Introduction

Humans, since the consciousness developed, have had been looking for and acting according to the existing differences in the nature. It has been the nature of the society to look into these differences and then assign roles accordingly. All this has resulted into emergence of social issues in society. The same dictum is reflected in the economic system of management, wherein the tasks are being given, assigned or run according to the naturally existing distinctions among the task force. Considering, Gender as one of the main ingredients among these differences, many social issues stemming from Gender Biases and Gender Inequality have raised their heads in the economic system. “Gender refers to socially constructed characters and opportunities available to men and women based on cultural beliefs or norms which are different from their biological characters” (Adegbite and Machethe 2020). It is viewed as “an ideological and cultural construct” which “is reproduced within the realm of material practices and which in turn also influences the outcomes of such practices” (Adegbite and Machethe 2020). Gender differences, hence, have had been governing the nature of economic activity since the time of realization of such differences. The studies so far confirm the relationship between Gender and economic activity across the globe and consider economics as a gendered process (Bertay, Dordevic, and Sever 2020). Same is true for the United States. Women are a driving force in the American economy, as their labor market gains and spending increased in 2023. However, there are still gender-related economic inequalities in the US which greatly impact the US economy. “In 2022, working women lost more than $1.6 trillion due to the gender wage gap, which is equivalent to 6.3% of the US GDP. Women also make up 67.9% of workers earning the federal minimum wage, which has been $7.25 since 2009”. Further, “the gender wealth gap” is more than “the gender wage gap, with families headed by women having 55 cents in median wealth for every dollar owned by families headed by men” (Keka 2025). These figures reflect a general scenario of existence of issues stemming from gender linked differences for the American economy. Research has been following these issues since the realization of their existence and trying to study the channels through which they impact the American economy. The most of the research is directed towards examination of gendered income inequalities in various fields however, little literature has explored or linked gender with artistic careers. This research is aimed at bridging this Gap.

Research Aim

The research aims to explore the state of full-time employment of Artists and related workers (16 years and over) in America in terms of gender related impact factors. The paper, therefore, aims to analyse how factors like gender gap in artist gender ratio by year, full-time employment of women artists and related workers (16 years and over) and percentage of full-time employment of women artists and related workers out of full-time employment of Artists and related workers impact the full-time employment of Artists and related workers (16 years and over) in America. The purpose here is to trace out existence of long run, if any, relationship between variables.

The time series analysis for the years 2010 to 2021 is done with the help of ARDL model and concerned descriptive analysis. The aim is to examine the nature of existing policies on gender related issues and suggest changes, if need be, for future American policy.

Literature Review

There have had been extensive research on examination gender roles in various fields across the globe (Swaminathan, Lahoti, and Suchitra 2012; Çagatay 1998; Mndolwa and Alhassan 2020; Ghosh and Chaudhury 2019; Elson and Seth 2019; UNECE 2010; D’Acunto, Malmendier, and Weber 2021; Bertay, Dordevic, and Sever 2020). Studies have tried to establish gender as a key factor behind sustainable economic growth. Such studies highlight that gender equality plays active role in achieving inclusive growth (Elson & Seth, 2019). Further, specific literature tries to examine issues of Gender and Employment (Dex, 1988) and tries to figure out the existence and causes behind the existence of gender issues including gender and wage gap in almost all the occupations of the society (Hegewisch and Ellis 2020). There have had been extensive research when it comes to study of relationship between income and gender (Gap, Causes, and Gap 2023; Lindemann, Rush, and Tepper 2016). Further, from theoretical view point, Gender Gap, Gender Disparity have emerged as some of the important concepts in the theory of economy research. The studies have also explained the impact of such differences on the working of either economic system as a whole or in the different sectors of the economy. There has been extensive research on how the gender inequalities in the employment work impact the nature of economic activity (UNECE 2010).

