1. Introduction

Poultry salmonellosis remains a persistent threat to animal health and food safety worldwide. Salmonella enterica infections in chickens often lead to asymptomatic intestinal colonization, contaminating poultry products and causing foodborne illnesses in humans. Non-typhoidal Salmonella is a leading cause of gastroenteritis, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimating approximately 1.35 million infections annually in the United States alone.

The global burden of non-typhoidal

Salmonella gastroenteritis is significant, with millions of cases reported each year worldwide [

1]. The impact on public health and the poultry industry is substantial, with

Salmonella ranked as the second most common zoonotic infection in Europe, accounting for 52,706 confirmed cases in 2020 [

2]. In developing regions, a high prevalence of

Salmonella in poultry flocks has been documented, such as in breeder farms in Bangladesh [

3]. Beyond causing acute illnesses,

Salmonella incurs considerable economic costs, including poultry mortality, decreased productivity, product recalls, and trade restrictions.

Compounding this issue is the rise of antimicrobial-resistant

Salmonella. The overuse of antibiotics in agriculture has accelerated the development of resistance [

3]. Multidrug-resistant

Salmonella strains severely limit treatment options for both animals and humans, leading to urgent calls for alternative control measures [

4,

5]. Vaccination of poultry against major

Salmonella serovars (e.g., Enteritidis and Typhimurium) is one strategy to reduce intestinal colonization and shedding, thereby lowering transmission through the food chain. Live attenuated

Salmonella vaccines have been successfully employed in poultry flocks to induce protective immunity and reduce environmental contamination [

6,

7]. However, traditional attenuation methods, such as chemical mutagenesis or gene deletion, are often time-consuming and costly, and there are safety concerns if attenuation is incomplete.

At the same time, immunotherapy using egg yolk antibodies (IgY) has attracted increasing attention as a promising antibiotic-free strategy for combating enteric pathogens [

8]. IgY is the avian equivalent of mammalian IgG, naturally found in large amounts in egg yolks. Hens immunized with specific antigens produce eggs rich in antigen-specific IgY, offering a convenient and scalable source of polyclonal antibodies. IgY has several advantages: it does not interact with mammalian Fc receptors or activate complement (thus avoiding inflammatory responses); it is stable across a pH range of 4–9 and moderately heat-resistant; and it can be produced in large quantities without invasive procedures like bleeding [

9,

10].

Each egg yolk can yield approximately 100 mg of IgY (with about 2–10% being antigen-specific), making IgY production both cost-effective and animal-welfare–friendly. Importantly, IgY can neutralize pathogens and toxins in the gut and prevent pathogen adhesion to mucosal surfaces. In poultry, oral administration of

Salmonella-specific IgY through feed or water has successfully reduced intestinal colonization and fecal shedding [

11,

12]. This form of "passive vaccination" can protect chicks during their critical early-life stages before their own immune systems have fully matured [

11,

12]. Moreover, IgY has demonstrated protective effects in a mouse model of

Salmonella infection [

13], suggesting potential translation to other animal species.

Integrating active vaccination with passive immunization via IgY could provide a synergistic approach to controlling Salmonella. In this model, a subset of hens (the vaccine flock) is actively immunized with a live attenuated Salmonella vaccine to induce high-titer IgY production. Eggs from these hens are then processed to extract IgY, which can be administered to the broader poultry population through feed or water. This dual strategy could achieve herd immunity (via vaccination) along with immediate protection (via IgY prophylaxis). A critical requirement for success is ensuring that the vaccine used to immunize hens is safe (non-pathogenic) yet sufficiently immunogenic. We hypothesized that indigenous plant extracts with known antimicrobial properties could be used to attenuate Salmonella naturally and cost-effectively, producing a live vaccine that elicits protective immunity without causing disease.

Garlic (

Allium sativum) and onion (

Allium cepa) are widely recognized for their antimicrobial compounds, particularly organosulfur molecules such as allicin. Allicin and related thiosulfinates inhibit a broad range of bacteria by disrupting microbial metabolism and enzyme activity. Live attenuated vaccines have been employed to protect against salmonellosis [

14,

15], and garlic has demonstrated strong bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity against

Salmonella and other enteric pathogens in vitro [

16,

17].

Onion also contains antimicrobial phytochemicals, such as quercetin and other flavonoids, and has a long history of use in traditional medicine for treating infections. Indigenous communities often utilize plants like garlic and onion for gastrointestinal ailments, supporting their relevance for farm-based interventions. Additionally, both plants are known to enhance immune function and may exert prebiotic effects when incorporated into poultry diets [

14,

18].

In this study, we developed a live attenuated Salmonella vaccine using garlic and onion extracts and evaluated its performance in poultry. The specific objectives were to: (1) identify indigenous plant extracts that can effectively attenuate multiple Salmonella serovars without compromising immunogenic epitopes; (2) verify that vaccinated chickens produce high levels of anti-Salmonella IgY antibodies; and (3) assess the potential of the resulting IgY for passive immunotherapy to protect other chickens against Salmonella infection. We also integrate findings from recent research on IgY applications to illustrate how vaccine-induced IgY can be used in field settings. By combining vaccine development with IgY-based therapy, our approach provides a holistic solution to Salmonella control, aiming to reduce antibiotic reliance and enhance food safety across the poultry industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Five wild-type Salmonella enterica strains were used to formulate a multivalent vaccine: S. Augustenborg, S. Montevideo, S. Kentucky, S. Yeerongpilly, and S. Typhimurium. These serovars were selected based on their prevalence in poultry and their significance in human salmonellosis. Each strain was confirmed by standard serological typing of O and H antigens and cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or nutrient broth at 37 °C with shaking. For plating and colony isolation, selective agar media were used, including Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar and Hektoen Enteric (HE) agar, which differentiate Salmonella by characteristic colony color and hydrogen sulfide production.

2.2. Preparation of Indigenous Plant Extracts

A variety of indigenous plants reputed for antimicrobial properties were screened for their ability to attenuate Salmonella. These included garlic (Allium sativum), onion (Allium cepa), Moringa, and other local herbs (e.g., taro/dasheen Colocasia esculenta, neem Azadirachta indica). Plant materials were sourced from local farms and markets and processed into crude extracts. Garlic and onion extracts were prepared by blending fresh bulbs with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 1:4 (w/v) ratio, filtering through muslin cloth, and centrifuging to clarify. Filtrates were sterilized using 0.22 μm filters. Extract concentrations were standardized based on dry weight, corresponding to 15 g of fresh plant tissue per liter of diluent.

