Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

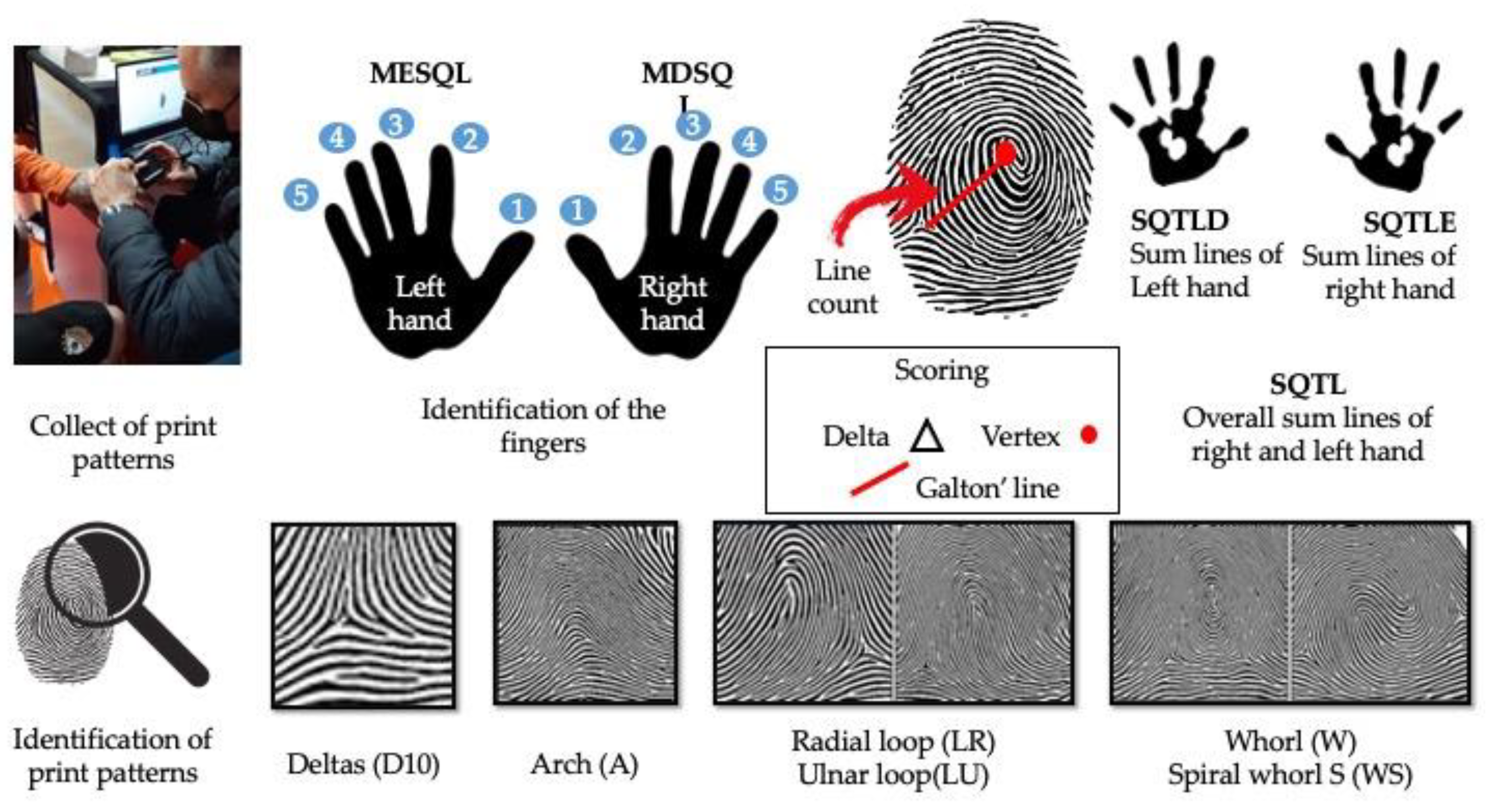

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Protocol

2.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

