Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

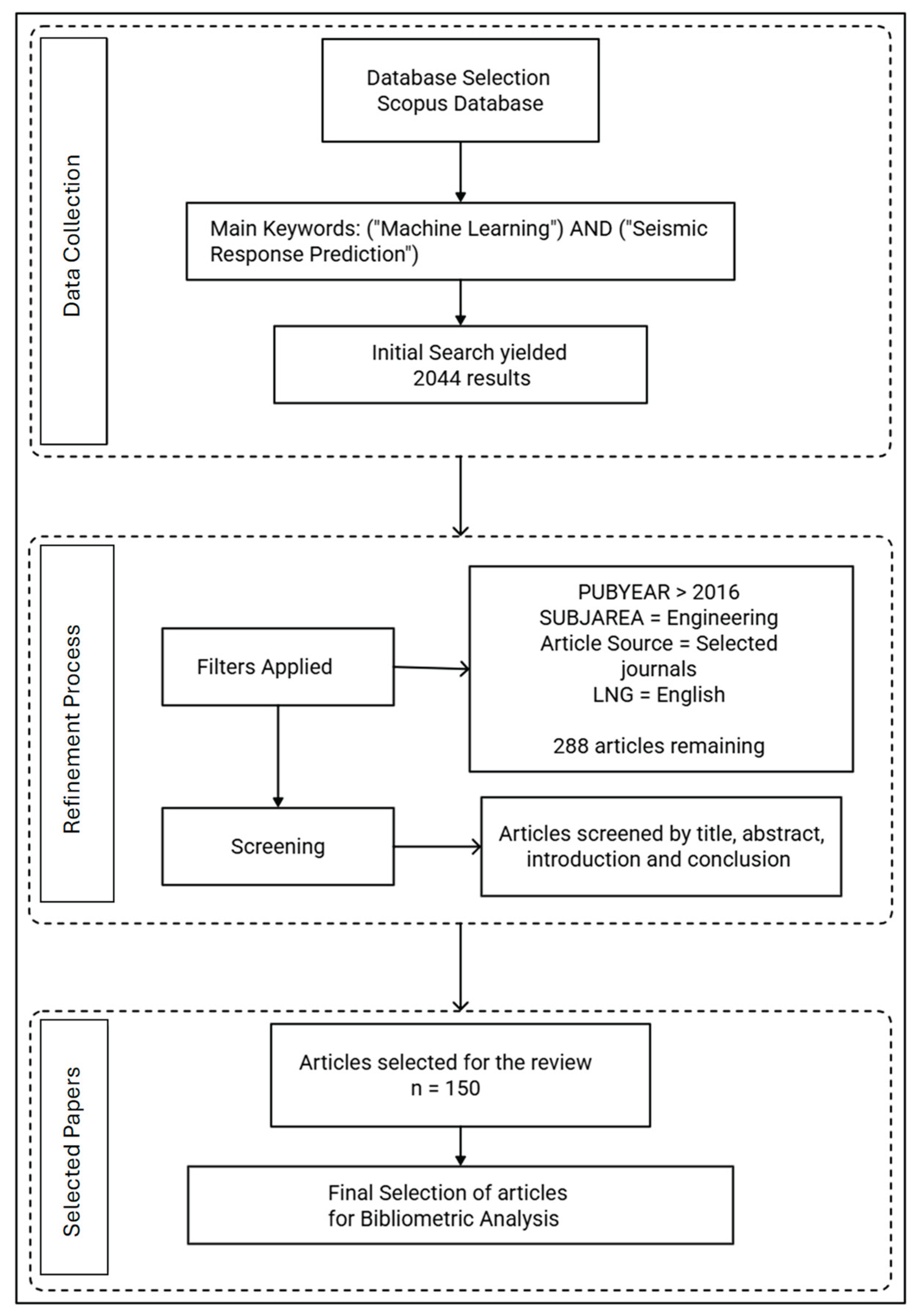

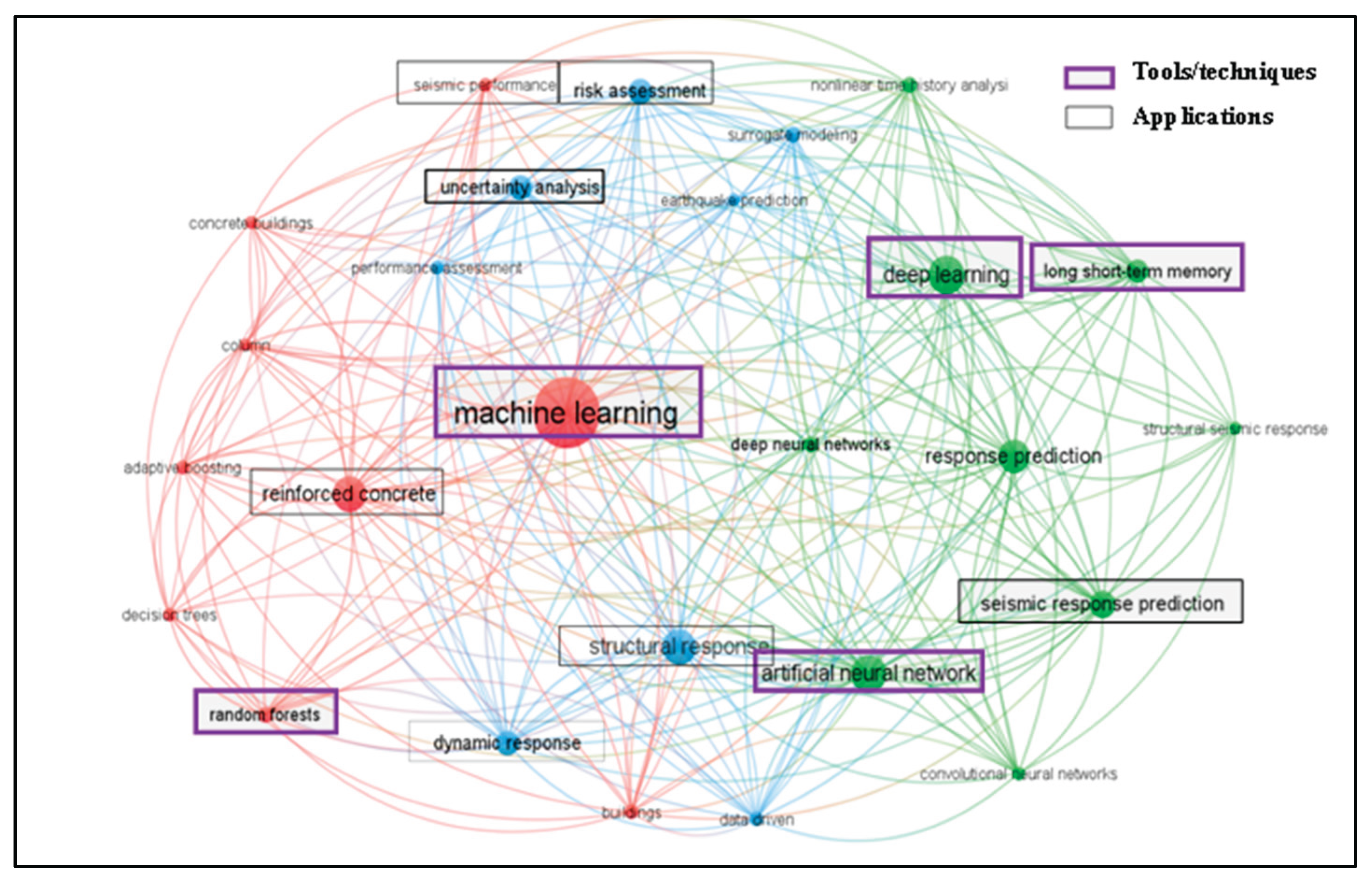

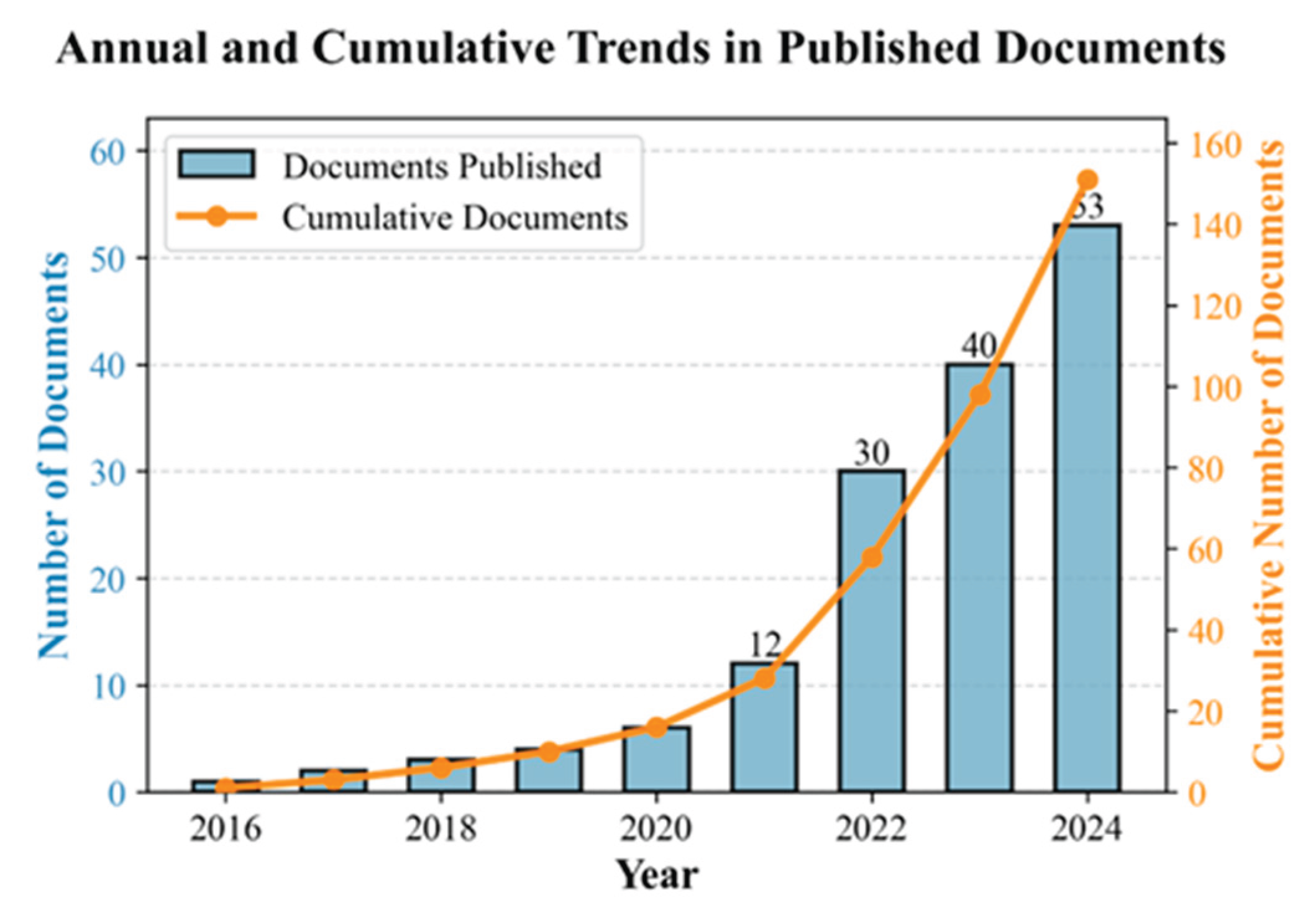

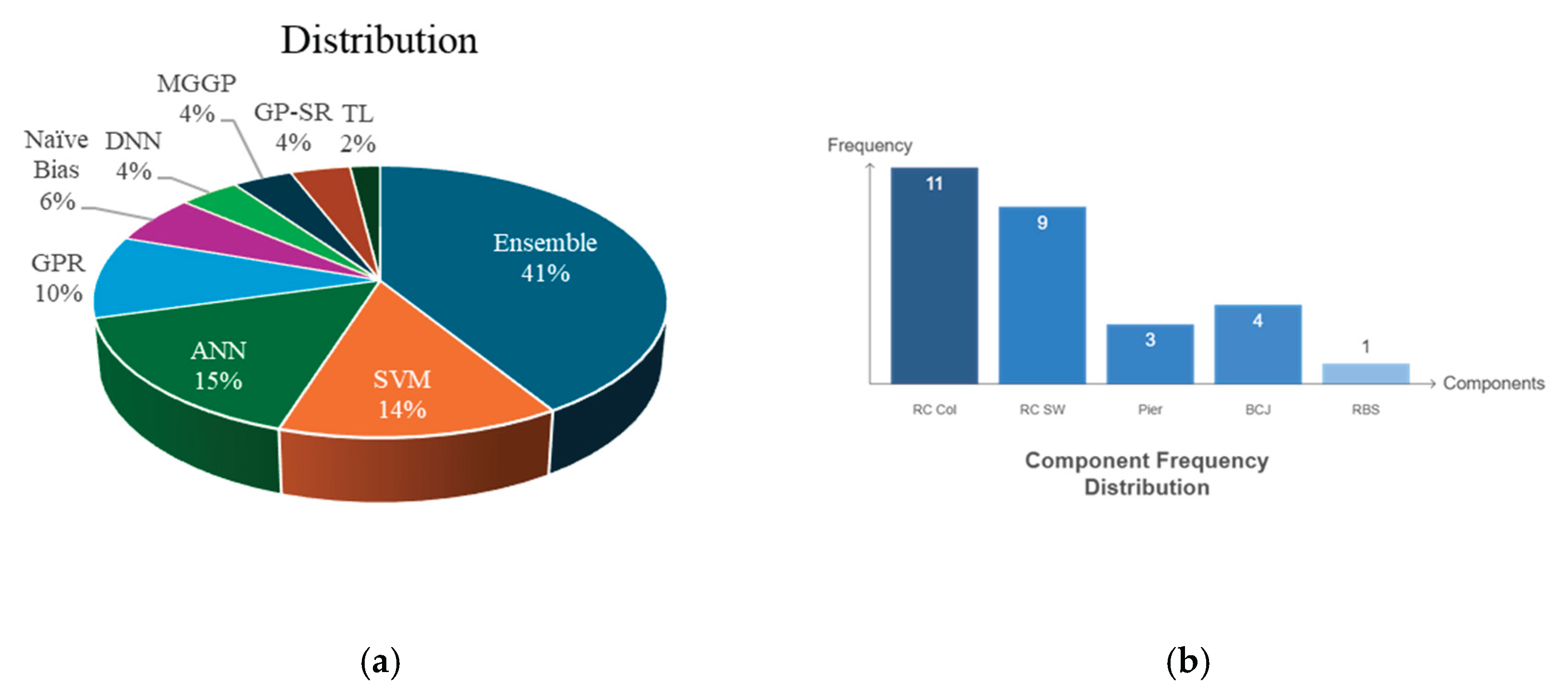

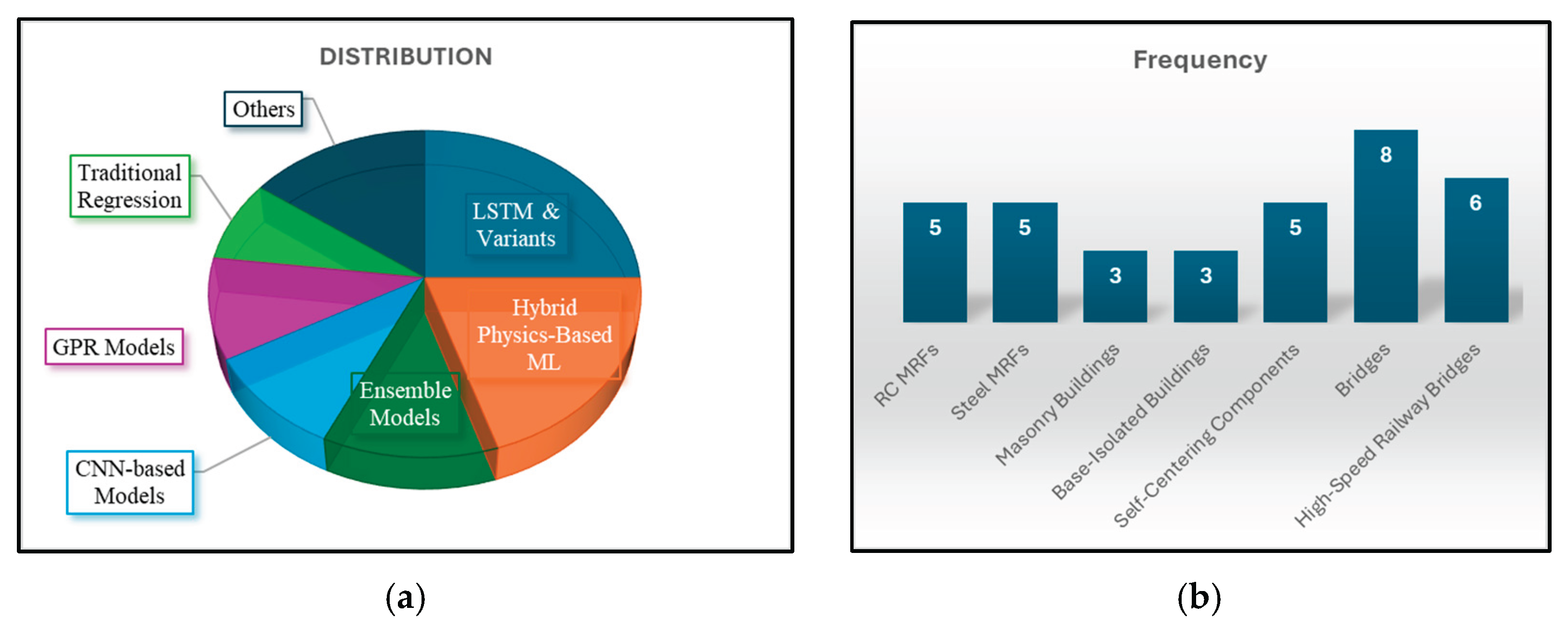

2. Research Trend Analysis

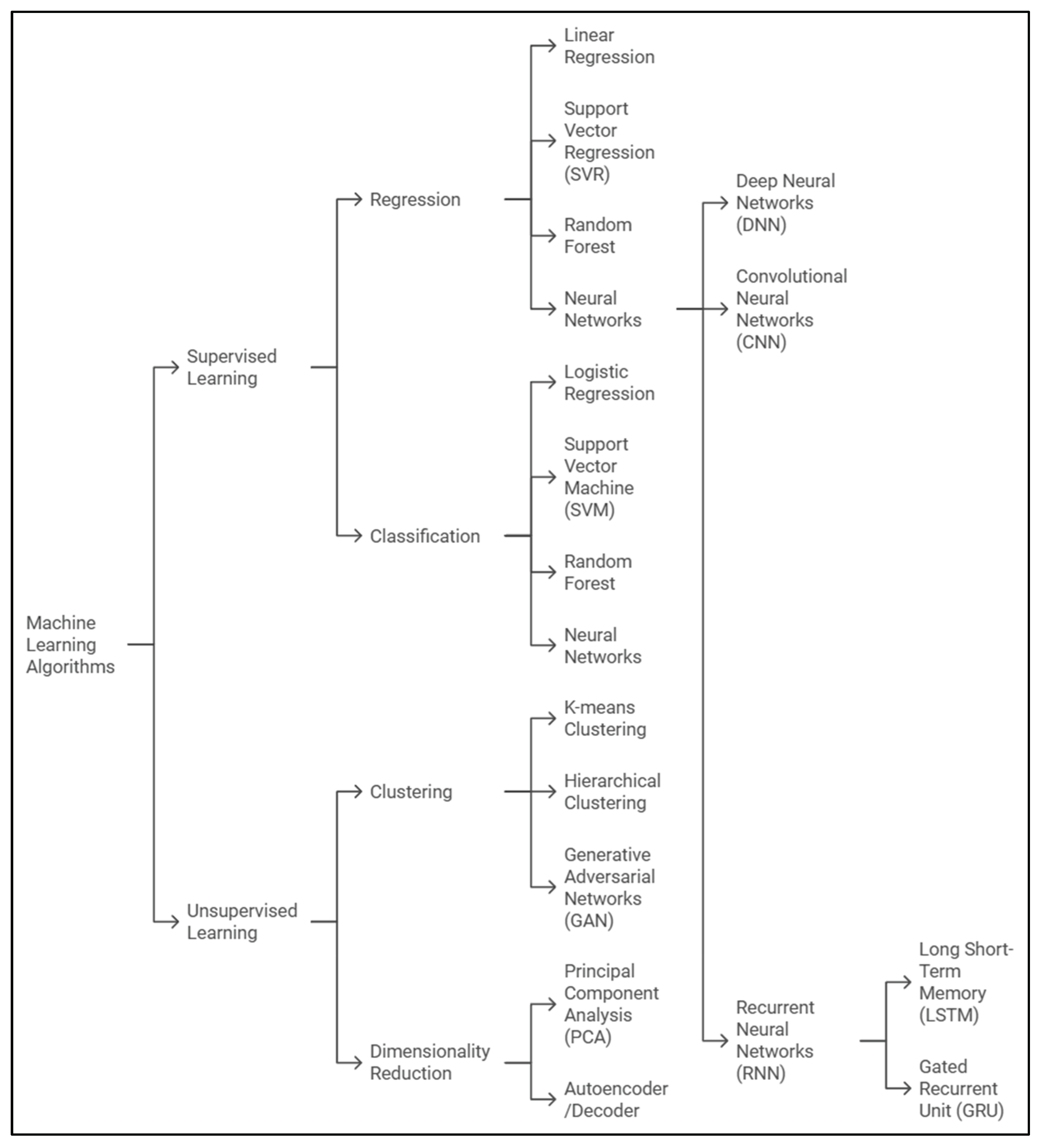

3. Overview of ML Models

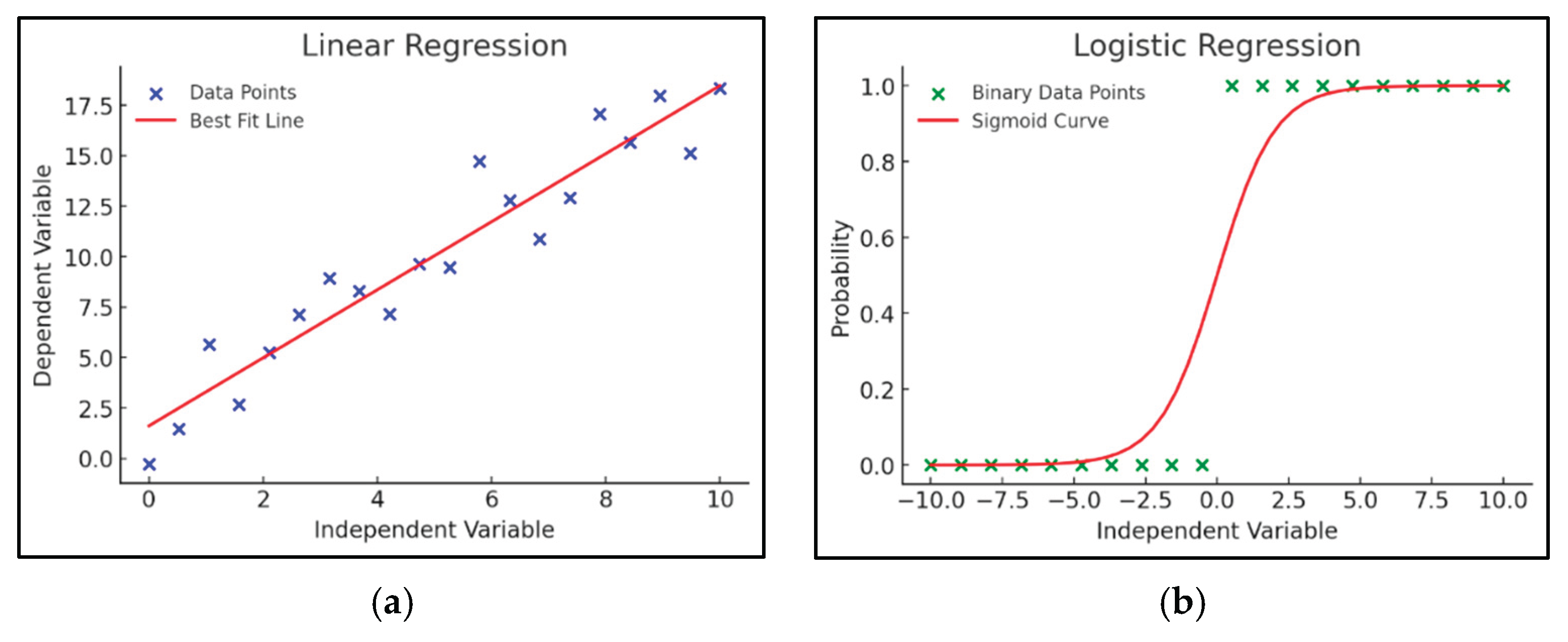

3.1. Regression-Based Algorithms: Linear and Polynomial Regression

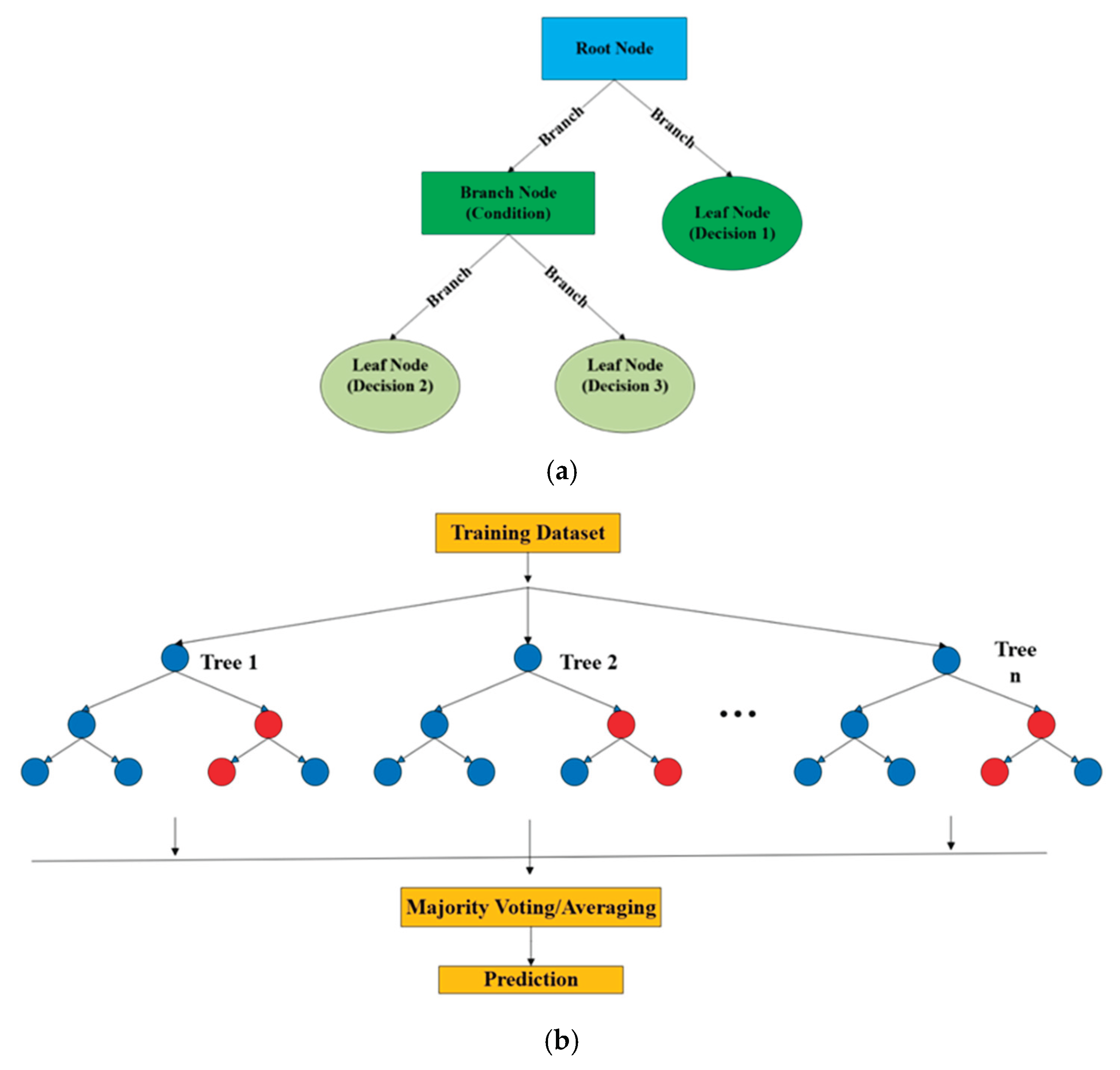

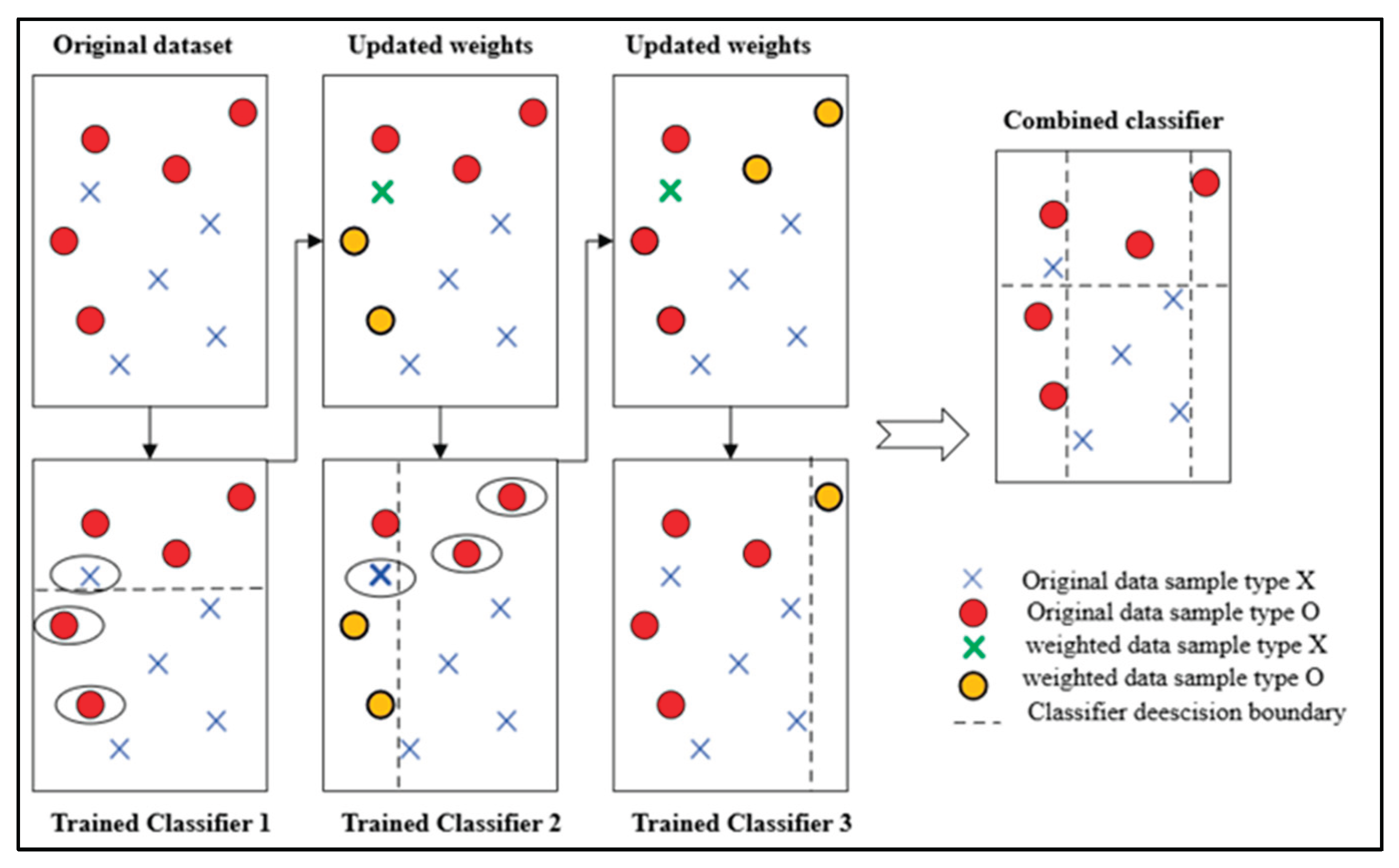

3.2. Ensemble Learning

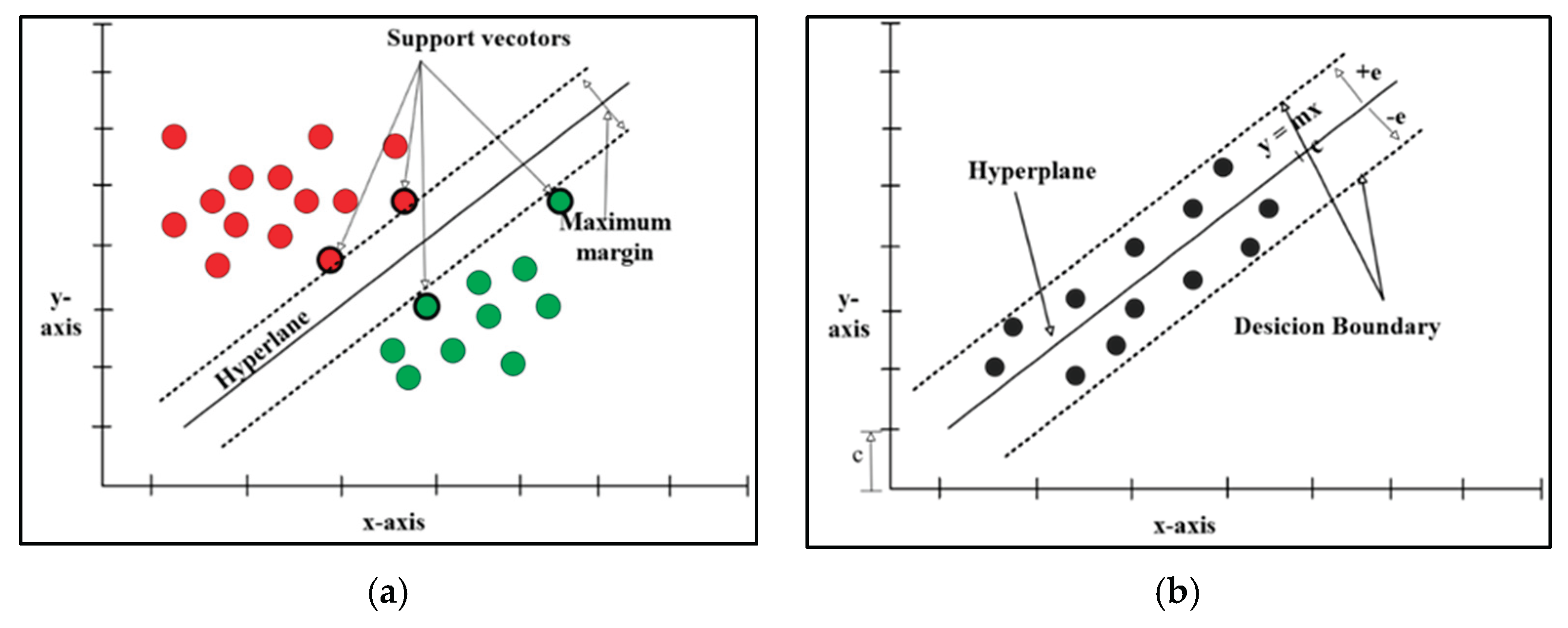

3.3. Support Vector Machine

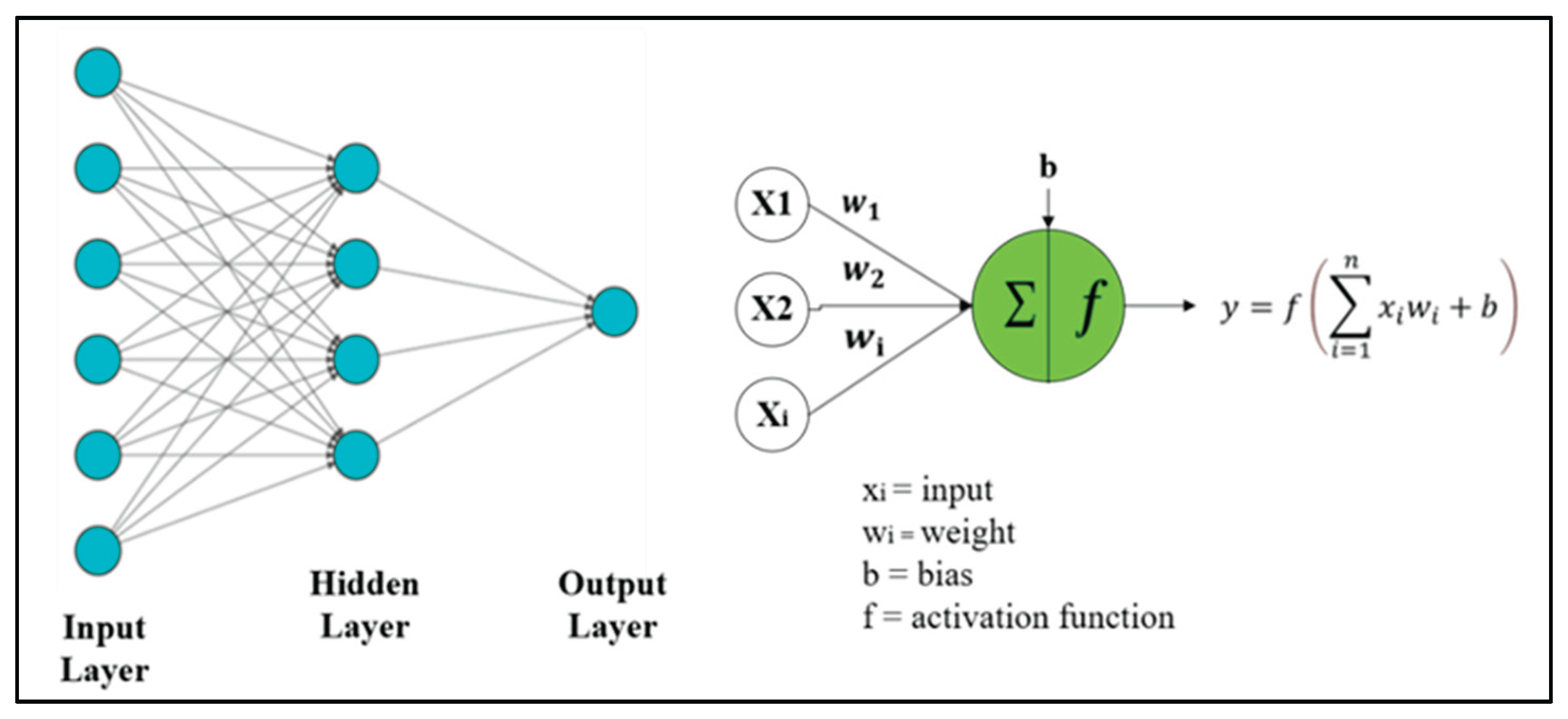

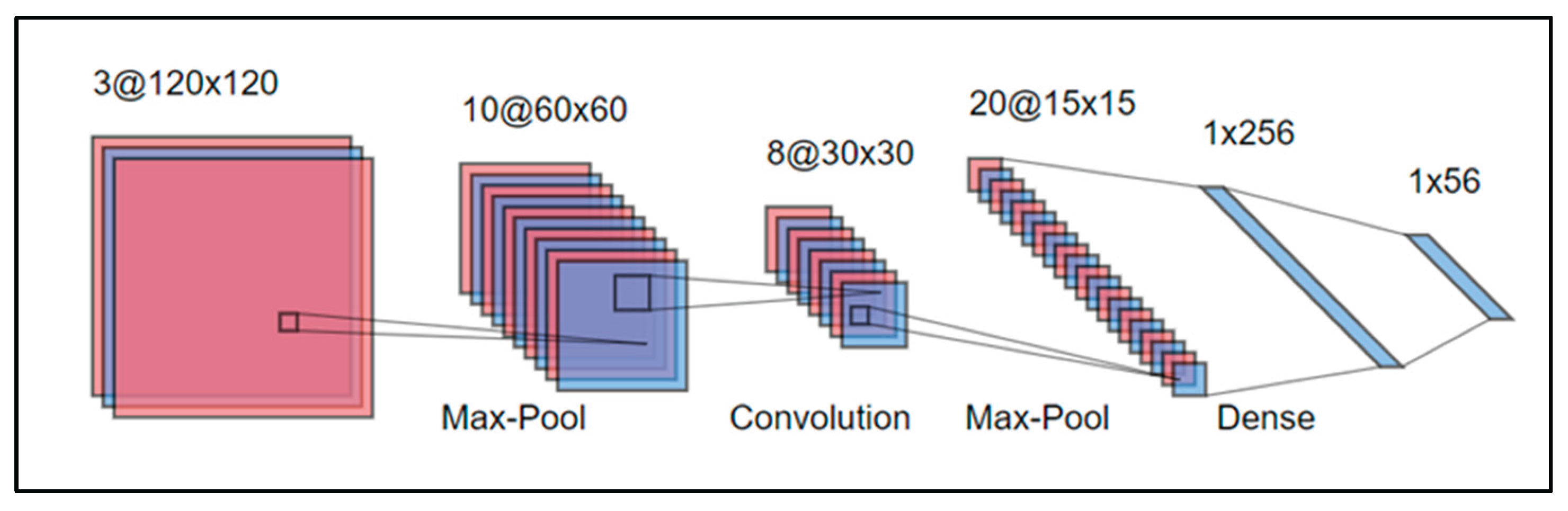

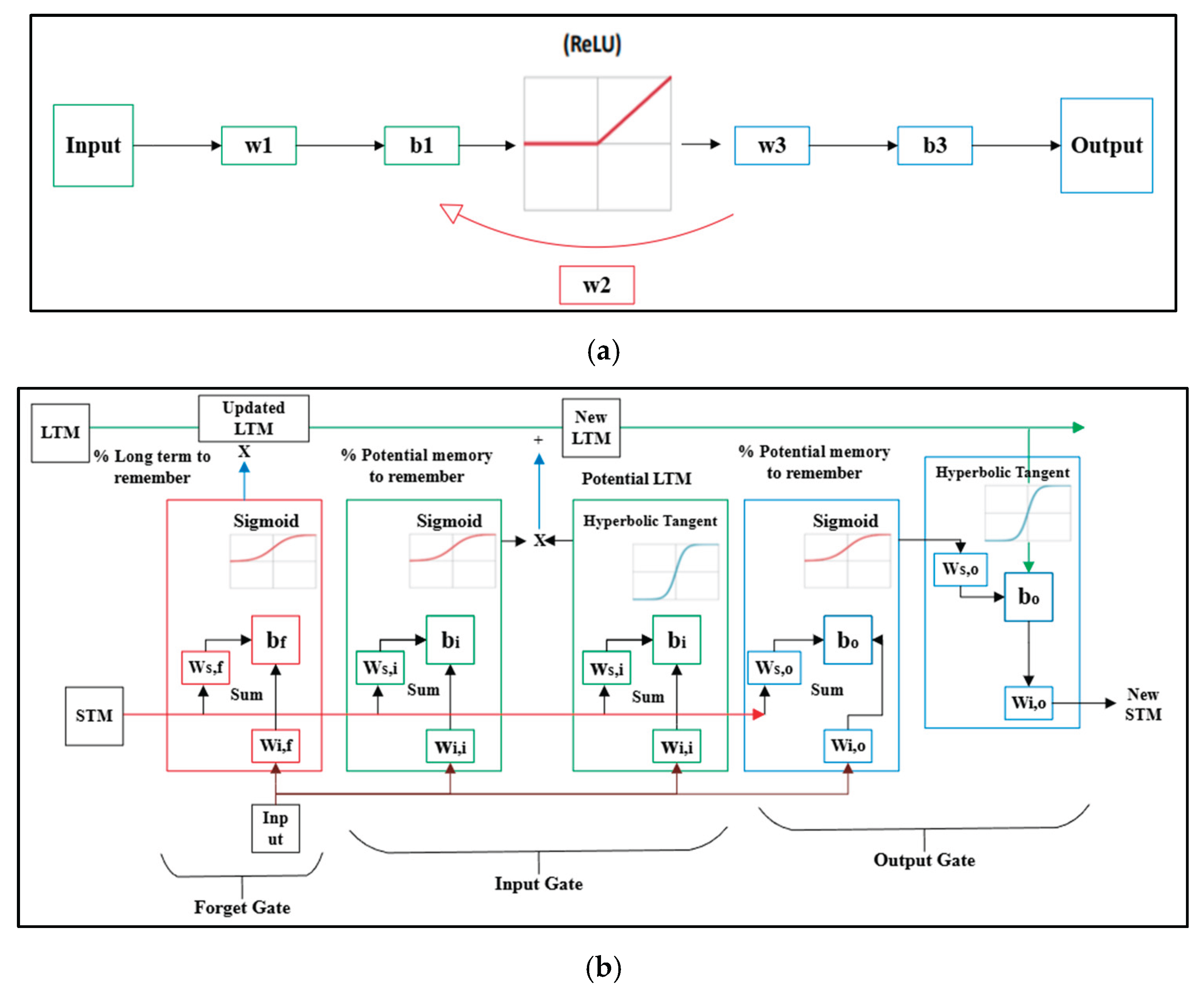

3.4. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and its Variants

4. Overview of ML Models

4.1. Failure Mode Identification & Capacity Prediction

| Reference | Data Samples | Output | ML Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deger and Taskin [25] | 384 RC Shear walls | backbone curve model parameters | GPR |

| Nguyen et al [48] | 369 RC Shear walls | Prediction of shear capacity | ANN |

| Zhang et al. [24] | 429 RC Shear walls | Prediction of failure modes and associated capacities | XGBoost, GB, RF |

| Horton et al. [38] | 1480 FE beam-column joints | Prediction of parameters in the modified Ibarra–Krawinkler (mIK) model for hysteresis. | DNN |

| Gao et al. [41] | 388 RC walls | Prediction of piecewise linear backbone curve | Genetic Programming-based symbolic regression (GP-SR) |

