The starting point of this article is to provide an effective description of the chord relations involving triads and seventh chords within both tonal and non-tonal contexts. To achieve this goal, it is essential to identify the key factors influencing the relation between two chords. Therefore, this inquiry can be reframed as an evaluation of the similarity or dissimilarity between two chords. When a single chord stands alone, it appears static due to the absence of reference; it does not generate any harmonic movement and cannot reveal its own characteristics. However, when another chord is introduced, these two chords establish a reciprocal reference relation. From the perspective of psychology, Bregman (1990) emphasized that the auditory system does not passively receive sounds but actively organizes and interprets them. Tversky (1977) suggests that Similarity is based on the common and distinctive features of the objects being compared. The similarity of objects is increasing in their common features and decreasing in their distinctive features.

Stephen McAdams and Albert S. Bregman (1979) employed psychoacoustic experimental methods to derive principles of auditory grouping, highlighting that sounds that are similar in frequency, timbre, or temporal characteristics are more likely to be perceived as a whole, while sounds that are close in time or frequency tend to be grouped together. “If a musical melody is considered a kind of auditory stream (Dowling 1967), we might expect sequences of pitches to conform to the pitch proximity principle (Huron 2001:25).” Huron plotted data showing the distribution of interval sizes using samples of music from several cultures, and the results affirm the preponderance of small intervals. Even in atonal and serial music, composers often aim for smooth harmonic transitions through minimal interval motion (Tymoczko 2008). Therefore, the key variable influencing the degree of similarity between the two chords is the semitone, as it is the smallest interval and can establish the maximum degree of similarity under minimal variable conditions. Consequently, the description of the relation between the two chords can focus on their semitonal relation.

Examination of the Similarity

When two notes are in a semitonal relation, they are the closest in distance, exhibit the greatest degree of similarity to each other. This observation aligns with the Gestalt Principle of Proximity (Goldstein 2019), which suggests that objects that are proximity are perceived as related. Building on this premise, if two intervals share a common tone while the relation between the remaining notes is semitonal, then these two intervals are also at the closest distance and exhibit the greatest degree of similarity. For example, the relation between C-G and C-G♯ is closer than that between C-G and C-A, because the semitonal movement between C-G and C-G♯ is more fluid and dynamic. Furthermore, if two triads share two common tones while the relation between the remaining notes is semitonal, then these two triads are also at the closest distance and exhibit the greatest degree of similarity. For example, the relation between C-E-G and C-E-G♯ is closer than that between C-E-G and C-E-A.

Confirmation of the Examination Parameters

Through the examination of chord similarity, we can observe that the existence of semitonal movement and quantity of semitones between chords are positively correlated with the degree of tendency of their relation. When semitonal movements are present, they facilitate smooth transitions between chords, the greater the quantity of semitones, the higher degree of tendency of the connection. In a harmonic progression, by examining the presence of semitonal movements and the variations in their quantity, we can gain insights into changes in the degree of tendency of chords, as well as the relative shifts in harmonic dynamics and intensity.

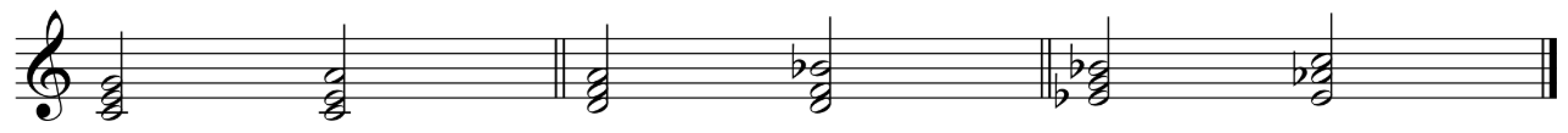

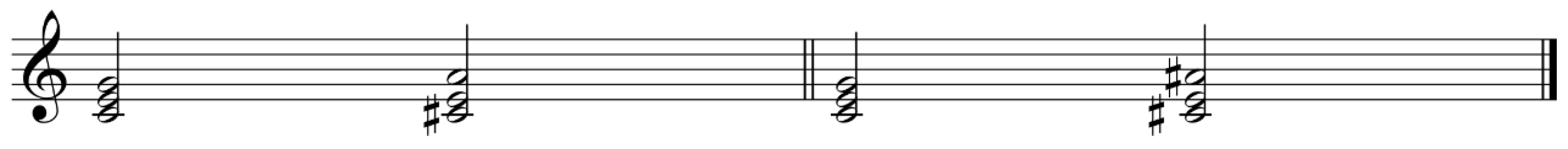

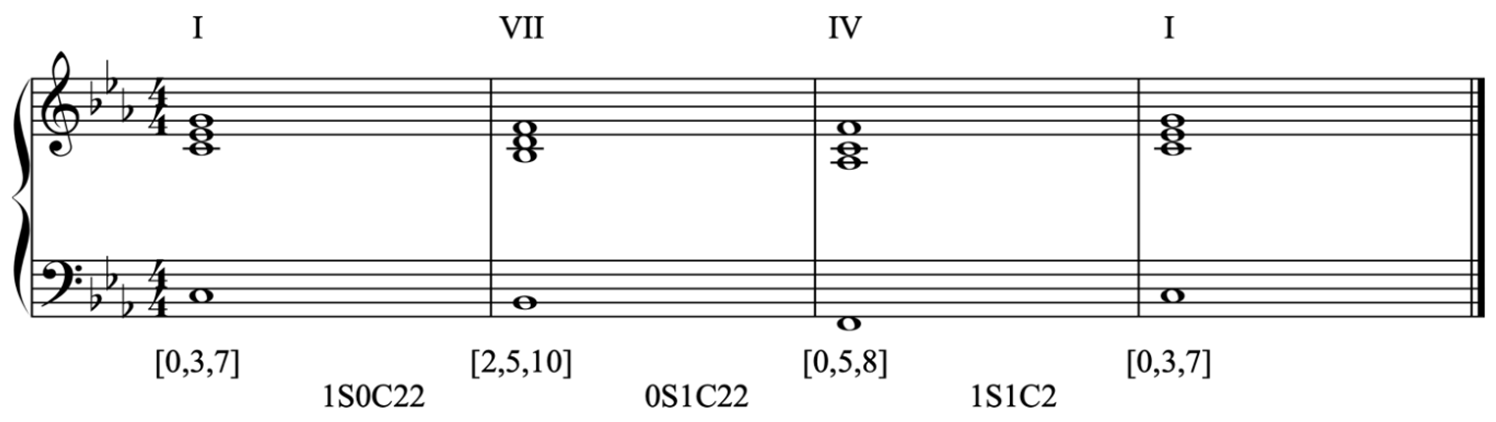

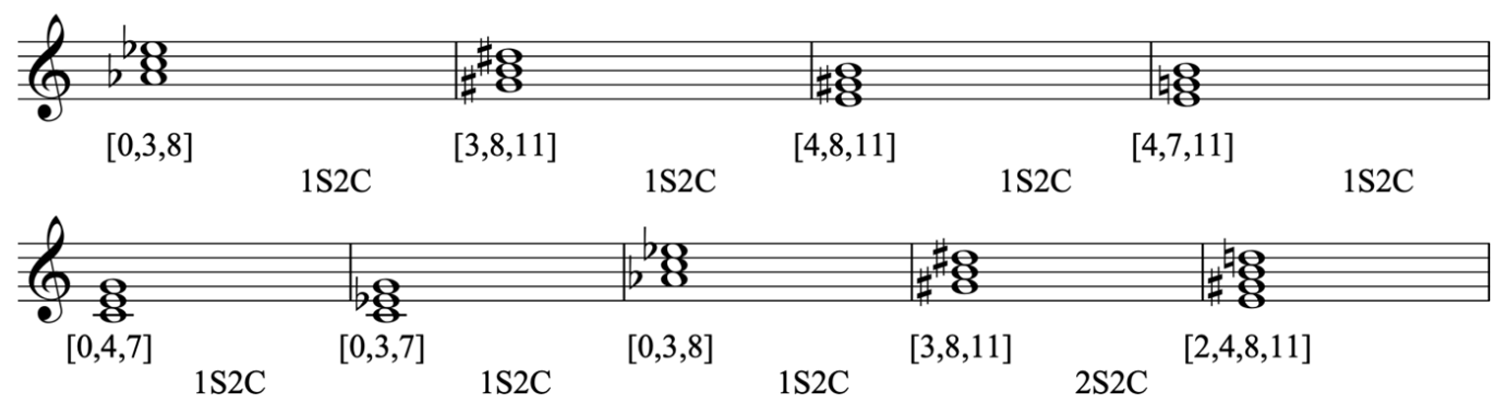

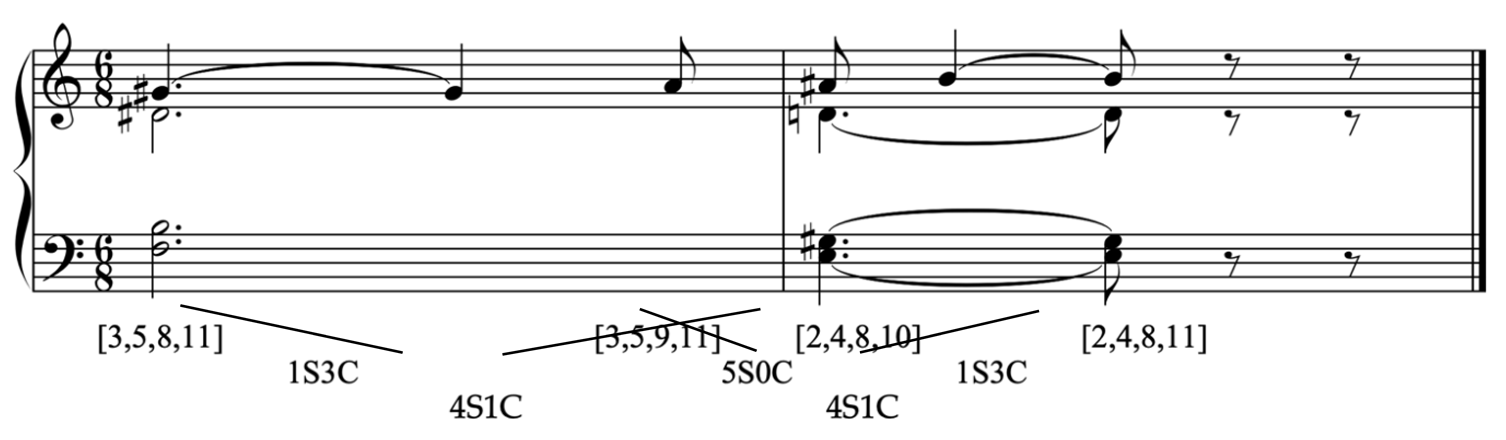

The semitone is the most important parameter for analyzing the relation between two chords, while the second important parameter is the common tone. The quantity of common tones between the chords determines their degree of similarity. The research by Andrew J. Milne and Simon Holland (2016) supports this perspective by experiment, “the results indicate that the number of common tones between chords (abstracted across voices and octaves) is a highly effective predictor of their perceived distance.” For example, consider three pairs of chords, as shown in the following example (fig. 1). The first two pairs each contain two common tones, while the third pair contain only one common tone. From this, we can infer that the first two pairs of chords exhibit a higher degree of similarity to each other in comparison to the third pair.

Figure 1.

Comparison of three pairs of chords.

Figure 1.

Comparison of three pairs of chords.

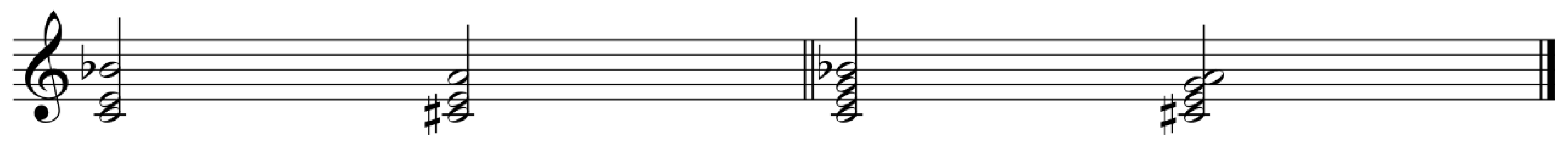

Additionally, the quantity of common tones does not affect the quality of the semitonal movement. Let us consider two pairs of chords: one pair has one common tone and two semitones, whereas another pair has two common tones and two semitones. From the perspective of semitones, the degree of tendency generated by these two pairs of chords is identical. Whether there is one common tone or two common tones, the changes we perceive primarily arise from the semitonal movements, specifically those from C to C♯ and from B♭ to A, as illustrated in the following example (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of two pairs of chords.

Figure 2.

Comparison of two pairs of chords.

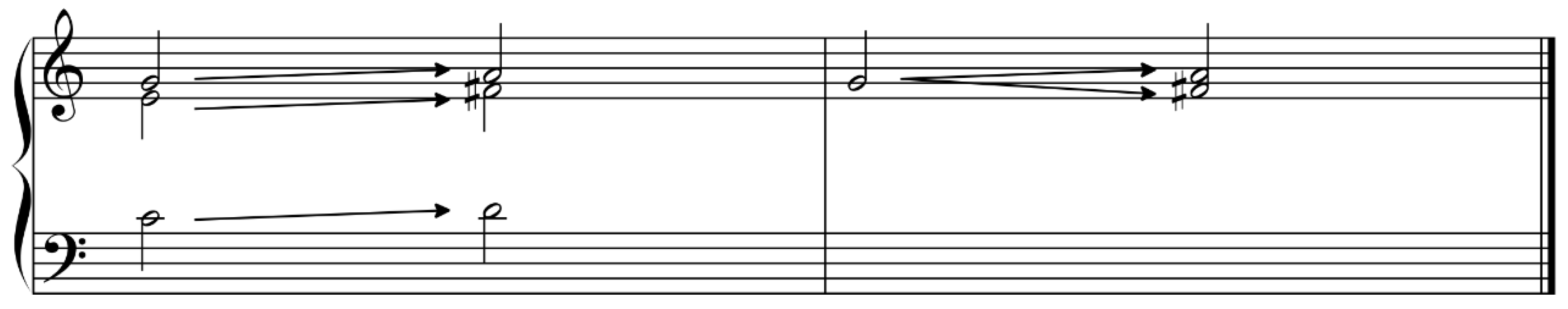

It is important to note that we are not examining chord tones through traditional voice leading methods, which typically involve a direct one-to-one voice mapping from one chord to another. Instead, our focus is on the potential semitonal movements that exist between two chords. Consider the C major chord and the D major chord in the following example (fig. 3). From the perspective of voice leading, there are three voice leading movements: C to D, E to F♯, and G to A. In this context, there seems to be no semitonal movement present. However, there is indeed a semitone between G and F♯. While G can move to A, it can also move to F♯. The movement from G to A does not negate the movement from G to F♯, as this semitonal movement is indeed present.

Figure 3.

The possibility of semitonal movement.

Figure 3.

The possibility of semitonal movement.

Voice leading, originating from counterpoint, has served as a fundamental rule of voice writing since its inception. It has evolved from 16th-century modal counterpoint through 18th-century Bach-style counterpoint and continues to influence the rules of voice writing in harmonic composition. Voice leading functions as an artificial and intentional choice for disassembling the notes of a chord into point-to-point note streams that connect parsimoniously to the notes of the subsequent chord. “Voice leading is a codified practice that helps musicians craft simultaneous musical lines so that each line retains its perceptual independence (Huron 2016:14).” However, these note streams do not accurately reflect the objective state of the relation between two chords, nor do they reflect the actual perception of these relations by human auditory system. Therefore, voice leading has limitations when it comes to evaluating the relation between two chords. Overemphasizing the role of voice leading in chord relations may lead to an oversight of the existence of semitonal movements.

While various studies have investigated how humans perceive different voice parts as independent auditory streams—by examining factors such as toneness, harmonic fusion, auditory masking, continuity, pitch proximity, pitch co-modulation, onset asynchrony, limited density, timbral differentiation, source location, attention, and expectation—Huron’s research (2016) stands out. From a music theorist’s perspective, he provides a compelling argument regarding the fundamental principles of the human auditory system that govern the perception of musical textures. Nevertheless, these insights do not diminish the viewpoints and conclusions presented in this article. The focus of this article is not on how voice leading influences chord relations or how the auditory system translates chord movement into auditory stream segregation. Instead, this article uses both clear and subtle semitonal movements as a foundation to compare and evaluate the degree of tendency between chords. While the different arrangements of chord notes and the varying movements between chords may produce slight differences in harmonic effects, they do not influence the outcomes of examining chord relations.

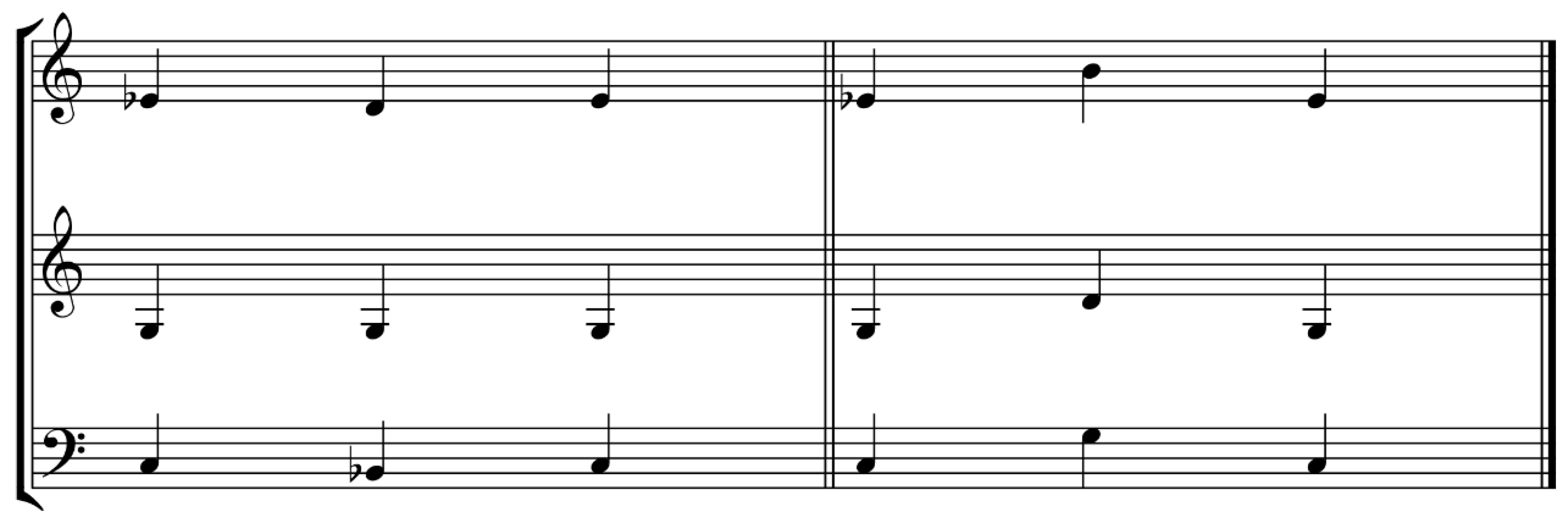

For example, regardless of how a C minor triad is arranged and connected with a G minor triad, the degree of tendency between them will not exceed that between a C minor triad and a G major triad. In the following example (fig. 4), the voice leading between a C minor triad and a G minor triad is parsimonious, while the voice leading between a C minor triad and a G major triad is completely non-parsimonious. However, we can still perceive that the G major triad resolves to the C minor triad with a tendency characteristic of a dominant chord, resulting in a stronger degree of tendency.

Figure 4.

Parsimony vesus non-parsimony.

Figure 4.

Parsimony vesus non-parsimony.

The reason is that the auditory system is capable of not only segregating auditory streams but also unifying them into a coherent sound. These two sensory experiences of sound exist simultaneously. Goldenberg (2016) holds a similar viewpoint, questioning the reliance of traditional harmonic analysis on voice leading. His study suggests that harmonic organization can still be interpreted through logical frameworks in the absence of voice leading. Poulin-Charronnat (2005) also holds a similar viewpoint. Through his auditory experiments, he evaluated whether the size of the priming effect would be influenced by good versus bad voice leading. The results revealed a significant main effect of voice leading on participants’s performances, with faster responses for normal voice leading. However, this factor did not affect the strength of the harmonic priming effects.

Therefore, we need to liberate semitonal movements from the constraints of traditional voice leading rules and recognize their core role. The prerequisite for examining semitones is that, if they exist, they must be acknowledged and counted. This method effectively addresses the challenge of connecting chords with varying numbers of voices. When semitones are present, they indicate a degree of tendency between chords, whereas common tones suggest a relation of similarity between them. Based on this understanding, when analyzing the relation between two chords, semitones should be treated as the primary parameter, followed by common tones. In Neo-Riemannian transformation theory, particularly in Cohn’s (1996) study of the semitone transformations between triads, Cohn’s (1997) study on the semitone transformations between trichords, and Childs’s (1998) study on the semitone transformations between seventh chords, it is evident that the transformations between chords focus on semitones. This aligns with the viewpoint in this article. However, the difference is that this article directly discribes the relations between chords rather than describing them through a process of chord transformations. This distinction highlights the theoretical concept proposed in this article as being different from the Neo-Riemannian transformation system.

In addition to semitones and common tones, it is essential to examine other interval distances. If semitones determine tendency and common tones indicate similarity, then the remaining intervals assist in measuring the degree of separation between chords. According to the Principle of Proximity, it is essential to identify the nearest note to evaluate the distances of other intervals. For example, in the first pair of chords of the following example (fig. 5), the note G is closer to A than to E. Therefore, the other interval between these two notes in this pair of chords is a major second. In the second pair of chords, the distance between the note G and A♯ is equal to the distance between G and E. Thus, the other interval in this pair of chords can be classified as either an augmented second or a minor third. By comparing these two pairs of chords, we can observe that the degree of separation between the second pair of chords is greater than that of the first pair.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the separation degree for two pairs of chords.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the separation degree for two pairs of chords.

Representation of Chord Relations

In this article, capital letter S denotes semitones, capital letter C denotes common tones, and the numbers placed at the end will indicate other intervals. For convenience in examination, pitch-class sets will be employed to represent chords, arranging the pitch classes in ascending order to form an ordered set. For example, consider the C major triad represented as [0, 4, 7] and the F major triad as [0, 5, 9]. Next, we will calculate the differences by subtracting each pitch class in the former chord from the corresponding nearest pitch class in the latter chord. If the result is 0, it indicates the common tone. If the result is 1 or -1, it indicates the semitone. If the result is greater than 1 or less than -1, it indicates other interval. Specifically, a result of 2 corresponds to a whole tone (two semitones), while a result of 3 corresponds to a minor third (or augmented second), and so on. Let us analyze the differences between the C major triad [0, 4, 7] and the F major triad [0, 5, 9]. The result between the first pitch classes is 0-0=0, indicating one common tone. The result between the second pitch classes is 5-4=1, indicating one semitone. The result between the third pitch classes is 9-7=2, indicating one whole tone. Therefore, the relation between these two chords can be represented as 1S1C2, which will be referred to as the “Chord Relation Value (CRV)” throughout this article. Additionally, if there are additional intervals, they should be listed at the end. For example, 0S1C23 represents zero semitones, one common tone, one whole tone, and one minor third (or augmented second).

The rational for subtracting the former chord from the later chord, rather than the reverse, is that the relation between the two chords is not examined according to the principles of voice leading, as discussed earlier. It is not the case that every note of the former chord develops into every note of the later chord. Instead, the later chord, as a whole, establishes a contrasting relation with the former chord.

When a triad precedes a seventh chord, it is essential to ensure that all four pitch classes of the seventh chord are calculated in relation to the nearest pitch classes of the triad. For example, consider the A major chord [1, 4, 9] and the D dominant seventh chord [0, 2, 6, 9]. After calculating (0 - 1 = -1, 2 - 1 = 1, 6 - 4 = 2, 9 - 9 = 0), resulting CRV is 2S1C2. Conversely, when the seventh chord appears first and the triad follows, it is only necessary to calculate the three pitch classes of the triad in relation to the nearest pitch classes of the seventh chord. For example, if we place the D dominant seventh chord before the A major chord, after calculating (1 - 0 = 1, 4 - 2 = 2, 9 - 9 = 0) ,the resulting CRV is 1S1C2. From the perspective of the results, the different positions of the two chords significantly affect the CRV. Furthermore, this also proves that subtracting the former chord from the later chord is a correct choice. As a triad is followed by a more complex seventh chord, the potential for semitonal movement should increase rather than decrease.

