1. Introduction

Scientists and philosophers alike exist within the long tradition of a formalized “inquiry into nature” as outlined in Plato’s

Phaedo. Aristotle attempts to provide a more rigorous structure to the origins of the processes of the natural world which he distilled to the Four Causes. Among them is the Final Cause which is described as a prescient purpose for which a thing exists and toward which it invariable moves. With the Enlightenment arose the atomic and mechanical interpretation of the world along with a deterministic view of physical events. While physical events are typically interpreted through mathematical processes to have a determined future, there exist examples within these mathematics of exceptions to determinism, debated for the fidelity with which they reflect the actual physical world. Such examples might include Norton’s dome (topological singularities) [

1,

2], the n-body problem and infinitely-many degrees of freedom (non-computability), and Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (no system can prove its own consistency from within its own axioms).

As a thought experiment, the nature of the neuronal ion channel borders on the realms of the classical, relativistic, and quantal, and these structures may offer clues that can merge our material conception of physics with the apparent freedom of choice which is subjectively experienced in the human condition. In this work, notions are explored of the ion channel as a topological singularity, the possible non-computability of ion movement at the exit of symmetrical channels, and the role of Brownian movements in neurotransmitter and receptor localization along with the influence of quantum vacuum fluctuations on these movements. Combined, a hypothesis emerges that allows for non-deterministic neuronal activity, along with proposals for study designs aimed at possible falsification of the concept.

Structural and spectroscopic research confirms that the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the prokaryotic NavMs channel forms a flexible linker attached to a four-helix coiled-coil bundle, showcasing tetrameric (square) symmetry [

3,

4]. This suggests that, from a static structural perspective, there is no intrinsic lateral bias, no preferred horizontal direction, for the exit of an ion arising solely due to the CTD of the symmetrical ion channel exit structures. At the moment, let us idealize an isolated NavMs channel within a sterile phosopholipid bilayer membrane structure. In this idealized case, lateral symmetries exist and no external asymmetries are present in the adjacent membrane structure. In an initial state and considering single atomic ions with respect to time, the first sodium ion exiting this channel would be faced with no deterministic forces to cause its movement laterally along the membrane structure. In this, again, idealized scenario, it would seem the ion channel would exhibit some qualities of Norton’s dome or a topological source singularity with respect to charge density centered on the ion channel pore exit. Such an idealized situation may be experimentally feasible within the laboratory allowing for measurement of intracellular charge density with respect to time.

1.1. Ion Channel Structure and Function

Ion channels form the basis for neuronal polarization, required for signal transduction along a the phospholipid bilayer of a cell membrane, which leads to cellular functions ranging from genetic transcription and metabolic activity changes to neurotransmitter release [

5]. On the level of the whole neuron, patterns of neuronal depolarization are integrated across voltage-sensitive membrane-bound ion channels producing non-linear whole cellular responses [

6]. This aggregated activity along the membrane of a single neuron is triggered by the summation of small, regional depolarizations (graded potentials) that, once combined to trigger an increase in membrane potential of approximately 15 mV from the resting state, lead to a cascade of ion channel activity (an action potential) across the entire cell membrane.

The smaller, localized graded potentials are the result of the binding of neurotransmitter molecules to a synaptic receptor on a receiving, or post-synaptic, neuron membrane leading to a physical deformation of the associated ion channel which allows passage of atomic ions. The post-synaptic neuron localizes these receptors within the synaptic membrane of its dendritic spine (post-synaptic terminal) which is physically bound to the terminal bouton of the pre-synaptic neuron. Within these localized regions called synapses, the number of individual receptors has been quantified with a range approximating 10 to 1000 individual receptors which can vary based on the strength of the synapse (a function of neuronal plasticity dependent on rate of prior synaptic activity) [

7]. In neuroscientific terms, a single episode of neurotransmitter release is counted as one “quantal” event and may or may not lead to neuronal “firing” defined as the propagation of an action potential across the target neuron’s plasma membrane and ultimate release of synaptic neurotransmitter molecules. This dependency rests on the number of neurotransmitters that diffuse across the synaptic cleft to bind to receptors and the subsequent chain of molecular and atomic events in the post-synaptic cell.