| Chen et al. [49] | 475 RC Columns | Prediction of backbone and cyclic deterioration parameters. | RF with Active Learning |

| Ma et al. [50] | 452 RC beams | Prediction of performance level limits considering crack development. | Seven Regression ML models |

| Haggag et al. [28] | 486 RC columns | Prediction of failure mode and ultimate capacity. | Decision Trees and Ensemble Techniques |

| Elgamel et al. [39] | 74 cyclically loaded (RCBSWs) | Prediction of the backbone curve of RCBSWs | Multigene Genetic Programming (MGGP) |

| Anwar et al. [40] | 216 cyclically loaded BCJs | Prediction of seismic shear strength of exterior beam-column joints (BCJs) | Mechanics guided data-driven model MGGP |

| Mangalathu and Jeon [31] | 536 RC BCJs | failure modes identification and shear strength prediction of BCJs. | Lasso Regression and RF |

| Mangalathu et al. [32] | 393 RC Shear Walls | To classify failure modes of RC shear walls | Naïve Bayes, K-NN, DT, RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost. |

| Yaghoubi et al. [26] | 161 rectangular shear walls. | To predict the equivalent damping ratio | LR, K-NN, Kernel Ridge Regression, SVR, and GPR |

4.2. Seismic Demand and Damage State Prediction

| References | Class of Structures |

|---|---|

| Kazemi et al [53], Zhang et al [102], Hwang et al [103], Chen & Guan [49], Aloisio et al [104] | RC MRFs |

| Nguyen et al [105], Bond et al [81], Kazemi et al [52], Samadian et al [106], Liu et al [107] | Steel MRFs |

| Coskun et al [108], Aloisio et al [104], Chalabi et al [109] | Masonry buildings |

