Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

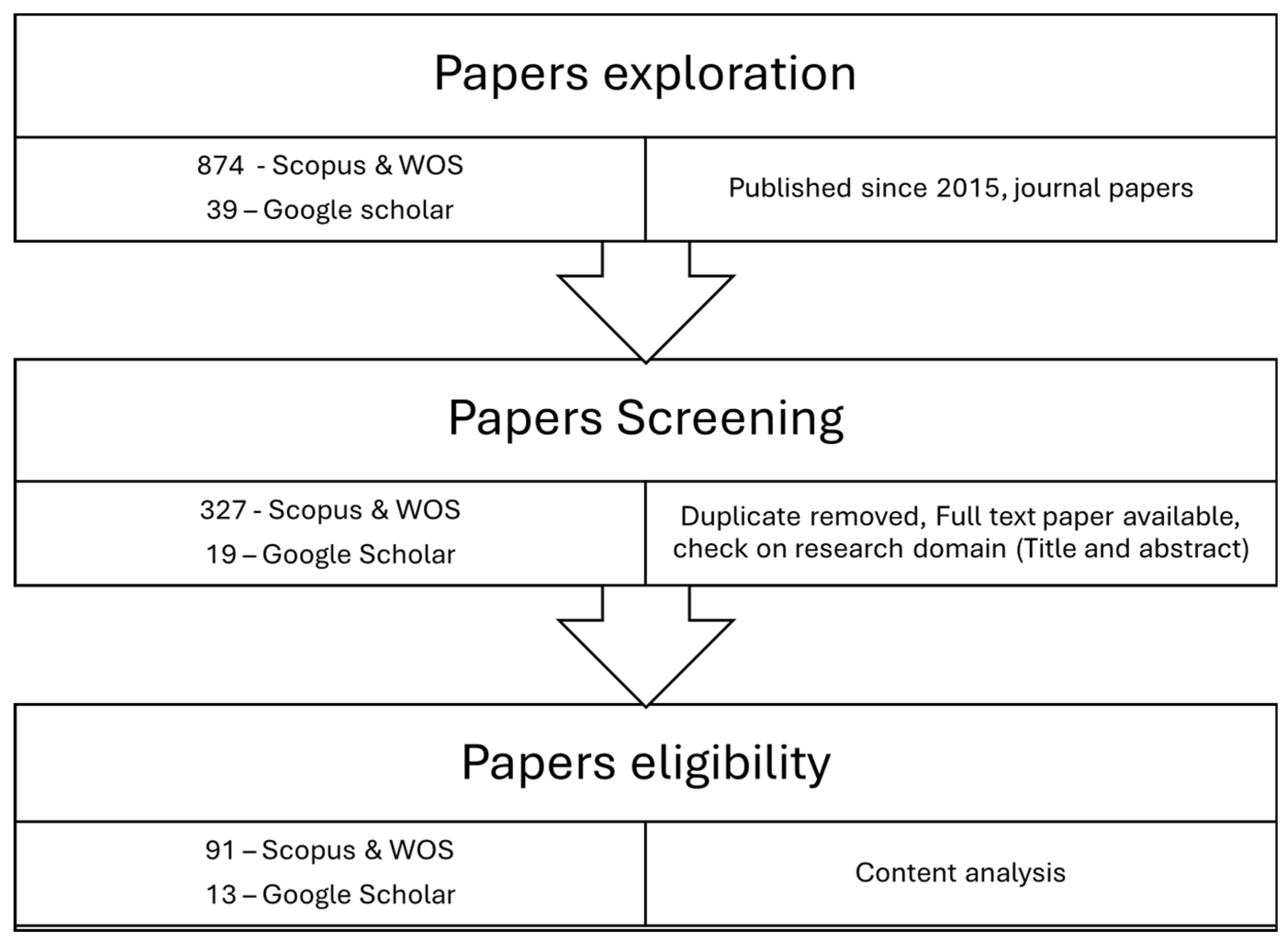

26 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

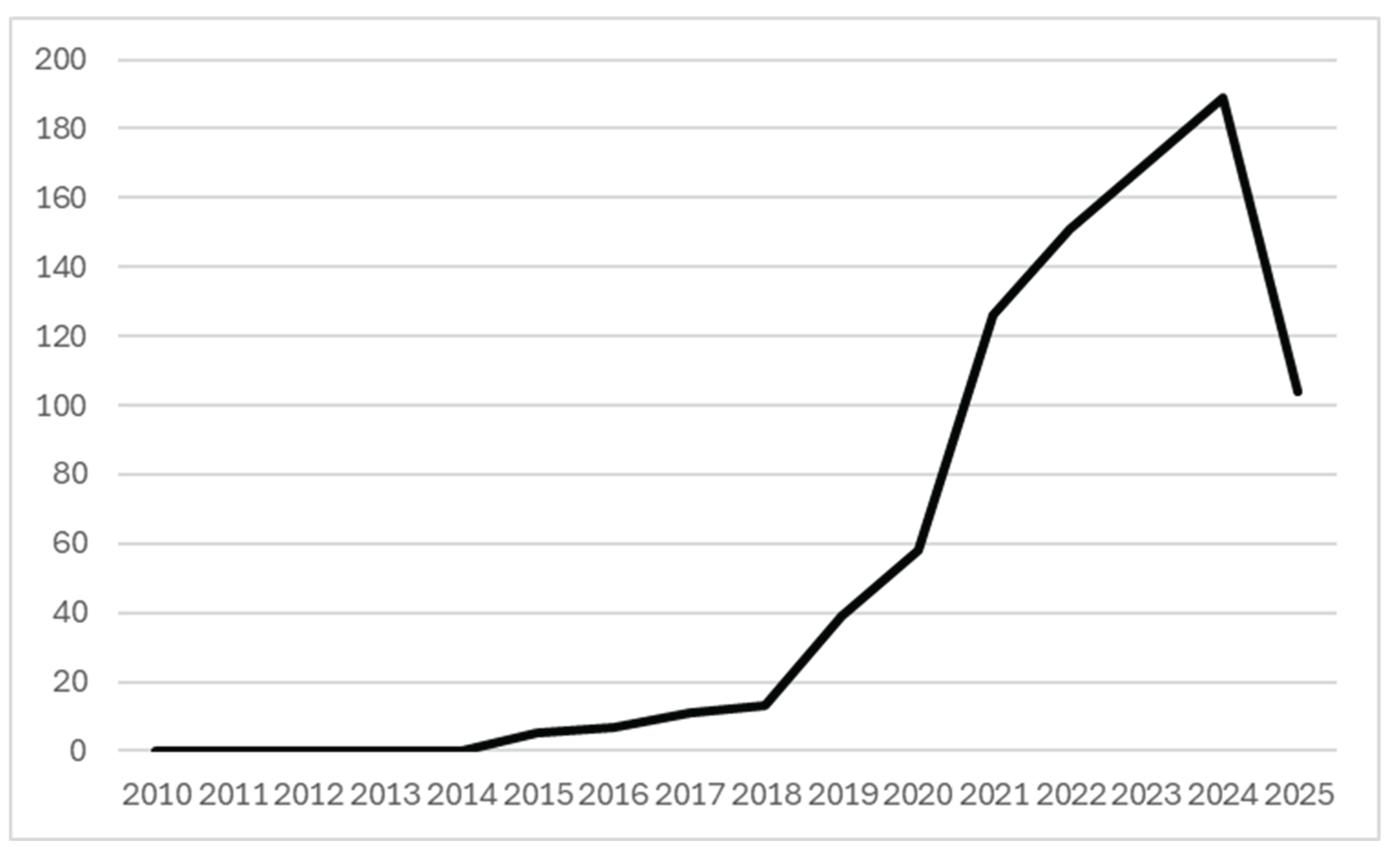

1. Introduction

- What are the main characteristics of energy communities worldwide?

- How are energy communities being implemented in Latin America?

- At what level are the barriers to a just and sustainable energy transition in the region for grid-connected energy communities?

