1. Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, labeling it as a public health emergency with anticipated tragic social and economic consequences [

1]. The rapid spread of the virus highlighted the urgent need for coordinated responses, ranging from preventive measures to large-scale health including COVID-19 vaccinations [

2,

3]. Effectiveness of vaccination on alleviating the consequences of COVID-19 on individuals and the communities was reported in numerus number of studies, even with a one-dose strategy [

4,

5].

Oman, in 2016, scored 99% out of total score of 127 for all criteria within the effective vaccine management (EVM) assessments conducted globally by the WHO and UNICEF in 90 countries [

6]. This experience aided in setting up a strong foundation for national vaccination campaigns that aimed to ensure quick delivery of high-quality vaccines during the pandemic COVID-19. Additionally, Oman has an ongoing collaboration with major international bodies that influence vaccine access and immunization policy. It has maintained good coordination and consultative negotiating channels with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (a global public–private partnership that helps improve access to vaccines, especially in low- and middle-income countries) and other vaccine manufacturers ensuring availability of vaccines specifically during emergency situations [

7].

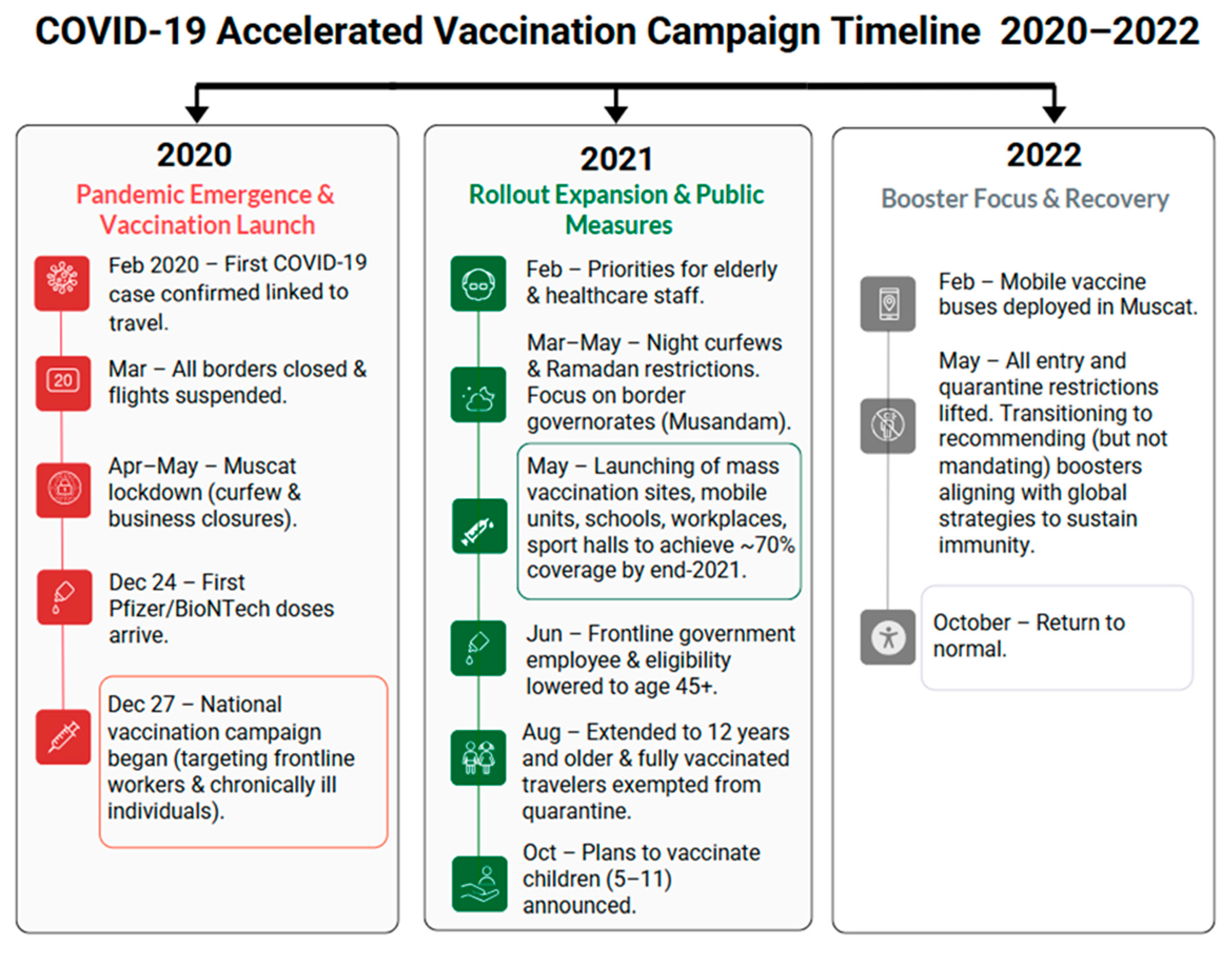

Oman launched its COVID-19 vaccination campaign in December 2020, implementing a structured and phased approach to immunize its population (

