Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design

Instrument

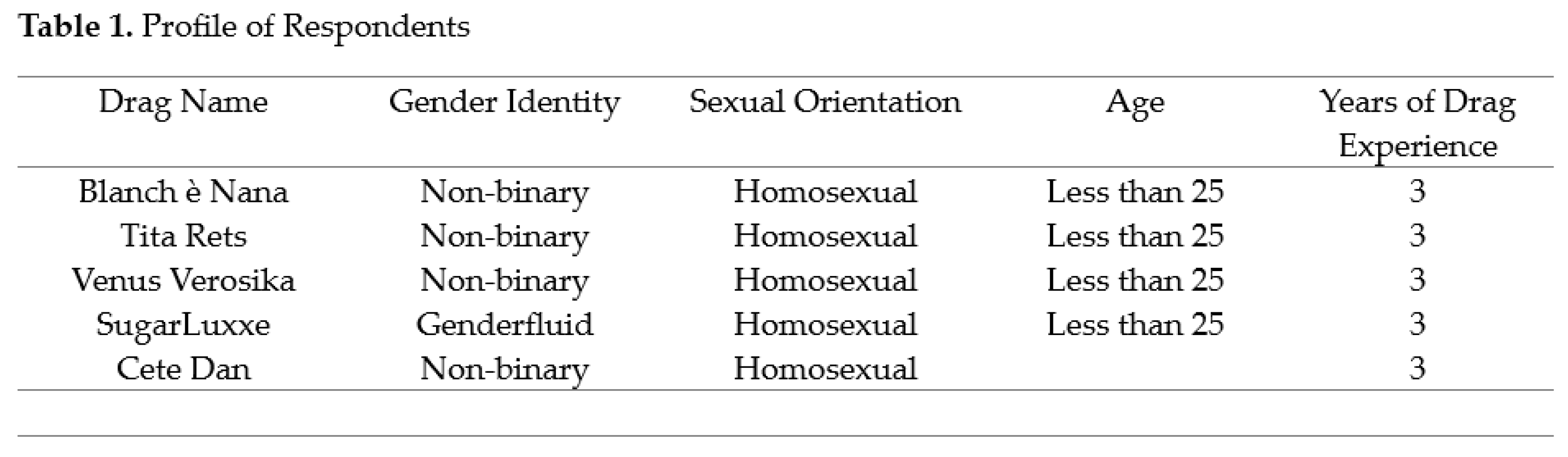

Research Informants

Data Collection Procedure

Data Analysis

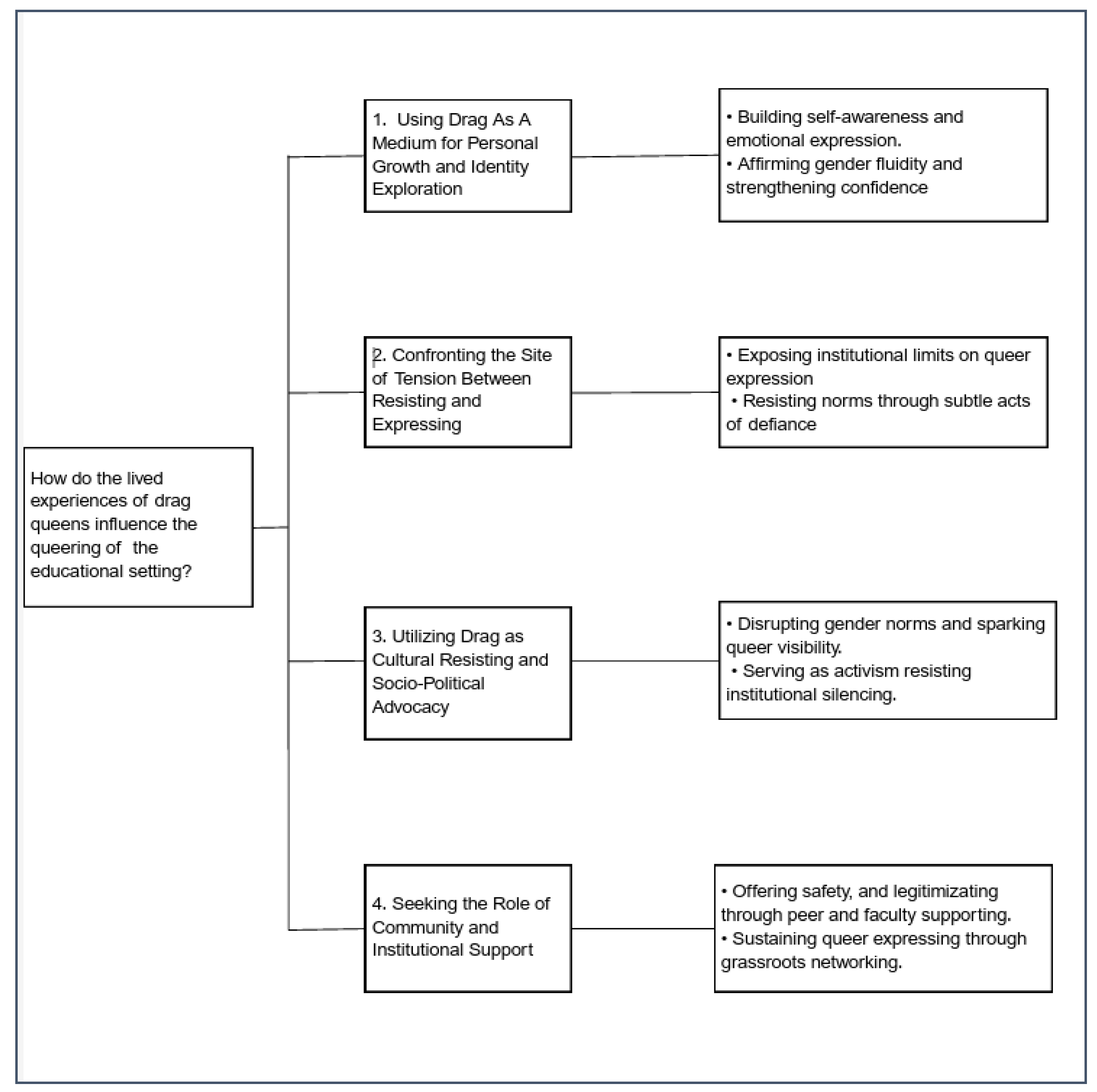

3. Results

Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkowitz, D., Belgrave, L., & Halberstein, R. A. (2007). The Interaction of Drag Queens and Gay Men in Public and Private Spaces. Journal of Homosexuality, 52(3-4), 11–32. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N., & Gudelunas, D. (2023). Drag in the global digital public sphere: queer visibility, online discourse and political change. Routledge.

- Burnes, T. R. , & Stanley, J. L. (2017). Teaching LGBTQ psychology: queering innovative pedagogy and practice. American Psychological Association.

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Vol. Volume 1, Chapter 12, Page 159-172, (pp. 89–6438). Routledge. https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/en/publications/drag-kings-and-queens-of-higher-education? (Original work published 1990).

- Craig, S. L., Eaton, A. D., McInroy, L. B., Leung, V. W. Y., & Krishnan, S. (2021). Can Social Media Participation Enhance LGBTQ+ Youth Well-Being? Development of the Social Media Benefits Scale. Social Media + Society, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- EDWARD, M. (2020). Drag Kings and Queens of Higher Education. Edge Hill University, Volume 1, Chapter 12, Page 159-172,(9781350082953), 159 172. Contemporary Drag Practices & Performers. https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/en/publications/drag-kings-and-queens-of-higher-education?

