Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Urine Sample Collection and USC Isolation

Flow Cytometry Analysis for MSC and HSC Markers

Generation of Urine-Derived iPSCs (u-iPSCs)

Immunofluorescent Staining for Sendai Virus Components and Pluripotency Markers

Characterization of u-iPSCs Pluripotency

Differentiation of u-iPSCs into RPE Cells (u-iPSC-RPE cells)

Characterization of u-iPSC-RPE Cells

3. Results

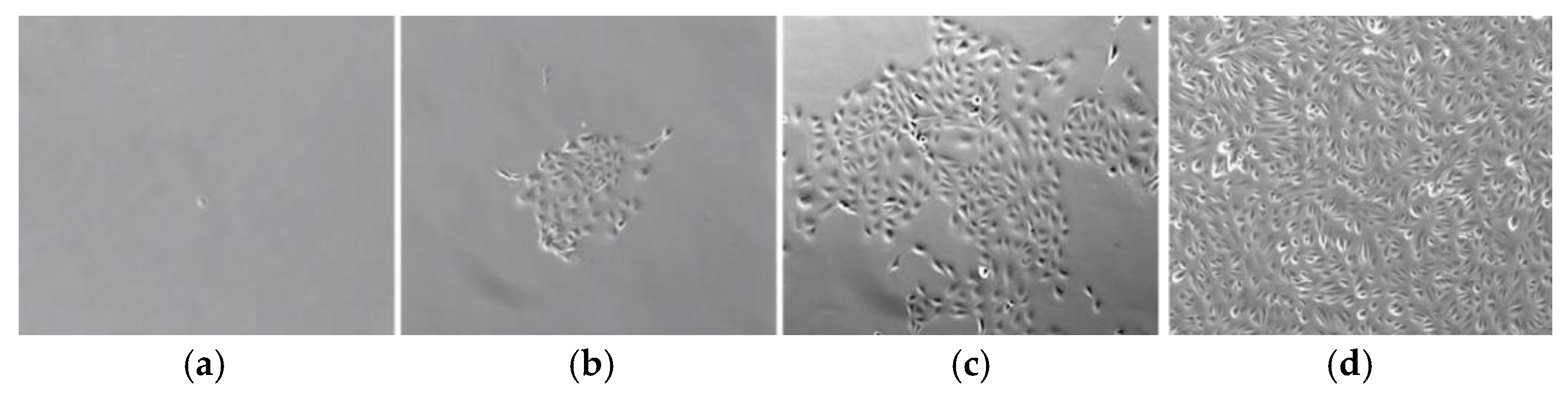

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Urine-Derived Stem Cells

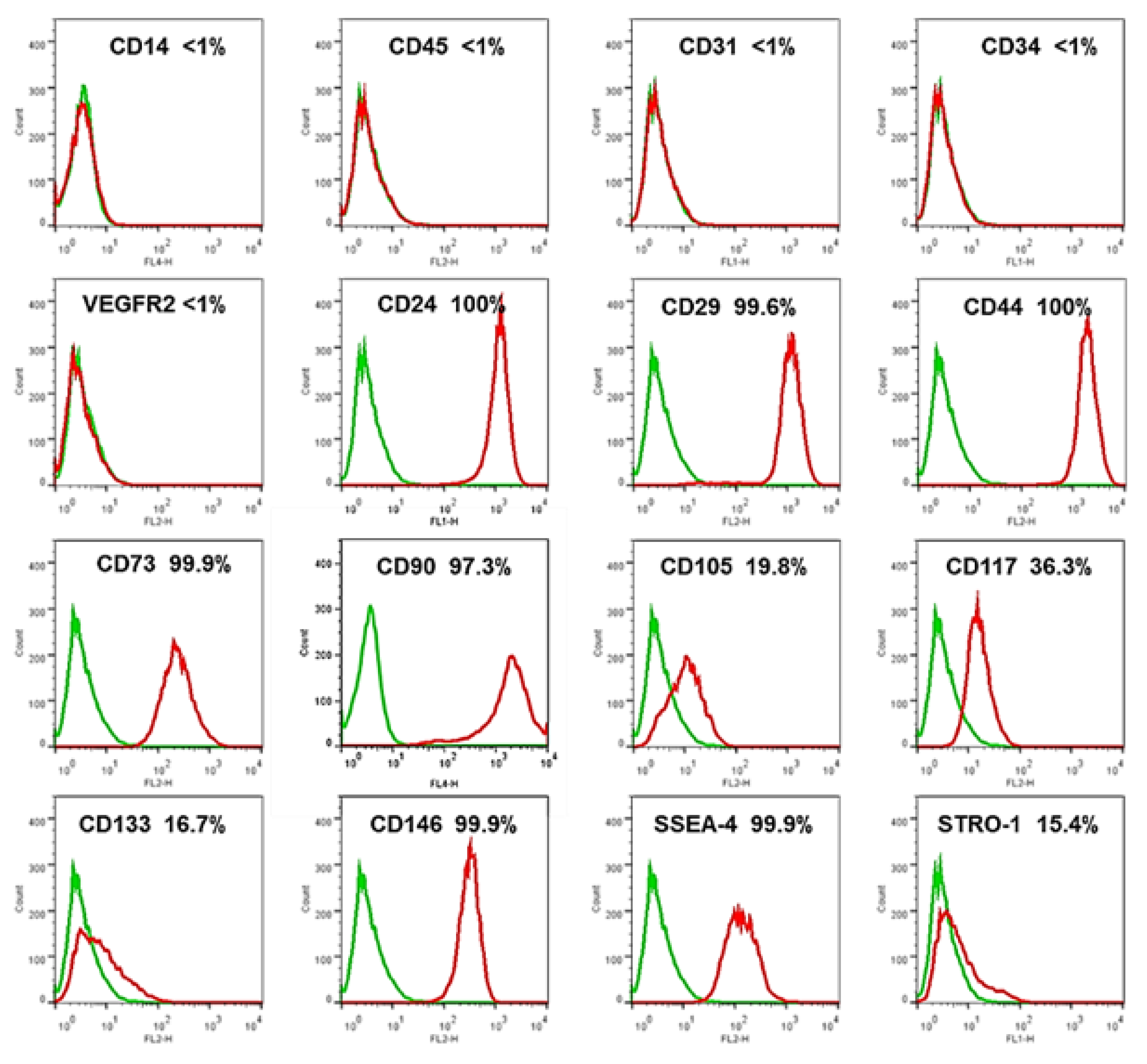

3.2. Phenotypic Characterization of USCs by Flow Cytometry

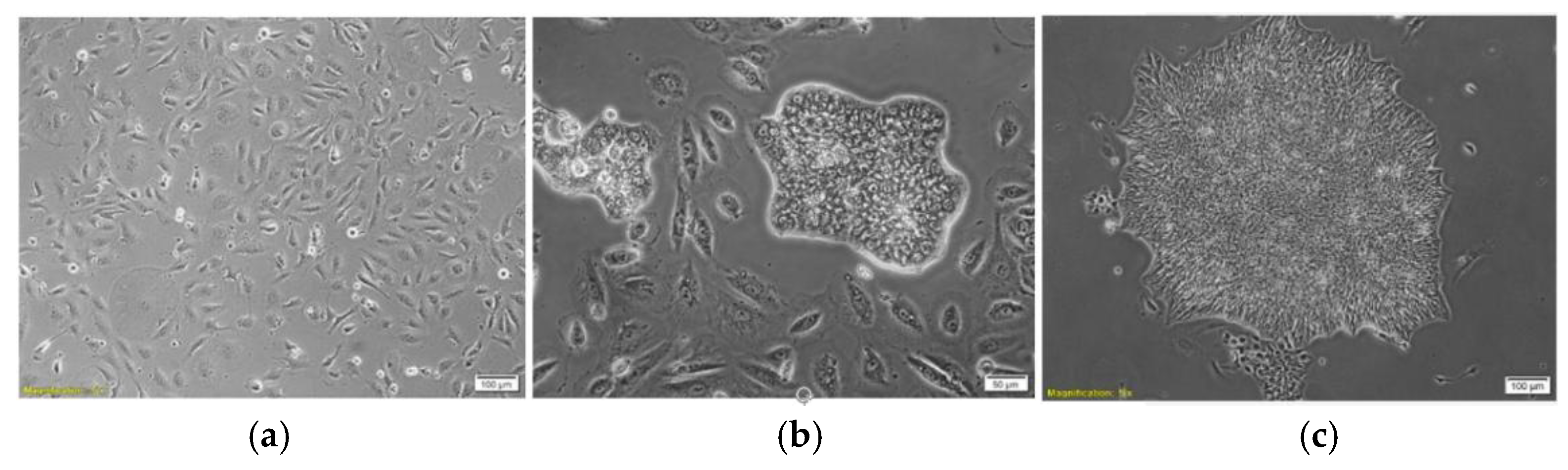

3.3. Morphology of Urine-Derived iPSC Colonies

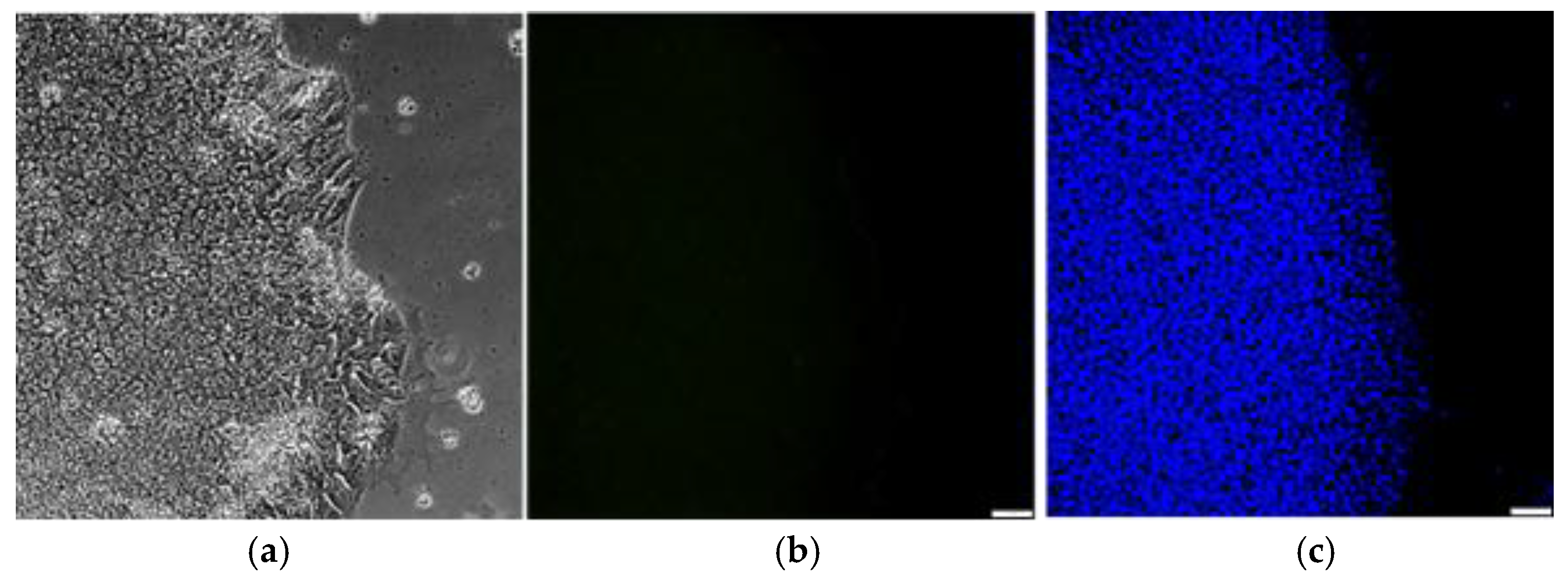

3.4. Monitoring the Clearance of Sendai Viral Components in Reprogrammed u-iPSCs

3.5. Generation and Characterization of u-iPSCs

3.6. Differentiation and Initial Characterization of u-iPSC-Derived RPE Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | Age-Related Macular Degeneration |

| USC | Urine-Derived Stem Cells |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| RPE | Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| PEC | Parietal Epithelial Cells |