When one chord note of the later chord has both common tone relation and semitonal relation with one chord note of the former chord, both relations must be counted. Based on the previous argument, the existence of semitones should be acknowledged and counted, while common tones represent the identical elements of the two chords that cannot be overlooked. Therefore, we cannot choose one of them, we need to consider both. For example, a C major-seventh chord [0, 4, 7, 11] is followed by a C major triad [0, 4, 7]. The pitch class 0 in the C major triad is a common tone with the pitch class 0 in the C major-seventh chord, and it is also a semitonal relation with pitch class 11 in the C major-seventh chord. As a result, the CRV between these two chords is 1S3C.

When one chord note of the later chord has a semitonal relation with two chord notes of the former chord, both semitones need to be counted. Both semitonal movements will engage two voices simultaneously, rather than selecting one while ignoring the other. For example, a D♭ dominant seventh chord [1, 5, 8, 11] is followed by a C major triad [0, 4, 7]. The pitch class 0 in the C major triad is a semitonal relation with both pitch classes 1 and 11 in the D♭ dominant seventh chord. Consequently, the CRV between these two chords is 4S0C. If we were to count only one semitone, the CRV would become 3S0C, which would also be the CRV between the D♭ major triad and the C major triad. This would lead to an inaccurate representation of the chord relation and fail to reflect the differences between the D♭ dominant seventh chord and the D♭ major triad. It would also violate the principle that if semitones exist, they must be acknowledged and counted.

By employing this method, we can effectively examine the relations between chords with varying numbers of voices.

Description of Chord Relations

After establishing a method for representing chord relations, CRV can be utilized to describe the relation between two chords. Firstly, the quantity of semitones between two chords significantly affects their degree of tendency. Generally, the greater the quantity of semitones, the stronger degree of tendency. Secondly, the quantity of common tones between the chords determines the degree of similarity and shared harmonic foundation. This aspect not only allows us to examine the common tone relation of a given pair of chords but also enables comparisons of the quantity of common tones among multiple groups of chords. Such comparisons can reveal deeper similarities in the use of common tones across different harmonic contexts.

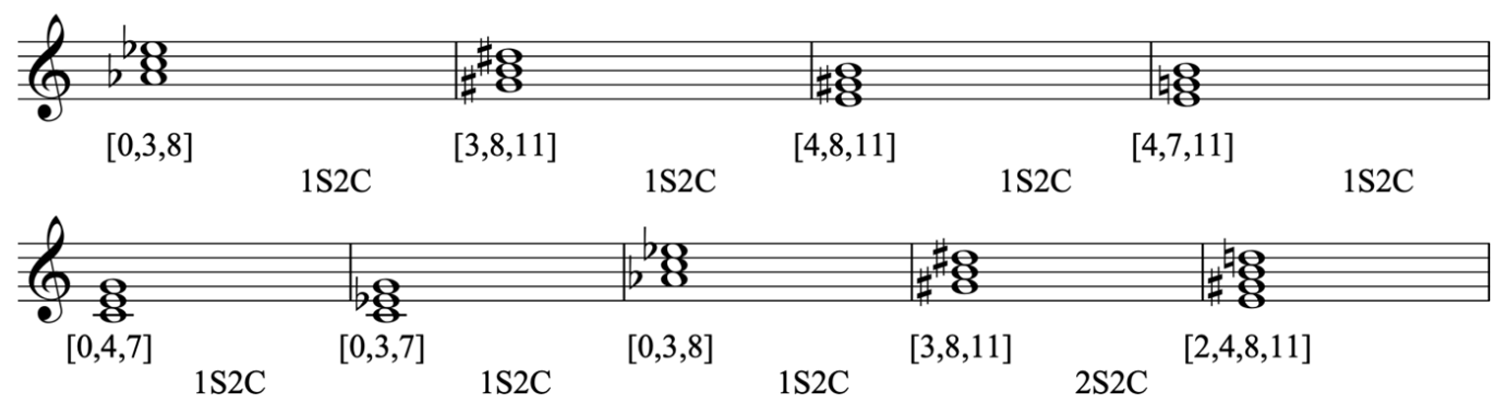

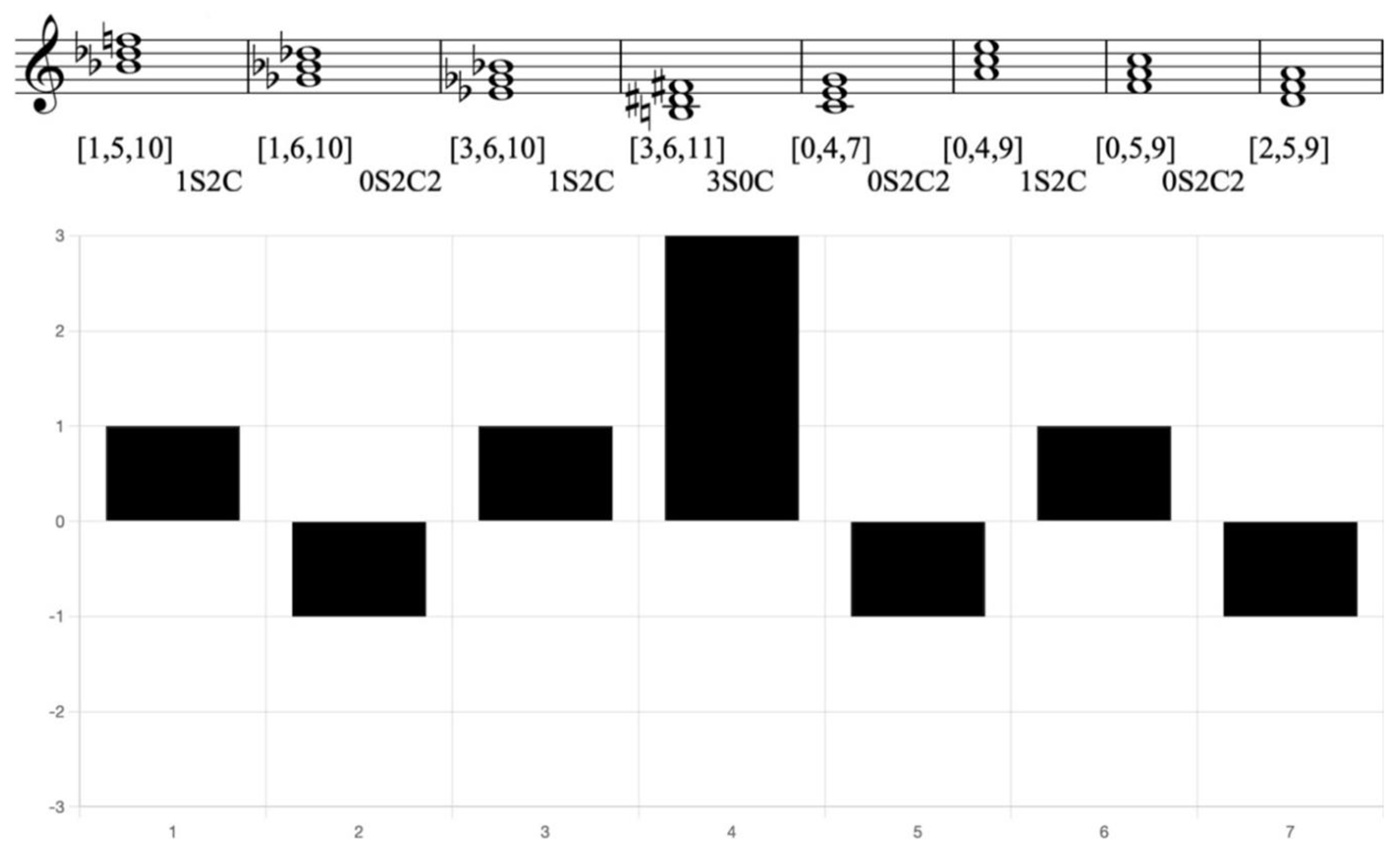

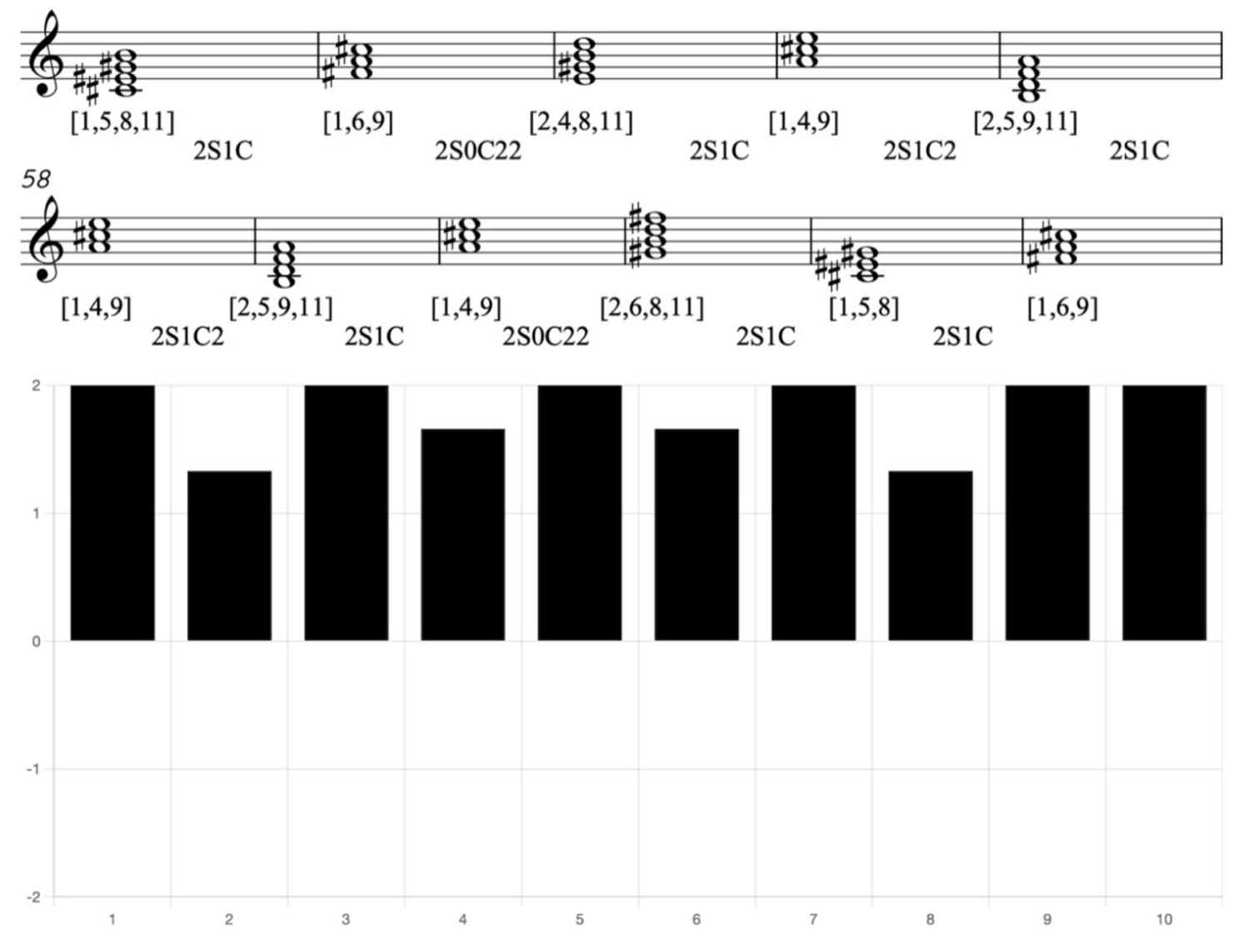

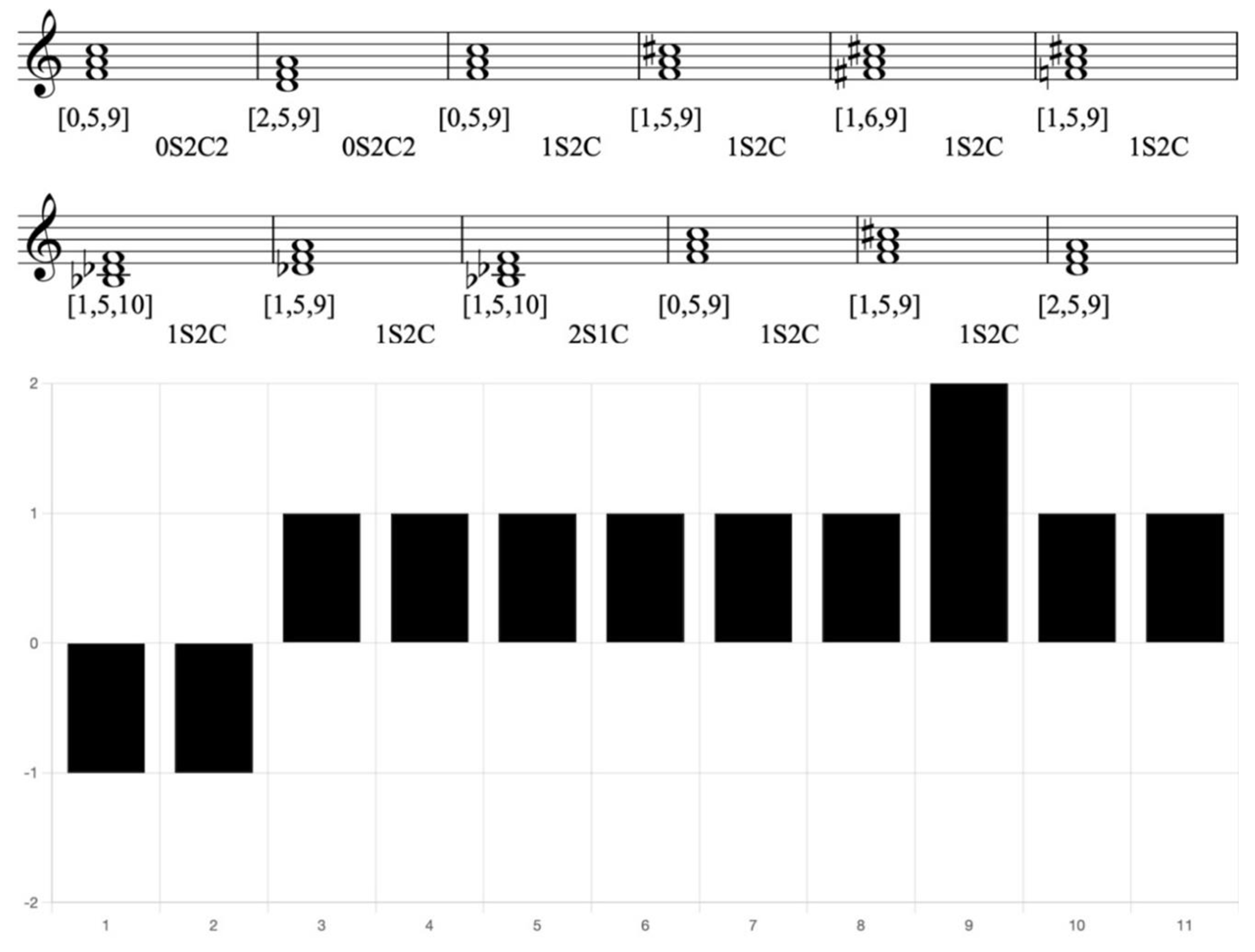

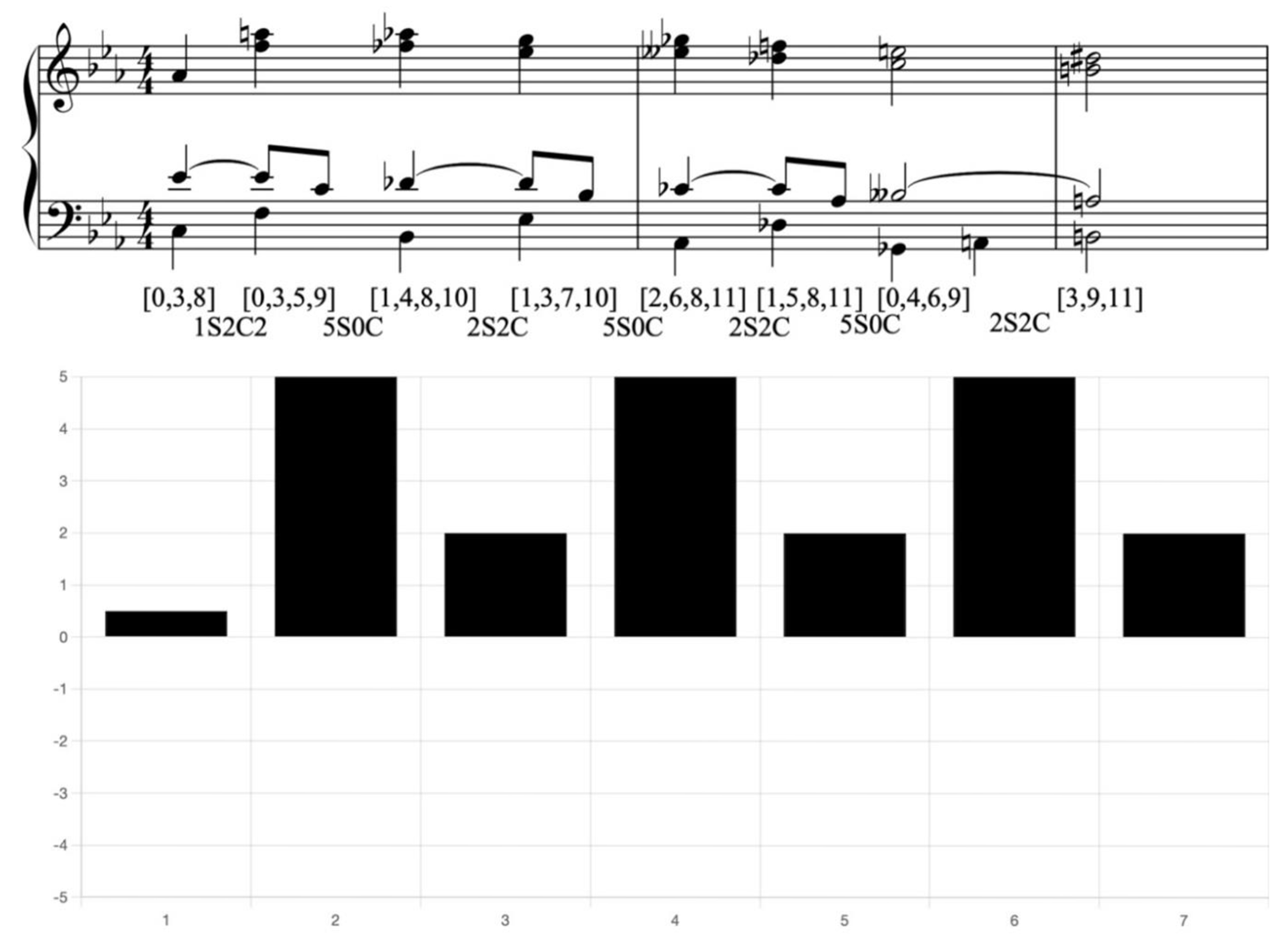

For example, let us compare a pair of chords: one with a CRV of 1S2C (the C major triad and the E minor triad) and the other with a CRV of 0S2C2 (the C major triad and the E diminished triad). In the first pair (the C major and the E minor), there is one semitone between the two chords, while the second pair features a whole tone between them. Despite this difference in distance, both pairs of chords contain two common tones. This commonality indicates that, in terms of the quantity of common tones, there are notable similarities in the harmonic movement between these two pairs of chords. In some musical works, the composer’s intention to express similarities between chords can be clearly observed. In the following example, sequences of chords maintain a 2C relation. Despite the presence of a seventh chord at the end of this passage, the 2C relation is preserved throughout the chord progression. This choice reflects Brahms’s intention to maintain a cohesive and similar harmonic quality.

Example 1. Reduction of Brahms, Concerto for Violin and Cello, Op.102, 1st mvt., mm. 270-279.

Other intervals can describe the degree of separation between chords. For example, let us compare the C major triad with the D♯ diminished triad (with CRV of 2S0C3) and the C major triad with the D♯ minor triad (with CRV of 2S0C2). In this comparison, the C major triad is positioned further from the D♯ diminished triad than from the D♯ minor triad.

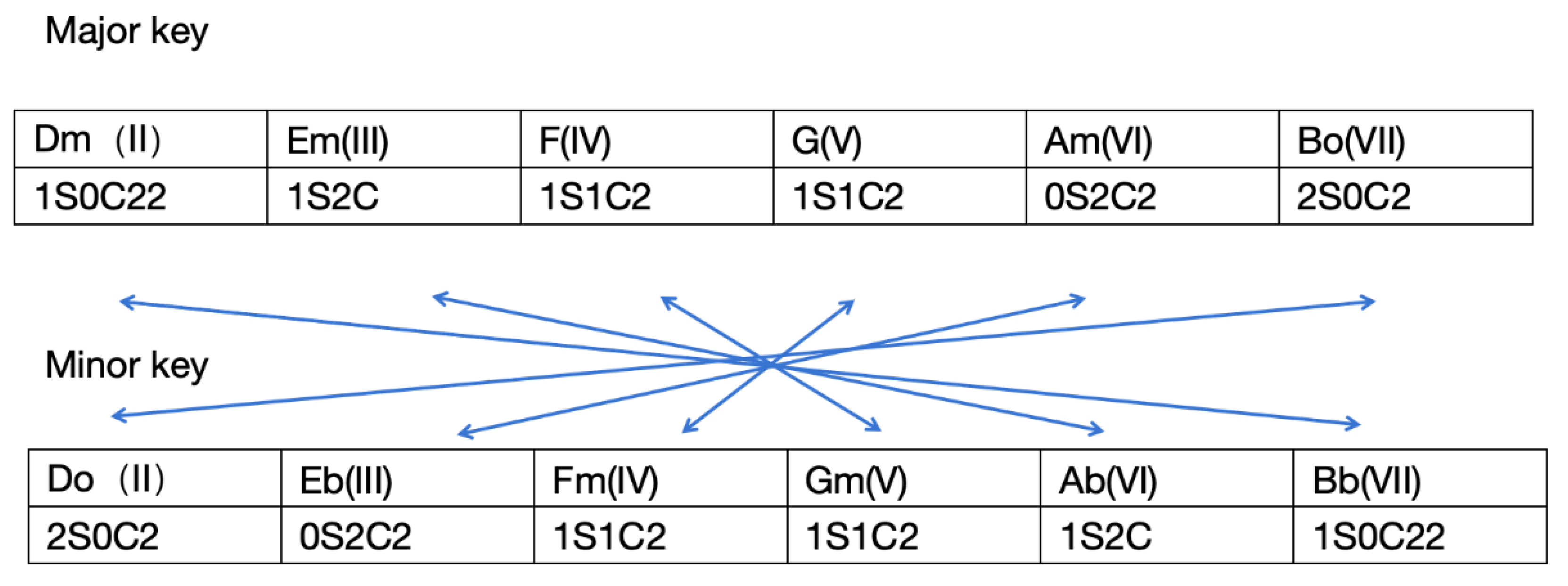

The following CRVs outlines all possible CRVs between two triads, using letter O to indicate other intervals and accounting for their quantities.

0S3C0O: This CRV represents the closest pair of triads, as they are completely identical, meaning they are equal chords.

1S2C0O and 0S2C1O: Both CRVs contain two common tones. The 1S2C0O, which includes one semitone, indicates a pair of chords that are closer than the 0S2C1O, which contains no semitones.

2S1C0O, 1S1C1O, and 0S1C2O: In this group, there is one less common tone than in the previous group, indicating a further distance between the triads. Within this group, the chord relation becomes closer when there are more semitones.

3S0C0O, 2S0C1O, and 1S0C2O: These CRVs have no common tones. Consistent with the previous group, the chord relation becomes closer when there are more semitones.

0S0C3O: This CRV represents the most distant pair of chords, as there are no common tones and no semitones.

