Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

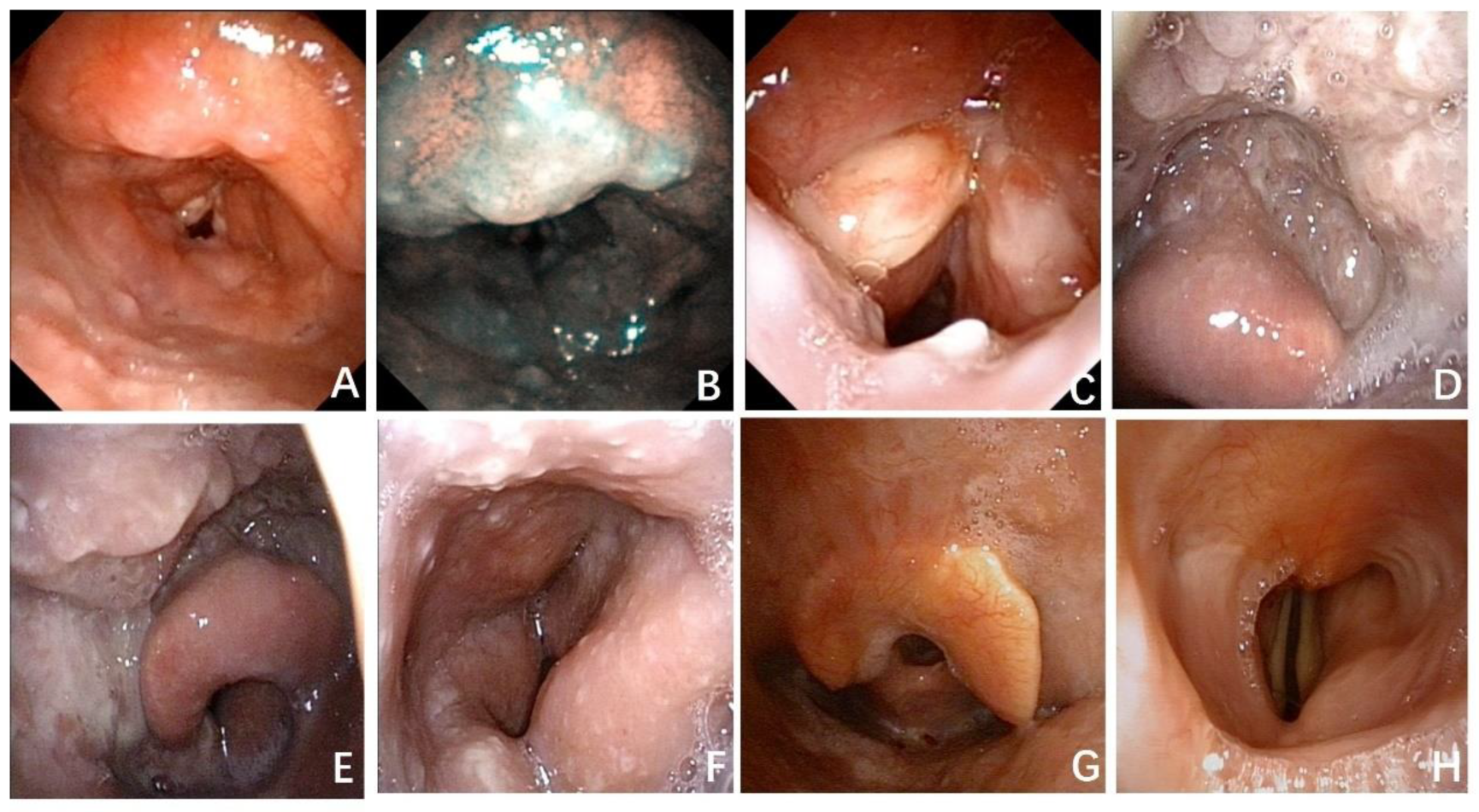

