1. Introduction

The transition towards sustainable construction practices requires the use of locally available materials with low environmental impact, capable of providing satisfactory hygrothermal and mechanical performance. Among these materials, raw earth—used for millennia in various forms (rammed earth, adobe, compressed earth blocks, CEBs)—holds a privileged position due to its low embodied energy, recyclability, and remarkable technical properties, such as high thermal inertia and the ability to regulate indoor humidity [

1,

2].

In tropical humid climates, such as in Benin, daily temperature amplitudes can exceed 10 °C, while relative humidity may vary by more than 40%. These fluctuations represent a dual challenge: they affect both indoor thermal comfort and building durability, but also provide an opportunity to harness the natural regulating properties of raw earth [

3]. Under repeated heat and moisture cycles, coupled heat–moisture transfer phenomena [

4,

5] can alter the microstructure, reduce thermal inertia, and compromise mechanical strength.

Previous studies [

6,

7,

8] have mainly investigated the thermal and hygroscopic properties of CEBs, yet few have experimentally reproduced realistic climatic cycles, particularly under tropical conditions. Moreover, the combined effects of mineral stabilization (cement, slag) and plant fiber reinforcement on the dynamic hygrothermal response of CEBs remain poorly documented, despite evidence that these strategies enhance mechanical strength and mitigate moisture sensitivity [

9,

10,

11].

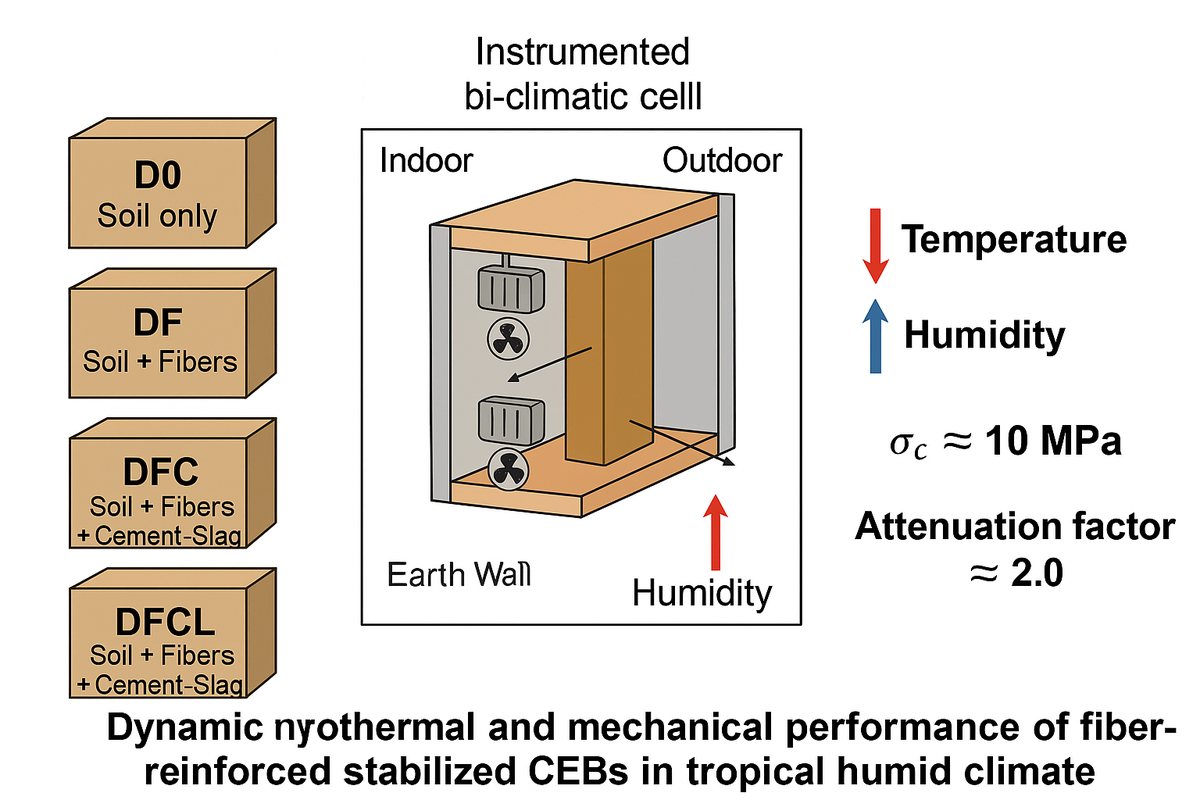

In this context, the present work aims to evaluate the mechanical, hygrothermal, and energy performance of kenaf fiber–reinforced CEB formulations, with a particular emphasis on their suitability for tropical humid climates. The originality of this study lies in:

The diversity of tested formulations, including raw earth, fiber-reinforced earth, and fiber–mineral stabilized composites;

The use of an instrumented bi-climatic cell capable of reproducing realistic temperature and humidity cycles while precisely monitoring dynamic parameters (time lag, attenuation factor);

An integrated evaluation of mechanical, hygrothermal, and energy performance, providing reference data to support the bioclimatic design of sustainable buildings adapted to tropical environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cement used in this study was CPA-CEM I 42.5 ES, composed of 95% clinker and 5% gypsum.

The ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) was produced by ECOCEM France (Fos-sur-Mer) and complies with the European standard NF EN 15167-1:2006. It is classified as Class A slag according to NF EN 206/CN, a classification confirmed on June 28, 2013, by CERIB.

The water used for the mixtures was tap water from the GeM laboratory, containing low sulfate content and having a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C. Its quality meets the requirements of NFP 18-404.

