1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly the wave of technologies represented by language models (LMs), is profoundly transforming various sectors [

1,

2,

3]. In the surgical domain, which demands exceptional precision and experience, LMs have demonstrated immense potential [

5]. It not only assists surgeons with precise and intraoperative decision-making, but also plays a crucial role in postoperative review and training [

4,

9]. By conducting in-depth analysis of large surgical data, AI can help junior surgeons rapidly learn from expert experience, thereby enhancing their surgical skills and advancing the general standard of surgical practice [

6,

7].

Endoscopic surgery is a delicate and complex procedure. Surgeons must navigate through a narrow corridor surrounded by critical neurovascular structures, which demands extremely high precision and dexterity [

8]. Furthermore, the two-dimensional (2D) view provided by the endoscope poses significant challenges to the surgeon’s depth perception and spatial awareness, where even minor errors can lead to severe complications [

10]. The steep learning curve associated with these technical complexities [

43,

57], combined with the scarcity of expert surgeons available for mentorship, creates a significant bottleneck in surgical training [

11]. Junior doctors often lack sufficient opportunities for in-depth review and personalized feedback on complex procedures [

12,

14]. This highlights a pressing need for intelligent tools that can scale expert knowledge and support postoperative review and training.

To address these challenges, Visual Question Answering (VQA) has emerged as an advanced human-computer interaction paradigm for analyzing endoscopic surgery. As a promising approach for postoperative review and training, this paradigm aims to leverage some language models integrated with rich modality information. Existing SOTA models [

4,

15] primarily utilize visual-language information fusion techniques based on static images. These works have pioneered the feasibility of using visual-language information for postoperative review and training and form the foundation of research in this field.

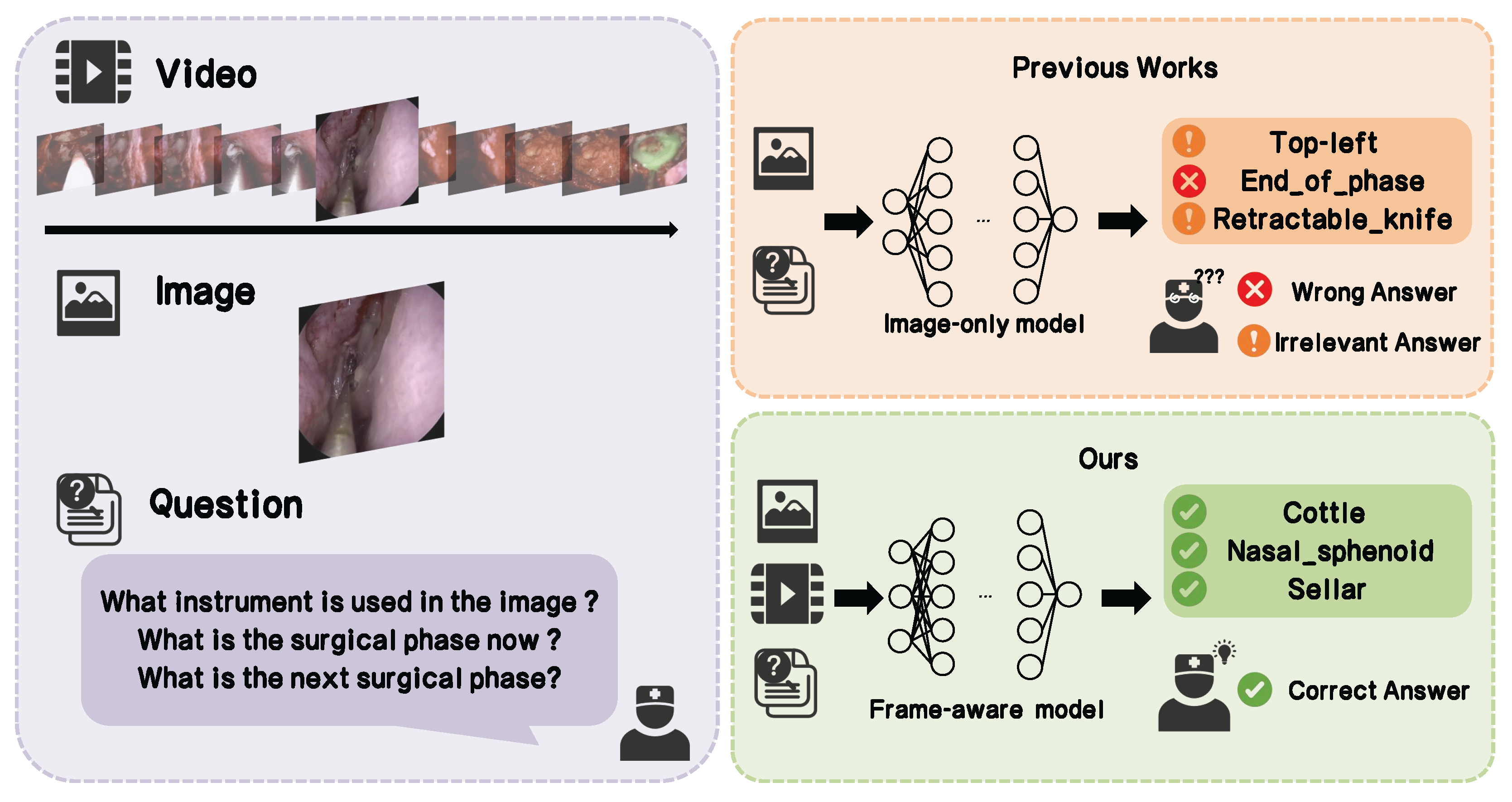

However, these models share a fundamental limitation: they primarily rely on discrete static images. This approach is ill-suited for endoscopic surgery, an inherently dynamic and continuous process where instrument movements, tissue changes, and strategic maneuvers create complex long-range dependencies [

16]. Analyzing frames in isolation omits this crucial temporal context and fails to capture the intricate tool-tissue interactions that define surgical activities. Consequently, models’ capacity for true scene understanding is constrained, limiting their ability to perform nuanced assessments of complex surgical procedures [

17]. This results in a high error rate and irrelevance in model responses, which affects postoperative review and training. A typical example of this, as illustrated in

Figure 1, is when models confuse the type of the question asked and give an irrelevant answer.

To overcome these limitations and bridge this critical gap, we propose SFN-ESVQA, an innovative framework that integrates the video modality into the surgical VQA pipeline by using a frame-aware network. Meanwhile, we design a loss function to reduce the likelihood of the model generates irrelevant responses, and devise a new metrics to conduct a more comprehensive evaluation. Our main contributions are threefold:

We propose a frame-aware network named SFN-ESVQA, which effectively incorporates video data to capture the temporal dynamics of surgical procedures. With frame-aware sampling, the network samples the selected frames and then fuses the video modality and image modality into visual embedding, integrating the visual feature and textual feature by proposed visual guided attention, resulting in better understanding of the question and the video.