| SeV | Sendai Virus |

| EB | Embryoid Body |

| DIM | Differentiation Induction Media |

| DPM | Differentiation Propagation Media |

| RPEMM | Retinal Pigment Epithelium Maturation Media |

References

- Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K. The Prevalence of Age-Related Eye Diseases and Visual Impairment in Aging: Current Estimates. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, ORSF5–ORSF13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group*, T.E.D.P.R. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the United States. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004, 122, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, C.M.; Zouache, M.A.; Matthews, S.; Faust, C.D.; Hageman, J.L.; Williams, B.L.; Richards, B.T.; Hageman, G.S. Protective chromosome 1q32 haplotypes mitigate risk for age-related macular degeneration associated with the CFH-CFHR5 and ARMS2/HTRA1 loci. Hum. Genom. 2021, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2014, 2, e106–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, M.C.; Geng, Z.; Stahl, M.R.; Kapphahn, R.J.; Roehrich, H.; Montezuma, S.R.; Ferrington, D.A.; Dutton, J.R. Testing Mitochondrial-Targeted Drugs in iPSC-RPE from Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandai, M.; Watanabe, A.; Kurimoto, Y.; Hirami, Y.; Morinaga, C.; Daimon, T.; Fujihara, M.; Akimaru, H.; Sakai, N.; Shibata, Y.; Terada, M.; Nomiya, Y.; Tanishima, S.; Nakamura, M.; Kamao, H.; Sugita, S.; Onishi, A.; Ito, T.; Fujita, K.; Kawamata, S.; Go, M.J.; Shinohara, C.; Hata K-i Sawada, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Ohta, S.; Ohara, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Kuwahara, J.; Kitano, Y.; Amano, N.; Umekage, M.; Kitaoka, F.; Tanaka, A.; Okada, C.; Takasu, N.; Ogawa, S.; Yamanaka, S.; Takahashi, M. Autologous Induced Stem-Cell–Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran Nair, D.S.; Zhu, D.; Sharma, R.; Martinez Camarillo, J.C.; Bharti, K.; Hinton, D.R.; Humayun, M.S.; Thomas, B.B. Long-Term Transplant Effects of iPSC-RPE Monolayer in Immunodeficient RCS Rats. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Khristov, V.; Rising, A.; Jha, B.S.; Dejene, R.; Hotaling, N.; Li, Y.; Stoddard, J.; Stankewicz, C.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Campos, M.M.; Miyagishima, K.J.; McGaughey, D.; Villasmil, R.; Mattapallil, M.; Stanzel, B.; Qian, H.; Wong, W.; Chase, L.; Charles, S.; McGill, T.; Miller, S.; Maminishkis, A.; Amaral, J.; Bharti, K. Clinical-grade stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch rescues retinal degeneration in rodents and pigs. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Yin, J.; Huo, W.; Chaum, E. Modeling of mitochondrial bioenergetics and autophagy impairment in MELAS-mutant iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; David, B.T.; Trawczynski, M.; Fessler, R.G. Advances in Pluripotent Stem Cells: History, Mechanisms, Technologies, and Applications. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2020, 16, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboutaleb Kadkhodaeian, H.; Tiraihi, T.; Ahmadieh, H.; Ziaei, H.; Daftarian, N.; Taheri, T. Generation of Retinal Pigmented Epithelium-Like Cells from Pigmented Spheres Differentiated from Bone Marrow Stromal Cell-Derived Neurospheres. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019, 16, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Elefanty, A.; Stanley, E.G.; Durnall, J.C.; Thompson, L.H.; Elwood, N.J. Creation of GMP-Compliant iPSCs From Banked Umbilical Cord Blood. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 835321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Hamada, Y.; Horiuchi, Y.; Matsuo-Takasaki, M.; Imoto, Y.; Satomi, K.; Arinami, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Fujioka, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Noguchi, E. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human nasal epithelial cells using a Sendai virus vector. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Walsh, P.J.; Truong, V.; Hill, C.; Ebeling, M.; Kapphahn, R.J.; Montezuma, S.R.; Yuan, C.; Roehrich, H.; Ferrington, D.A.; Dutton, J.R. Generation of retinal pigmented epithelium from iPSCs derived from the conjunctiva of donors with and without age related macular degeneration. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0173575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.R.; Ebeling, M.C.; Geng, Z.; Kapphahn, R.J.; Roehrich, H.; Montezuma, S.R.; Dutton, J.R.; Ferrington, D.A. Human iPSC- and Primary-Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells for Modeling Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; McNeill, E.; Tian, H.; Soker, S.; Andersson, K.-E.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. Urine Derived Cells are a Potential Source for Urological Tissue Reconstruction. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 2226–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.L.; Li, Q.; Ma, J.X.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Body fluid-derived stem cells - an untapped stem cell source in genitourinary regeneration. Nat Rev Urol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Bosholm, C.C.; Zhu, H.; Duan, Z.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Beyond waste: understanding urine’s potential in precision medicine. Trends Biotechnol 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Mack, D.L.; Moreno, C.M.; Strande, J.L.; Mathieu, J.; Shi, Y.; Markert, C.D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Lawlor, M.W.; Moorefield, E.C.; Jones, T.N.; Fugate, J.A.; Furth, M.E.; Murry, C.E.; Ruohola-Baker, H.; Zhang, Y.; Santana, L.F.; Childers, M.K. Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes derived from human urine: new biologic reagents for drug discovery. Stem Cell Res 2014, 12, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, S.; Xue, H.; Schmitt, K.; Hergenroeder, G.W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Cao, Q. Human neural progenitors derived from integration-free iPSCs for SCI therapy. Stem Cell Res 2017, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Benda, C.; Dunzinger, S.; Huang, Y.; Ho, J.C.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Li, Y.; Bao, X.; Tse, H.F.; Grillari, J.; Grillari-Voglauer, R.; Pei, D.; Esteban, M.A. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat Protoc 2012, 7, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Benda, C.; Duzinger, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Cao, G.; Chen, S.; Hao, L.; Chan, Y.C.; Ng, K.M.; Ho, J.C.; Wieser, M.; Wu, J.; Redl, H.; Tse, H.F.; Grillari, J.; Grillari-Voglauer, R.; Pei, D.; Esteban, M.A. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011, 22, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Markert, C.; Andersson, K.E.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of urine-derived stem cells obtained from upper urinary tract for use in cell-based urological tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 2011, 17, 2123–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; He, T.; Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Atala, A.; Rohozinski, J.; Zhang, Y. Multipotential differentiation of human urine-derived stem cells: potential for therapeutic applications in urology. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1840–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, G.; Li, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Urine-derived stem cells: A novel and versatile progenitor source for cell-based therapy and regenerative medicine. Genes Dis. 2014, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Sun, B.; Ding, G.; Hu, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Beneficial effects of urine-derived stem cells on fibrosis and apoptosis of myocardial, glomerular and bladder cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2016, 427, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Deng, N.; Dou, L.; Ding, H.; Criswell, T.; Atala, A.; Furdui, C.M.; Zhang, Y. 3-D Human Renal Tubular Organoids Generated from Urine-Derived Stem Cells for Nephrotoxicity Screening. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, W.; Han, D.; Zhang, C.; Xie, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, G.; Deng, C. Intratunical injection of human urine-derived stem cells derived exosomes prevents fibrosis and improves erectile function in a rat model of Peyronie’s disease. Andrologia 2020, e13831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, X.-R.; Liu, H.-S.; Liu, X.-H.; Liu, G.-H.; Zheng, X.-B.; Hu, T.; Liang, Z.-X.; He, X.-W.; Wu, X.-J.; Smith, L.C.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, P. Immunomodulatory Effect of Urine-derived Stem Cells on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases via Downregulating Th1/Th17 Immune Responses in a PGE2-dependent Manner. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 14, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; Shi, Y.; Deng, C.; Atala, A.; Mou, S.; Criswell, T.; Zhang, Y. A cocktail of growth factors released from a heparin hyaluronic-acid hydrogel promotes the myogenic potential of human urine-derived stem cells in vivo. Acta Biomater 2020, 107, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zheng, T.; Han, D.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Bian, J.; Sun, X.; Xia, K.; Liang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, C. Transplantation of Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells Transfected with Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor to Protect Erectile Function in a Rat Model of Cavernous Nerve Injury. Cell Transpl. 2016, 25, 1987–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Tao, L.; Ma, W.J.; Gong, M.J.; Zhao, L.; Shen, L.J.; Long, C.L.