual NHIS records.

To assess overall health condition, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [

29], a widely used tool to evaluate the overall comorbidity in clinical research, was employed. Based on the prespecified 17 chronic condition groups (e.g., acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, dementia), each disease that belongs to the groups is assigned a weight from 1 to 6 (e.g., 2 for cancer without metastasis; 6 for cancer with metastasis). The weighted sum reflects the overall severity of disease burden, with higher scores indicating worse health condition and greater morbidity. The use of ICD-10 codes for calculating CCI has been validated in previous research [

30,

31,

32], Based on the guideline from the NHIS, Quan’s method for calculating participant CCI score was utilized [

33] and scores were further classified into three categories: “0” (none), “1” (mild-to-moderate condition), and “2 or above” (severe condition).

Behavioral and metabolic variables such as smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, and body-mass index based on previous research showing the association of such factors with IBS [

34,

35] and/or depression were considered [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Standardized self-reported questionnaires were used to measure cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. To measure smoking behavior, participants were queried on their smoking routines in a two-stage question: (a) first question asking about smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, and current smoker), followed with (b) second question pertaining to the duration and amount of smoking for those who responded as former or current smokers. The information was collapsed into two categories: “current smoker” and “former/never smoker” [

25].

Alcohol consumption was measured with two questions asking for (a) the average number of days that individuals engage in alcohol drinking per week and (b) the average number of cups that the individual consume when drinking [

40,

41]. Based on this information, alcohol use behaviors were classified into two categories: “current drinker” (at least one drinking occasion weekly) and “former/never drinker” (no drinking occasion currently).

Regarding physical activity, participants were asked about the number of days in a week that they engaged in (a) vigorous physical exercise for more than 20 minutes (e.g., running, cycling) or (b) moderate level physical exercise for more than 30 minutes (e.g., jogging) over the past week. Participants who reported engaging in at least once on any type of priori-mentioned physical exercise were considered as “physically active” (having a regular vigorous-to-moderate physical activity), whereas those who reported no days of either type of physical activity were considered as “physically inactive” (not having a regular vigorous-to-moderate physical activity) [

42,

43].

Anthropometric assessment was conducted during the biennial health-screening check-up assisted by the trained staff. Body-mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight in kilogram divided by the square of height in meter. According to the guideline by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, we used 25kg/m2 as a cut-off point to define obesity [

44]. Since BMI class is considered as a covariate, rather than the primary focus of our analysis, we used 20kg/m2 as another cut-off value to group the BMI status, resulting in “less than 20kg/m2” (lower BMI group: 10.8% of the sample), “20kg/m2 to 25kg/m2,” (middle range BMI group: 50.0%), and “25kg/m2 or above” (higher BMI group: 39.1%).

2.3. Analyses

First, the distribution of the sociodemographic, medical, and behavioral characteristics of the study participants (a total of 3,864,586 individuals aged 19-64 years who went through the biennial health-screening exam in 2021) were examined (e.g., mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and proportion for binary/categorical variables).

Additionally, the 1-year prevalence of depression across the presence or absence of IBS diagnosis in 2021 was established, and a chi-squared test examined potentially differential distribution across the two-by-two contingency table for those variables. To evaluate the extent to which this health-screening subset represents the entire population in the 2021 NHIS dataset, we further performed sensitivity analyses among the full eligible sample (N=9,692,841) examining the prevalence of depression by IBS status, regardless of the health-screening exam status of the year.

Then, to determine the cross-sectional association between IBS and depression, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed with diagnosis of depression as a dependent variable and diagnosis of IBS as a primary exposure variable. To address potential confounding, covariates such as age (in years), gender, residential area (rural vs. urban), CCI category (none, 1, 2 or more), smoking status (active smoker vs. inactive smoker), alcohol drinking status (active drinker vs. inactive drinker), physical activity (physically active vs. inactive status), and BMI class were included. For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was set as 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic, medical, and behavioral characteristics of the study sample (N=3,864,586). Depression diagnosis was more prevalent in women (vs. men), and among those who: were older, lived in rural area (vs. urban), displayed more comorbid conditions, did not engage in smoking (vs. active smoking), did not use alcohol (vs. active alcohol users), and displayed a low BMI (i.e., <20kg/m2).

This pattern remained generally consistent when performing sensitivity analysis using a full eligible sample regardless of health-screening participation (N=9,692,841), which showed greater prevalence of depression diagnosis among women (vs. men) and those who were older, lived in rural area (vs. urban), displayed more comorbid conditions (

Table S1).