We design a standardized evaluation protocol and introduce a novel metric, Irrelevant Answer Rate (IAR), to quantify the frequency of irrelevant responses. Meanwhile we propose a tailored loss function that explicitly penalizes such irrelevant outputs to enhance our model’s ability to generate the appropriate answer.

Extensive experiments are conducted based on the PitVQA [

4] and EndoVis18-VQA [

18] datasets. We achieved improvements of 35.28% and 27.83% in balanced accuracy, and 25.44% and 29.86% in F1-score across the two datasets, demonstrating the great potential for its application in the field of postoperative review and training.

2. Related Work

2.1. Medical Image-Text VQA

Medical Visual Question Answering (VQA) lies at the convergence of computer vision, natural language processing, and clinical practice. It holds great promise for applications such as clinical decision support and postoperative review [

19,

20]. A typical VQA model consists of an image encoder, a question encoder, a fusion module, and an answer decoder [

21,

22].

Medical VQA should be differentiated from related tasks, such as Visual Question Generation (VQG), which generates questions based on images [

23,

24], and Visual Question Localized Answering (VQLA) [

25], which requires both an answer and its spatial location.

Early Medical VQA systems relied on CNNs for image encoding [

27] and RNNs [

28] (for example LSTM [

29], GRU [

30]) for text processing. For example, Neural-Image-QA [

31] used a CNN-LSTM pipeline to answer visual questions end-to-end.

The introduction of Transformers marked a major shift, enabling more powerful cross-modal modeling [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. BERT-based models such as VisualBERT [

38] demonstrated great performance gains in medical VQA tasks. However, many of these models still depend heavily on region-based object detectors (e.g. Faster R-CNN [

40]) and Bottom-Up features, which are less practical in surgical scenarios.

To reduce region-based object detector dependence, detection-free surgical models learn end-to-end from global image features, removing the need for bounding-box annotations such as attention-based model named MedfuseNet [

41] with CNN and MMBERT [

42].

Surgical-VQA[

17] also introduced a detection-free architecture, removing the dependency on pre-annotated regions and facilitating efficient model training. Surgical-VQLA[

44] and CAT-ViL[

45] further advanced the task from traditional VQA (answering "what") to VQLA as we mentioned before, requiring both an answer and its spatial localization in the image. To enhance modality fusion, Surgical-VQLA adopted a gated embedding mechanism to dynamically balance textual and visual inputs, while CAT-ViL leveraged co-attention to guide visual focus through textual context.

With the rise of language models, recent research has explored their integration into VQA tasks. Early approaches, such as SurgicalGPT [

15] and PitVQA-Net [

4], employed adaptation strategies that reordered input tokens or generated image-aware text embeddings to align visual and language modalities. More recent work has focused on fine-tuning large vision-language models (LVLMs) (e.g. Qwen-VL [

46]) for surgical domain, which provides strong general-purpose vision-language capabilities. Surgical-LVLM [

16] enhances surgical reasoning by introducing domain-specific tuning modules, including VP-LoRA and Token Interaction.

Despite notable progress, medical VQA is largely constrained by static image formulations that overlook temporal context. Capturing the continuity of tool–tissue interactions therefore requires the introduction of video modal in endoscopic surgery.

2.2. Videos on Endoscopic Surgery

Video records of clinical surgeries are very valuable, particularly in the aspect of endoscopic surgery, and can be archived and used later for reasons such as postoperative review and training, skills assessment, and workflow analysis [

47].

Currently, the surgical video application paradigm is under profound transformation: from traditional passive review and manual inspection toward intelligent analysis driven by data and empowered algorithms [

13,

49]. Kamtam et al. [

39] conducted a survey of the literature from 2014 to 2024 on anatomical structure segmentation [

32,

48] and object detection in surgical videos, demonstrating the feasibility and growing potential of surgical video analysis. In fact, the field has seen rapid progress in various automated tasks, including surgical phase recognition [

50], instrument tracking [

51], surgical skill assessment [

52], and the detection of critical events such as bleeding or other complications [

53].

However, these methods focus mainly on providing pre-defined, high-level outputs, such as classifying a video segment into a specific surgical phase or identifying a known type of event [

54]. They lack the capability for fine-grained, interactive querying that is essential for nuanced postoperative review and training. For example, a trainee cannot ask a standard phase recognition model why a surgeon chose a particular instrument at a specific moment or what the anatomical structure to the left of the forceps is. This limitation highlights a critical gap: the need for a system that can understand surgical videos dynamically and engage in a natural language dialogue to answer specific, ad-hoc questions.

2.3. Compared with Video-Grounded QA: Focusing on Frame-Aware

In recent years, Video-Based Question Answering (Video VQA) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for understanding complex visual content in a temporally coherent manner. This paradigm, which has emerged as a prominent direction in vision language understanding [

55], provides the foundational techniques for building interactive and dynamic analysis tools.

Early Video QA work [

56,

58,

59] primarily utilized attention mechanisms and RNN-based architectures to enhance cross-modal reasoning between videos and questions. However, the use of recurrent models limited their ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies in extended video sequences. Later works introduced memory networks and Transformer-based architectures to address these issues. Tapaswi et al. [

60] employed memory networks to model visual linguistic context in movie scenes, while more recent models such as PSAC [

61] and ClipBERT [

62] used self-attention and cross-modal pre-training to improve temporal alignment and reasoning.

However, directly applying such video-level QA methods to endoscopic surgical scenes faces significant practical and conceptual challenges. Annotation is costly, requiring expert-level knowledge and frame-level precision. Surgical videos are characterized by high temporal density, and relevant events are typically limited to short time spans. Although some degree of long-range temporal modeling remains necessary, surgical QA primarily demands fine-grained, local reasoning due to the densely packed and event-focused nature of surgical videos. These limitations motivate an approach that prioritizes not only long-term context, but also frame-level understanding over global video reasoning.

3. Method

In this section, we will first formalize the task and introduce our motivation. We then present the general framework of our approach named SFN-ESVQA. Finally, we detail the key components of our framework, including the multi-modal feature encoding, the fusion module, and the answer generation process with the GPT-2 based decoder.

3.1. Overview

3.1.1. Challenges and Overview

Given a surgical endoscopic video and a target frame associated with a textual question "What is the surgical phase now", "what instrument used in the image", but with current existing VQA model, we will encounter these challenges.

Limited temporal understanding. Most methods process frames in isolation or with naive sampling, failing to capture long-range temporal cues critical for interpreting surgical workflow.

Insufficient cross-modal integration. Visual and textual features are often fused late or without adaptive weighting, which weakens the alignment between the question and relevant visual regions or frames.

Weak control over answer relevance. Models may output syntactically valid but semantically irrelevant answers, especially when visual context is ambiguous or dominated by spurious cues.

