Introduction: Complexity and Cancer Dynamics

Cancers are increasingly recognized as complex adaptive ecosystems, shaped by multiscale interactions across genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, signaling, and environmental networks [

1]. The emerging paradigm of

complex systems theory, or

complexity science, further identifies the regulatory networks steering the long-term patterns of behavior (i.e., attractor dynamics) in tumor ecologies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Leveraging concepts from dynamical systems theory (attractor landscape reconstruction), network science, and computational algorithms, complexity science investigates how aggressive tumors, such as pediatric gliomas, behave as dysregulated developmental processes exhibiting "emergent behaviors" [

7] (

Figure 1). Emergence, articulated by Aristotle as “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” and reframed by physicist Philip Anderson’s dictum “more is different”, captures the patterns of how

complex systems, such as cancer ecosystems, exhibit collective behaviors that are irreducible to their individual components, due to multiscale, nonlinear interactions [

8,

9,

10,

11]. From flocking behavior in collective cell migration to fractal tumor architectures and chaotic dynamics in growth, and metastasis, mathematical and systems oncology reveals that cancers behave as complex adaptive systems governed by emergent behaviors [

1,

7,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Furthermore, tumor pattern formation and cancer ecology suggest that the ’self’ emerges as a collective identity, with cells navigating attractor dynamics and expressing collective agency [

11,

22]. Complexity and chaotic dynamics may also be intrinsic signatures of protein-mediated pattern formation and gene expression dynamics [

7,

14].

Thus, the study of these complex systems, and their self-organized patterns necessitates a paradigm shift from reductionism to a holistic understanding of causal processes, interdependence, and collective behavior [

9,

23]. The complexity science framework, precisely achieves this, allowing us to conceptualize cancer ecosystems as a breakdown of collective cellular intelligence and systemic decision-making, or cell fate cybernetics: the study of communication, control, and feedback regulation within

complex systems.

Recent advances in single-cell multi-omics and trajectory inference algorithms have revealed that several aggressive cancers—including leukemias, medulloblastomas, neuroblastomas, and pediatric high-grade gliomas—exhibit disrupted lineage bifurcations and differentiation arrests, suggestive of stalled developmental programs [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Under normal conditions, morphogenesis requires precise, spatiotemporal coordination of gene expression and protein signaling; a molecular choreography governed by social norms, constraints, and hierarchical differentiation cues [

11,

28]. Dysregulation of this collective dynamics impairs cell fate commitment, destabilizes bifurcation points, and generates poorly communicative, maladaptive cellular behaviors [

2,

3,

6,

7].

In our recent work, we applied complex systems approaches, including network perturbation analysis, algorithmic complexity measures, and deep learning, to single-cell transcriptomic profiles of pediatric gliomas to decipher the underlying dynamics of cellular plasticity—the ability of cells to sense, adapt, and shift identity in response to signaling cues and feedback loops [

6]. Our findings suggest that glioma cells are not merely halted developmental intermediates but exist as unstable attractor states—transitional phenotypes “trapped” in maladaptive loops along disrupted developmental trajectories [

4,

5,

6].

Plasticity, in this context, acts as the cognitive scaffold and cybernetic engine of the glioma ecosystem, enabling evolvability through nonlinear phase-transitions in cellular identity, driven by perturbations in collective network dynamics. While normal developmental cells follow regulated differentiation hierarchies and cooperative rules during pattern formation, we showed that cancer cells bypass these controls and become trapped at critical tipping points, navigating unstable attractor basins marked by indecision, hybridization, and instability [

4,

5,

6].

We propose that tumor plasticity emerges as a dynamic continuum of hybrid cellular states, fluctuating across unstable attractor landscapes. These fluctuations drive phenotypic switching in response to environmental cues—much like forecasting weather patterns—necessitating predictive and causal inference tools rooted in complexity science. Using such approaches, our recent models decoded plasticity signatures overlapping with biomarkers of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

5,

6]. This convergence suggests that the developmental blockade, and identity switching observed in pediatric gliomas may be emergent properties of shared neural circuitry involved in cognition, mental health, and neuronal differentiation.

