1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Cervical lymphadenopathy is a common condition in children, affecting up to 90% of those aged 4-8 years [

1]. The most frequent cause is reactive hyperplasia due to viral infections, followed by bacterial infections and, rarely, malignancies [

2]. Acute bilateral cases are typically caused by viral upper respiratory infections or streptococcal pharyngitis, while acute unilateral cases are often due to streptococcal or staphylococcal infections [

3]. Subacute or chronic cases may result from cat scratch disease, mycobacterial infection, or toxoplasmosis [

3]. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy in children is particularly concerning, as it is more frequently linked to malignancy than anterior cervical lymphadenopathy [

4].

The diagnostic approach includes clinical evaluation, laboratory investigations, and imaging studies, with ultrasonography increasingly used for initial assessment [

5]. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may aid diagnosis, but in cases of persistent lymphadenopathy, excisional biopsy is often required, as histological examination remains the gold standard [

6].

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD), also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a rare, benign, and self-limiting disorder characterized by subacute necrotizing lymphadenopathy, most commonly in the cervical region. While it primarily affects young adult women, it can also occur in children, in whom the clinical features may differ [

7]. In pediatric cases, males may be more frequently affected than females, contrary to the adult pattern. Fever, rash, and tender lymphadenopathy are more pronounced in children, with leukopenia commonly reported in both age groups [

7]. KFD can mimic other serious conditions such as tuberculosis or lymphoma, making early diagnosis crucial.

Although the etiology remains unclear, both infectious and autoimmune mechanisms have been proposed [

8]. Diagnosis is established histologically, with findings including paracortical areas of apoptotic necrosis, karyorrhectic debris, and proliferation of histiocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and CD8+ T lymphocytes [

8]. KFD must be carefully distinguished from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, both clinically and histopathologically [

9].

We report a rare case of KFD in a 14-year-old girl who presented with prolonged cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy—a highly unusual manifestation in children. To our knowledge, this is the first documented pediatric case presenting with supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, a particularly exceptional feature even in adult cases.

2. Case Presentation

A previously healthy 14-year-old girl was admitted to the Pediatric Department of the University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece, due to a one-month history of cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy predominately on the left side. Twenty days before admission, she presented with fever max 39 °C every six hours for ten days and every twelve hours for the last ten days, weight loss of almost 5 kg, fatigue and transient pain in both hip joints. Her previous history was unremarkable, and from her family history, her mother has a probable diagnosis for SEL at the age of 30 in USA; however, in the last 10 years, she has been asymptomatic without treatment.

