Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Age and Anthropometric Parameters

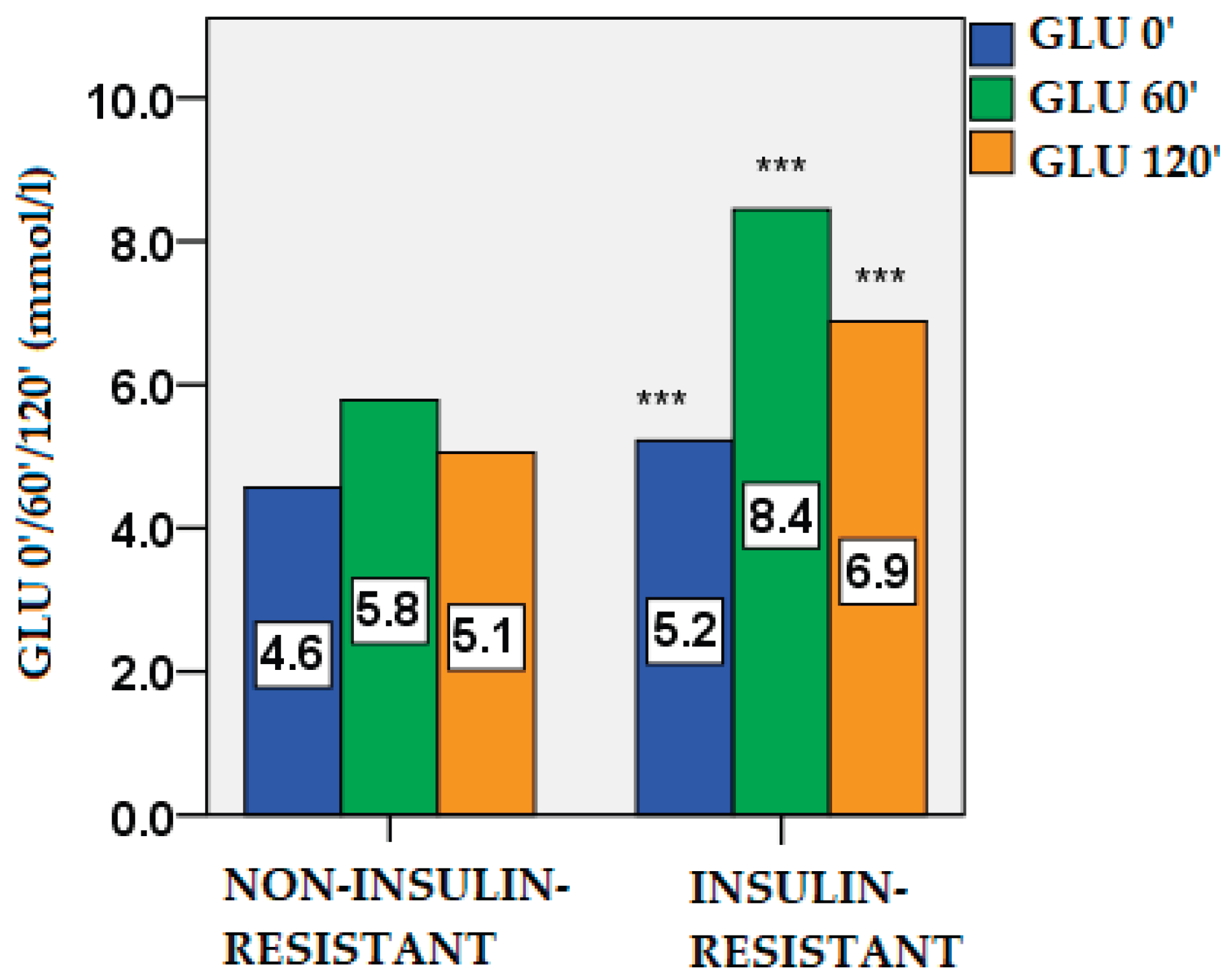

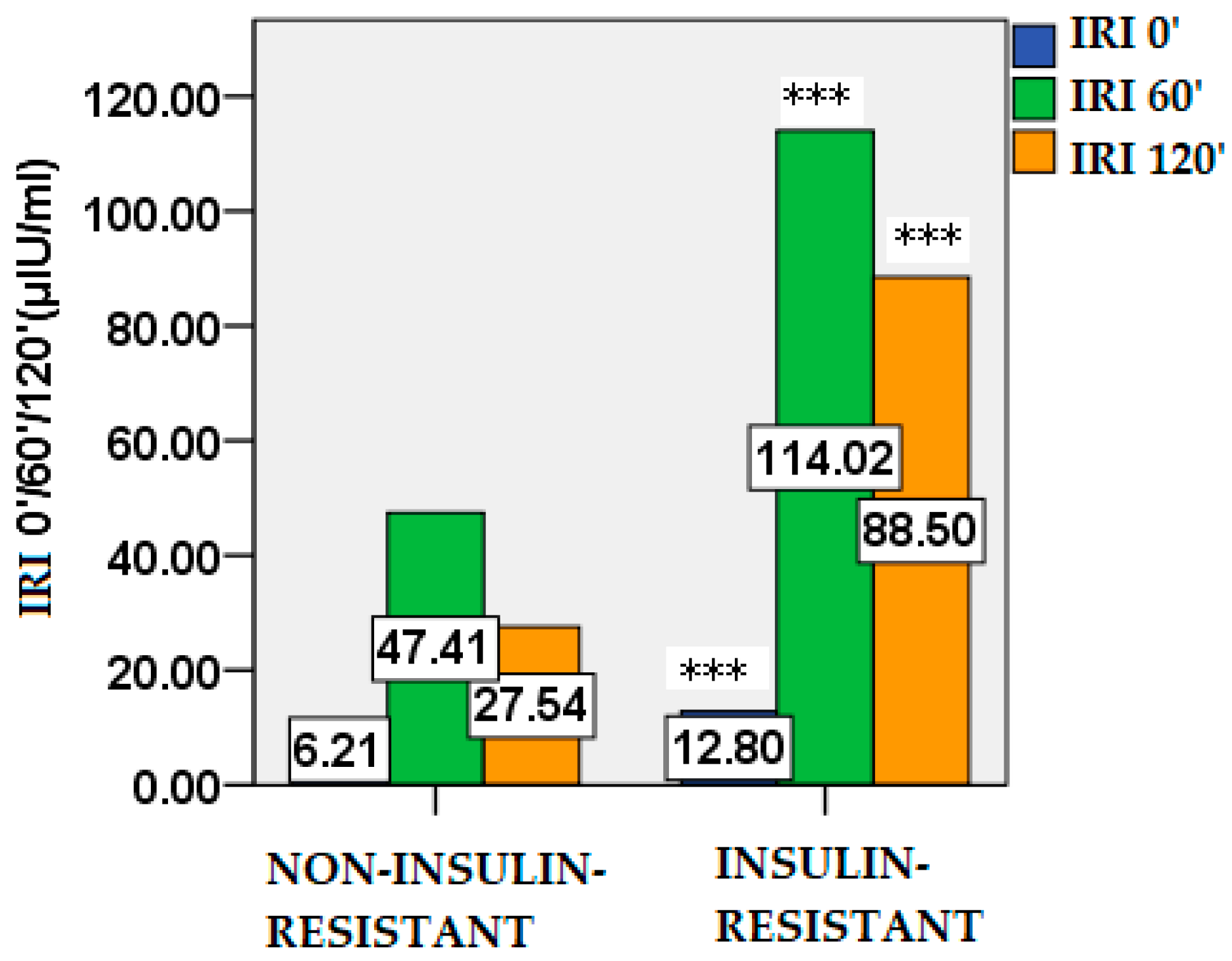