In conclusion, the more common tones there are between two chords, the closer their relation. When the quantity of common tones is identical, the relation between the chords is influenced by the quantity of semitones. The more semitones present, the greater degree of tendency of the relation. In cases where the quantity of semitones is also identical, the relation can be further evaluated by considering the quantity of other intervals. The fewer other intervals there are, the closer the relation. Finally, when the quantity of other intervals is the same, the relation is determined by the maximum distances of these intervals. The smaller the maximum distances, the closer the relation. More complex relations between chords can be analyzed using the same principles.

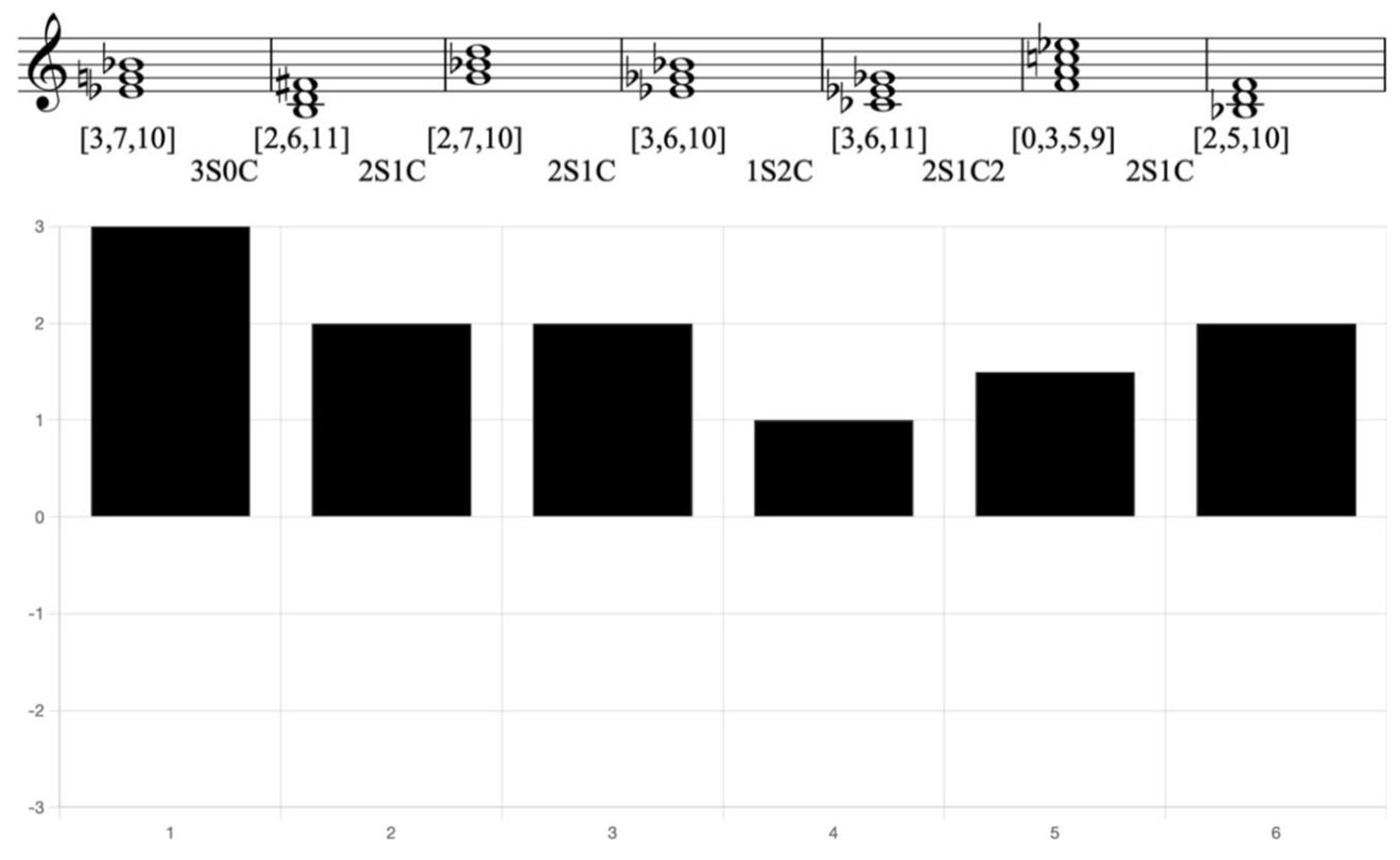

To provide a more visual representation, we can create a bar chart based on the CRVs mentioned above to display the degree of tendency between chords. In the following bar chart (fig. 6), the positive numbers above the X-axis represent the quantity of semitones, which is directly proportional to the degree of tendency between chords. When the quantity of semitones is the same, a greater number of other intervals will reduce the degree of tendency between chords. For example, the position of 1S1C1O is lower than that of 1S2C0O, while 1S0C2O is even lower than both. The negative numbers below the X-axis represent the quantity of other intervals in the CRVs that do not include semitones. These numbers are inversely proportional to the degree of tendency between chords. When extending the analysis to seventh chords or even more complex structures, a similar method can be applied to create bar charts.

Figure 6.

Chord relation value bar chart.

Figure 6.

Chord relation value bar chart.

Characteristics of Chord Relations within Tonal Context Observed Through CRV

While CRV theory originally aimed to analyze relations between chords within a non-tonal context, its application within a tonal context has revealed several noteworthy characteristics regarding the relations within triads and seventh chords. This discovery not only demonstrates the effectiveness of CRV theory in analyzing chord relations in a tonal context but also offers an interesting perspective on how to describe these chord relations.

The Relations of the I Chord with Other Diatonic Chords in a Major Key

For example (table 1), in a major key, the CRVs between the tonic chord and other diatonic chords are as follows:

Table 1.

The CRVs between the tonic chord and other diatonic chords.

Table 1.

The CRVs between the tonic chord and other diatonic chords.

| II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

| 1S0C22 |

1S2C |

1S1C2 |

1S1C2 |

0S2C2 |

2S0C2 |

From the perspective of harmonic tendency, the VII chord has the strongest degree of tendency to the tonic chord. The relation between the tonic chord and the IV and V chords is the most balanced, as they each have one semitone, one common tone, and one other interval of major second. Although the II chord also has one semitone with the tonic chord, the other intervals of two major seconds create a degree of separation that is much greater than its degree of tendency, thus making its relationship with the tonic chord the most distant. The III and VI chords share two common tones with the tonic chord, making them the most similar to the tonic and validating the concept of functional groups in traditional harmony.

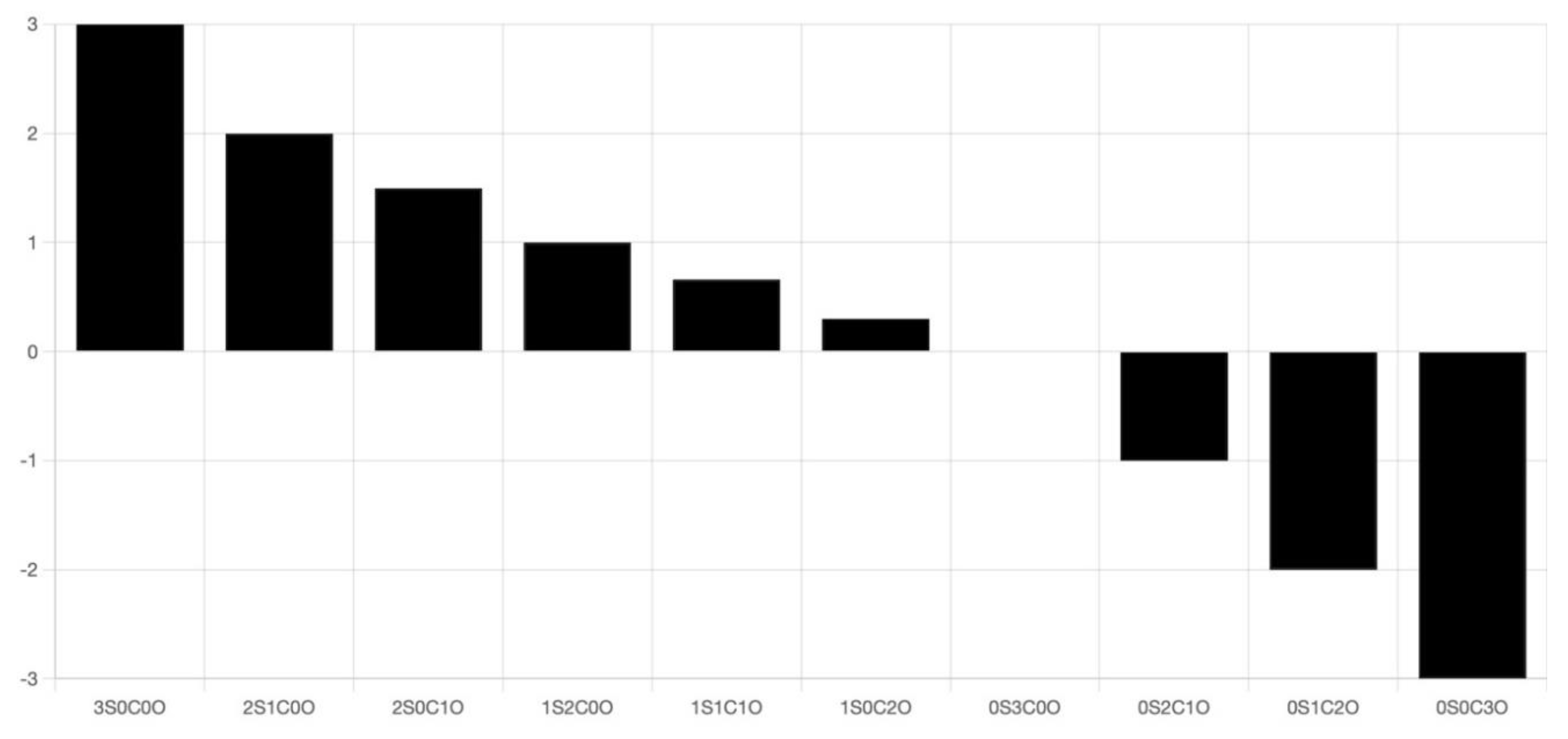

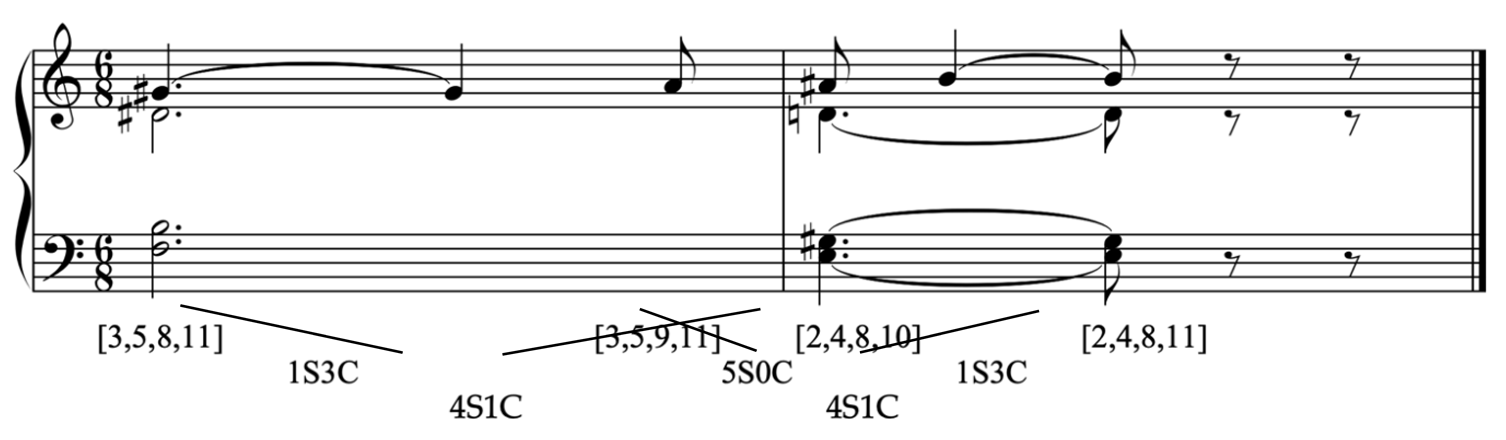

The Mirror Phenomenon of CRVs Between Major and Minor Key

CRV reveals a fascinating symmetry between major and minor key, referred to as the “Mirror Phenomenon.”

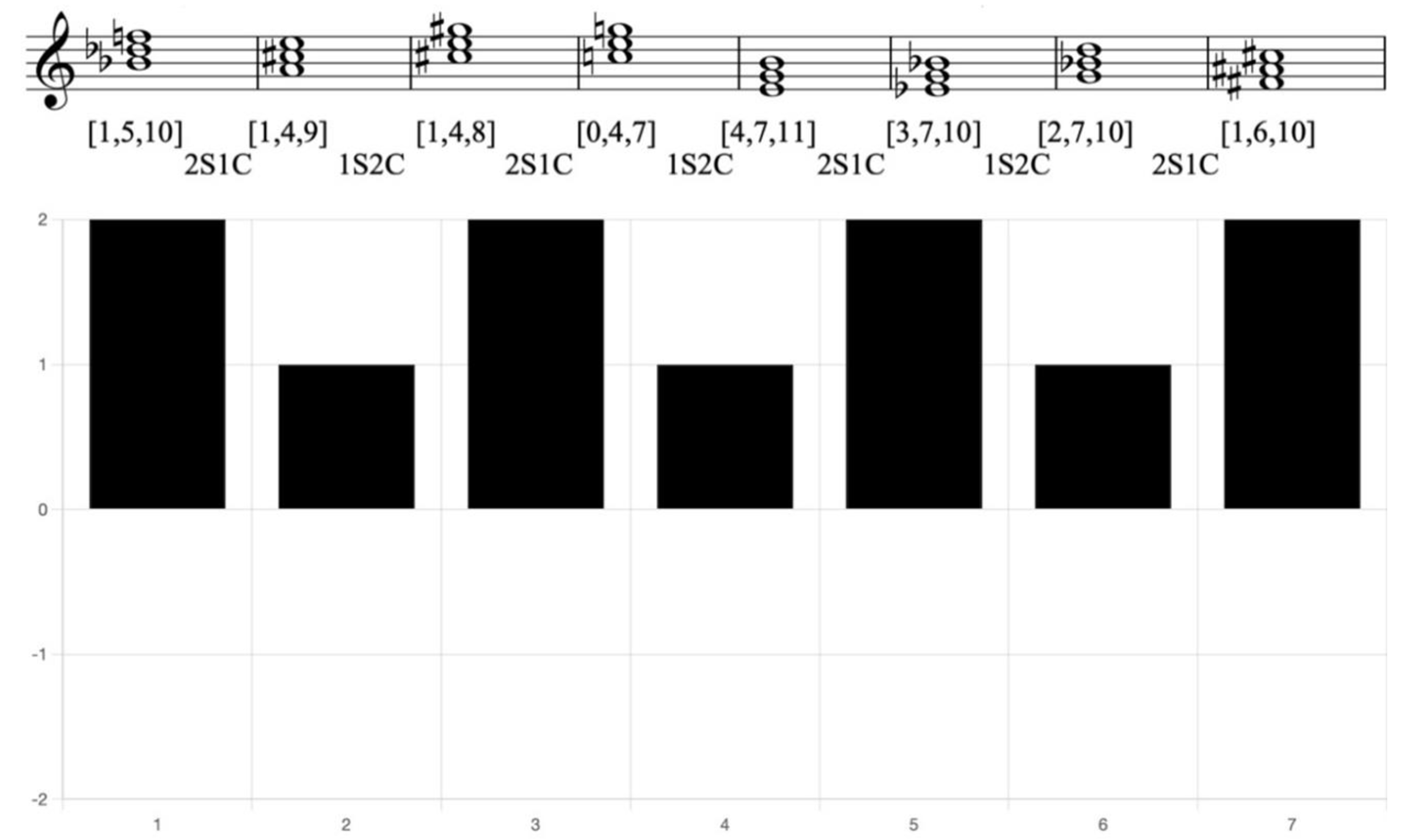

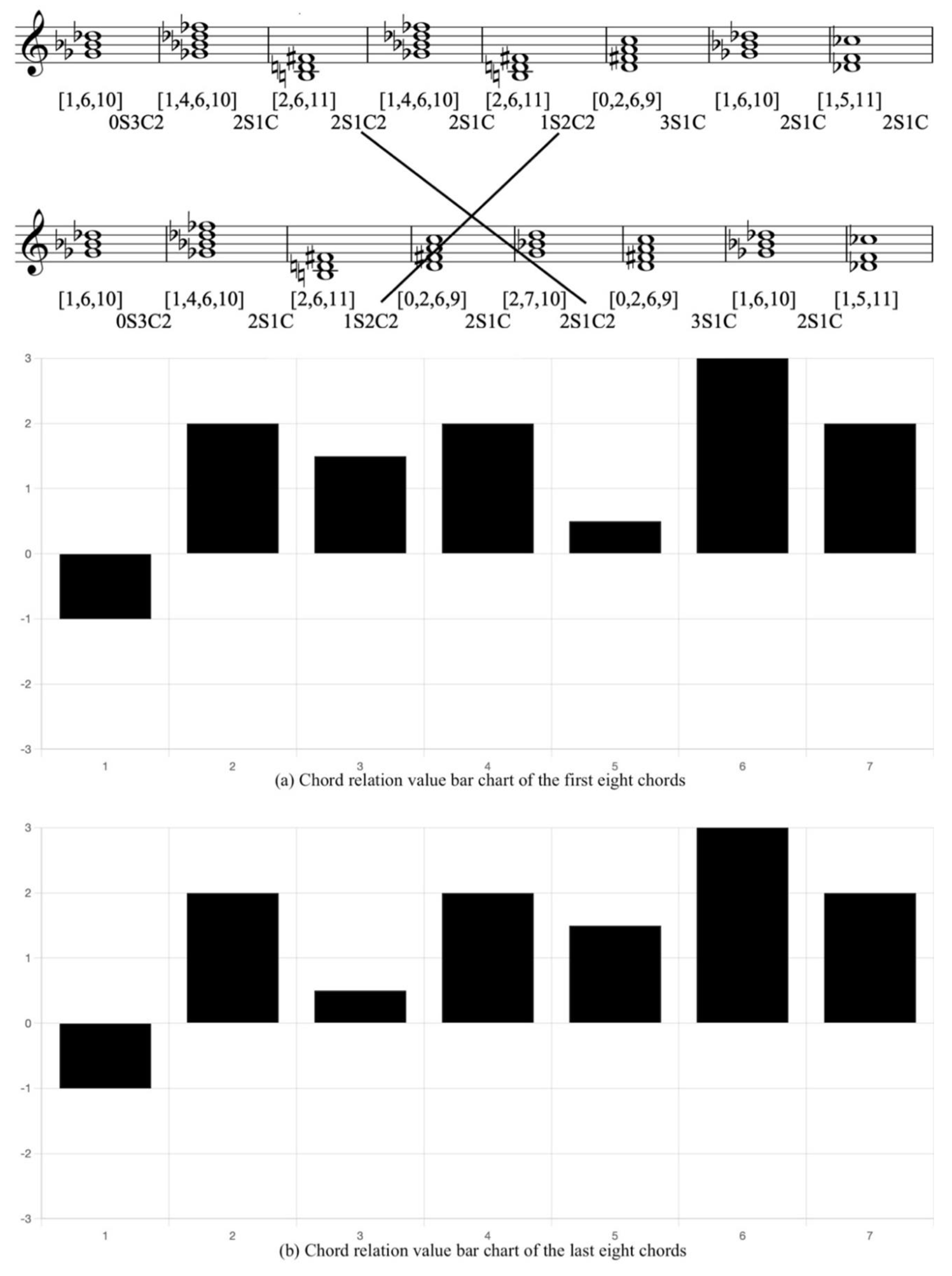

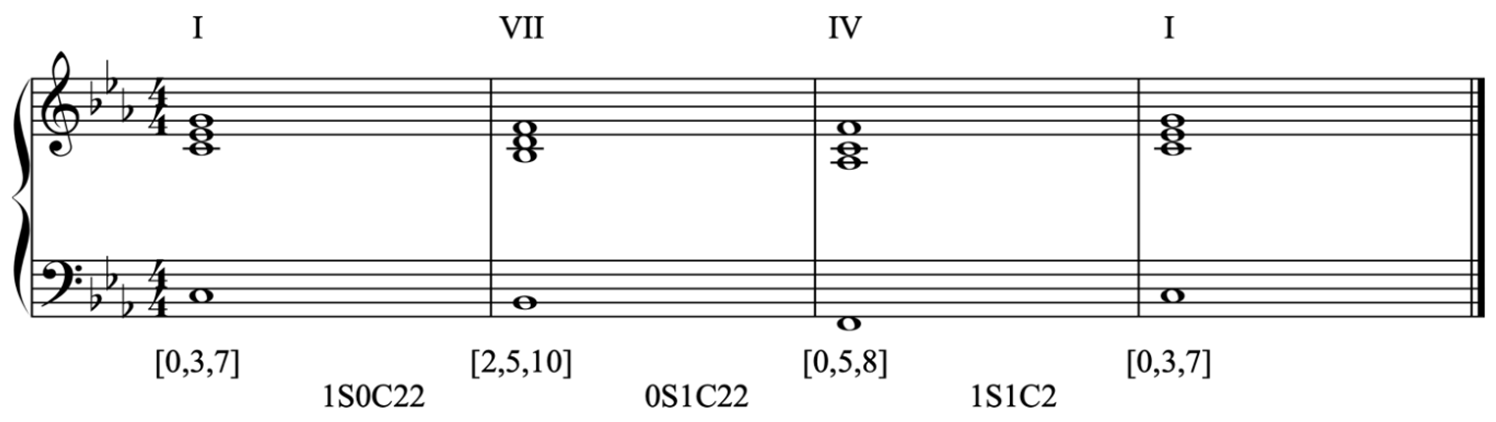

The CRVs between the I chord and other diatonic chords in a major key are mirrored by the CRVs between the I chord and other diatonic chords in a minor key (fig. 7). All the CRVs identified in a major key also exist in a minor key, sharing the identical harmonic intension. This phenomenon helps us better understand certain harmonic progressions. For example, in the following example, the I-VII-IV-I in a minor key is not a common harmonic progression, and it is difficult to provide a convincing explanation for the movement of these chords using traditional functional harmony perspective. However, if we mirror this by substituting the VII chord and IV chord of the minor key with the II chord and IV chord of the major key respectively, it turns the I-II-V-I progression in a major key, which is one of the most common chord progressions. Furthermore, in a major key, the CRVs between the chords in I-II-V-I are 1S0C22, 0S1C22, and 1S1C2, which are completely identical to the CRVs between the chords in I-VII-IV-I in a minor key.

Figure 7.

Mirror CRVs between C major and C minor.

Figure 7.

Mirror CRVs between C major and C minor.

Example 2. Reduction of Beyond, The Grand Earth, chorus, in C minor.

The Parallel Major and Minor Keys

The exploration of the CRVs provides insight into the changes in chord relations that occur when borrowing chords between parallel major and minor keys. This examination reveals how borrowed chords can enhance harmonic tendency and create stronger cadences.

For example, the CRV between the F major triad and the G major triad in C major is 1S0C22, while the CRV between the F minor triad and the G minor triad in C nature minor is 1S0C22. In contrast, the CRV between the F minor triad and the G major triad in C harmonic minor is 2S0C2. Among these progressions, the movement from the F minor triad to the G major triad demonstrates the strongest tendency. This is due to the introduction of the dominant chord (G major triad) from the parallel C major, transforming C natural minor into C harmonic minor. This transformation is significant as it creates a stronger progression within the harmonic context of the minor key. Similarly, introducing the subdominant chord from the parallel minor key can influence the major key. The transformation of the natural major scale into the harmonic major scale also results in a stronger progression within the harmonic context of the major key.

Harmonic Progressions of V7-I and VII7-I

The V7 chord resolving to the I chord in both major key and minor key has the same CRV, which is 2S1C2. In contrast, when the V chord is presented as a triad, the CRVs differ significantly. In the major key, the CRV for the V triad resolving to I chord is 1S1C2; In the minor key, the CRV for the V triad resolving to I chord is 2S1C. The V7 chord, being a more complex structure, contributes to a greater degree of tendency and results in a consistent resolution to the tonic chord across both major and minor keys. Similarly, the CRVs for the VII diminished-seventh chord resolving to the I chord in both major and minor keys are as 3S0C2. This explains why the VII chord in the major key is often used as a diminished-seventh chord in harmonic major, as it provides identical degree of tendency for both major and minor keys.

