Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting, Population, and Design

2.2. Blood and Urinary Metal Measurements

2.3. DNA Extraction for Telomere Length Measurement

2.4. Telomere Length Measurement

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Blood Metal Levels for the Study Population

3.3. Urine Metal Levels Across Key Groups

| (a) | |||||||||

| Metal (µg/L) | E-waste workers (n=53) | Reference Population (n=25) | p value | Study Population (N=78) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | |||||||||

| Zn | 892.75 (1091.625) | 922.725(1168.9) | 0.7037 | 903.775 (1109.5) | |||||

| Pb | 5.125(4.7225) | 3.3225(2.08) | <0.0001 | 4.4125(4.1675) | |||||

| As | 36.885(37.295) | 60.255(64.455) | 0.0001 | 42.335(54.0875) | |||||

| Mg | 53520.45(55920.33) | 50240.18(55264.42) | 0.6300 | 53370.27(55920.33) | |||||

| Cr | 8.8375(5.4975) | 8.6425(7.09) | 0.8984 | 8.7075(6.0025) | |||||

| Ga | 1.12395(.0741) | 1.1747(.1338) | 0.0012 | 1.1384(.09465) | |||||

| Se | 26.2425(24.8075) | 34.8825(28.1975) | 0.0045 | 28.6075(26.065) | |||||

| Legend: IQR=interquartile range, N= Total number of participants, n = sub study population, p-value obtained using Mann Whitney U test, bold p-values are statistically significant. | |||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||

| Wave | Metal (µg/L) | Total (N=78) | |||||||

| E-waste workers (n=53) | Reference population (n=25) | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Difference | p-value | ||||||