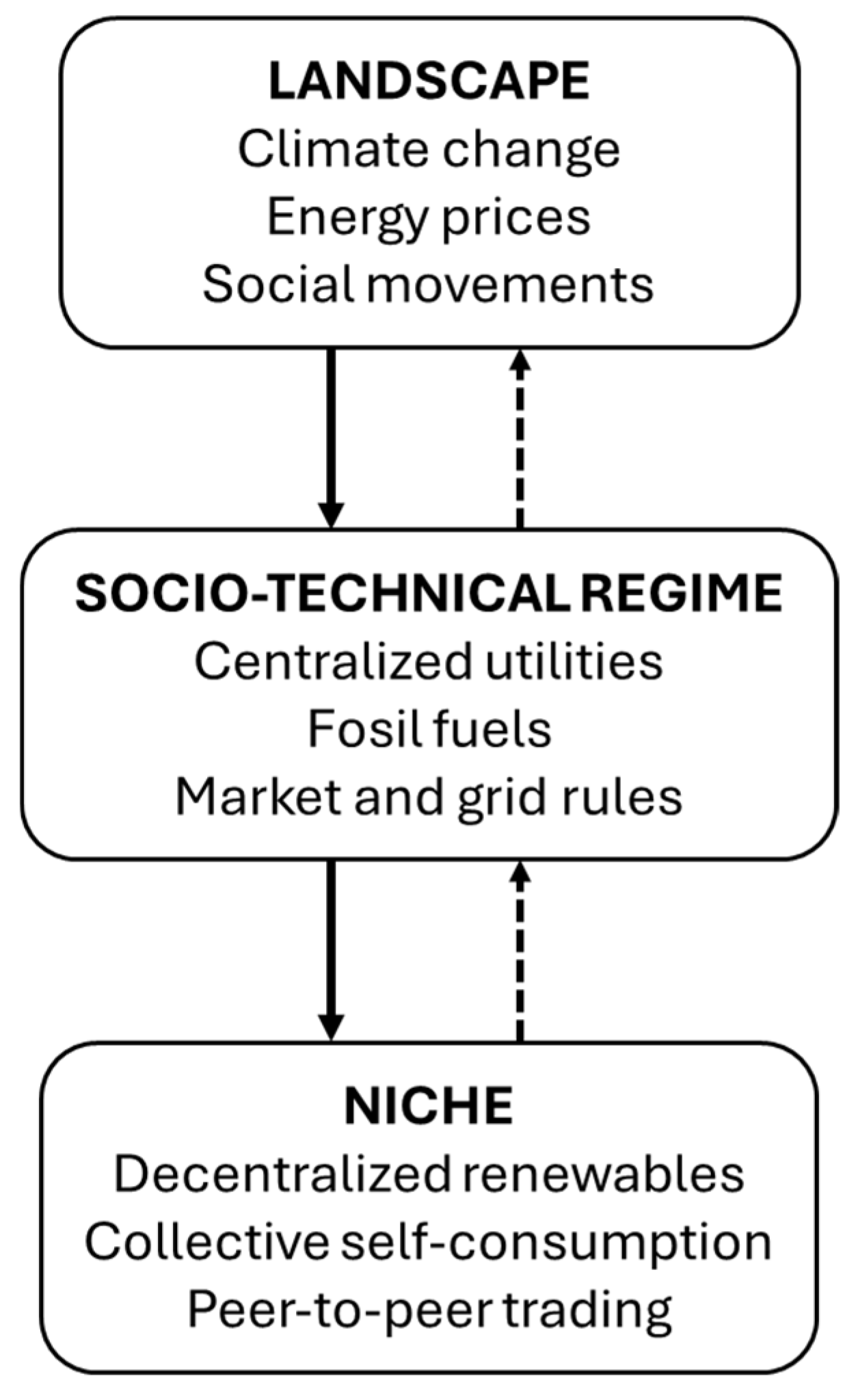

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Multi-Level Perspective Framework

2.2. MLP Analysis of Energy Communities

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Mapping Energy Communities Worldwide

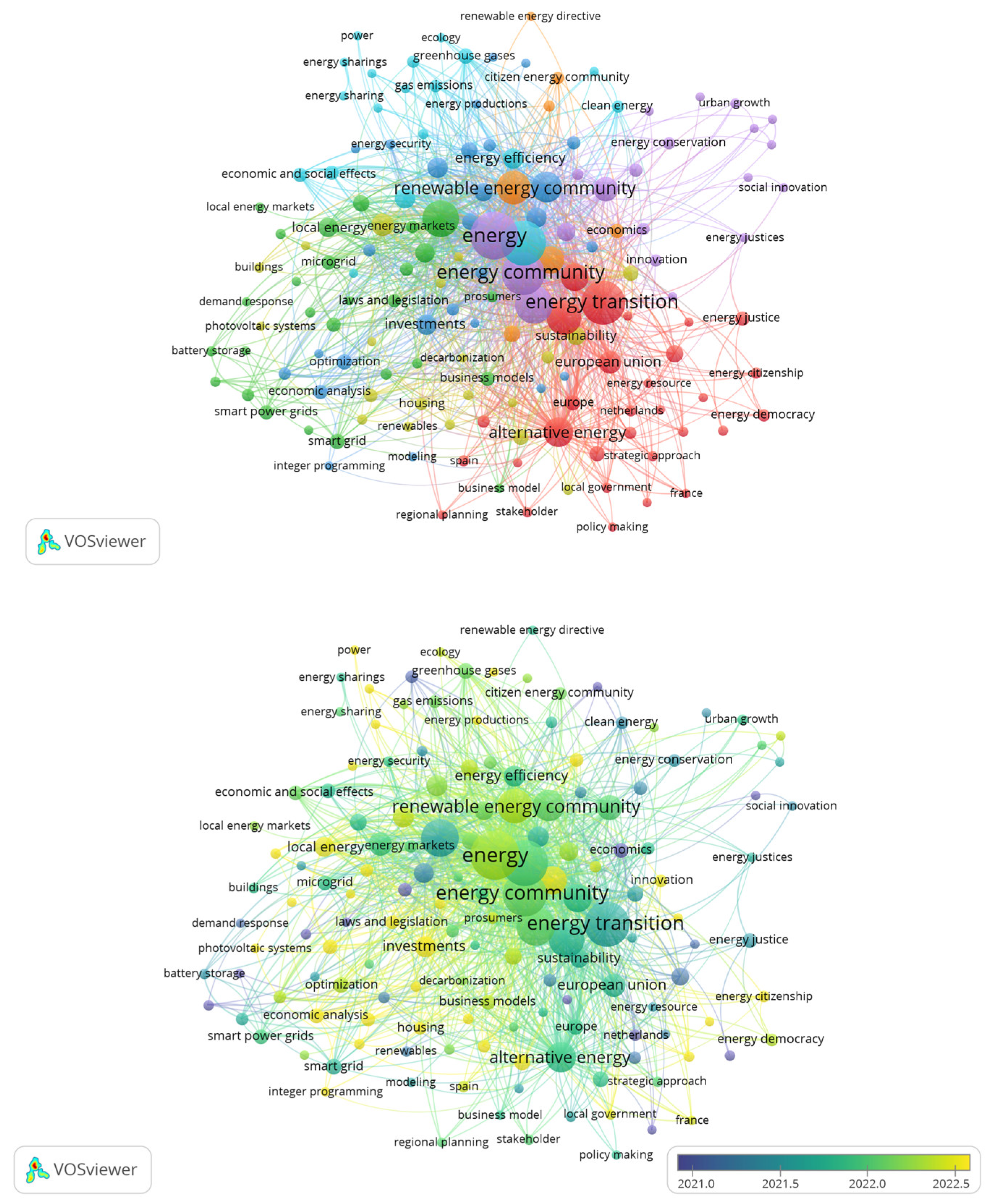

4.1.1. Energy Communities’ Main Topics

4.1.1.1. Energy Community Definitions

4.1.1.2. Business and Economics

4.1.1.3. Regulatory and Institutional

4.1.1.4. Socio-Political

4.1.1.5. Technical

4.1.2. Research Problems and Findings of Previous Studies

4.1.2.1. Comprehensive Approaches to Energy Communities

- Regulation and institutions. Reviews highlight the need for clear recognition of stakeholder rights and obligations, especially for prosumers and collective actors. At the European level, EC frameworks define rights and responsibilities regarding microgrids, energy hubs, and virtual power plants [20]. Yet, tensions persist between decentralized ownership and the natural monopoly of transmission and distribution infrastructure.

