Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

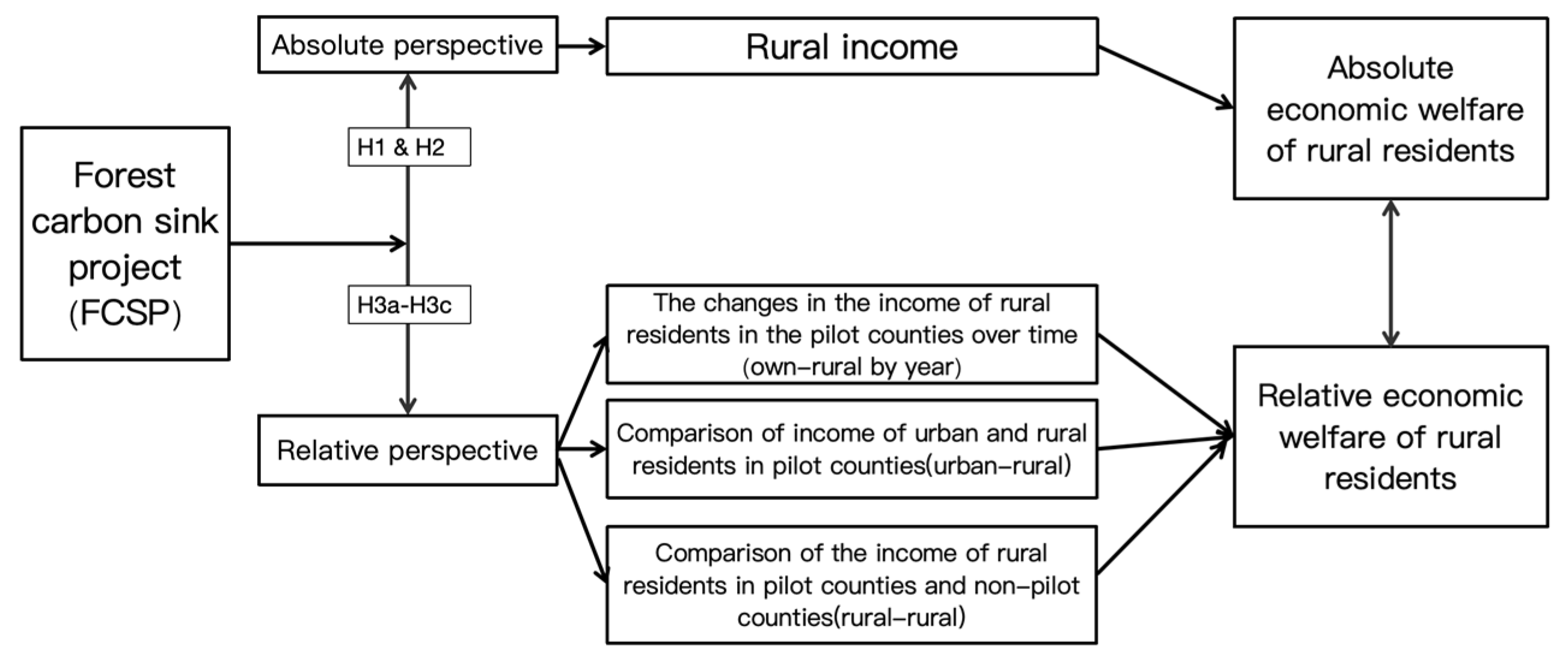

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Positive Impact of FCSP on the Economic Welfare of Rural Residents from an Absolute Perspective

2.2. The Negative Impact of FCSP on the Economic Welfare of Rural Residents from an Absolute Perspective

2.3. The Impact of FCSP on the Economic Welfare of Rural Residents from a Relative Perspective

2.3.1. Longitudinal Comparison Between Individuals

2.3.2. Rural-Rural Comparison Between Groups

2.3.3. Urban-Rural Comparison Between Groups

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Economic Welfare Measurement Method of Rural Residents from a Relative Perspective

3.1.1. Calculation Methods for Vertical Comparison, Rural-Rural Comparison, and Urban-Rural Comparison

3.1.2. The General Form of the Economic Welfare Function for Residents in Project Areas

3.1.3. The Specific Form of the Economic Welfare Function in Project Areas

3.2. An Empirical Model for Analyzing the Impact of FCSP on the Economic Welfare of Rural Residents

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

- 2.

