1. Introduction

As a critical component of the information menu, spatial and temporal data are critical pieces for any intelligent system. Spatial and temporal data are critical for numerous types of decisions or techniques, including but not limited to spatial modeling, event detection, and data filtration. Within the scope of foundation models, one critical dimension of spatial and temporal data that is particularly relevant is that of qualitative reasoning [

4,

27,

30], leveraging the language that we use for describing spatial and/or temporal scenes directly with data-forward technologies. Early research in geofoundation models and large language models demonstrates that topological spatial reasoning is attainable, specifically that topological relations and/or spatial prepositions can be detected by various means [

8,

10,

18,

27], and furthermore, that these models are able to recreate various spatial reasoning results, including composition tables and conceptual neighborhood graphs to varying degrees of accuracy [

4]. The ability to distinguish topological relations and/or spatial prepositions is a necessary precondition for being able to consider the transition of relations in a temporal sequence [

17,

24,

25,

26], a fundamental task necessary for spatial intelligence [

4].

Qualitative spatial reasoning hones in on aspects of spatial data which do not rely on strictly quantitative means (namely, stripping away artifacts of shape, angle/orientation, distance, etc.). Put more plainly, qualitative spatial reasoning aligns directly with notions of how we cognate about space [

22,

29] and express our thoughts about it [

10]. Qualitative spatial reasoning as a field of study has large swaths of research ranging from the formation of spatial formalisms (e.g., [

20,

39]), applications of those formalisms to embedding constraints (e.g., [

12,

34]), construction of conceptual neighborhood graphs (e.g., [

5,

24,

25]), studies of interoperability (e,g,, [

6,

8]), and examination of relation algebra concepts (e.g., [

14,

36]). Depending on the particular set of relations within embeddings, varying levels of study have been conducted. As a general rule, simple sets of continuous vector-borne relations are extremely well studied, whereas complex sets (e.g., [

12,

33,

41]) have been studied much less extensively.

Within the context of geofoundation models, it is paramount to develop systems geared toward spatial machine learning. While we can think of that concept in quantitative means (such as with spatial error regressions, spatial lag regressions, or spatial kriging), we can also think about more qualitative spatial machine learning, aiming more toward categorization tasks, a de facto form of event detection [

27]. While we can search for points or pixels in a spatial field that have a particular value or property, the environment where qualitative spatial reasoning helps is to consider the interplay between such defined objects and the various ways in which humans might search for these interplays [

35] and have an interest in how they change through time [

4]. It is in this light that we present this chapter: not as an analysis of how the technique is currently applied to geofoundation models, but rather as a call to action for the inclusion of this theory within this model as a necessary follow on to topological extraction approaches [

27,

35].

In this chapter, we will consider the qualitative reasoning technique known as the conceptual neighborhood graph [

24]. This tool provides fundamental organization to relation sets and varies based upon the deformation(s) deemed contextually important. We will explore how this technique can be used for several tasks that become critical aspects in a spatial machine learning environment. The rest of the chapter is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses the conceptual neighborhood graph approach.

Section 3 details several use cases for the conceptual neighborhood graph in spatial machine learning and geofoundation models.

Section 4 details future avenues of study to better leverage conceptual neighborhood graphs in practice.

2. Conceptual Neighborhood Graphs

Much like data mining concepts such as k-nearest neighbors in data mining and machine learning, the idea of a conceptual neighborhood graph (CNG) is inherently a model of similarity between different relations. In the k-nearest neighbors approach, the k neighbors may be considered democratically (each equal) or in some distance-based weighting fashion when contributing to a categorization of an otherwise unknown data point. The conceptual neighborhood graph relates to this approach in a sense of defining a local neighborhood structure for categories, a form of a knowledge graph.

Cohn [

3] begins the journey toward the conceptual neighborhood graph model by considering transitions between topological or mereotopological states. Freksa [

24] originates the conceptual neighborhood graph as a way to organize the temporal interval relations [

1] through this transition logic. In this infantile state, three specific types of deformations of intervals are considered:

translation, namely an interval unchanged in size is moved to another location continuously

isotropic scaling, namely an interval extends (or contracts) evenly in both directions with a fixed center point, and

anisotropic scaling, namely an interval extends (or contracts) in one direction, with the other endpoint fixed.

