1. Introduction

For decades, bone healing strategies have primarily relied on alloy-based prosthetics to replace hard tissues [

2]. Numerous efforts have been made to address the inherent challenges associated with rigid prosthetic implants, such as fretting [

3] and stress-shielding [

4], by employing structural design strategies that retain a stiff core [

5]. However, recent advancements in tissue engineering have shifted focus from replacement to regeneration of tissues.

Despite the remarkable resilience of bone, external support becomes essential for healing when the fracture gap exceeds one millimeter [

6]. Nowadays, bone tissue engineering approaches involve the use of phosphocalcic ceramics bulk pieces or injectable composite that mimic a natural bone environment to facilitate bone regeneration [

7,

8]. Bone-forming cells then deposit extracellular matrix on the surface of the scaffold. Healing should be as rapid and complete as possible, ending when the regenerated tissue becomes indistinguishable from the original. These solutions, while better than replacing the bone, still present limitations.

As it is, while bulk ceramic materials demonstrate a great compressive strength and overall mechanical properties comparable to natural bone, they offer limited surface area for interaction with biological fluids. This limitation can prolong the healing process. Coupled with the increasing demand for patient-specific treatments, this challenge has driven research toward additive manufacturing techniques, enabling the fabrication of custom-designed, alveolar scaffolds tailored to individual anatomical needs.

The standard artificial bioresorbable polymer, poly(lactide) (PLA), is already used in such applications and is already employed in surgical devices such as screws [

9]. To enhance its bioactivity, PLA can be combined with hydroxyapatite (HAp) to better replicate the natural bone environment. In a study by Danoux

et al., this enhancement was shown in the increase in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity by more than 200 % after 14 days of culture between neat PLA and a 50 wt% PLA/HAp composite [

10]. More recently, composites incorporating Barium Titanate (BaTiO3) have been developed to mimic a key physical property of bone, its piezoelectricity. Many studies reviewed by Khare

et al. concluded on a positive effect of electrical stimulation on the speed of bone regeneration [

11]. Rather than relying on external sources of stimulation, multiple research teams turned their eyes towards piezoelectric as a mean to “embed” electrical stimuli in vivo. Yang et al. studied the effect of Barium Titanate and Graphene in the apparent piezoelectric effect of a scaffold [

12]. Their study shows an increase in short-circuit current between PLA and a PLLA/BaTiO3 composite, from nearly 0 to 5.1 nA, further increased to 10 nA with the addition of graphene. This increase in short-circuit current coincides with an increase in ALP activity of 40 % between PLA and their graphene-assisted composite after 7 days. This phenomenon is only visible when the scaffold is mechanically stimulated, therefore benefiting from the piezoelectric effect. It is difficult to pinpoint which specific effect the electrical stimulation has on osteogenesis, as the different studies dealing with this subject tend to use different sources of electrical stimulation; as per the conclusion of a review by Guillot-Ferriols et al. [

13].

Piezoelectric materials are increasingly being explored for a wide range of biomedical applications, including nerve repair, as demonstrated by Orkwis et al. [

14] or cardiac tissue repair, as reported by Gomes et al. [

15]. To leverage multiple beneficial effects, researchers have explored incorporating combinations of ceramics into a single scaffold, such as barium titanate with hydroxyapatite [

16,

17] or calcium silicate [

18]. A comparative study by Huang et al. on hydroxyapatite and β-tri-calcium phosphate leaves the hydroxyapatite first place in biological testing but second place in mechanical testing [

19]. In their conclusion, the authors suggest that an ideal candidate would be a composite reinforced with a mixture of both ceramics.

The effect of architecture on bone formation has been largely discussed. Following these discoveries, multiple teams such as Bittner’s tried to recreate the different bone formations in a single scaffold, by managing multiple porosity rates in a single print [

20]. However, the introduction of porosity, while enhancing biological integration, tends to weaken the mechanical integrity of the scaffold. In the event of a mechanical failure, these structures must still be able to provide sufficient support for the developing neo-tissue and prevent fragmentation into mobile debris, which could compromise healing.

To overcome these limitations, ductile polymers are often blended with PLA to improve toughness and prevent brittle failure. The most commonly studied options are Poly(caprolactone) (PCL) [

21,

22] and Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS) [

23]. PLA/PBS have been extensively investigated to produce tougher materials [

23,

24,

25] promoting ductile failure mode and enhancing the mechanical resilience of these bioresorbable scaffolds. Additionally, a study by Ojansivu et al. (2020) has shown that neat PLA knitted scaffolds pale in front of blended PLA with PBS or PCL, in terms of osteogenesis. These PLA/PBS and PLA/PCL at 95/5 wt% demonstrate an increase of 220 % in cell proliferation after 14 days of culture [

1].

In this study, the authors investigate the influence of PBS on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed PLA-based composite specimens. The analysis focuses on compression and 3-point bending tests, as these loading modes closely replicate physiological strain conditions. Mechanical analysis was carried out beyond the elastic limit to characterize the behavior of the materials even under failure, highlighting their potential to support tissue regeneration post-yield. Additionally, the effect of Barium titanate content was investigated to identify a balance between ceramic’s osteogenic benefits and its impact on ductile-to-brittle transition.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

In this study, Poly(lactide) (PLA) was supplied by NatureWorks (USA) under the reference IngeoTM Biopolymer 2003D. Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) was obtained from NaturePlast (France) under the reference PBI 003. Barium titanate (mBT) was purchased from ThermoScientific (USA) as Barium Titanium Oxide, with a purity of 99 %, and with 99.9 % of the particles finer than 325-mesh.

