1. Introduction

Irritable bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterised by abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation or a combination of both diarrhoea and constipation, mucus discharge, and changes in stool form [

1]. These symptoms are common in the general population, affecting people of all ages and genders [

2]. Diagnosis is made by Rome IV criteria published in May 2016, serving as the current gold standard, due to the absence of well-validated biomarkers. This set of criteria prioritized the impact of cross-cultural differences, the intestinal milieu, and the role of nutrition over previous iterations [

3]. The Bristol stool form scale is used to classify abnormal bowel movements [

4].

The disorder amounts to a major burden on healthcare and constitutes nearly half of the referrals to gastroenterology clinics. The frequency and type of IBS symptoms vary depending on geographical location because of variations in bowel habits, cultural beliefs, gut contamination, dietary practices, and psychosocial reasons [

5].

The onset of IBS is more likely to occur after an infection (IBS-postinfectious), or a stressful life event, but varies little with age. The most common theory is that IBS is a disorder of the interaction between the brain and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For at least some individuals, abnormalities in the gut flora occur, and it has been theorized that these abnormalities result in inflammation and altered bowel function [

6].

The prevalence of IBS varies by geographic region and population, as well as the diagnostic criteria used [

7]. IBS affects 10–20% of the population according to cross-sectional studies done in Europe and North America. The global prevalence of IBS was reported to be 11.2% using Manning, Rome I, Rome II, or Rome III criteria [

7,

8]. In various Asian nations, the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) ranges from 4% to 20%. IBS prevalence in India is estimated at 4.0%-7.9% which continues to be on the rise [

5].

About 50–90% of IBS patients also have associated psychiatric ailments, most common anxiety disorders and depression. Studies have revealed that patients seeking medical consultation have a higher number and severity of symptoms and are more likely to be depressed and anxious [

9].

The health-related quality of life in patients with this functional GI disorder is impaired. Patients with serious conditions often have a higher rate of reduced quality of life [

10]. Studies have also shown that patients avoid or are unable to participate in a variety of activities due to IBS symptoms like work, leisure, and social activities [

10,

11].

Most of the literature on IBS and associated psychiatric diseases comes from western studies. Since major socio-cultural differences exist in the manifestation of these psychosomatic disorders, generalizing the outcomes of research from western studies will be unrevealing. Only a few studies have been done in this area so far in India. Our aim, therefore, was to strengthen the limited knowledge regarding the sociodemographic and clinical correlates including psychiatric disorders with IBS in our region.

