Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivations

- a)

- The strength balance of the RC MRF and SDCs is a point of interest for seismic design. How will the behavior of such a structure under earthquake sequences change as the strength balance of the RC MRF and SDCs changes?

- b)

- How is the hysteretic dissipated energy of a damaged RC MRF with SDCs different from that of a non-damaged RC MRF with SDCs? When the pinching behavior of RC beam is notable, the hysteretic dissipated energy of RC members deteriorates significantly. Because the behavior of SDC is influenced by the surrounding RC beams, the hysteretic dissipated energy of an SDC depends on the behavior of surrounding RC beams. How will the hysteretic dissipated energy of SDCs change owing to the prior damage to surrounding RC beams?

- c)

- The natural period of a damaged RC MRF is longer than that of a non-damaged RC MRF (e.g., Di Sarno and Amiric, 2019). How will the increase in the natural period of a damaged RC MRF with SDCs change as the strength balance of this structure changes? How will the pinching behavior of RC beam affect the increase in the natural period of a damaged RC MRF with SDCs?

1.2. Objectives

- Considering the case when the pulse velocity of each MI is the same, how will the peak displacement of an RC MRF with SDCs subjected to two MIs differ from that for a single MI? How will the peak displacement of an RC MRF with SDCs subjected to two MIs be influenced by the pinching behavior of RC beams and the strength balance of the RC MRF and SDCs?

- How will the hysteretic dissipated energy of RC members of a damaged RC MRF with SDCs differ from that of a non-damaged structure, and how will the hysteretic dissipated energy of SDCs of a damaged RC MRF differ from that of a non-damaged structure?

- How will the increase in the response period of an RC MRF with SDCs be influenced by the pinching of RC beams and the strength balance of the RC MRF and SDCs?

- 1.

- Which combination of the two pulse periods produces the severest response in a given RC MRF model?

- 4.

- Considering the envelope of NTHA results and all combinations of pulse periods while the peak velocities of the first and second pulses are kept constant, can the results of the extended ICPMIA approximate the NTHA envelope?