- Difference in Difference model (DID)

3.3. Data Description, Data Source and Variable Selection

- Data description

- 2.

- Data source

- 3.

- Variable selection

4. Empirical Results

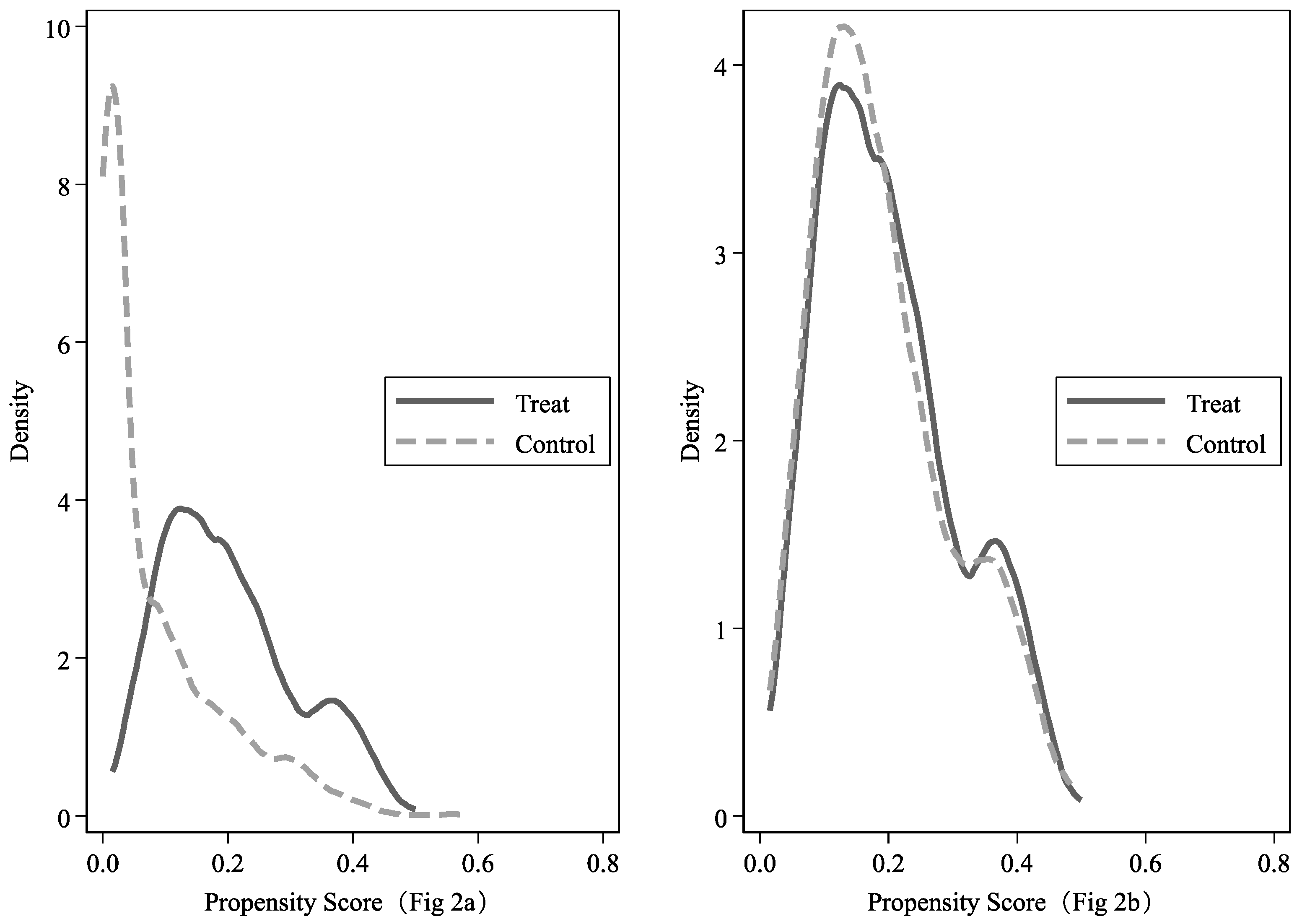

4.1. Model Testing

4.1.1. Balance Test

4.1.2. Balance Test

4.2. The Utility of Rural Residents’Economic Welfare and Welfare Loss Considering Relative Factors

4.3. Economic Welfare Effects of FCSP on Rural Residents

4.4. Dynamic Effects of FCSP on Rural Residents’ Economic Welfare

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Different Project Cycles

4.5.2. Different Poverty Attributes

4.5.3. Different Ethnic Attributes

| Non-ethnic country | Ethnic country | |||

| W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | |

| DID | 0.236*** | 0.019 | -0.062 | -0.284*** |

| (0.047) | (0.084) | (0.060) | (0.069) | |

| _cons | 8.539*** | 7.667*** | 8.244*** | 7.364*** |

| (0.117) | (0.209) | (0.155) | (0.178) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 525 | 525 | 654 | 654 |

| R2 | 0.717 | 0.539 | 0.461 | 0.415 |

| Non-ethnic country | Ethnic country | |||||

| U-R | R-R | H-H | U-R | R-R | H-H | |

| DID | 0.025 | 0.130*** | -0.107 | -0.120*** | 0.176*** | -0.234*** |

| (0.025) | (0.031) | (0.107) | (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.055) | |

| _cons | 0.591*** | 0.045 | 0.817*** | 0.722*** | 0.485*** | 0.733*** |

| (0.063) | (0.076) | (0.265) | (0.067) | (0.071) | (0.143) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 525 | 525 | 525 | 654 | 654 | 654 |

| R2 | 0.091 | 0.409 | 0.131 | 0.208 | 0.379 | 0.149 |

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Contributions and INNOVATIONS