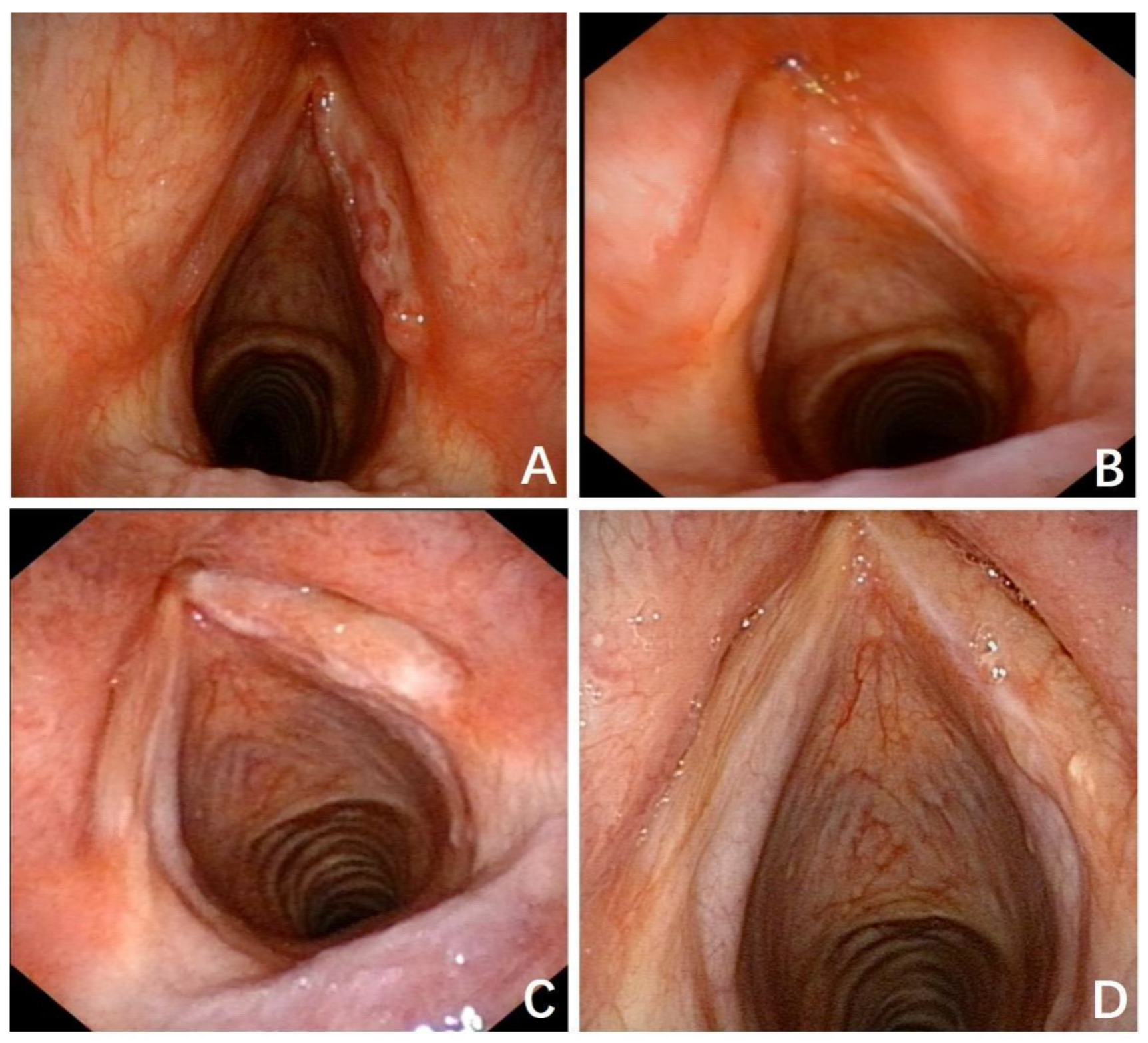

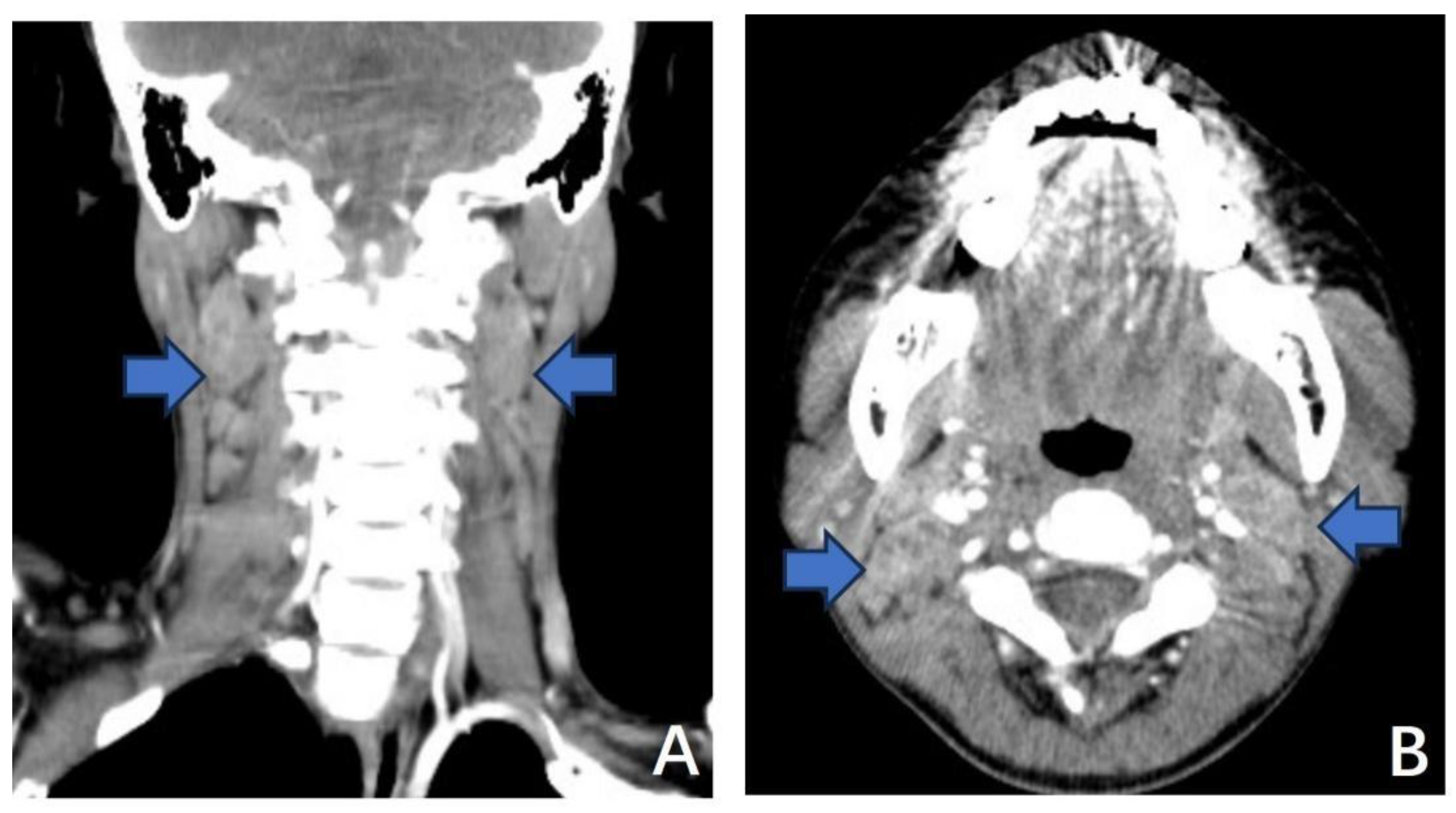