2.3. Attenuation of Salmonella with Plant Extracts

Overnight cultures of each Salmonella strain were diluted to approximately 10⁶–10⁷ CFU/mL. Aliquots (100 μL) were spread onto selective agar plates pre-treated with plant extracts. Extracts were either incorporated into molten agar before pouring or applied to the surface of solidified agar. A range of extract concentrations (up to 25 g/L of garlic and/or onion) was tested to observe gradations in bacterial growth. Plates were incubated for 24–48 hours at 37 °C. Colony morphology and size were recorded for each treatment. Attenuation was assessed by reduced colony size, altered pigmentation, and notably, the loss of hydrogen sulfide production (typically seen as black-centered colonies on HE/XLD). The lowest extract concentration producing significantly smaller colonies without completely inhibiting growth was selected as optimal for attenuation. Combination treatment (garlic + onion) was also evaluated to assess potential synergistic effects.

For each condition, triplicate plates were prepared. Colony diameters were measured from a representative sample (at least 10 colonies per plate) using calipers or a stereomicroscope with an eyepiece micrometer. Mean colony diameter ± standard deviation (SD) was calculated. Bacteria from attenuated colonies were harvested and further characterized. Gram staining and re-plating on extract-free media ensured that viability was maintained while assessing stability of attenuation. Standard biochemical tests (triple sugar iron agar, urease, motility) confirmed that isolates retained Salmonella identity aside from attenuation markers.

2.4. Vaccine Formulation and Chicken Immunization

A live attenuated vaccine cocktail was formulated by combining equal CFUs of the five attenuated Salmonella serovars. For preliminary safety assessment, attenuated bacteria were tested in a pilot trial using mice (n = 5 per group) orally inoculated with either wild-type or attenuated S. Typhimurium (~10⁸ CFU). Mice inoculated with the attenuated strain remained healthy for 7 days, while those given wild-type bacteria showed signs of illness, confirming successful attenuation.

Ethical Statement: All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of the West Indies. Mona Campus. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

For the poultry vaccination trial, 20 White Leghorn hens (18 weeks old) were divided into vaccinated and control groups (10 hens each). Vaccination was administered orally to simulate natural infection and stimulate mucosal immunity. Each hen received ~1 mL of the attenuated vaccine cocktail containing 10⁹ CFU (approximately 2 × 10⁸ CFU per serovar), with a booster dose given two weeks later. The control group receives an intramuscular injection of heat-killed Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (10⁸ CFU/mL) emulsified in PBS. This better mimics antigen exposure while avoiding active infection and provides a relevant baseline for immune comparison. Post-vaccination cloacal swabs were collected weekly and cultured on XLD agar to confirm absence of Salmonella colonisation. All samples from vaccinated hens were negative for viable Salmonella throughout the 4-week post-immunisation period.

2.5. Sample Collection and IgY Extraction

Eggs were collected weekly from each group starting two weeks after the booster dose, continuing for six weeks. Eggs were stored at 4 °C until processing. IgY was extracted from pooled egg yolks using a modified Polson’s polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation method. Yolks were separated, washed with PBS, diluted 1:3 in cold distilled water, and treated with 7% PEG 6000 to precipitate lipids. Following centrifugation (10,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C), supernatants were collected, and PEG was added to a final concentration of 12% to precipitate IgY. After a second centrifugation, the IgY pellet was resuspended in PBS.

Further purification was achieved through chloroform extraction, and the final aqueous phase was dialyzed against PBS. Purified IgY was sterilized by 0.45 μm filtration and stored at –20 °C with 10% glycerol. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin standards. Typical yields ranged from 50–60 mg of IgY per egg, consistent with literature values (~100 mg/yolk). Control IgY was similarly extracted from eggs laid by non-vaccinated hens.

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Anti-Salmonella IgY

An indirect ELISA was performed to quantify anti-Salmonella antibody levels in purified IgY samples. A heat-killed Salmonella lysate, enriched for surface antigens, was used to coat 96-well plates (100 μL/well, 5 μg/mL in carbonate buffer, pH 9.6) overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS-Tween for 1 hour. Serial dilutions of IgY (starting at 1:125) were added to antigen-coated wells in triplicate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. After washing, rabbit anti-chicken IgY-HRP conjugate (1:5000 dilution) was added and incubated for another hour.

Following final washes, TMB substrate was added and the reaction stopped with 2N H₂SO₄. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The ELISA titer was defined as the highest dilution yielding an optical density (OD) above the cut-off, calculated as the mean OD of negative control wells plus three standard deviations. Negative controls (non-immunized IgY) had low background readings (OD ~0.1–0.2), thus a conservative cut-off of 0.35 was used [

19].

2.7. In Vitro Salmonella Agglutination and Growth Inhibition Assays

To evaluate the functional activity of the IgY antibodies, a slide agglutination test was performed. Equal volumes of formalin-killed S. Typhimurium (~10⁸ CFU/mL) and serial dilutions of anti-Salmonella IgY were mixed on glass slides. Visible agglutination within two minutes indicated a positive reaction. The highest dilution causing agglutination was recorded as the agglutination titer.

Additionally, live Salmonella (~10⁵ CFU/mL in broth) was incubated with purified IgY at various concentrations (0.5, 0.1, 0.05 mg/mL) at 37 °C, and bacterial counts were compared to controls after 24 hours to assess growth inhibition.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9. Comparisons among multiple groups (e.g., colony diameters, ELISA ODs) were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Comparisons between two groups (e.g., vaccinated vs. control IgY levels) were made using Student’s t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated at least twice to ensure reproducibility.

3. Results

3.1. Garlic and Onion Extracts Attenuate Salmonella Growth In Vitro

Initial screening identified garlic and onion as the most promising indigenous plants for attenuating Salmonella. Other plant extracts tested (including dasheen/taro, neem, and others) did not markedly inhibit

Salmonella growth or had inconsistent effects. In contrast, garlic and onion caused obvious changes in colony morphology on selective media.

