1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory bowel disease characterized by a dysregulated immune response and persistent mucosal inflammation [

1,

2,

3]. Its rising global prevalence poses a significant clinical challenge, compounded by the limitations of current therapies [

4,

5]. Mainstay treatments like corticosteroids and immunosuppressants often cause broad systemic side effects, while biologic agents face issues with primary non-response and loss of efficacy [

6,

7]. This highlights a critical unmet need for novel strategies that can enhance drug delivery specifically to the site of inflammation, thereby maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity.

A promising strategy involves engineering drug delivery system with multi-functional capabilities tailored to the pathological microenvironment of UC. The inflamed colon is characterized by two key features: a massive infiltration of activated macrophages and a state of intense oxidative stress marked by excessive reactive oxygen species [

8,

9,

10]. This pathological landscape provides dual targets for smart drug delivery through a cellular target via receptors overexpressed on macrophages, and a chemical target via the abundant ROS.

To exploit the cellular target, the folate receptor represents a compelling target, as it is minimally expressed under physiological conditions but markedly upregulated on activated macrophages in inflamed tissues [

11,

12,

13]. FA conjugation offers a well-established route to target these cells [

14,

15,

16]. To exploit the chemical target, a ROS-sensitive carrier can be designed to enhance site-specific drug release and prolong therapeutic action at inflamed tissues, thereby overcoming the current challenges of poor accumulation and rapid clearance in ulcerative colitis treatment [

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, to address the poor pharmacokinetic profile of many potent therapeutic compounds, a system capable of providing sustained release is essential for maintaining effective local drug concentrations [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Ferulic acid, a natural polyphenol with proven antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, is an ideal drug candidate for UC treatment [

24,

25,

26]. However, its clinical translation is severely limited by poor aqueous solubility, low bioavailability, and rapid systemic clearance [

27,

28]. To overcome these hurdles, a covalent cyclodextrin organic framework (COF) represents a versatile encapsulation platform, offering high porosity, excellent stability, and the ability to be engineered for specific functions [

29,

30,

31].

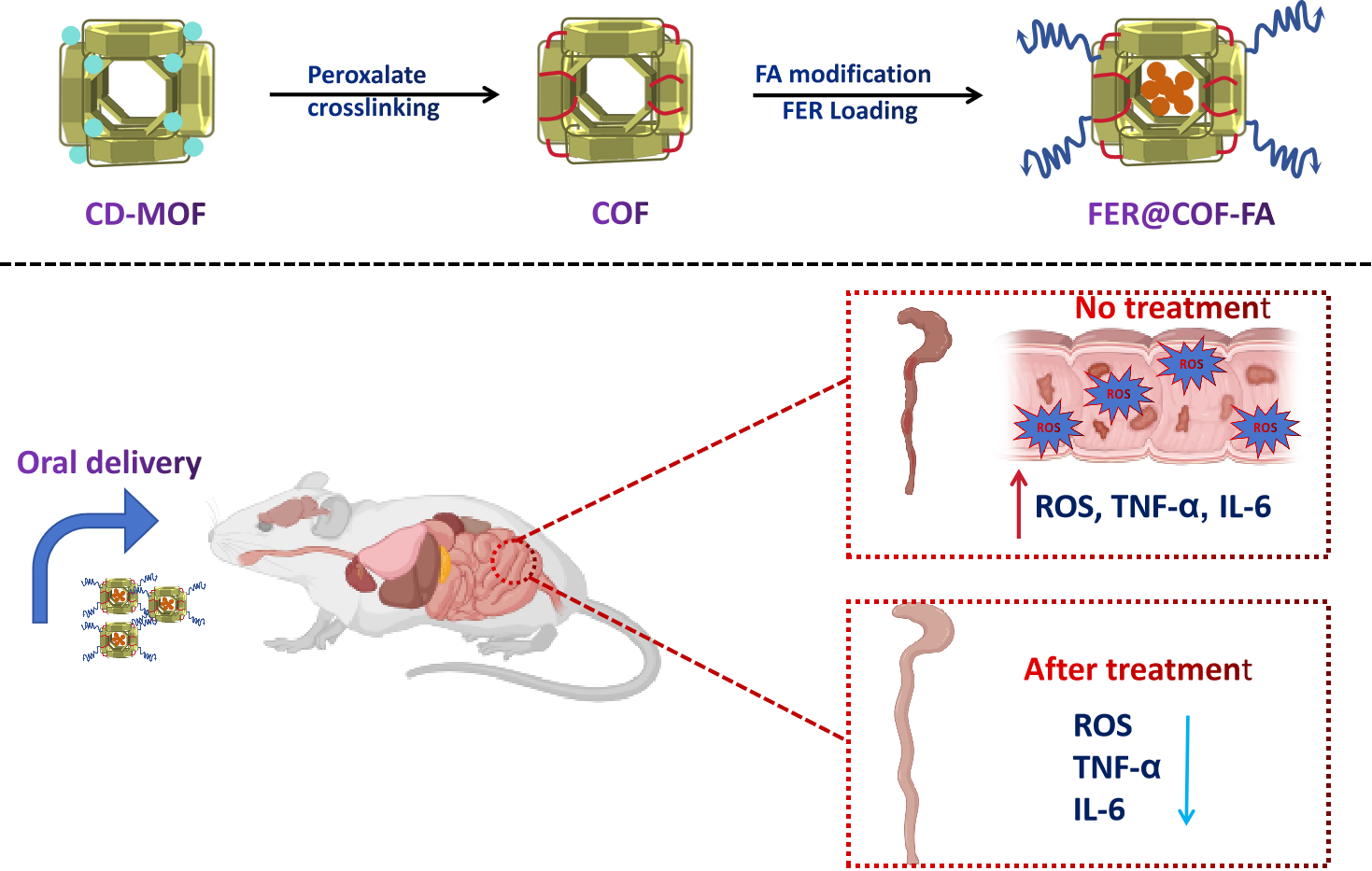

This study presents the rational design and evaluation of a multi-functional carrier system that synergistically combines three therapeutic strategies into a single platform. A ROS-sensitive, cyclodextrin-based COF was synthesized and functionalized with folic acid (COF-FA) to create a carrier designed for: (1) sustained release of its payload from the porous COF matrix, (2) intrinsic ROS-scavenging activity through the hydrolysis of its oxalate bonds in the inflammatory microenvironment, and (3) potential active targeting of activated macrophages exploiting folate-mediated uptake. This carrier was subsequently loaded with ferulic acid to form FER@COF-FA.

The system was comprehensively characterized, confirming its successful synthesis, ROS-scavenging capability, and sustained drug release profile in vitro. The therapeutic efficacy was then rigorously evaluated in a murine model of DSS-induced colitis. Results demonstrate that FER@COF-FA significantly outperforms free FER, providing superior alleviation of disease activity, prevention of colon shortening, normalization of systemic inflammation, and restoration of healthy cytokine balance. The significantly enhanced outcomes align with the design hypothesis, suggesting successful receptor-mediated targeting and highlighting the advantage of a multi-mechanistic approach. This work establishes FER@COF-FA as a highly promising and sophisticated platform for the targeted treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases.

2. Method

2.1. Materials

γ-Cyclodextrin (γ-CD) was sourced from Maxdragon Biochem Ltd. (China). Analytical-grade reagents including potassium hydroxide (KOH), polyethylene glycol 20000 (PEG 20000), monopotassium phosphate, ethanol, and methanol were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Oxalyl chloride (98%, from Aladdin Biochemical Technology), anhydrous dichloromethane (Batch: LC60X04, from Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology), and triethylamine (Batch: P3066131, from Shanghai Titan Scientific). Additionally sourced were: anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (99.9%, Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology), anhydrous ethanol (99.9%, Shanghai Titan Scientific), folic acid (Batch: P2743040, Shanghai Titan Scientific), N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (99.0%, Shanghai Macklin Biochemical), and ferulic acid (Batch: F2428189, Aladdin Biochemical Technology). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Fetal bovine serum (FBS), and CCK-8 were procured from Solarbio Science and Technology Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All chemicals were commercially available and used without further purification.