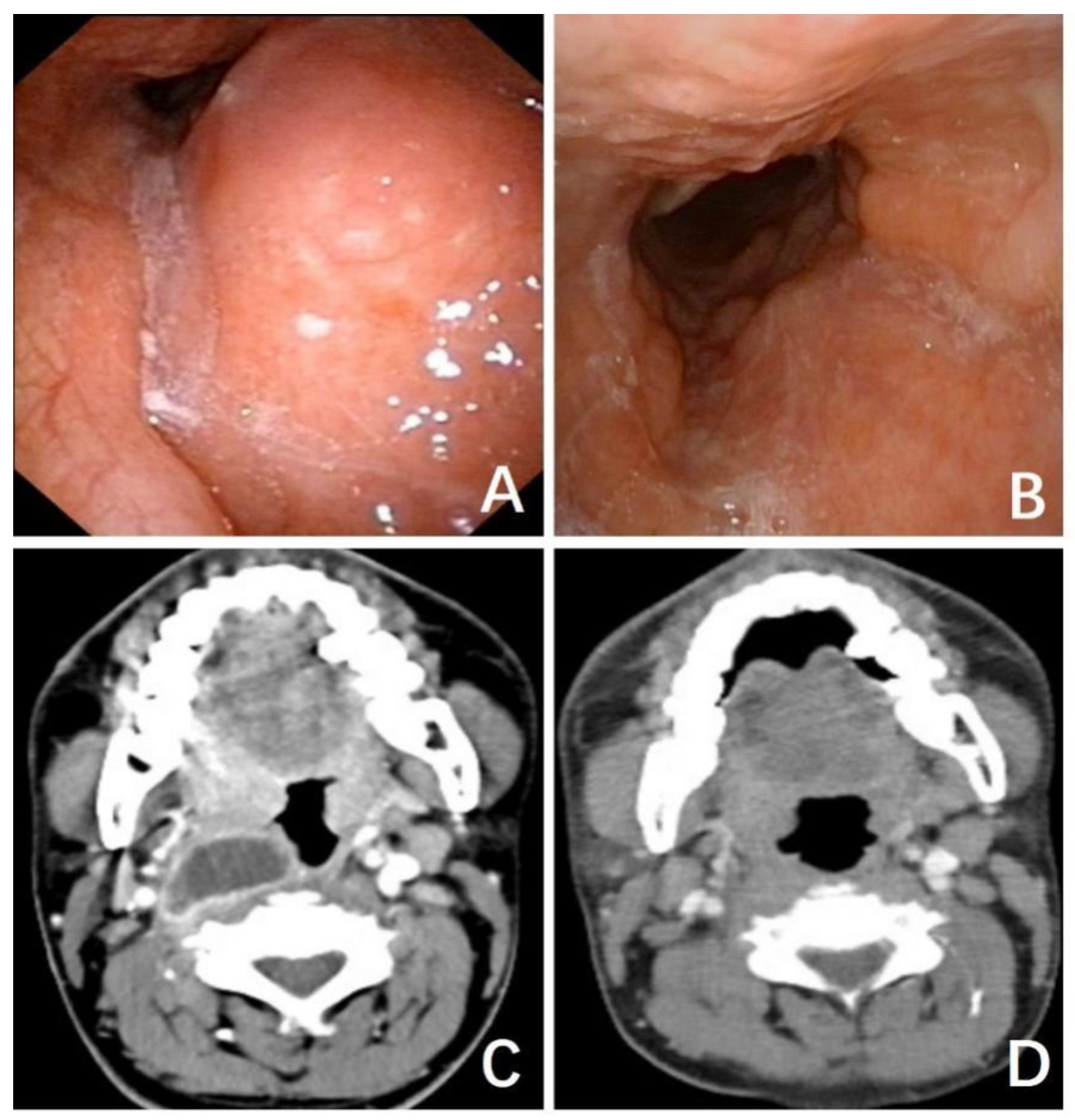

3.1. Typical Cases

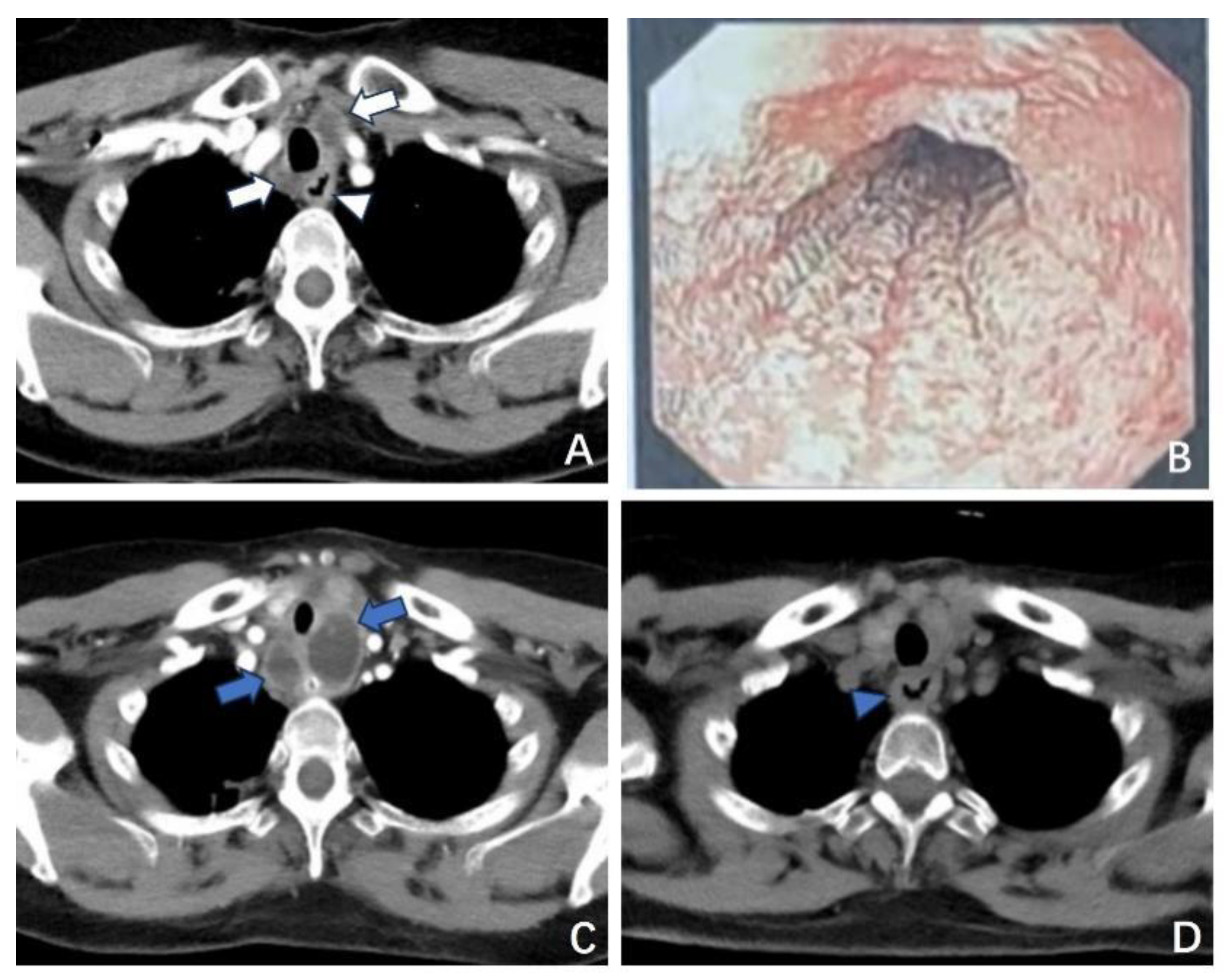

3.1.1. Case 1

3.1.2. Case 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO global tuberculosis report 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851.