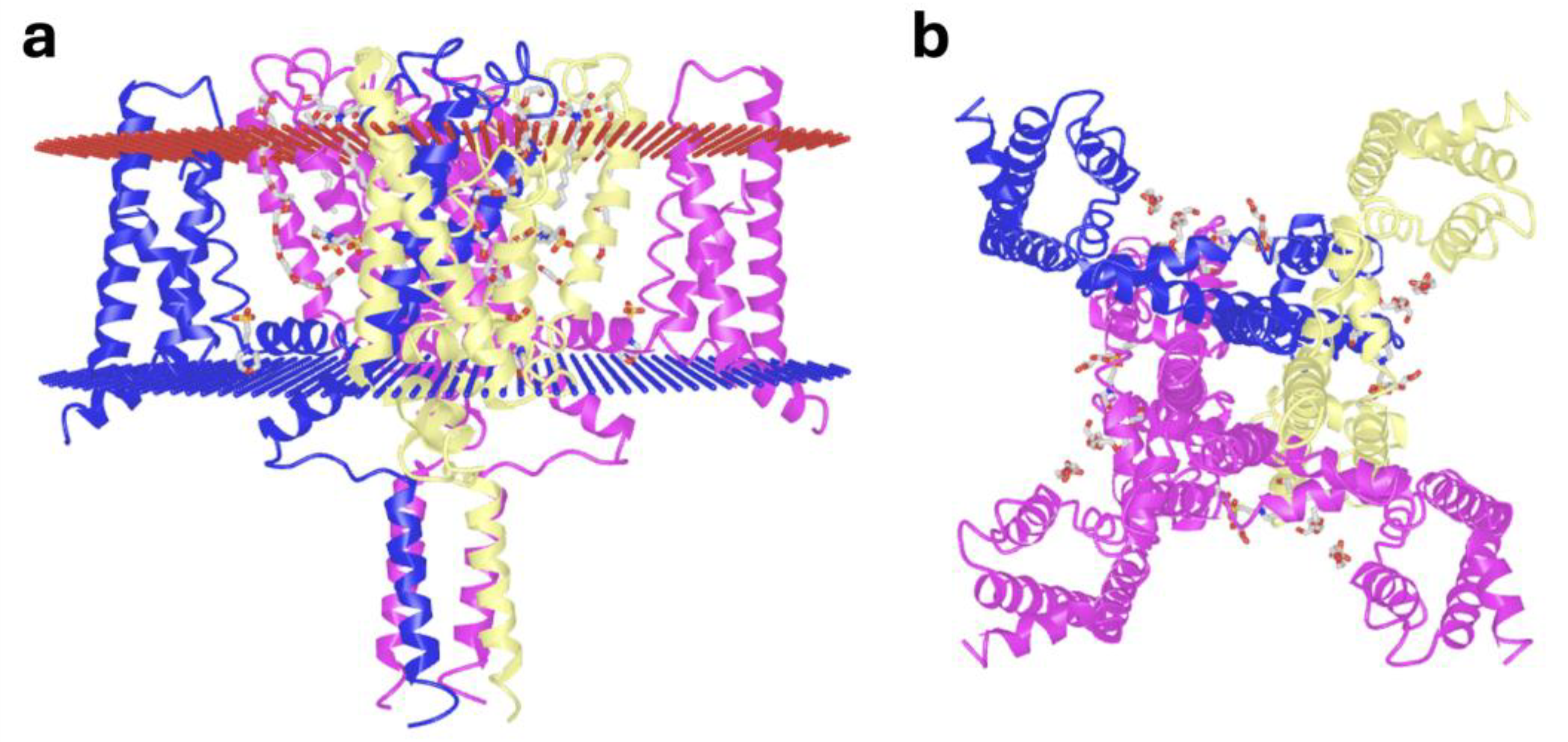

Progressing to the molecular level, a wide range of ion channels exist which are specialized in different functions and aspects of neuronal depolarization. Some ion channels are subsets of receptors that physically open upon binding of a neurotransmitter, while others may be independent units that are sensitive to environmental conditions such as local membrane potential. For the present purposes, I would like to take as a stereotyped ion channel the NavMs tetrameric sodium channel (

Figure 1). As a tetramer, this channel is composed of four identical units, creating a symmetry along two axes with the sodium ion centered at the intersection of these axes.

