1. Introduction: Beyond Singularities and Dark Components

The standard cosmological narrative faces two profound challenges: the initial singularity of the Big Bang and the unexplained dark components dominating the universe’s energy budget [

1]. Although bounce cosmologies offer alternatives to the singularity [

2,

3], they often lack a concrete physical mechanism for the rebound itself.

Our approach builds upon a radical re-conception of matter’s fundamental nature. In a series of works [

4,

5], we have developed a paradigm where particles are not point-like entities but coherent standing wave structures in a dynamic spatial medium (the Michelson-Morley null result, without the prior assumption of a non-existent medium, only implies a specific relationship between the longitudinal and transverse deformations of matter in motion [

18]). This view naturally accommodates Lockyer’s non-conventional proton model [

6], which—despite its simplicity—achieves extraordinary precision in calculating mass ratios (proton/electron to 7 significant figures, neutron/electron to 6 figures) using only fundamental constants: the fine-structure constant

,

geometric scaling, and CODATA values, with no adjustable parameters.

This paper proposes that similar organizational principles—though implemented through different physical mechanisms—operate from quantum to cosmic scales, providing a physical mechanism for a singularity-free bounce. Lockyer’s geometric progression for nucleons (a quantum-intrinsic, discrete hierarchy of energy levels) finds its gravitational analogue in the pressure-dependent layering of exotic matter within collapsing black holes (a continuous, thermodynamically-emergent structure). Both systems exhibit "Russian doll" architectures, suggesting a deep organizational principle that extends from subatomic particles to cosmological objects.

This framework decisively resolves the entropy paradox while addressing an apparent violation of the second law of thermodynamics. During the collapse phase, gravitational contraction progressively organizes matter into these layered exotic structures, systematically reducing entropy—with black holes acting as effective entropy sinks. This occurs even as entropy-increasing processes continue in the external universe. Importantly, the net balance is a continuous decrease in total entropy throughout both expansion and contraction phases, as gravitational organization within collapsing structures dominates over dispersive processes elsewhere. Entropy reaches its minimum at the bounce threshold, setting the stage for the subsequent cascade that will abruptly maximize it, initiating a new expansion cycle.

The subsequent instability cascade then triggers an abrupt phase transition where this highly organized exotic matter converts into disorganized radiation, instantaneously maximizing entropy to initiate the new expansion phase. Thus, each cycle naturally alternates between entropy minima (organized matter) and maxima (thermal radiation), with the second law preserved in local environments while the global entropy evolution follows a sawtooth pattern dictated by gravitational organization.

This framework not only addresses cosmological-scale phenomena but also provides insights into stellar astrophysics. The same exotic matter formation and destabilization mechanism that drives cosmological bounces offers a natural explanation for core-collapse supernovae, resolving the longstanding "supernova energy problem" where imploding shock waves mysteriously gain energy rather than dissipating it. This cross-scale applicability demonstrates the unifying power of our wave-based matter paradigm.

2. The Lockyer Proton Model: Foundation Without Ad Hoc Assumptions

2.1. Essential Features and Predictive Power

Lockyer’s model [

6,

7] describes the proton’s mass-energy as arising from 18 discrete, geometrically scaled energy levels (

progression) fundamentally tied to a positron base state. This hierarchical quantum structure—where higher-energy (shorter-wavelength) states nest within lower-energy ones—forms an intrinsic "onion-like" energy layering. The

scaling factor likely emerges from the coupling between energy levels, a topic reserved for future investigation. Importantly, these are energy levels whose geometric progression reflects fundamental organizational principles rather than spatial shells in the classical sense.

This simple, parameter-free construction—using only , , ℏ, c, and geometric constants—delivers a predictive tour de force: the calculated proton/electron mass ratio (1836.1521964) matches the CODATA value (1836.15267343) to seven significant figures. Furthermore, the model incorporates the electron’s anomalous magnetic moment via from first principles. This remarkable success suggests the model captures an essential truth: nucleons are hierarchical wave systems with geometrically organized energy shells. While this model is unconventional and its physical interpretation remains speculative, its numerical precision demands serious consideration as a potential structural blueprint for nucleons.

2.2. Compatibility with Standard Model

Importantly, this model is not incompatible with quarks in the Standard Model. We propose that quarks represent temporary excitations appearing during high-energy collisions in particle accelerators. These are transient resonant states of the underlying wave structure, not fundamental constituents in our paradigm. The permanent, stable structure is the layered configuration described by Lockyer.

2.3. Implications for High-Density Physics

A natural question arises from Lockyer’s layered nucleon structure: if ordinary nucleons derive their mass from 18 hierarchical energy levels anchored to a positron base, what happens under extreme gravitational compression? We propose that under sufficient pressure, additional energy levels can be stabilized beyond the usual 18, creating what we term "exonucleons" with level count increasing with compression. This avoids the unphysical notion of infinite compression—the system has finite but pressure-dependent capacity to incorporate additional energy layers.

3. The Bounce Mechanism: Phase Transitions and Dynamical Instability

3.1. Gravitational Organization During Contraction

Contrary to the standard view where contraction increases entropy, our model predicts increased organization through gravitational structuring. Rather than progressing toward maximum disorder, collapsing matter undergoes a series of organizing phase transitions. Initially dispersed ordinary matter (stars, galaxies) represents a high-entropy state. As collapse proceeds, nuclei dissolve into neutron matter (reduced entropy), which further compresses into black holes (even lower entropy). The final stage involves the development of exotic matter with pressure-dependent layering, representing the minimal entropy configuration. Each stage thus represents a higher organization, decreasing gravitational entropy despite increasing density.

3.2. The Structured Black Hole: Onion-like Layering

Black holes in this view are not singularities but highly organized structures with radially varying exotic matter. The layer count increases inward, reaching maximum at the core. The exotic matter is fully formed at each radius, with the layer count determined by local pressure conditions. This creates an onion-like structure where different "shells" of the black hole contain exotic matter with different degrees of density.

This gravitational layering mechanism, while producing structures superficially similar to Lockyer’s quantum layering (both are "onion-like"), operates on fundamentally different principles with a crucial commonality: both exhibit discrete, quantized transitions. Whereas Lockyer’s proton structure comprises exactly 18 discrete energy levels with fixed geometric progression, the black hole’s exotic matter organizes into successive discrete shells where each additional shell corresponds to energy levels, with n representing the nth exotic matter shell in the black hole and m the number of additional energy levels required to stabilize each successive exotic matter layer (the specific progression factor—whether 1, 3, or another integer—remains to be determined theoretically). Thus, while Lockyer’s layering is quantum-intrinsic and fixed, the black hole’s layering is pressure-induced and incrementally scalable, yet both exemplify how discrete hierarchical organization manifests across scales, from quantum particles to cosmic objects.