- Socio-political dimensions. Citizen participation and energy democracy remain central, but barriers include limited willingness to participate, organizational challenges, and regulatory uncertainty [50].

- Technological innovation. Reviews emphasize ICT-based tools, including blockchain and smart grids, for managing distributed resources [54,56,78]. Microgrids are seen as essential to address variability, while blockchain facilitates trust, aggregation, and peer-to-peer exchange. Nevertheless, privacy and security remain unresolved challenges.

4.1.2.3. Territorial Perspectives

- Institutional and socio-political support is decisive. Reviews consistently show that laws, policies, and governance structures—together with active citizen participation—are central to EC emergence and sustainability.

- Technology is essential but underregulated. Smart grids, IoT, and blockchain enable flexibility and trust but raise unresolved issues of privacy, interoperability, and cybersecurity

- Business models are evolving. EC models are shifting from grassroots initiatives toward more professionalized, multi-service structures, with growing emphasis on environmental and social goals.

- Territorial disparities persist. Europe dominates the literature, while SSA and Latin America remain underexplored despite their distinct challenges and opportunities.

4.2. Patterns of On-Grid Energy Communities Implementation in Latin America

4.2.1. Just and Democratic Energy Systems with Social Engagement

4.2.2. Incentives and Equitable Distribution of Business Benefits

4.2.3. Grid Connection and Diversification of Non-Conventional Energy Sources

5. Discussion

5.1. Barriers to the Latin American Energy Transition

5.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- Aiming for fair and democratic energy systems through active social engagement.

- Use of incentives like net metering and feed-in tariffs to encourage a more equitable distribution of benefits through cooperatives and third parties.

- Connecting to the grid and diversifying non-conventional energy sources tailored to community needs, resources, and geographical specificities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AND | Active Distribution Networks. |

| ANEEL | National Electric Energy Agency. |

| BMs | Business Models. |

| CEC | Citizen Energy Communities. |

| CEP | Clean Energy Package. |

| CREG | Energy and Gas Regulation Commission. |

| CSOP | Consumer Stock Ownership Plan. |

| CSS | Community-Shared Solar. |

| cVPP | Community-based Virtual Power Plant |

| DG | Distributed Generation. |

| DSM | Demand-side Management. |

| DSO | Distribution system operator |

| ECs | Energy Communities. |

| EE | Energy Efficiency. |

| EMD | Electricity Market Directive. |

| EH | Energy Hubs. |

| EPC | Energy Performance Contracting. |

| ESCO | Community Energy Services Company. |

| FEP | Flat Energy Pricing. |

| ICT | Information and communication technologies |

| IEMD | Internal Electricity Market Directive. |

| IoT | Internet of Things. |

| kW | KiloWatts. |

| LEC | Local Energy Communities |

| MLP | Multi-Level Perspective. |

| MW | Mega-Watts. |

| NCREs | Non-Conventional Renewable Energy Sources |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations. |

| P2P | Peer-to-peer. |

| P4P | Pay for Performance. |

| PROINFA | Program for Alternative Electricity Sources. |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. |

| PV | Photo-Voltaic. |

| REC | Renewable Energy Communities. |

| RED | Renewable Energy Directive. |

| RES | Renewable Energy Source. |

| SG | Smart Grid. |

| SEG | Segment energy pricing. |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises. |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa. |

| TOU | Time-of-use energy pricing. |

| VPPs | Virtual Power Plants. |

Appendix A

| Country | On-Grid Energy Community | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Armstrong | The Santa Fe province was Argentina’s first jurisdiction to enable the possibility of connecting distributed renewable energy systems to the grid. In 2013, the Armstrong Electric Cooperative joined a project with the National Technological University and the National Institute of Industrial Technology research group to develop an intelligent grid with distributed generation in Armstrong. The project’s first stage focused on commissioning two types of photovoltaic systems: a 200 kW generation plant in the Armstrong Industrial Area (owned by the cooperative) and 50 1.5 kW systems on the roofs of the cooperative’s users’ homes. | [11,86,87] |

| Brazil | Juazeiro | The program was implemented by the Caixa Econômica Federal (CAIXA public bank) in partnership with Brazil Solair (private company) in the Praia do Rodeadouro and Morada do Salitre condominiums, both located in Juazeiro, Bahia, Brazil and part of the popular housing program My House My Life (MCMV—Minha Casa Minha Vida, Law 11.977/2009). The program’s objective was to generate energy and income, help the development of solar technology in the distributed modality in Brazil, and reduce poverty. In 2014, 9156 photovoltaic (PV) panels of 230 W were installed on the rooftops of popular residences, and 6 micro-wind turbines of 5kWp in the common area, totaling 2.1MWp of renewable generation capacity in the condominiums as mentioned earlier, considered the first mini plant of PV distributed generation in Brazil. | [65,82] |

| Coober | Coober Energy Cooperative is located in Paragominas (PA) and has had a 75 kW solar photovoltaic system installed on the ground and connected to the grid since 2016. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill of its 23 members. | [88] | |

| Cooper Sustentavel | Cooper Sustentavel Energy Cooperative is in the towns of São José (SC) and Arcos (MG). It has installed two solar photovoltaic systems, 1 kW and 0.5 kW, on the ground and connected to the grid since 2017. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill of its 34 members. | ||

| Enercred | The Enercred Energy Cooperative is located in Pedralva (MG) and has had a 180 kW photovoltaic solar system installed on the ground and connected to the grid since 2017. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill of its 90 members. | ||

| Compartsol | Compartsol Energy Cooperative is in Araçoiaba da Serra (SP). It has a 1.4 MW solar photovoltaic system installed on the ground and connected to the grid since 2017. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill of its 63 members. | ||

| Sicoob Centro-Serrano ES | The Sicoob Energy Cooperative is located in the town of Santa Maria de Jetibá (ES) and has had a 36 kW photovoltaic solar system installed on rooftops and connected to the grid since 2017. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill for 6 of its members. | ||

| Coopercitrus | The Coopercitrus Energy Cooperative is in Bebedouro (SP). It has a 1 MW solar photovoltaic system installed on the ground and connected to the grid since 2019. The energy generated offsets the electricity bills of 28 of its members. | ||

| Sistema Sicoob ES | Sistema Sicoob Energy Cooperative Sicoob has a 1 MW solar photovoltaic system installed on rooftops and connected to the grid since 2019. The energy generated offsets the electricity bill to 170 member users of this and other cooperatives. | ||

| Alka Energy | ALKA Energia is an energy management company in the Agricopel group in Florianópolis, SC. It generates 1 MW of solar PV energy and offers its customers clean energy with reliability and savings. With ALKA, you can reduce your energy bill by up to 20%—an essential saving for any business. | [99] | |

| Nex Energy | NEX Energy generates energy through photovoltaic, hydroelectric, biomass, and biogas systems. It operates in 10 states and uses energy credits. | ||

| Cogecom | Cogecom was founded in 2018 and is based in Curitiba, PR. The cooperative currently has 820 members connected to Copel and generates renewable energy through a biomass plant in Carambeí-PR (5000 kW) and a biogas plant in Castrolândia-PR, PR. | ||

| Paraná Energia | Paraná Renewable Energy Cooperative was founded on May 30, 2019. Paraná Energia prioritizes the principles of equality and democratic participation and works to generate financial savings for all its members. | ||

| Ambicoop | The Ambicoop Cooperative, based in Toledo-PR, arose from the need to structure a collective solution to the environmental problem of animal waste in western Paraná. A pilot project was set up in 2021 and is scheduled to start operating by the end of 2023. The waste will be collected through a piping system, and a centralized biogas plant will use the waste to generate renewable energy and produce biofertilizer. It has a generation capacity of 2,300 kW and benefits 48 consumers by receiving energy credits. | ||

| Sun Mobi | Pay-as-you-go solar energy. Sun Mobi manages all the infrastructure and maintenance of the solar farms (13MW installed capacity) that generate clean, renewable energy. The energy generated is injected into the distribution network and transformed into credits, which can be used on any electricity bill of consumers of CPFL Piratininga, CPFL Paulista, COPEL, Enel and Elektro. | ||

