1. Introduction

The best surgical approach for thymic tumors has always been a controversial issue. Thymoma, although rare (annual incidence 1.3 to 3.2/million), is the most common category of anterior mediastinal tumors in adults [

1].

The last 20 years have represented a period of innovation and improvements in the clinical management of these malignancies. As part of a multidisciplinary approach, surgery is still the treatment of choice for thymic tumors, and complete resection is the therapeutic option allowing the higher rate of cure. [

2]

The anatomical location of the thymus in the antero-superior mediastinum has for many years led to the belief that median sternotomy was the ideal surgical approach allowing a better exposure and radical resection. This indication has been considered particularly effective when thymoma is associated with Myasthenia Gravis due to the need of removing all anterior mediastinal fatty tissue in order to eliminate potential sites of anti-acetylcholine receptor autoantibody production [

3].

In recent years, increasing interest in minimally invasive surgical procedures and improvement in technology and devices has led to the widespread in mediastinal surgery of video-assisted techniques (VATS) techniques, and more recently of the robotic assisted approach [

4].

Based on improved skill and growing amount of clinical data in the setting of robotic assisted surgery for thymoma, an increasing number of comparative studies has appeared in the literature over the recent years assessing the “state of the art” of this technique, but only few studies have analysed the results of robotic interventions in comparison with those of all other main approaches (sternotomy, thoracotomy and VATS) [

5,

6]

The present study aims to evaluate results of the first 2-year experience with RATS thymectomy for thymoma in a high-volume University hospital in the setting of a comparative analysis with homogeneous groups of patients undergoing surgery with radical intent for thymoma through the other main surgical approaches (sternotomy, thoracotomy and VATS).

2. Materials and Methods

Between May 2021 and September 2023, 40 consecutive patients underwent RATS thymectomy for resection with radical intent of stage I to limited stage III thymoma (limited infiltration of the pericardium, lung, mediastinal pleura) at the Division of Thoracic Surgery of the Sant'Andrea Hospital of the Sapienza University in Rome.

Patient’s tumors were classified according to the WHO histo-pathologic classification system of thymic epithelial tumors, 5th edition [

7], and staged in accordance with the Masaoka-Koga clinicopathologic system [

8].

Patients available for follow-up, with complete data about their oncological history and/or the possible presence of Myasthenia or associated paraneoplastic syndromes, treatment and any complications occurring in the peri-operative period (30 days) or at distance from surgery were included. Patients undergoing robotic surgery during the study period for mediastinal tumor other than thymoma were excluded from the study.

All patients underwent routine preoperative investigations such as blood tests and electrocardiogram; echocardiogram and stress/stimulus tests were associated in patients with previous cardiac disease or newly found changes to the electrical tracing.

Patients with possible involvement of the lung parenchyma by the neoplasm and those with Myasthenia Gravis, also underwent preoperative functional tests to assess respiratory performance (Pulmonary Function Test). Patients with an established diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis also underwent neurological reevaluation and optimization of medical therapy before surgery.

The imaging study included total-body computed tomography (CT) with contrast medium and Positron Emission Tomography with fluoro-desoxyglucose-18F (18FDG-PET) in all patients. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed only in patients with specific contraindications to iodine contrast medium infusion. [

9]

All patients included in the study underwent surgery with curative intent and macroscopically complete excision (cR0).

Data regarding the side of surgical approach, overall and actual operative time excluding docking-undocking procedures, associated adjacent structures resection, conversion rate, size of thymoma, histology, stage of disease, postoperative pain, perceived cosmetic results, adjuvant oncologic treatment, were recorded and investigated. Recurrence and mortality after the first month of the operation were also reported for the RATS group but were not object of comparative analysis with the other groups.

To perform a comparative analysis, three additional groups consisting of 40 patients each, who had undergone thymectomy for radical removal of thymoma by other approaches (sternotomy, thoracotomy and VATS) over the previous 5 years, were retrospectively identified using data from the institutional database, operative records, and pathology reports. Patients in the 3 groups were selected after a propensity score, to identify homogeneous statistical samples in terms of demographic characteristics, stage, and histology.

