Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem of Ranking Analysis

1.2. Limitations of Current Approaches

1.3. The Copula Perspective

1.4. Research Contribution and Novelty

- Regime detection. Starting from long-format data, CDEF pivots to wide form and auto-detects forced vs. non-forced rankings (ranking regime). For forced permutations with dependence, it scores Mallows structure; for forced independence, it compares to the uniform-permutation baseline; for non-forced rankings, it distinguishes independent (multinomial) from dependent regimes via screening.

- Dispersion mechanism. A test distinguishes independent rank allocation (multinomial) from without-replacement structure (hypergeometric), aligning inference with the data-generating process [40].

- Screening and reporting. Global concordance (W), mutual information across representative pairs, and likelihood summaries provide complementary views; decision rules then diagnose genuine vs. phantom agreement—phantom when high apparent concordance is largely attributable to tail dependence and shared dispersion patterns rather than stable consensus.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Ranking Analysis Fundamentals

2.2. Traditional Ranking Evaluation Methods

2.2.1. Concordance Measures

2.2.2. Dispersion Analysis

2.2.3. Extremeness Detection

2.3. Copula Theory in Dependence Modeling

2.3.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.3.2. Copula Families for Ranking Applications

2.3.3. Recent Advances in Copula Applications

2.4. Comparison with Recent Multivariate Ranking and Copula-Based Methods

2.5. Gaps in Current Literature and CDEF’s Unique Contribution

3. The Concordance–Dispersion–Extremeness Framework (CDEF)

3.1. Conceptual Foundation

3.2. Operational Formulation

3.2.1. Data Layout and Regime Detection

3.2.2. Concordance

3.2.3. Concurrence and (In)dependence Diagnostics

3.2.4. Extremeness via Copulas (Upper-Tail Co-Movement)

3.2.5. Dispersion Baselines and Model Selection

- Forced rankings and dependence detected: fit a Mallows modelwhere is Kendall distance and is a Borda-based consensus. We report an approximate Mallows log-likelihood and average distance to consensus [30].

- Non-forced rankings + dependence: dispersion is left nonparametric; we characterize dependence structure via the copula layer and report diagnostics (pairwise , average copula log-likelihood). For concentrated draws, we discuss links to multivariate hypergeometric sampling [40].

3.2.6. Copula Selection and Tail Dependence

3.2.7. Reporting: Normalized Contributions (Not Conditional Probabilities)

3.3. Estimation, Algorithms, and Numerical Safeguards

3.4. Model Validation and Extensions

4. Materials and Methods: Empirical Application

4.1. Data, Structure, and Preprocessing

4.1.1. Data Scope and Layout

4.1.2. Exemplar Design

- Phantom (Extreme Bias): All raters share an identical alternating extreme pattern (top/bottom alternation) with only 2 random swaps per rater to avoid perfect identity. This induces very high concordance and extreme upper-tail co-movement.