2.2. Micro γ-CD-MOF Preparation

The CD-MOF was prepared using modified hydrothermal method according to the reported literature [

32]. Microscale γ-CD-MOF crystals were synthesized from γ-cyclodextrin and KOH at 1:8 molar ratio. Methanol was added at 50 °C, followed by PEG 20,000 as a stabilizer. The mixture was cooled to 15 °C overnight to precipitate cubic crystals, which were then thoroughly washed with ethanol and vacuum-dried at 45 °C for 12 hours.

2.3. Synthesis of ROS-Sensitive Crosslinked Cyclodextrin Framework

COF was synthesized using CD-MOF powder and oxalyl chloride (OC) as a crosslinker [

29]. Briefly, CD-MOF (1.5 g) was weighed into a single-neck round-bottom flask, followed by the addition of anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM, 15 mL). After ultrasonic agitation, the mixture was stirred under ice condition. Additionally, triethylamine (TEA, 0.5 mL) was introduced as a catalyst, and the flask was evacuated three times to establish a nitrogen atmosphere. Subsequently, 0.55 mL of OC dissolved in 2.5 mL of anhydrous dichloromethane was slowly injected into the reaction system via a rubber tube connected to the flask’s stopcock to prevent air ingress. The reaction proceeded overnight under nitrogen at 25℃. The product obtained was washed twice with a series of absolute ethanol, ethanol-water, and pure water to eliminate the unreacted OC. Finally, the centrifuged product was lyophilized to obtain COF.

2.4. Ferulic Acid Incorporation

Briefly, FER (400 mg) was dissolved in 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol via ultrasonication. COF (100 mg) was added, and the mixture was magnetically stirred at 37 °C (400 rpm) for 6 h in the dark. The obtained product was centrifuged to remove the supernatant, washed three times with anhydrous ethanol to eliminate surface-adsorbed FER, and vacuum-dried at 45 °C for 5 h to obtain FER@COF particles.

To determine the drug loading percent (%), FER@COF (5 mg) was dissolved in ultrapure water, diluted to 10 mL, and allowed to stand until complete dissolution. A 1 mL aliquot was diluted to 10 mL, sonicated for 5 min, and analyzed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry to determine FER loading.

2.5. Folic Acid Functionalized ROS-Sensitive COF

FA (0.51 g) was dissolved in 25 mL of anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a round-bottom flask with the aid of sonication. N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.8 g) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.5 g) were then added to the FA/DMSO solution and stirred for 4 h to activate carboxyl groups [

33]. COF and FER@COF powder were then introduced to the activated FA mixture, and the reaction was carried out in the dark for 24 h. The product precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed three times with anhydrous ethanol and water. The obtained product was then lyophilized and stored overnight to yield COF-FA and FER@COF powder. The concentrations of FER in the resulting product were measured by HPLC.

2.6. Physicochemical Characterization

The morphological features of COF, COF-FA, and FER@COF-FA were examined using SEM (TESCAN MIRA LMS, Czech Republic), and the elemental constituents of the samples were investigated using elemental mapping. The crystallinity of the samples before and after crosslinking was investigated using powder X-ray diffractometry (PXRD). FTIR spectra were acquired over 4000–400 cm⁻¹ at 1 cm⁻¹ resolution. Briefly, samples of COF, FER, FA, COF-FA, and FER@COF-FA (1:100 mass ratio to KBr) were homogenized in an agate mortar and pressed into pellets. The thermal stability of FER, COF-FA, and FER@COF-FA was analyzed using a TG-DSC instrument (Netzsch STA 449 F3, Germany) from 30°C to 600°C at 20°C/min under nitrogen.

2.7. In Vitro Antioxidant Capability of COF-FA

The H₂O₂ scavenging ability was evaluated by measuring the residual H₂O₂ concentration after incubation with COF-FA, as reported in the literature [

29,

34]. Various concentration of COF-FA (20, 40, or 80 mg) was added to 10 mL of 150 μM H₂O₂ in amber vials. Control samples contained H₂O₂ without COF-FA. All samples were incubated at 37°C with mechanical stirring (100 rpm). At 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, 300 μL aliquots were centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 5 min), and supernatants were analyzed using a hydrogen peroxide assay kit. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Additional tests were conducted using 250 μM H₂O₂ under identical conditions.

2.8. In Vitro Release Study

The release profile of FER was evaluated utilizing a dialysis bag technique. A pre-hydrated cellulose membrane with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 3000 kDa was loaded with 5.0 mL of the sample (aqueous FER or FER@COF-FA), which was then immersed in a 40 mL PBS receptor solution maintained at 37 °C under constant agitation. At predetermined intervals, 1.0 mL aliquots were withdrawn, and the FER concentration was quantified via HPLC. Following each sampling event, an equal volume of fresh PBS was replenished to ensure a consistent receptor volume and osmolality

2.9. Cell Viability Assay

RAW264.7 and Caco2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 10,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h (37°C, 95% air, 5% CO₂). Cells were treated with COF, COF-FA, and FER@COF-FA at various concentrations. Subsequently, 100 μL of CCK-8 solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well. After 2 h incubation, absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (GENios Tecan). Six replicates per concentration and three independent experiments were performed. Untreated cells and culture medium served as control and blank, respectively.

2.10. In Vivo Study

2.10.1. Animal Grouping and Study Design

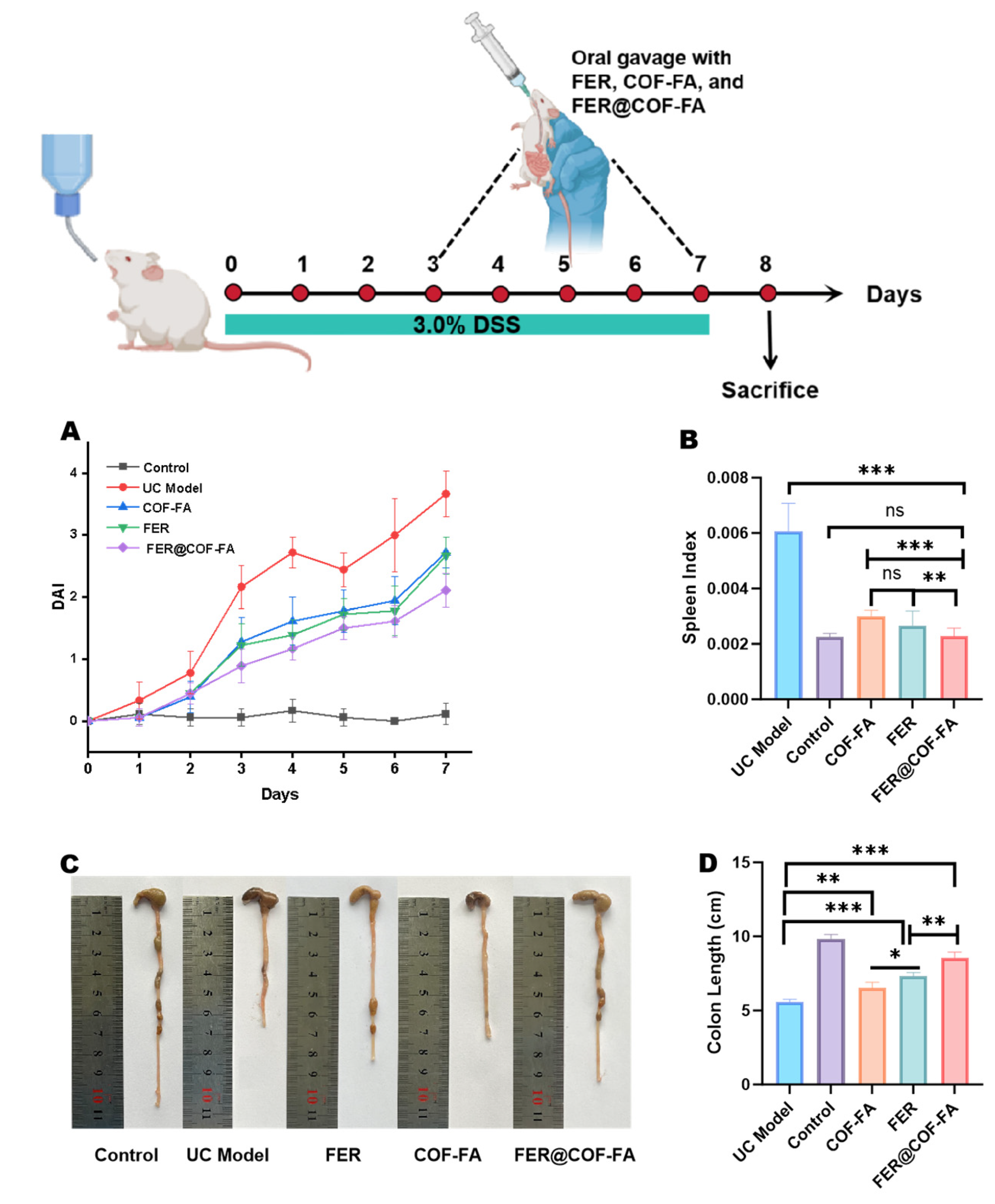

Thirty male Kunming (KM) mice (6-8 weeks, 33.0 ± 2.0 g, specific pathogen-free [SPF] grade) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Science Center of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine (License No.: SCXK(Gan)2023-0001). All procedures complied with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (JZLLSC-20240590). Thirty SPF-grade male KM mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6): Control group, UC model group, FER group (60 mg/kg body weight), COF-FA group (400 mg/kg, containing 60 mg/kg FER), and FER@COF-FA group (400 mg/kg).