Sternotomy approach was always a total median sternotomy; thoracotomy was performed by a 6 to 9 cm incision with a lateral/subaxillary muscle-sparing technique. VATS was generally performed by a bi-portal or tri-portal access. Locations of surgical ports for VATS approach and use of utility access was chosen based on a case-by-case evaluation. RATS approach was generally standardized using 3 ports placed on the 5th intercostal space at midclavicular line and at the anterior axillary line and on the 3rd intercostal space at the middle axillary line. The side of the video-thoracoscopic or robotic approach was chosen based on the prevalent protrusion of the tumoral mass in the adjacent pleural cavities; in case of equivalent tumor protrusion in both the pleural cavities, the left side was preferred.

Comparison of results obtained in the RATS group was made with those of each group of patients undergoing sternotomy, thoracotomy or VATS. This included the analysis of operative outcomes in terms of surgery duration, associated adjacent structures resection, conversion rate, overall morbidity, tumor size (largest diameter), microscopically ascertained radicality (pR0) and length of postoperative hospital stay. Results concerning postoperative pain were obtained using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum level of pain), based on patients' subjective evaluation at 24 and 48 hours. The cosmetic result at discharge and one month after surgery was also evaluated based on patients' subjective evaluation using a scale from 0 (worst possible result and patient satisfaction) to 10 (best possible result and patient satisfaction) and compared. Last date of follow up was 31 may 2024.

At the time of admission, informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legal guardians for surgical treatment and use of clinical data anonymously for scientific disclosure purposes.

This retrospective study received Institutional Review Board approval (Prot. No. C.8/2023), and it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Data were collected and categorized in Excel-type database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmund, WA). Qualitative variables were expressed as mean or median ± standard deviation (SD), while nominal variables were expressed binary as presence (1) or absence (0) of the event.

2.2. Statistical Significance Is Expressed as a p<0.05 Index

Comparative analysis of the data included comparison of the qualitative variables obtained in patients undergoing RATS in comparison with the other surgical approach techniques using T test, while comparison of the nominal variables was performed using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

All analyses were obtained by using the IBM SPSS Statistics statistical program version 25.0 (SPSS Software, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Forty consecutive patients diagnosed with Masaoka stage I to III (limited-extension) thymoma underwent macroscopically complete surgical excision with thymectomy by robotic-assisted approach over a 29-month period (May 2021-September 2023). The mean age was 62.26 ± 8.57 years (range 41 - 81). There was a prevalence of females (n= 26, 65%). At the time of admission, 8 patients (20%) were found to have Myasthenia Gravis, 3 in ocular form and 5 with bulbar and/or generalized symptoms.

All the RATS interventions were performed using the previously described standardized 3 ports approach to the anterosuperior mediastinum. In all cases the approach was unilateral. The left approach was more frequently used (65%; n=26).

The mean total operative time was 70.60 ± 8.13 minutes (range 70-220); mean operative time excluding docking-undocking procedures was 51.25 ± 16.52 minutes. Associated adjacent structures resections were performed in 4 (10%) patients (wedge right upper lobe lung resection in 2, tangential resection of the left Innominate Vein performed with vascular stapler at the confluence of Keynes veins in 1, pericardial resection in 1). There were no intraoperative events requiring conversion. In a single patient, surgical resection was found to be not microscopically radical (R1) at final examination. Histopathologic analysis results and definitive pathologic staging according to Masaoka system are reported in

Table 1.

If considering patients who underwent associated resection of surrounding structures, pathologic analysis confirmed the presence of stage III disease in a single patient, due to direct infiltration of the pericardium, while right lung parenchyma and vascular wall of the left innominate vein included in the specimen of the other 3 patients were found to be microscopically not infiltrated. The mean size (maximum diameter) of the thymoma was 6.14 ± 1.86 cm (range 4 – 10). The median post operative hospital stay was 3 days, and the mean was 3.36 ± 1.73. There was no operative mortality. The overall morbidity rate was 7.5%. Complications included moderate left pleural effusion requiring thoracentesis in one patient who underwent intervention through right approach. In 2 other patients, recurrent episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation occurred and resolved with pharmacological cardioversion. The subjectively reported pain by the patients according to NRS at 24 hours and at 48 hours had a mean score of 2.2 ± 0.8 and of 2.2 ± 0.7, respectively.