Studies have also tried to explore gender in the field of artistic occupations in America. The research in the art field gained momentum following the exposure of underrepresentation of women artists in famous museums and galleries of America by the Guerrilla Girls, a feminist arts activist group in the 1980s. The research has moved on from examination of differential association between labor market factors and gender wise incomes in the arts (Lindemann, Rush, and Tepper 2016) to analysis of ‘gender politics in smaller institutions’ in America (Casey 2016). The work have also been directed towards examination of how ‘gender implicitly organizes social expectations around artists and artistic work’ (Miller 2016). Researchers have been trying to figure out the existence of and nature of gender inequalities in employment of artists.

However, little research has been done in direction of studying of relationship between gender gap and various other gender linked factors on the employment of artists in the American economy. Keeping in mind the importance of gender in economics and employment, this research aims to bridge this gap by studying the relationship between such variables.

Data and Research Methodology

Data

Research has used secondary data sources and try to trace out the trends of the variables for the American Economy for the years 2010 to 2021. The data is taken from Federal Reserve Economic Data, Open Data Watch and the Zippia online data.

Variables Chosen

Employment of Artists and Related workers: Employment of Artists and related workers (16 years and over) in America is chosen as dependent variable and the impact of other variables will be studied on this variable. The purpose is to trace out the validity of existence of long run relationship between Employment of Artists and Related workers and the variables impacting them. The data for this dependent variable is taken from Federal Reserve Economic Data and it explains annual, not seasonally adjusted full time employment of artists and workers in the American Economy.

Gender gap in annual artist gender ratio: the artist gender ratio data for females and makes have been taken from Zippia online data base. “Zippia estimates artist demographics and statistics in the United States by using a database of 30 million profiles”. The independent variable chosen for the study is percentage gender gap in annual artist gender ratio for the said years by using the following formula-

Full time employment of women artists and related workers (16 years and over): Full time employment of women artists and related workers (16 years and over) is another independent variable chosen for the study. The data is chosen from Federal Reserve Economic Data. This variable is chosen to know how employment of women shape the very nature of employment scenario of the artists in the American economy as a whole.

Percentage of full time employment of women artists and related workers out of full time employment of Artists and related workers: Percentage of full time employment of women artists and related workers out of full time employment of Artists and related workers data has been taken from the Federal Reserve Economic Data. This independent variable is used to know the impact of women representation out of total representation on the employment structure of artists in the American economy.

Methodology

This study conducts econometric analysis by using Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model. It is used to study the cointegration relationship between Employment of Artists and related workers (16 years and over) in America (dependent variable) and various impact factors (independent variables). “The ARDL bound test method capture the dynamic effects of lagged” independent variables and lagged dependent variables. The paper will provide results based on Regression Analysis, Content Analysis and Descriptive Analysis.

ARDL Model

Following ARDL model is used to study relationship between the variables:

Hypothesis-

No existence of cointegration

Existence of cointegration

Bound Test

The bound Test was conducted using software Eviews. “The ARDL bound test approach is used to test the presence of the long run relationship among the variables by conducting the F-test. If the calculated F-statistics is greater than the critical value of the upper bound I(1), then we conclude that there is co-integration”.

Here, should be negative and significant to ensure stability of long run relationship.