Methods

Processing: Fabrication of Compounds, Filaments and Samples

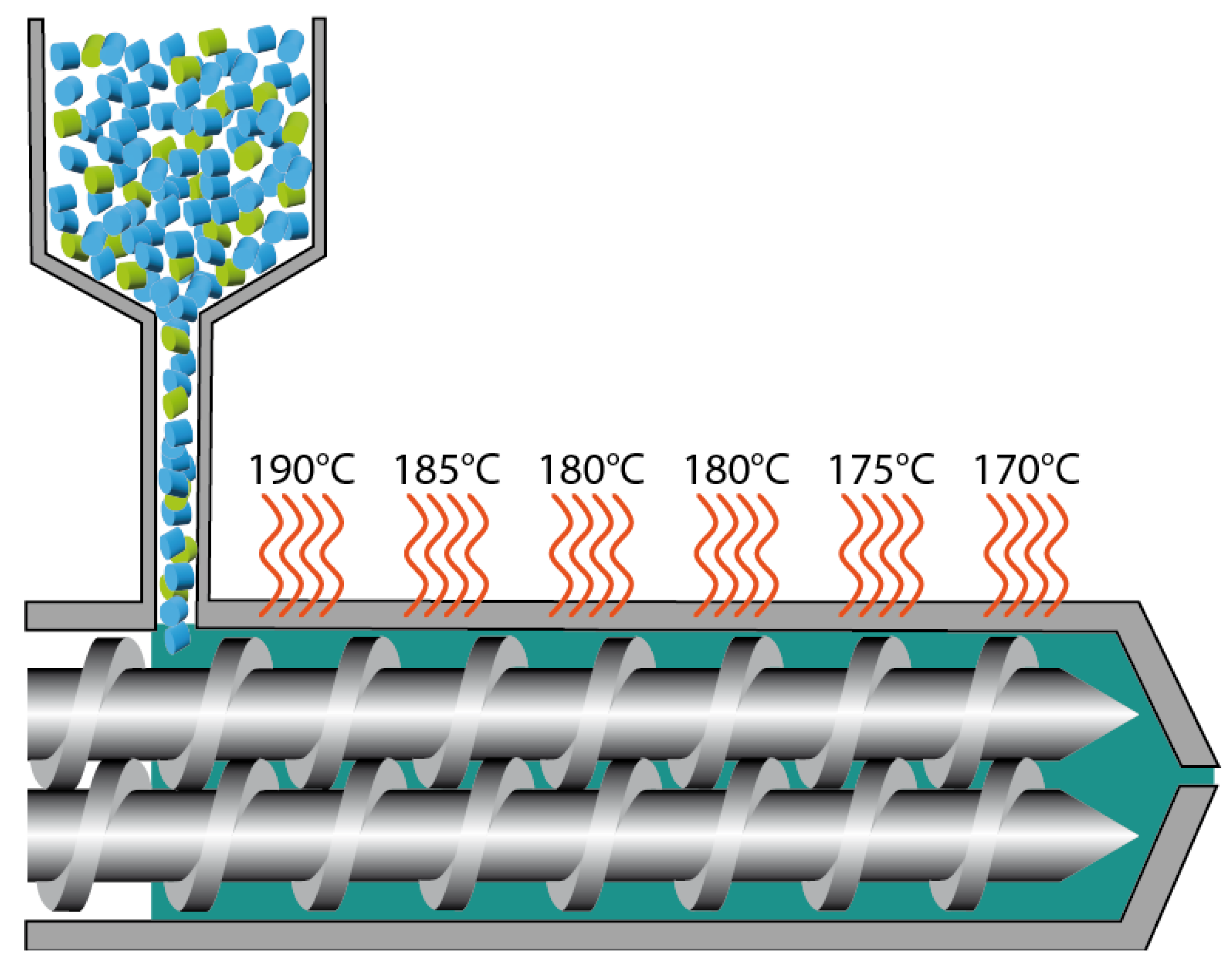

PLA and PBS were blended at 80/20 wt% ratio using a co-rotating twin-screw extruder to obtain a homogeneous PLA/PBS blend, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Neat PLA and PLA/PBS blend were then compounded with BaTiO3 at concentrations of 5, 10 and 20 wt% using the same extrusion process. All formulations were processed through a 3Devo Filament Maker to produce filaments with a controlled diameter of 1.70 ± 0.1 mm.

These filaments were then used for 3D printing with a Creality CR10-V3 FFF 3D printer. 3D models were created using 3D Builder software and sliced using Creality Slicer 4.8.2. Compression specimens were sized as 1 cm3 cubes in accordance with ISO 604. Rectangular rods measuring 80×10×4 mm3 (following ISO 178 standards) were printed for flexion testing and impact fracture testing. All mechanical test specimens were printed with 100 % filling in alternating 45° and -45° directions, to prevent void-filling by the strings slipping and overall flattening of the specimens during the test. Prior to testing, all specimens were dried at 50 °C for three days to remove residual moisture.

Characterization Methods

To characterize the raw materials and produced products, various characterization techniques were used to determine thermal properties, mechanical properties, microstructure, and morphology.

Mechanical Analysis

The final application of the material studied is the manufacture of implants for bone tissue engineering, so the characterization of mechanical properties was oriented towards compression and bending tests. Compression tests were carried out using an Instron 3366 universal testing machine, with a constant speed of 5 mm/min. Flexural tests were conducted on the same system, with a constant speed of 2 mm/min, until 30 mm vertical deflection.

Thermal and Microstructural Analysis

The microstructures of the 3D printed blends and composites specimens were analyzed via differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using TA Q20 DSC analyzer, with a heating rate of 2 K·min−1 under nitrogen atmosphere. The analyses were conducted on the first heating cycle, as process-induced thermal effect can’t be excluded for 3D-printed scaffolds.

Post-processing treatment such as annealing were avoided as uncontrolled shrinking would alter the scaffold architecture. The polymer and ceramic contents in the various formulations were evaluated throughout the process using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). These measurements were performed with a Netzsch TG 209 F3 Tarsus, with a heating rate of 3 K·min−1 under nitrogen atmosphere.

