Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

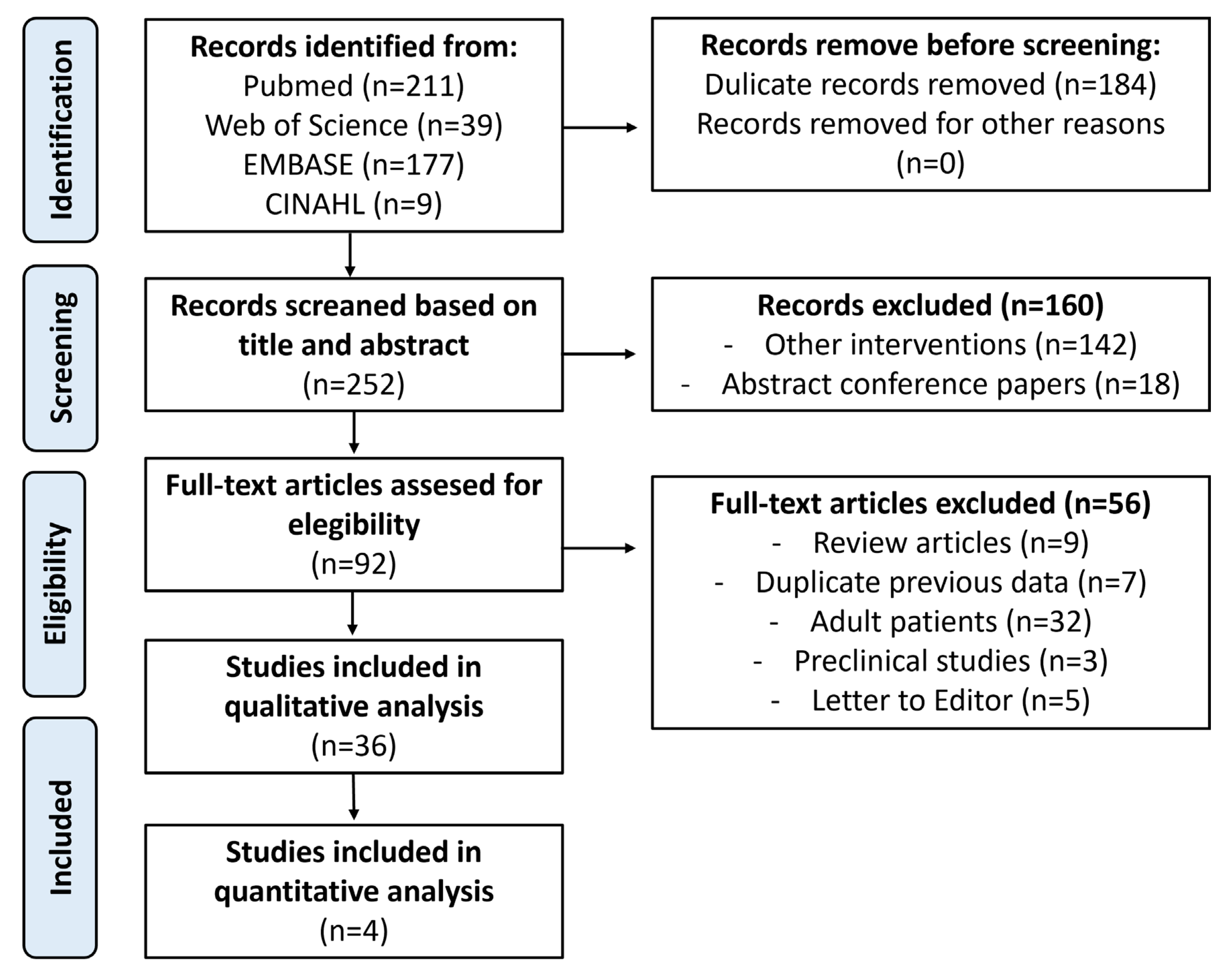

Methods

Search Strategy

Eligibility Criteria

Data Collection

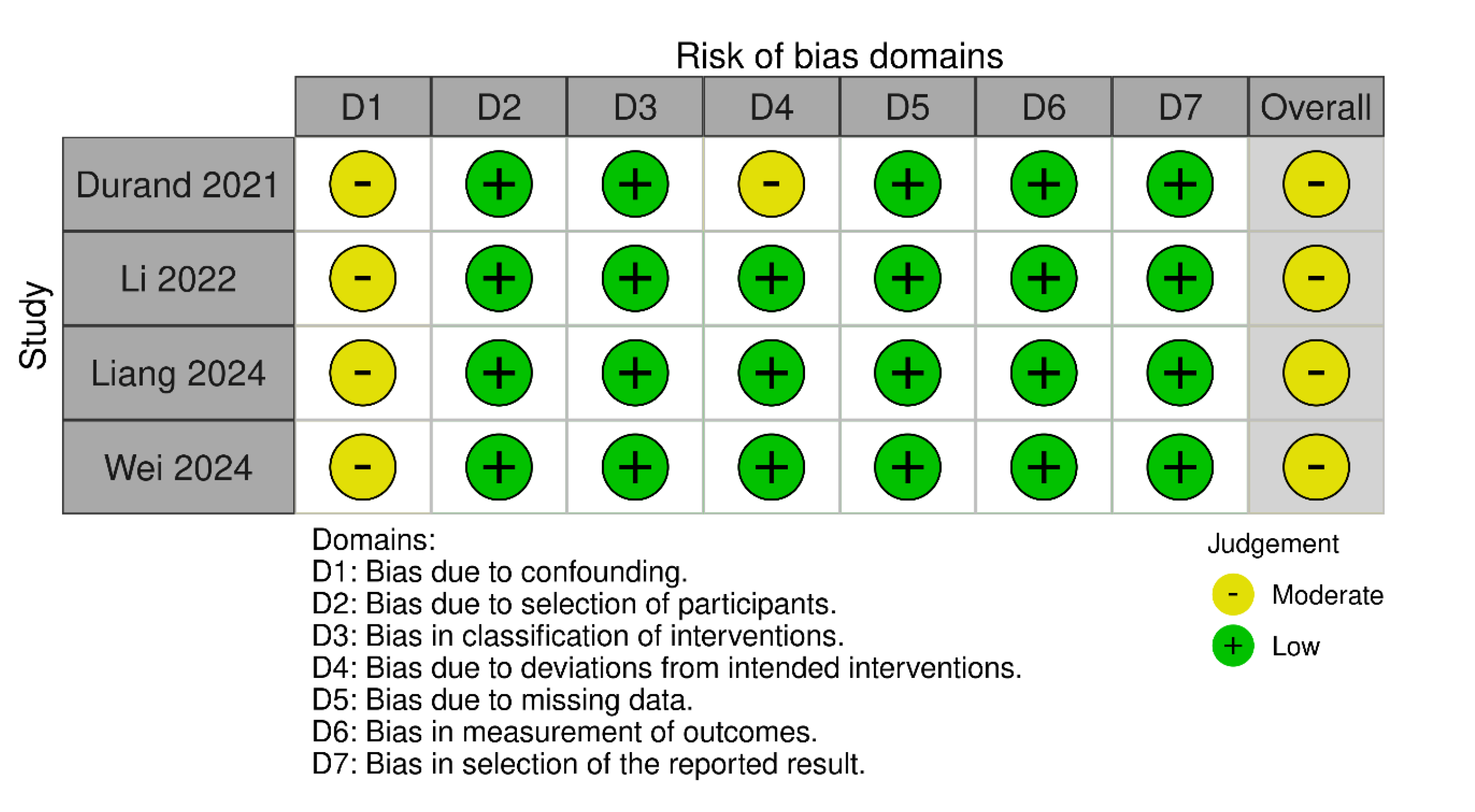

Quality Appraisal and Risk of Bias

Data Synthesis

Data Analysis

GRADE Certainty of Evidence

Results

Qualitative Analysis

Tracheomalacia

Pulmonary Diseases

Congenital Diaphragmatic Defects

Thymic Disorders

Mediastinal Tumors

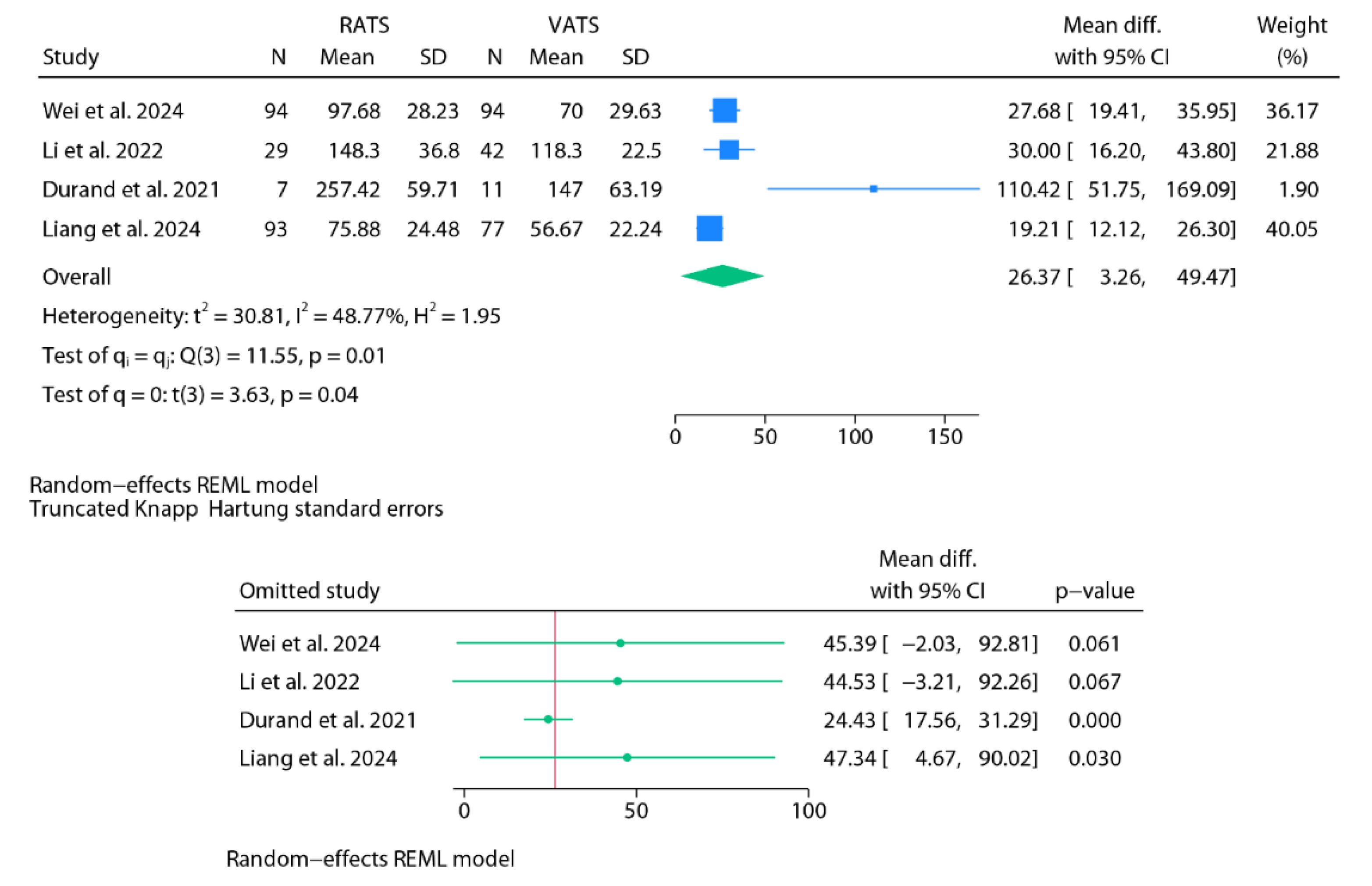

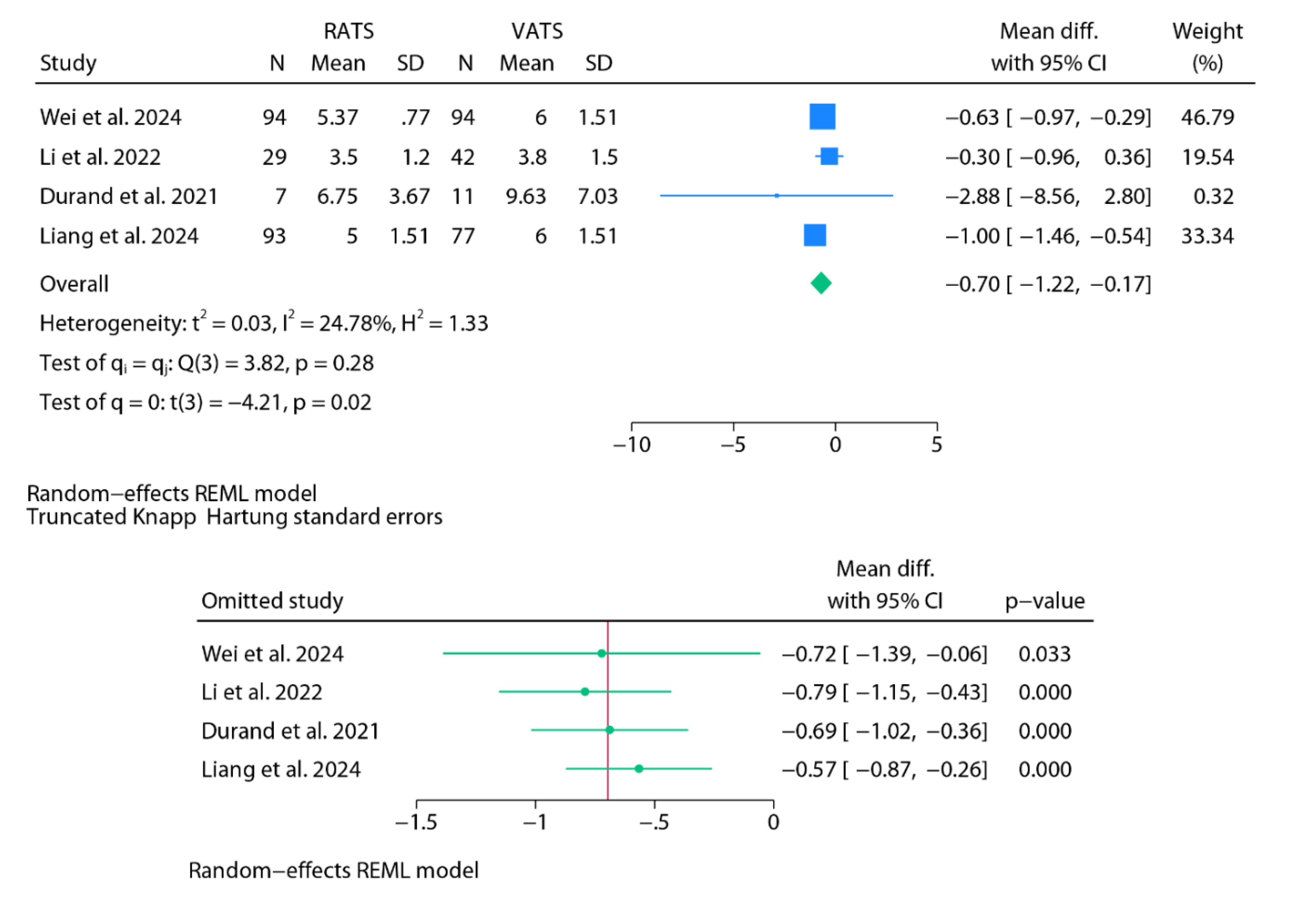

Quantitative Analysis

Operative Time

Length of Hospital Stay

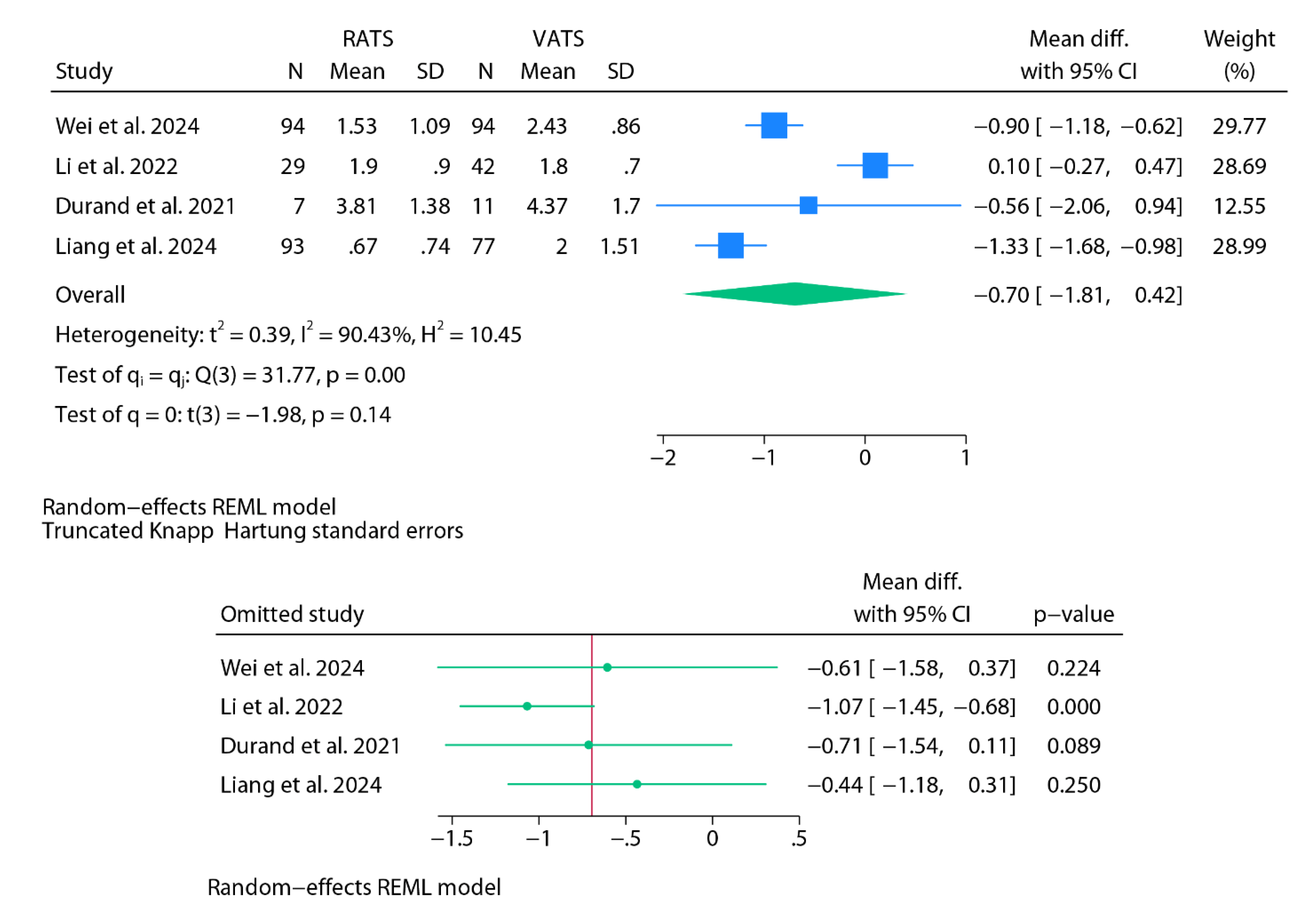

Chest Tube Duration

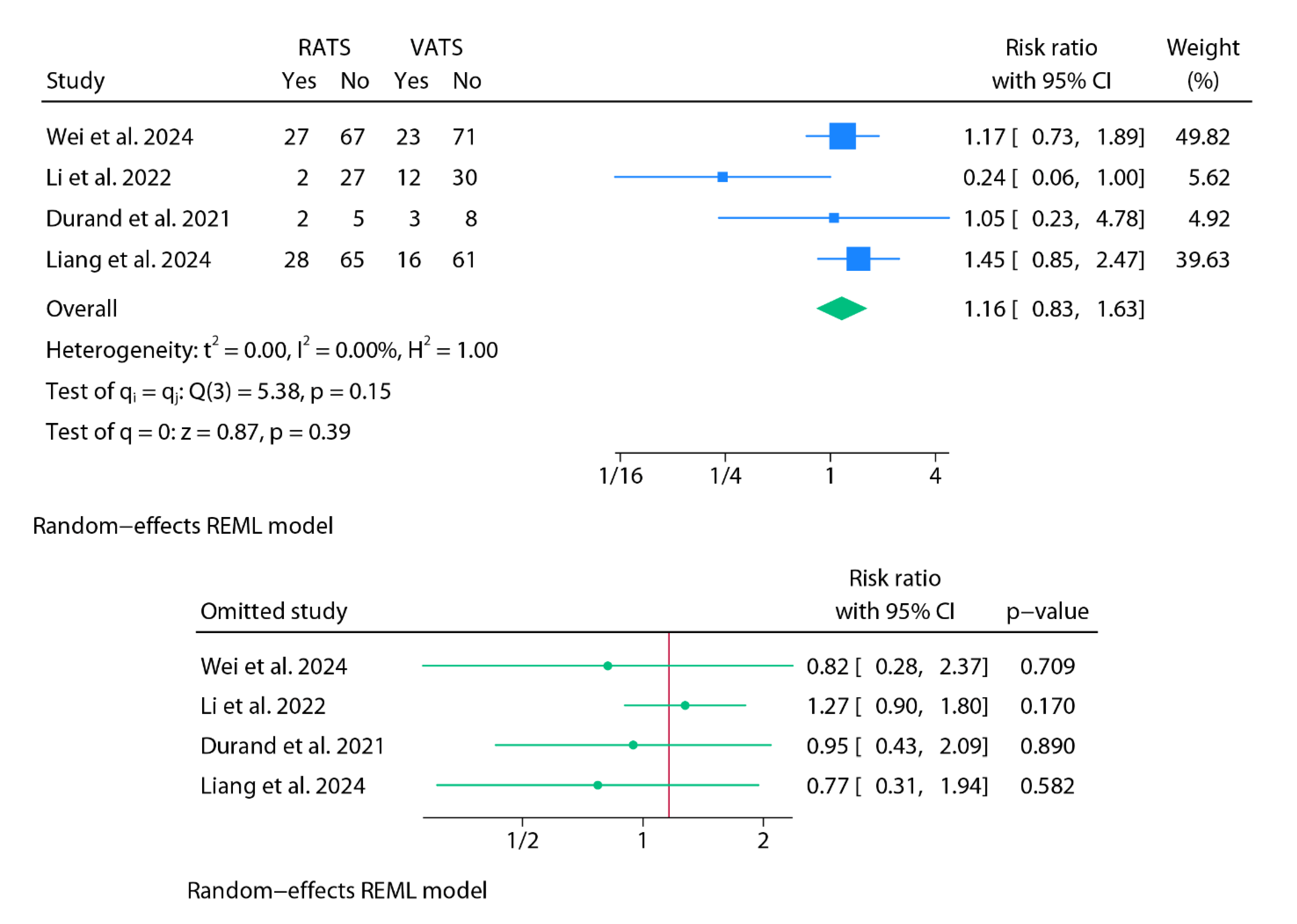

Conversion to Open Surgery

Postoperative Complications

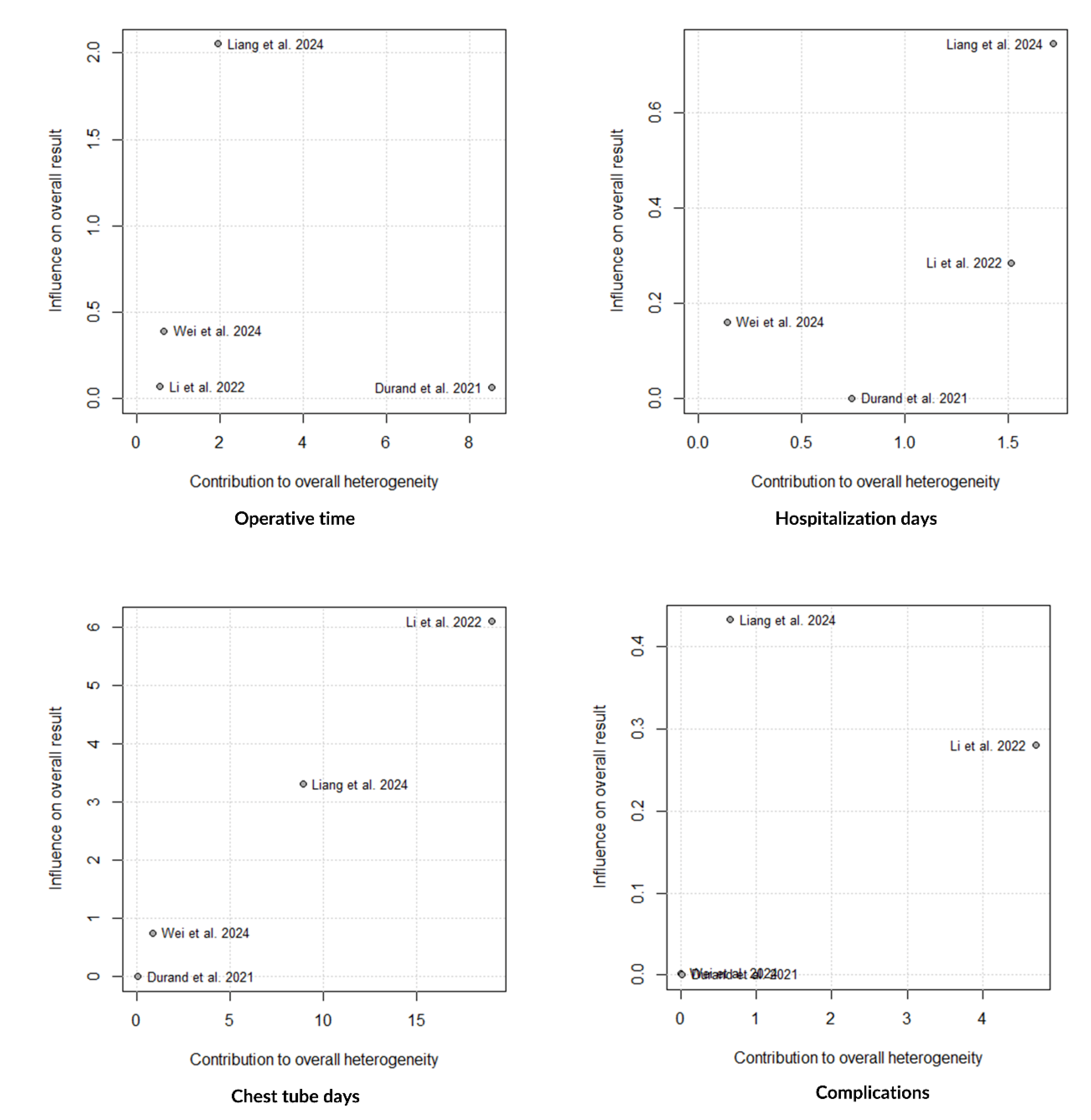

Findings from Baujat Plots

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

GRADE Certainty of Evidence

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Registration and Protocol

References

- Melfi FM, Menconi GF, Mariani AM, Angeletti CA. Early experience with robotic technology for thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002, 21, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz G, Sancheti M, Blasberg J. Robotic Thoracic Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2020, 100, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbe