1. Introduction

“Science is a collaborative effort. The combined results of several people working together is often much more effective than an individual scientist working alone.”

Automating scientific discovery has evolved through technological epochs driven by advancing artificial intelligence reasoning capabilities. Pioneering systems like

Adam [

1] proposed closing hypothesis-experiment cycles through robot scientists, while specialized deep learning breakthroughs like

AlphaFold [

2] achieved landmark success in protein structure prediction, drastically accelerating discovery in focused domains.

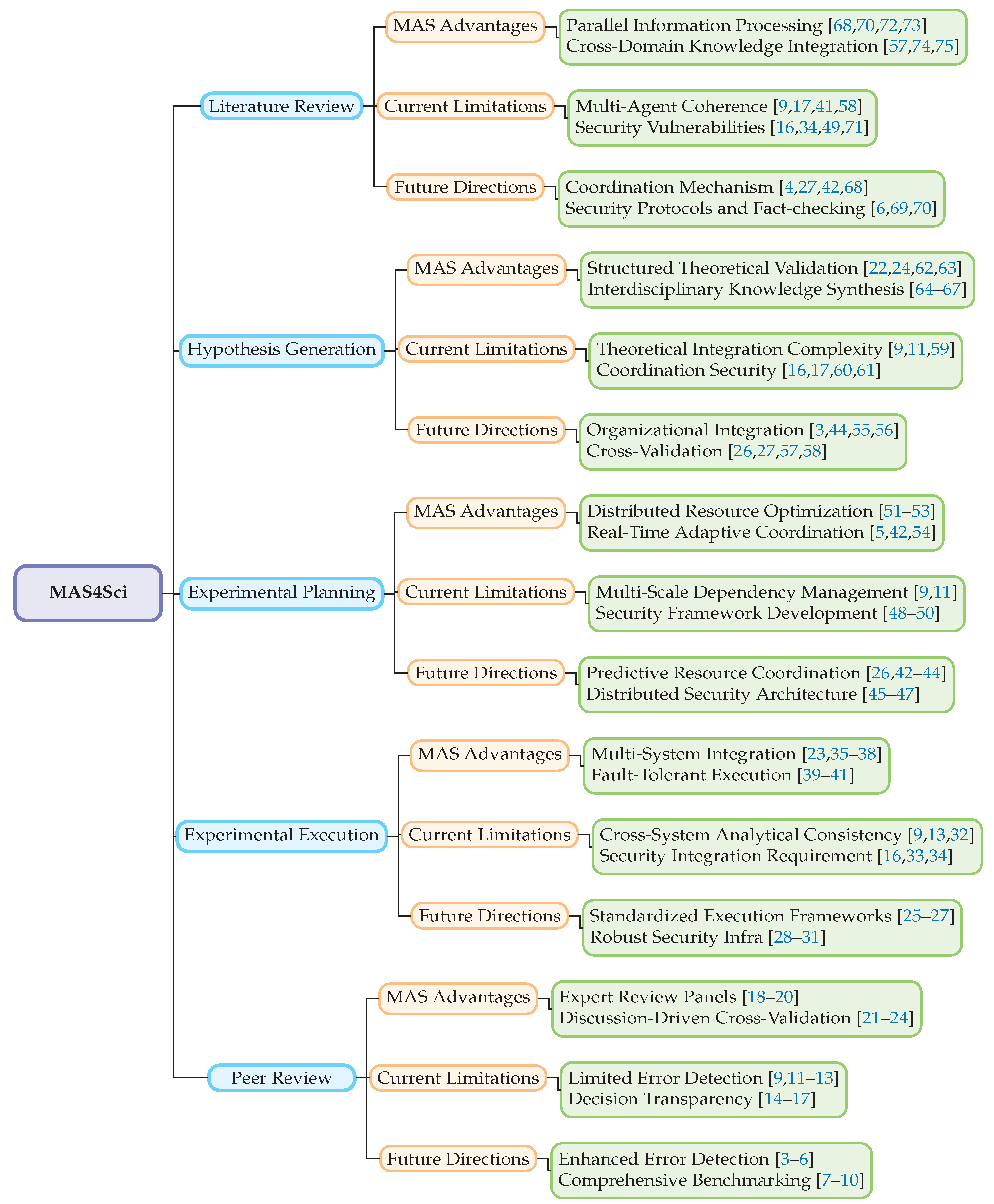

Figure 1.

An application-oriented taxonomy of Multi-Agent Systems for scientific discovery mapped to key stages of standard research workflow

Figure 1.

An application-oriented taxonomy of Multi-Agent Systems for scientific discovery mapped to key stages of standard research workflow

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) unlocked more general scientific reasoning capabilities. AI systems can now integrate knowledge across disciplines, engage in human-like discourse, and tackle diverse challenges from mathematical theorem proving with

AlphaProof [

76] to experimental design. This catalyzed a paradigm shift where AI evolved from assistive tools [

77,

78] toward autonomous agents [

29,

38,

79] emulating independent researchers, advancing work across physics [

80,

81], biochemistry [

39,

52,

82,

83], causal inference [

84], social sciences [

85,

86], and clinical diagnosis [

15,

32].

Building on these LLM foundations, recent breakthroughs of

Grok-4-Heavy [

87] and

Gemini-DeepThink [

88] explored multi-agent schema [

89,

90] to mirror collective reasoning dynamics of human research teams. These systems achieved leading performance on challenging benchmarks including the International Mathematical Olympiad

2 and Humanity’s Last Exam [

91], signaling a transition toward MAS architectures that can leverage collaborative intelligence for scientific discovery.

1.1. Scope and Comparison to other surveys

Despite these advances, existing surveys [

92,

93,

94] remain fragmented across domains and isolated tasks. They lack holistic views of MAS potential in complete research workflows. We address this gap through comprehensive analysis detailing MAS advantages over single agents, confronting current limitations with key bottlenecks, and outlining a roadmap toward transforming MAS from ideals into reliable co-scientists.