These findings support a cognitive-behavioral paradigm in systems medicine, reframing cancer as a

disorder of cellular identity. The failure to resolve fate decisions reflects a deeper systemic breakdown in intercellular communication and neural-like plasticity circuits. These cybernetic dysfunctions fracture the cooperative dynamics and ecological cohesion essential for morphogenesis, as shown in single-cell studies [

6,

25,

29]. Glioma cells appear suspended in liminal states, co-expressing mixed lineage markers without terminal differentiation—signaling a cybernetic blockade and semiotic crisis along their developmental trajectories. The collapse of developmental, ecological, and communicative networks produces disordered self-organization, manifesting as fate indecision and hybrid plasticity. Building on this, our investigation of a neurocognitive-behavioral axis in cancer dynamics reveals promising synergies with systems-level strategies from precision psychiatry. This is further supported by emerging evidence of neuron–glioma synapses and the rise of cancer systems neuroscience as a framework to decode tumor ecology and its underlying semiotics [

30,

31,

32]. To reconcile these insights into a transdisciplinary framework, we present this perspective to open novel therapeutic avenues for the precision treatment, prediction, and patient care in cancer medicine.

Cell Fate Bias and Neuronal-Like Identity in Glioma: A Crisis of Cellular Identity

The nervous system governs both development and cancer progression, with cancer neuroscience emerging as a new field examining how neural-cancer communication, synaptic signaling, and systemic feedback loops influence tumor behavior [

30]. These interactions—from electrical activity to neurotransmitter control of stem cell proliferation—suggest gliomas hijack neural plasticity and developmental programs as cybernetic miscommunications. Studies reveal glioma cells form functional glutamatergic synapses with neurons, promoting growth and resistance [

31,

32], supporting a systems neuroscience perspective of cancer. Recently, Barron et al. demonstrated that GABAergic neurons form synapses with Diffuse Midline Glioma (DMG) cells to drive their progression [

32].