Secondary Dominant Chords

In tonal harmony, the introduction of secondary dominant chords can create more semitones, enhancing the degree of tendency of the harmonic progression. For example, when comparing the progressions V/V-V and II-V, the CRVs are 1S1C2 and 0S1C2, respectively. The harmonic tendency of the progression V/V-V is stronger than that of II-V, as V/V introduces a semitonal movement, contributing to a more dynamic harmonic progression.

The Issue of Harmonic Function in CRV

When using CRV to analyze chord relations within a tonal context, it is essential to consider the characteristics of functional harmony, while CRV may falls short in harmonic function in some situation. For example, the I chord forms fourth and fifth relations with both the IV chord and the V chord in a major key, resulting in identical CRVs of 1S1C2 for both pairs. Consequently, when root movement is not considered, the perceived degree of tendency between these chords appears equivalent. However, traditional music theory suggests that within a tonal context, the relation between the V chord and the I chord is typically perceived as closer than that between the IV chord and the I chord. This perception arises from the function of the V chord, which contains a leading tone that resolves to the root note of the I chord. This semitonal movement enhances the resolution from the V chord to the I chord, establishing a stronger harmonic movement. From this perspective, the CRVs for the IV-I and V-I should reflect this difference. Otherwise, the unique characteristics of their relations to the I chord would not be adequately expressed. In summary, incorporating an understanding of functional harmony into CRV analysis allows for a more comprehensive interpretation of chord relations, ensuring that the characteristics of tonal harmony are accurately represented.

Comparing the E minor triad and the C major triad, as well as the G dominant seventh chord suspended fourth(G-C-F) and the C major triad, we observe that both pairs of chords share two common tones and contain a semitonal movement. At first glance, if we only examine the resolution of the leading tones, it might appear that the E minor triad has a stronger degree of tendency to resolve to the C major triad. However, from the perspective of harmonic function, the G dominant seventh suspended fourth chord exhibits a much stronger degree of tendency to resolve to the C major triad. This chord serves as a dominant chord that naturally seeks resolution to the tonic due to its function role within the tonal context, making it a more compelling and expected progression compared to the E minor triad. This example demonstrates the importance of considering harmonic function when using CRV for analysis in a tonal context. While CRV provides insights into the chord relations based on intervallic relations, they may not fully capture the nuances of harmonic function that influence how chords are perceived and resolved in tonal context.

Case Analysis

Between Triad Chords

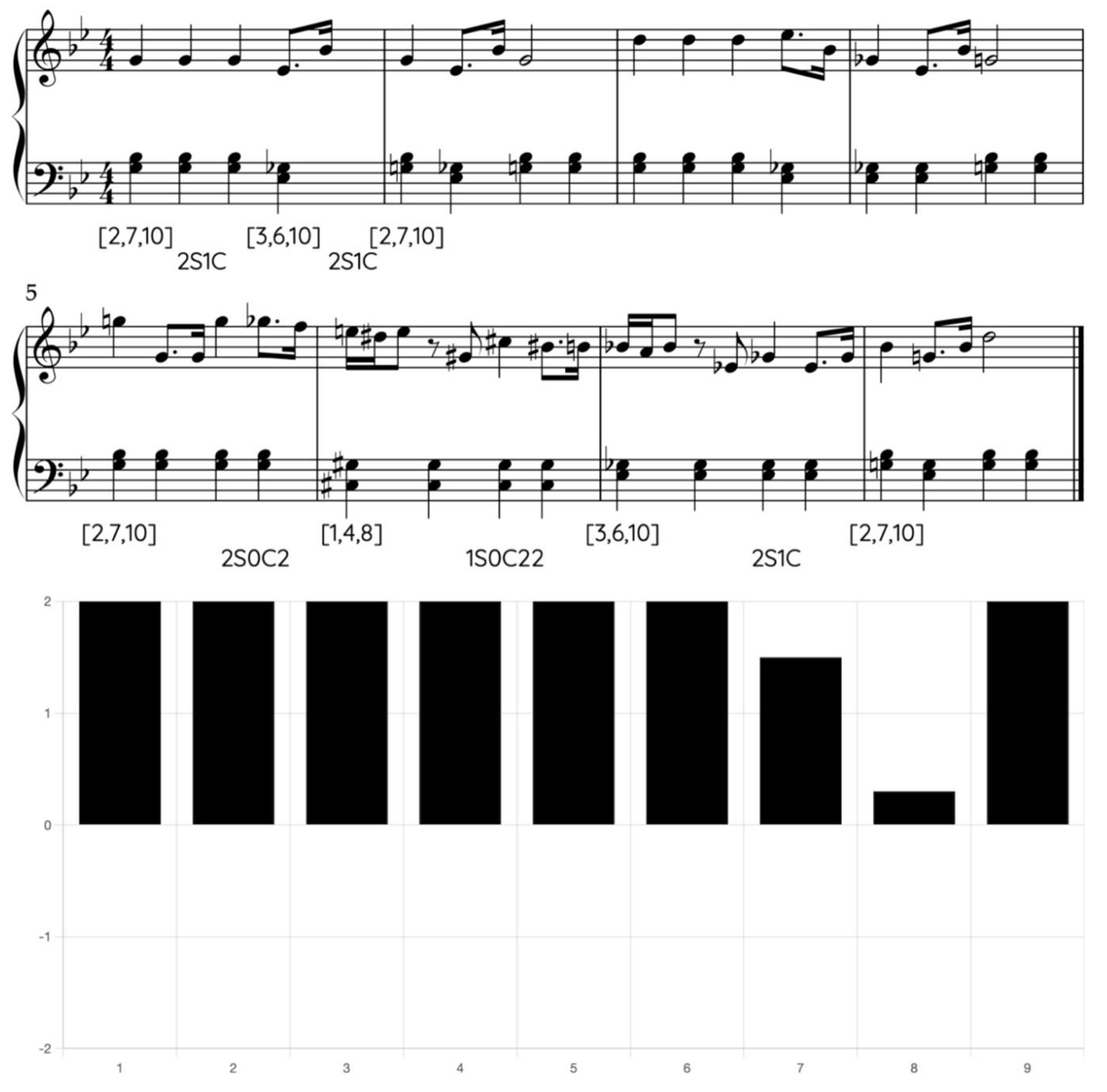

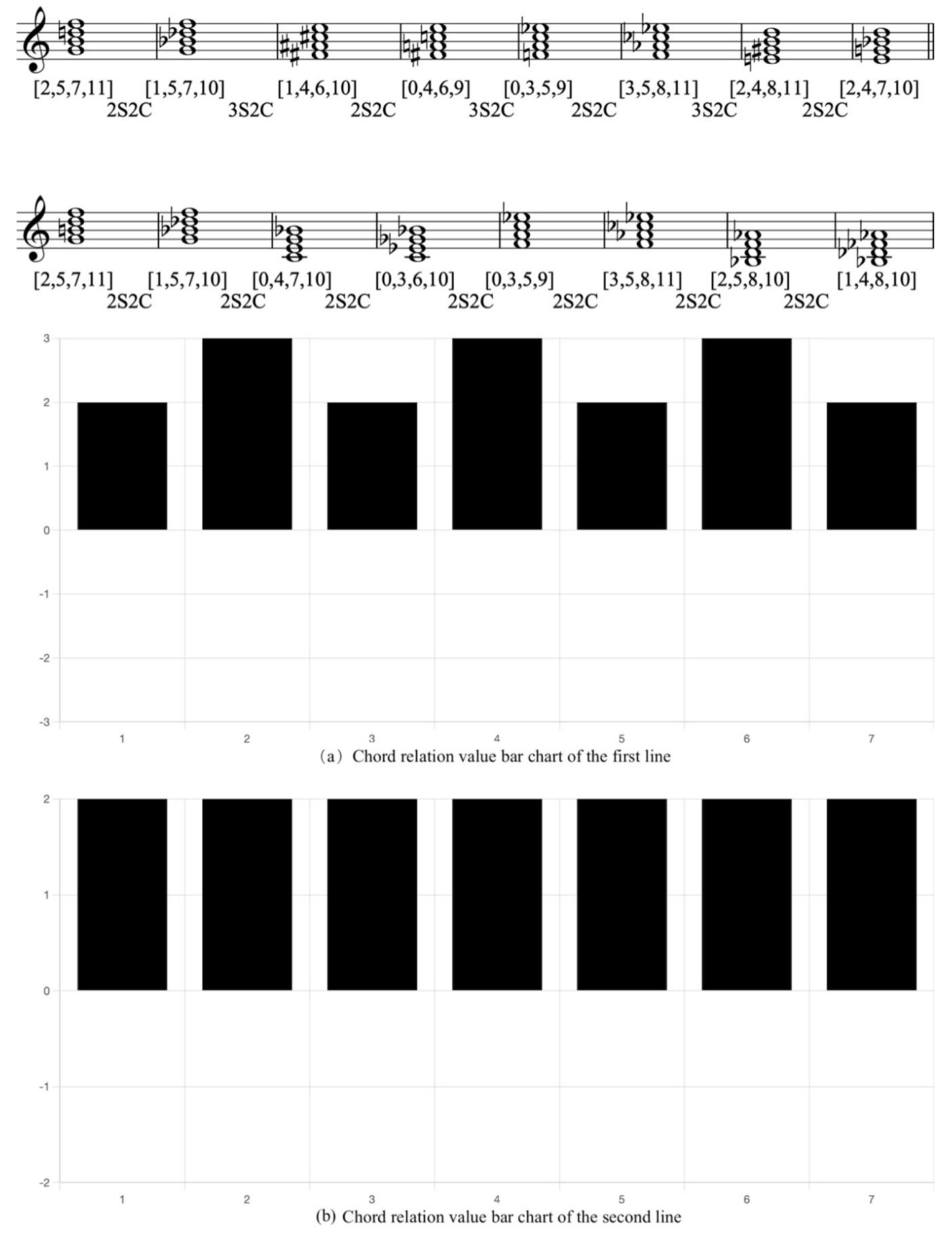

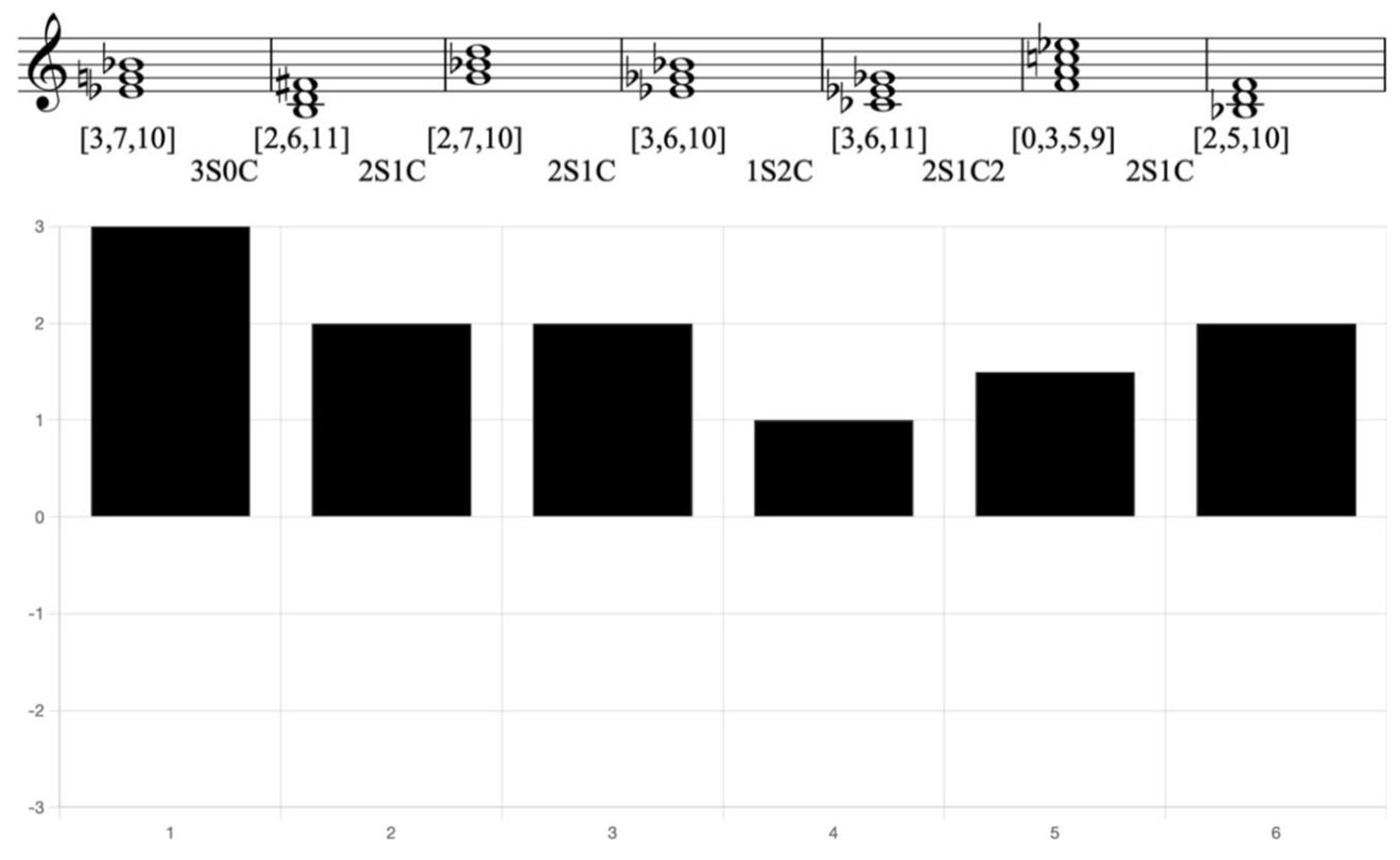

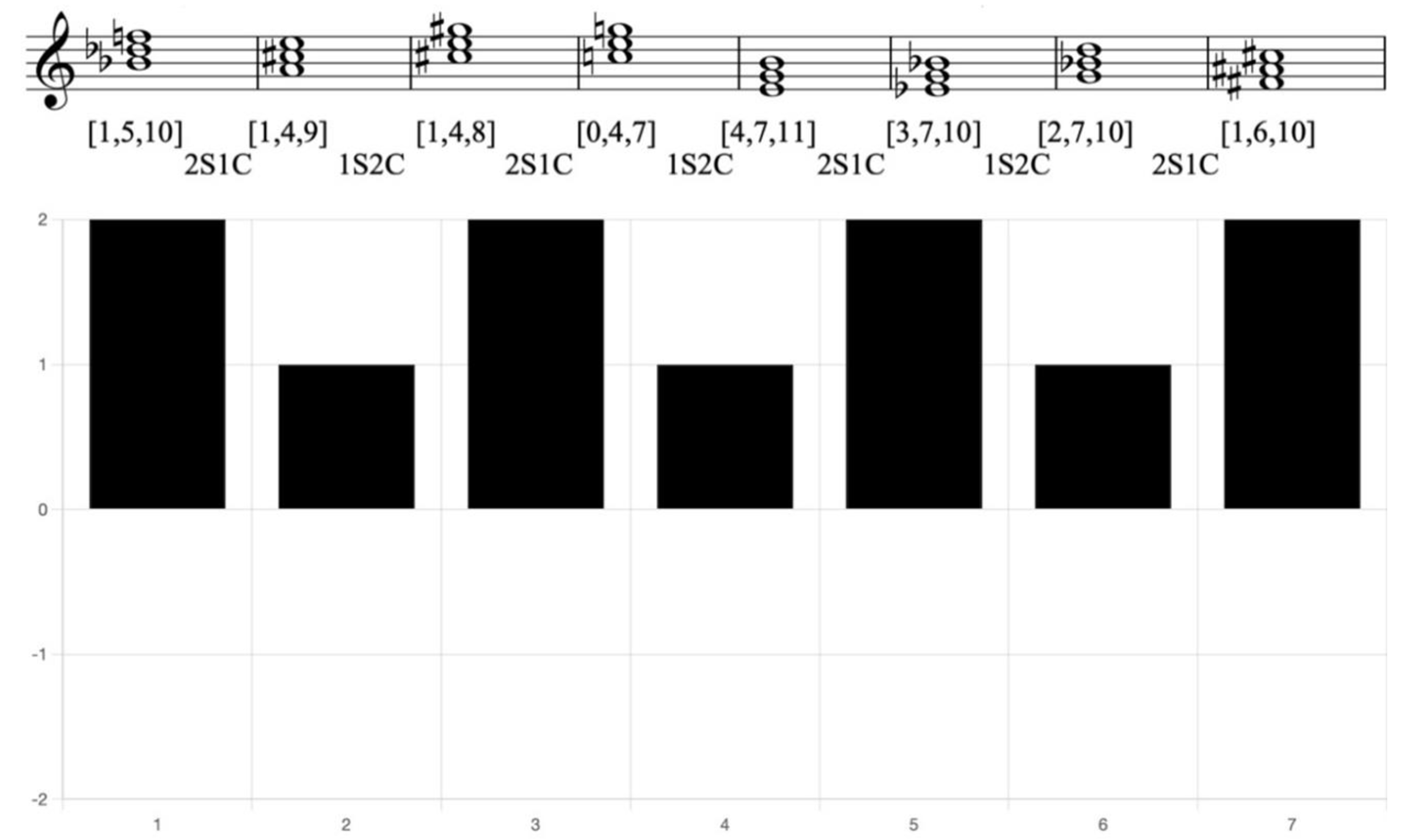

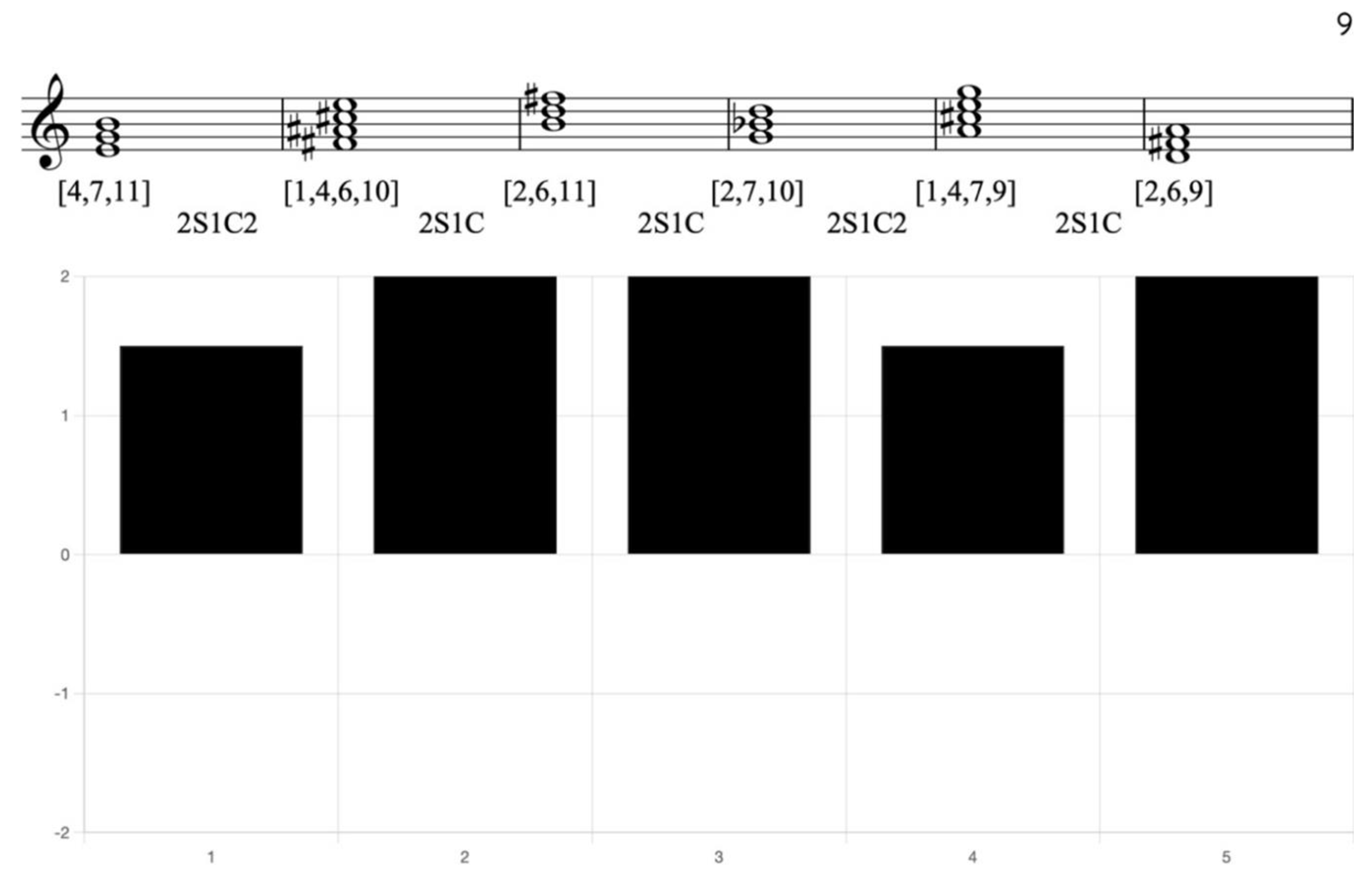

Example 3. Reduction of Schubert, Mass in E♭ major, Sanctus, mm. 1-7, with CRV bar chart

In this example, most of the CRVs contain at least 2S, indicating that the chord progression exhibits strong degree of tendency.