We structure this work around three core dimensions. First, we examine advantages of multi- versus single-agent systems across five key workflow stages (Section 2). Second, we detail key bottlenecks limiting MAS deployment (Section 3). Third, we outline strategic future directions toward realizing their full potential for science (Section 4).

2. Multi vs. Single Agent across Key Stages in Scientific Research Workflow

We present an analytical taxonomy comparing Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) against single-agent approaches across 5 key stages of scientific workflow. Our analysis examines how distributed architectures can transform each stage from sequential processing to parallel synthesis.

2.1. Literature Review

Advancing literature review requires transitioning from sequential knowledge compression to distributed multidimensional synthesis. This approach preserves specialized understanding while enabling cross-domain integration. Multi-agent systems demonstrate advantages through three architectural mechanisms.

First,

distributed semantic processing maintains independent embedding spaces for domain-specific concepts. Single agents must compress diverse terminologies into unified spaces, potentially causing semantic interference. Retrieval agents [

95] achieve over 30 percent higher recall on cross-domain queries by maintaining separate chemistry-trained embeddings. These embeddings recognize terminological equivalences. Single agents with unified embeddings may conflate terms due to

embedding collapse, where fine-tuning on one domain corrupts representations learned for others.

Second, parallel evidence validation constructs multi-dimensional evidence networks. Fact-checking agents [

70] simultaneously evaluate claims against multiple sources. They identify over twice as many inter-study contradictions than sequential single agents. Sequential approaches may suffer from temporal gaps creating memory interference. The mechanism involves maintaining active representations of all claims simultaneously in distributed agent memory, rather than relying on recency-biased working memory where earlier claims can fade.

Third, emergent interdisciplinary synthesis through asynchronous agent communication [

68] discovers latent cross-domain connections. Agents continuously broadcast partial insights that other agents pattern-match against specialized knowledge. This enabled linking bacterial quorum sensing to neural synchronization through shared mathematical frameworks. Such connections require simultaneous activation of biological and mathematical concept spaces that single agents typically cannot maintain due to attention bottlenecks.

Computational biology applications [

89] demonstrate over 40 percent higher accuracy in predicting phenotype-genotype relationships. Knowledge-enhanced frameworks [

72] achieve bias mitigation through ensemble disagreement where systematic errors become detectable through output variance. This approaches objectivity through dialectical contradiction [

73], where disagreement signals prompt deeper investigation. This contrasts with consensus-seeking single agents that may produce superficial agreement.

2.2. Hypothesis Generation

Transforming hypothesis generation requires moving from confirmation-biased sequential exploration to adversarial parallel search. This approach systematically investigates possibility spaces through productive tension. The architectural advantages manifest through three mechanisms.

First,

adversarial search through opponent modeling uses debate systems [

22] that maintain separate value functions for competing hypotheses. This creates game-theoretic exploration that systematically investigates regions confirmation-biased single agents may avoid. Adversarial systems explore nearly 4 times more diverse hypothesis spaces. Over half of high-value hypotheses reside in regions single agents never explored due to early convergence. This diversity stems from adversarial pressure forcing generators to explore regions where critics are weak, creating more systematic coverage of possibility space.

Second,

distributed falsification employs specialized critic agents [

62] that maintain separate failure mode memories for different hypothesis classes. Conditional effect evaluation [

24] demonstrates adversarial agents uncover over 4 times more failure modes per hypothesis. Single-agent self-critique may suffer from shared computational graph biases where gradients from generation interfere with evaluation. This separation enables critics to develop more sophisticated falsification strategies without maintaining generative capability.

Third, co-evolutionary learning dynamics [

63] involve generators and critics engaging in arms-race optimization. This creates sustained innovation pressure that may be absent in single agents where self-improvement can plateau. Drug discovery benchmarks show agent swarms [

66] with parallel structural biology, medicinal chemistry, pharmacokinetics, and toxicology agents achieve markedly higher hit rates versus sequential single-agent screening. Autonomous molecular design [

67] discovers nearly 3 times more Pareto-optimal compounds through parallel evaluation. Sequential filtering may eliminate compounds before multi-objective optimality becomes apparent. Principle-aware frameworks [

65] separate generative and evaluative processes across agents, producing substantially higher experimental validation rates.

2.3. Experimental Planning

Experimental planning benefits from transitioning to adaptive distributed coordination. This maintains resilience through continuous local negotiation rather than brittle global optimization. Multi-agent planning demonstrates advantages through three mechanisms.

First,

distributed constraint satisfaction via market-based negotiation [

51] allows agents to optimize local objectives through iterative bidding. They can discover Pareto-efficient allocations without combinatorial explosion. Single-agent global optimization becomes intractable beyond 15-20 concurrent experiments. Multi-agent negotiation achieves near 90 percent optimal resource utilization requiring orders of magnitude less computation than single-agent mixed-integer programming. This stems from decomposing global optimization into local decisions. Agents make decisions with limited information, trading slight optimality for tractability while enabling real-time adaptation.

Second,

hierarchical contingency planning [

53,

77] divides responsibilities between strategic and tactical agents. Strategic agents maintain coarse possibility trees while tactical agents elaborate high-probability branches. This creates depth-variable planning allocating computation to likely scenarios. Hierarchical planners adapt to disruptions over 5 times faster than single-agent replanners by switching between pre-elaborated branches rather than replanning from scratch. They maintain substantially better schedule efficiency under uncertainty versus single agents. The speed advantage stems from amortizing planning computation across possible futures.

Third, distributed anomaly detection through ensemble monitoring [

5] uses agents that independently model expected trajectories using different features. They trigger alerts when ensemble variance indicates deviations from all models simultaneously. This achieves over 90 percent precision identifying genuine degradation versus single-agent threshold detection. Multi-model consensus filters false positives. Chemical coordination systems [

52] demonstrate multi-agent negotiation adapting to synthesis rate variations with dramatically reduced response latency. Multi-agent reinforcement learning [

42] achieves substantially higher accuracy predicting experimental failures several hours in advance versus single agents lacking diverse observational perspectives.