5.1.1. Contributions

5.1.2. Innovations

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Research Directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y. Research on the Operation Mechanism of Forest Carbon Sink Trading Pilot in China. Issues in Agricultural Economy 2014, 35, 73–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Y.; He, Y. Overview of Climate Change and Carbon Sink Forestry. Development Research, 2009, 95-97. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, R.; Zhuang, C.; Deng, Y. Urban Forest Carbon Sink and Its Effect on Offsetting Energy Carbon Emissions—A Case Study of Guangzhou. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2013, 33, 5865–5873. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, R.; Kerr, J. M.; Carter, S. Reducing Poverty Through Carbon Forestry? Impacts of the N’hambita Community Carbon Project in Mozambique. World Development 2012, 40, 2123–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Forest Carbon Sink and Farmers’Livelihood—A Case Study of the World’s First Forest Carbon Sink Project. World Forestry Research 2010, 23, 15–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Fu, X. A Review of Forest Carbon Sink Research from the Perspective of Poverty Alleviation. Issues in Agricultural Economy 2017, 38, 102–109+103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zeng, W. Review and Prospect of China’s Forest Carbon Sink Market. Resource Development&Market 2014, 30, 603–606. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Bai, J. Analysis of the Impact of Risk Preferences of Forest Farmers in Southern Collective Forest Areas on Carbon Sink Supply Willingness—A Risk Preference Experiment Case in Zhejiang Province. Resources Science 2016, 38, 565–575. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Willingness of Forest Farmers to Participate in Forestry Carbon Sinks—Based on Collective Forest Survey Data in Heilongjiang Province. Forestry Economics 2018, 40, 98–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, W. Do Forest Farmers Have the Willingness to Participate in Forestry Carbon Sink Projects? —Taking CDM Forestry Carbon Sink Pilot Project as an Example. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics, 2015, 102-11. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Silva, C. A.; Hudak, A. T.; Vierling, L. A.; Loudermilk, E. L.; O’Brien, J. J.; Hiers, J. K.; Jack, S. B.; Gonzalez-Benecke, C.; Lee, H.; Falkowski, M. J. Imputation of individual longleaf pine(Pinus palustris Mill. ) tree attributes from field and LiDAR data. Canadian journal of remote sensing 2016, 42, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Forest Carbon Sink and Farmers’Livelihood—A Case Study of the World’s First Forest Carbon Sink Project. World Forestry Research 2010, 23, 15–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P. B. Assessing sensitivity of hydrologic responses to climate change from forested watershed in Mississippi. Hydrological Processes 2010, 24, 3785–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, K.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Z. Analysis of Farmers’Cognition of Forest Carbon Sinks and Their Willingness to Manage Carbon Sink Forests—Based on Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang, Jiangxi, and Fujian Provinces. Journal of Beijing Forestry University(Social Sciences) 2014, 13, 63–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhuang, T. Forest Farmers’Willingness for Continuous Participation in Forest Carbon Sink Projects and Its Influencing Factors. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 2016, 52, 138–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.; Zeng, W. Constraints on Farmers’Participation in Forest Carbon Sink Projects under Government Promotion. Resources Science 2018, 40, 1073–1083. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Q. Analysis of Factors Affecting Forest Farmers’Willingness to Receive Compensation for Carbon Sink Forest Management—Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Forestry Economics 2017, 39, 46–52+91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. R.; Stokes, C. A review of forest carbon sequestration cost studies: A dozen years of research. Climatic Change 2004, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, B. K.; Kousky, C.; Sims, K. Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentive-based mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 9465–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmann, H.; Delhey, J.; Welzel, C.; Hao, Y. The China Puzzle: Falling Happiness in a Rising Economy. Journal of Happiness Studies 2009, 10, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zeng, W. Do Carbon Sink Afforestation Projects Promote Local Economic Development? —An Empirical Study Based on County-Level Panel Data in Sichuan Using PSM-DID. China Population, Resources and Environment 2020, 30, 89–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pagiola, S. Payments for Environmental Services in Costa Rica.2006.

- Hejnowicz, A. P.; Hilary, K.; Rudd, M. A.; Huxham, M. R. Harnessing the climate mitigation, conservation and poverty alleviation potential of seagrasses: prospects for developing blue carbon initiatives and payment for ecosystem service programmes. Frontiers in Marine Science 2017, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K. The Social Welfare Effects of Rural-to-Urban Farmland Transfer. PhD Dissertation, Huazhong Agricultural University, 2008. (In Chinese).

- Grieg-Gran, M.; Porras, I.; Wunder, S. How can market mechanisms for forest environmental services help the poor? Preliminary lessons from Latin America. World Development 2005, 33, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli; Rajan; Lamichhane; Dhananjaya; Joshi; Omkar. Does Nepal’s community forestry program improve the rural household economy? A cost-benefit analysis of community forestry user groups in Kaski and Syangja districts of Nepal. J FOREST RES-JPN.

- Mchenry, M. P. Agricultural bio-char production, renewable energy generation and farm carbon sequestration in Western Australia: Certainty, uncertainty and risk. Agriculture Ecosystems&Environment 2009, 129, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M. S. Farm diversification into tourism-Implications for social identity? Journal of Rural Studies 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konu, H. Developing a forest-based wellbeing tourism product together with customers–An ethnographic approach. Tourism Management 2015, 49, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z. J.; Chazdon, R. L. Beyond carbon: Redefining forests and people in the global ecosystem services market. Sapiens 2012, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, P. J.; Hanauer, M. M.; Miteva, D. A.; Nelson, J. L.; Pattanayak, S. K.; Nolte, C.; Sims, K. R. E. Estimating the impacts of conservation on ecosystem services and poverty by integrating modeling and evaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 7420–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, W.; Yang, F. Ecological Compensation for Forest Carbon Sink Afforestation in China Based on Hicks Analysis—Taking Land Use Change from”Pastureland to Carbon Sink Forest Land”as an Example. Science and Technology Management Research 2016, 36, 221–227. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ming, H.; Yu, W. Comparative Analysis of the Implementation of Forestry Carbon Sink Projects in Sichuan Province. Journal of Sichuan Agricultural University 2015, 33, 332–337. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, N. M.; Ríos, M. T. V.; Smith, J. Can Forest-protection carbon projects improve rural livelihoods? Analysis of the Noel Kempff Mercado climate action project, Bolivia. Mitigation&Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2002, 7, 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Huo, X.; Du, W. Absolute Income, Social Comparison and Farmers’Subjective Well-being—An Empirical Study Based on Two Entire Villages in Shaanxi. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics, 2018, 111-125. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Fang, M.; Fu, L.; Jin, X. Objective Relative Income and Subjective Economic Status: Empirical Evidence from a Collectivist Perspective. Economic Research 2019, 54, 118–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, A. J. HAPPINESS AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE. The Economic Journal 1997. [CrossRef]