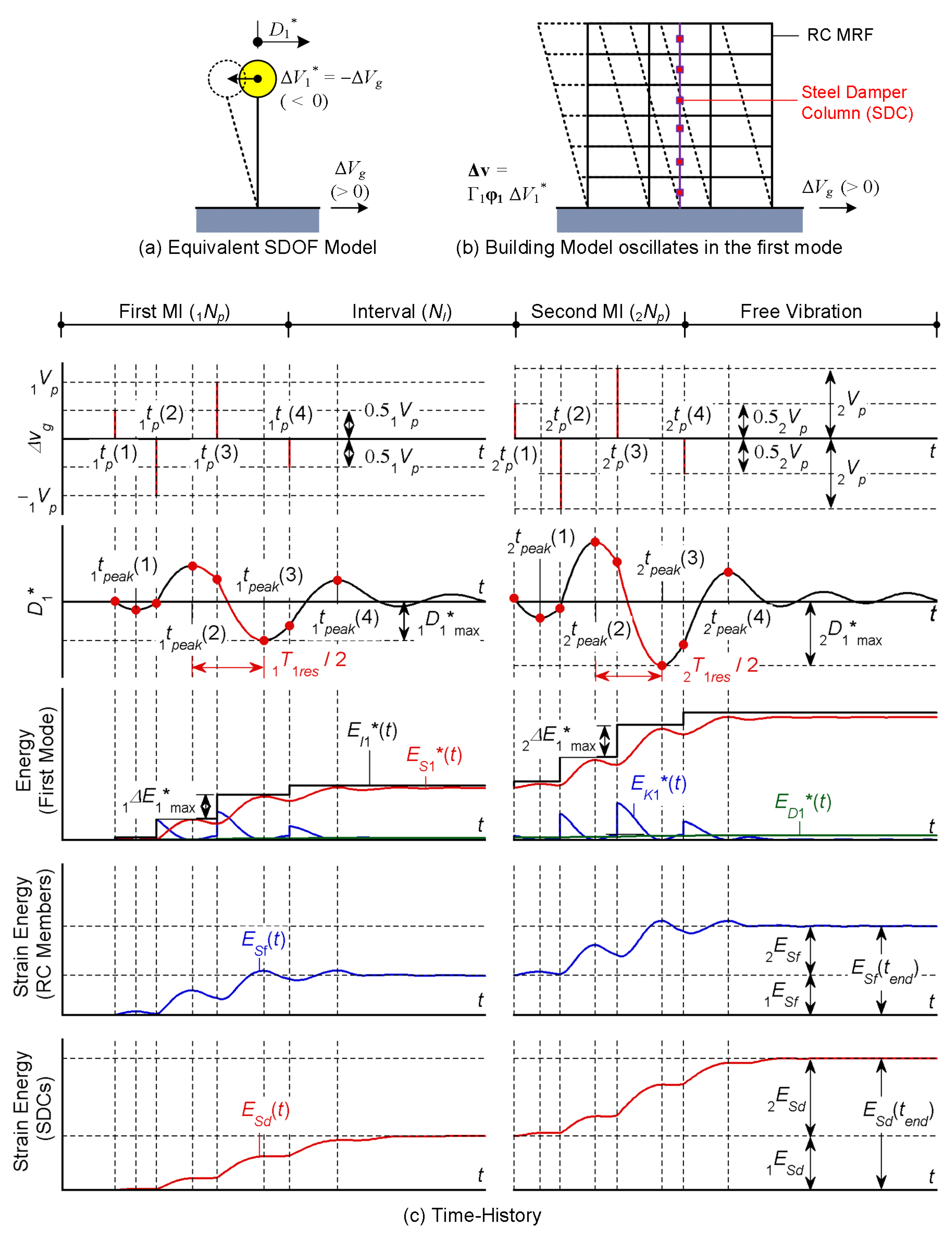

2. Outline of the Extended ICPMIA

2.1. Extended Critical PMI Analysis

2.2. Procedure for the Extended ICPMIA

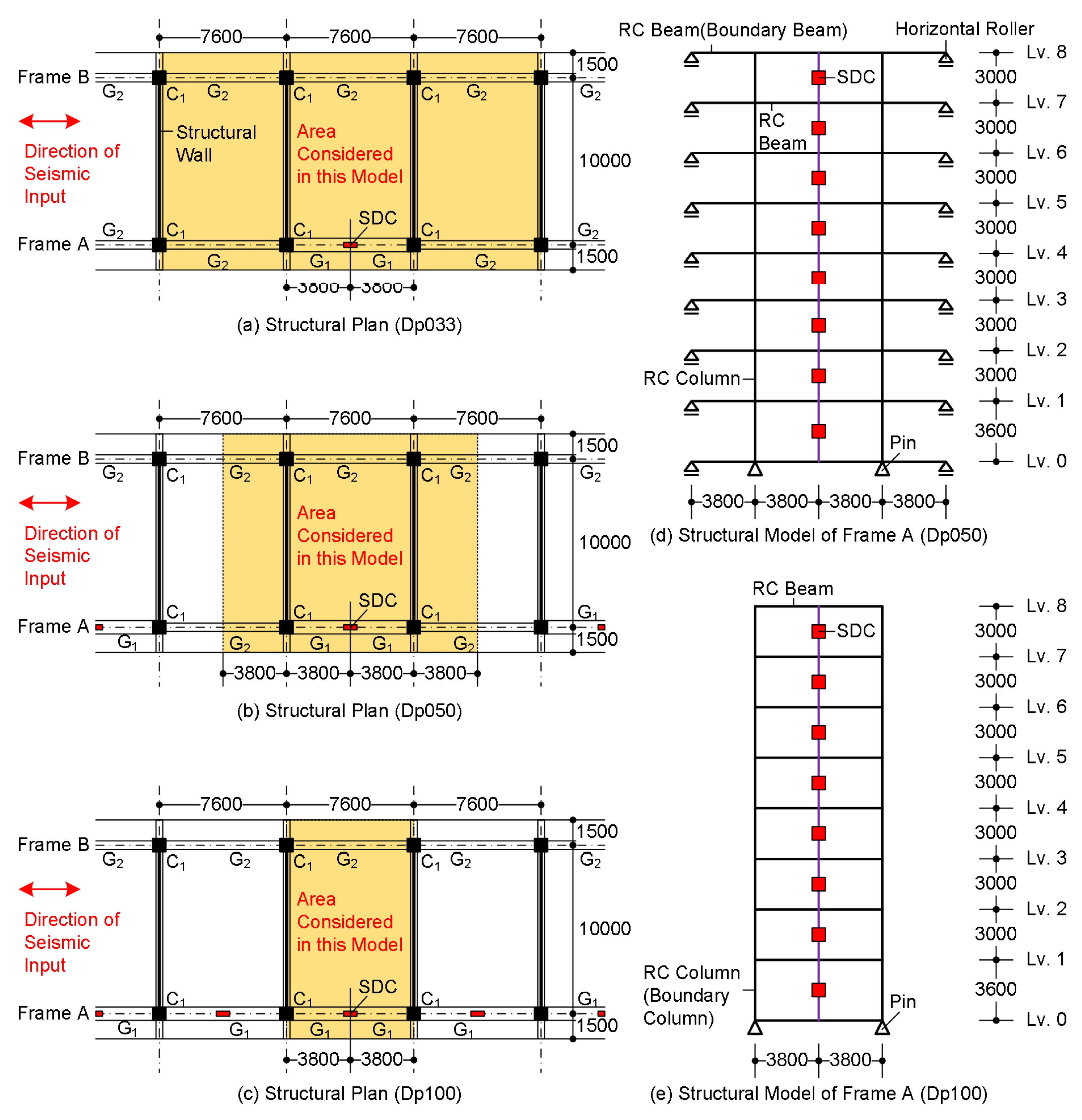