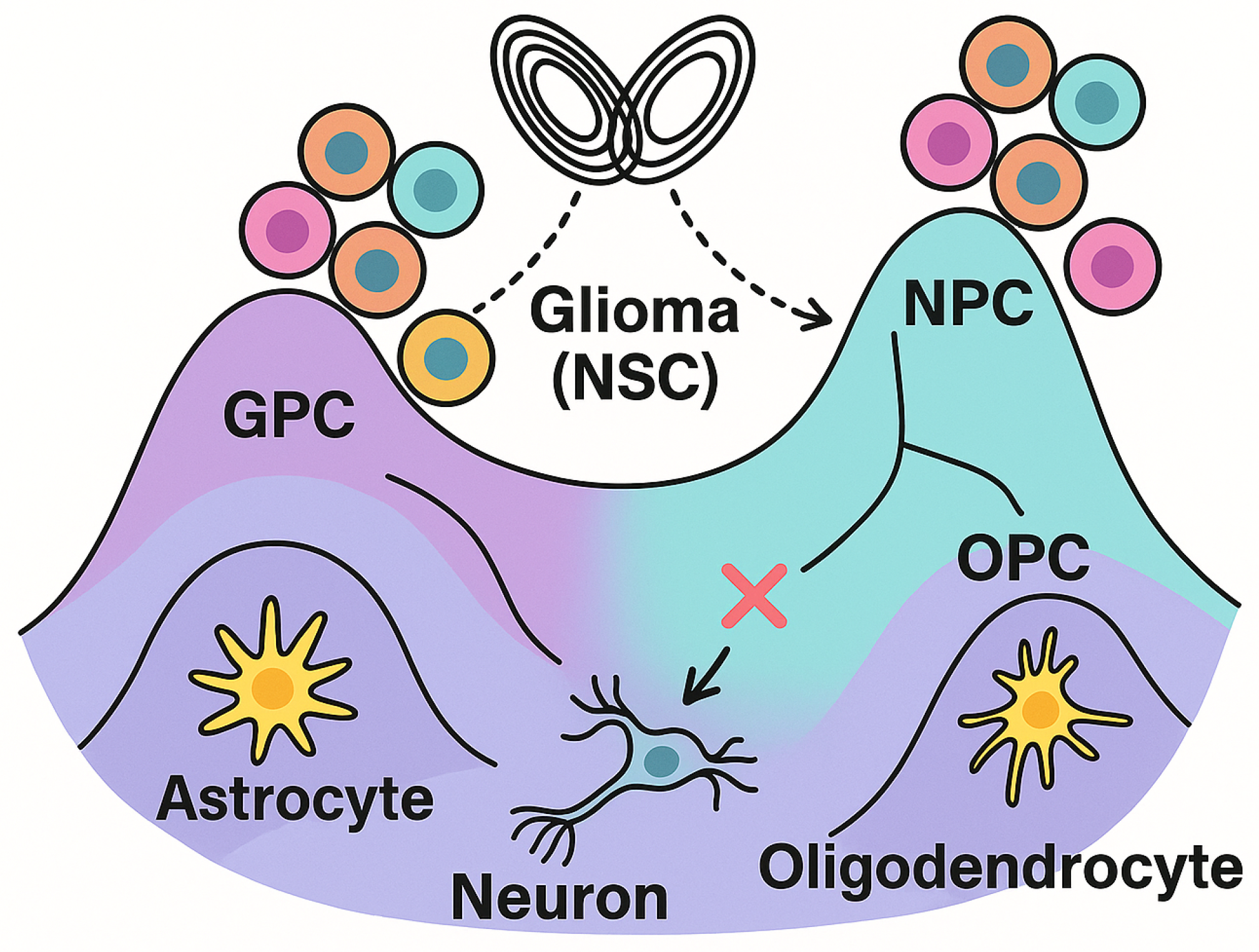

Wang et al. (2025) performed trajectory reconstruction using single-cell RNA-seq data from diverse brain tumors—including pediatric gliomas and medulloblastomas—to infer their developmental origins. They identified trilineage bifurcation patterns tracing back to NPC (neural progenitor), OPC (oligodendrocyte progenitor), and astrocytic lineages, showing that NPC/neural stem cell (NSC)-like states are cell of origins in gliomas. The analysis further revealed attractor-like dynamics governing cell state transitions during tumor evolution, as a developmental blockade from terminal differentiation [

29].

Complementary findings from adult glioblastoma research support this attractor landscape and developmental arrest. Couturier et al. (2020) demonstrated that adult glioblastomas recapitulate a trilineage developmental hierarchy—astrocytic, oligodendrocytic, and neuronal-like cell states, recapitulating neurodevelopmental programs through a conserved attractor landscape. This developmental attractor was found to be governed by plastic, progenitor-like cells at the apex, which drive maladaptive behaviors, including, heterogeneity, therapy resistance, and malignant evolution [

33].

We observed similar trilineage attractor dynamics in pediatric glioblastoma and DMGs, where indecisive cell fate decisions and plasticity are steered by unstable developmental trajectories and feedback-regulated network hubs, as identified through algorithmic complexity-based reconstructions of tumor cell state-transitions [

4,

5,

34]. A fate bias toward NPC and neuronal-like identities was also observed across both pediatric glioma subtypes, further supporting the presence of developmentally arrested yet teleonomically acnhored cell fate trajectories [

4,

5,

34].