Morphological Analysis

Filaments’ diameters were continually monitored using the integrated optic sensor and the data were recorded with 3Devovision software. Partial or complete fractures resulting from flexural testing were analyzed using X-Ray microtomography performed with a High-Resolution 3D Micro Computed Tomography & Digital Radioscopy Compact System by DeskTom. Scanning parameters include a tube voltage of 100 kV, a current of 100 μA, a voxel size of 10 μm and an acquisition rate of 3 frames per second. The 3D reconstruction of the samples was carried out using X-ACT64 and visualization was performed using VGStudio version 3.1.2.

3. Results and Discussion

Following the compounding of the different materials, the samples were successfully fabricated and analyzed, both thermically and mechanically, completed with X-ray aided micro-observations. Those analyses allowed the control of our process and its influence on the properties of the printed parts.

Thermal Analysis

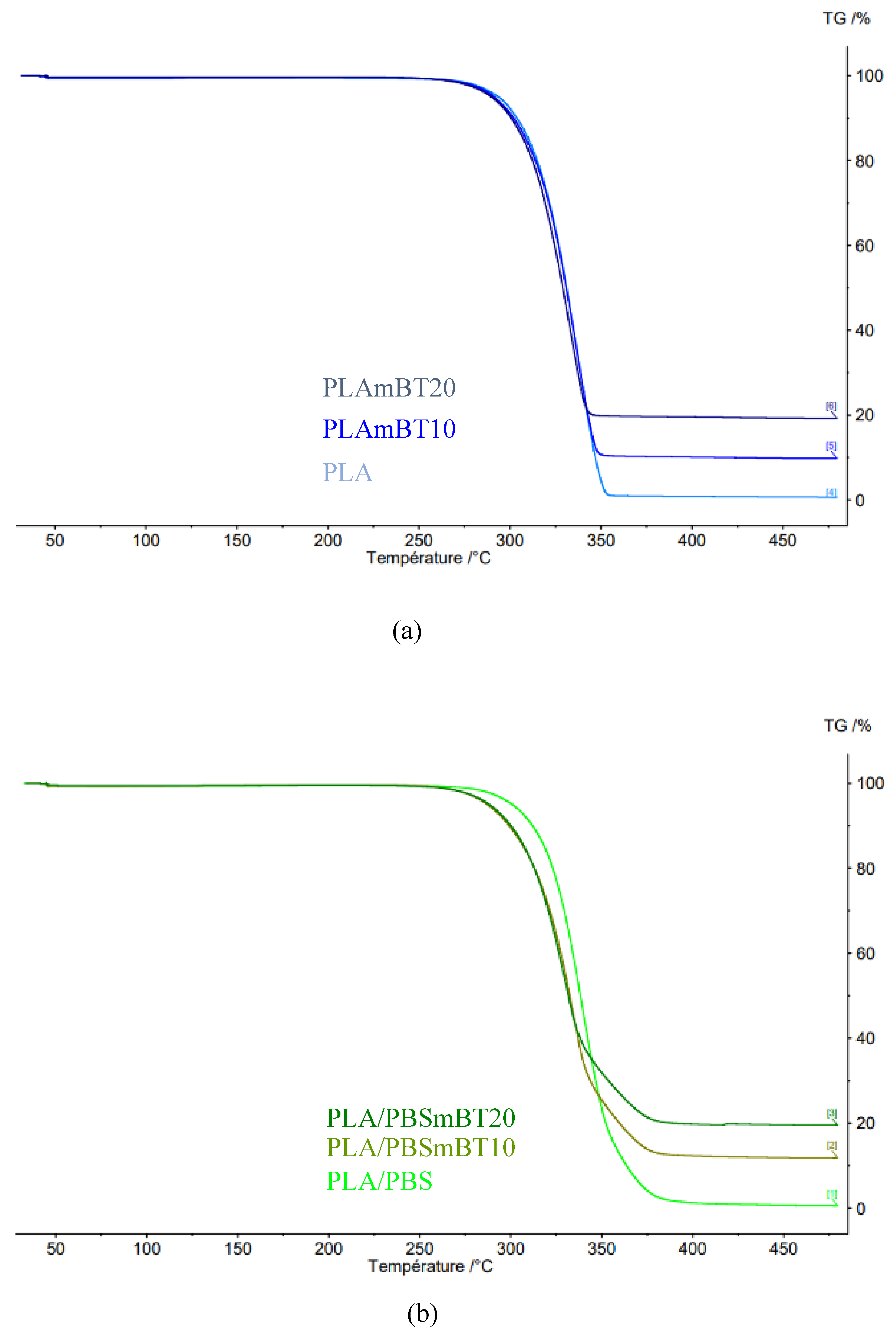

The proportions of the composites’ different components were achieved, with a slight inconvenience due to the proximity between PLA degradation and PBS degradation (

Figure 2). PLA-based composites curves exhibited a single degradation phase, with a degradation temperature around 310 °C. In contrast, Blend-based composites displayed two distinct degradation phases, reflecting the higher thermal stability of PBS, degrading around 340 °C.

Barium titanate remained stable within the fixed temperatures, and its residual mass after the degradation corresponded well with the matrix degradation profiles (

Table 1). The different formulations include the expected amounts of barium titanate, meaning 0 %, 10 ± 0.3 % and 20 ± 0.4 % with a slight deviation to 12 ± 0.3 % for the blend-based PLA/PBSmBT10. The blend was more thermally stable than all other formulations, with a slight delay in the degradation of the PLA and the overall shift in temperatures.

