2.1. Characterization of the Catalysts

Mono- and bimetallic Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec/ZnO, and PdCu-Pec/ZnO catalysts were prepared via an adsorption method. The amounts of the polymer and metal ions adsorbed on ZnO were assessed by determining their concentrations in the mother liquor after the sorption process. The pectin concentration was determined by measuring the viscosity of the mother liquor and referencing a previously established calibration curve, while the concentration of metal ions was determined using a photoelectric colorimetric (PEC) method.

Table 1 summarizes the results of pectin adsorption onto ZnO for the

Pec/ZnO and

Pd-Pec/ZnO composites. The data reveal distinct differences in the adsorption behavior between the two systems. In the Pec/ZnO system, the degree of pectin adsorption decreases from 100% to 59% as the amount of pectin introduced into the system increases from 18.5 to 92.5 mg. This trend indicates a saturation of available adsorption sites on the ZnO surface, leading to a plateau in the pectin content within the final composite, which reaches a maximum of approximately 5.0 wt%. In contrast, the

Pd-Pec/ZnO system exhibited an adsorption degree of 96-100%. This enhanced adsorption performance is likely related to the formation of polymer–metal complexes between pectin molecules and Pd²⁺ ions. The interaction between palladium and functional groups of pectin (such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups) may promote partial crosslinking of the polymer chains, increasing their affinity for the ZnO surface. Depending on the amount of pectin introduced, the calculated pectin content was found to be 1.8 wt%, 3.4 wt%, and 5.0 wt% for the

Pec/ZnO composites, and 1.8 wt%, 3.5 wt%, and 8.1 wt% for the

Pd-Pec/ZnO composites. For simplicity, the obtained Pec/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO composites were designated as Pec1.8/ZnO, Pec3.4/ZnO, Pec5.0/ZnO,

Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO,

Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO, and

Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO, where the number indicates the pectin content (in wt%) in the composite.

Table 1.

The results of the assessment of pectin content in Pec/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO composites.

Table 1.

The results of the assessment of pectin content in Pec/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO composites.

m(Pec) in the

Initial Solution, mg

|

m(Pec) in Solution after Sorption, mg |

m(Pec) Adsorbed, mg |

Adsorption Degree, % |

Pec Content, % |

| Pec/ZnO |

| 18.5 |

0.0 |

18.5 |

100 |

1.8 |

| 37.0 |

2.2 |

34.8 |

94 |

3.4 |

| 92.5 |

37.8 |

54.7 |

59 |

5.0 |

| Pd-Pec/ZnO |

| 18.5 |

0.0 |

18.5 |

100 |

1.8 |

| 37.0 |

0.0 |

37.0 |

100 |

3.5 |

| 92.5 |

3.4 |

89.1 |

96 |

8.1 |

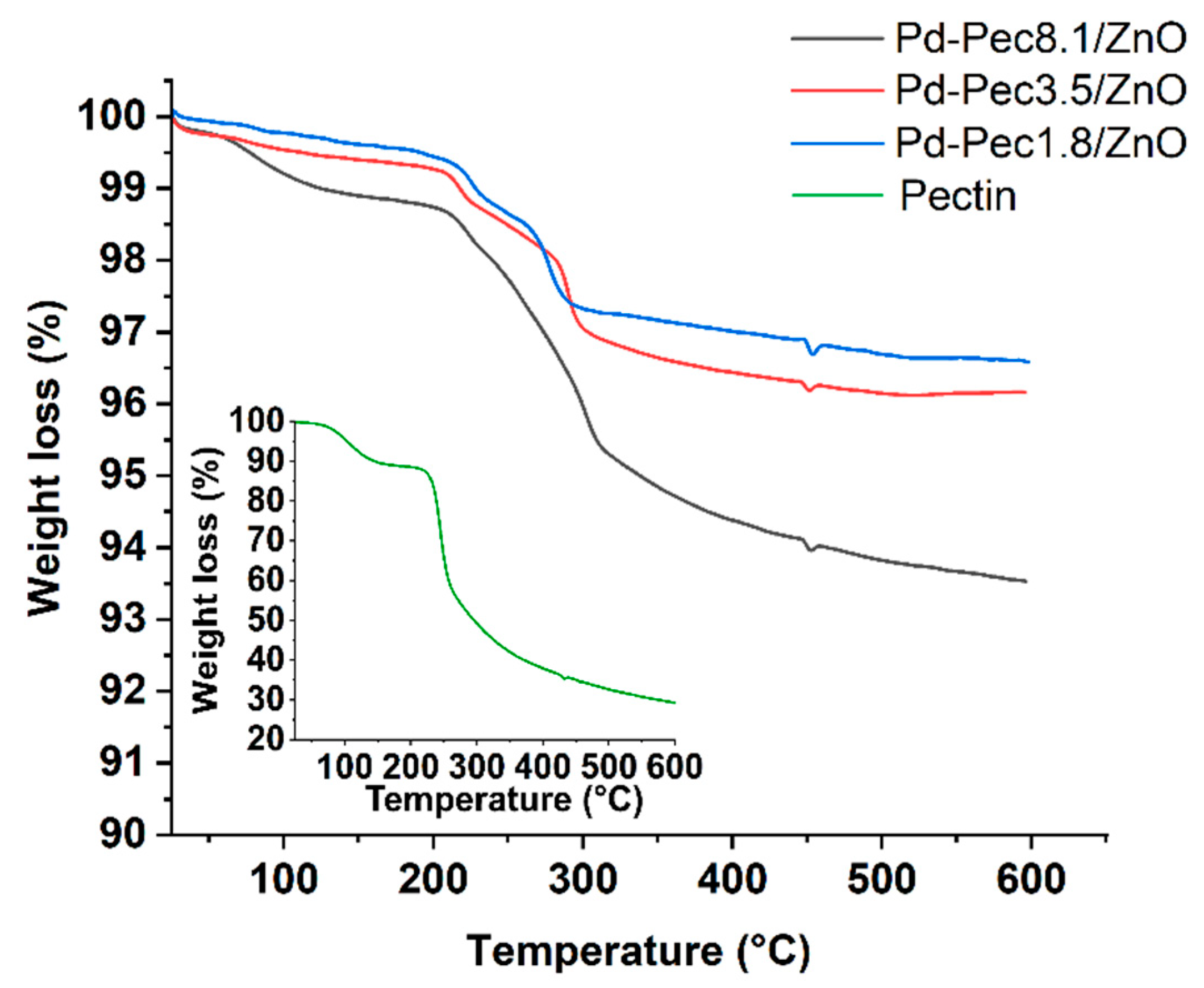

The presence and varying content of pectin in the composites was confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and infrared spectroscopy (IR). According to TGA data (

Figure 1) the thermal degradation of

Pd-Pec/ZnO composites occurred in two stages. Below 200 °C, there is an initial weight loss of 0.4-1.3%, which corresponds with the evaporation of physically adsorbed water. The main weight loss occurred in the range from 200 to 400 °C, corresponding to the decomposition of the polymer [

20]. In the case of Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO, the weight loss in the 200–400 °C temperature range was higher (~4%) compared to Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO (~2%) and Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO (~3%), confirming the differing polymer content in the composites. Given that pure pectin loses approximately 50% of its mass in the 200–400 °C temperature range (

Figure 1, inset), the calculated pectin content in

Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO was estimated to be around

8%. This estimate is consistent with the viscosimetry data presented in

Table 1, thereby confirming the quantitative deposition of pectin on the ZnO surface.

Figure 1.

TGA of Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO, Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO and pectin (inset).

Figure 1.

TGA of Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO, Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO and pectin (inset).