| Nguyen et al [110], da Silva et al [111], Liao et al [112] | Base isolated buildings |

| Hu et al. [64] Zhang et al. [113] Zhang et al. [114] Hu et al.[115] Hu et al. [116] | Self-Centering Components |

| Yazdanpanah et al [117], Yi et al [118], Liao et al [119], Dai et al [120], Rezaei et al [121], Li et al [122], Todorov & Muntasir [123], Pang et al [124] | Bridges |

| Xing et al [125], Zhang et al [126], Wei et al [127], Zhao et al [128], Zhang et al [129], Xiang et al [130] | High-Speed Railway Bridges |

4.3. Seismic Response Time Series Prediction

5. Challenges and Opportunities

| References | ML Models | Links |

|---|---|---|

| Xu et al. 2022 [142] | RecursiveLSTM | https://github.com/xzk8559/RecursiveLSTM/tree/main/data |

| Chou et al. 2024 [143] | GraphLSTM | https://github.com/CMMAi/GraphLSTM-nonlinear-dynamic-analysis/tree/main/Data |

| Zhang et al. 2024 [144] Wen et al. 2022 [145] |

DNN CNN |

https://github.com/wenwp/StruNet_TH/tree/main/data |

| Mangalathu et al. 2020 [146] | Various ML Models with Active Learning | https://shorturl.at/79eyG |

| Zhang et al. 2020 [147] | PhyCNN | https://github.com/zhry10/PhyCNN/tree/master/data |

| Liu et al. 2025 [148] | rcGAN | https://github.com/Liujiming20/rcGAN/tree/main/NSGA |

| Tang et al. 2024 [149] | XGBoost | https://github.com/alan-dut/ResSMRF/blob/main/model.pkl |

| Kuo et al. 2024 [150] | GNN-LSTM-based Fusion Model | https://shorturl.at/jwq19 |

| Guo et al. 2023 [84] | Physics-DNN Hybridized Time-Stepper | https://github.com/JiaGuoLab/pdhi/tree/main |