| Hadar do Sol | The Hadar do Sol Cooperative, established in 2022, is an initiative that generates solar energy and provides energy credits. The energy is generated in the cooperative’s power plants and then integrated into the electricity concessionaire’s grid. The distribution of this energy among our members follows a division established by the cooperative. | ||

| Enercred | In 2017, Enercred pioneered the renewable energy subscription model for residential and commercial consumers in Minas Gerais. Enercred currently has two photovoltaic solar power plants in Pedralva-MG, which have 180 kWp of installed power together. These plants supply renewable and decentralised energy to 200 homes connected to CEMIG. | ||

| RenovaEco | RenovaEco Renewable Energy Cooperative was founded at the end of 2019 based on the understanding of its 25 founding members of the existing needs, opportunities, and challenges related to renewable energy and local cooperatives. RenovaEco is a Renewable Energy Cooperative that acts as a platform to connect renewable energy suppliers with those interested in consuming this energy. | ||

| Ciclos | In 2018, Sicoob-ES set up the Platform Cooperative - Ciclos, a solution to increase the range of products and services offered to the Credit Union’s members. Today, the platform offers telephony services, renewable energy, and health solutions. To generate solar energy, Sicoob-ES inaugurated a 1 MWp complex comprising ten photovoltaic generating plants (UFV), which serve both Sicoob branches in the state and Ciclos members. Of this complex, 240 kWp currently generates credits for 86 households connected to EDP’s distribution network in Espírito Santo. | ||

| Cooperativa de Energias Renováveis do Nordeste | This cooperative was established in 2021 to generate solar energy and offer energy credits. Twenty-six homes and businesses benefit from the generation. | ||

| Sol Invictus | Since 2020, Sol Invictus has hired photovoltaic plants at competitive prices and passed on the energy credits to its members. The members receive their credit quota directly on their electricity bill. The utility company deducts this amount, and the member pays the deducted amount to Sol Invictus at a discount. | ||

| Mobe Coop | The Electricity Consumers’ Co-operative (Mobe Coop) is a shared distributed generation cooperative founded in 2020. It has an installed capacity of 56 kW and provides energy credits to 24 consumers. | ||

| Cooperativa Ben Viver | The Bem Viver cooperative is a photovoltaic solar energy generation initiative founded in 2020. The cooperative currently has two electricity generation plants (63 kW). The energy generated is injected into the distributor’s grid and converted into energy credits, which are subsequently apportioned (shared) among the members according to a percentage proportional to the investment made by each member in the energy generation plant. | ||

| Cooerma | COOERMA was formed in 2019 in the municipality of Açailândia in the southwestern region of Maranhão. The first photovoltaic solar plant is being completed in the village of Curvelândia, in Vila Nova dos Martirios - MA. The plant has an installed capacity of 75 kW, which will be injected into the Equatorial Energia utility grid via its own 75 kW substation to generate credits on the bills of cooperative members spread across the municipalities of Açailândia - MA, Cidelândia - MA, Imperatriz - MA and the capital São Luís do Maranhão. | ||

| Chile | Petorca Sustentable | It is a user group initiative created in 2021. The Municipality of Petorca is part of the project, while the 18 other participants are “electro-dependent” beneficiaries. The development organization of the community project, i.e., the one in charge of the development and support phases before construction, is AMC Energía. It has an installed capacity of 66.3 kW of solar photovoltaic energy. It is currently in operation. | [99] |

| Til Til | The Community solar plant is a cooperative, created in 2023, of services of 40 people/associated organizations, located in the metropolitan region of Santiago. SOLCOR is the installer of the project, but EBP Chile, Red de Pobreza Energética, EGEA ONG, REPIC, the Municipality of Tiltil, Pro Tiltil, ECOSYS and Codelco are accompanying the project. It has an installed capacity of 50 kW of photovoltaic solar energy. It is currently out of operation. | ||

| Nueva Zelandia | Community solar energy. It is a group founded in 2022 that offers solar energy to 20 people/organizations. Of the participants in the Municipality of Independencia; 15 are neighbors of Población Juan Antonio Ríos, a neighbor of the school where the solar panels are mounted, and 4 are investors. The organization developing the community project is the Red Genera Work Cooperative, which oversees the development and support phases before construction. It is currently out of operation with an installed capacity of 15 kW of photovoltaic solar energy. | ||

| Cooperativa Coopeumo | It is a group of 9 users receiving injections and 328 associated people and organizations created in 2021. Coopeumo shares energy between Coopeumo Cooperative establishments and public buildings such as schools and health centers of the Municipality of Pichidegua. The development organization of the community project, meaning the one in charge of the development and support phases before construction, is the Red Genera Worker Cooperative. It has an installed power of 32 kW of photovoltaic solar energy. | ||

| Colombia | Comuna 13 | It is Colombia’s first peer-to-peer energy exchange pilot, in a joint work of EIA University, EPM, ERCO, NEU, and University College London. The pilot consisted of digitally connecting 12 residential users of different strata and a cultural center, distributed in different neighborhoods of the Metropolitan Area of the Aburrá Valley, through a digital platform, through which the purchase and sale of the energy they generated and consumed were simulated. | [94,97,99] |

| La Estrecha | La Estrecha Solar Community. In 2021, a university and several energy companies cooperated with local citizens to create a solar community in a middle-income neighborhood in Medellin, Colombia. The community aims to enable the beneficiaries to produce energy and sell it to the grid operator for economic benefit. The community comprises 24 stratum families, three living in the same block. Under a distributed generation scheme, these families were installed with two photovoltaic systems with 6 kWp and 14 kWp capacities. | [83,99,100] | |

| Alagro | The Alagro Cooperative comprises 236 agricultural producers, mainly in the dairy sector, to whom it provides collection, purchasing, and marketing services. As a pilot test, in 2021, the Cooperative received a photovoltaic energy generation system for 1 of its tanks, located in the Abreo district of the municipality of Rionegro (Antioquia), where around 150 liters of milk are collected daily from 10 producer families. This implementation has strengthened the cooperative in the social (legitimacy and institutional experience), economic (cost reduction), and environmental (reduction of 1 ton of CO2 emissions per year) spheres. | [99] | |

| Mexico | La Esperanza | Located in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, La Esperanza is a cooperative project that produces zero-emission bricks using photovoltaic technology and electric hydraulic presses. Surplus energy will be sold to the electricity grid. | [99] |

| CEEOAX | The Oaxaca Energy and Ecology Cooperative was established in 2022. It was created to train indigenous communities in agroecological production and fair trade. The cooperative also has an installed capacity of 10 kW of solar energy, allowing it to sell surplus energy to the grid. |

| ID | Year | Title | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2021 | Business models for energy communities: A review of key issues and trends | [52] |

| 2 | 2022 | The role of energy democracy and Energy Citizenship for participatory energy transitions: A comprehensive review | [50] |

| 3 | 2022 | Conceptualizing community in energy systems: A systematic review of 183 definitions | [4] |

| 4 | 2022 | Towards collective energy Community: Potential roles of microgrid and blockchain to go beyond P2P energy trading | [78] |

| 5 | 2021 | Towards data-driven energy communities: A review of open-source datasets, models, and tools | [54] |

| 6 | 2022 | A transition perspective on Energy Communities: A systematic literature review and research agenda | [1] |

| 7 | 2023 | A review and mapping exercise of energy community regulatory challenges in European member states based on a survey of collective energy actors | [20] |

| 8 | 2021 | A review of energy communities in Sub-Saharan Africa as a transition pathway to energy democracy | [23] |

| 9 | 2022 | Greek Islands’ Energy Transition: From Lighthouse Projects to the Emergence of Energy Communities | [3] |

| 10 | 2022 | Conceptual design of energy market topologies for communities and their practical applications in EU: A comparison of three case studies | [5] |

| 11 | 2022 | Thermal/Cooling Energy on Local Energy Communities: A Critical Review | [56] |

| 12 | 2023 | An interdisciplinary understanding of energy citizenship: Integrating psychological, legal, and economic perspectives on a citizen-centred sustainable energy transition | [42] |

| 13 | 2023 | The Emerging Trends of Renewable Energy Communities’ Development in Italy | [21] |