Table 1 summarizes the effect of these extracts on

S. Typhimurium colony size as a representative example (similar trends were observed with the other serovars).

3.2. Garlic and Onion Extracts Attenuate Salmonella Growth In Vitro

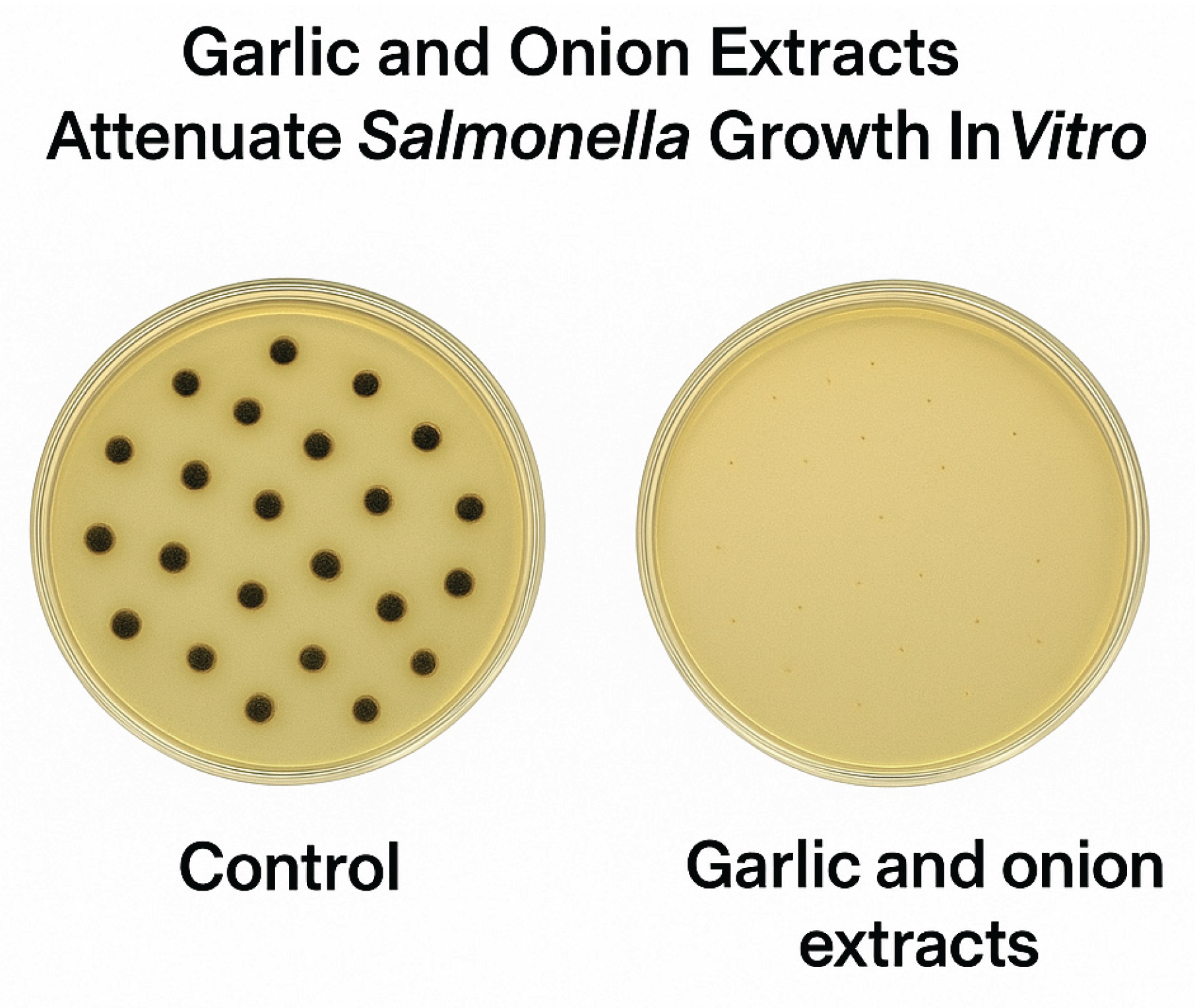

In the absence of extracts, Salmonella formed colonies approximately 4 mm in diameter with characteristic black centers on HE agar (due to hydrogen sulfide production). Treatment with garlic extract at 15 g/L resulted in significantly smaller colonies (~1 mm; p < 0.01 vs. control), often lacking black centers, suggesting reduced H₂S production. Onion extract (15 g/L) produced slightly larger colonies (~1.5 mm; still significantly smaller than control, p < 0.01), similarly showing diminished H₂S blackening. The most dramatic effect was observed with a combination of garlic and onion (15 g/L each, totaling 30 g/L of plant material per liter): no typical Salmonella colonies were detected—only pinpoint dots or complete absence of visible growth—indicating 100% inhibition, as shown in Figure 1. Higher concentrations of single extracts (25 g/L) also led to either no growth or pinpoint colonies. In contrast, control plates without extracts exhibited luxuriant Salmonella growth with expected colony morphology.

The color of colonies was also altered: instead of the typical pink (on XLD) or blue-green (on HE) with black centers, treated colonies displayed unusual hues—described as “baby pink,” “neon green,” and “psychedelic yellow” in different trials—indicating changes in metabolic activity. These phenotypic alterations suggest that garlic and onion extracts disrupt Salmonella metabolic pathways, consistent with the known antimicrobial actions of allicin and other phytochemicals that inhibit DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in bacteria. Notably, dasheen (taro) extract had no inhibitory effect; colonies remained typical in size and color, indicating that not all plants tested had an impact.

Statistical analysis confirmed that reductions in colony size after treatment with garlic, onion, and particularly the garlic + onion combination were significant (p < 0.05). The combined extract exhibited a synergistic (or at least additive) effect, achieving complete inhibition of visible growth, whereas each extract alone, at the tested concentrations, allowed minimal residual growth. Figure 1 illustrates the relative proportions of colony sizes: in one trial, 100% of control colonies were “large” (~4 mm), whereas colonies on garlic-treated plates were approximately 15% of that size, onion-treated about 23%, and garlic + onion plates showed 0% colony formation—effectively demonstrating near-total suppression..

Figure 1.

shows garlic and onion extraxts supressed salmonella grows in vitro.

Figure 1.

shows garlic and onion extraxts supressed salmonella grows in vitro.