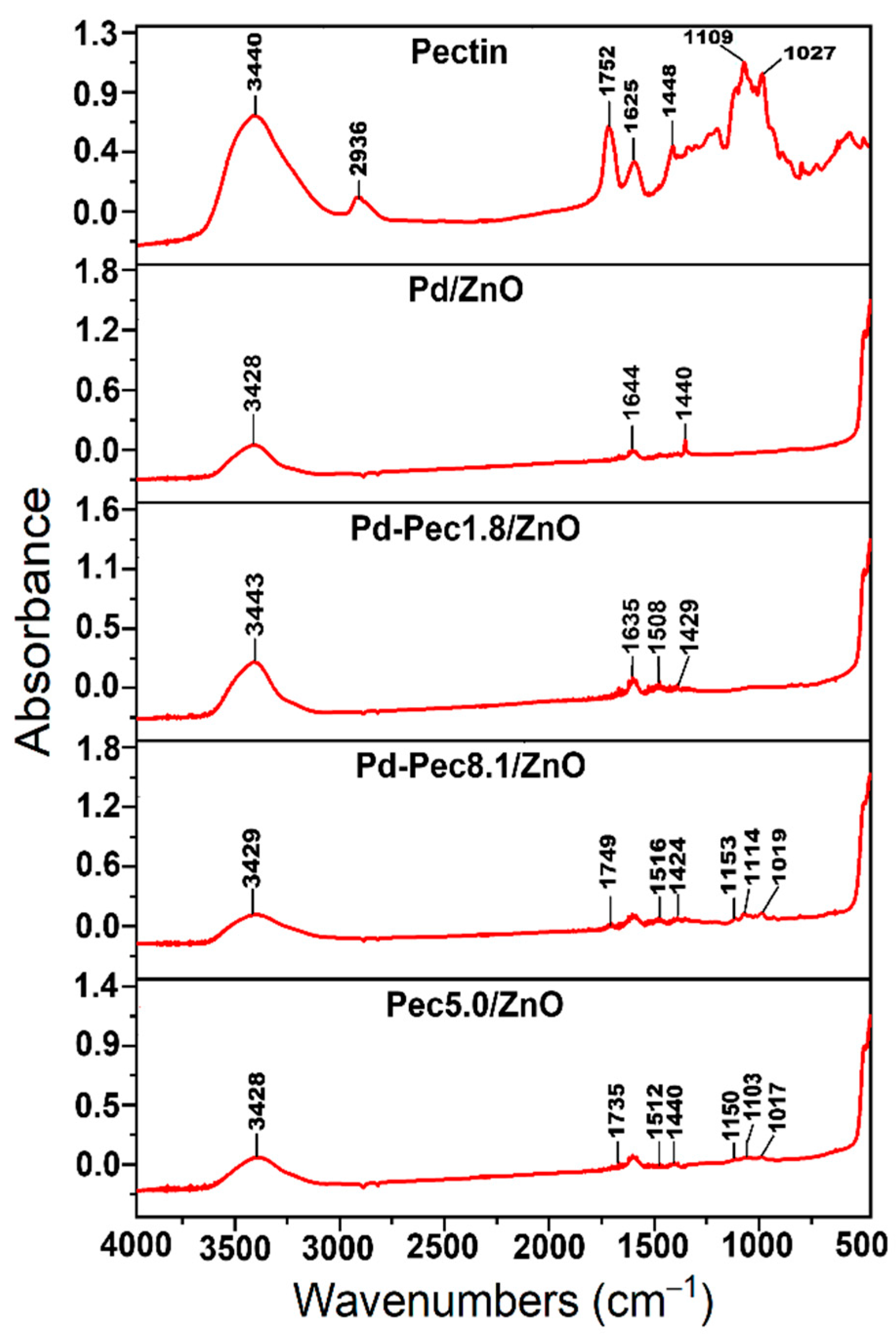

Figure 2 shows IR spectra of pectin, Pd/ZnO,

Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO and Pec5.0/ZnO. The IR spectrum of pectin (Figure 2a) displays characteristic absorption bands corresponding to various functional groups of the polymer. Specifically, the bands at

3440 cm⁻¹,

1752 cm⁻¹, and

1625 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the stretching vibrations of

–OH, C=O of ester, and

C=O of carboxylic acid groups, respectively [

21]

. Notably, t

he absorbance is higher at 1752 cm−1 than at 1625 cm−1, confirming a high degree of esterification of the pectin (more than 50%). In addition, the region between 1200–1500 cm⁻¹ contains absorption bands associated with the stretching and bending vibrations of –C–OH, –C–H, and –O–H functional groups [

22]. The broad absorption band in the range of 950–1200 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the “fingerprint” region of carbohydrates, which is crucial for identifying key structural units such as C–O, C–O–C, and C–C bonds in polysaccharides [

23]. The

IR spectrum of Pd/ZnO exhibits characteristic bands at

400–500 cm⁻¹, 1635 cm⁻¹, and

3443 cm⁻¹. The intensive band in the range of

400–500 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the

Zn–O stretching vibrations, which are typical for ZnO-based materials [

24]. The band at

1635 cm⁻¹ is assigned to the

bending vibrations of adsorbed water molecules (H–O–H), while the broad absorption band at

3443 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the

O–H stretching vibrations of surface hydroxyl groups or physically adsorbed water [

25]. The IR spectra of

Pec5.0/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO composites (

Figure 2c–f) display absorption bands characteristic of both

pectin and

Pd/ZnO, confirming the successful incorporation of the polymer into the composite structure. Notably, the intensity of pectin-related bands (especially evident in the fingerprint region around 950–1200 cm⁻¹) increases in the following order:

Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO < Pec5.0/ZnO < Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO, reflecting the increasing pectin content in the composites. This trend is

consistent with the results obtained from viscosimetry (Table 1) and TGA (Figure 1), further confirming the varying amounts of polymer deposited on the ZnO surface.

Moreover, a comparison of IR spectra of pectin (Figure 2a), Pec5.0/ZnO (Figure 2f) and Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO (

Figure 2d) composites indicated interaction of pectin with both ZnO and Pd ions. This is evidenced by the shift of the ester carbonyl (COOR) band from 1752 cm⁻¹ in pure pectin to 1735 cm⁻¹ in Pec5.0/ZnO and 1749 cm⁻¹ in Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO. Furthermore, new bands appearing at

1512 (Pec5.0/ZnO) and 1516 cm⁻¹ (Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO) in the composite samples can be attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate anions (COO⁻) [

26], indicating coordination between deprotonated carboxyl groups and Zn²⁺ or Pd²⁺ ions. Minor shifts in the fingerprint region (950–1200 cm⁻¹) further support the structural modification of pectin upon interaction with the inorganic components.

Figure 2.

IR spectra of pectin, Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO and Pec5.0/ZnO.

Figure 2.

IR spectra of pectin, Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO and Pec5.0/ZnO.

According to photoelectric colorimetric (PEC) analysis data, palladium ions were quantitatively adsorbed (~100%) on ZnO, which can be explained by the hydrolysis of Pd ions in the presence of ZnO. Pec/ZnO composites with a low pectin content (up to ~3.5 wt.%) also demonstrated high sorption capacity (96-99%) toward Pd²⁺ ions. In these cases, palladium ions likely interact with both ZnO and the pectin adsorbed on its surface. However, when the pectin content in the Pec/ZnO composite was increased to ~8 wt.%, the degree of Pd adsorption decreased to 86.6%. This could be attributed to the binding of Pd²⁺ ions with excess pectin that was not adsorbed onto the ZnO surface. This assumption was further supported by an additional experiment: the clarification of the mother liquor upon ethanol addition to the Pd²⁺–Pec–ZnO system suggested the complete removal of the free Pd–Pec complex via precipitation. During the preparation of bimetallic catalysts, palladium was introduced into the system after copper. In these cases, the amount of palladium introduced was lower, which likely facilitated it’s more complete sorption. As a result, the degree of Pd²⁺ adsorption reached 99–100%. Copper ions were also effectively adsorbed in the PdCu–Pec1.8/ZnO composites, with adsorption degrees ranging from 90% to 96% depending on the Pd:Cu ratio. Based on PEC analysis, the total metal (Pd and Cu) content in the catalysts was approximately 1 wt.%, which was consistent with the results obtained by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental analysis (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of assessing the degree of deposition of palladium and copper ions on ZnO and Pec/ZnO support materials.

Table 2.