- Duesenberry, J. S. Income, Saving, and the Theory of Consumer Behavior. Review of Economics&Statistics 1949, 33, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Parijat, P.; Bagga, S. Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory of motivation–An evaluation. International Research Journal of Business and Management 2014, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.; Cheng, R.; Zeng, M.; Zeng, W. Analysis of Poverty Alleviation Effect of Forest Carbon Sink Based on Farmers’Perception. South China Journal of Economics, 2019, 84-96. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human relations 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, R.; Swallow, B.; Kerr, J. Forestry-based carbon sequestration projects in Africa: Potential benefits and challenges. Natural Resources Forum 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Sun, T.; Xu, Q.; Cao, X. Impact and Implications of Forestry Carbon Sink Policies on Increasing Forest Carbon. Forestry Economics Issues 2022, 42, 659–665. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. The Structural Logic and Evolution of the Urban-Rural Development Gap and the Alienation of Environmental Interest Distribution in China. Research of Agricultural Modernization 2013, 34, 564–568. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Teng, F.; Lü, D.; Chai, H. Research on the Economic Development Path of Forestry Carbon Sink in Heilongjiang Province Based on PEST-SWOT Matrix. Sustainability 2019, 9, 9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, F. Research on the Evaluation Index System of Forest Carbon Sink Poverty Alleviation Performance Based on CDM Afforestation and Reforestation Projects. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University: Natural Sciences 2018, 42, 9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Shang, J. A Method for Subgroup Decomposition of Gini Coefficient Based on Relative Deprivation Theory. The Journal of Quantitative&Technical Economics 2011, 28, 103–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shi, H. The Economic Welfare Effect of Grain-for-Green Compensation from a Comparative Perspective—Based on an Empirical Study of79Grain-for-Green Counties in Shaanxi Province. Economic Geography 2017, 37, 146–155. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskin, M. J.; Eytan, S. Optimal Redistributive Taxation When Individual Welfare Depends Upon Relative Income. Quarterly Journal of Economics 1978, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M. A. Relative Income, Happiness and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles. Social Science Electronic Publishing.

- Dehejia, R. H.; Wahba, S. Propensity Score-Matching Methods for Nonexperimental Causal Studies. Review of Economics and Statistics 2002, 84, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Analysis of the Coordinated Development of Agricultural Ecology and Economic System in Southwest China. China Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning 2018, 39, 54–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. Research on the Construction of Forestry Carbon Sink Market in Heilongjiang Province. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, 2014. (In Chinese).