Results and Findings

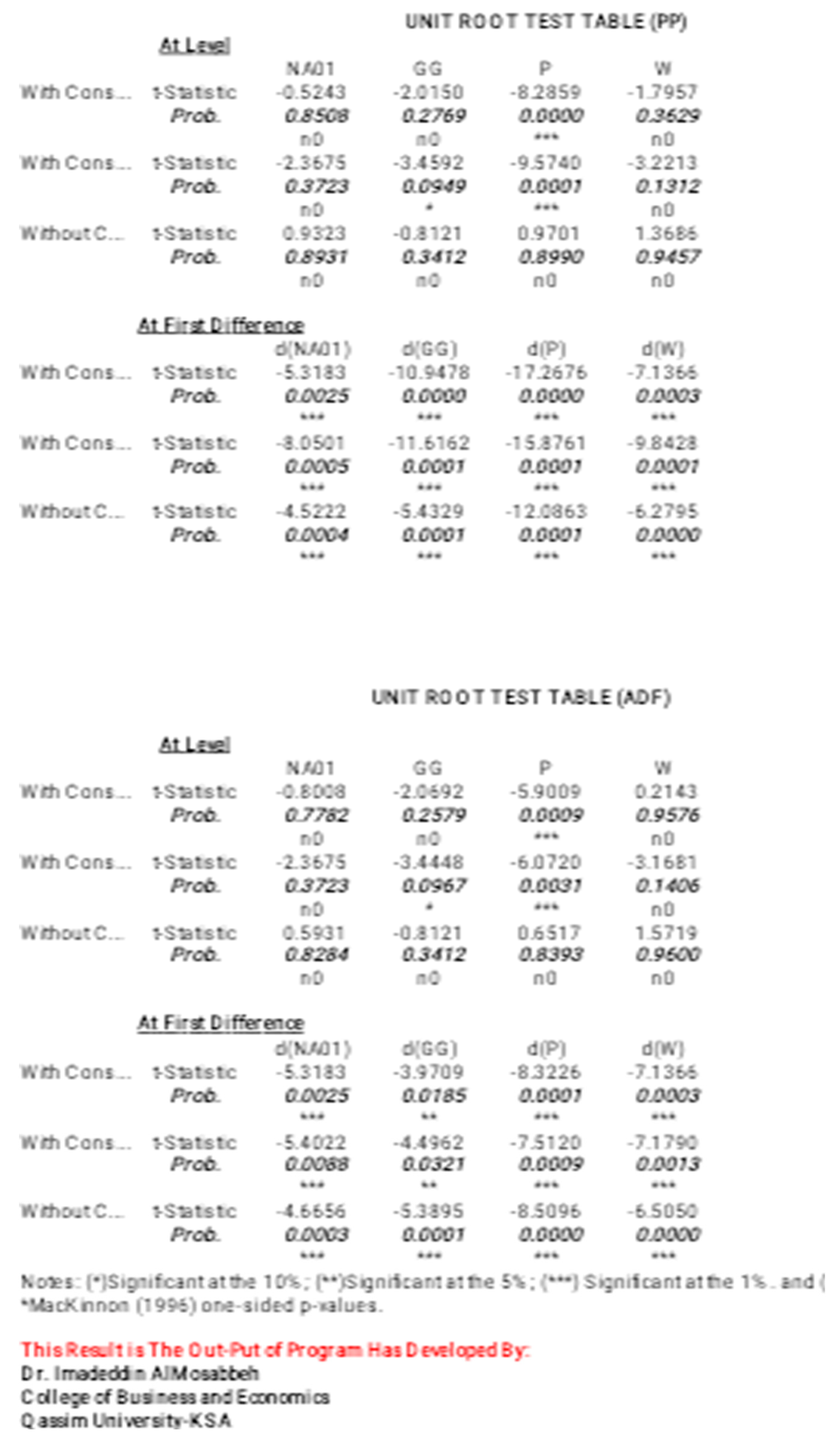

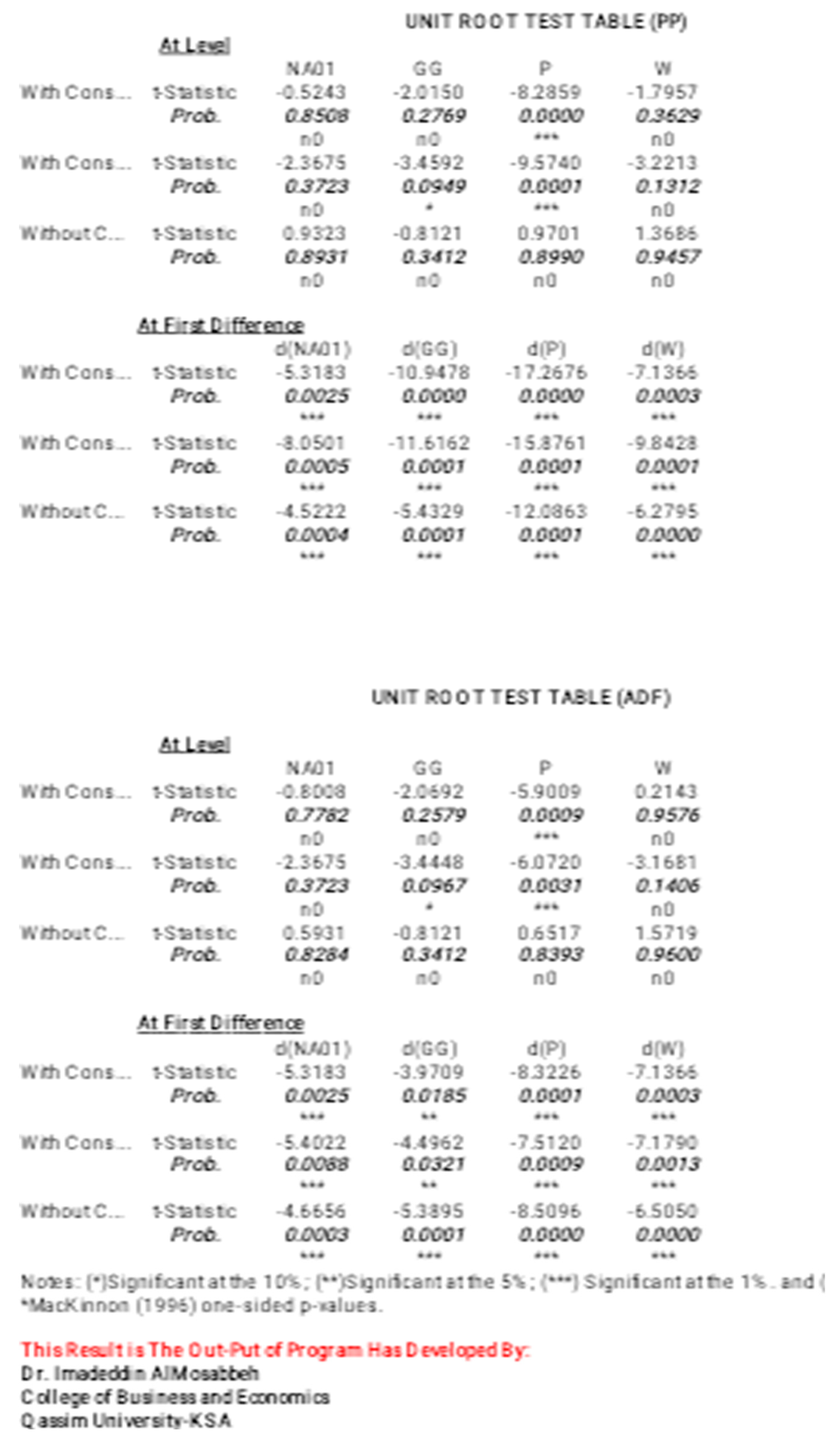

It is important to approve the conditions of applying the ARDL model that is all the variables in the model are either stationary at “I(0) or I(1) or combination of both”. To ensure this, unit root tests- Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and Phillips-Perron (PP) test have been employed. The results of the same (

Table 1) confirm that the variables are stationary at first difference. Therefore, it is viable to run ARDL model of econometrics.