Results of assessing the degree of deposition of palladium and copper ions on ZnO and Pec/ZnO support materials.

| Catalyst |

Amount of Metal in Mother Liquor, mg |

The Degree of Adsorption, % |

Pd Content in a Catalyst, %wt. |

| before Sorption |

after Sorption |

PEC |

EDX |

| Pd |

Cu |

Pd |

Cu |

Pd |

Cu |

Pd |

Cu |

Pd |

Cu |

| Pd/ZnO |

10.1 |

- |

0.04 |

- |

99.6 |

- |

1.0 |

- |

0.95 |

- |

| Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO |

10.3 |

- |

0.14 |

- |

98.6 |

- |

1.0 |

- |

0.96 |

- |

| Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO |

10.5 |

- |

0.40 |

- |

96.2 |

- |

1.0 |

- |

0.94 |

- |

| Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO |

11.0 |

- |

1.47 |

- |

86.6 |

- |

0.9 |

- |

0.89 |

- |

| PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

7.7 |

2.6 |

0.08 |

0.24 |

99.0 |

90.8 |

0.74 |

0.23 |

0.71 |

0.24 |

| PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

5.2 |

5.2 |

0 |

0.54 |

100 |

89.6 |

0.50 |

0.45 |

0.52 |

0.56 |

| Pd-Cu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

2.6 |

7.7 |

0 |

0.32 |

100 |

95.8 |

0.25 |

0.72 |

0.17 |

0.81 |

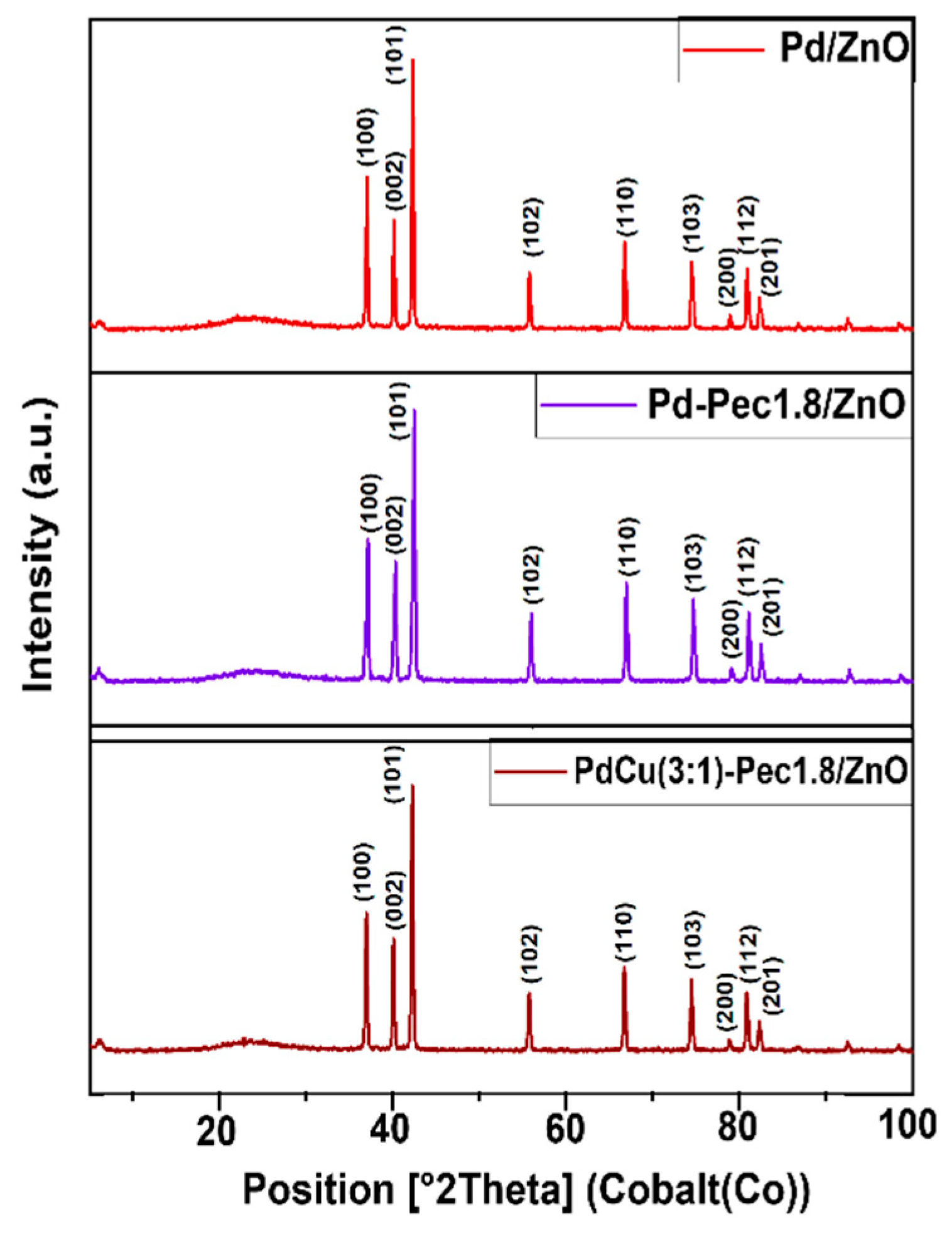

The results of X-ray powder diffraction analysis (XRD) of the Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO are shown in

Figure 3. All XRD patterns showed characteristic peaks at 36.9°, 40.0°, 42.2°, 55.6°, 66.7°, 74.4°, 78.8°, 80.8°, and 82.3°, corresponding to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), and (201) planes of ZnO hexagonal wurtzite structures (JCPDS card no. 79-2205) [

27]. No diffraction peaks corresponding to palladium (Pd or PdO) or copper (Cu, Cu₂O, or CuO) species were observed in the XRD patterns of the catalysts. This absence can be attributed to the low metal content (Pd and Cu) in the samples, as well as the small size and high dispersion of the metal particles [

15].

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

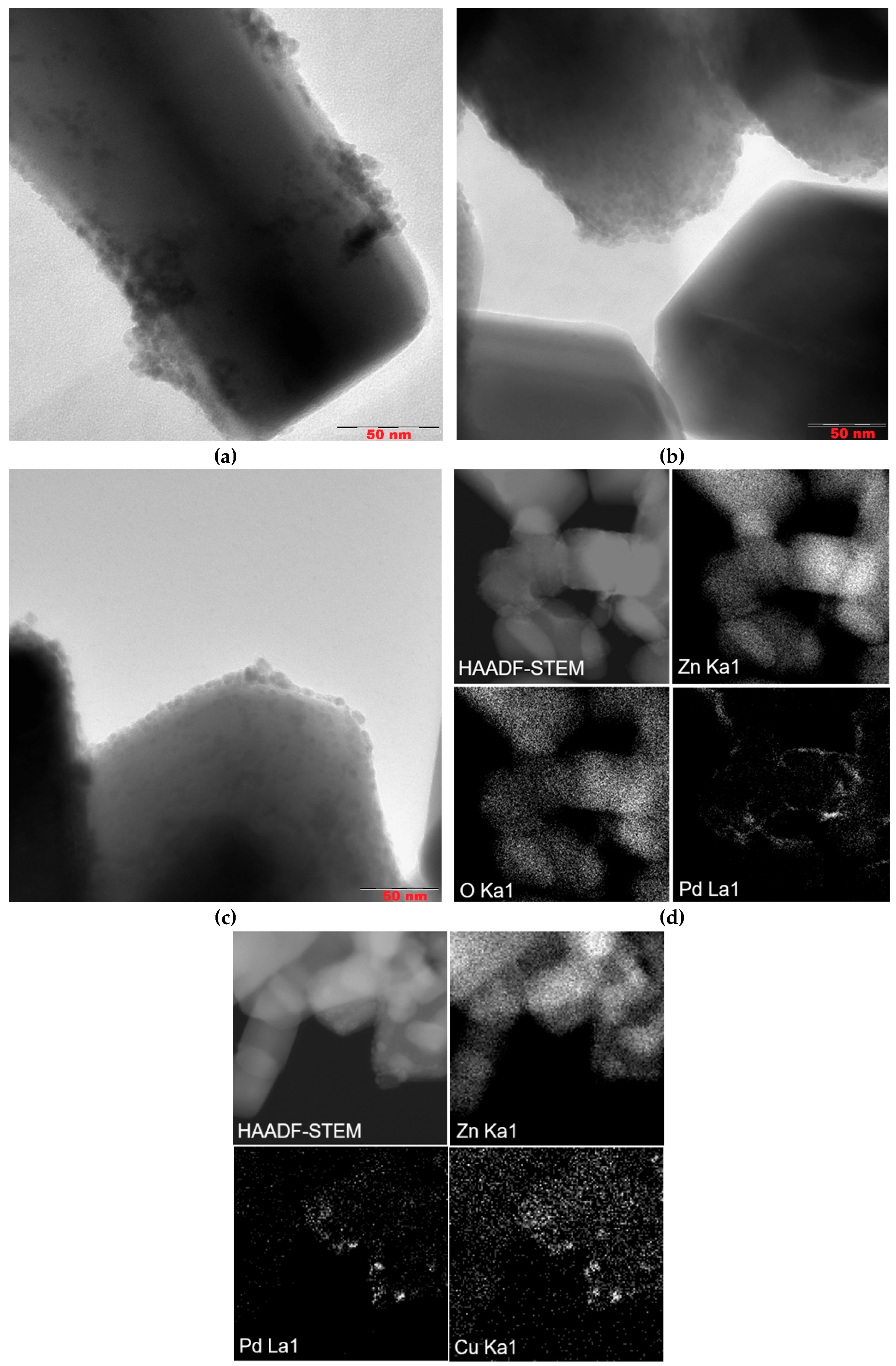

To evaluate the size of metal particles and their distribution of a support surface Pd/ZnO,

Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO were studied using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) method (

Figure 4). Before studies the catalysts were treated with hydrogen (1 atm) in a reactor at 40 °C for 30 min.