2. Material and Methodology

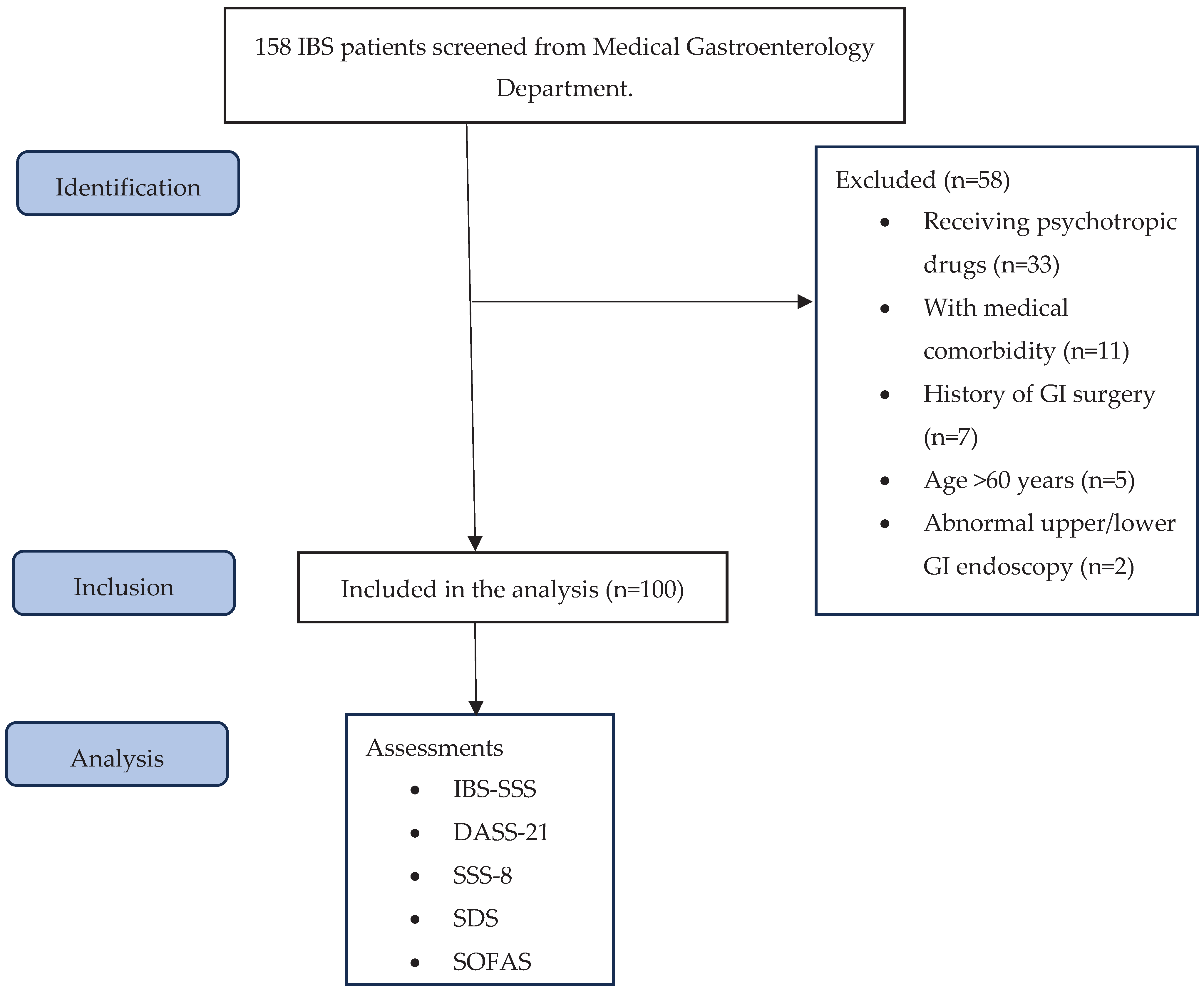

The present study was conducted at a tertiary care centre in north India. It was a cross-sectional study conducted for a length of about one and a half years from June 2021 to September 2022. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee with Ref. code II PGTSC-IIA/P10. Subjects for the study were selected from outpatients visiting the medical gastroenterology department. 158 patients were screened and 100 were enrolled in the study. All the cases were interviewed for sociodemographic parameters like gender, age, marital status, employment, and education level. The assessments were conducted by a trainee psychiatric resident under supervision of a consultant medical gastroenterologist and a consultant psychiatrist. All the patients provided written informed consent for inclusion in the study.

Subjects aged 18 or above who satisfied the diagnostic criteria for IBS (Rome IV criteria) and had no medical comorbidities or organic pathology (abnormal upper and lower GI endoscopy) and who were not receiving any psychotropic medications were included in the study.

Cases were diagnosed using Rome IV criteria, a self-reported integrated questionnaire for diagnosis of all functional gastrointestinal disorders in adults [

12]. The severity of symptoms was assessed using Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS). It is a 5-question based survey that asks the severity of abdominal pain, frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distention, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference with quality of life over the past 10 days. Subjects respond to each question on a 100-point visual analogue scale [

13]. Subjects were screened for any psychiatric comorbidity while interviewing and the diagnosis was confirmed by DSM-5[

14]. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items (DASS-21) was applied to assess for depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms. It is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress [

15]. Somatic Symptom Scale–8 (SSS-8) was used to assess for somatic symptoms. It is a brief self-report questionnaire used to assess somatic symptom burden. The scale assesses common somatic symptoms and is a shortened version of the PHQ-15 questionnaire scale [

16]. Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was used to check functional impairment. It is a brief, 3-item self-report tool that assesses functional impairment in work/school, social life, and family life [

17]. Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) was applied for social and occupational functioning assessment. It focuses exclusively on the individual's level of social and occupational functioning and is not directly influenced by the overall severity of the individual's psychological symptoms [

18].

Figure 1 describes the describes our research process, criteria for enrollment and the subjects eventually included in the study.

4. Result

A total of 158 subjects were screened and 100 subjects were enrolled in study. The most common reason for the exclusion was that they were already receiving psychotropic medications (n=33), followed by subjects with medical comorbidities like diabetes/ chronic kidney disease (n=11), history of gastrointestinal surgery (n=7), age >60 years (n=5) and subjects with abnormal upper or lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (n=2) were other reasons. Sociodemographic profile of subjects is provided in

Table 1. The mean years of age of onset of our IBS patients was 30.46 years (SD = ±9.05) and mean duration of illness was 5.07 years (SD = ±5.89).