- Edward, M., & Farrier, S. (2020). Contemporary Drag Practices and Performers: Vol. Drag in a Changing Scene Volume 1 (1st Edition). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Eric Darnell Pritchard. (2017). Fashioning Lives: black queers and the Politics of Literacy (pp. 306). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Galyna Kotliuk. (2023). Gender on Stage: Drag Queens and Performative Femininity. Scientific Notes of Ternopil National Pedagogical University (Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University), Volume 7, Issue 1, 8–14. International Journal of European Studies. [CrossRef]

- Greaf, C. (2015). Drag queens and gender identity. Journal of Gender Studies, 25(6), 655–665. [CrossRef]

- Halberstam, J. (1998). Female masculinity: Vol. Volume 1, Chapter 12, Page 159-172, (p. 360). Duke University Press. https://www.dukeupress.edu/female-masculinity-twentieth-anniversary-edition.

- J. Greteman, A. (2022). Queers Teach This! Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. [CrossRef]

- José Esteban Muñoz. (2019). Disidentifications. U of Minnesota Press.

- Kavka, M. (2018). Reality TV: Its contents and discontents. Critical Quarterly, 60(4), 5–18. [CrossRef]

- Keenan, H., & Hot Mess, L. M. (2021). Drag pedagogy: The playful practice of queer imagination in early childhood. Curriculum Inquiry, 50(5), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Knutson, D., Koch, J. M., Sneed, J., & Lee, A. (2018). The Emotional and Psychological Experiences of Drag Performers: A Qualitative Study. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 12(1), 32–50. [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., Zongrone, A. D., & Glsen, G. (1000). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. A Report from GLSEN. Gay, Lesbian, And Straight Education Network (GLSEN). 121 West 27Th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 1. Tel: 212-727-; Fax: 212-727-; E-Mail: Glsen@Glsen.org; Web Site: Http://Www.Glsen.org -00-00.

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2024). Against Common Sense: Teaching and Learning Toward Social Justice.

- Martino, W. (2022). Supporting Transgender Students and Gender-Expansive Education in Schools: Investigating Policy, Pedagogy, and Curricular Implications. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 124(8), 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Martino, W., & Cumming-Potvin, W. (2018). Transgender and gender expansive education research, policy and practice: reflecting on epistemological and ontological possibilities of bodily becoming. Gender and Education, 30(6), 687–694. [CrossRef]

- McBride, R.-S., & Neary, A. (2021). Trans and gender diverse youth resisting cisnormativity in school. Gender and Education, 33(8), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- McBrien, J., Rutigliano, A., & Sticca, A. (2022). The Inclusion of LGBTQI+ students across education systems. OECD Education Working Papers. [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. [CrossRef]

- Nast, C. (2022, June 30). Targeting Drag Queens in Classrooms Is a “War on Imagination.” Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/drag-queens-in-the-classroom.

- Niall Brennan, & Gudelunas, D. (2017). RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Shifting Visibility of Drag Culture: the Boundaries of Reality TV (1st ed., pp. XIII, 309). Springer International Publishing. https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/en/publications/drag-kings-and-queens-of-higher-education? (Original work published in 2017).

- Open Society Foundations. (2019, April). Understanding Sex Work in an Open Society. Understanding Sex Work in an Open Society. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/understanding-sex-work-open-society.

- Puar, J. K. (2017). The Right to Maim. Duke University Press. [CrossRef]

- Sears, J. T. (2023). Symbolic inclusion in queer education: A call for actionable support. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 14(1), 48–63. 14(1), 48–63.

- Snapp, S. D., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Diaz, R. M., & Ryan, C. (2019). Social Support Networks for LGBT Young Adults: Low-Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment. Family Relations, 64(3), 420–430. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V., & Rupp, L. J. (2004). Chicks with Dicks, Men in Dresses. Journal of Homosexuality, 46(3-4), 113–133. [CrossRef]

- The Christian Institute. (2023, September 25). What are drag queens doing in schools? Christian.org.uk. https://www.christian.org.uk/features/what-are-drag-queens-doing-in-schools/.

- Torr, D., & Bottoms, S. J. (2010). Sex, drag, and male roles: investigating gender as performance. University Of Michigan Press.

- Toynton, R. (2006). “Invisible other” Understanding safe spaces for queer learners and teachers in adult education. Studies in the Education of Adults, 38(2), 178–194. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).