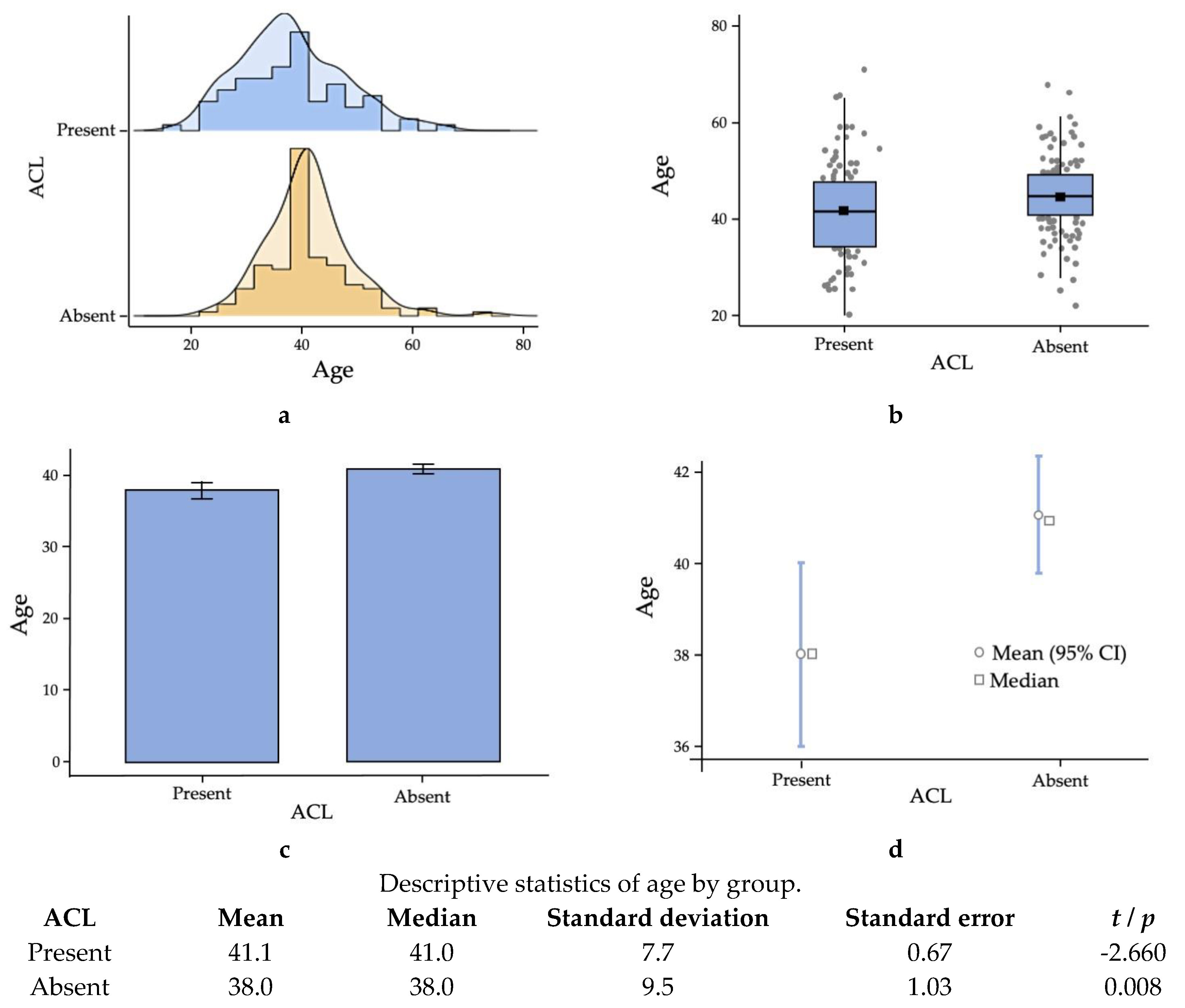

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnosis by Dermatoglyphics, Career Time, and Retirement Age of the Athlete