Subjectively perceived cosmetic results using a 0 to 10 scale was reported by patients with a mean score of 9.1 ± 0.5.

At a median follow-up of 24 months (range 9- 36), no patients experienced local or systemic disease recurrence and there was no mortality.

The other three groups of 40 patients undergoing surgical treatment of thymoma by the alternative surgical approaches (sternotomy, thoracotomy, VATS) had homogeneous baseline characteristics which are reported for each group in

Table 1.

Mean overall operative time of RATS was significantly shorter compared to that of sternotomy (0.008) and VATS (0.03). It was similar to the operative time of thoracotomy interventions (p= 0.5), but resulted shorter when analyzing it without the docking-undocking procedures (p= 0.005) [

Table 1].

The overall complication rate did not show significant difference among the 4 groups of patients; however, the major complication rate was lower in the RATS group (7.5%) compared to each of the other 3 groups (VATS, sternotomy, or thoracotomy) presenting the same morbidity rate (12.5%). The distribution of complications in the 4 study groups is summarized in

Table 2.

A higher prevalence of associated surrounding structures resections (

Table 3) was observed in patients operated through sternotomy (35%; 14 patients; p= 0.015).

If considering patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery (VATS and RATS), conversion rate was higher (15%) during VATS compared with RATS (no conversion observed in this group; p=0.026).

No significant difference in the distribution by stage and histologic type was observed in the four groups of the study (

Table 1). Tumor size in patients receiving resection through sternotomy (mean tumor long axis of 7.72 ± 1.25 cm) was found to be slightly higher than that of tumor removed by RATS, although this difference was not statistically significant (p= 0.089). The mean tumor size reported in the group of patients who underwent thoracotomy and VATS was 6.21 ± 1.49 cm and 4.71 ± 0.48 cm, respectively, and did not show significant difference if compared with the mean tumor size in the RATS group.

The mean postoperative hospital stay duration in the group of patients undergoing robot-assisted procedures was significantly shorter compared to the sternotomy group (3.36 ± 1.73 vs. 7.44 ± 3.67; p<0. 001); the mean hospital stay after RATS was also shorter than that reported after thoracotomy, although without statistical significance (3.36 ± 1.73 vs. 4.12 ± 1.51; p=0.104). There was no difference in mean postoperative hospital stay between RATS and VATS groups (3.36 ± 1.73 vs. 3.64 ± 1.38; p=0.530).

Subjectively reported pain by patients at 24 hours and 48 hours resulted significantly better in the RATS group compared to the other approaches (p < 0.05)[

Table 1].

Cosmetic results as reported by the patients were significantly better in the RATS group compared to the sternotomy group (9.1 ± 0.5 vs 4.1 ± 0.8, p= 0.0001) and to the thoracotomy group (6.1 ± 0.9, p= 0.001). Cosmetic scores of the RATS group were also higher than those of the VATS group (8 ± 0.8) with this difference being at the limit of statistical significance (p= 0.052).

After surgery, 4 patients (10%) received adjuvant radiotherapy in the RATS group because of the presence of microscopic neoplastic foci at the resection margin in 1 patient or the presence of capsule infiltration associated with aggressive histology (B3 thymoma) in 3 other patients. In the sternotomy group, post-operative radiotherapy was administered in n=15 patients (37.5%) with capsule infiltration and unfavorable histology (B2-B3). In thoracotomy group, post-operative RT was administered in n= 8 patients (20%) with capsule infiltration unfavorable histology (B2-B3) and in n= 4 patients (10%) with incomplete microscopic excision (R1). Finally, in VATS group, post-operative RT was administered in n=11 patients (27.5%) because of capsule infiltration and unfavorable histology (B2-B3) and in n= 1 patient (2.5%) because of R1. No patient received adjuvant chemotherapy.

4. Discussion

Thymomas are the most common tumors of the anterior mediastinum, accounting for 50% of all anterior mediastinal malignancies. Surgery represents the treatment of choice because radicality of resection has been demonstrated to be the most important prognostic factor [

10].