B, Woo R, Wolf S, Irish M. Robotically assisted minimally invasive surgery in a pediatric population: initial experience, technical considerations, and description of the da Vinci Surgical System. Pediatr Endosurg Innov Tech. 2003, 7, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, JJ. Robotic surgery in small children: is there room for this? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009, 19, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Arellano, M. Thoracic surgery by minimally invasive robot-assisted in children: experience and current status. Mini-invasive Surg. 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ballouhey Q, Villemagne T, Cros J, Vacquerie V, Bérenguer D, Braik K, Szwarc C, Longis B, Lardy H, Fourcade L. Assessment of paediatric thoracic robotic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015, 20, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang L, Tan Z, Huang T, Gao Y, Zhang J, Yu J, Xia J, Shu Q. Efficacy of robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in the treatment of pulmonary sequestration in children. World J Pediatr Surg. 2024, 7, e000748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei S, Huang T, Liang L, Gao Y, Zhang J, Xia J, Yu L, Shu Q, Tan Z. Efficacy of Da Vinci Robot-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery in Children With Congenital Cystic Adenomatiod Malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2024, 59, 1458–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li S, Luo Z, Li K, Li Y, Yang D, Cao G, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Chi S, Tang S. Robotic approach for pediatric pulmonary resection: preliminary investigation and comparative study with thoracoscopic approach. J Thorac Dis. 2022, 14, 3854–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand M, Musleh L, Vatta F, Orofino G, Querciagrossa S, Jugie M, Bustarret O, Delacourt C, Sarnacki S, Blanc T, Khen-Dunlop N. Robotic lobectomy in children with severe bronchiectasis: A worthwhile new technology. J Pediatr Surg. 2021, 56, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar]

- Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi J, Luo D, Wan X, Liu Y, Liu J, Bian Z, Tong T. Detecting the skewness of data from the sample size and the five-number summary. Stat Methods Med Res. 2023, 32, 1338–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath S, Zhao X, Steele R, Thombs BD, Benedetti A; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from commonly reported quantiles in meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2020, 29, 2520–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024). Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.cochrane.org/handbook (access on: 01/08/2025).

