Submitted:

24 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

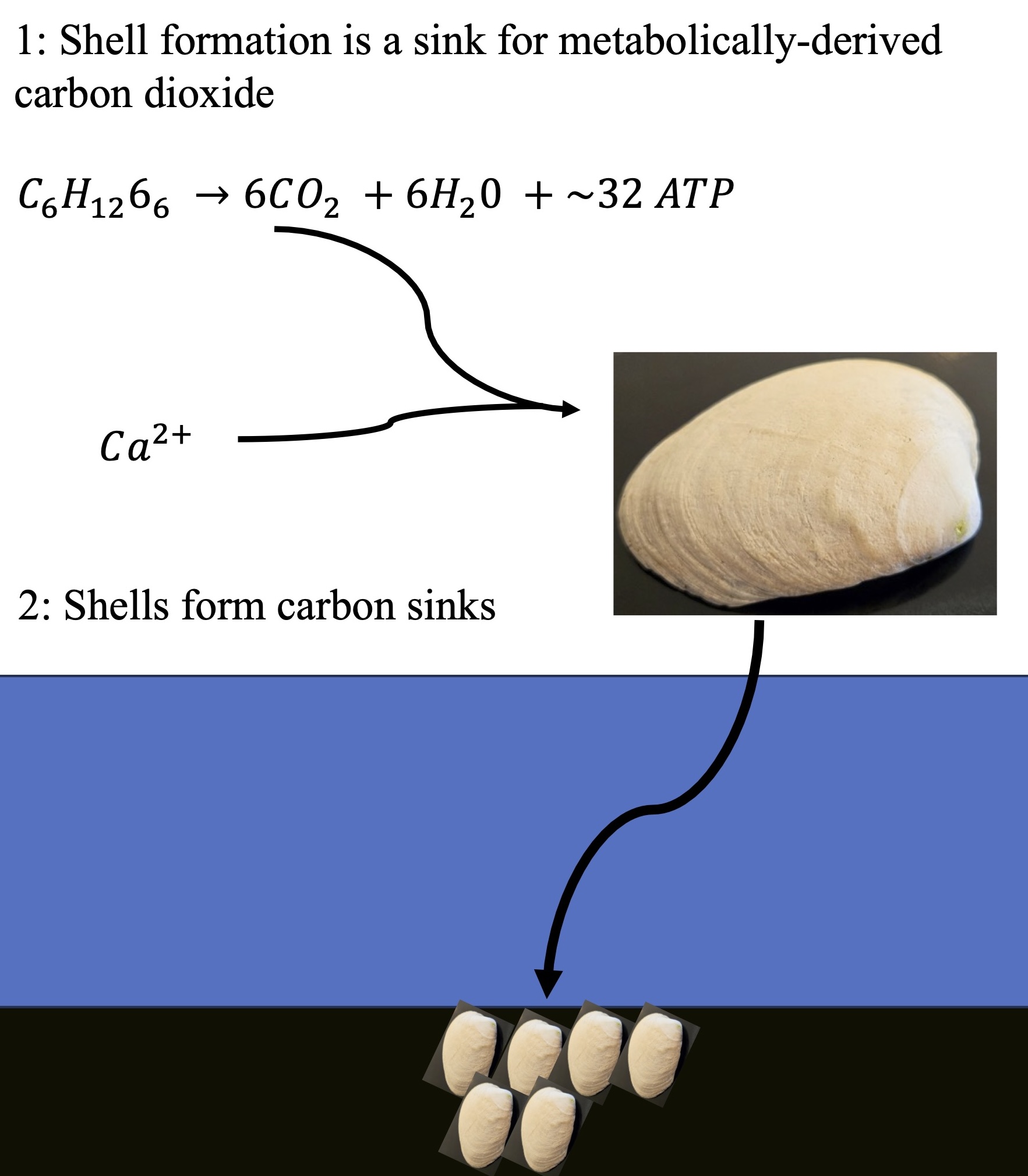

2. Does Calcareous Skeleton Formation Affect Ocean Alkalinity and Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide?