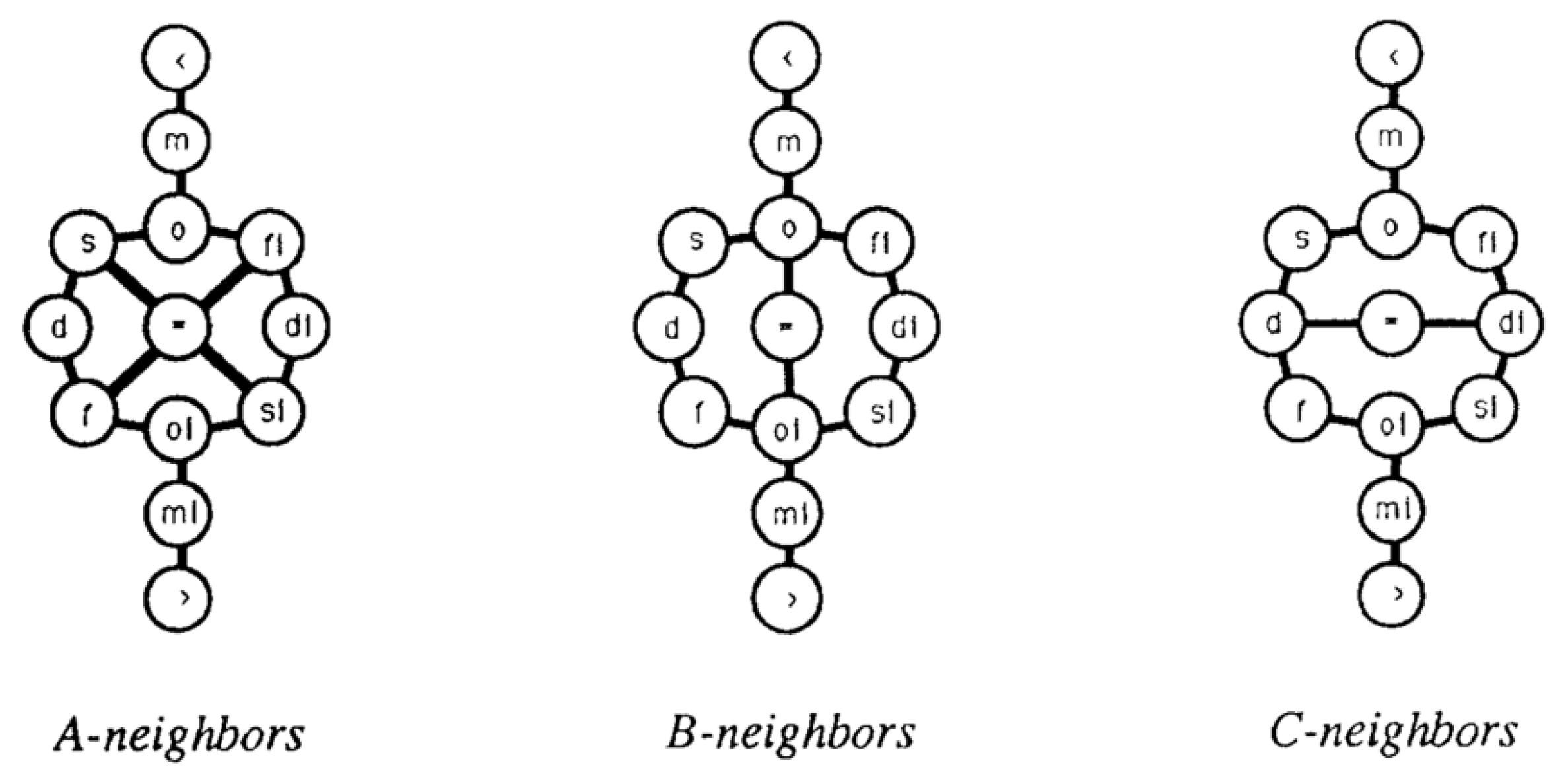

Through rigorously studying temporal intervals, the first conceptual neighborhood graphs emerged. This method employed basic ordering relations amongst the four endpoints of intervals and then using the basic ordering relations (<, = , >) to consider the various deformations described above as a sequence of changes to the ordering of the endpoints. In each case, the endpoints of one of the objects were held immutable. The difference in deriving conceptual neighborhood graphs for intervals was found in the other object. For translation, the endpoints would both be mutable, but the distance between them would be immutable; for isotropic scaling, the end points were both mutable, but the resulting changes must be equidistant, but in opposite directions, resulting in uniform growth or shrinking in both directions; for anisotropic scaling, one endpoint would be considered immutable, whilst the other was mutable. If the continuous deformation made to the object resulted in an immediate change to the topological relation, the topological relation was identified as a conceptual neighbor. Freksa [

24] determined that each of these different approaches to deforming an interval created a different organization of the relation space. Freksa’s neighborhoods are shown in

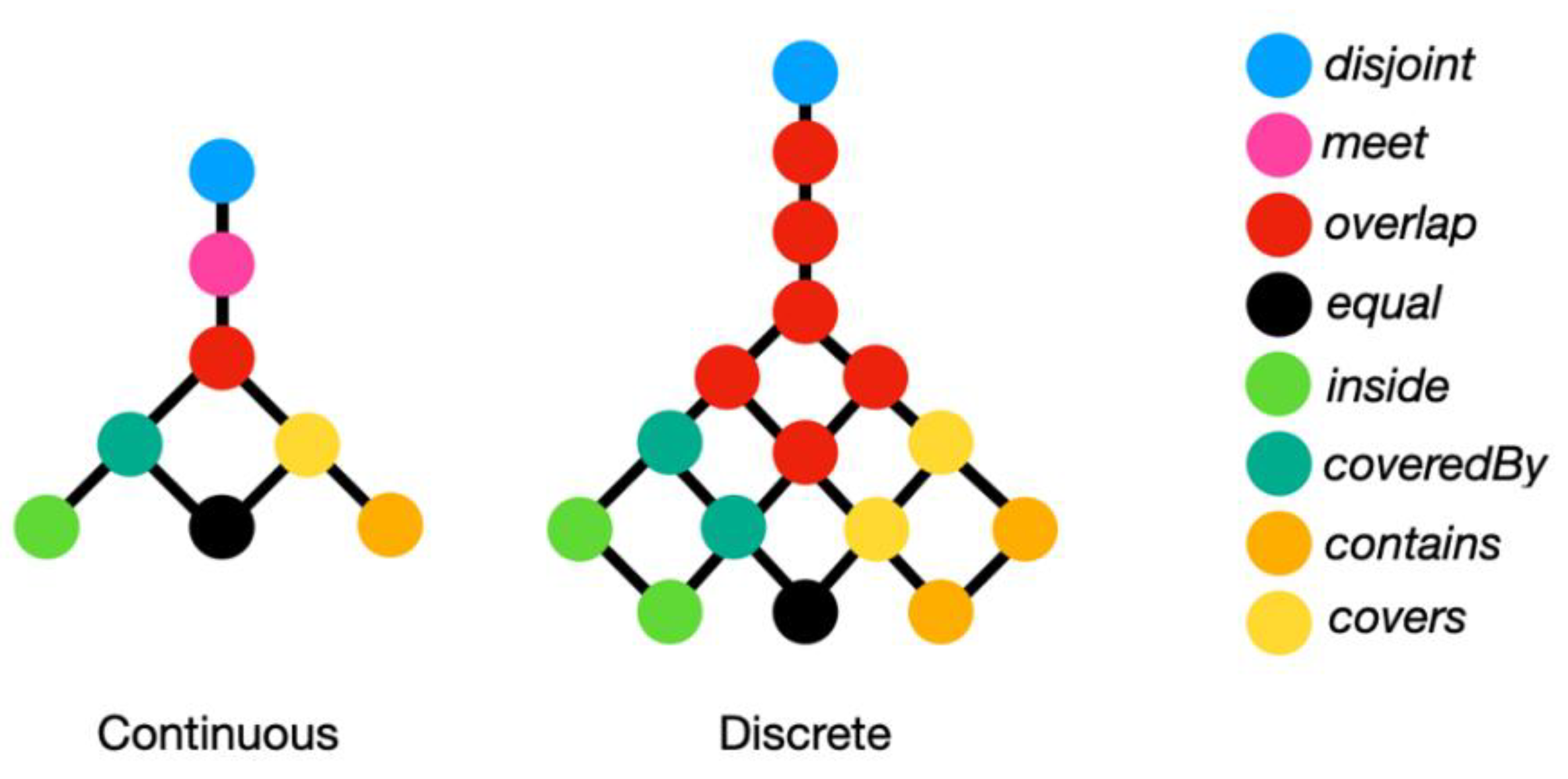

Figure 1.

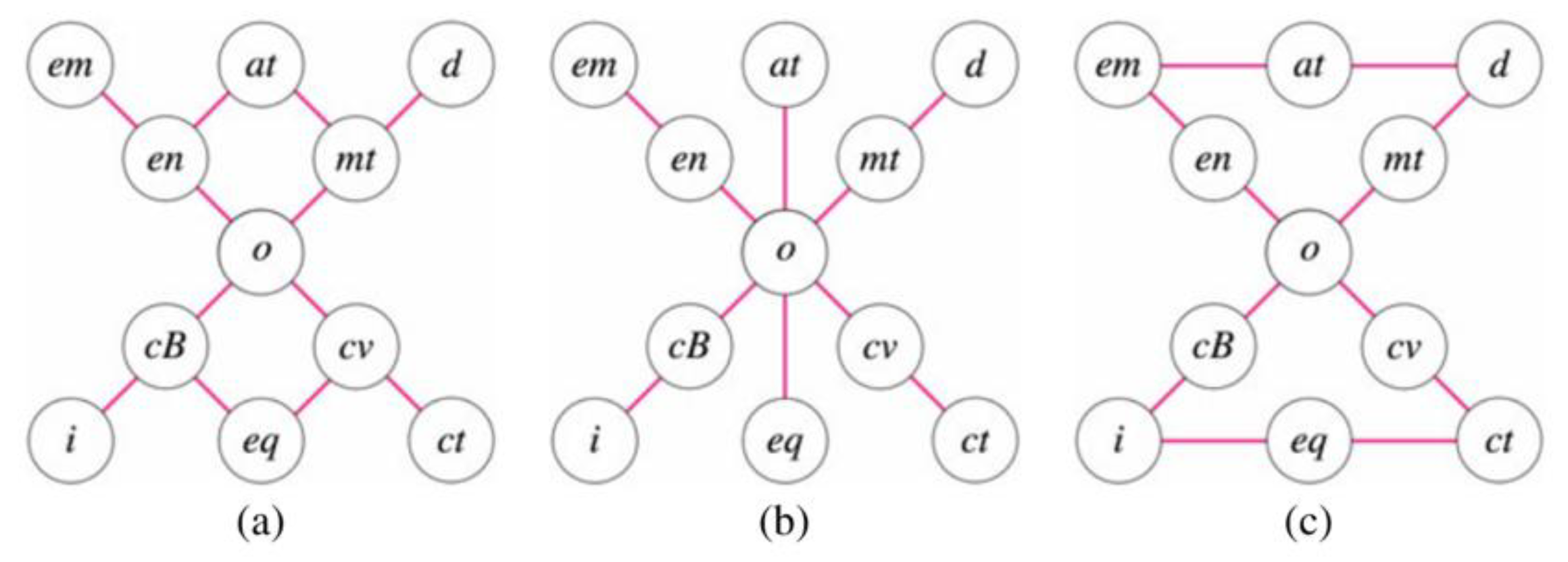

Temporal intervals, however, are not geographic objects. Many researchers have applied Freksa’s methodology to better understand the organization of corresponding spatial logics. Egenhofer and Al-Taha [