4.2. Number of Lines Defined by Dermatoglyphics

4.3. Print Patterns

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

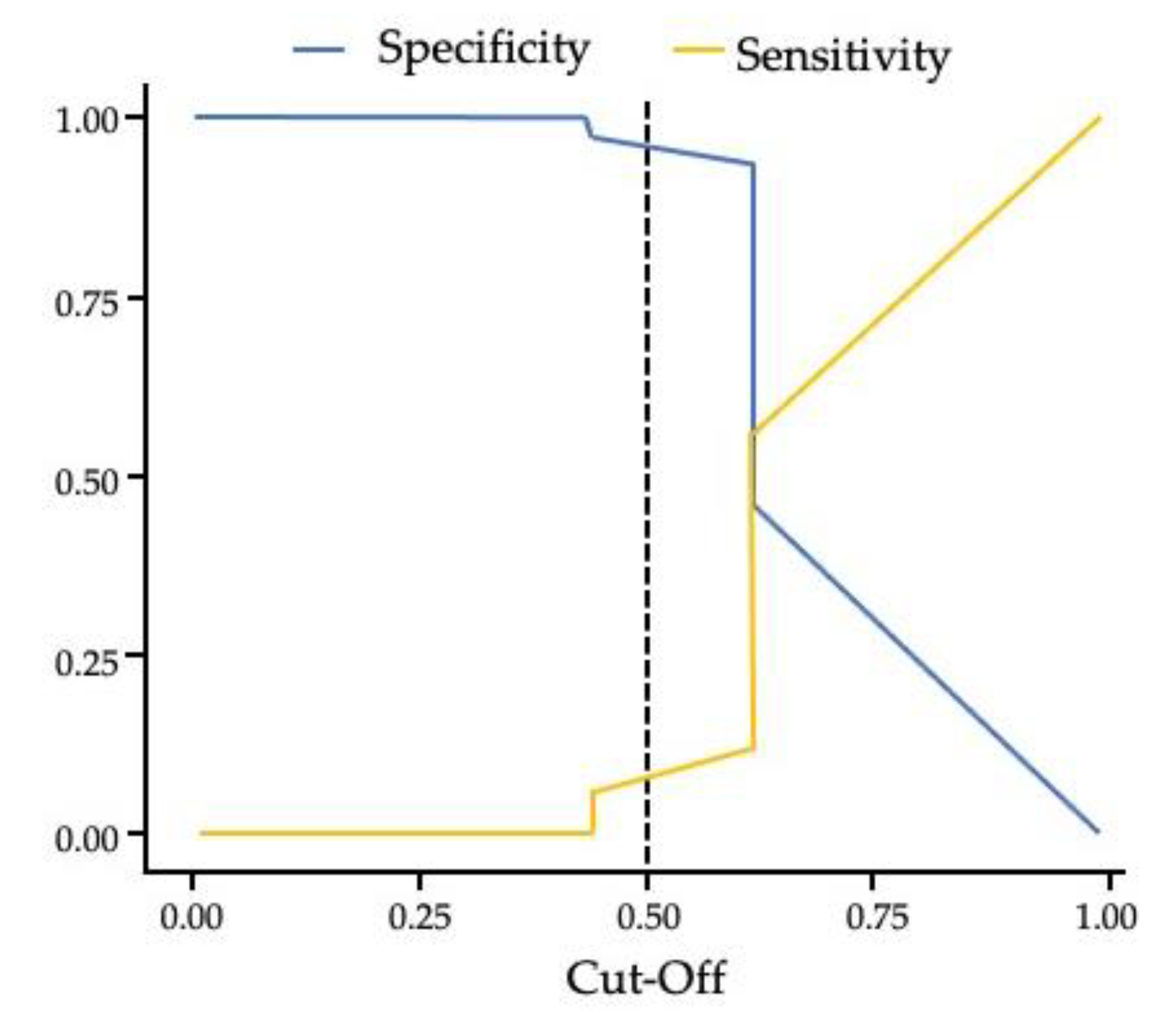

Appendix A

- Sensitivity (rate of true positives) = a/(a+c)

- Specificity (rate of true negatives) = d/(b+d)

- Accuracy = (a+d)/(a+b+c+d)

- Positive predictive value = a/(a+b)

- Negative predictive value = d/(c+d) fic

Appendix B

References

- Silvera, J.J.p. Loco Abreu: a autoconstrução de uma idolatria. Espo e Soc 2017, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- FIFA Futsal LOTG 2010/2011, Available from: http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/affederation/generic/51/44/50/spielregelnfutsal_2010_11_e.pdf, 2016.