Figure 4.

TEM microphotographs (a, b, c), HAADF-STEM and EDX elemental mapping images (d, f) from Pd/ZnO (a), Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO (b, d), and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (c, f).

Figure 4.

TEM microphotographs (a, b, c), HAADF-STEM and EDX elemental mapping images (d, f) from Pd/ZnO (a), Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO (b, d), and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (c, f).

According to TEM studies, the Pd/ZnO catalyst is composed of palladium (Pd) nanoparticles with a primary size of approximately 4–5 nm. These nanoparticles tend to aggregate, forming larger nanoclusters ranging from 10 to 30 nm in size, which are distributed across various sites of the ZnO support. However, in certain regions, Pd nanoparticles remain well-dispersed without forming aggregates (

Figure 4a). In contrast, both the

Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO (

Figure 4b) and

bimetallic PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO (

Figure 4c) catalysts exhibit a uniform distribution of nanoparticles on the ZnO support, with an average particle size of approximately 4 nm. The nanoparticles are predominantly spherical or slightly oval in shape and show no signs of significant aggregation. The use of pectin as a stabilizing agent during synthesis likely contributes to this homogeneous dispersion by preventing nanoparticle growth and aggregation. Elemental mapping analysis of the

Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst (

Figure 4d) further confirms the homogeneous distribution of palladium on the Pec1.8/ZnO support surface. The HAADF-STEM image, along with the corresponding EDX elemental maps for Zn (Zn Kα1), O (O Kα1), and Pd (Pd Lα1), shows that palladium is well-dispersed across the support without evidence of significant aggregation or phase separation. Similarly, the elemental maps of the

PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst (

Figure 4f) show uniform distribution and co-localization of Pd and Cu nanoparticles on the ZnO surface. The overlapping bright spots in the Pd and Cu maps suggest that both metals may be spatially coincident, which could indicate the formation of bimetallic nanoparticles or alloys.

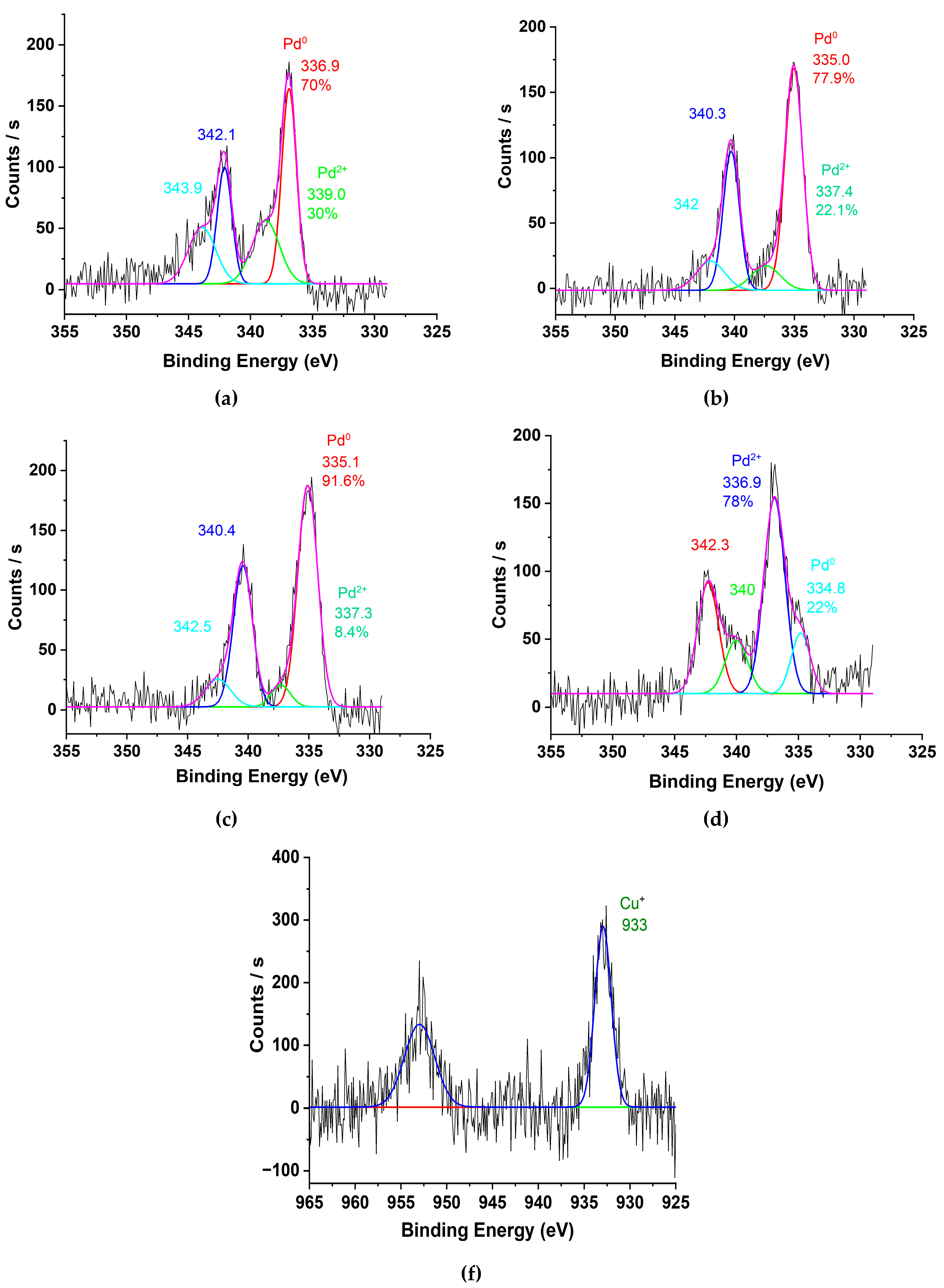

To assess the oxidation states of palladium and copper species during the hydrogenation process, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed. The catalysts (Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO) were pretreated with molecular hydrogen at 40 °C in a reactor prior to XPS analysis. Additionally, untreated Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO was analyzed to determine the effect of hydrogen pretreatment on the Pd species.

Figure 5 shows Pd 3d and Cu 2p regions of the XPS spectra of the catalysts. The deconvoluted Pd 3d signals (

Figure 5a-d) clearly illustrate the different oxidation states of Pd existing on the surface of the catalysts. In the untreated Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd 3d

5/2 peaks with binding energies at 336.9 eV and 339.0 eV can be attributed to Pd in +2 and +4 oxidation states, respectively (

Figure 5a) [

28,

29]. Treatment of the catalyst with molecular hydrogen at 40 °C led to significant changes in the Pd 3d spectral profile (

Figure 5b). The peak at 339.0 eV (Pd⁴⁺) disappeared, and a new peak emerged at 335.0 eV, characteristic of metallic palladium (Pd⁰) [

30,

31]. In the reduced Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO sample, Pd⁰ (335.0 eV) became the dominant species, representing 78% of the surface Pd, while Pd²⁺ (337.4 eV) accounted for 22%. This confirms that hydrogen treatment effectively converts oxidized Pd species (Pd⁴⁺ and Pd²⁺) into metallic Pd⁰, thereby modulating the electronic state of palladium. Such modulation is expected to strongly influence catalytic behavior in hydrogenation reactions. Similarly, the reduced Pd/ZnO catalyst exhibited Pd 3d₅/₂ peaks at 335.1 eV and 337.3 eV, associated with Pd⁰ (92%) and Pd²⁺ (8%), respectively (

Figure 5c). This suggests that the incorporation of pectin did not significantly affect the redox state of palladium after hydrogen treatment. In contrast, modification with copper led to notable changes in the Pd 3d spectral profile. The reduced PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst exhibited Pd 3d₅/₂ peaks at 334.8 eV and 336.9 eV, with Pd²⁺ becoming the predominant species (78%) and Pd⁰ contributing only 22% (

Figure 5d). The shift in binding energies toward lower values, along with the altered Pd⁰/Pd²⁺ ratio compared to the monometallic Pd catalysts, is likely due to

electronic interactions and charge transfer between Pd and Cu species [

32].