17] studied the same three deformations, and added a fourth:

rotation. They found that similar patterns from the temporal interval conceptual neighborhood graphs were exhibited in geographic space, but rotation was something completely different in that it is not afforded by a linear space to interval objects. Rotation, however, shares the same pattern as anisotropic scaling. The approach taken in this research was to compute the minimum topological distance between relations using the 9-intersection [

20]. Systematic transformations consistent with the geometric operations were applied to objects to identify how the 9-intersection matrix changed with respect to the starting and ending relation. Their approach discovered connections between relations that did not exhibit minimum topological distance, suggesting that the 9-intersection alone was not enough to describe a predictable transition between relations under all possible homeomorphic deformations [

17]. These three neighborhoods are shown in

Figure 2.

Egenhofer and several colleagues went on to apply conceptual neighborhood graphs to all kinds of relation sets, including a primitive neighborhood for discretized topological relations [

23], line-region relations [

21], line-line relations [

40], spherical relations [

15], and discrete spherical relations [

9]. Hall and colleagues [

25,

26] went on to fully define multiple conceptual neighborhood graphs for the discretized topological relations. While Egenhofer and Al-Taha [

17] were limited by the vectorized nature of the objects under consideration, these researchers were able to leverage methods similar to Freksa to achieve conceptual neighborhood graphs by formalizing the transitions through changes to the pixels in the objects [

25,

26]. That work specifically added a different concept to the conceptual neighborhood graph environment: a conceptual neighborhood graph that is contextualized to size. This is particularly important in discretized embeddings where the amount of pixels (finite) determines types of relations that are realizable, whereas in continuous embeddings, the density of the space makes this less of an issue as the amount of points are infinite. There are thus no shortage of conceptual neighborhood graphs with which to work with in the established qualitative spatial reasoning literature.

On top of the base conceptual neighborhood graphs, three other key developments have been identified within this body of literature. Egenhofer [

16] proposed a value in using the intersection or union of neighborhoods to create additional neighborhood structures, representing conjunctive or disjunctive pursuits. Dube [

5] proposed a conceptual neighborhood graph structure based on non-homeomorphic deformations (examples shown in

Figure 3), opening the door to objects that change their physical structure [

28], and in the process provided an opportunity to considering a future of linking conceptual neighborhood graphs into a more global ontology, supporting cartographic generalization [

37,

42]. Dube [

7] also proposed a shortcut for establishing primitive conceptual neighborhood graphs by searching for the smallest 9-intersection matrix (or conceivably other cousins of the representation) difference between scenes, independent of the embedding space or object types that are considered. That same approach could be leveraged for spatial scene languages [

31,

32] or compound object models [

13].

While useful as a conceptual model, conceptual neighborhood graphs have not, however, seen much practical usage in computing technologies to date. The current state of the art in spatial information systems is to find Boolean matches between a qualitative query and the records of the geospatial database table [

2]. Conceptual neighborhood graphs do not fit in that limited model scope, however, they create an excellent opportunity to expand capacity toward decision support systems, but more importantly can pave the way for critical advancement in geospatial artificial intelligence [

25]. In the next section, we will consider several applications that would be critical for spatial machine learning, each of which with functional connection to the tools and insights provided by conceptual neighborhood graphs as organizations of relation spaces.

3. Use Cases for Conceptual Neighborhood Graphs

In this section, we will consider several directions leveraging conceptual neighborhood graphs that provide potential promise in an environment of geofoundation models and spatial machine learning. We will consider the following cases:

similar (but not necessarily identical) CNG configurations

temporal event detection within a spatial context

spatial completeness tracking

integrating information from several different relation sets

non-primitive spatial prepositions

3.1. Similar Configurations, but not Exact Matches

Consider a person working in a municipal setting who is doing a study utilizing cadastral records that need to be compared to features that might impact future cadastral decisions. Two critical examples of this type of work might include searching for trees that are encroaching property lines or driveways or buildings that are too close to the property line, potentially requiring a zoning variance or corrective deed.

The exemplar case of this problem is pretty straightforward. For the tree-encroachment scenario, the obvious important data in the spatial scene represents a tree whose canopy is somehow intersected by the cadastral boundary of a parcel. Intuitively, this relation is

overlap and there are several ways of detecting this [

8,

10,

18,

27]. If we find this configuration, we know that we have a red flag in the practical application space and we need to address it. There are, however, other cases that do not follow this prototype but are just as potentially problematic. It is in this particular issue that we find one significant utility of the conceptual neighborhood graph: it implicitly has the capacity to rank potential solutions to a query as opposed to returning a singular Boolean answer on every record. Because the conceptual neighborhood graph represents a partial ordering of a set of relations based on a set of allowable transformations to the objects, if a relation can be transformed through a minimal such deformation and result in a different relation, then they are connected in the graph. This particular effect is precisely how somehow closely similar observations can be ranked according to deformational similarity. This is particularly important in discretized settings, where the resolution within an image can create scenarios where the relation between two real-world objects transforms based on the resolution of the image, something that does not occur in a vectorized embedding. While Cohn and Blackwell [

4] examined the ability of geofoundation models to reconstruct a conceptual neighborhood graph, this scenario represents a different case: it represents a pre-established method provided to an artificially intelligent agent to help facilitate the achievement of semantically similar terms, anticipating that data quality may be an issue.

Now envision a person interacting with an intelligent agent in that cadastral scenario. As they think through their problem, they might ask the intelligent agent a question such as “

find all trees in the canopy layer that have a meet or overlap relation with a property in the cadastral layer”. This question shows some forethought by the person: they know that there are multiple forms of potential challenges. In the discretized setting, they have however unwittingly provided two separate relations that are not connected in any CNG [

25,

26]. The intelligent agent should then prompt the user to clarify: “

should any relation between these two targets also be included?”. This prompt is specifically motivated by the structure of the CNG itself. It should also prompt on the fringe cases next to

meet and

overlap:

disjointTouch,

overlapCovers, and

overlapCoveredBy because these are the relations that bound the query region. In this case, it is likely that the person would care about

disjointTouch as a future problem, but likely neglect the other two because it is inconceivable for a tree to that significantly intersect a land parcel: land parcels are massive in comparison to any single tree, and these relations involve exhausting the interior.

Figure 4 represents the query with respect to the conceptual neighborhood graph for anisotropic scaling, demonstrating that a) the asked relations are separate, b) there are relations in between that should be considered, and c) there are relations that bound this area of the conceptual neighborhood graph that may also hold relevance to the user.