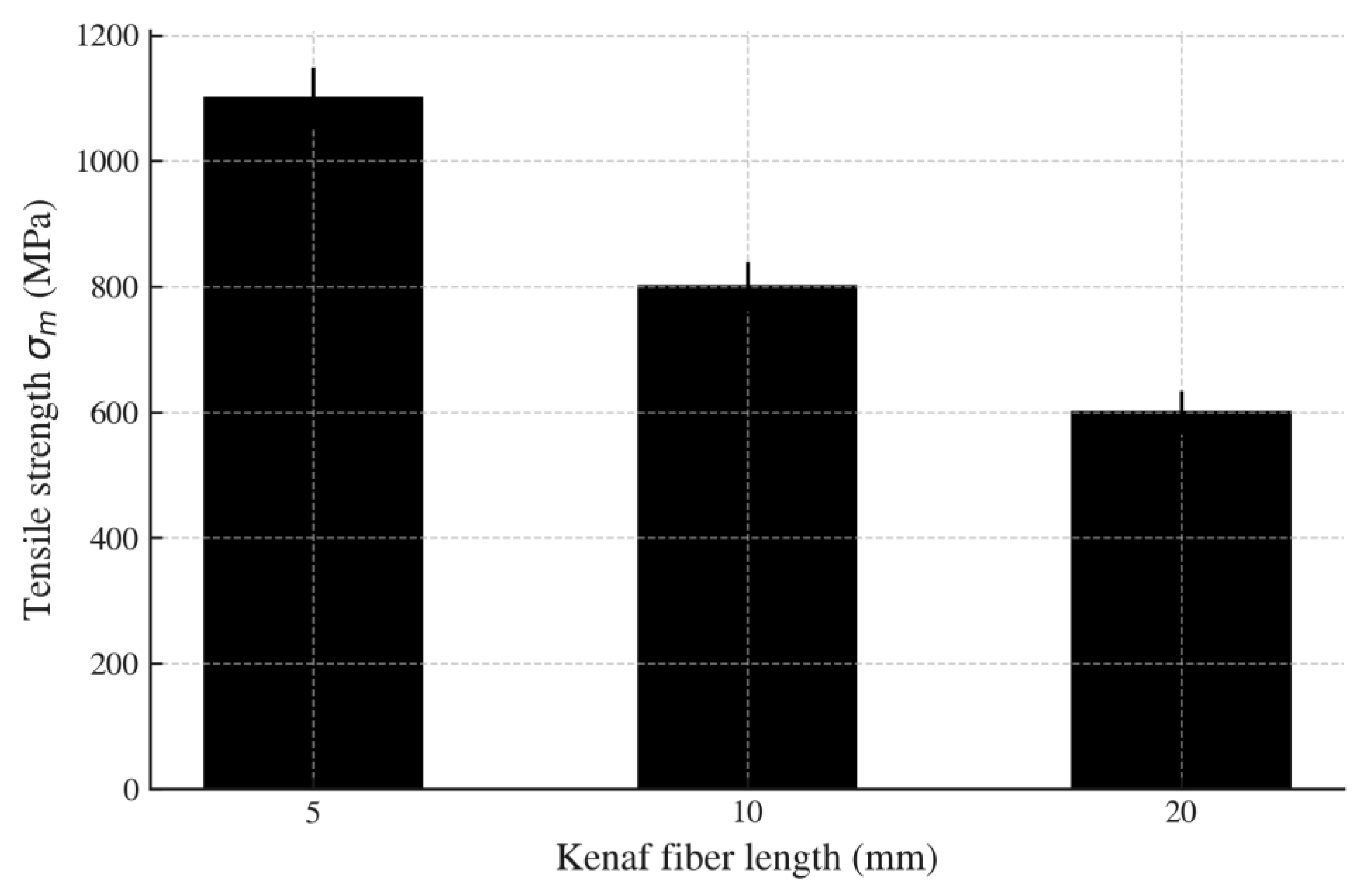

The kenaf plants used originated from Parakou. They were harvested at the age of six months, retted in a river, and manually defibrated. The fibres were cut using a paper cutter to obtain lengths of 10 mm, 20 mm, 30 mm, 40 mm, 50 mm, and 60 mm.The tensile strength of kenaf fibres was determined for each length (see

Figure 1), showing the influence of fibre length on mechanical performance.

The soil used in this study was locally sourced. Its geotechnical properties were as follows:

- Specific gravity: 2.65 g/cm3

- Atterberg limits: Liquid Limit (LL) = 28%, Plastic Limit (PL) = 14%, Plasticity Index (PI) = 14%

- Methylene blue value (VBS): 1.1 g/100 g

- Proctor Normal test: Optimum dry density (ρ_dopt) = 1846 kg/m3; Optimum moisture content (W_opt) = 12%

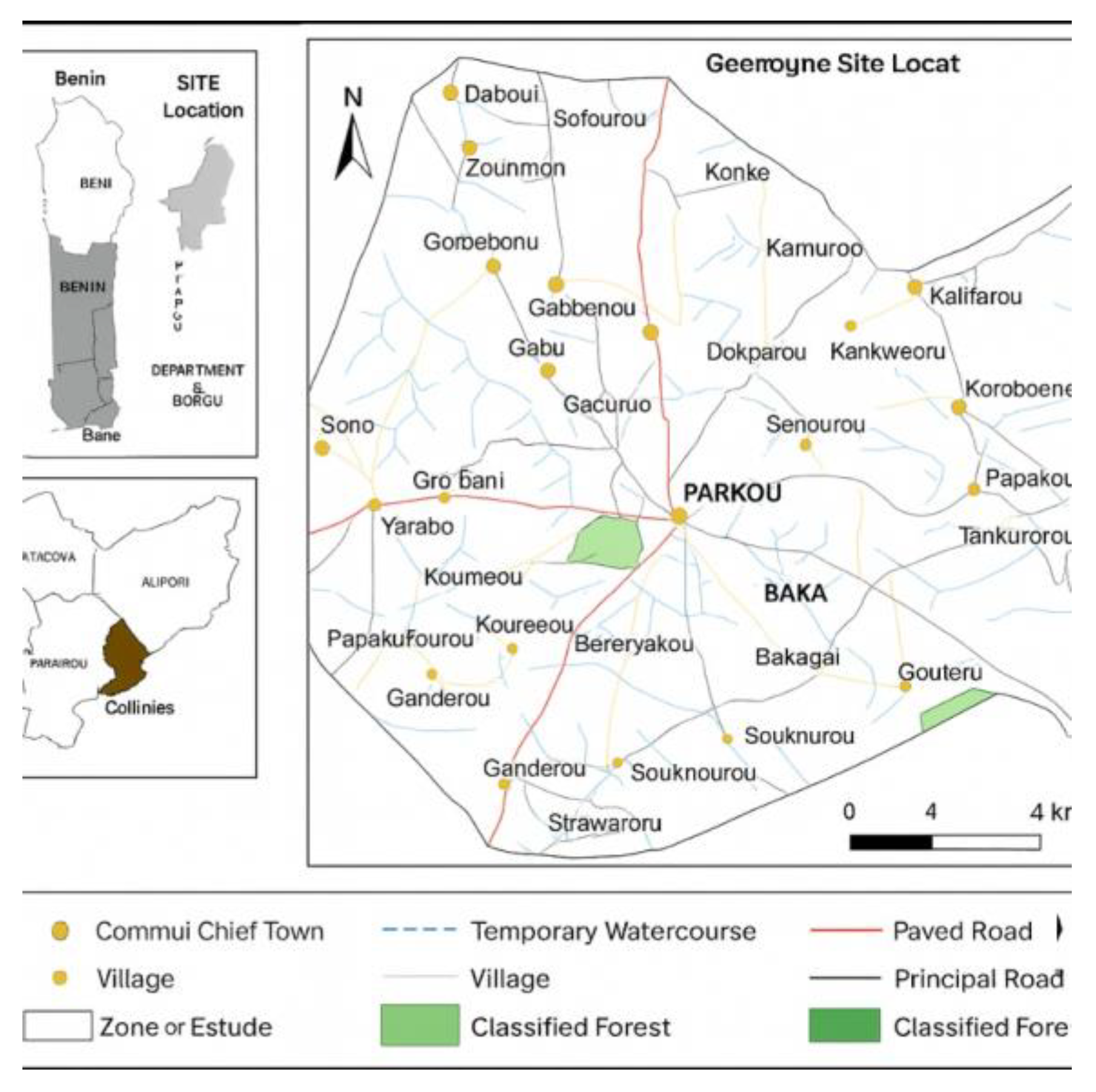

2.1.1. Origin and Characteristics of the Soil

The soil was sourced from the locality of Baka (Parakou, Benin). The sampling was carried out from five pits arranged in a diamond pattern and spaced 100 m apart, following a protocol ensuring the representativeness of the collected material. This clay-rich, Belgian-grey colored soil is traditionally used for the production of adobe bricks and earthen plasters.