3.2. Prevalence of Depression and IBS

Table 2 shows the 1-year prevalence of depression and IBS in the study sample (N=3,864,586). Overall, 4.0% of the study participants were diagnosed with depression and 10.4% with IBS at some point in 2021. However, the 1-year prevalence of depression among individuals with IBS was 7.3%, which was nearly two times that among those without IBS (3.6%; p-value<0.001).

The sensitivity analysis with a full eligible sample regardless of health-screening participation (N=9,692,841) showed generally similar results with a 7.5% of prevalence for IBS and 4.3% for depression among the full sample, and 8.5% for depression among those with IBS versus 4.0% for depression among those without IBS (

Table S2).

3.3. IBS-Depression Association

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis among 3,864,586 study participants who went through the health-screening process in 2021. Most of all, there was a significant positive association between IBS and depression (OR 1.77, 95% CI: 1.74, 1.79), after adjusting for demographic (e.g., age, gender, and residential area), medical (e.g., CCI), and behavioral characteristics (e.g., smoking, drinking, physical activity, and BMI). That is, individuals who were diagnosed with IBS were 77% more likely to have a depression diagnosis in the same year, compared to their counterparts without IBS.

Additionally, demographic factors such as women (vs. men), and living in rural areas (vs. urban) were found to be associated with higher likelihood of having a depression diagnosis, independently of all other covariables. Among behavioral and medical factors, having more comorbid conditions and being an active smoker (vs. former or non-smoker) were associated with higher likelihood of being diagnosed with depression at some point in the same year, after adjusting for all covariables.

Our sensitivity analysis based on a full eligible sample regardless of health-screening participation (N=9,692,841) presented largely consistent results. Compared to those with no diagnosis of IBS, individuals with diagnosis of IBS in 2021 were more likely to be diagnosed with depression in the same year (OR 1.82, 95% CI: 1.81, 1.84), after adjusting for age, gender, residual area, and health condition (i.e., CCI). Similarly, being women (vs. men), living in rural area (vs. urban), and having more comorbid conditions were associated with higher likelihood of being diagnosed with depression, after adjusting for all covariates (

Table S3).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the cross-sectional association between IBS and depression among 3.9 million Koreans aged 19-65 using a health-screening subset of the 2021 Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database. The one-year prevalence of depression among Koreans with IBS was 7.3%, nearly twice that in those without IBS (3.6%). This pattern remained statistically significant (OR=1.77, 95% CI: 1.74-1.79), even after adjusting for sociodemographic (e.g., age, sex, residential area), behavioral (e.g., smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity), and medical conditions (e.g., comorbidity index and BMI class).

Our findings are generally in line with prior research, which has evidenced higher prevalences of psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety among individuals with IBS [

10,

16,

17,

18]. Our study builds incrementally on this by extending preliminary findings among Korean individuals [

19,

20], and providing the first methodologically rigorous test of these associations in a nationally representative sample.

Despite these similar patterns, it should be noted that compared to those previous international and domestic findings, the prevalence of depression reported in our study was relatively low with 7.3% among those with IBS and 3.6% among those without IBS. The 1-year prevalence of depression assessed with a standardized clinician administered diagnostic interview among Koreans was 1.7% (men 1.1% and women 2.4%) in a nationally representative sample of 5,511 Koreans aged 18-79 years [

45].

The discrepancy between the registry-based and community-based statistics in 1-year prevalence of depression (3.6% vs. 1.7%) may be due to the different natures of the database: (a) claim-based database whereby diagnostic/administrative errors or billing-purpose depression coding are common and (b) structured interview whereby social desirability bias or fear of the stigma can affect the responses when conducting person-to-person interview [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

Moreover, the prevalences of depression in Western populations has been reported to be generally higher than those in Asian populations [

50,

51], which may partly explain relatively smaller effect sizes found in our analysis compared to those from previous Western studies. Prior literature has pointed to the potential role of social stigma attached to mental healthcare utilization, lack of awareness of depression, and cultural differences in narratives and expressions pertaining to psychological distress in shaping such discrepancy in depression prevalences across different cultural contexts [

52,

53,

54,

55].

The findings from our study present important implications. First, the prevalence of comorbid IBS and depression provide support for the explanatory frameworks that emphasize the role of neuroendocrine factors in the etiology of both of these disorders [

10,

11,

12] and the usefulness of pursuing research into the development of mental and physical health concerns from this perspective. Indeed, other work has also highlighted the comorbidity of IBS and anxiety-based disorders including panic disorders [

56,

57]. Additional work exploring these gut-brain relationships would be informative. In particular, research focused on understanding the biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors that may predispose, precipitate, and maintain the core elements of both IBS and depressive and anxiety disorders would be useful. Moreover, as noted previously, much of the research in this area is cross-sectional, and rigorously designed studies capable of examining the directionality of the underlying relationships between these disorders would be helpful. Such studies may involve methodologies such as Ecological Momentary Assessment or daily diaries to help capture the sequencing and frequency of physical and emotional experiences among individuals with comorbid IBS and depression [

58,

59].