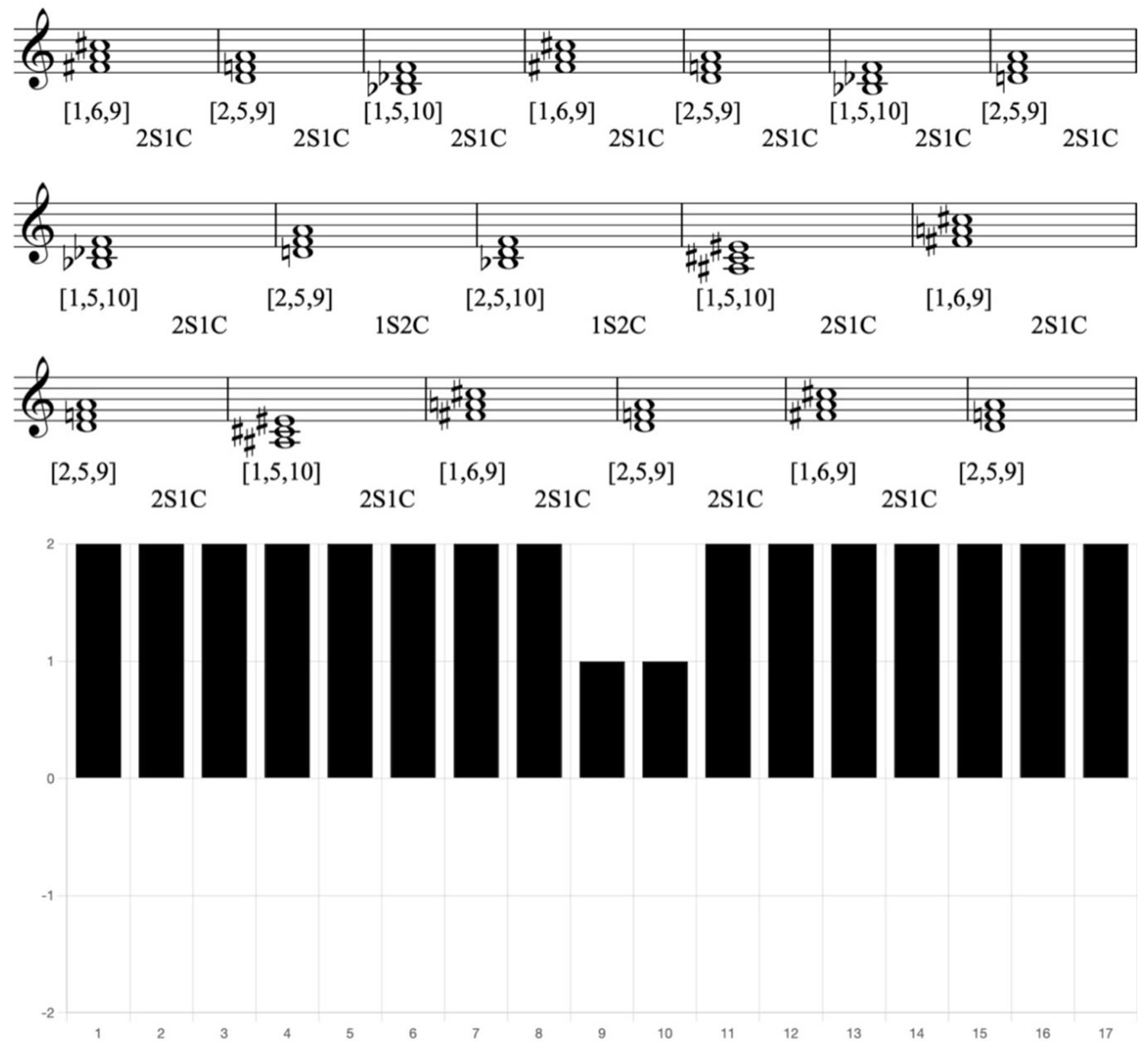

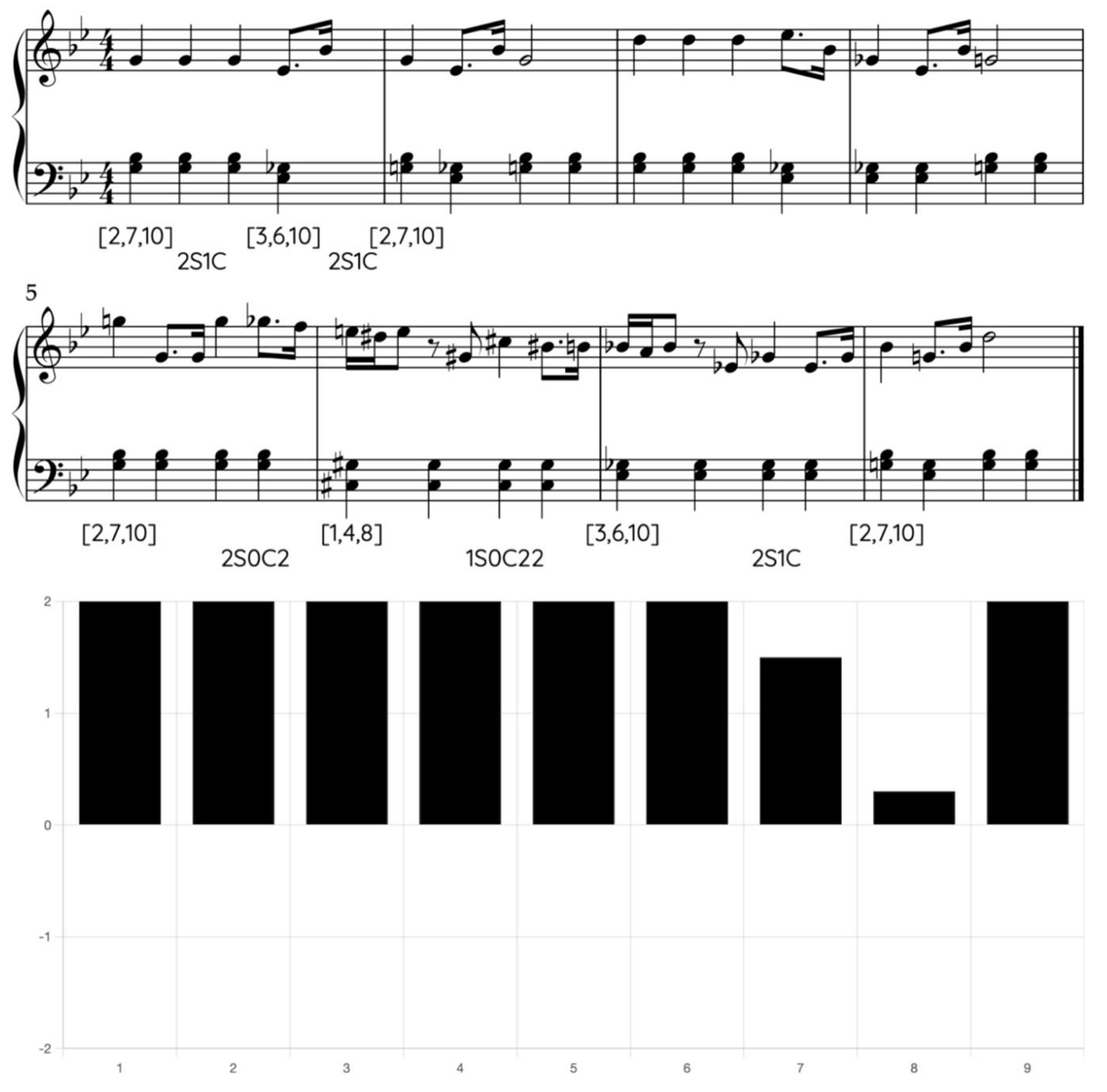

Example 4. Reduction of Rimsky-Korsakov, Symphony no.2 (Antar), 1 st mvt., mm. 1-19, with CRV bar chart

In this example, most of the chords maintain a high degree of tendency of 2S, facilitating smooth transitions. However, the presence of two 1Ss in the middle reduces the overall tendency of the progression. This variation in harmonic structure affects the intensity of connection among the chords, introducing contrasts that add depth and complexity to the piece.

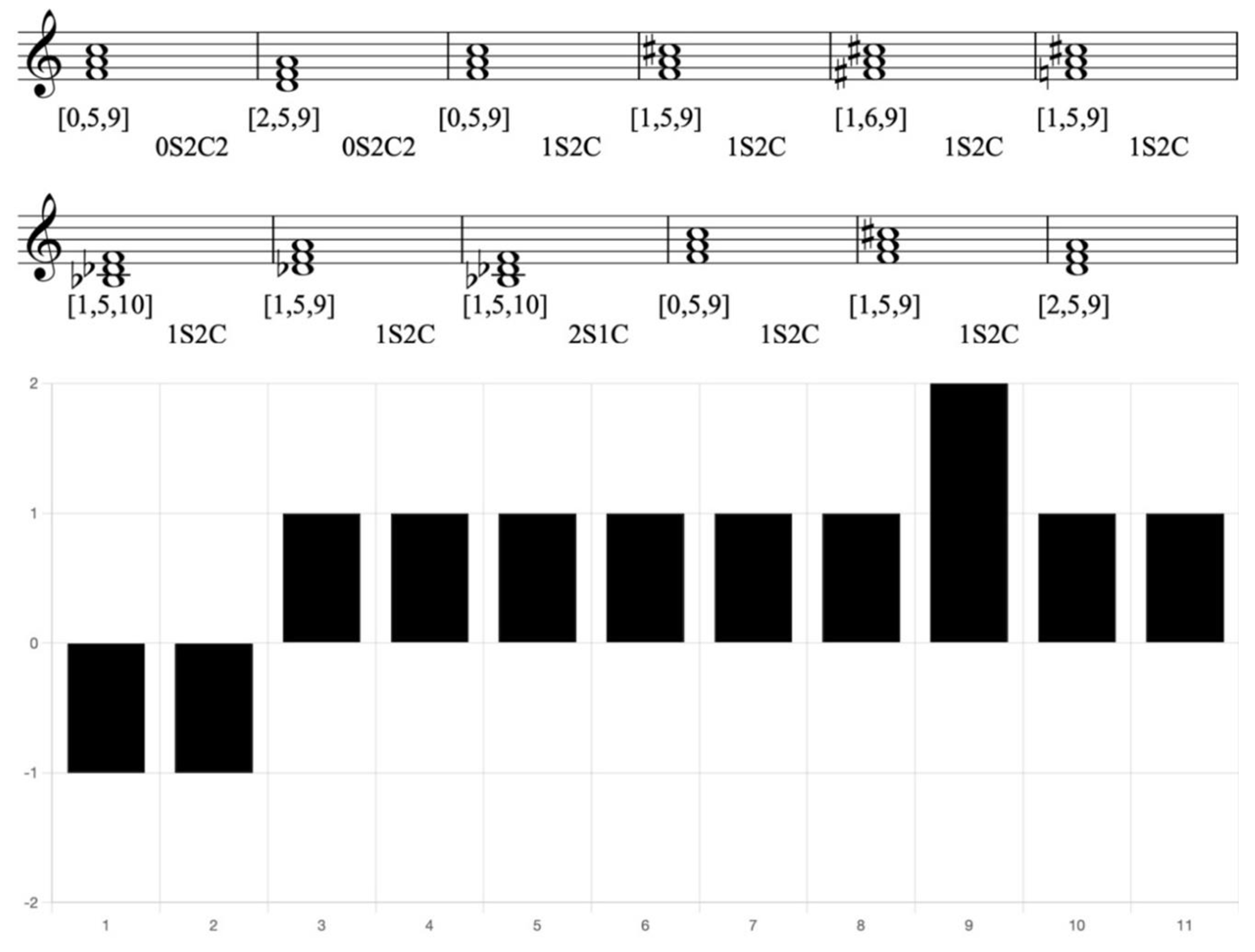

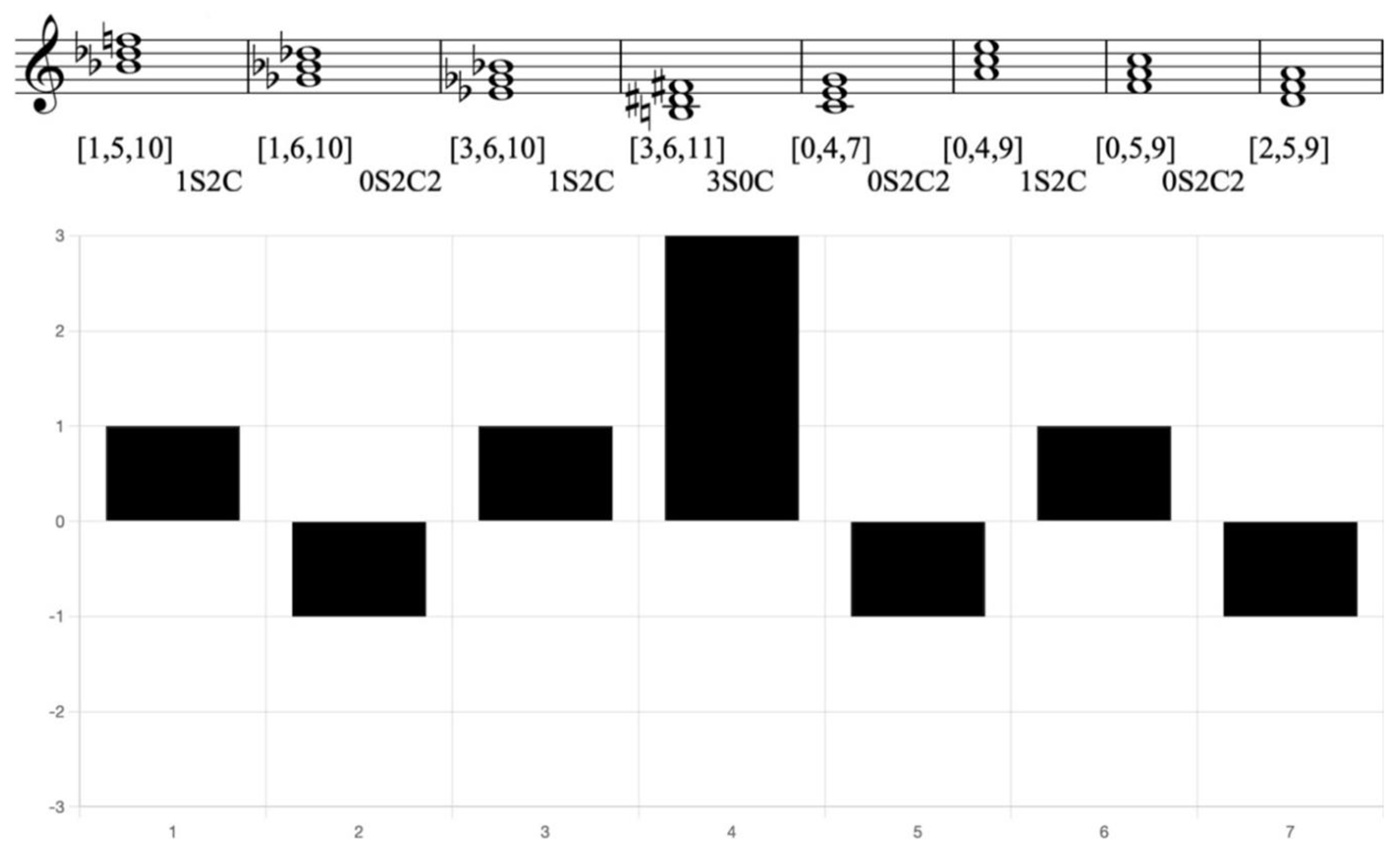

Example 5. Reduction of Faure, Requiem Mass, Introit, mm. 50-61, with CRV bar chart

In this example, most of the CRVs contain 2C, which maintains a relatively consistent low degree of tendency throughout the progression. This suggests that the harmonic movement is somewhat restrained, resulting in a stable and grounded musical foundation. Although some CRVs incorporate 1S while others incorporate a whole tone, these variations do not significantly disrupt the overall stability of the progression.

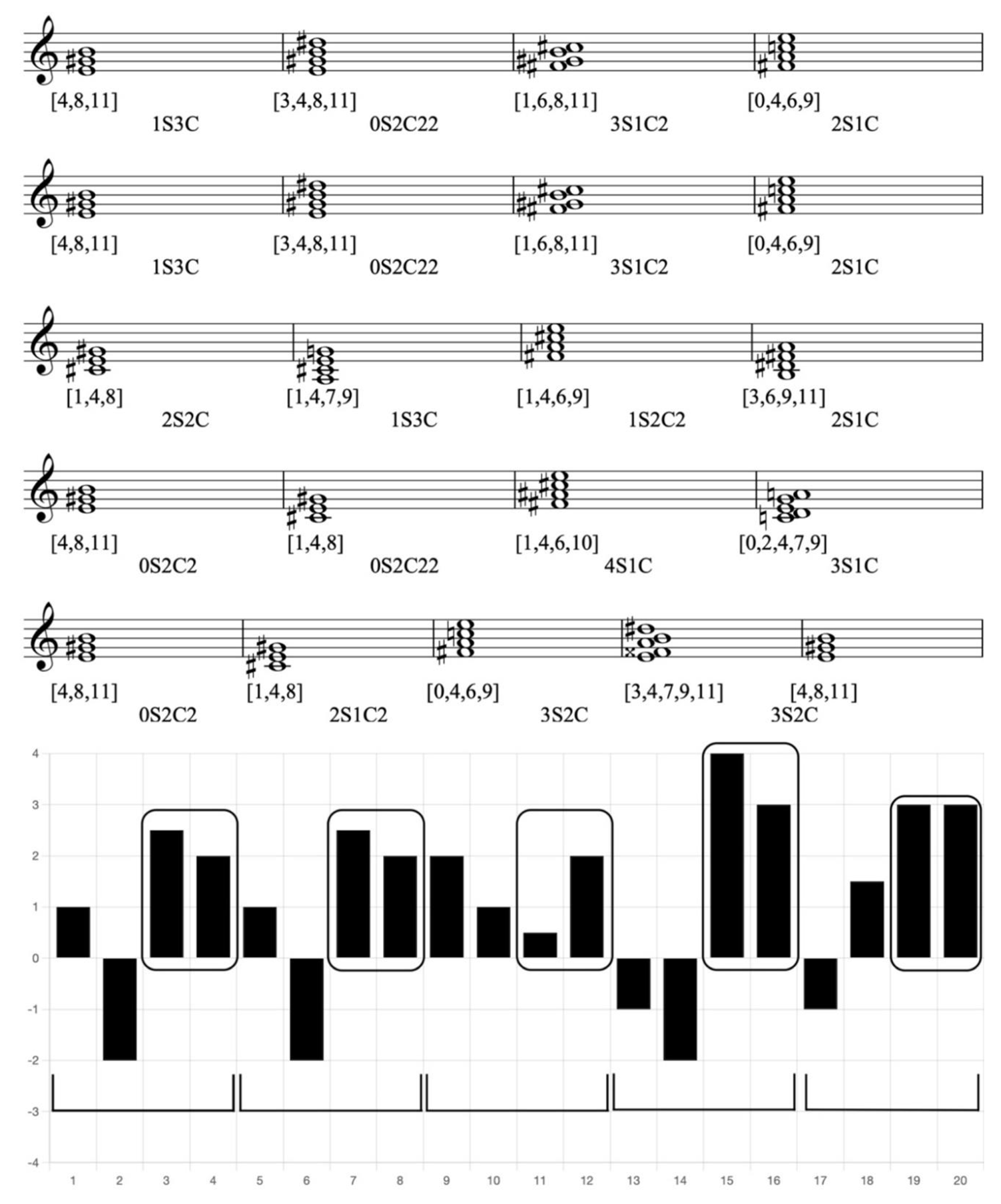

Example 6. Reduction of Brahms, Ein deutsches Requiem, 2nd mvt., mm. 261-271, with CRV bar chart

In this example, the first four chords form one phrase, while the last four chords establish another. Within each phrase, the chords maintain a high degree of similarity using 2C, contributing to coherence and stability in the inner structure. Between these two phrases, a 3S is employed, enhancing the tendency of the transition between them. This relation introduces a greater degree of harmonic movement, facilitating a more dynamic connection that provides a compelling turning effect.

Example 7. Reduction of Dylan, Lay, Lady, Lay, verse, with CRV bar chart

Two pairs of chords of 1S2C form a harmonic sequence. Between them, a 2S is used to provide a high degree of tendency in the connections.