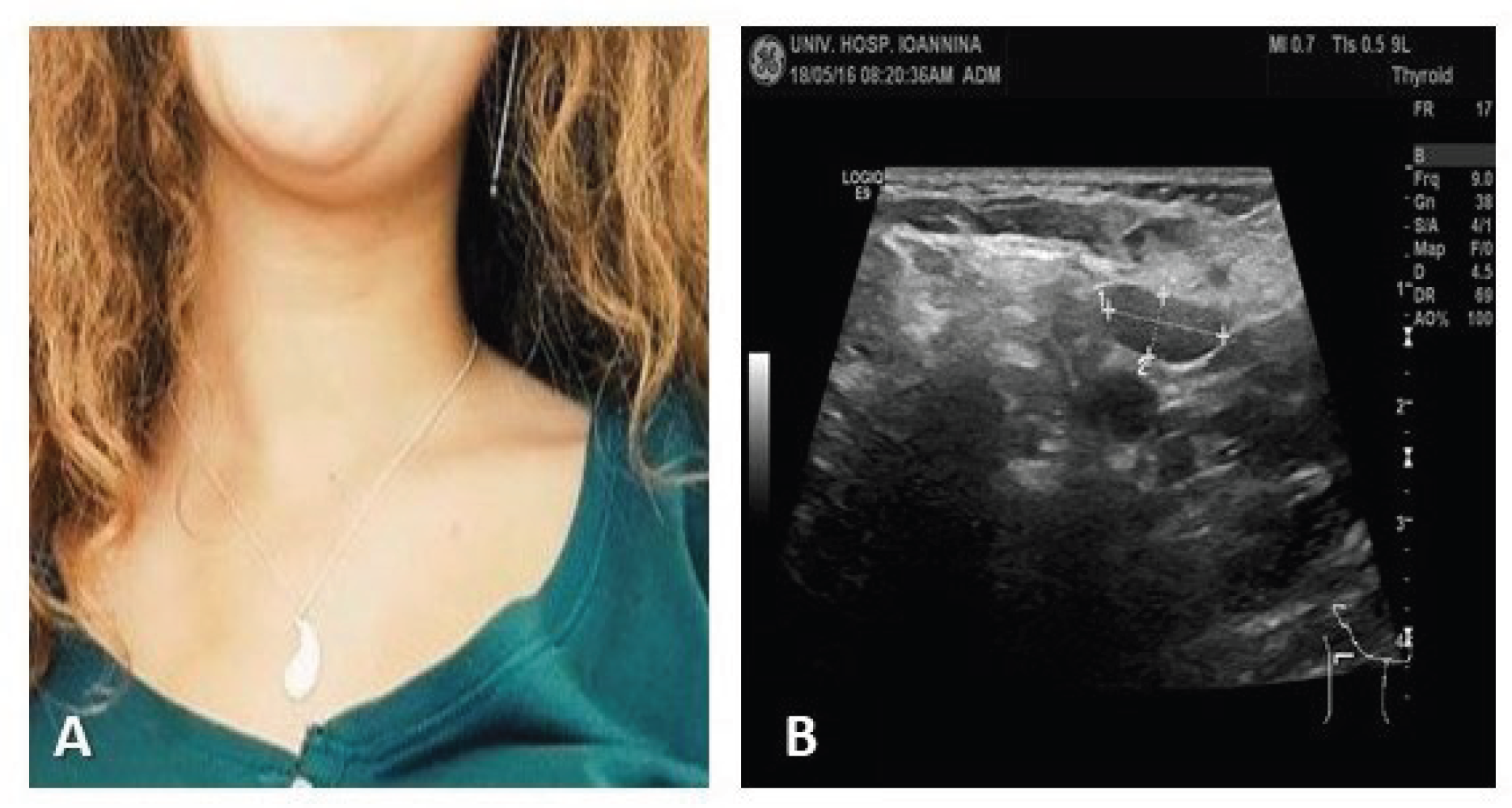

On physical examination, she had fever 38.5°C, she was quite pale but in good general condition; lymphadenopathy was identified in inspection (

Figure 1) of cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes. In palpation: lateral cervical lymph nodes, the largest ~3 cm, hard, mobile and moderately painful. The smaller lymph nodes were mobile and painless. The supraclavicular lymph nodes both mainly on the right, painless on palpation, non-mobile, hard; the small axillary nodes were barely palpable. Other lymph node groups were not palpable. Examination of the other systems was unremarkable, and the abdomen was without organomegaly.

Laboratory tests revealed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate ESR 29 mm/h normal range (NR): 0-20mm/h] and a borderline hemoglobin level for the patient’s age and sex (12.8 g/dL, NR: 12.4-16.4g/dL), with no leukocytosis, elevated inflammatory markers or other abnormal findings. An abdominal ultrasound performed in our Department showed findings consistent with previous imaging. Additionally, an abdominal MRI confirmed the presence of multiple splenic nodules with signal intensity equal to that of the splenic parenchyma, of unknown origin (

Figure 1).