- Moore, R.; Bullough, S.; Goldsmith, S.; Edmondson, L. A Systematic Review of Futsal Literature. Amer J. of Spor Scie and Med 2014, 3, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.; Nodari Junior, R.J.; Pasqualotti, A. Participação genética na lesão do ligamento cruzado anterior: revisão sistemática. In. Tópicos em Ciências da Saúde, 1ª ed.; Barros, R.N., Alves, G.S.B., Oliveira, E., Eds.; Editora: Paisson, Belo Horizonte, Brasil, 2022; Volume 28, pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharisma, Y.; Mubarok, M.Z. Analisis Tingkat Daya Tahan Aerobik Pada Atlet Futsal Putri AFKAB Indramayu. Physical Activity Journal (PAJU), 2020, 2, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxburgh, A. The technician futsal. Newsletter for coaches UEFA, 2008, Supplement 4, p. 1-12. Disponível online: https://www.uefa.com/newsfiles/649735.pdf (acessado em 23 de Novembro de 2022).

- Soares, B.H.; Pasqualotti, A.; Rocha, C.L.S.D.; Alberti, A.; Gomes, S.A. O impacto da pandemia covid-19 no futsal gaúcho. Rev Bras de Fut e Fut 2022, 54, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, A.; Schlosser, M. W.; Brancher, E.A. Análise das técnicas de goleiro mais utilizadas durante os jogos de Futsal masculino. Rev Bras de Fut e Fut 2016, 30, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, E.R.; Navarro, A.C.; Santos, Í.J.L.M.; Cunha, M.L.A.; Araújo, M.L.; Gomes de Carvalho, W.R. Análise dos gols e tendência com a equipe campeã em um campeonato de Futsal regional do Brasil. Rev Bras de Fut e Fut 2017, 34, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- FIFA. Laws of the Game. Zurich: Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA). 2020.

- Herman, I.; Hasan, M.F.; Hidayat, I.K.; Apriantono, T. Analysis of Speed and Acceleration on 60-Meters Running Test Between Women Soccer and Futsal Players. Advances in Health Sciences Research. International Conference on Sport Science, Health, and Physical Education 2019, 4, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, K. L.; Zmijewski, p.; Makaruk, H.; Mróz, A.; Lipnska, p. Effects of Short-Term Plyometric Training on Physical Performance in Male Handball Players. J. of Hum Kinet 2018, 63, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldaço, F.; Cadó, V.; Souza, J.; Mota, C.; Lemos, J. Análise do treinamento proprioceptivo no equilíbrio de atletas de futsal feminino. Rev Fisio em Mov 2010, 2, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoro, J.C. Futebol 100% profissional, 15ª ed.; Editora Gente, Brasil - São Paulo, 2017. pp. 251.