| One | Zn | 976.8(5154.05) | 1333.35(690.75) | 356.55 | 0.717 | ||||

| Pb | 6.06(5.135) | 3.54(2.29) | 2.52 | 0.024 | |||||

| As | 37.05(45.93) | 61.06(67.28) | 24.01 | 0.078 | |||||

| Mg | 66910.15(57534.95) | 76954.6(59855.86) | 10044.45 | 0.491 | |||||

| Cr | 8.495(5.38) | 8.1(1.78) | .395 | 0.706 | |||||

| Ga | 1.111(.0677) | 1.1755(.3526) | .0645 | 0.108 | |||||

| Se | 27.135(24.735) | 39.505(36.675) | 12.37 | 0.065 | |||||

| Two | Zn | 723.6(489.45) | 436.6(361.95) | 287 | 0.011 | ||||

| Pb | 4.175(3.505) | 2.465(2.305) | 1.71 | 0.034 | |||||

| As | 32.68(25.54) | 56.105(51.725) | 23.425 | 0.009 | |||||

| Mg | 64104.25(61577.71) | 44512.87(40590.24) | 19591.38 | 0.170 | |||||

| Cr | 8.17(3.28) | 6.965(4.89) | 1.205 | 0.214 | |||||

| Ga | 1.1639(.0696) | 1.1126(.1202) | .0513 | 0.022 | |||||

| Se | 24.12(15.85) | 28.81(23.995) | 4.69 | 0.330 | |||||

| Three | Zn | 1030.625(1702.6) | 1460.425(2662.1) | 431.65 | 0.378 | ||||

| Pb | 5.1625(3.92) | 4.055(1.565) | 1.2 | 0.157 | |||||

| As | 37.51(66.105) | 60.255(72.435) | 22.99 | 0.210 | |||||

| Mg | 44282.43(25635.85) | 43007.94(16955.61) | 1313.25 | 0.770 | |||||

| Cr | 12.1425(7.785) | 14.8825(8.67) | 2.945 | 0.170 | |||||

| Ga | 1.11275(.0492) | 1.2012(.0751) | .091 | <0.001 | |||||

| Se | 28.9525(30.54) | 37.175(41.215) | 9.905 | 0.282 | |||||

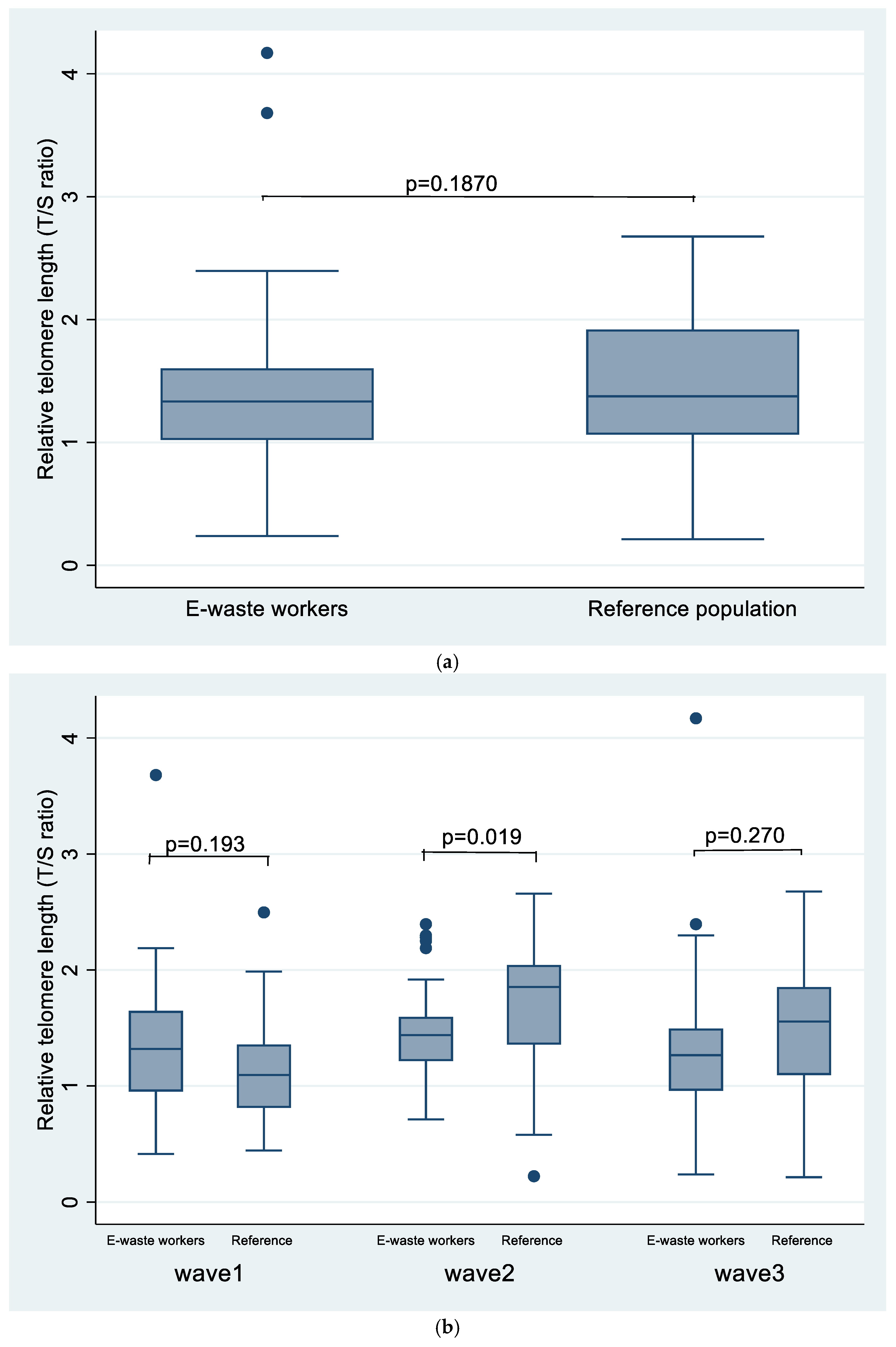

3.4. Relative Telomere Length for the Study Population

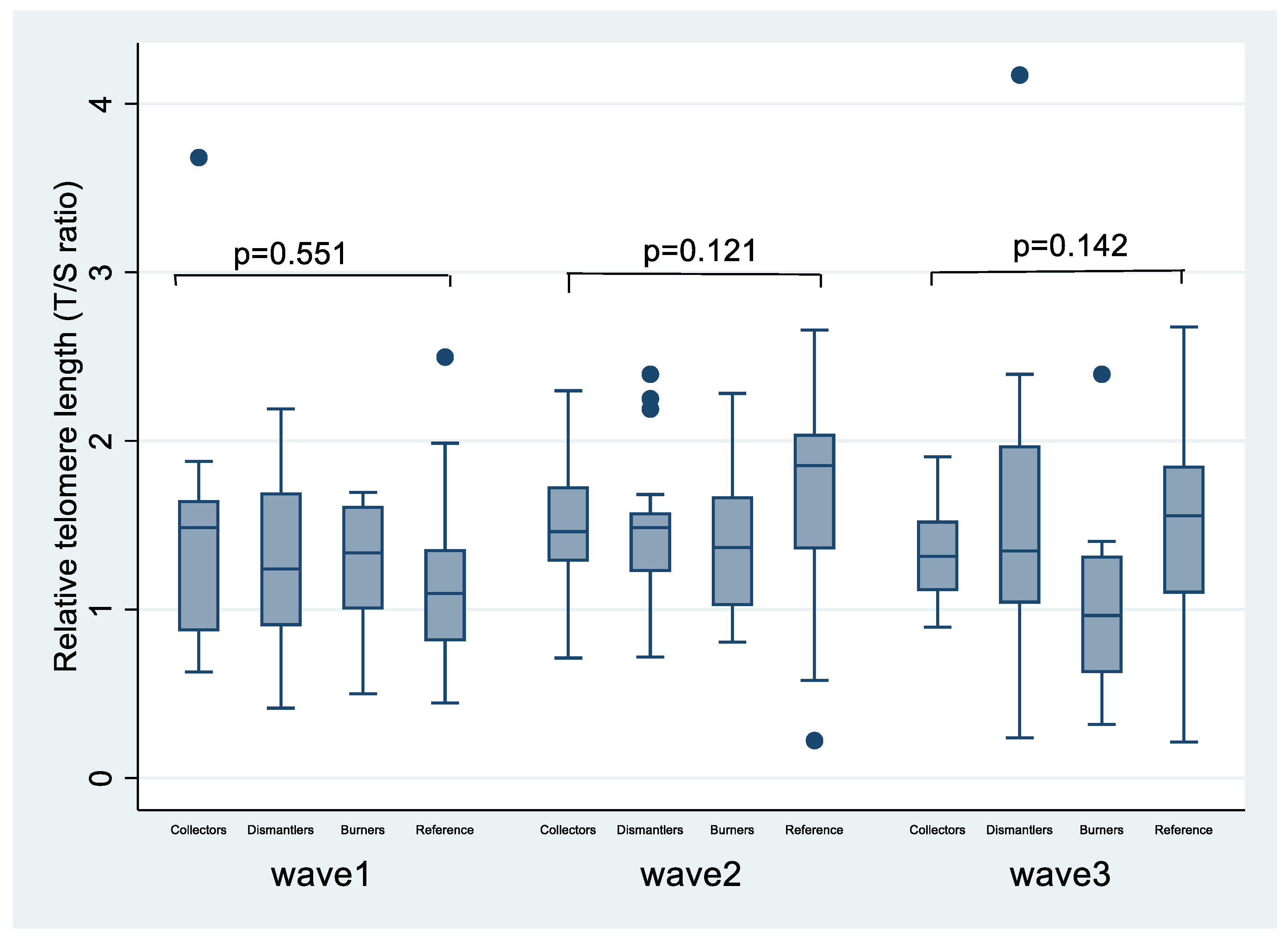

3.5. Relative Telomere Length Across Various Job Tasks

3.6. Relationship Between Relative Telomere Length and Anthropometric and Lifestyle Factors

| E-waste workers (n=53) | Reference Population (n=25) | ||

| Wave | (Mean±SD) | p value | |

| One | 1.318±0.560 | 1.170±0.467 | 0.308 |

| Two | 1.434±0.403 | 1.663±0.571 | 0.051 |

| Three | 1.323±0.673 | 1.504±0.722 | 0.283 |

| Average | 1.358±0.557 | 1.464±0.630 | 0.2104 |

| E-waste workers (n=53) | |||

| Wave | Job task | (Mean±SD) | p value |

| One | Burners | 1.263671±0.386 | 0.4149 |

| Dismantlers | 1.269781±0.501 | ||

| Collectors | 1.531398±0.868 | ||

| Two | Burners | 1.405573±0.424 | 0.9354 |

| Dismantlers | 1.436999±0.390 | ||

| Collectors | 1.467215±0.452 | ||

| Three | Burners | 1.027005±0.533 | 0.1387 |

| Dismantlers | 1.462417±0.786 | ||

| Collectors | 1.334806±0.299 | ||

| rTL | ||||

| Variable | Total (n=72) | E-waste workers (n=53) | Controls (n=19) | p-value |

|

Age (years) (n (%) ≤20 20-39 40+ |

9 (12.5) 57 (79.2) 6(8.3) P=0.4032 |

7(13.2) 44(83.0) 2(3.8) p= 0.4743 |

2(10.5) 13(68.4) 4(21.1) p= 0.1762 |

0.6819 0.0914 0.4649 |

|

Smoking Yes No |

15(20.8) 57(79.2) P= 0.5102 |

13(24.5) 40(75.5) p= 0.8177 |

2(10.5) 17(89.5) p= 0.0742 |

0.0883 0.5626 |

|

Alcohol intake Never Former Regular |

63 (87.5) 5 (6.9) 4 (5.6) P= 0.9645 |

45(85.0) 4(7.5) 4(7.5) p= 0.9445 |

18(94.7) 1(5.3) 0(0) p= 0.3122 |

0.4787 0.209 5 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) Low weight Normal weight Overweight Obesity |