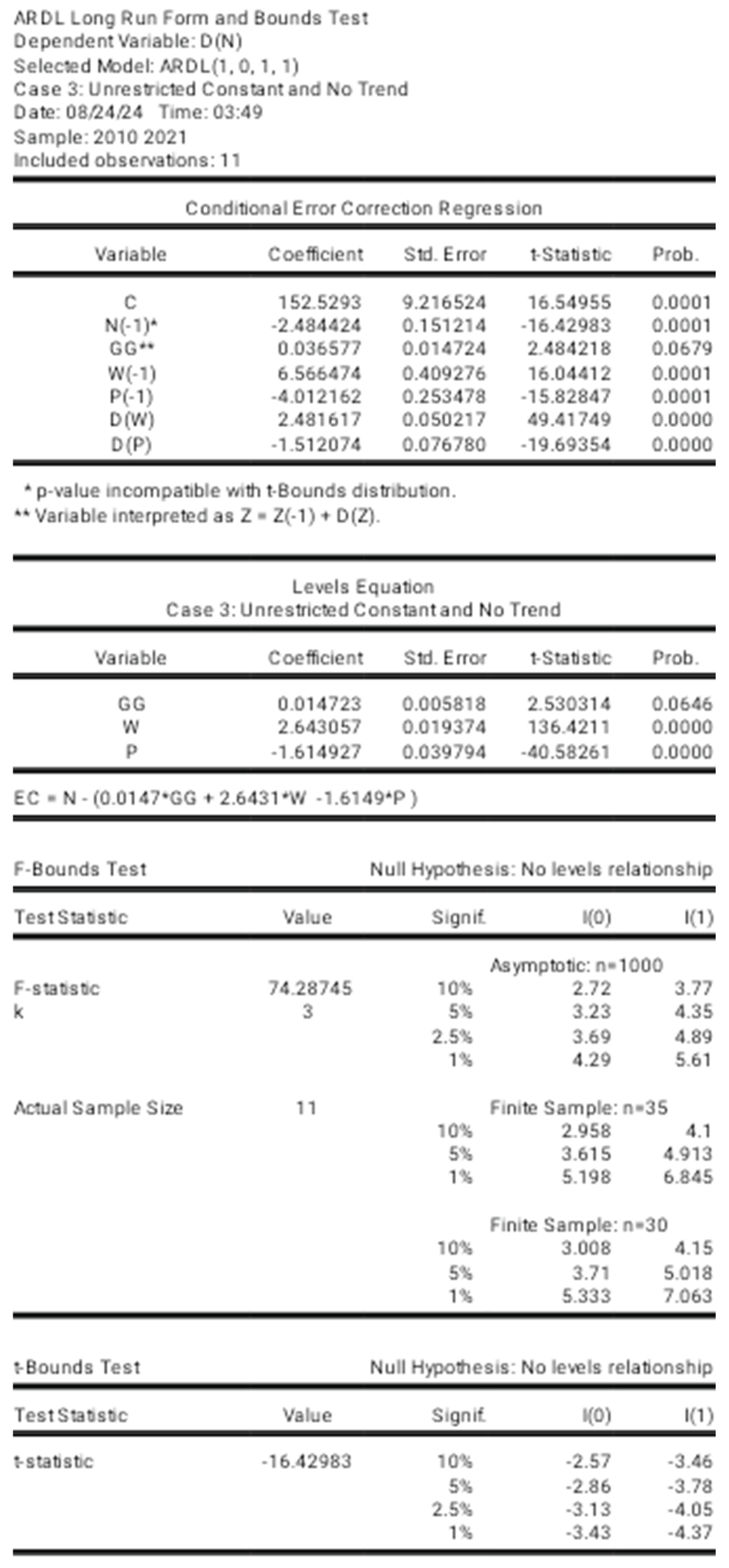

After running for different models (as shown in the

Appendix A), it was found that Model 3 with unrestricted constant and no trend is significant. Coefficient diagnosis yield the following results as seen in

Table 2.

In

Table 2 reports the results of bounds test. The calculated F-statistic (74.28) for the model is higher than the critical values at all 1% , 5% and 10% level of significance. Therefore, the results are significant, and there is existence of cointegration between the variables. Hence, full time employment of Artists and related workers (16 years and over) in America is greatly impacted by the chosen variables. Following this, the analysis for determining long-run relationship has been done.