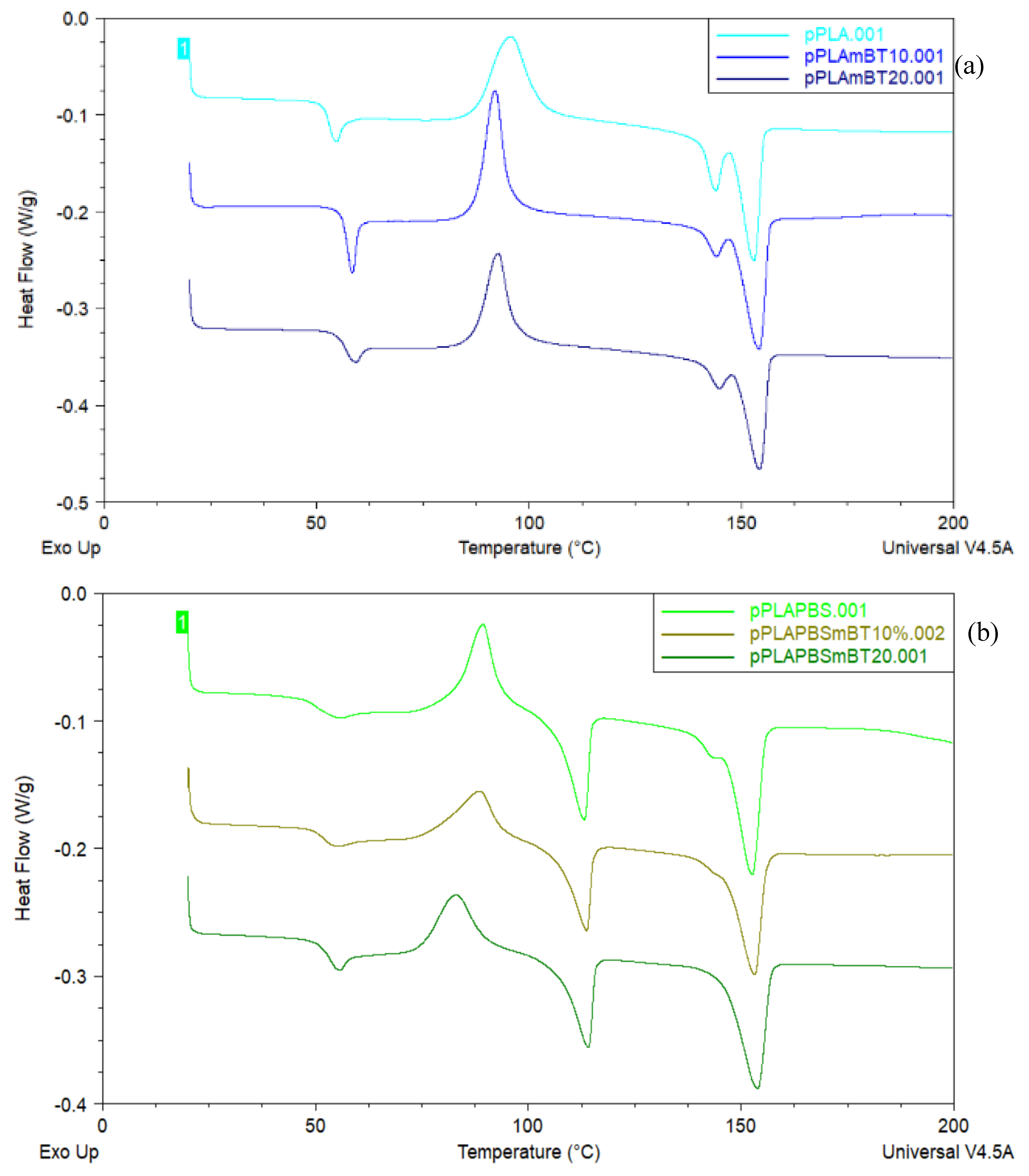

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curves revealed different transition temperatures and the degree of crystallinity of both PLA and PBS were calculated for the PLA and PLA/PBS composites (

Table 2). PLA crystallinity, for example, was calculated by subtraction of the cold crystallization enthalpy from the melting enthalpy. With this method, an increase in PLA’s crystallinity of more than 220 % is observed between the PLA-based materials and the PLA/PBS-based materials. However, the cold crystallization of PLA and the melting of PBS occur at relatively close temperatures, resulting in overlapping signals. This overlap has been observed by Lin

et al. [

26] who attributed the shift in PLA’s cold crystallization temperature to the nucleating effect of PBS.

While this explanation is possible, it is also possible that the proximity of these two thermal events interferes with the resolution of the analysis, without necessarily indicating interaction between the phenomena themselves. The signal merging could artificially increase the measured crystallinity of PLA while simultaneously reducing the apparent crystallinity of PBS (

Figure 3). The same authors noticed a slight decrease in glass transition temperature between PLA and the PLA/PBS blend, which they interpreted as a mild plasticizing effect [

26].

Additionally, ceramics such as barium titanate may act as nucleating agent, as evidenced by the reduced cold crystallization temperature of PLA in ceramic-filled composites. This effect is consistent with findings from Mystiridou et al. [

27]. However, despite the nucleation effect, no significant increase in PLA crystallinity was observed. Moreover, the observed rise in glass transition temperature in presence of the barium titanate may suggest a restriction in the mobility of PLA macromolecular chains, indicating interaction at the molecular level that may influence processing and performance.

However, this nucleating effect does not increase the crystallinity of PLA. Furthermore, the higher glass transition temperature in presence of the barium titanate, from 52.5 to 56.8 °C, could indicate the latter would hinder the mobility of macromolecular chains.

Compression Tests

All specimens were subjected to uniaxial compression testing to determine their Young Modulus. The samples were printed at 100 % filling to get what would be the closest to the materials’ properties, minimizing the influence of structural design and porosity.