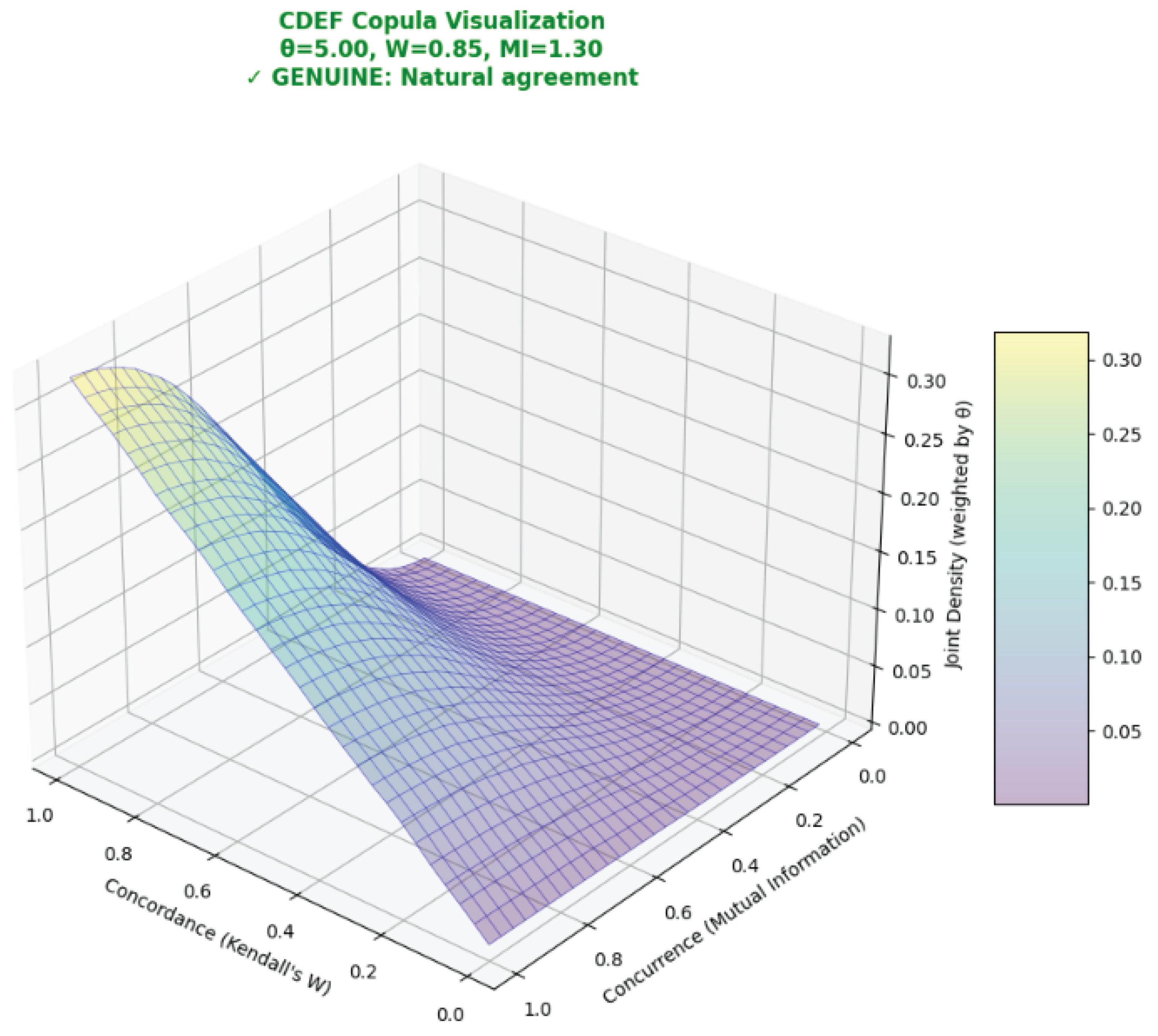

- Genuine (Natural Agreement): All raters start from the identity permutation and receive moderate noise via 12 random pair swaps, generating high but not extreme agreement without engineered tail behavior.

- Random (No Agreement): Each rater receives an independent random permutation, targeting near-independence.

- Clustered (Outlier): Three raters (CBS, CFN, NYT) form a tight cluster with 8 swaps each, while one rater (Congrove) is made deliberately divergent with 40 swaps.

4.1.3. Forced vs. Non-Forced Detection

4.2. Reproducibility

4.2.1. Data Schema and Ingestion

4.2.2. End-to-End Analysis Pipeline

- Load and reshape. Excel→DataFrame; pivot to wide (ratees × raters).

- Ranking-type detection. Forced (strict permutations) vs non-forced (ties allowed).

- Core concordance. Compute Kendall’s W from row-sum dispersion (closed form).

- Pairwise association. Compute pairwise Kendall’s and the full matrix.

- Global tail parameter. Map and scale by for a concordance-aware extremeness index.

- Model selection summary. Report the selected distributional family and its (approximate) log-likelihood, alongside the copula average log-likelihood baseline.

- Relative-importance decomposition. Report normalized weights over {Concordance W, Concurrence (MI), Extremeness }; these are interpretable as contribution weights, not probabilities.

4.2.3. Model Components and Estimation

4.2.4. Simulation Scenarios (Exemplar Study)

4.2.5. Software, Determinism, and Environment

- Programmatic: RankDependencyAnalyzer.analyze_from_excel("data.xlsx")

- Command-line: cdef_analyzer –input rankings.xlsx –output report.json

- Interactive: Jupyter notebooks for parameter exploration and visualization customization

4.2.6. Diagnostics and Validation

4.2.7. From Paper to Code

4.3. CDEF Components and Estimation

4.3.1. Concordance (Global Agreement)

4.3.2. Concurrence (Information-Sharing)

4.3.3. Extremeness (Upper-Tail Co-Movement)

4.4. Model Selection for the Ranking Regime

4.4.1. Forced Rankings

4.4.2. Non-Forced Rankings

4.5. Composite Reporting: Indices, Not Conditional Probabilities

4.6. Exemplar Outputs and Diagnostics

4.6.1. Numerical Safeguards and Edge Cases

5. Results

5.1. NCAA Analysis Results

5.1.1. CDEF Analysis Results

- Gumbel parameter from Kendall’s : (unscaled).