Median sternotomy has traditionally been the gold standard approach for these neoplasms for a long time [

11]. Similarly, thoracotomy has been considered an adequate alternative option for anterior mediastinal tumors with prevalent protrusion in the pleural cavity on one side. However, over the last decades minimally invasive surgery techniques, including VATS and more recently RATS, have gained increasing acceptance among surgeons and patients, thus becoming the standard of treatment for early stage thymoma. Several studies have recently appeared in the literature comparing the perioperative outcomes of minimally invasive approaches with those of sternotomy and thoracotomy and have shown adequate safety and efficacy of [

12], and comparable, if not superior, oncological outcomes [

13].

Sternotomy is an invasive surgical procedure, which may lead to higher risk of complications such as perioperative bleeding, prolonged postoperative inability, severe dehiscence, and infection [

14]. With the advent of minimally invasive approaches, VATS has become the most popular and commonly used option, resulting in reduction of perioperative major morbidity [

15].

Robotic thymectomy represents the most recent minimally invasive surgical approach to the thymic gland and the anterior mediastinum showing several technical advantages which allow to overcome some limitations of VATS. The Da Vinci System is the most used technology in this field with a well consolidated experience to date. Main technical advantages include high-quality three- dimensional vision with image magnification and more accurate and precise movements of surgical instruments in limited space, especially due to 7 degrees of freedom and the tremor filtering system. This provides a more adequate visualization of anatomical structures with easier identification of surgical planes, allowing a more effective dissection [

16]. Therefore, experiences with this technique published in the literature have reported a significant improvement of results. Shen et al. [

17] and Wu et al. [

18] have compared the short-term outcome of RATS with that of VATS thymectomy by a meta-analysis. RATS resulted in reduction of intra-operative blood loss, shortening of postoperative drainage permanence, reduction of postoperative drainage volume, reduction of hospitalization time, and of postoperative complication rate [

19].

In our present experience, we have compared the surgical results of patients undergoing RATS thymectomy with those of other 3 groups of patients with similar baseline characteristics receiving the same operation by alternative approaches. RATS group presented a significant improvement in term of length of hospital stay compared to the sternotomy group and shorter hospitalization even when compared with thoracotomy and VATS group, although without statistical significance. This data is in line with those of other published series representing the proof of improved efficacy of the robotic technique [

20].

Operative time is obviously always influenced by the learning curve with longer surgery duration at the beginning of RATS experience [

21]. However, the present study, although analyzing the initial RATS experience performed in our Institution, shows favorable results of operative time in comparison with those reported with the other 3 surgical approaches, especially if excluding the docking-undocking procedures. In particular, we reported significantly reduced mean RATS operation time compared to that reported with sternotomy and VATS, and with that of the thoracotomy group if excluding the docking-undocking time.

Thymic tumor size has been frequently considered as a factor to select patients for minimally invasive instead of open thymectomy, and several studies in the literature indicate the size of thymoma up to 3 cm as a safe threshold for a minimally invasive approach [

22]. Kimura and colleagues [

23] reported that VATS approach for thymomas larger than 5 cm increased operative risk of capsular injury. Similarly, over the past decade, the RATS approach has been mainly offered to patients with limited thymoma size [

24]. However, with increasing experience and technical skill, given the advantages provided by improved three-dimensional visualization of anatomical structures and instrument eclecticism, RATS has proved to allow safe resection of lesions of even more than 4 cm [

25]. Comacchio et al., in a multicenter study, found that the median diameter of resected tumor was 4 cm, but in more experienced centers resection of tumors up to 16 cm were performed [

26]. In our experience the mean tumor size in RATS group was 6.14 ± 1.86 cm (including resected thymoma up to 10 cm), without significant differences if compared with the other groups.

Moreover, in the study by Chiba et al., the RATS approach was found to be related with improved postoperative Quality of Life (QOL) in comparison with VATS, principally because of a shorter duration of chest tube which was associated with decreased pain [

12]. In our experience, patients undergoing RATS intervention presented a significant pain reduction both at 24 hours and 48 hours compared to the other approaches (p < 0.05). Even cosmetic results were better in the RATS group, especially when compared to sternotomy (p= 0.0001) and thoracotomy (p= 0.001), thus improving patients’ satisfaction and perception of a better QoL [

27].