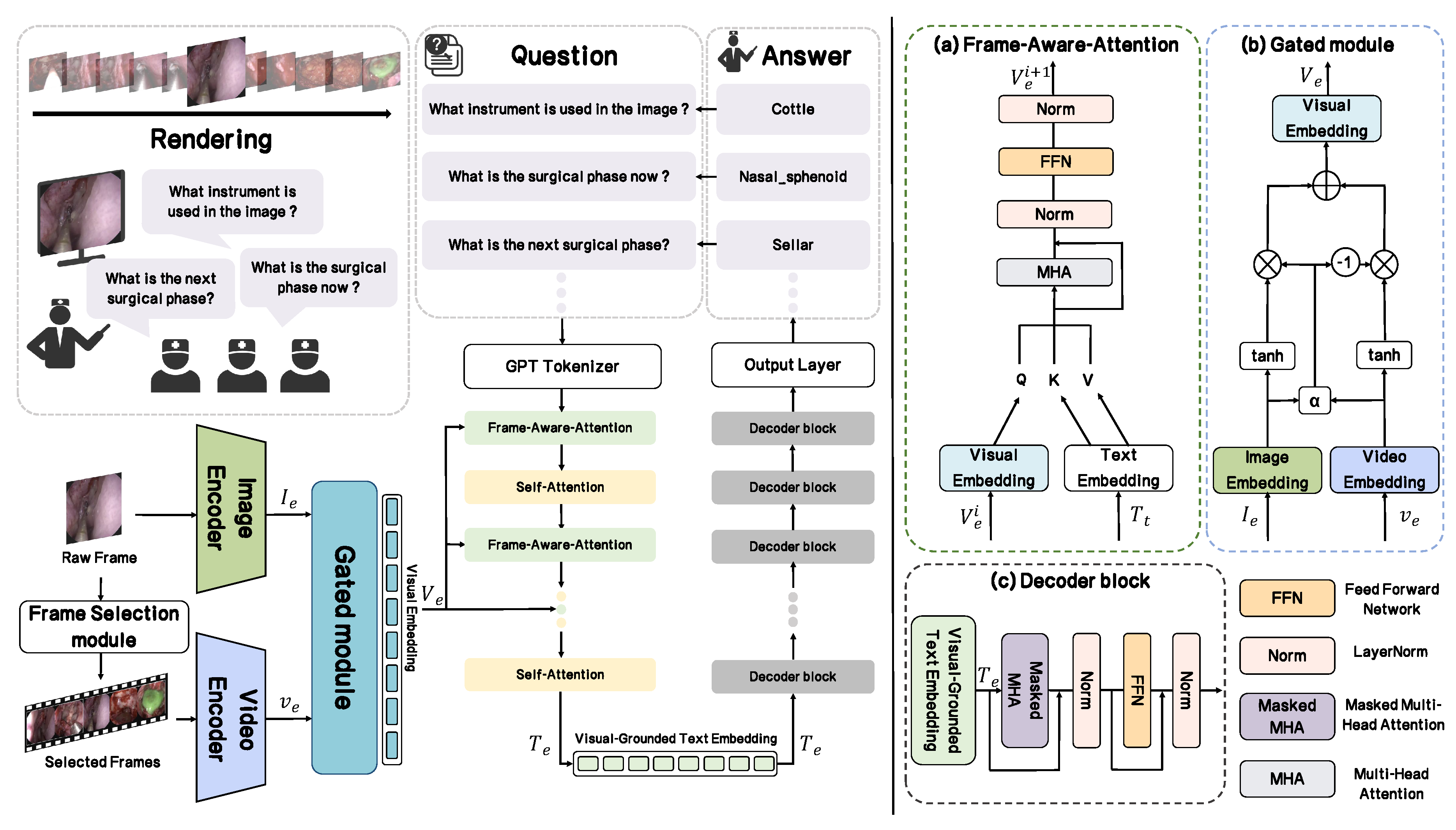

To address these issues, our framework combines a Frame-Aware Sampling module for selecting temporally consistent key frames, a multi-modal gated fusion mechanism for adaptive video–image–text integration, and an Irrelevant Answer Regularization loss to explicitly suppress irrelevant predictions.

Figure 2.

The overall architecture of our proposed SFN-ESVQA framework. It consists of a multi-modal feature encoding module, a fusion module, and a GPT-2 based answer generation decoder.

Figure 2.

The overall architecture of our proposed SFN-ESVQA framework. It consists of a multi-modal feature encoding module, a fusion module, and a GPT-2 based answer generation decoder.

3.1.2. Framework

In this section, we provide an overview of the proposed framework, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Given an input raw video which is shaped as

,where

H and

W are the height and width of frames,

N and

C denote the number of frames and input channels.

The input raw image that we want to ask questions about

will go through the Image Encoder

and encoded as

, and it is defined as follows:

Based on the input frame and the entire video, we propose a frame selection module with frame-aware sampling approach denoted as

to select some key frames and concatenate them into the selected video

:

Then

is passed to the Video Encoder

and we could get a sequence of features from the selected video

with

d dimension:

After that, all these embeddings will be passed into a specially designed module named Gated module

and these two visual features are fused into Visual Embedding

:

In addition to the visual pathway, we introduce a textual pathway to model the input question. Firstly, the GPT tokenizer will convert the input question

into a sequence of token indices

, where

. Each token index will be mapped to feature vector

using the Text Embedding Matrix

:

Subsequently, the Visual-Guided Text Encoder (VGTE), denoted as

, fuses the textual embedding and the visual embedding with a frame consisting of self-Attention layer and Frame-Aware-Attention. This process generates the final Visual-Grounded Text Embedding expressed as

, where the textual representation is grounded in the visual context:

We send Visual-Grounded Text Embedding into the Decoder which is composed of a stack of identical GPT-2 Blocks. Like the VGTE encoder, it also has 12 layers. What follows after is an output layer, we could get the answer

A we want with it:

3.2. Understanding Surgical Video: Frame-Aware-Sampling

In order to understand the surgical video and capture temporal features, we need to choose some key frame. We proposed a Frame-Aware-Sampling approach, which relies on a specially designed score to choose Frame. The score is defined as follows:

where

is the frame

and

denotes one of the frames

around

, We calculate their average Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) as temporal consistency. After that we apply a weight

on its normalized distance with our current frame

(Input frame), where

L is the length of all frames.

Then we select the top-16 frames according to the score

, concatenate them to the selected video

as follows:

With this individual method to sample, our model gets a valuable temporal feature to level up the comprehension with the input image and the textual question.

3.3. Fusion for Dynamic Visual Representation: Gated Module

To effectively leverage the complementary nature of dynamic temporal context and static spatial details, we introduce a novel Gated Module.

As illustrated in

Figure 2(a), the module computes a gating weight, denoted

, which modulates the information flow of each visual stream. This allows the model to learn the optimal fusion strategy for any given input, thereby generating a more nuanced and context-aware visual representation.