In further support, Drexler et al. (2024) showed that synaptic gene expression becomes progressively upregulated along the tumor trajectory in DMGs, with neuron–glioma synaptic genes emerging as prognostic markers [

35]. This suggests that as DMG cells evolve, they increasingly integrate into neural circuits through neuron-like communication, an emergent, maladaptive behavior correlated with poor prognosis. However, our findings suggest that the enrichment of neuronal markers may reflect an intrinsic differentiation program, pointing toward a teleonomic endpoint of cell fate identity that is developmentally favored [

4,

5,

34].

Spitzer et al. (2025), in a longitudinal single-cell study of adult glioblastomas, reported that tumor progression is marked by the emergence of NPC-like and neuronal (NEU)-like malignant states at recurrence. These states showed upregulated neuronal markers and synaptic genes linked to poor prognosis [

36]. In specific, neuroligin (

NLGN) and neuregulin (

NRG) families—typically expressed in neurons and oligodendrocytes—were predicted to interact with

NRXN and

ERBB4, suggesting enhanced neuron-glioma synaptic integration. These NEU-like states exhibited enrichment for postsynaptic genes such as

GRIN1,

GRIN2A,

GRIN2B, and

GABRA1/

GABRA4, highlighting a shift toward neuronal programs during tumor evolution [

36]. Many of these markers, including GRIN, GRIK, ERBB2/3, NRXN1/3, and GABRA, were also identified in our independent analyses using multiple pediatric glioma datasets and neuronal reprogramming models, reinforcing the robustness of these neuronal-like signatures [

34,

37]. However, we observed mixed neurotransmitter signaling, with both excitatory (e.g., glutamatergic) and inhibitory (e.g., GABAergic) components, suggesting a plastic, and hybrid synaptic phenotype rather than a purely GABAergic state [

34,

37].

Similar developmental convergence was observed in pediatric gliomas. Sussman et al. (2024) conducted longitudinal single-cell and spatial multiomic profiling across 16 pediatric high-grade glioma (pHGG) samples. Parallel to the findings in adult GBM, they identified malignant states expressing neuronal and progenitor-like features [

38]. Importantly, they reported upregulation of synaptic gene programs, including the neurexin-neuroligin (

NRXN-

NLGN) pathway, GABAergic receptors, and other postsynaptic signaling modules—especially enriched at recurrence [

38]. Furthermore, these findings reveal that both adult and pediatric gliomas navigate conserved attractor pathologies—shared developmental landscapes marked by arrested differentiation and progenitor-driven plasticity.

While previous studies emphasized the glioma–neuron connectome, our deep learning and complex systems–driven findings suggest that pediatric glioma–intrinsic expression of neurotransmitter receptor pathways reflects autonomous synaptic-like signaling within glioma ecosystems [

5,

6,

34]. This implies not only the presence of complex interactions, but an internalization of neurocognitive circuitry within the glioma transcriptome itself. These signatures may further suggest a latent neuronal fate bias or teleonomic direction embedded within the tumor’s attractor landscape.

Deep learning decodes plasticity signatures linking psychiatric disorders to cell fate identity

We confirmed the presence of neuronal lineage markers in pediatric glioma ecosystems using distinct computational frameworks [

4,

5,

6,

34]. However, the motivating factor for this perspective was our recent findings in [

6], which demonstrated deep learning-based decoding of plasticity signatures in pediatric high-grade gliomas. In this study, we demonstrate that these brain tumors arise from cells that became "stuck" during normal brain development. The cancer cells are ’confused’ about their identity and cannot decide whether to become neurons, support cells, or ’something else’. They exploit this plasticity to resist treatment and survive. Importantly, our artificial intelligence (AI)-driven algorithms identified specific genes that control these identity switches, suggesting that these brain tumors might be understood as "cellular identity disorders" [

6].