3.3. The Sponge Analogy: Pressure-Dependent Energy Absorption

Exotic matter behaves like a cosmic sponge, with its energy absorption capacity proportional to the external pressure-to-internal temperature ratio. Thermal motion works against pressure-induced organization, creating a delicate balance. When exceeds certain thresholds, new layers can form; when it drops below the stability limits, layers may shed energy. This pressure-to-temperature ratio becomes a critical parameter that governs the stability of exotic matter structures.

3.4. The Bounce Trigger: From Maximum Compression to Runaway Disintegration

The minimum entropy state occurs when the primordial black hole reaches its maximum compression, with all the mass converted into layered exotic matter of increasing density arranged in concentric shells. The bounce initiates when this equilibrium is disrupted, most likely through the merger of two major black holes whose tidal forces are sufficient to dislocate exotic matter layers.

Exotic matter requires enormous pressure to remain confined. A sudden pressure variation triggers its disintegration. When disintegration affects a significant region, the gravitational field supported by that exotic matter decreases. This in turn "releases" adjacent layers of exotic matter, which disintegrate in turn, causing their gravitational support to collapse. This creates a positive feedback loop: reduced gravity → reduced pressure → more disintegration → further reduction in gravitational support.

The resulting runaway cascade leads to complete disintegration of all exotic matter. During this massive disintegration event, entropy jumps from its minimum (highly organized exotic matter) to its maximum (disorganized radiation). The immense gravitational field vanishes, the black hole ceases to exist, and energy begins radiating outward from the former black hole’s perimeter, cooling as it expands.

3.4.1. Dynamical Instability Cascade (Preferred Mechanism)

The bounce initiates through a domino effect: localized pressure reduction (from tidal effects, rotation, or merger dynamics) causes exotic matter at that location to convert to radiation. This reduced mass decreases the local gravitational field, lowering the pressure on adjacent layers. Those adjacent layers then destabilize, converting to energy, beginning a chain reaction. The process creates positive feedback as reduced gravitational support accelerates the conversion, leading to runaway evaporation of the entire primordial black hole into a radiation bath. This domino effect naturally explains the rapid, complete transition needed for bounce.

3.4.2. Alternative: Critical Pressure-Temperature Ratio

If reaches a critical value where the system’s energy storage capacity exceeds its structural integrity, spontaneous energy release could occur. This represents a thermodynamic instability rather than a dynamical cascade but could operate in parallel or as an alternative trigger mechanism.

3.5. Energy Release and Neutrino Production Cascade

The cascade instability releases gravitational binding energy stored in the layered exotic matter structure through a multi-stage process with significant neutrino production. The conversion follows a nonlinear chain reaction:

with energy transformation:

Crucially, this is not a single-step process but a recursive cascade where energy released from one layer’s disintegration can trigger immediate reformation and subsequent disintegration of exonucleons. This creates a feedback loop:

Layer disintegration: Exotic matter at pressure disintegrates, releasing energy

Energy redistribution: Part of converts to neutrinos, part becomes kinetic/thermal energy

Adjacent layer stimulation: The remaining energy increases temperature/pressure conditions for adjacent layers

Reformation possibility: Under the right conditions, some energy may temporarily re-form exotic matter

Recursive disintegration: This newly formed exotic matter immediately disintegrates, repeating the cycle

The recursive nature dramatically amplifies neutrino production compared to a single-step process. Each disintegration cycle converts a fraction

f of mass-energy to neutrinos. After

n recursive cycles starting with initial exotic matter mass

, the total neutrino energy becomes:

In practice, the process terminates when the pressure drops below the exotic matter formation threshold, but multiple cycles can occur. For typical values and cycles, neutrino production is enhanced by factors of 2-5 compared to single-step conversion.

This neutrino-rich disintegration explains several cosmological features:

Primordial neutrino background: Provides the energy density observed in cosmological models

Bounce energy source: Neutrinos drive initial expansion through condensation mechanisms described in

Section 7.5

Baryonic mass accounting: Standard cosmology’s "missing baryon problem" could correspond in part to mass converted into neutrino energy through exotic matter disintegration processes

Process efficiency: Recursive cycles ensure near-complete conversion of exotic matter to usable expansion energy

The process mirrors and extends standard nuclear reactions (matter→energy conversion) to cosmological scales while incorporating the unique recursive enhancement characteristic of hierarchical exotic matter structures. This recursive amplification mechanism ensures that even a modest initial exotic matter reservoir can produce sufficient neutrino energy to drive cosmic expansion.

3.6. Application to Core-Collapse Supernovae: Solving the Energy Problem

The formation and destabilization of exotic matter provides a compelling solution to one of the longest-standing puzzles in stellar astrophysics: the mechanism of core-collapse supernovae. In standard models, when a massive star exhausts its nuclear fuel, its iron core collapses under gravity. Theory predicts this should form a neutron star or black hole, with the imploding shock wave dissipating energy as it converges toward the center. However, observations show that these shock waves somehow gain energy, producing spectacular explosions that disperse heavy elements throughout galaxies.

Our exotic matter mechanism offers a natural explanation. During core collapse, when densities approach nuclear levels ( g/cm3), conditions become sufficient to initiate exotic matter formation. Just as in cosmological bounces, but on stellar scales, nucleons begin incorporating additional energy levels beyond their normal 18-layer structure. This exotic matter acts as a pressure-dependent energy sponge:

Energy absorption phase: As the shock wave converges, its energy is absorbed by the forming exotic matter, which stabilizes under extreme pressure. This explains why the shock wave does not dissipate—its energy is being stored in the structural reorganization of matter.

Pressure-dependent stability: The exotic matter remains stable only while extreme pressure is maintained. When the shock wave passes and pressure temporarily decreases (or oscillates), the stability condition is violated.

Energy release phase: The exotic matter destabilizes, releasing the stored energy outward rather than continuing inward. This creates a powerful rebounding shock that drives the supernova explosion.

Neutrino production: The exotic matter disintegration produces copious neutrinos, consistent with observed neutrino bursts from supernovae like SN 1987A.

This mechanism elegantly resolves several supernova puzzles simultaneously:

Energy source: Provides the J needed for explosion from exotic matter disintegration

Timing: Explains the delayed explosion (seconds after collapse) as the time for exotic matter to form and destabilize

Neutrino burst: Naturally produces the observed neutrino emission

Nucleosynthesis: The explosive conditions create heavy elements via r-process nucleosynthesis

Remnant diversity: Determines whether a neutron star or black hole forms based on how much exotic matter destabilizes versus remains stable

It is particularly significant that this explanation requires no new physics beyond what we already propose for cosmological bounces. The same exotic matter formation and cascade destabilization operates across 18 orders of magnitude in scale—from stellar cores to primordial black holes—demonstrating the unifying power of our hierarchical matter paradigm. This cross-scale consistency provides strong support for the physical reality of exotic matter as a genuine phase of matter under extreme compression.