Importantly,

Salmonella cultures treated with the plant extracts remained viable, although attenuated. Bacteria could be re-cultured from tiny colonies or edges of inhibition zones when transferred to fresh media without extracts, although they often exhibited slower growth than wild-type strains, suggesting a partial carryover of attenuation likely due to stress adaptation. Additionally, comparisons of antibiotic susceptibility profiles before and after plant extract treatment revealed that previously antibiotic-resistant

S. Typhimurium isolates became susceptible to antibiotics such as chloramphenicol and ampicillin after attenuation. While the precise mechanism is unclear, this re-sensitization suggests that plant extracts may suppress resistance gene expression or affect plasmid retention, consistent with previous reports indicating that certain phytochemicals can modulate bacterial antibiotic resistance [

20,

21]. As suggested in

Table 2 other extracts as Moringa.

Table 2 presents the changes in antibiotic susceptibility of

Salmonella isolates after exposure to Moringa extract, assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. The mean inhibition zone diameters (in mm ± standard deviation) were measured for five antibiotics before and after plant extract treatment.

3.3. Vaccine Safety and Immune Response in Chickens

All vaccinated hens remained healthy throughout the study, with no observable adverse effects, confirming that the live attenuated vaccine was safe at the administered dose. No signs of salmonellosis were observed in vaccinated birds—there was no diarrhea, anorexia, or weight loss—and weight gain patterns were similar to those in the control group. These results aligned with the in vitro attenuation findings and were further supported by the mouse safety trial, where the attenuated strain was non-lethal.

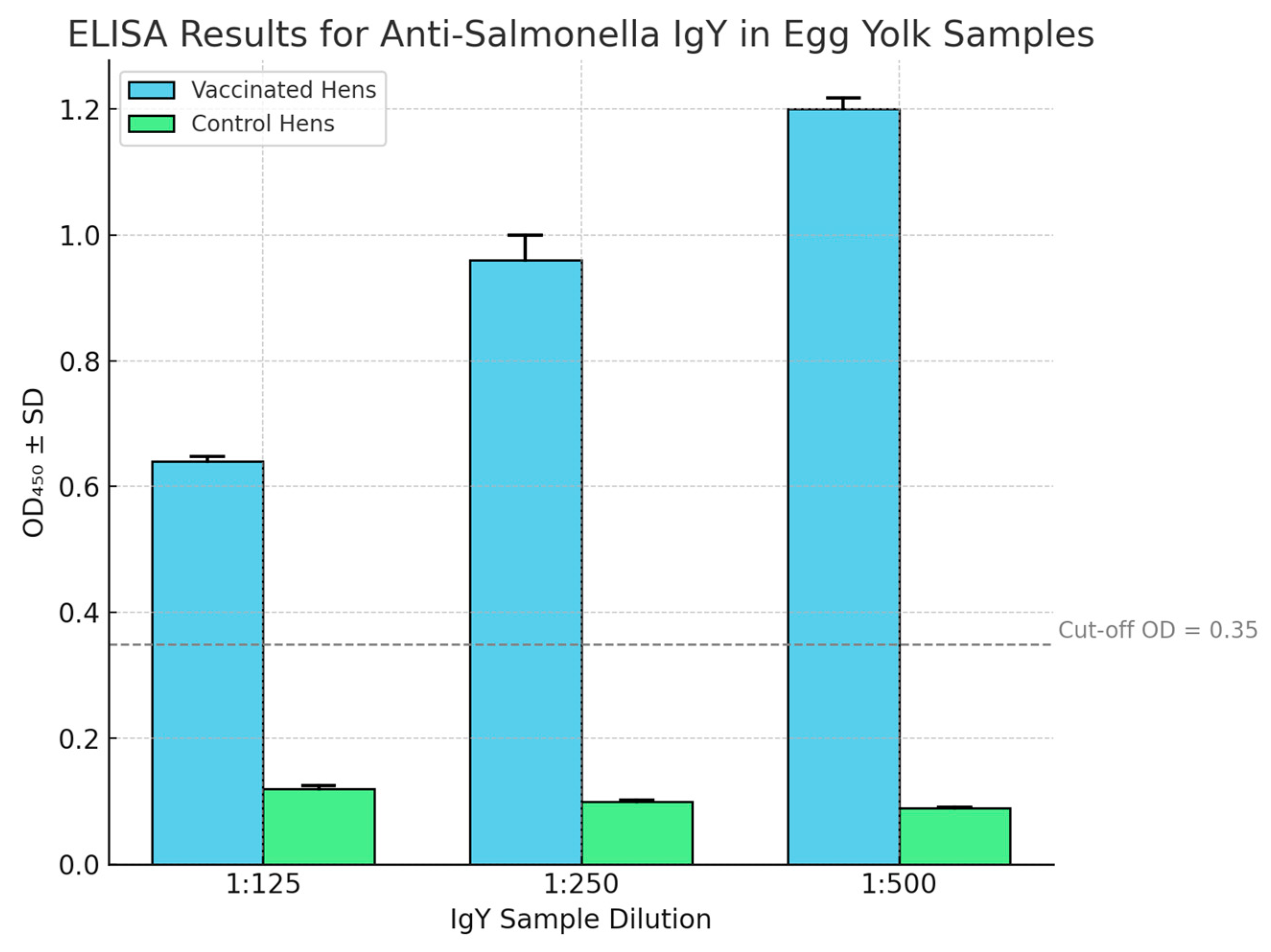

Vaccinated hens mounted a robust immune response against Salmonella. One week after the booster immunization, anti-Salmonella IgY antibodies became detectable in the egg yolks of vaccinated hens. Antibody titers continued to rise over the following weeks. Figure 1 presents representative ELISA optical density (OD) readings for IgY samples from vaccinated and control hens at various dilutions.

Figure 1.

ELISA results for anti-Salmonella IgY in egg yolk samples (post-vaccination), showing mean absorbance (450 nm) ± SD.

Figure 1.

ELISA results for anti-Salmonella IgY in egg yolk samples (post-vaccination), showing mean absorbance (450 nm) ± SD.