Considering the wide range of potential etiologies for peripheral lymphadenopathy and fever of unknown origin, a thorough panel of laboratory tests were conducted to investigate the most likely etiologies. Specifically, the following tests were conducted to investigate infectious agents: blood cultures, urine cultures, stool cultures, serological testing for viruses (EBV IgM (-), IgG (+)23U/ml, Mono test (-), CMV IgM (-), IgG(-), HIV (-), Adenovirus IgM(-) IgG(-), Influenza (-), HIV, ADV ), bacteria Brucella IgM(-), IgG(-); Rose Bengal (-), wright (-); Leismania (-); ASTO 25IU/ml; Mycoplasma IgM (-), IgG(-); Bartonella IgM (-), IgG (-);Mycobacterium tuberculosis) Mantoux (-) Quantiferon (-), parasites Toxoplasma IgM(-) IgG(-), a bone marrow aspiration for morphology and culture was normal.Additional tests were conducted to rule out other possible causes, including measurement of immunoglobulins, ACE 60 U/L (NR 6-89) levels, as well as anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies ANCA (-), both p-ANCA (-) and c-ANCA(-), ANA 1/160 U/ml), Anticardiolipin IgG 6.08 GPL/ml (negative <12) IgM 7.47 MPL/ml (negative <12), Lupus R(-), IgG 1250 mg/dl, IgM 182 mg/dl, RF(-), IgE 139 U/ml , IgA 234 mg/dl, C3 86 mg/dl, C4 25,8 mg/dl. Protein electrophoresis: normal