Normally, as a fetus’s brain develops, neural stem cells (NSC) need to collectively "decide” what type of brain cell to become—much like choosing a career, or our functional roles in a society, reminescent of Durkheim’s organismal view of sociology [

39]. However, these tumors resemble cells that disrupt these social networks and ecological dynamics, and remain stalled at a developmental crossroads and cannot commit to one path. Instead, they continually switch between different identities (i.e., plasticity), which drives their aggressivity, but also as argued herewith, serves as their Achilles’ heel; a therapeutic vulnerability. Instead of labeling or "othering" these cells as ’socially deviant’ [

40], we should seek to reintegrate them into the organism as functional members of the cellular society (

Figure 2).

Key Findings

1. Cancer Cells Are “Trying” to Become Neurons

The tumor cells express markers showing they’re attempting to develop into neurons, specifically those found in the prefrontal cortex (the brain’s most advanced region for thinking and decision-making) [

6]. We typically think of cancer as disorderly and destructive, but these cells appear to have a teleonomy (goal-directed behaviors)—a favored lineage or fate bias—they want to become neuronal-like identities, but are developmentally stuck in a pathological basin of attraction. This challenges our view of cancer as purely "malignant", and instead reframes their collective dynamics as ’maladaptive behaviors’ [

6]. This description is not meant to anthropomorphize cancer dynamics, but to reflect principles of cell fate cybernetics (i.e., decision-making processes) and collective cellular intelligence. Here, the language of “trying” is used as a metaphor for underlying regulatory dynamics and self-organized behavioral patterns along a teleonomic trajectory.

2. Sperm and Testis Genes Active in Brain Tumors

As further evidence of disrupted morphogenesis and aberrant developmental processes, the researchers found multiple testis-specific antigens and spermatogenesis-related genes (like

SPATS2), and associated long non-coding RNA (lncRNAs), active in these brain tumors [

6]. What are reproductive genes doing in brain cancer? This might be self-evident as a signature of disrupted developmental processes, an onco-fetal link as many developmental gene programs are disrupted in cancer formation. However, we speculate that these tumors may exhibit ‘confused identities,’ with developmental signatures acting as vestigial markers—reflecting the aberrant activation of contextually inappropriate morphogenetic programs. We observed similar transcriptional programs, including dysregulation of sex-linked determinants such as X-inactivation via

XIST, across independent findings derived from distinct algorithmic approaches, further supporting the notion of disrupted identity programs in these tumors [

4,

5].

Cancer–testis antigens (CTAs) are increasingly recognized as emergent biomarkers of epigenetic dysregulation across diverse malignancies. Their aberrant expression, normally restricted to germ cells, reflects widespread chromatin remodeling and epigenetic deregulation in cancer. For instance, Li et al. report that CTAs become ectopically expressed in tumors through deregulated epigenetic programs, contributing to altered tumor-immune interactions [

41]. More recently, Naik et al. highlighted CTAs as emerging therapeutic targets that exploit genomic instability and epigenetic reprogramming in cancer [

42]. While this conventional paradigm frames CTA expression as a hallmark of dysregulated epigenetics, developmental plasticity, and disrupted developmental programs, the objective of this perspective is to challenge such reductionist views and propose counterfactual narratives that reframe these signatures within the broader lens of cell fate cybernetics and fate identity dynamics.

3. AI Algorithms Agreed Despite Different Approaches

Multiple AI and deep learning algorithms, including Hopfield networks, variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), graph convolutional networks (GCNs), graph attention networks (GATs), and others—independently identified overlapping sets of genes as critical, with statistical significance (). These AI approaches operate in fundamentally different ways: some model epigenetic (energy) landscapes, others learn statistical patterns, and others build topological representations of gene networks, as proxies of the attractor landscapes. The consistent convergence on gene sets enriched in neuronal markers, and transition genes (plasticity signatures), across distinct methods serves as strong validation of the robustness of these findings.