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wei, G.H. Urine-derived stem cells for the therapy of diabetic nephropathy mouse model. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Luo, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Dong, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Therapeutic Effects of Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells in a Rat Model of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury In Vivo and In Vitro. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 8035076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, Q.; Niu, X.; Zhang, G.; Ling, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Z. Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells Promote Ischemia Repair in a Mouse Model of Hind-Limb Ischemia. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 47, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, H.; Bharadwaj, S.; Liu, Y.; Hodges, S.; Atala, A. Urine-derived stem cells for urological injection therapy. J. Urol. 2009, 181, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Bioglass enhanced wound healing ability of urine-derived stem cells through promoting paracrine effects between stem cells and recipient cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2018, 12, e1609–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; George, S.K.; Wu, R.; Thakker, P.U.; Abolbashari, M.; Kim, T.-H.; Ko, I.K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jackson, J.; Lee, S.J.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. Reno-protection of Urine-derived Stem Cells in A Chronic Kidney Disease Rat Model Induced by Renal Ischemia and Nephrotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, B.; Deng, J.; Zhuang, G.; Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Deng, C.; Yang, G.; Qiu, X.; Wei, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of rabbit urine-derived stem cells for potential application in lower urinary tract tissue regeneration. Cell Tissue Res 2018, 374, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Bharadwaj, S.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Human urine-derived stem cells seeded in a modified 3D porous small intestinal submucosa scaffold for urethral tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Bharadwaj, S.; Hoagie, S.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. 181 CELL THERAPY WITH AUTOLOGOUS URINE-DERIVED STEM CELLS FOR VESICOURETERAL REFLUX. J. Urol. 2011, 185, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.P.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.A.; Bharadwaj, S.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Human urine-derived stem cells originate from parietal stem cells. J Urol 2014, 191, e1–e958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Xiong, G.; Liu, G.; Shupe, T.D.; Wei, G.; Zhang, D.; Liang, D.; Lu, X.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Urothelium with barrier function differentiated from human urine-derived stem cells for potential use in urinary tract reconstruction. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran CT, A.; Yi, H.; Balog, B.; Zhang, Y.; Damaser, M. : Human urine-derived stem cells or their secretome alone facilitate functional recovery in a rat model of stress urinary incontinence. Journal of Urology 2016, 195, No. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran CNT, A.; Balog, B.; Zhang, Y.; Damaser, M. Paracrine Effects of Human Urine-derived Stem Cells in Treatment of Female Stress Urinary Incontinence in a Rodent Model. Tissue Eng Part A 2015, 21, S-385. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H.; Zhu, C.; An, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Hui, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Silver nanoparticles promote osteogenic differentiation of human urine-derived stem cells at noncytotoxic concentrations. Int J Nanomed. 2014, 9, 2469–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Long, T.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y. Urine-derived stem cells for potential use in bladder repair. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, B.; Sun, X.; Han, D.; Chen, S.; Yao, B.; Gao, Y.; Bian, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, Z.; Yang, B.; Xiao, H.; Songyang, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, C. Human urine-derived stem cells alone or genetically-modified with FGF2 Improve type 2 diabetic erectile dysfunction in a rat model. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Pareta, R.A.; Wu, R.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Deng, C.; Sun, X.; Atala, A.; Opara, E.C.; Zhang, Y. Skeletal myogenic differentiation of urine-derived stem cells and angiogenesis using microbeads loaded with growth factors. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long TJ, Y.D.; Shi, H.; Zhong, L.R.; Zhang, D.Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiao, Y.; Diz, D.; Zhang, Y. : Human urine-derived stem cells lessen inflammation and fibrosis within kidney tissue in a rodent model of aging-related renal insufficiency. J Urol 2017, 197, e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Zhang, G.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Niu, X.; Hu, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Z. Exosomes from human urine-derived stem cells enhanced neurogenesis via miR-26a/HDAC6 axis after ischaemic stroke. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Luo, H.; Dong, X.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhang, T.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, B.; Li, L. Therapeutic effect of urine-derived stem cells for protamine/lipopolysaccharide-induced interstitial cystitis in a rat model. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Bharadwaj, S.; Leng, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Self-renewal and differentiation capacity of urine-derived stem cells after urine preservation for 24 hours. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chang, J. Human urine-derived stem cells can be induced into osteogenic lineage by silicate bioceramics via activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Biomaterials 2015, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Guan, J.; Guo, S.; Guo, F.; Niu, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Nie, H.; Wang, Y. Human urine-derived stem cells in combination with polycaprolactone/gelatin nanofibrous membranes enhance wound healing by promoting angiogenesis. J Transl Med 2014, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, A.; Bharadwaj, S.; Wu, S.; Gatenholm, P.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Tissue-engineered conduit using urine-derived stem cells seeded bacterial cellulose polymer in urinary reconstruction and diversion. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8889–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagrinati, C.; Netti, G.S.; Mazzinghi, B.; Lazzeri, E.; Liotta, F.; Frosali, F.; Ronconi, E.; Meini, C.; Gacci, M.; Squecco, R.; Carini, M.; Gesualdo, L.; Francini, F.; Maggi, E.; Annunziato, F.; Lasagni, L.; Serio, M.; Romagnani, S.; Romagnani, P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 17, 2443–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Somji, S.; Sens, D.A.; Slusser-Nore, A.; Patel, D.H.; Savage, E.; Garrett, S.H. Human renal tubular cells contain CD24/CD133 progenitor cell populations: Implications for tubular regeneration after toxicant induced damage using cadmium as a model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 331, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kong, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhou, L. Stem/progenitor cell in kidney: characteristics, homing, coordination, and maintenance. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Marsoummi, S.; Singhal, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Somji, S.; Sens, D.A.; Singhal, S.K. CD133+CD24+ Renal Tubular Progenitor Cells Drive Hypoxic Injury Recovery via Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1A and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Expression. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, H.; Soundararajan, L.; Reddy, K.V.; Subramani, J.; Stoddard, J.; Reynaga, R.; Tschetter, W.; Ryals, R.C.; Pal, R. An improved protocol for generation and characterization of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells. STAR Protoc 2022, 3, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, L.; Yuan, C.; Wu, X. The recruitment mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets of podocytes from parietal epithelial cells. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [62] Hong, X.; Nie, H.; Deng, J.; Liang, S.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Gong, S.; Wang, G.; Zuo, W.; Hou, F.; Zhang, F. WT1(+) glomerular parietal epithelial progenitors promote renal proximal tubule regeneration after severe acute kidney injury. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, R.; Pace, J.; Gowthaman, Y.; Salant, D.J.; Mallipattu, S.K. Podocyte-Parietal Epithelial Cell Interdependence in Glomerular Development and Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2023, 34, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agati, V.D.; Shankland, S.J. Recognizing diversity in parietal epithelial cells. Kidney Int 2019, 96, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, E.; Sagrinati, C.; Angelotti, M.L.; Lazzeri, E.; Mazzinghi, B.; Ballerini, L.; Parente, E.; Becherucci, F.; Gacci, M.; Carini, M. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. : JASN 2009, 20, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, C.; Ho, J.; Sims-Lucas, S. Embryonic Development of the Kidney. Pediatric Nephrology. Edited by Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N, Emma F, Goldstein SL. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016. pp. 3–36.