- Concordance-weighted index: .

- Average copula log-likelihood (per observation, across pairs): versus the independence baseline of .

- Model selection (forced rankings; dependence detected): Mallows (log-likelihood , reported as an approximate fit score).

5.1.2. Comparative Interpretation: Revealing Phantom Concordance

5.1.3. Quantifying the Cost of Ignoring Dependencies

5.2. Simulation Study

5.2.1. Analysis Pipeline

- Ranking type detection: forced vs. non-forced.

- Pairwise Gumbel copula fitting on pseudo-observations (empirical CDF ranks).

- Concordance (W), Kendall’s matrix, mutual information (MI), and average copula log-likelihood (per observation) vs. an independence baseline.

- Model selection: Mallows model for forced rankings under dependence (reported log-likelihood as an approximate fit score).

- Normalized indices (“relative importance”) for Concordance (W), Concurrence (MI), and Extremeness (); these are indices, not probabilities.

5.2.2. Results by Scenario

Phantom (Extreme Bias)

Genuine (Natural Agreement)

Random (No Agreement)

Clustered (Outlier)

| Scenario | W | MI | Avg LL | Indices (Conc/Concur/Extreme) | range | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom (Extreme Bias) | 0.964 | 30.733 | 15.648 | 2.358 | 2.047156 | 0.028 / 0.069 / 0.902 | 0.100 | 9.850–35.308 | Mallows (forced, dep.) |

| Genuine (Natural Agreement) | 0.748 | 4.232 | 2.421 | 1.611 | 0.411599 | 0.113 / 0.244 / 0.642 | 0.750 | 2.171–2.830 | Mallows (forced, dep.) |

| Clustered (Outlier) | 0.718 | 3.805 | 2.215 | 1.811 | 0.452280 | 0.113 / 0.286 / 0.601 | 0.750 | 1.542–3.877 | Mallows (forced, dep.) |

| Random (No Agreement)† | ≈ 1/3 / 1/3 / 1/3 | n/a | Baseline (indep.) |

5.2.3. Takeaways

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Methodological Advances

6.3. Practical Applications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Contributions

7.2. Implications for Practice

7.3. Future Research Directions

7.4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Generative AI

References

- Arrow, K.J. Social Choice and Individual Values, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1963; ISBN 978-0-300-01364-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Collective Choice and Social Welfare; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-0-8162-2158-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann, L. Scientific peer review. Annu. Rev. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 197–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic Judgment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engist, O.; Merkus, E.; Schafmeister, F. The effect of seeding on tournament outcomes. J. Sports Econ. 2021, 22, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csató, L. Tournament design: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 318, 800–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawazoe, Y.; Ohe, K. A clinical decision support system. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.C.; O’Kane, P.; Mazumdar, B.; McCracken, M. Performance management: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullen, S.E.; Bergey, P.K.; Aiman-Smith, L. Forced distribution rating systems and the improvement of workforce potential: A baseline simulation. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Saberi, M.; Chang, E. Analysing academic paper ranking algorithms using test data and benchmarks: an investigation. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 4045–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.; Friedman, L.; Sinuany-Stern, Z. Review of ranking methods in the data envelopment analysis context. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 140, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconis, P.; Graham, R.L. Spearman’s footrule as a measure of disarray. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1977, 39, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory; Wiley–Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y.; Tamhane, A.C. Multiple Comparison Procedures; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-471-82222-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, P.H.; Young, S.S. Resampling-Based Multiple Testing: Examples and Methods for p-Value Adjustment; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-471-55761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sklar, A. Fonctions de répartition à n dimensions et leurs marges. Publ. Inst. Stat. Univ. Paris 1959, 8, 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Dependence Modeling with Copulas; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4665-8322-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-28678-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, U.; Luciano, E.; Vecchiato, W. Copula Methods in Finance; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-470-86344-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.J. A review of copula models for economic time series. J. Multivar. Anal. 2012, 110, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, G.; De Michele, C.; Kottegoda, N.T.; Rosso, R. Extremes in Nature: An Approach Using Copulas; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4020-4415-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Bárdossy, A.; Habib, E. Conditional simulation of remotely sensed rainfall data using a non-Gaussian v-transformed copula. Adv. Water Resour. 2010, 33, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrechts, P.; McNeil, A.; Straumann, D. Correlation and dependence in risk management: Properties and pitfalls. In Risk Management: Value at Risk and Beyond; Dempster, M.A.H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 176–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, A.J.; Frey, R.; Embrechts, P. Quantitative Risk Management: Concepts, Techniques and Tools, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-691-16627-8. [Google Scholar]