Ophthalmological assessment (anterior particles): normal

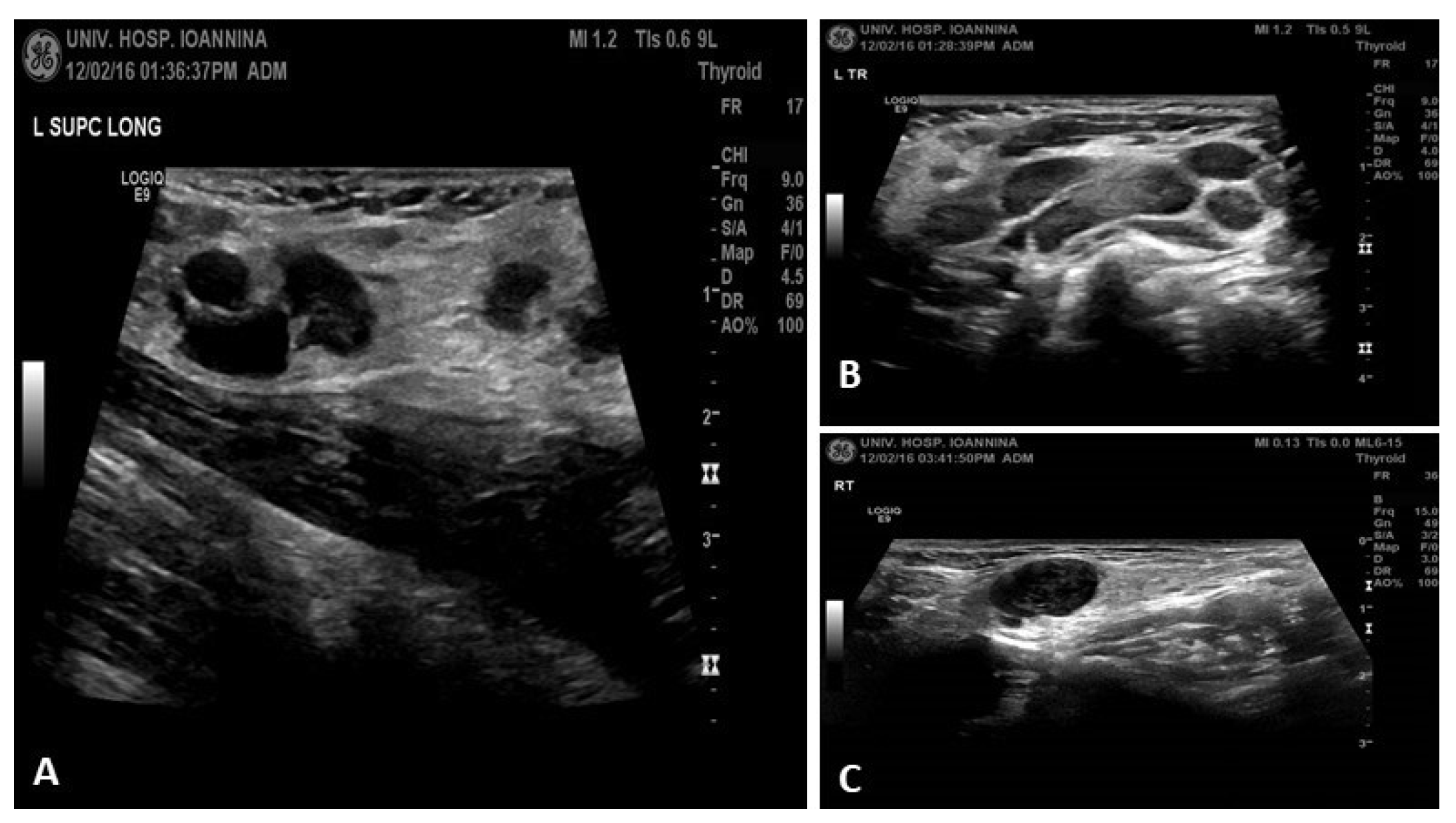

Ultrasound: revealed multiple swollen hypoechoic and rounded lymph nodes in cervical and supraclavicular region (

Figure 2).

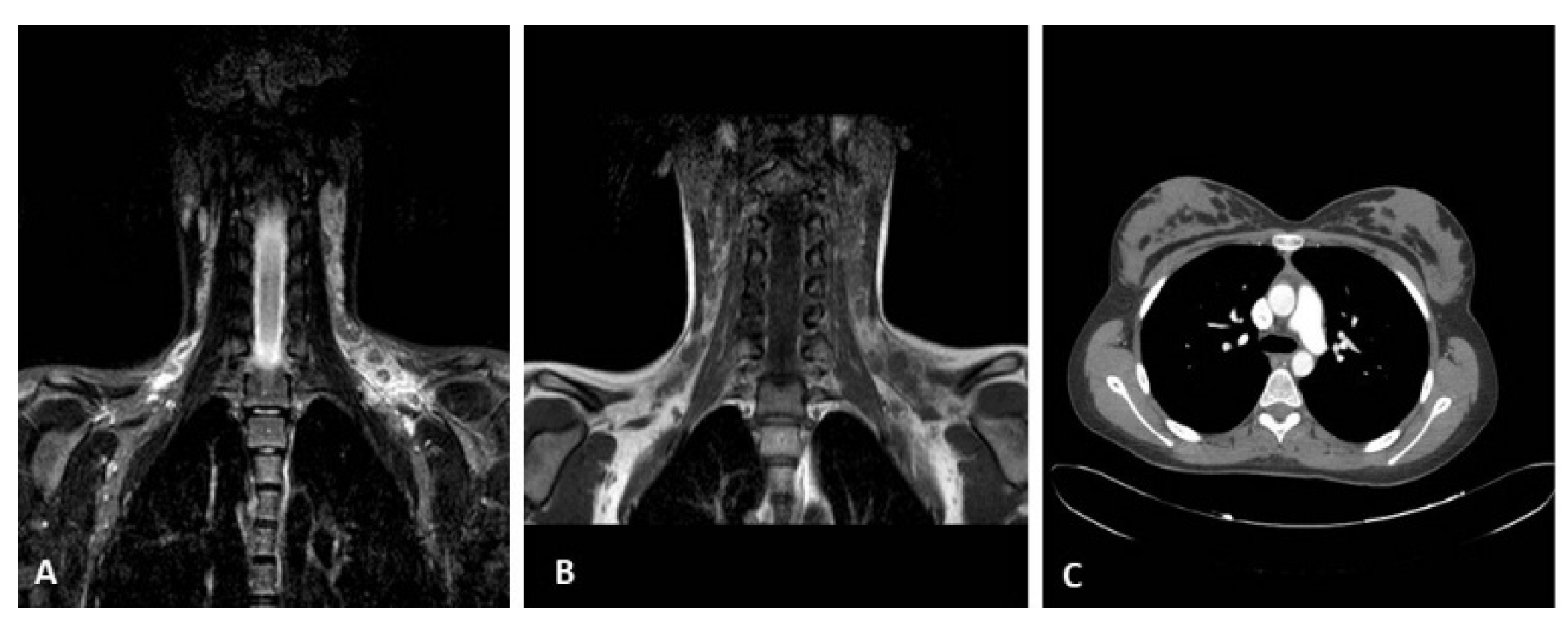

MRI of cervical and supraclavicular region (

Figure 3 A, B): multiple hypoechoic, rounded lymph nodes

CT Thorax & abdomen (

Figure 3 C): No obvious pathological findings, a number of lymph nodes up to 7mm in diameter were observed paraaortically and in the mesentery.