Figure 2.

Geographical location of the Baka soil sampling site.

Figure 2.

Geographical location of the Baka soil sampling site.

2.1.2. Particle Size Distribution and Mineralogical Composition

Particle size and mineralogical analyses were performed to characterize the distribution of particles and the nature of mineral constituents, essential information for anticipating the mechanical and hygrothermal behavior of CEBs.

Table 1.

Mineralogical composition of Baka soil.

Table 1.

Mineralogical composition of Baka soil.

| Sample |

Kaolinite (%) |

Illite (%) |

Quartz (%) |

Microcline (%) |

Hematite (%) |

Anatase (%) |

| BAKA |

33.1 |

13.7 |

49.4 |

3.0 |

– |

0.8 |

2.1.3. Tested Formulations

Four optimized formulations were selected:

Table 2.

Composition of the different compressed earth block (CEB) formulations.

Table 2.

Composition of the different compressed earth block (CEB) formulations.

| Designation |

Composition |

| D0 |

Soil only |

| DF |

Soil + 0.5% fibers (30 mm) |

| DFC |

Soil + 7% cement + 0.5% fibers |

| DFCL |

Soil + 10% ground granulated blast furnace slag + 5% cement + 0.5% fibers |

2.2. Block Manufacturing

The masonry units (29.5 × 14 × 9 cm3) were produced using a MecoPress hydraulic press (MecoConcept, France), ensuring uniform compaction.

Table 3.

Technical specifications of the MecoPress used for CEB production.

Table 3.

Technical specifications of the MecoPress used for CEB production.

| Characteristic |

Value |

| Mold changeover time |

15 min |

| Cycle time |

17 s |

| Motor, 230 V single-phase* |

1.5 kW |

| Average consumption |

0.3 kWh−1

|

| Maximum hydraulic pressure |

180 bar |

| Theoretical compression force |

30 tonnes |

Figure 3.

Photograph of the MecoPress press used for the manufacture of CEBs.

Figure 3.

Photograph of the MecoPress press used for the manufacture of CEBs.

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.3.1. Mechanical Testing

ical performance was evaluated through the following tests:

Uniaxial compression tests, conducted in accordance with EN 772-1 (masonry units).

Three-point bending tests, primarily following EN 1052-2 (masonry units). In specific cases, EN 1015-11 was applied, with this choice explicitly justified by the geometry and type of specimens.

For each formulation, six specimens were tested to ensure representative mean values and standard deviations.

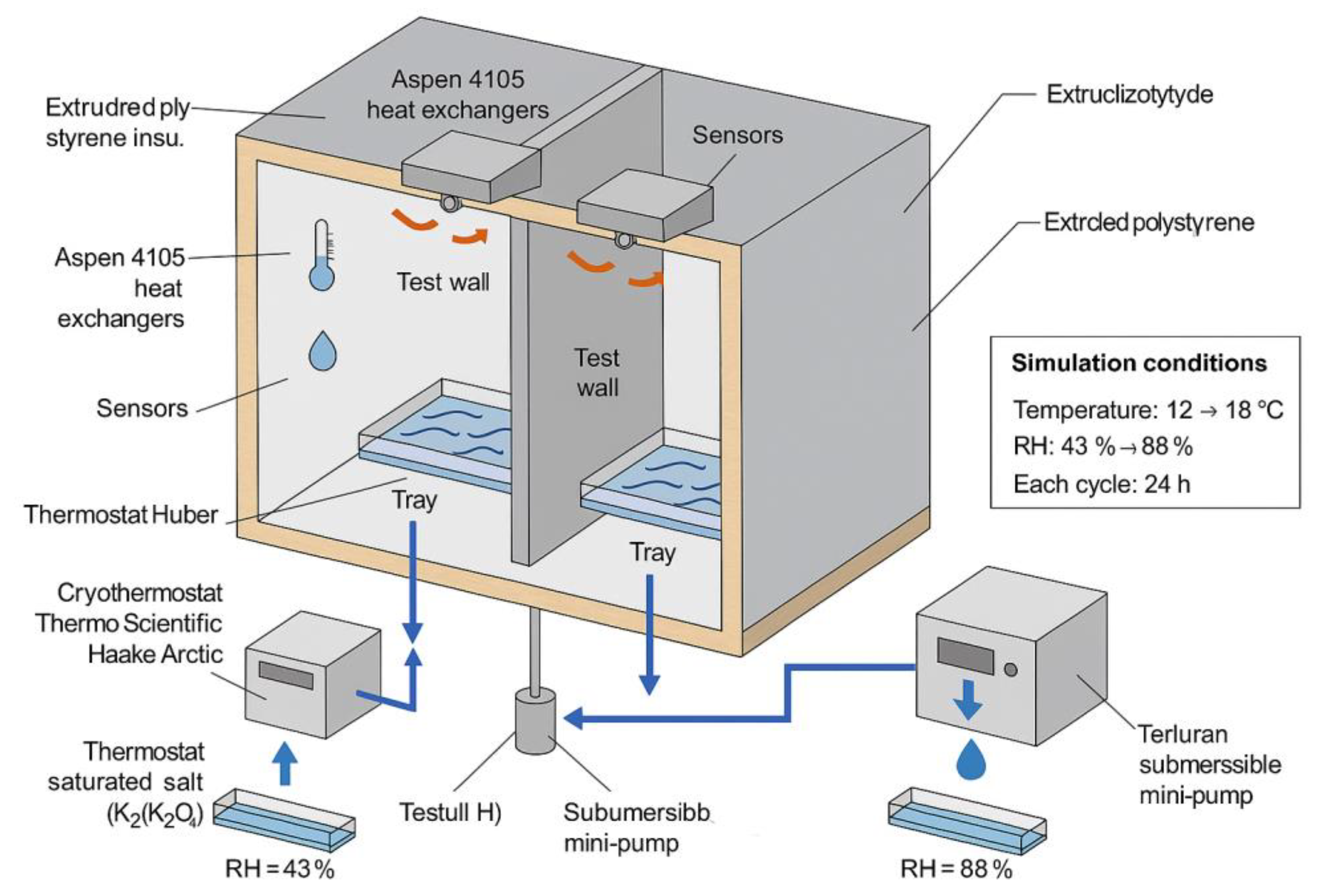

2.3.2. Dynamic Hygrothermal Testing

Hygrothermal performance was evaluated using an instrumented bi-climatic cell specifically designed to reproduce daily temperature and humidity cycles representative of tropical humid climates. The cell consists of two independent compartments (“indoor” and “outdoor”), each measuring 30 × 60 × 50 cm and constructed from bakelized plywood insulated with 6 cm of extruded polystyrene. The compartments are separated by the test wall, which is sealed with Compriband gaskets and laterally insulated with sprayed polyurethane foam to minimize thermal and moisture bridges.