- Fin, W.; Soares, B; Bona, C. C.; Vilasboas, R.; Matzenbacher, F. Potencia aeróbia em atletas de futsal de diferentes níveis competitivos. Rev Bras de Fut e Fut 2020, 49, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Pfirmann, D.; Herbst, M.; Ingelfinger, p.; Simon, p.; Tug, S. Analysis of injuries incidences in male professional adult and elite youth soccer players: a systematic review. J. of Athlet Train 2016, 5, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes Neto, J.S.; Andrade, C.; Girão, p.I.F.; Guimarães, D.F.; Bezerra, A.K.T.G.; Girão, M.V.D. Análises das faltas e lesões desportivas em atletas de futebol por meio de recursos audiovisuais de domínio público. Rev Bras de Fut e Fut 2020, 47, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, T.; Švehlík, M.; Singer, G.; Schalamon, J.; Zwick, E.; Linhart, W. The epidemiology of knee injuries in children and adolescents. Arch of Orthop and Trauma Sur 2012, 132, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, p.; Grau, L.; Kaplan, L.; Baraga, M.G. Knee Injuries in American Football: An Epidemiological Review. Amer J. of Orthop 2016, 45, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.K.; De La Rosa Santana, J.D.; Santiesteban, L.L.E.; Peña, A.M.F.; Labrada, G.D. La articulación de la rodilla: lesión del ligamento cruzado anterior. Rev Cient 2 Dic 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Astur, D.C.; Batista, R.F.; Gustavo, A.; Cohen, M. Trends in treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee in the public and private health care systems of Brazil. São Paulo Med J 2013, 4, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.C.O.; Ordóñez, S.F.R.; Brito, p.R.F. Tratamiento funcional de la lesión de ligamento cruzado anterior de la rodilla: una revisión. La Cie al Serv de la Salud 2019, 2, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, T.E.; Myer, G.D.; Ford, K.R.; Paterno, M.V; Quatman, C.E. Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: Cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools. J Orthop Res 2016, 11, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nessler, T.; Denney, L.; Y Sampley, J. ACL injuries prevention: what does research tell us? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017, 3, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, K.M.; Bullock, J.M. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture: Differences between Males and Females. J. of the Amer Acade of Orthop Surg 2013, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benis, R.; La Torre, A.; Bonato, M. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries profile in female elite Italian basketball league. The Amer Jour of Spo Med 2018, 3, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T.L.; Maradit Kremers, H.; Bryan, A.J. , Larson, D.R.; Dahm, D.L., Levy, B.A., Stuart, M.J., Eds.; Krych, A.J. Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Sports Med 2016, Volume 44, Number 06, p.1502-1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Rosen, p.; Kottorp, A.; Fridén, C.; Frohm, A.; Heijne,A. Young, talented and injured: Injuries perceptions, experiences and consequences in adolescent elite athletes. Euro J. of sport scien 2018, 5, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astur, D.C.; Xerez, M.; Rozas, J.; Vargas Debieux, p.; Franciozi, C.; Cohen, M. Anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries in sports: incidence, time of practice until injuries, and limitations caused after trauma. Rev Bras de Ortop 2016, 51, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, G.C.; Abreu, M.B.; Sandes, M.T.S.; Borges, M.R.; Silva, M.M. The effectiveness of electrochemistry in Acute treatment in football players. Rev de Ciên Hum, 2018, 2, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Meurer, M.C.; Silva, M.F.; Baroni, B.M. Strategies for injuries prevention in Brazilian football: Perceptions of physiotherapists and practices of premier league teams. Phys Ther Sport 2017, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmander, L.S.; Englund, p.M.; Dahl, L.L.; Roos, E.M. The longterm consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Amer J. of Spo Medi. 2007, 10, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.; Vicensi, D.J.; Alves, M.A.R.; Ballesteros, M.A.M.; Gomes, S.A.; Ferreira, C.E.S.; Nodari Junior, R.J.; PaqualottI, A.; Voser, R.C. Análise da velocidade da bola no chute de jogadores de futsal em função do contato do peito do pé dos membros inferiores. Research, Soc and Dev 2022, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, H.; Midlo, C.H. Fingerprints, palms, and soles an introduction to dermatoglyphics. New York: Dover Publications; 1961. pp.333.

- Abramova, T.F.; Nikitina, T.M.; Izaak, S.I.; Kochetkova, N.I. Asimmetriia priznakov pal'tsevoĭ dermatoglifiki, fizicheskiĭ potentsial i fizicheskie kachestva cheloveka [Asymmetry of signs of finger dermatoglyphics, physical potential and physical qualities of a man]. Morfologiia. 2000, 5, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.G. The Fingerprint. U. S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. National Institute of Justice; 2002.

- Nodari Junior, R.J. Heberle, A.; Ferreira-Emygdio, R.; Irany-Knackfuss, M. Impressões digitais para diagnóstico em saúde: validação de protótipo de escaneamento informatizado. Rev de Salud Púb 2008, 5, 767–776. [Google Scholar]

- Nodari Junior, R.J.; Fin, G. Dermatoglifia: impressões digitais como marca genética e de desenvolvimento fetal; Ed. Unoesc: Joaçaba, Brasil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, K. The Fingerprint. U. S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. National Institute of Justice, 2002.

- Baretta, E.; Sartori, G.; Fin, G.; Nodari Junior, R.J. Marcas Dermatoglíficas em mulheres com câncer de mama. Congresso Internacional De Atividade Física, Nutrição E Saúde, Volume 1. Recuperado de https://eventos.set.edu.br/CIAFIS/article/view/2856. 2016.