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Mack, D.L.; Sun, X.S.; Maxwell, J.; Guan, X.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Differentiation Capacity of Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells to Retain Telomerase Activity. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 890574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Xiong, G.; Liu, G.; Shupe, T.D.; Wei, G.; Zhang, D.; Liang, D.; Lu, X.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Urothelium with barrier function differentiated from human urine-derived stem cells for potential use in urinary tract reconstruction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, Q.; McNutt, P.M.; Zhang, Y. Urine-Derived Stem Cells for Epithelial Tissues Reconstruction and Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C.; Xie, H. Urine-derived stem cells: applications in skin, bone and articular cartilage repair. Burns Trauma 2021, 9, tkab039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; Deng, C.; Lu, X.; Walker, S.J.; Ma, P.X.; Mou, S.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Human Urine-Derived Stem Cell Differentiation to Endothelial Cells with Barrier Function and Nitric Oxide Production. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Chen, G.; Qiu, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Lin, G.; Criswell, T.; Zhang, Y. Urine-derived stem cells genetically modified with IGF1 improve muscle regeneration. Am J Clin Exp Urol 2024, 12, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Zhu, Y.; Kim, M.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Collins, C.P.; Mei, O.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, C.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; You, W.; Shen, G.; Luo, C.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Shu, Y.; Luu, H.H.; Haydon, R.C.; Lee, M.J.; Shi, L.L.; Huang, W.; Fan, J.; Sun, C.; Wen, L.; Ameer, G.A.; He, T.C.; Reid, R.R. Effective Bone Tissue Fabrication Using 3D-Printed Citrate-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds Laden with BMP9-Stimulated Human Urine Stem Cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025, 17, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Xing, F.; Zou, M.; Gong, M.; Li, L.; Xiang, Z. Comparison of chondrogenesis-related biological behaviors between human urine-derived stem cells and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from the same individual. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliña-Sánchez, C.; Aguilera, Y.; Adán, N.; Sierra-Párraga, J.M.; Olmedo-Moreno, L.; Panadero-Morón, C.; Cabello-Laureano, R.; Márquez-Vega, C.; Martín-Montalvo, A.; Capilla-González, V. Generation of mesenchymal stromal cells from urine-derived iPSCs of pediatric brain tumor patients. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1022676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woogeng, I.N.; Kaczkowski, B.; Abugessaisa, I.; Hu, H.; Tachibana, A.; Sahara, Y.; Hon, C.-C.; Hasegawa, A.; Sakai, N.; Nishida, M.; Sanyal, H.; Sho, J.; Kajita, K.; Kasukawa, T.; Takasato, M.; Carninci, P.; Maeda, A.; Mandai, M.; Arner, E.; Takahashi, M.; Kime, C. Inducing human retinal pigment epithelium-like cells from somatic tissue. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 17, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).