- Newcombe RG, Bender R. Implementing GRADE: calculating the risk difference from the baseline risk and the relative risk. Evid Based Med. 2014, 19, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran A, Hamilton TE, Zendejas B, Nath B, Jennings RW, Smithers CJ. Minimally Invasive Surgical Approach for Posterior Tracheopexy to Treat Severe Tracheomalacia: Lessons Learned from Initial Case Series. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018, 28, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre M, Guerriero V, Moscatelli A, Disma N, Lena F, Palo F, et al. Posterior tracheobronchopexy with thoracoscopic or robotic approach: technical details. J Pediatr Endosc Surg. 2020, 2, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan JJ, Phearman L, Sandler A. Robotic pulmonary resections in children: series report and introduction of a new robotic instrument. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008, 18, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao Y, Han X, Jin J, Tan Z. Ten cases of intradiaphragmatic extralobar pulmonary sequestration: a single-center experience. World Jnl Ped Surgery 2022, 5, e000334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones RE, Freedman-Weiss M, Ha J, Paranjape S, Garcia AV. Robotic ligation of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation in a teenaged child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2024, 101, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Beauregard C, Rodríguez de Alarcón García J, Domínguez Amillo EE, Gómez Cervantes M, Ávila Ramírez LF. Implementing a pediatric robotic surgery program: future perspectives. Cir Pediatr. 2022, 35, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Çeltik Ü, Şahutoğlu C, Dökümcü Z, Özcan C, Erdener A. Examining the potential of advanced robotic-assisted thoracic surgery in pediatric cases. J Pediatr Res. 2024, 11, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Knight CG, Gidell KM, Lanning D, Lorincz A, Langenburg SE, Klein MD. Laparoscopic Morgagni hernia repair in children using robotic instruments. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005, 15, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderberg M, Kockum CC, Arnbjornsson E. Morgagni hernia repair in a small child using da Vinci robotic instruments--a case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009, 19, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater BJ, Meehan JJ. Robotic repair of congenital diaphragmatic anomalies J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009, 19 Suppl 1:S123-7.