- Fin, G.; Jesus, J. A.; Benetti, M.; Nodari Júnior, R.J. La práctica de actividad física en mujeres con cáncer de mama: asociación entre factores motivacionales y características dermatoglíficas. Cuad de Psico del Dep 2022, 1, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Vianna, M.V.A.; Gomes, A.L.M.; Dantas, E.H.M. Diagnóstico do potencial genético físico e somatotipia de uma equipe de futebol profissional Fluminense. Rev Bras de Fut 2008, 1, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, R.M.; Corrêa, D.A. Aspectos importantes no processo detecção e orientação de talentos esportivos e a contribuição da estatística Z neste contexto. Conexões 2015, 2, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodari Junior, R.J. Heberle, A.; Ferreira-Emygdio, R.; Irany-Knackfuss, M. Dermatoglyphics: Correlation between software and traditional method in kineanthropometric application. Rev Andal Med Deporte 2014, 2, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, A.; Fin, G.; Gomes de Souza, R.; Soares, B.; Nodari Junior, R.J. Dermatoglifia: as impressões digitais como marca característica dos atletas de futsal feminino de alto rendimento do Brasil. Rev Bras de Fut e Fute 2018, 37, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, H.S. , Graff, M., Stein, A. D., Lumey, L.H. A fingerprint marker from early gestation associated with diabetes in middle age: the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study. Internat J. Epidem 2009, 1, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, S. Dermatoglyphic meta-analysis indicates early epigenetic outcomes & possible implications on genomic zygosity in type-2 diabetes. F1000Research 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Mancini-Marïe, A.; Brunet, A.; Walker, E.; Meaney, M.J.; Laplante, D.P. Prenatal maternal stress from a natural disaster predicts dermatoglyphic asymmetry in humans. Dev Psychopathol 2009, 2, 343–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresta, M.C.; Brandão, M.R.F.; Barros Neto, T.L. Impacto do término de carreira esportiva na situação econômica e profissional de jogadores de futebol profissional. R. Bras. C. e Mov 2008, 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.p.A.D.; Miranda, I.S.; Silva, A.L.C.; Cos, F.R. A dupla carreira esportiva no Brasil: Um panorama na agenda das políticas públicas. Rev Com Censo 2020, 2, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, G.F.; Rubio, K. Mulheres atletas olímpicas brasileiras: início e final de carreira por modalidade esportiva. R. bras. Ci. e Mov 2017, 4, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylleman, p.; Rosier, N. Holistic Perspective on the Development of Elite Athletes. In Sport and Exercise Psychology Research: From Theory to Practice, 1ª ed.; In: Raab, M., Seiler, R., Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Wylleman, p., Eds.; Elbe, A.M. Elsevier: Amsterdã, Holanda, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodari Junior, R.J.; Alberti, A.; Gomes de Souza, R.; Pinheiro, C.J. B.; Martinelli Comim, C.; Fin, G.; Dantas, E.H.M.; Soares, B.H. , Souza, R. Características dermatoglíficas de jogadores de futsal de alto desempenho. Rev Bras De Fut e Fut 2022, 57, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Baretta, E.; Pizzi, S.; Fin, G.; Fiedler, M.M.; Nodari Junior, R.J. Impressões digitais como marcadores genéticos de aptidão cardiorrespiratória. In: Anais do XXI Seminário de Iniciação Científica. E, VIII Seminário Integrado de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão. E, VI Mostra universitária, 2015, Videira. Pesquisa e Inovação: inserção social e científica na comunidade regional. Joaçaba: Unoesc, 2015, Volume 1, pp. 297-297.

- Stefanes, V.S.; Nodari Junior, R.J. impressão digital como marca Genética no prognóstico de Cardiopatias. Unoesc & Ciência 2015, 2, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, J.A.J; Zanoni, E.M.; Silva, H.L.; Baretta, E.; Souza, R.; Alberti, A.; Fin, G.; Nodari Júnior, R.J. Dermatoglyphics and its relationship with the speed motor capacity in children and adolescentes. Internat J. of Devel Research 2019, 3, 26430–26434. [Google Scholar]

- The jamovi project (2024). jamovi. (Version 2.6) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.4) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from CRAN snapshot 2024-08-07).