| Zhong et al. 2023 [151] | EE-UQ software | https://shorturl.at/TP7UK |

| Zhang et al. 2019 [152] | DeepLSTM | https://github.com/zhry10/DeepLSTM/tree/master/data |

| Gentile et al. 2022 [153] | Gaussian process regression | https://github.com/robgen/surrogatedPSDM/tree/main |

| Mangalathu et al. 2020 [32] | KNN, DT, RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost, Light GBM, CatBoost | https://github.com/sujithmangalathu/Shear-Wall-Failure-Mode/tree/master |

| AswinVishnu | ANN | https://shorturl.at/3PYA8 |

| Sheny | RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost, Light GBM | https://shorturl.at/HPtd9 |

| Eugene Denteh | XGBOOST, Light GBM, RF, AdaBoost | https://github.com/EugeneDenteh/Machine_Learning_model_for_the_failure_mode_classification_of_R.C_columns/tree/main |

| Angarita et al. 2024 [154] | RF, ANN | ML-Pushover/ML_Models at main · carlosantr/ML-Pushover · GitHub |

| Yaghoubi et al. 2023 [26] | GPR | https://github.com/SiamakTY/ML-for-Equivalent-Damping-Ratio |

| Rayjada et al. 2023 [59] | GPR | https://github.com/Satwikpr/Backbone_GPR |

| Kourehpaz et al. 2022 [75] | K-Nearest neighbor, Decision Tree, RF, AdaBoost, GBM | https://shorturl.at/JIo9u |

6. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| MLP-NN | Multi-Layer Perceptron neural network |

| MDOF | Multi-degree of freedom system |

| GP-SR | Gaussian process-symbolic regression |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DNN | Deep learning |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| XGBoost | eXtreme gradient boost |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| RF | RF |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| GPR | Gaussian process regression |