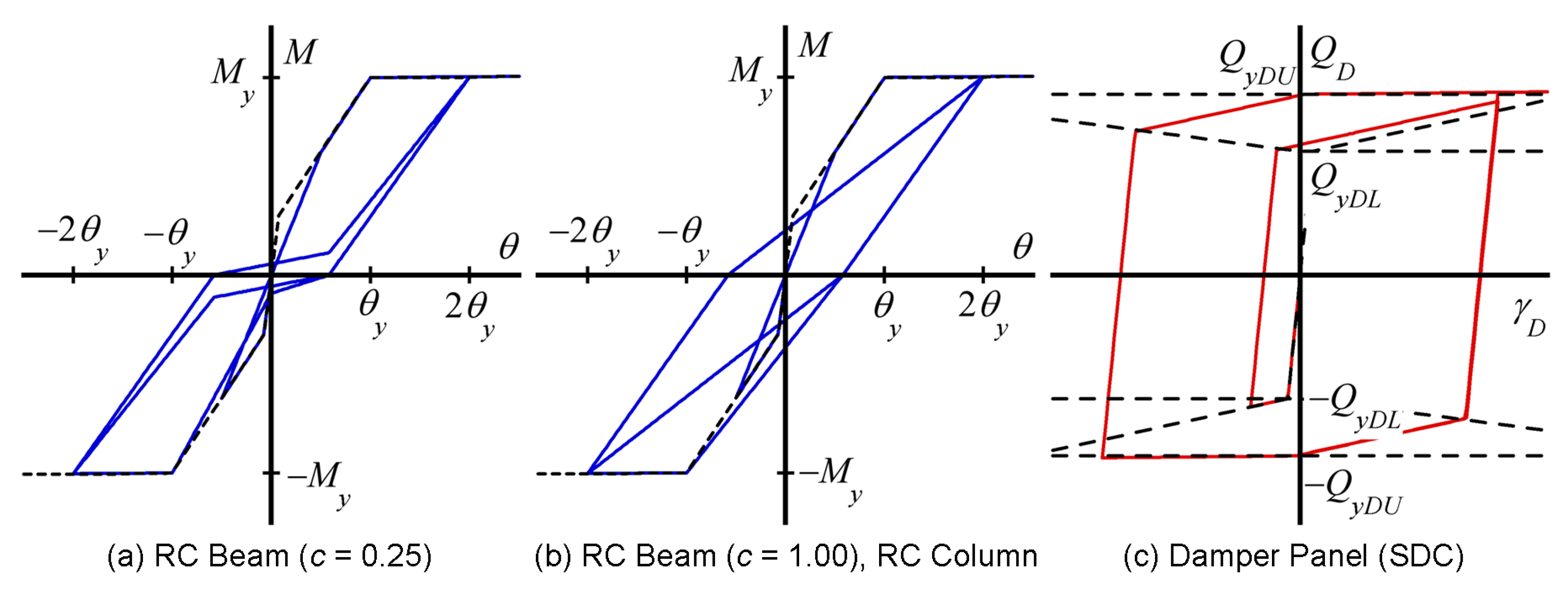

3. Building Model

4. ICPMIA of the Building Model

4.1. Analysis Method

4.2. Analysis Results

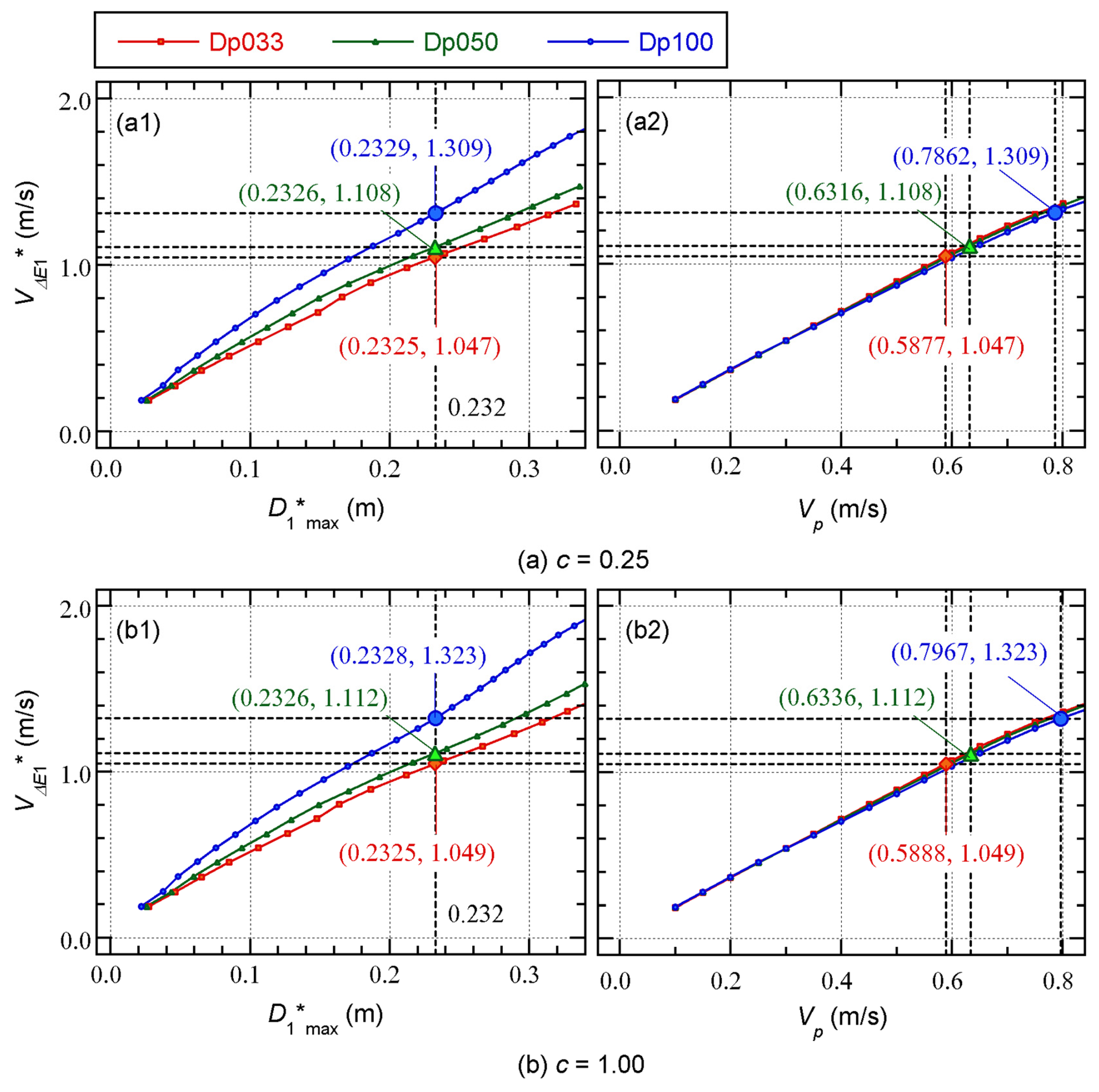

4.2.1. Single MI

- For = 0.25 (significant pinching), the velocities in Dp033 corresponding to were = 1.047 m/s and = 0.5877 m/s. Similarly, those in Dp050 were = 1.108 m/s and = 0.6316 m/s, while those in Dp100 were = 1.309 m/s and = 0.7862 m/s.