1.2. Sub-Synaptic Structures, Brownian Motion, and Vacuum Fluctuations

As the above isolated channel is an idealized thought experiment, it is important to attempt to consider all influences on this structure to conceive of the full picture in the living cell. The NavMs ion channel CTD has also been shown to be molecularly dynamic and flexible [

4]. Analyses have revealed that receptor dynamics are governed by Brownian motion with differing velocities inside and outside of synapses suggesting a membrane localization function [

8]. Assuming an organizing principle, energetic landscapes, electrostatic protein subunits, and other features, the cell may consistently coordinate an ion channel to create an electromagnetic influence that overcomes the conceptually non-deterministic release of the initial ion from the ion channel. Because of this, other cases should be conceptualized to take into consideration the composite environment of the plasma membrane for practical considerations.

Neurotransmitters are stored in synaptic vesicles within the synaptic bouton, awaiting release from the pre-synaptic neuron. Upon pre-synaptic neuronal depolarization, the synaptic vesicle responds to the change in polarization by enacting a concerted series of energetic molecular events leading to the merging of the vesicle’s membrane with the cell’s plasma membrane, releasing the vesicle’s contents to diffuse into the synaptic cleft. During this quantal neurotransmitter release, tens of thousands of neurotransmitter molecules are released to diffuse into the synaptic cleft.

Conceptually there exists an epicenter for this neurotransmitter release and a diffusion gradient spreading outward from this location, which implies that there exists a single receptor among only dozens on the post-synaptic neuron positioned to be the first to bind a neurotransmitter. Can the indeterminacy of the directionality of this first ion exiting from this first receptor-bound ion channel have an impact on the depolarization of the whole neuron? In other words, is the density of channels such that it is non-uniform so that one area of the synapse or one direction away from an initiating ion channel more or less likely to result in an action potential at a given time? Is the Brownian motion of membrane-bound receptors influenced by non-computable or unpredictable quantum-physical effects such as vacuum fluctuations? Macroscopic currents [

9] and global, stochastic pore fluctuations [

10] have been studied and probabilistic mathematical frameworks provide predictive power, but the nature of isolated channels in an initial state are not clearly defined. Recently, researchers at the Laser Interferometer Gravitation-wave Observatory (LIGO) measured the effect of quantum vacuum fluctuations on a 40 kg mirror, indicating that this quantum noise was enough to move the mirror by 10

-20 meters [

11] (compared to a hydrogen atom’s diameter at approximately 10

-10 meters). It seems conceptually justifiable to admit that quantum vacuum fluctuations (as it were) can influence the motion of receptors and ions within or on the surface of a plasma membrane. As such, these quantum-physical effects may at any given moment result in unpredictable movements of ion channels or receptors to a location more or less likely to propagate depolarization, more or less likely to result in reaching the threshold for a cellular action potential. Additionally, electrostatic analogs of the n-body problem should be considered with regard to analytical unsolvability or non-computability. If so, an element of the movements of these receptors may be influenced by on-determinable processes.

In the philosophy of science, it remains interesting to consider that there exists a symmetrical, electrostatic protein structure that may share non-deterministic attributes of a topological singularity, and that unsolvable or non-computable physical events may contribute to the realization of a neuronal action potential. There also exist potential real-world applications of any potential knowledge gleaned from research on this topic, such as measurements of consciousness, understanding of the boundary conditions between life and death, and the function or dysfunction of individual neurons in the normal state and pathological conditions such as epilepsy, dementia, and movement disorders.

1.3. Falsifiable Experimental Proposal

What follows are methods consisting of a mathematical model for a suggested experimental protocol that treats the lateral exit of an initial transiting ion as Brownian motion on a symmetric surface which shows that small perturbations, perhaps at the level of the quantum vacuum noise, can bias the direction of this lateral exit. Experimental data on the position of ions after transiting through an isolated channel in a sterile membrane have the potential to falsify the hypothesis that quantum noise can unpredictably influence cellular-level events.