- Emura, T.; Chen, Y.H. Gene selection for survival data under dependent censoring: A copula-based approach. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 25, 2840–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emura, T.; Sofeu, C.L.; Rondeau, V. Conditional copula models for correlated survival endpoints: Individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2021, 30, 2634–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marden, J.I. Analyzing and Modeling Rank Data; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 978-0-412-99521-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mallows, C.L. Non-null ranking models. I. Biometrika 1957, 44, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchlow, D.E. Metric Methods for Analyzing Partially Ranked Data; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985; ISBN 978-0-387-96137-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastle, W.J.; Wierman, M.J. Consensus and dissention: A measure of ordinal dispersion. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2007, 45, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, E.A. Measuring extreme response style. Public Opin. Q. 1992, 56, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, T.; Wolf, M.; Lauer, S.A. Inter-rater reliability and predictive validity. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2008, 61, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.R. On the use of heterogeneous thresholds ordinal regression models to account for individual differences in response style. Psychometrika 2007, 72, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L.; Kotz, S.; Balakrishnan, N. Discrete Multivariate Distributions; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-471-12844-1. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values; Springer: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-1-85233-459-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, L.; Ferreira, A. Extreme Value Theory: An Introduction; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-23946-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Tippett, L.H.C. Limiting forms of the frequency distribution of the largest or smallest member of a sample. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1928, 24, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, R.D.; Thomas, M. Statistical Analysis of Extreme Values: With Applications to Insurance, Finance, Hydrology and Other Fields, 3rd ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 978-3-7643-7230-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirlant, J.; Goegebeur, Y.; Segers, J.; Teugels, J. Statistics of Extremes: Theory and Applications; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-471-97647-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; MacKay, J. The joy of copulas: Bivariate distributions with uniform marginals. Am. Stat. 1986, 40, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F.; Sempi, C. Principles of Copula Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4398-8444-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarta, S.; McNeil, A.J. The t copula and related copulas. Int. Stat. Rev. 2005, 73, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, K.; Czado, C.; Frigessi, A.; Bakken, H. Pair-copula constructions of multiple dependence. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czado, C. Analyzing Dependent Data with Vine Copulas: A Practical Guide with R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-13784-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.H.; Patton, A.J. Modeling dependence in high dimensions with factor copulas. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2017, 35, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermanian, J.D. Goodness-of-fit tests for copulas. J. Multivar. Anal. 2005, 95, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Rémillard, B.; Beaudoin, D. Goodness-of-fit tests for copulas: A review and a power study. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojadinovic, I.; Yan, J. Modeling multivariate distributions with continuous margins using the copula R package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojadinovic, I.; Yan, J. Goodness-of-fit test for multiparameter copulas based on multiplier central limit theorems. Stat. Comput. 2011, 21, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Oualkacha, K. A copula-based set-variant association test for bivariate continuous, binary or mixed phenotypes. Int. J. Biostat. 2023, 19, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petti, D.; Gardini, A.; Belloni, P. Variable selection in bivariate survival models through copulas. In Book of Short Papers CLADAG 2023; Visentin, F., Simonacci, V., Eds.; Pearson: Milano, Italy, 2023; pp. 481–484. Available online: https://repository.essex.ac.uk/36703/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Akpo, T.G.; Rivest, L.P. Hierarchical copula models with D-vines: Selecting and aggregating predictive cluster-specific cumulative distribution functions for multivariate mixed outcomes. Can. J. Stat. 2025, 53, e11830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Hohberger, J. Addressing endogeneity without instrumental variables: An evaluation of the Gaussian copula approach for management research. J. Manage. 2023, 49, 1460–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grübel, R. Ranks, copulas, and permutons: Three equivalent ways to look at random permutations. Metrika 2024, 87, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Ghoudi, K.; Rivest, L.P. A semiparametric estimation procedure of dependence parameters in multivariate families of distributions. Biometrika 1995, 82, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofert, M.; Kojadinovic, I.; Mächler, M.; Yan, J. Elements of Copula Modeling with R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-89635-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, J. Asymptotics of empirical copula processes under non-restrictive smoothness assumptions. Bernoulli 2012, 18, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.F.; Scherer, M. Simulating Copulas: Stochastic Models, Sampling Algorithms, and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84816-874-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.W.; Olkin, I. Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and Its Applications; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-12-473750-1. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, B.C.; Balakrishnan, N.; Nagaraja, H.N. A First Course in Order Statistics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-471-57321-3. [Google Scholar]