- For = 1.00 (no pinching), the velocities and in all three models corresponding to were slightly higher than for = 0.25. That is, those velocities in model Dp033 were = 1.049 m/s and = 0.5888 m/s. Similarly, those velocities in Dp050 corresponding to were = 1.112 m/s and = 0.6336 m/s, while those in Dp100 were = 1.323 m/s and = 0.7967 m/s.

4.2.2. Sequential MIs (2Vp = 1Vp)

- In models Dp033 and Dp050 ( = 0.25), for Sequential-1 was larger than that for a single MI, while in the other models, for Sequential-1 was almost the same as for the single MI. However, for Sequential-2 was larger than that for a single MI in all models.

- The values of Sequential-1 and 2 were larger than those of the single MI in all models. The difference between the values of Sequential-1 and 2 was negligible.

- The equivalent velocity of the maximum momentary input energy in the second MI () is close to that in the first MI (). The value of in Sequential-2 is almost identical to that in Sequential-1.

- For Sequential-1 (Figure 6(a2,b2)), the direction of the half cycle of the structural response when occurs in the second MI is opposite to that when occurs. In model Dp033 ( = 0.25), is larger than , whereas in model Dp100 ( = 0.25), is smaller than .

- For Sequential-2 (Figure 6(a3,b3)), the direction of the half cycle of the structural response when occurs in the second MI is the same as when occurs. In both models Dp033 and Dp100 ( = 0.25), is larger than .

- In both models Dp033 and Dp100 ( = 0.25), at time is close to the origin. In model Dp033 ( = 0.25), at time is also close to the origin in both Sequential-1 and 2. In model Dp100 ( = 0.25), a non-zero at time is observed in Sequential-1, although at time is also close to the origin in Sequential-2.

2.4.3. Sequential MIs (2Vp ≠ 1Vp)

- The – curve of Sequential-2 is below the – curve of Sequential-1: for similar values of , for Sequential-2 is smaller than for Sequential-1.

- For = , the values of Sequential-1 and 2 are almost identical and are close to for a single MI (= ). However, the relationships between the values of Sequential-1 and 2 and for a single MI (= ) depend on the model. In Sequential-2, is larger than in all models. In Sequential-1, the relationship between and depends on the model: is smaller than in models Dp050 ( = 1.00) and Dp100 (Figure 7c,e,f).

- The difference between the – curve of Sequential-1 and the curves of Sequential-2 is limited in all models: for similar values of , for Sequential-2 is close to that for Sequential-1.

- For similar values of , the response period of the first mode in the second MI () is longer than that in a single MI () in all models. For Dp030 and Dp050 ( = 0.25), is longer than the response period of the first mode in the second MI (), regardless of the value of .

- The – curve of Sequential-2 is below the – curve of a single MI in all models: for similar values of , for Sequential-2 is lower than for a single MI. However, the relationship between the – curve of Sequential-1 and the – curve of a single MI depends on the model: in general, for similar values of , for Sequential-1 is also lower than for a single MI.

- The – curve of Sequential-2 is below the – curve of a single MI in all models: for similar values of , for Sequential-2 is lower than for a single MI. However, the relationship between the – curve of Sequential-1 and the – curve of a single MI depends on the model: for similar values of , for Sequential-1 may be higher than for a single MI.

2.5. Summary of Results and Discussion

- The influence of the signs of the two MIs on the peak response ( and ) was notable. The peak response during the second MI was larger than that during the first MI, when the signs of the first and second MI were the same.

- The influence of the signs of both MIs on the cumulative response () was negligible.

- When the significant pinching behavior of RC beams was considered, and the strength of the SDCs was relatively low, the increases in and the natural period () in the sequential MIs for a single MI were also notable. Meanwhile, the increases in and were limited when no beam pinching behavior was considered and the SDC strength was relatively high.

- For similar values of , the cumulative strain energies of RC members and SDCs dissipated during the second MI per unit mass ( and , respectively) were lower than those for a single MI when the signs of the first and second MIs were the same. For = , was lower than while was higher than . These trends were pronounced when the significant pinching behavior of RC beam was considered.

3. Responses of Building Models under Sequential Pulse-like Ground Motions

3.1. Analysis Method

3.1.1. Pulse-like Ground Motion Models

3.1.2. Analysis Procedure

- 1.

- The pulse period () was increased from 0.5 s to 2.5 s in increments of 0.1 s.

- 5.

- The peak equivalent displacement of the first modal response () was calculated from the NTHA results, according to the procedure presented in a previous study (Fujii, 2022).

- 6.

- The largest was found along with the corresponding (= ).