- Chen, Q. Advanced Econometrics and Stata Applications; Beijing: Higher Education Press: 2014; 2nd Edition, pp.542-559. (In Chinese).

| County | Project Type | Project Name | Year of Implementation | Poverty alleviation county | Ethnic county | Project cycle | Area/hm2 |

| Mianning | CCER | Audi Panda Habitat has multiple benefits | 2012 | 0 | 1 | 30 | 153.4 |

| Jinyang | CCER | Forest restoration and afforestation carbon sink project | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 181.7 |

| Lixian | CDM | Afforestation and reforestation project of degraded land in northwest Sichuan, China | 2004 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 747.8 |

| Maoxian | CDM | 2004 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 234.9 | |

| Beichuan | CDM | 2004 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 200.2 | |

| Qingchuan | CDM | 2004 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 190.6 | |

| Ganluo | CDM | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 924.3 | |

| Yuexi | CDM | Novartis Southwest Degraded Land Afforestation and Reforestation Project | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 1245.0 |

| Meigu | CDM | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 731.6 | |

| Zhaojue | CDM | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 441.8 | |

| Leibo | CDM | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 854.1 | |

| Yingjing | VCS | Reforestation project in Xingjing County, Sichuan Province | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 159.2 |

| Variable | Name | Definition | Variable Description | Mean | SE |

| Depenent variables |

W1 | Economic welfare without considering relative factors | Equation (11) θ1=θ2=θ3=0 | 9.010 | 0.640 |

| W2 | Economic welfare considering relative factors | Equation (11) θ1=θ2=θ3=1/3 | 8.550 | 0.840 | |

| H-H | Vertical comparison | V1, Equation (2) | 0.560 | 0.220 | |

| R-R | Horizontal inter-rural comparison | V2, Equation (3) | 0.030 | 0.330 | |

| U-R | Horizontal urban–rural comparison | V3, Equation (4) | 1.260 | 0.740 | |

| Core explanatory variable. |

DID | Whether a county is an FCSP pilot county | Yes=1, No=0 | 0.090 | 0.290 |

| Controls | Poverty | Whether a county is a poverty-alleviation county | Yes=1, No=0 | 0.240 | 0.430 |

| Ethnic | Whether a county is an ethnic county | Yes=1, No=0 | 0.360 | 0.480 | |

| Pgdp | Per capita GDP | Per capita GDP of each county (unit: CNY) | 29105.000 | 19965.000 | |

| Pie | Share of primary industry employment in total employment | Ratio of primary industry employment to total employment | 0.520 | 0.180 | |

| Tpam | Total power of agricultural machinery | Total power of machinery used in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery (unit: 10,000 kW) | 22.450 | 17.970 | |

| Rcl | Ratio of cultivated land area to total administrative land area | Cultivated land area at year-end (hectares) divided by total administrative land area (hectares) | 0.210 | 0.390 | |

| Fercon | Fertilizer consumption | Annual fertilizer consumption (unit: tonnes) | 13398.000 | 12318.000 | |

| Gcl | Grain yield per unit of cultivated land | Total grain output (tonnes) divided by cultivated land area at year-end (hectares), unit: tonnes/hectare | 1.660 | 0.620 | |

| Rma | Road mileage per unit of administrative area | Road mileage (km) divided by total administrative area (hectares), unit: km/hectare | 1.030 | 0.710 |

| Variable | Matched & Unmatched | Mean | Bias(%) | Reduct(%) | T-test | ||

| Treated | Control | |bias| | t | p>|t| | |||

| Poverty | U | 0.425 | 0.221 | 44.500 | 6.190 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.425 | 0.346 | 17.100 | 61.600 | 1.520 | 0.129 | |

| Ethnic | U | 0.665 | 0.333 | 70.200 | 9.030 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.665 | 0.696 | -6.500 | 90.700 | -0.620 | 0.534 | |

| Pgdp | U | 23995.000 | 29552.000 | -30.200 | -3.580 | 0.000 | |

| M | 23995.000 | 25914.000 | -10.400 | 65.500 | -0.950 | 0.344 | |

| Pie | U | 0.623 | 0.511 | 69.400 | 8.300 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.623 | 0.614 | 5.400 | 92.300 | 0.520 | 0.605 | |