The Cu 2p₃/₂ region of the XPS spectrum (

Figure 5f) displays a main peak at

~933 eV with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of

2.1 eV, which is characteristic of

Cu⁺ in Cu₂O [

33]. This suggests that

Cu²⁺ species were effectively reduced to Cu⁺ during H₂ pretreatment, likely facilitated by

hydrogen spillover or direct interaction with Pd⁰ species [34]. This observation supports the possible formation of Pd-Cu alloy compound.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of Pd 3d for (a) untreated Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, (b) reduced Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, (c) reduced Pd/ZnO, and (d) reduced PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO; and Cu 2p for (f) reduced PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of Pd 3d for (a) untreated Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, (b) reduced Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, (c) reduced Pd/ZnO, and (d) reduced PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO; and Cu 2p for (f) reduced PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

2.2. Catalytic Properties of Pd and PdCu Catalysts in Hydrogenation Process

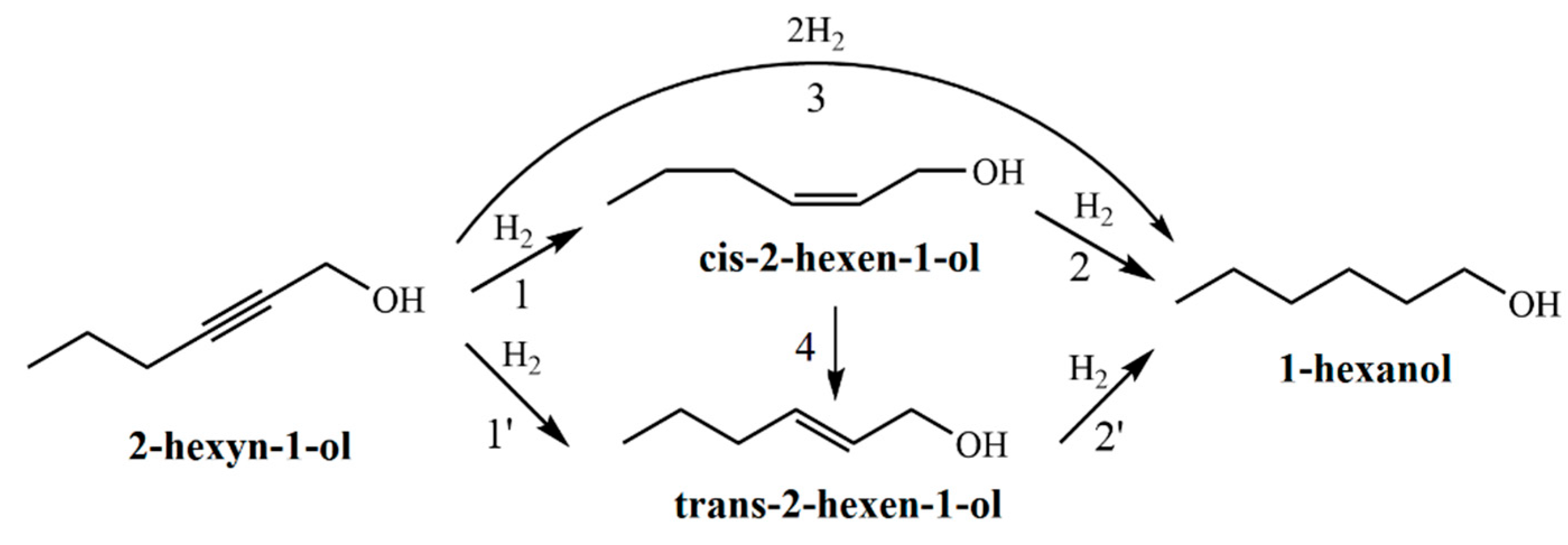

The hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol proceeds via a consecutive reaction pathway (

Figure 6). In the first step, the triple C≡C bond of the acetylenic alcohol is selectively reduced to a double C=C bond, forming both

cis- and

trans- isomers of 2-hexen-1-ol (

Figure 6, reactions 1 and 1′). These intermediates are further hydrogenated to 1-hexanol (

Figure 6, reactions 2 and 2′). Additionally, direct hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol to 1-hexanol without accumulation of intermediates is also possible (

Figure 6, reaction 3). It should also be noted that

cis-2-hexen-1-ol may isomerize to its

trans counterpart under the reaction conditions (

Figure 6, reaction 4).

Figure 6.

Plausible reaction pathways for the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol. 1 and 1′ – hydrogenation of the triple C≡C bond in 2-hexyn-1-ol to form cis-2-hexen-1-ol and trans-2-hexen-1-ol, respectively. 2 and 2′ – hydrogenation of the C=C bonds in cis-2-hexen-1-ol and trans-2-hexen-1-ol, respectively, yielding 1-hexanol. 3 – direct hydrogenation of the triple bond in 2-hexyn-1-ol to 1-hexanol. 4 – isomerization of cis-2-hexen-1-ol to trans-2-hexen-1-ol.

Figure 6.

Plausible reaction pathways for the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol. 1 and 1′ – hydrogenation of the triple C≡C bond in 2-hexyn-1-ol to form cis-2-hexen-1-ol and trans-2-hexen-1-ol, respectively. 2 and 2′ – hydrogenation of the C=C bonds in cis-2-hexen-1-ol and trans-2-hexen-1-ol, respectively, yielding 1-hexanol. 3 – direct hydrogenation of the triple bond in 2-hexyn-1-ol to 1-hexanol. 4 – isomerization of cis-2-hexen-1-ol to trans-2-hexen-1-ol.

To investigate the catalytic performance in these transformations, two sets of catalysts were studied. In the first part, a series of monometallic Pd/ZnO catalysts with varying pectin content were examined to evaluate the effect of pectin modification on activity and selectivity. In the second part, the performance of the optimized monometallic catalyst was compared with bimetallic PdCu-Pec/ZnO catalysts, in which the Pd to Cu mass ratio was systematically varied to assess the influence of copper incorporation on the hydrogenation behavior.

The activity of the catalysts was evaluated by measuring the hydrogen uptake as a function of time. Based on the H₂ consumption data, the reaction rate was calculated. The selectivity of the process was determined by chromatographic analysis of reaction mixtures sampled at different time intervals.