While modern GISs try to solve these problems through spatial dialects of SQL, these dialects of SQL do not respond to rasterized data types as CNGs representing discrete neighborhoods. These neighborhoods have only recently been rigorously studied [

25,

26] and almost unilaterally the current spatial SQL models follow Clementini operator shortcuts [

2]. This is a particular problem when we consider this exact use case: tree cover is almost always surveyed in a rasterized form through aerial photogrammetry, be it satellites, planes, helicopters, or drones. Furthermore, the shortcuts in the Clementini operators do not show the inherent possibilities that a vectorized version of a CNG contains and do not additionally provide user customization or clarification. The Clementini operators are designed to narrowly restrict the 9-intersection into relevant groupings in a pre-canned set of vocabulary. The case in

Figure 4 shows a case that would not be considered as a Clementini operator combination, but otherwise is a valid combination of relations for a user to want to meaningfully extract.

Because the datasets from these sources are rasterized, and rasterized CNGs contain a more diverse set of relations than their continuous counterparts, there is a greater diversity of vocabulary available within the corresponding CNGs, and as such, several similar relations may be mirrored across several icons to simplify. This relates to human cognition and the staple of 7 +/- 2 mental concepts in a reasoning system. It is thus imperative to leverage CNGs in this context as it answers to both issues of resolution in the rasterized scenario and human cognitive processes, key sources for an otherwise conceived of

overlap relation being characterized as something similar by either the data or the user, but alas different nevertheless [

25,

26]. Conversely, if a relation is measured by an AI to be a relation such as

overlapFully, the CNG can help direct the AI to choose spatial language of a more simplified variety (such as

overlap) through key groupings.

3.2. Integrating Temporal Event Detection Within a Spatial Context

Conceptual neighborhood graphs enhance event detection over changes in spatial and temporal relationships by considering different data sets, such as verbal descriptions and geospatial data as events or states within CNGs. Verbal descriptions can easily be mapped to CNGs [

10,

21] through their spatial prepositions (e.g.,

inside) and other language conventions that serve a similar purpose (e.g.,

touches). Monitoring in changes of successive images (such as from a video) can also be mapped onto spatial relations (e.g., [

43]) and thus also onto CNGs.

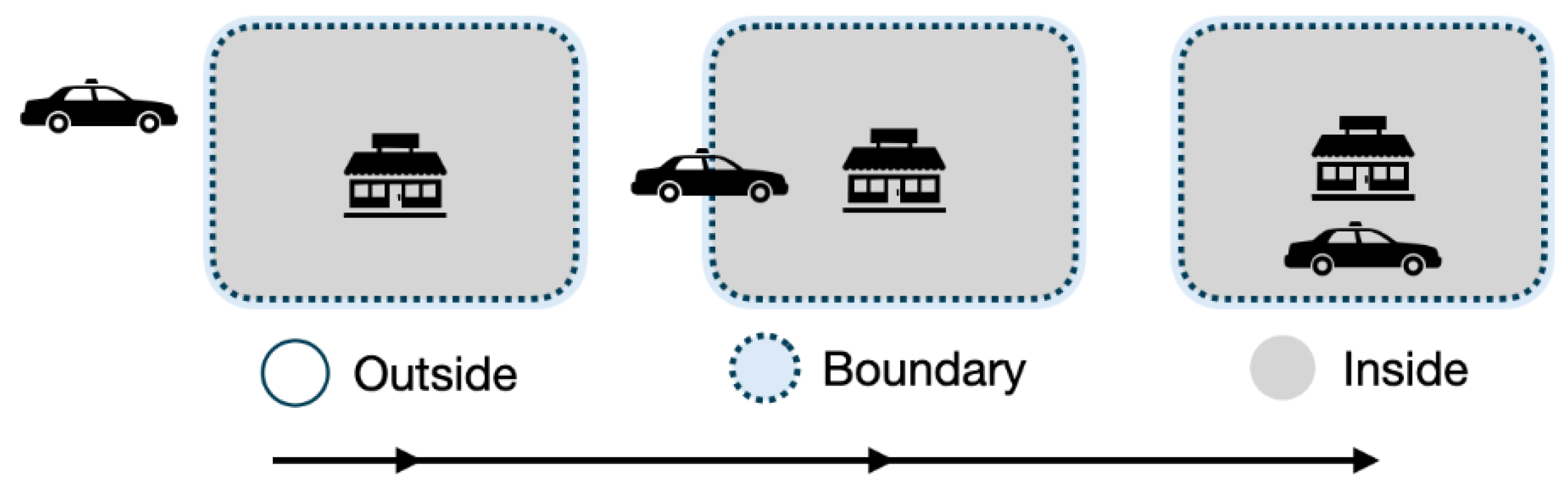

While we often think of image recognition tasks as being static exercises (e.g., what is that a picture of), spatial data mining can also involve a temporal event (e.g., a relation between objects has changed between successive images). Such an event is very common in many types of applications, and in others, has the potential to be extremely meaningful.

A simple example of a meaningful CNG event has to do with proximity to a target. Modern GISs include operations to consider buffered searches, extending the footprint of an object in some specified way. Such a buffering action allows us to classify levels of

disjoint (at the most basic level,

disjoint and

disjointTouch [

8,

23]). Consider the scenario where a user wants to identify when they get close to a grocery store. Initially, the user is not near the grocery store, a state described as

disjoint from the grocery store and its buffer. A verbal inquiry from the user may be “

let me know when I become close to a grocery store”. The grocery store corresponds to a point or set of geocoded data which are (in theory based on the context) currently

disjoint from the user position when this question is posed.

The intelligent agent monitors the device's location using geospatial data, tracking changes in the location of the device to the grocery store and its corresponding “closeness” buffer. As the device moves closer, the spatial relationship transitions along the CNG, traversing from

disjoint to

meet and progressing beyond that. Conceptual neighborhood graphs model this transition based on changes in adjacent states of the CNG. When the geospatial proximity data indicates that the user is now adjacent to a grocery store, an event can be triggered, which can notify the user or update the system state. Meaningful events would be those that follow pathways within the CNG because if the object persists, these are the next steps that must be followed. In this type of event, a car would often be monitored via a pin, symbolizing point data, and thus placing us in the conceptual neighborhood graph for point-region relations, demonstrated in

Figure 5.

3.3. Spatial Completeness Tracking

Spatial completeness tracking is a crucial aspect of spatial data analysis, where the goal is to ensure that all logical transitions between spatial states are accounted for. In this application, CNGs provide a powerful tool for identifying and inferring missing states in spatial data. For example, if an object is recorded as transitioning from a

disjoint state to an

inside state with respect to another object (such as in the prior example in

Figure 5), a CNG can infer that the object must have passed through intermediary states, such as

meet and

overlap. Other relations also exist, but at that point, the network forks. It is plausible, however, to assume that the most logical pathway is the shortest one, thus also giving us