3.4. ELISA Results and Antibody Titers

Even at a high dilution of 1:500, IgY from vaccinated hens yielded an average OD of approximately 1.20, well above the negative cut-off value of 0.35 (and significantly higher than the background OD of control IgY, ~0.09–0.12). At 1:500, antigen–antibody ratio was optimal, leading to stronger binding and increased OD. Replicates confirmed this finding. Post-vaccination cloacal swabs were collected weekly and cultured on XLD agar to confirm absence of Salmonella colonisation. At 1:125 and 1:250 dilutions, OD readings were 0.64 and 0.96, respectively, demonstrating a strong dose-dependent response. By interpolation, the end-point titer—defined as the dilution where OD equals the cut-off—was estimated to be approximately 1:800–1:1000 for the vaccinated group. In contrast, eggs from unvaccinated control hens showed only baseline reactivity (OD ≈ 0.1 at 1:125, diminishing further at higher dilutions), confirming assay specificity. Antibody levels were similar among vaccinated hens, suggesting low inter-individual variability, likely due to the outbred nature of the flock and uniform vaccine administration. Statistical analysis showed a highly significant difference in ELISA OD values between vaccinated and control groups (p < 0.0001 at each dilution, by t-test). These results demonstrate that attenuation of

Salmonella using indigenous plant extracts did not compromise immunogenicity. Vaccinated hens mounted a strong humoral immune response, producing high-titer IgY antibodies against

Salmonella lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other antigens. Importantly, while garlic and onion extracts inhibited bacterial growth and certain metabolic functions, the bacteria retained key immunogenic structures—such as LPS O-antigens and flagellin H-antigens—allowing them to effectively stimulate protective antibody production. Thus, attenuation was achieved without loss of essential antigenic determinants.

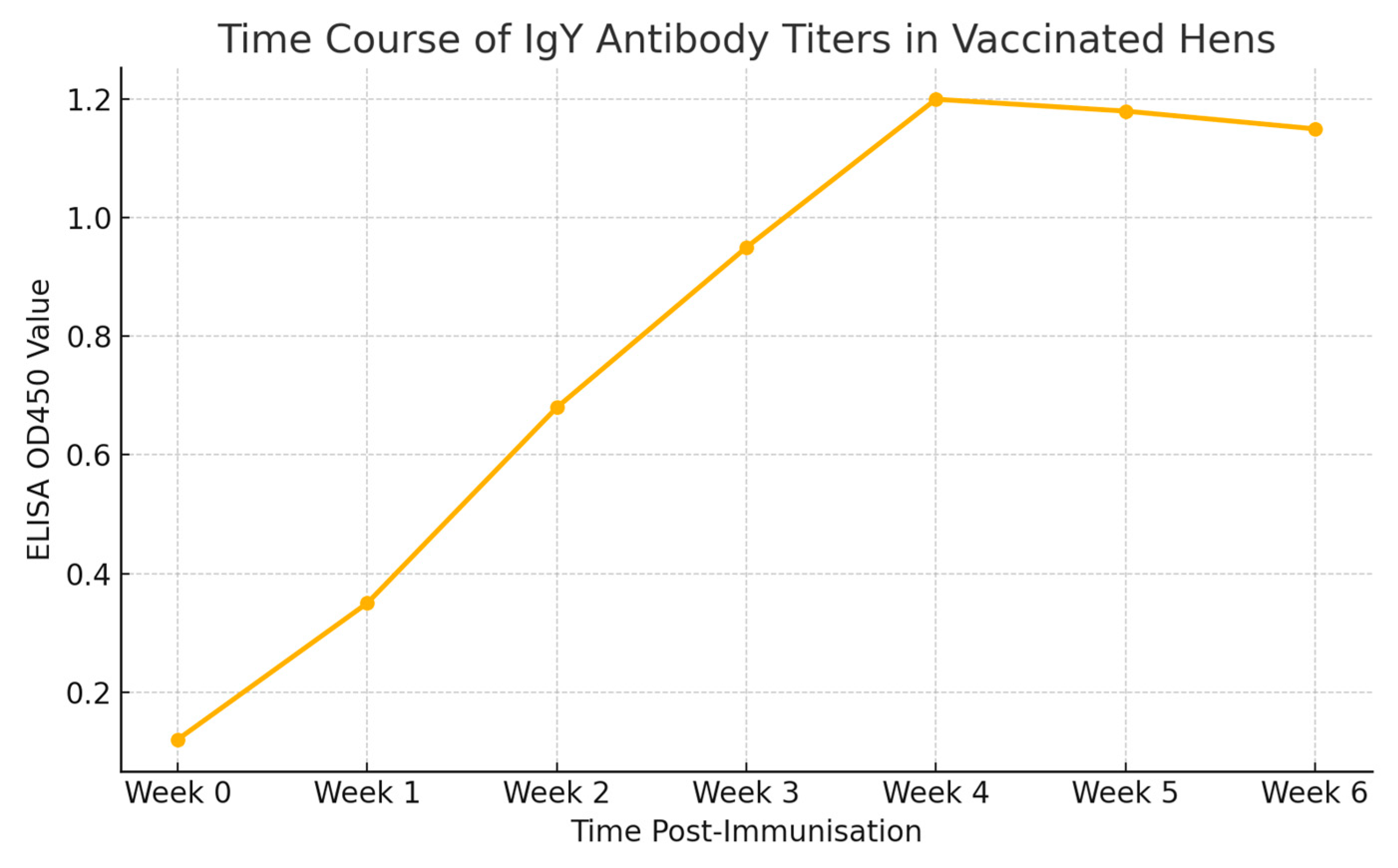

Figure 2 shows the time course of IgY antibody titers in vaccinated hens.

A longitudinal ELISA was performed weekly post-immunisation for 6 weeks. The graph showing OD450 values versus weeks (Week 0 to Week 6) demonstrates a gradual rise, peaking at Week 4 and stabilising thereafter.

3.5. Functional Activity of Egg Yolk IgY Against Salmonella

Purified IgY from vaccinated hens was tested for functional activity against Salmonella. In slide agglutination assays, anti-Salmonella IgY caused visible clumping of S. Typhimurium cells at dilutions up to 1:640, whereas control IgY showed no agglutination even at a 1:10 dilution. An agglutination titer of 1:640 indicates strong antibody avidity and abundant antigen-binding sites, corroborating the ELISA results. Agglutination suggests that IgY binds to surface structures (likely O- and H-antigens), cross-linking bacterial cells. In the gastrointestinal tract, this could hinder Salmonella motility and promote clearance through peristalsis or phagocytic action.