| MGGP | Multi-gene gaussian process |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| DoF | Degree of freedom |

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| UD | Uniform dimensional |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| FCNN | Fully connected neural network |

| SHAP | sHapley additive explanation |

| GNN | Graph neural network |

| SRR | Seismic response reconstruction |

| SMA | Shape memory alloy |

| QDN | Quality-driven neural networks |

| MLS-SVMR | Multioutput-least squares support vector machine regression |

| RBS | Reduced beam section |

| DW-SVTR | Double-weighted support vector transfer regression |

| MIDR | Maximum inter-story drift |

| NLTHA | Nonlinear time history analysis |

| LHS | Latin hypercube sampling |

| PLLS | Piecewise linear least squares |

| FEM | Finite element modeling |

| NARX-NN | Nonlinear autoregressive exogenous neural network |

| m-BWBN | Modified bouc-wen-baber-noori model |

| rcGAN | Recurrent conditional generative adversarial network |

| RMSE | Root mean-squared error |

| RC COL | Reinforce Concrete Column |

| RC SW | Reinforce Concrete Shear wall |

| BCJ | Beam-Column Joint |

| RBS | Reduced Beam Section |

References

- UNDP. Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, Reducing disaster risk: a challenge for development: a global report / United Nations Development Programme, Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, 2004.