Figure 1) [

8]. Initially, the vaccination effort prioritized high-risk groups due to limited vaccine supplies and in-tense global demand. This priority framework targeted vulnerable populations, including frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) and individuals with chronic health conditions, to mitigate the immediate impact of the pandemic. Following this, Oman established a strategic objective to vaccinate 70% of its total population, which was planned to occur in two phases: the first phase aimed to cover 30% starting in late 2020, and the second phase planned to reach the remaining 40% from July to October 2021[

9].

To facilitate this extensive rollout, Oman set up mass vaccination centers throughout its governorates and collaborated closely with the private sector, enhancing accessibility and distribution efficiency. However, despite these efforts, the campaign faced significant challenges. These included limited vaccine production capacity, issues with timely procurement exacerbated by difficulties obtaining pre-booked vaccine quantities through the global COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility, which pushed for direct purchase of vaccines from the vaccine manufacturers at much higher prices than the quantities booked through COVAX [

9,

10,

11].

A case study of the Musandam, a border region in Oman, highlighted the success of rapid vaccine deployment in prioritizing first-dose administration in a vulnerable community [

12]. Within a month, vaccine coverage in this region surged from 20% to 58%, correlating with a marked reduction in community transmission and a 75% decrease in COVID-19-related hospitalizations. This targeted, expedited approach provided critical evidence for the effectiveness of prioritizing high-risk border areas in curbing the pandemic’s health impacts [

11,

12].

Vaccine hesitancy was addressed using a variety of approaches aimed at building public trust and encouraging uptake. Key government and community figures, including the Minister of Health, were prioritized to receive the vaccine early, serving as advocates and role models to promote confidence. Information campaigns disseminated data on the vaccine’s effectiveness both globally and within the country, utilizing multiple media platforms to reach diverse audiences. Success stories from other nations that had managed to control the pandemic through vaccination were publicized to reinforce positive perceptions. Initially, vaccination coverage updates were shared daily and later shifted to a weekly schedule, paired with reports that highlighted improvements in the national epidemiological situation. As an incentive, fully vaccinated individuals without symptoms were exempted from testing and quarantine requirements. Additionally, implementing vaccination mandates for entry into public events, educational institutions, and workplaces proved influential in motivating the public to get vaccinated. These combined strategies effectively contributed to overcoming reluctance and boosting vaccine acceptance.

According to the publicly available data from Reuters research, Oman has administered at least 7,068,002 doses of COVID-19 vaccines during the peak times of the pandemic. Assuming every person needs 2 doses, the reported doses were enough to have vaccinated about 71% of the country’s population by July 15th, 2022 [

13]. The accelerated COVID-19 vaccinations were positively reflected on Oman’s COVID-19 low mortality rates in vaccinated populations (<1%, even during Omicron surges) [

14,

15,

16].

2. The Objective of the Review

In this review, the WHO six building blocks framework were utilized to examine the experience of the accelerated COVID-19 mass vaccination campaign implemented in Oman during the period of the pandemic from February 2020 to October 2022 highlighting its strengths, identifying challenges/weaknesses and drawing key lessons learned (

Table 1). This experience can be used to enhance the public health emergency preparedness, and response national policies/plans.

3. The WHO Health System Building Block Framework

The WHO health system building blocks framework offers a systematic approach for analyzing and strengthening health systems. It identifies six core components that interact to achieve improved health outcomes, equity, responsiveness, financial risk protection, and efficiency [

17]. Leadership and governance include policy guidance, system supervision, accountability, and strategic alignment. Service delivery emphasizes the provision of safe, effective, and quality health services to those in need. Health workforce emphasizes the availability, competence, and equitable distribution of trained personnel. Health information systems involve the generation, examination, analysis, distribution, and use of reliable data for decision-making. Access to essential medicines, vaccines, and technologies ensures that critical health products are available, affordable, and of assured quality. Health system financing addresses the mobilization and allocation of resources to provide services without causing financial strain. The framework underscores that these components are interconnected; weaknesses in one area can undermine the overall system’s performance in various contexts. Applying the building blocks in policy and program evaluation helps identify gaps, prioritize interventions, and promote resilience, particularly during public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

18,

19]. Its adaptability renders it a valuable tool for guiding national and international health initiatives.