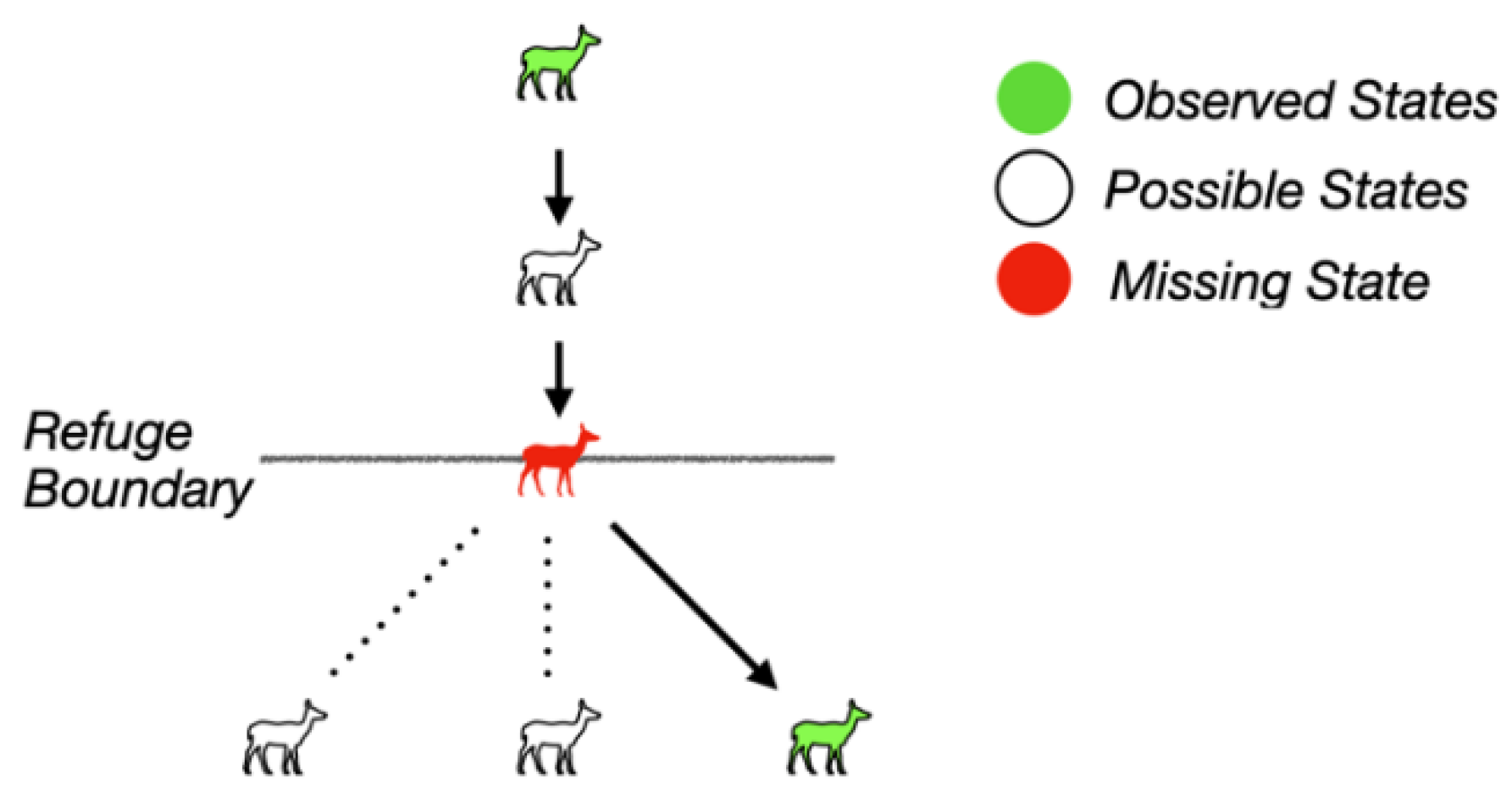

coveredBy. This ability to logically deduce missing states based on spatial relationships makes CNGs essential tools for ensuring the completeness and consistency of spatial data, particularly in the case where a user queries a system and asks for all instances of a particular occurrence of a prepositional relation.

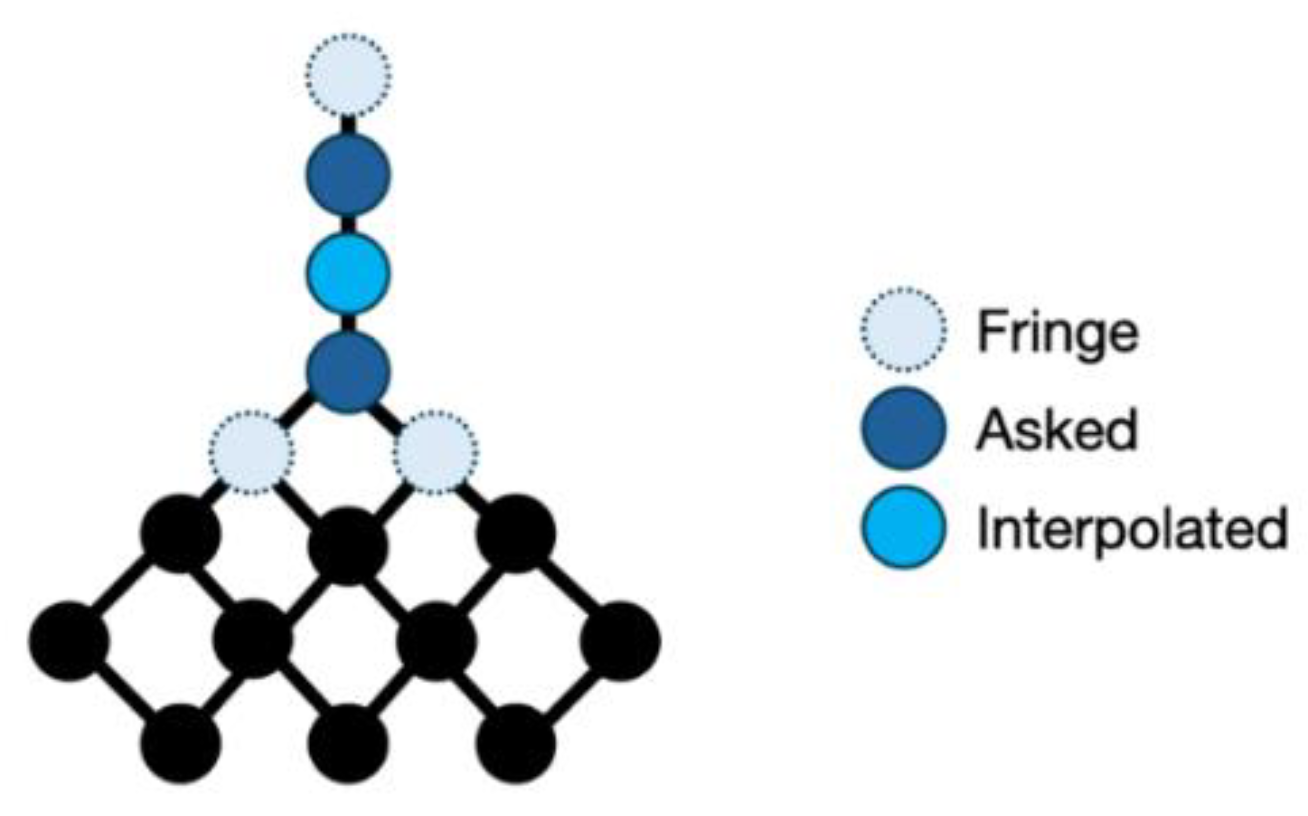

While rasterization often leads us to talk about the spatial resolution of a dataset, in dynamic datasets, we must also worry about temporal resolution as well. If the temporal resolution is extremely fine (such as with continuously sampled real time data), it is likely that we would theoretically have every possible state transition between object relations as well as transitions in object structure. However, if the temporal resolution is relatively coarse, it would be quite easy for two successive snapshots of a phenomenon to miss a state transition along a CNG, and when a question is posed to the system, the preposition can thus easily be missing when in fact it was once present in reality. This would be most common for relations like meet, coveredBy, and covers where the only distinction between them and their disjoint, inside, and contains counterparts is the coincidence of their boundaries, only likely happening for a limited amount of time as an object moves or expands/contracts. As such, a geofoundation model that is acting upon a temporal dataset should also be checking for relations that can infer that a state had occurred logically, even if they do not have the actual datapoint to confirm its occurrence.