Thermal regulation is ensured by Aspen 4105 heat exchangers mounted on the ceiling of each compartment. Each exchanger is equipped with a fan that promotes air circulation and ensures uniform distribution of temperature and relative humidity. The indoor compartment is connected to a Huber thermostatic bath, maintaining a stable temperature of 23 ± 0.05 °C. The outdoor compartment is connected to a Thermo Scientific Haake Arctic cryothermostat (–10 °C to 100 °C), enabling the simulation of daily cycles. Water circulation between the baths and the exchangers is maintained by a Terluran submersible mini-pump, ensuring a constant flow rate of 5 L/min.

Relative humidity is stabilized by saturated salt solutions placed at the bottom of the compartments: potassium carbonate (K2CO3) for the indoor side (RH ≈ 43%) and potassium chloride (KCl) for the outdoor side (RH ≈ 88%). Each solution covers nearly the entire bottom surface of the compartment, ensuring effective passive regulation.

The simulated outdoor climatic cycles reproduced daily variations of 12–18 °C (temperature) and 43–88% (relative humidity). Each cycle lasted 24 h, alternating between heating–cooling and drying–humidifying phases. A total of 15 consecutive cycles (15 days) was applied for each tested wall. Temperature and relative humidity were monitored at mid-height of both compartments using calibrated sensors (accuracy ±0.1 °C and ±2 %RH). Calibration was performed with saturated salt solutions following Greenspan’s method, with correction for temperature dependence.

The attenuation factor (f) was defined as the ratio between the outdoor amplitude (A_out) and the indoor amplitude (A_in) of the studied variable (temperature or relative humidity):f = A_out / A_in

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the instrumented bi-climatic cell used for hygrothermal testing.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the instrumented bi-climatic cell used for hygrothermal testing.

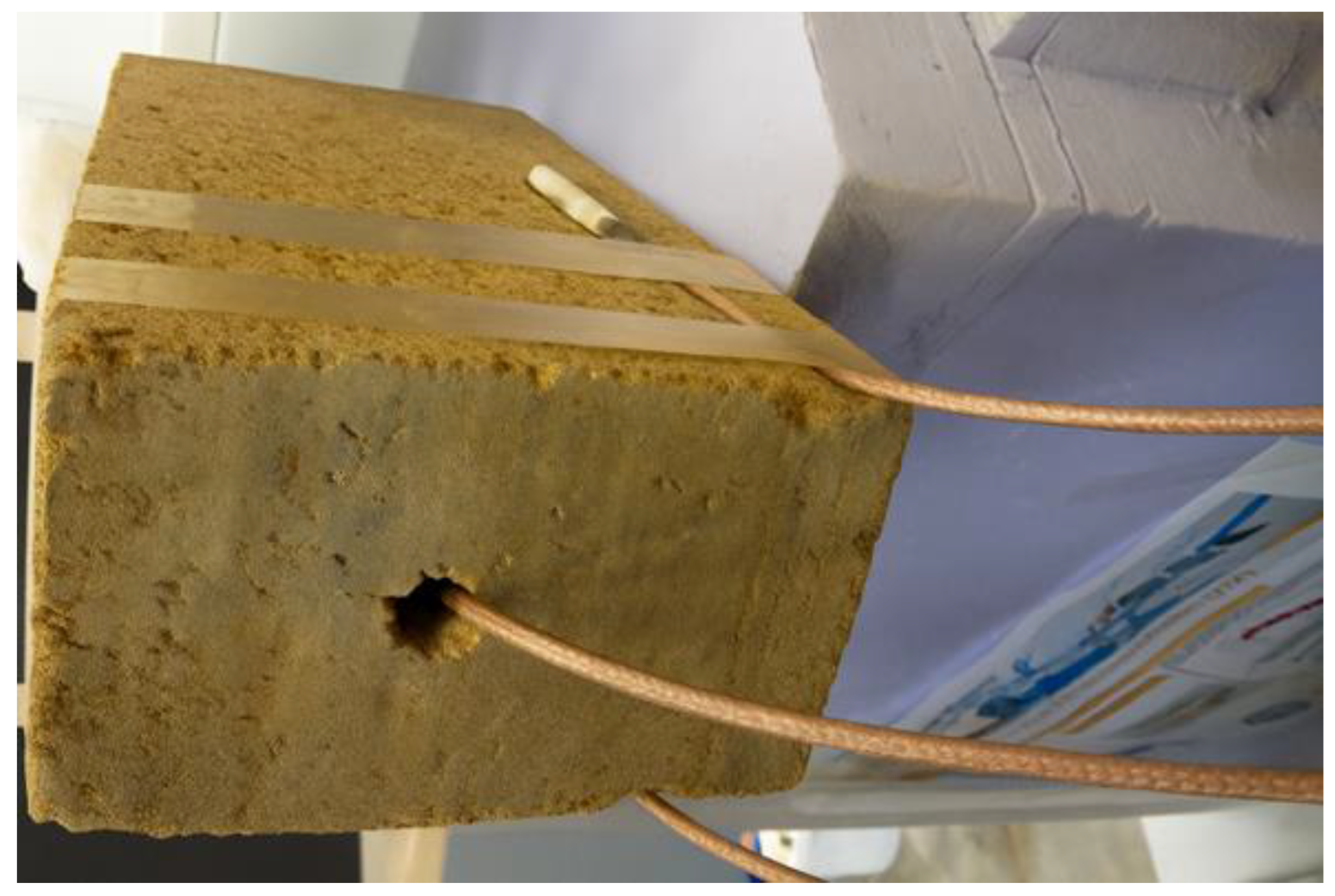

Figure 5.

Photograph of the brick with probes placed in the middle of the wall.

Figure 5.

Photograph of the brick with probes placed in the middle of the wall.