4. The COVID-19 Accelerated Vaccination Campaign in Oman across the WHO Health System Building Blocks

4.1. Firstly, Leadership and Governance

A Supreme Committee, including all relevant stakeholders from different sectors, was formed to deal with COVID-19 pandemic disease progression in March 2020. The multi-stakeholder arrangements accelerated rollout and sustained coverage through 2021–2022. Priorities were focused on responding to the pandemic threat through harmonizing responsiveness and minimizing the impact of the pandemic on life, health, and social, and economic aspects. The strong and high political will to accelerate the vaccination campaigns were governed by the Ministry of Health (MoH). The MoH led a unified strategy, supported by inter-ministerial collaboration to facilitate the national and regional teams to working promptly towards accelerating the vaccination campaigns. With launching the COVID-19 vaccinations on December 27, 2020, decisions in prioritizing HCWs, high-risk groups and border regions (Musandam governorate, a high-risk border region) were strategies to enhance the protection and preserve the health care workforce [

6]. Decentralized leadership was reflected in the enhancing HCWs exposure risk assessments, initiating of outreach teams, facilitating Public Private Partnership (PPP), and informing the public. Management of false media through weekly press conferences led by the minister of health played a big role to reduce vaccine hesitancy and encourage vaccine acceptability. Visible vaccination of government and community leaders served to build confidence in the vaccine’s safety and efficacy. Transparent reporting vaccine side effects was encouraged and well monitored [

20,

21].

Moreover, the Minister of Health and other members of the supreme committee addressed questions related to vaccine hesitancy from public (questions posted in MoH twitter prior to conference) and media representatives. Additionally, utilizing social media platforms and community influencers presented an avenue to disseminate ac-curate information and counteract misinformation. Implementing measures such as waiving quarantine for vaccinated individuals and mandating vaccination for access to public spaces incentivized uptake. Moreover, an MoH call center and telemedicine services were used to respond to public queries 24/7 throughout the pandemic in which all public quires on vaccinations were addressed at any time [

22].

4.1.1. Role of Other Core Government Sectors:

Under the governance of the healthcare, other sector played vital role to augment and maximize the accelerated COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Oman. The education sector played a vital supporting role in utilizing the school halls and university spaces as vaccination centers, thus expanding the infrastructure available for mass immunization. Academic institutions also facilitated the rapid training of healthcare personnel on the required public health skills and competences to support the vaccination campaign, thereby strengthening the operational capacity necessary for large-scale vaccine delivery.

Logistics and transportation were pivotal to the campaign’s success. For example, the Oman Automobile Association established drive-through vaccination facilities, thereby improving accessibility for individuals with mobility challenges or those residing in remote locations. Aviation authorities coordinated the timely importation and distribution of vaccines, maintaining the integrity of cold-chain protocols throughout the supply chain approved by the MoH.

Security agencies, notably the Royal Oman Police, were essential in enforcing movement restrictions during lockdowns and in maintaining order and safety at vaccination sites, safeguarding both staff and the general public. The tourism and hospitality sector contributed further by providing hotels for quarantine purposes and adapting various venues to accommodate large-scale vaccination efforts, thus expanding recipient capacity.

Media and risk communication strategies were also integral, with government agencies collaborating with media outlets to disseminate accurate information, counter misinformation, and communicate eligibility and coverage targets. This approach fostered public trust and promoted vaccine acceptance.

Collectively, these sectoral contributions formed an integrated support network that underpinned the success of Oman’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign, illustrating the crucial role of cross-sectoral collaboration in effective public health emergency responses [

7,

9,

10,

11].

4.1.2. Integrating Public Private Partnership

With the COVID-19 surging, private health providers augmented capacity through supported outreach vaccination and seconded nurses and doctors to public vaccination centers [

23]. Specific examples include Badr Al Samaa Group operating a large vaccination center at the National Museum and the Oman Convention and Exhibition Center (OCEC), administering thousands of Pfizer doses to employees from more than 450 companies [

24]. Pricing arrangements also enabled employer-paid vaccination through private hospitals, with MoH setting per-dose and administration fees for private-sector clients [

25,

26]. Additionally, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) funding closed delivery gaps and accelerated procurement. Notably, Occidental Oman contributed US

$2.5 million to vaccine procurement under an MoH agreement [

27], and Oman LNG pledged six million OR (US

$15,615,789) to support pandemic efforts, including the health sector [

28]. The Oman Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OCCI) mobilized the business community, donating one million OR (US

$2,601,517) for COVID-19 mitigation and urging private-health institutions to prioritize staff vaccination [

29]. Commercial banks likewise made major contributions early in the response and employers organized on-site or facilitated clinic-based vaccination for workers, often coordinated with private hospitals [

25].