The mice were housed at 22 ± 2°C and 50 ± 5% humidity under 12-h light/dark cycles. After a one-week acclimatization period (distilled water ad libitum, standard diet), UC was induced in all groups except the controls by administering 3.0% (w/v) dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in the drinking water for 7 days. Treatments were administered daily via oral gavage based on their grouping starting from day 3 to day 7. On the eighth day, mice were anesthetized. Blood was collected via retro-orbital puncture, after which the animals were euthanized. Subsequently, the colon length and spleen weight were measured. A segment of the distal colon (approximately 1 cm) was collected and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological analysis.

2.10.2. Disease Activity Index (DAI) Evaluation

During DSS treatment, body weight, stool characteristics and blood in the stool were recorded every day and scored from 0 to 4 points: weight loss (0: 0-1%; 1: 1-5%; 2: 5-10%; 3: 10-15%; 4: >15%, percentage refers to mass fraction); stool consistency (0: normal; 2: loose stool; 4: diarrhea); stool bleeding (0: normal; 2: blood; 4: total bleeding) [

35,

36]. DAI was calculated as the average score

2.10.3. Determination of Colon Length and Spleen Index

Body weight was recorded before euthanasia. The colon was excised from the cecocolonic junction to the proximal rectum and measured. Spleens were weighed to calculate the spleen index:

Spleen index (%) = [Spleen weight (g) / Final body weight (g)] × 100% (1)

2.10.4. Analysis of Colon Tissue Pathology Sections

The end of the colon was taken at 0.5 cm. After being fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours, the tissue was dehydrated using a gradient of ethanol, anhydrous ethanol, and xylene, embedded in paraffin, and then sliced into 5-μm-thick sections using a slicer. The slices were placed in an oven at 70 °C and cooled to room temperature. The paraffin slices were dewaxed in xylene I, xylene II, anhydrous ethanol I, anhydrous ethanol II, and 75% alcohol in sequence. The slices were washed with water and stained with hematoxylin. After differentiation in 0.65% ammonia water and eosin counterstaining, slides were dehydrated, mounted with neutral balsam, and imaged by microscopy.

2.10.5. Serum Inflammatory Cytokine Measurement

Serum was separated by centrifugation (4°C, 4000 rpm, 10 min). IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 levels were quantified using ELISA kits according to manufacturer protocols. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm immediately after reaction termination.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from a minimum of six independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism software (v10.1.2) by applying one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple groups or an unpaired Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons. Significance levels are denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns indicates not significant (p > 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

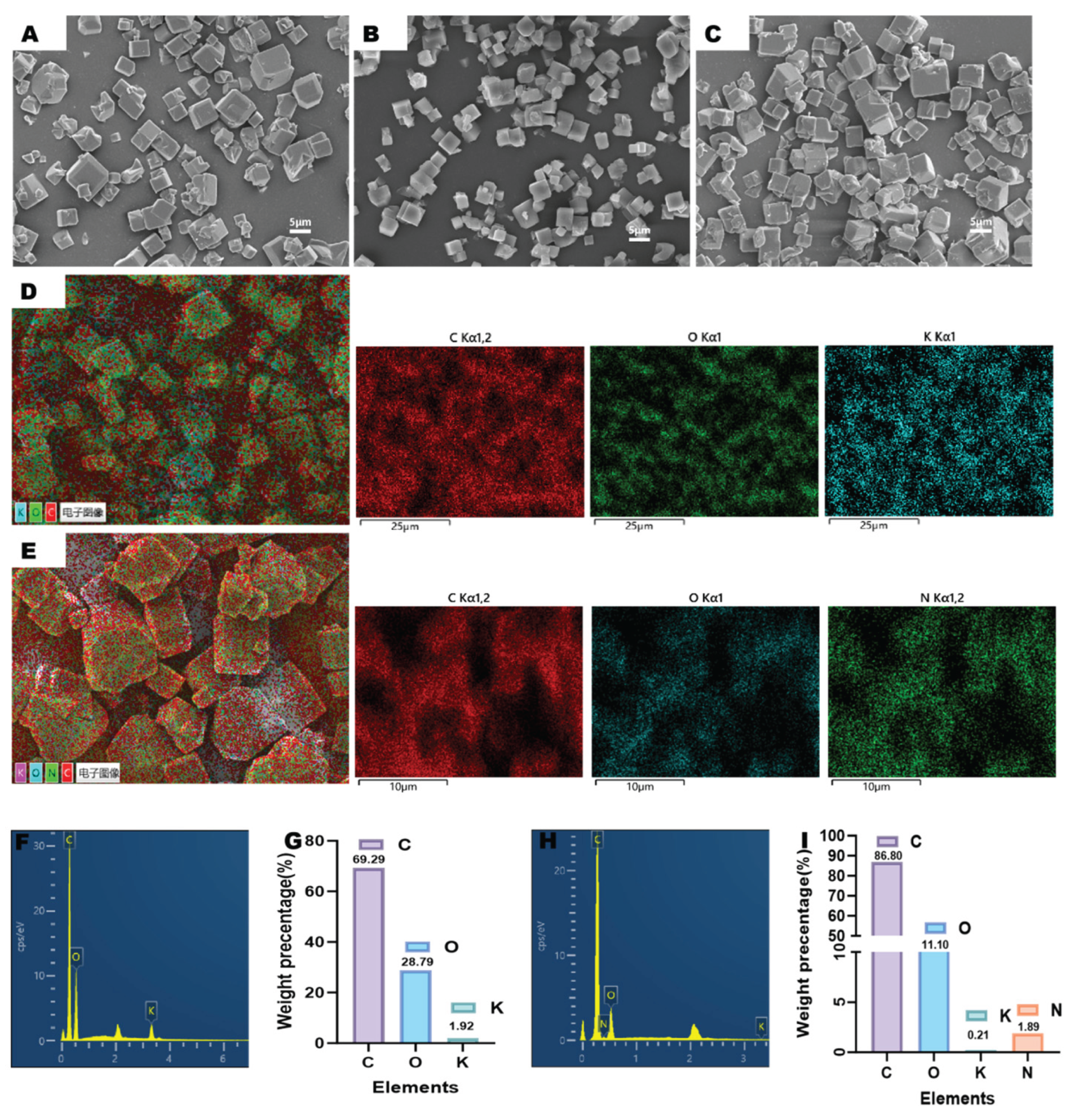

The SEM imaging results confirm that both pristine COF particles and FA-modified COF exhibit uniform cubic morphology as shown in

Figure 1A,B. Critically, this structural integrity is preserved following sequential FA crosslinking and FER loading (

Figure 1C), demonstrating that neither surface modification nor drug encapsulation compromises the framework integrity of the resulting FER@COF-FA delivery system. HPLC quantitative analysis result further substantiates successful functionalization; the FA surface grafting efficiency reached 9.98% ± 0.83%, confirming covalent modification of the COF carrier. Concurrently, FER loading achieved 14.97% ± 0.91%, validating effective drug encapsulation within the stabilized architecture (

Figure S1).