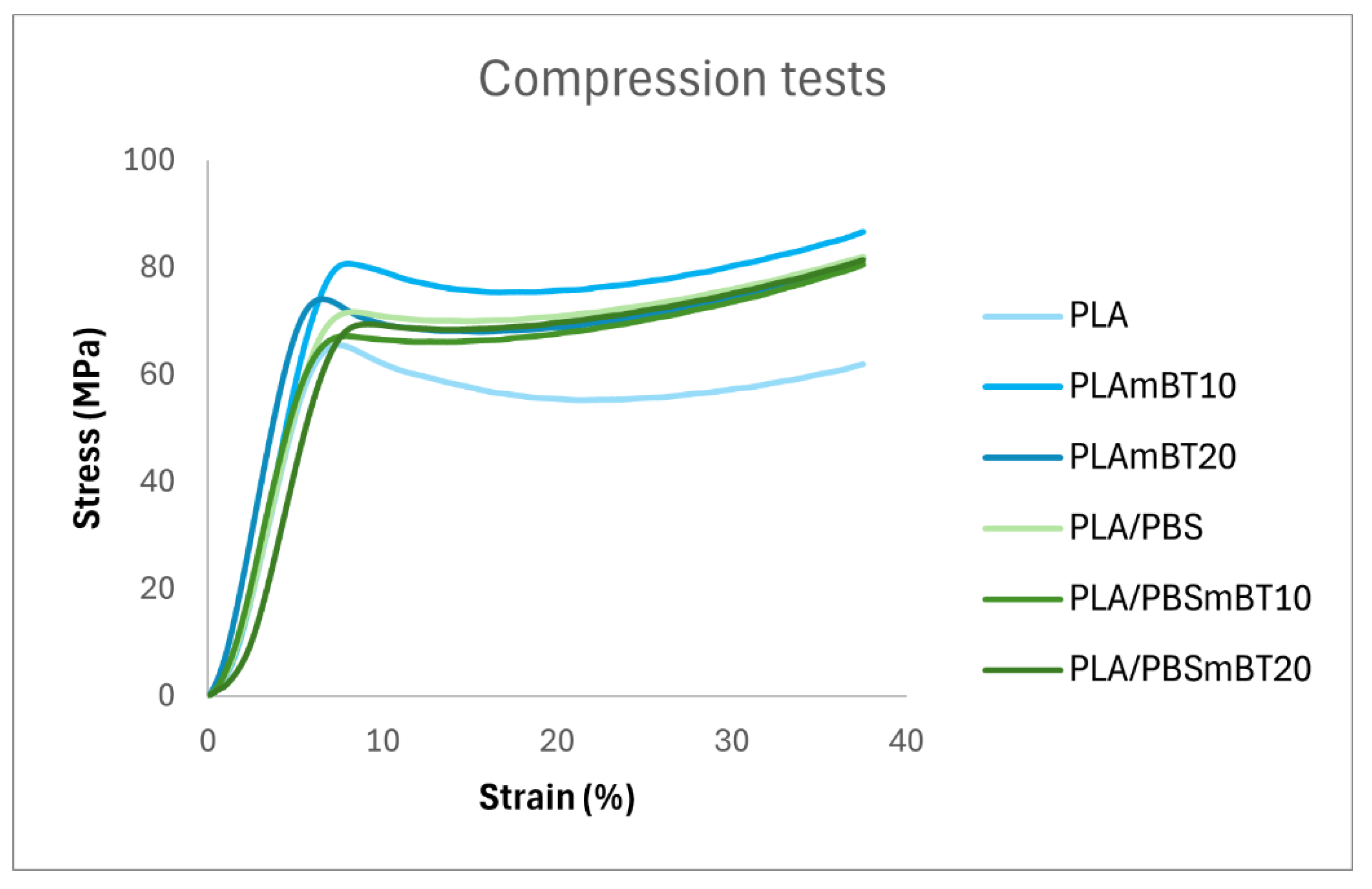

The resulting stress–strain curves are reproduced in

Figure 4. It is important to note that the curves do not represent material failure, as they were truncated just before reaching the load cell’s capacity limit. The curves profiles are consistent with those typically observed for standard injection-molded polymers [

28].

From these curves, key elastic properties were extracted, including Young’s modulus, maximum elastic strain and elastic limit. However, plastic properties could not be determined as none of the specimens underwent failure under the testing conditions. This shows that the different formulations are resistant to compression.

The elastic properties of the tested materials are summarized in

Table 3. As expected, PLA-based composites exhibit greater stiffness than PLA/PBS blend-based composites, reflecting the inherent lower Young’s modulus of PBS compared to PLA. For all formulations, an increase in BaTiO3 content resulted in a corresponding rise in Young’s modulus. The observed reduction in stiffness due to PBS incorporation aligns with findings from Zhang et al. [

29] who reported a 16 % decrease in Young’s modulus in tensile tests with the addition of 20 wt% PBS.

In contrast, the reduction observed in our compression tests was less pronounced, amounting to less than 5 %. However, unlike in neat PLA, the addition of BaTiO3 to the PLA/PBS blend did not produce a significant increase in stiffness. This discrepancy may be attributed to the dispersion of ceramic particles within the interphase between PLA and PBS, potentially altering the stress transfer mechanisms within the composite. Despite these variations, all formulations reexhibit relatively similar elastic properties, remaining within a close range of stiffness.