Table 3 show the long-run estimated coefficients of the model. Full time employment of women artists and percentage of full-time employment of women artists out of total artist employment in America significantly impact per capita GDP growth. The relationship between the full time employment of women artists in America and employment of artists in America is negative. It can be stated that 1% increase in employment of women artists will lead to fall in full time employment of artists in America by approximate of 3%. However, percentage increase in full time employment of women artists in America out of total artists will lead to a positive increase in overall employment of artists in American economy. This indicates a strange behavior here. the negative and positive relationship suggests that the policies should aim at increasing women representation in relative to total employment of artists in American economy rather that just focusing on increasing the number of women artists. As mere increase in women artists in the American economy will not lead to a permanent long run increase in the overall employment of artists in American economy. This may be on the account of the fact that women engage in diverse works linked to social etiquettes following the increase in the age.

Other variable- Gender gap in annual artist gender ratio is not seen to be significantly impacting the overall employment of artists in the long the run. This explains that gender is less impactful in shaping the nature of employment of artists in the American economy. Artist employment hence may be depended on much more realistic factors linked to talent rather than gender-based stereotypes in the American economy. So, policies in American economy should not aim at bridging at gender gap issues in employment of artists in American economy, rather the focus should be on increasing percentage of women artists employed relative to full employment of artists in the America. This will automatically correct the gender gap issue and also increase the employment of artists in the economy.

The estimated results of short-run dynamic coefficients using Error Correction Method (ECM) of model are given in

Table 4. There is significant presence of intercept in results. The estimated short-run coefficient of all the variables except lagged value of W is shown to significantly impact the independent variable in the short run. Also in

Table 4, the

coefficient (-1.512) is negative although significant at 5% level. “It shows that if there is any shock in the short run then will the relation be again established or not. The necessary condition for error term must be negative and significant, so we reject the null hypothesis”(Bhardwaj & Yadav, 2023). Therefore, the equilibrium is significantly impacted by short-run shocks.

Policy Evaluation

In a summarized view point, American policies are directed towards bridging the gender gaps and reducing the gender inequalities in employment in various occupations in America. There are general laws which aim at tackling the aforementioned issues. To begin with, the first section of policies aims to reduce sex discrimination at work place. The guidelines are outlined in the “Civil Rights Act of 1964” and ‘National Partnership for Women and Families Act 2004”. Next, the US administration believes in curbing the existence of gender-based Pay Gap with the target of tackling the causes behind it. Equal Pay Act was introduced in 1963 was framed on this target. Further, “Federal Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993” provides with safe guards against all issues pertaining to pregnancy, maternity & parental leave. Also, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), introduced in 2010 was launched with an intention ‘to transform the US healthcare system from one shaped by providers to one serving the population’. Policies have also been framed at increasing equal representation of women in the top positions in business and decision-making process. ‘In 1962, Catalyst, a non-profit agency specializing in women’s jobs, was founded with a dual mission: to assist women achieve their maximum professional potential and to help employers capitalise on their female employees’ abilities’ (Davaki 2016). “The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA)” was introduced to reduce or end all forms of violence against women.

All the above-mentioned policies could be seen as directed towards ensuring women empowerment and reducing all sought of issues pertaining to mischief against them. These policies have been laid with a general perspective and are not specific to artist employment in the American economy. The safeguards related to artist employment in America are simply covered under immigration laws and address issues faced by and related to working of foreign artists in America. Very little can be achieved from these policies, as they don’t address the sector specific issues present in employment structure of artists and related workers in the economy. All these gaps have been highlighted by Americans for the Arts (AFTA). AFTA is well known NGO working for care of art and artists in America, since its establishment in 1960. It has also advocated such “policies that support artists and the arts sector, including access to healthcare, fair pay, and social safety nets”. There approach is of seeking protection is social and political. However, there is need for economic outreach which is advocated by this research. This research has provided gender specific solution to leakages in the American policy which have been elaborated further.