2. Materials and Methods

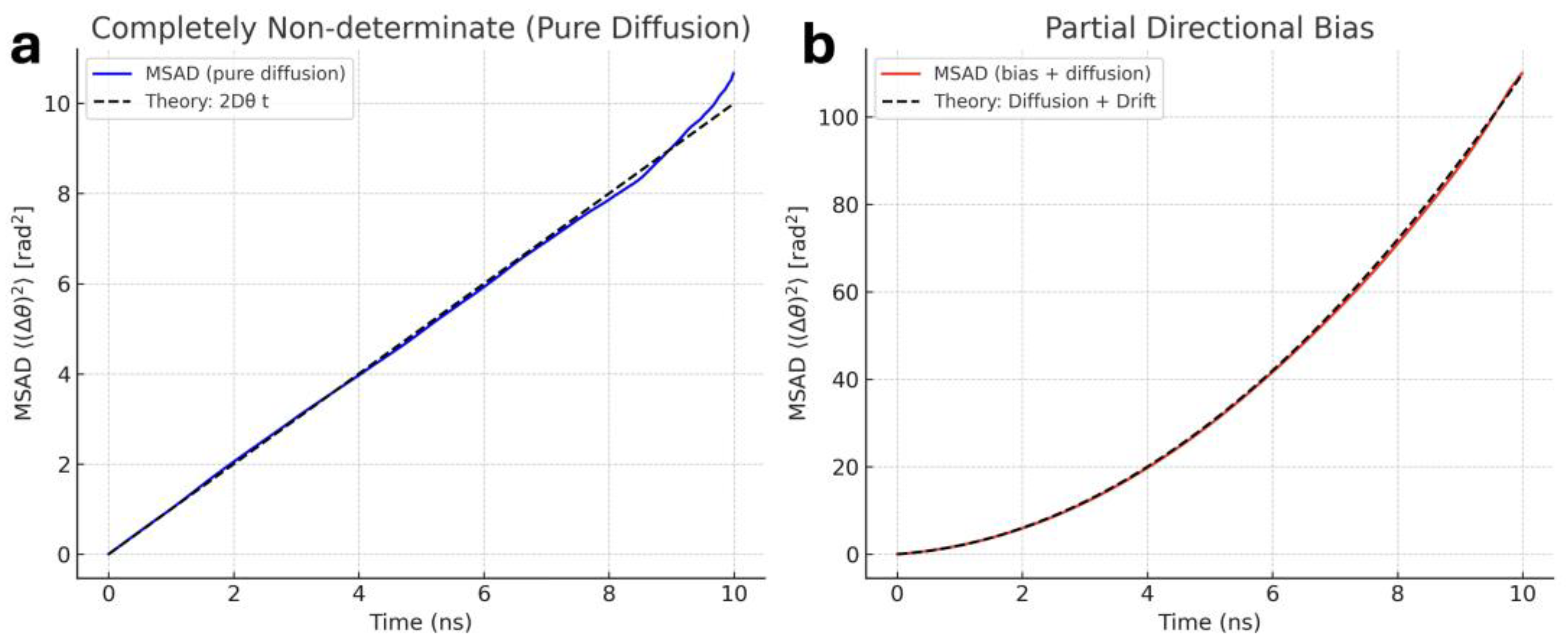

Contained in this Methods section is an in silico study using synthetic data to visualize the possible outcomes of two cases related to the idealized, isolated ion channel embedded in a sterile phospholipid bilayer membrane. The first case is intended to reflect the case of an ion channel without forces governing the lateral exit of ions from its channel. Such a case is intended to represent the unsolvable/non-computable/non-deterministic case. The second case is intended to describe an ion channel that contains a governing force resulting in a computable, predictable direction of exit for a given ion. See Supplementary Material 1 for a detailed mathematical justification.

2.1. Structural Data Acquisition

Atomic coordinates for the full-length, open-state

Magnetococcus marinus NavMs sodium channel were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 5HVX), originally determined by Sula et al. [

3]. The model includes the voltage-sensor domains, pore-forming helices, selectivity filter, and the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD). Symmetry and geometry analyses were performed using UCSF ChimeraX [

12] with default van der Waals radii.

2.2. Coordinate Frame Definition

To examine ion exit trajectories relative to the CTD, a coordinate frame was established with:

z-axis aligned with the channel’s central pore axis (extracellular → intracellular direction).

x–y plane located at the midpoint of the CTD’s intracellular opening.

Azimuthal angle (θ) measured counterclockwise in the x–y plane from a reference point on the CTD symmetry axis.

This allowed quantification of potential lateral symmetry in the exit environment.

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

To model ion movement post-exit, all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used in GROMACS 2023.1.

Force field: CHARMM36m for proteins, TIP3P water model, and standard CHARMM ion parameters for Na⁺.

System setup: The NavMs channel was embedded in an idealized symmetric POPC bilayer with no other proteins, surrounded by a cylindrical water box extending 10 nm radially and 10 nm axially on each side. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions.

Equilibration: 1 ns NVT followed by 10 ns NPT equilibration at 300 K, 1 atm, using the velocity-rescaling thermostat and Parrinello–Rahman barostat.