In terms of clinical implications, these comorbidities highlight the potential for integrated and holistic interventions for individuals with IBS and comorbid depression. Psychological treatments for IBS grounded in cognitive behavioral frameworks have previously been shown to be successful in the treatment of IBS with a focus on cognitive reframing, emotional regulation, and mindfulness techniques [

60]. Given the centrality of these same skills in most psychological treatments for depression [

61], it is likely that treatments that target the psychological and physiological manifestations of IBS and depression within unified approaches would have a high potential for success. Current first line treatments for IBS include psychoeducation, however, the provision of cognitive and emotional skills is not yet common in clinical practice [

62].

However, the findings of our study should be interpreted in consideration of several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow to disentangle the temporality between key variables and thus limit causal inference, particularly susceptible to reverse causation. Given the evidence suggesting bi-directionality of the IBS-depression relationship [

63,

64], further investigations with prospective study designs are needed. Second, our study did not examine any potential interactions by IBS-subtype, sociodemographic or health-related behaviors. While our analysis provides nationally representative estimates of the association, future research should elucidate potential sources of heterogeneity across biological, clinical and behavioral dimensions.

Nonetheless, our study has several strengths as follows. First, we used a nationally representative sample of 3.9 million Koreans based on the NHIS database to improve the extent of the representativeness of our analysis, thereby providing a sufficient level of external validity of the findings to Korean populations. Second, the claims-based nature of the NHIS database enabled to utilize physician-driven diagnostic decision information on core variables, providing a more robust research context of investigation of IBS-depression association, pertaining to the validity of the measure, compared to the use of screeners. Third, since we used a health-screening subset of the 2021 NHIS database, we were able to obtain information on behavioral characteristics as well as sociodemographic and medical conditions of the participants and adjust for those factors in our multivariable logistic regression model. Thus, the observed IBS-depression connection in our analysis goes beyond the potential confounding or mediating role of such factors.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we found in a large nationally representative sample of Korean that IBS was associated with a 77% increased risk for having depression in the same year, after controlling for sociodemographic, behavioral, and other medical conditions. Our findings warrant the needs for integrated approaches to prevent and address the growing psychiatric burden that individuals living with IBS suffer from. More specifically, public health policies that encourage and support timely screening for depression and referral to psychiatric or psychological specialists, when necessary, in clinical practice should be considered [

65]. Last but not least, further studies that can more precisely disentangle subgroups that lie in greater risks would be warranted.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Characteristics of the full eligible individuals aged 19-64 years from the 2021 NHIS database (N=9,692,841), regardless of their participation in health-screening exams; Table S2: One-year prevalence of depression among the full eligible individuals aged 19-64 years from the 2021 NHIS database (N=9,692,841), regardless of the health-screening participation status; Table S3: Cross-sectional multivariable logistic regression model analyzing the association between irritable bowel syndrome and depression among the full eligible individuals aged 19-64 years from the 2021 NHIS (N=9,692,841), regardless of the health-screening participation status.

Author Contributions

Y.K.: Writing- original draft preparation, Writing- review & editing; D.K.: Methodology, Formal analysis; H.J.: Formal analysis; E.A.: Formal analysis; R.F.R.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing; E.B.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing; G.L.: Conceptualization, Investigation; J.H.K.: Conceptualization, Investigation; Y.H.M.: Conceptualization, Investigation; K.O.K.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation; T.K.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing; M.H.L.: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and the Ministry of Science and ICT, grant number 2022R1A5A2029546, given to Mee-Hyun Lee.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Dongshin University (IRB number 1040708-202212-SB-045 and date of approval of April 27th, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the study used de-identified, anonymized secondary data provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), and no personal identifiers were accessed.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS:

http://nhiss.nhis.or.kr). Access to the data for this study was granted under an NHIS license (NHIS-2024-1-500) and is therefore not publicly available. Researchers may apply for access by submitting a data request application to the NHIS, meeting the eligibility criteria, obtaining approval from the NHIS review committees, and paying the required data access fees.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Dongshin University College of Korean Medicine, the Korean Medicine Research Center for Bi-Wi Control Based Gut-Brain System Regulation, and Dongshin University Gwangju and Mokpo Hospitals for their administrative and technical support during this study. The authors also acknowledge the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) for providing access to the anonymized health data used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBS |

irritable bowel syndrome |

| NHIS |

National Health Insurance Service |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| HPA |

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| BMI |

body-mass index |

| OR |

odds ratio |

| CI |

confidence interval |

References

- Almario CV, Sharabi E, Chey WD, Lauzon M, Higgins CS and Spiegel BMR. Prevalence and Burden of Illness of Rome IV Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the United States: Results From a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1475–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman DA and Tack, J. Rome Foundation Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, Sperber AD and Simren M. Prevalence of Rome IV Functional Bowel Disorders Among Adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1262–1273.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel Disorders. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016.