- Delgado-Miguel C, Camps JI. Robotic surgery in newborns and infants under 12-months: Is it feasible? Asian J Surg. 2025 August 13 Online ahead of publish. [CrossRef]

- Xu PP, Chang XP, Tang ST, Li S, Cao GQ, Zhang X, et al. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic plication for diaphragmatic eventration. J Pediatr Surg. 2020, 55, 2787–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani K, Heng L, Khen-Dunlop N, Panait N, Hervieux E, Grynberg L, et al. Comparative Outcomes of Surgical Techniques for Congenital Diaphragmatic Eventration in Children: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2025 Mar 18. Epub ahead of print.

- Hartwich J, Tyagi S, Margaron F, Oitcica C, Teasley J, Lanning D. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy for treating myasthenia gravis in children. J Laparoend Adv Surg Tech 2012, 22, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso F, De Leonibus L, Bertozzi M, Sica M, Angotti R, Luzzi L, Molinaro F, Messina M, Paladini P. Robotic-assisted thoracoscopy thymectomy for juvenile myasthenia gravis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020, 62, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke R, Emr B, Taylor M, Fahy AS. Robotic resection of a giant thymolipoma in a pediatric patient. J Surg Case Rep. 2024, 2024, rjae691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Li F, Zhang H, Swierzy M, Ismail M, Meisel A, Rueckert JC. Outcomes of Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis: A Comparison of Robotic Thymectomy With Medication Treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022, 113, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan JJ, Sandler AD. Robotic resection of mediastinal masses in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008, 18, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc T, Meignan P, Vinit N, Ballouhey Q, Pio L, Capito C, et al. Robotic Surgery in Pediatric Oncology: Lessons Learned from the First 100 Tumors-A Nationwide Experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng Q, Chen C, Zhang N, Yu J, Yan D, Xu C, Liu D, Zhang Q, Zhang X. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for mediastinal tumours in children: a single-centre retrospective study of 149 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023, 64, ezad362.

- Svetanoff WJ, Carter M, Diefenbach KA, Michalsky M, DaJusta D, Gong E, Lautz TB, Aldrink JH. Robotic-assisted Pediatric Thoracic and Abdominal Tumor Resection: An Initial Multi-center Review. J Pediatr Surg. 2024, 59, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toker A, Ayalp K, Grusina-Ujumaza J, Kaba E. Resection of a bronchogenic cyst in the first decade of life with robotic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014, 19, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto Y, Kuroda K, Mori M, et al. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic resection of a posterior mediastinal tumor with preserving the artery of Adamkiewicz. Surg Case Rep.

- Yamaguchi Y, Moharir A, Burrier C, Tobias JD. Point-of-care lung ultrasound to evaluate lung isolation during one-lung ventilation in children: A case report. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019, 13, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi T, Koga H, Ueno H, Fujimura J, Kosaka S, Miyake Y, Yoshida S, Lane GJ, Suzuki K, Yamataka A. Successful all robotic-assisted excision of highly malignant mediastinal neuroblastoma in a toddler: A case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2023, 16, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccipetitoni G, Bertozzi M, Gazzaneo M, Raffaele A, Vatta F. The role of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in pediatric oncology: single-center experience and review of the literature. Front Pediatr. 2021, 9, 721914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad A, Jain P, Narang R. Robotic assisted thoracoscopic surgery (RATS) for excision of posterior mediastinal mass. J Pediatr Endosc Surg. 2023, 5, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadır GB, Çalışkan MB, Ünlü Ballı SE, Atasever HE, Korkmaz G, Yıldırım İ, et al. Robotic Assisted Endoscopic Surgery Practices in Pediatric Surgery, Single Center Experience. Turkish J Pediatr Dis. 2023, 17, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda S, Kawaguchi K, Ito A, Ito D, Kawaguchi T, Shimamoto A, Takao M. Subcostal approach using the single-port robotic system for a giant ganglioneuroma in a child. JTCVS Techniques. 2025, 32, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal S, Sinha A, Pathak M. Robotic assisted thoracoscopic surgery in children: a narrated review. J Pediatr Endosc Surg. 2024, 6, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena AK, Borgogni R, Escolino M, D’Auria D, Esposito C. Narrative review: robotic pediatric surgery-current status and future perspectives. Transl Pediatr 2023, 12, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M. Editorial: Pediatric thoracic surgery. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1132803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arca MJ, Barnhart DC, Lelli JL Jr, Greenfeld J, Harmon CM, Hirschl RB, Teitelbaum DH. Early experience with minimally invasive repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias: results and lessons learned. J Pediatr Surg. 2003, 38, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li XF, Jin L, Yang JM, Luo QS, Liu HM, Yu H. Effect of ventilation mode on postoperative pulmonary complications following lung resection surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2022, 77, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li XK, Cong ZZ, Xu Y, Zhou H, Wu WJ, Wang GM et al. Clinical efficacy of robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for posterior mediastinal neurogenic tumors. J Thorac Dis 2020, 12, 3065–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga JC, Rothenberg S, Kiely E, Pierro A. Video-assisted thoracic surgery resection for pediatric mediastinal neurogenic tumors. J Pediatr Surg 2012, 47, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckert JC, Swierzy M, Ismail M. Comparison of robotic and nonrobotic thorascopic thymectomy: A cohort study. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg 2011, 141, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fievet L, D’Journo XB, Guys JM, Thomas PA, De Lagausie P. Bronchogenic cyst: best time for surgery? Ann Thorac Surg 2012, 94, 1695–1699.