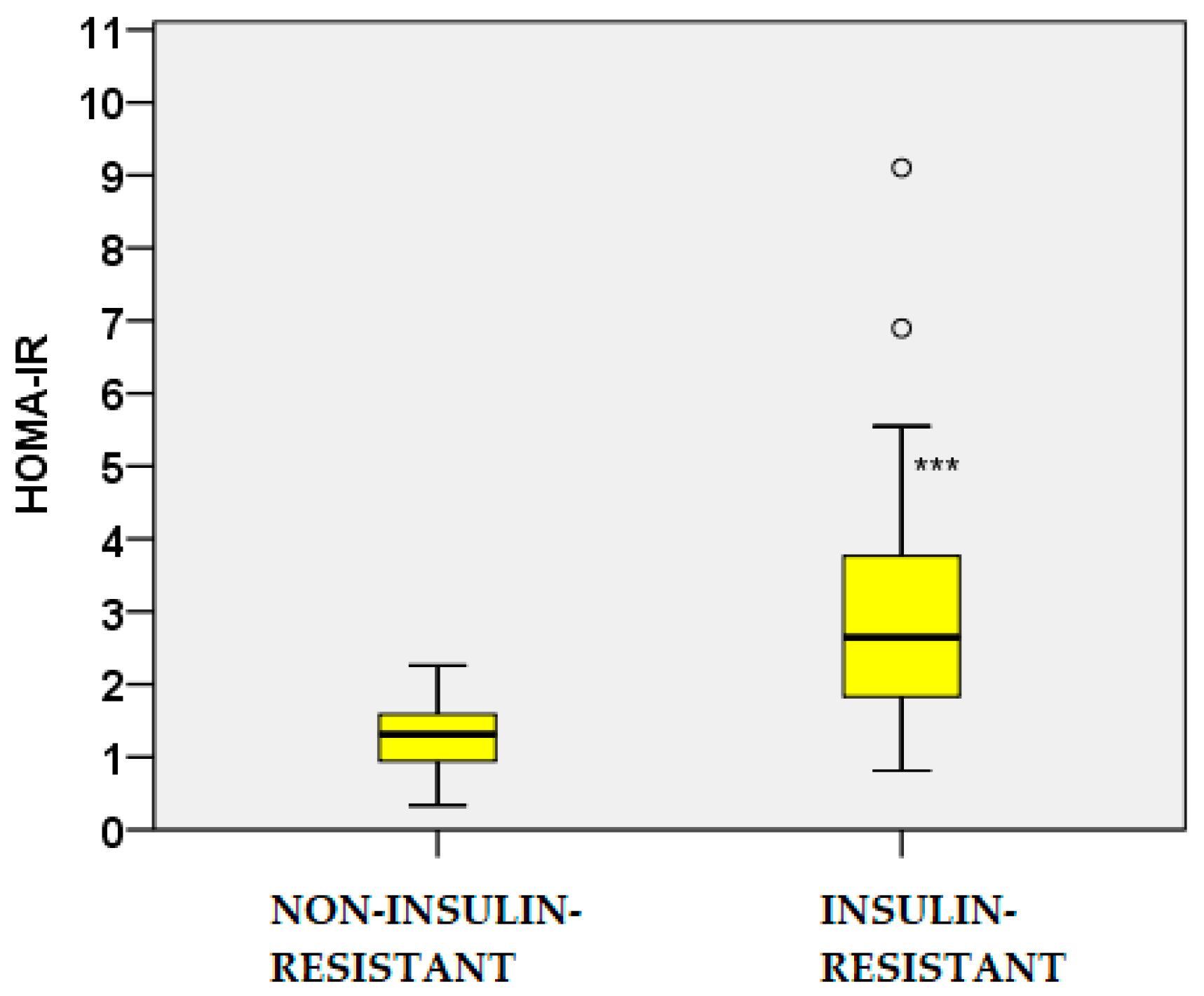

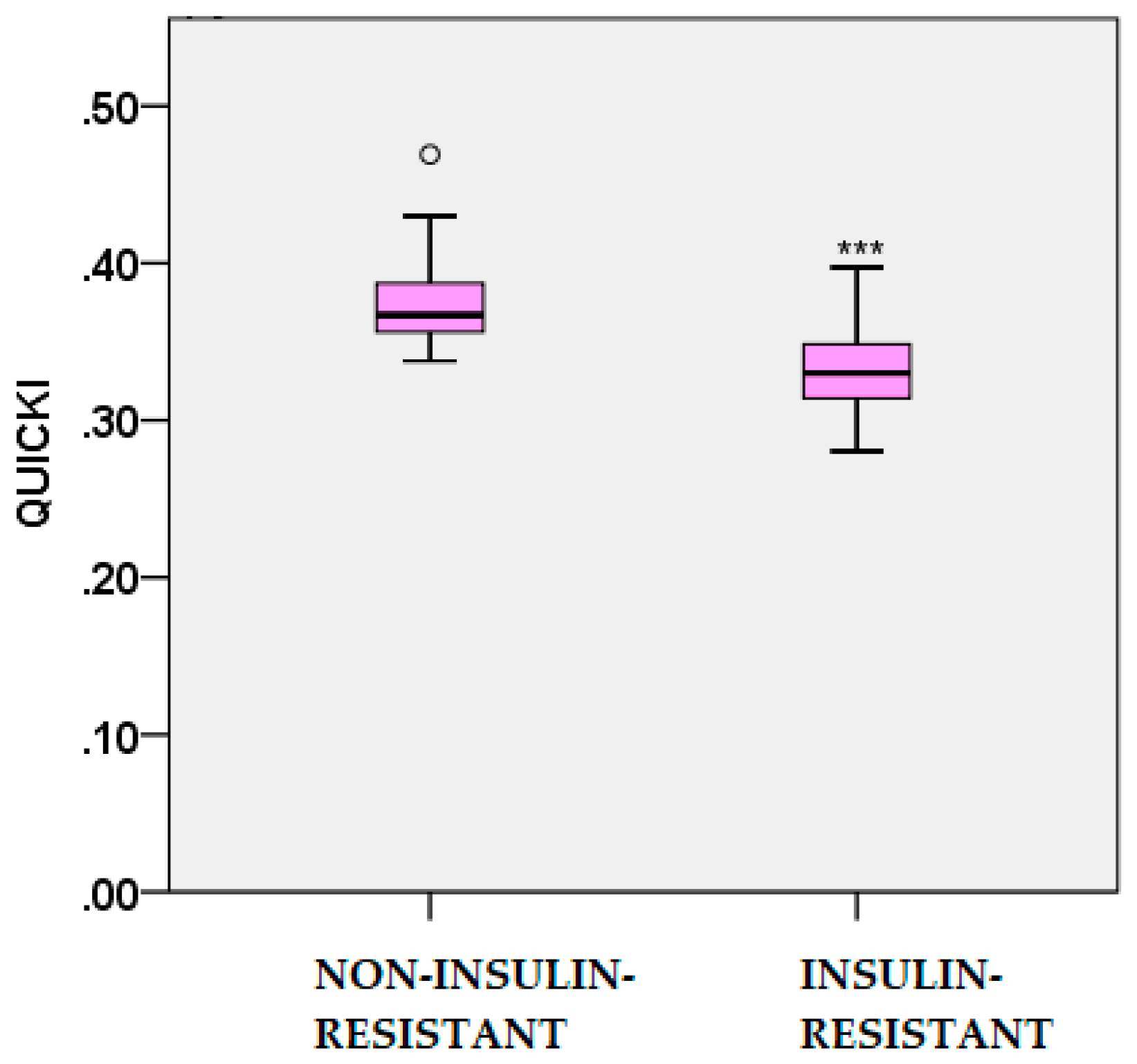

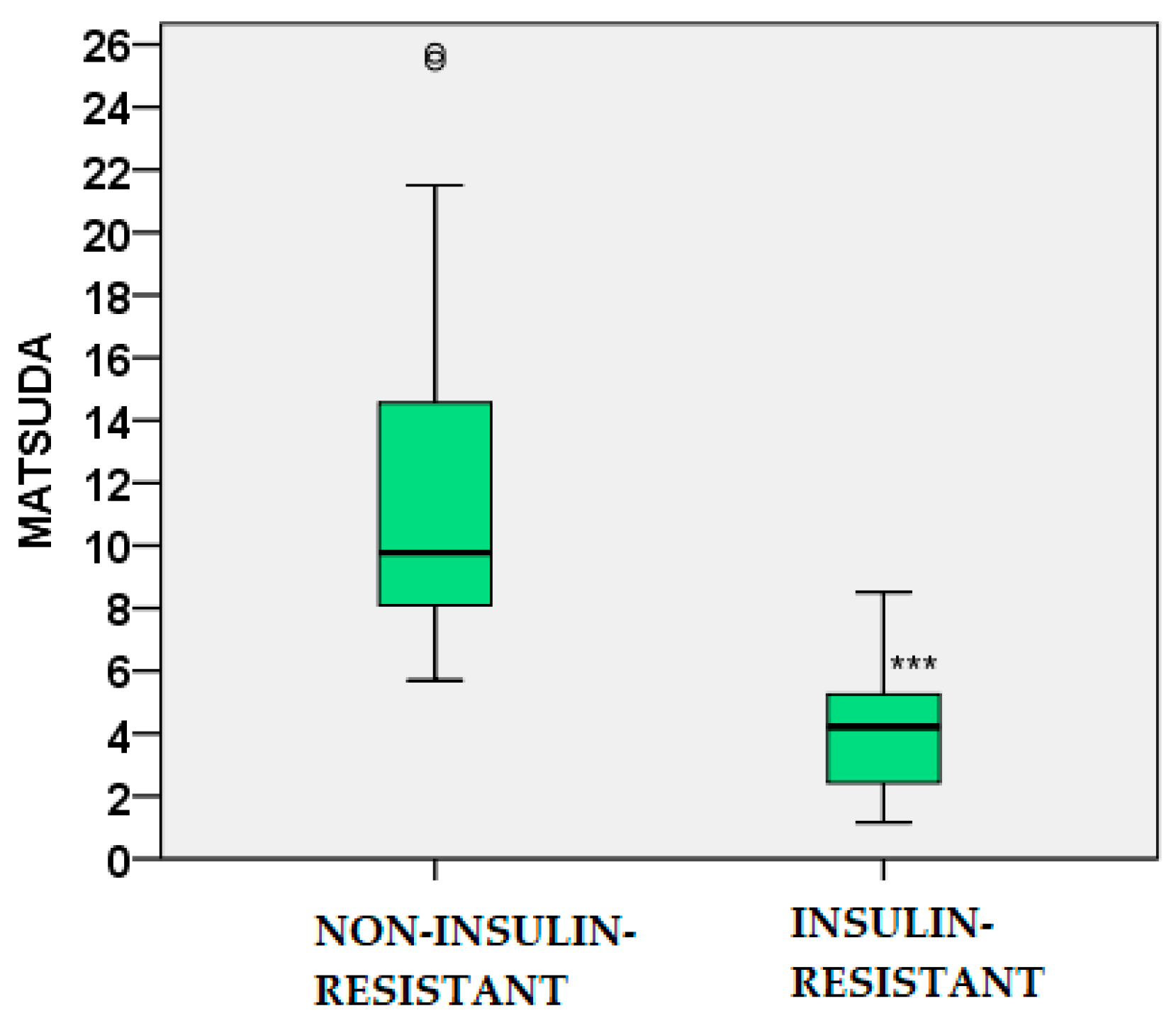

2.2. Glucose and Insulin Dynamics