2.4. Experimental Execution

Advancing experimental execution requires moving from brittle monolithic control to robust distributed intelligence. This maintains system-level functionality through redundant capabilities and hierarchical error recovery. Multi-agent execution robustness emerges from three mechanisms.

First,

hierarchical error recovery [

38] divides responsibilities across multiple levels. Operational agents detect anomalies. Tactical agents diagnose root causes by querying multiple operational agents for correlated symptoms. Strategic agents evaluate fix alignment with objectives. This creates graceful degradation versus binary single-agent failures. Quantum chemistry benchmarks show over 90 percent success rate on convergence-challenging systems versus single agents. Most recoveries involve tactical agents suggesting alternative methods that operational agents successfully execute. The recovery advantage stems from separating detection, diagnosis, and solution selection across specialized agents.

Second,

cross-abstraction bidirectional communication [

35,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100] connects agents at different levels through learned translation functions. High-level insights immediately constrain low-level choices. Low-level failures trigger high-level strategy revision. This achieves nearly 3 times faster adaptation to unexpected conditions versus single agents propagating information through sequential layers. The mechanism involves continuous information exchange where operational agents stream execution state to tactical agents updating strategy probabilities in real-time.

Third, ensemble metacognition [

36] uses agents that maintain independent performance models. These models predict success probability on different problem classes, enabling task routing to agents with highest predicted success. Ensemble disagreement serves as uncertainty signals triggering human consultation. This achieves substantially better task success with moderate human consultation versus single agents that may lack self-knowledge for appropriate help-seeking. Paper-to-code systems [

23,

37] demonstrate markedly higher success reproducing paper results versus single agents through distributed comprehension. Biomedical applications [

39,

40] achieve considerably lower technical variation through distributed monitoring where agents independently assess experimental quality using different features.

2.5. Peer Review

Peer review benefits from transitioning to structured collective intelligence. This captures multi-perspective assessment while reducing human inconsistencies through systematic protocols. Multi-agent review demonstrates advantages through three mechanisms.

First,

expertise-weighted ensemble aggregation [

18] uses agents that maintain expertise profiles quantifying domain knowledge. This enables dynamic weighting where specialists have proportional influence in their areas rather than uniform weighting treating all knowledge as equally authoritative. Agents self-assess expertise through calibration tasks where performance determines weights applied to review contributions. This achieves substantially stronger correlation with expert human reviews versus single-agent reviews, attributed to more appropriate expertise utilization.

Second,

multi-phase structured argumentation [

19] uses separate groups that sequentially evaluate evidence quality, methodological rigor, theoretical significance, and inter-phase consistency. This creates explicit separation preventing confounding between independent quality dimensions. The approach identifies over 3 times more methodological flaws and twice as many theoretical inconsistencies versus single agents performing holistic evaluation. Attention bottlenecks may force trade-offs between dimensions. Evidence agents assess support quality. Methodology agents evaluate experimental design. Theory agents assess conceptual contribution. Meta-review agents check for conflicts between phase assessments.

Third, adaptive evaluation depth through meta-agents [

20] monitors progress and dynamically allocates specialists to papers exhibiting high variance in initial evaluations. Resources concentrate on controversial papers requiring deeper analysis. This achieves over 90 percent decision accuracy requiring substantially less computation than uniform single-agent review. Intelligent resource allocation focuses effort where genuine uncertainty exists. Multi-agent systems demonstrate strong calibration where most high-confidence acceptances achieve above-median citation impact. CycleResearcher [

21] adds iterative refinement through author-reviewer dialogue where revision-specialized agents help authors address concerns while consistency-checking agents verify that revisions actually address identified issues.

3. Current Reality and Key Bottlenecks

3.1. Literature Review

Achieving reliable distributed knowledge synthesis from vast literature of highly interdisciplinary nature requires overcoming three critical challenges.

First,

semantic fragmentation through representation drift occurs when specialized agents independently fine-tune embeddings. Semantic spaces can diverge such that identical concepts acquire incompatible representations. Research reveals [

8] similarity between equivalent concepts across biology and physics agents degrades dramatically after domain-specific training versus shared embeddings. This creates substantially higher error rates in cross-domain synthesis versus single agents maintaining unified representations.

Second,

cascading knowledge conflicts [

41] arise when incorrect information propagates through trust mechanisms. This can create avalanche dynamics where network error rates grow exponentially with connectivity. Systems with 20 agents and moderate connectivity exhibit severely elevated network error rates despite relatively modest individual rates. Distributed architectures can amplify rather than average errors when lacking effective conflict detection.

Third,

adversarial manipulation [

17,

61] exploits the distributed nature of MAS. Controlling 15-20 percent of agents through coordinated bias injection shifts system conclusions substantially. Individual outputs appear reasonable in isolation. Single agents avoid this vulnerability through architectural simplicity where attacks require directly corrupting model weights rather than subtly influencing discussion dynamics.

3.2. Hypothesis Generation

Realizing secure yet effective hypothesis exploration present 3 unique challenges that arise with the collaborative settings of multi-agent systems:

First,

exploration space manipulation [

16] involves adversarial agents injecting biased priors that subtly reshape probability landscapes. Collective exploration steers toward predetermined regions without explicit false claims triggering detection. Empirical red-team exercises demonstrate controlling 10-15 percent of agents enables shifting over half of computational resources to attacker-preferred regions. Compounded bias accumulation occurs over iterative refinement rounds.

Second,

failure mode concealment exploits coordination between proposing agents and colluding critics [

46]. They coordinate to hide hypothesis weaknesses, achieving substantially higher success advancing flawed hypotheses versus independent critics. Adversarial coordination defeats independent evaluation assumptions.