| 14 | 2022 | Economic, social, and environmental aspects of Positive Energy Districts—A review | [53] |

| 15 | 2022 | Renewable energy communities or ecosystems: An analysis of selected cases | [36] |

| 16 | 2023 | Key Aspects and Challenges in the Implementation of Energy Communities | [22] |

| 17 | 2023 | Critical Review on Community-Shared Solar-Advantages, Challenges, and Future Directions | [38] |

| 18 | 2024 | A Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations | [2] |

| 19 | 2024 | European energy communities: Characteristics, trends, business models and legal framework | [24] |

| 20 | 2024 | Exploring the academic landscape of energy communities in Europe: A systematic literature review | [19] |

| 21 | 2023 | Energy Communities: A review on trends, energy system modeling, business models, and optimisation objectives | [51] |

| 22 | 2022 | Energy communities in sustainable transitions: the South American case | [11] |

| 23 | 2025 | Key aspects and challenges for successful energy communities: A comparative analysis between Latin America and developed countries | [79] |

| Country | Year, Norm | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1998, Law 25.019 | National Wind and Solar Energy Regime. Individuals or legal entities domiciled in the country may generate electric energy from wind and solar energy constituted under the legislation in force. | [101] |

| 2006, Law 26.190 | It is the National Promotion Regime for using renewable energy sources to produce electricity. This law promotes the realization of new investments in electric energy production undertakings based on using renewable energy sources throughout the national territory. | [87,102] | |

| 2015, Law 27.191 | National promotion Regime for using renewable energy sources to produce electric power. Modification. Creation of the public trust fund. The objective of this regime is to achieve a contribution of renewable energy sources up to eight percent (8%) of the national electric energy consumption by December 31, 2017. | [87,103] | |

| 2017, Law 27.424 | Scheme for promoting distributed generation of renewable energy integrated into the electric power grid. The purpose of this law is to set the policies and establish the legal and contractual conditions for the generation of electric energy of renewable origin by users of the distribution network for their self-consumption, with an eventual injection of surpluses to the network, and to establish the obligation of the providers of the public distribution service to facilitate such injection, ensuring free access to the distribution network. | [87,104] | |

| Brazil | 2012, Resolution 482 | National Electric Energy Agency - ANEEL’s Normative Resolution No. 482 establishes the general conditions for the access of distributed microgeneration and mini-generation to electricity distribution systems and the electricity compensation system and makes other provisions. | [105] |

| 2015, Resolution 687 | It improves the previous resolution (Normative Resolution No. 482) by reducing the barriers to the insertion of distributed generation by allowing prosumers to access the distribution system, either individually or in groups (in the form of a condominium, consortium or cooperative, and remote self-consumption). Through the one-to-one net-metering scheme, this norm regulates shared DGs such as condominiums, consortia, and cooperatives. | [88,90,106] | |

| 2022, Law 14.300 | It establishes the legal framework for distributed microgeneration and mini-generation, the Electricity Compensation System (SCEE), and the Social Renewable Energy Program (PERS). It modifies the amount of credit compensation so that distribution costs, representing 30% of the electricity bill, will be deducted. Another meaningful change is that shared generation may be structured in legal forms other than cooperatives and consortiums. In this way, the distributed energy model by subscription may continue to grow in Brazil and adopt other legal forms. | [94,107] | |

| Chile | 2008, Law 20.257 | It introduces amendments to the general law of electric utilities regarding generating electric energy with non-conventional renewable energy sources - NCREs. The first quota regulation specifies that NCREs must supply 10 % of power by 2024. This law was updated in 2013 (Law 20.698) by setting a new quota and deadline of 20 % by 2025. | [28,108] |

| 2012, Law 20.571 | It regulates the payment of electricity tariffs for residential generators. End users subject to pricing who consume electricity generation equipment by non-conventional renewable means or efficient cogeneration facilities for their consumption shall have the right to inject the energy generated in this way into the distribution network through the respective connections. | [28,91,109] | |

| 2018, Law 21.118 | It amends the general law of electric utilities to encourage the development of residential generators. It considers collective on-grid arrangements—on-grid ECs—part of the residential distributed generation cluster. This framework applies to efficient cogeneration or Non-Conventional Renewable Energies (NCREs). Thus, groups of citizens with a shared power generation infrastructure of up to 300 kW can inject electricity into the public grid. | [28,110] | |

| Colombia | 1996, Resolution 84 | The Energy and Gas Regulatory Commission -CREG—regulates the activities of the Auto-generator connected to the National Interconnected System through Resolution 84. | [111] |

| 2014, Law 1715 | The Renewable Energy Law regulates the integration of non-conventional renewable energies into the National Energy System. This law aims to promote the development and use of non-conventional energy sources, storage systems for such sources, and efficient use of energy, mainly renewable ones, in the national energy system. Distributed generation is regulated through two figures: small-scale self-generation and distributed generation. | [94,112] | |

| 2018, Resolution 30 | This CREG resolution regulates small-scale self-generation and distributed generation activities in the National Interconnected System. Resolution CREG 174 of 2021 repealed it. | [94,113] | |

| 2021, Resolution 174 | This CREG resolution regulates operational and commercial aspects to allow the integration of small-scale self-generation and distributed generation into the National Interconnected System (SIN). It also regulates aspects of the connection procedure for large-scale self-generators with a declared maximum power of less than 5 MW. | [94,100,114] | |

| 2023, Law 2294 | It is the Law by which the national development plan 2022- 2026 “Colombia global power of life” is enacted. Article 190 proposes amending Law 1715 to incorporate energy communities. | [94,115] | |

| 2023, Decree 2236 | Partially regulate Article 235 of Law 2294 of 2023 of the National Development Plan 2022 - 2026 concerning the Energy Communities within the framework of the Just Energy Transition in Colombia. | [116] | |

| 2025, Resolution 101 072 | This CREG resolution regulates the integration of energy communities into the National Energy System and issues other provisions for non-interconnected areas. | [117] | |

| Mexico | 2014, Law --- | Energy Industry Law. This law regulates the planning and control of the National Electric System, the Public Service of Transmission and Distribution of Electric Energy, and other activities of the electric industry. The purpose of the law is to promote the sustainable development of the electricity industry and to guarantee its continuous, efficient, and safe operation for the benefit of users, as well as compliance with the obligations of universal public service obligations, Clean Energy, and the reduction of polluting emissions. | [93,118] |

| 2015, Agreement --- | An agreement was reached whereby the Ministry of Energy issued the Electricity Market Bases. The Electricity Market Bases are a regulatory body composed of general administrative provisions that contain the principles for the design and operation of the Wholesale Electricity Market, including the auctions referred to in the Electricity Industry Law. | [93,119] | |

| 2015, Law --- | Energy Transition Law. The law regulates the sustainable use of energy, as well as the obligations regarding clean energies and the reduction of polluting emissions in the electric industry, maintaining the competitiveness of the productive sectors. | [93,120] |

References

- M. L. Lode, G. te Boveldt, T. Coosemans, and L. Ramirez Camargo, “A transition perspective on Energy Communities: A systematic literature review and research agenda,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 163, p. 112479, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.; Ahmed et al., “A Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 5, p. 1749, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Al Katsaprakakis et al., “Greek Islands’ Energy Transition: From Lighthouse Projects to the Emergence of Energy Communities,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 16, p. 5996, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Bauwens et al., “Conceptualizing community in energy systems: A systematic review of 183 definitions,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 156, p. 111999, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Neska and A. Kowalska-Pyzalska, “Conceptual design of energy market topologies for communities and their practical applications in EU: A comparison of three case studies,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 169, p. 112921, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- REN21, “Renewables 2022. Global Status Report,” Paris, 2022.

- REN21, “Renewables 2023 Global Status Report Collection, Global Overview,” 2023.

- P. F. Borowski, “Mitigating Climate Change and the Development of Green Energy versus a Return to Fossil Fuels Due to the Energy Crisis in 2022,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 9289, vol. 15, no. 24, p. 9289, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Gitelman and M. Kozhevnikov, “Energy Transition Manifesto: A Contribution towards the Discourse on the Specifics Amid Energy Crisis,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 9199, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 9199, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Organización Latinoamericana de Energía (OLADE), “Potencial de Energías Renovables en América Latina.” Accessed: May 01, 2025. Available online: https://sielac.olade.org/WebForms/Reportes/ReporteDato3.aspx?oc=61&or=690&ss=2&v=1.

