Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

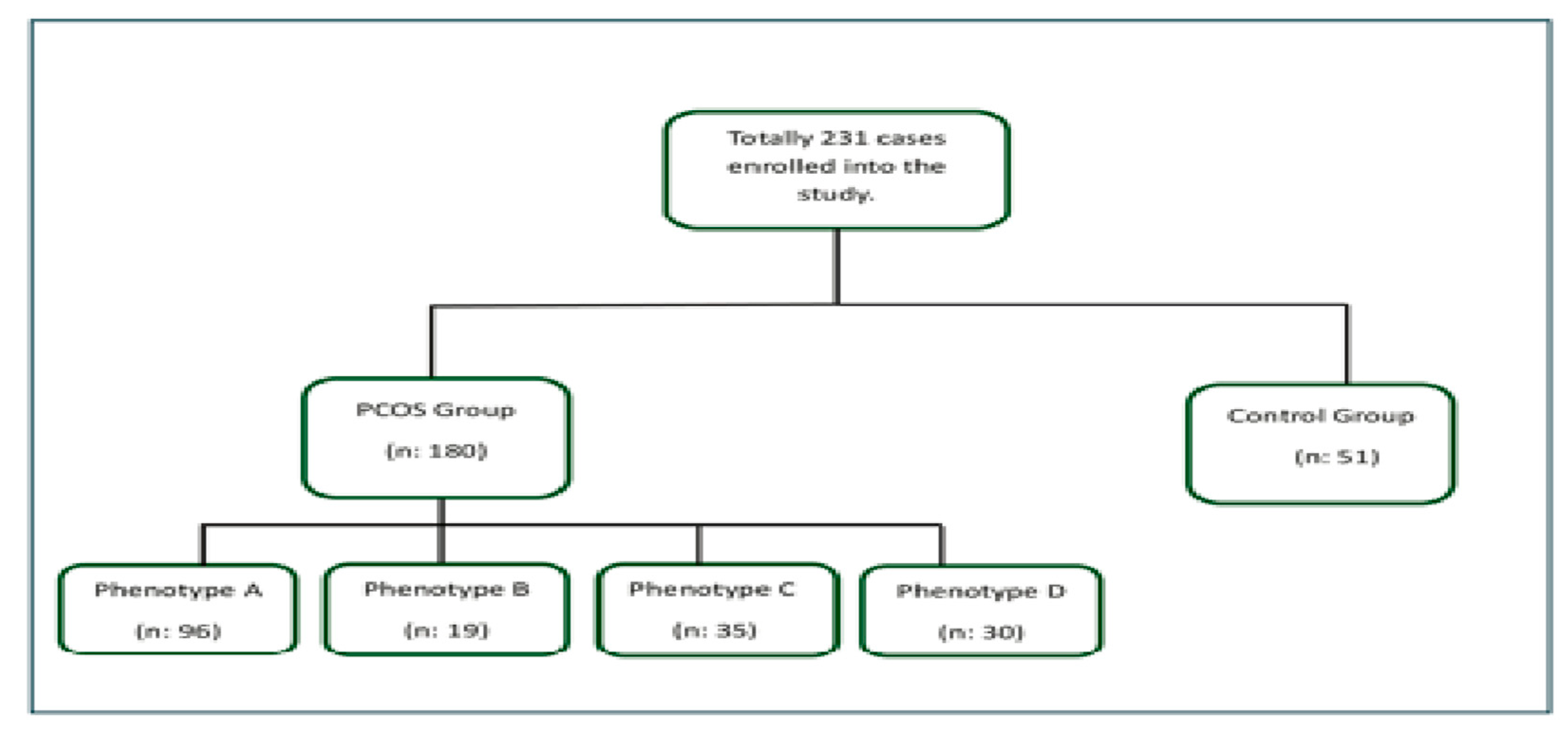

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

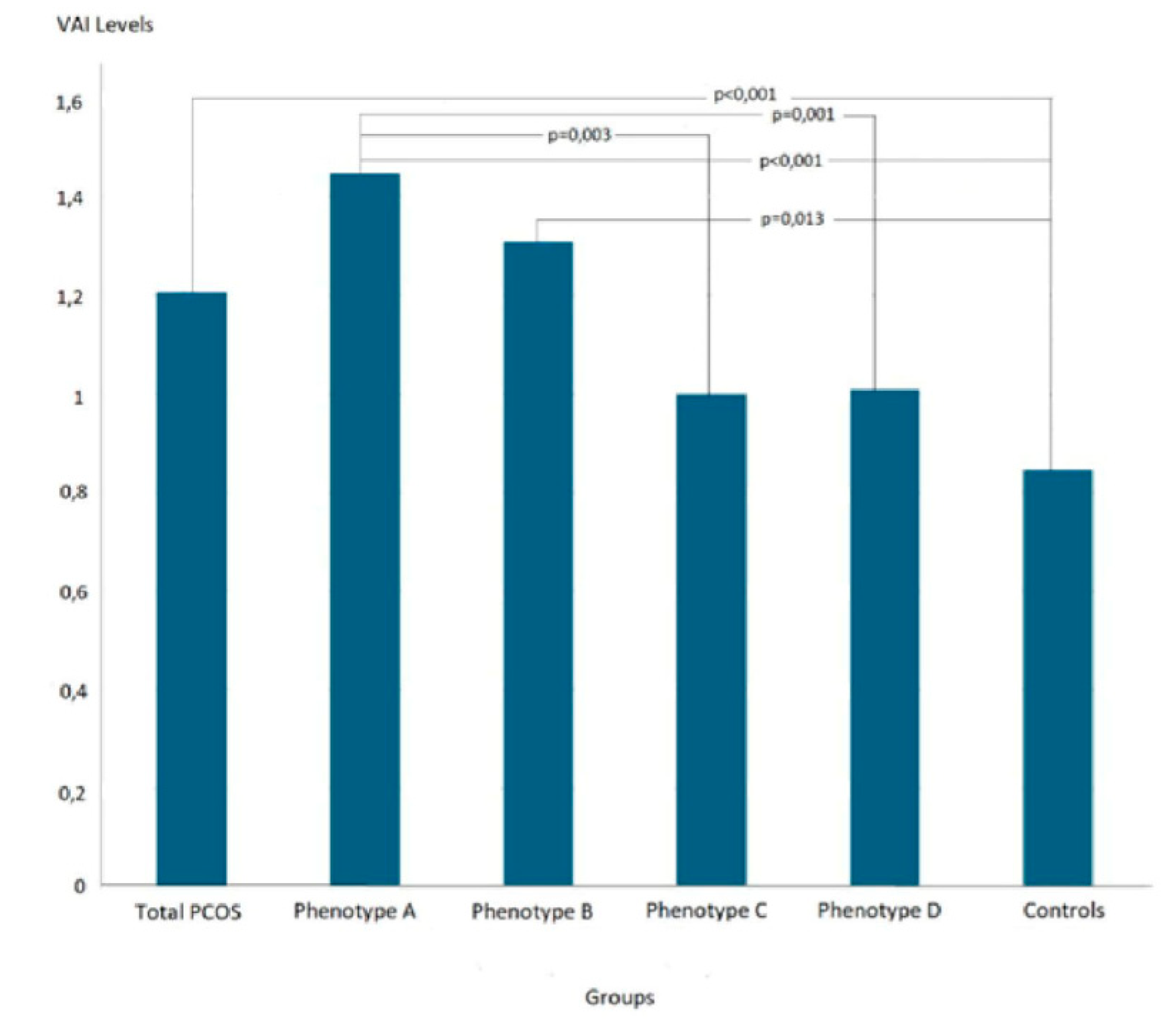

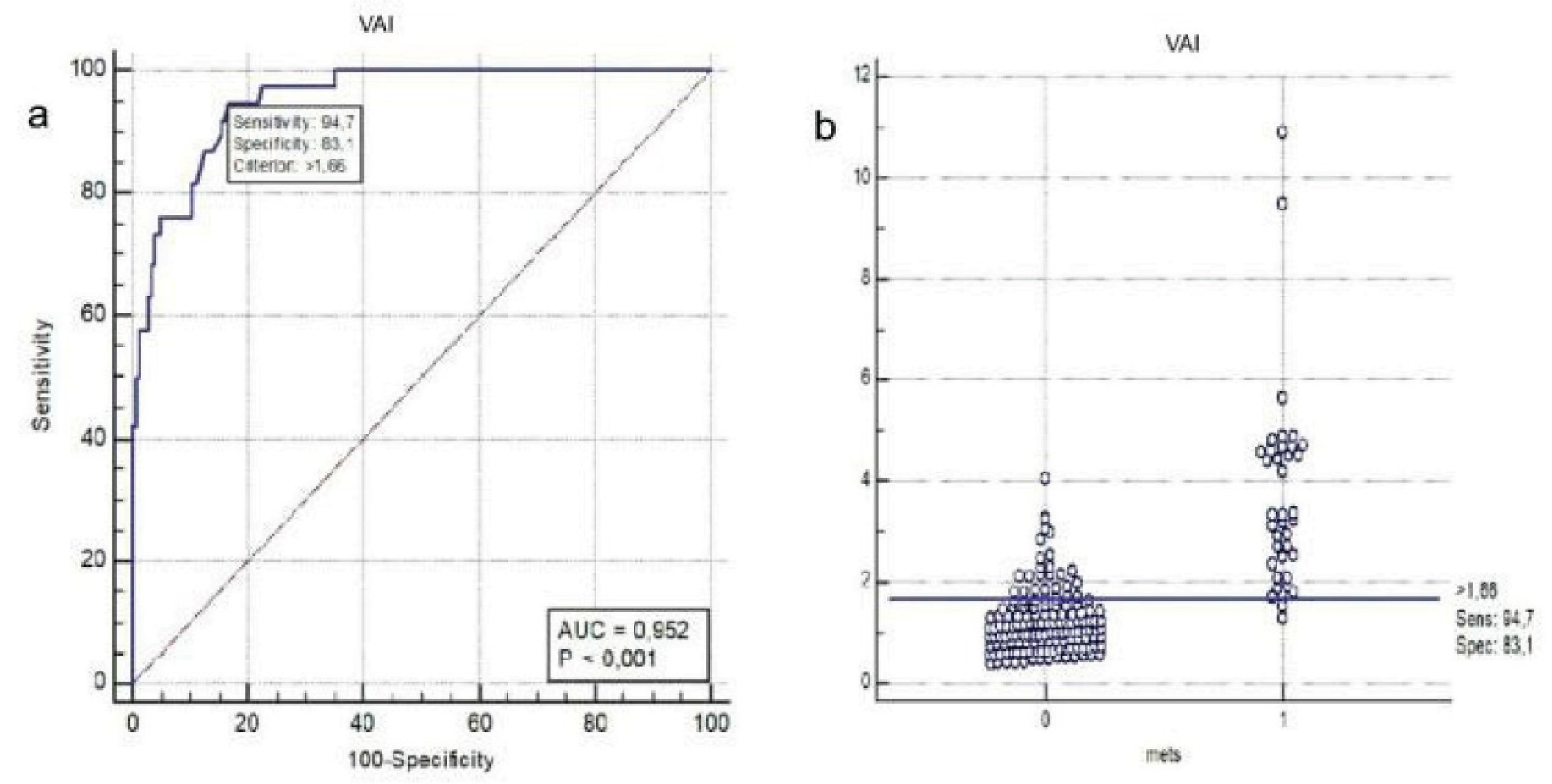

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VAI Visceral adiposity index PCOS Polycystic Ovary Syndrome HA Hyperandrogenism OA Oligo-anovulation PCOM Polycystic ovarian morphology BMI Body mass index HDL High density lipoprotein MetS Metabolic Syndrome ROC Receiver Operating Characteristic USG Ultrasonography PCO Polycystic ovaries HT Hypertension IR Insulin resistance DM Type 2 diabetes mellitus WC Waist circumference CT Computerized tomography DXA Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry NCEP-ATP National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel HOMA-IR Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance TG