4. "Transition Therapy" Could Replace Killing Cancer Cells

Another important concept is the possibility of "differentiation therapy", or cell state-"transition therapy" [

43]. Instead of aiming to kill cancer cells, and destroy their ecosystem——a strategy that often fails or results in lifelong side effects—our findings propose that it might be possible to redirect these indecisive cells into cancer reversion, or maturing into functional brain cells [

6,

37]. In other words, rather than eliminating them, we could push them to finally "choose a career" and become healthy neurons. Supporting this concept, Liao et al. demonstrated that exogenous expression of

NRXN1 can reprogram adult glioblastoma cells toward neuronal-like identities [

44]. In our recent study, we also supported this for the first time demonstrating that BT245 cells from H3K27M pediatric high-grade glioma can be reprogrammed to neuronal-like identities via previously established neuronal differentiation cocktails [

37]. NRXN1 and NRXN3 were among the top upregulated differentially expressed genes post-treatment [

37]. These findings support the idea of “differentiation therapy”, guiding cancer cells to complete their developmental programs; re-steering them toward teleonomy and potentially functional, stable identities.

5. Brain Tumors Share Genes with Schizophrenia and Autism

The most important finding, central to our perspective, is that the plasticity markers identified across all algorithms converge with well-known psychiatric susceptibility genes. Although some associations are debated, genes such as

FXYD6,

SEZ6L, and

FKBP5, found to drive plasticity in these childhood brain tumors, are also implicated in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and autism. In a separate study [

5], we identified these same markers—along with

SOX11 and

RPS4Y1—as network biomarkers and transition genes, associated with psychiatric conditions [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. While disrupted neurodevelopmental processes and molecular mechanisms are shared by gliomas and psychiatric conditions, the convergence of our plasticity (transition) signatures, as susceptibility genes or diagnostic biomarkers of psychiatric disorders, suggests brain tumors and mental health conditions might be different manifestations of similar developmental dysregulations, or at different scales of collective intelligence [

22].This opens the door to potentially repurposing psychiatric medications for cancer treatment [

54].

For instance, Trifluoperazine (TFP), an antipsychotic medication, has been proposed for drug repurposing to treat glioblastoma, possibly by modulating ferroptosis, and pathways such as calmodulin and

-catenin signaling [

55]. Interestingly, our deep learning-driven findings also reveal dysregulation of iron metabolism, and implicate calmodulin and Wnt/

-catenin signaling as key drivers of glioma plasticity. Iron metabolism was found as a central vulnerability in both glioma subtypes with iron metabolism genes (e.g., FTH1, FTL, SLC40A1, etc.) as critical nodes in their networks. Furthermore, one of our reprogramming cocktails in differentiating H3K27M pediatric gliomas towards neuron-like states, included a Wnt activator (via GSK3 inhibition), and WNT7A/B were among the top 20 differentially expressed genes post-reprogramming [

37]. De Silva et al. further suggest that patients receiving antipsychotics may even exhibit a reduced risk of developing cancers, including brain tumors [

55].

It is important to note that the observed convergence between glioma plasticity signatures and psychiatric susceptibility genes is based largely on computational overlap rather than functional validation. We acknowledge that shared markers may reflect broader epigenetic dysregulation of neurodevelopmental programs, as framed within evidence-based models, rather than shared pathogenic mechanisms. Nonetheless, these observations allow us to reconceptualize cancer ecologies as complex adaptive systems shaped by collective cellular intelligence.

Study Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations in our discussed works. First, the proposed links between psychiatric disorders and glioma transcriptomics are largely derived from computational analyses, which require further validation through functional assays and experimental studies. However, our recent cell fate reprogramming study in pediatric glioma cell lines provides a promising starting point [

34]. Second, the datasets originate from a limited number of patients, raising concerns about generalizability. Third, there is a need for more diverse patient samples to capture the full spectrum of tumor complexity. Finally, although supported by previously reported longitudinal analyses, our current findings provide only static snapshots of tumors. Future research must track tumor evolution over time to unravel the complex dynamics underlying these cellular identity shifts.