- AP News. NCAA College Football Rankings. Available online: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- CFB-HQ On, SI. Coaches Poll Top 25: College Football Rankings 2024 Preseason. Available online: https://www.si.com/fannation/college/cfb-hq/rankings/coaches-poll-top-25-college-football-rankings-2024-preseason (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- College Football Poll. Congrove Computer Rankings. Available online: https://www.collegefootballpoll.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- ESPN. College Football Preseason Power Rankings 2024. Available online: https://www.espn.com/college-football (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kurowicka, D.; Cooke, R.M. Uncertainty Analysis with High Dimensional Dependence Modelling; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-86306-0. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, E.F.; Genest, C.; Nešlehová, J. Beyond simplified pair-copula constructions. J. Multivar. Anal. 2012, 110, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.J. Modelling asymmetric exchange rate dependence. Int. Econ. Rev. 2006, 47, 527–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Year | Primary Focus | What It Does | CDEF’s Unique Addition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copula-Based Set Variant Association Test [56] | 2023 | Genetic association testing | Uses copulas to test association between genetic variants and bivariate phenotypes; handles mixed continuous/binary data | Joint ranking system evaluation: CDEF specifically models concordance, dispersion, and extremeness as interdependent ranking characteristics rather than testing genetic associations |

| Variable Ranking in Bivariate Copula Survival Models [57] | 2023 | Survival analysis variable selection | Applies copula-based variable ranking for bivariate time-to-event data with censoring | System-level analysis: CDEF evaluates ranking system integrity rather than selecting variables; models phantom concordance not visible in survival contexts |

| Hierarchical Copula Models for Clustered Data [58] | 2025 | Hierarchical data modeling | Uses D-vine copulas for hierarchical data with cluster-specific predictions | Ranking-specific framework: CDEF addresses ranking evaluation challenges (concordance artifacts, extremeness bias) not present in general hierarchical modeling |

| Copula Correction Methods [59] | 2023 | Endogeneity correction | Addresses regressor-error correlation using Gaussian copulas in econometric models | Dependence revelation: CDEF reveals hidden dependencies creating phantom properties rather than correcting for known endogeneity |

| Ranks, Copulas, and Permutons [60] | 2024 | Mathematical rank theory | Studies asymptotic properties of random permutations using copula connections | Applied evaluation: CDEF provides practical ranking system diagnostics rather than theoretical permutation analysis |

| Simulation concept in paper | Description (statistic profile) | Code entry point / outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Phantom (Extreme Bias) | High W, very high (shared extreme pattern; tiny swaps) | create_phantom_scenario()→ DataFrame; persisted as scenario_phantom_extreme_bias.xlsx; analyzed by RankDependencyAnalyzer [20,21] |

| Genuine (Natural Agreement) | High W, moderate (moderate perturbations) | create_genuine_scenario()→ DataFrame; file scenario_genuine_natural_agreement.xlsx; same pipeline |

| Random (No Agreement) | Low W, low (independent permutations) | create_random_scenario()→ DataFrame; file scenario_random_no_agreement.xlsx; same pipeline |

| Clustered (Outlier) | High W among 3 raters, one divergent (heterogeneous ) | create_clustered_scenario()→ DataFrame; file scenario_clustered_outlier.xlsx; same pipeline |

| Scenario persistence | Long-format export matching empirical input schema | save_scenario_to_excel(rankings_df, filename, scenario_name) (Rater, Ratee, Ranking) |

| One-pass analysis runner | Runs all scenarios with fixed seed; prints/returns summary | run_cdef_demonstration()→DataFrame summary and console report; saves cdef_summary_fixed.csv |

| Interpretation rule (CDEF) | Maps to narrative class and | cdef_interpretation(results)→; thresholds guided by tail dependence [20,27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).