4. Resolving Classical Cosmological Paradoxes

4.1. The Entropy Problem: Gravitational Organization

The entropy problem finds a compelling resolution within the cyclical framework presented here. During the contraction phase, gravitational forces organize matter into increasingly structured configurations rather than randomizing it. The progression from dispersed matter (high entropy) to neutron stars (moderate entropy) to black holes containing organized exotic matter (low entropy) means each cycle ends with minimal entropy and begins with maximal entropy from the thermalized radiation of the bounce. Gravitational contraction thus serves as an organizing principle rather than an entropic randomizer, eliminating the fine-tuning problem of initial low entropy.

4.2. The Flatness and Horizon Problems

A strong implication of this model concerns the cosmological horizon and flatness problems. The bounce originates from a structured, finite object—the primordial black hole containing organized exotic matter. Its geometry naturally determines initial conditions: where . For a massive, relaxed black hole that has undergone many merger events, spherical symmetry is natural, yielding . The "fine-tuning" disappears because we begin from a specific physical structure, not a singular mathematical point.

The horizon problem is resolved through multiple complementary mechanisms. The extended contraction phase naturally flattens and homogenizes the universe through gravitational relaxation over many cycles. More fundamentally, in our wave-based reality, coherence can be established through non-local mechanisms inherent to the spatial medium itself. The IN/OUT wave structure of particles maintains phase relationships, while the spatial medium provides a universal reference frame for synchronization. The uniformity of the CMB therefore reflects the inherent coherence properties of the spatial medium as it transitions from organized exotic matter to radiation, not thermal equilibrium established through conventional causal contact.

4.3. Black Hole Information Paradox

If black holes contain organized exotic matter rather than singularities, information is preserved in their layered structure and released during the bounce evaporation. The exact layer configuration encodes the black hole’s formation history, providing a natural resolution to the information paradox without requiring radical modifications to quantum mechanics or gravity.

4.4. The Monopole Problem: Avoiding Topological Defects

Grand Unified Theories predict abundant production of magnetic monopoles during phase transitions in the early universe, yet none are observed. Our model avoids their overproduction entirely because the bounce is not a hot Big Bang with spontaneous symmetry breaking, but a controlled phase transition from organized exotic matter to radiation. Without rapid cooling and symmetry breaking, topological defects such as monopoles simply do not form in significant numbers.

4.5. From Age Anomalies to a Bounce Multiverse

Regarding the size and age problems, our model not only resolves them within a single cycle but naturally accommodates a broader cosmological architecture. Each bounce releases the immense gravitational binding energy stored in the organized exotic matter of a primordial black hole, yielding an energy scale commensurate with our observable universe.

Fundamentally, this framework leaves the door open to a multiverse of Big Bounces occurring in distant regions and at different epochs. Similar to how a star gathers material within its gravitational sphere of influence, each bounce concerns a vast but finite causal region, with no sharp boundaries between these regions. Structures can thus form in previous cycles or in adjacent bounce regions, potentially explaining the surprisingly mature galaxies at high redshift observed by JWST as remnants from pre-bounce structures or as galaxies belonging to the causal sphere of neighboring older bounces.

Consequently, the universe appears "too large" and contains objects "too old" only if one assumes a single, globally synchronous cycle beginning from a hot Big Bang—an assumption our model explicitly rejects in favor of a mosaic of asynchronously evolving bounce regions embedded within a continuous spatial medium.

5. Resolving Modern Cosmological Tensions

5.1. The Hubble Tension (H0)

Our model naturally accommodates different expansion rates in different regions, as local expansion depends on matter concentration and the resulting gravitational field strength. The expansion mechanism operates through neutrino condensation—a process where neutrinos modify the local spacetime metric when they encounter regions where their momentum is sufficient to overcome local gravitational binding. Regions with weaker gravitational fields allow more efficient neutrino condensation, leading to faster expansion.

The observed tension between local measurements (from Cepheid variables and Type Ia supernovae) and early-universe measurements (from the CMB) could reflect several features of our framework. First, our local region may have experienced slightly more efficient neutrino condensation due to specific local conditions. Second, different regions may be at different stages of the condensation cycle, with some regions having exhausted their "condensable neutrino fuel" while others are still actively expanding. Third, residual inhomogeneities from the bounce evaporation process could create regional variations in expansion rate that persist across cosmic time.

Rather than requiring a single universal expansion rate, our framework expects and explains regional variations. What appears as a "tension" in models assuming perfect global homogeneity becomes a natural prediction in our model of regionally variable expansion driven by differential neutrino condensation efficiency.

5.2. The S8 Tension (Clustering)

The parameter quantifies the clustering of matter on scales of 8 Mpc/h. The tension between CMB-based predictions and direct large-scale structure measurements finds a natural explanation in our framework through differential expansion driven by variable neutrino condensation.

The distribution of matter in filaments and voids emerges naturally from regional expansion variations. Regions that experience more efficient neutrino condensation expand more rapidly, becoming underdense "voids." Conversely, regions where condensation is less efficient expand more slowly, becoming overdense "filaments" and clusters. This process creates a self-amplifying pattern: regions that begin slightly underdense experience weaker gravitational fields, allowing more efficient neutrino condensation, which drives further expansion and increased underdensity.

The Great Attractor represents a region of higher energy density where expansion was less efficient, creating a gravitational focal point. The Boötes Void, conversely, represents a region where neutrino condensation proceeded more rapidly, creating an expanding underdense region. This differential expansion, driven by variable neutrino condensation efficiency, naturally produces the observed large-scale structure without requiring fine-tuning of initial conditions or dark matter properties.

5.3. Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry from Statistical Fluctuations

The apparent matter-antimatter asymmetry finds a natural explanation in statistical fluctuations within our wave-based framework, without requiring any fundamental symmetry violation.

In Lockyer’s model and our extension:

Protons are constructed from a positron core with additional energy shells

Antiprotons are constructed from an electron core with additional energy shells

Neutrons are protons that have captured an electron (plus binding energy)

Antineutrons are antiprotons that have captured a positron (plus binding energy)

Crucially, both matter and antimatter structures contain exactly the same constituents—one positron and one electron each—but arranged differently:

In matter: Positrons at nucleon cores, electrons either captured (in neutrons) or free

In antimatter: Electrons at antinucleon cores, positrons either captured (in antineutrons) or free

The asymmetry emerges not from different probabilities, but from inevitable statistical fluctuations in a finite system. Consider the analogy of coin tossing: when tossing a coin N times, the probability of obtaining exactly heads and tails is vanishingly small for large N. Similarly, during the intense particle production era following the bounce:

Statistical fluctuation: The formation of neutrons versus antineutrons, while having equal individual probabilities, inevitably shows fluctuations in any finite sample

Freeze-out dynamics: As the universe expands and cools, interactions become less frequent. A small initial fluctuation ( part in ) gets "frozen in" when annihilation rates drop below expansion rates

Thus, there is no "disappearance" of antimatter in the conventional sense. Electrons and positrons remain equally abundant in the universe, but their distribution differs:

This explanation eliminates the need for fine-tuned CP violation parameters or new physics. The observed asymmetry emerges naturally from finite statistics in the early universe, while maintaining exact symmetry at the fundamental level of constituent particles.