- The pulse period of the first input () was fixed as the value obtained from the single-pulse model, while that of the second input () was increased from 0.5 s to 2.5 s in increments of 0.1 s.

- The value of was calculated from the NTHA results.

- The largest was found along with the corresponding (= ).

3.2. Analysis Results

3.2.1. Single-Pulse Model

- The values obtained from PMI agree well with the envelopes of the NTHA results, although slight underestimations are observed in the upper (sixth and seventh) stories.

- The values obtained from PMI are close to the NTHA envelopes.

- The largest value obtained from Single-Pulse-000 is slightly larger than that from Single-Pulse-090. Meanwhile, the values of obtained from Single-Pulse-000 and 090 are different. As shown in Figure 13a (model Dp033, = 0.25), the largest obtained from Single Pulse-000 is 0.2292 m, while that from Single Pulse-090 is 0.2136 m. In addition, the value of obtained from Single-Pulse-000 is 1.1 s, while that from Single-Pulse-090 is 1.2 s.

- The largest value obtained from NTHA is close to from ICPMIA.

- The values of are slightly smaller than the values from ICPMIA. The range of for all models is 0.87 to 0.90.

3.2.2. Sequential-Pulse Model

- The values obtained from Extended PMI agree well with the NTHA envelopes for Dp050 and Dp100. However, for Dp033, the values from Extended PMI underestimate the NTHA envelope.

- The values obtained from Extended PMI are close to the NTHA envelopes.

- The largest values obtained from NTHA are close to from extended ICPMIA. The largest value from Sequence-Pulse-000 is larger than from extended ICPMIA for all models. Meanwhile, the largest from Sequence Pulse-090 is smaller than from extended ICPMIA.

- The value of obtained from the sequential-pulse model is larger than from the single-pulse model. For model Dp033 ( = 0.25) in Figure 15a, the ratio is 1.5/1.1 = 1.36 for Sequential-Pulse-000, while is 1.7/1.2 = 1.42 for Sequential-Pulse-090. Meanwhile, for model Dp100 ( = 0.25) in Figure 15c, the ratios for Sequential-Pulse-000 and 090 are 1.2/1.0 = 1.20 and 1.1/0.9 = 1.22, respectively.

- The values of are close to from extended ICPMIA.

3.3. Discussion

- The ICPMIA results provide accurate approximations of the most critical local response (peak story drift and normalized cumulative strain energy of SDC damper panels) for the single-pulse models. In addition, the extended ICPMIA results accurately approximate the most critical local response for the sequential-pulse models.

- For a sequential-pulse model, the pulse-period condition < produces the most critical response for a given RC MRF model. In other words, repeating the same pulse model with the same pulse period ( = = ) will not produce the most critical response for the sequential pulsive input.

4. Conclusions

- I)

- When the pulse velocities of the two MIs are the same in the sequential MIs, the equivalent velocities of the maximum momentary input energy of the first modal response () in both MIs are similar. The peak equivalent displacement () of an RC MRF with SDCs in sequential MIs is larger than that for a single MI when the signs of the first and second MIs are the same. This trend is notable when the SDC strength is relatively low, and the pinching behavior of RC beam is significant.

- II)

- For similar values of , the cumulative strain energy of RC members during the second MI in the sequential MIs is smaller than that for a single MI. This trend is notable when the pinching behavior of RC beam is significant. Meanwhile, the cumulative strain energy of SDCs during the second of the sequential MIs is smaller than that for a single MI when the signs of the first and second MIs are the same.

- III)

- For similar values of , the response period of the first mode in the second MI () is longer than that for a single MI. This trend is notable when the SDC strength is relatively lower, and the pinching behavior of RC beam is significant.

- I)

- In the NTHA results for sequential pulse-like ground motion, the most critical period of the second input () is longer than that of a single input ().

- II)

- The most critical response obtained from NTHA using sequential pulses can be approximated by the extended ICPMIA results.

- One of the most important issues in the seismic design of an RC MRF with SDCs is evaluating the damage to RC members and SDCs. Because the damper panel in SDC is made of low-yield-strength steel, its damage evaluation may be based on the peak shear strain and the cumulative strain energy. If the proper relationship between the ultimate peak shear strain (or strain amplitude) and cumulative strain energy at failure of the damper panel is known, then it is possible to evaluate the limit of the story drift of an RC MRF when the damper panel reaches the failure. What will the story drift limit be? Will it be larger than the story drift considered in the design of an RC MRF with SDCs (e.g., 2%)? How will the number of impulsive inputs () influence the story drift limit?