- P.K.V.R. Padalu, M. Surana, An Overview of Performance-Based Seismic Design Framework for Reinforced Concrete Frame Buildings, Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering 48 (2024) 635–667. [CrossRef]

- T.J. Sullivan, D.P. Welch, G.M. Calvi, Simplified seismic performance assessment and implications for seismic design, Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration 13 (2014) 95–122. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Mwafy, A.S. Elnashai, Static pushover versus dynamic collapse analysis of RC buildings, Eng Struct 23 (2001) 407–424. [CrossRef]

- I.H. Sarker, Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions, SN Comput Sci 2 (2021) 160. [CrossRef]

- A. Afshar, G. Nouri, S. Ghazvineh, S.H. Hosseini Lavassani, Machine-Learning Applications in Structural Response Prediction: A Review, Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction 29 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, Deep Learning in Earthquake Engineering: A Comprehensive Review, 2024.

- F. Soleimani, D. Hajializadeh, State-of-the-Art Review on Probabilistic Seismic Demand Models of Bridges: Machine-Learning Application, Infrastructures (Basel) 7 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, H. V. Burton, H. Huang, Machine learning applications for building structural design and performance assessment: State-of-the-art review, Journal of Building Engineering 33 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J.C. Jimenez, O.G. Dela Cruz, Machine Learning for Seismic Vulnerability Assessment: A Review, in: Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2024: pp. 177–187. [CrossRef]

- H.T. Thai, Machine learning for structural engineering: A state-of-the-art review, Structures 38 (2022) 448–491. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, M. Ebad Sichani, J.E. Padgett, R. DesRoches, The promise of implementing machine learning in earthquake engineering: A state-of-the-art review, Earthquake Spectra 36 (2020) 1769–1801. [CrossRef]

- N.J. van Eck, L. Waltman, Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping, Scientometrics 84 (2010) 523–538. [CrossRef]

- V.K. Singh, P. Singh, M. Karmakar, J. Leta, P. Mayr, The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis, Scientometrics 126 (2021) 5113–5142. [CrossRef]

- N.R. Draper, H. Smith, Applied Regression Analysis, Wiley, 1998. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, Z. Yu, W. Cao, Y. Shi, Q. Ma, A survey on ensemble learning, Front Comput Sci 14 (2020) 241–258. [CrossRef]

- J.H. Friedman, Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine., The Annals of Statistics 29 (2001). [CrossRef]

- V.N. Vapnik, The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory, Springer New York, New York, NY, 2000. [CrossRef]

- R.G. Brereton, G.R. Lloyd, Support Vector Machines for classification and regression, Analyst 135 (2010) 230–267. [CrossRef]

- S.N. Mahmoudi, L. Chouinard, Seismic fragility assessment of highway bridges using support vector machines, Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 14 (2016) 1571–1587. [CrossRef]

- J. Heaton, Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville: Deep learning, Genet Program Evolvable Mach 19 (2018) 305–307. [CrossRef]

- H. Dabiri, K. Rahimzadeh, A. Kheyroddin, A comparison of machine learning- and regression-based models for predicting ductility ratio of RC beam-column joints, Structures 37 (2022) 69–81. [CrossRef]

- T.G. Wakjira, M.S. Alam, U. Ebead, Plastic hinge length of rectangular RC columns using ensemble machine learning model, Eng Struct 244 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, X. Cheng, Y. Li, X. Du, Prediction of failure modes, strength, and deformation capacity of RC shear walls through machine learning, Journal of Building Engineering 50 (2022) 104145. [CrossRef]

- Z.T. Deger, G. Taskin, A novel GPR-based prediction model for cyclic backbone curves of reinforced concrete shear walls, Eng Struct 255 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S.T. Yaghoubi, Z.T. Deger, G. Taskin, F. Sutcu, Machine learning-based predictive models for equivalent damping ratio of RC shear walls, Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 21 (2023) 293–318. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangalathu, S.H. Hwang, J.S. Jeon, Failure mode and effects analysis of RC members based on machine-learning-based SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) approach, Eng Struct 219 (2020). [CrossRef]

- M. Haggag, M.K. Ismail, W. El-Dakhakhni, An interpretable machine learning approach for predicting the capacity and failure mode of reinforced concrete columns, Advances in Structural Engineering (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Cheng, B. Yu, Physics-based natural gradient boosting probabilistic prediction model for seismic failure modes of reinforced concrete columns, Structures 66 (2024) 106858. [CrossRef]

- P. Saha, S.C. Sapkota, S. Das, Prediction of Strength and Failure Modes in Reinforced Concrete Beam–Column Joints using Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques, Structural Engineering International (2024) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangalathu, J.S. Jeon, Classification of failure mode and prediction of shear strength for reinforced concrete beam-column joints using machine learning techniques, Eng Struct 160 (2018) 85–94. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangalathu, H. Jang, S.H. Hwang, J.S. Jeon, Data-driven machine-learning-based seismic failure mode identification of reinforced concrete shear walls, Eng Struct 208 (2020). [CrossRef]

- B.-L. Lai, R.-L. Bao, X.-F. Zheng, G. Vasdravellis, M. Mensinger, Machine-learning assisted analysis on the seismic performance of steel reinforced concrete composite columns, Structures 68 (2024) 107065. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Wu, R.-T. Wu, P.-H. Wang, T.-K. Lin, K.-C. Chang, Development of a high-fidelity failure prediction system for reinforced concrete bridge columns using generative adversarial networks, Eng Struct 286 (2023) 116130. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangalathu, J.-S. Jeon, Machine Learning–Based Failure Mode Recognition of Circular Reinforced Concrete Bridge Columns: Comparative Study, Journal of Structural Engineering 145 (2019).

- R. Mo, L. Chen, Y. Chen, C. Xiong, C. Zhang, Z. Chen, E. Lin, Prediction and correlations estimation of seismic capacities of pier columns: Extended Gaussian process regression models, Structural Safety 109 (2024) 102457. [CrossRef]

- A. Djerrad, Y. Zhou, S. Meng, Efficient deep learning based models for rapid prediction of RC shear wall responses under monotonic and cyclic loading, Journal of Building Engineering 98 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T.A. Horton, I. Hajirasouliha, B. Davison, Z. Ozdemir, Accurate prediction of cyclic hysteresis behaviour of RBS connections using Deep Learning Neural Networks, Eng Struct 247 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Elgamel, M.K. Ismail, A. Ashour, W. El-Dakhakhni, Backbone model for reinforced concrete block shear wall components and systems using controlled multigene genetic programming, Eng Struct 274 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M.M. Anwar, M.K. Ismail, H.A. Hodhod, W. El-Dakhakhni, H.H.A. Ibrahim, Mechanics guided data-driven model for seismic shear strength of exterior beam-column joints, Structures 69 (2024). [CrossRef]

- G. Ma, Y. Wang, H.J. Hwang, Genetic programming-based backbone curve model of reinforced concrete walls, Eng Struct 283 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, A. Guo, Empirical-based support vector machine method for seismic assessment and simulation of reinforced concrete columns using historical cyclic tests, Eng Struct 237 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, S.G. Paal, Machine Learning–Based Backbone Curve Model of Reinforced Concrete Columns Subjected to Cyclic Loading Reversals, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 32 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Z.T. Deger, G. Taskin, A novel GPR-based prediction model for cyclic backbone curves of reinforced concrete shear walls, Eng Struct 255 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P.Y. Chen, K.C. Lee, T.L. Li, Prediction of parameters in the Ibarra–Medina–Krawinkler model for reinforced concrete columns using random forest and active learning, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 185 (2024). [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, Y. Park, S. Mangalathu, J.-S. Jeon, Effect of data drift on the performance of machine-learning models: Seismic damage prediction for aging bridges, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn (2024). [CrossRef]

- J.G. Xu, W. Hong, J. Zhang, S.T. Hou, G. Wu, Seismic performance assessment of corroded RC columns based on data-driven machine-learning approach, Eng Struct 255 (2022). [CrossRef]

- D.D. Nguyen, V.L. Tran, D.H. Ha, V.Q. Nguyen, T.H. Lee, A machine learning-based formulation for predicting shear capacity of squat flanged RC walls, Structures 29 (2021) 1734–1747. [CrossRef]

- P.Y. Chen, X. Guan, A multi-source data-driven approach for evaluating the seismic response of non-ductile reinforced concrete moment frames, Eng Struct 278 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Ma, J.-W. Chi, F.-C. Kong, S.-H. Zhou, D.-C. Lu, W.-Z. Liao, Prediction on the seismic performance limits of reinforced concrete columns based on machine learning method, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 177 (2024). [CrossRef]

- W. Xu, Y. Zhao, W. Yang, D. Yu, Y. Zhao, Seismic fragility analysis of RC frame structures based on IDA analysis and machine learning, Structures 65 (2024). [CrossRef]

- F. Kazemi, N. Asgarkhani, R. Jankowski, Predicting seismic response of SMRFs founded on different soil types using machine learning techniques, Eng Struct 274 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Kazemi, N. Asgarkhani, R. Jankowski, Machine learning-based seismic fragility and seismic vulnerability assessment of reinforced concrete structures, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 166 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Qian, Y. Dong, Surrogate-assisted seismic performance assessment incorporating vine copula captured dependence, Eng Struct 257 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiong, Q. Kong, C. Yuan, Y. Li, K. Ji, H. Xiong, Fusing physics-based and machine learning models for rapid ground-motion-adaptative probabilistic seismic fragility assessment, Journal of Building Engineering 87 (2024) 108938. [CrossRef]