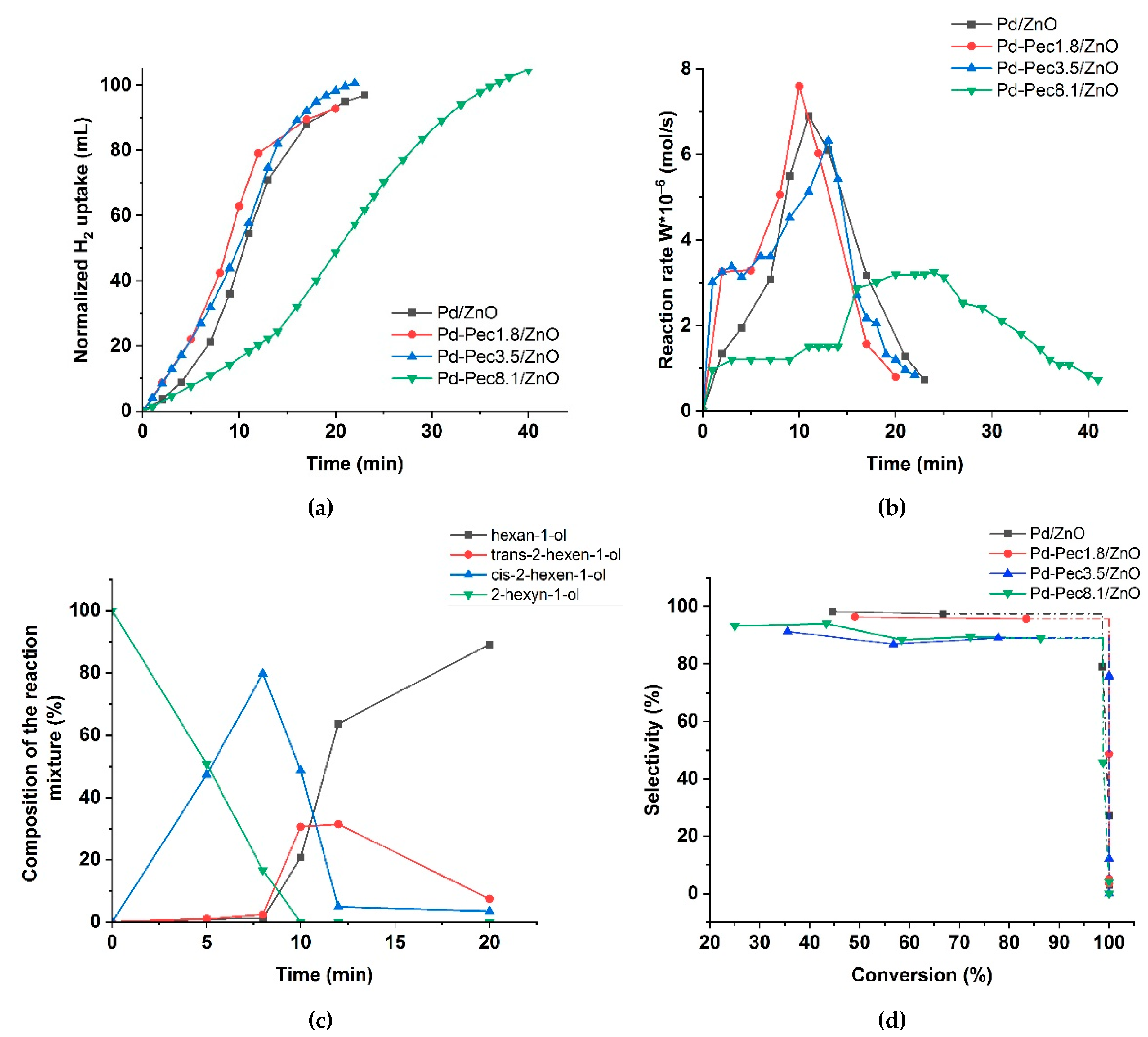

Figure 7 shows the results of testing the monometallic Pd/ZnO catalysts in the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol.

Figure 7a presents the variation in H₂ uptake over time during the reaction. The Pd/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO catalysts with lower pectin content demonstrated higher catalytic activity compared to Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO. The semi-hydrogenation point (50 mL of H₂ uptake) was reached after 8, 9, 10, and 20 minutes for Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO, Pd/ZnO, and Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO, respectively. These results suggest that modification with a small amount of pectin slightly improves the activity of the Pd/ZnO catalyst. However, a further increase in pectin content leads to a decrease in activity, most likely due to the steric hindrance caused by the excess polymer, which limits substrate access to the Pd active sites [

35].

Figure 7b shows the hydrogenation rate (W), calculated from the H₂ uptake data. For all Pd-Pec/ZnO catalysts, the reaction rate increased during the first two minutes and remained nearly constant until the semi-hydrogenation point. Then, the rate increased again, reached a maximum, and subsequently dropped sharply. In contrast, the unmodified Pd/ZnO catalyst exhibited a slower and more gradual increase in reaction rate during the initial period up to the semi-hydrogenation point, without the sharp initial rise characteristic of the pectin-modified samples. This behavior can be attributed to a more uniform distribution of palladium particles on the support surface in the pectin-modified catalyst compared to the polymer-free system, as evidenced by the TEM data (

Figure 4).

Figure 7.

Hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol on Pd/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO catalysts: hydrogen uptake (a); change in

the rate of reaction (b); changes in the composition of the reaction mixture in presence of Pd-Pec/1.8ZnO (c); and

dependence of selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol with the substrate conversion (d). Reaction conditions: 50 mg of

catalyst, 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol, 25 mL of ethanol, at 40 °C and 0.1 MPa.

Figure 7.

Hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol on Pd/ZnO and Pd-Pec/ZnO catalysts: hydrogen uptake (a); change in

the rate of reaction (b); changes in the composition of the reaction mixture in presence of Pd-Pec/1.8ZnO (c); and

dependence of selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol with the substrate conversion (d). Reaction conditions: 50 mg of

catalyst, 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol, 25 mL of ethanol, at 40 °C and 0.1 MPa.

According to chromatographic analysis,

cis-2-hexen-1-ol accumulated in the reaction medium over Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO during the initial period and was subsequently reduced to

1-hexanol (

Figure 7c), which confirmed the occurrence of Paths 1 and 2 in

Figure 6, respectively. The accumulation of cis-2-hexen-1-ol was accompanied by the formation of minor amounts of

trans-2-hexen-1-ol and

1-hexanol, whose yields at the semi-hydrogenation point (8 min) were 2 % and 1 %, respectively, while the yield of cis-2-hexen-1-ol reached 80 %. The appearance of trans-2-hexen-1-ol and 1-hexanol before the semi-hydrogenation point confirmed the occurrence of Paths 1′ and 3 (

Figure 6). After passing the semi-hydrogenation point, a portion of the accumulated cis-2-hexen-1-ol was also converted to trans-2-hexen-1-ol (Path 4), which was eventually reduced to 1-hexanol (Path 2′ in

Figure 6). The composition of the reaction mixture changed similarly on the rest Pd/ZnO catalysts (

Figure S1). The maximum cis-2-hexen-1-ol yields were determined to be 78 % at 11 min for Pd/ZnO, 76 % at 11 min for Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO, and 77 % at 20 min for Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO. These data confirmed that Pd-Pec/ZnO catalysts with lower pectin content (1.8 % and 3.5 wt) exhibited slightly higher activity than Pd/ZnO, whereas Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO demonstrated the lowest activity. The selectivity-versus-conversion curves (Figure 7d) showed that Pd/ZnO (97 %) and Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO (96 %) exhibited higher selectivity toward cis-2-hexen-1-ol compared to Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO (89 %) and Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO (89 %).