4.1.3. Role of the Community and Volunteers

The involvement of both community and volunteer work in healthcare and public health is a well-established practice in Oman [

30]. Since 1991, the MoH has promoted a community participation model that emphasizes the collaboration of local groups in implementing public health initiatives aimed at improving the overall health of the population [

10,

31]. This strategy led to the implementation of the healthy cities and healthy villages initiatives, which are actively supported by community members. When responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, Oman was able to utilize its prior experience with community engagement gained from previous outbreaks such as the H1N1 influenza in 2009 and ongoing efforts to eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases like measles [

11,

32]. Throughout the pandemic, from early 2020 to mid-2022, communities played a crucial role in adopting preventive measures and supporting the adaptation of healthcare services. Their involvement was instrumental in spreading accurate information across various levels, particularly during the vaccination campaigns, where it helped to reduce vaccine hesitancy [

11,

33].

Community adherence to non-pharmaceutical and public health interventions, including social distancing, mask-wearing, and hand hygiene, contributed substantially to limiting disease spread [

11,

34]. These behaviors were further encouraged through government regulations. Healthy cities and villages provided essential support by coordinating and motivating individuals to comply with national health policies. For instance, the Al Buraimi healthy city launched a community-driven campaign called “We are all responsible,” which aimed to raise awareness about social distancing, hand sanitation, and mask use, particularly during religious events such as Eid and Ramadan, advising residents to avoid large gatherings and stay at home when possible [

9,

32]. Equally important, in Nizwa, the healthy city initiative fostered collaboration between civil society and academic institutions to strengthen community empowerment. These projects involved the development and distribution of reliable health education materials to improve public understanding of COVID-19 and promote compliance with precautionary measures. Messages also addressed the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle through balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, smoking cessation, mental wellbeing, and care for the elderly and bed ridden individuals. These activities were mediated through billboards and social media channels. The community in Nizwa actively participated in discussions and seminars on their role in managing the pandemic and coping with related stresses, facilitated through virtual meetings and training sessions that encouraged direct interaction [

10,

35].

Wilayat health committees (a well-organized administrative local structure across all regions in Oman) played a vital role in fostering multisectoral collaboration during the pandemic by identifying local social, health, and lifestyle challenges and proposing solutions, which culminated in community-based projects. Civil society organizations, mostly volunteers, were also instrumental; they mobilized resources and distributed medical equipment to help vulnerable groups continue treatment at home. A notable example is the support from the geriatric civil society, which supplied home oxygen concentrators to COVID-19 patients, enabling them to receive care at home under the supervision of family physicians connected to local health centers. This initiative effectively reduced the burden on healthcare facilities and shortened the duration of hospital stays, demonstrating the positive impact of community engagement in managing the pandemic [

32].

4.2. Secondly, Service Delivery and Health Care Responsiveness

Multi-sectoral sites were utilized to reach to a wider population and improve urban access for vaccination including drive-through facilities, mobile units, and home vaccination services for elderly and vulnerable individuals. Different sites included: schools, mobile units, governmental, and private hospitals. To deliver high quality and safe vaccinations, volunteers and non-governmental organizations were approached to handle mass gatherings and overcrowd [

6]. Efficient triaging mechanisms were established at different sites for early detection of high-risk cases. Hospitals and emergency departments were restructured to adhere to infection prevention and control protocols [

10].

Regional vaccination management teams were established with meticulous setups including :1) controlling mass gatherings via implementing safety protocols, 2) administering the vaccine safely, 3) reporting of side effects, 4) responding to potential vaccine reactions, 5) monitoring of vaccine cold chain strategies, 6) providing wide waiting areas with physical distancing, and 7) instant printing of vaccination certificates.

Primary health care (PHC) services, encompassing both facilities and HCWs, played a pivotal role in implementing clinical, public health, and safety measures across all vaccination centers. The patient flow within PHC-led vaccination sites followed a structured and pragmatic sequence. Upon arrival, clients underwent screening for risk factors, including temperature checks, before being directed to designated waiting areas where physical distancing and mask use were strictly enforced. Utilizing a smart queuing system, clients were then called to assigned rooms or booths, where trained nurses administered vaccines in accordance with established safety protocols and provided information on potential adverse effects. Following vaccination, clients were instructed to remain under observation for approximately ten minutes before receiving a printed vaccination certificate along with an appointment for their subsequent dose. The entire process, from entry to exit, typically required 20–30 minutes [

36]. Despite the critical contribution of PHC in crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic including patient screening for respiratory symptoms, early case detection, provision of psychosocial support for vulnerable populations, and mitigation of hospital service demand these efforts remain insufficiently documented in the literature [

37].