Triglyceride NR Normal range SD Standard deviation AUC Area under curve CI Confidence interval LAP Lipid accumulation product MH-PCOS Metabolically healthy Polycystic Ovary Syndrome MU-PCOS Metabolically unhealthy Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

References

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Chen, Z.; Dunaif, A.; Laven, J.S.; Legro, R.S.; Lizneva, D.; Natterson-Horowtiz, B.; Teede, H.J.; Yildiz, B.O. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotterdam, E.A.-S.P.c.w.g. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 2004, 19, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, M.; Brennan, K.; Pall, M.; Azziz, R. The severity of menstrual dysfunction as a predictor of insulin resistance in PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, E1967–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landay, M.; Huang, A.; Azziz, R. Degree of hyperinsulinemia, independent of androgen levels, is an important determinant of the severity of hirsutism in PCOS. Fertil Steril 2009, 92, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, G.M. Syndrome X: is one enough? Am Heart J 1994, 127, 1439–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.; Chavez, M.; Olivar, L.; Rojas, M.; Morillo, J.; Mejias, J.; Calvo, M.; Bermudez, V. Polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating the pathophysiologic labyrinth. Int J Reprod Med 2014, 2014, 719050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev 2012, 33, 981–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R. Epidemiology, phenotype, and genetics of the polycystic ovary syndrome in adults. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-phenotype-and-genetics-of-the-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-in-adults?