The patient was initially treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, the fever subsided in the 4th day after admission and she remained afebrile afterwards.

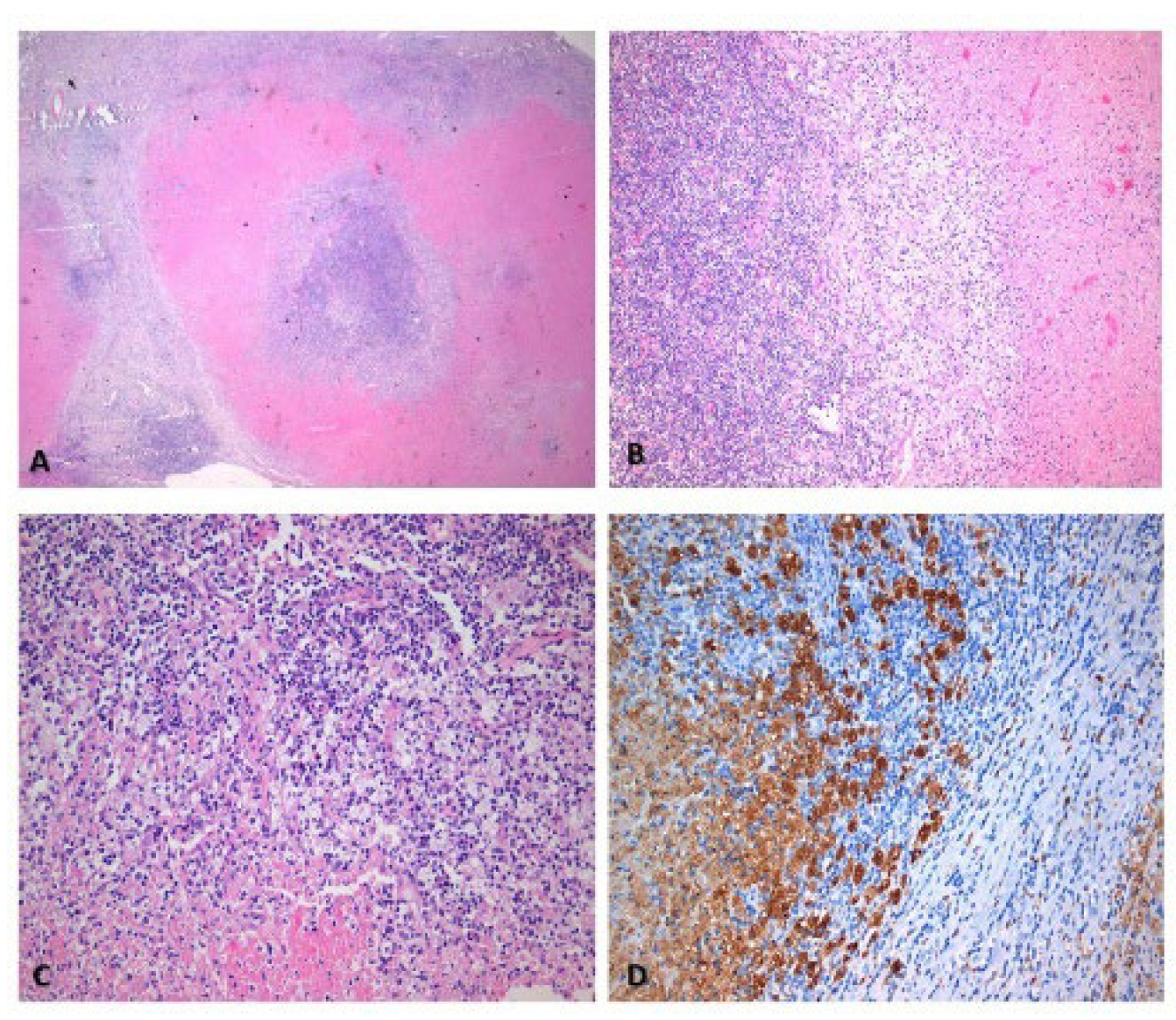

Because of persistence of lymphadenopathy, lymph node biopsy was performed which revealed: lymph node sections 0.6-1.5cm in diameter with significant lesions of necrotic histiocytic apoptotic non-abscessive lymphadenitis,, mainly in necrotic phase. Histopathological findings (

Figure 4) compatible with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease.