The elemental profiles of CD-MOF and its functionalized derivative FER@COF-FA, revealed by EDS (

Figure 1D-I), demonstrate profound compositional shifts that elucidate the structural modifications. CD-MOF’s ternary system, consisting of carbon (69.29%), oxygen (28.79%), and potassium (1.92%), reflects its γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD) foundation, where K⁺ ions coordinate hydroxyl groups to stabilize the metal-organic framework (

Figure 1F,G) [

37,

38]. Crucially, oxalyl chloride (ClCO-COCl) drives the transformation to COF by enabling two simultaneous processes: (1) covalent crosslinking between the numerous hydroxyl group in γ-CD-MOF to formperoxalate ester bonds, and (2) elemental recomposition by substituting K⁺ ions [

29]. Furthermore, following FA modification, the resultant COF-FA exhibits four elements: carbon (86.80%, +17.51%), nitrogen (1.89%, new), oxygen (11.10%, –17.69%), and trace potassium (0.21%, –1.71%) as illustrated in

Figure 1H,I.

The carbon surge arises directly from oxalyl chloride’s high-carbon backbone (–CO–CO–), which inserts two carbon atoms per crosslink during ester bond formation (R–OH + ClCO–COCl → R–O–CO–CO–Cl + HCl). Concomitantly, FA’s pterin ring contributes additional carbon. The drastic oxygen reduction stems from oxalyl chloride’s deoxygenating reactivity, with each crosslinking event consuming two hydroxyl groups (–OH) from γ-CD-MOF/FA, releasing HCl and eliminating oxygen atoms originally bound to hydrogen. This offsets oxygen introduced by FA, yielding a net decline. The residual potassium (0.21%) confirms near-complete K⁺ displacement during crosslinking, while nitrogen’s emergence fingerprints FA integration.

Quantitatively, the data align with reaction stoichiometry, where 1) the 25.3% relative carbon increase (ΔC = 17.51%) exceeds FA’s carbon contribution, underscoring oxalyl chloride’s role. 2) Oxygen’s 61.5% decline (ΔO = 17.69%) correlates with consumed –OH groups. These shifts validate COF-FA as a covalently networked, organic-dominant framework that is distinct from CD-MOF’s ion-coordinated architecture. The EDS evidence, synergized with oxalyl chloride’s chemistry, thus establishes an unambiguous lineage from precursor to product.

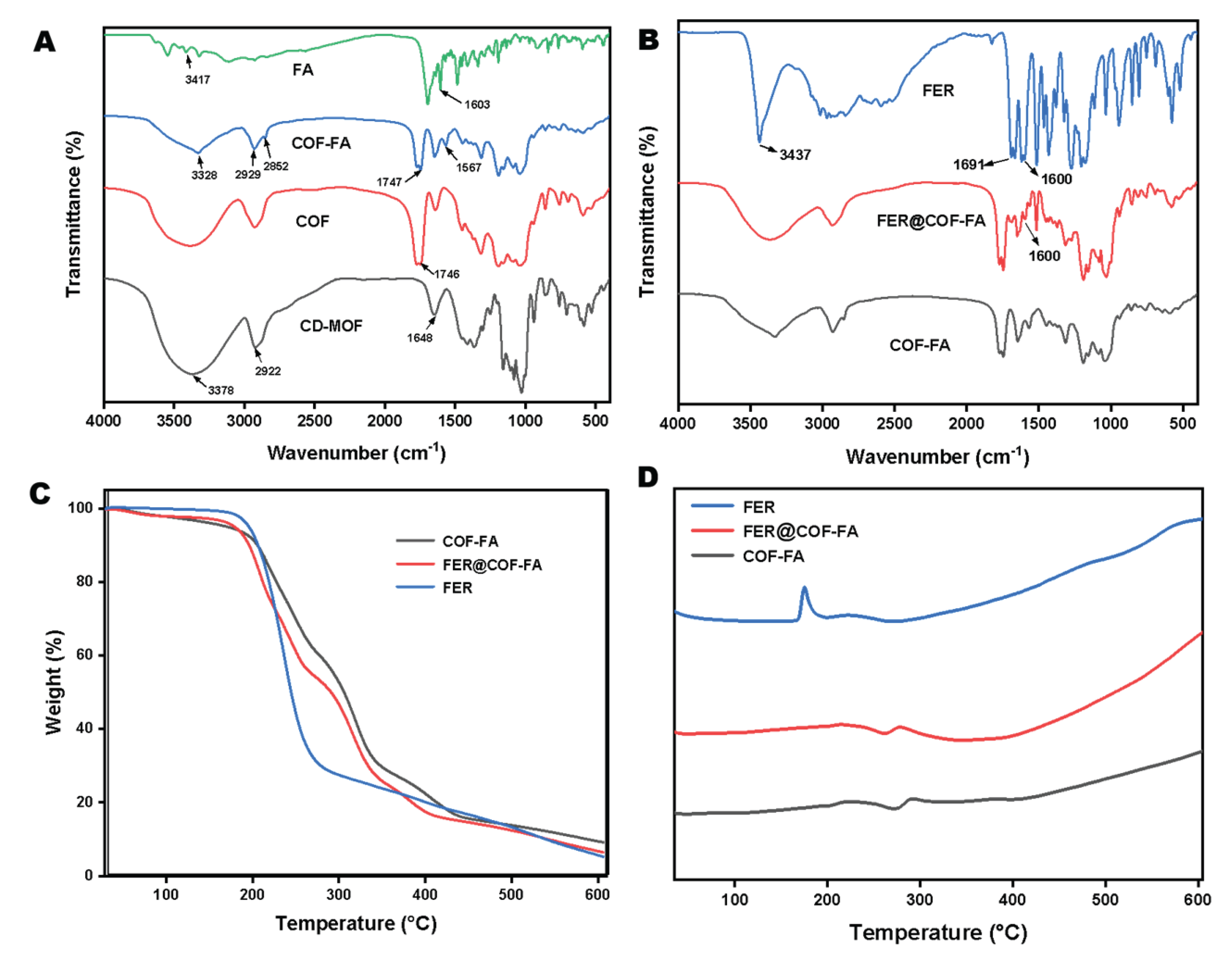

FT-IR analysis (

Figure 2A,B) reveals critical structural distinctions between CD-MOF and COF. CD-MOF displays a broad hydroxyl (-OH) stretching vibration at 3378 cm⁻¹, characteristic of O-H groups within γ-CD’s glucose rings, alongside a C-H stretching vibration at 2922 cm⁻¹ attributed to CH₂/CH groups, a feature conserved in both materials [

39]. However, COF exhibits significant attenuation of the -OH peak, directly evidencing successful esterification between CD-MOF’s hydroxyl groups and oxalyl chloride. Further confirming this transformation, CD-MOF’s 1648 cm⁻¹ peak (assigned to H-O-H bending of confined water) disappears in COF, while a new peak emerges at 1746 cm⁻¹. This signal corresponds to C=O stretching of oxalate esters, verifying covalent crosslink formation via oxalyl chloride-mediated reactions.

Folic acid modification introduces distinct spectral signatures; its FT-IR spectrum shows a broad 3417 cm⁻¹ peak from overlapping O-H (carboxyl/phenolic) and N-H (pterin ring) stretching vibrations, plus aromatic C=O stretching at 1603 cm⁻¹ from p-aminobenzoyl/pterin moieties [

40,

41]. Following FA functionalization to yield COF-FA, new peaks materialize at 3328 cm⁻¹ (N-H stretch) and 1567 cm⁻¹ (aromatic C=C), confirming FA’s successful incorporation (

Figure 2A). Critically, the preservation of COF’s oxalate carbonyl peak (1746 cm⁻¹) alongside these new signals indicates that FA grafting occurs without disrupting the pre-established crosslinked framework (

Figure 2B). Collectively, the spectral evolution diminished -OH vibrations, emergent oxalate carbonyls, and FA-specific N-H/aromatic bands, which further provides evidence for the sequential synthesis of (i) oxalyl chloride-driven crosslinking of CD-MOF into COF, and (ii) subsequent surface modification via FA to achieve COF-FA.