- Lee, H.; Oh, J.Y.; Sung, Y.A.; Chung, H. Is insulin resistance an intrinsic defect in asian polycystic ovary syndrome? Yonsei Med J 2013, 54, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Davies, M.J.; Norman, R.J.; Moran, L.J. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2012, 18, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabadi, A.A.; Massaro, J.M.; Rosito, G.A.; Levy, D.; Murabito, J.M.; Wolf, P.A.; O'Donnell, C.J.; Fox, C.S.; Hoffmann, U. Association of pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and visceral abdominal fat with cardiovascular disease burden: the Framingham Heart Study. Eur Heart J 2009, 30, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Norman, R.J.; Davies, M.J.; Moran, L.J. The effect of obesity on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2013, 14, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glintborg, D.; Petersen, M.H.; Ravn, P.; Hermann, A.P.; Andersen, M. Comparison of regional fat mass measurement by whole body DXA-scans and anthropometric measures to predict insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and controls. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossner, S.; Bo, W.J.; Hiltbrandt, E.; Hinson, W.; Karstaedt, N.; Santago, P.; Sobol, W.T.; Crouse, J.R. Adipose tissue determinations in cadavers--a comparison between cross-sectional planimetry and computed tomography. Int J Obes 1990, 14, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sasai, H.; Brychta, R.J.; Wood, R.P.; Rothney, M.P.; Zhao, X.; Skarulis, M.C.; Chen, K.Y. Does Visceral Fat Estimated by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Independently Predict Cardiometabolic Risks in Adults? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015, 9, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.C.; Giordano, C. Visceral adiposity index: an indicator of adipose tissue dysfunction. Int J Endocrinol 2014, 2014, 730827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.C.; Giordano, C.; Galia, M.; Criscimanna, A.; Vitabile, S.; Midiri, M.; Galluzzo, A.; AlkaMeSy Study, G. Visceral Adiposity Index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.C.; Guarnotta, V.; Forti, D.; Donatelli, M.; Dolcimascolo, S.; Giordano, C. Metabolically healthy polycystic ovary syndrome (MH-PCOS) and metabolically unhealthy polycystic ovary syndrome (MU-PCOS): a comparative analysis of four simple methods useful for metabolic assessment. Hum Reprod 2013, 28, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Ma, F.; Lou, H.P.; Chen, Y. Visceral Adiposity Index Is Associated with Pre-Diabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Chinese Adults Aged 20-50. Ann Nutr Metab 2016, 68, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, P.; Stein, A.; Marcadenti, A. Visceral adiposity index and prognosis among patients with ischemic heart failure. Sao Paulo Med J 2016, 134, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, U.; Duran, C.; Ecirli, S. Visceral adiposity index levels in overweight and/or obese, and non-obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and its relationship with metabolic and inflammatory parameters. J Endocrinol Invest 2017, 40, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection, E.; Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in, A. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocr Rev 1997, 18, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, P.F.; Nilas, L.; Norgaard, K.; Jensen, J.E.; Madsbad, S. Obesity, body composition and metabolic disturbances in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2008, 23, 2113–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.C.; Verghi, M.; Galluzzo, A.; Giordano, C. The oligomenorrhoic phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome are characterized by a high visceral adiposity index: a likely condition of cardiometabolic risk. Hum Reprod 2011, 26, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, H.; Aggarwal, K.; Jain, A. Visceral Adiposity Index: Simple Tool for Assessing Cardiometabolic Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2019, 23, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Farias, M.; Fos-Domenech, J.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L.; Sanchez-Infantes, D. White adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity and aging. Biochem Pharmacol 2021, 192, 114723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.C.; Giordano, C.; Pitrone, M.; Galluzzo, A. Cut-off points of the visceral adiposity index (VAI) identifying a visceral adipose dysfunction associated with cardiometabolic risk in a Caucasian Sicilian population. Lipids Health Dis 2011, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Minooee, S.; Azizi, F. Comparison of various adiposity indexes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and normo-ovulatory non-hirsute women: a population-based study. Eur J Endocrinol 2014, 171, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreenidhi, R.A.; Mahey, R.; Rajput, M.; Cheluvaraju, R.; Upadhyay, A.D.; Sharma, J.B.; Kachhawa, G.; Bhatla, N. Utility of Visceral Adiposity Index and Lipid Accumulation Products to Define Metabolically-Unhealthy Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Asian Indian Women - A Cross Sectional Study. J Hum Reprod Sci 2024, 17, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, F.M.; Graff, S.K.; Spritzer, P.M. Adiposity Indexes as Phenotype-Specific Markers of Preclinical Metabolic Alterations and Cardiovascular Risk in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2017, 125, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, H.; Morshed, M.S.; Sultana, T.; Shah, S.; Afrine, S.; Hasanat, M.A. Lipid Accumulation Product Better Predicts Metabolic Status in Lean Polycystic Ovary Syndrome than that by Visceral Adiposity Index. J Hum Reprod Sci 2022, 15, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total PCOSn=180 | Phenotype An=96 | Phenotype Bn=19 | Phenotype Cn=35 | Phenotype Dn=30 | Control Groupn=51 | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 | p6 | p7 | p8 | p9 | p10 | p11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 24 (18-35) | 25 (18-35) | 22 (18-34) | 25 (18-35) | 24 (20-35) | 23 (22-33) | .457 | .191 | .191 | .950 | .408 | .103 | .353 | .954 | .322 | .099 | .500 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.5 (45-129) | 65 (44-103) | 60 (44-98) | 63.5 (44-116) | 58 (47-79) | <.001 | <.001 | .065 | .351 | .025 | .082 | <.001 | .022 | .273 | .805 | .304 | |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 25.49 (15.59-50.22) | 27.19 (17.15-49.77) | 24.83 (15.78-39.84) | 22.14 (15.59-34.08) | 24.88 (17.19-50.22) | 21.48 (17.78-27.34) | <.001 | <.001 | .028 | .146 | .006 | .111 | <.001 | .031 | .174 | .766 | .184 |