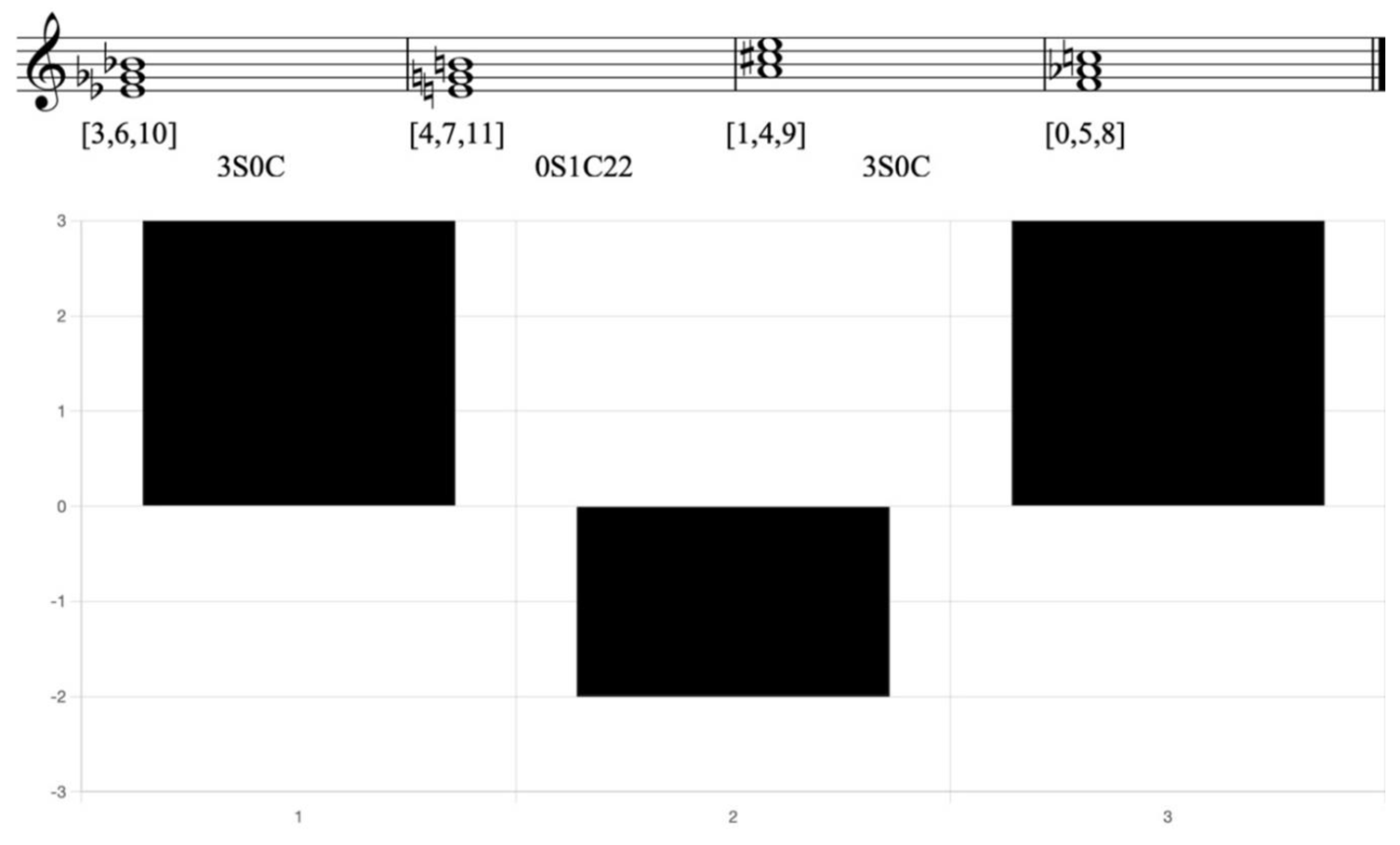

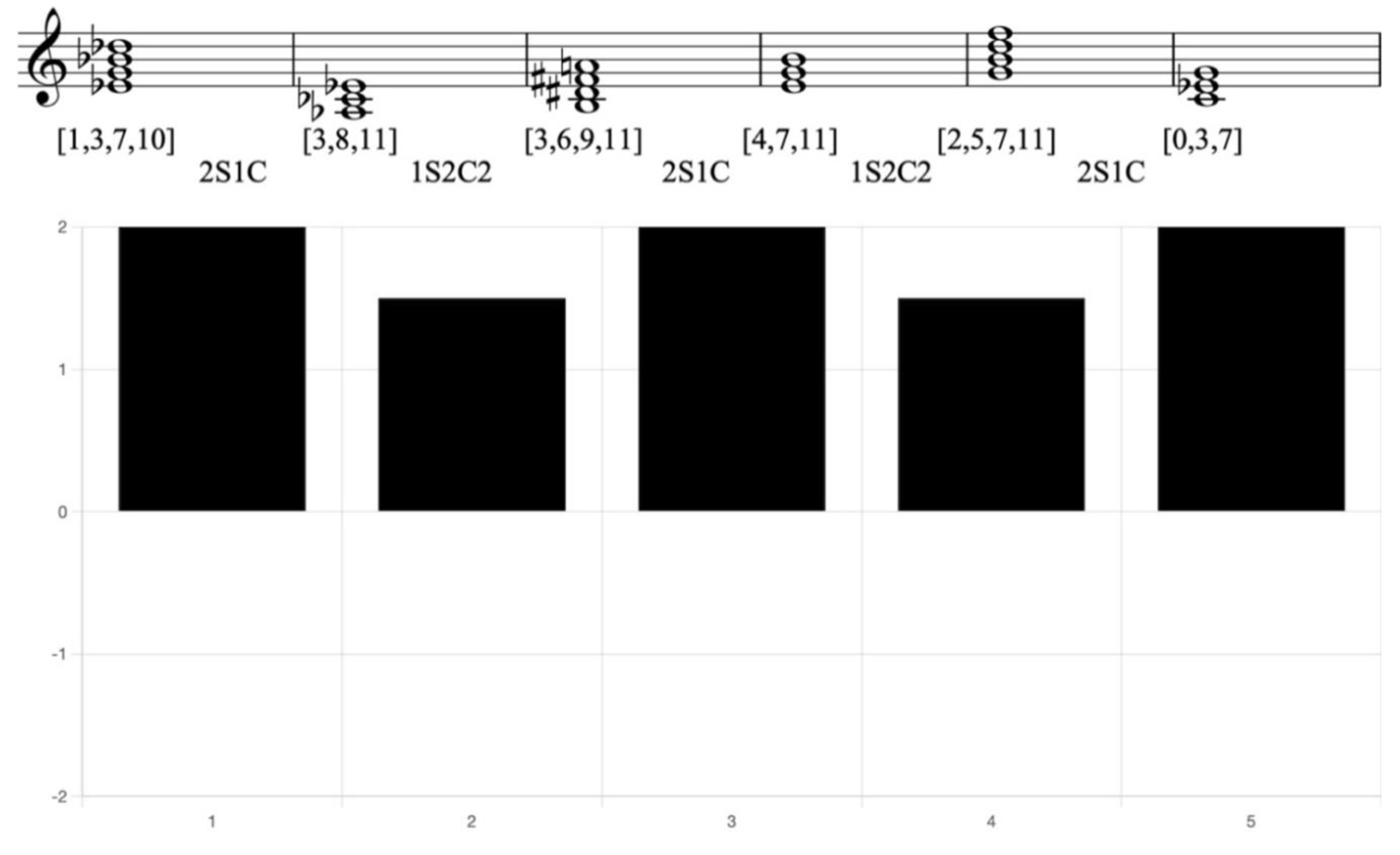

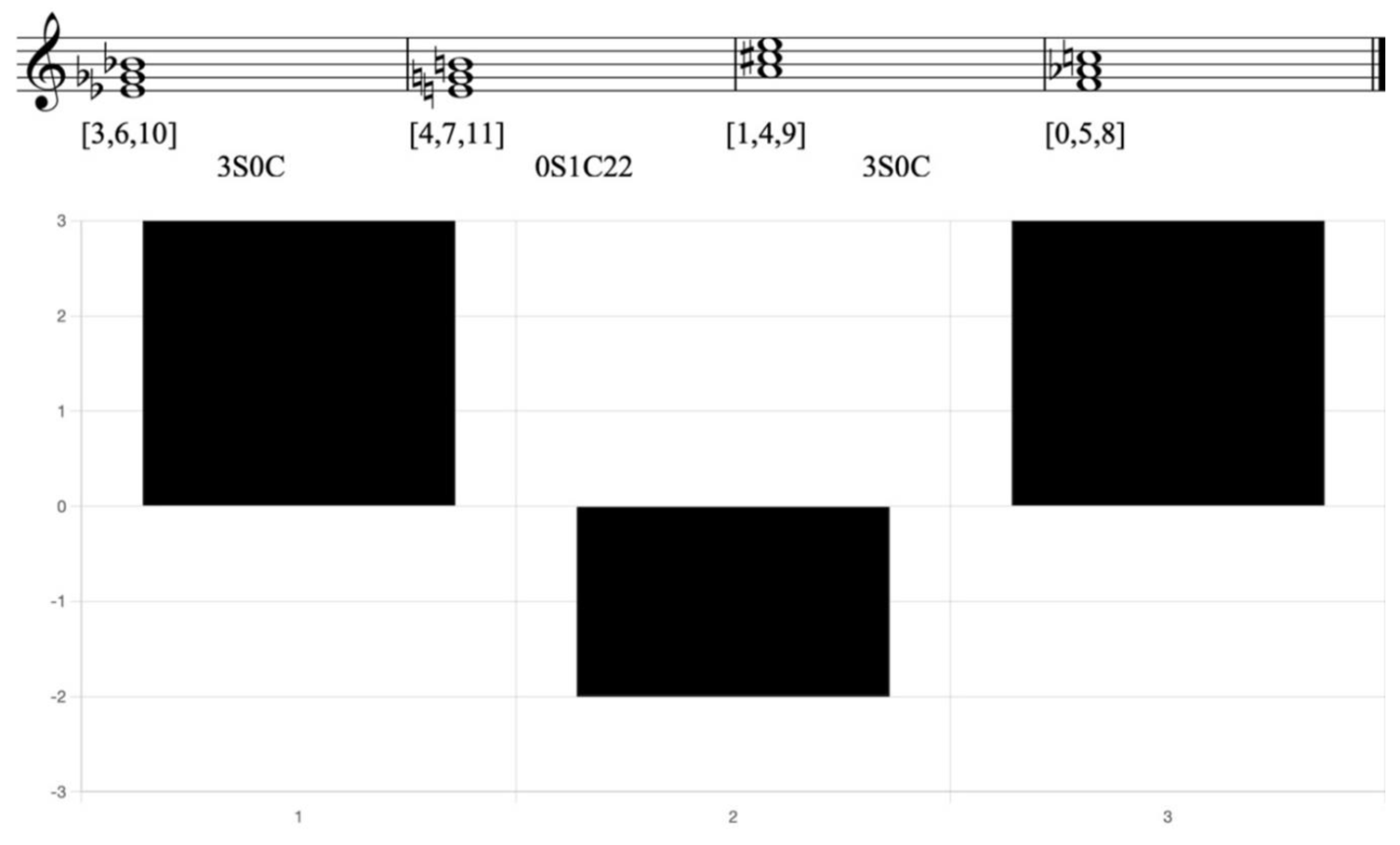

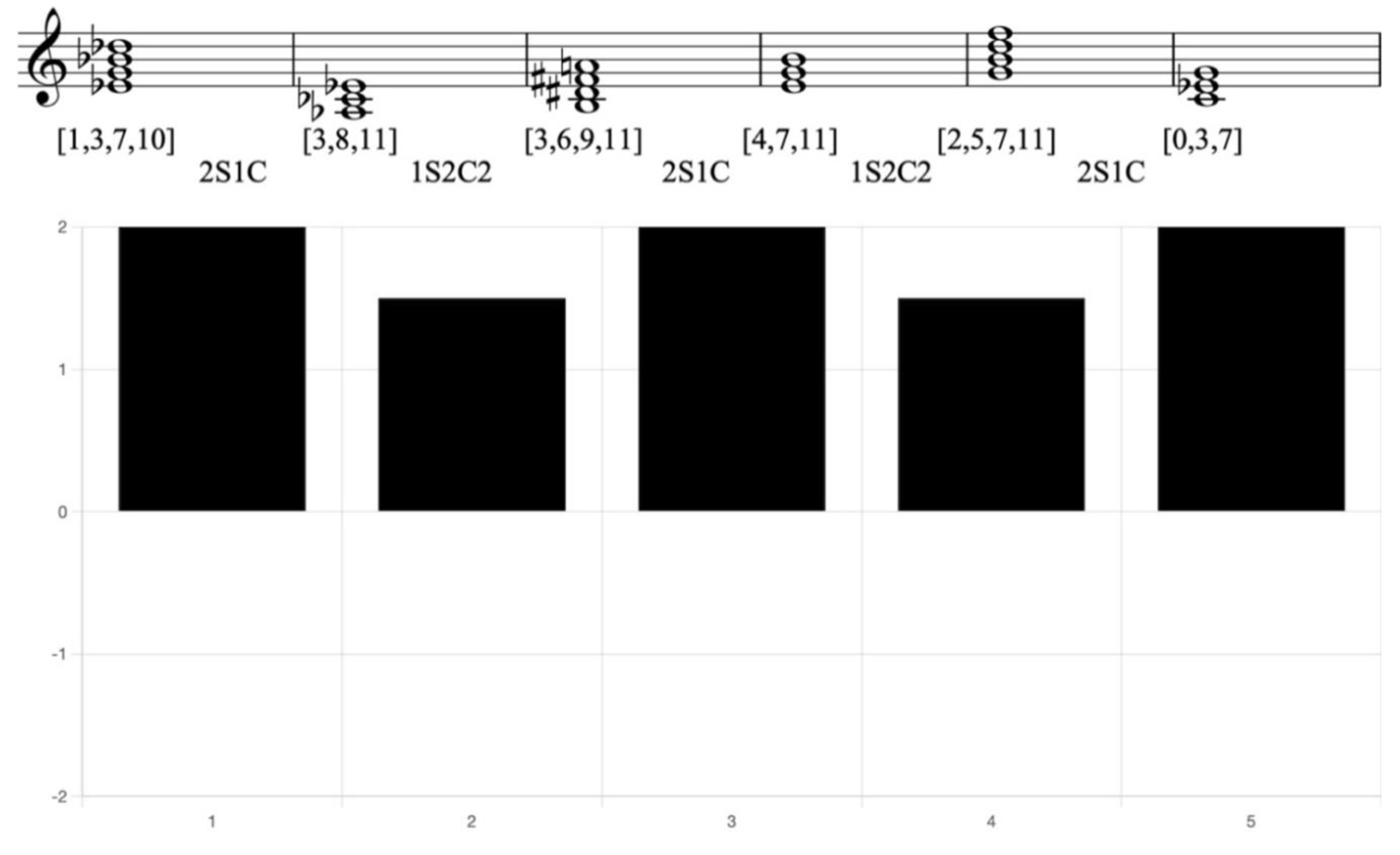

Example 8. Reduction of Debussy, Preludes, Canope, mm. 29–33, with CRV bar chart

In this example, a harmonic sequence is constructed based on the CRV. The CRV between the first pair of chords is 3S0C, while the last pair of chords share the same CRV. Although the first two chords are both minor triads, the last two chords consist of a major triad and a minor triad. The identical CRVs indicate that these chords share a similar degree of tendency, providing a sense of sequence even within the context of non-sequential harmonic movement.

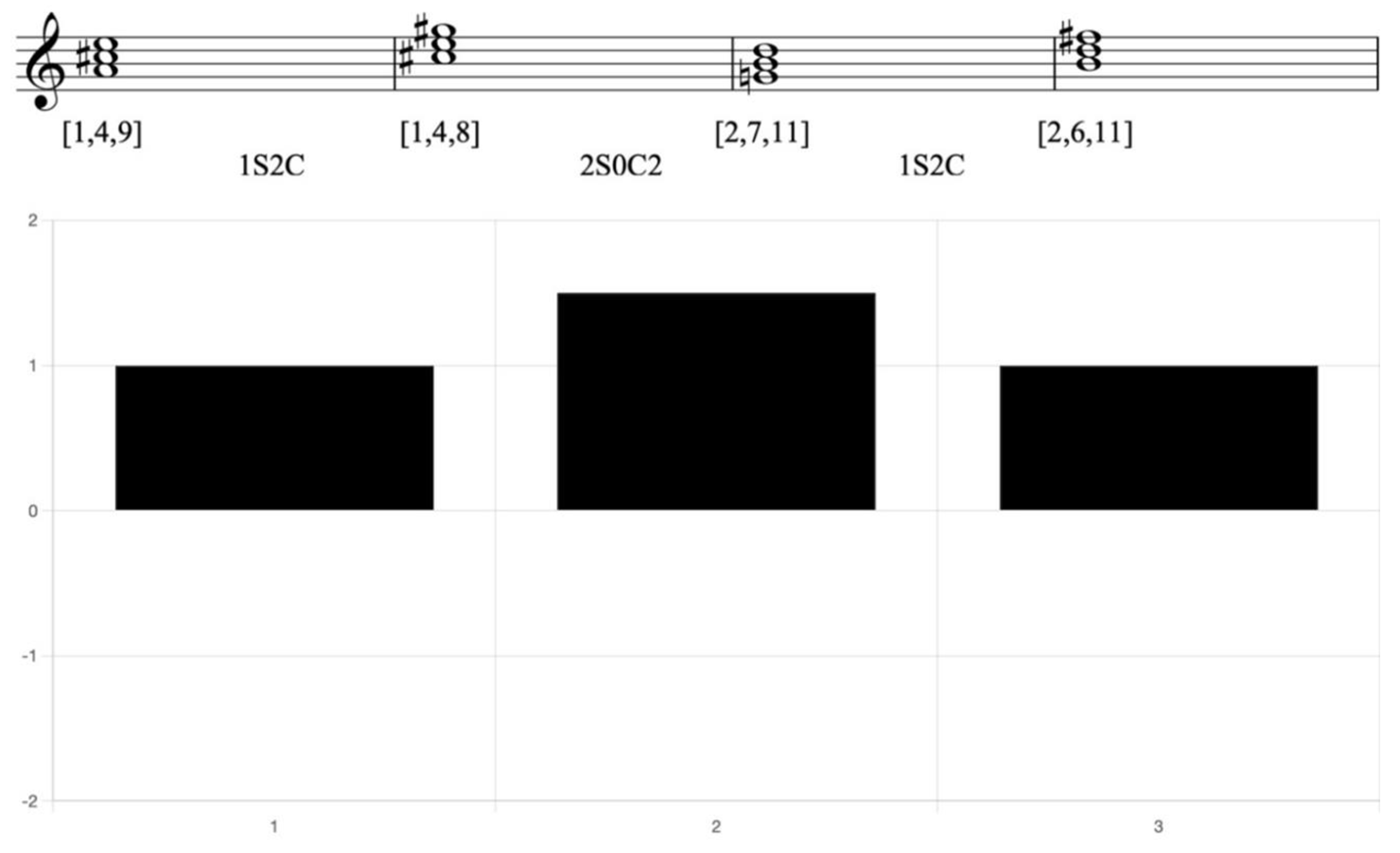

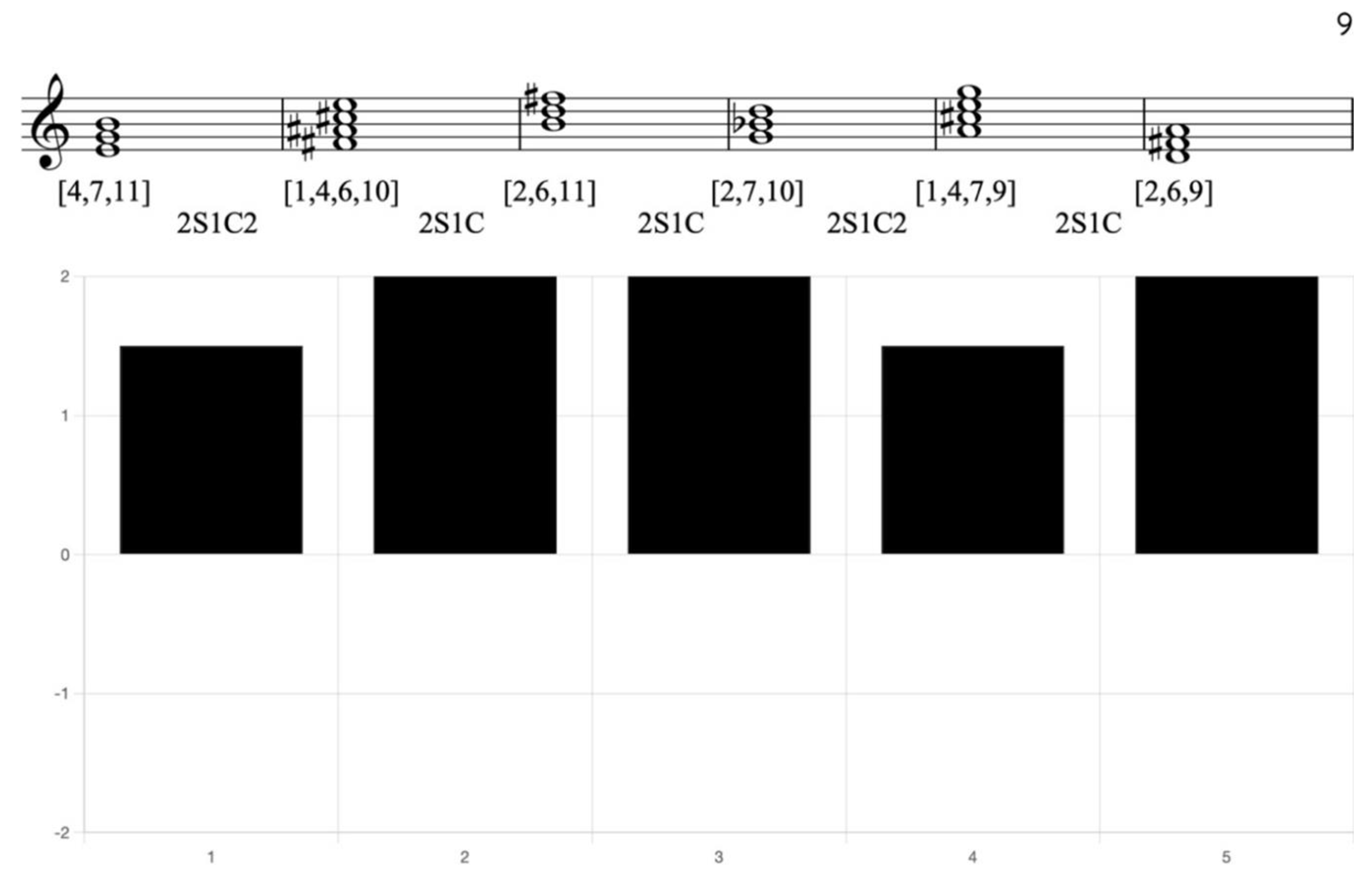

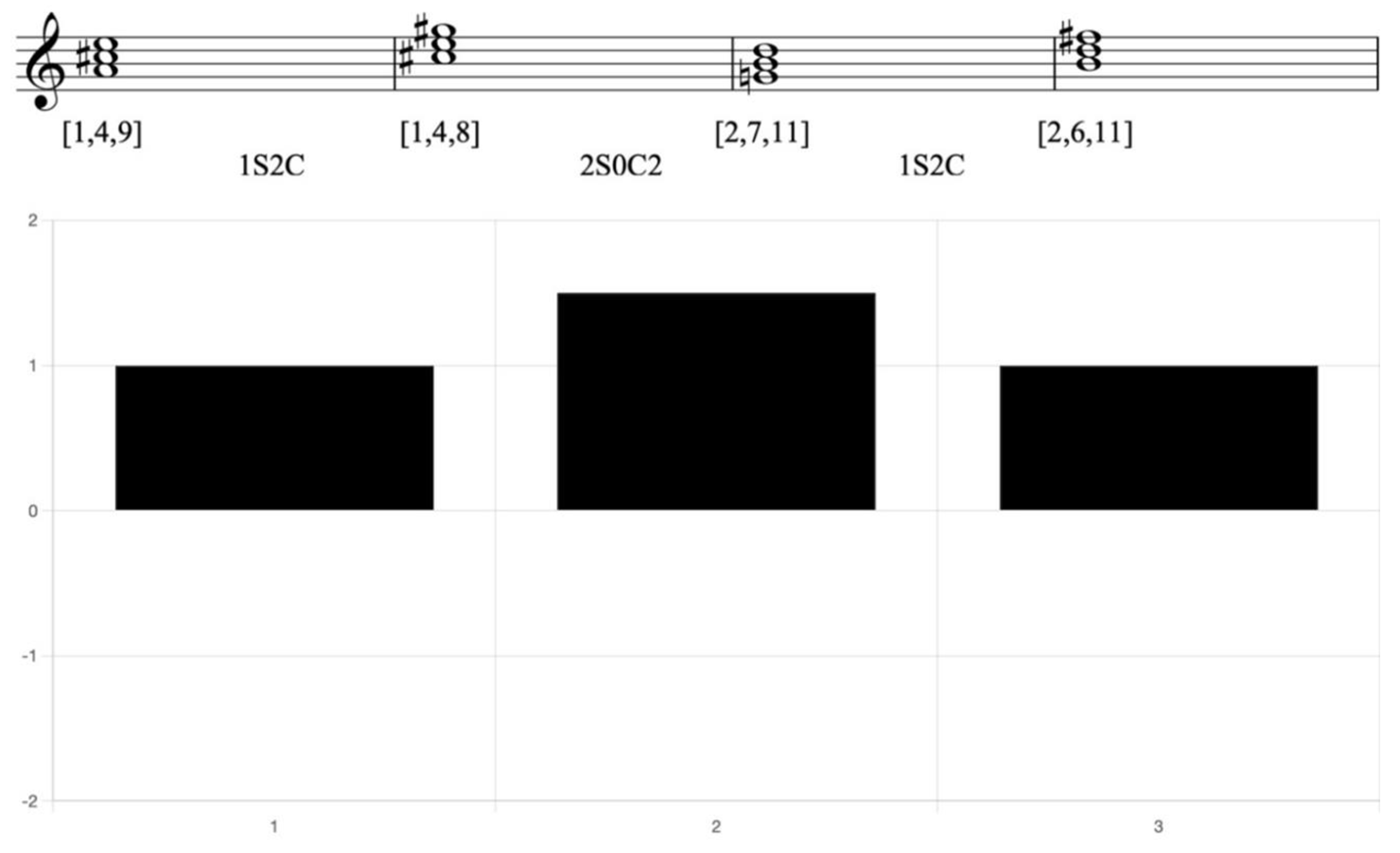

Example 9. Reduction of Liszt, Grande fantasie symphonique uber Theme aus Berlioz ‘Lelio’, mm 195-199, with CRV bar chart

By examining the CRVs in this example, it becomes evident that harmonic sequences are employed. The pairs of chords with a CRV of 2S1C form sequences. Furthermore, the CRVs between sequences are consistently 1S2C, which enhances the cohesive connection of these sequences.

Example 10. Williams, The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme), mm. 5-12, with CRV bar chart

In this famous movie theme, the use of 2S effectively creates a tense atmosphere. Within the context of G minor, there are no diatonic triads that can establish a 2S relation with the G minor triad. To introduce more unexpected harmonic effects, the E♭ minor triad is selected, resulting in a CRV of 2S1C with the G minor triad. This choice enhances the tension and unpredictability of the music.

In the fifth measure, the CRV between the G minor triad and the C♯ minor triad is 2S0C2, which also introduces sufficient tension. Furthermore, the CRV between the C♯ minor triad and the E♭ minor triad is 1S0C22, helping to reduce the tension and form a contrast of tendency in the harmonic progression.