9 (12.5) 50(69.4) 11(15.3) 2(2.8) P=0.206 |

6(11.3) 41(77.4) 6(11.3) 0(0.0) p = 0.20 |

3(15.8) 9(47.4) 5(26.3) 2(10.5) p=0.392 |

0.728 0.094 0.962 |

|

Indoor use of biomass Yes No |

15(20.8) 57(79.2) p=0.945 |

10(18.9) 43(81.1) p=0.844 |

5(26.3) 14(73.7) p=0.754 |

0.246 0.507 |

|

Job category Burners Dismantlers Collectors/sorters |

NA NA NA |

14(26.4) 29(54.7) 10(18.9) p= 0.4149 |

NA NA NA |

|

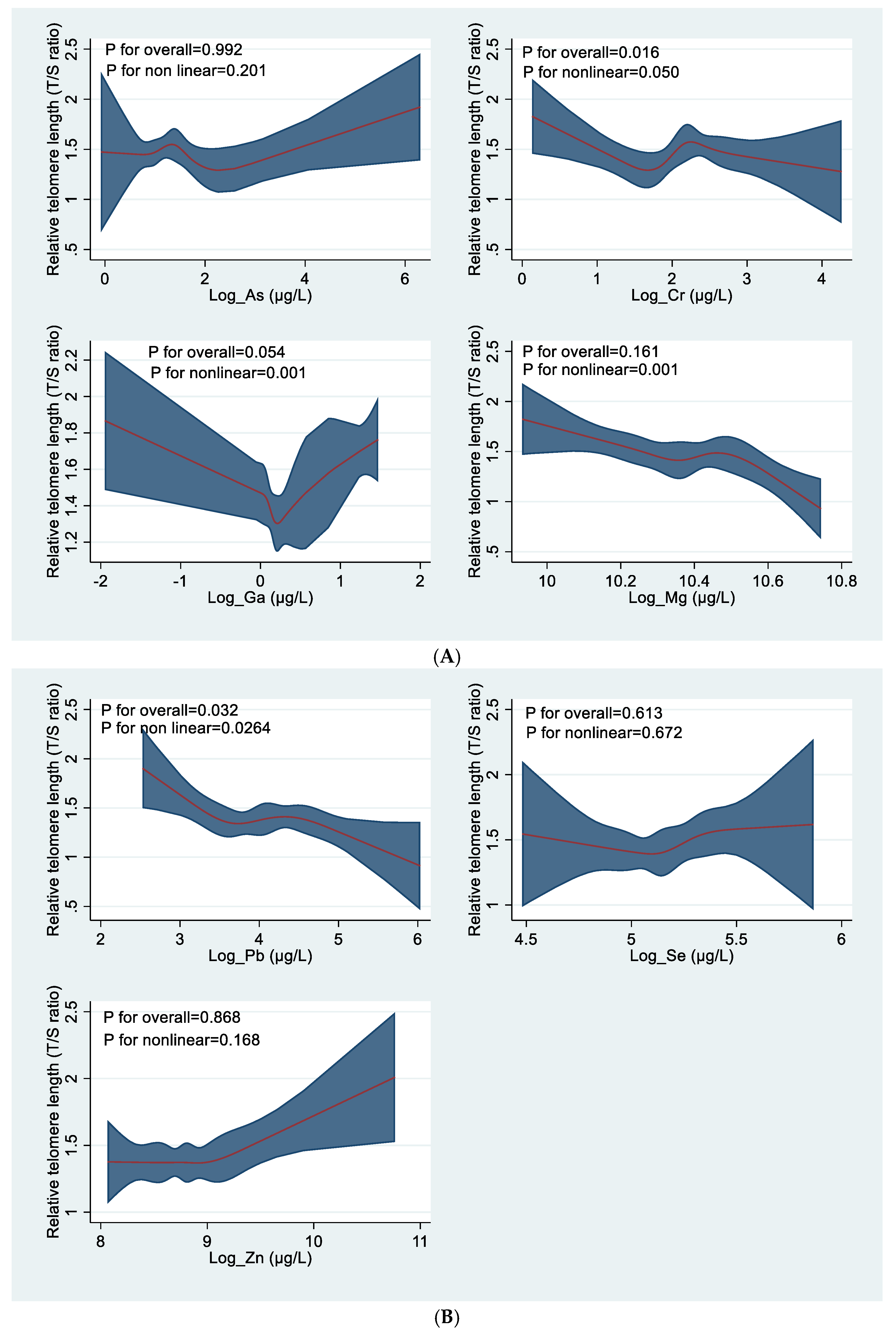

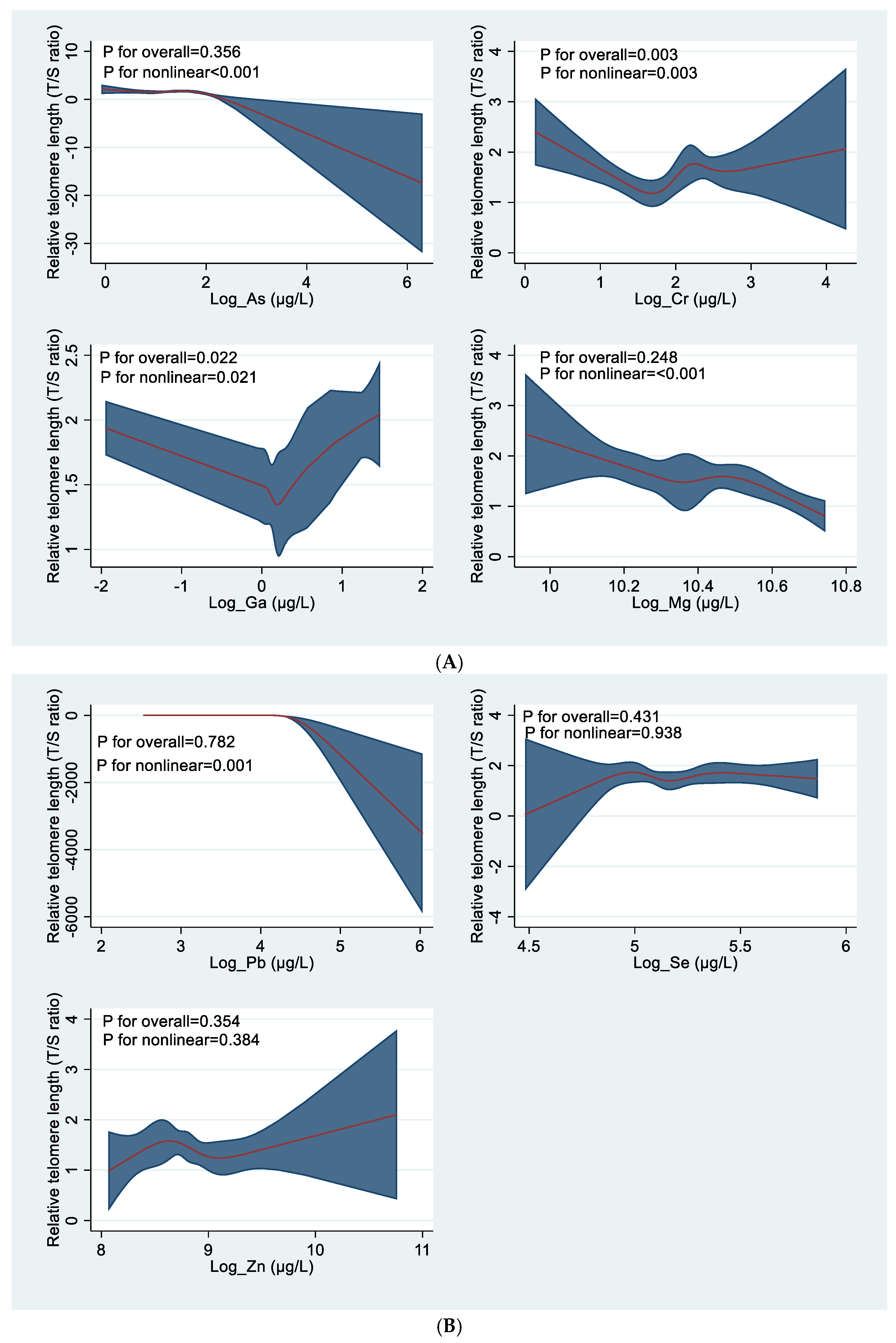

3.7. Relationship Between Metals in Blood and Relative Telomere Length

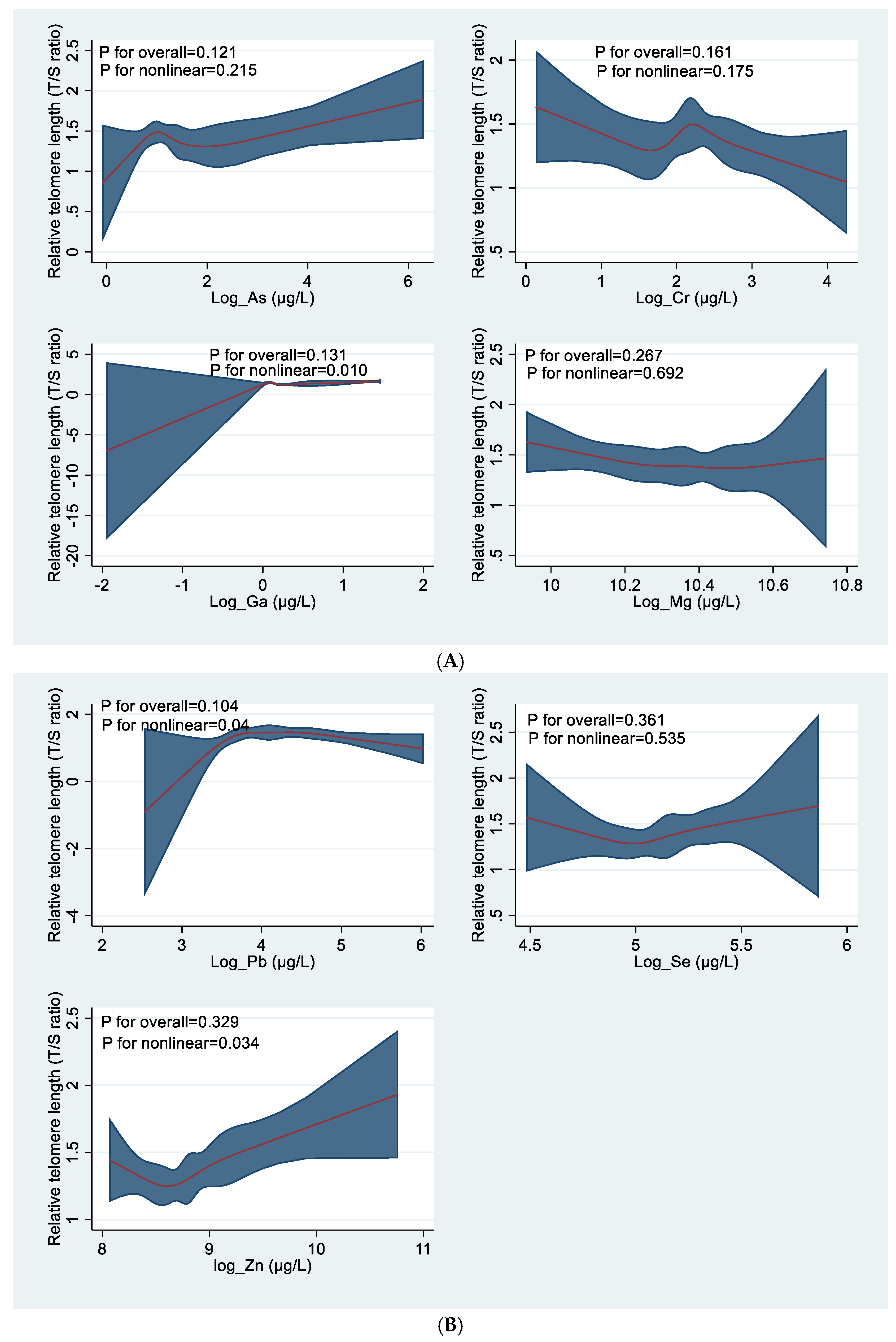

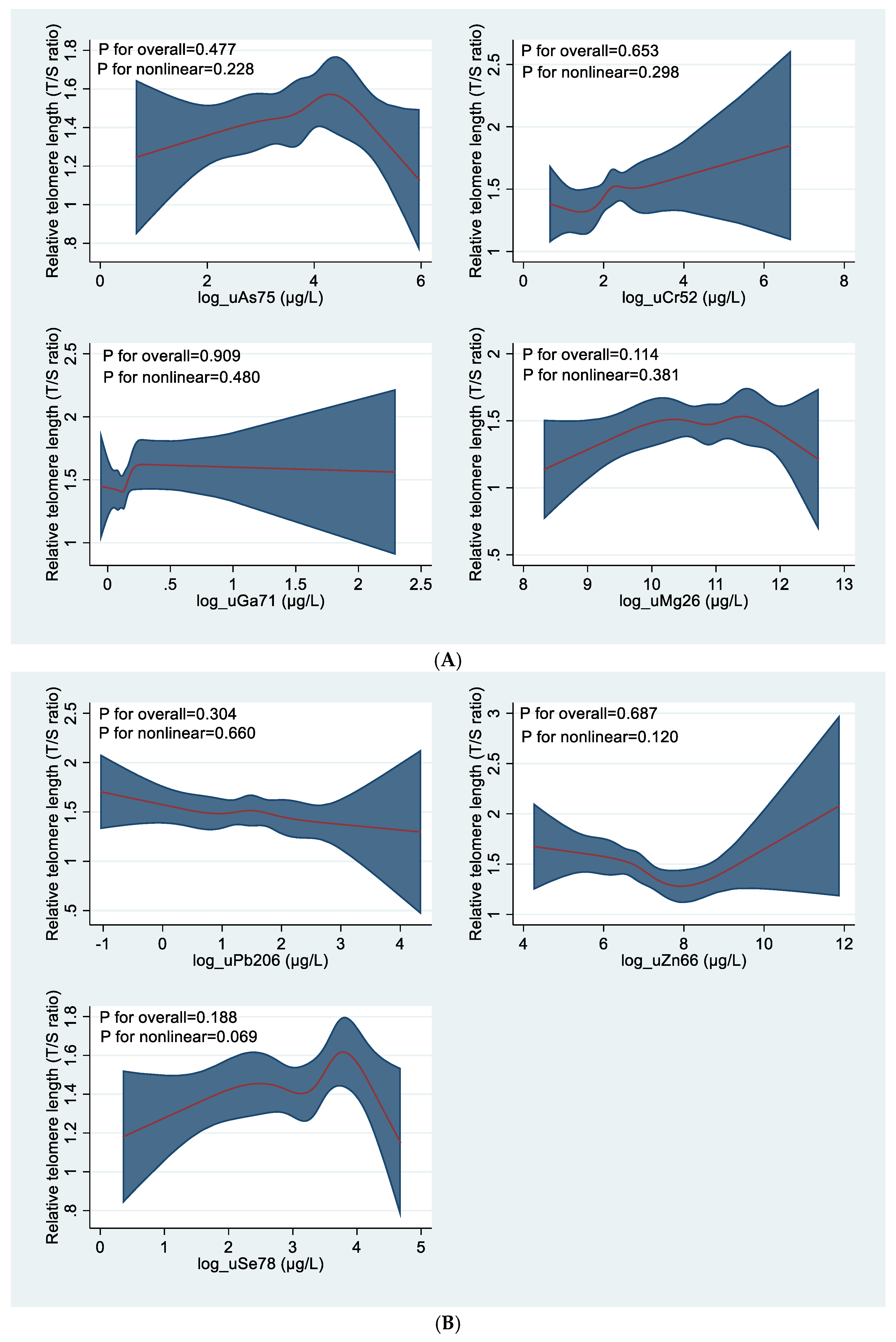

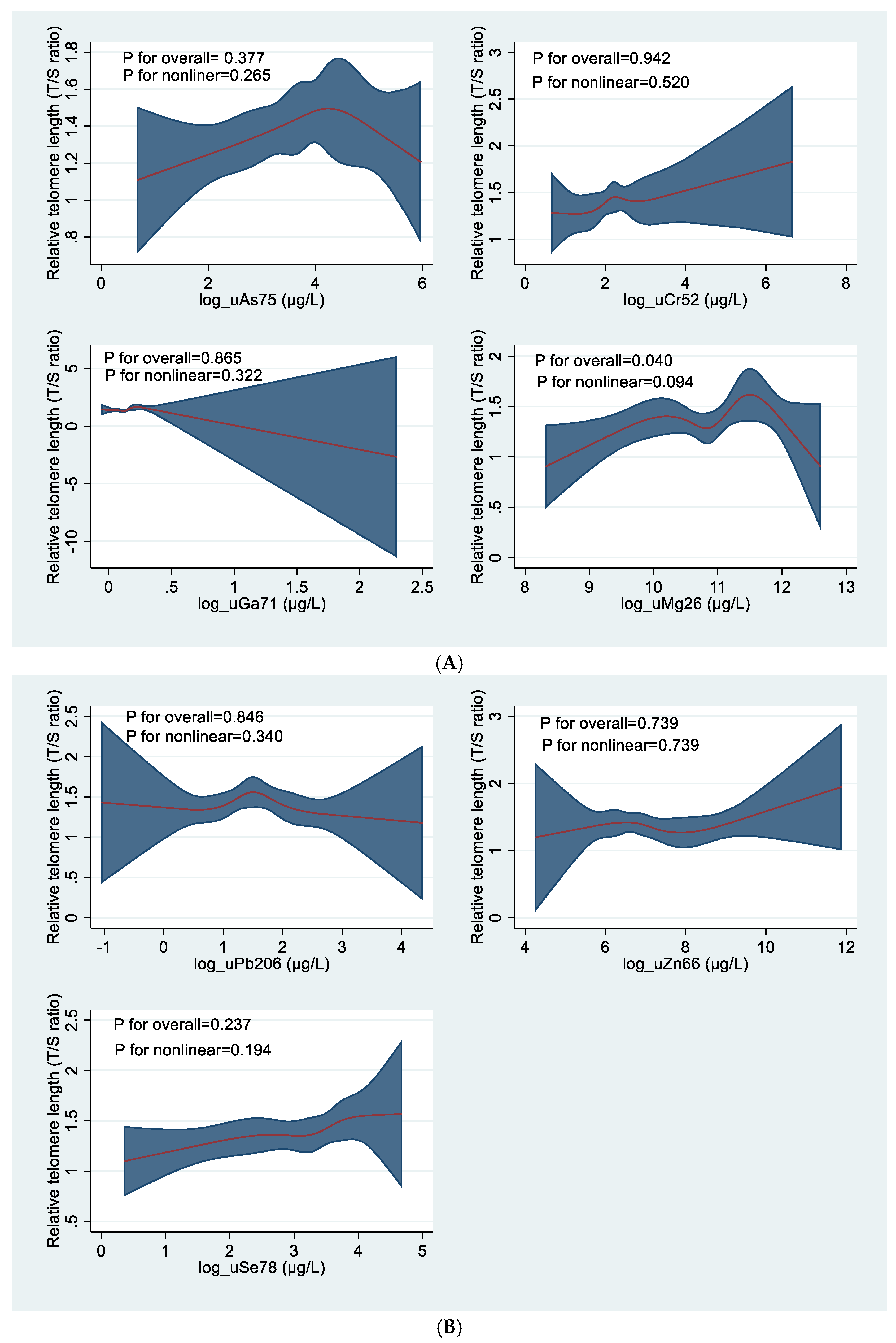

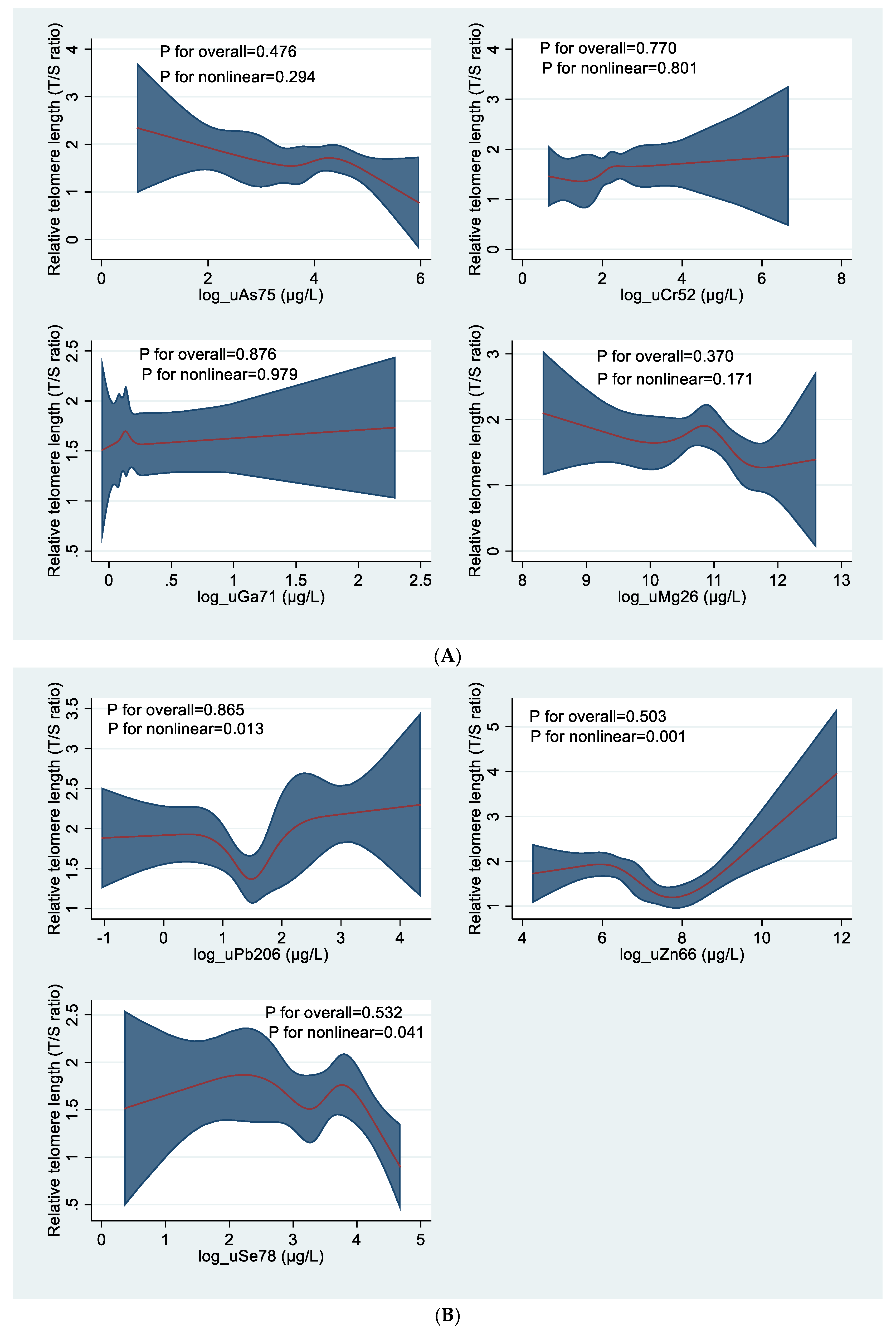

3.8. Relationship Between Metals in Urine and Relative Telomere Length

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TL | Telomere Length |