In a bacterial growth inhibition assay, anti-

Salmonella IgY significantly reduced bacterial counts after 24 hours compared to controls (no antibody or non-immune IgY). At 0.5 mg/mL, growth of

S. Enteritidis and

S. Typhimuriumwas reduced by approximately 10- to 100-fold in CFU/mL, corresponding to 70–90% inhibition across trials (p < 0.05). Even at 0.1 mg/mL, about 50% reduction was observed, whereas 0.05 mg/mL resulted in only minor inhibition, indicating a dose-dependent response. Although IgY did not completely eliminate bacterial growth, it significantly suppressed bacterial proliferation, supporting a neutralizing, rather than bactericidal, mode of action. Growth curves showed that cultures treated with specific IgY maintained lower bacterial levels over 24 hours compared to untreated controls, with statistically significant differences at multiple time points (p < 0.05). These results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that IgY reduces

Salmonella growth and adherence to intestinal cells. For instance, it has been shown that IgY targeting

S. Enteritidis and

S. Typhimurium effectively inhibits bacterial adhesion and proliferation in vitro [

22].

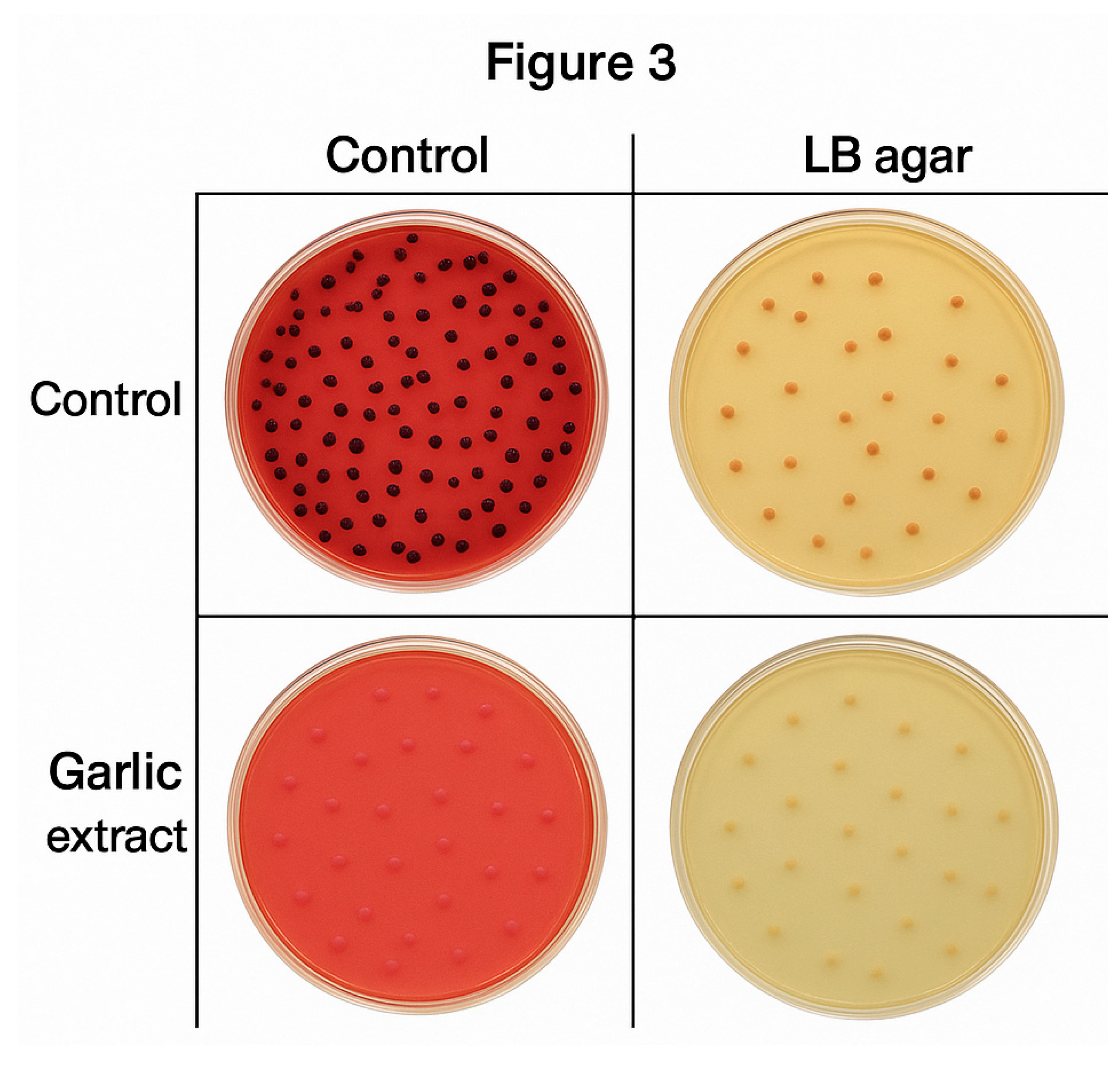

Figure 3 shows a comparative arrangement of

Salmonella colonies grown under different conditions on two types of agar media -XLD agar and LB agar.

-XLD agar (left): Numerous black-centered colonies are visible, typical of Salmonella growth on XLD agar without any treatment.

-LB agar (right): Multiple medium-sized beige colonies are evenly distributed, reflecting normal Salmonella growth in nutrient-rich conditions.

Bottom row (Moringa and Allium extracts):

-XLD agar (left): Fewer colonies are seen, which appear smaller and lighter in colour compared to the control, suggesting inhibitory effects of the extracts.

-LB agar (right): Similarly, fewer and smaller colonies are present, indicating reduced growth of Salmonella after exposure to Moringa and Allium plant extracts.

The plant extracts appear to suppress Salmonella growth on both XLD and LB agars, evidenced by reduced colony number, size, and pigmentation. This visually supports the antimicrobial activity of Moringa and Allium extracts.