Three-Point Bending Tests

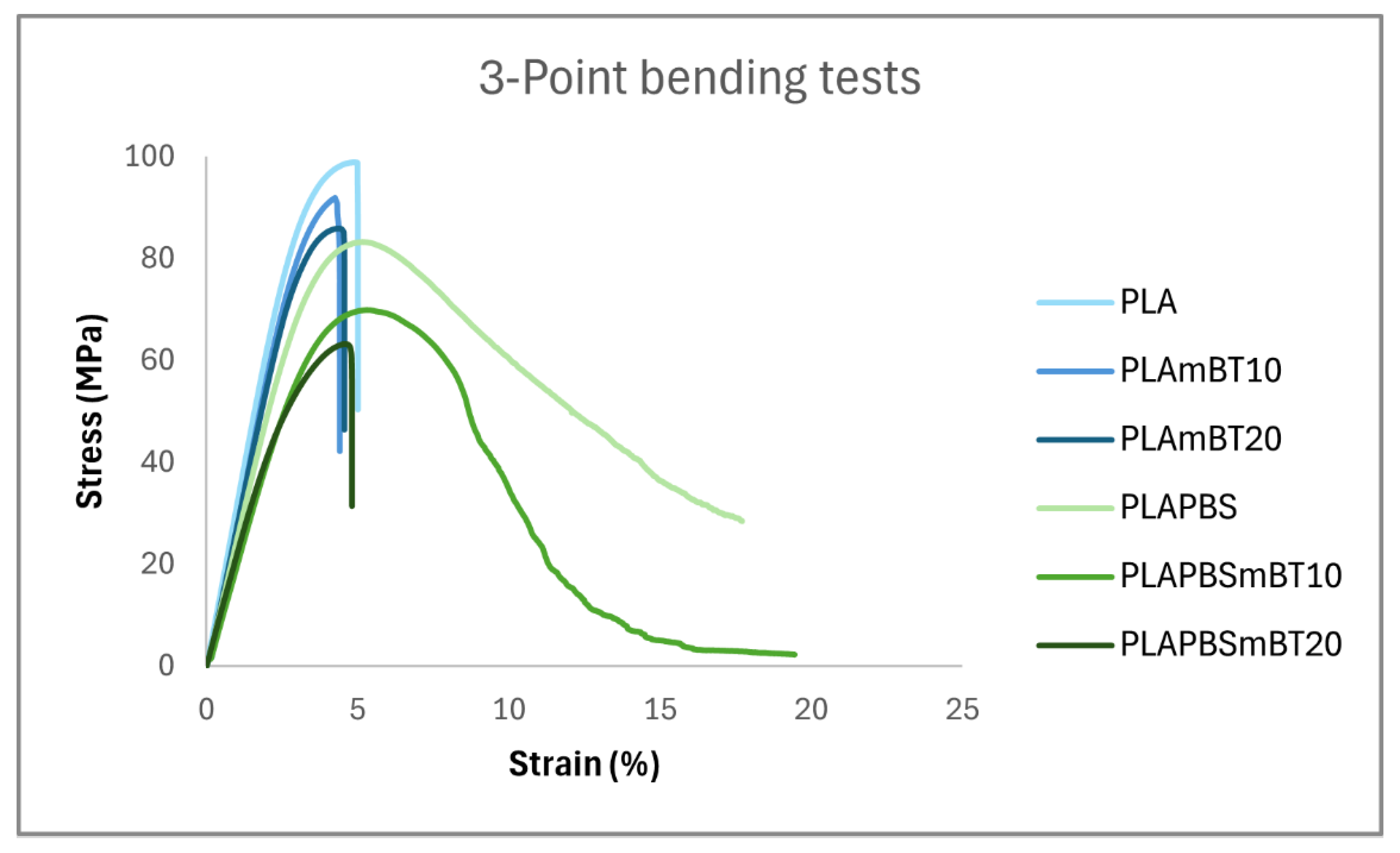

The 3-point bending test combines both compressive and tensile stresses, and as expected, the trends observed in compression tests were similarly reflected in bending behavior. PLA and its composites exhibited higher stiffness compared to their PLA/PBS blend counterparts as shown in

Table 4.

However, unlike in compression testing, the bending tests revealed distinct differences in plastic behavior. All PLA-based specimens failed in a brittle manner, fracturing shortly after exceeding the elastic limit. In contrast, the PLA/PBS blend and its composite containing 10 wt% BaTiO

3, exhibited ductile behavior, progressing beyond the elastic regime with a significant drop in stress, while still maintaining relative integrity (

Figure 5). This ductility effect, however, was no longer observed in the composite containing 20 wt% BaTiO

3. The addition of PBS decreases the overall mechanical support, with a global loss in stiffness, -23 %, -23 % and -31 % for ceramic loads of 0 %, 10 % and 20 % respectively, as well as a loss in the elastic limit, -17 %, -19 % and -30 %. The blend can however be strained further than the PLA and the PLA-based composites, with an elastic deformation increased by 7 % and 17 % for ceramic loads of 0 and 10 wt% respectively. This increase could be the result of the alleged plasticizing effect of the PBS seen in DSC analyses and in the study by Lin et al. [

26].

These findings are consistent with previous reports on the role of PBS in enhancing the ductility of PLA, as summarized in the review by Su et al. [

23], which highlighted increased elongation at break in PLA/PBS systems. Our results confirm that this ductility enhancing effect of PBS is preserved at moderate ceramic loading, despite ceramics typically being associated with increased brittleness.