- Gambhir S, Ravina M, Rangan K, et al. Imaging in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 56: 237-47.

- Sandgren, A.; Hollo, V.; van der Werf, M.J. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the European Union and European Economic Area, 2002 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucoli, M.; Borello, G.; Boffano, P.; Benech, A. Tuberculous neck lymphadenopathy: A diagnostic challenge. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das S, Das D, Bhuyan UT, Saikia N. Head and Neck Tuberculosis: Scenario in a Tertiary Care Hospital of North Eastern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10(1): MC04-7.

- Bozan, N.; Sakin, Y.F.; Parlak, M.; Bozkuş, F. Suppurative Cervical Tuberculous Lymphadenitis Mimicking a Metastatic Neck Mass. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2016, 27, e565–e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocanu, A.-I.; Mocanu, H.; Moldovan, C.; Soare, I.; Niculet, E.; Tatu, A.L.; Vasile, C.I.; Diculencu, D.; A Postolache, P.; Nechifor, A. Some Manifestations of Tuberculosis in Otorhinolaryngology – Case Series and a Short Review of Related Data from South-Eastern Europe. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, ume 15, 2753–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, S.; Pallagatti, S.; Gupta, D.; Mittal, A. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of mandibular condyle: a diagnostic dilemma. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2012, 41, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajor, A.M.; Józefowicz-Korczyńska, M.; Korzeniewska-Koseła, M.; Kwiatkowska, S. A Clinic-Epidemiological Study of Head and Neck Tuberculosis—A Single-Center Experience. Adv. Respir. Med. 2016, 84, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, H.H.; Gurdal, M.M.; Ozkul, M.H.; Karakas, M.; Uvacin, O.; Kara, N.; Alp, A.; Ozbay, I. Neck masses: diagnostic analysis of 630 cases in Turkish population. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2013, 270, 2953–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Fernandes R. Neck masses: evaluation and diagnostic approach. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2008; 20(3): 321-37.

- Pang, P.; Duan, W.; Liu, S.; Bai, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, F.; Sun, C. Clinical study of tuberculosis in the head and neck region—11 years’ experience and a review of the literature. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, S.; Lee, Y.; Rawat, S.; Luthra, A.; Shah, D.; Ahuja, A. Tuberculosis in the head and neck — a forgotten differential diagnosis. Clin. Radiol. 2010, 65, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashveer, J.K.; Kirti, Y.K. Presentations and Challenges in Tuberculosis of Head and Neck Region. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 68, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, J.; Fu, Q.; He, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Tan, G.; Tao, Z.; Wang, D.; Wen, W.; et al. Chinese Society of Allergy Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 300–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranzani, O.T.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Waldman, E.A.; Carvalho, C.R.R. Estimating the impact of tuberculosis anatomical classification on treatment outcomes: A patient and surveillance perspective analysis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sama, J.; Chida, N.; Polan, R.; Nuzzo, J.; Page, K.; Shah, M. High proportion of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in a low prevalence setting: a retrospective cohort study. Public Health 2016, 138, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeds, I.L.; Magee, M.J.; Kurbatova, E.V.; del Rio, C.; Blumberg, H.M.; Leonard, M.K.; Kraft, C.S. Site of Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis is Associated with HIV Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Albers, A.E.; Nguyen, D.T.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Schreiber, F.; Sinikovic, B.; Bi, X.; Graviss, E.A. Head and neck tuberculosis: Literature review and meta-analysis. Tuberculosis 2019, 116, S78–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, M.; Okamoto, S.; Teranishi, Y.; Yokota, C.; Takano, S.; Iguchi, H. Clinical Study of Extrapulmonary Head and Neck Tuberculosis: A Single-Institute 10-year Experience. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 20, 030–033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa Estomba CM, Betances Reinoso FA, Rivera Schmitz T, Ossa Echeverri CC, Gonzalez Cortes MJ, Santidrian Hidalgo C. Head and neck tuberculosis: 6-year retrospective study. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2016; 67(1): 9-14.