- Black CJ and Ford, AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, Black CJ, Savarino EV and Ford AC. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 5, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monden R, Rosmalen JGM, Wardenaar KJ and Creed F. Predictors of new onsets of irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: the lifelines study. Psychol Med 2022, 52, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norlin AK, Walter S, Icenhour A, Keita Å V, Elsenbruch S, Bednarska O, et al. Fatigue in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with plasma levels of TNF-α and mesocorticolimbic connectivity. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 92, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo YJ, Ho CH, Chen SC, Yang SS, Chiu HM and Huang KH. Lower urinary tract symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Urol 2010, 17, 175–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiha MG and Aziz, I. Review article: Physical and psychological comorbidities associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021, 54 (Suppl. 1), S12–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmes L, Collins JM, O'Riordan KJ, O'Mahony SM, Cryan JF and Clarke G. Of bowels, brain and behavior: A role for the gut microbiota in psychiatric comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021, 33, e14095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillestad EMR, van der Meeren A, Nagaraja BH, Bjorsvik BR, Haleem N, Benitez-Paez A, et al. Gut bless you: The microbiota-gut-brain axis in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2022, 28, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh M, Mokhtare M, Moayyedi P, Black CJ and Ford AC. Efficacy of gut-brain neuromodulators in irritable bowel syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025.

- Zhou C, Fang X, Xu J, Gao J, Zhang L, Zhao J, et al. Bifidobacterium longum alleviates irritable bowel syndrome-related visceral hypersensitivity and microbiota dysbiosis via Paneth cell regulation. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1782156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labus JS, Osadchiy V, Hsiao EY, Tap J, Derrien M, Gupta A, et al. Evidence for an association of gut microbial Clostridia with brain functional connectivity and gastrointestinal sensorimotor function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, based on tripartite network analysis. Microbiome 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S and Zamani V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019, 50, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, Boukouaci W, Dargel A, Oliveira J, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014, 264, 651–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudyanadzo TA, Hauzaree C, Yerokhina O, Architha NN and Ashqar HM. Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Depression: A Shared Pathogenesis. Cureus 2018, 10, e3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho HS, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Lee IS, Kim SW, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver 2011, 5, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim O, Cha C, Jeong H, Cho M and Kim B. Influence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome on Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Nurses: The Korea Nurses' Health Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18.

- Lim SJ and Jang, SI. Leveraging National Health Insurance Service Data for Public Health Research in Korea: Structure, Applications, and Future Directions. J Korean Med Sci 2025, 40, e111. [Google Scholar]

- Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, Heon Park J, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data Resource Profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 2017, 46, 799–800. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JE, Yoon DH, Jin EH, Han K, Choi SY, Choi SH, et al. Association between depression and young-onset dementia in middle-aged women. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon KH, Han K, Jung J, Park CI, Eun Y, Shin DW, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Risk of Depression in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e241139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim GE, Kim MH, Lim WJ and Kim SI. The effects of smoking habit change on the risk of depression-Analysis of data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service. J Affect Disord 2022, 302, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo YW, Min JH, Kwon JW and Her Y. Rosacea and Its Potential Role in the Development of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Insights From the Korean National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort. J Korean Med Sci 2025, 40, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak N, Lee H, Kim BK, Yu YM and Kang HY. Association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and developing irritable bowel syndrome through retrospective analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 39, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Cho Y, Oh J, Kang H, Lim TH, Ko BS, et al. Analysis of Anxiety or Depression and Long-term Mortality Among Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e237809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL and MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987, 40, 373–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasheen WP, Cordier T, Gumpina R, Haugh G, Davis J and Renda A. Charlson Comorbidity Index: ICD-9 Update and ICD-10 Translation. Am Health Drug Benefits 2019, 12, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Toson B, Harvey LA and Close JC. The ICD-10 Charlson Comorbidity Index predicted mortality but not resource utilization following hip fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 2015, 68, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melfi C, Holleman E, Arthur D and Katz B. Selecting a patient characteristics index for the prediction of medical outcomes using administrative claims data. J Clin Epidemiol 1995, 48, 917–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005, 43, 1130–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirri L, Grandi S and Tossani E. Smoking in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J Dual Diagn 2017, 13, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh N, Ghobaklou M, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Naderi N and Fadai F. Effects of demographic factors, body mass index, alcohol drinking and smoking habits on irritable bowel syndrome: a case control study. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013, 3, 391–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, EV. Alcohol and the Etiology of Depression. Am J Psychiatry 2023, 180, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM and Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 107, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou V, Casanova F, O'Loughlin J, Green H, McKinley TJ, Bowden J, et al. Body mass index and inflammation in depression and treatment-resistant depression: a Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med 2023, 21, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M and Munafo MR. The Association of Cigarette Smoking With Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Nicotine Tob Res 2017, 19, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang DO, Lee DI, Roh SY, Na JO, Choi CU, Kim JW, et al. Reduced Alcohol Consumption and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Among Individuals With Previously High Alcohol Consumption. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e244013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo JE, Han K, Shin DW, Kim D, Kim BS, Chun S, et al. Association Between Changes in Alcohol Consumption and Cancer Risk. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2228544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Han K, Jung JH, Ha J, Jeong C, Heu JY, et al. Physical activity and reduced risk of fracture in thyroid cancer patients after thyroidectomy - a nationwide cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1173781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi D, Choi S, Kim KH, Kim K, Chang J, Kim SM, et al. Combined Associations of Physical Activity and Particulate Matter With Subsequent Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among 5-Year Cancer Survivors. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e022806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim KK, Haam JH, Kim BT, Kim EM, Park JH, Rhee SY, et al. Evaluation and Treatment of Obesity and Its Comorbidities: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J Obes Metab Syndr 2023, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim SJ, Hahm BJ, Seong SJ, Park JE, Chang SM, Kim BS, et al. Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Associated Factors in Korean Adults: National Mental Health Survey of Korea 2021. Psychiatry Investig 2023, 20, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo M, Rim SJ, Lee MG and Park S. Illuminating the treatment gap of mental disorders: A comparison of community survey-based and national registry-based prevalence rates in Korea. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 130, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Jain S, Bertenthal D and Glassman P. Assessing the accuracy of administrative data in health information systems. Med Care 2004, 42, 1066–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis KA, Sudlow CL and Hotopf M. Can mental health diagnoses in administrative data be used for research? A systematic review of the accuracy of routinely collected diagnoses. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang S, Jayadevappa R, Zee J, Zivin K, Bogner HR, Raue PJ, et al. Concordance Between Clinical Diagnosis and Medicare Claims of Depression Among Older Primary Care Patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015, 23, 726–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler RC and Bromet, EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health 2013, 34, 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, de Girolamo G, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med 2011, 9, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Choi E, Chentsova-Dutton Y and Parrott WG. The Effectiveness of Somatization in Communicating Distress in Korean and American Cultural Contexts. Front Psychol 2016, 7, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Lauber C and Rossler, W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2007, 19, 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder AG, Yang J, Zhu X, Yao S, Yi J, Heine SJ, et al. The cultural shaping of depression: somatic symptoms in China, psychological symptoms in North America? J Abnorm Psychol 2008, 117, 300–313.

- Parker G, Gladstone G and Chee KT. Depression in the planet's largest ethnic group: the Chinese. Am J Psychiatry 2001, 158, 857–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugaya N, Kaiya H, Kumano H and Nomura S. Relationship between subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome and severity of symptoms associated with panic disorder. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008, 43, 675–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, JR. Are some irritable bowel syndromes actually panic disorders? Postgrad Med 1988, 83, 206–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA and Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoevers RA, van Borkulo CD, Lamers F, Servaas MN, Bastiaansen JA, Beekman ATF, et al. Affect fluctuations examined with ecological momentary assessment in patients with current or remitted depression and anxiety disorders. Psychol Med 2021, 51, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya N, Shirotsuki K and Nakao M. Cognitive behavioral treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: a recent literature review. Biopsychosoc Med 2021, 15, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Mignogna J, Underhill C and Cully JA. The relationship between use of CBT skills and depression treatment outcome: a theoretical and methodological review of the literature. Behav Ther 2013, 44, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Workman P, Windgassen S and Moss-Morris R. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychol Med 2016, 46, 3065–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova VL, Pelton L, Moulton CD, Zorzato D, Cleare AJ, Young AH, et al. The Prevalence and Incidence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Depression and Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med 2022, 84, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasant DH, Paine PA, Black CJ, Houghton LA, Everitt HA, Corsetti M, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2021, 70, 1214–1240.Author. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).