The process begins by taking the previous extracted video features

and input image features

, where

are the number of patch tokens for both video and image, and

d is the dimension of the feature vector. Both feature sets are first passed through a hyperbolic tangent (

) activation function, normalizing them to [-1,1]. This step enhances training stability and introduces non-linearity:

To ensure dimensional consistency for the gating mechanism, we first apply global average pooling to video feature , obtain single-vector representations .

The core of our module is the weight of the gate

, which is calculated by feeding the concatenated pooled features into a small neural network followed by a sigmoid activation function. This ensures that

is a scalar value between 0 and 1. The computation is formalized as follows:

here

presents the concatenation operation,

and

are learnable parameters.

is a sigmoid function. The resulting

acts like a soft, data-driven "gate".

Then two processed features are passed into the module with the gating switch

to produce fused visual embedding

as follows:

3.4. Multi-Modal Fusion: Visual-Guided Text Encoder

After we get multi-modal information, all embeddings will be passed to the Visual-Guided Text Encoder which we have mentioned above. The entire fusion encoder is composed of a stack of interleaved Self-Attention layer and Frame-Aware-Attention layer that specially designed by us.

Firstly, the input visual embedding and text embedding are processed. This step allows the model to capture the internal dependencies within the visual embeddings, capturing a contextually aware visual representation.

Following self-attention, the crucial step of cross-modal fusion occurs [

26]. The refined textual embedding

is used to generate the query (

Q), while the fused visual embedding

is seen as the source for the key (

K) and value (

V). The Frame-Aware-Attention consists of a multi-head attention mechanism, a normalization layer(LN), and a feed forward network (FFN) to continue the encoding process. It can be formulated as follows:

where

i represents the attention layer index, ranging from 1 to 12, and

and

represent the input Visual Embedding

and output Visual-Grounded Text Embedding

.

After passing through 12 attention layers, organized into 6 alternating rounds, we get final Visual-Grounded Text Embedding and it will passed to the Decoder.

3.5. Answer Generation: Decoder and Output Layer

The decoder employs a masked version of multi-head attention which is crucial for generating a coherent sequence of text one token at a time. The operation can be formalized as follows:

where

i represents the block index, ranging from 0 to 11, and

and

represent the input Visual-Grounded Text Embedding

and decoder output

.

The last component of the framework is an Output Layer. With a pooling operation we could get a single feature vector

, and it will be sent to a classification head to get the answer:

3.6. IAR Loss: Relevance-Aware Answer Regularization

We designed a specialized loss function, called the IAR loss and it is defined as follows:

where

is the one-hot encoding of the actual label. If the sample belongs to class

i, then

, otherwise

, and

and

is the predicted probability of

and number of actual label. The

is the one-hot encoding of the category of actual label. If the actual label belongs to category

j, then

, otherwise

, and

and

is the summary of predicted probability of

and number of category of actual label, here

(label

i belongs to category

j ).

Compared with simply penalizing incorrect answers, this loss imposes an additional penalty on responses that are irrelevant to the question, thereby enabling our model to more effectively guard against irrelevant answers during the VQA process.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset Description

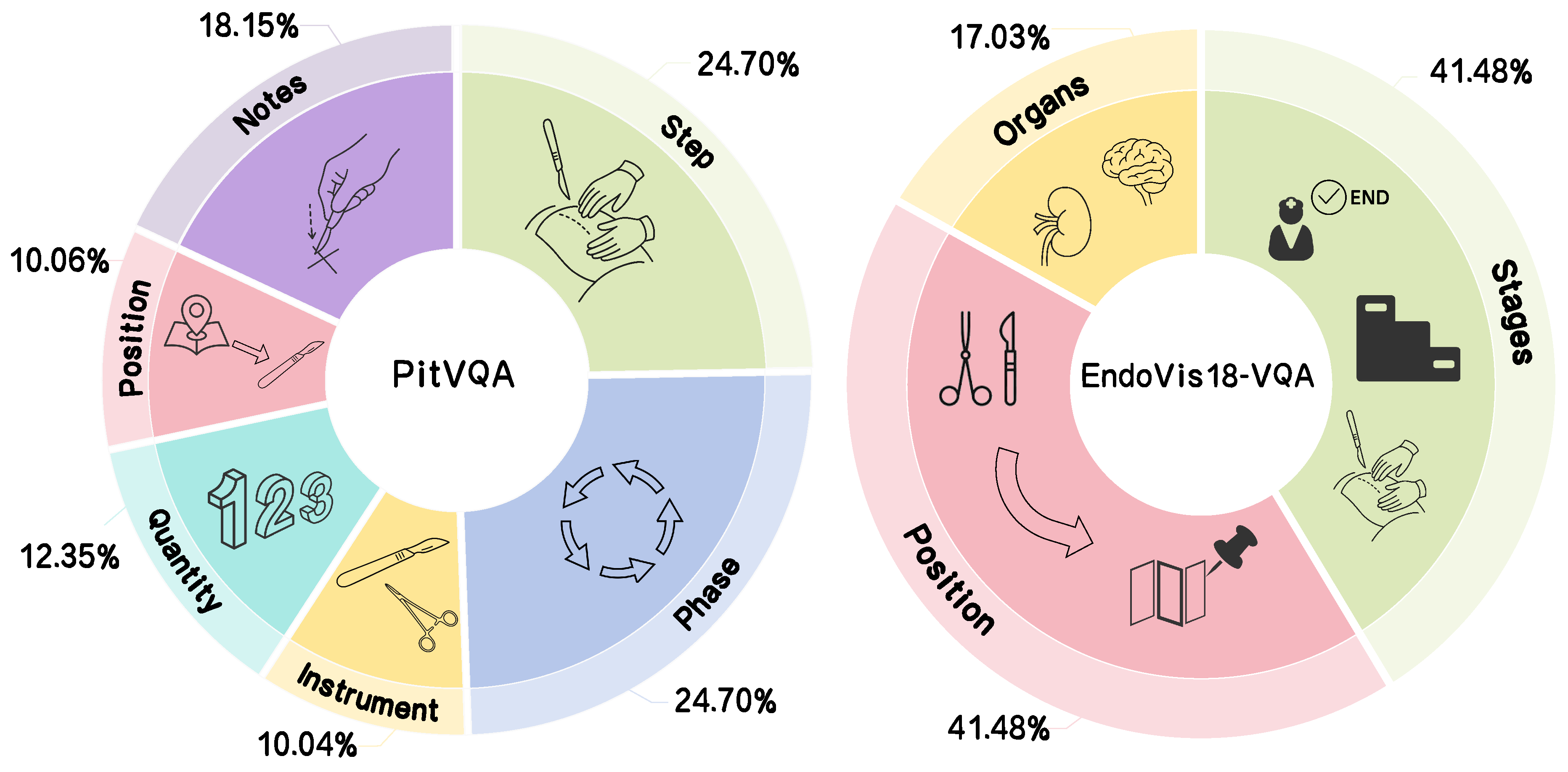

We evaluated our approach on two publicly available surgical VQA datasets, illustrated in

Figure 3 :

PitVQA [

4] and

EndoVis18-VQA [

18], to assess generalization across procedures and data sources.