Production runs: 200 ns NVT simulations, each starting with a single Na⁺ ion placed 0.2 nm above the intracellular gate along the pore axis with randomized thermal velocities (Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution at 300 K).

Electric field: No external electric field was applied to isolate purely structural and thermal influences.

2.4. Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculations

PMF profiles in cylindrical coordinates (r, θ, z) were computed using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) on umbrella sampling trajectories. Sampling windows were centered along a hemispherical shell of radius 0.5–1.5 nm from the pore exit. The resulting free energy surface at fixed = 0 was analyzed for azimuthal bias.

2.5. Symmetry Quantification

Azimuthal symmetry in the PMF was quantified using Fourier decomposition:

where a

0 is the mean free energy. An idealized perfectly symmetric system should yield

for all

.. Deviations were interpreted as directional biases in ion exit trajectories.

2.6. Idealized Analytical Model

For comparison, constructed an idealized diffusion model was constructed for an ion in a cylindrical pore with a symmetric aperture at z = 0:

with boundary conditions enforcing cylindrical symmetry and absorbing walls at r = R. This model yields an isotropic angular distribution P(θ)=const in the absence of structural perturbations, equivalent to the “fountain” trajectories illustrated schematically.

2.7. Visualization

Structural and simulation-derived geometries were rendered in VMD 1.9.4a and ChimeraX, with trajectory analysis using MDAnalysis 2.6. Schematic figures were created in Inkscape based on the PDB coordinates for accurate proportions of the CTD aperture.

3. Results

Synthetic data based on two cases were processed with the purpose of simulating both a non-determinate system and a system with a partial directional bias in the structure of an idealized, isolated ion channel within a sterile phospholipid bilayer (

Figure 2). In a system governed by stochastic elements such as Brownian motion, a linear slope with respect to time was observed. In the system intended to simulate partial directional bias, a non-linear slope is present.

4. Discussion

The in silico analysis suggests a detectable difference between a simulated ion channel with and without structural forces governing the exit of ions from the intracellular CTD of the channel. In the case of an ion channel that does not contain these governing forces, the symmetry of the ion channel would suggest non-computability of the lateral directionality of an initial, lone ion as it exits the channel, such as in the case of a topological source singularity. In vivo and in vitro conditions differ markedly from this thought experiment. However, the contribution of Brownian movement and the potential for influence by quantum vacuum fluctuation or noise introduces the potential for another source of non-determinable physics. Furthermore, the Coulomb potential is a direct mathematical analog of the gravitational potential, suggesting that the n-body problem is relevant to the electrostatic environment of the biological cell. This carries with it not only the computational power limitations but also the analytical unsolvability of the gravitational n-body problem.

A symmetrical ion channel may or may not present structural, calculable forces that govern ion channel directionality. Whether such a case can influence the action potential across an entire cell is another question. In this thought experiment, it seems reasonable to suggest that the direction of exit of an initial ion could be preferential to activation or quiescence of a nearby voltage-gated ion channel on the edge of the range necessary for its governing forces. In such a case, this second ion channel would likely exhibit stochastic individual responses in a holistically probabilistic nature with respect to its distance from our initiating channel. Due to molecular physical influences, design of this two-channel system in a practical in vitro experiment seems challenging. Such a concept, continued toward the limit of an unending, circuitous cellular network, may manifest as stochastic individual cellular activity and self-organizing resting wave patterns [

13,

14].

5. Conclusions

While the thought experiment of an isolated ion channel may hold its own philosophical value, clear limitations exist when attempting to describe the complexity of a realized living system, one in which a variety of forces are continuously at work. While the present work was performed in silico, an actualized laboratory model may be possible in order to recapitulate in vitro the synthetic data provided in this study. Such real-world data, subject to issues of experimental accuracy and inherent error or deviations, may be inconclusive, as any deviation from linearity of MSAD with respect to time could be viewed as a subtle directional bias and evidence of deterministic forces. Furthermore, whether non-determinate aspects may be argued to exist for an isolated ion channel in an idealized state, this may be insufficient to substantiate non-deterministic activity in a realized cell even when combined with other unsolvable or non-computable physics. The conversation surrounding determinism and the will are bound to live on as fervently as ever. However, real-world data would place constraints on the subject and potentially provide interesting insights into the normal and pathological human conditions involving the activity of cellular ion channels, all of which could be considered worthy scientific pursuits.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of mathematical validation. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CTD |