3. Results

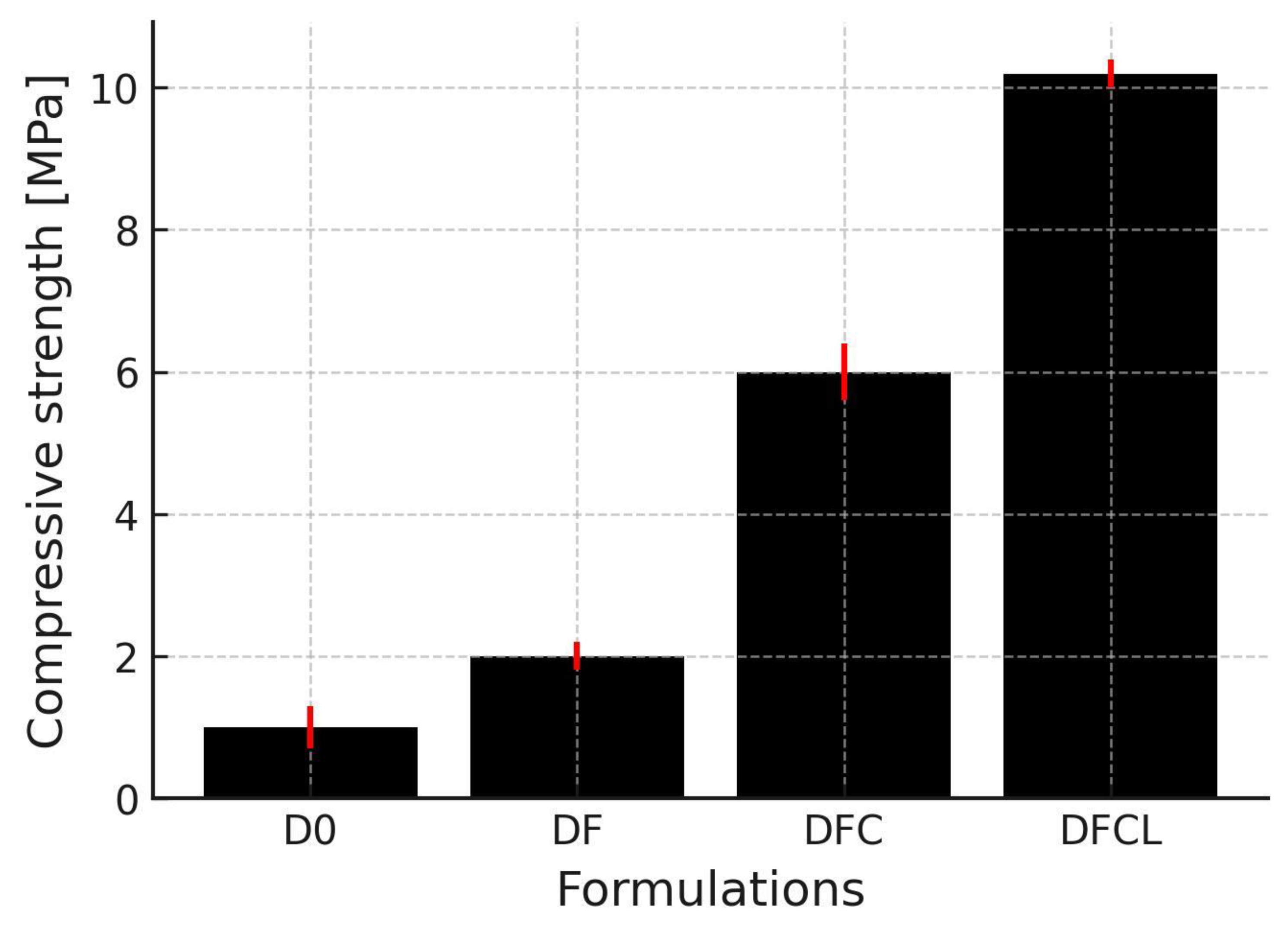

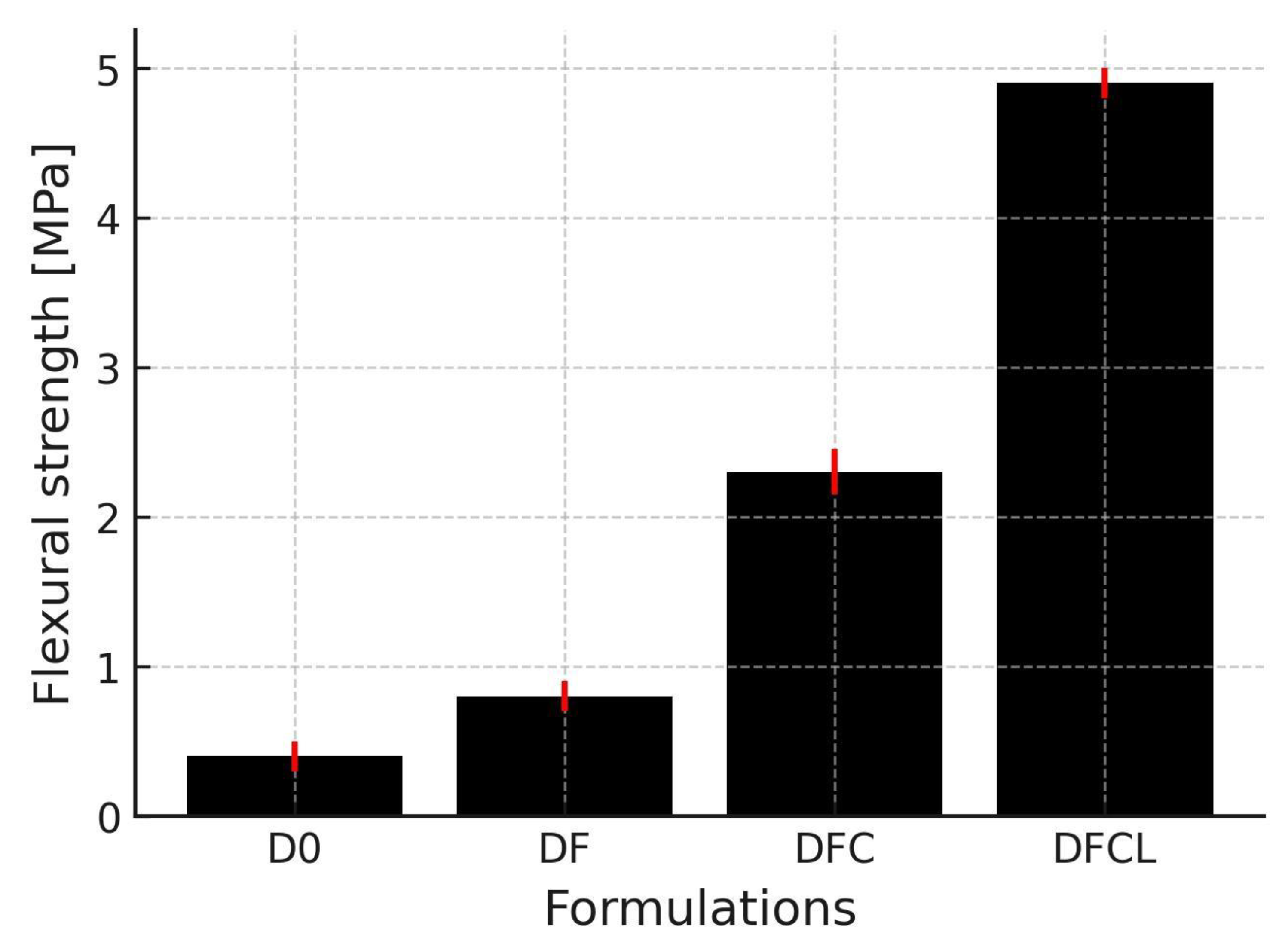

3.1. Mechanical Performance

The uniaxial compression and three-point bending tests revealed marked differences between formulations.