| rTL | Relative telomere length |

| E-waste | Electronic waste |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Lee, W.K., F. Thevenod, and E.J. Prenner, Global threat posed by metals and metalloids in the changing environment: a One Health approach to mechanisms of toxicity. Biometals, 2024. 37(3): p. 539-544.

- Das, S. , et al., Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Its Impact on Health: Exploring Green Technology for Remediation. Environ Health Insights, 2023. 17: p. 11786302231201259.

- Tchounwou, P.B. , et al., Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp Suppl, 2012. 101: p. 133-64.

- Mitra, S. , et al., Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. Journal of King Saud University - Science, 2022. 34(3).

- Briffa, J., E. Sinagra, and R. Blundell, Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon, 2020. 6(9): p. e04691.

- Dodd, M. , et al., Human health risk associated with metal exposure at Agbogbloshie e-waste site and the surrounding neighbourhood in Accra, Ghana. Environ Geochem Health, 2023. 45(7): p. 4515-4531.

- Issah, I. , et al., Health Risks Associated with Informal Electronic Waste Recycling in Africa: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(21).

- Althomali, R.H. , et al., Exposure to heavy metals and neurocognitive function in adults: a systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2024. 36(1).

- Zhang, D. , et al., Urinary essential and toxic metal mixtures, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Telomere shortening as an intermediary factor? J Hazard Mater, 2023. 459: p. 132329.

- Witkowska, D., J. Slowik, and K. Chilicka, Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules, 2021. 26(19).

- Liu, S. and M. Costa, Carcinogenicity of metal compounds, in Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals. 2022. p. 507-542.

- Domingo, J.L. and M. Marques, The effects of some essential and toxic metals/metalloids in COVID-19: A review. Food Chem Toxicol, 2021. 152: p. 112161.

- Wong, J.Y. , et al., The association between global DNA methylation and telomere length in a longitudinal study of boilermakers. Genet Epidemiol, 2014. 38(3): p. 254-64.

- Milne, E. , et al., Plasma micronutrient levels and telomere length in children. Nutrition, 2015. 31(2): p. 331-6.

- Pottier, G. , et al., Lead Exposure Induces Telomere Instability in Human Cells. PLoS One, 2013. 8(6): p. e67501.

- Srinivas, N., S. Rachakonda, and R. Kumar, Telomeres and Telomere Length: A General Overview. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(3).