As per IBS symptom severity scale, most of the subjects were in moderate category (61.0%) and the mean score was 280.20 (SD = ±57.21). Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms were assessed using DASS-2. In depression 53.0% were in moderate category with mean score of 16.16±5.31, 43.0% were having moderate anxiety with mean score of 13.80 ±4.76. In stress 36.0% were having moderate stress with mean score of 18.53±6.91. Somatic symptoms were evaluated according to somatic symptom scale-8. 12% cases were in high category score followed by 35.0% in medium and 28.0% in low with mean score of 11.50±3.05. Functional impairment in the sample was assessed as per Sheehan disability scale. 30% of subjects had impairment in work/school with a mean score of 4.73±1.70. 38% of subjects had impairment in social life with a mean score of 4.87±1.65, while 51 % had impairment in family life/ home responsibility with a mean score of 5.61±1.59. Social and occupational functioning in the sample as per SOFAS Score was analysed. 31% had some difficulty in social, occupational, or school functioning while 3% had superior functioning.

Psychiatric comorbidities present in study are listed in

Table 2. In our study, psychiatric disorders were seen in 29% of patients. Major psychiatric disorder seen was depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, conversion disorder with mixed symptoms, somatic symptom disorder, and substance use disorder were another disorder present.

Pearson correlation was applied to analyze the association between IBS severity score and clinical variables. IBS-SSS was significantly associated and positively corelated with age of onset (r = 0.209, p = 0.037), DASS 21 (depression) (r = 0.545, p = <0.001), DASS 21 (Anxiety) (r = 0.212, p = <0.001), Somatic symptoms scale (r = 0.458, p = <0.001), SDS (r = 0.643, p = <0.001) and negatively corelated with SOFAS (r = -0.690, p = <0.001).

5. Discussion

The present study is a cross-sectional observational study carried out in Northern India. It was conducted with aim to study sociodemographic and clinical variables including psychiatric comorbidities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome presenting to medical gastroenterology OPD of a tertiary care hospital. The diagnosis was confirmed by ROME IV criteria. The exclusion criteria screened out patients having comorbid medical illness including diabetes and chronic kidney disease as these might alter gastrointestinal functioning. Subjects with pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders other than functional gastrointestinal syndromes, subjects with a history of gastrointestinal surgery or abnormal upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy were excluded to minimise chances of any organicity. Subjects already receiving psychotropic medications were also excluded as it might affect the severity of IBS and can affect depressive, anxiety, stress, somatic symptoms and impairment and social and occupational functioning.

The study group comprised 100 patients out of which 38% were aged between 18 and 30 years. Mean age of the cases was 35.66±11.30 years. Hence, clinical population of IBS was in middle age as in our study. In our study males were in 62.0% and females were 38.0%. These findings were supported by a multicentric study done by Khanna et al., who reported in their study that mean age of the study population was 38.55 years, and majority of patients were men 68%. In all, 40% of patients were in the age group of 31-45 years [

20]. A multi-centric study done by Ghosal et al., reported mean age of sample as 39.4 years and male preponderance of 68% [

5].

Although western studies[

21] have reported higher rates of IBS in women, Asian findings have higher rates of IBS in males, which could be due to easy and better access to health care services, cultural factors favouring men in a male dominant society. The reason for altered rates are unidentified and could be an area for future research.

In the present study 45.0% of the cases were living in semi-urban area followed by 34.0% in urban area. The observations from community studies in South Asia (India, Bangladesh and Malaysia) appear indicates that IBS is more common in urban as compared to rural populations [

1]. An urban lifestyle is reported to be associated with greater psychological stress, and other causative risk factors like dietary factors and sedentary lifestyle and thus may be associated with a higher prevalence of IBS compared to rural living.

There were 71.0% patients who were married & 29.0% were unmarried. Most were living in nuclear family i.e., 72.0%. On the context of education level 51.0% were graduate & above 13.0% were completed 12

th standard, 12.0% were illiterate. Employment status as per Modified Kuppuswamy Scale-2017 was documented which revealed 25.0% of the cases were unemployed whereas 24.0% were housewife & Clerk, Shop owner, farmer. In context of income present study observed 46.0% were having no income and 31.0% were earning greater than Rs.25000. Family income was more than Rs.25000 in 61.0 %. Khanna et al., in their study reported a large proportion of enrolled patients (46.0%) were graduates or postgraduates [

20].