Figure 6.

Variation of the average compressive strength of masonry blocks as a function of the formulations.

Figure 6.

Variation of the average compressive strength of masonry blocks as a function of the formulations.

Figure 7.

Variation of the three-point flexural strength of masonry blocks according to the formulations.

Figure 7.

Variation of the three-point flexural strength of masonry blocks according to the formulations.

The mechanical performance of the different formulations is summarized below:

D0 (soil only): The reference formulation exhibited moderate compressive strength, which remains insufficient for multi-story construction.

DF (soil + fibers): The incorporation of natural fibers produced a slight improvement in strength compared to D0, with compressive strength reaching approximately 6 MPa. This enhancement can be attributed to the fiber-bridging mechanism, which helps limit crack propagation and delay failure.

DFC (soil + fibers + cement): The addition of cement as a mineral stabilizer led to a marked increase in both compressive and flexural strength, with values exceeding the regulatory thresholds for buildings up to R+1.

DFCL (soil + fibers + cement + slag): This formulation achieved the best overall performance, with a compressive strength of about 10 MPa—nearly twice that of DF—and improved toughness. The combined presence of cement and slag promoted matrix densification, while fibers contributed to crack control and energy absorption.

Statistical analysis confirmed the significance of these differences: a one-way ANOVA indicated that the mechanical strength of the formulations differed significantly (p < 0.05).

Overall, the results demonstrate that combining mineral stabilization with fiber reinforcement is highly effective in optimizing the mechanical performance of compressed earth blocks. Cement and slag enhance load-bearing capacity through densification of the matrix, while fibers play a structural role in crack control, resulting in improved toughness and durability.

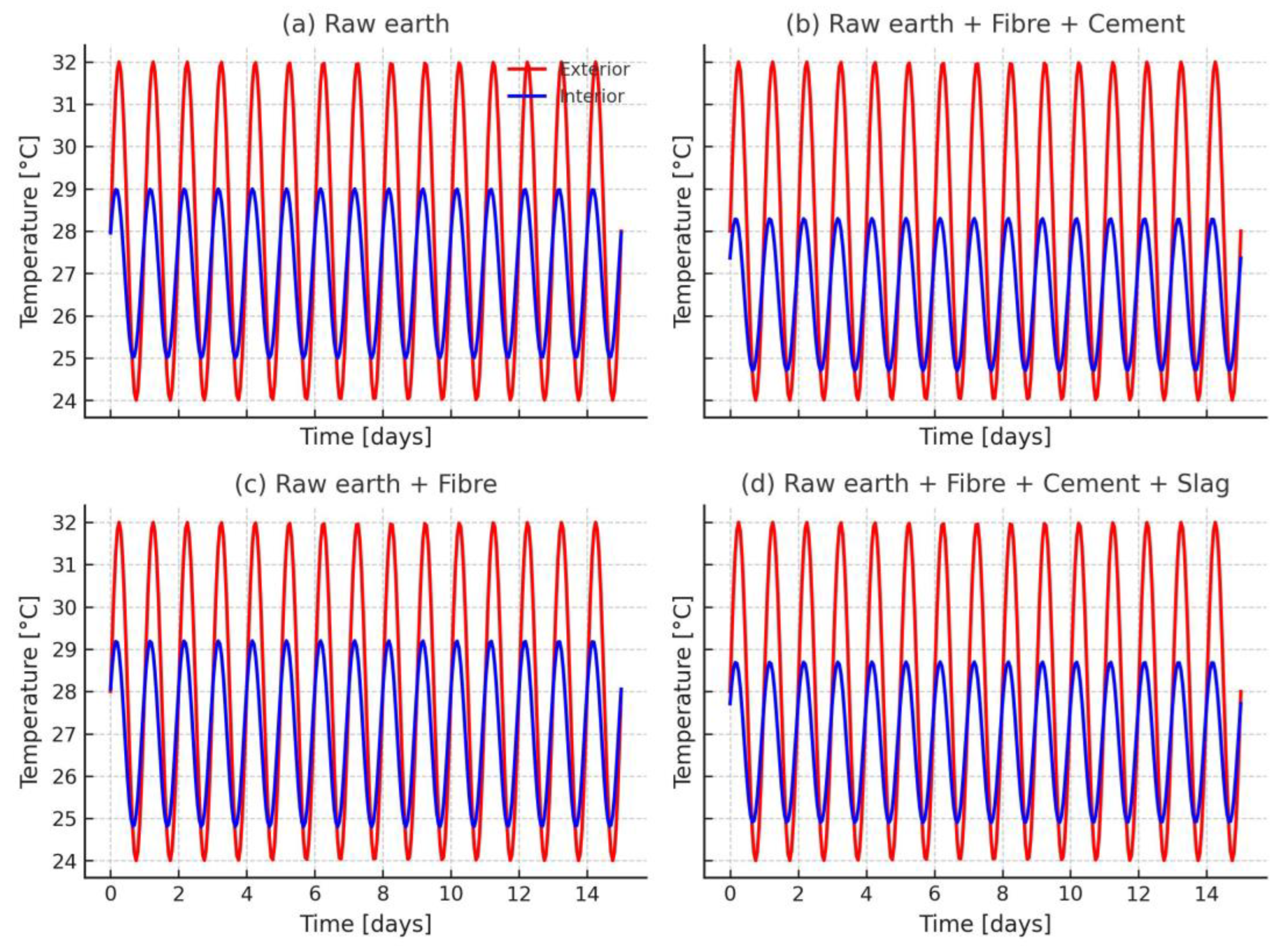

3.2. Dynamic Thermal Behavior

Analysis of temperature recordings (

Figure 8) shows:

- A thermal time lag for all formulations, indicating thermal inertia.

- Attenuation of indoor amplitudes compared to outdoor variations.

Performance ranking:

DFCL and DFC: Strong attenuation of temperature peaks, moderate time lag.

DF: Intermediate attenuation, greater time lag than stabilized formulations.

D0: Low attenuation, limited time lag, indoor temperature close to outdoor variations.

Table 4.

Thermal performance indicators of the CEB walls.

Table 4.

Thermal performance indicators of the CEB walls.

| Formulation |

Time lag (h) |

Attenuation factor (–) |

| Soil only (D0) |

0.95 |

1.19 |

| Soil + fibers (DF) |

1.15 |

1.72 |

| Soil + fibers + cement (DFC) |

0.80 |

1.58 |

| Soil + fibers + cement + slag (DFCL) |

0.90 |

2.24 |

Observed trend: Stabilized formulations have better attenuation but reduced time lag, while fiber-only formulations maintain more marked inertia.