PitVQA contains endonasal pituitary surgery videos from 25 cases, recorded with an HD endoscope. Frames are sampled at 1 fps, yielding 109,173 images and 884,242 per-frame question–answer pairs across six categories: phase, step, instrument, instrument quantity, instrument position, and operation notes, for a total of 59 answer classes. We follow the official video-level split of 20 sequences for training and 5 for validation.

EndoVis18-VQA is derived from the MICCAI 2018 Robotic Scene Segmentation Challenge and consists of 14 robotic surgical video sequences (stereo, 1280×1024). Its VQA subset includes 2,007 frames and 11,783 single-word QA pairs covering 18 answer classes: organ (1), tool–tissue interactions (13), and instrument locations (4). We follow the standard split of 1,560 frames/9,014 QA for training and 447 frames/2,769 QA for validation.

4.2. Implementation Details

The implementation and pre-trained weights of our backbone networks are adopted from the official repositories of Huggingface GPT 2. Our model is trained with our proposed loss function and optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of .

In order to obtain a comprehensive performance comparison and evaluation, we selected closely related SOTA surgical VQA models such as PitVQA-Net [

4], SurgicalGPT [

15] to retrain using official repositories. In addition, we adopted the results of other recent baselines, including Mutan [

63], MFB [

64] and MFH [

65]. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate our model’s capability, we selected some typical metrics such as F1-score (F1), Balanced Accuracy (B.Acc) and Recall (Rec).

F1-score:F1 summarizes precision and recall as their harmonic mean, where

,

. It is defined as follows:

Balanced Accuracy:B.Acc averages per-class recall to reduce the effect of class imbalance, where C is the number of classes,

indexes classes,

and

denote the true positives and false negatives for class

c under a one-vs-rest view. This metric is defined as follows:

Recall:Recall measures how well the model retrieves relevant positives:

Irrelevant Answering Rate:In addition, we introduced a special evaluation metric named Irrelevant Answering Rate (IAR). This metric measures the proportion of irrelevant answers among all incorrect responses. An answer is deemed irrelevant if its semantic category does not match the question’s expected answer type. IAR is calculated as:

where

refers to these generated answers which falls outside the expected answer category, and

denotes the number of answers that match the expected answer type yet but contain incorrect content.

These metrics offer a multi-faceted performance evaluation: (1) the harmonic mean of precision and recall (F1-score), (2) robustness against class imbalance (Balanced Accuracy), and (3) the ability to identify all relevant instances (Recall), (4) the capacity to maintain semantic consistency by avoiding irrelevant answers (IAR).

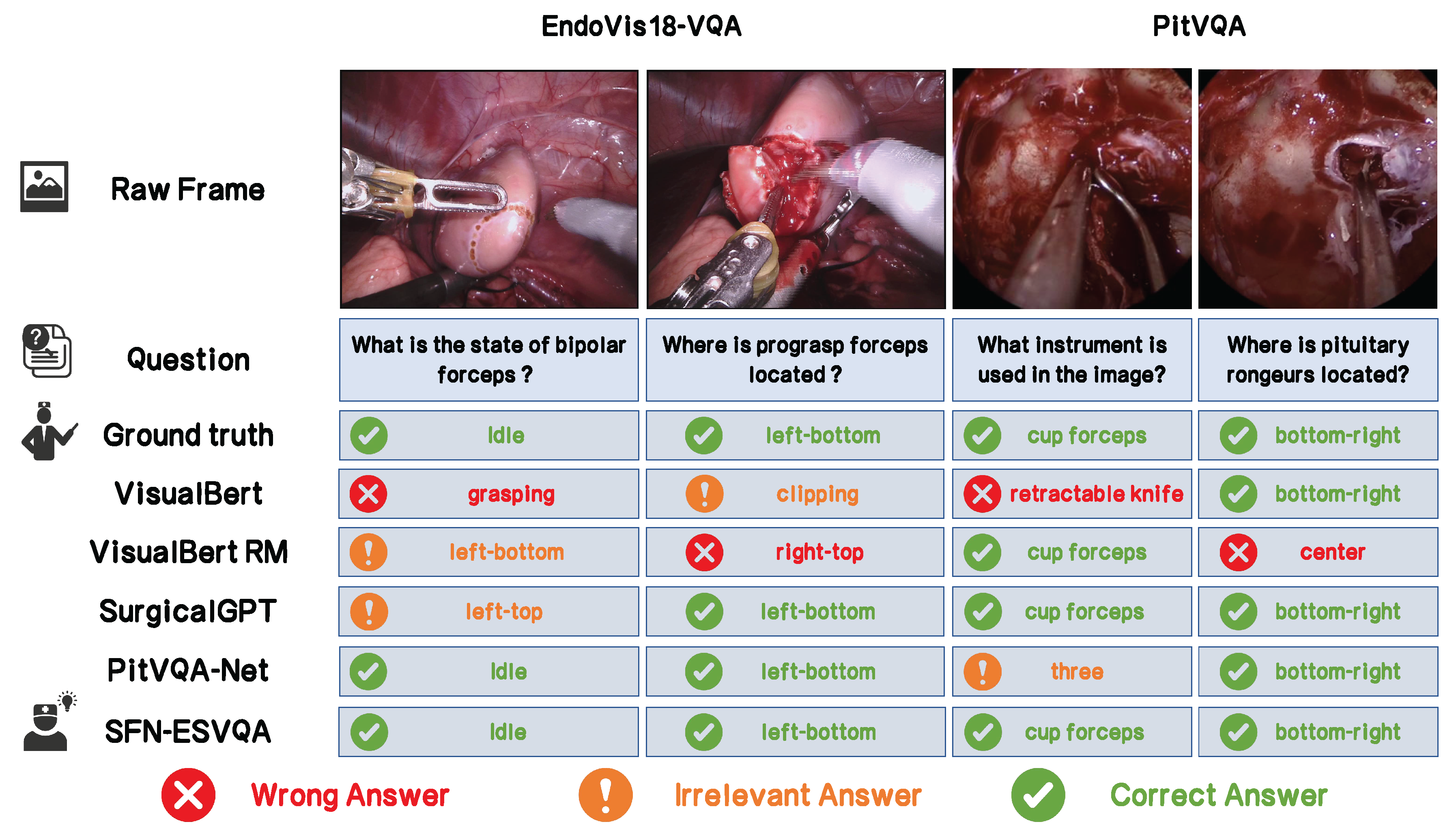

4.4. Results: SFN-ESVQA Versus SOTA Baselines

Table 1 presents the quantitative results of our proposed method compared to previous SOTA models on EndoVis18-VQA and PitVQA datasets. We particularly emphasize the metric of B. Acc to evaluate the robustness of model generation across imbalanced classes. Our method achieves a significant improvement in balanced accuracy, reaching 80.34% on EndoVis18-VQA and 86.05% on PitVQA, outperforming the previous best method PitVQA-Net by margins of 35.28% and 27.83%, respectively. In terms of F1 and Recall, our model also shows consistent superiority, showing respective improvements of 25.44% and 35.01% on EndoVis18-VQA and 29.86% and 30.64% on PitVQA.