6. Observational Status and Relation to Standard Cosmology

6.1. Preserving Successful Predictions of the Big Bang Model

Our model deliberately preserves the successful predictions of standard Big Bang cosmology while eliminating its conceptual problems. The thermal history of the universe—from nucleosynthesis to recombination—proceeds essentially as in the standard model, with one crucial difference: the initial conditions are set by a bounce from organized exotic matter rather than emerging from a singularity.

The key observational pillars of Big Bang cosmology remain intact:

Primordial nucleosynthesis: As shown in

Appendix A, the temperature range for hadronization and nucleosynthesis (

K to

K) matches precisely with standard cosmology, explaining the observed light element abundances (D, He, Li).

Cosmic Microwave Background: A blackbody spectrum at 2.725 K emerges naturally from the cooling radiation bath following the bounce.

Expansion history: Hubble’s law and the redshift-distance relation follow from metric relaxation and neutrino-driven expansion, with expansion rates evolving as described below.

Large-scale structure: Hierarchical structure formation proceeds through gravitational instability in an expanding background.

This strategic preservation is deliberate: any viable cosmological model must explain why the universe looks as if it emerged from a hot, dense state. Our model provides a physical mechanism for that appearance without the conceptual baggage of singularities and unexplained dark components.

6.2. Distinctive Predictions and Testable Differences

While preserving standard cosmology’s successes, our model makes several distinctive predictions that could eventually distinguish it from CDM:

6.2.1. Multiverse Signatures and JWST Anomalies

Our framework naturally accommodates a multiverse of asynchronous bounce regions, providing a principled explanation for JWST observations of unexpectedly mature galaxies at high redshift. While CDM struggles with these anomalies, requiring adjustments to galaxy formation models, our multiverse interpretation offers a compelling alternative: some observed high-redshift structures may belong to adjacent, older bounce regions rather than our causal patch.

This prediction gains support from:

Systematic regional variations in galaxy maturity that might indicate different cosmic ages

Coherent "patches" in the sky with different apparent evolutionary timelines

The persistence of anomalies despite improved understanding of galaxy formation physics

Furthermore, the multiverse aspect could explain exceptional ultra-high-energy cosmic rays that defy conventional astrophysical explanations. Radiation produced during bounce events in neighboring regions could travel to our universe, appearing as anomalous high-energy events with no identifiable source within our cosmic horizon.

6.2.2. Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays from Neighboring Bounce Regions

Our multiverse framework provides a natural explanation for ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) that defy conventional astrophysical explanations. These particles, with energies exceeding eV—well above the Greisen-Zatsepin-Kuzmin (GZK) cutoff of eV—pose a significant challenge to standard cosmology: no known astrophysical sources within our cosmic horizon can accelerate particles to such energies, and they should interact with the cosmic microwave background over intergalactic distances, losing energy through pion production.

In our framework, these anomalous UHECRs could originate from neighboring bounce regions undergoing their own bounce events. The violent processes during exotic matter disintegration and subsequent particle production in adjacent universes could generate particles with extreme energies. Some fraction of these particles might traverse the boundary between bounce regions—possible in our continuous spatial medium model where regions blend smoothly without sharp discontinuities—and enter our universe.

This interpretation could lead to verifiable predictions such as anisotropic distribution, characteristics of the energy spectrum, correlation with other anomalies, or even a different chemical composition depending on the direction of origin.

Current observatories like the Pierre Auger Observatory and Telescope Array have detected several such extreme events without clear astrophysical counterparts. While alternative explanations exist (neutrino primaries, topological defects, Lorentz invariance violation), our multiverse interpretation offers a principled framework that simultaneously explains UHECRs, JWST anomalies, and potential CMB anomalies through a single coherent picture of asynchronous bounce regions.

6.2.3. Supernova Neutrino Signatures and Energy Mechanism

Building on the exotic matter mechanism described in

Section 3.6, our model makes specific predictions for supernova observations:

Two-phase neutrino signal: A distinct neutrino signature with initial emission from nuclear processes followed by a secondary burst from exotic matter disintegration

Characteristic energy spectra: Neutrino energy distributions reflecting the layered structure of exotic matter formed during collapse

Timing correlations: Precise timing between neutrino emission peaks and shock revival in supernova light curves

Remnant-dependent signals: Different neutrino signatures for supernovae that produce neutron stars versus those that form black holes

The next Galactic supernova observed by next-generation neutrino observatories (Hyper-Kamiokande, DUNE, JUNO) will provide crucial tests of these predictions. The exotic matter mechanism naturally explains the delayed shock revival and provides the missing J of energy without requiring ad hoc neutrino reheating mechanisms.

6.2.4. Dynamical Expansion History

Our model provides a natural explanation for the evolving expansion rate of the universe through staged neutrino condensation:

Early rapid expansion: Driven by high-energy neutrinos produced during the bounce cascade and subsequent particle-antiparticle annihilation era. The massive initial neutrino production provides the energy for metric relaxation and early expansion.

Mid-era decelerated expansion: As high-energy neutrinos are exhausted, expansion continues through condensation of medium-energy neutrinos and lower-energy neutrinos from ongoing stellar processes, particularly from supernovae and other extreme astrophysical events. This maintains expansion but at a decreasing rate.

Late-time acceleration: When expansion creates sufficiently weak gravitational regions between clusters, accumulated low-energy neutrinos—some primordial, others from stellar processes—can finally condense. This creates a positive feedback loop: expansion weakens gravity → more neutrinos condense → further expansion → even weaker gravity. This "snowball effect" naturally produces the observed late-time acceleration without requiring dark energy.

This dynamical sequence explains the complete expansion history naturally, connecting early universe physics to current acceleration through a single unified mechanism of neutrino condensation with energy-dependent thresholds.

6.2.5. Black Hole Interiors and Mergers

The most fundamental difference concerns black hole nature. In CDM, black holes contain singularities; in our model, they contain organized exotic matter. This difference might manifest in:

Gravitational wave signatures from mergers, particularly in the ringdown phase where interior structure could affect quasinormal modes

Tidal disruption events that could reveal material interiors rather than event horizons

Evaporation timescales for primordial black holes, differing from Hawking’s prediction

However, detecting these differences requires extraordinary precision that may remain beyond near-future capabilities.

6.2.6. Regional Variations in Expansion Rate

The Hubble tension ( discrepancy) finds a natural explanation in our model: different regions expand at different rates due to variable neutrino condensation efficiency. This predicts:

Anisotropic expansion that might be detectable through careful analysis of supernova data in different directions

Correlation between expansion rate and local matter density

Evolution of the Hubble parameter that differs from CDM predictions

Current evidence for such anisotropies is marginal but could become significant with larger datasets.

6.2.7. Absence of Dark Matter Particles

Our model replaces particle dark matter with neutrino-mediated gravitational fields. This predicts:

No direct detection of WIMPs or other dark matter particles

Specific correlations between stellar activity and galactic dynamics

Evolution of galactic rotation curves tied to star formation history

The continued null results in direct detection experiments are consistent with (though not proof of) our framework.