C-terminal domain |

| MSAD |

mean squared angular displacement |

| PMF |

potential mean force |

| WHAM |

Weighted Histogram Analysis Method |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Setup and Notation

Let the channel axis be the

z-axis (extracellular → intracellular). Use cylindrical coordinates

for the ionic position

. The dynamics were split into an axial coordinate

(through the pore), a radial coordinate

, and an azimuthal coordinate

. The total effective potential (potential of mean force, PMF) is denoted

, defined by:

where

is the equilibrium marginal density for the restrained degrees of freedom (standard PMF definition; see Torrie & Valleau (1977), Kumar et al. (1992)). The deterministic conservative force is

.

Two related questions were considered:

at the intracellular mouth?

All statements below are stated with precise conditions and linked to quantities directly measurable by MD/PMF.

Appendix A.2. Azimuthal (lateral) force and symmetry: a lemma

Lemma 1 (Azimuthal force vanishes under transverse symmetry).

Suppose the PMF near the intracellular mouth is invariant under rotations about the channel axis, i.e.,

Then the azimuthal deterministic force componentis zero:

Proof. Direct differentiation of the assumed gives . Using cylindrical coordinates the azimuthal force is , hence .

In practice MD/PMF will return ; symmetry is tested by computing Fourier components in or by constructing at fixed . If coefficients for are statistically indistinguishable from zero (within bootstrap error) one accepts the symmetric hypothesis.

Appendix A.3. Stochastic azimuthal dynamics: diffusion on the circle

If

, the leading-order stochastic dynamics for

(overdamped angular motion) is the pure diffusion SDE on the circle:

or equivalently

where

is standard white noise and

is an effective angular friction. The corresponding Fokker–Planck equation for the probability density

With uniform initial condition in the stationary solution is (isotropic), and more generally the Green’s function for diffusion on the circle is known in closed form (Fourier series).

Practical diagnostic (from MD): estimate

from the mean-squared angular displacement (MSAD),

for diffusive regimes (after angle unwrapping). If

is large enough that angular decorrelation time

(first nonzero eigenvalue

) is short compared to axial transit times, the observed exit azimuth is effectively randomized.

Appendix A.4. Reduction to axial deterministic ODE and Lipschitz (uniqueness) criterion

Consider the axial (one-dimensional) reduction. Suppose the ion’s axial motion is well captured by the 1-D potential

(e.g., after averaging over fast transverse modes or fixing

. The deterministic reduction yields:

Classical Picard–Lindelöf uniqueness for the initial value problem requires be (locally) Lipschitz: there exists such that near initial values. A sufficient condition is that is bounded in a neighborhood.

Norton-type pathology. Norton’s dome example uses with (equivalently ); then diverges as and so is not Lipschitz at 0, allowing non-unique solutions (Norton, various essays). To test for such behavior in MD/PMF, do a small- fit:

Then

and

Thus remains bounded as if . Norton-type non-Lipschitzness requires (so with ). Therefore:

Criterion A (Lipschitz test). Fit the PMF near the mouth to . If (within error bars), then is locally Lipschitz and classical uniqueness holds for the deterministic reduction. If with statistical significance, then the deterministic reduction has the non-Lipschitz form required for Norton-type multiple solutions and warrants further mathematical scrutiny.

Appendix A.5. Role of stochastic forcing: Langevin equation and dominance criterion

Real molecular systems experience thermal noise and dissipation. The 1-D stochastic model is the Langevin equation

with

the axial friction coefficient and

normalized white noise. Two points are critical:

Existence & uniqueness for SDEs. Under standard conditions (Lipschitz drift and diffusion coefficients) SDEs have unique strong solutions (Øksendal 2003). If the deterministic drift is non-Lipschitz, existence/uniqueness for the SDE is more delicate, but thermal noise typically regularizes dynamics in practice (stochastic solutions may be unique where deterministic ODEs are not). See Øksendal (2003) and discussions in stochastic analysis literature.

-

Dominance criterion (when noise overwhelms singular deterministic term). Compare the magnitudes of deterministic acceleration and stochastic accelerations on a characteristic length scale .

where is the characteristic observation time (or the timescale over which accelerations are compared). If for in the region where non-Lipschitzness would occur (i.e., small ), then stochastic fluctuations dominate dynamics and the physical behavior is probabilistic (Kramers-type escapes or diffusion) rather than the deterministic multi-solution branching of the Norton example.