In the present study 46.0% of the cases had onset of illness in age group 18-29 years followed by 33.0% in 30-39 years of age, 40.0% of the cases had duration of years between 1-3 years while 25.0% had illness greater than 6 years. Long term naturalistic follow study, which imply chronicity of symptoms, contradict the evidence of lower prevalence of IBS in older age groups, which suggests that symptoms resolve over time [

6].

In current study IBS severity was measured using IBS-SSS. Most of the patients i.e., 62% were in moderate category while 32% were in severe category. The patients often take treatment when their symptoms are reasonably serious. As the study was conducted in a tertiary care centre, hence higher severity in subjects. The mean score was 280.20. A study done by Lackner et al., reported mean total IBS-SSS score of 284 for the sample was in high-moderate level of symptom severity in IBS-SSS, which is similar to this study [

22].

Using DASS-21 depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms were assessed. In depression, 53.0% were in moderate category followed by 20.0% in mild, 43.0% were having moderate anxiety & 33.0% had severe anxiety. In stress 36% were having moderate stress while 28.0% were having mild stress. Alaqeel et al., reported that DASS-21 results in their study revealed that 39.0%, 7.0%, and 25.9% of students had normal, mild, and moderate anxiety, respectively [

23]. A prior study in Japan by Okami et al., reported that individuals with IBS had higher scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) than control subjects in medical students [

24].

In the present study SSS-8 was used to evaluate the somatic symptoms. 48% cases were in high category score followed by 31% in medium and 12% in low. A reason could be that people from developing countries report more somatic symptoms in comparison with developed countries [

25]. In addition, over one-half of all patients with IBS report depression or anxiety and these patients experience more severe somatic symptoms [

26]. It is important that IBS patients are evaluated for other somatic symptoms like pain, fatigue, shortness of breath apart from GI symptoms as they have somatic stress in other parts and should be taken into consideration.

This study evaluated functional impairment and social and occupational functioning using SDS and SOFAS. 30% of subjects had impairment in work/school, 38% of subjects had impairment in social life, while 51 % had impairment in family life/ home responsibility. 31% had some difficulty in social, occupational or school functioning. We were not able to find much data regarding functional impairment and social and occupational functioning, although a study reported a high degree of impairment due to IBS, with 76% of the sample reporting some degree of IBS-related impairment in at least five different domains of daily life [

27]. Moreover, other studies have reported significantly poorer quality of life and more absenteeism in work in patients with IBS which corroborates with our findings of impairment in work, social life and family responsibilities and difficulty in social, occupational or school functioning [

11].

In the present study comorbidity was evaluated by clinical interview and diagnosis was made by DSM-5

. Diagnosable psychiatric comorbidity was present in 29% of sample, although psychiatric symptoms were present in significant number of subjects. The frequency and severity of the symptomatology of IBS in patients with anxiety and mood disorders have been well documented [

9,

28]. Most of the patients had depressive disorder (14%). Association of comorbidity with SSS-8 Score was significant

. Most of the patients were having high points in both with and without comorbidity i.e., 62.1% & 42.3% respectively. Cho et al., stated stress, worry, or sadness are often associated with IBS, in an integrated biopsychosocial approach, psychiatric co-morbidity contributes to the aetiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [

29].

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in clinical IBS patients is depression, followed by anxiety and somatization disorders which is similar to our study findings [

28]. Another reason for these findings could be that the cases selected in our study were selected from a tertiary care centre where more severe forms of the illness are seen, and it has been studied that the severity of functional GI disorders increases the likelihood of having co-morbid psychiatric disorders.

In the present study correlation of IBS-SSS with clinical variables was evaluated. IBS-SSS was significantly correlated with all the scoring scales such as DASS-21, SSS- 8, SDS and SOFAS. A study done by Cho et al., reported that among the patients with severe symptoms, anxiety and depression were related to the abdominal pain or discomfort score, although the association with anxiety was not significant [

29].

Our study had a few limitations. We selected our sample from clinical population visiting medical gastroenterology OPD, hence it could not be generalizable to other population. Further, patients were not categorized in IBS subtypes which could have effect on disease severity and associated psychiatric comorbidities. No fresh investigations were done at baseline due to lack of feasibility, although patients had investigations from past. Another limitation of our study was that we didn’t study dietary habits of our sample which could influence IBS presentation.