Third, the creativity-security tradeoff creates tension between safety and innovation. Countermeasures preventing manipulation may also suppress legitimate boundary-pushing exploration. Strict verification protocols reduce novelty scores substantially. Single agents avoid these vulnerabilities through transparent reasoning chains where hypotheses trace to explicit model computations auditable through gradient analysis. However, they produce more conservative hypotheses with lower novelty scores than uncorrupted multi-agent systems.

3.3. Experimental Planning

Achieving efficient experimental planning presents 3 core challenges:

First,

negotiation overhead scales poorly with system size. Achieving consensus requires iterative communication scaling quadratically with agent count [

4]. Systems with over 25 agents spend majority of time negotiating rather than executing. Single-agent planning completes much faster for moderate-sized experiment schedules versus multi-agent with marginally better utilization. Communication overhead can negate distributed optimization benefits at modest scale.

Second,

local-global coherence breakdown occurs when agents optimize local objectives with incomplete information. They may produce locally efficient solutions combining into globally suboptimal configurations. MULTITASK experiments [

51] reveal distributed negotiation achieves notably lower fraction of theoretical optimum versus centralized approaches on tractable problems. Agents have limited ability to reason about distant dependencies.

Third,

brittleness under uncertainty [

59] affects tightly coupled plans optimized for expected scenarios. They achieve substantially lower completion rates under high variability versus robust single-agent plans accepting suboptimal expected performance. Tension exists between distributed optimization producing locally optimal but potentially globally fragile solutions versus centralized robust optimization.

3.4. Experimental Execution

Maintaining interpretable distributed execution requires future studies to address 3 core challenges:

First,

decision attribution difficulty [

9] arises from emergent behaviors from complex agent interactions. This creates gradient obfuscation preventing identification of which decisions caused outcomes. Interpretability degrades substantially. Explaining unexpected results requires analyzing over 100 inter-agent communications versus handful of decision points for single agents.

Second,

diluted expertise creates situations where no agent possesses sufficient context for holistic error detection [

12,

13]. Distributing knowledge reduces systemic error detection substantially. Single agents maintaining comprehensive models outperform multi-agents where errors spanning domains may fall between responsibility boundaries.

Third, the

security-adaptability tradeoff [

16,

33] involves verification protocols adding considerable latency per decision. This makes real-time adaptation challenging for systems requiring rapid response. Single agents achieve secure execution through signed logs without consensus overhead, though sacrificing distributed intelligence enabling parallel processing.

3.5. Peer Review

Ensuring trustworthy collective evaluation need to further ensure mitigation of 3 key security challenges:

First,

opinion cascades [

15] occur when early influential agents trigger bandwagon effects. Strong correlation exists between early and final consensus despite adding many reviewers, versus much weaker correlation expected under independence. Later agents potentially anchor evaluations around emerging consensus. Adversarial agents strategically contributing early opinions may achieve disproportionate influence.

Second, distributed doubt injection uses adversarial agents coordinating to amplify minor concerns through strategic repetition. They successfully shift recommendations from accept to reject in substantial fraction of red-team trials despite objectively minor concerns. Single agents avoid social manipulation through architectural isolation, though exhibiting strong correlation with own prior reviews indicating systematic training biases.

Third, error amplification through multi-stage processing propagates initial methodology assessment errors to theoretical evaluation. This creates cascade failures, resulting in substantially elevated overall false negative rates despite more modest initial rates. Single-stage single-agent review achieves notably lower false negative rates, which may be superior despite lacking multiple perspectives. Unified evaluation prevents error propagation across stages.

4. Future Work Towards MAS4Science

4.1. Literature Review

Resolving semantic fragmentation requires three technical approaches that maintain specialization benefits while preserving cross-domain communication.

First and foremost, future MAS should

learn shared semantic alignments [

3,

68] involves agents periodically synchronizing embeddings by training alignment networks. These networks map between specialized representations, potentially maintaining communication channels despite domain-specific fine-tuning. The mechanism identifies anchor concepts with known equivalences and trains translation networks minimizing distance between aligned concepts while allowing unaligned concepts to diverge. Preliminary experiments show alignment networks preserving substantially stronger cross-domain similarity versus systems without alignment through contrastive learning on equivalent concepts.

Second,

preserving causal structure [

55,

63] uses agents that learn intermediate representations encoding invariant causal relationships and mathematical constraints. This potentially enables better cross-domain translation through causality rather than surface-level semantic similarity, which may be highly polysemantical and therefore misleading for LLMs.

Third,

federated semantic learning [

27,

57] involves agents negotiating semantic bridges through iterative proposal-validation cycles. Successful translations strengthen bridge confidence through positive evidence accumulation. This creates evolutionary selection for robust semantic mappings surviving diverse domain-specific validation, achieving over

twice higher cross-domain knowledge transfer accuracy comparing to traditional static pre-defined mappings.

4.2. Hypothesis Generation

We outline 4 future research directions that improve the core mechanisms aiming to preserve creative freedom while preventing malicious manipulation or unbalanced multi-agent interactive dynamic.

To start with,

zero-knowledge proof protocols [

6] allow agents to prove they followed logical inference rules without revealing intermediate reasoning steps. This potentially enables verification that generation satisfied validity constraints without exposing intellectual property. Prototype implementations achieve over 90 percent detection of rule-violating adversarial agents while maintaining complete confidentiality, though adding moderate latency.

Second,

differential privacy for collective exploration [

45] enables agents to share privacy-preserving statistics about hypothesis spaces. This enables coordination without revealing specific proposals, achieving substantial fraction of full information efficiency while providing formal privacy guarantees.

Third,

behavioral forensics [

46] uses graph neural networks trained on honest interaction patterns to detect adversarial coordination. Statistical anomalies in communication patterns reveal coordinated manipulation, achieving strong precision and recall.

Fourth,

incentive-compatible mechanisms [

47] use game-theoretic reward structures where agents gain more utility from collaborative discovery than sabotaging competitors. These have been proven to achieve Nash equilibrium at cooperative strategies for substantial numbers of agents.