- One of our previous studies (Fujii and Shioda, 2023) proposed a simplified procedure to predict the peak and cumulative responses of an RC MRF with SDCs. Because this simplified procedure is based on nonlinear static (pushover) analysis, it is much easier to apply in daily design work. However, to extend this simplified procedure to the case of an earthquake sequence, it is necessary to evaluate the − and − (or − ) relationships of RC MRFs. How can and be formulated considering the previous response of the RC MRF?

Data Availability Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Abdelnaby, A.E. Fragility curves for RC frames subjected to Tohoku mainshock-aftershocks sequences. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. 2016, 22, 902–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaby, A.E.; Elnashai, A.S. Performance of degrading reinforced concrete frame systems under the Tohoku and Christchurch earthquake sequences. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. 2014, 18, 1009–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehashi, H.; Takewaki, I. Pseudo-double impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic MDOF model under near-fault earthquake ground motion. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 2021, 150, 106887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehashi, H.; Takewaki, I. Pseudo-multi impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic high-rise buildings under long-duration, long-period ground motion. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings. 2022, 31, e1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehashi, H.; Takewaki, I. Bounding of earthquake response via critical double impulse for efficient optimal design of viscous dampers for elastic-plastic moment frames. Japan Architectural Review. 2022, 5, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H. (1985). Earthquake resistant limit-state design for buildings. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Akiyama, H. (1999). Earthquake-resistant design method for buildings based on energy balance. Tokyo: Gihodo Shuppan.

- Alıcı, F.S.; Sucuoğlu, H. (2024). “Input energy from mainshock-aftershock sequence during February 6, 2023 Earthquakes in South East Türkiye”, in Proceedings of the 18th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Milan, Italy.

- Alavi, B.; Krawinkler, H. (2000). “Consideration of near-fault ground motion effect in seismic design”, in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Alavi, B.; Krawinkler, H. Behavior of moment-resisting frame structures subjected to near-fault ground motions. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 2004, 33, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadio, C.; Fragiacomo, M.; Rajgelj, S. The effects of repeated earthquake ground motions on the non-linear response of SDOF system. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 2003, 32, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavent-Climent, A.; Mollaioli, F. (eds) (2021). Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2021. Cham: Springer.

- Dindar, A.A.; Benavent-Climent, A.; Mollaioli, F.; Varum, H. (eds) (2025). Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2025. Cham: Springer.

- Di Sarno, L. Effects of multiple earthquakes on inelastic structural response. Engineering Structures. 2013, 56, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, L.; Amiri, S. Period elongation of deteriorating structures under mainshock-aftershock sequences. Engineering Structures. 2019, 196, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaire-Ávila, J.; Galé-Lamuela, D.; Benavent-Climent, A.; Mollaioli, F. (2024). “Cumulative damage in buildings designed with energy and force methods under sequences of earthquakes”, in Proceedings of the 18th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Milan, Italy.

- Fujii, K. Peak and cumulative response of reinforced concrete frames with steel damper columns under seismic sequences. Buildings. 2022, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. Critical pseudo-double impulse analysis evaluating seismic energy input to reinforced concrete buildings with steel damper columns. Frontiers in Built Environment. 2024, 10, 1369589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. Seismic capacity evaluation of reinforced concrete buildings with steel damper columns using incremental pseudo-multi impulse analysis. Frontiers in Built Environment. 2024, 10, 1431000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. Seismic response of reinforced concrete moment-resisting frame with steel damper columns under earthquake sequences: evaluation using extended critical pseudo-multi impulse analysis. Frontiers in Built Environment. 2025, 11, 1561534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. (2025), “Choice of the number of impulsive Inputs in the ICPMIA as a substitute for near-fault seismic input to RC MRFs, “in Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2025, Istanbul, Türkiye.

- Fujii, K.; Kanno, H.; Nishida, T. Formulation of the time-varying function of momentary energy input to a single-degree-of-freedom system using Fourier series. Journal of Japan Association for Earthquake Engineering. 2021, 21, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Shioda, M. Energy-based prediction of the peak and cumulative response of a reinforced concrete building with steel damper columns. Buildings. 2023, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galé-Lamuela, D.; Donaire-Ávila, J.; Benavent-Climent, A.; Mollaioli, F. (2025). “Damage Distribution in Buildings Under Sequences of Earthquakes, “in Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2025, Istanbul, Türkiye.