After the diagnosis patient was treated with ibuprofen and responded very well with gradual improvement of lymph nodes and improvement of appetite.

In the follow-up one month later, she was asymptomatic (

Figure 5 A), with good appetite and weigh gain, with no palpable cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes and ultrasound almost normal (

Figure 5 B), and leucopenia was recovered, lymphopenia remained for some months. She was advised to have regular check-ups initially every month & three months, immunological check-up every 6-12 months or in case of reappearance of symptoms.

3. Discussion

This case highlights an unusual presentation of Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD) in a pediatric patient, with supraclavicular lymphadenopathy as a key feature—a presentation rarely reported, especially in children. In pediatric practice, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy warrants heightened concern due to its strong association with malignancy compared to anterior cervical lymphadenopathy [

4]. While most childhood cervical lymphadenopathy is reactive or infectious, persistent and non-resolving supraclavicular lymph nodes, especially when hard and non-mobile, raise suspicion for serious underlying conditions such as lymphoma or mediastinal disease.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD), or histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a rare and self-limited condition that primarily affects young women, typically in their second or third decade of life. While it has been widely reported in adults, pediatric presentations, particularly in Western populations [

10], remain uncommon and often pose significant diagnostic challenges due to their nonspecific and sometimes alarming clinical features.

KFD, a rare self-limited disorder of uncertain etiology, typically affects young women between the ages of 20 and 30. Pediatric cases are significantly less common and may be underdiagnosed due to nonspecific presentations such as prolonged fever and lymphadenopathy [

10]. Although most pediatric KFD cases present with posterior cervical lymphadenopathy, supraclavicular involvement is notably rare. In a large series of pediatric KFD cases, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy was not reported as a typical feature [

11].

Our patient presented with persistent cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, prolonged fever, weight loss, and laboratory findings including leukopenia and lymphopenia. These nonspecific symptoms and laboratory abnormalities significantly overlapped with other potential diagnoses such as infectious mononucleosis, tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and hematologic malignancies [

12,

13].

The positive ANA (1:160) in our patient raised concern for an autoimmune process, particularly SLE, which can present similarly and may co-exist or even evolve from KFD [

13]. However, the absence of other serologic or clinical markers of SLE and the lack of systemic involvement helped steer away from this diagnosis.

Ultrasound and MRI revealed multiple hypoechoic, rounded lymph nodes, while CT imaging demonstrated paraaortic and mesenteric lymphadenopathy. These findings initially raised concern for lymphoma. Given the persistence of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms, an excisional biopsy was appropriately performed.

Histopathology remains essential for diagnosis. The biopsy revealed classic features of KFD—patchy paracortical necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, crescentic histiocytes, and an absence of neutrophils—helping to distinguish it from both lymphoma and lupus lymphadenitis [

14,

15].

The exact cause of KFD remains elusive. Although viral triggers such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), and Parvovirus B19 have been proposed, none have shown consistent associations [

6,

7]. Autoimmune hypotheses are gaining ground, particularly in patients with positive autoantibodies or those who develop SLE later [

16]. Hence, close follow-up is warranted in pediatric patients diagnosed with KFD.

Treatment of KFD is mainly supportive. Our patient responded well to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) without requiring corticosteroids or immunomodulatory therapy [

17]. Fever resolved early in the course, and lymphadenopathy improved steadily. She remained asymptomatic at one-month follow-up, with improved appetite, weight gain, and no palpable lymphadenopathy.

This case underlines the importance of considering KFD in the differential diagnosis of persistent cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy in children. Prompt recognition and histologic confirmation can prevent unnecessary interventions, including invasive diagnostics and empiric treatments for suspected malignancy.