4.3. Experimental Planning

Handling future experimental planning challenges could significantly benefit from 3 approaches that reduce coordination overhead while maintaining optimization quality.

First,

hierarchical compositional planning [

42,

101] divides planning across levels. High-level agents negotiate coarse allocations while low-level agents elaborate approved allocations into detailed schedules. This potentially reduces negotiation complexity from quadratic to logarithmic scaling. Experiments show 50-agent hierarchical systems achieve consensus much faster versus flat architectures while maintaining over 90 percent optimization quality. The mechanism involves clustering experiments by resource requirements with group representatives handling inter-group coordination.

Second,

learning dependency models [

43] uses agents employing reinforcement learning to discover which dependencies require explicit coordination versus independent planning with occasional reactive conflict resolution. This reduces communication overhead substantially while maintaining very high feasibility. Learning discriminates truly coupled decisions from spurious dependencies.

Third,

robust distributional planningmaintains probability distributions over outcomes rather than point estimates. Agents identify plans remaining feasible across a range of possible outcome possibilities. Monte Carlo evaluation [

102] shows distributional planning achieve substantially higher completion rates under uncertainty.

4.4. Experimental Execution

Future execution systems could benefit from various transparency mechanisms that ensures accountability and tractability of high-stake actions in laboratory settings.

First,

hierarchical explanation generation [

23,

36] uses agents maintaining causal models enabling counterfactual reasoning. This potentially produces interpretable explanations by composing agent-level counterfactuals into system-level causal narratives. Preliminary studies show hierarchical explanations achieve substantially stronger correlation with expert explanations versus attention-based methods. Explicit causal structure provides advantages over learned attention patterns, especially in novel unseen scenarios such as accidents in lab.

Furthermore,

anomaly attribution through intervention analysis [

5] systematically disables agents and observes which disablements eliminate anomalous behaviors. This potentially identifies responsible agents through controlled experimentation. The approach achieves markedly higher root cause accuracy versus gradient-based attribution, though requiring multiple intervention trials creating latency unsuitable for time-critical decisions.

Third,

selective transparency [

39] exposes rationales at granularity proportional to decision impact. Agents provide coarse explanations for routine decisions and detailed reasoning for high-stakes decisions. This achieves substantial reduction in explanation overhead while maintaining excellent interpretability for decisions requiring human understanding.

4.5. Peer Review

Future peer review (where your future peer reviewers may also be AI agents as adopted by conference like AAAI) could benefit from several transparency-improving approaches that leverage the advantage of collective intelligence and improve research reproducibility with streamlined multi-agent cross-validation for the community at large.

First,

structured argumentation graphs [

19] decompose reviews into atomic claims connected by explicit logical relationships. This potentially enables verification of argument validity through user-defined inference rules. Graph-based reviews achieve substantially stronger agreement with formal logic verification versus narrative reviews where logical structure remains implicit.

Second,

ensemble reproducibility checks [

10,

103] use multiple independent agent teams attempting to reproduce results. Reproduction success potentially provides stronger evidence than review opinions that may miss practical implementation issues. Analysis shows ensemble reproducibility checks identify nearly 3 times more implementation problems than traditional review.

Third,

conditional evaluation [

65] requires agents to explicitly state assumptions under which assessments hold. This potentially enables nuanced evaluation avoiding false binary decisions by acknowledging context-dependence.

Last but not least,

uncertainty-aware aggregation [

104,

105] provides confidence distributions rather than point estimates. This enables human-in-the-loop intervention in cases of insufficient multi-agent consensus. It could also serve as a sanity check and additional evidence for peer review in the current research landscape with exponentially growing number of papers and correspondingly higher reviewer workload.

5. Vision and Conclusions

The evolution from single-agent to multi-agent systems for scientific discovery represents a paradigm shift towards collaborative intelligence. These systems take inspiration from how human researchers cooperate to expand knowledge frontiers. Our vision goes beyond mere automation toward enabling new forms of collaborative inquiry where AI agents serve as autonomous co-scientists with refreshing perspective alongside human researchers.

6. Limitations

This survey provides an overview of the current reality and future prospects of MAS for scientific discovery (MAS4Science). However, certain limitations in the scope and methodology of this paper warrant acknowledgment.

6.1. References and Methods

Due to page limits, this survey may not capture all relevant literature, particularly given the rapid evolution of both multi-agent and AI4Science research. We focus on frontier works published between 2023 and 2025 in leading venues, including conferences such as *ACL, ICLR, ICML, and NeurIPS, and journals like Nature, Science, and IEEE Transactions. Ongoing efforts will monitor and incorporate emerging studies to ensure the survey remains current.

6.2. Empirical Conclusions

Our analysis and proposed directions rely on empirical evaluations of existing MAS frameworks, which may not fully capture the field’s macroscopic dynamics. The rapid pace of advancements risks outdating certain insights, and our perspective may miss niche or emerging subfields. We commit to periodically updating our assessments to reflect the latest developments and broader viewpoints.

7. Ethical Considerations

Despite our best effort to responsibly synthesize the current reality and future prospects at the intersection of AI4Science and Multi-Agent Research, ethical challenges remain as the selection of literature may inadvertently favor more prominent works, and may potentially overlook contributions from underrepresented research communities. We aim to uphold rigorous standards in citation practices and advocate for transparent, inclusive research to mitigate these risks. References

References

- King, R.; Whelan, K.E.; Jones, F.; Reiser, P.G.K.; Bryant, C.H.; Muggleton, S.; Kell, D.; Oliver, S. Functional genomic hypothesis generation and experimentation by a robot scientist. Nature 2004, 427, 247–252.

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. An Organizational Theory for Multi-Agent Interactions Integrating Human Agents, LLMs, and Specialized AI. Discover Computing 2025.

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, D.; Li, C. Beyond Self-Talk: A Communication-Centric Survey of LLM-Based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.14321.