A more refined dimensionless test (useful with MD estimates):

If in the region of interest, stochasticity dominates. Practically, estimate from PMF, from velocity autocorrelation / friction estimates, and choose as the local escape time scale.

Appendix A.6. Kramers rate and physical outcome

If the PMF presents a barrier of height

between the pore interior and the unbound cytosolic reservoir, transitions are governed by Kramers reaction-rate theory. In the high-friction (overdamped) limit the escape rate is approximately

where

and

are curvature frequencies at the well minimum and barrier top respectively; alternative prefactors exist for different damping regimes. The important point is that barrier crossing is exponentially suppressed with

, and the relevant dynamics are stochastic, not deterministic branching.

If PMF lacks a barrier and instead is monotone near exit, then axial passage is drift dominated; still, the small- scaling of determines whether the deterministic reduction is Lipschitz.

Appendix A.7. Operational protocol for falsification (connects math to MD/PMF measures)

Compute by umbrella sampling/WHAM along the channel axis through the intracellular mouth (spacing ; see Torrie & Valleau, Kumar et al.). Fit for small to . Determine 95% confidence interval for

Compute at fixed (inside vestibule). Decompose into Fourier series; test whether nonzero modes exceed sampling noise. If is flat within errors and (from MSAD) shows rapid decorrelation, lateral exit is effectively isotropic/stochastic.

Estimate friction and compute . If over the region where non-Lipschitzness might appear, stochastic noise dominates and the deterministic nonuniqueness is physically irrelevant.

Ifwith significance, perform additional checks: increase sampling, perform QM/MM near-contact tests to rule out force-field artifacts, and attempt a rigorous derivation of the effective reduced ODE from the multi-particle Hamiltonian (this is required before claiming a physically realized Norton pathology).

Appendix A.8. Summary (mathematical conclusions)

Under exact transverse rotational symmetry the azimuthal deterministic force is zero (Lemma 1) and the azimuthal coordinate is described, to leading order, by diffusion on the circle; hence lateral exit angles are stochastic and (absent external symmetry breaking) isotropic. This is a robust, testable prediction: measure and . (Refs: Gardiner; Risken.)

Norton-type non-Lipschitz indeterminism requires a specific small-fractional scaling of the PMF, with . This is a concrete, falsifiable hypothesis: fit PMF data to test . If or if thermal noise dominates (), the physical system will not realize the deterministic nonuniqueness exemplified by Norton’s dome.

References

- Norton, J. The dome: An unexpectedly simple failure of determinism. Philosophia Scientiae. Travaux d’Histoire des Sciences et de Philosophie 2008, 75, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.R. Topological singularities in wave fields; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2001; Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/physics/media/theory-theses/dennis-mr-thesis.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Sula, A.; et al. The complete structure of an activated open sodium channel. Nature communications 2017, 8, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnéris, C.; et al. Role of the C-terminal domain in the structure and function of tetrameric sodium channels. Nature communications 2013, 4, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, G.N. A revolution in the physiology of the living cell; Krieger Pub. Co: Malabar, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, P.A. , Sherman, A. and Stojilkovic, S.S. Common and diverse elements of ion channels and receptors underlying electrical activity in endocrine pituitary cells. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2018, 463, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrizio, A.; Specht, C.G. Counting numbers of synaptic proteins: absolute quantification and single molecule imaging techniques. Neurophotonics 2016, 3, 041805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévi, S.; Triller, A. Neurotransmitter dynamics. In The Dynamic Synapse: Molecular Methods in Ionotropic Receptor Biology; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nekouzadeh, A.; Rudy, Y. Statistical properties of ion channel records. Part I: relationship to the macroscopic current. Mathematical biosciences 2007, 210, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, R.C.; O’Donnell, C.; Nolan, M.F. Stochastic ion channel gating in dendritic neurons: morphology dependence and probabilistic synaptic activation of dendritic spikes. PLoS computational biology 2010, 6, e1000886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; et al. Quantum correlations between light and the kilogram-mass mirrors of LIGO. Nature 2020, 583, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Qu, Z.; Karma, A. Stochastic initiation and termination of calcium-mediated triggered activity in cardiac myocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, E270–E279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, A.; Ranft, J.; Hakim, V. Synchronization, stochasticity, and phase waves in neuronal networks with spatially-structured connectivity. Frontiers in computational neuroscience 2020, 14, 569644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).