4. Conclusions

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD) is a rare, self-limiting cause of lymphadenopathy in children that can closely mimic more serious conditions such as lymphoma or systemic autoimmune diseases. This case highlights the importance of including KFD in the differential diagnosis of persistent cervical and, notably, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy in pediatric patients—an especially unusual presentation.

Early consideration of KFD, along with timely histopathological confirmation, is crucial to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures and treatments. Although the prognosis is generally excellent, long-term follow-up is advisable, particularly in patients with autoimmune markers, given the potential association with systemic lupus erythematosus.

This case underscores the need for heightened clinical awareness of KFD among pediatricians and highlights the diagnostic value of lymph node biopsy in unresolved lymphadenopathy.

Author Contributions

Dr Rogalidou is the first author and wrote the paper and interpreted the data. Drs Rogalidou, & Prof. Makis (Consultants), were the attending physicians responsible for the patient in this case report. Dr Stefanaki is the pathologist who interpreted the biopsy. Prof. Xydis was the radiologist who made radiological assessment of the patient and provided the radiological images. Prof. Chaliasos assisted in editing the draft. All authors have participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting or revising of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed Consent form from parents was obtained for anonymised publication of the patient’s history, photos, and images of histological and radiological findings

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KFD |

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease |

| ANA |

Antinuclear antibody |

| CT |

computed tomography |

| FNAC |

Fine-needle aspiration cytology |

| SLE |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Kg |

Kilogram |

| USA |

United States of America |

| ESR |

erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| EBV |

Epstein Barr Virus |

| CMV |

Cytomegalic virus |

| HIV |

Human Immunodefiency virus |

| ASTO |

antistreptolysine title |

| ACE |

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| ANCA |

anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies |

| IgM |

Immunoglobulin M |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| RF |

Reumatoid Factor |

| IgE |

Immunoglobulin E |

| IgA |

Immunoglobulin A |

| C3 |

Complement 3 |

| C4 |

Complement 4 |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NSAIDs |

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

References

- Weinstock, M.S.; Patel, N.A.; Smith, L.P. Pediatric Cervical Lymphadenopathy. Pediatr. Rev. 2018, 39, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.; Stetson, A.; Blase, J.; Weldon, C.B. Pediatric Lymphadenopathy. Adv. Pediatr. 2025, 72, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.K.; Robson, W.M. Childhood cervical lymphadenopathy. J. Pediatr. Heal. Care 2004, 18, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Devas, G.; Perales, O. A Child With Palpable Supraclavicular Node. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2006, 22, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.; Hwang, J.; Kim, P.H. Diagnostic Performance of Ultrasound for Differentiating Malignant From Benign Cervical Lymphadenopathy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2025, 44, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandni; Hussain, M. ; Ahmad, B.; Haider, N.; Khan, A.G.; Imran, M.; A Chaudhary, M. Etiological Spectrum of Lymphadenopathy Among Children on Lymph Node Biopsy. Cureus 2024, 16, e68102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Ha, K.-S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, J. Characteristics of Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease in children compared with adults. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 173, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, C.B.; Wang, E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010, 134, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, V.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, N.; Rani, R. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 3664–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, R.F.; Berry, G.J. Kikuchi's histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988, 5, 329–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, E.H.; Lee, H.J.; Yun, K.W.; Lee, H. Clinical Characteristics of Severe Histiocytic Necrotizing Lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease) in Children. J. Pediatr. 2016, 171, 208–212.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, X.; Guilabert, A.; Miquel, R.; Campo, E. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease A Comprehensive Review. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004, 122, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukardali, Y.; Solmazgul, E.; Kunter, E.; Oncul, O.; Yildirim, S.; Kaplan, M. Kikuchi–Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 26, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudnall SD, Chen T. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A concise review with emphasis on diagnostic challenges. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144(11):1345–9.

- Perry, A.M.; Choi, S.M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: A Review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.; Lessa, B.; Galrão, L.; Lima, I.; Santiago, M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. Clin. Rheumatol. 2004, 24, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Park, K.H.; Seok, H.J. Management of Kikuchi’s disease using glucocorticoid. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2000, 114, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).