- Niehoff, N.M. , et al., Hazardous air pollutants and telomere length in the Sister Study. Environmental Epidemiology, 2019. 3(4).

- Pawlas, N. , et al., Telomere length, telomerase expression, and oxidative stress in lead smelters. Toxicol Ind Health, 2016. 32(12): p. 1961-1970.

- Zhang, X. , et al., Environmental and occupational exposure to chemicals and telomere length in human studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2013. 70: p. 743 - 749.

- Pawlas, N. , et al., Telomere length in children environmentally exposed to low-to-moderate levels of lead. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2015. 287(2): p. 111-118.

- Lai, X. , et al., Individual and joint associations of co-exposure to multiple plasma metals with telomere length among middle-aged and older Chinese in the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. Environ Res, 2022. 214(Pt 3): p. 114031.

- Wai, K.M. , et al., Protective role of selenium in the shortening of telomere length in newborns induced by in utero heavy metal exposure. Environmental Research, 2020. 183: p. 109202.

- Mizuno, Y. , et al., Telomere length and urinary 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine and essential trace element concentrations in female Japanese university students. Journal of Environmental Science and Health - Part A Toxic/Hazardous Substances and Environmental Engineering, 2021. 56(12): p. 1328-1334.

- Amoabeng Nti, A.A. , et al., Personal exposure to particulate matter and heart rate variability among informal electronic waste workers at Agbogbloshie: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 2021. 21(1).

- Laskaris, Z. , et al., Derivation of Time-Activity Data Using Wearable Cameras and Measures of Personal Inhalation Exposure among Workers at an Informal Electronic-Waste Recovery Site in Ghana. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 2019. 63(8): p. 829-841.

- Takyi, S.A. , et al., Biomonitoring of metals in blood and urine of electronic waste (E-waste) recyclers at Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Chemosphere, 2021. 280: p. 130677.

- Grant, K. , et al., Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health, 2013. 1(6): p. e350-61.

- Frazzoli, C. , et al., Diagnostic health risk assessment of electronic waste on the general population in developing countries’ scenarios. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 2010. 30(6): p. 388-399.

- Julander, A. , et al., Formal recycling of e-waste leads to increased exposure to toxic metals: an occupational exposure study from Sweden. Environ Int, 2014. 73: p. 243-51.

- Collin, M.S. , et al., Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 2022. 7.

- Needleman, H.L. , Low level lead exposure and the development of children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 2004. 35(2): p. 252-4.

- Amoabeng Nti, A.A. , et al., Personal exposure to particulate matter and heart rate variability among informal electronic waste workers at Agbogbloshie: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 2021. 21(1): p. 2161.

- Okeme, J.O. and V.H. Arrandale, Electronic Waste Recycling: Occupational Exposures and Work-Related Health Effects. Curr Environ Health Rep, 2019. 6(4): p. 256-268.

- Jomova, K. and M. Valko, Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology, 2011. 283(2-3): p. 65-87.

- Barnes, R.P., E. Fouquerel, and P.L. Opresko, The impact of oxidative DNA damage and stress on telomere homeostasis. Mech Ageing Dev, 2019. 177: p. 37-45.

- M. Valko, H. Morris2 and M.T.D. Cronin, Metals toxicity and oxidative stress. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2005, 12, 1161–1208, 2005, 12: p. 1161-1208..

- Ahmed, W. and J. Lingner, Impact of oxidative stress on telomere biology. Differentiation, 2018. 99: p. 21-27.

- Srigboh, R.K. , et al., Multiple elemental exposures amongst workers at the Agbogbloshie electronic waste (e-waste) site in Ghana. Chemosphere, 2016. 164: p. 68-74.

- Jack Caravanos, E.C. , 2 Richard Fuller,3 Calah Lambertson1, Assessing worker and environmental chemical exposure risk jack caravanous J Health Pollution 1:16-25 (2011), 2011. 1: p. 16-25.

- Sepúlveda, A. , et al., A review of the environmental fate and effects of hazardous substances released from electrical and electronic equipments during recycling: Examples from China and India. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 2010. 30(1): p. 28-41.

- Espinosa-Otalora, R.E. , et al., Lifestyle effects on telomeric shortening as a factor associated with biological aging: A systematic review. Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 2020. 6(2): p. 95-103.

- Shammas, M.A. , Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2011. 14(1): p. 28-34.

- Beddingfield, Z. , et al., Review of Correlations Between Telomere Length and Metal Exposure Across Distinct Populations. Environments, 2024. 11(12).

- Herlin, M. , et al., Exploring telomere length in mother-newborn pairs in relation to exposure to multiple toxic metals and potential modifying effects by nutritional factors. BMC Med, 2019. 17(1): p. 77.

- Tang, P. , et al., Associations between prenatal multiple plasma metal exposure and newborn telomere length: Effect modification by maternal age and infant sex. Environ Pollut, 2022. 315: p. 120451.

- Zhang, Y. , et al., Cellular senescence mediates hexavalent chromium-associated lung function decline: Insights from a structural equation Model. Environ Pollut, 2024. 349: p. 123947.

- Wu, Y. , et al., High lead exposure is associated with telomere length shortening in Chinese battery manufacturing plant workers. Occup Environ Med, 2012. 69(8): p. 557-63.

- Wenlong Huang, X.S.a.K.W. , Human body burden of HM and health consequences International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021. 18(1 2428).

- Zhang, B. , et al., Elevated lead levels from e-waste exposure are linked to decreased olfactory memory in children. Environ Pollut, 2017. 231(Pt 1): p. 1112-1121.

- Costa, M. and C.B. Klein, Toxicity and carcinogenicity of chromium compounds in humans. Crit Rev Toxicol, 2006. 36(2): p. 155-63.

- Monga, A., A. B. Fulke, and D. Dasgupta, Recent developments in essentiality of trivalent chromium and toxicity of hexavalent chromium: Implications on human health and remediation strategies. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 2022. 7.

- Yan, G. , et al., Toxicity mechanisms and remediation strategies for chromium exposure in the environment. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2023. 11.

- Hui, F. , et al., Integrative modeling of urinary metabolomics and metal exposure reveals systemic impacts of electronic waste in exposed populations. metabolites, 2025. 15: p. 456.

- Pang, Z. , et al. Comprehensive Blood Metabolome and Exposome Analysis,.

- Annotation, and Interpretation in E-Waste Workers. metabolites, 2024. 14: p. 671.

- Issah, I. , et al., Exposure to metal mixtures and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes: A systematic review. Sci Total Environ, 2024. 908: p. 168380.

- Bianco-Miotto, T. , et al., Adverse pregnancy outcomes are associated with shorter telomere length in the 17-year-old child. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 2024. 15: p. e26.