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D. Behavior factors for nonlinear structures subjected to multiple near-fault earthquakes. Computers and Structures. 2010, 88, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D. Ductility demand spectra for multiple near-and far-fault earthquakes. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 2010, 30, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Beskos, D.E. Inelastic displacement ratios for SDOF structures subjected to repeated earthquakes. Engineering Structures. 2009, 31, 2744–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Liolios, A.A. Nonlinear behaviour of RC frames under repeated strong ground motions. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 2010, 30, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, N.; Inoue, N. Damaging properties of ground motion and prediction of maximum response of structures based on momentary energy input. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 2002, 31, 1657–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T.; Ito, S.; Kamura, H.; Ueki, T.; Okamoto, H. (2000). “Experimental study on hysteretic damper with low yield strength steel under dynamic loading,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Kojima, K.; Takewaki, I. (2015a). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 1: Fling-step input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 12.

- Kojima, K.; Takewaki, I. (2015b). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 2: Forward-directivity input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 13.

- Kojima, K.; Takewaki, I. (2015c). Critical input and response of elastic–plastic structures under long-duration earthquake ground motions. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 15.

- Mahin, A. (1980). “Effect of duration and aftershock on inelastic design earthquakes,” in Proceedings of the 9th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Mavroeidis, G.P.; Papageorgiou, A.S. A Mathematical Representation of Near-Fault Ground Motions. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 2003, 93, 1099–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidis, G.P.; Dong, G.; Papageorgiou, A.S. Near-fault ground motions, and the response of elastic and inelastic single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) systems. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 2004, 33, 1023–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, K.; Hisada, T.; Tsugawa, T.; Bessho, S. (1974). “Earthquake resistant design of a 20 story reinforced concrete buildings” in Proceedings of the fifth world conference on earthquake engineering, Rome, Italy.

- Ono, Y.; Kaneko, H. (2001). “Constitutive rules of the steel damper and source code for the analysis program,” in Proceedings of the Passive Control Symposium 2001, Yokohama, Japan (In Japanese).

- Otani, S. Hysteresis models of reinforced concrete for earthquake response analysis. Journal of the Faculty of Engineering the University of Tokyo. 1981, 36, 125–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-García, J.; Negrete-Manriquez, J.C. Evaluation of drift demands in existing steel frames under as-recorded far-field and near-fault mainshock–aftershock seismic sequences. Engineering Structures 2011, 33, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, J. Mainshock-Aftershock Ground Motion Features and Their Influence in Building’s Seismic Response. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. 2012, 16, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, J. (2013). “Three-dimensional building response under seismic sequences,” in Proceedings of the 2013 World Congress on Advances in Structural Engineering and Mechanics (ASEM13), Jeju, Korea.

- Takewaki, I. Review: Critical Excitation Problems for Elastic–Plastic Structures Under Simple Impulse Sequences. Japan Architectural Review. 2025, 8, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takewaki, I.; Kojima, K. (2021). An Impulse and Earthquake Energy Balance Approach in Nonlinear Structural Dynamics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Uang, C.; Bertero, V.V. Evaluation of seismic energy in structures. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 1990, 19, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varum, H.; Benavent-Climent, A.; Mollaioli, F. (eds) (2023). Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2023. Cham: Springer.

- Wada, A.; Huang, Y.; Iwata, M. Passive damping technology for buildings in Japan. Progress in Structural Engineering and Materials. 2000, 2, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Agrawal, A.K.; He, W.L.; Tan, P. Performance of passive energy dissipation systems during near-field ground motion type pulses. Engineering Structures 2007, 29, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaei-Sabegh, S. Time–frequency analysis of the 2012 double earthquakes records in North-West of Iran. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering. 2014, 12, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaei-Sabegh, S.; Ruiz-García, J. Nonlinear response analysis of SDOF systems subjected to doublet earthquake ground motions: A case study on 2012 Varzaghan–Ahar events. Engineering Structures. 2016, 110, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, G.; Ding, Y. Damage demands evaluation of reinforced concrete frame structure subjected to near-fault seismic sequences. Natural Hazards. 2019, 97, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Ji, D.; Wen, W.; Lei, W.; Xie, L.; Gong, M. The inelastic input energy spectra for main shock–aftershock sequences. Earthquake Spectra 2016, 32, 2149–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).