PXRD reveal the critical transition between the crystalline cubic CD-MOF into an amorphous cubic particle following introduction of the peroxalate ester bond as shown by

Figure S2. Meanwhile, TGA analysis reveals critical interactions between FER and the COF-FA carrier. As shown in Figures 2C and S3, pure FER undergoes rapid mass loss between 180–277°C, peaking at 237.98°C. Following encapsulation within COF-FA, however, the FER@COF-FA exhibits fundamentally altered thermal behaviour. Its decomposition profile aligns with the COF-FA carrier rather than free FER, with the maximum mass loss temperature shifting to 316.63°C. This value closely approximates COF-FA’s decomposition peak (319.71°C), indicating FER interacts strongly with the carrier matrix, as demonstrated in

Figure 2C, confirming the successful incorporation rather than surface adsorption [

42]. Furthermore, the DSC results (

Figure 2D) provide complementary evidence to the TGA results. The pure FER displays a characteristic endothermic melting peak at 174.83°C, this thermal signature disappears entirely in the FER@COF-FA thermogram across the 30–250°C range [

43]. The absence of FER’s melting transition confirms molecular-level dispersion and stabilization of the drug within the carrier framework. Collectively, these thermal transformations and the 78.65°C upward shift in decomposition temperature and suppression of FER’s melting endotherm demonstrate successful encapsulation through non-covalent interactions that disrupt FER’s crystalline lattice while enhancing its thermal stability.

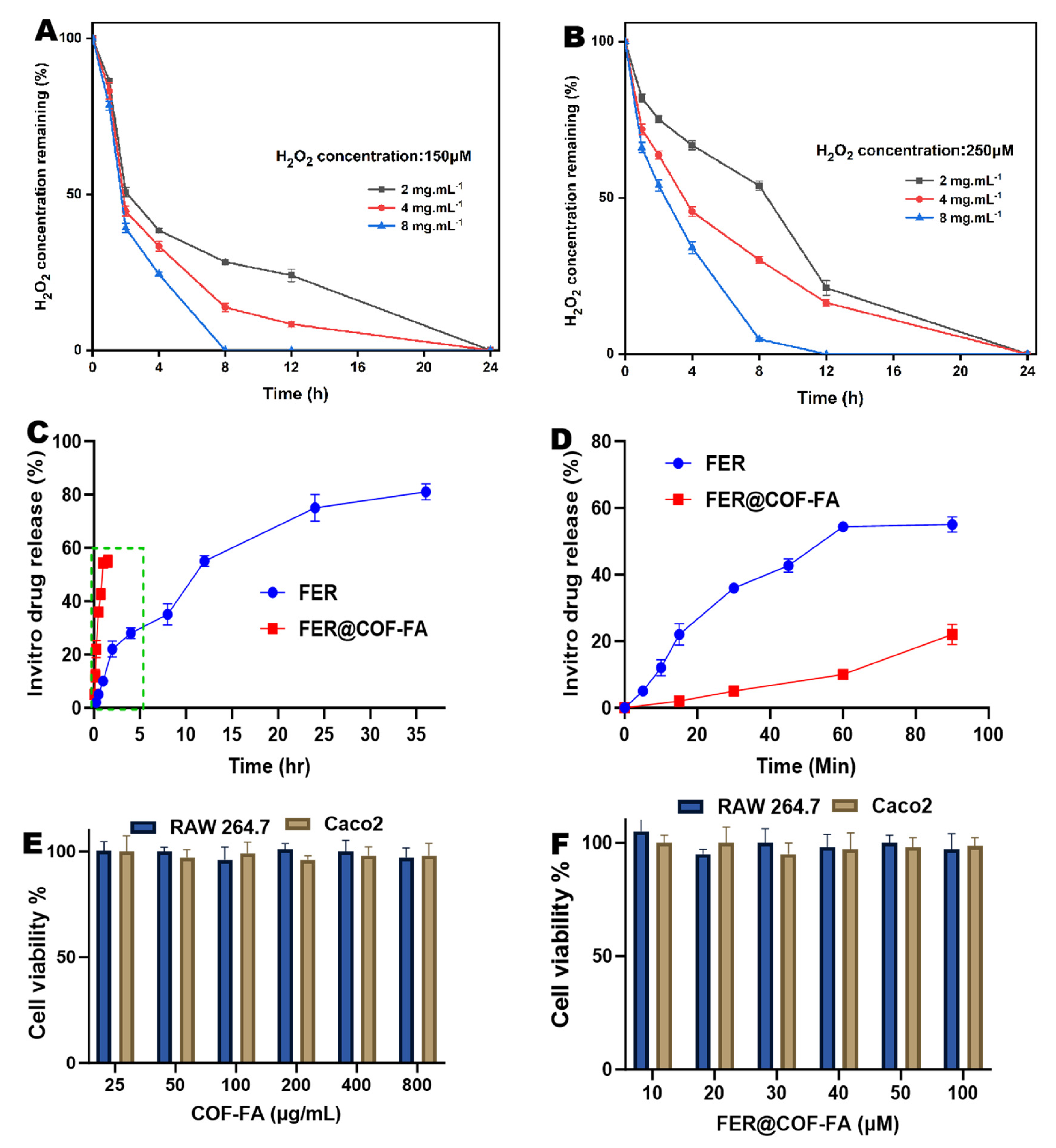

3.2. Evaluation of In Vitro H₂O₂ Scavenging Ability of COF-FA

The antioxidant capacity of COF particles was evaluated by measuring their ability to scavenge hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and suppress intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mechanistically, it has been demonstrated that polyoxalate bonds in COF undergo hydrolysis in aqueous environments, producing oxalic acid that reacts stoichiometrically with H₂O₂ to form CO₂ and water [

29,

44]. This reaction enables molar-equivalent H₂O₂ elimination per hydrolyzed unit. Experimental assessment at pH 7.4, H₂O₂ confirmed concentration- and time-dependent scavenging (

Figure 3A,B). At 150 μM H₂O₂, COF-FA (2–8 mg/mL) progressively reduced residual peroxide over 4 hours, with 8 mg/mL achieving 75.56% clearance (24.44% ± 0.69% residual) as shown in

Figure 3A. When H₂O₂ concentration increased to 250 μM, the clearance trend persisted, but efficiency declined, 8 mg/mL COF-FA yielded 65.96% clearance (34.04% ± 1.93% residual). This 9.6% reduction in scavenging efficacy correlates directly with elevated peroxide levels, indicating substrate-limited reaction kinetics (

Figure 3B). Critically, all tested concentrations demonstrated significant H₂O₂ removal, confirming COF-FA’s functionality as a peroxide-scavenging material across biologically relevant conditions.

3.3. In Vitro Release Study

The in vitro release profiles of FER and FER@COF-FA reveal distinct differences in their release behavior as demonstrated in

Figure 3C,D. Free FER exhibited a rapid release, with most of the drug diffusing into the medium within 80 min. This burst release is characteristic of unencapsulated drugs, reflecting the absence of a carrier system to control diffusion. Such a rapid release can lead to poor bioavailability and limited therapeutic efficiency, since the drug may be metabolized or cleared quickly from the body [

45]. In contrast, FER@COF-FA demonstrated a much slower and sustained release profile (

Figure 3D). The COF matrix effectively retained FER, preventing immediate diffusion and allowing a gradual release over an extended period (35 h). This controlled release behavior minimizes the burst effect observed in free FER and provides a more stable release pattern, which is advantageous for maintaining therapeutic concentrations over time.

3.4. Cytotoxicity of COF-FA and FER@COF-FA Carrier

The cytotoxicity of COF, COF-FA and FER@COF-FA was evaluated in RAW 264.7 macrophages and Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells to assess their biocompatibility. For COF and COF-FA, a wide concentration range of 25–800 μg/mL was tested (Figures S4 and 3E), while FER@COF-FA was examined at 10–100 μM based on the equivalent concentration of encapsulated FER (

Figure 3F). Across all tested concentrations, both formulations maintained high cell viability, consistently above 90%, indicating negligible cytotoxicity toward either cell line.

In RAW 264.7 cells, which represent activated macrophages commonly associated with inflammation, COF-FA exhibited no significant dose-dependent reduction in viability. Similarly, FER@COF-FA preserved high cell survival, confirming that the encapsulation of FER did not increase toxicity. In Caco-2 cells, a model of intestinal epithelium relevant to ulcerative colitis, both COF-FA and FER@COF-FA again demonstrated excellent safety profiles, further supporting their compatibility for gastrointestinal applications. These results highlight the intrinsic biocompatibility of COF-FA as a carrier, which is essential for safe biomedical use. Moreover, the absence of additional toxicity upon FER loading confirms that FER@COF-FA retains the favorable safety characteristics of the carrier.