- B. P. González, J. E. Viglio, and L. da Costa Ferreira, “Energy communities in sustainable transitions - The South American Case,” Sustainability in Debate, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 156–174, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Organización Latinoamericana de Energía (OLADE), “Panorama Energético De América Latina Y El Caribe 2023,” 2023.

- L. Gitelman and M. Kozhevnikov, “Energy Transition Manifesto: A Contribution towards the Discourse on the Specifics Amid Energy Crisis,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 9199, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 9199, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Gitelman and M. Kozhevnikov, “New Business Models in the Energy Sector in the Context of Revolutionary Transformations,” Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 3604, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 3604, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Gitelman and M. Kozhevnikov, “New Business Models in the Energy Sector in the Context of Revolutionary Transformations,” Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 3604, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 3604, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Villegas Rodrigues, J.-A. Polanco, and M. Escobar-Sierra, SOSTENIBILIDAD Y PAZ Una memoria empresarial desde el sector eléctrico colombiano. Medellín: Sello Editorial Universidad de Medellín, 2025. Accessed: Aug. 21, 2025. Available online: https://udemedellin.edu.co/lanzamiento-del-libro-sostenibilidad-y-paz/.

- S. M. P. Pulice, E. A. Branco, A. L. C. F. Gallardo, D. R. Roquetti, and E. M. Moretto, “Evaluating Monetary-Based Benefit-Sharing as a Mechanism to Improve Local Human Development and its Importance for Impact Assessment of Hydropower Plants in Brazil,” Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–42, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. I. Sholihah and S. Chen, “Improving living conditions of displacees: A review of the evidence benefit sharing scheme for development induced displacement and resettlement (DIDR) in urban Jakarta Indonesia,” World Dev Perspect, vol. 20, no. July, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Gianaroli, M. Preziosi, M. Ricci, P. Sdringola, M. A. Ancona, and F. Melino, “Exploring the academic landscape of energy communities in Europe: A systematic literature review,” J Clean Prod, vol. 451, p. 141932, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Haji Bashi et al., “A review and mapping exercise of energy community regulatory challenges in European member states based on a survey of collective energy actors,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 172, p. 113055, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tatti, S. Ferroni, M. Ferrando, M. Motta, and F. Causone, “The Emerging Trends of Renewable Energy Communities’ Development in Italy,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 8, p. 6792, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Yiasoumas et al., “Key Aspects and Challenges in the Implementation of Energy Communities,” Energies (Basel), vol. 16, no. 12, p. 4703, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ambole, K. Koranteng, P. Njoroge, and D. L. Luhangala, “A Review of Energy Communities in Sub-Saharan Africa as a Transition Pathway to Energy Democracy,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 4, p. 2128, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- López et al., “European energy communities: Characteristics, trends, business models and legal framework,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 197, p. 114403, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. I. C. Zebra, H. J. van der Windt, B. Olubayo, G. Nhumaio, and A. P. C. Faaij, “Scaling up the electricity access and addressing best strategies for a sustainable operation of an existing solar PV mini-grid: A case study of Mavumira village in Mozambique,” Energy for Sustainable Development, vol. 72, pp. 58–82, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Come Zebra, H. J. van der Windt, G. Nhumaio, and A. P. C. Faaij, “A review of hybrid renewable energy systems in mini-grids for off-grid electrification in developing countries,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 144, p. 111036, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Montedonico, F. Herrera-Neira, A. Marconi, A. Urquiza, and R. Palma-Behnke, “Co-construction of energy solutions: Lessons learned from experiences in Chile,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 45, pp. 173–183, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Poque González, J. E. Viglio, Y. M. Macia, and L. da Costa Ferreira, “Redistributing power? Comparing the electrical system experiences in Chile and Brazil from a historical institutional perspective,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 101, p. 103129, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Roa-Avendaño, Energías para la transición. Reflexiones y relatos, no. marzo. Bogotá: Censat Agua Viva y Fundación Heinrich Boll, 2021.

- Teladia and H. van der Windt, “Lights, Policy, Action: A Multi-Level Perspective on Policy Instrument Mix Interactions for Community Energy Initiatives,” Energies 2025, Vol. 18, Page 2823, vol. 18, no. 11, p. 2823, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Geels, “Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study,” Res Policy, vol. 31, no. 8–9, pp. 1257–1274, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Magnani and V. M. Cittati, “Combining the Multilevel Perspective and Socio-Technical Imaginaries in the Study of Community Energy,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Lode, G. te Boveldt, T. Coosemans, and L. Ramirez Camargo, “A transition perspective on Energy Communities: A systematic literature review and research agenda,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 163, p. 112479, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Inchima, J.-A. Polanco, and M. Escobar-Sierra, “Good living of communities and sustainability of the hydropower business: mapping an operational framework for benefit sharing,” Energy, Sustainability and Society 2021 11:1, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–20, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Suárez-Gómez, J.-A. Polanco, and M. Escobar-Sierra, “Understanding the role of territorial factors in the large-scale hydropower business sustainability: A systematic literature review,” Energy Reports, vol. 7, pp. 3249–3266, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Adu-Kankam and L. M. Camarinha-Matos, “Renewable energy communities or ecosystems: An analysis of selected cases,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 12, p. e12617, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Geels, F. Kern, and W. C. Clark, “Sustainability transitions in consumption-production systems,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 120, no. 47, p. e2310070120, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Narjabadifam, J. Fouladvand, and M. Gül, “Critical Review on Community-Shared Solar—Advantages, Challenges, and Future Directions,” Energies (Basel), vol. 16, no. 8, p. 3412, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Geels, “Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: a review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective,” Curr Opin Environ Sustain, vol. 39, pp. 187–201, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Berlo, O. Wagner, and M. Heenen, “The Incumbents’ Conservation Strategies in the German Energy Regime as an Impediment to Re-Municipalization—An Analysis Guided by the Multi-Level Perspective,” Sustainability 2017, Vol. 9, Page 53, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 53, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Geels, “Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study,” Res Policy, vol. 31, no. 8–9, pp. 1257–1274, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Hamann et al., “An interdisciplinary understanding of energy citizenship: Integrating psychological, legal, and economic perspectives on a citizen-centred sustainable energy transition,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 97, p. 102959, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Dóci, E. Vasileiadou, and A. C. Petersen, “Exploring the transition potential of renewable energy communities,” Futures, vol. 66, pp. 85–95, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Musolino and D. Farinella, “Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy,” Land (Basel), vol. 14, no. 3, p. 603, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. van Eck and L. Waltman, “Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping,” Scientometrics, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 523–538, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Van Eck and L. Waltman, “Accuracy of citation data in Web of Science and Scopus,” J Organomet Chem, vol. 798, pp. 229–233, 2015.

- Waltman, N. J. van Eck, and E. C. M. Noyons, “A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks,” J Informetr, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 629–635, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Van Eck and L. Waltman, Visualizing Bibliometric Networks. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Moher et al., “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement,” Aug. 2009, American College of Physicians. [CrossRef]