| Predictor | χ² | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACL | 1.605 | 1 | 0.205 |

| Hands | 0.050 | 1 | 0.823 |

| Print patterns | 606.254 | 4 | < 0.001 |

| ACL ✻ Hands | 0.028 | 1 | 0.867 |

| Print patterns ✻ ACL | 18.188 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Hands ✻ Print patterns | 1.836 | 4 | 0.766 |

| ACL ✻ Hands ✻ Print patterns | 6.221 | 4 | 0.183 |

| Predictor | Estimates | SE | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.664 | 0.160 | 22.879 | < 0.001 |

| ACL: | ||||

| Present – Absent | 0.268 | 0.213 | 1.261 | 0.207 |

| Hands: | ||||

| Right hand – Left hand | 0.050 | 0.224 | 0.224 | 0.823 |

| Print patterns: | ||||

| A – WS | -0.445 | 0.256 | -1.736 | 0.083 |

| LR – WS | 0.187 | 0.217 | 0.861 | 0.389 |

| LU – WS | 2.282 | 0.168 | 13.574 | < 0.001 |

| W – WS | 1.292 | 0.181 | 7.148 | < 0.001 |

| ACL ✻ Hands: | ||||

| (Present – Absent) ✻ (Right hand – Left hand) | -0.050 | 0.299 | -0.167 | 0.867 |

| Print patterns ✻ ACL: | ||||

| (A – WS) ✻ (Present – Absent) | -1.408 | 0.459 | -3.070 | 0.002 |

| (LR – WS) ✻ (Present – Absent) | -1.228 | 0.349 | -3.515 | < 0.001 |

| (LU – WS) ✻ (Present – Absent) | -0.665 | 0.228 | -2.921 | 0.003 |

| (W – WS) ✻ (Present – Absent) | -0.713 | 0.252 | -2.835 | 0.005 |

| Hands ✻ Print patterns: | ||||

| (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (A – WS) | -0.091 | 0.363 | -0.250 | 0.802 |

| (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (LR – WS) | 0.070 | 0.300 | 0.234 | 0.815 |

| (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (LU – WS) | -0.109 | 0.235 | -0.464 | 0.642 |

| (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (W – WS) | 0.050 | 0.252 | 0.200 | 0.841 |

| ACL ✻ Hands ✻ Print patterns: | ||||

| (Present – Absent) ✻ (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (A – WS) | 0.091 | 0.649 | 0.140 | 0.889 |

| (Present – Absent) ✻ (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (LR – WS) | 0.777 | 0.457 | 1.701 | 0.089 |

| (Present – Absent) ✻ (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (LU – WS) | -0.083 | 0.321 | -0.259 | 0.796 |

| (Present – Absent) ✻ (Right hand – Left hand) ✻ (W – WS) | 0.157 | 0.350 | 0.449 | 0.653 |

| Number of lines | ACL | Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error | t /p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MESQL1 | Present | 13.9 | 5.5 | 0.6 | -0.914 |

| Absent | 14.6 | 5.1 | 0.46 | 0.362 | |

| MESQL2 | Present | 9.1 | 5.1 | 0.55 | 0.094 |

| Absent | 9.1 | 5.5 | 0.49 | 0.925 | |

| MESQL3* | Present | 10.9 | 4.5 | 0.49 | 0.519 |

| Absent | 10.5 | 5.5 | 0.49 | 0.604 | |

| MESQL4 | Present | 13.3 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.516 |

| Absent | 12.9 | 5.5 | 0.49 | 0.607 | |

| MESQL5 | Present | 12.3 | 4.5 | 0.49 | 1.650 |

| Absent | 11.3 | 4.7 | 0.42 | 0.101 | |

| MDSQL1 | Present | 15.9 | 5.2 | 0.56 | 0.442 |

| Absent | 16.4 | 4.5 | 0.40 | 0.659 | |

| MDSQL2 | Present | 9.9 | 5.4 | 0.59 | -0.796 |

| Absent | 8.9 | 5.9 | 0.52 | 0.427 | |

| MDSQL3 | Present | 10.7 | 4.6 | 0.49 | 1.161 |

| Absent | 10.5 | 5.0 | 0.45 | 0.247 | |

| MDSQL4* | Present | 13.2 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 0.199 |

| Absent | 12.5 | 5.5 | 0.49 | 0.843 | |

| MDSQL5 | Present | 12.2 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0.943 |