3.5. In Vivo Study

3.5.1. Therapeutic Efficacy in DSS-Induced Colitis

A UC model was established by administering 3% DSS ad libitum to mice. By day three, animals exhibited classic colitis symptoms, including weight loss, diarrhea, and hematochezia, while control mice remained clinically stable (

Figure 4) [

46,

47]. Disease severity peaked at day seven, with the untreated UC model group showing maximal DAI scores reflecting progressive wasting and rectal bleeding. Therapeutic interventions demonstrated hierarchical efficacy, with FER significantly reducing DAI scores compared to the UC model, confirming antioxidant-mediated symptom mitigation as shown in

Figure 4A. The COF-FA carrier further attenuated disease severity beyond FER monotherapy, suggesting enhanced bioavailability through folic acid functionalization. Remarkably, FER@COF-FA particles achieved maximal clinical improvement, demonstrating synergistic alleviation of all symptoms.

Systemic and anatomical biomarkers provided quantitative validation of therapeutic outcomes. The spleen index, reflecting systemic inflammatory burden, increased significantly in UC model mice compared to the control group (P < 0.001,

Figure 4B). FER monotherapy reduced splenomegaly by 50.48%, indicating moderate immunomodulatory effects. COF-FA carrier alone achieved a 56.07% reduction (P < 0.001), surpassing free FER and highlighting the intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties of the functionalized nanocarrier. Notably, FER@COF-FA particles demonstrated maximal efficacy with a 62.35% decrease (P < 0.001), attributable to a synergistic effect combining anti-inflammatory/antioxidant delivery with likely folate receptor-mediated cellular uptake and enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in the inflamed tissue. Several studies in cells and in vivo have demonstrated the efficacy of drug delivery systems targeting the folate receptor. This enhanced efficacy aligns with previous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of folate receptor-targeted drug delivery systems. Research has shown that fluorescently-labeled nanoparticles exhibit enhanced uptake in folate receptor-expressing colon epithelial cells, activated macrophages, and inflamed colon tissue [

48]. Additional studies have confirmed that folate-targeted dendrimers specifically bind to folate receptor-expressing macrophage cell lines in vitro and selectively accumulate in areas of inflammation in vivo [

49]. Furthermore, modification with folic acid molecules has been shown to improve inflammatory cell targeting capability and ensure successful drug delivery to sites of inflammation [

33,

50,

51,

52]. Collectively, these findings provide a compelling rationale for the enhanced efficacy observed with the FER@COF-FA formulation

.

Colon shortening, which is regarded as a hallmark of DSS-induced mucosal damage [

53], reached 43.24% in UC models (P < 0.001,

Figure 4C,D). While FER partially restored length (16.71%, P < 0.01), and COF-FA showed enhanced tissue protection (31.24%, P < 0.001). Interestingly, FER@COF-FA achieved near-complete restoration (50.10% improvement, P < 0.001), directly correlating with histopathological observations of preserved crypt architecture. This anatomical recovery signifies potent mitigation of fibrotic remodeling. Collectively, the hierarchical therapeutic efficacy (FER@COF-FA > COF-FA > FER) confirms two critical advantages: 1) Folic acid functionalization enhances colonic retention through receptor-mediated binding, 2) COF-mediated antioxidant capability, and 3) Nanoencapsulation protects FER from degradation, enabling sustained ROS scavenging in inflamed tissues.

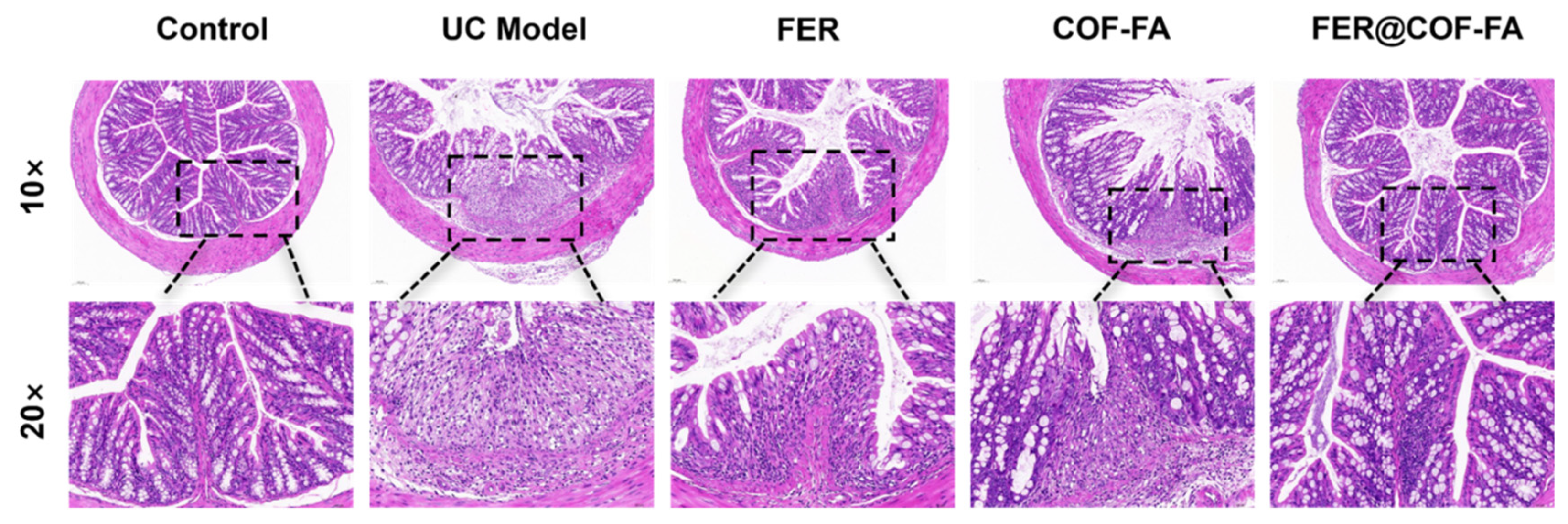

3.5.2. Pathological Changes in the Colonic Tissue of Mice

Histopathological analysis of H&E-stained colonic tissues revealed graded colitis severity across experimental groups (

Figure 5). Control mice exhibited normal tissue architecture featuring regularly arranged mucosal epithelia, abundant goblet cells, absence of epithelial necrosis, and no interstitial congestion or inflammatory infiltration. Conversely, the UC model group showed severe structural disruption, including complete mucosal layer erosion, extensive ulceration with nuclear condensation and lysis, and transmural inflammatory cell infiltration [

54]. Mice treated with free FER displayed mild architectural abnormalities characterized by intact epithelial organization but significantly diminished goblet cells and notable inflammation. The COF-FA group demonstrated moderate pathology with focal mucosal ulcers exhibiting nuclear degeneration, though goblet cell numbers remained normal amid substantial inflammatory infiltration. Critically, the FER@COF-FA group presented only minor deviations: preserved epithelial integrity without necrosis, abundant goblet cells, absence of interstitial congestion, and limited inflammatory cell infiltration.

These findings indicate that FER@COF-FA significantly outperform FER in alleviating colonic damage, while COF-FA alone also confers therapeutic benefits. The superior histological preservation, particularly maintenance of epithelial integrity, goblet cell populations, and attenuated inflammation, confirms FER@COF-FA’s efficacy in mitigating DSS-induced colitis at the tissue level. This demonstrates substantial therapeutic potential.