- Wahlund and J. Palm, “The role of energy democracy and energy citizenship for participatory energy transitions: A comprehensive review,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 87, p. 102482, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Barabino et al., “Energy Communities: A review on trends, energy system modelling, business models, and optimisation objectives,” Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, vol. 36, p. 101187, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F.G. Reis, I. Gonçalves, M. A.R. Lopes, and C. Henggeler Antunes, “Business models for energy communities: A review of key issues and trends,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 144, p. 111013, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Casamassima, L. Bottecchia, A. Bruck, L. Kranzl, and R. Haas, “Economic, social, and environmental aspects of Positive Energy Districts—A review,” WIREs: Energy and Environment, vol. 11, no. 6, p. e452, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Kazmi, Í. Munné-Collado, F. Mehmood, T. A. Syed, and J. Driesen, “Towards data-driven energy communities: A review of open-source datasets, models and tools,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 148, p. 111290, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Hoicka, J. Lowitzsch, M. C. Brisbois, A. Kumar, and L. Ramirez Camargo, “Implementing a just renewable energy transition: Policy advice for transposing the new European rules for renewable energy communities,” Energy Policy, vol. 156, p. 112435, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Papatsounis, P. N. Botsaris, and S. Katsavounis, “Thermal/Cooling Energy on Local Energy Communities: A Critical Review,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, p. 1117, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lowitzsch, C. E. Hoicka, and F. J. van Tulder, “Renewable energy communities under the 2019 European Clean Energy Package – Governance model for the energy clusters of the future?,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 122, p. 109489, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Guetlein and J. Schleich, “Empirical insights into enabling and impeding factors for increasing citizen investments in renewable energy communities,” Energy Policy, vol. 193, p. 114302, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li and Ö. Okur, “Economic analysis of energy communities: Investment options and cost allocation,” Appl Energy, vol. 336, p. 120706, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Moretti and E. Stamponi, “The Renewable Energy Communities in Italy and the Role of Public Administrations: The Experience of the Municipality of Assisi between Challenges and Opportunities,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 15, p. 11869, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Martens, “Investigating subnational success conditions to foster renewable energy community co-operatives,” Energy Policy, vol. 162, p. 112796, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- De Vidovich, “Niches Seeking Legitimacy: Notes about Social Innovation and Forms of Social Enterprise in the Italian Renewable Energy Communities,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 9, p. 3599, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea, “RepowerEU - Comisión Europea,” Bruselas, 2022.

- European Commission, “Clean energy for all Europeans package.” Accessed: Oct. 14, 2024. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans-package_en.

- F. Barroco Fontes Cunha et al., “Renewable energy planning policy for the reduction of poverty in Brazil: lessons from Juazeiro,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 9792–9810, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Barbaro and G. Napoli, “Energy Communities in Urban Areas: Comparison of Energy Strategy and Economic Feasibility in Italy and Spain,” Land (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1282, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- De Vidovich, L. Tricarico, and M. Zulianello, “How Can We Frame Energy Communities’ Organisational Models? Insights from the Research ‘Community Energy Map’ in the Italian Context,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 3, p. 1997, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Musolino, G. Maggio, E. D’Aleo, and A. Nicita, “Three case studies to explore relevant features of emerging renewable energy communities in Italy,” Renew Energy, vol. 210, pp. 540–555, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Heuninckx, G. te Boveldt, C. Macharis, and T. Coosemans, “Stakeholder objectives for joining an energy community: Flemish case studies,” Energy Policy, vol. 162, p. 112808, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dudka, N. Moratal, and T. Bauwens, “A typology of community-based energy citizenship: An analysis of the ownership structure and institutional logics of 164 energy communities in France,” Energy Policy, vol. 178, p. 113588, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pena-Bello, D. Parra, M. Herberz, V. Tiefenbeck, M. K. Patel, and U. J. J. Hahnel, “Integration of prosumer peer-to-peer trading decisions into energy community modelling,” Nat Energy, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 74–82, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Conradie, O. De Ruyck, J. Saldien, and K. Ponnet, “Who wants to join a renewable energy community in Flanders? Applying an extended model of Theory of Planned Behaviour to understand intent to participate,” Energy Policy, vol. 151, p. 112121, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Toderean, V. R. Chifu, T. Cioara, I. Anghel, and C. B. Pop, “Cooperative Games Over Blockchain and Smart Contracts for Self-Sufficient Energy Communities,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 73982–73999, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Radtke, Ö. Yildiz, and L. Roth, “Does Energy Community Membership Change Sustainable Attitudes and Behavioral Patterns? Empirical Evidence from Community Wind Energy in Germany,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, p. 822, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Nozarian, A. Fereidunian, and M. Barati, “Smart City Energy Infrastructure as a Cyber-Physical System of Systems: Planning, Operation, and Control Processes,” Smart Cyber-Physical Power Systems: Fundamental Concepts, Challenges, and Solutions, pp. 99–123, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Nozarian, A. Fereidunian, and M. Barati, “Reliability-Oriented Planning Framework for Smart Cities: From Interconnected Micro Energy Hubs to Macro Energy Hub Scale,” IEEE Syst J, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 3798–3809, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. F. M. van Summeren, S. Breukers, and A. J. Wieczorek, “Together we’re smart! Flemish and Dutch energy communities’ replication strategies in smart grid experiments,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 89, p. 102643, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Y. Wu, H. Cimen, J. C. Vasquez, and J. M. Guerrero, “Towards collective energy Community: Potential roles of microgrid and blockchain to go beyond P2P energy trading,” Appl Energy, vol. 314, p. 119003, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Galindo Noguera, L. S. Mendoza Castellanos, S. Ardila Cruz, and G. Osorio-Gómez, “Key aspects and challenges for successful energy communities: A comparative analysis between Latin America and developed countries,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 216, p. 115687, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Poque González, A. S. Silvino, Y. M. Macia, and L. da Costa Ferreira, “Institutional conditions for the development of energy communities in Chile and Brazil,” Sustainability in Debate, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 88–121, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lampis and C. Bermann, “Public Policy and Governance Narratives of Distributed Energy Resources in Brazil,” Ambiente & Sociedade, vol. 25, p. e01132, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Barroco Fontes Cunha, C. Carani, C. A. Nucci, C. Castro, M. Santana Silva, and E. Andrade Torres, “Transitioning to a low carbon society through energy communities: Lessons learned from Brazil and Italy,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 75, p. 101994, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Cárdenas Álvarez, J. George, J. Giraldo Quiroz, J. A. Estrada Walker, J. M. España Forero, and S. Ortega Arango, “REDEFINIENDO LAS COMUNIDADES ENERGÉTICAS PARA UNA TRANSICIÓN JUSTA. Una visión crítica sobre la Comunidad Solar La Estrecha en Medellín, Colombia,” 2023.

- Lampis et al., “Energy transition or energy diversification? Critical thoughts from Argentina and Brazil,” Energy Policy, vol. 171, p. 113246, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Palma-Behnke et al., “Lowering Electricity Access Barriers by Means of Participative Processes Applied to Microgrid Solutions: The Chilean Case,” in Proceedings of the IEEE, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Sep. 2019, pp. 1857–1871. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Garrido, “‘Por un futuro sustentable y una gestión democrática de la energía’: la experiencia de construir un sistema de generación alternativa en la ciudad de Armstrong, Argentina,” Estudios Avanzados, no. 29, pp. 40–55, 2018.

- M. Kazimierski, “La energía distribuida como modelo post-fósil en Argentina,” Economía, sociedad y territorio, vol. 20, no. 63, pp. 397–428, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Schneider, M. O. M. de Oliveira, C. Japp, P. S. Manoel, and R. Rüther, “Community solar in Brazil: The cooperative model context and the existing shared solar cooperatives up to date,” in Proceedings of the ISES Solar World Congress 2019 and IEA SHC International Conference on Solar Heating and Cooling for Buildings and Industry 2019, 2019, pp. 1594–1605. [CrossRef]

- F. Fuentes González, E. Sauma, and A. H. van der Weijde, “The Scottish experience in community energy development: A starting point for Chile,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 113, p. 109239, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Lotero and H. F. De Souza, “Optimal Selection of Photovoltaic Generation for a Community of Electricity Prosumers,” IEEE Latin America Transactions, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 791–799, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Fuentes González, A. H. van der Weijde, and E. Sauma, “The promotion of community energy projects in Chile and Scotland: An economic approach using biform games,” Energy Econ, vol. 86, p. 104677, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Galván et al., “Exporting sunshine: Planning South America’s electricity transition with green hydrogen,” Appl Energy, vol. 325, p. 119569, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Magar, A. Peña, A. N. Hahmann, D. A. Pacheco-Rojas, L. S. García-Hernández, and M. S. Gross, “Wind Energy and the Energy Transition: Challenges and Opportunities for Mexico,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 6, p. 5496, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ramírez-Tovar and K. Scheinder, “Por más, y por menos, comunidades energéticas en la generación ciudadana: diálogo entre las regulaciones brasileña y colombiana,” Energía y equidad, no. 6, pp. 14–25, 2023.