- Barbagallo, M. and L.J. Dominguez, Magnesium and aging. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2010. 16(7): p. 833.

- Costello, R.B. and F. Nielsen, Interpreting magnesium status to enhance clinical care: key indicators. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2017. 20(6): p. 504-511.

- Maguire, D. , et al., Telomere Homeostasis: Interplay with Magnesium. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(1).

- Fernandes, S.G., R. Dsouza, and E. Khattar, External environmental agents influence telomere length and telomerase activity by modulating internal cellular processes: Implications in human aging. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2021. 85: p. 103633.

- Chasapis, C.T. , et al., Recent aspects of the effects of zinc on human health. Arch Toxicol, 2020. 94(5): p. 1443-1460.

- Maret, W. and H.H. Sandstead, Zinc requirements and the risks and benefits of zinc supplementation. J Trace Elem Med Biol, 2006. 20(1): p. 3-18.

- Todorov, L., I. Kostova, and M. Traykova, Lanthanum, Gallium and their Impact on Oxidative Stress. Curr Med Chem, 2019. 26(22): p. 4280-4295.

- Sanyal, T. , et al., Recent Advances in Arsenic Research: Significance of Differential Susceptibility and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation. Front Public Health, 2020. 8: p. 464.

| Total | E-waste workers | Reference group | p-value | |

| Characteristics | N=78 | n=53 | n=25 | |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean(±SD) | 22.5(3.5) | 21.7(2.8) | 24.4(4.1) | 0.002a |

| Age (years), mean(±SD) | 27.7(7.9) | 25.9(6.5) | 31.6±9.2 | 0.001a |

| Sleep location, n (%) | ||||

| On the site | NA | 32(60.4) | NA | |

| ≤1km off-site | NA | 21(39.6) | NA | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.116b | |||

| No formal | 12(15.38) | 10(18.9) | 2(8) | |

| education Primary | 18(23.08) | 13(24.5) | 5(20) | |

| Middle/JHS | 27(34.62) | 20(37.7) | 7(28) | |

| Secondary/SHS+ | 21(26.92) | 10(18.9) | 11(44) | |

| Indoor biomass use | 0.60b | |||

| Yes | 16(20.5) | 10(18.9) | 6(24) | |

| No | 62(79.5) | 43(81.1) | 19(76) | |

| Alcohol use, n(%) | 0.37b | |||

| Regular | 4(5.1) | 4(7.6) | 0(0) | |

| Former | 6(7.7) | 4(7.6) | 2(8.0) | |

| Never | 68(87.2) | 45(84.9) | 23(92) | |

| Smoking, n(%) | 0.08b | |||

| Yes | 15(19.2) | 13(24.5) | 2(8.0) | |

| No | 63(80.8) | 40(75.5) | 23(92) | |

| E-waste job category, n(%) | ||||

| Collectors/sorters | NA | 10(18.9) | NA | |

| Dismantlers | NA | 29(54.7) | ||

| Burners | NA | 14(26.4) | NA |

| (a) | |||||||||

| Metal (µg/L) | E-waste workers (n=53) | Reference Population (n=25) | p value | Study Population (N=78) | |||||

| Median(IQR) | |||||||||

| Zn | 6606.2 ( 2287.1 ) | 6636.05 (2092.1 ) | 0.5936 | 6607.4 (2210.7 ) | |||||

| Pb | 72.215 ( 43.065 ) | 31.395 (16.745 ) | <0.0001 | 57.87 (47.045) | |||||

| As | 3.745 (2.845 ) | 4.14 ( 2.68 ) | 0.1303 | 3.99 (2.88 ) | |||||

| Mg | 31535.18 (5503.385) | 32769.81 (7794.19 ) | 0.2178 | 31835.23 (5974.465 ) | |||||

| Cr | 8.9 ( 4.875) | 8.99 ( 6.38 ) | 0.8947 | 8.91 (5.325 ) | |||||

| Ga | 1.1897 ( .2826 ) | 1.1528 (.4424 ) | 0.6558 | 1.1774 (0.2993 ) | |||||

| Se | 166.03 ( 57.08 ) | 181.325 (42.305 ) | 0.004 | 170.47 (52.025) | |||||

| Legend: IQR=interquartile range, N= Total number of participants, n = sub study population, p - value obtained using Mann Whitney U test, bold p-values are statistically significant. | |||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||

| Wave | Metal (µg/L) | Total (N=78) | |||||||

| E-waste workers (n=53) | Reference population (n=25) | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Difference | p-value | ||||||

| One | Zn | 7235.2(3320.8) | 7907.4(1520.55) | 672.2 | 0.261 | ||||

| Pb | 82.735(42.325) | 36.51(17.57) | 46.225 | <0.0001 | |||||

| As | 6.405(8.76) | 6.085 (1.84) | 0.32 | 0.763 | |||||

| Mg | 34574.89(5849.49) | 37939.5(7544.565) | 3364.605 | 0.047 | |||||

| Cr | 6.155(2.245) | 4.8(1.89) | 1.355 | 0.015 | |||||

| Ga | 1.082(0.1292) | 1.1108(.1471) | 0.0288 | 0.407 | |||||

| Se | 146.01(50.405) | 172.94 (40.365) | 26.93 | 0.018 | |||||

| Two | Zn | 5985.15(1910.75) | 6169.95(1558.4) | 184.8 | 0.672 | ||||

| Pb | 71.57(40.37) | 31.12(13.07) | 40.45 | <0.0001 | |||||

| As | 2.77(1.335) | 3.21(1.51) | 0.44 | 0.2 | |||||

| Mg | 30430.01(5174.93) | 30116.43(5624.045) | 313.58 | 0.817 | |||||

| Cr | 9.27(3.61) | 9.985(3.345) | 0.715 | 0.42 | |||||

| Ga | 3.4426(2.3553) | 2.5292(2.3362) | 0.9134 | 0.144 | |||||

| Se | 179.015(45.115) | 169.03(35.7) | 9.985 | 0.347 | |||||

| Three | Zn | 6650.75(1857.8) | 6275.3 (1769.6) | 332.1 | 0.44 | ||||

| Pb | 70.135(36.22) | 28.445(9.475) | 41.8 | <0.0001 | |||||

| As | 3.0925(2.2825) | 3.855(2.105) | 0.67 | 0.194 | |||||

| Mg | 30616.94(4204.567) | 28978.04(4757.895) | 1558.385 | 0.129 | |||||

| Cr | 11.205(3.75) | 12.115(3.995) | 0.78 | 0.377 | |||||

| Ga | 1.1613(0.1235) | 1.116(0.0765) | 0.0458 | 0.097 | |||||

| Se | 170.055(48.405) | 193.53 (38.49) | 23.06 | 0.025 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).