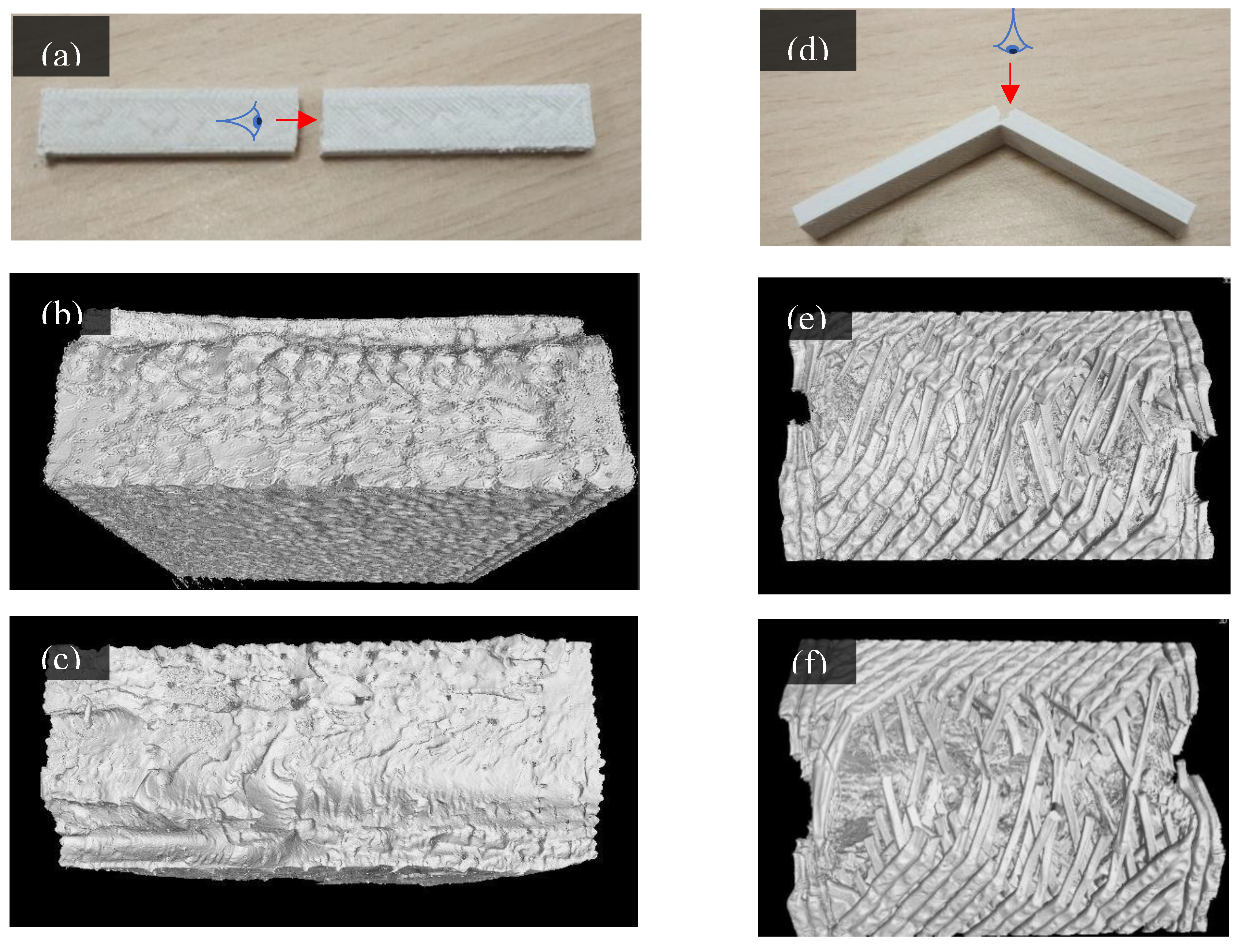

Nevertheless, even though the PLA/PBSmBT10 composite demonstrated ductile fracture behavior, it remained more brittle than the pure blend. This is supported by tomography observations, where the most strained regions of the composite specimens revealed a higher occurrence of torn filament structures compared to the blend alone (

Figure 6).

Fracture Morphology After Bending Tests

Figure 6a,d illustrate representative specimens following the three-point bending test. PLA-based composites exhibited a clean, brittle fracture (

Figure 6a), whereas the PLA/PBS blend-based composites showed incomplete fractures, indicating ductile failure behavior (

Figure 6d). These were further analyzed using X-ray microtomographic reconstruction from the viewing angles indicated in

Figure 6a,d. Consistent with macroscopic observations, PLA-based composites displayed a smooth fracture (

Figure 6b,c) with minimal distinction between individual printed strings. In contrast, PLA/PBS blend-based composites exhibited plastic elongated individual strings (

Figure 6e,f), with the blend keeping the most unbroken strings.

While most composites demonstrate the same smooth fracture as the PLA samples, the PLA/PBSmBT10 demonstrates a spiked fracture with irreversibly deformed strings. After the test, the specimens were released from the applied force, even allowing for an elastic return in the PLA/PBS and PLA/PBSmBT10 samples. The observations of a spiked fracture in PLA/PBS blends compared to the smooth fractures of PLA concur with the work of Lin et al. [

26] and the SEM observations of 3-Point bending post-test specimens.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the successful fabrication of novel composites using Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) additive manufacturing aimed at reducing the risk of brittle failure in bone scaffolds. The PLA/PBS blend matrix and its composites exhibited ductile failure behavior whereas other materials demonstrated fragile failures, thereby preserving their structural role as scaffolds even under mechanical stress.

Although the incorporation of PBS led to a reduction in stiffness compared to pure PLA composites, this decrease in Young’s modulus was modest, less than 8 % under compression. This reduction remains negligible when compared to the significant stiffness gap between these polymer-based composites and natural bone tissue, which can reach up to 200 GPa [

9].

Given that these materials are designed to be bioresorbable and are not intended to remain permanently in vivo, replicating the exact mechanical properties of bone is not necessary. Instead, their mechanical resilience and ductility make them promising candidates for safe, temporary support during bone regeneration. Other candidates for bone-surgery bioresorbable tools, such as PLA/PCL blends and their composites reinforced with HAp [

21] remain in the same range of stress and stiffness as the composites shown in this study, validating their viability as temporary mechanical support as well as regeneration support.

Following this study, the piezoelectric effect of our composites remains to be measured to qualify the potential effect on osteogenesis and the effect of PBS and the loss of stiffness on 3D-printed parts’ deformation and therefore on generated electrical charges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A. and M.R.; formal analysis, P.B.; investigation, P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., M.R., P.M., S.A. and R.G.; writing—review and editing, P.B., M.R., P.M., S.A. and R.G.; visualization, P.M.; supervision, R.G. and P.M.; funding acquisition, S.A. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded through BAPPAS project by Grand Est and Normandy regions in France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