- Khalili, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y. Multi-Agent Systems for Model-based Fault Diagnosis. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 1211–1216. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, X. PeerGuard: Defending Multi-Agent Systems Against Backdoor Attacks Through Mutual Reasoning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11642.

- Chen, H.; Xiong, M.; Lu, Y.; Han, W.; Deng, A.; He, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hooi, B. MLR-Bench: Evaluating AI Agents on Open-Ended Machine Learning Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.19955.

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xie, T.; Ni, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Ouyang, W.; Cambria, E.; Zhou, D. ResearchBench: Benchmarking LLMs in Scientific Discovery via Inspiration-Based Task Decomposition. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.21248.

- Kon, P.T.J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Ding, Q.; Peng, J.; Xing, J.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Srinivasa, J.; Lee, M.; et al. EXP-Bench: Can AI Conduct AI Research Experiments? ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.24785.

- Siegel, Z.S.; Kapoor, S.; Nagdir, N.; Stroebl, B.; Narayanan, A. CORE-Bench: Fostering the Credibility of Published Research Through a Computational Reproducibility Agent Benchmark. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 2024.

- Son, G.; Hong, J.; Fan, H.; Nam, H.; Ko, H.; Lim, S.; Song, J.; Choi, J.; Paulo, G.; Yu, Y.; et al. When AI Co-Scientists Fail: SPOT-a Benchmark for Automated Verification of Scientific Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11855.

- L’ala, J.; O’Donoghue, O.; Shtedritski, A.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S.G.; White, A.D. PaperQA: Retrieval-Augmented Generative Agent for Scientific Research. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.07559.

- Starace, G.; Jaffe, O.; Sherburn, D.; Aung, J.; Chan, J.S.; Maksin, L.; Dias, R.; Mays, E.; Kinsella, B.; Thompson, W.; et al. PaperBench: Evaluating AI’s Ability to Replicate AI Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.01848.

- Li, G.; Hammoud, H.; Itani, H.; Khizbullin, D.; Ghanem, B. CAMEL: Communicative Agents for "Mind" Exploration of Large Language Model Society. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.X.; Hong, S. ArgMed-Agents: Explainable Clinical Decision Reasoning with LLM Disscusion via Argumentation Schemes. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) 2024, pp. 5486–5493.

- Zheng, C.; Cao, Y.; Dong, X.; He, T. Demonstrations of Integrity Attacks in Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.04572.

- Amayuelas, A.; Yang, X.; Antoniades, A.; Hua, W.; Pan, L.; Wang, W. MultiAgent Collaboration Attack: Investigating Adversarial Attacks in Large Language Model Collaborations via Debate. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024.

- Jin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J. AgentReview: Exploring Peer Review Dynamics with LLM Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, November 12-16, 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 1208–1226. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Weng, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. DeepReview: Improving LLM-based Paper Review with Human-like Deep Thinking Process. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.08569.

- Yu, W.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Dong, N.; Fan, L.; Qi, H.; Guo, C. Dynamic Knowledge Exchange and Dual-Diversity Review: Concisely Unleashing the Potential of a Multi-Agent Research Team. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18348 2025.

- Weng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Bao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. CycleResearcher: Improving Automated Research via Automated Review. ArXiv 2024, abs/2411.00816.

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Mordatch, I. Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2024, Vienna, Austria, July 21-27, 2024, 2024.

- Seo, M.; Baek, J.; Lee, S.; Hwang, S.J. Paper2Code: Automating Code Generation from Scientific Papers in Machine Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17192.

- Yang, Y.; Yi, E.; Ko, J.; Lee, K.; Jin, Z.; Yun, S. Revisiting Multi-Agent Debate as Test-Time Scaling: A Systematic Study of Conditional Effectiveness. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.22960.

- Perera, R.; Basnayake, A.; Wickramasinghe, M. Auto-scaling LLM-based multi-agent systems through dynamic integration of agents. Frontiers in AI 2025.

- Tang, X.; Qin, T.; Peng, T.; Zhou, Z.; Shao, D.; Du, T.; Wei, X.; Xia, P.; Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; et al. Agent KB: Leveraging Cross-Domain Experience for Agentic Problem Solving, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.06229].

- Surabhi, P.S.M.; Mudireddy, D.R.; Tao, J. ThinkTank: A Framework for Generalizing Domain-Specific AI Agent Systems into Universal Collaborative Intelligence Platforms. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.02931.

- Ifargan, T.; Hafner, L.; Kern, M.; Alcalay, O.; Kishony, R. Autonomous LLM-driven research from data to human-verifiable research papers. ArXiv 2024, abs/2404.17605.

- Lu, C.; Lu, C.; Lange, R.T.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2408.06292].

- Schmidgall, S.; Moor, M. AgentRxiv: Towards Collaborative Autonomous Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.18102.

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z.; An, D. OriGene: A Self-Evolving Virtual Disease Biologist Automating Therapeutic Target Discovery. bioRxiv 2025.

- Chen, X.; Yi, H.; You, M.; Liu, W.Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. NPJ Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 65. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, P.; Yang, B.; Chandran, N.; Gupta, D. Privacy Preserving Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning in Supply Chains. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.05686.

- Shanmugarasa, Y.; Ding, M.; Chamikara, M.; Rakotoarivelo, T. SoK: The Privacy Paradox of Large Language Models: Advancements, Privacy Risks, and Mitigation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.12699.

- Li, Y.; Choi, D.; Chung, J.; Kushman, N.; Schrittwieser, J.; Leblond, R.; Eccles, T.; Keeling, J.; Gimeno, F.; Dal Lago, A.; et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. Science 2022, 378, 1092–1097.

- Pan, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C. CodeCoR: An LLM-Based Self-Reflective Multi-Agent Framework for Code Generation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.07811.

- Lin, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, M. AutoP2C: An LLM-Based Agent Framework for Code Repository Generation from Multimodal Content in Academic Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.20115.