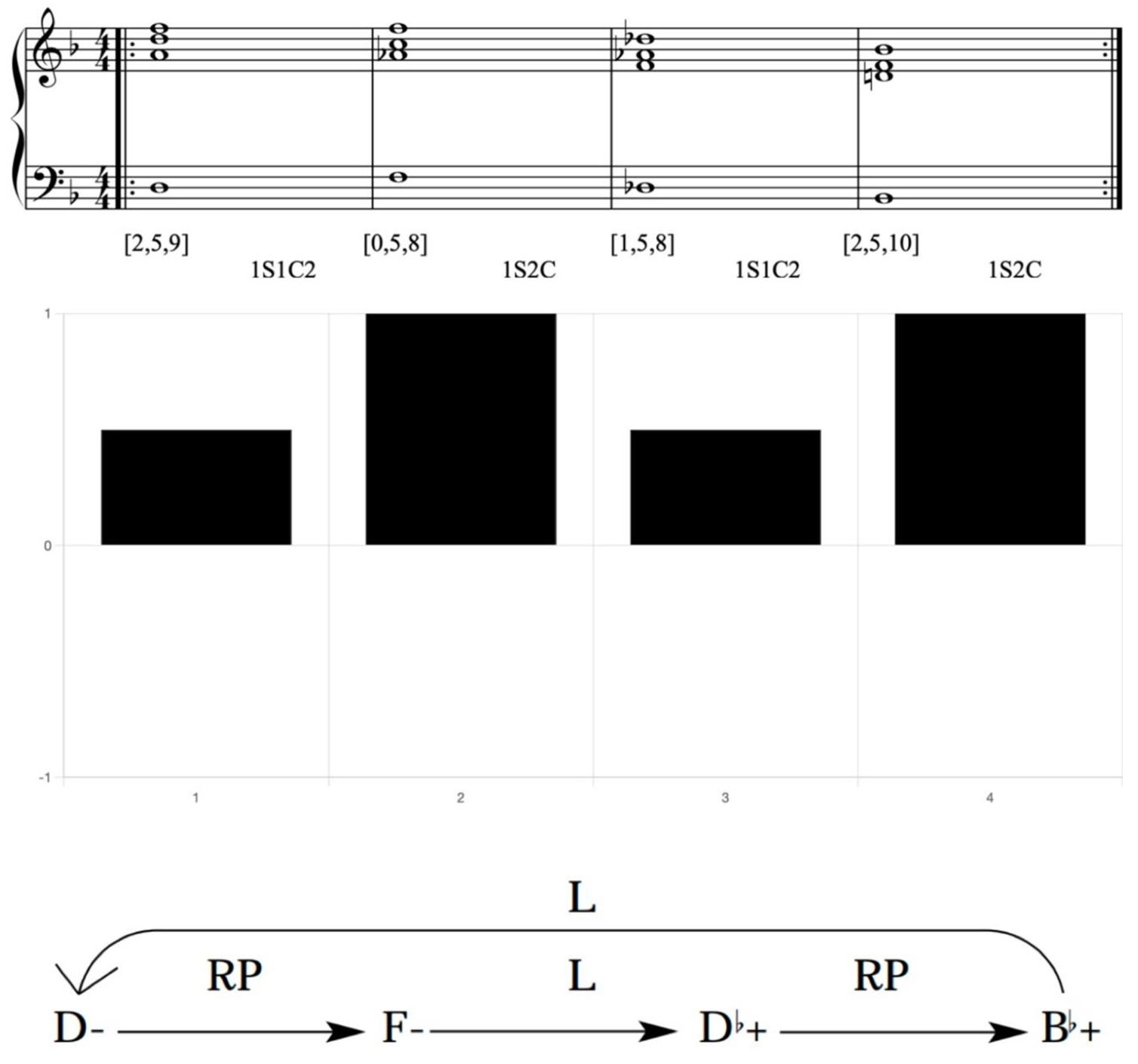

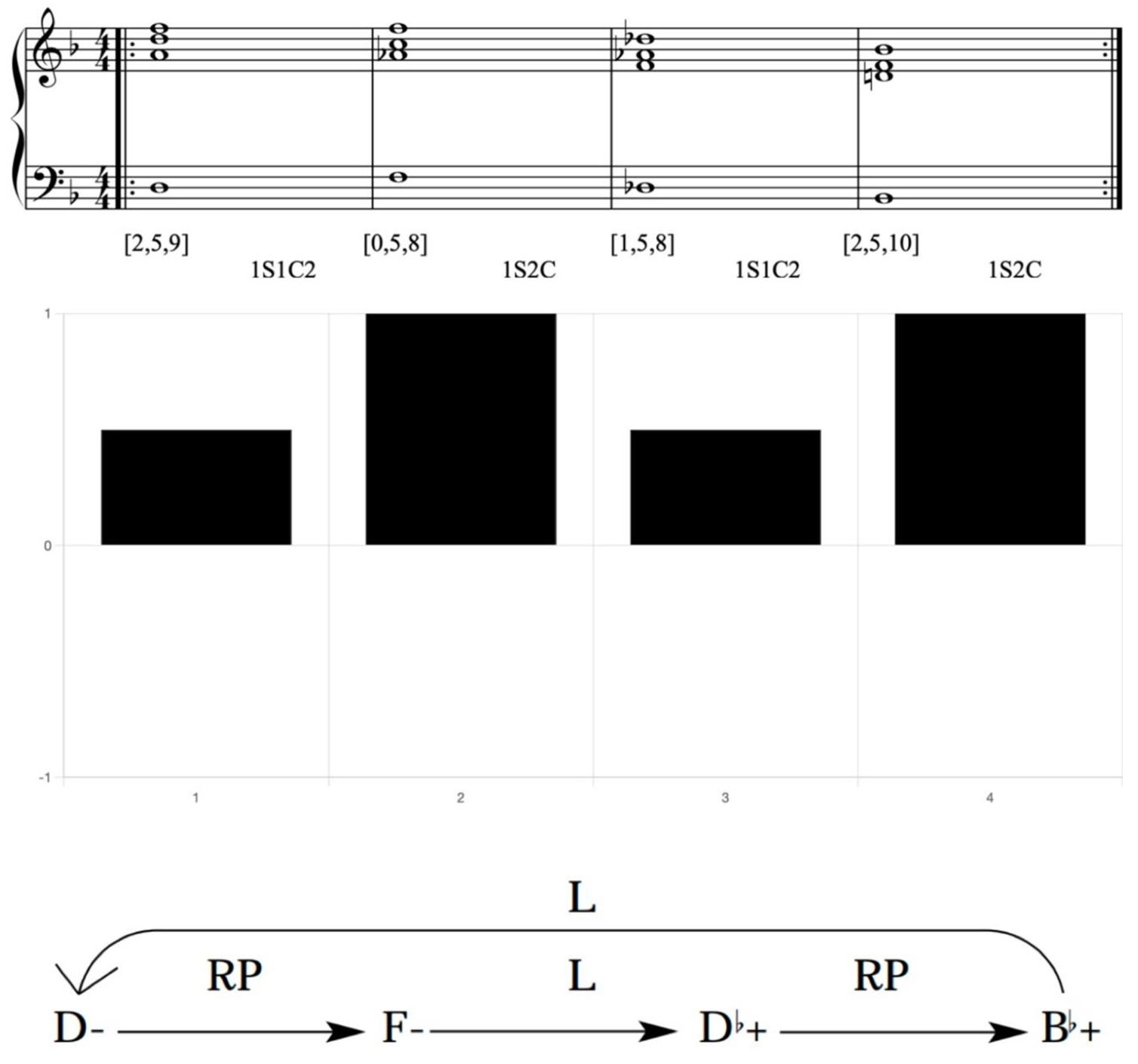

Example 11. Reduction of Depeche Mode, Shake the Disease, chorus, with CRV bar chart and Neo-Riemannian analysis

Capuzzo (2004) analyzed this excerpt using the Neo-Riemannian method. Through CRV analysis, we find that the results exhibit a certain consistency with the Neo-Riemannian method. The Neo-Riemannian analysis reveals an alternating pattern of RP and L relationships, while CRV reveals an alternating pattern of 1S1C2 and 1S2C. One advantage of the CRV analysis is its ability to demonstrate the degree of tendency of chords, rather than merely highlighting abstract relational patterns.

Example 12. Prokofiev, Flute Sonata, Op. 94, II Scherzo, mm. 73-83

Heetderks (2013) did a detailed analysis of Prokofiev’s flute sonata from the perspective of semitonal succession-classes. From the perspective of CRV, 3S0C in the first excerpt corresponds to the semitonal succession Heetderks proposed, while 2S1C in the second excerpt corresponds to the partial semitonal succession. Analyzing through CRV further provides a description of the distinct tendency of these two types of semitonal succession, while also revealing Prokofiev’s thought of using chords.

Between Triad Chords and Seventh Chords

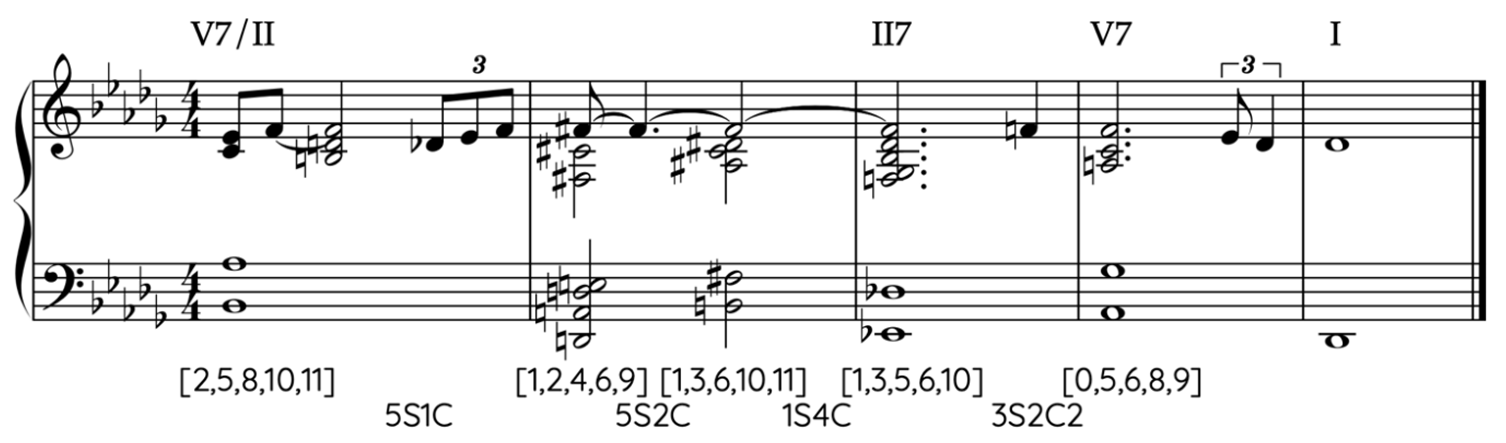

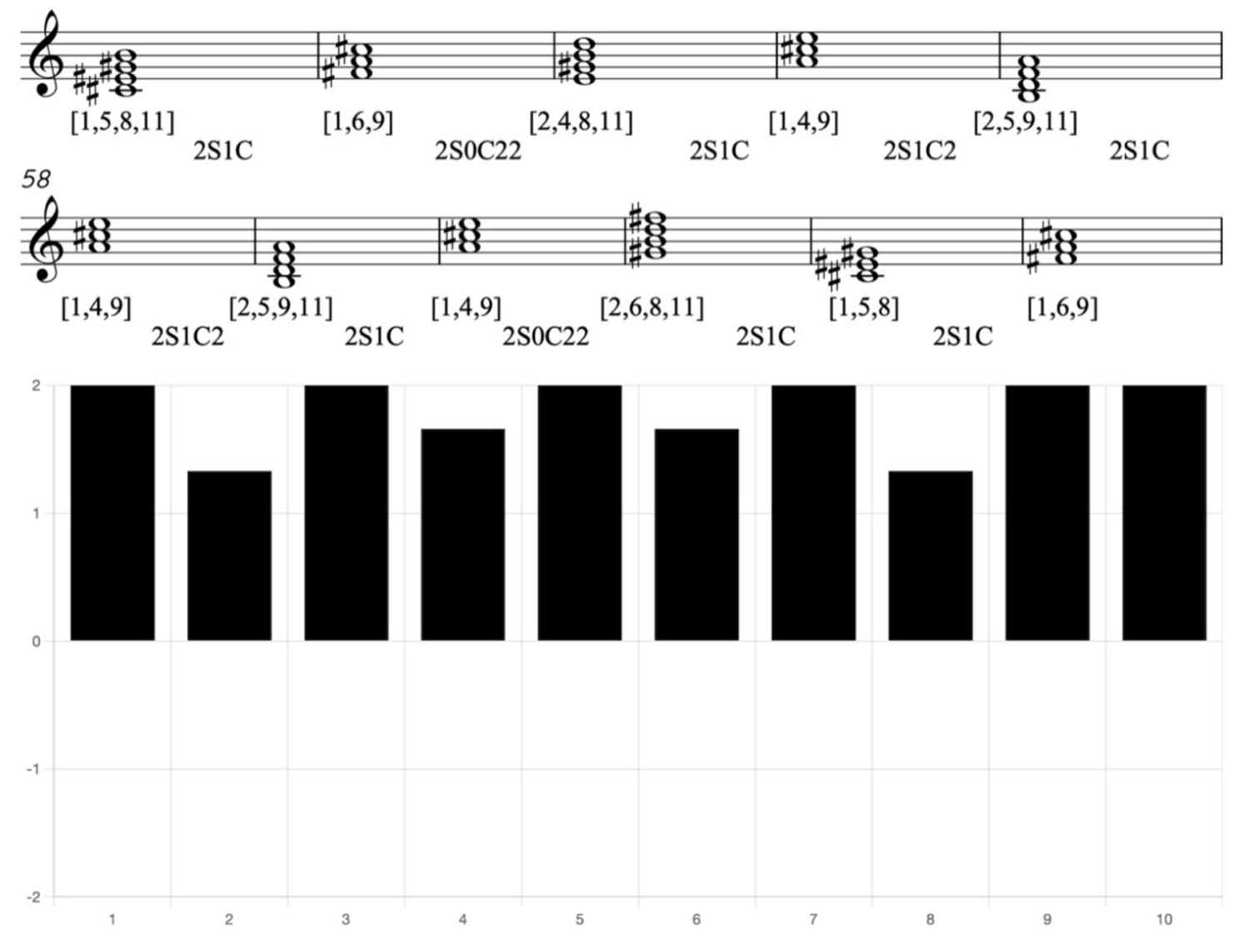

Example 13. Reduction of Schubert, Symphony No. 9, 1st mvt., mm. 304-315, with CRV bar chart

In this example, 2S1C appears every other chord, suggests the possibility of harmonic sequences. By examining the structure of the chords, it becomes evident that they do indeed form these sequences. Furthermore, the CRVs between the sequences are all 1S2C2. This consistency in the CRVs demonstrates that the sequences are intentionally designed to maintain a consistent sense of distance throughout the harmonic progression.

Example 14. Reduction of Schumann, In wunderschonen Monat Mai, mm. 8-12, with CRV bar chart

In this example, the first three chords are in sequence with the last three chords. Notably, the first three chords are in a minor key, while the last three chords transition to a major key. Despite this tonal contrast, the identical CRVs within these sequences ensure that they produce a similar harmonic effect. Furthermore, the entire progression maintains a high degree of tendency, characterized by a consistent 2S, even between these two sequences.

Example 15. Reduction of Chopin, Mazurka, Op. 6 no. 1, mm. 8-16, with CRV bar chart

In this example, 2S1C not only represents the relation between the V7 chord and the I chord but also reflects the relation between the half-diminished seventh chord and the subsequent major triad. The identical CRVs of these two pairs of chords indicate that the progression from the half-diminished seventh chords to the subsequent major triads has a similar harmonic tendency as the progression from the V7 chord to the I chord.

It’s noteworthy that this observation aligns with the principles of negative harmony theory (Levy,1985). For example, according to negative harmony theory, the fifth chord in this example, the B half-diminished seventh chord, can be mapped to an E dominant seventh chord, which also has a CRV of 2S1C with the A major triad. The equivalence of mapping and the CRVs suggests that Chopin selected these chords based on his auditory intuition, even though negative harmony theory had not yet been established during his time. Consequently, he spontaneously achieved this distinctive harmonic effect.

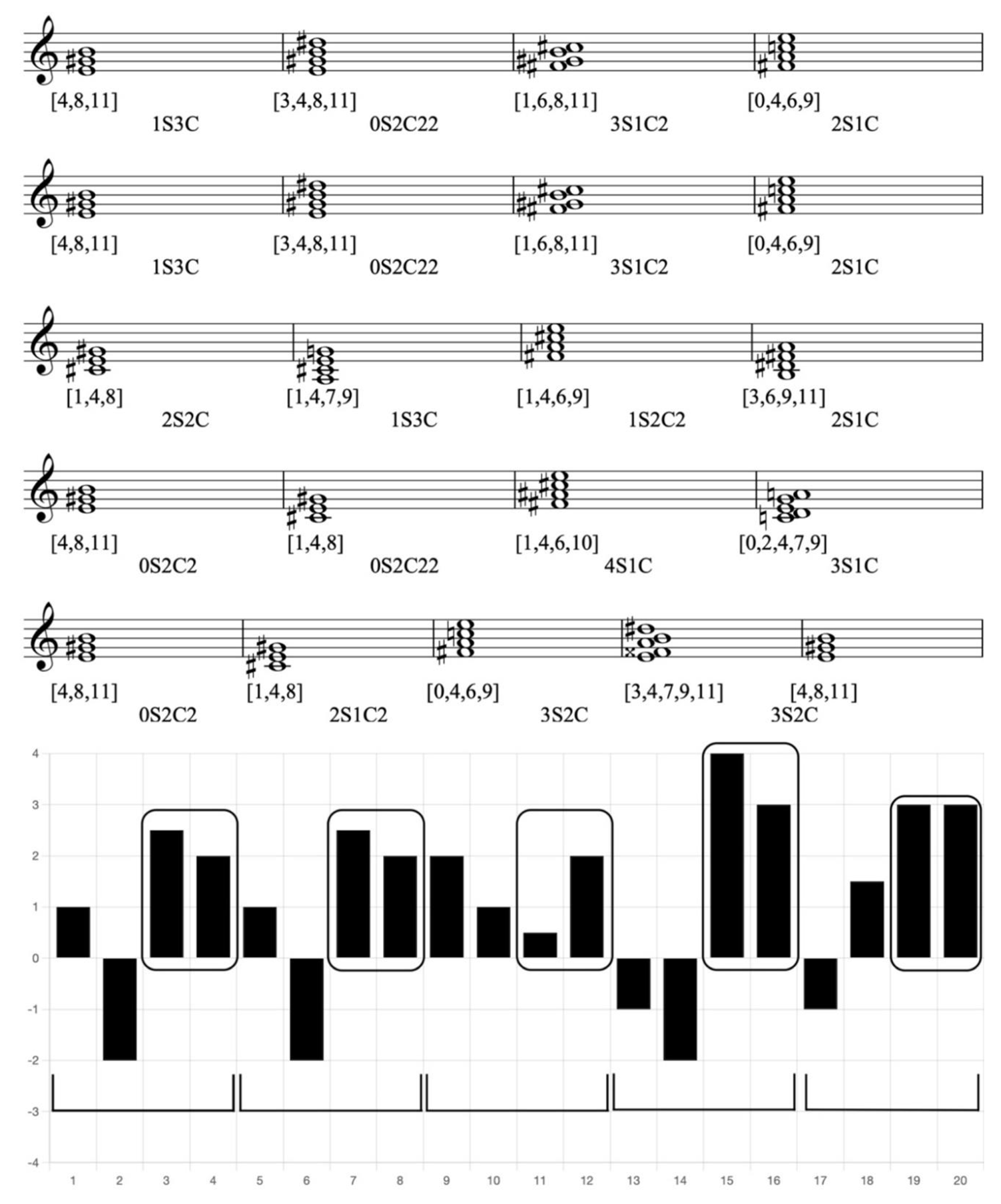

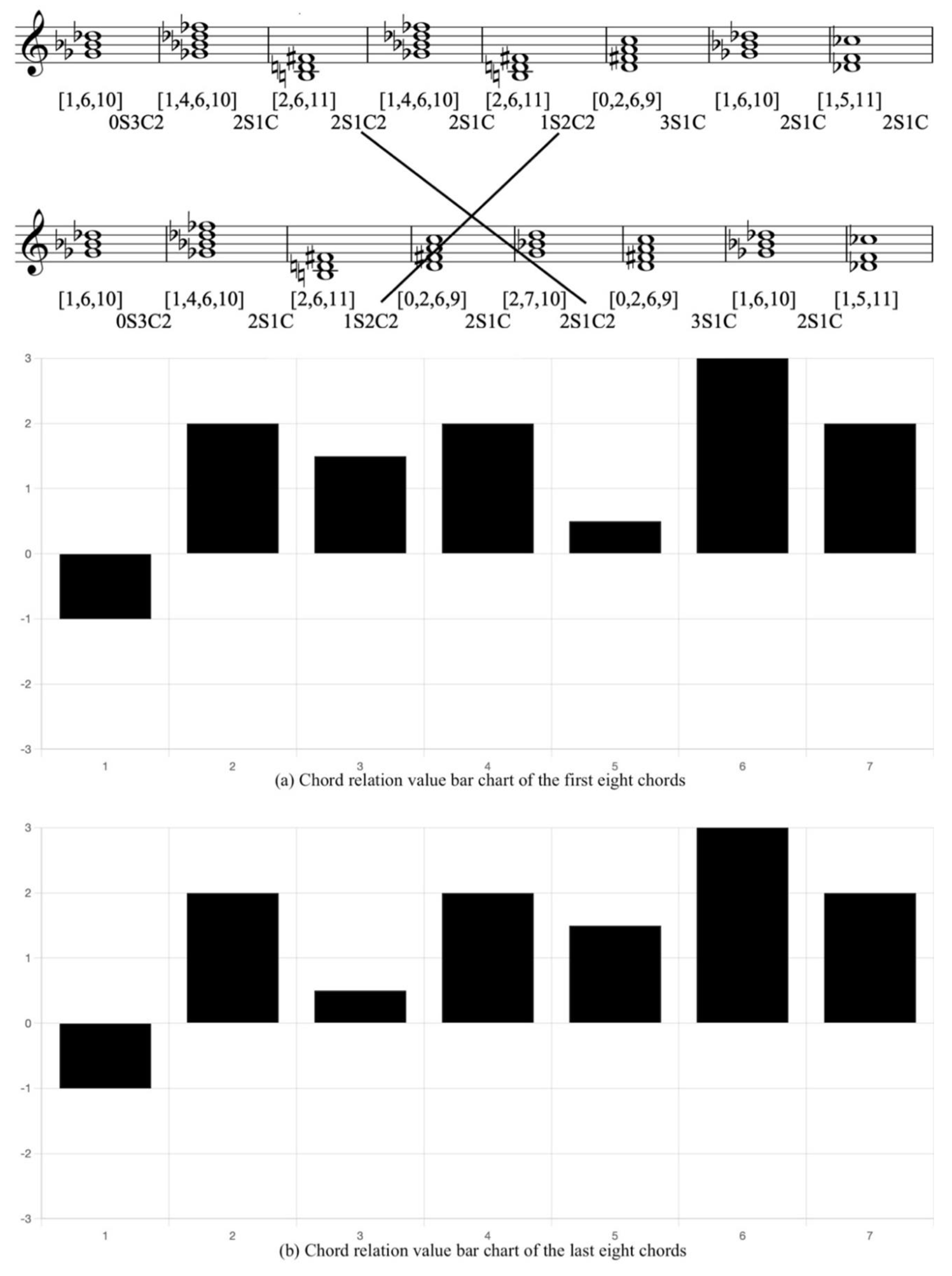

Example 16. Reduction of Schubert, Impromplus, Op. 90, mm. 75-82, with CRV bar chart

In this example, the progressions of the first and last eight chords exhibit notable similarities, while the middle progressions demonstrate variation. By examining the CRVs, we can observe that 2S1C2 and 1S2C2 in the first eight chords switch positions in the last eight chords. Specifically, 2S1C2 moves to the back, while 1S2C2 moves to the front. This exchange alters the details of tendency in the part of the last eight measures, resulting in a contrast between the first phrase, which trends from high to low tendency, and the second phrase, which trends from low to high tendency.

Example 17. Reduction of Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 18, 2nd movement, mm. 147-166, with CRV bar chart

In this example, the high degree of tendency exhibited every four measures (in each phrase) primarily manifests between the chords of the third and fourth measures, introducing significant changes in color to the piece. Additionally, there is a similarity of at least 2C within the chords from the first measure to the third measure in each phrase. These two phenomena indicate a high degree of tendency and notable similarity in the CRVs, which aligns with auditory perception. Such a design suggests Rachmaninoff’s intentional method to crafting harmonic progressions. Another key characteristic of this piece is that the CRVs during the transitions between each phrase consistently exhibit at least 2S. While this maintains a similar degree of tendency throughout the progression, it is important to note that the chords themselves differ significantly.

Additionally, the piece features a non-resolved dominant seventh chord, specifically the A dominant seventh chord. By examining the CRV between this dominant seventh chord and the subsequent F♯ minor-seventh chord reveals that the reason for this dominant seventh chord remaining unresolved is its transition to another chord by 3C. Furthermore, there are four chords that are more complex than triads and seventh chords. This suggests that CRVs can be effectively utilized to analyze not only triadic and seventh chords but also a variety of more complex chord structures.

Between Seventh Chords

Example 18. Wagner, Parsifal, Act I, mm. 1369-1371, with CRV bar chart

In this example, the chords are primarily seventh chords, with each dominant seventh chord descending by a fifth. However, they do not resolve according to traditional harmonic relations, as they are followed by a half-diminished seventh chord. This demonstrates Wagner’s desire to achieve the utmost degree of tendency, as the CRV between these two chords contain 5S.