4.2.1. Evidence for COVID-19 Vaccination

Upon completion of vaccination, individuals were issued a COVID-19 vaccination certificate through the electronic “Tarassud+” system. This electronic certificate included essential personal information, vaccine details, and a unique digital verification element to certify its authenticity. The system supported digital access, allowing recipients to download or present their certificates via mobile applications or online platforms, suitable for domestic needs such as workplace entry and for international travel compliance. The certificate served as official proof of vaccination, which was crucial for enabling movement during times of restrictions and for meeting travel requirements that mandated vaccination proof. Furthermore, the digital nature of the certificate helped curb the issuance and circulation of fraudulent documents by enabling secure verification by authorities through encrypted codes or QR codes linked to the national vaccination database. This ensured that only genuine certificates reflected in the system were valid for use. The whole documentation process was underpinned by strong governmental oversight which prioritized data privacy and accuracy while supporting transparent monitoring of vaccine coverage nation-wide [

6].

4.2.2. Reporting of Reactions to COVID-19 Vaccination

Following vaccination, individuals were encouraged to report any adverse reactions, ranging from common mild side effects to rare serious events. The MoH implemented a structured surveillance system supported by digital platforms, primarily the “Tarassud+” system, to collect and monitor these reports in real time. Health care providers and vaccinated individuals could submit adverse event reports through accessible online forms or through health facilities, enabling prompt documentation and analysis.

Studies conducted in Oman, such as one at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, revealed that reported adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were mostly mild, including symptoms like fever, chills, localized pain, and swelling at the injection site [

5,

20,

34,

38]. The data showed a higher prevalence of reactions reported among females compared to males, consistent with global trends. Serious adverse events were rare, but the system was designed to ensure immediate follow-up and referral for any severe or unexpected re-actions, strengthening clinical safety oversight [

38,

39]. Cutaneous reactions were also monitored carefully within specific governorates, with cases documented through prospective observational studies that aided in understanding vaccine safety at a population level. Notably, the government linked adverse event reporting with extensive public education campaigns and supreme committee weekly reports to counter misinformation and address vaccine hesitancy by transparently sharing safety data [

39,

40].

Oman’s pharmacovigilance efforts were aligned with international standards, and the digital verification of vaccination certificates integrated adverse reaction reports [

41,

42]. This comprehensive approach ensured that vaccine safety monitoring was proactive, data-driven, and responsive to emerging patterns. The transparency and systematic handling of reported reactions contributed significantly to maintaining public trust and supporting the ongoing success of the vaccination campaign during the pandemic [

11].

4.2.3. Reaching out for Foreigners (Non-Arabic Speakers)

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Oman, reaching out to foreigners, especially non-Arabic speakers, was a critical component of the national public health response aimed at ensuring inclusive communication and equitable access to health services. The “Tarassud+” application was made available not only in Arabic but also in English, Urdu, Hindi, and Bengali (the languages spoken by many expatriates living in the country) [

34]. This digital solution provided transparent, timely updates on COVID-19 cases, testing, vaccination, and public health guidelines, allowing non-Arabic speakers to access vital information in their native or preferred languages. The inclusion of multiple languages helped mitigate barriers related to language and health literacy, which could have otherwise hindered compliance with public health measures and vaccination uptake.

In addition to technology-driven approaches, Oman employed community engagement strategies involving influential figures and community leaders from diverse expatriate groups to foster trust and culturally sensitive communication. These leaders played key roles in dispelling misinformation and encouraging vaccine acceptance within their communities. Furthermore, public health messaging was carefully crafted to be culturally appropriate and disseminated through various media channels, including social media, radio, and television broadcasts, many of which were available in the languages of foreign residents. Health facilities and vaccination centers also accommodated language needs by providing multilingual staff or interpreters to assist foreigners throughout testing and vaccination procedures, ensuring clarity and confidence in the services offered.

Oman’s approach also involved coordination with foreign embassies and diplomatic missions to support multilingual communication efforts and facilitate access to health care services for their nationals. Regular updates and transparent reporting of epidemiological data were shared with these entities to build confidence and cooperation [

10,

11,

30].

4.3. Thirdly, the Health Workforce

Rapid trainings especially online and virtual platforms were put in place in vaccine administration and safety protocols, with task-shifting to non-physicians to expand capacity. To overcome burnout and shortages, PPP and support from volunteers from the retired nurses and health care workers were welcomed. Pre-emptive workforce planning and psychological support were integrated to ensure staff wellbeing [

10].