Consider a conservationist utilizing an intelligent agent to facilitate tracking the movement of a tagged animal in relation to a wildlife sanctuary. The data shows the animal moving from one region outside the refuge (

disjoint) to next being inside a protected area (

inside), a conceptual analog akin to the car and grocery store in

Figure 5. However, there is no record of the animal being near the boundary of the protected area (

meet) or perhaps jumping the fence (

overlap) due to the temporal resolution of the data, both of which potentially of specific interest to conservationists. By considering the two states that sensors flagged within the CNGs from established data, the intelligent agent can infer the missing state(s), which might (amongst other reasons) indicate a lack of sensor coverage in the area or insufficient temporal resolution. This instance provides valuable information, prompting the scientist to verify the existing sensor network integrity, while in the meantime also being intelligent enough to recognize that this intermediary step must have occurred due to its knowledge of the CNG. This practical application highlights how CNGs not only help in identifying logical transitions but also in improving data collection and query methods by ensuring that all states are accounted for when necessary. Since the states can be inferred, they do not need to explicitly be stored.

By employing CNGs for spatial completeness tracking, intelligent agents can uncover missing or inconsistent links in data that might otherwise go unnoticed. In the process of tracking state transitions, knowledge of complete CNGs can reveal missing or overlooked states that are crucial for ensuring the integrity of analysis. For instance, in the wildlife tracking scenario, the absence of an expected intermediary state might not be immediately apparent without the established framework afforded by a CNG. By applying the consistency afforded by established CNGs to potentially incomplete state-change sensor data, intelligent agents may identify and address data inconsistencies and ensure that the analysis is as complete as possible and thus of higher extrinsic quality (

Figure 6).

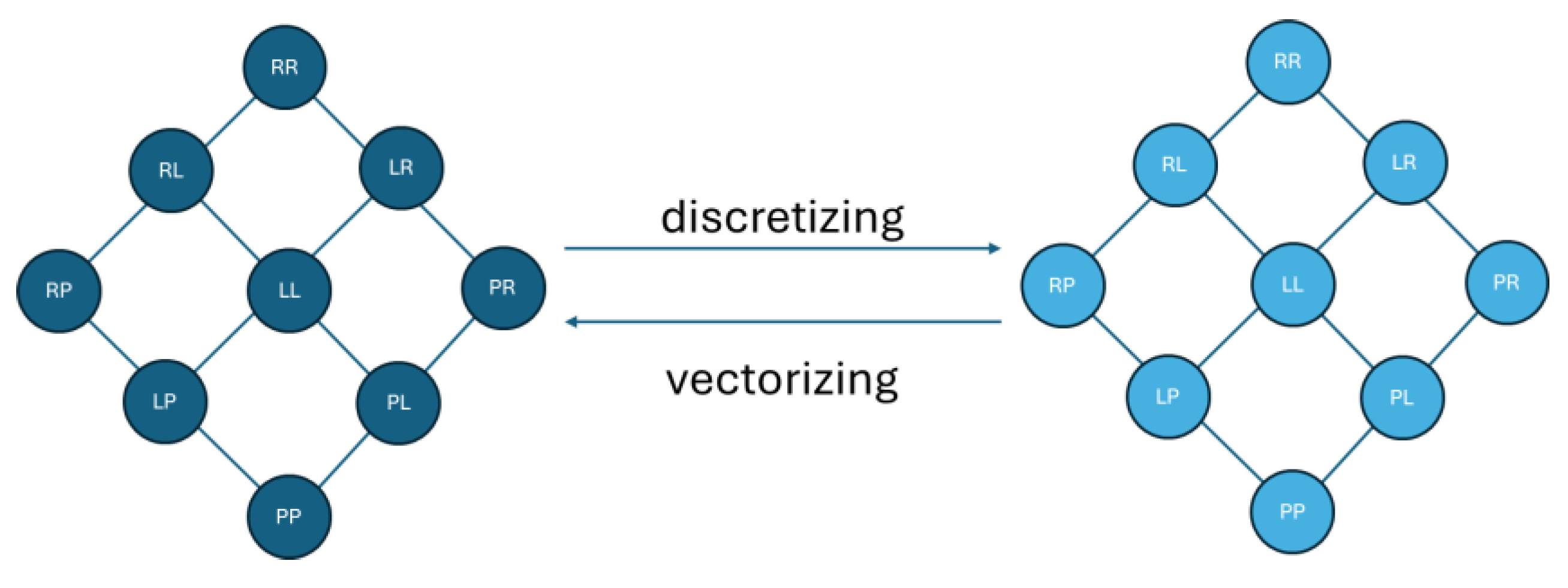

3.4. Integrating Deformation Options or Other Data Types

Being able to integrate a more diverse set of data into spatial SQL queries offers significant advantages, including in the realm of spatial machine learning. When AI systems can leverage existing SQL queries on a more diverse set of data, they benefit in several key ways. We typically envision this scenario with multiple sources of data representing several different measurements. Data integration allows AI systems to perform more holistic analyses by combining various types of data, such as vector, raster, temporal, and sensor data. This comprehensive data integration enables better understanding and modeling of complex spatial phenomena and event sequences, and thus more intelligent contextualized responses. Improved predictive accuracy is achieved through access to a broader range of data sources, allowing AI to uncover deeper insights and relationships. For example, combining demographic data with environmental factors can improve predictive models for public health, urban planning, and disaster management, but to do so potentially requires understanding the impacts of such concepts as rasterization [

23], vectorization [

44], and cartographic generalization [

37].

Consider a city aiming to improve its air quality management protocols. By integrating diverse data sets into spatial SQL queries, the city can combine vector data (e.g., locations of factories, roadways), raster data (e.g., satellite images showing vegetation cover), temporal data (e.g., historical air quality measurements), and sensor data (e.g., real-time pollution readings from air quality monitors). This integrative approach enables the intelligent agent to model the spatial and temporal dynamics of air pollution with more precision. This however comes with a cost: the different types of formats cause challenges, most notably for the purposes of this chapter cartographic generalization within map images.