6.3. The Challenge of Discrimination

Discriminating between our model and CDM presents significant challenges because:

Both models fit existing cosmological data reasonably well

The most distinctive predictions involve extreme conditions (black hole interiors, early universe, multiverse boundaries) that are difficult to probe

Many predictions are qualitative rather than quantitative at this stage

The most promising discrimination avenues involve:

Precision cosmology: Measuring higher-order CMB statistics (non-Gaussianity, polarization B-modes) with next-generation experiments

Gravitational wave astronomy: Studying black hole mergers with future detectors (LISA, Einstein Telescope)

Neutrino astronomy: Detecting cosmological neutrino backgrounds and supernova signatures with next-generation observatories

JWST and future telescopes: Mapping early galaxy formation and searching for multiverse signatures

Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays: Identifying anomalous events that might originate from neighboring bounce regions, particularly looking for directional correlations with other potential multiverse signatures

Multi-messenger astronomy: Correlating anomalies across different observational channels (photons, neutrinos, gravitational waves, cosmic rays)

A particularly intriguing test would involve searching for spatial correlations between:

UHECR arrival directions

Regions with anomalous galaxy maturity in JWST data

CMB temperature or polarization anomalies

Large-scale structure peculiarities

Such multi-channel correlations would be difficult to explain within standard cosmology but emerge naturally in our multiverse framework where different observational signatures all trace back to the same underlying mosaic structure of asynchronous bounce regions.

6.4. Theoretical Advantages as Evidence

Given the observational challenges, the primary evidence for our model currently lies in its theoretical advantages:

Singularity avoidance: Replaces mathematical infinities with physical processes

Dark component elimination: Explains phenomena without unexplained particles or energy

Unification: Connects particle physics (Lockyer model) to cosmology

Paradox resolution: Naturally solves entropy, horizon, flatness, and matter-antimatter problems

Multiverse integration: Provides framework for JWST anomalies and ultra-high-energy events

Supernova explanation: Solves the core-collapse supernova energy problem through the same exotic matter mechanism

Dynamical expansion: Explains complete expansion history through staged neutrino condensation

Conceptual coherence: All components emerge from a single wave-based paradigm

These theoretical virtues, combined with the model’s ability to preserve standard cosmology’s empirical successes while addressing its conceptual shortcomings, constitute a strong case for its consideration as a viable alternative. Future work should focus on developing the mathematical formalism to make more precise, testable predictions, particularly regarding the quantization of exotic matter layers, the dynamics of neutrino condensation, multiverse observational signatures, and supernova neutrino spectra.

7. Connection to Our Wider Paradigm

7.1. Wave-Based Matter Foundation

Particles as standing waves naturally accommodate layered structures—different layers correspond to different harmonic modes of the spatial medium’s vibrations. The Lockyer model’s success suggests this wave-based perspective captures fundamental truths about matter’s nature. In this view, the geometric progression of energy levels in nucleons emerges from the natural harmonic series of a vibrating spatial medium, much like the harmonic series of a vibrating string. This same principle of harmonic organization extends to cosmic scales, where gravitational pressure creates layered exotic matter structures with their own characteristic scaling.

7.2. Fine-Structure Constant Stability

The fine-structure constant ’s remarkable constancy across time and space reflects the stable elastic properties of the spatial medium in our framework. However, near the bounce event, under conditions of extreme pressure and temperature, the spatial medium’s properties might temporarily change, permitting detectable variations in that could affect layer stability in exotic matter. This provides a potential link between cosmological parameters and fundamental constants, suggesting that what we measure as "constants" in our local environment might represent equilibrium values of a dynamic spatial medium that can undergo phase transitions under extreme conditions.

7.3. Galactic Dynamics via Energy Diffusion

The energy released by stars (99% as neutrinos, 1% as radiation) diffuses through space, creating gravitational fields with

profiles. The

term dominates at large radii, producing flat rotation curves without requiring dark matter [

8]. This connects stellar astrophysics directly to galactic dynamics: every star acts as a source of neutrinos that diffuse outward, creating an extended gravitational field that explains observed rotation curves. The continuous injection of neutrinos from stellar processes maintains this diffuse energy field, providing a dynamical alternative to static dark matter halos.

Note : The energy flux

is proportional to the negative gradient of the energy density (Fick’s law:

). Combining this with the continuity equation yields the diffusion equation:

The steady-state solution for an isolated, continuous point source is:

This

energy density profile is not an assumption but a direct mathematical consequence of energy diffusion from a central source.

7.4. Cosmic Expansion vs. Acceleration

Within our energy-diffusion framework, neutrinos are not mere byproducts but active mediators of cosmic dynamics, playing distinct roles at different scales and epochs. Expansion is driven by bounce energy and ongoing stellar output, while acceleration emerges from a snowball effect: neutrino condensation in voids creates lower-potential regions, driving further expansion which enables more condensation. This positive feedback naturally produces late-time acceleration without requiring dark energy as a separate component.

7.5. Neutrino Production and Geometric Expansion: A Causal Sequence

The expansion mechanism in our framework follows a well-defined causal sequence that resolves any apparent causality concerns. As the primordial black hole’s gravitational field collapses during the bounce, the spacetime metric undergoes an abrupt change—akin to a compressed spring releasing its energy. This corresponds to what standard cosmology calls "primordial inflation," though in our paradigm it represents a metric relaxation rather than spatial expansion of pre-existing space.

As radiation expands and cools, it reaches temperatures conducive to particle-antiparticle pair production. Positron-electron pairs form, some annihilating immediately, others serving as resonance shells for proton-antiproton formation. During this period of intense pair production and annihilation, copious high-energy neutrinos are produced, carrying substantial momentum away from annihilation sites.

Neutrinos then condense when they encounter regions where their momentum is sufficient to modify the local metric—typically where gravitational fields are weak enough to permit such modification. The highest-energy neutrinos condense first, initiating expansion. Lower-energy neutrinos may wait for suitable conditions, which arise as expansion creates ever-weaker gravitational regions. This staged condensation explains both initial expansion and late-time acceleration through a single unified mechanism.

The process is self-regulating: expansion creates lower-gravity regions → more neutrinos can condense → further expansion → creation of even lower-gravity regions. This positive feedback continues until the supply of neutrinos with enough energy is exhausted, after which gravitational attraction gradually reasserts dominance, beginning the contraction phase of the next cycle.

Most importantly, there is no causality violation in this sequence. The initial metric change enables neutrino production, whose condensation then drives sustained expansion. The highest-energy neutrinos produced early begin condensing almost immediately, while lower-energy ones await favorable conditions created by the expansion they help drive. This creates a coherent causal chain from bounce to expansion to acceleration.

7.6. Distinct Roles of Neutrinos Across Cosmic Evolution

Within our energy-diffusion framework, neutrinos emerge not as passive byproducts but as active mediators of cosmic dynamics, playing three distinct yet interconnected roles that span the entire cosmic cycle.