- Molinaro F, Angotti R, Bindi E, et al. Low weight child: can it be considered a limit of robotic surgery? Experience of two centers. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 2019, 29, 698e702. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond SL, Sacks MA, Hashmi A, Robertson JO, Moores D, Tagge EP, et al. Short-term outcomes of thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy for congenital lung malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2023, 39, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha SK, Haddad M. Robot-assisted surgery in children: current status. J Robotic Surg. 2008, 1, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmaldin A, Antao B. Early experience of tele-robotic sugery in children. Int J Med Robot Comp Assist Surg. 2007, 3, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References (country, year) | Procedure No. cases |

Study design | Age (range) | Robot model Ports |

Operating time (minutes) | Postoperative complications | Conversion to open | Chest tube (days) | Hospital stay (days) | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamran et al. (USA, 2018) [21] | PT 6 RATS 4 VATS |

Retrospective descriptive | 11 yr (5- 19) | NS | 6.5 h (4.5-10.5) | None | None | NO | 3-7 | 6 mo (1-16) |

| Torre et al (Italia, 2020) [22] | PT 2 RATS 4 VATS |

Retrospective descriptive | 58 mo (8-162) | Xi 4 RB 8-mm |

150 (110-320) | None | None | YES NS |

5 (3-118) | NS |

| Meehan et al. (USA, 2008) [23] | Total: 6 2 CPAMs, 2 IS, 1 bronchiectasis, 1 chronic granulomatous disease |

Retrospective descriptive | 7 mo-14 yr | S 5-mm and 12-mm (camera) |

NS | None | 1 (LB) | 4 cases (1-3 days) |

1.8 (1-3) | 24 mo (2 mo-4 yr) |

| Gao et al. (China, 2022) [24] | 9 IEPS 4 RATS 5 VATS |

Retrospective descriptive | 9.5 mo | Xi 3 RP 8-mm |

RATS 80; VATS 48 | None | None | RATS 1.5 days; VATS 2.2 days | RATS 4.3; VATS 6.4 | NS |

| Jones et al. (USA, 2024) [25] | PAVM 1 |

Case report | 16 yr | Xi 4 RB 8-mm |

90 | None | None | YES 1 day |

2 | 4 mo |

| Ballouhey et al. (France, 2015) [6] | Total: 11 4 BC 2 CDH, 5 Esophageal procedures |

Retrospective descriptive | 72 mo (0-204) | Xi NS |

190 (120-310) | 1 dysphagia (BC) | 1 (CDH) | NS | 6.2 (3–20) | 26.9 mo (8-55) |

| Navarrete-Arellano (Mexico, 2020) [5] | Total: 11 3 CPAMs, 1 IS, 3 DE, 1 DP, 1 teratoma, 1 Ewing tumor, 1 pulmonary TBC |

Retrospective descriptive | 5.7 years (6 mo- 15 yr) | Si 3-4 RB 5-mm |

166.45 (25-314) | 1 serous prolonged drainage (DP) | 1 (IS) | NS | 3.6 (1-12) | NS |

| Soto et al. (Spain, 2022) [26] | Total: 3 2 pneumothorax, 1 ES |

Retrospective descriptive | 2.5-17 yr | Xi 3 RB 8-mm |

100 (81-108) | None | None | NO | 2 | NS |

| Çeltik et al. (Turkey, 2024) [27] | Total: 30 10 NT, 3 pulmonary metastasis, 2 BC, 1 Ewing tumor, 1 teratoma, 1 M-CDH, 1 CPAM, 1 hydatid cyst, 1 APVR, 1 bronchiectasis, 8 esophageal pathologies |

Retrospective descriptive | 8.4 yr (SD: 5.2) (1-17 yr) | NS | 165.6 (SD: 124.8) | 4: Horner syndrome, atelectasis, pleural effusion, prolonged air leakage | None | 20 cases 3 days (1-25) |

3.5 (1-30) | NS |

| Luebbe et al. (USA, 2003) [3] | M-CDH and mediastinal mass 2 |

Case series | 10 yr | S 8-mm RB + 12-mm camera |

NS | 1 pneumothorax | None | NO | NS | NS |

| Knight et al. (USA, 2005) [28] | M-CDH 2 |

Case series | 23 mo and 5 yr | Zeus 4 RB 5-mm |

227 | None | None | NO | 1-2 | NS |

| Anderberg et al. (Sweden, 2008) [29] | M-CDH 1 |

Case report | 18 mo | S 8-mm ports + 12-mm camera |

145 | None | None | NO | 3 | 1 yr |

| Slater et al. (USA, 2009) [30] | Total: 8 2 DE, 5 B-CDH, 1 M-CDH |

Retrospective descriptive | 3.9 mo (4 days-12 mo) | S 3 RB 5-mm |

80 | 1 recurrence (B-CDH) | 2 | NO | NS | NS |

| Delgado-Miguel et al. (USA, 2025) [31] | Total: 3 CDH 2 B-CDH 1 M-CDH |

Retrospective descriptive | 8 mo (7-10) |

Si 3-4 RP (12-mm camera + 2-3x5-mm) |

153 (IQR: 123-237) | None | None | NO | 3 (2-4) | 6.5 yr (IQR 3.8-9.4) |

| Xu et al (China, 2020) [32] | Total: 20 DE RATS: 9 VATS: 11 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 11.2 mo (SD: 2.1) VATS: 9.4 mo (SD: 2.3) |

Si 3 RP (12-mm camera + 2x8-mm) |

RATS; 103.6 (SD: 14.8) VATS: 102.4 (SD: 14.5) |

RATS: none VATS: 1 recurrence |

None | NO | RATS: 7.8 (SD: 0.6) VATS: 8.1 (SD: 0.9) |

NS |

| Alzahrani et al (France, 2025) [33] | Total: 112 DE RATS: 5 VATS: 64 Thoracotomy: 15 Abdominal: 28 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 29 mo (11.5-76.5) VATS: 13 mo (6–23.3) |

NS | NS | 3 RATS: 2 liver injuries, 1 recurrence 11 VATS: 4 pleural injuries. 1 tracheal tube dislodgement, 6 recurrences |

None | NO | RATS: 5 (4.3-6.5) VATS: 4 (3-5) |

RATS: 56 mo (10.5-65.0) VATS: 28.8 mo (11.3-52.8) |

| References (country, year) | Procedure No. cases |

Study design | Age (range) | Robot model Ports |

Operating time (minutes) | Postoperative complications | Conversion to open | Chest tube (days) | Hospital stay (days) | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartwich et al. (USA, 2012) [34] | Thymectomy 9 |