2.3. Lipid Profile and Atherogenic Indices

2.4. Adipokine Profiles

2.5. Correlation Analyses

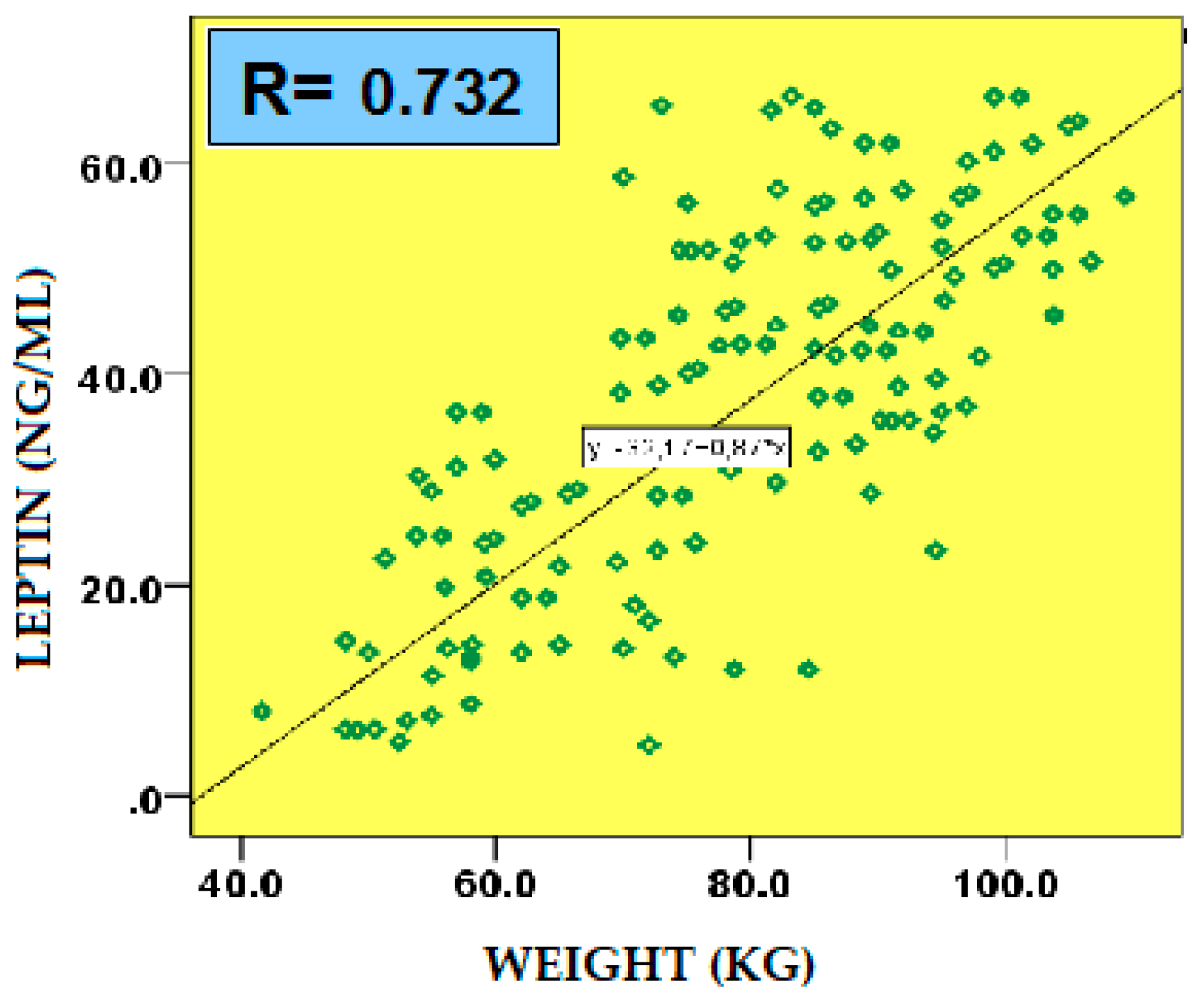