Bounce neutrinos are generated during the cascade evaporation of exotic matter. These high-energy neutrinos carry a significant fraction of the bounce energy and drive the initial expansion phase of each cycle. Their energy distribution reflects the layered structure of the disintegrating exotic matter.

Stellar neutrinos are continuously produced by nuclear fusion in stars. These neutrinos diffuse through galactic environments, creating the

gravitational fields that explain flat rotation curves without dark matter [

8]. Unlike bounce neutrinos which represent a one-time injection, stellar neutrinos provide continuous energy input that maintains galactic dynamics over cosmic timescales. Supernova neutrinos represent a particularly energetic subset, with implications for both stellar explosions and cosmic expansion as discussed in

Section 3.6.

Condensing neutrinos accumulate in cosmic voids where they undergo phase transitions that lower the local gravitational potential. This creates a positive feedback loop: expansion enables more condensation, which drives further expansion. This snowball effect naturally produces the observed late-time acceleration without requiring dark energy as a separate component. The condensation process is selective—only neutrinos with appropriate energy and encountering suitable conditions can condense, explaining why acceleration began relatively recently in cosmic history.

This tripartite classification resolves what might otherwise appear as an over-reliance on a single particle type. Instead, it reflects how the same fundamental particle can mediate different physical processes at different scales and epochs, much as photons mediate both atomic transitions and cosmic background radiation. The specific role a neutrino plays depends on its origin (bounce, stellar, or previous condensation), its energy, and the local conditions it encounters.

8. Conclusion: A Coherent Cyclical Cosmology

We have presented a physically concrete bounce mechanism based on the hierarchical structure of matter from nuclear to cosmic scales. The model demonstrates several profound insights that collectively address major challenges in contemporary cosmology.

Matter exhibits hierarchical layered structure across all scales, from 18-level nucleons in Lockyer’s model to cosmic-scale exotic matter organized by gravitational pressure. This structural continuity suggests a universal organizational principle operating from quantum to cosmological domains. Exotic matter behaves as a pressure-temperature sponge whose layer count increases with gravitational confinement, storing energy proportionally to external compression until reaching stability limits.

Gravitational contraction organizes rather than randomizes matter, decreasing entropy as matter progresses from dispersed states to neutron stars to structured exotic matter in black holes. This reverses the standard thermodynamic narrative and resolves the entropy paradox of initial conditions. Black holes are not singularities but physical repositories containing radially organized exotic matter, with layer density increasing toward the core and encoding information about their formation history.

Primordial black hole formation occurs through hierarchical mergers over cosmic time, with stellar and supermassive black holes coalescing to eventually form a single massive primordial black hole whose energy exceeds the threshold for bounce initiation. The bounce itself is a dynamical instability cascade where localized pressure reduction triggers exotic matter → energy conversion, reducing gravitational support and initiating runaway evaporation. This mechanism ensures a complete transition between cycles without mathematical singularities.

Cyclical evolution naturally resolves classical cosmological puzzles—entropy, flatness, horizon, monopole, size/age problems—without fine-tuning or dark components, while also addressing modern tensions like and through regionally variable expansion driven by differential neutrino condensation. The framework accommodates JWST observations of surprisingly mature high-redshift galaxies through potential multiverse structure where different regions undergo bounces asynchronously.

The framework’s explanatory power extends beyond cosmology to stellar astrophysics, naturally solving the core-collapse supernova energy problem through the same exotic matter formation and destabilization mechanism. This cross-scale applicability—from stellar explosions to cosmic bounces—demonstrates the unifying potential of viewing matter as hierarchically organized wave structures whose properties change under extreme pressure.

This model replaces mathematical singularities with physical processes, dark components with understood mechanisms derived from first principles, and offers testable predictions across multiple observational channels including CMB anomalies, gravitational wave backgrounds, neutrino astronomy, supernova signatures, and large-scale structure correlations. The dynamical cascade mechanism provides a particularly elegant solution: once started, it must complete, ensuring a clean transition between cycles while preserving information in the layered structure of exotic matter.

Most importantly, the work demonstrates the fertility of viewing matter as wave structures in a dynamic spatial medium—a perspective that unifies phenomena from particle masses to cosmic evolution while remaining grounded in empirical success (Lockyer’s predictive model) and physical intuition (sponge-like behavior, domino effects, harmonic organization). By taking seriously the numerical precision of Lockyer’s proton model as a clue to deeper structural principles, we have developed a framework that bridges particle physics and cosmology through a single, coherent narrative offering solutions to problems that have resisted resolution within standard paradigms.

Future work should focus on quantitative predictions of specific observational signatures: detailed calculations of CMB non-Gaussianity patterns from anisotropic bounce evaporation, precise spectral shapes for the stochastic gravitational wave background from multiple bounce events, quantitative models of regional expansion rate variations that could explain the Hubble tension, and specific predictions for supernova neutrino spectra based on exotic matter disintegration. Additionally, the mathematical formalism describing the quantization of exotic matter layers ( structure) requires development to make specific predictions about black hole evaporation timescales and merger signatures.

Appendix A. Hadronization and Nucleosynthesis in the Bounce Framework

Appendix A.1. Temperature Constraints from Lockyer’s Proton Model

The remarkable numerical precision of Lockyer’s proton model—matching the proton-electron mass ratio to seven significant figures—suggests it captures fundamental truths about nucleon structure. As discussed in our previous work [

7], the model’s 18 energy levels find natural justification from thermodynamic considerations during hadronization.

During the bounce expansion phase, the universe passes through temperature ranges identical to those in standard Big Bang cosmology. The critical temperature for hadronization—the transition from quark-gluon plasma to hadrons—occurs at

MeV (

K), as confirmed by lattice QCD calculations and heavy-ion collision experiments.