- R. Rodríguez and A. J. Anuzis, “POTENCIALIDAD PARA LA IMPLEMENTACIÓN DE COMUNIDADES ENERGÉTICAS SUSTENTABLES EN LA PROVINCIA DE CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA,” ENERLAC. Revista de Energía de Latinoamérica y el Caribe, vol. V, no. 2, 2021.

- Ramirez-Tovar, J. España, L. Restrepo, and J. Giraldo, “Barreras Regulatorias Para La Implementación De Comunidades Energéticas En Colombia,” 2022.

- J. Molina Castro, L. F. Buitagro, S. Téllez, S. Giraldo, and J. Zapata, “Comunidades Energéticas: Modelos para el empoderamiento de los usuarios en Colombia,” ENERLAC. Revista De energía De Latinoamérica Y El Caribe, vol. VII, no. 1, pp. 110–133, 2023.

- J. P. Cárdenas Álvarez, J. George, J. Giraldo Quiroz, J. A. Estrada Walker, J. M. España Forero, and S. Ortega Arango, “Recomendaciones para el desarrollo de comunidades energéticas en Colombia-Policy brief,” 2023.

- DGRV, Fotovoltaica UFSC, Universidad EIA, and Energeia, “Energia.Coop. Plataforma de energía cooperativa.” Accessed: Aug. 06, 2024. Available online: https://www2.energia.coop/.

- J. Tejada Medina and S. E. Baquero Vides, “Comunidades energéticas en Colombia: un enfoque jurídico para la sostenibilidad y la participación ciudadana en el ámbito de la transición energética,” Universidad EAFIT, 2023.

- Ministerio de Justicia de la Nación, “Ley 25.019.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/50000-54999/53790/texact.htm.

- Boletín Oficial República Argentina, “Ley 26.190.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/ley_26190-2006.pdf.

- Ministerio de Justicia de la Nación, “Ley 27.191.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/250000-254999/253626/norma.htm.

- Ministerio de Justicia de la Nación, “Ley 27.424.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/305000-309999/305179/norma.htm.

- AGÊNCIA NACIONAL DE ENERGIA ELÉTRICA – ANEEL, “RESOLUÇÃO NORMATIVA No 482.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://solistec.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RN-482-2012.pdf.

- AGÊNCIA NACIONAL DE ENERGIA ELÉTRICA – ANEEL, “RESOLUÇÃO NORMATIVA No 687.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://solistec.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RN-687-2015.pdf.

- Diario Oficial da Union, “LEI No 14.300.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://pesquisa.in.gov.br/imprensa/jsp/visualiza/index.jsp?jornal=515&pagina=4&data=07/01/2022.

- Ministerio de Economía, “Ley 20257.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=270212.

- Ministerio de Energía, “Ley 20571.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1038211.

- Ministerio de Energía, “Ley 21118.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1125560.

- Comisión de Regulación de Energía y Gas - CREG, “Resolución 84 de 1996.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://gestornormativo.creg.gov.co/gestor/entorno/docs/resolucion_creg_0084_1996.htm.

- Ministerio de Minas y Energía, “Ley 1715 de 2014.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=57353.

- Comisión de Regulación de Energía y Gas - CREG, “Resolución 030 de 2018.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://gestornormativo.creg.gov.co/gestor/entorno/docs/resolucion_creg_0030_2018.htm.

- Comisión de Regulación de Energía y Gas - CREG, “Resolución 174 de 2021.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://gestornormativo.creg.gov.co/gestor/entorno/docs/resolucion_creg_0174_2021.htm.

- Congreso de Colombia, “Ley 2294 de 2023.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=209510.

- Ministerio de Minas y Energía, “Decreto 2236 de 2023 sobre comunidades energéticas en Colombia.” Accessed: Apr. 30, 2025. Available online: https://normativame.minenergia.gov.co/normatividad/6821/norma/.

- Comisión de Regulación de Energía y Gas - CREG, “Resolución 101 072 sobre comunidades energéticas en Colombia.” Accessed: Apr. 30, 2025. Available online: https://creg.gov.co/loader.php?lServicio=Documentos&lFuncion=infoCategoriaConsumo&tipo=RE.

- Congreso de los Estados Mexicanos, “Ley de la Industria Eléctrica.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LIElec.pdf.

- Gobierno de México, “Acuerdo por el que la Secretaría de Energía emite las Bases del Mercado Eléctrico.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5407715&fecha=08/09/2015.

- Congreso de los Estados Mexicanos, “Ley de la Transición Energética.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LTE.pdf.

| Levels of Analysis | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Macro Level - Landscape | It consists of a set of structural trends that define the societal context. It is an external structure of broader technological factors that is difficult to change. | Climate change, Energy prices, economic growth, wars, emigration, broad political coalitions, cultural and normative values, and environmental problems. |

| Meso Level – Regimes | It refers to the rules created by different social groups, which orient and coordinate activities. It stabilizes existing socio-technical configurations, allowing innovation to occur incrementally. It encompasses culture, symbolic meaning, sectoral policies, markets, and user practices, among other factors. | Centralized Fossil Fuel-Based Electricity Regime; Utility-Centered Business Model Regime, etc. |

| Micro Level - Niche | It forms “protected spaces” that shield radical innovations from competition with dominant practices, thus encouraging pioneering activities by new entrants, such as inventors, start-ups, or grassroots players. It provides the space for learning processes and social networks that support innovation, such as supply chains and user-producer relationships. | Renewable energy generation technologies (solar, wind, biomass), energy storage systems, electric vehicles, etc. |

| Reference Source | Search String | Results |

| Scopus and Web of Science | “energy community” OR “energy communities” AND “energy transition*” AND (“energy polic*” OR sustain* OR “sustainable development” OR “renewable energ*”) | 79 |

| Scopus and Web of Science | Snowball technic | 12 |

| Google Scholar | allintitle: “América Latina” OR Latinoamérica OR argentina OR bolivia OR ecuador OR uruguay OR paraguay OR venezuela OR colombia OR méxico OR brasil OR chile OR “costa rica” OR perú “comunidades energéticas” | 13 |

| TOTAL | 104 |

| Cluster | Keywords | Co-Occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | energy transition, energy policy, alternative energy, renewable energy, European union, community energy, energy market, Europe, energy justice, energy democracy, energy resources, Germany, energy citizenship, Netherlands, Spain | 525 (22%) |

| 2 | renewable energy resources, local energy, prosumer, power markets, smart grid, business models, local energy community, microgrid, smart power grids, commerce, laws and legislation, electric batteries, energy markets, electricity generation, prosumers, battery storage | 341 (14%) |

| 3 | renewable energies, investments, climate change, energy utilization, energy management, energy systems, solar energy, optimization, economic analysis, fossil fuels, environmental impact, optimizations, electric energy storage, energy planning, solar power generation, wind power, energy security | 346 (15%) |

| 4 | renewable energy source, sustainability, Italy, renewable energy sources, profitability, energy use, housing, buildings, collective self-consumption, decarbonization, photovoltaic system, regulatory framework, regulatory frameworks, renewables | 194 (8%) |

| 5 | Energy, energy community, energy communities, sustainable development, decision making, sustainable energy, energy sector, energy conservation, innovation, photovoltaics | 496 (21%) |

| 6 | energy transitions, community is, energy efficiency, greenhouse gases, economic and social effects, self-consumption, blockchain, clean energy, gas emissions, natural resources | 297 (13%) |

| 7 | renewable energy community, renewable energy communities, case studies, economics, citizen energy community, citizen energy communities, renewable energy directive | 166 (7%) |

| Issues | Definitions |

|---|---|

| 1. Energy community definitions | Process, identity, technology, typology, legal structure, activities and objectives |

| 2. Business and economics | Electricity market design, Business models (BMs), pricing, and benefits distribution |

| 3. Regulatory and institutional | Formal and informal rules for EC governance, such as legislation, support mechanisms, and cultural practices |

| 4. Socio-political | Participation in decision-making, social acceptance, and willingness to join EC projects. |

| 5. Technical | Energy sources and technologies, EC structures and networking, and information and communication technologies (ICT) |

| Three Levels of Analysis | On-grid ECs Topics | Barriers to Energy Transition |

| Macro Level-Landscape |

|

|

| Meso Level-Regimes |

|

|

| Micro Level-Niches |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).