- S. Bhatta, J. Dang, Machine Learning-Based Classification for Rapid Seismic Damage Assessment of Buildings at a Regional Scale, Journal of Earthquake Engineering 28 (2024) 1861–1891. [CrossRef]

- K. Kostinakis, K. Morfidis, K. Demertzis, L. Iliadis, Classification of buildings’ potential for seismic damage using a machine learning model with auto hyperparameter tuning, Eng Struct 290 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Ding, D.C. Feng, E. Brunesi, F. Parisi, G. Wu, Efficient seismic fragility analysis method utilizing ground motion clustering and probabilistic machine learning, Eng Struct 294 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S.P. Rayjada, M. Raghunandan, J. Ghosh, Machine learning-based RC beam-column model parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification for seismic fragility assessment, Eng Struct 278 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Gao, H. Hou, L. Huang, G. Yu, C. Chen, Evaluation of Kriging-NARX Modeling for Uncertainty Quantification of Nonlinear SDOF Systems with Degradation, International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 21 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Kundu, S. Ghosh, S. Chakraborty, A long short-term memory based deep learning algorithm for seismic response uncertainty quantification, Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics 67 (2022) 103189. [CrossRef]

- M. Noureldin, T. Abuhmed, M. Saygi, J. Kim, Explainable probabilistic deep learning framework for seismic assessment of structures using distribution-free prediction intervals, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 38 (2023) 1677–1698. [CrossRef]

- A. Delaviz, S. Yaghmaei-Sabegh, Development of a new framework based on Gaussian regression process for rapid fragility analysis of 2-DoF base-isolated structures, Structures 53 (2023) 1135–1149. [CrossRef]

- S. Hu, S. Zhu, W. Wang, Machine learning-driven probabilistic residual displacement-based design method for improving post-earthquake repairability of steel moment-resisting frames using self-centering braces, Journal of Building Engineering 61 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M.H. Soleimani-Babakamali, M. Zaker Esteghamati, Estimating seismic demand models of a building inventory from nonlinear static analysis using deep learning methods, Eng Struct 266 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Pang, X. Zhou, W. He, J. Zhong, O. Hui, Uniform Design–Based Gaussian Process Regression for Data-Driven Rapid Fragility Assessment of Bridges, Journal of Structural Engineering 147 (2021).

- T. Kim, J. Song, O.S. Kwon, Probabilistic evaluation of seismic responses using deep learning method, Structural Safety 84 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Latif, M. Surana, A. Banerjee, Effects of material properties uncertainty on seismic fragility of reinforced-concrete frames using machine learning approach, Journal of Building Engineering 86 (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, L. Xu, X. Xie, A Convolutional Neural Networks Model Based on Wavelet Packet Transform for Enhanced Earthquake Early Warning, International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics (2024). [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang, Y. Li, Y. Lin, H. Jiang, Time-Frequency Feature-Based Seismic Response Prediction Neural Network Model for Building Structures, Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Lu, Y. Xu, Y. Tian, B. Cetiner, E. Taciroglu, A deep learning approach to rapid regional post-event seismic damage assessment using time-frequency distributions of ground motions, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 50 (2021) 1612–1627. [CrossRef]

- H.S. Park, S.H. Yoo, D.Y. Yun, B.K. Oh, Investigation on employment of time and frequency domain data for predicting nonlinear seismic responses of structures, Structures 61 (2024). [CrossRef]

- W.-J. Tang, D.-S. Wang, J.-C. Dai, L. Tong, Z.-G. Sun, Deep Learning Frequency Loss Functions for Predicting the Seismic Responses of Structures, International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Dang-Vu, Q.D. Nguyen, T. Chung, J. Shin, K. Lee, Frequency-based Data-driven Surrogate Model for Efficient Prediction of Irregular Structure’s Seismic Responses, Journal of Earthquake Engineering 26 (2022) 7319–7336. [CrossRef]

- P. Kourehpaz, C. Molina Hutt, Machine Learning for Enhanced Regional Seismic Risk Assessments, Journal of Structural Engineering 148 (2022).

- Y. Xu, X. Lu, B. Cetiner, E. Taciroglu, Real-time regional seismic damage assessment framework based on long short-term memory neural network, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 36 (2021) 504–521. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, L. Xu, X. Xie, G. Zhang, Improvement of the seismic resilience of regional buildings: A multi-objective prediction model for earthquake early warning, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 179 (2024). [CrossRef]

- R. Falcone, A. Ciaramella, F. Carrabs, N. Strisciuglio, E. Martinelli, Artificial neural network for technical feasibility prediction of seismic retrofitting in existing RC structures, Structures 41 (2022) 1220–1234. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, Y. Liu, H. Sun, Physics-guided convolutional neural network (PhyCNN) for data-driven seismic response modeling, Eng Struct 215 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, S. Meng, Y. Lou, Q. Kong, Physics-Informed Deep Learning-Based Real-Time Structural Response Prediction Method, Engineering 35 (2024) 140–157. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Bond, P. Ren, J.F. Hajjar, H. Sun, Physics-informed machine learning for seismic response prediction of nonlinear steel moment resisting frame structures, n.d.

- S.Z. Chen, D.C. Feng, E. Taciroglu, Prior knowledge-infused neural network for efficient performance assessment of structures through few-shot incremental learning, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 39 (2024) 1928–1945. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiong, Q. Kong, H. Xiong, L. Liao, C. Yuan, Physics-informed deep 1D CNN compiled in extended state space fusion for seismic response modeling, Comput Struct 291 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, R. Enokida, D. Li, K. Ikago, Combination of physics-based and data-driven modeling for nonlinear structural seismic response prediction through deep residual learning, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 52 (2023) 2429–2451. [CrossRef]

- F. Mokhtari, A. Imanpour, Hybrid data-driven and physics-based simulation technique for seismic analysis of steel structural systems, Comput Struct 295 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, W. Guo, Z. Xu, C. Shi, Physics knowledge-based transfer learning between buildings for seismic response prediction, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 177 (2024). [CrossRef]

- M. Zaker Esteghamati, M.M. Flint, Do all roads lead to Rome? A comparison of knowledge-based, data-driven, and physics-based surrogate models for performance-based early design, Eng Struct 286 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M. Raissi, P. Perdikaris, G.E. Karniadakis, Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations, J Comput Phys 378 (2019) 686–707. [CrossRef]

- S. Sadeghi Eshkevari, M. Takáč, S.N. Pakzad, M. Jahani, DynNet: Physics-based neural architecture design for nonlinear structural response modeling and prediction, Eng Struct 229 (2021). [CrossRef]

- W. Liao, X. Wang, Y. Fei, Y. Huang, L. Xie, X. Lu, Base-isolation design of shear wall structures using physics-rule-co-guided self-supervised generative adversarial networks, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 52 (2023) 3281–3303. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, Y. Lei, J. Wang, H. Zhu, W. Shen, Physics-enhanced machine learning-based optimization of tuned mass damper parameters for seismically-excited buildings, Eng Struct 292 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S.S. Parida, S. Bose, M. Butcher, G. Apostolakis, P. Shekhar, SVD enabled data augmentation for machine learning based surrogate modeling of non-linear structures, Eng Struct 280 (2023) 115600. [CrossRef]

- Q. Cheng, A. Li, H. Ren, C.C. Por, W. Liao, L. Xie, Rapid seismic-damage assessment method for buildings on a regional scale based on spectrum-compatible data augmentation and deep learning, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 178 (2024). [CrossRef]

- P. Martakis, Y. Reuland, M. Imesch, E. Chatzi, Reducing uncertainty in seismic assessment of multiple masonry buildings based on monitored demolitions, Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 20 (2022) 4441–4482. [CrossRef]

- F. Ghahari, D. Swensen, H. Haddadi, E. Taciroglu, A hybrid model-data method for seismic response reconstruction of instrumented buildings, Earthquake Spectra 40 (2024) 1235–1268. [CrossRef]

- E. Abdelmalek-Lee, H. Burton, A dual Kriging-XGBoost model for reconstructing building seismic responses using strong motion data, Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 22 (2024) 3563–3589. [CrossRef]

- B. Ahmed, S. Mangalathu, J.S. Jeon, Generalized stacked LSTM for the seismic damage evaluation of ductile reinforced concrete buildings, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 52 (2023) 3477–3503. [CrossRef]

- B. Ahmed, S. Mangalathu, J.S. Jeon, Seismic damage state predictions of reinforced concrete structures using stacked long short-term memory neural networks, Journal of Building Engineering 46 (2022). [CrossRef]

- W.-J. Tang, D.-S. Wang, H.-B. Huang, J.-C. Dai, F. Shi, A Pre-Trained Deep Learning Model for Fast Online Prediction of Structural Seismic Responses, International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 24 (2024). [CrossRef]

- K. Zhong, J.G. Navarro, S. Govindjee, G.G. Deierlein, Surrogate modeling of structural seismic response using probabilistic learning on manifolds, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 52 (2023) 2407–2428. [CrossRef]

- S. Jiao, H. Hou, D. Ran, C. Chen, X. Zeng, M. Gao, F. Xiong, Adaptive sequential sampling Kriging method and its application in incremental dynamic analysis, World Earthquake Engineering 38 (2022) 218–228. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, W. Wen, C. Zhai, J. Jia, B. Zhou, Structural nonlinear seismic time-history response prediction of urban-scale reinforced concrete frames based on deep learning, Eng Struct 317 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S.H. Hwang, S. Mangalathu, J. Shin, J.S. Jeon, Machine learning-based approaches for seismic demand and collapse of ductile reinforced concrete building frames, Journal of Building Engineering 34 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Aloisio, Y.D. Santis, F. Irti, D.P. Pasca, L. Scimia, M. Fragiacomo, Machine learning predictions of code-based seismic vulnerability for reinforced concrete and masonry buildings: Insights from a 300-building database, Eng Struct 301 (2024). [CrossRef]

- H.D. Nguyen, N.D. Dao, M. Shin, Prediction of seismic drift responses of planar steel moment frames using artificial neural network and extreme gradient boosting, Eng Struct 242 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Samadian, I.B. Muhit, A. Occhipinti, N. Dawood, Surrogate models for seismic and pushover response prediction of steel special moment resisting frames, Eng Struct 314 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, L. Duan, Y. Jiang, L. Zhao, J. Zhao, A rcGAN-based surrogate model for nonlinear seismic response analysis and optimization of steel frames, Eng Struct 323 (2025). [CrossRef]