Similar trends can be observed across all metrics, indicating that our method generalizes better and produces more accurate and stable predictions.

Table 2 further compares the Irrelevant Answer Rate (IAR) performance among these models. Our method achieves the lowest IAR values, with 1.39% on EndoVis18-VQA and 1.81% on PitVQA, reflecting its stronger ability to capture temporal features so that it could understand the whole video, avoiding to generate irrelevant answers. Compared to PitVQA-Net, our method reduces the IAR by 15.91% and 16.75% on EndoVis18-VQA and PitVQA, respectively.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, we observed that most of the related models perform better in location recognition. However, irrelevant answers still occurs across many cases to some extent, particularly regarding questions about the surgical status. Whereas, our proposed SFN-ESVQA demonstrates robust performance across various types of question answering in both datasets.

Overall, the results suggest that our SFN-ESVQA not only improves the behavior but also enhances rubustness in the VQA task for surgical scenarios.

4.5. Ablation Study

To assess the contribution of each component in our design, we perform an ablation on EndoVis18-VQA and PitVQA under the same training protocol, focusing on two factors: the frame-aware module and the IAR loss. We compare four variants:

(a) baseline without either component,

(b) adding the frame-aware module only,

(c) adding the IAR-loss only, and

(d) using both. As reported in

Table 3, introducing either component improves performance, while combining them yields the best results. These results indicate that the two components are complementary: each brings consistent gains, and together they deliver the strongest overall accuracy with the lowest IAR.

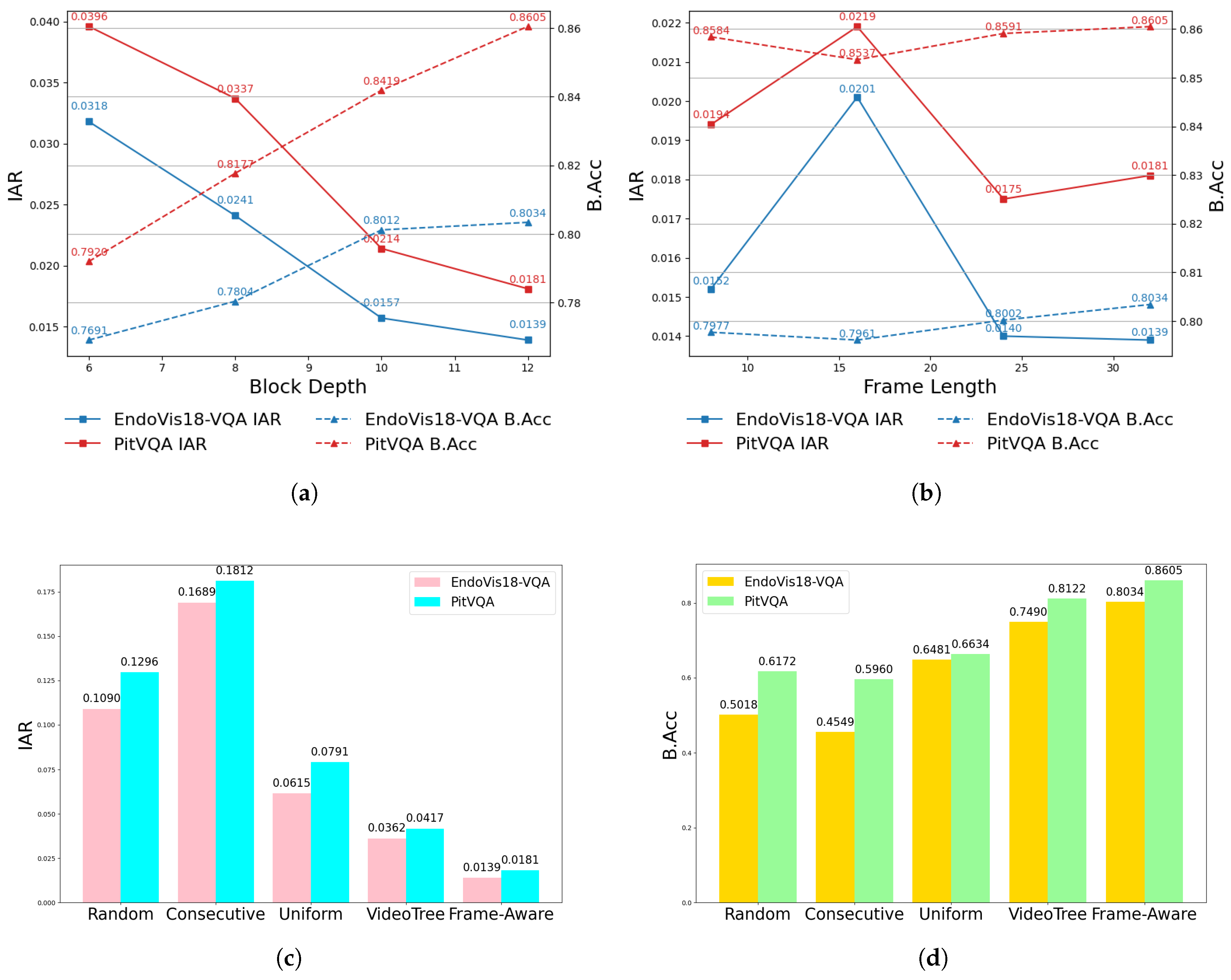

Except for the standard ablation studies, we further investigated how different hyperparameter settings of our backbone affect the behavior of the VQA process on datasets EndoVis18-VQA and PitVQA respectively, particularly focusing on IAR and B.Acc.

Block Depth:Figure 5(a) shows the influence of block depth in the Frame-Aware Attention module. We varied this hyperparameter from 6 to 12. The results indicate that both IAR and B.Acc steadily improve across both datasets, demonstrating that increasing the model capacity leads to better fusion performance. This confirms the effectiveness of a deeper backbone for SFN-ESVQA.

Frame Length:Figure 5(b) illustrates the effect of different frame lengths, which control the temporal context window between the raw frames and the input question. While performance initially improves with an increase on frame length, we observed a decline beyond 16 frames. However, considering the overall trend, the model still performs robustly, suggesting that overly long sequences may introduce redundancy or noise.