This work is deliberately framed as a counterfactual perspective, an opinionated synthesis, intended to challenge traditional scientific lenses and open new avenues of systems-level thinking. While our computational findings highlight robust patterns of developmental arrest driven by epigenetic plasticity (the adaptability engine), we stress that correlation is not causation: overlaps of transition genes across psychiatric and glioma datasets remain associative and require evidence-based, functional assays, longitudinal attractor reconstructions, and rigorous statistical validation to establish causality. The telos here is not to claim definitive mechanisms, but to initiate a ’research program’ that invites deeper experimental testing and integrative validation, rooted in complex systems theory.

Differentiation Therapy as Restoration of Cellular Identity

We propose that these childhood brain tumors are essentially cells having an "identity crisis", and phenotypic plasticity as the cognitive scaffold driving maladaptive behaviors, such as heterogeneity, invasion, and therapy resistance (recurrence). By understanding this crisis and the transition genes involved, we might be able to develop safer precision therapies that guide cancer cells back to normal development. This overturns conventional cancer treatment philosophy. Instead of relying on toxic interventions like chemotherapy (poison), radiation (burning), or surgery (cutting), we might be able to redirect cancer cells toward a stable identity, simply by re-establishing the disrupted dialogue (miscommunication) in signaling and transcriptional networks in glioma ecologies. “First, do no harm” (primum non nocere) and the Hippocratic notion of the vis medicatrix naturae, realign with this healing approach, guiding systems back toward their intrinsic trajectories of self-organization and repair. Not to mention, healing derives from the Old English term hǣlan, meaning “to make whole,” rooted in the Latin salus, meaning, ’wholeness’.

From a psychological paradigm, this resembles the distinction between rehabilitation and operant conditioning (punishment), favoring a more humane, developmentally grounded systems medicine approach to restoring stable cell fate identities within tumor ecosystems. Psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut viewed psychiatric illness as a disruption of self-cohesion rather than a structural defect [

56], advocating healing through reintegration and wholeness, paralleling the paradigm shift toward complexity science and systems medicine proposed herein. Alongside Kohut, psychiatrists including Carl Jung and R.D. Laing, were pioneers in envisioning psychiatric disorders as opportunities for integration toward wholeness; as transforming their archetypal patterns of behaviors (attractors) [

57,

58]. Laing argues that psychosis is an adaptive strategy born from a fragmented sense of self—what he terms a "divided self"—as individuals navigate the unbearable stressors and pressures of their social world [

58]. We argue that these psychiatric perspectives can be extended to cancer’s identity crisis, and reframe “differentiation therapy” as a process of reintegrating divergent self-states, marked by phenotypic switching and cellular heterogeneity in tumor ecosystems, into a cohesive, adaptive whole.

Conclusions

The presented perspective, in light of emerging findings, collectively suggest that pediatric brain cancer may not simply reflect ’uncontrolled cell proliferation’, but rather a profound identity crisis, i.e., a phase transition or bifurcation event akin to a catastrophe in dynamical systems theory, a process that might, in principle, be (epigenetically) reversible. Irrespective of pediatric or adult subtype, such "identity crises" may represent a unifying feature of cancer ecosystems more broadly, emerging from shared disruptions in cellular decision-making. Reconstructing the attractor landscapes of these tumor ecologies through complex systems modeling enables us to decode the latent topologies and network dynamics that steer cell fate bifurcations and phenotypic plasticity.

Our findings support integrating complexity science into precision oncology by reframing pediatric gliomas as “behavioral pathologies” of misregulated development and disrupted cellular communication. These tumors behave as complex cybernetic systems, where aberrant plasticity and signaling dynamics reflect not just instability but latent reprogrammability. Converging with precision psychiatry, this perspective opens novel therapeutic avenues grounded in the biopsychosocial model, employing cell fate reprogramming and ecosystem engineering strategies, such as differentiation therapy, to restore teleonomic trajectories and reintegrate fragmented cellular identities in tumor ecologies towards systemic wholeness [

57].