| DSC |

Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| FFF |

Fused Filament Fabrication |

| HAp |

Hydroxyapatite |

| mBT |

Micro Barium Titanate |

| PBS |

Poly(butylene succinate) |

| PCL |

Polycaprolactone |

| PLA |

Poly(lactide) |

| TGA |

Thermal Gravimetric Analysis |

References

- Ojansivu, M.; Johansson, L.; Vanhatupa, S.; Tamminen, I.; Hannula, M.; Hyttinen, J.; Kellomäki, M.; Miettinen, S. Knitted 3D Scaffolds of Polybutylene Succinate Support Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Growth and Osteogenesis. Stem Cells International 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.R.; Aujla, R.; Biswas, S.P. Total Hip Arthroplasty—over 100 Years of Operative History. Orthopedic Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.H.; Cai, Z.B.; Li, W.; Yu, H.Y.; Zhou, Z.R. Fretting in Prosthetic Devices Related to Human Body. Tribology International 2009, 42, 1360–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Wu, D.; Luo, M.; Ma, H. Stress Shielding Effects of Two Prosthetic Groups after Total Hip Joint Simulation Replacement. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2014, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Guo, X.; Cai, N.; Dong, Y. Novel Fabrication Method of Porous Poly(Lactic Acid) Scaffold with Hydroxyapatite Coating. Materials Letters 2012, 74, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsell, R.; Einhorn, T.A. The Biology of Fracture Healing. Injury 2011, 42, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MBCP®|Substitut Osseux Synthétique de Phosphate de Calcium. Available online: https://biomatlante.com/fr/produits/mbcp-substitut-osseux-synthetique (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- MBCP® Putty—In’ossTM|Substitut Osseux Synthétique Biphasé Malléable. Available online: https://biomatlante.com/fr/produits/mbcp-putty-in-oss (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Weisman, J.; Ballard, D.; Wolford, D.; Pascual-Garrido, C.; Wolford, L.; Woodard, P.; Mills, D. 3D Printing Custom Bioactive and Absorbable Surgical Screws, Pins, and Bone Plates for Localized Drug Delivery. JFB 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoux, C.B.; Barbieri, D.; Yuan, H.; de Bruijn, J.D.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Habibovic, P. In Vitro and in Vivo Bioactivity Assessment of a Polylactic Acid/Hydroxyapatite Composite for Bone Regeneration. Biomatter 2014, 4, e27664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, D. Electrical Stimulation and Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, S.; Qi, F.; Zan, J.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Shuai, C. Graphene-Assisted Barium Titanate Improves Piezoelectric Performance of Biopolymer Scaffold. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 116, 111195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Ferriols, M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Gómez Ribelles, J.L.; Gallego Ferrer, G. Electrical Stimulation: Effective Cue to Direct Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells? Biomaterials Advances 2022, 138, 212918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkwis, J.A.; Wolf, A.K.; Mularczyk, Z.J.; Bryan, A.E.; Smith, C.S.; Brown, R.; Krutko, M.; McCann, A.; Collar, R.M.; Esfandiari, L.; et al. Mechanical Stimulation of a Bioactive, Functionalized PVDF-TrFE Scaffold Provides Electrical Signaling for Nerve Repair Applications. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 140, 213081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.R.; Castelo Ferreira, F.; Sanjuan-Alberte, P. Electrospun Piezoelectric Scaffolds for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 137, 212808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavangar, M.; Heidari, F.; Hayati, R.; Tabatabaei, F.; Vashaee, D.; Tayebi, L. Manufacturing and Characterization of Mechanical, Biological and Dielectric Properties of Hydroxyapatite-Barium Titanate Nanocomposite Scaffolds. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 9086–9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Zhao, K.; Bian, T.; Tang, Y. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Properties Characterization of Barium Titanate/Hydroxyapatite Spherical Nanocomposite Materials. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2017, 715, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jiao, C.; Yu, H.; Naqvi, S.M.R.; Ge, M.; Cai, K.; Liang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Tian, Z.; et al. 3D Printed Barium Titanate/Calcium Silicate Composite Biological Scaffold Combined with Structural and Material Properties. Biomaterials Advances 2024, 158, 213783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Caetano, G.; Vyas, C.; Blaker, J.; Diver, C.; Bártolo, P. Polymer-Ceramic Composite Scaffolds: The Effect of Hydroxyapatite and β-Tri-Calcium Phosphate. Materials 2018, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, S.M.; Smith, B.T.; Diaz-Gomez, L.; Hudgins, C.D.; Melchiorri, A.J.; Scott, D.W.; Fisher, J.P.; Mikos, A.G. Fabrication and Mechanical Characterization of 3D Printed Vertical Uniform and Gradient Scaffolds for Bone and Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Acta Biomaterialia 2019, 90, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitjamit, S.; Thunsiri, K.; Nakkiew, W.; Wongwichai, T.; Pothacharoen, P.; Wattanutchariya, W. The Possibility of Interlocking Nail Fabrication from FFF 3D Printing PLA/PCL/HA Composites Coated by Local Silk Fibroin for Canine Bone Fracture Treatment. Materials 2020, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanajili, S.; Karami-Pour, A.; Oryan, A.; Talaei-Khozani, T. Preparation and Characterization of PLA/PCL/HA Composite Scaffolds Using Indirect 3D Printing for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 104, 109960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Kopitzky, R.; Tolga, S.; Kabasci, S. Polylactide (PLA) and Its Blends with Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS): A Brief Review. Polymers 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamarche, E.; Mattlet, A.; Livi, S.; Gérard, J.-F.; Bayard, R.; Massardier, V. Tailoring Biodegradability of Poly(Butylene Succinate)/Poly(Lactic Acid) Blends With a Deep Eutectic Solvent. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Ohya, T.; Iida, K.; Hayashi, H.; Hirano, K.; Fukuda, H. Increased Impact Strength of Biodegradable Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Butylene Succinate) Blend Composites by Using Isocyanate as a Reactive Processing Agent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. 4D Printing of Shape Memory Polybutylene Succinate/Polylactic Acid (PBS/PLA) and Its Potential Applications. Composite Structures 2022, 279, 114729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystiridou, E.; Patsidis, A.C.; Bouropoulos, N. Development and Characterization of 3D Printed Multifunctional Bioscaffolds Based on PLA/PCL/HAp/BaTiO3 Composites. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Nguyen, T.P.; Pham, V.H.; Hoang, G.; Manivasagan, P.; Kim, M.H.; Nam, S.Y.; Oh, J. Hydroxyapatite Nano Bioceramics Optimized 3D Printed Poly Lactic Acid Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Application. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 3443–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Shi, J.; Ye, H.; Zhou, Q. Distinctive Tensile Properties of the Blends of Poly(l-Lactic Acid) (PLLA) and Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS). J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).