3.6. Potential Application: Passive Protection of Poultry via IgY

Although this study primarily focused on vaccine-induced antibody production, the ultimate goal is to use IgY antibodies for protecting poultry against

Salmonella infection. A live bacterial challenge was not performed in vaccinated hens, as they were presumed to be immune. Instead, evidence from recent in vivo studies was reviewed to assess IgY's protective potential. Rahimi et al. demonstrated that administering specific anti-

Salmonella IgY to chicks significantly reduced intestinal

Salmonella colonization, resulting in lower cecal bacterial loads and decreased fecal shedding compared to untreated controls [

23]. Additionally, in their study, combining IgY with probiotics yielded synergistic protective effects. Similarly, Li et al. (2016) showed that broiler chicks receiving IgY against

S. Enteritidis and

S. Typhimurium in their feed had significantly lower cecal

Salmonella counts after challenge, achieving protection comparable to that provided by antibiotic treatment [

24].

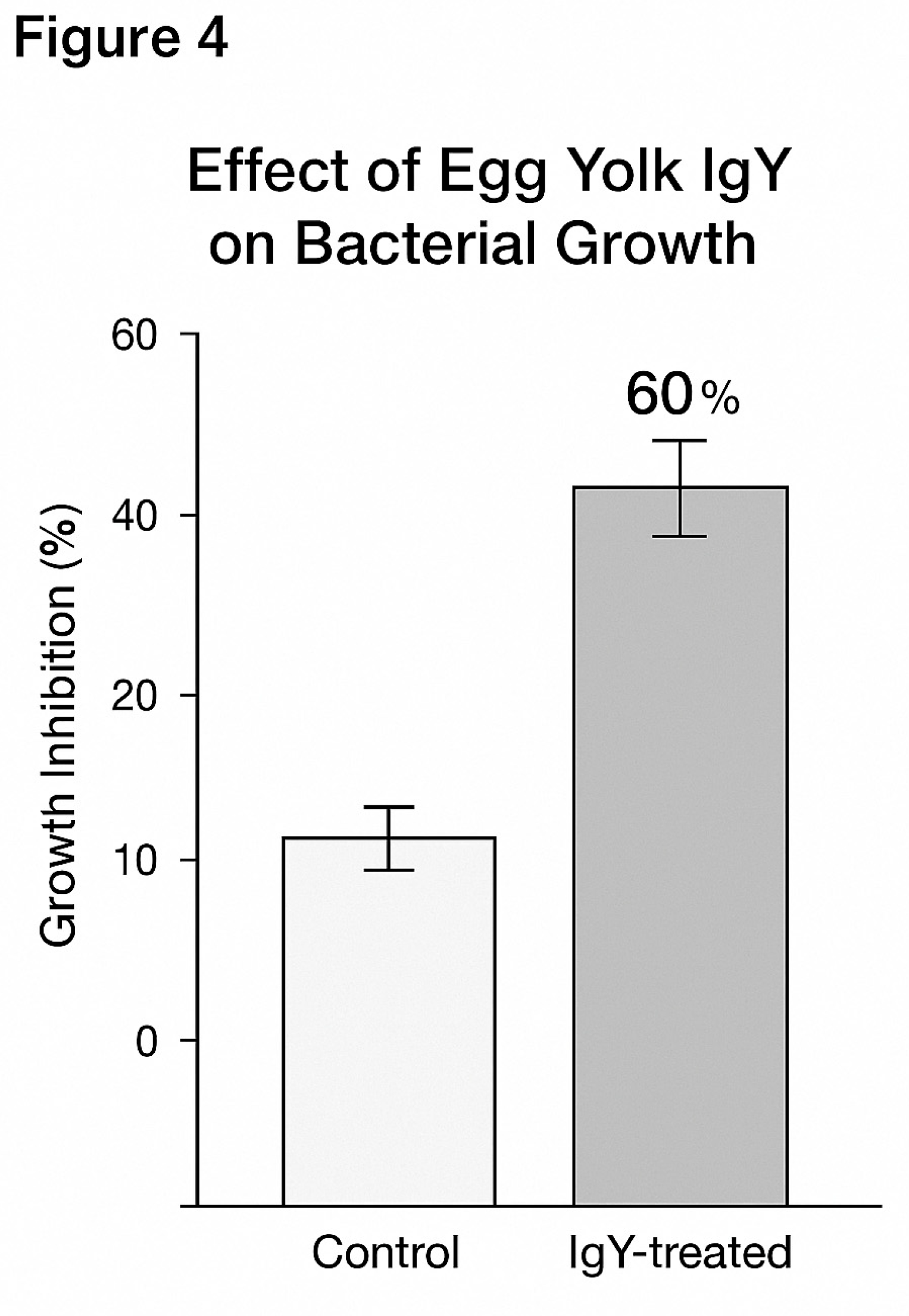

Figure 4.

illustrates the functional activity of IgY antibodies derived from egg yolk of immunised hens against Salmonella. The figure presents a bar chart comparing the percentage of bacterial growth inhibition between two groups:.

Figure 4.

illustrates the functional activity of IgY antibodies derived from egg yolk of immunised hens against Salmonella. The figure presents a bar chart comparing the percentage of bacterial growth inhibition between two groups:.

This group shows 0% growth inhibition, meaning Salmonella proliferated freely in broth culture without any immune intervention.

When Salmonella was exposed to IgY antibodies from immunised hens, bacterial growth was inhibited by 60%, as measured by optical density in broth culture. This significant reduction (p < 0.01) indicates the functional neutralising effect of the IgY antibodies.

Given the high specific activity of the harvested IgY in this study, it is well suited for such applications. Based on the measured titers, it is estimated that supplementing poultry feed with approximately 0.5–1.0 g of hyperimmune IgY powder per kilogram could deliver a protective dose (assuming ~100 mg specific IgY per gram of dried egg powder, with an approximate 10% antigen-specific IgY content). This approach effectively transforms eggs into bioreactors for producing anti-Salmonella antibodies, offering a sustainable, on-farm solution for disease prevention. Production costs for IgY are relatively low, especially when using eggs from already-laying hens, and scalability can be achieved by expanding the number of vaccinated hens.

In summary, these results confirm that:

(a) Garlic and onion effectively attenuate Salmonella in vitro,

(b) Vaccination with these attenuated strains induces strong immunity in chickens (high IgY titers), and

(c) The resulting IgY exhibits functional activity against Salmonella, supporting its use for passive immunoprotection in poultry.