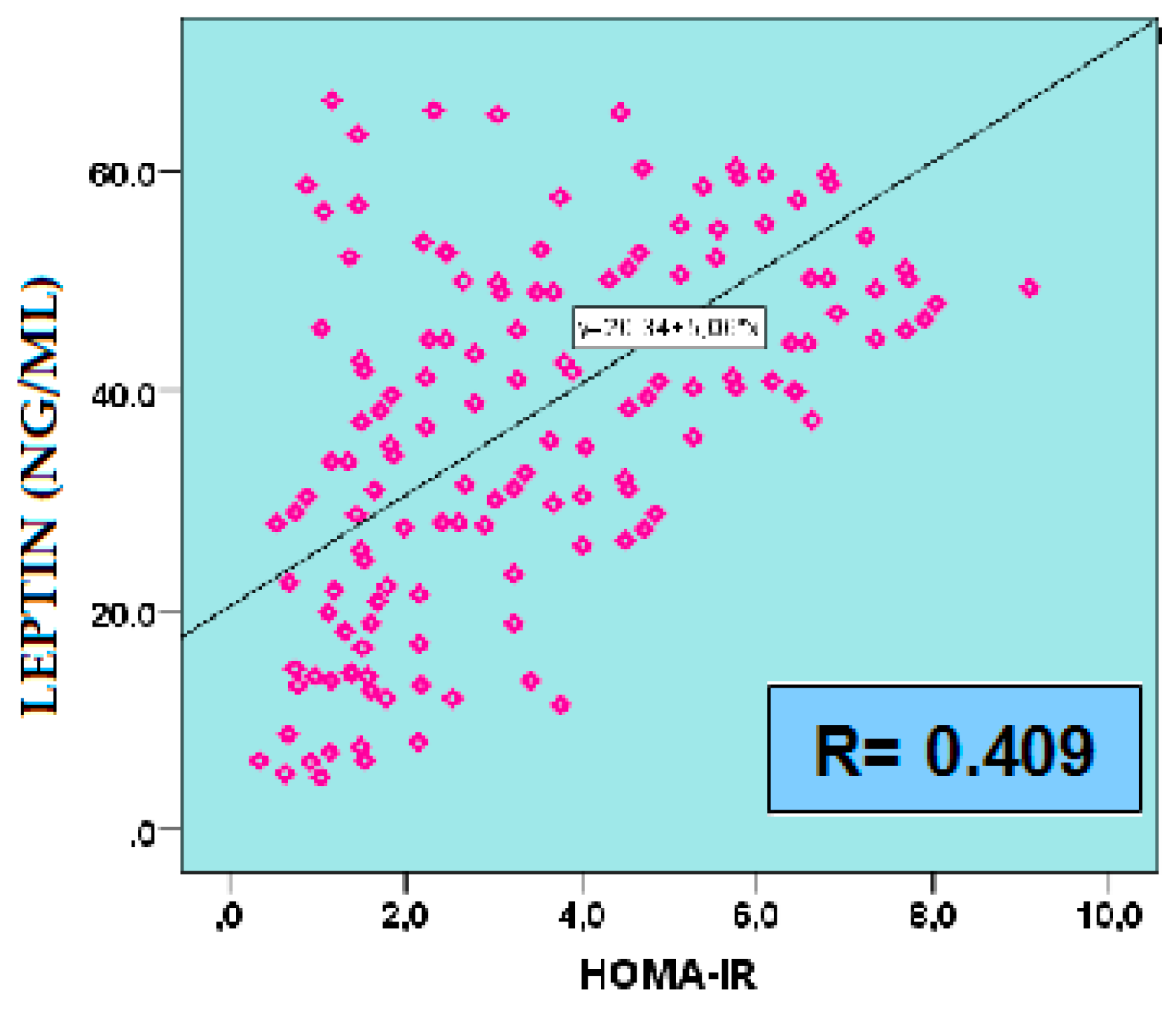

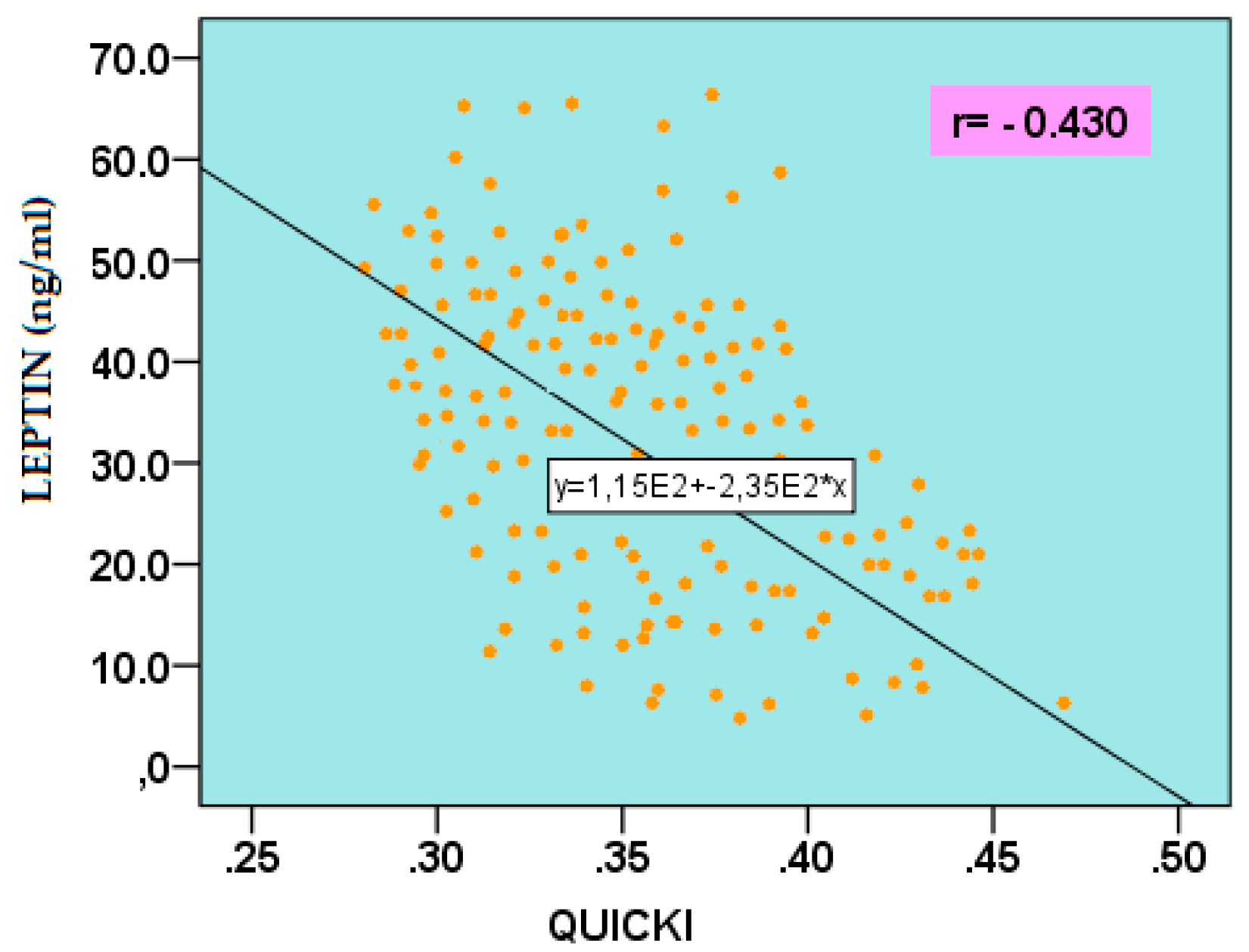

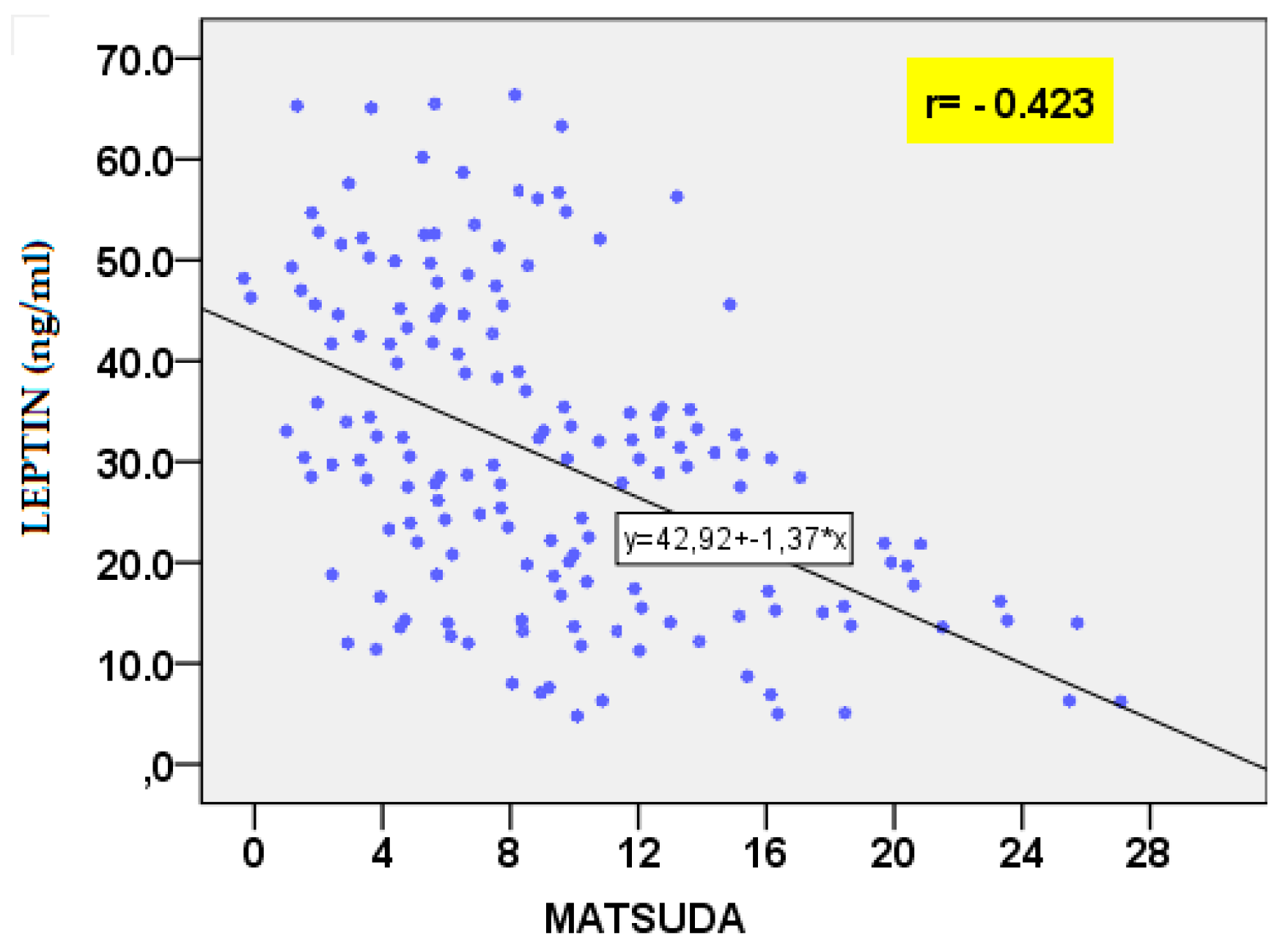

2.5.1. Leptin

2.5.2. Adiponectin

2.5.3. Visfatin

2.5.4. Resistin

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Population

4.2. Anthropometric and Clinical Measurements

4.3. Biochemical, Hormonal and Adipokine Assessment

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| IR | Insulin Resistance |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance |

| QUICKI | Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index |

| AIP | Atherogenic Index of Plasma |

| HDL-C | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

References

- Lizneva, D.; Suturina, L.; Walker, W.; Brak, S.; Gavrilova-Jordan, L.; Azziz, R. Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumesic, D.A.; Oberfield, S.E.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Marshall, J.C.; Laven, J.S.; Legro, R.S. Scientific statement on the diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and molecular genetics of PCOS. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 487–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Chen, Z.; Dunaif, A.; Laven, J.S.; Legro, R.S.; Lizneva, D.; Natterson-Horowitz, B.; Teede, H.J.; Yildiz, B.O. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F. Inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids 2012, 77, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 981–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, J.E. Insulin regulation of human ovarian androgens. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasshauer, M.; Blüher, M. Adipokines in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Karges, B.; Meissner, T.; Wiegand, S.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Holl, R.W.; Woelfle, J. Inflammatory markers in obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes and their relationship to hepatokines and adipokines. J. Pediatr. 2016, 173, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Al-Rubeaan, K.; Mohieldin, M.; Al-Katari, M. , Jones, A.F., Kumar, S. Serum leptin and its relation to anthropometric measures of obesity in pre-diabetic Saudis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboudi-Gandevani, S.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Yarandi, R.B.; Noroozzadeh, M.; Hedayati, M.; Azizi,, F. The association between polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity, and the serum concentration of adipokines. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017, 40, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panidis, D.; Kourtis, A.; Farmakiotis, D.; Mouslech, T.; Rousso, D.; Koliakos, G. Serum adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003, 18, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Chang, D.M.; Lin, K.C.; Shin, S.J.; Lee, Y.J. Visfatin in overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis and systemic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011, 27, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Franks, S. Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 95, 529–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, R.A.; Rizzo, M.; Clifton, S.; Carmina, E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility 2011, 3, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, S.; Haffner, S.; Davidson, M.H.; D’Agostino, R., Jr.; Feinstein, S.; Kondos, G.; Perez, A. Relation of abdominal fat depots to systemic markers of inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobiasova, M. Atherogenic index of plasma [log(TG/HDL-C)]: theoretical and practical implications. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; He, Z.; Li, O.; Lv, M.; Cai, Y.; Ke, W.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Z. Adipokines in atherosclerosis: unraveling complex roles. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, R.V.; Sinha, M.K.; Heiman, M.L.; Kriauciunas, A.; Stephens, T.W.; Nyce, M.R.; Ohannesian, J.P.; Marco, C.C.; McKee, L.J.; Bauer, T.L.; et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orio, F.; Giallauria, F.; Palomba, S.; Cascella, T.; Manguso, F.; Vuolo, L.; Russo, T.; Labella, D.; Savastano, S.; Lombardi, G.; Colao, A. Leptin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2619–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.G.; Cowley, M.A.; Münzberg, H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008, 70, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panidis, D.K.; Rousso, D.H; Matalliotakis, I.M; Kourtis, A.I.; Stamatopoulos, P.; Koumantakis, E. The influence of long-term administration of conjugated estrogens and antiandrogens to serum leptin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2000, 14, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangasa, M.A; Buck, C.; Kelm, S.; Sheikh, M.A.; Günther, K.; Hebestreit, A. The association between leptin and inflammatory markers with obesity indices in Zanzibari children, adolescents, and adults. Obes Sci Pract. 2020, 7, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, J. Serum leptin level in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: correlation with adiposity, insulin, and circulating testosterone. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013, 3, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, B.N.; Dabaghmanesh, M.H.; Parsanezhad, M.E.; Fatehpoor, F. Association of leptin and insulin resistance in PCOS: A case-controlled study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2017, 15(7), 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Daghestani, M.H.; Daghestani, M.; Daghistani, M.; El-Mazny, A.; Bjørklund, G.; Chirumbolo, S.; Al Saggaf, S.H.; Warsy, A. A study of ghrelin and leptin levels and their relationship to metabolic profiles in obese and lean Saudi women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohana, C.A.; Hasanat, M.A; Rashid, E.U.; Jahan, I.A.; Morshed, M.Sh.; Banu, H; Jahan, Sh. Leptin and Leptin Adiponectin Ratio may be Promising Markers for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Cardiovascular Risks. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2021, 47, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.K.; Lee, H.; Sung, Y.-A.; Oh, J.-Y. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio can predict impaired glucose tolerance in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Yonsei Med J 2016, 57, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, H.; Menekse, B.; Ucgul, E.; Onaran, Y.; Bayram, S.M.; Cakal, E. Impact of polycystic ovary syndrome on the atherogenic plasma index: A retrospective analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2025, 25, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Аgarwal, S.K.; Vogel, K.; Weitsman, S.R.; Magoffin, D.A. Leptin antagonizes the insulin-like growth factor-I augmentation of steroidogenesis in granulosa and theca cells of the human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999, 84, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschos, S.; Chan, J.L.; Mantzoros Ch., S. Leptin and reproduction: a review. Fertility and Sterility 2002, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulis, K.A.; Goulis, D.G.; Farmakiotis, D.; Georgopoulos, N.A.; Katsikis, I.; Tarlatzis, B.C. , Papadimas, I.; Panidis, D. et al. Adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update. (Oxf.). 2009, 3, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, S.; Que, S.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S.; Mardinoglu, A. Meta-Analysis of Adiponectin as a Biomarker for the Detection of Metabolic Syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Choi, K.M. Adipokines as a Novel Link Between Obesity and Atherosclerosis. World J. Diabetes. 2014, 5, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanes, Y.M.; Reeves, S. Metabolic Consequences of Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Diagnostic and Methodological Challenges. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obirikorang, C.; Owiredu, W.K.B.A.; Adu-Afram, S.; Acheampong, E.; Asamoah, E.A.; Antwi-Boasiakoh, E.K.; Owiredu, E-W. Assessing the Variability and Predictability of Adipokines (Adiponectin, Leptin, Resistin and Their Ratios) in Non-Obese and Obese Women with Anovulatory Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lin, M.; Tian, X.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Deng, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Serum Adiponectin Level Is Negatively Related to Insulin Resistance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr. Connect. 2025, 14, e240401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Veerabhadra Goud, G.K.; Shivashankar, R.N.; Anusuya, S.K.; Ganesh, V. Association of adiponectin levels with polycystic ovary syndrome among Indian women. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2022, 72, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, F.K.H.; Khodamoradi, Z.; Jeddi, M. Insulin resistance and high molecular weight adiponectin in obese and non-obese patients with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). BMC Endocr Disord. 2021, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Frias-Toral, E.; Verde, L.; Ceriani, F.; Cucalón, G.; Garcia-Velasquez, E.; Moretti, D.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; Muscogiuri, G. PCOS and nutritional approaches: Differences between lean and obese phenotype. Metabolism Open. 2021, 12, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, I.; Ciećwież, S.; Łój, B.; Brodowski, J.; Brodowska, A. Adiponectin gene polymorphism (rs17300539) has no influence on the occurrence of metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Genes. 2021, 12, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Qiao, J.; Guan, Y.; Kang, J. Adipokines in Reproductive Function: A Link between Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 50, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosatti, J.A.G.; Alves, M.T.; Cândido, A.L.; Reis, F.M.; Araújo, V.E.; Gomes, K.B. Influence of n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, I.; Straczkowski, M.; Nikolajuk, A.; Adamska, A.; Karczewska-Kupczewska, M.; Otziomek, E.; Wolczynski, S.; Gorska, M. Serum visfatin in relation to insulin resistance and markers of hyperandrogenism in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2007, 22, 1824–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzyńska, K.; Skrzyński, M.; Kwiatkowska, M.; Kwiatkowska, E.; Zawisza, K.; Skrzyński, J.; Skrzyński, J. Visfatin and VEGF levels are not increased in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2024, 37, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wei, L.; Liu, C.; Zhu, S.; Tang, S. High-visfatin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence from a meta-analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015, 31: 808–814. [CrossRef]