To date, limited data are available on long-term oncologic outcomes after RATS. It is however recognized that R0 resection is the most significant surgical prognostic factor [

28]. Comacchio et al. confirmed that a high rate of complete R0 resection (90%) can be achieved using robotic thymectomy for patients with large thymomas, and in a recent analysis of the International Thymic Malignancies Interest Group registry data, Burt and colleagues [

29] observed that neither surgical approach nor tumor size correlated with R0 resection status.

In our experience, R0 was achieved in the 97.5% of patients in the RATS group, thus supporting the efficacy of RATS thymectomy for oncological radicality.

A recent multi-institutional Italian study [

26], reported the need for associated resection of surrounding structures in 57 over a total of 669 patients (8.5%). However, a low conversion rate (3.4%) was reported, which was in line with main previous published data reporting this incidence between 1% and 10% [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This data proves that the need for extended resection can be managed by robotic approach without conversion in most cases. In our experience, associated resection of adjacent structures was performed in 7.5% of patients of the RATS group, which was a lower rate if compared to the sternotomy group. However, we reported no need for conversion due to intraoperative complications or indication for extended resection.

Main limitations of the present study are represented by the inclusion of an initial experience results (which are obviously influenced by the learning curve), and by the observational nature of the study. However, the strength is related to the homogeneity of the groups of patients considered for the comparative analysis, the short study period (limiting differences in patients management over time) and the adequateness of statistical sample if considering the single institution nature and the brief period of the study.

In conclusion, based on data obtained from our initial experience, RATS thymectomy plus thymomectomy, has proven to be a safe and effective technique for the treatment of thymoma up to Masaoka stage III disease with limited extension, allowing accurate and complete excision of the tumor. Operative outcome and morbidity have been shown to be equivalent to or even better than those obtained with the most used alternative approaches. In particular, RATS technique is associated with a significant reduction of operative time, and significantly higher patient-perceived satisfaction in terms of cosmetic outcome and post-surgical pain compared to all other main techniques. Moreover, it is the technique showing the shortest mean hospital stay (among the others) with a significant difference if compared with sternotomy. Short-term oncologic outcomes after robotic resection were also excellent and in line with those reported from major surgical series in the literature