| WC (cm) | 83.5 (58-129) | 89 (61-129) | 82 (60-120) | 77 (58-105) | 78 (60-116) | 75 (59-100) | <.001 | <.001 | .041 | .237 | .160 | .065 | <.001 | .005 | .269 | .689 | .562 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 89 (56-142) | 90 (56-142) | 88 (75-109) | 88 (66-103) | 88 (78-103) | 87 (73-98) | .082 | .054 | .204 | .588 | .327 | .976 | .280 | .521 | .462 | .622 | .732 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 12.3 (2-100.5) | 13.6 (3.6-100.5) | 13.5 (4.4-35.7) | 10.1 (2.5-37.8) | 9.6 (2-30.5) | 7.3 (2.8-22) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .010 | .024 | .810 | .009 | .006 | .094 | .071 | .797 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.75 (0.38-25.57) | 2.96 (0.77-25.57) | 3.06 (0.92-7.31) | 2.30 (0.55-7.54) | 2.13 (0.38-6.55) | 1.63 (0.58-4.35) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .012 | .024 | .775 | .008 | .008 | .094 | .071 | .813 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.4 (0.9-2.4) | 1.3 (0.9-2.4) | 1.4 (0.9-1.9) | 1.6 (1-2.2) | 1.5 (1-2.4) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .493 | .124 | .737 | .001 | .021 | .022 | .071 | .617 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.9 (0.3-5.6) | 1.1 (0.3-5.6) | 0.8 (0.5-2.4) | 0.9 (0.4-2.8) | 0.8 (0.5-1.8) | 0.8 (0.3-1.5) | <.001 | <.001 | .212 | .149 | .343 | .123 | .010 | .002 | .751 | .572 | .650 |

| VAI | 1.21 (0.39-10.89) | 1.46 (0.39-10.89) | 1.31 (0.43-4.39) | 1.00 (0.41-4.79) | 1.01 (0.4-3.21) | 0.85 (0.32-1.87) | <.001 | <.001 | .013 | .117 | .244 | .331 | .003 | .001 | .289 | .124 | .803 |

| Sperarman’s rho | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.214 | 0.001 |

| Glucose | 0.077 | 0.246 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.348 | <0.001 |

| Total PCOSn=180 | Phenotype A, n=96 | Phenotype B, n=19 | Phenotype C, n=35 | Phenotype D n=30 | Controlsn=51 | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of MetS, n (%) | 38 (21.1) | 30 (31.3)*§ | 3 (15.8) | 2 (5.7)* | 3 (10) § | 0 (0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.084 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).