4.4. Fourthly, Health Information Systems

The “Tarassud+” digital platform served as a central repository for the comprehensive collection of COVID-19 laboratory data from both governmental and non-governmental sources on a daily basis. This system facilitated the digital tracking of confirmed, probable, and suspected cases, alongside their contacts. Utilizing this data, daily epidemiological reports for Oman were produced, guiding evidence-based interventions throughout the pandemic. Additionally, the national infection control team employed the same surveillance framework to report COVID-19 infections among HCWs and to detect healthcare-associated outbreaks. However, integrating data from non-governmental organizations and private laboratories demanded additional staffing, with a notable shortage of information technology specialists posing significant challenges to the surveillance process [

11,

34].

“Tarassud+” enabled appointment scheduling and dose tracking, while real-time dashboards monitored coverage. After the initial stage of fragmented data, lack of interoperability between government and private systems, “Tarassud+” was able to provide a comprehensive monitoring system including vaccines monitor pricing in the private sector. Integrated digital infrastructure and regular audits improved transparency with the public and built more trust towards vaccine acceptance.

Significantly, the “Tarassud+” platform was employed to register and monitor travelers concerning COVID-19 vaccination status, track adverse events related to vaccines, and issue digital health passports. Contact tracing and geofencing, implemented through electronic bracelets, were used to monitor confirmed cases, their contacts, and travelers under quarantine. However, as the number of positive cases increased, maintaining these measures became increasingly difficult. Furthermore, challenges such as inconsistent network coverage and geographical obstacles (Mountainous areas) affected the effectiveness of geofencing. Additional hurdles included the high costs associated with digital infrastructure, limited financial resources, the need for continuous IT support, and concerns around sustainability. Issues related to data security, protection of personal information, and cybersecurity also complicated the deployment of these AI tools. Moreover, gaining community acceptance for certain AI-driven interventions, such as chatbots for risk assessment and follow-up, presented a further challenge.[

9].

4.5. Fifthly, Access to Essential Medicines:

Access to essential vaccines was reached through diverse portfolio via direct purchases reduced the dependency on single suppliers. Every vaccination site had a focal point who supervised the safe handling of the vaccine and adherence to safety and cold chain protocols. The focal points were also responsible to keep records on the number of vaccines/vails used as accurate as possible. During vaccine shortages, regional and international partnerships and buffer stocks enhanced supply chain resilience [

6].

4.6. Sixthly, Financing:

As all campaign were supported through government funding as free vaccinations for citizens and residents ensured broad access. Procurement from manufacturers at premium prices strained budgets, with uncertain funding for booster doses. Sustainable financing mechanisms, such as health insurance integration maybe considered for long-term campaigns.

5. Challenges/ Limitations

The accelerated COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Oman, when assessed through the WHO health system building blocks framework (

Table 1), revealed multiple structural and operational weaknesses. Despite that the MoH maintained strong central coordination, delays in adapting policies to address emerging variants limited the system’s agility. Gaps in public communication, coupled with the spread of misinformation through false media narratives, highlighted the need for active and transparent risk communication approaches. Even with the establishment of a wide range of vaccination delivery points, disparities between rural and urban areas persisted, with remote communities experiencing slower access. Other challenges involved upholding the cold chain for mRNA vaccines and addressing localized vaccine skepticism. While rapid training and task-shifting improved the use of available human resources, the prolonged workload led to staff burnout, and rural regions continued to face shortages of trained personnel; the lack of integrated psychological support further exacerbated workforce frustrations. Digital tools such as “Tarassud+” facilitated registration and tracking, yet data fragmentation and limited interoperability with private healthcare providers reduced the comprehensiveness of reporting. Oman’s diversified vaccine procurement strategy minimized dependence on single suppliers, but global supply chain delays and regional stockouts disrupted timely distribution. Although universal, government-funded vaccination ensured equitable access, high operational costs placed pressure on budgets, and uncertainty persists regarding sustainable financing for boosters and future campaigns. Collectively, these findings highlight the need for enhanced decentralized decision-making, improved rural outreach, integrated digital health infrastructure, proactive workforce planning with mental health support, regional vaccine production partnerships, and dedicated emergency funding to enhance resilience and preparedness for future public health crises.