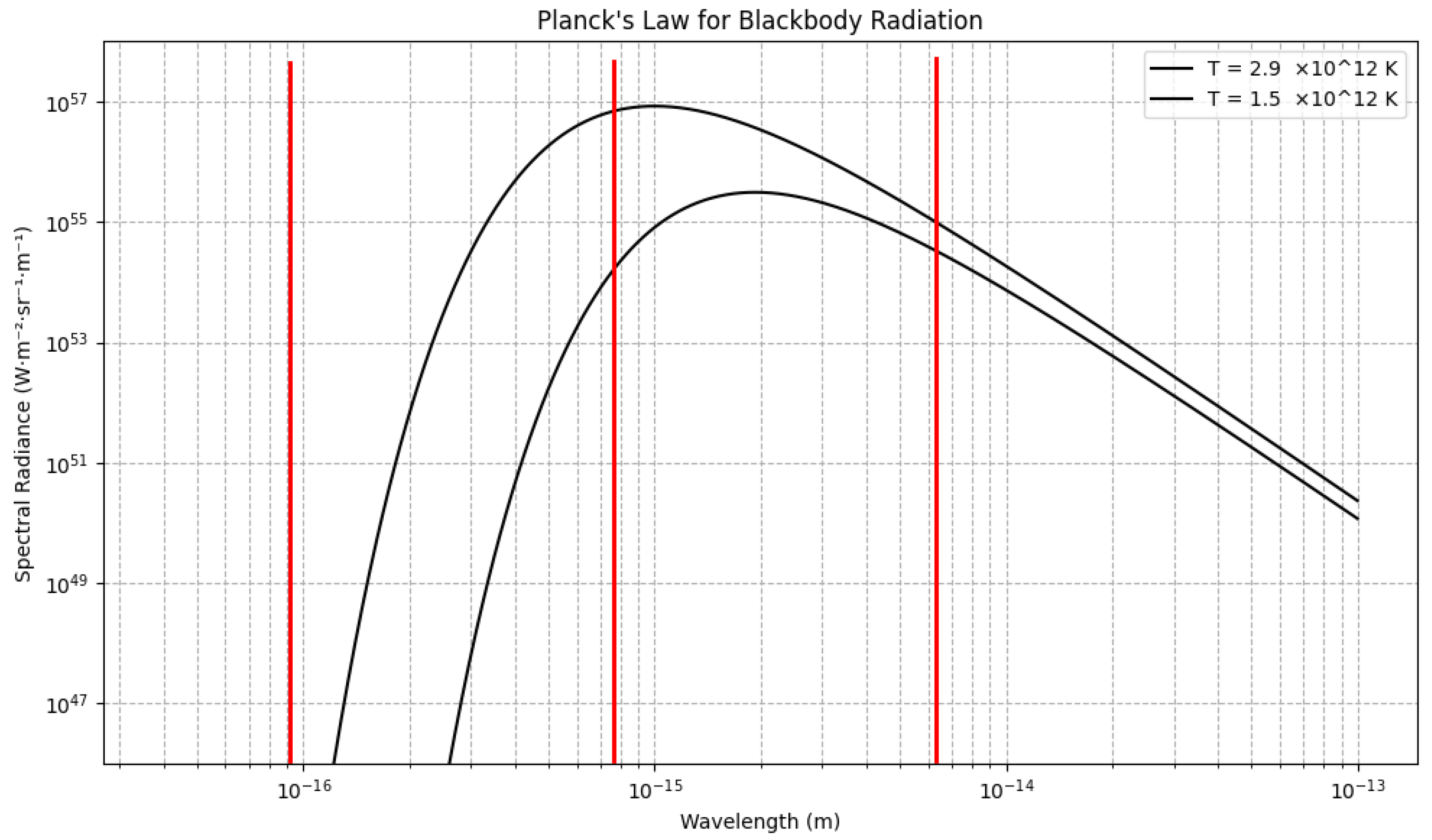

Figure A1.

Planck spectrum at high and low temperature estimates for the hadronization epoch. Vertical lines indicate the shortest wavelengths required for protons with 12, 18, and 24 energy levels in Lockyer’s model. The 18-level structure aligns precisely with the available thermal spectrum at hadronization temperatures.

Figure A1.

Planck spectrum at high and low temperature estimates for the hadronization epoch. Vertical lines indicate the shortest wavelengths required for protons with 12, 18, and 24 energy levels in Lockyer’s model. The 18-level structure aligns precisely with the available thermal spectrum at hadronization temperatures.

As shown in

Figure A1, the 18-level structure of Lockyer’s proton corresponds to wavelengths that fall within the thermal blackbody spectrum at hadronization temperatures. Structures with fewer levels (e.g., 12) would form earlier but be less stable, while structures with more levels (e.g., 24) require wavelengths outside the available thermal spectrum at these temperatures.

Appendix A.2. Implications for Primordial Nucleosynthesis

This temperature alignment ensures that nucleosynthesis proceeds exactly as in standard cosmology:

Deuterium formation: Begins at MeV ( K) when the photon-to-baryon ratio allows deuterium to survive photodisintegration

Helium-4 production: Peaks at MeV ( K), yielding the observed mass fraction

Lithium production: Occurs at slightly lower temperatures, though the "lithium problem" persists in both models

Freeze-out: Nuclear reactions cease at MeV ( K) as expansion dilutes particles below interaction thresholds

The identical temperature sequence ensures that light element abundances match observational constraints from:

Primordial deuterium measurements from quasar absorption systems

Helium-4 determinations from H II regions in metal-poor galaxies

Cosmic microwave background constraints on baryon density

Appendix A.3. Distinctive Feature: Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry Origin

While preserving standard nucleosynthesis predictions, our model provides a novel explanation for the matter-antimatter asymmetry. As discussed in

Section 5.3, the asymmetry emerges not from CP violation in particle decays but from structural differences in how electrons and positrons are incorporated into nucleons versus antinucleons during hadronization.

This structural explanation aligns with the temperature constraints: at K, both protons and antiprotons form, but their different internal arrangements (positron vs. electron cores) lead to slightly different interaction probabilities in the dense early environment. The resulting slight excess of matter over antimatter ( part in ) matches observations without requiring fine-tuned CP violation parameters.

Appendix A.4. Conclusion

The thermal history following our bounce mechanism reproduces all successful predictions of Big Bang nucleosynthesis while providing physical explanations for what remain puzzles in standard cosmology (matter-antimatter asymmetry, hadron stability). This demonstrates that our model can preserve empirical successes while offering conceptual improvements—exactly what one expects from a progressive research program.

Appendix B. Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays and Multiverse Boundaries

The observed flux of cosmic rays with energies above eV presents a significant challenge to standard astrophysics. The Hillas criterion indicates that accelerating particles to such energies requires extremely powerful sources with size R and magnetic field B satisfying , where is the shock velocity relative to light speed, and Z is the particle charge.

In our multiverse framework, particles accelerated during bounce events in neighboring regions could overcome these limitations:

Bounce events involve energy densities far exceeding any astrophysical process

The spatial scales involved (size of bounce regions) provide ample acceleration length

Magnetic fields could be amplified to extreme values during exotic matter disintegration

The probability of such particles reaching our region depends on the nature of boundaries between bounce regions. In our continuous medium model, boundaries are not sharp discontinuities but transition zones where physical properties change gradually. Particles could traverse these zones through:

Diffusion processes in the spatial medium

Tunneling through potential barriers

Following "bridges" formed during region formation

While quantitative calculations of transmission probabilities require developing the full mathematical formalism of multiverse boundaries, the qualitative picture provides a natural explanation for otherwise inexplicable ultra-high-energy events. This framework predicts that UHECR arrival directions might correlate with other multiverse signatures, such as CMB anomalies or regions showing unusual galaxy maturity in JWST observations, providing a potential multi-messenger test of the multiverse hypothesis.

Appendix C. Gravitational Potential Energy Calculation

Appendix C.1. Gravitational Potential Energy of the Observable Universe

Calculating the total gravitational potential energy of the universe is a complex problem in general relativity. The Newtonian formula for a homogeneous sphere, while approximate, provides a robust order-of-magnitude estimate and is commonly used in this pedagogical context [

9,

10].