- O. Coskun, R. Aktepe, A. Aldemir, A.E. Yilmaz, M. Durmaz, B.G. Erkal, E. Tunali, Seismic risk prioritization of masonry building stocks using machine learning, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 53 (2024) 4432–4450. [CrossRef]

- R. Chalabi, O. Yazdanpanah, K.M. Dolatshahi, Nonmodel rapid seismic assessment of eccentrically braced frames incorporating masonry infills using machine learning techniques, Journal of Building Engineering 79 (2023). [CrossRef]

- H.D. Nguyen, N.D. Dao, M. Shin, Machine learning-based prediction for maximum displacement of seismic isolation systems, Journal of Building Engineering 51 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A.H.A. da Silva, D.P. Pohl, B. Stojadinović, Displacement prediction equations for seismic design of single friction pendulum base-isolated structures, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 53 (2024) 3880–3903. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liao, H. Tang, R. Li, L. Ran, L. Xie, Seismic response prediction and parameters estimation of the frame structure equipped with the base isolation-fluid inerter system (FS-BIFI) based on the PI-LSTM model, Eng Struct 309 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, Y. Chen, C. Zhang, G. Xue, J. Zhang, M. Zhang, L. Wang, N. Li, Prediction of seismic acceleration response of precast segmental self-centering concrete filled steel tube single-span bridges based on machine learning method, Eng Struct 279 (2023). [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, S. Hu, W. Wang, Probabilistic residual displacement-based design for enhancing seismic resilience of BRBFs using self-centering braces, Eng Struct 295 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Hu, M.S. Alam, Probabilistic Nonlinear Displacement Ratio Prediction of Self-centering Energy-absorbing Dual Rocking Core System under Near-fault Ground Motions Using Machine Learning, Journal of Earthquake Engineering 27 (2023) 488–519. [CrossRef]

- S. Hu, S. Zhu, M. Shahria Alam, W. Wang, Machine learning-aided peak and residual displacement-based design method for enhancing seismic performance of steel moment-resisting frames by installing self-centering braces, Eng Struct 271 (2022). [CrossRef]

- O. Yazdanpanah, M. Chang, M. Park, C.-Y. Kim, Seismic response prediction of RC bridge piers through stacked long short-term memory network, Structures 45 (2022) 1990–2006. [CrossRef]

- R. Yi, X. Li, S. Zhu, Y. Li, X. Xu, A deep leaning method for dynamic vibration analysis of bridges subjected to uniform seismic excitation, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 168 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Liao, R. Lin, R. Zhang, G. Wu, Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM) neural network for Seismic Response Modeling of Bridges, Comput Struct 275 (2023). [CrossRef]

- L. Dai, W. Zhang, S. Tian, Convolutional neural network estimation of bridge linear elastic seismic response, Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Dynamics 41 (2021) 188–195. [CrossRef]

- H. Rezaei, P. Zarfam, E.M. Golafshani, G.G. Amiri, Seismic fragility analysis of RC box-girder bridges based on symbolic regression method, Structures 38 (2022) 306–322. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, H. Li, X. Chen, Fast seismic response estimation of tall pier bridges based on deep learning techniques, Eng Struct 266 (2022). [CrossRef]

- B. Todorov, A.H.M. Muntasir Billah, Machine learning driven seismic performance limit state identification for performance-based seismic design of bridge piers, Eng Struct 255 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Pang, X. Zhou, W. He, J. Zhong, O. Hui, Uniform Design–Based Gaussian Process Regression for Data-Driven Rapid Fragility Assessment of Bridges, Journal of Structural Engineering 147 (2021).

- C. Xing, Z. Xu, H. Wang, Structural seismic responses prediction using the gradient-enhanced hybrid PINN, Advances in Structural Engineering 27 (2024) 1962–1970. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, X. Xie, H. Zhao, Z. Shao, B. Wang, Q. Han, Y. Pan, P. Xiang, Seismic response prediction method of train-bridge coupled system based on convolutional neural network-bidirectional long short-term memory-attention modeling, Advances in Structural Engineering (2024). [CrossRef]

- B. Wei, X. Zheng, L. Jiang, Z. Lai, R. Zhang, J. Chen, Z. Yang, Seismic response prediction and fragility assessment of high-speed railway bridges using machine learning technology, Structures 66 (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, B. Wei, P. Zhang, P. Guo, Z. Shao, S. Xu, L. Jiang, H. Hu, Y. Zeng, P. Xiang, Safety analysis of high-speed trains on bridges under earthquakes using a LSTM-RNN-based surrogate model, Comput Struct 294 (2024). [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang, H. Zhao, Z. Shao, L. Jiang, H. Hu, Y. Zeng, P. Xiang, A rapid analysis framework for seismic response prediction and running safety assessment of train-bridge coupled systems, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 177 (2024). [CrossRef]

- P. Xiang, X. Peng, X. Xie, H. Zhao, Z. Shao, Z. Liu, Y. Chen, P. Zhang, Adaptive GN block-based model for seismic response prediction of train-bridge coupled systems, Structures 66 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, H. Li, M. Noori, R. Ghiasi, S.-C. Kuok, W.A. Altabey, Seismic response prediction of structures based on Runge-Kutta recurrent neural network with prior knowledge, Eng Struct 279 (2023) 115576. [CrossRef]

- C. Ning, Y. Xie, L. Sun, LSTM, WaveNet, and 2D CNN for nonlinear time history prediction of seismic responses, Eng Struct 286 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Z. Yin, H. Zhang, W. Geng, Prediction of nonlinear seismic response of underground structures in single- and multi-layered soil profiles using a deep gated recurrent network, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 168 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiong, Q. Kong, H. Xiong, L. Liao, C. Yuan, Physics-informed deep 1D CNN compiled in extended state space fusion for seismic response modeling, Comput Struct 291 (2024). [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, L. Meng, ; Zhu Mao, H. Sun, A.M. Asce, Spatiotemporal Deep Learning for Bridge Response Forecasting, (2021).

- H. Peng, J. Yan, Y. Yu, Y. Luo, Time series estimation based on deep Learning for structural dynamic nonlinear prediction, Structures 29 (2021) 1016–1031. [CrossRef]

- O. Yazdanpanah, M. Chang, M. Park, C.Y. Kim, Seismic response prediction of RC bridge piers through stacked long short-term memory network, Structures 45 (2022) 1990–2006. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liao, R. Lin, R. Zhang, G. Wu, Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM) neural network for Seismic Response Modeling of Bridges, Comput Struct 275 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Q. Cheng, A. Li, H. Ren, C.C. Por, W. Liao, L. Xie, Rapid seismic-damage assessment method for buildings on a regional scale based on spectrum-compatible data augmentation and deep learning, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 178 (2024). [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, Y. Liu, H. Sun, Physics-informed multi-LSTM networks for metamodeling of nonlinear structures, Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 369 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S.P. Rayjada, M. Raghunandan, J. Ghosh, Machine learning-based RC beam-column model parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification for seismic fragility assessment, Eng Struct 278 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, J. Chen, J. Shen, M. Xiang, Recursive long short-term memory network for predicting nonlinear structural seismic response, Eng Struct 250 (2022) 113406. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chou, P. Kuo, K. Li, W. Chang, Y. Huang, C. Chen, Inductive graph-based long short-term memory network for the prediction of nonlinear floor responses and member forces of steel buildings subjected to orthogonal horizontal ground motions, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn (2024). [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, W. Wen, C. Zhai, J. Jia, B. Zhou, Structural nonlinear seismic time-history response prediction of urban-scale reinforced concrete frames based on deep learning, Eng Struct 317 (2024) 118702. [CrossRef]

- W. Wen, C. Zhang, C. Zhai, Rapid seismic response prediction of RC frames based on deep learning and limited building information, Eng Struct 267 (2022) 114638. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangalathu, J.-S. Jeon, Regional Seismic Risk Assessment of Infrastructure Systems through Machine Learning: Active Learning Approach, Journal of Structural Engineering 146 (2020).

- R. Zhang, Y. Liu, H. Sun, Physics-guided convolutional neural network (PhyCNN) for data-driven seismic response modeling, Eng Struct 215 (2020) 110704. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, L. Duan, Y. Jiang, L. Zhao, J. Zhao, A rcGAN-based surrogate model for nonlinear seismic response analysis and optimization of steel frames, Eng Struct 323 (2025) 119199. [CrossRef]

- Q. Tang, Y. Cui, J. Jia, Machine learning-based surrogate resilience modeling for preliminary seismic design, Journal of Building Engineering 98 (2024) 111226. [CrossRef]

- P.-C. Kuo, Y.-T. Chou, K.-Y. Li, W.-T. Chang, Y.-N. Huang, C.-S. Chen, GNN-LSTM-based fusion model for structural dynamic responses prediction, Eng Struct 306 (2024) 117733. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhong, J.G. Navarro, S. Govindjee, G.G. Deierlein, Surrogate modeling of structural seismic response using probabilistic learning on manifolds, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 52 (2023) 2407–2428. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, Z. Chen, S. Chen, J. Zheng, O. Büyüköztürk, H. Sun, Deep long short-term memory networks for nonlinear structural seismic response prediction, Comput Struct 220 (2019) 55–68. [CrossRef]

- R. Gentile, C. Galasso, Surrogate probabilistic seismic demand modelling of inelastic single-degree-of-freedom systems for efficient earthquake risk applications, Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 51 (2022) 492–511. [CrossRef]

- C. Angarita, C. Montes, O. Arroyo, Machine learning – based approach for predicting pushover curves of low-rise reinforced concrete frame buildings, Structures 70 (2024). [CrossRef]

| References | Titles |

|---|---|

| Afshar et al. 2024 [6] | Machine-Learning Applications in Structural Response Prediction: A Review |

| Xie 2024 [7] | Deep Learning in Earthquake Engineering: A Comprehensive Review |

| Soleimani et al. 2022 [8] | State-of-the-Art Review on Probabilistic Seismic Demand Models of Bridges: Machine-Learning Application |

| Sun et al. 2021 [9] | Machine learning applications for building structural design and performance assessment: State-of-the-art review |

| Jimenez et al. 2024 [10] | Machine Learning for Seismic Vulnerability Assessment: A Review |

| Thai 2022 [11] | Machine learning for structural engineering: A state-of-the-art review |

| Xie et al. 2020 [12] | The promise of implementing machine learning in earthquake engineering: A state-of-the-art review |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).