- Zhu XL Chen XW, Yang H, etc. Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis of Laryngeal Tuberculosis. Basic and Clinical Medicine 2011; 31(5): 586-90.

- Bruzgielewicz, A.; Rzepakowska, A.; Osuch-Wójcikewicz, E.; Niemczyk, K.; Chmielewski, R. Tuberculosis of the head and neck – epidemiological and clinical presentation. Arch. Med Sci. 2014, 6, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci HS, Kule M, Kule ZA, Habesoglu TE. Diagnostic challenges in cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis: A review. North Clin Istanb 2016; 3(2): 150-5.

- Chhabra, B.; Vyas, P.; Gupta, P.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, K. Incidence, Diagnosis and Treatment of Otorhinolaryngological, Head and Neck Tuberculosis: A Prospective Clinical Study. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 27, e630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanilla, J.-M.; Barnes, A.; von Reyn, C.F. Current Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Tuberculous Lymphadenitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, T.; Ogawara, Y.; Matsuyama, Y.; Abe, I.; Orita, Y.; Nishizaki, K.; Fujisawa, M.; Nakada, M.; Sato, Y.; Uesaka, K. Factors that make it difficult to diagnose cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.C.; Sreedharan, S.; Chakravarthy, Y.; Prasad, S.C. Tuberculosis in the head and neck: experience in India. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2007, 121, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, R.; Bhojwani, K.M. Manifestations of Tuberculosis in Otorhinolaryngology Practice: A Retrospective Study Conducted in a Coastal City of South India. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 69, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingart, K.R.; Schiller, I.; Horne, D.J.; Pai, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Dendukuri, N.; Sohn, H.; A Kloda, L. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walusimbi, S.; Bwanga, F.; De Costa, A.; Haile, M.; Joloba, M.; Hoffner, S. Meta-analysis to compare the accuracy of GeneXpert, MODS and the WHO 2007 algorithm for diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei B, Wu Z, Min K, Zhang J, Ding C, Wu H. Interferon-gamma release assay in the diagnosis of laryngeal tuberculosis. Acta Otolaryngol 2014; 134(3): 314-7.

- Neville B DD, Allen C et al. Soft tissue tumors. In: Neville B, Damm D, Allen C et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 2nd edition. 2002: W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, pp. 458–61.

- Dheda K, Barry CE, 3rd, Maartens G. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2016; 387(10024): 1211-26.

- Lubben B, Tombach B, Rudack C. [Tubercular spondylitis with retropharyngeal abscess]. HNO 2004; 52(9): 820-3.

- Kosmidou, P.; Kosmidou, A.; Angelis, S.; Dimitriadou, P.P.; Filippou, D. Atypical Retropharyngeal Abscess of Tuberculosis: Diagnostic Reasoning, Management, and Treatment. Cureus 2020, 12, e9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site of Lesion | Total | % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larynx | Lymph node | Pharynx | Salivary | Multiple Sites | |||

| Total | 27(45.00%) | 20(33.33%) | 7(11.67%) | 3(5.00%) | 3(5.00%) | 60 | 100 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 16 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 29 | 48.33 |

| Female | 11 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 31 | 51.67 |

| Age, yrs | |||||||

| <18 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.33 |

| 18-60 | 24 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 47 | 78,33 |

| >60 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 18.33 |

| Typical systemic symptoms | 4 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 28.33 |

| Comorbidities | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 13.33 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8.33 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.67 |

| Tumor | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.33 |

| TB-spot | |||||||

| positive | 11 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 46.67 |

| negative | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 6.67 |

| unidentified | 14 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 28 | 46.67 |

| Confirmed by biopsy | 12 | 16 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 37 | 61.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).