Most importantly, here is need for specific policies which shall tackle issues related to Gender Gap and Women Representation in Artist Employment in America. Targeting of such issues should be based on economically established facts and should aim at addressing structural gaps in employment of artists and their working in the economy. As stated from this research, it is revealed that gender gap in artist gender ratio doesn’t significantly impact the nature of employment of artists in the American economy, rather it is the percentage of women artists in relative to total artists in the American economy which has a long run positive impact on the total full-time employment of artists in the economy. Hence, it is need of the hour to realize that the general policies in America which aim to merely reduce the gender gap may not directly help in curbing the issue of underemployment of women artists in the American economy. It is advised that policies in American economy should not aim at bridging at gender gap issues in employment of artists in American economy, rather the focus should be on increasing percentage of women artists employed relative to full employment of artists in the America. This will address the issue of underrepresentation of women artists in America and will also help in bridging the gap in gender disparity.

Bridging the Gap and Economic Growth

Increasing percentage of women artists in relative to total artists in the American economy which has a long run positive impact on the total full-time employment of artists in the economy. Full-time employment, in economic terms, means the number of workers who are willing to work are employed at existing wage rate and rate of unemployment is zero. Increase in full employment also explains that economy is resilient enough to absorb present level of supply of labor. This clearly explains women indirectly are involved in developing the economy. This is the reason why women are considered as one of the main factors behind driving gender-based growth in the nations and increasing their representation will help in improving the economy of America. Several studies have validated this view and consider women empowerment, their increased participation rate in employment, their active role in society as some of the few factors accounting for growth and holistic development of the nation (Elson & Seth, 2019). Debt and financial inclusion studies have further elaborated this concept by explaining behavioral aspect. They explain that women are better in saving, doing household management and in taking business decisions then men (Adegbite & Machethe, 2020; Reboul et al., 2021; Rugy & Salmon, 2020). This research is complementary to the previously established studies which deliberate upon women led inclusive development of the country. Therefore, this research suggests that along with bridging of policy loopholes in artist employment in America, the policy makers should aim at addressing the gender issues in employment and increase the percentage of women employment relative to total employment in the country.

Appendix A

Results of Unit Root Test

Results of ARDL and Bounds Test

References

- Adegbite, Olayinka O, and Charles L Machethe. 2020. “Bridging the Financial Inclusion Gender Gap in Smallholder Agriculture in Nigeria : An Untapped Potential for Sustainable Development.” World Development 127:104755. [CrossRef]

- Adegbite, O. O., & Machethe, C. L. (2020). Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria : An untapped potential for sustainable development. World Development, 127, 104755. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H., & Yadav, K. D. (2023). The Green New Deal and the Development Conundrum in India. European Economic Letters, 13(3), 1021–1029. https://www.eelet.org.uk/index.php/journal/article/view/396/337.

- Dex, S. (1988). Issues of gender and employment. Social History, 13(2), 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Elson, D., & Seth, A. (2019). GENDER EQUALITY AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH : Economic Policies to Achieve Sustainable Development.

- Reboul, E., Guérin, I., & Nordman, C. J. (2021). The gender of debt and credit: Insights from rural Tamil Nadu. World Development, 142, 105363. [CrossRef]

- Rugy, V. De, & Salmon, J. (2020). Debt and Growth : A Decade of Studies (Issue April). George Mason University.

- Bertay, Ata Can, Ljubica Dordevic, and Can Sever. 2020. “Gender Inequality and Economic Growth: Evidence from Industry-Level Data.”.

- Çagatay, Nilüfer. 1998. “Engendering Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies.” 6. Engendering Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies. http://www.undp.org/seped.

- Casey, Britiany. 2016. “(Women) Artists and the Gender Gap (Museum): An Analysis of Inequality, Invisibility and Underrepresentation, a Case Study at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.” University of Nebraska.

- D’Acunto, Francesco, Ulrike Malmendier, and Michael Weber. 2021. “Gender Roles Produce Divergent Economic Expectations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (21). [CrossRef]

- Davaki, Konstantina. 2016. “Gender Equality Policies in the USA.” Vol. 19.

- Elson, Diane, and Anuradha Seth. 2019. GENDER EQUALITY AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH : Economic Policies to Achieve Sustainable Development. New York.