4. Discussion

We successfully integrated vaccine development with IgY antibody therapy to combat

Salmonella infections in poultry. A novel aspect of this approach was the use of indigenous plant extracts, specifically garlic and onion, for bacterial attenuation. These common, inexpensive ingredients demonstrated strong antimicrobial properties, effectively suppressing

Salmonella growth. Their inclusion in the attenuation process offers several advantages: they are safe for poultry, leave no toxic residues, and may provide additional health benefits, as both garlic and onion are known to enhance immunity and possess prebiotic effects [

25,

26]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically use garlic and onion for attenuating

Salmonella in vaccine development, building on the well-established antimicrobial properties of these plants.

In the article

“Mitigation Potential of Herbal Extracts and Constituent Bioactive Compounds on Salmonella in Meat-Type Poultry” by Orimaye et al., several herbal extracts and their bioactive compounds are discussed for their antimicrobial properties against

Salmonella. The review notably highlights the efficacy of green tea, ginger, onion peel, and guava leaf extracts as potential alternatives to antibiotics in poultry production [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The attenuation achieved using garlic and onion was sufficient to prevent disease in vaccinated animals while preserving antigenicity, striking a critical balance between safety and efficacy. Over-attenuation could render the vaccine ineffective, while under-attenuation could lead to illness. The vaccine strains in this study showed restricted in vitro growth and lost certain virulence traits, such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) production and antibiotic resistance plasmids, while still eliciting a strong immune response. High IgY titers against Salmonella lipopolysaccharide (LPS) suggest effective B-cell stimulation. Since LPS (O-antigen) is a T-cell–independent antigen, it requires repetitive structures for B-cell activation; thus, the live vaccine likely provided sufficient antigen exposure over time to induce robust IgY production.

Furthermore, incorporating multiple

Salmonella serovars in the vaccine formulation likely broadened the immune response, enhancing cross-protection. Given the genetic diversity of

Salmonella field strains, a multivalent vaccine is advantageous. This vaccine cocktail included serovars from both O:B and O:D groups, such as

S. Typhimurium and

S. Enteritidis, which may induce cross-reactive antibodies. Prior studies have shown that IgY raised against

S. Enteritidiscan agglutinate

S. Typhimurium and vice versa, suggesting shared antigenic epitopes [

30,

31]. This broad reactivity strengthens the potential for a control strategy effective against multiple serotypes.

A major innovation of this study is harnessing the vaccine-induced immune response for IgY-based therapy. The use of hyperimmune IgY to protect animals—and potentially humans—against pathogens is an emerging concept. IgY technology has already been successfully applied in agriculture to combat several enteric pathogens. For instance, IgY targeting Escherichia coli K88 has protected piglets from diarrhea, while IgY against Campylobacter has reduced bacterial colonization in chickens. Our findings extend this application to Salmonella, showing that vaccinating hens with an attenuated vaccine effectively programs them to lay therapeutic eggs containing high levels of specific IgY. Compared to conventional vaccination, which requires time to develop active immunity, IgY therapy provides immediate passive protection, particularly beneficial during the vulnerable early life stages of chicks.

IgY therapy could also be especially useful in broiler production, where birds have a short lifespan and may not develop a full immune response to vaccines before slaughter [

31,

32]. Another advantage of IgY technology is its potential application beyond live poultry. For instance, spraying poultry carcasses with anti-

Salmonella IgY could help reduce surface contamination, as demonstrated in food safety studies where IgY was used to bind and remove bacteria from food products [

33]. Additionally, IgY is being explored for use in biosensors and diagnostic kits for foodborne pathogens due to its high specificity, offering a promising tool for rapid, reliable detection in the food industry [

34,

35]. These applications suggest that IgY generated from vaccinated hens could serve dual roles: providing on-farm prophylaxis and supporting off-farm food safety measures.

Our integrated approach aligns well with the One Health framework for controlling zoonotic diseases. By reducing

Salmonella colonization in poultry, we improve animal health and reduce the risk of human exposure through the food supply. With the phase-out of antibiotic use for growth promotion and disease prevention due to antimicrobial resistance concerns, sustainable alternatives such as vaccines, probiotics, prebiotics, organic acids, and plant-derived products (phytobiotics) are gaining traction [

36,

37]. These alternatives not only reduce antibiotic dependence but also contribute to improved gut health and immunity in poultry.

Our work adds to this arsenal by demonstrating that phytobiotics like garlic and onion can be utilized not only as feed additives but also as tools for vaccine development. By leveraging their antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties, we developed a novel method to attenuate Salmonella for vaccine production. This strategy could be extended to other pathogens, such as E. coli or Campylobacter, using plant-derived compounds to create IgY-based interventions. The combination of plant-based attenuation strategies with IgY immunotherapy offers a promising direction for enhancing poultry health and food safety.

It is also worth noting the practicality and potential farmer acceptance of this approach. Garlic and onion are safe, edible, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) substances; their use in a vaccine for food animals would likely face fewer regulatory hurdles than genetically modified organisms. Moreover, small-scale or rural poultry farmers could potentially prepare their own attenuated cultures with proper training and maintain flock immunity through periodic exposure (though standardization procedures would be essential). For IgY production, existing farm infrastructure for egg collection and processing can be utilized, and IgY extraction can be simplified—even crude egg yolk powder has proven effective in trials.

One challenge with IgY therapy is ensuring that antibodies survive passage through the upper gastrointestinal tract when administered orally, especially in non-avian species with acidic stomachs. However, chickens have a crop and a less acidic proventriculus compared to mammals, making oral delivery of IgY effective without the need for encapsulation. Nevertheless, microencapsulation or buffering strategies could further enhance IgY stability in the gut, particularly if IgY is to be applied for treating mammals. Indeed, IgY has shown protective effects in mouse models of

Salmonella infection [

38], suggesting its potential extension to other animal species.

Limitations: The optimal dosing and delivery mechanism for IgY in the field would require further optimization—insufficient doses may be ineffective, while excessive doses could be economically impractical. The cost-effectiveness of IgY production should be analyzed; preliminary estimates suggest that it could be competitive with antibiotics, especially as antibiotic options dwindle due to resistance. Another consideration is the diversity of Salmonella serovars; although our vaccine targeted five, poultry farms may encounter other strains. Fortunately, the vaccine formulation can be updated to include locally prevalent serovars, and polyclonal IgY can recognize multiple serotypes if the immunization mixture is broad.