Retrospective descriptive | 9.4 yr (SD: 4.8) | S 3 RB: 8.5-mm camera + 2x5 mm |

160 (SD: 6) | 1 pneumothorax | None | 1 case | 1 (1-2) | 22 mo |

| Grasso et al. (Italy, 2020) [35] | Thymectomy 1 |

Case report | 12 yr | Xi 3 RB 8-mm |

90 | None | None | YES 2 days |

4 | 2 mo |

| Hanke et al. (USA, 2024) [36] | Giant thymolipoma 1 |

Case report | 10 yr | Xi 3 RB 8-mm + 2 AP (12-mm + 5-mm) |

NS | None | None | NO | 3 | 2 yr |

| Li et al. (Germany, 2022) [37] | Thymectomy 47 RATS 20 medical |

Retrospective descriptive | 13 yr (10-15) | Xi 3 RB 8-mm |

NS | 9 cases: 5 myasthenic symptoms, 2 pneumothorax, 2 chylothorax | None | NO | 4 (3-31) | 46 mo (30-94) |

| Meehan et al. (USA, 2008) [38] | Total: 5 1 GNB, 1 GN, 1 teratoma, 1 inflammatory mass, 1 germ cell tumor |

Retrospective descriptive | 9.8 yr (2-17) | S 3-4 RP 5-mm |

113 (44-156) | None | None | NS | NS | 26 mo (19-30) |

| Blanc et al. (France, 2022) [39] | Total: 14 4 NB, 3 GNB; 3 GN, 3 thymoma, 1 bronchial carcinoid |

Retrospective descriptive | NS | Xi NS |

NS | 2 pneumothorax | 1 (NB) | No | 3 (2–4) | 2.4 yr (1.5-3.4) |

| Zeng et al. (China, 2023) [40] | Total: 149 99 NT, 19 foregut cysts, 12 thymic tumors, 9 angiolymphatic tumours, 6 lipogenic tumors, 4 soft tissue tumours |

Retrospective descriptive | 5.9 yr (6 mo-16 yr) | Xi 4 RB 8-mm |

106.7 (25-260) | None | 4 | YES 2-3 days |

7.2 (4-14) | 3-23 mo |

| Svetanoff et al. (USA, 2024) [41] | Total: 17 8 GNB, 6 GN, 2 NB, 1 PG |

Retrospective descriptive | 6.1 yr (IQR 4.8-8.8) | Si and Xi 4 RB 8-mm |

124 (IQR:108-173) | 1 chyle leak | 2 | NS | 1.5 (IQR 1.1-3) | 13 mo (IQR 5.5-27.8) |

| Toker et al. (Turkey, 2014) [42] | BC 1 |

Case report | 8 yr | Si 3 RP 5-mm |

62 | None | None | YES 1 day |

2 | 6 mo |

| Nemoto et al. (Japan, 2022) [43] | GN 1 |

Case report | 15 yr | Xi 4 RP 8-mm |

NS | None | None | NO | NS | 18 mo |

| Yamaguchi et al. (USA, 2019) [44] | Paraspinal mass 1 |

Case report | 7 yr | Xi NS |

104 | None | None | NO | 1 | NS |

| Ochi et al. (Japan, 2023) [45] | NB 1 |

Case report | 28 mo | Xi 4 RB: 3x8-mm + 12-mm camera |

NS | None | None | YES 2 days |

NS | 7 mo |

| Riccipetitoni et al. (Italy, 2021) [46] | GNB 1 |

Case report | 7.6 yr | Xi 3 RB 2x8-mm + 12-mm camera |

290 | None | None | NO | 7 | 0.78 yr |

| Prasad et al. (India, 2023) [47] | GN 1 |

Case report | 9 yr | Xi 3 RB 8-mm + 1 AP 5-mm |

130 | None | None | YES 1 day |

2 | 1 yr |

| Bahadır et al (Turkey, 2023) [48] | PG 1 |

Case report | 11 yr | Si 3 RB (2x8-mm + 12-mm camera) + 1 AP 10-mm |

180 | None | None | NO | 4 | 44 mo |

| Kaneda et al (Japan, 2025) [49] | GN 1 |

Case report | 8 yr | SP | 250 | None | None | NO | 3 | 1 mo |

| References (country, year) | Procedure No. cases |

Study design | Age (range) | Robot model Ports |

Operating time (minutes) | Postoperative complications | Conversion to open | Chest tube (days) | Hospital stay (days) | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durand et al (France, 2021) [20] | RATS: 7 VATS: 11 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 13.1 yr (9.65-13.5) VATS: 10.1 yr (6.8-13.2) |

Xi 3 RP 8-mm + AP 5-mm |

RATS: 268 (221.5-286.5) VATS: 131 (115.5-190) |

RATS: 2 VATS: 3 |

RATS: 0 VATS: 5 |

RATS: 4 (3-4.5) VATS: 4 (3.5-5.5) |

RATS: 6 (5-9) VATS: |

NS |

| Li et al (China, 2022) [21] | RATS: 29 VATS: 42 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 68.1±47.2 mo VATS: 64.6±45.1 mo |

Si 3·RP (12-mm camera + 2x8-mm) + AP 5-mm |

RATS: 148.3±36.8 VATS: 118.3±22.5 |

RATS: 2 VATS: 12 |

RATS: 1 VATS: 2 |

RATS: 1.9±0.9 VATS: 1.8±0.7 |

RATS: 3.5±1.2 VATS: 3.8±1.5 |

6-54 mo |

| Liang et al (China, 2024) [22] | RATS: 93 VATS: 77 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 10 mo (7- 25) VATS: 9.5 mo (7- 17.5) |

Xi 3·RP 8-mm + AP 5-mm |

RATS: 75 (60-92.5) VATS: 60 (40-70) |

RATS: 28 VATS: 16 |

RATS: 1 VATS: 1 |

RATS: 1 (0-1) VATS: 2 (1-3) |

RATS: 5 (4-6) VATS: 6 (5-7) |

NS |

| Wei et al (China, 2024) [23] | RATS: 94 VATS: 94 |

Retrospective comparative | RATS: 12 mo (8-44.7) VATS: 12 mo (7-45) |

Xi 3·RP 8-mm + AP 5-mm |

RATS: 97.5 (79.0-116.5) VATS: 70 (50-90) |

RATS: 27 VATS: 23 |

RATS: 0 VATS: 0 |

RATS: 1 (1-2) VATS: 2 (2-3) |

RATS: 5 (5-6) VATS: 6 (5-7) |

NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).