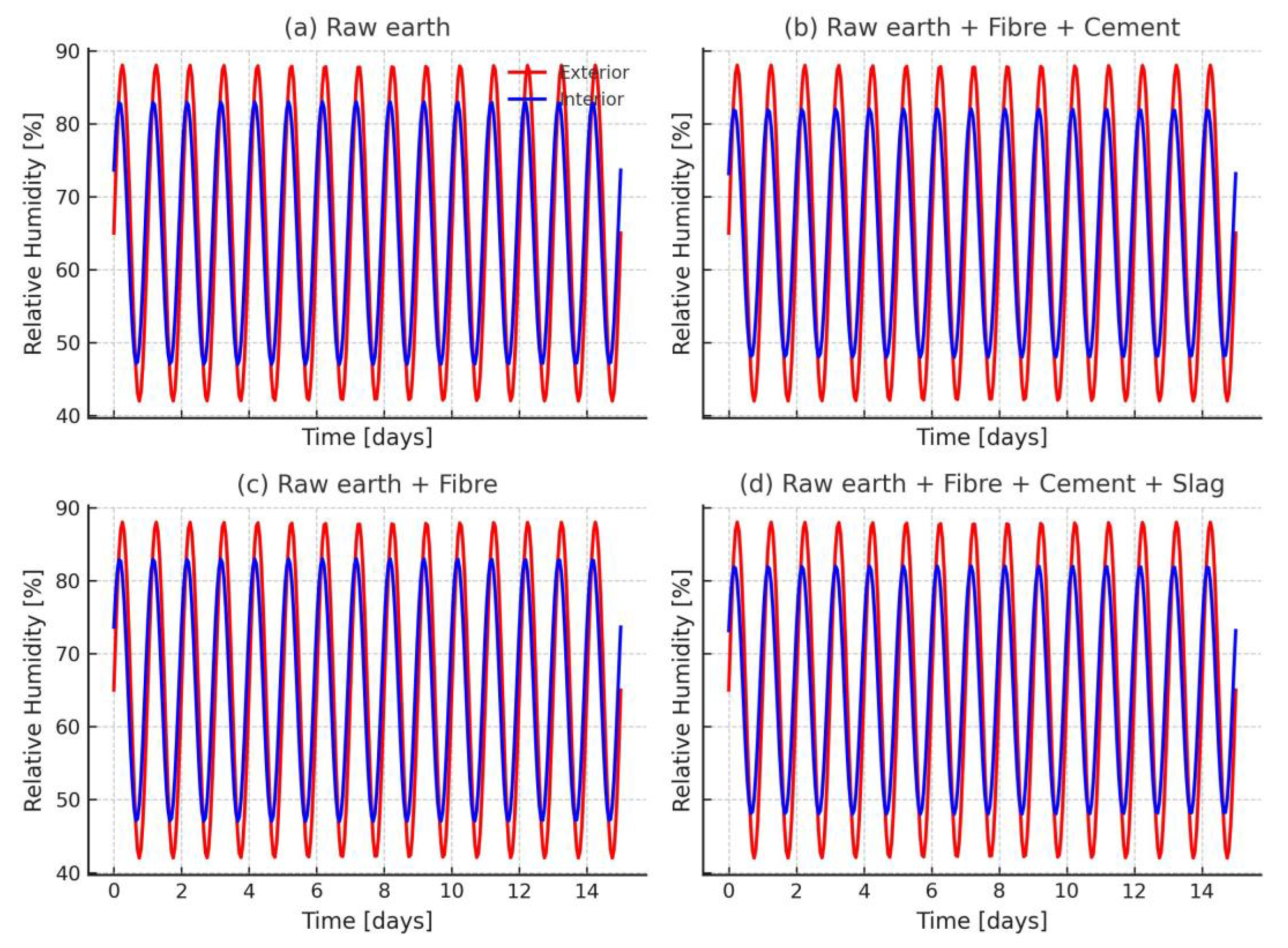

3.3. Dynamic Hygroscopic Behavior

Relative humidity measurements (

Figure 9) highlight:

- A hygroscopic time lag between outdoor and indoor conditions.

- Attenuation of internal variations, confirming the hygroscopic capacity of CEBs.

Performance ranking:

DFCL and DFC: High hygroscopic attenuation, linked to low water vapor permeability.

DF: Moderate attenuation, but good balance between regulation and wall breathability.

D0: Low attenuation, high permeability, variations close to outdoor.

Table 5.

Hygrothermal performance indicators of the CEB walls.

Table 5.

Hygrothermal performance indicators of the CEB walls.

| Formulation |

Time lag (h) |

Attenuation factor (–) |

| Soil only (D0) |

1.63 |

1.69 |

| Soil + fibers (DF) |

1.64 |

1.75 |

| Soil + fibers + cement (DFC) |

1.13 |

1.99 |

| Soil + fibers + cement + slag (DFCL) |

1.10 |

2.05 |

Key observation: Stabilized formulations offer more effective hygroscopic regulation, but at the cost of reduced wall breathability.

Observation: DFCL and DFC offer high hygroscopic attenuation, associated with low water vapor permeability; DF maintains a balance between regulation and breathability; D0 shows low attenuation and high permeability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interactions Between Mechanical and Hygrothermal Performance

The results confirm a strong interdependence between mechanical and hygrothermal properties. Formulations stabilized with cement and/or slag, combined with plant fiber reinforcement, exhibit the highest compressive and flexural strengths, exceeding the thresholds required for buildings up to R+1 (ISO 17892-7). This improvement results from the densification of the matrix by hydraulic binders, reducing porosity and increasing internal cohesion, as well as from the bridging effect of fibers, which limits crack propagation and improves toughness (Sidiki et al., 2024).

However, this densification reduces water vapor permeability and thus limits hygroscopic regulation. Fiber-only formulations, although less mechanically performant, maintain higher open porosity, favoring wall breathability and improving thermal comfort in naturally ventilated buildings (Aman et al., 2023; Nguimfack et al., 2024).

4.2. Dynamic Thermal Behavior

The analysis of temperature variations shows:

- A thermal time lag between the exterior and the interior for all formulations.

- Attenuation of interior temperature amplitudes compared to the exterior.

In the morning, the rise in indoor temperature is delayed; in the evening, cooling is delayed, reflecting the thermal inertia effect of CEBs.

Comparatively:

D0 (soil only): Moderate time lag, low attenuation; indoor temperature closely follows external variations.

DF (soil + fibers): More marked attenuation and improved thermal inertia.

DFC and DFCL (soil + fibers + stabilizers): High attenuation but lower time lag, probably linked to higher thermal conductivity and reduced porosity.

Implication: Fiber-only formulations effectively reduce daily variations, while stabilized formulations better smooth temperature peaks but react more quickly to changes. This finding matches observations by Chraibi et al. (2023) on the antagonistic density–time lag relationship.

4.3. Dynamic Hygroscopic Behavior

Relative humidity measurements reveal:

- A hygroscopic time lag between exterior and interior conditions.