Sampling Approach:Figure 5(c) and

Figure 5(d) illustrate the results of several frame sampling strategies, including

Random (selecting arbitrary frames),

Consecutive (choosing temporally adjacent frames around raw frame),

Uniform (evenly spaced sampling from 1600 frames), and

VideoTree [

66] (hierarchical temporal coverage). In contrast, our proposed

Frame-Aware method adaptively selects key frames based on temporal consistency and proximity to the input, allowing SFN-ESVQA to better capture surgical dynamics. This leads to improved comprehension of the video context and reduces the generation of irrelevant answers.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study explores the potential postoperative review and training utility of the proposed frame-aware VQA model SFN-ESVQA. Our experimental results demonstrate a clear performance advantage for SFN-ESVQA, achieving state-of-the-art results on both the PitVQA dataset and the publicly available EndoVis18-VQA dataset when compared to existing surgical VQA models. We hope that our work will spark interest in the challenging problem of VQA in the surgical domain. Additionally, we demonstrated a major issue of the high rate of irrelevant answers in the previous models, and in our model, we have reduced Irrelevant Answer Rate to a very low level. However, the clinician oversight will still be crucial for ensuring reliable outcomes in clinical practice no matter how accurate the model is.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the VEX Robot Innovation Laboratory at Tongji University, with computational resources provided by the AI group.

References

- Y. Di, H. Shi, J. Fan, J. Bao, G. Huang, and Y. Liu, “Efficient federated recommender system based on slimify module and feature sharpening module,” Knowledge and Information Systems, pp. 1–34, 2025.

- S. Li, B. Li, B. Sun, and Y. Weng, “Towards visual-prompt temporal answer grounding in instructional video,” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, vol. 46, no. 12, pp. 8836–8853, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, Y. He, M. Tao, Y. Xia, J. Wang, T. Shi, J. Wang, and J. Yang, “Cmat: A multi-agent collaboration tuning framework for enhancing small language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.01663, 2024.

- R. He, M. Xu, A. Das, D. Z. Khan, S. Bano, H. J. Marcus, D. Stoyanov, M. J. Clarkson, and M. Islam, “Pitvqa: Image-grounded text embedding llm for visual question answering in pituitary surgery,” in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2024, pp. 488–498.

- J. Zhang, B. Li, and S. Zhou, “Hierarchical modeling for medical visual question answering with cross-attention fusion,” Applied Sciences, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 4712, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Guerrero, M. Asaad, A. Rajesh, A. Hassan, and C. E. Butler, “Advancing surgical education: the use of artificial intelligence in surgical training,” The American Surgeon, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 49–54, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Satapathy, A. H. Hermis, S. Rustagi, K. B. Pradhan, B. K. Padhi, and R. Sah, “Artificial intelligence in surgical education and training: opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations–correspondence,” International Journal of Surgery, vol. 109, no. 5, pp. 1543–1544, 2023.

- A. Das, D. Z. Khan, S. C. Williams, J. G. Hanrahan, A. Borg, N. L. Dorward, S. Bano, H. J. Marcus, and D. Stoyanov, “A multi-task network for anatomy identification in endoscopic pituitary surgery,” in International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2023, pp. 472–482.

- H. Ge, L. Hao, Z. Xu, Z. Lin, B. Li, S. Zhou, H. Zhao, and Y. Liu, “Clinkd: Cross-modal clinical knowledge distiller for multi-task medical images,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05928, 2025.

- P. V. Tomazic, F. Sommer, A. Treccosti, H. R. Briner, and A. Leunig, “3d endoscopy shows enhanced anatomical details and depth perception vs 2d: a multicentre study,” European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 278, no. 7, pp. 2321–2326, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Sturm, J. A. Windsor, P. H. Cosman, P. Cregan, P. J. Hewett, and G. J. Maddern, “A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training,” Annals of surgery, vol. 248, no. 2, pp. 166–179, 2008.

- D. W. Bates and A. A. Gawande, “Error in medicine: what have we learned?” 2000.

- C. Wang, C. Nie, and Y. Liu, “Evaluating supervised learning models for fraud detection: A comparative study of classical and deep architectures on imbalanced transaction data,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.22521, 2025.

- S. M. Kilminster and B. C. Jolly, “Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review,” Medical education, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 827–840, 2000. [CrossRef]

- L. Seenivasan, M. Islam, G. Kannan, and H. Ren, “Surgicalgpt: end-to-end language-vision gpt for visual question answering in surgery,” in International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2023, pp. 281–290.

- G. Wang, L. Bai, W. J. Nah, J. Wang, Z. Zhang, Z. Chen, J. Wu, M. Islam, H. Liu, and H. Ren, “Surgical-lvlm: Learning to adapt large vision-language model for grounded visual question answering in robotic surgery,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.10948, 2024.

- L. Seenivasan, M. Islam, A. K. Krishna, and H. Ren, “Surgical-vqa: Visual question answering in surgical scenes using transformer,” in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2022, pp. 33–43.

- M. Allan, S. Kondo, S. Bodenstedt, S. Leger, R. Kadkhodamohammadi, I. Luengo, F. Fuentes, E. Flouty, A. Mohammed, M. Pedersen et al., “2018 robotic scene segmentation challenge,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.11190, 2020.

- D. A. Hudson and C. D. Manning, “Gqa: A new dataset for real-world visual reasoning and compositional question answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 6700–6709.

- W. Hou, Y. Cheng, K. Xu, Y. Hu, W. Li, and J. Liu, “Memory-augmented multimodal llms for surgical vqa via self-contained inquiry,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10937, 2024.

- S. Antol, A. Agrawal, J. Lu, M. Mitchell, D. Batra, C. L. Zitnick, and D. Parikh, “Vqa: Visual question answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, pp. 2425–2433.

- T. M. Thai, A. T. Vo, H. K. Tieu, L. N. Bui, and T. T. Nguyen, “Uit-saviors at medvqa-gi 2023: Improving multimodal learning with image enhancement for gastrointestinal visual question answering,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.02783, 2023.

- K. Uehara and T. Harada, “K-vqg: Knowledge-aware visual question generation for common-sense acquisition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4401–4409.

- B. N. Patro, S. Kumar, V. K. Kurmi, and V. P. Namboodiri, “Multimodal differential network for visual question generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.03986, 2018.

- S. Tascon-Morales, P. Márquez-Neila, and R. Sznitman, “Localized questions in medical visual question answering,” in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2023, pp. 361–370.

- Y. Di, X. Wang, H. Shi, C. Fan, R. Zhou, R. Ma, and Y. Liu, “Personalized consumer federated recommender system using fine-grained transformation and hybrid information sharing,” IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 25, 2012.

- W. Zaremba, I. Sutskever, and O. Vinyals, “Recurrent neural network regularization,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.2329, 2014.

- S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, “Long short-term memory,” Neural computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735–1780, 1997.

- K. Cho, B. Van Merriënboer, C. Gulcehre, D. Bahdanau, F. Bougares, H. Schwenk, and Y. Bengio, “Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.1078, 2014.

- M. Malinowski, M. Rohrbach, and M. Fritz, “Ask your neurons: A neural-based approach to answering questions about images,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, pp. 1–9.