- El-Said, M.H.; El-Said, N.H.; El-Ghaffar, M.N.A. Plasma Visfatin Concentrations in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Relationships with Indices of Insulin Resistance and Hyperandrogenism. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2009, 77, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gen, R.; Akbay, E.; Muslu, N.; Sezer, K.; Cayan, F. Plasma Visfatin Level in Lean Women with PCOS: Relation to Proinflammatory Markers and Insulin Resistance. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2009, 25, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estienne, A.; Bongrani, A.; Reverchon, M.; Ramé, C.; Ducluzeau, P.-H.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Involvement of Novel Adipokines, Chemerin, Visfatin, Resistin and Apelin in Reproductive Functions in Normal and Pathological Conditions in Humans and Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bril, F.; Ezeh, U.; Amiri, M.; Hatoum, S.; Pace, L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Bertrand, F.; Gower, B.; Azziz, R. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, K.C.; Szosland, K.; O'Callaghan, C.; Tan, B.K.; Randeva, H.S.; Lewinski, A. Adiponectin and resistin serum levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome during oral glucose tolerance test: a significant reciprocal correlation between adiponectin and resistin independent of insulin resistance indices. Mol Genet Metab. 2005, 85, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Bukan, N.; Demirci, H.; Oztürk, C.; Kan, E.; Ayvaz, G.; Arslan, M. Serum resistin and adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2009, 25, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benomar, Y.; Gertler, A.; De Lacy, P.; Crépin, D.; Ould Hamouda, H.; Riffault, L.; Taouis, M. Central Resistin Overexposure Induces Insulin Resistance Through Toll-Like Receptor 4. Diabetes 2012, 62, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Xing, J.; Zhang, N.; Xu, L. Systematic Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation and Intrinsic Mechanisms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1470283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, S.; Mason, T.; Godini, R.; Vanky, E.; Teede, H.; Mousa, A. Metformin Use in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Opportunities, Benefits, and Clinical Challenges. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, Y.; He, B. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists versus Metformin in PCOS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 39, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Q.; Xing, C.; He, B. Short Period-Administration of Myo-Inositol and Metformin on Hormonal and Glycolipid Profiles in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 1792–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Maan, P.; Jyoti, A.; Kumar, A.; Malhotra, N.; Arora, T. The Role of Lifestyle Interventions in PCOS Management: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, S.; Lim, S.; Alycia, C.; Pirotta, S.; Thomson, R.; Gibson-Helm, M.; Blackmore, R.; Naderpoor, N.; Bennett, C.; Ee, C.; Rao,V. ; Mousa, A.; Alesi, S.; Moran, L. Lifestyle Management in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome—Beyond Diet and Physical Activity. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geloneze, B.; Vasques, A.C.; Stabe, C.F.; Pareja, J.C.; Rosado, L.E.; Queiroz, E.C.; Tambascia, M.A. HOMA1-IR and HOMA2-IR indexes in identifying insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome: Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study (BRAMS). Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009, 53, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Non-IR PCOS (n=74) |

IR PCOS (n=76) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.60 ± 4.53 | 24.03 ± 5.86 NS |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 1.66 ± 0.05 NS |

| Weight (kg) | 67.92 ± 15.94 | 78.08 ± 16.00 ** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.31 ± 5.28 | 28.40 ± 5.56 ** |

| Waist (cm) | 79.16 ± 13.45 | 89.21 ± 16.17 ** |

| Hip (cm) WHR |

99.49 ± 10.75 0.79 ± 0.08 |

107.82 ± 10.68 ** 0.82 ± 0.10 NS |

| Parameters | Non-IR PCOS (n=74) |

IR PCOS (n=76) |

|---|---|---|

| TC (mmol/l) | 4.48 ± 0.93 | 4.46 ± 0.86 NS |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.37 ± 0.49 | 1.23 ± 0.28 NS |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.78 ± 0.92 | 2.67 ± 0.84 NS |

| TG (mmol/l) | 0.80 ± 0.30 | 1.22 ± 0.60 *** |

| AIP LDL-C/HDL-C TG/HDL-C |

-0.09 ± 0.14 2.23 ± 0.92 0.67 ± 0.34 |

0.03 ± 0.19 *** 2.32 ± 0.92 NS 1.06 ± 0.60 ** |

| Adipokines | Non-IR PCOS (n=74) |

IR PCOS (n=76) |

|---|---|---|

| Visfatin (ng/ml) | 7.23 ± 3.76 | 14.05 ± 11.03 * |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 24.90 ± 18.37 | 39.56 ± 18.54** |

| Adiponectin (mcg/ml) | 14.70 ± 7.74 | 9.19 ± 4.53 ** |

| Log10 Resistin (ng/ml) | 0.67 ± 0.20 | 0.81 ± 0.23 * |

| Parameter | r | p |

| Weight | -0.385 | 0.001 |

| BMI | -0.361 | 0.003 |

| Waist | -0.411 | 0.001 |

| Hip | -0.341 | 0.005 |

| WHR | -0.317 | 0.009 |

| GLU 60’ IRI 0’ IRI 60’ IRI 120’ HOMA-IR MATSUDA QUICKI TG TG/HDL-C AIP |

-0.291 -0.332 -0.288 -0.259 -0.308 0.408 0.395 -0.409 -0.363 -0.422 |

0.025 0.006 0.027 0.047 0.012 0.001 0.001 0.01 0.003 <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).