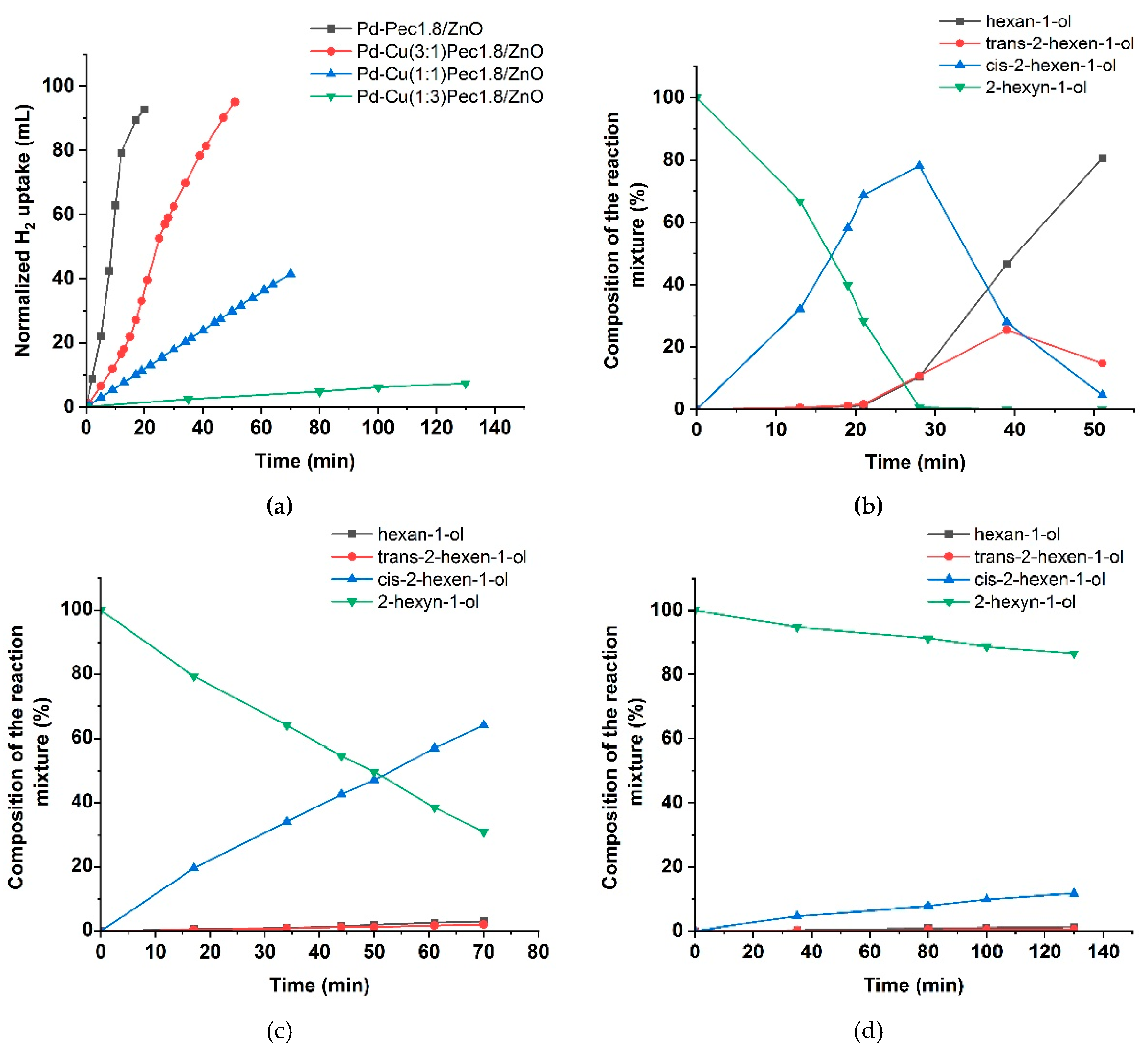

Figure 8 presented the results of testing the bimetallic PdCu-Pec1.8/ZnO catalysts. The modification with copper was shown to be significantly affected the activity of the optimized Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst. Compared to the monometallic Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst, which reached the semi-hydrogenation point in 8 minutes, the bimetallic PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO catalyst required a significantly longer time of 24 minutes under identical conditions. The other bimetallic catalysts exhibited negligible activity. Hydrogen uptake reached 41 mL for PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (after 70 minutes) and 7 mL for PdCu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO (after 130 minutes). This altered behavior can be explained by the effect of copper incorporation, which, according to the XPS data (Figure 5), suppressed the reduction of palladium to its metallic state, thereby reducing the proportion of Pd⁰ species relative to Pd²⁺. The composition of the reaction mixture over PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO changed similarly to that observed for the monometallic analogue, but at a slower rate. The maximum yield of cis-2-hexen-1-ol before reaching the semi-hydrogenation point (24 minutes) was 69% at 72% substrate conversion (data at 21 minutes), corresponding to 96% selectivity toward the target product (

Figure 8b). The yield of cis-2-hexen-1-ol on PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO reached 64% at 69% substrate conversion (70 minutes) (

Figure 8c), whereas for PdCu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO, this value did not exceed 12% even after 130 minutes of reaction (

Figure 8d).

Figure 8.

Hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol on PdCu-Pec1.8/ZnO catalysts: hydrogen uptake (a); changes in the

composition of the reaction mixture in presence of PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (b), PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (c) and

PdCu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO (d). Reaction conditions: 50 mg of catalyst, 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol, 25 mL of ethanol, at

40 °C and 0.1 MPa.

Figure 8.

Hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol on PdCu-Pec1.8/ZnO catalysts: hydrogen uptake (a); changes in the

composition of the reaction mixture in presence of PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (b), PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO (c) and

PdCu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO (d). Reaction conditions: 50 mg of catalyst, 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol, 25 mL of ethanol, at

40 °C and 0.1 MPa.

The hydrogenation rate and selectivity of the catalysts, calculated from hydrogen uptake and chromatographic analysis data, respectively, are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

A comparison of catalytic properties of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec/ZnO and PdCu-Pec1.8/ZnO catalysts in hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol.

Table 3.

A comparison of catalytic properties of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec/ZnO and PdCu-Pec1.8/ZnO catalysts in hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol.

| Catalyst |

W × 10−6, mol/s |

Selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol, % |

Conversion*, % |

| C≡C |

C=C |

| Pd/ZnO |

2.0 |

6.9 |

97 |

67 |

| Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO |

3.3 |

7.6 |

96 |

83 |

| Pd-Pec3.5/ZnO |

3.3 |

6.3 |

89 |

78 |

| Pd-Pec8.1/ZnO |

1.2 |

3.2 |

89 |

86 |

| PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

1.2 |

2.4 |

96 |

72 |

| PdCu(1:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

0.4 |

- |

93 |

69 |

| Pd-Cu(1:3)-Pec1.8/ZnO |

0.1 |

- |

87 |

13 |

| *— The value of the substrate conversion used for the calculation of selectivity of the catalysts. Reaction conditions: 50 mg of catalyst, 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol, 25 mL of ethanol, at 40 °C and 0.1 MPa. |

Modification with a minimal amount of pectin (1.8%) led to a slight improvement in the activity of the Pd/ZnO catalyst, while maintaining similarly high selectivity toward cis-2-hexen-1-ol. The increased activity can be attributed to the stabilizing effect of pectin, which promoted a more uniform distribution of palladium particles on the support surface. However, further increasing the pectin content to ~8% resulted in decreased activity and selectivity. This effect is likely due to steric hindrance restricting substrate access to the active sites caused by excess polymer. The addition of copper caused a significant decrease in catalyst activity, which is attributed to its influence on the state of the palladium active sites. At the same time, selectivity was not improved and even decreased for samples with higher copper content.

2.3. Perfomance of the Catalysts in Photocatalytic H2 Production

Before conducting photocatalytic H

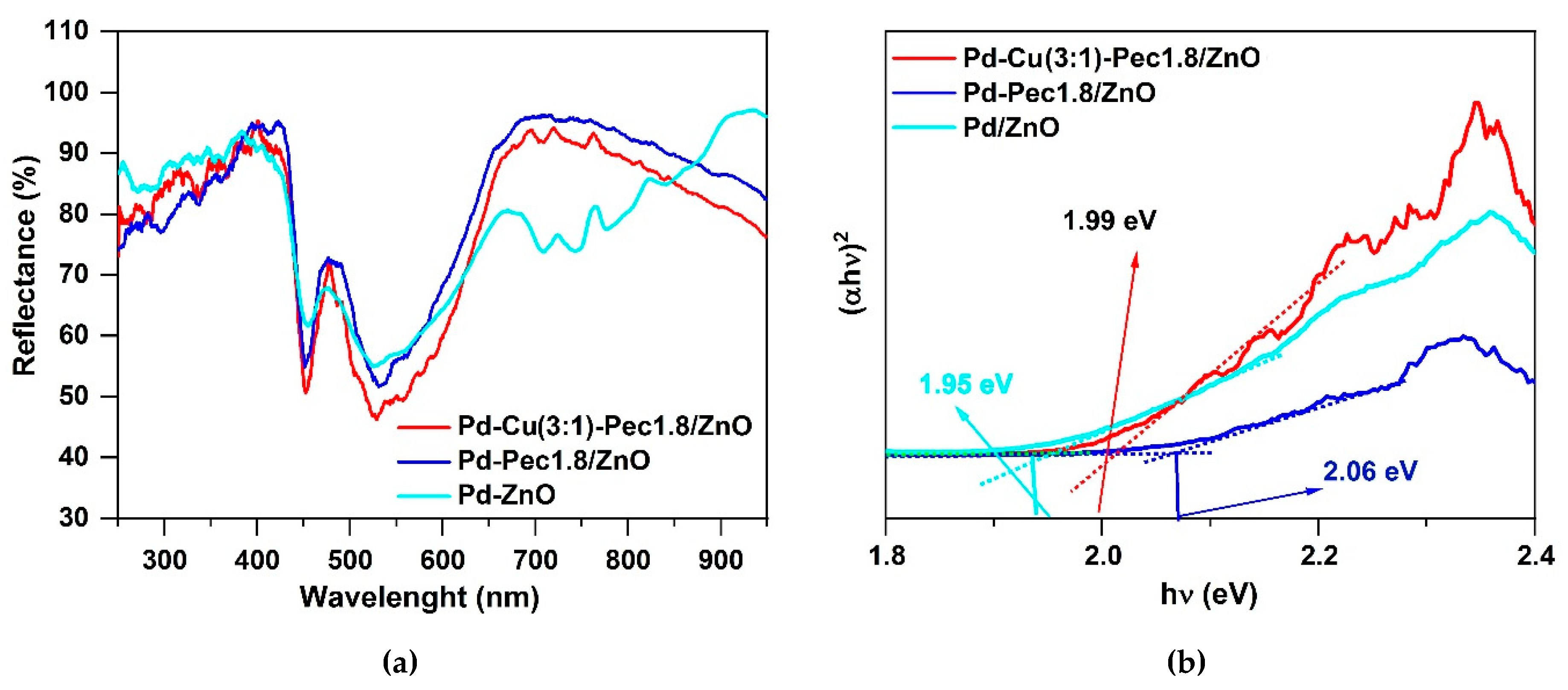

2 evolution experiments, the optical properties of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Cu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO were evaluated using Ultraviolet–Visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis DRS) method (

Figure 9).