3. Does Shell Production Facilitate Oyster Respiration?

4. Concluding Remarks

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Douglas, T.J.; Schuerholz, G.; Juniper, S.K. Blue carbon storage in a northern temperate estuary subject to habitat loss and chronic habitat disturbance: Cowichan estuary, British Columbia, Canada. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 857586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.R.; Smith, S.V.; Reaka-Kudla, M.L. Coral reefs: sources or sinks of atmospheric CO2? Coral reefs 1992, 11, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yu, K.; Shi, Q.; Tan, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y. Seasonal variations of seawater p CO 2 and sea-air CO 2 fluxes in a fringing coral reef, northern S outh C hina S ea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2016, 121, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, J.J.; Soetaert, K.; Hagens, M. Ocean alkalinity, buffering and biogeochemical processes. Reviews of Geophysics 2020, 58, e2019RG000681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, K.; Ko, Y.H.; Lee, J.S. Contribution of marine phytoplankton and bacteria to alkalinity: An uncharacterized component. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2021GL093738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeebe, R.E.; Tyrrell, T. History of carbonate ion concentration over the last 100 million years II: Revised calculations and new data. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2019, 257, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, B.P.; Middelburg, J.J.; Sluijs, A.; van der Ploeg, R. Secular variations in the carbonate chemistry of the oceans over the Cenozoic. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2019, 512, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, T.; Schwarzinger, C.; Miksik, I.; Smrz, M.; Beran, A. Molluscan shell evolution with review of shell calcification hypothesis. Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part B: Biochemistry and molecular biology 2009, 154, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Song, L. Recent advances of shell matrix proteins and cellular orchestration in marine molluscan shell biomineralization. Frontiers in Marine Science 2019, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.R. Calcification in marine molluscs: how costly is it? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalding, C.; Finnegan, S.; Fischer, W.W. Energetic costs of calcification under ocean acidification. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2017, 31, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Moura, G.; Pinheiro, T.; Machado, J.; Coimbra, J. Modifications in Crassostrea gigas shell composition exposed to high concentrations of lead. Aquatic toxicology 1998, 40, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Gheorghiu, S.; Huxley, V.H.; Pfeifer, P. Reverse engineering of oxygen transport in the lung: adaptation to changing demands and resources through space-filling networks. PLoS Computational Biology 2010, 6, e1000902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachamovitch, R.; Brown, H.V.; Rubin, S.A. Respiratory and circulatory analysis of CO2 output during exercise in chronic heart failure. Circulation 1991, 84, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, T.; Araki, A.; Yamamoto, K.-i. Oxygen and acid–base status of hemolymph in the densely lamellated oyster Ostrea denselamellosa in normoxic conditions. J Nat Fish Univ 2018, 66, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, T.; Araki, A.; Kawana, K.; Yamamoto, K.-i. Acid–base balance of hemolymph in Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in normoxic conditions. J Nat Fish Univ 2018, 66, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, C.T.; Butman, D.; Jeffrey, J.D.; Suski, C.D. Freshwater biota and rising pCO 2? Ecology Letters 2016, 19, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödenbeck, C.; Keeling, R.F.; Bakker, D.C.; Metzl, N.; Olsen, A.; Sabine, C.; Heimann, M. Global surface-ocean p CO 2 and sea–air CO 2 flux variability from an observation-driven ocean mixed-layer scheme. Ocean Science 2013, 9, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanina, A.V.; Falfushynska, H.I.; Beniash, E.; Piontkivska, H.; Sokolova, I.M. Biomineralization-related specialization of hemocytes and mantle tissues of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Experimental Biology 2017, 220, 3209–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, E.; Turolla, E.; Lanzoni, M.; Moore, D.; Castaldelli, G. Manila clam and Mediterranean mussel aquaculture is sustainable and a net carbon sink. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 848, 157508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).