- Attenuation of internal variations, confirming the hygroscopic capacity of CEBs.

In the humid phase, the indoor increase is delayed; in the dry phase, the moisture release is gradual, contributing to the stabilization of the indoor climate.

Comparatively:

D0: Low attenuation, high permeability, variations close to the exterior.

DF: Better attenuation thanks to the fibrous microstructure temporarily retaining moisture.

DFC and DFCL: High hygroscopic attenuation, linked to low vapor permeability, but possibly causing prolonged moisture retention.

Implication: DF offers an interesting compromise for naturally ventilated buildings, while DFC and DFCL are better suited for configurations requiring stable humidity levels, provided that the risk of residual moisture is controlled.

4.4. Synthesis and Implications for Bioclimatic Design

The results highlight a formulation–use compromise:

DFC and DFCL: Suitable for buildings with high thermal inertia and limited ventilation, allowing temperature peaks to be delayed and passive comfort to be optimized.

DF: Preferable for naturally ventilated buildings, where wall breathability is essential.

The choice of formulation must integrate the ventilation mode, structural requirements, and local climatic conditions, in line with the principles of bioclimatic design for hot and humid climates.

4.5. Research Perspectives

The perspectives include:

- Long-term aging: evaluating the effect of prolonged cycles (wetting–drying, freeze–thaw) on performance (Abdallah et al., 2024).

- Fiber optimization: type, length, and treatment, to maximize mechanical and hygroscopic effects (Nguimfack et al., 2024).

- Multi-physics modeling: combining experimental data and simulations to predict building-scale behavior (Hany et al., 2025).

- Local valorization: integrating binders and fibers from agro-industrial waste to strengthen the environmental sustainability and socio-economic impact of CEBs (Aman et al., 2023).

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated, under controlled conditions, the mechanical and dynamic hygrothermal behavior of compressed earth block (CEB) walls subjected to climatic cycles representative of a tropical humid environment. Four formulations, combining or not mineral stabilization and fiber reinforcement, were compared.

Main results:

- Mechanical performance – Formulations stabilized with cement and/or slag, combined with plant fiber reinforcement, present the highest strengths, exceeding the regulatory thresholds for buildings up to R+1.

- Thermal performance – DFCL and DFC ensure strong attenuation of temperature variations, improving indoor comfort and reducing air conditioning needs.

- Hygroscopic performance – Stabilized formulations effectively limit indoor humidity variations, while fiber-only formulations offer a good balance between hygroscopic regulation and water vapor permeability.

Scientific contributions:

- Experimental demonstration, in a bi-climatic cell, of the combined impact of mineral stabilization and fiber reinforcement on mechanical and hygrothermal performances.

- Integrated analysis of thermal and hygroscopic performance, rarely addressed jointly in the literature.

- Identification of formulation–use compromises, useful for bioclimatic design in tropical climates.

Perspectives

- Evaluate the long-term hygrothermal aging of CEBs in real conditions.

- Develop multi-physics numerical models integrating experimental data to predict behavior at the building scale.

- Explore the use of fibers and binders from local agro-industrial waste to reinforce the eco-responsible and socio-economic dimension of CEBs.

In conclusion, DFCL blocks combined high mechanical strength (σc ≈ 10 MPa) with superior hygrothermal regulation (thermal attenuation factor 2.24, hygroscopic attenuation factor 2.05, with time lags of ~0.9 h and ~1.1 h, respectively). These findings demonstrate their potential for sustainable construction in tropical humid climates, particularly for load-bearing walls up to R+1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Armel B. Laibi and Philippe Poullain; Methodology, Armel B. Laibi, Philippe Poullain, and Nordine Leklou; Software, Armel B. Laibi; Validation, Philippe Poullain, Nordine Leklou, and Moussa Gomina; Formal Analysis, Armel B. Laibi; Investigation, Armel B. Laibi; Resources, Philippe Poullain and Moussa Gomina; Data Curation, Armel B. Laibi; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Armel B. Laibi; Writing—Review & Editing, Philippe Poullain, Nordine Leklou, and Moussa Gomina; Visualization, Armel B. Laibi; Supervision, Philippe Poullain and Nordine Leklou; Project Administration, Philippe Poullain; Funding Acquisition, Philippe Poullain and Moussa Gomina. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Service for Cooperation and Cultural Action (SCAC) of the French Embassy in Benin. The work was carried out at the GeM laboratory in Saint-Nazaire, France.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Ahmed Loukili (Director of the GeM UMR CNRS 6183) and Professor Ouali Amiri (Deputy Director of the GeM for the Saint-Nazaire site) for their welcome and logistical support at the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y. , et al. (2024). A review of the hygrothermal and mechanical properties of compressed earth blocks: Towards sustainable building envelopes. Buildings, 14(2), 411. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. , & Allinson, D. (2009). Hygrothermal properties of stabilised and unstabilised earth: A comparative review. Building and Environment, 44(9), 1935–1942. [CrossRef]

- Little, B. , & Morton, T. (2001). Building with Earth in Scotland: Innovative Design and Sustainability. Scottish Executive Central Research Unit.

- Hagentoft, C.-E. (2001). Introduction to Building Physics. Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- Künzel, H. M. (1995). Simultaneous Heat and Moisture Transport in Building Components. Fraunhofer IRB Verlag, Stuttgart.

- Chraibi, M., et al. (2023). Effect of olive waste additives on the thermal properties of compressed earth blocks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 65234–65247. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, R. , et al. (2024). Hygrothermal behaviour of raw earth building materials: Insights from the DuReTerre program. In Advances in Hygrothermal Performance of Sustainable Building Materials (pp. 715–728). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Mounir, K., et al. (2024). Mechanical and hygrothermal performance of stabilized compressed earth blocks. Construction and Building Materials, 412, 133620. [CrossRef]

- Nguimfack, F. T., Ndzana, M., & Elenga, H. (2024). Mechanical performance of compressed earth bricks reinforced with natural plant fibers in Cameroon. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 9(2), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Aman, A. , et al. (2023). Coconut fiber reinforced compressed earth blocks: Hygrothermal characterization. Journal of Building Engineering, 65, 105963. [CrossRef]

- Sidiki, A.; Chantit, F. Physical, Mechanical, and Durability Properties of Compressed Earth Blocks Filled by Juncus Plant Fibers. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2024, 42, 194–205. Available online: https://issr-journals.org/xplore/ijias/0042/001/IJIAS-24-004-09.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Abdallah, H., et al. (2024). Impact of compaction pressure on thermal stability of compressed earth blocks. Materials and Structures, 57(2), 45. [CrossRef]

- Hany, M., et al. (2025). Energy performance modeling of compressed earth block buildings under varying climatic conditions. International Journal of Civil Structural Materials, 11(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Njoya, A. , et al. (2024). Physical and mechanical properties of stabilized compressed earth blocks incorporating sawdust as a bio-based additive. In Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies (pp. 301–314). Springer. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).