Figure 9.

UV-vis reflectance spectra (a) and Tauc plots (b) for Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Cu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

Figure 9.

UV-vis reflectance spectra (a) and Tauc plots (b) for Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Cu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO.

Figure 9a shows the UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of the catalysts. Compared with the literature data for pristine ZnO, where the absorption edge is typically observed at ~380–400 nm [

36], a noticeable red shift of the absorption edge to ~430–450 nm is observed for all palladium-containing samples. This shift may be attributed to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of metallic Pd nanoparticles, which extends the light absorption into the visible region [

37]. The Pd/ZnO sample exhibits three distinct absorption bands (observed as reflectance minima) in the regions of approximately 400–500 nm, 500–600 nm, and 650–800 nm. These features likely originate from the superposition of interband transitions in ZnO, SPR of Pd, and possibly electronic transitions associated with palladium aggregates formed on the ZnO surface [

37]. Interestingly, in the pectin-modified samples (Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO), the broad absorption band in the 650–800 nm region is absent. This disappearance is probably due to stabilization role of pectin, preventing aggregation of Pd nanoparticles on ZnO surface (

Figure 4) and the formation of larger plasmon-active domains. Tauc plot analysis (

Figure 9b) showed that the band gap values were 1.95, 1.99 and 2.06 eV for Pd/ZnO, PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, respectively. All values are significantly lower than that of pristine ZnO (~3.37 eV) [

37], confirming the strong modifying effect of metal nanoparticles and Pec component on the electronic structure of ZnO.

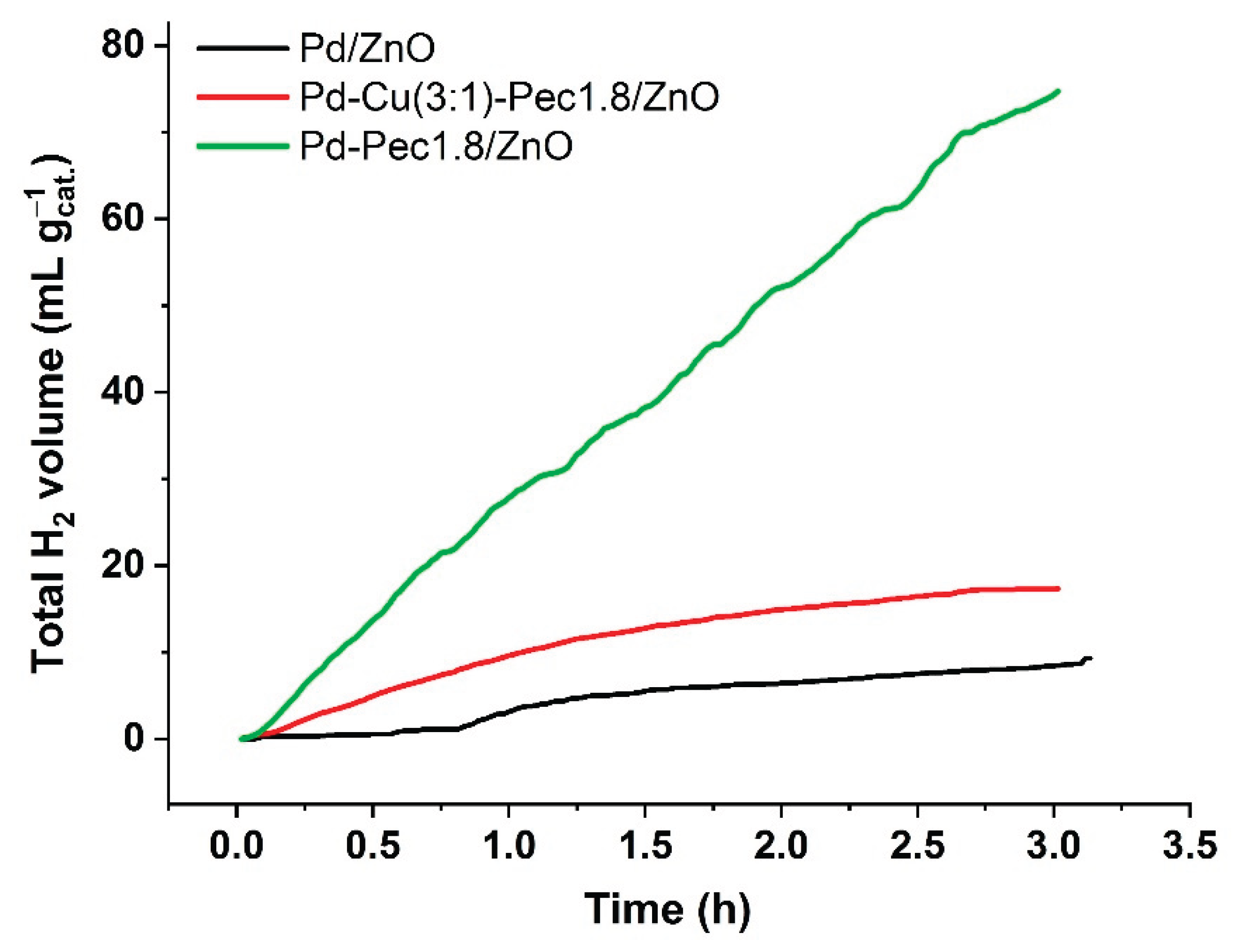

Despite having the

widest band gap, Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO demonstrated the

highest photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution under visible-light irradiation. Conversely, Pd/ZnO, with the

narrowest band gap, was the least active, while the bimetallic Pd–Cu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO sample showed

intermediate performance. The total amount of hydrogen produced within 3 h was 74.7, 17.3, and 9.3 mL/g

cat for Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO, PdCu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO, and Pd/ZnO, respectively (

Figure 10). Accordingly, the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution rate (PCHE) followed the order: Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO (1.11 mmol/h g

cat) ≫ PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO (0.26 mmol/h g

cat) > Pd/ZnO (0.14 mmol/h g

cat).

Figure 10.

Photocatalytic H2 production efficiency of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Cu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO. Reaction conditions: 70 mg of photocatalysts in 0.35 M Na2S and 0.25 M Na2SO3 aqueous solution, pH = 13, and light source—Xenon device (1000 W/m2).

Figure 10.

Photocatalytic H2 production efficiency of Pd/ZnO, Pd-Pec1.8/ZnO and Pd-Cu(3:1)-Pec1.8/ZnO. Reaction conditions: 70 mg of photocatalysts in 0.35 M Na2S and 0.25 M Na2SO3 aqueous solution, pH = 13, and light source—Xenon device (1000 W/m2).

Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO and PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO demonstrated higher photocatalytic performance compared to Pd/ZnO. According to TEM studies (

Figure 4), in both pectin-modified samples metal nanoparticles (Pd and Cu) with an average size of ~4 nm were uniformly dispersed over the ZnO surface. In contrast, for Pd/ZnO, Pd nanoparticles (~4–5 nm) tended to form larger aggregates with sizes up to 10–30 nm. This clearly indicates that the catalysts’ performance is primarily governed by their

morphological and structural characteristics, rather than by differences in band gap values.

However, between the two pectin-modified samples, Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO exhibited superior activity compared to PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO, despite having a similar nanoparticle size and dispersion. XPS analysis provides insight into this difference (

Figure 5). After H₂ treatment, both catalysts contained Pd⁰ species, which are known to act as efficient electron traps [

38]. In Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO, metallic Pd⁰ was the dominant species (~78%), while in PdCu(3:1)–Pec1.8/ZnO, the proportion of Pd⁰ was significantly lower (~22%). In the latter, Cu was detected as Cu⁺ (Cu₂O), indicating strong electronic interactions between Pd and Cu. These interactions result in a more “oxidized” Pd surface, which likely reduces the density of metallic electron traps and suppresses Pd⁰-mediated catalysis. This explains the lower photocatalytic activity of the bimetallic sample, despite the potential electron-mediating role of Cu⁺.

In summary, the superior activity of Pd–Pec1.8/ZnO can be attributed to: (i) enhanced light absorption in the visible region, likely resulting from the plasmonic effect of Pd nanoparticles; (ii) more uniform dispersion of Pd nanoparticles, leading to improved charge separation and efficient utilization of active sites; (iii) absence of Pd–Cu interactions, which in the bimetallic sample hinder the reduction of Pd²⁺ to catalytically active Pd⁰, thereby limiting the formation of effective electron traps.