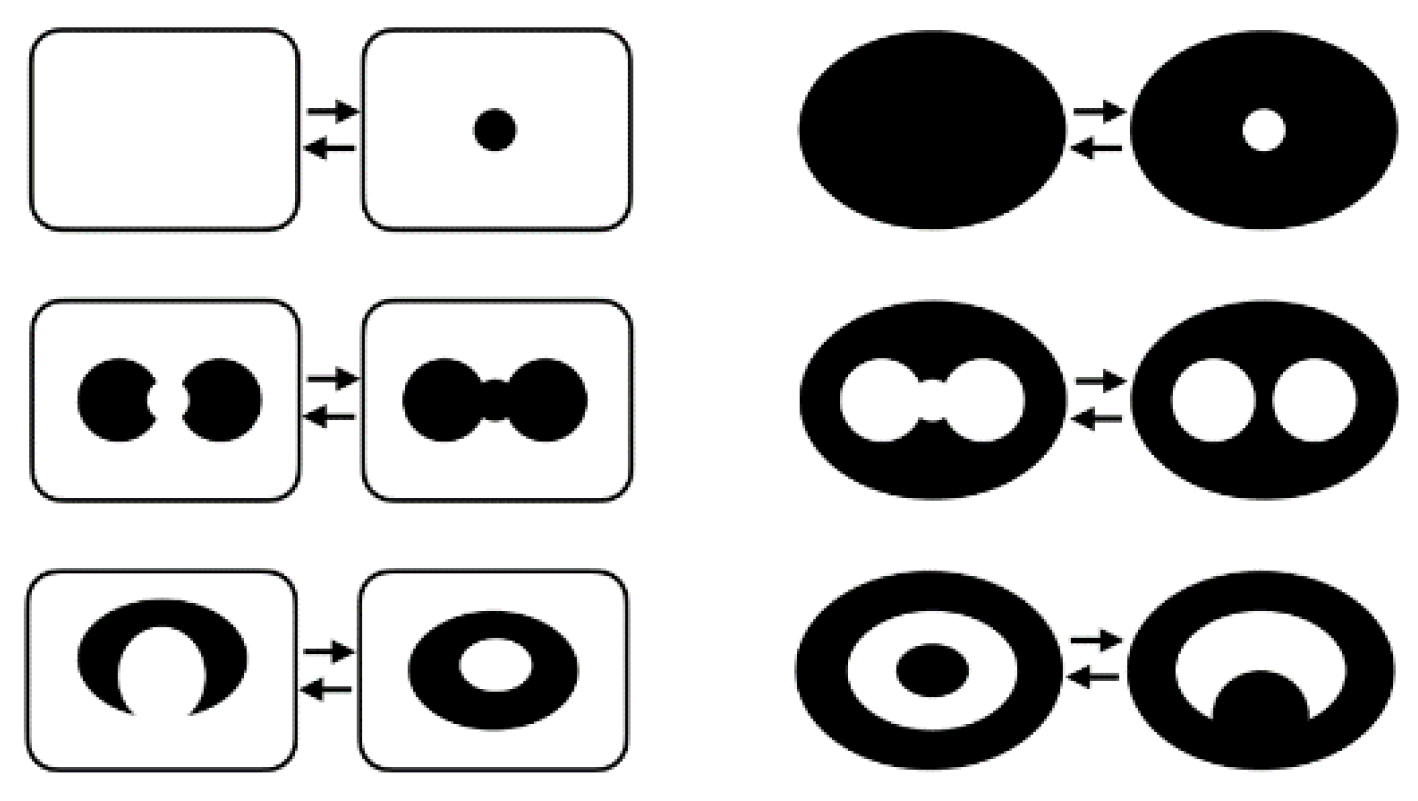

Cartographic generalization represents making fundamental changes to the reality of an object in the real world to represent it in a cartographic medium [

37]. In a digital medium, we have to think about how to optimize that process [

42]. We can think of many possible versions of cartographic generalization that can cause particular challenges in the current environment of CNGs. Current conceptual neighborhood graphs almost always focus solely on homeomorphic deformations [

16,

24,

25]. Not all deformations of an object can (or should) be homeomorphic [

5,

28]. Objects are often changed in their dimensions under cartographic generalization [

37], necessarily meaning that the family of relations itself shifts with the change (e.g., region-region to region-line). A simple example of that is the depiction of a road or a river as a line, when they clearly have an area. Currently, no conceptual neighborhood graphs work under this paradigm of linking relations from different sets, but sets of relations exist to work from toward this task [

41]. A general framework for this is shown in

Figure 7. Objects being cartographically generalized may see changes to their own internal topology (e.g., holes or separations increase or decrease) [

28]. Dube [

5] has demonstrated that conceptual neighborhoods can be considered that move beyond homeomorphic deformations, but retain that they are still regional objects. We need CNGs that connect across one another and over different object types. For instance, the region-region CNGs need to connect to their region-line, line-region, and line-line counterparts. Similarly, discretized neighborhoods need to connect to their continuous counterparts, such as might be realized through

Figure 8 [

25]. Much of this work needs to be further fleshed out in the coming years to fully realize the insights to be taken from images of historical maps and the nature of the generalizations taken in their construction. We discuss the next steps to this process in the concluding remarks.

3.5. Non-Primitive Spatial Prepositions

Spatial relations for the most part are developed in a jointly exhaustive, pairwise disjoint (JEPD) framework. While this structure is important for mathematical properties and formality, this specific property creates a potential divergence from human language and cognition [

10]. Because the theoretical purpose of intelligent agents is to provide humans with actionable insight, it is important to be able to recognize human language in all of its nuance when we try to create spatial intelligence for use by intelligent agents.

Consider a term such as

along. Along is a very common term to reference how objects relate to one another. We can envision several possible scenarios that might use that exact language, and those examples have varied topological signatures (

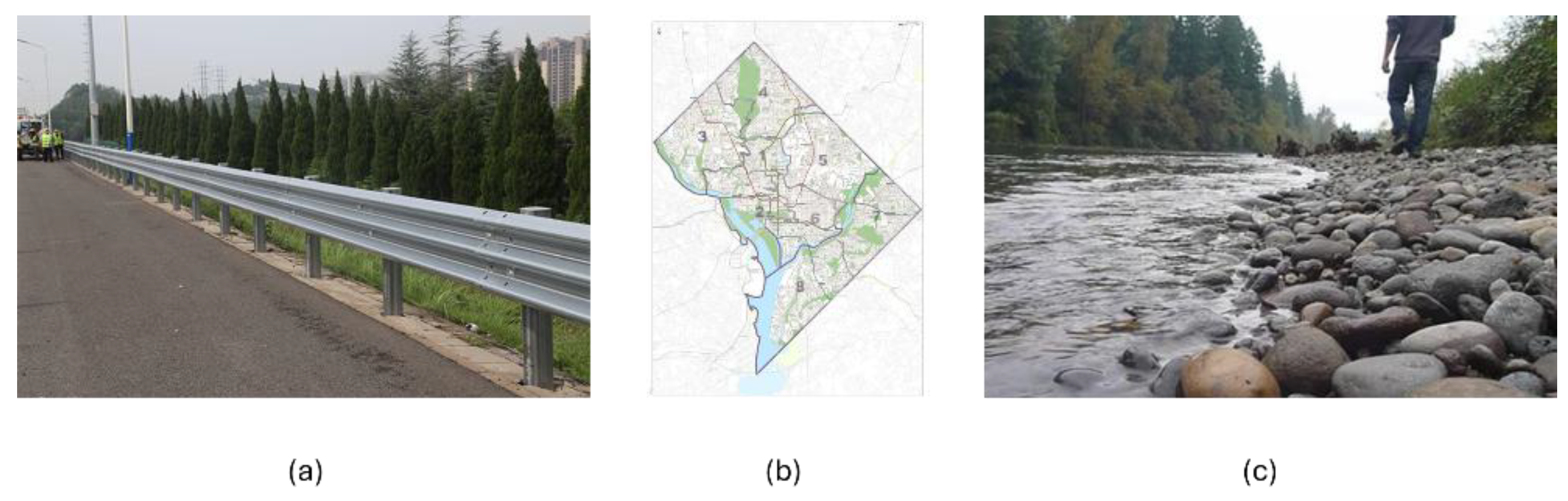

Figure 9):

The guardrail is along the road (e.g., inside the footprint of the asphalt or coveredBy the footprint of the asphalt)

The town is along the river (e.g., the footprint of the town overlaps the footprint of the river,

The person walks along the river (e.g., the location of the person follows the river, but is never in it, representing disjoint or meet)

The CNG provides a part of the answer to this problem, but it does not provide the whole answer. Dube and Egenhofer [

10] demonstrated that spatial prepositions specifically represent convex subgraphs of conceptual neighborhood graphs, effectively meaning that if there are multiple shortest paths between two atomic concepts, a spatial preposition that encompasses both of the atomic concepts will include all versions of the shortest path. This fundamentally bounds the search for these non-atomic prepositions, however, it is not the only concern for specifying them.