| Tpam | U | 9.884 | 23.546 | -101.400 | -9.960 | 0.000 | |

| M | 9.884 | 9.016 | 6.400 | 93.600 | 1.400 | 0.162 | |

| Rcl | U | 0.069 | 0.111 | -28.500 | -2.750 | 0.006 | |

| M | 0.069 | 0.058 | 8.100 | 71.400 | 0.490 | 0.622 | |

| Fercon | U | 7274.200 | 13934.000 | -70.800 | -7.010 | 0.000 | |

| M | 7274.200 | 6955.300 | 3.400 | 95.200 | 0.500 | 0.616 | |

| Gcl | U | 1.451 | 1.682 | -46.300 | -4.830 | 0.000 | |

| M | 1.451 | 1.325 | 25.200 | 45.500 | 2.390 | 0.018 | |

| Rma | U | 0.684 | 1.062 | -64.300 | -6.900 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.684 | 0.624 | 10.200 | 84.200 | 1.260 | 0.209 | |

| year | Mean_Income | U_R | R_R | H_H |

| 2007 | 2633.692 | 0.669 | 0.251 | 1.000 |

| 2008 | 2970.923 | 0.687 | 0.281 | 1.098 |

| 2009 | 3214.923 | 0.712 | 0.263 | 0.937 |

| 2010 | 3789.692 | 0.700 | 0.265 | 1.119 |

| 2011 | 4567.600 | 0.672 | 0.273 | 0.840 |

| 2012 | 5319.892 | 0.668 | 0.270 | 0.967 |

| 2013 | 6109.610 | 0.650 | 0.263 | 0.968 |

| 2014 | 6938.622 | 0.629 | 0.272 | 0.914 |

| 2015 | 8358.538 | 0.569 | 0.256 | 0.862 |

| 2016 | 9218.692 | 0.560 | 0.252 | 0.878 |

| 2017 | 10168.230 | 0.551 | 0.248 | 0.936 |

| 2018 | 11227.300 | 0.543 | 0.242 | 0.889 |

| 2019 | 9968.923 | 0.363 | 0.273 | 0.799 |

| 2020 | 10889.462 | 0.349 | 0.286 | 0.800 |

| 2021 | 11866.154 | 0.351 | 0.301 | 0.840 |

| 2022 | 12904.538 | 0.367 | 0.318 | 0.804 |

| year | W1 | W2 | u |

| 2007 | 7.854 | 7.355 | 0.068 |

| 2008 | 7.958 | 7.493 | 0.062 |

| 2009 | 8.054 | 7.543 | 0.068 |

| 2010 | 8.220 | 7.769 | 0.058 |

| 2011 | 8.403 | 7.859 | 0.069 |

| 2012 | 8.555 | 8.055 | 0.062 |

| 2013 | 8.694 | 8.153 | 0.066 |

| 2014 | 8.823 | 8.147 | 0.083 |

| 2015 | 9.009 | 8.176 | 0.102 |

| 2016 | 9.108 | 8.265 | 0.102 |

| 2017 | 9.207 | 8.381 | 0.099 |

| 2018 | 9.308 | 8.464 | 0.100 |

| 2019 | 9.149 | 8.090 | 0.131 |

| 2020 | 9.227 | 8.155 | 0.131 |

| 2021 | 9.302 | 8.342 | 0.115 |

| 2022 | 9.374 | 8.280 | 0.132 |

| Average | 8.7653 | 8.0329 | 0.0905 |

| W1 | W2 | |

| DID | 0.111*** | -0.119** |

| (0.039) | (0.050) | |

| Poverty | -0.043 | -0.322*** |

| (0.036) | (0.046) | |

| Ethnic | 0.117** | 0.249*** |

| (0.047) | (0.059) | |

| Pgdp | 0.013*** | 0.012*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Pie | 0.228* | 0.433*** |

| (0.123) | (0.157) | |

| Tpam | 0.016*** | 0.021*** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Rcl | 0.506** | 1.687*** |

| (0.237) | (0.302) | |

| Fercon | -0.138 | -0.462 |

| (0.152) | (0.173) | |

| Gcl | -0.155*** | -0.072* |

| (0.033) | (0.042) | |

| Rma | 0.151*** | 0.172*** |

| (0.024) | (0.031) | |

| _cons | 8.031*** | 7.141*** |

| (0.105) | (0.134) | |

| Fix_id | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y |

| N | 1179 | 1179 |

| R2 | 0.474 | 0.418 |

| U-R | R-R | H-H | |

| DID | -0.094*** | 0.129*** | -0.211*** |

| (0.018) | (0.020) | (0.048) | |

| _cons | 0.800*** | 0.379*** | 0.772*** |

| (0.047) | (0.052) | (0.128) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 1179 | 1179 | 1179 |