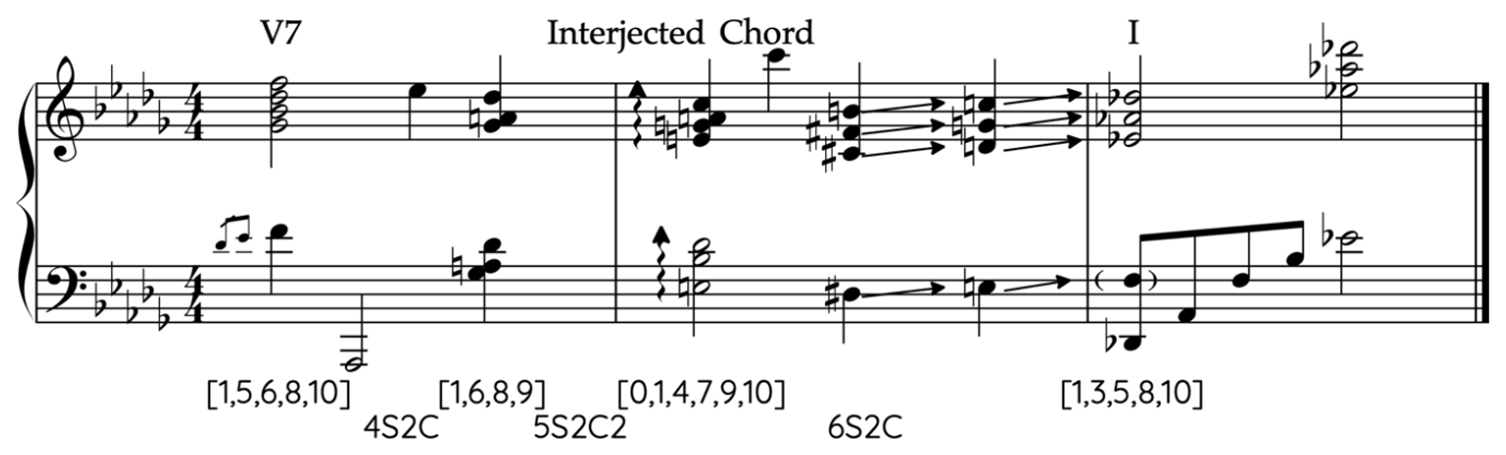

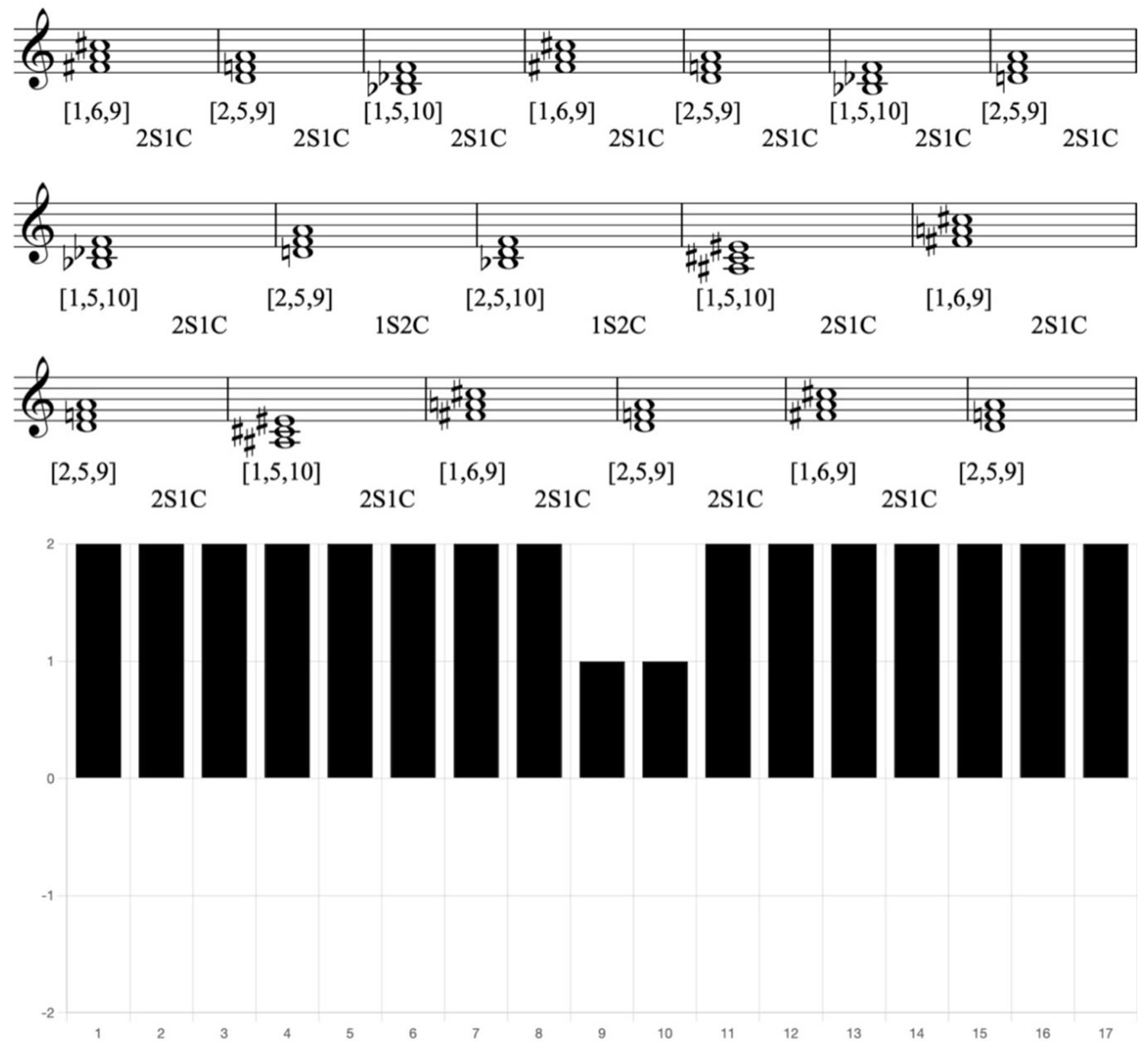

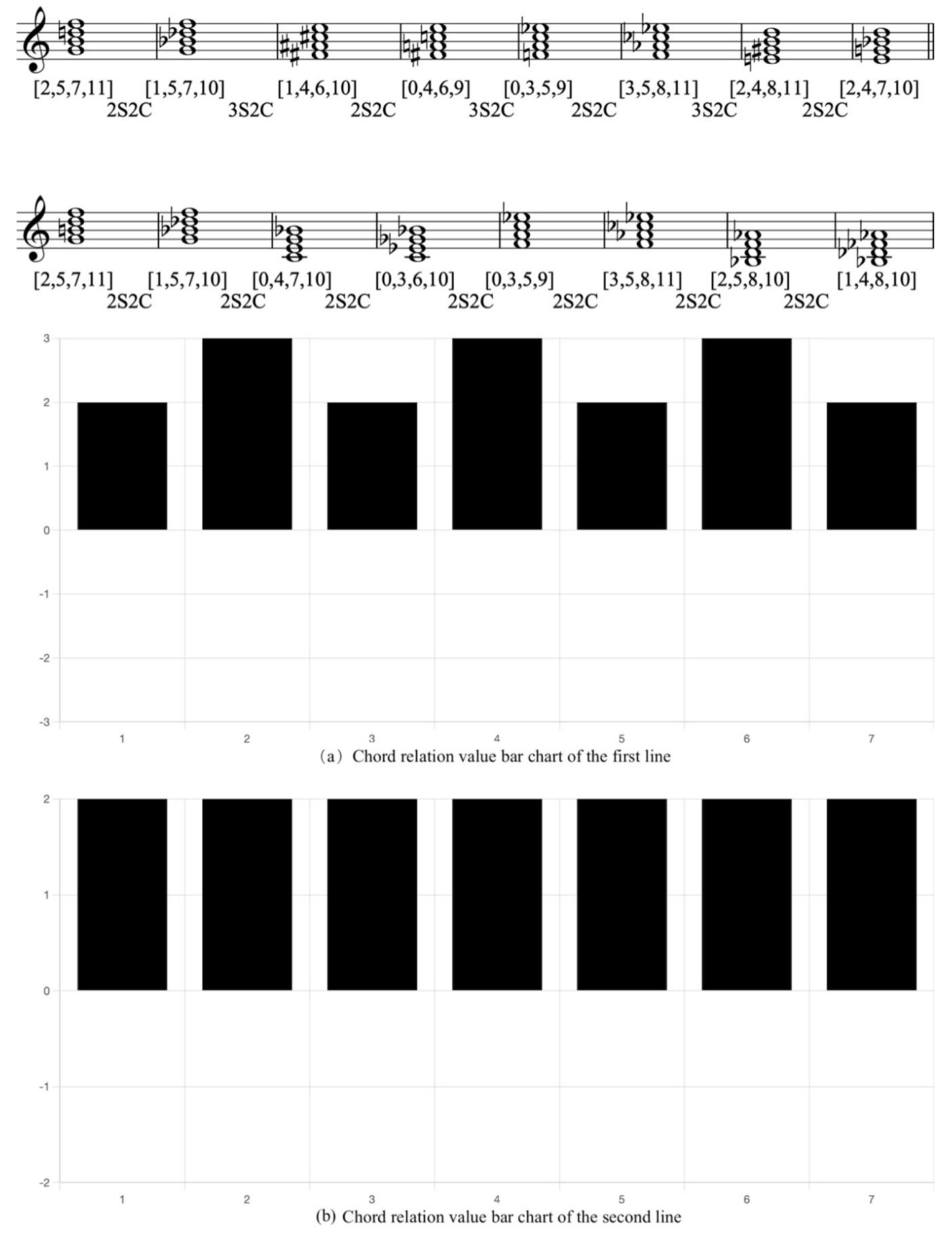

Example 19. Two sequential templates for Tristan-genus seventh chords with CRV bar chart

The 2S2C relation between the dominant seventh chord and the half-diminished seventh chord forms the sequences. In the first line, these sequences descend in minor seconds, while in the second line, they follow a fifth cycle progression. The third, fourth, seventh, and eighth chords in the second line can be regarded as tritone substitutes for their corresponding chords in the first line. From the perspective of CRV, the sequences based on chromatic relations exhibit a higher degree of tendency at 3S, while the fifth cycle progression demonstrates slightly a weaker degree of tendency at 2S. Overall, both types of sequences maintain a relatively high degree of tendency, resulting in a similar sense of harmonic movement.

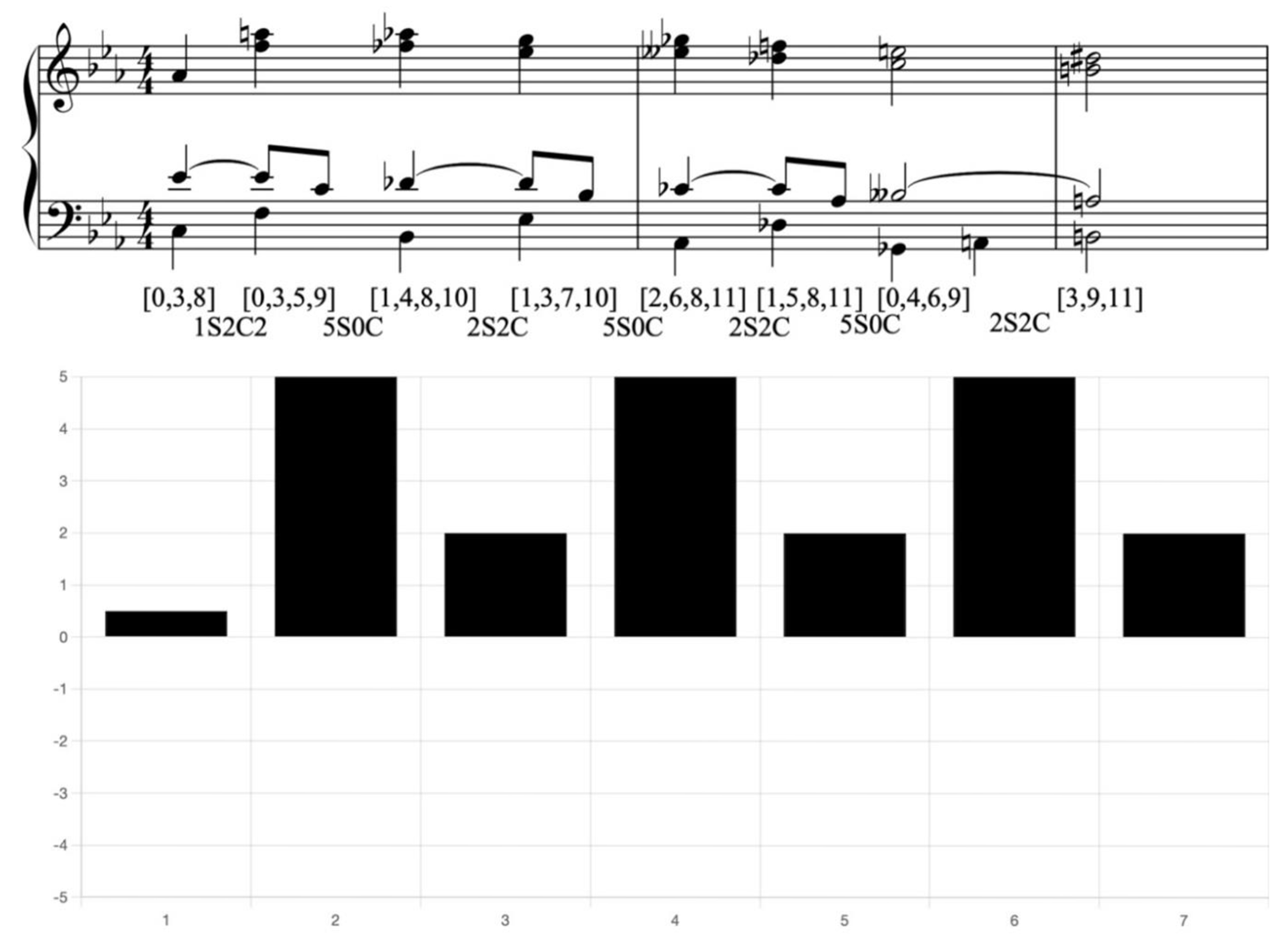

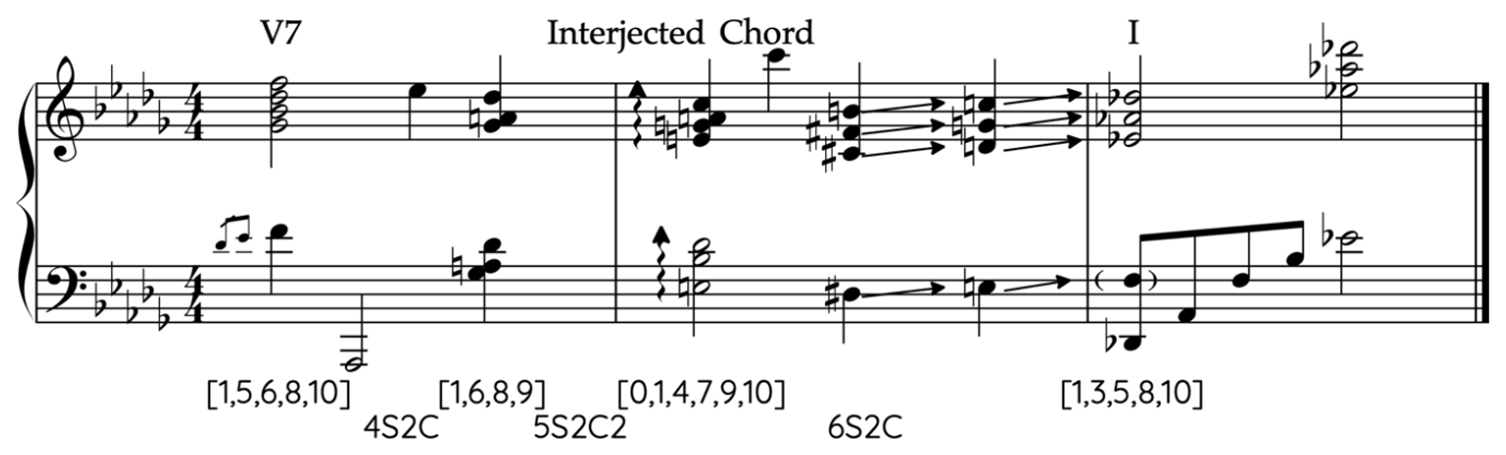

Example 20. Charlap, Pure Imagination, In All Through the Night, 1997, 1:23, transcripted by Li Lin

This is a jazz example. In jazz music, chords more complex than seventh chords are typically used, yet we can still observe the chord relations through the CRV. In this example, the chord in the first measure functions as a dominant chord, utilizing extended notes to enhance its color. The chord in the third measure serves as the tonic and is preceded by two quartal chords that continuously ascend through semitonal movement towards the tonic. The E diminished chord in the second measure acts as an insert chord, forming a 5S2C relation with the preceding dominant chord and a 6S2C relation with the tonic. The purpose of using this chord is to create a strong degree of tendency due to the abundance of semitones it forms in relation to both the preceding and succeeding chords.

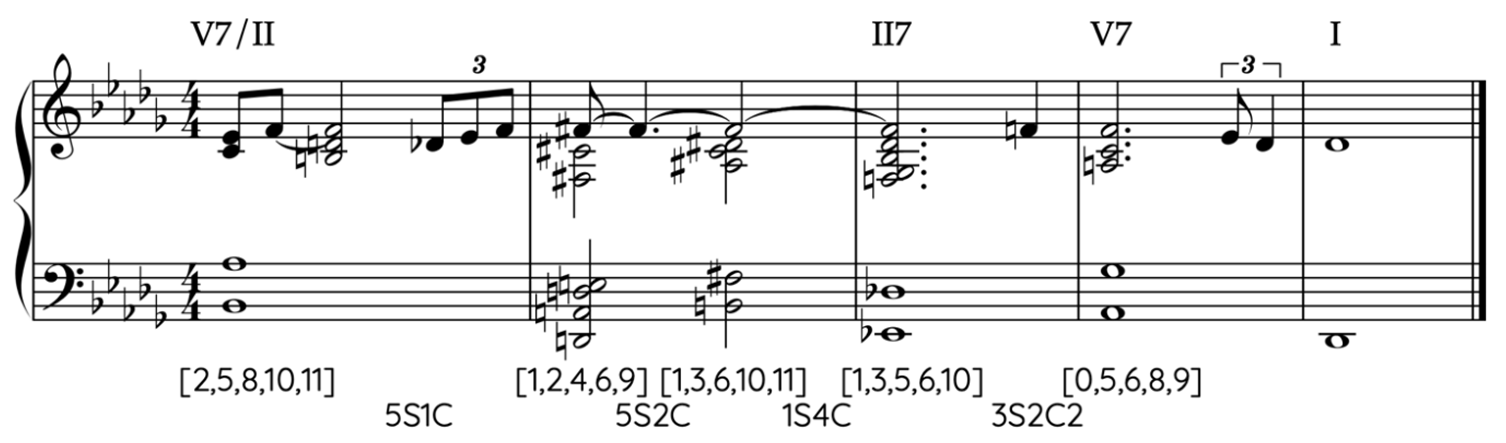

Example 21. Glasper, ‘Y’ Outta Praise Him Intro, In My Element, 2007, 1:24, transcripted by Li Lin

There is another jazz example from pianist Robert Glasper. Between the V/II and the II7, two chords that are not part of the D♭ major are employed. The D major ninth chord creates a high degree of tendency with the preceding B♭ dominant ninth chord, forming a 5S relation that strongly propels the harmony away from D♭ major. Additionally, it establishes a 4S relation with the succeeding B major ninth chord, helping to maintain this tendency. Finally, the 4C relation between the B major ninth chord and the E♭ minor ninth chord, characterized by significant similarity, subtly guides the harmonic progression back on track toward the original key.

Example 22. Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, Preludio, mm. 2-3

CRV also demonstrates significant potential for understanding and revealing the dynamic state of harmony. For example, in this famous excerpt, after the Tristan chord appears, the melody ascends semitonally to the next chord. This ascending semitonal movement plays a role in enhancing harmonic tendency. Originally, the CRV between the Tristan chord and the preceding chord is 4S1C. However, by adding the semitonal passing note A, the quantity of semitones between them increases to five. Similarly, the E dominant seventh chord initially has a CRV of 4S1C with the preceding chord, and the introduction of the semitonal passing note A♯ also raises the quantity of semitones to five. This indicates that this semitonal melody not only serves as a melodic element but also reinforces the tendency of the harmony. This aligns with Seth’s (2016) viewpoint. He does not regard G♯ merely as an auxiliary note to A. Through the lens of Voice-Leading Energetics, he affirms the complex tension relationships between harmony and melody.

Additionally, this example demonstrates that when analyzing chord relations, the existential facticity of semitones is more significant than voice leading. From the perspective of voice leading, there are three semitonal movements from the Tristan chord to the next chord: A to A♯ in the melody layer, as well as D♯ to D and F to E in the chord layer. These three semitonal movements between the two four-note chords create a considerable degree of tendency. However, the movement from B to G♯ presents a slight dissatisfaction, as it does not contribute to the realization of utmost tendency between these two chords. From the perspective of the existential facticity of semitones, this dissatisfaction does not exist, as there is an additional semitonal movement from B to A♯. By transcending voice leading, we gain insight into the essence of the semitonal movements between these two chords, revealing that Wagner truly achieved utmost degree of tendency within this progression.

Further Research

This research currently focuses on analyzing the relations between triads and seventh chords. However, musical works encompass a wide variety of chord types, including non-triadic chords, chords with additional notes, and tone clusters. This method enables the inclusion of a broader range of chord types for comparison and has the potential to theoretically encompass all possible chord forms. Furthermore, it can transcend tonal boundaries to achieve a more in-depth analysis of the relations between any two existing chords. Future research will incorporate these chord types to verify the applicability of the CRV theory across various musical works from different periods and styles.

While the CRV theory provides a fresh perspective for analyzing harmony, it is essential to integrate it with existing harmonic analysis methods, such as functional harmony theory, Schenkrian analysis, and transformational theory, to develop a more comprehensive system for harmony analysis. For example, combining the CRV theory with Schenkrian analysis allows for a focus on the CRVs between chords while also examining the CRVs of deeper harmonic structures. Additionally, it is important to place CRV theory within a historical perspective, as this is crucial for analysis. Understanding the evolution of harmonic theory aids in conducting a deeper analysis of musical works and helps avoid oversimplified interpretations (Damschroder 2008).

References

- Bregman, Albert S. 1990. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organization of Sound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Capuzzo, Guy. 2004. “Neo-Riemannian Theory and the Analysis of Pop-Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 26 (2): 177–99. [CrossRef]

- Childs, Adrian P. 1998. “Moving Beyond Neo-Riemannian Triads: Exploring a Transformational Model for Seventh Chords.” Journal of Music Theory 42 (2): 181–93. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Richard. 1996. “Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems, and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions.” Music Analysis 15 (1): 9–40. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Richard. 1997. “Neo-Riemannian Operations, Parsimonious Trichords, and Their ‘Tonnetz’ Representations.” Journal of Music Theory 41 (1): 1–66. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Richard. 2012. Audacious Euphony: Semitonal Harmony and the Triad’s Second Nature. Oxford: Oxford Studies in Music Theory. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dowling, W. J. 1967. Rhythmic fission and the perceptual organization of tone sequences.

- Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Goldenberg, Yosef. 2016. “Harmony without Voice Leading? The Challenge of Interpreting Exact Leaping Transpositions.” Music Analysis 35 (3): 314–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26630993.

- Goldstein, E. Bruce. 2019. Sensation and Perception. 10th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Heetderks, David. 2013. “Semitonal Succession-Classes in Prokofiev’s Music and Their Influence on Diatonic Voice-Leading Backgrounds in the Op. 94 Scherzo.” Intégral 27: 159–212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24368378.

- Huron, David. 2001. “Tone and Voice: A Derivation of the Rules of Voice-Leading from Perceptual Principles.” Music Perception 19 (1): 1–64. [CrossRef]

- Huron, David. 2016. Voice Leading: The Science behind a Musical Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Scholarship Online. [CrossRef]

- Levy, Ernst. 1985. A Theory of Harmony. Columbia University Press.

- McAdams, Stephen, and Albert S. Bregman. 1979. “Hearing Musical Streams.” Computer Music Journal 3 (2): 26–60.

- Milne, Andrew J., and Simon Holland. 2016. “Empirically Testing Tonnetz, Voice-Leading, and Spectral Models of Perceived Triadic Distance.” Journal of Mathematics and Music 10 (1): 59–85. [CrossRef]

- Monahan, Seth. 2016. “Voice-Leading Energetics in Wagner’s ‘Tristan Idiom’.” Music Analysis 35 (2): 171–232. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43864582.

- Poulin-Charronnat, Bénédicte, Bigand, Emmanuel, & Madurell, François. (2005). “The Influence of Voice Leading on Harmonic Priming.” Music Perception, 22(4), 613–627. [CrossRef]

- Tversky, Amos. 1977. “Features of Similarity.” Psychological Review 84 (4): 327–352. [CrossRef]

- Tymoczko, Dmitri. (2008). “Scale Theory, Serial Theory, and Voice Leading.” Music Analysis, 27(1), 1–49.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).