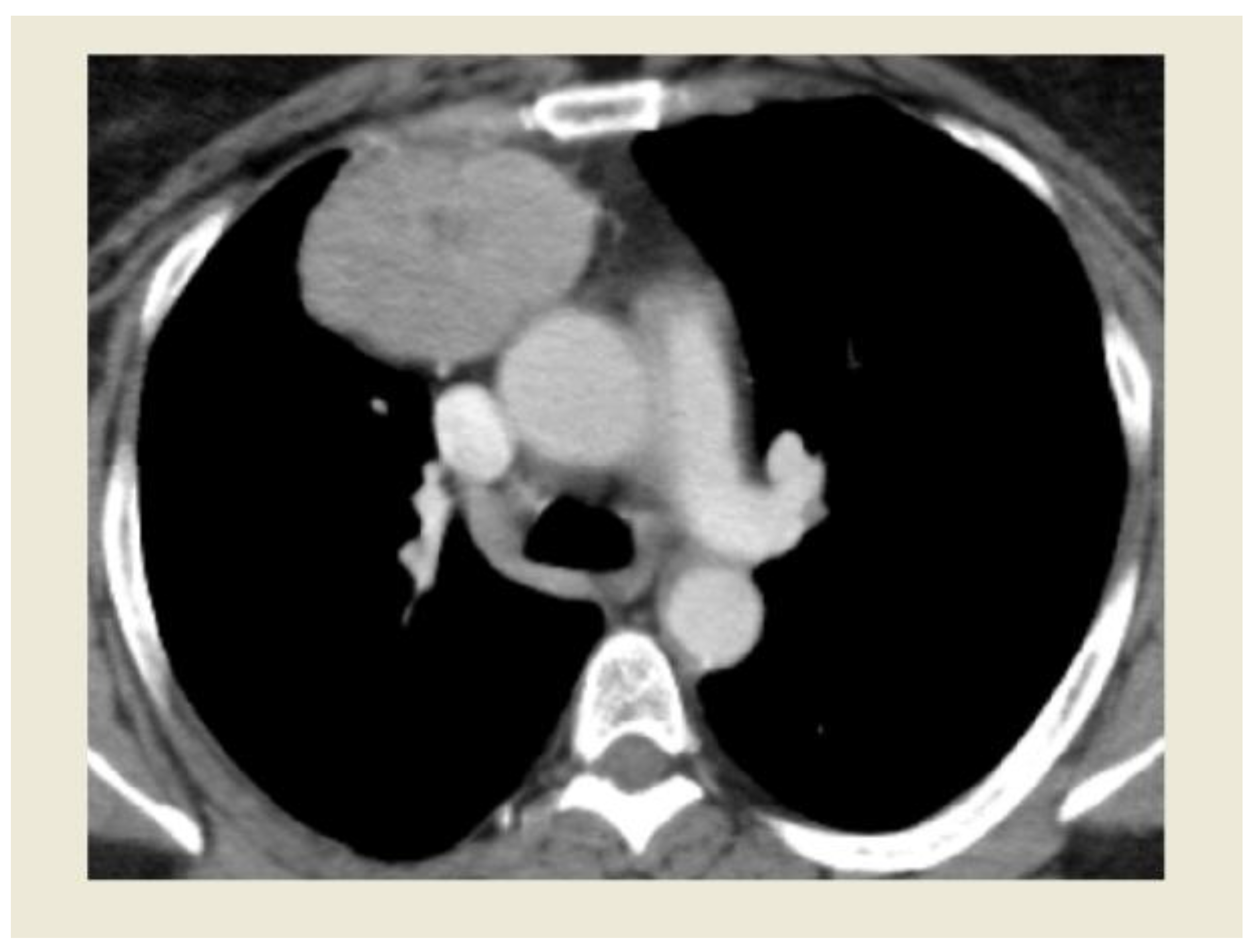

Figure 1.

Image of Thymoma undergoing RATS resection at CT scan.

Figure 1.

Image of Thymoma undergoing RATS resection at CT scan.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative view of thymoma with RATS approach.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative view of thymoma with RATS approach.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Prot. No. C.8/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruffini, E.; Filosso, P.L.; Guerrera, F.; et al. Optimal surgical approach to thymic malignancies: new trends challenging old dogmas. Lung Cancer. 2018, 118, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şehitogullari, A.; Nasır, A.; Anbar, R.; Erdem, K.; Bilgin, C. Comparison of perioperative outcomes of videothoracoscopy and robotic surgical techniques in thymoma. Asian J Surg. 2020, 43, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaba, E.; Cosgun, T.; Ayalp, K.; Toker, A. Robotic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2019, 8, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melfi, F.; Fanucchi, O.; Davini, F.; et al. Ten-year experience of mediastinal robotic surgery in a single referral centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012, 41, 847e851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Tantai, J.C.; Ge, X.X.; et al. Surgical techniques for early- stage thymoma: video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy versus transsternal thymectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014, 147, 1599e1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennathur, A.; Qureshi, I.; Schuchert, M.J.; et al. Comparison of surgical techniques for early-stage thymoma: feasibility of minimally invasive thymectomy and comparison with open resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011, 11, 694e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 5th ed. WHO Classification of Tumours. 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France2021.

- Koga, K.; Matsuno, Y.; Noguchi, M.; et al. A review of 79 thymomas: modification of staging system and reappraisal of conventional division into invasive and non-invasive thymoma. Pathol Int. 1994, 44, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, T.W. Primary tumors and cysts of the mediastinum. In: Shields’ General Thoracic Surgery. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1972:908.