| R-sq | 0.165 | 0.391 | 0.175 |

| W1 | W2 | |

| d1 | -0.219 | -0.090 |

| (0.169) | (0.213) | |

| d2 | -0.129 | 0.006 |

| (0.169) | (0.213) | |

| d3 | -0.036 | -0.109 |

| (0.169) | (0.213) | |

| d4 | -0.116 | -0.259 |

| (0.133) | (0.167) | |

| d5 | -0.058 | -0.255 |

| (0.132) | (0.167) | |

| d6 | 0.032 | -0.196 |

| (0.132) | (0.166) | |

| d7 | 0.188 | -0.456*** |

| (0.132) | (0.165) | |

| d8 | 0.256* | -0.397** |

| (0.132) | (0.166) | |

| d9 | 0.241* | -0.389** |

| (0.132) | (0.165) | |

| d10 | 0.249* | -0.654*** |

| (0.132) | (0.165) | |

| d11 | 0.288** | -0.582*** |

| (0.132) | (0.165) | |

| d12 | 0.375*** | -0.642*** |

| (0.143) | (0.179) | |

| d13 | 0.353** | -0.065 |

| (0.150) | (0.189) | |

| _cons | 7.957*** | 6.922*** |

| (0.106) | (0.135) | |

| Control | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y |

| N | 1179 | 1179 |

| R2 | 0.484 | 0.446 |

| 20-years | 30-years | |||

| W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | |

| DID | 0.064 | -0.140* | 0.127** | -0.117* |

| (0.061) | (0.077) | (0.054) | (0.070) | |

| _cons | 7.933*** | 7.015*** | 7.890*** | 6.966*** |

| (0.117) | (0.149) | (0.111) | (0.143) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1099 | 1099 |

| R2 | 0.467 | 0.426 | 0.495 | 0.436 |

| 20-years | 30-years | |||||

| U-R | R-R | H-H | U-R | R-R | H-H | |

| DID | -0.001 | 0.127*** | -0.123 | -0.174*** | 0.138*** | -0.290*** |

| (0.027) | (0.030) | (0.075) | (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.068) | |

| _cons | 0.740*** | 0.412*** | 0.687*** | 0.736*** | 0.435*** | 0.653*** |

| (0.052) | (0.059) | (0.145) | (0.049) | (0.057) | (0.140) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1099 | 1099 | 1099 |

| R2 | 0.157 | 0.358 | 0.154 | 0.190 | 0.402 | 0.186 |

| General County | Poverty alleviation counties | |||

| W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | |

| DID | 0.067 | -0.197*** | 0.026 | -0.047 |

| (0.054) | (0.070) | (0.055) | (0.069) | |

| _cons | 7.961*** | 6.912*** | 8.104*** | 7.674*** |

| (0.133) | (0.173) | (0.165) | (0.207) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 831 | 831 | 348 | 348 |

| R-sq | 0.471 | 0.418 | 0.627 | 0.437 |

| General County | Poverty alleviation counties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-R | R-R | H-R | U-R | R-R | H-R | |

| DID | -0.030 | 0.132*** | -0.142** | -0.121*** | 0.117*** | -0.277*** |

| (0.023) | (0.028) | (0.067) | (0.030) | (0.023) | (0.075) | |

| _cons | 0.687*** | 0.422*** | 0.654*** | 0.970*** | 0.319*** | 0.759*** |

| (0.058) | (0.069) | (0.166) | (0.091) | (0.068) | (0.223) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_id | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fix_year | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 831 | 831 | 831 | 348 | 348 | 348 |

| R-sq | 0.164 | 0.355 | 0.162 | 0.335 | 0.316 | 0.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).