- Zou, Y.; Cheng, A.H.; Aldossary, A.; Bai, J.; Leong, S.X.; Campos-Gonzalez-Angulo, J.A.; Choi, C.; Ser, C.T.; Tom, G.; Wang, A.; et al. El Agente: An Autonomous Agent for Quantum Chemistry, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.02484].

- Gao, S.; Fang, A.; Lu, Y.; Fuxin, L.; Shao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, C.; Schneider, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Empowering biomedical discovery with AI agents. Cell 2024, 187, 6125–6151. [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, N.J.; Xiong, C.; Lan, K.; Yetisgen-Yildiz, M. Large Language Model-Based Agents for Automated Research Reproducibility: An Exploratory Study in Alzheimer’s Disease. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23852.

- Ju, T.; Wang, B.; Fei, H.; Lee, M.L.; Hsu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Investigating the Adaptive Robustness with Knowledge Conflicts in LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.15153.

- Azadeh, R. Advances in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: Persistent Autonomy and Robot Learning Lab Report 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.21088 2024.

- Swanson, K.; Wu, W.; Bulaong, N.L.; Pak, J.E.; Zou, J. The Virtual Lab: AI Agents Design New SARS-CoV-2 Nanobodies with Experimental Validation. bioRxiv 2024. Preprint, . [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, C.; Xia, Y.; Shi, R.; Dang, Y.; Xie, Z.; You, Z.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.; et al. Cross-Task Experiential Learning on LLM-based Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23187.

- Szymanski, N.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; Kumar, R.E.; He, T.; Milsted, D.; McDermott, M.J.; Gallant, M.C.; Cubuk, E.D.; Merchant, A.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86 – 91.

- Jin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, W.; Liao, Y.; Feng, L.; Hu, M.; Li, B. TopoMAS: Large Language Model Driven Topological Materials Multiagent System. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.04053].

- Wölflein, G.; Ferber, D.; Truhn, D.; Arandjelovi’c, O.; Kather, J. LLM Agents Making Agent Tools. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.11705.

- Seo, S.; Kim, J.; Shin, M.; Suh, B. LLMDR: LLM-Driven Deadlock Detection and Resolution in Multi-Agent Pathfinding. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.00717.

- de Witt, C.S. Open Challenges in Multi-Agent Security: Towards Secure Systems of Interacting AI Agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.02077.

- Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lyu, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.T.; Shen, Y. Multi-Agent Coordination across Diverse Applications: A Survey, 2025, [arXiv:cs.MA/2502.14743].

- Kusne, A.G.; McDannald, A. Scalable multi-agent lab framework for lab optimization. Matter 2023. [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.A.; MacKnight, R.; Kline, B.; Gomes, G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature 2023, 624, 570–578. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sarkar, M.; Lonappan, A.I.; Íñigo Zubeldia.; Villanueva-Domingo, P.; Casas, S.; Fidler, C.; Amancharla, C.; Tiwari, U.; Bayer, A.; et al. Open Source Planning & Control System with Language Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07257].

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, T.; Song, M. Parallelized Planning-Acting for Efficient LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.03505.

- Park, C.; Han, S.; Guo, X.; Ozdaglar, A.; Zhang, K.; Kim, J.K. MAPoRL: Multi-Agent Post-Co-Training for Collaborative Large Language Models with Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.18439.

- Lan, T.; Zhang, W.; Lyu, C.; Li, S.; Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Lin, D.; Mao, X.L.; Chen, K. Training Language Models to Critique With Multi-agent Feedback. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.15287.

- Du, Z.; Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, R.; Dang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Tian, Y.; et al. Multi-Agent Collaboration via Cross-Team Orchestration. arXiv 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2406.08979]. Accepted to Findings of ACL 2025.

- Zhu, K.; Du, H.; Hong, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qian, C.; Tang, X.; Ji, H.; et al. MultiAgentBench: Evaluating the Collaboration and Competition of LLM agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.01935.

- Soldatova, L.N.; Rzhetsky, A. Representation of research hypotheses. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 2011, 2, S9 – S9.

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Fang, M. Deep Research Agents: A Systematic Examination And Roadmap. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18096 2025.

- Tran, K.T.; Dao, D.; Nguyen, M.D.; Pham, Q.V.; O’Sullivan, B.; Nguyen, H.D. Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanisms: A Survey of LLMs. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.06322.

- Bandi, C.; Harrasse, A. Adversarial Multi-Agent Evaluation of Large Language Models through Iterative Debates. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.04663.

- Pu, Z.; Ma, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, B.; Liang, Y.; Ai, X. Coevolving with the Other You: Fine-Tuning LLM with Sequential Cooperative Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.06101.

- Chun, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Ahmed, I. Is Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) the Silver Bullet? An Empirical Analysis of MAD in Code Summarization and Translation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.12029.

- Pu, Y.; Lin, T.; Chen, H. PiFlow: Principle-aware Scientific Discovery with Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.15047.

- Song, K.; Trotter, A.; Chen, J.Y. LLM Agent Swarm for Hypothesis-Driven Drug Discovery. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17967.

- Koscher, B.A.; Canty, R.B.; McDonald, M.A.; Greenman, K.P.; McGill, C.J.; Bilodeau, C.L.; Jin, W.; Wu, H.; Vermeire, F.H.; Jin, B.; et al. Autonomous, multiproperty-driven molecular discovery: From predictions to measurements and back. Science 2023, 382.

- Chen, X.; Che, M.; et al. An automated construction method of 3D knowledge graph based on multi-agent systems in virtual geographic scene. International Journal of Digital Earth 2024, 17, 2449185. [CrossRef]

- Al-Neaimi, A.; Qatawneh, S.; Saiyd, N.A. Conducting Verification And Validation Of Multi- Agent Systems, 2012, [arXiv:cs.SE/1210.3640].

- Nguyen, T.P.; Razniewski, S.; Weikum, G. Towards Robust Fact-Checking: A Multi-Agent System with Advanced Evidence Retrieval. arXiv preprint 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.17878].