- Gap, Gender Wage, What Causes, and Gender Wage Gap. 2023. “Understanding the Gender Wage Gap.” Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor.

- Ghosh, Chandralekha, and Rimita Hom Chaudhury. 2019. “Gender Gap in Case of Financial Inclusion: An Empirical Analysis in Indian Context.” Economics Bulletin 39 (4): 2615–30.

- Hegewisch, Ariane, and Emily Ellis. 2020. “The Gender Wage Gap by Occupation 2014 and by Race and Ethnicity.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research 10 (March): 7. http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-gender-wage-gap-by-occupation-2014-and-by-race-and-ethnicity/at_download/file.

- Lindemann, Danielle J., Carly A. Rush, and Steven J. Tepper. 2016. “An Asymmetrical Portrait: Exploring Gendered Income Inequality in the Arts.” Social Currents 3 (4): 332–48. [CrossRef]

- Miller, Diana L. 2016. “Gender and the Artist Archetype: Understanding Gender Inequality in Artistic Careers.” Sociology Compass 10 (2): 119–31. [CrossRef]

- Mndolwa, Florence D., and Abdul Latif Alhassan. 2020. “Gender Disparities in Financial Inclusion: Insights from.

- Tanzania.” African Development Review 32 (4): 578–90. [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, Hema, Rahul Lahoti, and J. Y. Suchitra. 2012. “Gender Asset and Wealth Gaps: Evidence from Karnataka.” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (35): 59–67.

- UNECE. 2010. “DEVELOPING GENDER STATISTICS : A Practical Tool.” http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/publications/Developing_Gender_Statistics.pdf.

Table 1.

Results of Unit Root Test.

Table 1.

Results of Unit Root Test.

| Variables |

ADF Test |

PP Test |

| (With intercept and trend) |

(With intercept and trend) |

| Level |

First Difference |

Level |

First Difference |

| NA (Y) |

0.5931 |

-4.6656*** |

0.9323 |

-4.5222*** |

| GG |

-0.8121 |

-5.3895*** |

-0.8121 |

-5.4329*** |

| P |

0.6517 |

-8.5096*** |

0.9701 |

-12.0863*** |

| W |

1.5719 |

-6.5050*** |

1.3686 |

-6.2795*** |

Table 2.

Results of ARDL Bounds Test.

Table 2.

Results of ARDL Bounds Test.

| F-statistics |

Level of Significance |

Critical Bound

F-statistics |

|

|

I(0) LCB |

I(1) UCB |

|

| |

|

| 74.28745 |

1% |

4.29 |

5.61 |

|

| |

5% |

3.23 |

4.35 |

|

| |

10% |

2.72 |

3.77 |

|

Table 3.

Estimated Long Run Coefficients from ARDL Model.

Table 3.

Estimated Long Run Coefficients from ARDL Model.

| Dependent Variable: Y |

| Variables |

Coefficient |

SE |

T-Ratio |

P |

| GG |

-0.014723 |

0.005818 |

2.530314 |

0.0646 |

| W |

-2.643057 |

0.019374 |

136.4211* |

0.0000 |

| P |

1.614927 |

0.039794 |

-40.58261* |

0.0000 |

Table 4.

Estimated Short Run Coefficients from ARDL Model.

Table 4.

Estimated Short Run Coefficients from ARDL Model.

| Dependent Variable: Y |

| Variables |

Coefficient |

SE |

T-Ratio |

P |

| C |

152.5293 |

9.216524 |

16.549* |

0.0001 |

| GG |

-2.4844324 |

0.151214 |

-16.429* |

0.0001 |

| W(-1) |

0.036577 |

0.014724 |

2.48422 |

0.0679 |

| P(-1) |

6.566474 |

0.409276 |

16.044* |

0.0001 |

| D(W) |

-4.012162 |

0.253478 |

-15.828* |

0.0001 |

| D(P) |

2.481617 |

0.050217 |

49417* |

0.0000 |

|

-1.512074 |

0.076780 |

19.693* |

0.0000 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).