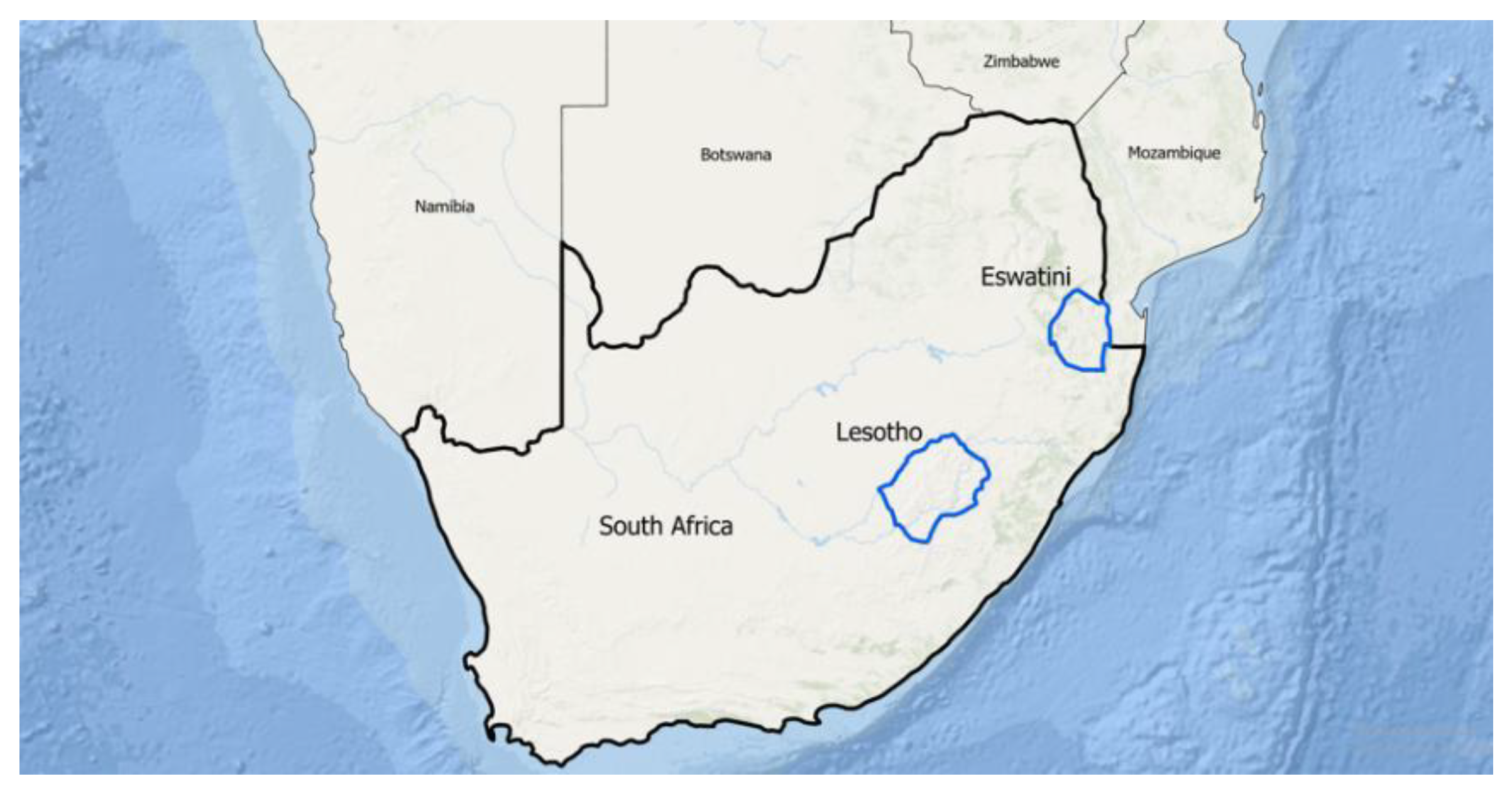

It should be clear that not all versions of

inside would necessarily be considered

along. Consider the nations of Lesotho and South Africa. Lesotho is not near the boundary of South Africa at all. It would be highly unlikely that someone would use that term to describe the relationship between Lesotho and South Africa. They would be much more likely to use the simple atomic topological relation

inside [

19] or a more complex atomic topological relation

surroundedByAttach [

11]. However, Eswatini and South Africa might use the term

along. If we think of South Africa as relatively a convex hull beneath Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique, Eswatini fits within this envelope in a

coveredBy configuration. It is also, however, small. We would not characterize South Africa’s relationship to Eswatini that way. These objects truly

meet, but their size dictates the one-way version that this

along term would have. What becomes clear is that there is metric information that must be incorporated to help make these distinctions. Some discrete relations help with this task [

8,

9,

12], but that in and of itself is not a catch all. The relationship between these three nations is shown in

Figure 10.

4. Discussion

In this chapter, we have demonstrated that conceptual neighborhood graphs provide critical insights for the development of geofoundation models. We have shown that these tools can be used to clarify and complete spatial inquiry by users, to assist in the connection of disparate forms of data, to detect and define spatio-temporal events, to fill in the gaps of missing data, and to help provide the framework for prepositions that are not always purely topological.

To fully realize these gains, there are several advancements that need to occur within conceptual neighborhood graphs. These include (but are not limited to):

The development of a definition of digital lines, and the definition of a set of topological relations between them, thus opening the door for the corresponding conceptual neighborhood graph,

The development of cross-set conceptual neighborhood graphs (such as a neighborhood graph that incorporates both region-region relations and region-line relations or a conceptual neighborhood graph that incorporates both continuous and discretized relations), and

A classification of relations that are not purely topological, but do have clear topological beginnings, likely conducted by human subjects testing based on defining metric characteristics of primitive topological relations (e.g, [

8]).

Conceptual neighborhood graphs are a critical tool along the path of a geofoundation model because they represent a direct and unifying linkage between text data and image data, but more importantly a link to human language and cognition [

10,

22,

29]. This link to human language is absolutely essential to be able to fully leverage spatial data in human-centric, cognitively plausible terms. It is important to continue studying qualitative reasoning techniques for this particular reason because at the end of the day, they serve the key role posited by Egenhofer and Mark [

22] through Naïve Geography:

topology matters, metric refines. The centerpiece of spatial cognition must be present in effective geospatial artificial intelligence. Conceptual neighborhood graphs provide integral support toward this task on many crucial levels for the success of these futuristic systems.

Conceptual neighborhood graphs are a truly interesting portion of the qualitative spatial reasoning literature, and this chapter in many ways highlights the notion of missed opportunities. These types of structures have an over three-decade longevity within the literature, however, no current spatial information system incorporates them. This is not a surprise, however. Spatial information systems do not have the expressed goal of combating uncertainties; they are built off of database architectures and database query languages. A spatial decision support system would inherently have such a goal. Additionally, spatial information systems do not natively address temporal concerns. A GIS is fundamentally more interested in the map than it is in the change in the map over time. Conceptual neighborhood graphs open the door to temporal dimensions to the GIS in very cognitively meaningful ways. It is our hope that as geofoundation models are just beginning that this history of missed opportunities is not translated into the next iteration of the development of spatio-temporal information science. By ensuring the intricate connection between human cognition and spatio-temporal data is manifest, spatially intelligent systems will be best equipped to assist humans in a collective intelligence scenario.