6. Conclusions

Oman’s accelerated COVID-19 vaccination campaign demonstrates how a well-orchestrated and timely public health response can substantially reduce the burden of a global health crisis. The campaign not only prioritized high-risk populations but also ensured equitable access across different regions, reflecting a commitment to social justice and inclusivity in health care. Central to its success was the establishment of robust governance mechanisms that coordinated multiple sectors, including governmental bodies, international partners, and civil society. The expansion of service delivery capacity, coupled with innovative use of digital technologies for monitoring vaccine distribution and data management, further enhanced efficiency and transparency. Active community engagement fostered trust and improved uptake, while integration within the framework of universal health coverage guaranteed that no group was left behind. Collectively, these strategies minimized severe cases and mortality, facilitating a phased return to social and economic stability by 2022. Such experiences underscore the importance of preparedness, equity, and global solidarity for future pandemic management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TA., and LA.; methodology, TA., and ZA.; formal analysis and validation of information in the review, TA., LA., ZA., LK., and AB.; investigation, ZA., LK., AB. and JA.; resources, TA. ; data curation TA., and LK.; writing and original draft preparation, TA., LA. and AB.; writing, review and editing, LK., ZA., AB. and JA., supervision, TA.; project administration, LA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the departments of primary health care, disease surveillance and control, nursing, and pharmaceutical and medical supplies for their support with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| EVM |

Effective Vaccine Management |

| MoH |

Ministry of Health |

| PHC |

Primary Health Care |

| HCWs |

Healthcare workers |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed July 25, 2025).

- Lives saved by COVID --19 vaccines. J Paediatrics Child Health 2022;58:2129–2129. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 advice for the public: Getting vaccinated 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Moghadas SM, Vilches TN, Zhang K, Nourbakhsh S, Sah P, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccination strategies with a delayed second dose. PLoS Biol 2021;19:e3001211. [CrossRef]

- Henry DA, Jones MA, Stehlik P, Glasziou PP. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: findings from real world studies. Med J Aust 2021;215:149-151.e1. [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri SS, Al-Rawahi B, Abdelhady D, Al-Abaidani I. Effective vaccine management and Oman’s healthcare system’s challenge to maintain high global standards. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2018;11:742–4. [CrossRef]

- Al Wahaibi A, Al Rawahi B, Patel PK, Al Khalili S, Al Maani A, Al-Abri S. COVID-19 disease severity and mortality determinants: A large population-based analysis in Oman. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2021;39:101923. [CrossRef]

- Medical Xpress. Oman launches COVID-19 vaccination campaign 2020.

- Al Khalili S, Al Maani A, Al Wahaibi A, Al Yaquobi F, Al-Jardani A, Al Harthi K, et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Public Health Service in Oman From the COVID-19 Pandemic: Learning Lessons for a Better Future. Front Public Health 2021;9:770946. [CrossRef]

- Al Ghafri T, Al Ajmi F, Anwar H, Al Balushi L, Al Balushi Z, Al Fahdi F, et al. The Experiences and Perceptions of Health-Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Muscat, Oman: A Qualitative Study. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:2150132720967514. [CrossRef]

- Al Lamki S, Aal Jumaa I, Al Ghafri M, Al Abri Z. Oman: a primary health care case study in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Health Organization 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376136/9789240088603-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed July 25, 2025).

- Al Rawahi B, Al Wahaibi A, Al Khalili S, Al Balushi AYM, Al-Shehi N, Al Harthi K, et al. The impact of the acceleration of COVID-19 vaccine deployment in two border regions in Oman. IJID Regions 2022;3:265–7. [CrossRef]

- Reuters research. COVID-19 Tracker. Reuters COVID-19 Tracker 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/graphics/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/oman/ (accessed May 22, 2025).

- Al Wahaibi A, Al-Maani A, Alyaquobi F, Al Harthy K, Al-Jardani A, Al Rawahi B, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on mortality: A 5-year population-based study in Oman. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021;104:102–7. [CrossRef]

- Khamis F, Al Rashidi B, Al-Zakwani I, Al Wahaibi AH, Al Awaidy ST. Epidemiology of COVID-19 Infection in Oman: Analysis of the First 1304 Cases. Oman Med J 2020;35:e145–e145. [CrossRef]

- Mansour S, Alahmadi M, Mahmoud A, Al-Shamli K, Alhabsi M, Ali W. Geospatial modelling of COVID19 mortality in Oman using geographically weighted Poisson regression GWPR. Sci Rep 2025;15:8138. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes-WHO’s Framework for Action. World Health Organization 2007.

- Frenk J. The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems as the Next Step for Global Progress. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000089. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. MONITORING THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF HEALTH SYSTEMS: A HANDBOOK OF INDICATORS AND THEIR MEASUREMENT STRATEGIES. World Health Organization 2020. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf (accessed July 25, 2025).