The gravitational potential energy U for a homogeneous sphere of mass M and radius R is given by .

Appendix C.1.1. Mean Density of Baryonic Matter

The cosmological parameters from Planck 2018 [

1] are

We deduce

The critical density is

with

Thus, the mean baryonic density is

Appendix C.1.2. Gravitational Potential Energy of the Observable Universe

The radius of the observable universe is

The associated volume is

The total baryonic mass is

The total matter mass (baryons + dark matter,

) is

For a uniform sphere, the gravitational binding energy is

Appendix C.2. Energy Budget from Neutrino Production

If a fraction

f of the baryonic mass has been converted to neutrino energy since the last bounce, the available energy is:

With

kg (calculated above) and assuming

based on estimates of "missing" baryonic mass, we obtain:

This is comparable to the magnitude of the current gravitational potential energy J, suggesting neutrino production provides sufficient energy for the geometric reorganization driving expansion.

Appendix C.3. Interpretation of the Energy Budget Correspondence

The calculated values J and J (from subsequent calculations) differ by a factor of approximately 3.2. While this might appear as a discrepancy at first glance, several important considerations contextualize this result within the uncertainties inherent to cosmological calculations.

The homogeneous sphere model represents a significant simplification of actual mass distribution in the universe. Uncertainties in the fundamental parameters and each contribute uncertainties of order 1-2%. The simplified treatment of neutrino energy production efficiency and the assumption of perfect energy conversion from mass to gravitational work both introduce additional uncertainties. Collectively, these factors could easily account for a factor of 2-3 difference in order-of-magnitude estimates.

Not all thermal energy produced in the early universe contributes directly to gravitational potential energy. Some fraction remains as kinetic energy of particles, some is lost through inefficiencies in energy transfer processes, and some contributes to other forms of potential energy (nuclear, electromagnetic). The energies are also calculated at different cosmological epochs and would require careful redshifting and time evolution for precise comparison.

Despite these uncertainties, the fundamental observation remains significant: neutrino energy calculations produces energies of precisely the order of magnitude required to explain cosmic expansion ( J). This represents the only known physical mechanism capable of supplying the necessary energy on cosmological scales without invoking unexplained dark components. The correspondence, even allowing for substantial uncertainty factors, points toward neutrinos as the primary energy source for gravitational work in the universe—a conclusion that aligns with and supports the broader theoretical framework developed in this paper.

Summary

Appendix C.4. Total Primordial Thermal Energy Release

The primordial thermal energy is calculated from current observables of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and Cosmic Neutrino Background (C

B), correcting their current energy by the redshift factor

to estimate their energy at the time of emission/decoupling [

13,

14].

Appendix C.4.1. Energy from the Cosmic Microwave Background (Photons)

At the redshift of photon decoupling (

[

17]), their energy was higher by a factor of

.

Appendix C.4.2. Energy from the Cosmic Neutrino Background (Neutrinos)

After neutrino decoupling, their temperature was reduced by a factor of

compared to photons [

16].

Appendix C.4.3. Total Initial Thermal Energy

Appendix C.5. Note on Subsequent Stellar Energy Production

The total energy radiated by all stars in the universe is estimated from the energy density of the extragalactic background light (EBL) [

15].

Even when corrected for redshift (factor of

), this energy (

) is

three orders of magnitude smaller than the primordial thermal energy and is therefore negligible in this cosmological energy budget.

Appendix C.6. Implications

The total gravitational potential energy ( J) and the initial thermal energy from annihilation ( J) are both on the order of J.

The factor of difference is well within the uncertainty of such cosmological order-of-magnitude estimates, which involve simplifications like the homogeneous sphere model and average redshift factors. This remarkable proximity suggests a profound connection: the expansion of the universe, and the gravitational potential energy stored therein, was primarily funded by the initial release of thermal energy from particle processes in the hot Big Bang, notably matter-antimatter annihilation. The energy from all stellar and astrophysical processes that followed is negligible in comparison, highlighting the dominance of primordial physics in setting the large-scale energy budget of the cosmos.

It is critical to address an apparent paradox: this calculation utilizes the CDM parameter , which includes dark matter, to estimate the total gravitational energy . However, the model presented in this paper explicitly rejects dark matter as a substance.

This approach is justified because the parameter observationally constrains the total gravitational mass-energy content of the universe, regardless of its nature. In the standard paradigm, this content is interpreted as cold dark matter particles. In our paradigm, the same gravitational effect is attributed to the energy density field sourced by historical and ongoing mass-energy conversion and its diffusion.

Therefore, using the CDM value is not an endorsement of the dark matter hypothesis but a pragmatic method to quantify the total energy budget that any alternative theory, including ours, must explain. The remarkable agreement between and suggests that the energy released from particle reactions in the early universe is sufficient to fund this required gravitational energy, providing a physical origin for what CDM attributes to dark matter.

Appendix Note on Cosmological Assumptions

Whether the initial conditions were set by a standard Hot Big Bang or an alternative scenario such as a Big Bounce, the subsequent processes of energy injection and diffusion that govern our model remain valid.

The precise interpretation may depend on the cosmological model. The primary goal of this paper is not to debate initial conditions but to introduce a unified mechanism for dark matter and dark energy phenomena on galactic and intergalactic scales, based on observable, ongoing physical processes, chief among them diffusion.

A detailed exploration of how this mechanism integrates with specific cosmological models, including bouncing scenarios, is a fertile ground for future work.

References

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters

. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2018, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Novello, M.; Bergliaffa, S. E. P. Bouncing Cosmologies

. Physics Reports 2008, 463, 127–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P. J.; Turok, N. A Cyclic Model of the Universe

. Science 2002, 296, 1436–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The Vibrational Fabric of Spacetime: A Model for the Emergence of Mass, Inertia, and Quantum Non-Locality 2025. [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. Velocity as a Geometric Deformation State: Complete Demonstration within the Spatial Absolute Reference Frame 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, T. N. Vector Particle Physics; TNL Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Furne Gouveia, G. A Photon-Based Vector Particle Model for Proton and Neutron Masses

. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. The Role of Energy Density Diffusion in Galactic Dynamics and Cosmic Expansion: A Unified Theory for MOND and Dark Energy 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A. C. Observational Evidence of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback

. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2012, 50, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstock, F. I. The Energy of the Universe

. In General Relativity and Gravitational Physics; World Scientific, 1996; pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants. CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Conselice, C. J.; Wilkinson, A. The Observable Universe

. In Cosmology and Extragalactic Astronomy; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. Cosmology; Oxford University Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-19-852682-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, E. W.; Turner, M. S. The Early Universe; Addison-Wesley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, E.; Krennrich, F. The extragalactic background light and the gamma-ray opacity of the universe. Astroparticle Physics 2013, 43, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, B. D. The primordial lithium problem. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2011, 61, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 594, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Furne Gouveia, G. A Generalized Contraction Framework for the Michelson-Morley Null Result in a Medium-Based Theory

. Preprints 2025, 2025092283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).