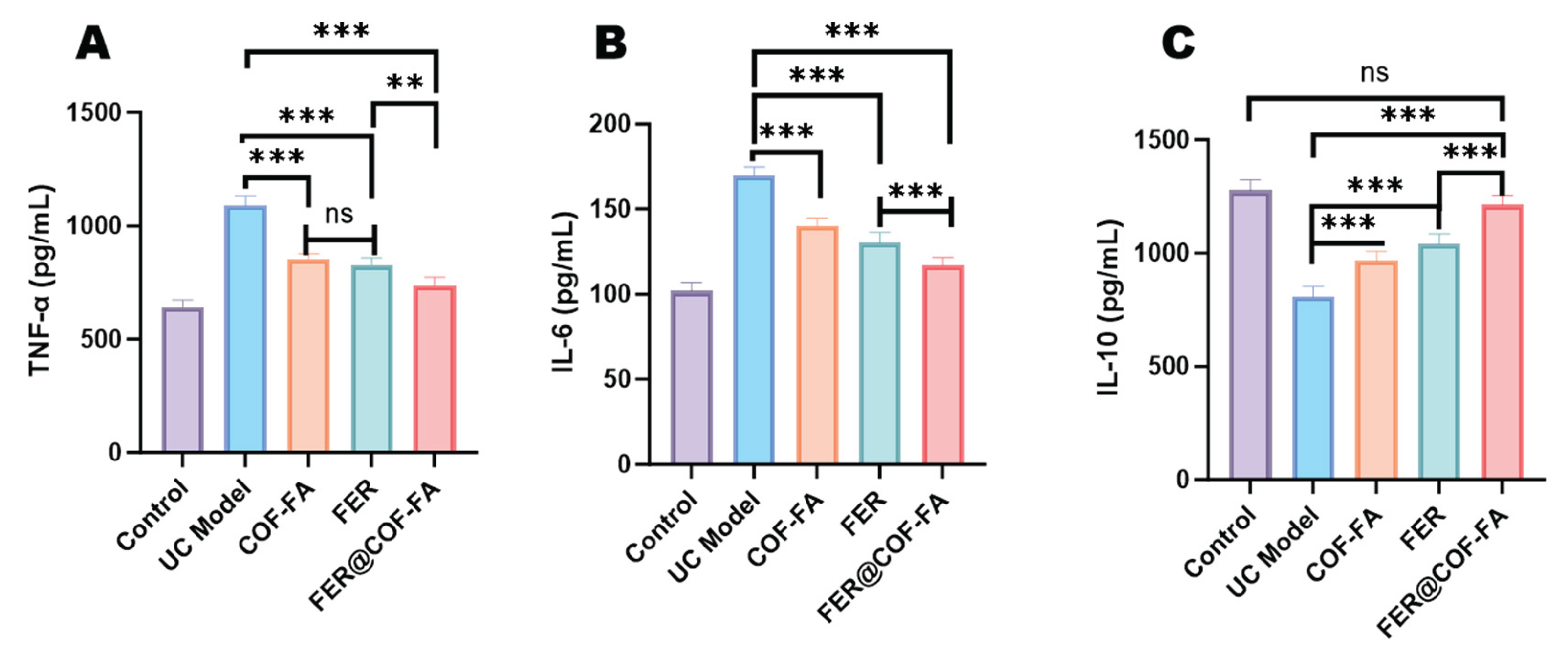

3.5.3. Effect of Inflammatory Factors in Mice Serum

Quantitative analysis of serum cytokines revealed profound inflammatory dysregulation in experimental groups (

Figure 6). Relative to controls, UC model mice exhibited significantly elevated TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations (P < 0.001) alongside substantially reduced IL-10 (P < 0.001). Therapeutic interventions demonstrated progressive efficacy where the FER attenuated TNF-α by 23.92% and IL-6 by 23.25% while elevating IL-10 by 28.79% (all P < 0.001). COF-FA carrier monotherapy similarly modulated inflammatory mediators, reducing TNF-α (21.56%) and IL-6 (17.25%) while increasing IL-10 (19.52%, P < 0.001). Significantly, FER@COF-FA achieved maximal cytokine normalization, suppressing TNF-α (32.36%) and IL-6 (31.14%) while enhancing IL-10 (50.06%, all P < 0.001). This superior IL-10 induction significantly exceeded both comparator therapies, establishing FER@COF-FA as the most effective intervention for inflammatory mitigation. The amplified anti-inflammatory response confirms that nanoencapsulation potentiates FER’s therapeutic efficacy against colitis-associated tissue damage.

3.6. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, the therapeutic efficacy was evaluated in a single animal model of DSS-induced colitis. Future studies employing additional models, such as TNBS-induced colitis, would strengthen the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, while the superior performance of FER@COF-FA is highly suggestive of active targeting through folate receptor mediation, direct proof, such as cellular uptake studies in folate receptor-positive versus negative cells or in vivo biodistribution imaging with a fluorescent tracer, was not obtained. Confirming this specific mechanism remains a key objective for future research. Furthermore, investigating the long-term toxicity and biodistribution of the COF-FA carrier would be essential for clinical translation.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed FER@COF-FA, a multi-functional nanotherapeutic platform for ulcerative colitis. The system synergistically combines a sustained-release covalent organic framework, intrinsic ROS-scavenging capability, and folate-mediated targeting potential. Comprehensive characterization validated the nanocarrier’s structure, antioxidant properties, and controlled release profile. In vivo evaluation demonstrated superior therapeutic efficacy compared to free ferulic acid, with significant improvements in disease activity, colon pathology, and inflammatory cytokine balance. The enhanced outcomes are consistent with a proposed mechanism involving site-specific delivery enhanced by ROS-responsive drug release and potential macrophage targeting. While further mechanistic studies () are warranted to fully elucidate the cellular targeting pathway, the current findings establish FER@COF-FA as a promising targeted therapeutic strategy. This work provides a strong foundation for developing advanced nano-formulations that address the complex pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel diseases through multi-mechanistic approaches.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

J.X.; Data collection and curation, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, and writing—original draft. Z.Q.; Data collection and curation, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, and writing—original draft. S.H.; Data collection, investigation, and formal analysis. M.G.B.; Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, review and editing manuscript. L.C.; Supervision, funding acquisition, resource, project administration, validation, review, and editing manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Innovation Method Special Project [grant number 2020IM010500] and the University-level Innovation Team for the Development and Evaluation of High-quality Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Products [grant number CXTD-22004].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine (License No.: SCXK(Gan)2023-0001) and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (JZLLSC-20240590).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Further requests may be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the Key Laboratory of Modern Preparation of TCM, Ministry of Education, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, for its vital experimental platform support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to declare.