- Al Ghafri TS, Al Balushi L, Al Balushi Z, Al Hinai F, Al Hasani S, Anwar H, et al. Reporting at Least One Adverse Effect Post-COVID-19 Vaccination From Primary Health Care in Muscat. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Naik S, Vr S, Mohakud S, Tripathy T. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Adverse Drug Reactions Reported Among Sultan Qaboos University Hospital Staff. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2024;24:216–20. [CrossRef]

- Hasani SA, Ghafri TA, Al Lawati H, Mohammed J, Al Mukhainai A, Al Ajmi F, et al. The Use of Telephone Consultation in Primary Health Care During COVID-19 Pandemic, Oman: Perceptions from Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:2150132720976480. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO collaboration in Oman’s response to COVID-19 2025. https://www.emro.who.int/omn/oman-news/who-collaboration-on-omans-response-to-covid-19.html (accessed July 25, 2025).

- BADR AL SAMAA GROUP OF HOSPITALS & MEDICAL CENTRES. BADR AL SAMAA COMPLETES COVID-19 VACCINATION DRIVE AT NATIONAL MUSEUM 2021. https://al-khoud.badralsamaahospitals.com/news-and-event/67/badr-al-samaa-completes-covid-19-vaccination-drive-at-national-museum?page=9 (accessed July 25, 2025).

- The Arabian Stories. COVID-19 vaccine: Private sector firms in Oman encourage staff to get jab 2021. https://www.thearabianstories.com/2021/05/18/covid-19-vaccine-private-sector-firms-in-oman-encourage-staff-to-get-jab/ (accessed July 25, 2025).

- Arabnews. Oman vaccinates almost 2 million people against COVID-19 2021. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1900826/middle-east (accessed July 25, 2025).

- OERLive. Occidental Oman Contributes $2.5 Million Towards COVID Vaccine Procurement 2021.

- Observer Oman Daily. Oman LNG earmarks RO6 million for COVID-19, Job Security 2020.

- Observer Oman Daily. OCCI donates RO 2 million for job fund, COVID-19 2020.

- Al Awaidy ST, Khatiwada M, Castillo S, Al Siyabi H, Al Siyabi A, Al Mukhaini S, et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccine in Oman: A Cross-sectional Study. Oman Med J 2022;37:e380. [CrossRef]

- Al Awaidy S, Khamis F, Al Ghafri T, Badahdah A. Support for Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccines for 5- to 11-Year-Old Children: Cross-sectional study of Omani mothers. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2024;24:229–34. [CrossRef]

- Al Siyabi H, Al Mukhaini S, Kanaan M, Al Hatmi S, Al Anqoudi Z, Al Kalbani A, et al. Community Participation Approaches for Effective National COVID-19 Pandemic Preparedness and Response: An Experience From Oman. Front Public Health 2021;8:616763. [CrossRef]

- Samhouri D, Aynsley TR, Hanna P, Frost M, Houssiere V. Risk communication and community engagement capacity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a call for action. BMJ Glob Health 2024;7:e008652. [CrossRef]

- Al Manji A, Tahoun M, Chi Amabo F, Alabri M, Mahmoud L, Al Abri B, et al. Contact tracing in the context of COVID-19: a case study from Oman. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e008724. [CrossRef]

- Khamis F, Al Mahyijari N, Al Lawati F, Badahdah AM. The Mental Health of Female Physicians and Nurses in Oman during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Oman Med J 2020;35:e203–e203. [CrossRef]

- Large turnout as mass vaccination gets underway at OCEC. Vaccination Campaign at OCEC 2021.

- Mughal F, Khunti K, Mallen CD. The impact of COVID-19 on primary care: Insights from the National Health Service (NHS) and future recommendations. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2021;10:4345–9. [CrossRef]

- Naik S, Vr S, Mohakud S, Tripathy T. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Adverse Drug Reactions Reported Among Sultan Qaboos University Hospital Staff. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2024;24:216–20. [CrossRef]

- Said EA, Al-Rubkhi A, Jaju S, Koh CY, Al-Balushi MS, Al-Naamani K, et al. Association of the Magnitude of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Side Effects with Sex, Allergy History, Chronic Diseases, Medication Intake, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Vaccines 2024;12:104. [CrossRef]

- Al Busaidi BH, Al Riyami IM, Wazir HB, Al Zakwani IS. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Adverse Drug Reactions Reported Among Sultan Qaboos University Hospital Staff. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2024;24:216–20. [CrossRef]

- Jose J, Rubaie MHA, Ramimy HA, Varughese SS. Pharmacovigilance. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2021;21:e161-163. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph A, Mitchell J, Barrett J, Sköld H, Taavola H, Erlanson N, et al. Global safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccines: how pharmacovigilance rose to the challenge. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety 2022;13:20420986221118972. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).