- R. Xie, L. Jiang, X. He, Y. Pan, and Y. Cai, “A weakly supervised and globally explainable learning framework for brain tumor segmentation,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, “Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding,” in Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Y. Liu, X. Qin, Y. Gao, X. Li, and C. Feng, “Setransformer: A hybrid attention-based architecture for robust human activity recognition,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.19369, 2025.

- H. Tan and M. Bansal, “Lxmert: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers,” in Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2019.

- J. Lu, D. Batra, D. Parikh, and S. Lee, “Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 32, 2019.

- X. Li, X. Yin, C. Li, X. Hu, P. Zhang, L. Zhang, L. Wang, H. Hu, L. Dong, F. Wei, Y. Choi, and J. Gao, “Oscar: Object-semantics aligned pre-training for vision-language tasks,” ECCV 2020, 2020.

- L. H. Li, M. Yatskar, D. Yin, C.-J. Hsieh, and K.-W. Chang, “Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.03557, 2019.s.

- D. N. Kamtam, J. B. Shrager, S. D. Malla, N. Lin, J. J. Cardona, J. J. Kim, and C. Hu, “Deep learning approaches to surgical video segmentation and object detection: A scoping review,” Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 194, p. 110482, 2025.

- S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun, “Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks,” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1137–1149, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Sharma, S. Purushotham, and C. K. Reddy, “Medfusenet: An attention-based multimodal deep learning model for visual question answering in the medical domain,” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 19826, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Khare, V. Bagal, M. Mathew, A. Devi, U. D. Priyakumar, and C. Jawahar, “Mmbert: Multimodal bert pretraining for improved medical vqa,” in 2021 IEEE 18th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1033–1036.

- L. Li, S. Lu, Y. Ren, and A. W.-K. Kong, “Set you straight: Auto-steering denoising trajectories to sidestep unwanted concepts,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.12782, 2025.

- L. Bai, M. Islam, L. Seenivasan, and H. Ren, “Surgical-vqla: Transformer with gated vision-language embedding for visual question localized-answering in robotic surgery,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 6859–6865.

- L. Bai, M. Islam, and H. Ren, “Cat-vil: Co-attention gated vision-language embedding for visual question localized-answering in robotic surgery,” in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2023, pp. 397–407.

- P. Wang, S. Bai, S. Tan, S. Wang, Z. Fan, J. Bai, K. Chen, X. Liu, J. Wang, W. Ge et al., “Qwen2-vl: Enhancing vision-language model’s perception of the world at any resolution,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12191, 2024.

- C. Loukas, “Video content analysis of surgical procedures,” Surgical endoscopy, vol. 32, pp. 553–568, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Wu, X. Qiu, S. Song, Z. Chen, X. Huang, F. Ma, and J. Xiao, “Image augmentation agent for weakly supervised semantic segmentation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.20439, 2024.

- M. Kawka, T. M. Gall, C. Fang, R. Liu, and L. R. Jiao, “Intraoperative video analysis and machine learning models will change the future of surgical training,” Intelligent Surgery, vol. 1, pp. 13–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Zisimopoulos, E. Flouty, I. Luengo, P. Giataganas, J. Nehme, A. Chow, and D. Stoyanov, “Deepphase: surgical phase recognition in cataracts videos,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018: 21st International Conference, Granada, Spain, September 16-20, 2018, Proceedings, Part IV 11. Springer, 2018, pp. 265–272.

- I. Oropesa, P. Sánchez-González, M. K. Chmarra, P. Lamata, A. Fernández, J. A. Sánchez-Margallo, F. W. Jansen, J. Dankelman, F. M. Sánchez-Margallo, and E. J. Gómez, “Eva: laparoscopic instrument tracking based on endoscopic video analysis for psychomotor skills assessment,” Surgical endoscopy, vol. 27, pp. 1029–1039, 2013. [CrossRef]

- I. Funke, S. T. Mees, J. Weitz, and S. Speidel, “Video-based surgical skill assessment using 3d convolutional neural networks,” International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery, vol. 14, pp. 1217–1225, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Mascagni, D. Alapatt, T. Urade, A. Vardazaryan, D. Mutter, J. Marescaux, G. Costamagna, B. Dallemagne, and N. Padoy, “A computer vision platform to automatically locate critical events in surgical videos: documenting safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy,” Annals of surgery, vol. 274, no. 1, pp. e93–e95, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Hung, R. Bao, I. O. Sunmola, D.-A. Huang, J. H. Nguyen, and A. Anandkumar, “Capturing fine-grained details for video-based automation of suturing skills assessment,” International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 545–552, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhong, J. Xiao, W. Ji, Y. Li, W. Deng, and T.-S. Chua, “Video question answering: Datasets, algorithms and challenges,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.01225, 2022.

- K.-H. Zeng, T.-H. Chen, C.-Y. Chuang, Y.-H. Liao, J. C. Niebles, and M. Sun, “Leveraging video descriptions to learn video question answering,” in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 31, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Gao, S. Lu, W. Zhou, J. Chu, J. Zhang, M. Jia, B. Zhang, Z. Fan, and W. Zhang, “Eraseanything: Enabling concept erasure in rectified flow transformers,” in Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, 2025.

- J. Gao, R. Ge, K. Chen, and R. Nevatia, “Motion-appearance co-memory networks for video question answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 6576–6585.

- J. Xu, T. Mei, T. Yao, and Y. Rui, “Msr-vtt: A large video description dataset for bridging video and language,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 5288–5296.

- M. Tapaswi, Y. Zhu, R. Stiefelhagen, A. Torralba, R. Urtasun, and S. Fidler, “Movieqa: Understanding stories in movies through question-answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 4631–4640.

- X. Li, J. Song, L. Gao, X. Liu, W. Huang, X. He, and C. Gan, “Beyond rnns: Positional self-attention with co-attention for video question answering,” in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 33, no. 01, 2019, pp. 8658–8665.

- J. Lei, L. Li, L. Zhou, Z. Gan, T. L. Berg, M. Bansal, and J. Liu, “Less is more: Clipbert for video-and-language learning via sparse sampling,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 7331–7341.

- H. Ben-Younes, R. Cadene, M. Cord, and N. Thome, “Mutan: Multimodal tucker fusion for visual question answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2612–2620.

- Z. Yu, J. Yu, J. Fan, and D. Tao, “Multi-modal factorized bilinear pooling with co-attention learning for visual question answering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 1821–1830.

- Z. Yu, J. Yu, C. Xiang, J. Fan, and D. Tao, “Beyond bilinear: Generalized multimodal factorized high-order pooling for visual question answering,” IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 5947–5959, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, S. Yu, E. Stengel-Eskin, J. Yoon, F. Cheng, G. Bertasius, and M. Bansal, “Videotree: Adaptive tree-based video representation for llm reasoning on long videos,” in Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 2025, pp. 3272–3283.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).