- Ferrag, M.A.; Tihanyi, N.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L. From Prompt Injections to Protocol Exploits: Threats in LLM-Powered AI Agents Workflows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.23260 2025.

- Wang, H.; Du, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, K.; Chu, Z.; Yan, L.; Guan, Y. Learning to break: Knowledge-enhanced reasoning in multi-agent debate system. Neurocomputing 2023, 618, 129063.

- Li, Z.; Chang, Y.; Le, X. Simulating Expert Discussions with Multi-agent for Enhanced Scientific Problem Solving. Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Scholarly Document Processing (SDP 2024) 2024.

- Pantiukhin, D.; Shapkin, B.; Kuznetsov, I.; Jost, A.A.; Koldunov, N. Accelerating Earth Science Discovery via Multi-Agent LLM Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.05854.

- Solovev, G.V.; Zhidkovskaya, A.B.; Orlova, A.; Vepreva, A.; Tonkii, I.; Golovinskii, R.; Gubina, N.; Chistiakov, D.; Aliev, T.A.; Poddiakov, I.; et al. Towards LLM-Driven Multi-Agent Pipeline for Drug Discovery: Neurodegenerative Diseases Case Study. In Proceedings of the OpenReview Preprint, 2024.

- DeepMind, G. AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems, 2024.

- Xu, X.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Evaluating Retrieval-Augmented Generation Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery in Astrophysics. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07155].

- Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Chandak, P.; Liu, S.; Katwyk, P.V.; Deac, A.; et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47–60.

- Gottweis, J.; Weng, W.H.; Daryin, A.; Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Sirkovic, P.; Myaskovsky, A.; Weissenberger, F.; Rong, K.; Tanno, R.; et al. Towards an AI co-scientist, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2502.18864].

- Sarkar, M.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Multi-Agent System for Cosmological Parameter Analysis. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2412.00431].

- Lu, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, T.J.; Kos, P.; Cirac, J.I.; Schölkopf, B. Can Theoretical Physics Research Benefit from Language Agents?, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.06214].

- Jin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Cong, L. STELLA: Self-Evolving LLM Agent for Biomedical Research. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.02004].

- Bran, A.M.; Cox, S.; Schilter, O.; Baldassari, C.; White, A.D.; Schwaller, P. Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 525–535. Published 08 May 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Acharya, S.; Simko, S.; Bhardwaj, D.; Haghighat, A.; Sachan, M.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B.; Jin, Z. Causal AI Scientist: Facilitating Causal Data Science with Large Language Models. Manuscript Under Review 2025.

- Haase, J.; Pokutta, S. Beyond Static Responses: Multi-Agent LLM Systems as a New Paradigm for Social Science Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.01839.

- Parkes, D.C.; Wellman, M.P. Economic reasoning and artificial intelligence. Science 2015, 349, 267 – 272.

- xAI. Introducing Grok-4. https://x.ai/news/grok-4, 2025.

- DeepMind. Advanced version of Gemini with Deep Think officially achieves gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad, 2025. DeepMind Blog Post.

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Buehler, M.J. SciAgents: Automating scientific discovery through multi-agent intelligent graph reasoning. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2409.05556].

- Ghareeb, A.E.; Chang, B.; Mitchener, L.; Yiu, A.; Warner, C.; Riley, P.; Krstic, G.; Yosinski, J. Robin: A Multi-Agent System for Automating Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2505.13400].

- Phan, L.; Gatti, A.; Han, Z.; Li, N.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.B.C.; Shaaban, M.; Ling, J.; Shi, S.; et al. Humanity’s Last Exam, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2501.14249].

- Luo, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Du, X. LLM4SR: A Survey on Large Language Models for Scientific Research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04306 2025.

- Zheng, T.; Deng, Z.; Tsang, H.T.; Wang, W.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y. From Automation to Autonomy: A Survey on Large Language Models in Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.13259 2025.

- Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, J. Large language models for automated scholarly paper review: A survey. Information Fusion 2025, 124, 103332. [CrossRef]

- Sami, M.A.; Rasheed, Z.; Kemell, K.; Waseem, M.; Kilamo, T.; Saari, M.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Systä, K.; Abrahamsson, P. System for systematic literature review using multiple AI agents: Concept and an empirical evaluation. CoRR 2024, abs/2403.08399, [2403.08399]. [CrossRef]

- Mankowitz, D.J.; Michi, A.; Zhernov, A.; Gelada, M.; Selvi, M.; Paduraru, C.; Leurent, E.; Iqbal, S.; Lespiau, J.B.; Ahern, A.; et al. Faster sorting algorithms discovered using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2023, 618, 257–263.

- Trinh, T.H.; Wu, Y.; Le, Q.V.; He, H.; Luong, T. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 2024, 625, 476–482.

- Fawzi, A.; Balog, M.; Huang, A.; Hubert, T.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Barekatain, M.; Novikov, A.; Ruiz, F.J.; Schrittwieser, J.; Swirszcz, G.; et al. Discovering faster matrix multiplication algorithms with reinforcement learning. Nature 2022, 610, 47–53.

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354.

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Gordon, C.; Mert, U.; Sell, M. MASS: A Parallelizing Library for Multi-Agent Spatial Simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSIM Conference on Principles of Advanced Discrete Simulation (PADS). ACM, 2013, pp. 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, J. Agent-Oriented Planning in Multi-Agent Systems. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2410.02189].

- Xiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Ouyang, S.; Gui, L.; He, Y. SciReplicate-Bench: Benchmarking LLMs in Agent-driven Algorithmic Reproduction from Research Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.00255.

- Tang, K.; Wu, A.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G. Collaborative Editable Model. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.14146.

- Chen, N.; HuiKai, A.L.; Wu, J.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; He, B. XtraGPT: LLMs for Human-AI Collaboration on Controllable Academic Paper Revision. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11336.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).