References

- Tatiya-aphiradee, N.; Chatuphonprasert, W.; Jarukamjorn, K. Immune Response and Inflammatory Pathway of Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology 2018, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, A.; Herrero-Fernandez, B.; Gomez-Bris, R.; Sánchez-Martinez, H.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Innate Immune System. IJMS 2023, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Goggolidou, P. Ulcerative Colitis: Understanding Its Cellular Pathology Could Provide Insights into Novel Therapies. J Inflamm 2020, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Jain, P. ; Ajazuddin Recent Advances in the Therapeutics and Modes of Action of a Range of Agents Used to Treat Ulcerative Colitis and Related Inflammatory Conditions. Inflammopharmacol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuyyuru, S.K.; Jairath, V. Unresolved Challenges in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Indian J Gastroenterol 2024, 43, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, K.; Becher, N. Ulcerative Colitis Diagnosis and Management: Past, Present, and Future Directions. In Inflammatory Bowel Disease; Rajapakse, R., Ed.; Clinical Gastroenterology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-81779-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chaemsupaphan, T.; Arzivian, A.; Leong, R.W. Comprehensive Care of Ulcerative Colitis: New Treatment Strategies. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, S.; Qian, D.; Duan, J. Excessive Apoptosis in Ulcerative Colitis: Crosstalk Between Apoptosis, ROS, ER Stress, and Intestinal Homeostasis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2022, 28, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravda, J. Radical Induction Theory of Ulcerative Colitis. WJG 2005, 11, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Fan, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, F.; et al. Selective Oxidative Protection Leads to Tissue Topological Changes Orchestrated by Macrophage during Ulcerative Colitis. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Meng, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Z.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, K.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Nanocarrier Ameliorates Murine Colitis by Intervening Colonic Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. Molecular Therapy 2023, 31, 1383–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, S.; Chelvam, V.; Low, P.S. Comparison of Nanoparticle Penetration into Solid Tumors and Sites of Inflammation: Studies Using Targeted and Nontargeted Liposomes. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2015, 10, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Xia, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, P.; Jin, Y. Role of Macrophage in Nanomedicine-Based Disease Treatment. Drug Delivery 2021, 28, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Sung, J.; Garg, P.; Zhang, M.; Merlin, D. Oral Targeted Delivery by Nanoparticles Enhances Efficacy of an Hsp90 Inhibitor by Reducing Systemic Exposure in Murine Models of Colitis and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2020, 14, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, R. Plant-Derived Exosomes as a Drug-Delivery Approach for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Xi, R.; Long, D. Advances in Oral Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Using Protein-Based Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Delivery 2025, 32, 2544689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanakumar, G.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.J. Reactive-Oxygen-Species-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems: Promises and Challenges. Advanced Science 2017, 4, 1600124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, N.; Gambhir, K.; Kumar, S.; Gangenahalli, G.; Verma, Y.K. Interplay of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Tissue Engineering: A Review on Clinical Aspects of ROS-Responsive Biomaterials. J Mater Sci 2021, 56, 16790–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; He, Z. ROS-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems for Biomedical Applications. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 13, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhi; Rashid, M. ; Kaur, V.; Hallan, S.S.; Sharma, S.; Mishra, N. Microparticles as Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: A Brief Review. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2016, 24, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvozdeva, Y.; Staynova, R. pH-Dependent Drug Delivery Systems for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lan, H.; Jin, K.; Chen, Y. Responsive Nanosystems for Targeted Therapy of Ulcerative Colitis: Current Practices and Future Perspectives. Drug Delivery 2023, 30, 2219427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Si, X.; Zhang, M.; Merlin, D. Oral Administration of pH-Sensitive Curcumin-Loaded Microparticles for Ulcerative Colitis Therapy. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2015, 135, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhtiar, M.; Ghasemi-Dehnoo, M.; Azadegan-Dehkordi, F.; Bagheri, N. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of Ferulic Acid and Quinic Acid on Acetic Acid-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. J Biochem & Molecular Tox 2025, 39, e70169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guan, Y.; Yang, L.; Fang, H.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Yan, G.; Kong, L.; Wang, X. Ferulic Acid as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent: Insights into Molecular Mechanisms, Pharmacokinetics and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Luo, Y. Chitosan-Based Oral Colon-Specific Delivery Systems for Polyphenols: Recent Advances and Emerging Trends. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 7328–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.D.; Singh, D. A Critical Appraisal on Ferulic Acid: Biological Profile, Biopharmaceutical Challenges and Nano Formulations. Health Sciences Review 2022, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, J.R.; Rizwanullah, Md. Ferulic Acid: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, L.; Sun, H.; Wu, D.; Wang, C.; Ren, X.; Shao, Q.; York, P.; Tong, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. Antioxidant Biodegradable Covalent Cyclodextrin Frameworks as Particulate Carriers for Inhalation Therapy against Acute Lung Injury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 38421–38435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, D.; Wang, M.; Bai, J.; Wang, N.; Bian, W.; Zhou, B. Polyrotaxanated Covalent Organic Frameworks Based on β-Cyclodextrin towards High-Efficiency Synergistic Inactivation of Bacterial Pathogens. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 486, 150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Framework Design Principles and Functionalization for Biomedical Application. Carbohydrate Polymers 2025, 364, 123684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, M.G.; Huang, S.; Qiao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L. Luteolin Stabilized in Nanosheet and Cubic γ-Cyclodextrin-Based Metal Organic Framework for Enhanced Bioavailability and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2025, 10, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Chen, T.; Chi, X.; Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Zhu, B.; Hu, J. Targeted Quercetin Delivery Nanoplatform via Folic Acid-Functionalized Metal-Organic Framework for Alleviating Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcer. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498, 155700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhu, X.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.-F.; Wang, D.; Wen, W.; Liang, J.; et al. Ambient Synthesis of Porphyrin-Based Fe-Covalent Organic Frameworks for Efficient Infected Skin Wound Healing. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 3671–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, M.; Hirai, F.; Takatsu, N.; Hisabe, T.; Takada, Y.; Beppu, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Naganuma, M.; Ohtsuka, K.; Watanabe, K.; et al. A Review on the Current Status and Definitions of Activity Indices in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: How to Use Indices for Precise Evaluation. J Gastroenterol 2022, 57, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, B.; Jairath, V.; D’Amico, F.; Al Awadhi, S.; Dignass, A.; Hart, A.L.; Kobayashi, T.; Kotze, P.G.; Magro, F.; Siegmund, B.; et al. International Consensus on Definition of Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity in Adult Patients. Medicina 2023, 59, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, L.; Zhou, P.; Ding, H.; Ge, X.; Guo, T.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J. Facile Synthesis and Size Control of 2D Cyclodextrin-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks Nanosheet for Topical Drug Delivery. Part & Part Syst Charact 2020, 37, 2000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, L.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Z.; Garba, B.M.; Gao, G.; He, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. CD-MOFs Crystal Transformation from Dense to Highly Porous Form for Efficient Drug Loading. Crystal Growth & Design 2019, 19, 3888–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Xu, H.; Nie, Q.; Jia, B.; Bao, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Triggered Cleavage of Thioketal-Containing Supramolecular Nanoparticles for Inflammation-Targeted Oral Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. Adv Funct Materials 2025, 35, 2411979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamipour, Sh.; Sadjadi, M.S.; Farhadyar, N. Fabrication and Spectroscopic Studies of Folic Acid-Conjugated Fe3O4@Au Core–Shell for Targeted Drug Delivery Application. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015, 148, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y. Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro Release of Folic Acid-Conjugated Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Methotrexate for Targeted Delivery. Polym. Bull. 2012, 68, 1707–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummert, S.V.; Saini, H.; Hussain, M.Z.; Yadava, K.; Jayaramulu, K.; Casini, A.; Fischer, R.A. Cyclodextrin Metal–Organic Frameworks and Derivatives: Recent Developments and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5175–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, G.S.N.; Pereira, M.A.V.; Ostrosky, E.A.; Barbosa, E.G.; De Moura, M.D.F.V.; Ferrari, M.; Aragão, C.F.S.; Gomes, A.P.B. Compatibility Study between Ferulic Acid and Excipients Used in Cosmetic Formulations by TG/DTG, DSC and FTIR. J Therm Anal Calorim 2017, 127, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Khaja, S.; Velasquez-Castano, J.C.; Dasari, M.; Sun, C.; Petros, J.; Taylor, W.R.; Murthy, N. In Vivo Imaging of Hydrogen Peroxide with Chemiluminescent Nanoparticles. Nature Mater 2007, 6, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Teng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J. The Intestinal Delivery Systems of Ferulic Acid: Absorption, Metabolism, Influencing Factors, and Potential Applications. Food Frontiers 2024, 5, 1126–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.R.; Rodriguez, J.R. Clinical Presentation of Crohn’s, Ulcerative Colitis, and Indeterminate Colitis: Symptoms, Extraintestinal Manifestations, and Disease Phenotypes. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery 2017, 26, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayasu, I.; Hatakeyama, S.; Yamada, M.; Ohkusa, T.; Inagaki, Y.; Nakaya, R. A Novel Method in the Induction of Reliable Experimental Acute and Chronic Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Gastroenterology 1990, 98, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Sung, J.; Garg, P.; Zhang, M.; Merlin, D. Oral Targeted Delivery by Nanoparticles Enhances Efficacy of an Hsp90 Inhibitor by Reducing Systemic Exposure in Murine Models of Colitis and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2020, 14, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, S.; Putt, K.S.; Low, P.S. Folate-Targeted Dendrimers Selectively Accumulate at Sites of Inflammation in Mouse Models of Ulcerative Colitis and Atherosclerosis. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3082–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, S.; Chelvam, V.; Ayala-López, W.; Putt, K.S.; Low, P.S. Selective Liposome Targeting of Folate Receptor Positive Immune Cells in Inflammatory Diseases. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2018, 14, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Guo, S.; Liu, C. Effects of Folate-Chicory Acid Liposome on Macrophage Polarization and TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Ulcerative Colitis Mouse. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelderhouse, L.E.; Mahalingam, S.; Low, P.S. Predicting Response to Therapy for Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases Using a Folate Receptor-Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescent Imaging Agent. Mol Imaging Biol 2016, 18, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Shajib, Md.S.; Manocha, M.M.; Khan, W.I. Investigating Intestinal Inflammation in DSS-Induced Model of IBD. JoVE 2012, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Aitken, J.D.; Malleshappa, M.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis in Mice. CP in Immunology 2014, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).