- D'Andrilli, A.; Venuta, F.; Rendina, E.A. Surgical approaches for invasive tumors of the anterior mediastinum. Thorac Surg Clin. 2010, 20, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marulli, G.; Comacchio, G.M.; Schiavon, M.; et al. Comparing robotic and trans-sternal thymectomy for early-stage thymoma: a propensity score-matching study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018, 54, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, Y.; Miyajima, M.; Takase, Y.; Tsuruta, K.; Shindo, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishii, D.; Sato, T.; Aoyagi, M.; Shiraishi, T.; Sonoda, T.; Watanabe, A. Robot-assisted and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for thymoma: comparison of the perioperative outcomes using inverse probability of treatment weighting method. Gland Surg 2022, 11, 1287–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedant, A.J.; Handorf, E.A.; Su, S.; Scott, W.J. Minimally invasive versus open thymectomy for thymic malignancies: systematic review and meta-ana- lysis. J Thorac Oncol 2015, 11, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizi, G.; D'Andrilli, A.; Sommella, L.; Venuta, F.; Rendina, E.A. Transsternal thymectomy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015, 63, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Tjahjono, R.; Phan, K.; Yan, T.D. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus open thymectomy for thymoma: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2015, 4, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; et al. A comparison of three ap- proaches for the treatment of early-stage thymomas: robot- assisted thoracic surgery, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and median sternotomy. J Thorac Dis. 2017, 9, 1997e2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Che, G. Robot-assisted thoracic surgery versus video- assisted thoracic surgery for treatment of patients with thymoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorac Cancer. 2022, 13, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.J.; Zhang, F.Y.; Xiao, Q.; Li, X.K. Does robotic-assisted thymectomy have advantages over video-assisted thymectomy in short-term outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021, 33, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.Y.; Wang, W. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery vs. sternotomy for thymectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Surg. 2023, 9, 1048547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.H.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Park, I.K.; Kim, Y.T. Robotic thymectomy in anterior mediastinal mass: propensity score matching study with transsternal thymectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016, 102, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulli, G.; Rea, F.; Melfi, F.; et al. Robot-aided thoracoscopic thymectomy for early-stage thymoma: a multicenter European study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012, 144, 1125e1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilshire, C.L.; Vallieres, E.; Shultz, D.; Aye, R.W.; Farivar, A.S.; Louie, B.E. Robotic resection of 3 cm and larger thymomas is associated with low peri- operative morbidity and mortality. Innovations (Phila) 2016, 11, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Inoue, M.; Kadota, Y.; et al. The oncological feasi- bility and limitations of video-assisted thoracoscopic thy- mectomy for early-stage thymomas. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013, 44, e214–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, Y.W.; Kang, C.H.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Jeon, J.H.; Park, I.K.; et al. Early clinic- al outcomes of robot-assisted surgery for anterior mediastinal mass: its superiority over a conventional sternotomy approach evaluated by pro- pensity score matching. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014, 45, e68–e73; discussion e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneuertz, P.J.; Kamel, M.K.; Stiles, B.M.; Lee, B.E.; Rahouma, M.; Nasar, A.; et al. Robotic thymectomy is feasible for large thymomas: a propensity- matched comparison. Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 104, 1673–1678. [PubMed]

- Comacchio, G.M.; Schiavon, M.; Zirafa, C.C.; De Palma, A.; Scaramuzzi, R.; Meacci, E.; et al. Robotic thymectomy in thymic tumours: a multicentre, na- tion-wide study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pompili, C.; Koller, M.; Velikova, G.; et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 summary score reliably detects changes in QoL three months after anatomic lung resection for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 2018, 123, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioni, G.; Palleschi, A.; Mendogni, P.; Tosi, D. Approaches and outcomes of Robotic-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (RATS) for lung cancer: a narrative review. J Robot Surg. 2023, 17, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, B.M.; Yao, X.; Shrager, J.; et al. Determinants of complete resection of thymoma by minimally invasive and open thy- mectomy: analysis of an international registry. J Thorac Oncol 2017, 12, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Na, K.J.; Kang, C.H.; Park, S.; Park, I.K.; Kim, Y.T. Robotic subxiphoid thymectomy versus lateral thymectomy: a propensity score-matched comparison. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 62, ezac288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).