| Absent | 11.9 | 4.7 | 0.42 | 0.347 | |

| SQTLE | Present | 59.5 | 18.5 | 2.00 | 0.455 |

| Absent | 58.3 | 20.1 | 1.79 | 0.650 | |

| SQTLD | Present | 61.8 | 18.9 | 2.05 | 0.553 |

| Absent | 60.3 | 19.9 | 1.77 | 0.581 | |

| SQTL | Present | 121.3 | 35.9 | 3.90 | 0.515 |

| Absent | 118.6 | 38.8 | 3.45 | 0.607 | |

| D10 | Present | 13.4 | 3.2 | 0.35 | 1.694 |

| Absent | 12.6 | 3.5 | 0.31 | 0.092 |

| Hands | ACL | Print patterns | χ² | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | LR | LU | W | WS | |||

| Left hand | Present | 8 (24.2 %) | 18 (27.7 %) | 257 (40.2 %) | 91 (39.1 %) | 51 (56.7 %) | 15.072 0.005 |

| Absent | 25 (75.8 %) | 47 (72.3 %) | 382 (59.8 %) | 142 (60.9 %) | 39 (43.3 %) | ||

| Right hand | Present | 8 (25.0 %) | 42 (44.2 %) | 212 (37.1 %) | 112 (41.6 %) | 51 (55.4 %) | 18.015 0.001 |

| Absent | 24 (75.0 %) | 53 (55.8 %) | 360 (62.9 %) | 157 (58.4 %) | 41 (44.6 %) | ||

| Overall | Present | 16 (24.6 %) | 60 (37.5 %) | 469 (38.8 %) | 203 (40.4 %) | 102 (56.0 %) | 27.125 < 0.001 |

| Absent | 49 (75.4 %) | 100 (62.5 %) | 742 (61.2 %) | 299 (59.6 %) | 80 (44.0 %) | ||

| Finger coding | ACL | Print patterns | p | ||||

| A | LR | LU | W | WS | |||

| MED1 | Present | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 40 (38.1%) | 18 (35.3%) | 22 (51.2%) | 0.559 |

| Absent | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 65 (61.9%) | 33 (64.7%) | 21 (48.8%) | ||

| MED2 | Present | 4 (30.8%) | 11 (26.8%) | 33 (41.3%) | 24 (40.7%) | 13 (68.4%) | 0.043 |

| Absent | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 65 (61.9%) | 33 (64.7%) | 21 (48.8%) | ||

| MED3 | Present | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | 63 41.7%) | 14 (43.8%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.145 |

| Absent | 7 (77.8%) | 10 (90.9%) | 88 (58.3%) | 18 (56.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | ||

| MED2 | Present | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 49 (38.9%) | 28 (40.6%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0.250 |

| Absent | 4 (100.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 77 (61.1%) | 41 (59.4%) | 4 (36.4%) | ||

| MED5 | Present | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 72 (40.7%) | 7 (31.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0.770 |

| Absent | 1 (100.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 105 (59.3%) | 15 (68.2%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||

| MDD1 | Present | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | 31 (32.3%) | 30 (43.5%) | 20 (48.8%) | 0.213 |

| Absent | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 65 (66.7%) | 39 (56.5%) | 21 (51.2%) | ||

| MDD2 | Present | 2 (13.3%) | 27 (45.0%) | 23 (32.9%) | 23 (46.9%) | 10 (55.6%) | 0.053 |

| Absent | 13 (86.7%) | 33 (55.0%) | 47 (67.1%) | 26 (53.1%) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| MDD3 | Present | 3 (30.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 60 (39.2%) | 12 (41.4%) | 6 (75.0%) | 0.311 |

| Absent | 7 (70.0%) | 8 (66.7%) | 93 (60.8%) | 17 (58.6%) | 2 (25.0%) | ||

| MDD4 | Present | 1 (25.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 33 (31.1%) | 40 (44.9%) | 7 (46.9%) | 0.646 |

| Absent | 3 (71.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 61 (64.9%) | 49 (55.1%) | 8 (53.3%) | ||

| MDD5 | Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 65 (40.9%) | 7 (21.2%) | 8 (80.0%) | 0.007 |

| Absent | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 94 (59.1%) | 26 (78.8%) | 2 (20.0%) | ||

| WS print pattern | Definitive diagnosis of ACL | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||

| Present | 102 | 80 | 182 |

| Absent* | 748 | 1.190 | 1.938 |

| Total | 850 | 1.270 | 2.120 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).